Abstract

Background

Adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face multiple challenges in obtaining and maintaining employment.

Aims

To identify and describe how adults with ADHD or ASD experienced their ability to work and what factors affected their ability to find a sustainable work situation over time.

Methods

Individual in-depth interviews were performed with 20 purposively sampled participants with ADHD/ASD. Data were analysed inductively using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

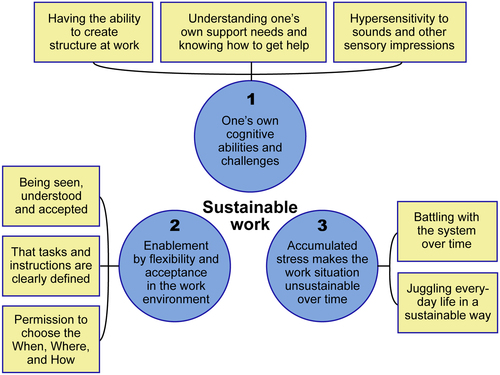

Three themes were identified, describing (1) one’s own cognitive abilities and challenges, (2) enablement by flexibility and acceptance in the work environment, and (3) accumulated stress that makes the work situation unsustainable over time.

Conclusions

Over time, a lack of continuity and predictability of support measures caused great stress and exhaustion, with severe consequences for working life and in life in general. Adaptations needed to be individually tailored and include nonoccupational factors.

Significance

The study shows that adults with ADHD/ASD need long-term interventions that flexibly adapt to individual needs, as they vary over time. The findings suggest that occupational therapists and other health care providers, employers, employment services and other involved agencies should pay a greater deal of attention to stability and predictability over time.

Introduction

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are common conditions, with an estimated global prevalence of 1.1 and 0.4%, respectively, in 2019 [Citation1]. The conditions commonly occur together [Citation2–4], with 30–50% of individuals with ADHD having ASD [Citation5] and 50–70% of individuals with ASD having ADHD [Citation6]. Symptoms show large individual variability and some, such as executive difficulties, are common in both conditions [Citation4]. Individuals with ADHD or ASD often struggle to achieve a sustainable work situation [Citation7–10]. In this article, work is conceptualised as obtaining and maintaining work and is seen in a context that also includes the person and the environment [Citation11]. Work often occupies a large and central part of adults’ lives, and working is strongly related to better health [Citation12]. Having a job contributes to financial independence, self-confidence, social connection, daily commitment, and health [Citation13]. At the societal level, increased employment indirectly leads to decreased costs.

About 70% of Swedish adults with ADHD and/or ASD rated their ability to work as reduced [Citation14]. More than a third of adults with ADHD/ASD receive sickness compensation, compared to 2.4% in the general population [Citation15]. Thus, it is evident that a large proportion of people with ADHD/ASD find it difficult to obtain a sustainable work situation, and that they are strongly overrepresented among those who need adaptations to be able to work [Citation16]. In addition, adults with ADHD/ASD often have various comorbid mental disorders associated with sick leave, such as mood disorders, depression, anxiety disorders and social phobia [Citation1,Citation17,Citation18]. Sleep problems, which significantly reduce the ability to work, are also prevalent in this group [Citation15].

The dynamic interplay between the person, the occupation and the work environment are crucial for a sustainable work situation [Citation19]. Individual intrinsic abilities, such as cognitive, affective, and physical skills, affect occupational performance. Impaired executive functioning is typical in adults with ADHD/ASD, and involves problems with time management, planning, problem-solving, self-activation, and self-motivation [Citation20]. This has major consequences for work-related activities, such as interacting with colleagues, completing tasks on time, or prioritising among tasks. Both conditions are associated with lowered educational attainment [Citation21], work impairments [Citation21,Citation22], and unfavourable long-term outcomes related to employment and health [Citation23]. Many individuals with ADHD/ASD do have an ability to work but are excluded from the labour market due to a lack of understanding and support in the work environment [Citation23,Citation24].

There is a lack of studies addressing the needs of individuals with ADHD/ASD concerning their ability to work sustainably over time [Citation25], especially in individuals with a clinically confirmed ADHD or ASD diagnosis [Citation26]. Few studies fully consider the great individual variability of support needs [Citation27]. Many adults with ADHD/ASD face difficulties in their working life, such as obtaining flexible forms of support and sufficient understanding from employers [Citation8]. They need continuous help, but struggle to get it [Citation28]. Therefore, there is a need for a deeper understanding of individuals’ own experiences in terms of their ability to achieve a sustainable work situation. The approach should not be limited to a specific area of responsibility or a particular workplace, but instead allow a broad perspective that captures the overall situation. There is also a lack of knowledge of how individuals experience their work role and how they are affected by their work, socially and health-wise. Studies that address individual differences are needed to understand better different needs and requirements and how this may be reflected in workplace challenges [Citation29]. Thus, the current study aimed to identify and describe how adults with ADHD and/or ASD experience their ability to work and what conditions affect their ability to work sustainably.

