Abstract

Background

Community-based day centres (DC) in Sweden provide support to people with severe mental health problems. The role of DC motivation for outcomes in terms of occupational engagement and personal recovery is yet unknown.

Aims

To compare two groups who received DC services, one of which also received the 16-week Balancing Everyday Life (BEL) intervention. The focus was motivation for DC services at baseline and after 16 weeks of services, while also investigating the importance of DC motivation for the selected outcomes and service satisfaction.

Material and Methods

Sixty-five DC attendees were randomised to BEL (n = 27) or standard support (n = 38) and responded to questionnaires about motivation, the selected outcomes and satisfaction with DC services.

Results

The groups did not differ on any measured aspects of motivation; nor were changes seen over time. The BEL group, but not those receiving standard support, improved from baseline to 16 weeks on occupational engagement and recovery. Motivation for attending the DC was related to service satisfaction.

Conclusion

The BEL program could be a viable enrichment tool in the DC context and boost occupational engagement and personal recovery among the attendees.

Significance

The study provided knowledge of importance when developing community-based services while enhancing motivation.

Introduction

Within community-based psychiatric care in Sweden, day centres (DC) offer services to support people living with long-term mental health problems who experience difficulty in working or engaging in life activities [Citation1,Citation2]. DC services can include group-based or individual meetings with professionals such as occupational therapists, social workers, or mental health aides. Examples of group-based activities include art and crafts, cooking, gardening, as well as work-oriented activities such as running a café or creating goods to sell. DC in Sweden are often organised differently in different municipalities and can offer different services [Citation1,Citation3], but have in common that they hold the main responsibility for psychosocial support to people with severe and enduring mental illness [Citation4]. Similar services play an important role for this target group in several countries worldwide [Citation5–10].

Although limited research has been done on the experiences, outcomes, and motivating factors of those attending community-based DC for people with mental health problems, it is possible to discern categories of research, namely (i) cross-sectional descriptive studies, research (ii) comparing subgroups and (iii) changes over time, and (iv) intervention research. Descriptive studies show that members attend DC to socialise, obtain a better daily structure, and participate in, e.g. arts and music groups [Citation11,Citation12]. DC were valued for providing support, preventing relapse and promoting independence, but attendees desired a more active role in developing the opportunities available in the DC [Citation6,Citation13]. In these studies, concerns were also raised that the DC services fostered dependence and sometimes prevented participation in wanted group sessions. Tjörnstrand and colleagues gave a more optimistic picture of DC services, detailing various activities DC may offer, as well as how different types of activities in combination with various levels of demands can create a rehabilitation chain with many options for attendees [Citation1,Citation2]. Still, comparative research on people with mental illness has shown that those who attended DC were comparable to those who had no regular daily activities on quality of life, satisfaction with everyday activities and other well-being variables [Citation14]. That DC attendance did not make a difference in these respects was later corroborated by Argentzell and colleagues [Citation15–17]. Research addressing change over time among DC attendees has identified stability over a nine-month follow-up time regarding multiple outcomes, such as occupational engagement, occupational satisfaction, perceived social engagement and social functioning [Citation18]. These authors argued that stability over time might be a good outcome among people with severe and enduring mental health problems. A study using a time-series design found that after re-organizational changes intended to increase DC attendees’ freedom of choice were implemented, satisfaction with services and a sense of empowerment actually decreased [Citation19]. Other outcomes, such as social network size and occupational engagement, remained stable. Intervention research in the DC context was motivated by researchers noting the lack of indicators of development towards a more active and satisfying everyday life [Citation18]. This informed a staff- and program-focused intervention designed specifically to enrich DC with more meaningful occupations. That intervention was not found effective, however, in supporting the attendees’ satisfaction with everyday occupations, perceived meaningfulness among DC occupations, or quality of life compared to DC settings providing support as usual [Citation20]. Additionally, attendees’ empowerment was not found to improve [Citation21]. Qualitative studies showed that those who attended the DC were satisfied with the intervention [Citation22] and staff experienced that the attendees developed their occupational repertoire and became more integrated into the society [Citation23]. Nevertheless, existing research on DC indicates that further enrichment of the services offered seems warranted.

