Abstract

Background

Occupational therapists are encouraged to use research evidence to guide therapeutic interventions that holistically address the consequences of dementia. Recent efforts to use research evidence in practice have emphasized the challenges of doing so in ways aligned to person-centred and professional principles. Using research evidence is a complex process influenced by multiple contextual factors and layers. The influence of context in occupational therapy for dementia is currently unclear.

Aims

To explore the contextual complexities of using research evidence in practice with people with dementia, and to develop knowledge to improve the approach to using evidence in person-centred, occupation-focused practice.

Material & methods

A case study methodology was used, in which the contextual conditions of practice were clarified through the facilitation of critical and creative reflection using the following methods – Think Aloud, practice observation, creative expression and reflective dialogue.

Results

Cultural beliefs that affected evidence use included technically-orientated understandings of evidence-based practice. These were underpinned by apprehensions about losing professional identity and taking risks when processes derived from research evidence were adjusted to incorporate a persons’ occupations. These cultural factors were perpetuated at the organizational layers of context, where systemic priorities and other team members’ needs disproportionately influenced occupational therapists’ decisions.

Conclusions & significance

Occupational therapists’ potential to make reflexive and responsive decisions by adjusting evidence-based processes can be affected by their perceived freedom to address organizational tensions. Raising consciousness of the influence of the organizational context on decision-making about evidence use could adjust occupational therapists’ perceptions of their freedom and ability to be person-centred. Intentionality in reflective processes in practice are required to foster reflexivity.

Introduction

This article discusses the contextual factors that contribute to the complexity of using research evidence derived from experimental studies in a UK practice context. It focuses on the context of evidence use in practice with people living with dementia, where there has been significant encouragement and resources developed to address the growing need for occupation-focused therapeutic interventions.

The challenge of providing health and care services for people living with dementia is considerable and continues to grow; by 2030 there will be an estimated 74.7 million people living with dementia [Citation1]. Consequently, developing care and therapy practices for health and social care practitioners working with people living with dementia has been, and remains a priority. Kitwood [Citation2] argued that a biomedical perspective inadequately addresses the holistic health and well-being needs of such groups. Rather, therapeutic interventions that enable occupational engagement at home and in communities are assumed to be of additional benefit in addressing the impact of dementia on a person’s well-being [Citation3,Citation4]. Thus, developing, using and evaluating such evidence-based interventions has been recognized as an urgent international priority [Citation5,Citation6].

Community-based occupational therapists were identified as having appropriate skills and understanding of the psychosocial impact of dementia to effectively use evidence-based, therapeutic approaches in their practice [Citation7]. However, despite international engagement in education to use interventions generated from research evidence, occupational therapists have reported experiencing challenges in using research evidence in a person-centred way; or in a way that is responsive to the needs of the person and clinical situation [Citation8]. A person-centred approach to using evidence aligns with the core principle of evidence-based practice (EBP), that evidence is used in a ‘conscientious, explicit and judicious’ [Citation9,p.1] way to support decision making on a situational basis [Citation9]. Both approaches to practice highlight the necessity of reflexivity and context-specific decision making in practice. However, research suggests that using research-based interventions in practice can be a frequent challenge for occupational therapists’, who often perceive a tension between this and person-centred practice [Citation10].

It is increasingly recognized that the complex challenges of using evidence conscientiously and judiciously can arise from the contexts in which practice occurs, and can thus be improved by the development of facilitative organizational contexts [Citation11,Citation12]. However, Rogers et al. [Citation13] argue that the concept of context remains poorly understood and defined, consequently complicating research and development initiatives intended to support effective EBP. Their systematic examination of definitions of context offered a working definition for this research, with context understood as ‘a multi-dimensional construct encompassing micro, meso and macro level determinants that are pre-existing, dynamic and emergent through the [evidence] implementation process’ [Citation13,p.18]. The definition referred to contextual factors as inextricably intertwined and including multi-level concepts such as culture, leadership and the availability of resources. The systematic review of context proposed that the factors incorporated in this definition emerge at individual, team, organizational and external levels of practice contexts. Rogers et al. [Citation13] suggested that examination of the interplay of such factors can enable understanding of the complexity associated with supporting and making decisions about using research as part of person-centred practice. It also highlighted the potential for the reported challenges with evidence use to be influenced by a number of contextual layers (individual, team, organizational, political) and factors (leadership, culture, resources), though these may vary across practice settings.

Hunter et al. [Citation14] argued that different movements that influence practice, including implementation science, EBP and person-centredness, each imply different extents of individual and organizational responsibility for achieving practice that holistically addresses the needs of the person with living with dementia. Indeed, whilst implementation science theory suggests that the organizational context heavily influences the use of research evidence [Citation11], research related to evidence use in occupational therapy indicates that individual professional contexts are particularly influential, highlighting the significance of occupational therapists’ professional culture (their shared, taken-for-granted professional values and beliefs) [Citation8,Citation10]. The extensive features of context identified by Rogers et al. [Citation13], including culture and leadership, suggested that, when considering these tensions, occupational therapists’ professional perspectives, values and beliefs should be explored in relation to the identified organizational features, acknowledging the potential for contrasting/conflicting contextual factors at different layers of the practice context.

This literature suggested that exploring how evidence is used in practice to highlight contextual challenges could enable better understandings of the factors that could be addressed to enable reflexive and holistic approaches to EBP. Specifically, exploring the relationship between occupational therapists’ professional practice and the context they work in could illuminate the complexities of making person-centred decisions with research evidence. Current research does not offer significant exploration of such challenges, meaning potential for constructive developments is limited. This study aimed to:

Explore the contextual complexities of using evidence in a specific practice context, with occupational therapists who work with people living with dementia in the community.

Develop knowledge about improving approaches to using evidence-based therapeutic practices.

Background

Evidence use in practice

Occupational therapists that work with people with dementia have highlighted challenges in using interventions derived from research evidence in practice [Citation15,Citation16]. Community-based occupational therapy interventions for persons with dementia have been developed and experimentally tested in the UK [Citation17], Germany [Citation18], Netherlands [Citation19], US [Citation20], Brazil [Citation21], and Australia [Citation22]. These interventions are based on propositional knowledge and share theoretical principles, which generally posit that using evidence-based assessment and intervention resources to match a person’s activities to their physical and cognitive capabilities, habits and routines, and physical and social environment should enhance their occupational engagement, thereby improving quality of life and well-being [Citation16–19]. They often provide protocols for the key steps in the therapy process. Early experimental studies of the interventions indicated that, when fidelity to a defined intervention process was achieved, there were some significant positive effects on the function and engagement of the person with dementia [Citation18,Citation19], and the pleasure they derived from activity [Citation23].