Materials and methods

Study design

This qualitative study used in-depth interviews and reflexive thematic analysis [Citation30,Citation31] to analyse the experiences of adults with ADHD/ASD. Interviews was chosen to capture the participants’ own views and experiences and were conducted by the first author, who has experience with the target group but was not involved in the care of any of the participants.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2019-00668). Participants were informed orally about the study and were assured that they could withdraw from the study without punishment. Informed consent was collected in writing or orally before data collection began. Transcripts and notes were labelled with a code name, and the participants’ identities were known only to the first author.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited through a purposive sampling [Citation32]. Healthcare professionals at five psychiatric outpatient clinics in south-eastern Sweden identified people who fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: be 25–40 years of age and have at least one of the conditions ASD or ADHD, diagnosed according to medical records by specialised psychiatric health care and coded in accordance with ICD-10 [Citation33]. Clinical diagnoses are considered credible in Scandinavia [Citation34] so no new clinical examinations were performed in this study. We did not perform any additional tests or questionnaires to characterise the sample. Exclusion criteria were psychosis, ongoing eating disorders, substance use disorder and intellectual disability. No criteria were applied regarding the participants’ work situation, to maximise the breadth of the study group. The clinics obtained written consent from potential participants (n = 22) to forward their contact details to EH, who then e-mailed them an information letter and booked the interview. One participant did not have time and one did not respond. The remaining twenty () participated in individual in-depth interviews.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the participants.

The mean age of the participants was 32 years. The mean number of years since receiving a neurodevelopmental diagnosis was 5.5 years, ranging from 0.5 to 12 years. Several participants described that their neuropsychiatric evaluation had resulted in a formal diagnosis of ADHD and an acknowledgment of ‘autistic traits’. One participant had been told they had ASD with ADHD traits. Two participants with ADHD were waiting for an ASD evaluation. Six of the participants had different levels of municipal support, such as housing benefits. Some other psychiatric comorbidities, such as bipolar disorder, were reported, and one participant disclosed a previous cerebellar stroke. Four participants had financial compensation from The Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SIA). They took part in the so-called ‘rehabilitation chain’: a gradual return to work, via a 25, 50, and 75% workload, to the maximum percentage possible for the individual. Five participants had no income despite being unable to work, as the SIA had rejected their compensation application.

Data collection

Two pilot interviews resulted in an adjustment of the interview guide, from being four open-ended questions to using a 2 × 2 matrix containing four areas: (1) the person’s view of their own ability to work, (2) their view of their past, present and future work situation, (3) experiences of previously received support to enable a sustainable work situation, and (4) what kind of support they would have wanted to enable a sustainable work situation. This matrix was an intuitive and helpful representation of the interview topics, and we used it as a visual guidance for both the interviewer and the respondent to facilitate focus on the question areas.

Before conducting the interviews, EH recorded her assumptions to become aware of preconceptions and enable a greater degree of mindfulness about potential influences on future interpretations. This included previous experiences with the target group, expectations about common challenges, and systematic differences between diagnosis groups. These considerations and their influence on conclusions were continuously discussed within the research team throughout the project.

The participants chose whether the interview would take place face-to-face (n = 8), by online video call (n = 4), or by telephone (n = 8). Before the COVID-19 outbreak, seven out of 10 chose face-to-face interviews, whereas during the pandemic, nine out of 10 preferred other options. EH conducted all interviews (n = 20) with no one else present. The interviews were 40–100 min long and were conducted between October 2019 and September 2020. It was clarified that the intention was to gather the participants’ subjective experiences. The participants were encouraged to talk openly about their experiences through probes, prompts, and loops [Citation35]. Recruitment ceased when data collection no longer yielded new information [Citation36]. All interviews were audio-recorded. One interview had to be repeated due to recording errors. The recorded audio files and transcripts were archived in the university’s digital secure file system with a password that only the authors had access to.

Data analysis

To identify and describe the participants’ experiences, data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis with an inductive approach [Citation30,Citation31]. The study used a latent, constructionist approach to find out the underlying meaning of the participants’ experiences, which allowed the researchers to move away from the explicit and obvious content of the data [Citation30]. The 15-point checklist by Braun and Clarke [Citation30] was followed during the analysis process, to achieve a dependable thematic analysis. To meet the trustworthiness criteria outlined by Lincoln and Guba [Citation37], a step-by-step approach following the guidelines of Nowell et al. [Citation38] was used. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and in detail. A transcription key was used. Transcripts were checked against the tapes for accuracy by EH and PK. EH kept a detailed codebook throughout the analysis process to maintain a well-documented audit trail of evidence of the coding process [Citation38]. This is a critical aspect of reflexive thematic analysis, where the active role of the researcher must be systematically and continuously documented to achieve dependability and trustworthiness [Citation36,Citation38]. All authors actively read and re-read the transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data. Transcripts were imported into NVivo (version 12) to facilitate the analysis. KI, LK, PK, and EH individually generated initial semantic and latent codes for all the transcripts and then discussed and compared their coding. EH reflected in the codebook on how data were coded, the assumptions made in coding the data and things that might have been overlooked, since coding always bears the researcher’s mark [Citation30]. EH also reflected orally with PK and discussed the coding in relation to her written preconceptions. Each interview was treated with equal attention in the analysis. EH and KI then sorted and collated all the potentially relevant data extracts into themes. In each theme, a central organising concept was identified that captured the essence of a theme to identify the story that each theme told. EH and KI performed researcher triangulation by discussing the potential themes. Notes about the development of subthemes were kept in the codebook to help increase the credibility [Citation38]. EH and KI actively went back and forth between the different phases of the analysis process to check the themes against the original data to ensure the process was inclusive and comprehensive. Themes were then discussed with all authors. Final themes were established that did not overlap and had a clear relationship with each other. EH and KI defined and named themes and strengthened them with quotes. The quotes were translated into English by KI. As a final step, the relevance of the results was confirmed through a member check with one of the participants [Citation37].