Focussing on motivational aspects could be a fruitful avenue for gaining additional knowledge about the potentials inherent in DC, since the motivation for participating in an intervention or rehabilitation method has been found essential for outcomes in other interventions for people with mental illness. Examples include a lifestyle intervention based on exercise and diet [Citation24], computerised activity training [Citation25], and vocational rehabilitation [Citation26,Citation27]. Focussing on motivation itself has also been proposed in cognitive rehabilitation [Citation28]. Regarding the DC context, studies have found that motivation to attend the DC was generally in the upper range among the attendees on a VAS scale from 0 to 100, while preferring to spend time alone was in the lower range [Citation3,Citation12]. Motivation to attend DC has further been found to be related to greater engagement in everyday activities [Citation3] and greater satisfaction with the DC [Citation29]. Taking into account the research mentioned above, it seems warranted to focus further on the role of motivation, including if the motivation to engage in DC is affected by an intervention. This was an incentive for the current study, performed in the context of a larger intervention project named Balancing Everyday Life (BEL).

The occupational therapy intervention BEL was developed in Sweden to offer an activity- and recovery-based lifestyle program in both the DC and in specialised psychiatric clinic contexts. A randomised controlled trial (RCT) indicated positive outcomes including increased occupational engagement, occupational balance and activity level [Citation30]. BEL is a 16-19-week group-based program and concentrates on themes of relevance for everyday life balance of occupations, self-care, and personal recovery among people with mental health problems. One of the more prominent themes in the program also concerns finding motivation for engaging in different forms of meaningful daily occupations. DC services are still an essential part of the support offered to people with severe mental health problems in Sweden, while at the same time the research into the DC context is scarce and has yielded ambiguous results. It thus seems important to look specifically into DC attendees who have participated in the BEL program. Illuminating the role of DC attendees’ motivation for possible gains in outcomes such as activity-related factors and personal recovery could yield knowledge that would be important when developing and enriching DC services at a time when Swedish mental health care is setting personal recovery and peer support in focus. These were the rationales for the current study, the aim of which was to compare the group of DC attendees who received the BEL intervention with the DC group who received standard support only, regarding their motivation for engaging in the DC services at baseline and completion of the intervention, while also investigating the importance of DC motivation for outcomes in terms of occupational engagement, personal recovery and satisfaction with the services received in the DC.

The study proceeded with the following research questions:

How did the attendees who received the BEL intervention in addition to standard community-based DC support and the group who received only standard support rate their motivation for engaging in the DC services at baseline and completion of the intervention?

Which changes, if any, did the attendees make from baseline to completed intervention regarding outcomes in terms of occupational engagement and personal recovery? Were there any differences in these respects between those who received the enriched support and those who received only standard support?

How was motivation to attend DC related to the change in the selected outcomes and to satisfaction with the services received?

Methods

The current study, focussing specifically on the DC context, was incorporated into the ethical review of the BEL project as a whole [Citation30]. Approval was provided by the Ethical Review Board in Lund (Reg. No. 2012/70). The project followed all pertinent ethical standards, including the Helsinki declaration [Citation31] and the Swedish act concerning the ethical review of research involving humans [Citation32]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Recruitment of settings and participants

The DC study was organised as an RCT, just as in the larger BEL project. The power analysis was based on detecting differences in the instrument Satisfaction with Daily Occupations (SDO) [Citation33]. Based on the means and standard deviations from a previous study [Citation14] we arrived at 41 participants in each condition as the desired sample size to detect a difference in the SDO of 0.5 with 80% power at p < 0.05. SDO was used in the larger RCT but not for the current part.

