Abstract

Background

The assessment of work ability with reliable, thoroughly tested instruments, is central to evidence-based occupational therapy practice.

Aims/Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the Finnish version of the WRI with a focus on construct validity and measurement precision.

Material and Methods

Ninety-six WRI-FI assessments were performed by 19 occupational therapists in Finland. A Rasch analysis was conducted to evaluate the psychometric properties.

Results

The WRI-FI presented an overall fit to the Rasch model, with good targeting and separation among persons. The four-point rating scale structure was supported by the Rasch analysis, except for one item with disordered thresholds. The WRI-FI indicated stable measurement properties across gender. Seven of the 96 persons showed misfit, which slightly exceeds the criteria of 5%.

Conclusions

The findings from this first psychometric evaluation of the WRI-FI provided evidence of construct validity and support for measurement precision. The hierarchy among items corresponded with previous studies. The WRI-FI can offer occupational therapy practitioners a valid tool to evaluate psychosocial and environmental perspectives of persons’ work ability.

Introduction

In Western society, work is highly valued and fills a central place in people’s adult lives, thus important for people’s well-being. Recent statistics, globally, within the Euro area and in Finland show an unemployment rate between 6–7% [Citation1–3]. Of all unemployed people in Finland, 30–40% are long-term unemployed, and of those 50% have partial work ability due to disabilities [Citation4]. New flexible solutions to increase labour market participation are needed, especially for people with partial work ability. The Finnish government has identified this as one of the strategic focuses [Citation5]. In order to enhance people’s abilities to return to work or entry to the labour market, it is essential to comprehensively evaluate and assess their work ability using a multifaceted and holistic approach [Citation6,Citation7]. This approach should incorporate diverse perspectives from various professionals, including occupational therapists who can provide valuable insights into the assessment process [Citation8]. Assessment of work ability with valid, thoroughly tested instruments, is critical in making well-founded evidence-based decisions regarding vocational rehabilitation interventions for clients [Citation9,Citation10]. The Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare [Citation11] highlights the importance of reliable and valid assessment practices. Assessment tools used in occupational therapy practice, such as The Worker Role Interview (WRI), have been considered useful when it comes to identifying psychosocial and environmental aspects that influence a person’s ability to return to work, remain in work, or get employment in general [Citation12–14]. Moreover, the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) [Citation15], which is the theoretical foundation for the WRI, has been recognised as successful for use within occupational health. It has been used specifically to describe the multiple influences on individual work disability [Citation16].

The WRI is an assessment instrument that uses a semi-structured interview for data collection, originally developed to gain an understanding of psychosocial and environmental perspectives of the work ability of injured workers or persons with longstanding illness or disability. The latest original version WRI 10.0 incorporated significant changes, including the removal of a redundant item and adjustments made to the interview guide and the rating scale to ensure their suitability for clients with limited or no work history [Citation17]. Research on the WRI has been ongoing since the early 1990s, and the findings have been regarded during subsequent revisions. Additionally, the WRI has been translated and culturally adapted into several languages, and its validity and reliability have been evaluated in various studies involving clients with different diagnoses in the somatic health area [Citation10,Citation18,Citation19], the mental health area [Citation20,Citation21] and with mixed client groups [Citation19,Citation22–25]. The WRI 10.0 has demonstrated favourable psychometric properties [Citation10,Citation21]. Furthermore, a study conducted in Sweden focussing on the clinical utility of the WRI found that it was perceived as effective, easy to use, and relevant by both respondents and occupational therapists in the vocational rehabilitation area [Citation12], highlighting its potential as a valuable tool in practice. The WRI assessment has also been found to be valid in predicting factors relevant to people’s ability to return to work after sick leave [Citation22,Citation23].