Results

Three major themes were identified. The first theme, ‘One’s own cognitive abilities and challenges’, comprised individual qualities and disabilities that imposed limitations on participants’ ability to work. The second theme, ‘Enablement by flexibility and acceptance in the work environment’, described how physical, institutional, cultural, and social factors affected the work situation. The third theme, ‘Accumulated stress makes the work situation unsustainable over time’, emphasised how the passage of time amplified the effects of day-to-day challenges, creating a vicious circle of interacting effects and diminishing the participants’ ability to find a sustainable balance. summarises the themes and subthemes.

Theme 1. One’s own cognitive abilities and challenges

This theme comprised factors related to the individual’s intrinsic abilities. Three subthemes are presented below.

Having the ability to create structure at work

The first subtheme was related to executive function challenges and their effects on the ability to organise work tasks. Participants describe how they struggled to manage their thought processes, making it difficult to plan for and prioritise among tasks. Several participants expressed frustration with their inability to exert executive control at work, leading to overdue tasks and colleagues having to cover up for them. Some participants were able to make lists of priorities and create schedules for themselves, but instead had great difficulty following their own plans.

I have a weekly schedule, so… one remembers bills, vacations, and all those things… the problem is I don’t follow it. (Participant 14)

The cognitive challenges caused stress due to losing track of work tasks, and sometimes led to unpaid overtime work to compensate for poor performance. Participants described a vicious circle of anxiety, sleep problems, and a sense of chaos.

Then I try to figure out what I need to do and what has been done, and create structure and order and fix a bit more and write a bit more, and then it gets too late, and then when I get home I feel sort of ill because I’ve worked too much, so it leads to a vicious circle - that I don’t have the energy to exercise, or that I’m tired and grumpy and cranky/…/I spend more time on work than I should, and too little time for recovery and rest… and then when I am not in control, I don’t feel well… (Participant 3)

Genuine interest in tasks positively affected participants’ performance, and motivation was easier to maintain when the tasks required creative thinking. Several of the participants expressed that their adapted work situation lacked interesting and motivating tasks and that the boring nature of their work reduced their ability to perform.

Understanding one’s own support needs and knowing how to get help

The second subtheme was about the importance of understanding one’s own support needs and being able to learn about the support systems. Several participants explained how gaining insight into their own function had helped them master their work to a greater extent. Some participants expressed frustration that their own insights did not easily translate into finding a good solution. Others described that an increased understanding of their own functioning had helped them become less critical of themselves. One participant described how counselling helped them balance their excessive expectations to perform at work. Having undergone a thorough neuropsychiatric evaluation to get the correct diagnosis and medication improved participants’ understanding of their own function. An ability to imagine the potential existence of yet unknown support measures to discover and explore was a factor that contributed positively, by driving participants to seek support actively. Several participants described specific strategies to ensure that they received the support they needed. These included reading about regulations, obtaining psychiatric healthcare, and discussing their support needs in the workplace with administrators or employers.

I thought a lot about what I take on, and what I communicate to others that I am good at, and what I want to do… To fulfil people’s expectations, they need to expect that I’ll do the right things…not… do a lot of administration, because then they won’t be satisfied, and I won’t be satisfied… (Participant 1)

Hypersensitivity to sounds and other sensory impressions

The third subtheme was about sensory sensitivities at work. Several of the participants described having sensory processing deficits that caused difficulties in work environments, primarily with auditory inputs. One participant expressed that her sound sensitivity varied from day to day in unpredictable ways. Another one explained that multisensory filtering and sorting was a laboursome process, constantly competing with other tasks. Participants described how sensory impressions, such as background conversations or ventilation systems, were difficult to block. Sensory sensitivities were draining and made it difficult for participants to focus, increasing stress and fatigue. One participant, who experienced great sensory stress in meetings, managed the situation by going only to the most important meetings and compensating for the rest of the week by working alone, or at home.