While some positive effects of intervention implementation were identified, Di Bona et al. [Citation14] highlighted concerns that fidelity to the COTiD (UK) intervention protocol prevented therapists from practicing in person-centred ways. Additionally, exploratory studies [Citation14,Citation15] reflected occupational therapists’ uncertainty regarding the purpose of intervention implementation. Hynes et al.’s [Citation15] findings indicated that intervention processes, defined for the purpose of demonstrating effectiveness through experimental research, restricted occupational therapists’ perceived freedom to define the intended outcomes of therapy and adapt their approaches in response to occupational issues particular to each person. These challenges suggested that some of the fundamental issues with evidence use and the interplay between evidence and context were related to tensions between EBP research protocols and occupational therapists’ professional beliefs about appropriate approaches to practice. This interplay requires further exploration to understand and address the tensions between the contextual layers and features, recognizing that the particular features that influence approaches to evidence-based decision making are currently unclear and unexplored.

Complexity and context

Complexity theory can be used as a lens through which the challenges with evidence use (implementation) in this context can be understood [Citation24]. Complexity theory recognizes that models of practice (interventions) derived for experimental research processes often reflect ideal versions of a practice, developed for the purpose of enabling fidelity to the model or process [Citation25]. Such versions are described in many of the studies of practice with people living with dementia [Citation16–21]. A complexity lens assumes that the process of using evidence naturally interacts with contextual elements of a healthcare system such as practitioners’ and peoples’ values, healthcare policies or organizational practices, thereby generating an evidence-based practice that emerges or ‘self-organizes’ based on person-centred decisions [Citation23,Citation24,Citation26]. Past research into evidence-based occupational therapy with people living with dementia suggested that the interaction of the evidence with the context, as well as the process of evidence use, impacted on occupational therapists’ potential to make person-centred, holistic decisions in practice [Citation14,Citation15,Citation18].

Challenges using research evidence can emerge from contextual factors such as team relationships, role clarity, professional leadership and evaluation focus, and can be compounded by workforce improvement initiatives that overlook the complexity inherent in developing, implementing and evaluating EBP [Citation11]. In their exploration of complexity in occupational therapy, Pentland et al. [Citation25] highlighted that the interaction of therapy practices within social and physical practice contexts can help therapists to practice in ways that align with concepts and principles of complex interventions, rather than the processes and procedures, to facilitate emergence of person-centred decisions. This reflexivity or responsiveness to context can include adapting practice to fit particular circumstances and can alter the way evidence is used and thus the mechanisms that lead to outcomes [Citation24]. Understanding how and why occupational therapists’ practices are shaped by the interactions between contexts and practice might enable research evidence to be used in ways which also align with the values of person-centred practice.

Decision-making in context

Morgan-Trimmer et al.’s [Citation23]. application of a complexity perspective emphasized the role professional experience plays in negotiating the contextual factors that influence decision-making about how to use evidence as part of occupation-focused therapy. Other theories for evidence use also categorized research evidence as only one form of evidence, that can be blended with clinical experience, patient experience and routine data, through processes of professional reflection and reflexivity [Citation27,Citation28]. These theories emphasize the reflective and reflexive nature of the process required to enable a contextually responsive approach to using research evidence [Citation29], as well as the potential for understanding contextual interplays through reflective practice processes [Citation10].

Given the social nature of practice context [Citation25,Citation30], Kitson et al. [Citation11] proposed that the interplay of contextual factors that affect evidence use are reflected in the emerging unconscious assumptions, behaviours, relationships and feelings that characterize occupational therapists’ practice. Person-centred practice [Citation31] and complexity theories proposed that tacit (subconscious) elements of decision-making related to evidence use in practice require deep exploration through a critical lens, if their interaction with practice contexts and the subsequent complexities are to be understood.

Although current research suggests that contextual interplay affects occupational therapists’ engagement in a dynamic, reflexive EBP process, it remains unclear how it affects practitioners’ decisions, and which factors should be addressed in the particular context of community-based occupational therapy with people living with dementia in the United Kingdom. Schön [Citation32] suggested that practitioners’ awareness of contextual influences requires reflection-in-action, which exposes or unearths the social environments of practice (contexts) and enables understanding of the factors in the particular practice context that emerge and affect decision-making. This process is intended to raise consciousness of the contextual contradictions or paradoxes that limit the use of evidence as part of person-centred practice processes, and in furthering practitioners’ understanding of these, enabling them to engage constructively to facilitate occupation-focused decision-making.

Material and methods

Research questions

How do contextual layers and features interact with occupational therapists’ evidence-based practices and decisions?

What components of context need to be addressed to enable person-centred use of evidence in occupational therapy with people living with dementia?

Research design

A multiple method, qualitative case study methodology was designed to address the research aims. The design was underpinned by principles of critical creativity [Citation33,Citation34], which were included to facilitate reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action, in order to unearth the contextual interactions experienced by occupational therapists associated with using evidence. Naturalistic inquiry methods were used as the phenomena being explored, the underlying social landscape of practice that informs decisions about evidence use, were tacit in nature [Citation31]. This design enabled access to a realistic understanding of the emergence of complex interactions between the context and the use of evidence in practice, recognizing that the issues and practices that are reported do not always match what is actually done [Citation35,Citation36]. Integrating the methodological principles enabled representation of a case study [Citation37] of the use of evidence, comprised of comparisons between sub-cases. The case unearthed the complex and particular components of the practice context that affected how evidence was used.

Identifying and analysing the contextual conditions of practice required reflection on, and analysis of, multiple data that enabled description of artefacts and observable phenomena (what can be seen and heard), espoused beliefs and values (what is said but may not be observed), and assumptions underpinning approaches to practice (the principles underlying what is actually done) [Citation31,Citation32,Citation34]. Each type of data was constituted of a different kind of reflective knowledge, and thus creativity was required to express and blend these different forms of knowledge. Thus, the reflective processes underpinned each stage of the research, including: methodology development, data generation, analysis and data triangulation. Whilst the artefacts and practitioners’ values and beliefs were accessible through language and dialogue, assumptions underpinning occupational therapists’ actual actions were embodied or assimilated into practice subconsciously over long periods of time. To unearth the latter required deep exploration including observation, occupational therapists’ reflection while doing therapy, in combination with creative reflective methods. Examination of the emerging layers of reflection can expose the contextual issues that are of relevance in the particular practice contexts in which the researcher is immersed.

Researcher positioning

The principles of critical creativity [Citation33] position the researcher as a facilitator of reflection for action, and thus active in the research process. The researcher that led this study identified as a novice facilitator of reflective practice. Being active in the research required engagement in reflexion, in which the research processes and interactions were considered and changed in response to emerging knowledge and participant needs. This was achieved using a reflective diary, by critical dialogue with research supervisors, and through regular conversations about the research process with participants. Additionally, the researcher incorporated reflection on their engagement with participants as data for interpretation and analysis, recognizing these could have influence the participants reflective processes.