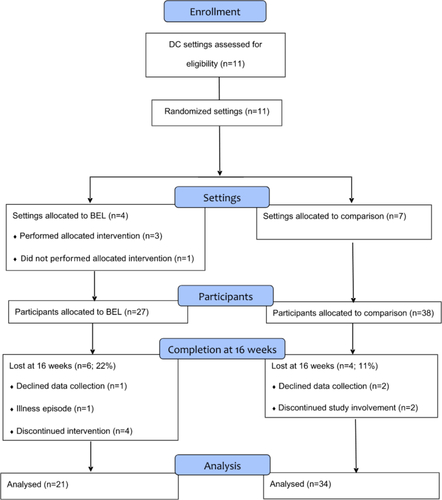

Consent for participation was first obtained at the setting level, followed by cluster randomisation to BEL or standard support. Thereafter, individual DC attendees were invited via a gatekeeper who was employed at the DC and knew the attendees [Citation34]. Please see for a schematic view of the enrolment of settings and participants. The fact that fewer DC settings were randomised to the BEL intervention has to do with the larger project [Citation30], where the same number of settings (14 + 14) were randomised to the respective interventions but the proportion of DC and specialised psychiatric settings differed within each of the two arms. Additionally, one of the DC settings randomised to BEL never performed the allocated intervention. As seen in , we were not able to reach the desired sample size and the DC part of the RCT became underpowered.

Participants

Eligible for inclusion were users of DC, aged 18 – 65 years, and with sufficient command of Swedish to follow the BEL program and respond to questionnaires. In Sweden, those who visit DC have a psychiatric disability, defined as difficult to manage everyday life due to mental health problems lasting for two years or more. Exclusion criteria were comorbidity of dementia or intellectual disability and acute illness episodes. DC attendees who accepted the intervention were provided with verbal and written information about the project, including their rights to withdraw their approval at any time without explanation. They subsequently signed their written informed consent. Characteristics of the participants are displayed in . As seen there, the only statistically significant difference between the BEL group and the comparison group receiving only standard support concerned diagnosis, a neuropsychiatric disorder being more common in the BEL group and psychosis more common in the comparison group. There were also tendencies, however not statistically significant, that females were more common in the BEL group, as well as having children.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Ns. (p = 0.121)

The interventions

All DC settings participating in the project were staffed with at least one occupational therapist. Both groups received standard support from the DC, but the intervention group received the BEL program in addition to standard support. To some extent, however, and for logistical reasons, this meant that some of the standard support was replaced by BEL sessions. Per a self-report questionnaire, the BEL group spent 11.6 (SD = 10.6) hours per week in the DC and the group receiving standard DC support 9.3 (SD = 7.2); this was not a statistically significant difference (p = 0.610). This meant that the groups were comparable in staffing and time spent in the DC.

The BEL intervention

BEL is structured as a 14-session course to be administered as a group program and implemented in outpatient or community-based mental health settings. The 14 sessions are distributed over 16–19 weeks, and the current study was based on the 16-week alternative. During the first 12 weeks of the course, the group meets for one session per week, during which they concentrate on themes of relevance for everyday life and personal recovery, such as occupational balance, exploring one’s motivation, recognising productive and leisure activities, building social capital and experiencing informal peer support. The course concludes with two biweekly booster sessions without any fixed themes. The sessions consist of brief educational sections, exercises and discussions. Identifying and testing desired everyday activities is a prominent feature throughout the course. Goals and strategies for engaging in certain activities are developed, based on each person’s preferences and choices. Between sessions, the preferred activities or routines are tested in a naturalistic context, as a type of self-assigned homework. At the next group session, individuals share how they feel it went and depending on the outcome, goals can be re-negotiated. Informal peer support is encouraged during the course, particularly during the booster sessions. The ambition is that BEL participants will have gained the ability for self-analysis in relation to everyday activities after completing BEL course, as well as have the possibility for an enhanced social network. This includes reflecting on one’s own situation, having found strategies for changing one’s everyday life in a wanted direction and thereby feeling a balance between activities pertaining to rest and work, secluded and social activities, etc., and having found a sense of satisfaction and meaning in everyday life. The BEL course is led by one or two therapists who use a structured manual [Citation35], and at least one of them must have taken part in a 2–3 day’s BEL training program. In this article, BEL will be referred to interchangeably as an intervention and a course.