Theme 2. Enablement by flexibility and acceptance in the work environment

The second main theme comprised factors in the external environment that affected the work situation or work-like activities. It comprised three subthemes.

Being seen, understood, and accepted

The first subtheme was about the importance of being accepted in the social work environment. The participants found it very important that people in their work environment were able to understand and accept their ways of functioning. When employers, colleagues and administrators knew of their support needs and capabilities, the work situation became easier to manage. Participants described that they did not always feel seen.

“Do you need to have that on paper, you idiot”, he said… that was his spontaneous comment when I told him I had gotten it on paper… or gotten the diagnosis. (Participant 2)

Being understood was also important when the employer was unable to address challenges or solve problems. One participant explained how nice it had been when her boss understood how difficult it was for her to do night shifts. Even though the employer could not change her situation, she felt she was no longer alone with the struggle. The invisible and fluctuating nature of the impairments made the situation more complicated. The fact that the difficulties were relatively invisible to others, meant that no one could understand the extent of the problems. Several participants were negatively affected by this, because people in their environment were uncertain about their abilities, leading to demands that were set either too high or too low. An eloquent and well-educated participant described how the invisibility of his disability meant that problems kept being questioned by the people who were there to support him:

Either they think I am intellectually disabled, or they don’t think there is anything wrong with me… If they read my medical records… then they think I have difficulties across the whole spectrum with everything, and then they come to me, and then they meet me, and then they wonder who it is that needs help, and it is incredibly frustrating. Several times, I’ve wished so intensely that it was visible that there is something wrong… (Participant 18)

In addition to being understood, the participants wanted to be accepted just as they were, without needing to change. They wanted it to be okay to have different needs than their colleagues. The participants wished for greater openness and more acceptance of differences in society in general. One participant described that it was difficult to find self-acceptance when society clearly did not accept her. Gaining acceptance from others led to a sense of belonging in the workplace, creating a sense of self-worth. In contrast, the consequence of not being accepted was an experience of otherness, and a sense of being an appendage—someone without function.

That tasks and instructions are clearly defined

The second subtheme was about the clarity and structure of work tasks. Clear and well-structured tasks were desired by most of the participants. This could be created with the help of checklists and routines, by getting explicit instructions from employers and colleagues, or with fixed schedules that guided and clarified work tasks. Having deadlines and getting help with prioritising among tasks were requested. Finding a balance between having enough structure and getting self-directed, flexible adaptations was often challenging. Importantly, having access to structure and support did not equate to needing rigid routines or no variability. Rather, participants wanted their employers to help them find individualised and flexible ways to create structure and clarity.

Permission to choose the when, where, and how

The third subtheme was about how participants needed flexibility regarding when, where, and how they carried out their work. This flexibility did not oppose the need for structure described in the second subtheme. Instead, it was about being in a workplace that allowed individuals to find and use their own, creative solutions to increase their capacity and well-being. For participants who had a job, it included flexibility in terms of where the work was done (such as sitting in a quiet area or working from home) and when it was done (such as doing complex tasks during high-energy periods). Such freedoms contributed to a sustainable work situation by allowing participants to manage their energy levels and increase well-being and productivity. Being locked into very strict, rigid work hours was detrimental for several participants. For example, being on time for an early morning shift could require many hours of preparation the day before, coupled with stress and anxiety about being late.

When I had this fixed schedule, I had to rebuild my life around it. Now [with distance studies], I can turn it around… and shape the studies around myself… I am not entirely dependent on having a good day… (Participant 10)

Several participants talked about how norms in the workplace limited flexibility and posed problems. There were assumptions, such as ‘coffee breaks with colleagues are important for your well-being’. One participant described it difficult to create a manageable work situation when everyone was expected to do the same thing, like working physically at the office.

Most important for me is to work from home, given that it costs me so much energy just to transport myself to work and be there physically… open office plans, many people… they want everyone on-site. (Participant 9)

Several of the participants were, or hoped to become, self-employed, to get enough space to manage their work conditions according to their needs. One participant expressed a dream of no longer being pressured to perform at a given place at a given time, and being able to harness the enormous, but unpredictable, boosts of energy that they experienced from time to time.

Participants who did not have a job sometimes expressed their need for flexibility in other ways. These individuals were adversely affected by the lack of flexibility at the societal level, such as rigid rules, inflexible systems, and unchallengeable laws. The rigidity in how they received support to enter the job market forced them to follow processes that had previously failed and were bound to fail repeatedly, without any meaningful adaptations between iterations. All participants who did not have a job described experiences of having failed in work-like situations. Several felt abandoned because they did not fit into the system and the system did not adapt to them.

Theme 3. Accumulated stress makes the work situation unsustainable over time

Despite great variability in participants’ exact circumstances in life and at work, a common denominator was that they lacked stability over time. This was partly due to a general difficulty with managing the various aspects of life, but it was also associated with rigid system-level factors that did not allow much temporal variability. The participants expressed that their needs and abilities varied over time, whereas support systems were static and inflexible. Two subthemes were identified.