In action-orientated research the positioning of the researcher as ‘insider’ or ‘outsider’ can influence the research process, and any consequent findings [Citation38]. There are differing perspectives on the value of positioning [Citation39]. Fish and Coles [Citation39] have highlighted that ‘insider’ researchers, facilitators already known to participants and who share their practice context, may benefit from the existing relationship and values they share with participants. However, being an ‘outsider’ can be valuable in unearthing contextual phenomena that might not be visible ‘insiders’ in the practice context. Such outsiders must make their positioning and values explicit, to engage reflexively and develop facilitative relationships with participants. In this research, the researcher was positioned as an outsider, with a focus on person-centred evidence use. These values were made explicit in dialogical research processes with participants, in study information sheets and in the actual written development of the research.

The observations made by the researcher are also considered reflections, in that they are a perspective on the actual practices occurring from the perspective of the researcher. For this reason, the researcher’s reflections could not be extricated from the research and were also considered observational data. The researcher’s reflexive process was interpreted and analysed and is further considered in the methodological limitations.

Participants

Purposive sampling was undertaken to recruit participants from a pool of approximately twenty-five occupational therapists who had participated in education programmes and accreditation processes associated with specific interventions including the Tailored Activity Program (TAP) [Citation19] and Home-based Memory Rehabilitation (HBMR) [Citation40]. Potential participants also self-identified as using evidence from such interventions in community-based services in Scotland with people with dementia. Potential participants were identified by gatekeepers, who were positioned at the strategic leadership level of practice and were contacted by email through a national forum for allied health professionals who work at a strategic level to enhance therapeutic interventions in practice with people with dementia.

The aim of the study was to offer all occupational therapists from this pool the opportunity to engage in the study, for the purpose of developing understanding of a case, with a case considered to be a broad representation of the use of evidence in the chosen context and comprised of sub-cases of instances of occupational therapists’ practice and practice reflections over a period of three months. Generating multiple sub-cases of practice with research data was intended to contribute to comprehensiveness in the findings, as well as creating potential for comparisons of professional practices to be drawn [Citation36,Citation41]. The initial intention was to recruit approximately five participants. The final study took place with two occupational therapists after a number of potential participants withdrew after expressing concerns about the focus of the research questions. Whilst greater participation could have increased the quantity of the data and opportunity for comparison between sub-cases, high levels of immersion and enhanced opportunities to generate depth and quantity of data were realised.

Both participating occupational therapists had been working with people living with dementia for over five years. They worked in the same health board, as part of an older persons’ community mental health service. They were based in separate community hospitals, but shared local leadership and interactions with wider multi-disciplinary teams. These teams included: a consultant psychiatrist; dementia link workers; social workers; and nurses. Data was generated in the homes of persons living with dementia and in the organisational bases from which the occupational therapists worked. Participating occupational therapists acted as gatekeepers to purposively recruit people with dementia and their caregivers who had been referred to their service to the study. They and the researcher provided study information on an initial visit and returned if written consent to record therapy sessions was provided.

To achieve immersion in multiple practice scenarios, both participants were shadowed and observed intensively during different stages of their therapeutic processes with persons with dementia, with the stages observed chosen by the participants. This included immersion over an average of seven dispersed working days; observing, recording and discussing interactions from approximately twenty practice scenarios as summarized in . Given the intention to generate realistic cases of actual practice in action, it was not possible or appropriate to choose the nature of the observed practices prior to the research occurring. The challenges that practitioners previously reported with maintaining fidelity to process protocols derived for research purposes highlighted the possibility of limiting person-centred use of evidence by defining the components (e.g. assessment, intervention, goal-setting, evaluation) or form of intervention prior to the observation and reflection occurring [Citation14,Citation15]. Instead, the researcher assumed that the form of the intervention was dynamic in nature, and that standardization occurred in the function or underlying purpose of the evidence use [Citation24]. Thus, the nature of the practice observed included a combination of assessment (non-standardised), intervention (caregiver education, equipment provision) and evaluation processes (non-standardised).

Table 1. Nature of data.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this study was gained from NHS Scotland Research Ethics Committee (study ref no: 16/SS/0218). Informed written consent was sought and gained from all participating occupational therapists, and persons with dementia and caregivers whose therapy sessions were audio-recorded. A process consent approach was also taken, informed by a relational ethics perspective, which enabled reflexivity in ethical decision-making that could not be supported by universal ethical procedures alone [Citation42,Citation43]. Occupational therapists’ consent was considered on a continuing basis and all participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage of the research process without giving reasons, and with a choice about whether their reflections and observed therapy sessions were shared.

Methods

A combination of methods, including: ‘Think Aloud’ [Citation44], practice observation and creative expression was used in this research to elicit both primary data, and generate reflective dialogue.

Think aloud

Occupational therapy sessions were audio-recorded if the person with dementia and/or caregiver gave informed written consent. ‘Think Aloud’ is a method in which the occupational therapist is asked to verbalize their reasoning and decision-making processes while they are doing therapy to unearth their reflections-in-action [Citation31,Citation43]. The purpose of this was to make reflective decisions, which consisted of information about unconscious assumptions attached to their therapeutic approach, available for discussion and subsequent interpretation.

Observation

As occupational therapists were engaging in therapeutic sessions and doing ‘think-aloud’ [Citation43], the researcher was using a ‘see/hear, feel, imagine’ framework [Citation45] to structure observations and to facilitate foregrounding or emergence of pertinent aspects of practice for subsequent reflection-on-action. The components of the framework held multiple purposes. The ‘see/hear’ component enabled descriptions of the approach to therapy to be made. The ‘feel’ and ‘imagine’ components enabled to researcher to express embodied knowledge or assumptions they made about the approach.

Creative expression

Accessing and making tacit elements of practice explicit, such as the therapists’ embodied understanding of their role, can identify the components of context that influence decisions [Citation33]. Creative methods can enable dialogue that bypasses or avoids rationalizing therapeutic approaches and responses to contextual challenges, instead allowing articulation of tacit knowledge about decisions that are made about the use of evidence in response to context [Citation46]. In this research, painting and drawing, and Evoke Cards [Citation47] were used to do this. Evoke cards [Citation46] are a collection of photographs that are designed to call to mind emotions, memories, and thoughts about an experience. Participants were invited to use creative methods such as drawing and Evoke Cards [Citation46] to express their own thoughts and feelings about therapy sessions both before and after they took place. The researcher also incorporated creative processes of painting and/or drawing to express and supplement the ‘feel’ and ‘imagine’ components of the observation framework [Citation44].

Reflective diary

The researcher kept a reflective diary to describe and analyse components of practice and contextual phenomena that were apparent but not discussed due to challenges with research engagement, and these are explored in the findings. The reflective diary also facilitated reflexivity within the research process, particularly when adapting data generation processes to meet the needs of participating occupational therapists.

