Abstract

Background

Successful ageing-in-place is dependent on the design and features of the home. In some cases, home modifications or relocation may be required. Accessible, affordable, age-friendly housing for older adults is required to encourage forward planning.

Aims/objectives

To understand the views of middle and older aged adults and individuals with older relatives, about home safety, ageing in place and housing accessibility.

Material and methods

A qualitative descriptive approach, using reflexive thematic analysis was used. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with 16 participants, comprising eight middle- older aged people and eight individuals with older relatives.

Results

Seven themes were identified. Most participants accepted the ageing process and could recognise home environment hazards and potential future housing needs. Others were determined to remain independent at home and resistant to making future changes until necessary. Participants were interested in obtaining more information about how to improve home safety or services to support ageing-in-place.

Conclusion

Most older adults are open to conversations about planning for ageing-in-place and would like further information on home safety and home modifications. Educational forums and tools (such as flyers or checklists) which assist older people to plan future housing needs are recommended.

Significance

Many older people are living in homes that present hazards and limited accessibility as they age. Earlier planning could lead to home modifications which will improve the capacity to age in place. Action to provide earlier education is needed as the population ages and suitable housing for older people is limited.

Decision-making around home safety among the ageing population can be compromised by lack of awareness, inadequate access to information and the sudden onset of age-related changes.

An education guide or tool to support forward planning and housing decisions may improve early awareness among the ageing population.

Key points for occupational therapy

Keywords:

Introduction

Globally, the proportion of older adults aged 65 and over is projected to increase steadily over the coming decades resulting in a population of 2.1 billion older adults across the world by 2050 [Citation1]. Ageing leads to biological, physical and cognitive changes and increased risk of disease [Citation1]. As age increases, the person’s ability to move within and function independently within their own home environment can become increasingly difficult [Citation2]. Most people want to age at home and remain in their own homes for as long as possible [Citation3–6] which is often referred to as ‘ageing in place’ [Citation7]. Pani-Herreman et al. [Citation7] define ‘ageing in place’ where the house is more than just a place, but a home connected to social networks, identity and supportive technology. Research conducted with older people reveals that they prefer to stay at home for several reasons including a sense of attachment to the home, the high costs of moving, and a desire to maintain existing social and community networks [Citation3–6]. Home is considered by older adults to be a place of comfort and safety where independence can be preserved [Citation3,Citation4,Citation8,Citation9]. Strong community networks enable older adults to cope with age-related changes and prevent isolation [Citation10–12]. Similarly, being surrounded by important possessions or memories is reported to be linked to the quality of life [Citation9].

The ability to ‘age in place’ is dependent not only on age-related changes but on the design and environment of the home and the availability of other housing options [Citation13]. Few homes are designed or built with consideration of the needs of older people and the development of age-friendly housing has remained a relatively low priority worldwide [Citation14,Citation15]. According to Severinsen et al. [Citation16] many older people are living in houses which are unsuitable. As a marker of housing suitability, Australian data shows that approximately three-quarters (75%) of older people lived in a house with two or more spare bedrooms [Citation17].

As a person ages, home modifications or relocation may be required [Citation18]. Relocation may be avoided if the home can be modified to meet the needs of the older person. Occupational therapists often conduct home assessments to identify environmental hazards and suggest possible modifications to improve the safety of the home (e.g. installation of ramps, grabrails or decluttering of bedrooms) [Citation19]. Evidence from randomised controlled trials suggests occupational therapy home assessments can lead to improved functional performance, reduced risk of falls and lower demands on caregivers [Citation19]. However, access to occupational therapy home assessments may be limited in both urban and rural areas and is usually available only after injury or illness [Citation13,Citation20,Citation21]. Home assessments can take considerable time with one study suggesting an average duration of 80 min per home assessment [Citation22].

Solutions which lead to accessible, age-friendly homes for the increasing number of older adults are required. It is possible that, in future, digital health tools may play a role in enhancing the home assessment process [Citation13]. A scoping review by Ninnis et al. [Citation13] identified 14 studies which used technology to enhance the occupational therapy home assessment process. These studies involved either the development of specialised tools or the application of off-the-shelf technologies. Findings from studies conducted to date suggest that remote assessments were less likely to identify potential hazards than assessments when the therapist was in the home [Citation13, Citation23]. Despite the rapid advances in technology clinical practice have not changed substantially and traditional in-home assessments remain preferable [Citation13].

Much of the research in this field to date has focussed on older adults with existing diseases and disabilities who require home modifications. Less research has been conducted with older adults who remain relatively fit and independent but who may be considering the future changes that may be required to improve their chances of successfully ageing in place. Providing members of the public with education regarding age-friendly design and home modifications may assist with future planning, thereby potentially preventing injury, reducing the fiscal pressures on the health care system and compensating for workforce shortages in health and aged care.