Battling with the system over time

The first subtheme was related to long-term, continuous battles with the system, such as fighting for benefits. Participants described problematic system-level factors, such as rules, laws, authorities, and financial and legal barriers affecting income. Several of those who did not have a job described uncertainties in their efforts to enter the job market, with a lack of flow and flexibility in moving through the support systems. There was a sense of great unpredictability about what might happen in the future, and much anxiety from not knowing when things would fall apart again. Many had gone through frequent changes in administrators and other supports or found good workplaces that did not work out long-term. Other discontinuities created stress and insecurity. Interruptions in the continuity of disability benefits were especially stressful. Participants had to reapply regularly for sickness benefits, and spent a great deal of energy on applications, rejections, and appeals. All these factors caused instability and uncertainty, increased stress levels and anxiety, and caused poor health.

Participants perceived that the health insurance system assumed their ability to work was relatively constant, while their own experience was one of rapid and unpredictable fluctuations. To maintain their disability benefits and thus be financially safe, they needed to follow the path prescribed by the system, including the ‘rehabilitation chain’ (see Methods). For several participants, this meant that they had to aim for full-time, even when they had good reasons to believe this was not a good idea. For example, some participants who had worked full-time earlier in life, but got ill from exhaustion, felt an enormous pressure to return to full-time work.

What scares me is that the social insurance agency must try to get me to one hundred percent, and this means that I must wear myself out at seventy-five percent and one hundred percent, to reach a conclusion that I already know. (Participant 16)

To alleviate stress in work-related situations, some suggested it would be good with a support person, who was explicitly meant to stay for the long term. It was important to participants that this support would not be removed during periods of better functioning. Participants wanted general support with life balance over time, a sounding board, and help to reflect on how their functioning interacted with their environment. The participants emphasised that a support person needed to have a high level of competence in neurodevelopmental conditions.

/…/if you find something that works, you have settled into a good routine or so, then very little is needed to disturb it; really, it can be the tiniest stress response and you stop being able to think as well… There are many barriers on the way and therefore you need a bit of continuous follow-up to keep you on track… I very much need a sounding board or discussion partner… so that the thoughts can come unstuck quickly, and come out one at the time… (Participant 15)

Juggling every-day life in a sustainable way

The second subtheme was about the broader issue of juggling aspects of daily life and the effects on the sustainability of the work situation. Our question about how the participants viewed their ability to work was generally answered with descriptions of how it was affected by their whole life situation. It did not appear possible or meaningful for participants to consider their ability to work in isolation from other factors. Whether or not they currently worked, the participants described how they struggled to get their everyday life together. Often, they were forced to implement strict prioritisation among non-work activities, and several of the participants struggled to combine work with their role as a parent or partner. Some described that they were dependent on strict routines at home (e.g. mealtimes or exercise habits) to cope with the work situation and maintain their health and energy. Eliminating stress and avoiding vicious circles of stress was something that the participants had struggled with for many years.

It is like it’s designed to keep me stressed and tired, and then it continues when I pick up the kids, and when I get home, and then I go to bed and feel that I am still stressed, and then I know that there’s a new day and it just keeps going like that… (Participant 4)

Those working successfully still experienced stress and an imminent threat that the situation could change at any time, and they might lose control of the situation. Most had experienced stress-related sick leave and were worried they would need more sick leave in the future. Many described being able to cope with stress periodically – but not continuously over time. It was not that they had poor self-esteem; they were being broken down by always being at the end of their tether. One participant, who currently thought that his work situation was okay, described a great deal of concern about how he would cope if his family situation forced him to switch from night shifts to day shifts.

Living with ADHD/ASD was experienced by many as incredibly stressful. Several described a long-standing struggle both in work situations and outside of work and how it exhausted them in the long term. One participant discussed their ability to work in relation to ageing:

Previously, I could just keep fighting… you can’t keep that up… [living with neuropsychiatric conditions] is incredibly tiring for the body and mind/…/and it’s also something one has to accept, and it’s something I know will get worse… It’s scary… my brain is getting more tired… I’ve tried to fight, like, work one hundred percent… it really wore me out… and I broke again/…/it isn’t fun to age with [neuropsychiatric conditions]/…/my kids have to live with… their dad might kill himself, or break, or lose his temper, so stressful for them. (Participant 17)

Discussion

Our thematic analysis paints a complex picture of barriers to sustainable work for individuals with ADHD/ASD. The first theme emphasised difficulties with person-level characteristics, identifying planning ability, support self-efficacy and sensory function as especially important. The second theme, which described factors in the workplace, focussed on social acceptance, well-defined tasks, and freedom to bend norms around workplace practices flexibly. In the final theme, participants described a critically unmet need for continuity. They described detrimental effects of system-level inertia, frequent changes in interventions, life events, and cumulative effects of stress over time.