Standard DC support

In Sweden, attending a DC means having access to a variety of activities, usually for 2–3 days per week. Admittance to a DC normally requires a needs assessment and a service decision from a social service official. People receiving DC support have the opportunity to engage in work-oriented activities involving high degrees of responsibility and autonomy, such as crafting goods to be sold (e.g. ceramics and wood and sewing products) or providing services to the surrounding community (e.g. food catering and car wash) [Citation1]. There are also opportunities for more social activities, with fewer demands on responsibility and independence. By using the variation in activities in combination with higher and lower levels of autonomy, the DC services have the potential to offer a form of individualised support [Citation2]. However, most activities are decided beforehand, and although they make a supply to choose from there is limited opportunity to build on attendees’ individual preferences. Standard DC support as delivered in the current study aligns with these characteristics.

Data collection

Data were collected by research assistants who were qualified as occupational therapists or psychologists and had substantial experience working with persons with mental health problems. The data collection was based on self-report questionnaires, as detailed below, and the research assistants helped out when needed, without influencing participant responses.

Background questionnaire

A background questionnaire was developed for the RCT as a whole, comprising sociodemographics and self-reports regarding DC attendance. There were also questions regarding psychological and physical problems and psychiatric diagnosis. Based on this latter information, and for use in our research, a specialist doctor in psychiatry assigned diagnoses according to ICD-10 [Citation36].

Motivation

Motivation to engage in community-based services was measured by four items developed for the DC context [Citation12]. The items target general motivation for attending the DC, setting clear goals for what to do there, preferring to spend one’s time on one’s own, and preferring a paid job to go to. The response format is a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0–100. The items are seen as different facets of DC motivation and do not form a scale. Face and content validity were ensured in two expert panels, one consisting of mental health users and one of researchers in the mental health field [Citation12].

Occupational engagement

Profiles of Occupational Engagement in people with Severe mental illness (POES) were used to assess occupational engagement [Citation37,Citation38]. It has two parts where respondents first register the previous day’s activities on a diary sheet with four columns. One is for the activities the person engaged in, and the others are for whom they were with (if not alone), where they were, and how they felt when performing the activity. In the second part, respondents reflect on their diary report and rate their occupational engagement according to eight questions, addressing, e.g. whether the person has variation among the activities, has good routines, and spends time with others. The response format is a five-point scale ranging from “does not apply at all” (=1) and to “totally applies” (=5). The POES instrument has been found to have good internal content validity and inter-rater agreement and to be a unidimensional scale that represents a continuum of occupational engagement [Citation37,Citation38]. A self-report version was used for the current study. Although no psychometric study has as yet been performed on the self-report version, the internal consistency has been found to be good at α = 0.85 [Citation30].

Personal recovery

The Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery (QPR) was used to gain a measurement of personal recovery. The original version was a 22-item questionnaire found to have good internal consistency and reliability, and high construct validity [Citation39]. Two factors were identified: intrapersonal - regarding feelings of worth, purpose, and empowerment; and interpersonal – regarding connection and interaction with others [Citation39]. A shorter one-factor version of the QPR with 15 items was found to have better psychometric properties [Citation40]. The current study used the QPR-Swe, a Swedish version of the questionnaire where 16 items of the original 22 were identified as worthy of inclusion and produced a one-factor scale with excellent homogeneity and adequate construct validity [Citation41].

Satisfaction with the DC services

The DC satisfaction scale was inspired by research by Larsen and colleagues [Citation42] but was amended to fit the DC context. By eight items, the DC satisfaction scale addresses, e.g. the quality of the support, the attendee’s satisfaction with the support, and whether they would recommend it to other mental health care users.