An old Finnish version of the WRI has been published previously [Citation26] but is seen as outdated and is therefore no longer available. For the new Finnish version [Citation27], the original WRI 10.0 was used as a basis. In accordance with recommendations regarding steps in the process of translating assessment instruments, further testing is crucial in order to provide evidence of reliable and valid clinical use of the assessment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the Finnish version of the Worker Role Interview (WRI-FI) with a focus on construct validity and measurement precision. Specifically, this study addresses the following questions, recommended by Hobart and Cano [Citation29]. Is the scale-to-sample targeting adequate for making judgements about the performance of the scale and the measurement of people? Has a measurement ruler been constructed successfully? Have the people been measured successfully?

Material and method

This study was a psychometric evaluation of the WRI-FI to provide evidence of reliable and valid clinical use of the assessment instrument. The ethical committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa has approved the study, diary number §281/2017(HUS/3072/2017).

Participants

Occupational therapists were recruited nationwide to participate as data collectors on a voluntary basis through open recruitment via the website of Metropolia University of Applied Sciences and the occupational therapy association in Finland. Inclusion criteria demanded participants have an occupational therapy degree and work with an evaluation of clients’ work ability in their daily work. No certain field of practice was prioritised. Twenty-three occupational therapists took part in a one-day training session on the use of the WRI-FI prior to data collection. In addition, they participated in two meetings to support the process.

Background information of all 23 participants has been collected anonymously. Twenty-two of the occupational therapists were female and one was male. Of the participants, 17 reported practising in secondary care (somatic or mental health), three in primary health care, one was self-employed, one worked in a social service setting and one in a community organisation. A majority (n = 16) reported over ten years of clinical experience. All of the participants were familiar with the MOHO [Citation15] and 15 of the therapists used it as a guiding conceptual model in practice. All but four of the occupational therapists (n = 19) were familiar with using the old Finnish version of the WRI [Citation26].

Of the 23 participants, 19 collected data for this study as part of their regular clinical work. The four occupational therapists that did not collect data did not report a reason. Which of the 23 occupational therapists that performed the data collection was not known to the authors due to the anonymity of the background information.

Instruments

The new WRI-FI version was used [Citation27], which consists of 16 items (). In the MOHO, the occupational behaviour of human beings consists of motivation, lifestyle and performance capacity in interaction with the context [Citation15]. The individual’s motivation for work is in the WRI described through three theoretical concepts: personal causation, values, and interests (items 1–7). Lifestyle influencing work is described by two theoretical concepts: roles and habits (items 8–12). The theoretical description of the environment (items 13–16) includes the individual’s perception of the physical and social environment in relation to his or her work situation.

Table 1. Individual item-fit of the WRI-FI items in ascending location order and number of ratings for each item on the 4-point rating scale.

Data collection

Data was collected through interviews using one of the two semi-structured WRI-FI interview guides. The first interview guide (A) is to be used when the person has a workplace to relate to, while the second guide (B) is suitable for persons that have been outside the labour market for a long time due to, e.g. long-term unemployment or long-term sick-leave, or those who have not entered the labour market. The occupational therapist chose guide A or B based on the work status of the client. After completing the interview, the WRI items were rated using the four-point rating scale, by the occupational therapist. A value of ‘1′ implies that the item strongly interferes with returning to work or getting into working life, ‘2′ implies that the item interferes with returning to work or getting into working life, a value of ‘3′ implies that the item supports a return to work or get into working life, and value ‘4′ implies that the item strongly supports returning to or get into working life. When using the second interview guide some of the items (numbers 10, 13, 15, 16) are often not applicable (NA) and the rating NA is used. Thus the number of rated items across clients varies.

The occupational therapist did the assessment using the WRI-FI rating form. The information collected was transferred by the occupational therapist from the rating forms to separate forms for data collection, without the personal data of the clients. The anonymized rating forms were delivered to the research group by either regular mail or in person. All forms were on paper.

WRI-FI ratings

In total, 96 WRI-FI ratings were collected. Those clients who were rated were between 21-67 years old, where 59% (n = 57) were female and 41% (n = 39) were male. Clients (n = 96) had one or more diagnoses, where the majority of the diagnoses were mental or behavioural diagnoses (61%); the remaining 39% were somatic diagnoses. Of the 96 WRI-FI assessments, interview guide A was used for employed clients (57%), and interview guide B for unemployed clients (43%).