The participants’ descriptions of how executive and sensory deficits affected their work are consistent with challenges associated with ADHD/ASD [Citation39,Citation40]. Even when they had tools for planning, they failed to use them consistently, emphasising the importance of continuously monitoring interventions and using them adaptively [Citation12]. The participants found that their performance depended on internal motivation, and that boring or repetitive tasks were challenging [Citation20]. Meaningful activities are essential for motivation [Citation19] and this may be amplified in workers with ADHD who are generally more dependent on external motivation [Citation20]. Hypersensitivity to sounds and lights had a negative impact on the ability to work, consistent with previous research describing the challenges of women with ADHD in filtering and regulating their reactions to stimuli in workplace settings [Citation9]. Consistent with previous studies [Citation40], our participants described how hypersensitivity drained them of energy and caused avoidance behaviours. Raymaker et al. [Citation40] also described reduced tolerance to stimuli due to ‘autistic burnout’, a state of incapacitation caused by cumulative stressors often described by autistic people. Several participants in our study described symptoms similar to those described by Raymaker et al. [Citation40]), including stress and fatigue.

Insight into one’s own internal resources appeared to facilitate the successful navigation of occupational and societal systems. Adults with ASD also described difficulties in understanding complex health care support systems [Citation41,Citation42], emphasising a need for suitably adapted information about services and supports. Participants’ descriptions of finding ways to harness their strengths and get support for their weaknesses endorse the use of strength-based interventions [Citation43] and occupational therapy assessments that map strengths and resources rather than just deficits.

The impact of environmental factors described in Theme 2 is consistent with the known importance of the social environment for health and occupational performance [Citation19]. Environmental factors are crucial as barriers and facilitators in improving employment for adults with ASD [Citation7]. For example, kindness or awareness could make a major difference for adults with ASD in working life [Citation8]. Young adults with ASD and their parents experienced that many barriers to employment had more to do with external factors (e.g. prejudice and organisational inflexibility) than with personal characteristics [Citation8], in line with our results that underlined the need for understanding. Negative attitudes and lack of supportive relationships in the work environment was the greatest obstacle to employment for adults with ASD [Citation44]. In this study, the sometimes-invisible nature of the disability was a barrier to understanding, as it made it difficult for the environment to appreciate the abilities and needs. Similarly, adults with ASD reported that healthcare providers misunderstood them by applying a neurotypical norm, failing to see the individual [Citation42]. Ableism and other types of discrimination in the form of prejudices, cognitive beliefs and stereotypes affect neurodiverse adults through, for example, corporate deficit-based attitudes and a constant pressure to find ways of appearing ‘normal’ [Citation45,Citation46]. Thus, to support adults with ADHD/ASD, support professionals and employers may need to make an extra effort to put aside their expectations and listen to the individual. An affirming social environment may help individuals feel self-worth and belonging, leading to greater well-being and better confidence to engage in occupations [Citation47]. A more accepting environment for individuals with ASD was also suggested to have great benefits to the diversity of workplaces [Citation48].

Our participants struggled with the balance between having enough structure in the workplace and having enough flexibility in when, where and how they performed their tasks. The significant heterogeneity of ADHD/ASD symptoms may make it especially important for this group to get permission to influence their work situation. This study suggests that it is essential not to limit the opportunities for adaptations to whatever adaptations others have received before. Importantly, adaptations are needed to consider day-to-day fluctuations in the mental and physical state. There is widespread agreement that work ability is not static and must be considered within a broader context, as different areas of life affect each other [Citation12,Citation19]. The participants in our study clearly experienced their ability to work as entirely dependent on the environment. According to a recent study employers may be receptive to this, as they specifically requested a greater understanding of how ASD was uniquely expressed in employees or applicants [Citation49]. The flexibility of the participants was also limited by system barriers and bureaucracy, such as the rules governing the SIA, again illustrating the influence of the environment on individual work ability. A similar finding was reported in a Canadian study demonstrating that social security services created employment barriers due to restrictive regulations [Citation50]. The study concluded that the problem was not a lack of services but shortcomings regarding understanding and inclusion in the system. These observations suggest a broader issue, with homogeneous systems that fail to cater to heterogeneous groups, and rule changes are needed in addition to attitude changes.

The participants lacked stability and predictability over time, with severe and long-term consequences on stress levels. The participants needed long-term support tailored and continuously adjusted in intensity, but the provided interventions had generally been short-term, specialised, and disconnected from other problem areas. A lack of continuity in support measures can have many reasons. In Sweden, publicly funded agencies are sometimes understaffed or underfunded, making it more difficult to provide predictable and unbroken support. Further, the social system is designed to provide support when clearly needed and remove it when the individual has gained better function or more independence. These factors do not combine well with the needs of adults with ADHD/ASD, whose ability to function can vary over time. A lack of continuity may also reflect shortcomings in the coordination between different services. Coordinated collaboration across health and social services is beneficial, but integration is difficult to achieve in a system in which services are differentiated by design [Citation51].