This qualitative study is part of a research program which seeks to develop a tool which enables older people (or their families) to self-assess their own homes. This tool will be available both in hard copy and as a digital tool and will be used to promote and support future planning in terms of the home environment. The first step in tool development is to conduct a needs assessment to understand the gaps between the ‘current state’ of older adults living at home and the ‘desired state’ of supporting ageing in place [Citation24]. This involves gathering data from older adults to gain a deeper understanding of ageing in place and home safety. As relatives often become involved in the housing decisions of older people and are potential users of the tool, we also wanted to understand their perspectives. Therefore, the aim of this qualitative study was to investigate the following research questions: (1) what are the perspectives of middle-aged and older people in relation to their own home environment, home safety and ageing in the home; (2) what are the experiences of individuals with older relatives and the difficulties their older relatives face as they age in place.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Flinders University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 1949). Eligible participants were provided with information about the study and provided informed consent. Interviews were conducted individually with the person over the phone (while they were in their own home) at a time convenient to the participant. Audio-recordings were transcribed and de-identified and data presented in a way that ensures participants remain anonymous. Participants were assured that they could choose not to answer questions if they felt uncomfortable and could end the interview at any time.

Research design

A qualitative descriptive method was used [Citation25]. The qualitative descriptive methodology was applied in order to understand descriptions of experiences and perceptions [Citation25,Citation26]. This methodology aims to collate the ‘who, what, and where of events or experiences’ from a subjective perspective [Citation27]. Semi-structured interviews were the preferred approach as it allows the researcher to address topics in their own terms pertinent to them and clarify views based on the development of answers [Citation28]. To ensure rigorous reporting of the methodology, this paper was written in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). See supplementary material [29].

Participants

We recruited participants to represent one of two categories. The first category involved people considered as ‘middle or older aged people’ invited to talk about their own personal experiences and plans for housing as they age. The second category involved people who had older relatives and we sought to understand the experience of being a family member providing support during the ageing process. Relatives (especially children) often become involved in the housing decisions of older people as they provide increasing support to ageing family members. The two groups were recruited separately so that participants in the first category were not known to those in the second category. Inclusion criteria for the first group were as follows: (a) aged 55–75 years old; (b) live in their own home; (c) speak fluent English; (d) cognitively intact. This age criterion was chosen to explore the views of adults who were likely to be relatively healthy and independent and thinking about planning for the future and these are the target end users of the tool in development.

The second group were: (a) aged 50 and over; (b) have parents who are still alive (c) live in their own homes; (d) speak fluent English; (e) cognitively intact. All participants were from metropolitan Adelaide, Australia and were identified and invited to participate through their membership of an online research panel hosted by a market and social research company (McGregor Tan, Adelaide, Australia) assisted only with the recruitment phase. The company manages a panel of over 20,000 respondents and identified panel members who met the eligibility criteria and agreed to participate in an interview.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by one of the authors (KL), over a one-month period. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions was used to explore participant’s perceptions and opinions of complex or emotionally sensitive issues [Citation30]. The question guide for the second group of participants (children) was slightly altered to seek their experiences and perspectives of having an older relative and family views and discussions about long-term housing decisions. Interviews started by giving participants (middle and older-aged people) opportunities to explain their overall thoughts about staying at home as they aged. Whereas the people with older relatives were asked about their experiences with ageing parents. For this study, individual semi-structured interviews were conducted until the data reached a point of saturation, (i.e. when further information no longer generated new ideas or understandings) [Citation31]. Probes were used to follow up on responses and promote discussion with each participant. No field notes were taken, nor were observations written regarding individual behaviours. Questions covered for both categories are detailed in Appendix 1 (wording modification to be made for the second category). All interviews were conducted one to one via phone due to restrictions associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. The interviews took approximately 30 mins each until their natural conclusion were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Recorded audio interviews were transcribed by an independent company. Data analysis was conducted by two investigators: RD and KL. All data were entered into NVivo 12 (software), Interviews were analysed inductively using thematic analysis. This study used reflexive thematic analysis to fully embrace the skills of the researcher and the qualitative research values [Citation32,Citation33]. Reflexive thematic analysis is used for research questions needing to describe the ‘lived experience of particular social groups’ or ‘to examine the factors’ that influence a particular phenomenon [Citation34]. The principal investigator familiarised themselves with the data and then coded the interview text independently (in NVivo). For example, the text, “They don’t want to let go of their independence, and I get it,” was assigned the code, “want to remain independent”. Codes were then reviewed to check for duplication and similar codes were grouped together as initial themes [Citation32,Citation33]. The investigators discussed, reviewed, and refined the themes until a consensus about their nature and relationship with other themes was reached. Socio-economic status was categorised according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics index of relative socio-economics advantage and disadvantage (IRSAD) [Citation35]. Each socio-economic area is given a score for a statistical area level, based on postcode (e.g. SA1) through the addition of weighted characteristics. The scores ranged from a low index score (more disadvantaged, SA1) to a high index score (most advantaged, SA5) [Citation35].