Critical creative dialogue

Data recorded from the ‘think aloud’ technique [Citation43], observations [Citation44], and creative expressions [Citation32] were used to generate reflective dialogue with participants about their evidence use, therapeutic practices, and the contexts in which they took place. This dialogue was audio-recorded for inclusion in the final data set. The following example illustrates the creative reflection in action:

Researcher: I chose this image of a tightrope walker because it felt and looked like you were trying, and maybe struggling, to make a decision about the information that you shared and provided during the session. Could you tell me more about that process and what you felt and thought?

As information generated during the process of therapy in action was used to stimulate the reflective dialogue, the data collection involved a concurrent interpretation and analysis process.

Method triangulation

Each practice interaction generated a different combination of data. For instance, in a situation where there was not consent to audio-record the session, transcripts included reflective dialogue after the session, written observations of the session and researcher’s reflections on these data. In cases where there was written consent to audio-record the therapeutic interaction, the data included transcripts of the ’think aloud’ [Citation43] (reflection-in-action) process, written observations of the session, transcripts of reflective dialogue following the session, and the researcher’s reflections of the process and data. As the observations took the form of creative expressions and the reflective dialogues were often generated through creative expressions, the creative methods were incorporated into each method used.

Data analysis

Data from twelve separate therapy sessions over a fourteen-week research period, including nine practice observations, two ‘Think Aloud’ [Citation43] practice transcripts, six creative expressions, ten transcripts of reflective dialogue, and ten researcher reflections were analysed.

Data were analysed using Creative Hermeneutic Analysis [Citation48]. This analytic approach can be used with multiple forms of data including that underpinned by a critical creative methodology and is derived from hermeneutic phenomenology [Citation49], which understands inquiry as a way of enabling questioning of assumptions embedded in experience [Citation50]. Like the creative data generation, the analysis process involved using creative methods to enable the researcher to experience the data as a whole and to develop an intuitive grasp of the contextual phenomena that emerged in the data. This creative immersion enabled identification of natural connections and frictions between the themes and the different forms of data, facilitating triangulation of data generated from multiple methods and perspectives. In creative hermeneutic analysis, this intuitive interpretation is reflected through creation of an image (in this case, a sculpture), which holds the researcher’s conceptualisation of themes and sub-themes of the data, and the connections between them.

In this research, the initial phase of analysis involved triangulation of multiple forms of data. First, an initial grasp of the data was developed by the primary researcher through immersion, which involved re-listening to audio-recordings of therapy sessions and reflective dialogue, re-reading practice observations, creative expressions and the reflective diary. Second, a reflective dialogue occurred with the research supervisors in which the researcher’s general grasp of the information was shared. A sculpture was created by the researcher and supervisors during this dialogue, which represented main themes intuitively perceived by the researcher and research supervisors. Third, the sculpture was discussed, identifying and describing the themes contained within the image. This discussion was recorded for the researcher to complete the fourth step of prolonged re-immersion and coding of the data using the main themes identified in the third step. Finally, raw data representing the themes and sub-themes were arranged and recorded in text to reflect the narrative of the sculpture in a case study.

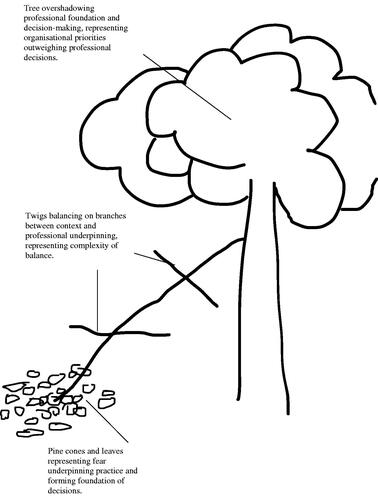

The sculpture, created for the purpose of delineating the essence of the research findings, was created in silence in a natural space (a public park), with the use of nature in creative research believed to unearth embodied knowledge about an issue, which is not possible to access through dialogue alone [Citation33]. It is reflected in , with each component of the sculpture representing the themes emerging from the data. For instance, the balancing twigs on the branches represent the challenges experienced with balancing organisational values with professional values when using evidence in practice. The other theme that emerged, fear, was reflected in a group of cones and leaves that formed an unstable foundation for the core branch of the sculpture. Discrete subthemes related to these themes emerged in the reflective dialogue about the sculpture and coding the data.

Findings

This case of evidence use in community-based practice with people with dementia was developed with data generated from two occupational therapists’ practice, referred to as Mary and Emma, and the researcher, referred to as R.

The case is a presentation of two primary and linked themes, fear and balance each composed of three discrete subthemes. The first theme fear and its’ subthemes represent data reflecting cultural challenges (shared professional ways of thinking) that either elicit fear or manifest in decision making that was risk-orientated, and compliance driven. The second theme balance and its’ subthemes represent data that describe the various challenges of negotiating decisions in relation to organisational features of context. The sense of fear, and related challenges with balance, emerged as issues that influenced person-centred use of evidence.

Culture of fear

The theme of ‘fear’ and the sub themes related to it describe the perceived emotional underpinnings related to participants’ experience of contextual challenges that affected decisions about their approach to evidence use. These have been categorized as fear for professional identity and fear of risk-taking. The emotional responses were identified using the creative interpretive method of analysis and the subthemes described using the subsequent cognitive responses and actions observed using other methods. These interpretations of underlying emotion related to the challenges were made by the researcher and the emotion underlying the related evidence may be perceived differently by readers.

Fear for professional identity

Concerns about professional identity and role were evident in occupational therapists’ dialogue and the researcher’s reflections. These concerns appeared to influence both the way that occupational therapists used the evidence-based intervention resources that had been introduced to them during the EBP education, and their relationships with colleagues. Emma highlighted that she found decision-making difficult because of these concerns. The difficulty appeared to relate to negotiating the role that each team member plays in educating and providing information to the person with dementia.

Emma: The other thing is that you don’t want to tread on the toes of a dementia link worker who also provides that kind of information. I don’t know…

During a discussion that occurred between Mary and Emma and the researcher in the early stage of the research, their fear of losing professional identity and role of providing occupation-focused therapy emerged as motivators of compliance-orientated evidence use, or an approach to evidence use in which the research evidence is applied in a procedural, technically orientated manner.

R: They openly discussed how, when they did the TAP [Citation19] [education], they had felt that it was just occupational therapy, that had been made into a protocol… During this discussion, the concern that emerged was that even though [Mary and Emma] know that what they are doing is just occupational therapy, they are worried about the impact that sharing this information [or perspective] will have on referrals to occupational therapy services.

This observation reflected a recognition made by participants that they used the structure and titles of research based interventions as a proxy to represent the potential occupational therapy role within their teams. However, the reflection also indicated that Mary and Emma questioned the therapeutic value of using evidence-based interventions in this way, and that they complied with processes derived from research protocols to maintain survival in their practice context. This attitude towards evidence use was later evident in their use of evidence in action (see following section balance).