The participants described a very high level of stress and exhaustion, and they attributed this to their constant struggle with day-to-day demands. Especially high distress was associated with discontinuities in their financial benefits, which was compounded by a need to re-apply regularly and a relatively high risk of rejection. The accumulating stress had devastating consequences on the ability to work, and cascading effects on the whole life situation. Adults with ADHD/ASD are susceptible to poor mental and physical health [Citation17] and report intense stress and exhaustion from the cumulative effects of daily life [Citation40,Citation52]. While some of the challenges participants describe may be universal for working people, the magnitude is likely amplified for this group.

Our study suggests that a functioning work situation is highly dependent on support measures that are continuous and flexible. The success of a certain set of adaptations at one point does not guarantee sustainability over time. Participants suggested that it would be helpful with a long-term support person, that would be able to provide more extensive support during times of greater need, and vice versa. These results correspond with studies reporting that adults with ADHD benefitted from continuous support from a trusted person in everyday life, to obtain and maintain attachment to the labour market [Citation28,Citation53]. Together with Lyhne et al. [Citation28], our findings emphasise that individual support must address the whole person, suggesting that occupational therapists are vital to adults with ADHD/ASD [Citation28,Citation53]. Together with Lyhne et al. [Citation28], our findings emphasise that individual support must address the whole person, suggesting that occupational therapists are vital to adults with ADHD/ASD. Further research could focus on support measures currently in place for this group or examine more concretely how individualised long-term support could be put in place. We also see the need for multidisciplinary research that engages several stakeholders, such as employment services, social insurance agencies and employers, and occupational therapists and other healthcare providers. Further qualitative research in this area is particularly valuable to address ableism in the workplace as well as in scholarly research. Without first-hand information on subjective experiences of neurodivergent adults, neurotypical employees and scholars risk making deeply uninformed assumptions about support needs, challenges, and abilities.

Limitations

The heterogeneity of difficulties was likely increased by including both ADHD and ASD in the study. However, as these conditions commonly co-occur and are associated with some overlap in symptoms, the breadth and relevance of the data likely benefitted. Most of the participants had been diagnosed in adulthood, suggesting that the participants had not received sufficient support earlier in life. Thus, our participants are not likely to be representative for an entire population of individuals with neurodevelopmental condition, limiting the transferability of results. Recruitment of participants through psychiatry clinics probably excluded people who were not in contact with psychiatric specialist care. While this approach caused some selection bias, it allowed confirmation of ADHD/ASD diagnoses, which is rare in the field [Citation26]. During the data collection phase, the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, prolonging the data collection period and shifting participants’ preference towards telephone or digital interview format instead of meeting face-to-face. This might have affected the participants’ responses and commitment, as it is more challenging to create a relationship and reach a great depth without meeting in person. Nevertheless, digital interviews also had positive effects, as they were more flexible to schedule, and participants did not need to waste energy travelling.

Conclusion

Adults with ADHD/ADHD described individual-level challenges that interacted with opportunities and limitations in the environment, to either support or undermine their efforts to enter and stay in the labour market. The results emphasised the need for individually tailored interventions not limited to the work setting. Crucially, adaptations in the workplace or other enabling circumstances did little to help unless they were also stable and predictable over time. Our findings suggest that stress and exhaustion resulting from a lack of long-term stability was the most significant barrier to sustainable work in adults with ADHD/ASD. We recommend that occupational therapists and other stakeholders should (1) pay special attention to the long-term sustainability of any support measure, and (2) be receptive and flexible in interactions with individuals to accommodate the full spectrum of variability, both between individuals with the same diagnosis, and within individuals over time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants who took part in the study and the staff at the psychiatric clinics for their support with recruitment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–1222.

- Krakowski AD, Lai MC, Crosbie J, et al. Inattention and hyperactive/impulsive component scores do not differentiate between autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a clinical sample. Mol Autism. 2020;11:28.

- Hossain MM, Khan N, Sultana A, et al. Prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders among people with autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112922.

- Hours C, Recasens C, Baleyte C. ASD and ADHD comorbidity: what are we talking about? Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:837424.

- Singh A, Jung Y, Verma N, et al. Overview of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in young children. Health Psychol Res. 2015;3:2115.

- Rong Y, Yang C-J, Jin Y, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2021;83:101759.

- Scott M, Milbourn B, Falkmer M, et al. Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Autism. 2019;23:869–901.

- Anderson C, Butt C, Sarsony C. Young adults on the autism spectrum and early employment-related experiences: aspirations and obstacles. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51:88–105.

- Schreuer N, Dorot R. Experiences of employed women with attention deficit hyperactive disorder: a phenomenological study. Work. 2017;56:429–441.

- Goffer A, Cohen M, Maeir A. Occupational experiences of college students with ADHD: a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2022;29:403–414.

- Law M, Cooper BA, Strong S, et al. The person-environment-occupational model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63:9–23.

- Taylor RR, Kielhofner G. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Blustein DL. The role of work in psychological health and well-being: a conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. Am Psychol. 2008;63:228–240.