Results

A total of 16 participants were interviewed as presented in . Eight middle and older aged people discussed their own home environments and future housing plans and eight individuals with older relatives provided perspectives on the home environment and future planning for a relative. Four out of the eight middle and older aged people were males, while the remaining four were females. The middle and older aged people were aged between 67–76. Four of the individuals with older relatives were also males and the remaining four were females. Individuals with older relatives were aged between 52–65.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

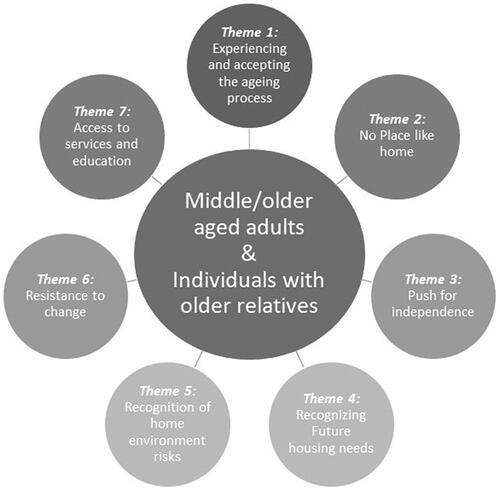

In total, seven themes represented participants’ perceptions of home safety, ageing in the home and the information older people need to assess their own home for safety emerged ().

These were: (i) experiencing and accepting the ageing process; (ii) no place like home; (iii) push for independence; (iv) recognising future housing needs; (v) recognition of home environment risks; (vi) resistance to change; (vii) access to services and education.

Theme 1: experiencing and accepting the ageing process

Individuals with older relatives and middle/older aged adults identified how a positive attitude towards ageing and being receptive to change and new information supported successful ageing in place and changes in behaviour. This is reflected by an individual with an older relative and a middle/older aged person:

Certainly at this point they’ve always been very positive and accepting that it’s okay. Individual with an older relative, Interview 16.

You have to be in the mindset to accept the information that’s presented to you. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 13.

I suppose in the future, you might have to have the usual bars to help you, assist, and all the rest of it, which we don’t have at the moment. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 6.

You’re responsible, so it’s up to you to take the initiative and the responsibility. Put it this way. I would have no problem, if things did get a bit difficult, in asking for help. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 2.

Middle/older aged adults who accepted the change and saw benefits to change were more open to home safety interventions such as home modifications, having an occupational therapist visit to install safety features or conducting home assessments:

I'm well controlled and everything’s not too bad, but, yes, I certainly would consider some modifications, not at the moment, but in the future. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

My wife’s going to have hip replacement in a couple of weeks. So we’re putting in some suction handles and things like that, just to facilitate ease for her for that. And obviously those sorts of things can be made permanent down the track. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 13.

I would certainly say that this experience now that she’s used the handrails and everything, she’s agreed that they’re actually good [occupational therapists]. So she’s probably a bit more open, but she’s still very distrustful and we still have to work very hard at her. Individual with an older relative, Interview 4.

If I was living alone, depends on the price of course, but I'd be amenable to having some professional look at it. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 11.

I think a lot of people don’t want to get professional help to come in because they’re concerned that it’s going to cost them too much or that they’re not going to get the answer they want. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 7.

Theme 2: no place like home

For all middle and older aged adults, their houses were their homes. Three out of eight middle and older aged adults planned to remain in their homes for as long as possible. When discussing her husband, one participant said:

He’s going to go out of this house is in his coffin. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 2.

Personally, I'd like to stay in my home. I mean, we’ve been in here 40 odd years. I'd like to stay here as long as possible, really. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 6.

My preference is to stay where I am as long as I can. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 7.

She’s [mother] just got this notion, she’s scared of losing the house. She thinks the nursing home’s going to take the house. We’re telling her, "No, they don’t," but yeah. Individual with an older relative, Interview 3.

Matter of moving into an aged care unit or something like that. I don’t think that would work. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 9.