Statistics

Rasch analysis

Demographic information was analysed using IBM SPSS version 27 [Citation28]. In the Rasch analysis, the WRI-FI ratings of the 96 participants were analysed with the RUMM2030 software, using the polytomous unrestricted model [Citation30]. The Rasch analysis of an existing scale is about gathering and integrating the evidence from a series of analyses to judge the psychometric properties of the scale [Citation29]. For each of the questions mentioned below, different analyses, tests, and related visual representations in the RUMM2030 were interpreted.

Is the scale-to-sample targeting adequate for making judgements about the performance of the scale and the measurement of people?

Investigating the relative distribution of the item and person locations provides information concerning the suitability of the sample for evaluating the scale and the suitability of the scale to measure the sample, which gives a frame of reference for interpreting the other results of the analyses [Citation29]. Regarding the WRI-FI, scale-to-sample targeting focuses on the match between the range of psychosocial work ability measured by the WRI-FI and the range of work ability measured in the present study sample. Scale-to-sample targeting was investigated by using the histogram of person-item distribution and the related summary statistics and test of fit to the model [Citation29,Citation30].

Has a measurement ruler been successfully constructed?

To assess the correspondence between observed data and the models’ expectations, five different aspects were evaluated [Citation29]. First, the WRI-FI is intended to measure psychosocial work ability with 16 items defining the latent trait of psychosocial work ability. The WRI-FI items should work together to define a cohesive continuum. That is, the responses to items should be predictable and in agreement with the ability of persons. This is measured using different fit statistics to test the fit of the data to the model [Citation29]. For the WRI-FI, fit residuals, chi-square and an item characteristic curve (ICC) were used. Ideally, the individual item fit residuals should be between ±2.5; the chi-square values should not be statistically significant, and the dots of the class intervals should follow the ICC to support a good fit in the graphical representation [Citation29]. For the items to map out the continuum of psychosocial work ability, they must be located at different locations along the trait to measure ‘low and high’ ability. If the WRI-FI items mapped out a continuum was addressed by examining the items’ threshold locations, their range and spread, as well as their proximity to each other and the precision of the estimates (standard error) [Citation29]. Third, for the WRI-FI scale with multiple response categories that imply low to high psychosocial work ability, the thresholds of categories should be sequentially ordered [Citation29], which was investigated by studying the category probability curves. Collapsing response categories could potentially solve the disordering of thresholds [Citation31] and were applied when response categories were used by fewer than 10 respondents in two or more of the four rating categories in an item. Lastly, Differential Item Functioning (DIF) was statistically evaluated in relation to gender to ensure that the items perform in a similar way for men and women, which is needed in order to be able to ensure meaningful comparisons [Citation32]. Due to multiple tests, Bonferroni correction was applied.

Are the people in the sample measured successfully?

This aspect was examined in three components, where reliability, item-person distributions and person fit residuals were considered. The extent to which the WRI-FI scale detects differences between people in the sample and changes over time was assessed with the Person Separation Index (PSI), analogous to Cronbach’s alpha. PSI ranged from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater separation among the persons in the sample and the greater power of the test of fit to detect fit [Citation29,Citation30]. Further, the PSI value was converted into strata to investigate how many clinically relevant groups the scale can separate between [Citation33,Citation34]. The mean person value/location indicates whether the present sample is centred or off-centred on the items (mean of 0), implying measurement precision [Citation29]. The person fit residuals (analogous to item fit residuals) were assessed to examine the validity of people’s measurements, acceptable in the range of ±2.5.

Results

Do the WRI-FI items work together to define a single construct?

The WRI-FI showed an overall fit to the Rasch model (χ2 = 33.118; df = 32; p = .41). Examined by the Fit statistics and the related Chi-square, no fit residuals were above the critical value of ±2.5 indicating that the items fit the model expectations.