Data analyses

Conventional non-parametric statistics were used; the Mann–Whitney test to analyse differences between independent samples, Wilcoxon’s test for related samples, and Spearman correlations for associations between variables. As a way of analysing change in DC motivation, we applied a method based on standard deviations (SD) [Citation43]. The span for change in motivation was set at one standard deviation in either direction from the mean for the respective motivation variable. Jacobson and Traux [Citation43] preferred two SD, but also stated that one SD could be enough to detect a meaningful change among severely ill groups, for example, persons with psychosis. We thus used the baseline SD for each of the motivation variables to form groups of change. Those who at 16 weeks had a score smaller than the baseline value minus the SD formed a decreased group; those with scores within one SD in either direction formed an unchanged group; and those who had a score larger than the baseline value plus one SD formed an increased group. These groups were used for descriptive purposes and to further explore change in DC motivation. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test was used for the latter purpose. Since the study was underpowered, we found it justified to perform some of the analyses on the two groups together, as further specified below in the result section. The software used for computations was the IBM SPSS version 28 [Citation44].

Results

Motivation for day centre participation

shows the motivation scores for the intervention group that received the enriched support and the comparison group that only attended a DC. All four motivation scores remained relatively stable (no statistically significant change) between baseline and 16 weeks of intervention for both groups. Motivation for going to the day centre was rated above the 75th percentile of the VAS scale for both groups. Setting clear goals and preferring work was in the mid-span of the possible VAS scale range, and preferring to be alone was in the lower span for both groups.

Table 2. Descriptives for the two groups concerning motivation at baseline and after 16 weeks (BEL completion).

Change in motivation

Since no group differences were found regarding any aspect of DC motivation, the analysis of a meaningful change in DC motivation was based on the two groups together. displays how motivation for DC attendance changed from baseline to the 16-week measurement. It is obvious that most participants did not alter their position, based on a change of one SD in either direction. Movements into increased and decreased motivation levelled out each other, except for motivation for setting goals where more participants decreased than increased their motivation with one SD. The Jonckheere-Terpstra test showed a statistically significant linear trend (p = 0.012), indicating that those who had decreased their motivation for setting goals had rated their motivation high at baseline, whereas those who had increased their motivation had rated their initial motivation low. No corresponding linear trend was found for the other motivation aspects.

Table 3. Number of participants with increased, unchanged and decreased motivation from baseline to completed intervention, both groups analysed together.

Exploring change in outcomes between baseline and follow-ups

Further group comparisons regarding scores for the outcomes at baseline and follow-up at 16 weeks are shown in . The DC attendees who received the 16-week BEL intervention had improved their occupational engagement and their personal recovery at completion, whereas the group without additional intervention did not. All of these ratings were in the mid-span of the possible range, whereas the rating of satisfaction with the services in the DC, where no change occurred, was at the upper end.

Table 4. Descriptives for the two groups concerning outcomes at baseline and after 16 weeks (BEL completion).

Calculations of differences between the groups in change scores, not displayed in , showed that there were few significant differences between the groups. The only significant difference at 16 weeks was in occupational engagement, where the group who had received enriched support in terms of BEL had improved more (p = 0.004). There were no differences in change scores for personal recovery (p = 0.282). Nor was there a difference in satisfaction with the services received (p = 0.973).

Motivation for day centre participation in relation to changes in the selected outcomes

Since the groups differed on change only in occupational engagement among the outcomes, and in none of the motivation variables, and to increase the statistical power in further calculations, the analyses concerning associations between motivation and the selected outcomes – occupational engagement, personal recovery, and satisfaction with the services – were performed on the two groups together.

The only statistically significant association between the motivation variables at baseline and the outcome measures at 16 weeks was a positive correlation between motivation to attend the day centre and satisfaction with the services received in the DC (rs=0.29, p = 0.034). The motivation variables at baseline were thus not associated with occupational engagement or personal recovery at that time.