Managing risks

Participants weighed up decisions about their occupation-focused use of evidence based on risk. This way of thinking subsequently informed the practitioners’ understanding of the purpose underpinning their decisions about use of evidence-based resources, such as the TAP [Citation19], HBMR [Citation39] and the Rookwood Battery Driving Assessment [Citation51]. For instance, Mary shared a reflection on her decision to use the latter, an evidence-based assessment tool, to identify the level of risk involved in driving.

Mary: Well he was referred for HBMR [Citation39]…I gave him information on the programme, he felt he was- he had his own strategies and it wasn’t a thing he wanted to engage with and at that point he started telling me about, you know, the dizzy- if he moved quick he’d get dizzy and I just started to wonder if, you know like- what if that happened in the car? Things like that. So we got talking about his driving and he said that he had to tell the DVLA about his diagnosis and he really felt okay with his driving. His wife did too.

Emma highlighted discomfort at supporting risk-taking with the physical environment following an observational assessment informed by the TAP [Citation19].

Emma: …you want them to be able to do that as safely as possible. I would feel more comfortable knowing there was something there that he could hold on to. Even on the way back in he put his hand on the hinges of the door and if that door had blown closed he’d have had his fingers trapped so I’m really not comfortable with him doing that.

Both reflections acknowledged the use of assessment, both evidence-based and otherwise, as a way of identifying risk. In one situation, the awareness of risk was weighed with evidence from the family and a resulting decision made not to address the occupation any further. In the other situation, with another occupational therapist, Emma, a decision was made to avoid occupations because of risk in the physical environment.

Despite different concerns for both occupational therapists, risk consideration was the foundation of their assessment and decisions about their intervention. This focus contrasted with the espoused purpose underpinning the evidence-based interventions noted earlier, which is to enhance occupational engagement. These espoused purposes were not always observed in the instances of practice described, with evidence-based assessments and processes being used to assess risk instead, or to limit occupations that are inherently risky for people.

The orientation towards risk as a foundational way of thinking suggested that the challenges negotiating the complexities of the broader practice culture, and of engaging in reflection-in-action, resulted in approaches that did not always align with the occupation-focused theories underpinning the interventions they were educated to use [Citation16–19].

Balance

The professional culture and associated fears observed and described by occupational therapists influenced the way they balanced decisions and negotiated competing contextual pressures in practice. This emerged as participants were caught between perceived pressure to approach evidence use in a compliance-orientated way and to engage and develop their own professional reasoning and values. The participants appeared ‘stuck’, such that their interventions were primarily informed by a focus on the procedure or process of applying evidence and the decision-making power of other professions and professionals.

Balancing process with outcome

Occupational therapists often focussed their practice on prescriptively applying the protocol of the evidence-based intervention they were using to inform their practice, with limited explicit consideration of the purpose of the intervention or the intended outcome for the person with dementia. For instance, Emma described maintaining compliance with a series of steps outlined in the HBMR [Citation39] resource pack to guide her decision-making with a person who had recently received a diagnosis of dementia.

Emma: Usually I am not keen to move onto the next HBMR [Citation39] session until I think that everything in session one is completely clear.

She acknowledged the complexity and challenge of being flexible with the evidence use, processes and resources.

Emma: Em, just adapting it [HBMR [Citation39] intervention] so it suits people I think. Which can be really tricky… It’s difficult I think with that to still know how much [information] to give somebody and how much not to give them.

Emma’s reflections highlighted a perceived need to apply the practice resources in a prescriptive or compliant way. The perceived need to comply with the suggested stages of the HBMR [Citation39] resource pack, adhering to pre-defined processes, suggested that Emma’s conceptualization of EBP was one of techne. This understanding of EBP influenced way that the practice process and outcome were balanced by the occupational therapist. This kind of approach was also observed in practice.

R: [Emma] checked in with how much he was engaging in the strategies that she had suggested or prescribed [from the HBMR [Citation39] resource pack] to which he consistently said that he found it difficult as he is not a list keeping type of person…He began to speak about some of his interests… I saw [Emma] redirect his attention to the task… the memory book.

Emma’s reflection and the researcher’s observations indicated that the focus on the fidelity to a practice protocol had resulted in the privileging of technical, research-derived processes over the intended occupational outcome of the interventions. Emma noted the complexity of engaging in reflexive processes of practice required to be person-centred, such as blending clinical evidence with evidence of the person, and adjusting the evidence use to the person’s context.

The complexity of blending different forms of evidence could have been related to the cultural challenge with maintaining professional identity, rather than to occupational therapists’ actual ability or potential to engage this approach to EBP. This was reflected in the data, in which Mary was observed and reflected on a ‘balanced’ practice process, resolving to use the evidence-based resources in a person-centred way.

Mary: I did the LACLS [the Large Allen Cognitive Level Scree n [Citation52] but I kind of- often times I don’t sort of do everything on the LACLS and it’s everything- how she made her tea, how long she concentrates for, how she settles down after a wee period of time… I judged it on that. Like an amalgamation of everything I’ve seen of her and everything I’ve heard.

This indicated Mary’s ability to engage a person’s experience and interests as evidence to inform practice, and to prioritise her professional reasoning. This was achieved by blending propositional knowledge, like the LACLS [Citation51], with experiential knowledge and knowledge about the person to create a unique therapy plan that is better suited to the individual and the specifics of their context. This data also emphasized the impact that cultural assumptions regarding practice had on participants actions, despite having the potential and ability to use evidence in different, reflexive ways.

Balancing technical and relational practice

Although compliance-orientated evidence use and risk-orientated practice was evident, both occupational therapists’ reflections indicated an awareness of the potential insufficiency of technical approaches. For example, both discussed the issues with using evidence such as intervention resources (activity prescription templates and memory books) without an understanding of their value in relation to peoples’ occupational lives.

Emma: …yeah, you could be writing down in it every day but not ever going back to look at it or ever needing to look back over it or get any benefit from looking back over it- you’re almost doing it more like a chore than something that’s actually helping you. In which case, people, I find, try to pacify me throughout the programme that they’re writing in it. And then once I stop visiting, they’ll stop writing in the book because nobody’s coming to check up on them almost.

Mary: I just wondered if there was…you know further assessment to look at creating another activity prescription around something in the home which I thought might be quite helpful. But having said that… their life is quite filled with family… so, yeah. We’ll just have to gauge… if [the activity prescription is] just another thing and she could do with just seeing her family, then fair enough.

This data indicated participants’ understanding of the issues with technical approaches to evidence use and highlighted relational espoused practice values that were not consistently evident in their actions. However, their awareness did not always change their approach. This ‘stuckness’ illustrated the practical challenges associated with the complexity of using evidence in balanced ways, that is, by integrating it with their understanding of the person and their own professional expertise. This, along with the cultural challenges suggested that other contextual issues fostered such technical practices and might need to be addressed by the therapists, using reflective processes to underpin more judicious use of evidence-based intervention resources.

Reflection for balance

An observation was made of a process in which relational values were balanced with technical approach to EBP. This balancing of priorities occurred through use of the occupational therapists’ reflective way of being and enabled a shift in attention from prescribed activity to occupation.