There’s no way that she would accept going into a nursing home. So, yes, it’s difficult now. Yes. Individual with an older relative, Interview 1.

One individual with an older relative talked about their mother wanting to remain at home due to the worries of becoming a burden. This participant discussed how her mother has become a burden because she not allowing her to help make ageing in place easier:

She’s worried about contributing to the burden… And although, so we’re getting a little less tactful these days saying, "Mom, you are the burden because you’re not allowing us to just make it easy." Individual with an older relative, Interview 4.

Theme 3: push for independence

Participants strongly wanted to remain independent. Middle and older aged people reported that they currently felt active enough to continue living at home and not require assistance or home modifications. Five out of eight individuals with older relatives described the desire of their relative to remain independent; this was linked to pride and dignity.

They are fiercely independent. They have been serious travelers all of their lives. Individual with older relatives, Interview 8.

It’s like a self-preservation thing you just don’t want to admit, I suppose, to anyone let alone yourself. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

We’re both mid to late 60s, so we’re quite fit. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 13.

At the moment, I think I can manage pretty much everything. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 9.

Some individuals attempted to encourage their older relatives to be more proactive in seeking help, assistance and home modifications however had difficulty persuading their older family members.

I've tried to be proactive in helping mum, but she hasn’t been interested. Individual with older relatives, Interview 10.

Whilst other individuals tried to encourage their older relatives to live with them without the need to relocate.

I said to her, "Would you like to come and live with me when you’re older?" And she’s not open to that either, which is probably a good thing, but it was out. I put it out there just in case. "No, no," she said. "No, no, I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t like to do that." Individual with older relatives, Interview 1.

When I was young, you looked after your olds. They came and lived with you. You don’t anymore. It’s sad. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 2.

More than once we’ve had the conversation, "Well yeah mom, when we were kids and we needed you, you were there. And that was fantastic. But the reality is you’re in your 90s now, and now the tables have turned. We’re here to help you." Individual with older relatives, Interview 4.

Participants spoke about the importance of being able to choose what they do, how they spend their time in their homes, having control of their own routines and how this desire for autonomy played a role in their housing decisions.

Like I've even suggested to mum, at least, like I've said before, just if she does the bathroom and the vacuuming, and then you can do the other things. But she’s still not happy about that." Individual with older relatives, Interview 1.

I think we’re okay here. We’re reasonably close to shops. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 2.

Theme 4: recognizing future housing needs

Participants who were planning for future housing discussed either what modifications may be required over time or the possible need for relocation. Five out of eight middle/older aged adults identified the need to consider future housing plans. Some participants expressed the need to be proactive about future housing plans and discussed safety at home, for both now and the future:

We’ve been thinking about it, my wife and I. Five years, we’ve been sort of working out what we’re going to do about it. And on top of everything, she’s a physiotherapist. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 7.

I actually worked in an aged care facility, but I am aware of a lot of the modifications and frames and chairs and all sorts of things that’s around, yeah. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

I know several years ago we had to get some cementing done at the back. And I do remember my husband saying we should make this a slope just in case we have to have a wheelchair or anything like that in the future, which we have done. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 6.

We can’t just walk in and say, "Oh, I think we should do this. It’ll make your life easier." She wouldn’t just go, "Oh yeah, make it happen." We’d have to spend another hour on it to explain it all. Individual with older relatives, Interview 4.

Yes. I did talk to them about seeing an occupational therapist or a physio or someone and getting the right measurements, but they weren’t interested in that. Individual with older relatives, interview 10.

I have over the years been involved in putting handicap rails and that sort of thing in houses where someone’s had a stroke or something as an older person, and then they just need bits and pieces fixed into the bathroom Middle aged person, Interview 7.

Look, I would say probably showers and things like… because I live with my husband and he’s a little bit older than me and he has rheumatoid arthritis which is controlled at the moment. But I would say in the future, we’ll probably look at grab rails in the bathrooms, maybe shower chairs and we’ve also got a sunken lounge and both of us are quite capable of getting into and out of it at the moment, but in the future that could pose a problem. Middle/older aged person, Interview 14.

In fact, my first husband became very ill with a brain tumor, and we had a friend who was a carpenter and he actually put some rails in the shower and the toilet for him while he was ill. That was a bit of a preview of that sort of thing. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 9.

Theme 5: recognition of home environment risks

Six out of eight middle and older-aged adults and one individual with an older relative were able to distinguish current home hazards and age-related changes that could potentially affect their ability to age in place.

We might have to make some minor alterations to maybe where we’ve got steps, I suppose. But apart from that, everything’s fairly safe. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 6.