When exploring correlations between motivation at 16 weeks and the corresponding outcome scores, few correlations were found. Similar to the situation at baseline, motivation to attend the day centre was positively correlated with satisfaction with the services received (rs=0.34, p = 0.014). In addition, a positive correlation was found between preferring spending time on one’s own and personal recovery scores (rs=0.37, p = 0.007).

Discussion

Occupational engagement and personal recovery improved over the 16 weeks of intervention in the enriched group, but not in the comparison group. Regarding occupational engagement, the change score was also greater in the BEL group than in the comparison group. This is interesting, since previous studies exploring change in activity and recovery variables among DC attendees have found no changes, and rather stability [Citation3,Citation20]. The result regarding the comparison group thus confirms previous research, whereas the positive findings for the enriched group indicate that the BEL intervention brought something new and beneficial to the DC services, something the previous effort to enrich DC services failed to do [Citation20]. That BEL brings a novel approach to mental health services is in line with a qualitative study including BEL participants in both DC and clinic settings. The findings showed that BEL participants felt more engaged in personal goal setting and they described becoming more engaged in life activities such as volunteering, work, creative activities, and social activities. Some found more motivation to participate in other programs offered by their care centre, and others felt motivated to participate in activities outside of the care centre [Citation45]. It is possible that taking part in BEL brought some of the personalisation, in terms of making own choices and goals, recommended to enrich DC services [Citation13,Citation20,Citation46].

The motivation variables remained stable from baseline to completed intervention for both groups. Motivation for being at the day centre was generally high, preferring to be alone was low, and goal setting and preferring work were mid-range. This is similar to previous research on DC motivation [Citation12] and indicates that the current sample was comparable to other DC attendees in Sweden. Motivation for going to the day centre remained high. This is an important finding per se and confirms previous research highlighting the supportive role both attendees and staff assign to DC and similar settings [Citation6]. Setting clear goals and preferring work remained in the mid-span of the possible range, and both groups scored in the lower range for preferring spending time on one’s own. After the completed intervention, a positive relationship was found between motivation for spending time on one’s own and personal recovery. This indicates that wanting to spend time alone did not signify withdrawal from DC services in a negative sense, but rather perhaps a desire to develop on one’s own.

The mapping of how participants moved between change categories (cf. ) confirms the picture of stability but reveals some nuances. What could seem surprising is that regarding setting goals, more persons were found in the decreased category than in the increased. This finding was linked with the baseline scores, however, a classic example of regression towards the mean [Citation47] where those scoring higher from start had a tendency to decrease their ratings upon the second measurement, and the opposite was true for those who initially scored lower.

Methodological considerations

The fact that this study was underpowered is a drawback. There is a likelihood of Type-2 errors [Citation47], i.e. that true differences and relationships have gone undetected. This undermines the internal validity of the study, and future replication with a larger sample is warranted to further investigate the role of DC-related motivation for outcomes of the DC services. Future research should also address additional facets of motivation, such as motivation for participating in a specific intervention (such as BEL) and general motivational disposition. It is possible that such aspects play more important roles in relation to outcomes. The external validity of the study seems fair; in addition to aligning with previously described DC attendees on motivation [Citation12], the current sample does not deviate on known characteristics from those participating in other DC studies [Citation19,Citation20], nor did the selected DC units. Another aspect to consider is the use of self-report assessments with people with mental health problems, but this may be justified for various reasons. One is that the voices of people themselves with mental health problems must be heard, another is that research indicates that self-reports provide reliable data, also for those with severe psychiatric problems [Citation48].

Conclusion

On a group basis, DC motivation showed to be a stable variable over a 16-week period of intervention. It also seemed mainly unrelated to the change in the selected outcomes. The intervention group who had received enriched support from the BEL program improved on occupational engagement and personal recovery, whereas the comparison group did not, despite being similar in having an occupational therapist among the staff and in hours spent in the DC. This suggests that the BEL program could be a viable tool to enrich DC services and boost occupational engagement and personal recovery among the attendees.