R: ‘Mary asked about the prescribed [TAP [Citation19] activity prescriptions] occupation, which was colouring. The woman [living with dementia] said she did not want to do it and it was not for her…She [Mary] checked that the woman was happy enough continuing to go about her daily life, watch television and going for a walk in the evening to the place her mother used to stay. At this point, Mary noticed that the discussion about her walk and her mother brought her a lot of joy and Mary appeared to be sitting back, thinking… Mary asked whether she had any photographs…and the woman became more engaged in the conversation…’.

The observational data highlighted the reflective processes required for professional artistry to emerge and for a ‘letting go’ of the compliance-orientated use of resources derived from research evidence. Although the data did not include information about the contextual features that facilitated the shift in ways of being and thinking, it emphasized the conditional nature of occupation-focused decision making. The condition evident in this data was the explicit use of reflection and thought during practice, which emphasized the ability of participants to address contextual limitations to person-centred evidence use through reflection.

Balancing power

Although balance was sometimes observed in practice when cultural challenges were overcome, the data indicated that limitations to professional power and autonomy affected occupational therapists’ choice about the way they used evidence-based resources. This was most evident in Mary’s reasoning for use of a Rookwood Battery Driving Assessment with a person who did not identify occupational concerns with driving.

Mary: …he really felt okay with his driving. His wife did too. He said he would consider doing the Rookwood Off-Road Driving Battery and, you know, just to see what the outcome and if there were any areas we could look at… I think it’s probably a thing for the future… I just thought it was an opportunity to do the Rookwood baseline at this stage, you know?

The researcher also reflected on the power related influences on this instance of practice.

R: …she [Mary] did speak about the driving assessment that I had observed…She spoke about how the consultant psychiatrist that she would be working with was keen that she and Emma do a pilot study on the Rookwood driving assessment…

These reflections and observations indicated that decision-making was a least partially informed by a service driven target for evaluation of evidence. This phenomenon meant that decisions made by other healthcare professionals that Mary and Emma perceived as more powerful, but with limited understanding of occupation-focused reasoning, influenced their approach to using evidence, with this becoming a practice priority. It highlighted occupational therapists’ valuing of other professions’ processes and strategic service priorities over their own, which may have contributed to the limited opportunities to use evidence in a more person-centred manner.

Discussion

The findings of this research indicated that the features of context that affected how occupational therapists used evidence include: professional culture, organisational culture relating to evidence-based practice, and organisational challenges relating to team identities (roles) and relationships. The findings indicated that the interplay between the occupational therapists’ professional practice and the organisational features created tensions that introduced uncertainties in their professional decision making and actions. The findings suggested that the tensions between features that foster these issues included: understandings of EBP (culture), professional power imbalances influencing decision making (organisation-meso), ownership and articulation of professional knowledge (professional and organisational context), and organisational approaches to evaluation (organisational-meso and macro). The responses to such tensions manifested differently in practice including in a loss of occupation focus and person-centredness, which was evident in the descriptions of instances of practice. The findings also highlighted the paradox inherent in the contextually informed choices occupational therapists made to use evidence in compliance and risk-oriented ways despite shared values of person-centredness and occupation-focused practice.

The compliance-orientated approach to evidence use that emerged in this practice context can be referred to as techne, or practice that is governed by rules and instrumental action, rather than phronesis, which is practice informed by the needs of a persons’ particular situation [Citation53]. This discourse may foster compliance-orientated practice cultures if practitioners misinterpret the concept of EBP as requiring the prescriptive application of research evidence [Citation52]. Greenhalgh and Howick [Citation12] suggested that the emphasis on experimental evidence in healthcare research, which enables development of technically-orientated practice processes that are standardised, safe, and cost-effective, also has unintended consequences. In particular, they argued that the EBP movement can devalue the contribution of tacit knowledge derived from practice experience, overlook the complexities of professional decision making, and foster intolerance of uncertainty in practice. Consequently, practitioners experience challenges balancing evidence-based ‘rules of thumb’ with their professional expertise, and the occupational needs of the person, which can impact on the quality of care people experience.

Similar to the culture of compliance-orientated EBP, the decisions made by participating occupational therapists to address risks associated with occupation using evidence-based tools, sometimes at the expense of a focus on the persons’ occupational needs, is reflective of a professional culture that does not always enable use of professional philosophy in practice. The ‘inescapable tension between the pursuit of safety and the pursuit of other healthcare priorities’ [Citation54,p.12] has been recognized in healthcare reports, with Berwick [Citation12] having suggested that balance should be found between professional and service-driven safety priorities. He proposed that this is achieved through dialogue about risk-taking and recognition of the imbalance of priorities. The instances of evidence use in practice in which risk-orientation emerged as a priority, despite occupational therapists’ education to use research evidence to enhance occupational engagement, highlighted pressures they experienced negotiating healthcare contexts that appeared inherently focussed on maintaining physical safety. This finding emphasized that adopting occupation-focused practices through positive risk-taking can conflict with the culture of an organization. It has been argued that practice that is focussed on maintaining safety may come at the expense of addressing persons’ occupational priorities and needs [Citation55]. For persons living with dementia this may consequently increase the risk of occupational deprivation.

Whilst it has been acknowledged that a certain level of compliance with safety procedures is required to achieve minimum safety standards [Citation12,Citation56], Berwick [Citation12] and Dewing [Citation55] contended that a sole focus on using evidence-based processes for the purpose of maintaining safety will not enable holistic well-being, an espoused philosophical principle of occupational therapy practice. Rather, it is believed to reflect an emphasis on broad organizational priorities [Citation12,Citation55], instead of on the micro, professional level of practice, that is, the occupational priorities of the person with dementia. Extending this theory, Manley et al. [Citation57] argued that attitudes towards practice, particularly risk-orientated practices, are interrelated with teams’ relationships and team effectiveness. They suggested that team-based strategies that optimize holistic decision-making include clarity of purpose and respectful interprofessional relationships. It could be argued that the hierarchical interprofessional relationship referred to between occupational therapist and consultant psychiatrist affected consistent decision-making about professionally aligned, occupation-focused evidence use in this practice context.

Clarity of purpose requires therapists to consider the intended outcomes when using research evidence. Evaluation practices, including processes of defining, reflecting on, and auditing the intended outcomes, are believed to be more effective in facilitating evidence use when there is an internally derived component to evaluation [Citation11,Citation13], meaning that occupational therapists make explicit choices about the aims of their evidence use. This form of evaluation embeds a professionally authentic lens in evaluation. In this study, externally derived outcomes appeared to drive occupational therapists’ decisions, which impacted on their ability and motivation to clarify the purpose of their actions, or to reflectively consider the occupational focus in their decisions. For example, occupational therapists’ use of an assessment for the purpose of service-driven outcome measurement affected their need to clarify the occupational foundations of their ideas. This service driven focus resulted in challenges with clarity of professional identity, with occupational therapists relying on the technical process of using the evidence rather than on the occupation-based use of the evidence to articulate their professional focus.