I've got little steps and things to use, long tongs to help me grab things. That’s really not a modification. Sometimes in the shower, if I think the floor could be a wee bit slippery, and I'm sometimes a bit worried that I might need a grab rail or something in there at some point in time. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 9.

The only thing I did think that maybe would be a help if PowerPoints were more a hip level. Not down. But that’s the way the house was built. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 5.

Four out of eight individuals identified no current home modifications in the houses of their older relatives.

I think nothing else has been done, as in modifications, stuff like that. Handrails and stuff like that, she hasn’t got any. Individual with older relatives, Interview 3.

So, as far as home modifications, regardless of boarder or not, I'm quite independent and can be at home with no real worries. Individual with older relatives, Interview 11.

Three individuals with older relatives described their experience with home modifications as having noticed their older parent struggling to mobilise or due to modifications already being in place.

They’ve got a rail there now. But dad put it in. My dad put it in, which is fine…. I think it was because I fell… They were afraid that other people might hurt themselves rather than them. Individual with older relatives, Interview 10.

The identification of home hazards may have been influenced by a middle/older aged person’s cultural background. One middle/older aged person described no issues that could be foreseen as issues

I don’t think houses in this country… I mean, obviously I’m form the UK, where you’ve got steps that are Everest-like. Middle/older aged person, Interview 2.

Factors such as health crises and age-related changes were identified as triggers for individuals with older relatives or middle and older aged adults to make home environment and housing decisions.

Theme 6: resistance to change

Individuals with older relatives spoke of resistance amongst their relatives to make changes or modifications. There was resistance to home modifications, assistance at home or the thought of relocation in the future.

Very resistant to the idea. The OT [occupational therapist] that came out, I mean, he was pretty understanding of the challenges quite often, but there’s usually a lot of pushback on, "It’s my house. I've never had these for the last 60 years. Why do I need now?" Individual with an older relative, Interview 4.

The fear of strangers attending to their home, home alterations not being suited to visitors, the stigma of ageing/disability and modifications being visually unappealing were all reasons for this resistance to change. Individuals preferred to be given the choice regarding home modifications to suit their aesthetics and function.

Because a lot of the equipment is very obviously clunky looking, awkward looking and it’s not streamlined looking. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

This middle/older aged adult also wanted modifications to be:

Aesthetically nicer looking but still functional. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

[They’re] not open to that yet…I think they’re taking it like a, it’s more like a day-by-day approach. Individual with an older relative, Interview 1.

They would wait for a trigger. So both of them, really. Mom … Especially my dad. Individual of an older relative, Interview 15.

I guess they may make some further changes that they might need. Individual of an older relatives, Interview 16.

I think people tend to leave it till they really need it or, till they need it. Yeah. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 6.

I'm not really worried about my safety in the home. If I trip over, I am probably getting clumsier. But I'll can sort of crawl out, yell out stuff. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 11.

But the point would be that you started to feel that it was a bit risky or you felt a little bit like you needed it at that point. Middle/older aged adult, Interview 14.

Theme 7: access to services and education

Individuals with older relatives reported that there was not enough information being shared or promoted about ageing in place, especially about home modifications and where you could obtain these. These individuals described many issues with the system, especially with the feeling of the lack of information being shared:

No, I don’t think there is a lot. I knew nothing until My Aged Care [government funded aged care support service] came on board. But even then, to me, I didn’t think there was enough information, but then I thought it might’ve been because I was new to all this because of mom. Middle/older aged person, Interview 16.

Mom actually had an ACAT assessment [assessment of aged care support needs] done, and I rather gather her and my sister and I are still sort of learning the ropes a little bit on this one. We find understanding that system to be a little bit of a minefield. Individual with an older relative, Interview 4.

I think it would be a good idea because especially you think of things, but there may be something that someone else knows about that you hadn’t even thought of. So I suppose some assistance might help in some areas. Yeah. Middle/older aged person, Interview 6.

I think many of those sorts of things are probably common sense, but yeah, there may be some things that we haven’t considered and there is an actual document of sorts. So yeah, we … certainly I wouldn’t be … against that. I don’t think, they wouldn’t mind being … assessing the house and just making some comments, see the certain things or … for example, the shower is probably one that is of concern given the nature of showers and wet areas. Individual with an older relative, Interview 16.

But I think mum would be interested. And I think she’d be surprised at the things that could be done, and that might give her a kickstart into actually talking to someone about getting it done. Individual with an older relative, Interview 10.

So for her, she’d never used any form of computer or mobile phone. She probably would look at something in the form of a printed document, she’d be open to that, for sure. She would look at it, might not admit to us that she has, but she would. Kat and I would use anything, printed form, anything, app really, just don’t care as long as it gets the result. Individual with an older relative, Interview 4.