Author contribution

All authors made substantial contributions to the study. ME was PI for the project and EA was instrumental in developing the BEL intervention and coordinating the project. KL and EA collected parts of the data. ME and KL analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Ethical statement

The project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Reg. No. Reg. No. 2012/70. The consent to participate form that was approved and used followed the recommendation from Lund University. All pertinent ethical guidelines were followed, including the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983 and 2004.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study participants for their time and efforts, and the research assistants for collecting data.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Trial registration

The study was registered with ClinicalTrial.gov. Reg. No. NCT02619318. Retrospectively registered: 02/12/2015.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tjörnstrand C, Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Participation in day centres for people with psychiatric disabilities: characteristics of occupations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2011;18:243–253.

- Tjörnstrand C, Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Participation in day centres for people with psychiatric disabilities – a focus on occupational engagement. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;73:144–150.

- Hultqvist J, Markström U, Tjörnstrand C, et al. Programme characteristics and everyday occupations in day centres and clubhouses in Sweden. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:197–207.

- Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer för psykosociala insatser vid schizofreni och schizofreniliknande tillstånd. Stöd för styrning och ledning [national guidelines for psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia and related disorders. Support for management and leadership]. Stockholm (Sweden): Socialstyrelsen; 2018.

- Kilian R, Lindenbach I, Lobig U, et al. Self-perceived social integration and the use of day centers of persons with severe and persistent schizophrenia living in the community: a qualitative analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:545–552.

- Bryant W, Craik C, McKay EA. Perspectives of day and accommodation services for people with enduring mental illness. J Ment Health. 2005;14:109–120.

- Catty J, Burns T, Comas A, et al. Day centers for severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD001710.

- Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al. Rehabilitative day treatment vs. supported employment: i. Vocational outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 1994;30:519–532.

- Rebeiro K, Day D, Semeniuk B, et al. Northern initiative for social action: an occupation-based mental health program. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55:493–500.

- Crosse C. A meaningful day: integrating psychosocial rehabilitation into community treatment of schizophrenia. Med J Aust. 2003;178:S76–S8.

- Catty J, Burns T. Mental health day centres. Their clients and roles. Psychiatrist. 2001;25:61–66.

- Eklund M, Tjörnstrand C. Psychiatric rehabilitation in community-based day centres: motivation and satisfaction. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:438–445.

- Bryant W, Craik C, McKay EA. Living in a glasshouse: exploring occupational alienation. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71:282–289.

- Eklund M, Hansson L, Ahlqvist C. The importance of work as compared to other forms of daily occupations for wellbeing and functioning among persons with long-term mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:465–477.

- Argentzell E, Leufstadius C, Eklund M. Factors influencing subjective perceptions of everyday occupations: comparing day centre attendees with non-attendees. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:68–77.

- Argentzell E, Leufstadius C, Eklund M. Social interaction among people with psychiatric disabilities–does attending a day centre matter? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60:519–527.

- Argentzell E, Tjörnstrand C, Eklund M. Quality of life among people with psychiatric disabilities – does day centre attendance make a difference? Community Ment Health J. 2017;53:984–990.

- Hultqvist J, Markström U, Tjörnstrand C, et al. Social networks and social interaction among people with psychiatric disabilities – comparison of users of day centres and clubhouses. Glob J Health Sci. 2017;9:107–120.

- Eklund M, Markström U. Outcomes of a freedom of choice reform in community mental health day center services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:664–671.

- Eklund M, Gunnarsson AB, Sandlund M, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to improve day Centre services for people with psychiatric disabilities. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014;61(4):268–275.

- Sutton D, Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Empowerment, self and engagement in day center occupations: a longitudinal study among people with long-term mental illness. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26:69–78.

- Leufstadius C. Experiences of meaning of occupation at day centers among people with psychiatric disabilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25:180–189.