- Statistics Sweden. The labour market situation for people with disabilities 2020. Information about education and labour market (IAM); 2021. p. 2.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. Konsekvenser för vuxna med diagnosen ADHD: kartläggning och analys; 2019.

- Boman T. The situation on the swedish labour market for persons with disabilities [Thesis]: Studies from the Swedish Institute for Disability Research No 96. Örebro University; 2019.

- Umeda M, Shimoda H, Miyamoto K, et al. Comorbidity and sociodemographic characteristics of adult autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: epidemiological investigation in the world mental health Japan 2nd survey. Int J Dev Disabil. 2019;67:58–66.

- Bélanger SA, Andrews D, Gray C, et al. ADHD in children and youth: part 1-etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidity. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;23:447–453.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation: 9th Canadian occupational therapy guidelines. 2nd ed. Ottawa (ON): canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2013.

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Impairment in occupational functioning and adult ADHD: the predictive utility of executive function (EF) ratings versus EF tests. Archiv Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;25:157–173.

- Fredriksen M, Dahl AA, Martinsen EW, et al. Childhood and persistent ADHD symptoms associated with educational failure and long-term occupational disability in adult ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2014;6:87–99.

- Kirino E, Imagawa H, Goto T, et al. Sociodemographics, comorbidities, healthcare utilization and work productivity in japanese patients with adult ADHD. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0132233.

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE Jr., Molina BS, et al. Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41:27–41.

- Baldwin S, Costley D, Warren A. Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and asperger’s disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:2440–2449.

- Young S, Adamou M, Asherson P, et al. Recommendations for the transition of patients with ADHD from child to adult healthcare services: a consensus statement from the UK adult ADHD network. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:301.

- Bennett M, Goodall E. Employment of persons with autism: a scoping review. SpringerBriefs in Psychology. Zurich: Springer Nature Switzerland AG; 2021.

- Bury SM, Hedley D, Uljarević M, et al. The autism advantage at work: a critical and systematic review of current evidence. Res Dev Disabil. 2020;105:103750.

- Lyhne CN, Pedersen P, Nielsen CV, et al. Needs for occupational assistance among young adults with ADHD to deal with executive impairments and promote occupational participation – a qualitative study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75:362–369.

- Bury SM, Flower RL, Zulla R, et al. Workplace social challenges experienced by employees on the autism spectrum: an international exploratory study examining employee and supervisor perspectives. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51:1614–1627.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–597.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th ed. Saint Paul (MN): SAGE Publications; 2015.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1992.

- Lampi KM, Sourander A, Gissler M, et al. Brief report: validity of finnish registry-based diagnoses of autism with the ADI-R. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:1425–1428.

- Gillham B. Research interviewing: the range of techniques. Maidenhead (NY): Open University Press; 2005.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications; 2013.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publications; 1985.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13.

- Craig F, Margari F, Legrottaglie AR, et al. A review of executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:191–202.

- Raymaker DM, Teo AR, Steckler NA, et al. “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2:132–143.

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, et al. “Respect the way i need to communicate with you”: healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19:824–831.

- Strömberg M, Liman L, Bang P, et al. Experiences of sensory overload and communication barriers by autistic adults in health care settings. Autism Adulthood. 2022;4:66–75.

- Newark PE, Elsässer M, Stieglitz R-D. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resources in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2016;20:279–290.

- Black MH, Mahdi S, Milbourn B, et al. Perspectives of key stakeholders on employment of autistic adults across the United States, Australia, and Sweden. Autism Res. 2019;12:1648–1662.

- Nario-Redmond MR. Ableism: the causes and consequence of disability prejudice. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley Blackwell; 2020.

- Sullivan J. ‘Pioneers of professional frontiers’: the experiences of autistic students and professional work based learning. Disabil Soc. 2021 [cited 2022 Nov 8]. DOI:10.1080/09687599.2021.1983414

- Rebeiro KL. Enabling occupation: the importance of an affirming environment. Can J Occup Ther. 2001;68:80–89.

- Sarrett J. Interviews, disclosures, and misperceptions: autistic adults’ perspectives on employment related challenges. Disabil Stud Q. 2017;37:2.

- Albright J, Kulok S, Scarpa A. A qualitative analysis of employer perspectives on the hiring and employment of adults with autism spectrum disorder. JVR. 2020;53:167–182.

- FitzGerald E, DiRezze B, Banfield L, et al. A scoping review of the contextual factors impacting employment in neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2021;8:142–151.

- Fisher MP, Elnitsky C. Health and social services integration: a review of concepts and models. Soc Work Public Health. 2012;27:441–468.

- Combs MA, Canu WH, Broman-Fulks JJ, et al. Perceived stress and ADHD symptoms in adults. J Atten Disord. 2015;19:425–434.

- Matérne M, Lundqvist L-O, Strandberg T. Opportunities and barriers for successful return to work after acquired brain injury: a patient perspective. Work. 2017;56:125–134.