I think at the moment, for the older age group, I'm 71, I'd say probably the majority of people over 75 or 80 would go for the paper. Middle/older aged person, Interview 2.

Whereas four individuals with older relatives and three middle/older aged people preferred electronic or online educational guides, depending on their comfortability and experience with technology:

Apps work really well for me, obviously, because I'm computer literate, but obviously I've got a stepmother who’s just not computer literate at all so she’d need a written one. But for purpose it would be an app. Middle/older aged person, Interview 14.

GP's the most trusted sort of source of information. Middle/older aged person, Interview 2.

Other individuals with older relatives and middle/older aged adults reported that they had attempted to seek information through online health service portals, their social networks, private organisations for modifications, the council or retail shops such as hardware stores.

Well, now that I'm being assessed, I'd probably go to My Aged Care. Middle/older aged person, Interview 5.

Maybe supermarket or Bunning’s. Middle/older aged person, Interview 5.

An independent living organization. And I'm not necessarily thinking straight away of a particular shop or retail outlet in that respect, because they’ve got their own barrows to push. Middle/older aged person, Interview 13.

With my Mum’s condition, she does go to a local council service that they provide. Individual with an older relative, Interview 16.

Discussion

Older adults reported a strong desire to remain independent and in their own homes. Relatives supported their family members although were sometimes concerned about the safety of the older person in their home environment and had difficulty convincing them to make changes to improve the safety or accessibility of the home. Both older people and family members reported some knowledge of home modifications that could be made although participants agreed that more information and tools to help with future planning would be beneficial. Participants had mixed opinions as to the preferred format with some preferring paper-based tools and others identifying digital health tools as being appropriate. The challenge remains regarding how to implement home assessment and modification at the right time as while some participants reported being proactive and planning ahead, others were reluctant to take action until essential, such as due to a health crisis.

The World Health Organisation’s vision is a society comprising age-friendly environments [Citation36]. To achieve this, middle and older aged people need to be engaged and involved in the process of designing, building, and adapting their own homes. However, involvement relies on the older person having the knowledge, tools, and resources to do so. The views and preferences of older people and their families should be included when planning and designing tools for older people to self-assess their own homes. This sentiment was echoed by Ollevier et al. [Citation37] who identified the importance of older adults being engaged in the development and evaluation of technology to support ageing, especially in home environments.

Age-related changes to one’s physical function influenced participants’ views on ageing in place. Feeling physically and emotionally strong led to an improved acceptance of the ageing process [Citation38]. Consistent with the findings from Shaw and Langman [Citation39], most older people who accepted their ageing trajectory, took the necessary steps to maintain and enhance their physical and mental health to remain at home. Whereas those who refused to accept a decline in ability, frustrated family members with older relatives [Citation40]. Participants in this study were also frustrated when older relatives were reluctant to accept changes or modifications.

Decisions regarding modification or relocation are complex and can be overwhelming and expensive. We found that older people in this study knew changes were needed to remain at home, had reasonable awareness of what modifications were possible and wanted more ways to make their home age-friendly. However, participants expressed a desire for more access to education. Similarly, Wang et al. [Citation41] described the need for more information and education about the home environment to inform older adults’ decisions as access to home modifications is one of the most critical factors as to why older people stayed or moved from their home rather than move into a residential care home [Citation42,Citation43]. Overall, individuals have the desire and willingness to participate in education and were interested in education and tools that could support this [Citation41].

Participants often reported waiting for a crisis to occur before making major housing decisions. Our findings were similar to Safran-Norton [Citation44] and colleagues who reported that older adults were still reluctant to make changes, even when there were factors that would trigger housing adjustments, such as living in two-story home with no bathroom on the first level. Changes to the home or moving seemed to be overwhelming or for some, it may have been considered too late due to the sudden change in health [Citation45]. Davey [Citation46] reported that older people were aware of the safety issues as they aged and thought about adaptations but were still hoping that they will be ok. Receiving education and tools from people with influence, such as family members, health professionals or the person’s GP may promote earlier decision-making. Although there has been a shift towards digital health tools, our participants had mixed views with some preferring digital tools but most preferring paper-based guides due to inexperience with technology. Other studies have found that older people were generally more accepting of digital health tools if they were provided with training [Citation47,Citation48]. Technology has the potential to facilitate conversations about the home environment between patients and their family members [Citation21].