Occupational therapists’ awareness of the insufficiency of technically-orientated approaches to evidence use alone, alongside evidence of their ability to use the intervention resources reflexively, suggested that they perceived an expectation to use evidence in a procedural way. Thomas and Menage [Citation58] acknowledged that practitioners’ compliance with strict procedures, such as the use of an intervention package, can be beneficial in acquiring recognition for occupational therapy, which Laloux [Citation59] suggested creates impetus to conform to processes and behaviours that are sometimes ineffective. Perryman-Fox [Citation60] described the tensions of using evidence in compliance-orientated ways for the purpose of generating role clarity and power as a negotiation of ‘occupational agency’. This is a process in which practitioners weigh the expectations of ‘the system’ with their own personal and professional values and expectations, either taking reflexive action or experiencing ‘freeze’, in which decisions are not reflexively informed. Senge [Citation61] and Schein [Citation62] described the latter as a coping mechanism to ensure survival when identity is threatened, by aligning with external, organizational expectations. This phenomenon was observed in the challenges occupational therapists reported in choosing courses of action about the way that evidence was used in practice, as well as in the concerns about identity loss.

The conditional nature of realizing occupation-focused practice was evident in this research, with reflexively informed, occupation-based decisions only occasionally realized. An observational finding indicated that stillness, reflection in practice, enabled a move from technically-orientated evidence use to occupational agency. Scharmer [Citation63] referred to this as letting go of ‘the voice of fear’ of losing membership of a professional group by challenging norms like technically-orientated EBP or hierarchical team decision-making. In a study of reflection in practice, Krueger et al. [Citation64] identified occupational therapists’ belief that reflection in practice should help to understand and negotiate the practice context but that they also lacked awareness of theories and models that could support reflection.

In this research context, although some moments of reflection appeared to influence the emergence of relational, occupation-focused practice, this was not consistent and reflective awareness of the issues did not always enable change in occupational therapists’ actions. Restall and Egan [Citation65] recently highlighted that consistent reflection is required to unearth or raise consciousness of the ways that occupation-based therapeutic relationships are undermined by the social structures and policies of an organisation, and that mapping of decision-making power within a team can offer opportunities for change in practices. McCormack and Titchen [Citation31], and Fay [Citation66] suggested that this reflective process should begin by raising consciousness of the practices and traditions that are incongruent with practitioners’ professional values and beliefs.

Methodological considerations and limitations

The main limitation of this research lies in the quantity of data derived from practitioners’ reflections and its reliance on observational and reflective accounts made by the researcher to convey contextual challenges occupational therapists experienced. Although ‘outsider’ researcher reflections can provide valuable insights into the challenges that practitioners experience in exploring their practice context and sharing their practice culture [Citation38], these challenges have not yet been verified by occupational therapists who share this practice focus.

The quality and quantity of data used to describe context and cultural phenomena is limited, due to issues with research engagement and low participant numbers. Although outsider researchers’ perspectives are believed to be necessary to verbalize, and provide insights about embodied cultural phenomena that are usually invisible to those embedded in the practice context, they need to pay close attention to their awareness of, and responsiveness to practice context in order to build psychologically safe, facilitative relationships with practitioners, such that they can share their practice and discuss practice context [Citation45]. These processes could have been more adequately addressed through development of relational methodological principles in such action-orientated research.

The intention of defining the cultural phenomena through a case of practice in action was not to generalize findings to other practice contexts but to define the particularities of practice situations. Defining particularities can emphasize the complexities and paradoxes that are inherent in the contexts that influence approaches to evidence use and that require attention to support future education [Citation40]. By exploring these, the reader is offered the opportunity to identify similarities or differences with their contexts and to use the theorizations made to make judgements about approaches to evidence use in their own contexts [Citation36].

Conclusion

This research demonstrated that organisational features of the practice context can create tensions for occupational therapists in using research evidence to create occupation-focused therapeutic processes. Tensions can emerge between occupational therapists’ actual abilities and their perceived freedom to make occupationally informed decisions about their approach to practice when multiple, competing service demands exist within a team. The contextual demands that specifically influenced occupational therapists’ practice included: teams’ approaches to outcome measurement, services’ tolerance of risk-taking, and team power dynamics in decision making. These demands often culminated in cultures that valued technical use of research evidence, and in which occupational therapists experienced uncertainty about how to negotiate the competing demands of their professional values and those of their team and organization.

Despite awareness of the influence of contextual demands on their professional decisions and philosophy, occupational therapists’ experienced professional benefits of aligning with team and organisational cultures rather than professional cultures, specifically in enabling them to maintain their professional identity and relationships with team members. However, the research also highlighted occupational therapists’ potential and desire to be practitioners that use research evidence in person-centred ways to facilitate occupation. Achieving this in practice was conditional upon the process of balancing organisational and professional priorities, which in the studied context was realized through reflection during therapy. Explicit decisions to take time and space for reflection-in-action, particularly in silence and stillness, can enhance therapists’ opportunities for reflexivity (responsiveness to context) to enact professional values. However, this was not consistently realised, with occupational therapists’ reflection on the power dynamics inherent in the social structures of their teams and organisations required to develop perceived freedom in their use of evidence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Prince M, Wimo A, Guercher M, et al. World Alzheimer report 2015: the global impact of dementia an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015.

- Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997.

- World Health Organisation. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2017.

- Scottish Government. Scotland’s national dementia strategy 2017–2020. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Government; 2017.

- OECD. Renewing priority for dementia: Where do we stand? Paris: OECD; 2018.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International, Bupa. Ideas and advice on developing and implementing a national dementia plan. London: AlzInt; 2013.

- Alzheimer Scotland. Delivering integrated dementia care: the 8 pillars model of community support. Edinburgh, UK: Alzheimer Scotland; 2012.

- Upton D, Stephens D, Williams B, et al. Occupational therapists’ attitudes, knowledge, and implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic review of published research. Br J Occup Ther. 2014;77:24–38.

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312:71–72.

- Dougherty DA, Toth-Cohen SE, Tomlin GS. Beyond research literature: occupational therapists’ perspectives on and uses of “evidence” in everyday practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2016;83:288–296.

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Approaches to implementing research in practice. Qual Health Care. 1998;7:149–58158.

- Greenhalgh T, Howick J. Evidence-based medicine: a movement in crisis? Br Med J. 2014;348:7.

- Rogers L, De Brun A, McAuliffe E. Defining and assessing context in healthcare implementation studies: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:591.

- Hunter PV, Hadjistavropoulos T, Thorpe L, et al. The influence of individual and organisational factors on person-centred dementia care. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:700–708.

- Di Bona L, Wenborn J, Field B, et al. Enablers and challenges to occupational therapists’ research engagement: a qualitative study. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:642–650.