- Eklund M, Leufstadius C. Adding quality to day Centre activities for people with psychiatric disabilities: staff perceptions of an intervention. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23:13–22.

- Korman N, Fox H, Skinner T, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a student-led lifestyle (diet and exercise) intervention within a residential rehabilitation setting for people with severe mental illness, GO HEART (Group Occupation Health, Exercise And Rehabilitation Treatment). Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:319.

- Gyllensten AL, Forsberg KA. Computerized physical activity training for persons with severe mental illness – experiences from a communal supported housing project. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;12:780–788.

- Mervis JE, Fiszdon JM, Lysaker PH, et al. Effects of the Indianapolis vocational intervention program (IVIP) on defeatist beliefs, work motivation, and work outcomes in serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2017;182:129–134.

- Poulsen C, Christensen T, Madsen T, et al. Trajectories of vocational recovery among persons with severe mental illness participating in a randomized three-group superiority trial of individual placement and support (IPS) in Denmark. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;32:260–271.

- Velligan DI, Kern RS, Gold JM. Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia and the putative role of motivation and expectancies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:474–485.

- Eklund M, Sandlund M. Predictors of valued everyday occupations, empowerment and satisfaction in day centres: implications for services for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28:582–590.

- Eklund M, Tjörnstrand C, Sandlund M, et al. Effectiveness of balancing everyday life (BEL) versus standard occupational therapy for activity engagement and functioning among people with mental illness – a cluster RCT study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:363.

- Medical Association W. Declaration of Helsinki. 1964/2008.

- Lag (2003:460) om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor [Act (2003:460) concerning the Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans], 2003.

- Eklund M, Bäckström M, Eakman A. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the 13-item satisfaction with daily occupations scale when used with people with mental health problems. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:7.

- Swedish Government Official Reports. Vad är psykiskt funktionshinder? [what is a psychiatric disability? Sweden (Stockholm): National Board of Health and Welfare; 2006.

- Argentzell E, Eklund M. Vardag i balans™. en aktivitetsbaserad och återhämtningsinriktad gruppintervention för personer med psykisk ohälsa [balancing everyday life™. An activity-based and recovery-oriented group intervention for people with mental illness]. Nacka (Sweden): Sveriges arbetsterapeuter (Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists); 2021.

- WHO. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Bejerholm U, Hansson L, Eklund M. Profiles of occupational engagement among people with schizophrenia: instrument development, content validity, inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency. Br J Occup Ther. 2006;69:58–68.

- Bejerholm U, Lundgren-Nilsson A. Rasch analysis of the profiles of occupational engagement in people with severe mental illness (POES) instrument. Health Qual Life Outc. 2015;13:130.

- Neil ST, Kilbride M, Pitt L, et al. The questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR): a measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis. 2009;1:145–155.

- Williams J, Leamy M, Pesola F, et al. M. Psychometric evaluation of the questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR). Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207:551–555.

- Argentzell E, Hultqvist J, Neil S, et al. Measuring personal recovery - psychometric properties of the swedish questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR-Swe). Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71:529–535.

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2:197–207.

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–19.

- IBM SPSS Statistics 28 core system user’s guide. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp.; 2021 [INTERNET]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_28.0.0/pdf/IBM_SPSS_Statistics_Core_System_User_Guide.pdf.

- Lund K, Hultqvist J, Bejerholm U, et al. Group leader and participant perceptions of balancing everyday life, a group-based lifestyle intervention for mental health service users. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27:462–473.

- Jansson JA, Johansson H, Eklund M. The psychosocial atmosphere in community-based activity centers for people with psychiatric disabilities: visitor and staff perceptions. Community Ment Health J. 2013;49:748–755.

- Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993.

- Bell M, Fiszdon J, Richardson R, et al. Are self-reports valid for schizophrenia patients with poor insight? Relationship of unawareness of illness to psychological self-report instruments. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151(1-2):37–46.