Understanding the perspective of individuals with ageing relatives is important as families are often involved in managing health crises and decisions about housing. In 2018, 34% of older people reported relying on their spouse for support, 21% relied on a daughter and 17% relied on a son [Citation49]. As the population ages, the number of older people hoping to remain in their own homes will continue to grow and a decline in family support is expected due to families living further away and having limited capacity to assist due to their own work and family commitments [Citation50]. Involving both older people and family members in designing solutions as to how to successfully age in place is critical and family members may play a key role in bringing forward decision-making regarding housing.

Future recommendations

Older adults and families are open to receiving education about home safety and potential adaptations and modifications. Educational workshops and tools may increase awareness about options available and assist people to assess their own homes thereby prompting changes earlier, rather than later. Results of this study suggest that family involvement, linking with the community (e.g. GP, council) and having both digital and paper-based tools will increase uptake.

Limitations

This study showed the importance of consulting with middle and older aged people and family members. Whilst semi-structured interviews can provide rich data and provide multiple perspectives there are limitations. Although data collection reached a natural conclusion, the lengths of the interviews or depth may have been influenced by external factors, impacting data saturation, and understanding. It is possible that some data may have been overlooked during analysis and the small sample size may not encapsulate the perspectives of the broader population. In particular, recruitment via an online research panel may have resulted in a sample who were more technology literate with higher levels of education. Furthermore, there may be potential bias due to interviews and analyses being conducted by an occupational therapist.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the knowledge and support middle and older aged adults may need to assess their homes and approaches that might successfully promote ageing in place. Some participants accepted the ageing process, which promoted a positive outlook towards future housing decisions. Whereas those that waited for crises did not recognise the need to alter their homes. Despite this, middle and older aged people are open to education and would like access to information on home safety including home modifications. A tool (in both paper and digital form) which provides education and facilitates decision-making is acceptable and likely to be beneficial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organisation [Internet]. Ageing and Health. 2022 [cited 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health.

- Productivity Commission. Housing Decisions of Older Australians. Productivity commission Research paper. Canberra; 2015.

- Tanner B, Tilse C, de Jonge D. Restoring and sustaining home: the impact of home modifications on the meaning of home for older people. J Hous Elderly . 2008;22(3):195–215.

- Hatcher D, Chang E, Schmied V, et al. Exploring the perspectives of older people on the concept of home. J Aging Res. 2019;2019:2679680.

- Stones D, Gullifer J. At home it’s just so much easier to be yourself’: older adults’ perceptions of ageing in place. Ageing Society. 2014;36(3):449–481.

- Kramer C, Pfaffenbach C. Should I stay or should I go? Housing preferences upon retirement in Germany. J Hous Built Environ. 2015;31(2):239–256.

- Pani-Harreman KE, Bours GJJW, Zander I, et al. Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: a scoping review. Ageing Society. 2021;41(9):2026–2059.

- Aplin T, Canagasuriam S, Petersen M, et al. The experience of home for social housing tenants with a disability: security and connection but limited control. Housing Society. 2020;47(1):63–79.

- Coleman T, Wiles J. Being with objects of meaning: cherished possessions and opportunities to maintain aging in place. Gerontologist. 2020; 60(1):41–49.

- Glass AP, Vander Plaats RS. A conceptual model for aging better together intentionally. J Aging Studies. 2013;27(4):428–442.

- Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Social Care. 2017;25(3):799–812.

- Victor C, Grenade L. Boldy D. Measuring loneliness in later life: a comparison of differing measures. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2005;15(1):63–70.

- Ninnis K, Van Den Berg M, Lannin NA, et al. Information and communication technology use within occupational therapy home assessments: a scoping review. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;82(3):141–152.

- Podgórniak-Krzykacz A, Przywojska J, Wiktorowicz J. Smart and age-friendly communities in Poland. An analysis of institutional and individual conditions for a new concept of smart development of ageing communities. Energies. 2020;13(9):1–23.

- Novek S, Menec VH. Older adults’ perceptions of age-friendly communities in Canada: a photovoice study. Ageing Society. 2014;34(6):1052–1072.

- Severinsen C, Breheny M, Stephens C. Ageing in unsuitable places. Housing Studies. 2016;31(6):714–728.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [Internet]. Older Australians; 2021. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians/contents/housing-and-living-arrangements.

- Godfrey M, Cornwell P, Eames S, et al. Pre-discharge home visits: a qualitative exploration of the experience of occupational therapists and multidisciplinary stakeholders. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66(3):249–257.

- Stark S, Keglovits M, Arbesman M, et al. Effect of home modification interventions on the participation of community-dwelling adults with health conditions: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther 2017;71(2):7102290010p1.

- van Gaans D, Dent E. Issues of accessibility to health services by older Australians: a review. Public Health Reviews. 2018;39(1):1.