- Hynes SM, Field B, Ledgerd R, et al. Exploring the need for a new UK occupational therapy intervention for people with dementia and family carers: community Occupational Therapy in Dementia (COTiD). a focus group study. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:762–769.

- Wenborn J, Hynes S, Moniz-Cook E, et al. Community occupational therapy for people with dementia and family carer (COTiD-UK) versus treatment as usual (valuing active life in dementia [VALiD] programme): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:10.

- Voigt-Radloff S, Graff M, Leonhart R, et al. A multicentre RCT on community occupational therapy in Alzheimer’s disease: 10 sessions are not better than one consultation. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000096.

- Graff MJL, Vernooij-Dassen MJM, Thijssen M, et al. Community based occupational therapy for patients with dementia and their care givers: randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2006;333:1196.

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, et al. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:229–239.

- Novelli NNPC, Machado SCB, Lima GB, et al. Effects of the tailored activity program in Brazil (TAP-BR) for persons with dementia: a randomized pilot trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32:339–345.

- O’Connor CM, Clemson L, Brodaty H, et al. Use of the tailored activities program to reduce neuropsychiatric behaviors in dementia: an Australian protocol for a randomized trial to evaluate its effectiveness. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:857–869.

- Dooley NR, Hinojosa J. Improving quality of life for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and their family caregivers: brief occupational therapy intervention. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:561–569.

- Morgan-Trimmer S, Kudlicka A, Warmoth K, et al. Implementation processes in cognitive rehabilitation intervention for people with dementia: a complexity-informed qualitative analysis. Br Med J Open. 2021;11:e051255.

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:267–276.

- Pentland D, Kantartzis S, Giatsi Clausen M. Occupational therapy and complexity: defining and describing practice. London: Royal College of Occupational Therapists; 2018.

- Greenhalgh T. How to implement evidence-based healthcare. Oxford: Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Taylor C. Evidence-based practice for occupational therapists, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

- Bolt T, Huisman F. Towards person-centered healthcare via realistic evidence-based medicine- informing the debate historically. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2015;3:275–278.

- McCormack B, Kitson A, Harvey G, et al. Getting evidence into practice: the meaning of ‘context’. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38:94–104.

- McCormack B, McCance T. Chapter 2: underpinning principles of person-centred practice. In McCormack B, McCance T, editors. Person-centred practice in nursing and health care: theory and practice, 2nd ed. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 13–35.

- Schön DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.; 1987.

- McCormack B, Titchen A. Critical creativity: melding, exploding, blending. Educ Action Res. 2006;14:239–266.

- Titchen A, McCormack B. Dancing with stones: critical creativity as methodology for human flourishing. Educ Action Res. 2010;18:531–554.

- Wilson V, McCormack B. Critical realism as emancipatory action: the case for realistic evaluation in practice development. Nurs Philos. 2006;7:45–57.

- Morgan SJ, Pullon SRH, MacDonald LM, et al. Case study observational research: a framework for conducting case study research where observation data are the focus. Qual Health Res. 2017;27:1060–1068.

- Simons H. Case study research in practice. London: SAGE; 2009.

- Van Lieshout F, Cardiff S. Reflections on being and becoming a person-centred facilitator. Int Pract Dev J. 2015;5:S1–S10.

- Fish D, Coles C. Developing professional judgement in healthcare: learning through the critical appreciation of practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998.

- McGrath M, Passmore P. Home-based memory rehabilitation programme for persons with mild dementia. Irish J of Med Sci. 2009;178:S330.

- Stake RE. The art of case study research. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 1995.

- Dewing J. Process consent and research with older persons living with dementia. Res Ethics Rev. 2008;4:59–64.

- Finlay L, Evans K. Ethical dimensions of relational research [internet]. 2008 [cited 2018 Jul 14]. Available from: http://lindafinlay.co.uk/

- Bucknall T, Aitken LM. 2015. Chapter 32: think aloud technique. In: Gerrish K and Lathlean J, editors. The research process in nursing, 7th ed. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 441–453.

- Dewing J, McCormack B, Titchen A. Practice development workbook for nursing, health and social care teams. Hoboken: Wiley; 2014.

- Titchen A, Cardiff S, Biong S, et al. Chapter 3: the knowing and being of person-centred research practice across worldviews: an epistemological and ontological framework. In McCormack B, Van Dulmen S, Eide H, Skovdahl K, editors. Person-centred healthcare research. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell; 2017. pp. 31–50.

- Stokes J. Evoke Cards. [photographs]. DJ Stotty Images; 2017.

- Boomer CA, McCormack B. Creating the conditions for growth: a collaborative practice development programme for clinical nurse leaders. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:633–644.

- Gadamer H. Truth and method. Weinsheimer J, Marshall DG, translators. London: Bloomsbury; 1975.

- Van Manen M. Serendipitous insights and Kairos playfulness. Qual Inq. 2018;24:672–680.

- McKenna P. Rookwood driving battery. US: Pearson; 2009.

- Allen CK, Austin SL, David SK, et al. Manual for the allen cognitive level screen (ACLS-5) and large allen cognitive level screen- 5 (LACLS-5). Camarillo, CA: ACLS and LACLS Committee; 2007.

- Boniface G, Seymour A. Using occupational therapy theory in practice. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

- Berwick D. A promise to learn- a commitment to act: improving the safety of patients in England. England: National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients; 2013.

- Du Toit S, Shen X, McGrath M. Meaningful engagement and person-centred residential dementia care: a critical interpretive synthesis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26:343–355.

- Dewing J. Assuring care: are we ready to move beyond compliance measurement against targets? Int Pract Dev J. 2015;5:1–2.

- Manley K, Jackson C, McKenzie C. Microsystems culture change: a refined theory for developing person-centred, safe and effective workplaces based on strategies that embed a safety culture. Int Pract Dev J. 2019;9:1–21.

- Thomas Y, Menage D. Reclaiming compassion as a core value in occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79:3–4.

- Laloux F. Reinventing organizations: a guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage in human consciousness. US: Nelson-Parker; 2014.

- Perryman-Fox MS. 2020. A theory of occupational agency: an international investigation of occupational therapists’ negotiations [unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Lancaster University.

- Senge P, Scharmer OC, Jaworski S, et al. Presence: exploring profound change in people, organizations and society. 2005. London and Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Schein E. Organisational culture and leadership. San Francisco; CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

- Scharmer OC. Theory U: Leading from the future as it emerges, 2nd ed. 2016. Oakland, CA: Berett Koelher.

- Krueger RB, Sweetman MM, Martin M, et al. Self-reflection as a support to evidence-based practice: a grounded theory exploration. Occup Ther Health Care. 2020;34:320–350.

- Restall G, Egan MY. Collaborative relationship-focused occupational therapy: evolving lexicon and practice. Can J Occup Ther. 2021;88:220–230.

- Fay B. Critical social science. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1987.