- Read J, Jones N, Fegan C, et al. Remote home visit: exploring the feasibility, acceptability and potential benefits of using digital technology to undertake occupational therapy home assessments. Br J Occup Ther. 2020;83(10):648–658.

- Lannin NA, Clemson L, McCluskey A. Survey of current pre‐discharge home visiting practices of occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58(3):172–177.

- Sim S, Barr C, George S. Comparison of equipment prescriptions in the toilet/bathroom by occupational therapists using home visits and digital photos, for patients in rehabilitation. Australian Occup Ther J. 2015;62(2):132–140.

- Stefaniak J. Needs assessment for learning and performance: theory, process, and practice. New York: Routledge; 2020.

- Doyle L, McCabe C, Keogh B, et al. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J Res Nurs. 2020;25(5):443–455.

- Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84.

- Kim H, Sefcik JS, Bradway C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: a systematic review. Res Nurs Health. 2017;40(1):23–42.

- Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2022.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Kallio H, Pietila AM, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965.

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7(2):e000057.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2020;18(3):328–352.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res. 2020;21(1):37–47.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016 2018; 2018. [cited 2022 2022 Nov 30]. Available from: abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001∼2016∼Main%20Features∼IRSD%20Interactive%20Map∼15.

- World Health Organisation [Internet]. UN decade of healthy ageing 2021–2023; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade-of-healthy-ageing.

- Ollevier A, Aguiar G, Palomino M, et al. How can technology support ageing in place in healthy older adults? A systematic review. Public Health Rev. 2020/11/2341(1):26.

- Bosch-Farre C, Mc M-A, Ballester-Ferrando D, et al. Healthy ageing in place: enablers and barriers from the perspective of the elderly. A qualitative study [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):04.

- Shaw R, Langman M. Perceptions of being old and the ageing process. Ageing International. 2017;42(1):115–135.

- Macdonald J, McDermott D, Woods M, et al. editors. A salutogenic approach to men’s health: challenging the stereotypes. 12th Australian National Health Promotion Conference, Melbourne; 2000.

- Wang S, Bolling K, Mao W, et al. Technology to support aging in place: older adults’ perspectives. Healthcare. 2019;7(2):60.

- Davey JA, de Joux V, Nana G, et al. Accommodation options for older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Centre for Housing Research Christchurch; 2004.

- Hwang E, Cummings L, Sixsmith A, et al. Impacts of home modifications on aging-in-Place. J Hous Elderly. 2011; 25(3):246–257.

- Safran-Norton CE. Physical home environment as a determinant of aging in place for different types of elderly households. J Hous Built Environ. 2010; 2010/05/2524(2):208–231.

- Molinsky J, Forsyth A. Housing, the built environment, and the good life. Hastings Center Report. 2018;48: s 50–S56.

- Davey J. Ageing in place": the views of older homeowners on maintenance, renovation and adaptation. Soc Policy J NZ. 2006;27:128.

- Tsertsidis A, Kolkowska E, Hedström K. Factors influencing seniors’ acceptance of technology for ageing in place in the post-implementation stage: a literature review. Int J Med Inf. 2019; 2019/09/01/129:324–333.

- Klimova B, Poulova P, editors. Older people and technology acceptance. Human aspects of IT for the aged population. Acceptance, communication and participation; 2018. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: summary of findings: Abs; 2018. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release.

- Gaugler J, Schulz R. Bridging the family care gap. Innovation in Aging. 2021;5(Supplement_1):267–267.

Appendix 1

Interview questions designed for group of older people with slight modification to wording for the second group who represent children of older people.

Introduction: “Research shows that most people want to remain in their own homes for as long as possible. But over time people might need some modifications to help with safety”

What are your main concerns about staying in your own home environment as you age?

Are you familiar with modifications that may be made to the home?

Have you had any modifications to your own home? What type and who made them?

Where have you received information about the types of modifications that are available? And do you know much about the costs of modifications?

What are your thoughts about having a professional assess for these and make recommendations? Or is it something you think you could do yourself (ie common sense)?

What do you think about having a professional make the modifications? Or would you ask a family member to help with this type of thing Information sharing: We are looking at designing a type of checklist which would help people (or their family members) to review their own home and identify the types of things that might be helpful to do in advance.

What are your thoughts about doing a self assessment? Would you like to do this or do you lack confidence in your knowledge and skills

What format might suit best? (eg online, mobile app, written)

Who would be the best person to distribute this? (eg local council, COTA, health department, GP)

Do you have any examples of good ‘self assessments’ that you’ve used before?

Is there any other information that you think would be helpful related to this topic?