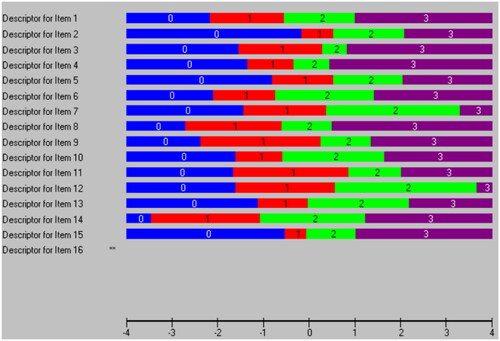

The item hierarchy, i.e. the arrangement of items from those that represent the least to the most psychosocial work ability, is shown in . The WRI-FI items 14, ‘Perception of family and peers’ and 8 ‘Appraises work expectations’, represented the least amount of the construct, i.e. they were the easiest items and items 12 ‘Adapts routine to minimise difficulties’ and 2 ‘Expectations of job success’ represented the largest amount of the construct, i.e. ., they were the hardest items in the construct. The hierarchical order of item difficulty corresponded well with the expectations of more and less challenging items in relation to psychosocial work ability.

Is the scale-to-sample targeting adequate for making judgements about the performance of the scale and the measurement of people?

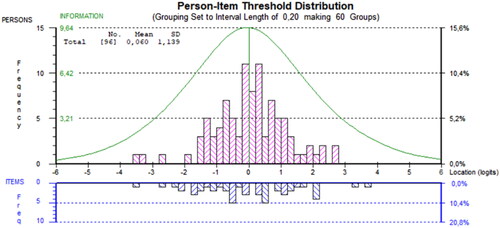

There was a spread of item locations to map out a continuum of psychosocial work ability. shows the locations of item response category thresholds relative to the locations of the sample. The scale-to-sample targeting presented good targeting, since the person mean (0.06, SD 1.14) was close to the item mean (0), i.e. the difference (0.06 logits) of mean logit calibration of item and person was well within the acceptable criterion of 0.5 logits. Further, the range of the sample was well matched with the range of ability measured by the WRI-FI.

Figure 1. Targeting of the WRI-FI, the sample providing a representation of the measurement ruler mapped out by the 16 WRI-FI items.

The PSI for the WRI-FI was 0.87 indicating that persons were well separated, and this provided evidence that the test of fit was able to detect misfit if present. The PSI further implied that the WRI-FI separated the sample into 4 strata (groups).

Has a measurement ruler been successfully constructed?

Examination of the response categories revealed that the thresholds, except for item 16, were ordered as intended, see . For all WRI-FI items except item 16, a higher rating score confirmed more psychosocial work ability measured by the specific item.

Figure 2. The threshold map of the 16 WRI-FI items represents the functioning of the four response categories* in the rating scale. Note*: Response category 0 corresponds to a WRI-FI rating of 1, 1 to rating 2, 2 to rating 3 and 3 to rating 4.

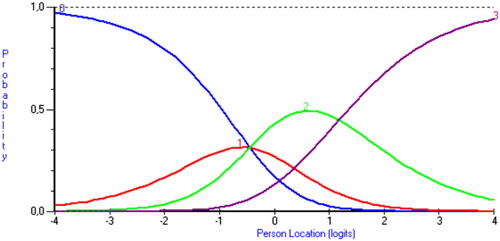

Among the 16 WRI items, item 16 “Perception of co-workers” was the only item with fewer than 10 ratings in two of the four rating categories, see . The categories with few ratings in item 16 were category 1 (4 ratings), and 2 (8 ratings). In item 16, the probability of obtaining a score of 1 (indicating that the item interferes with the individual’s psychosocial work ability) was never most likely for the persons, see . Therefore, the rating categories of 1 (0) and 2 (1) were collapsed for item 16 so that the item had 3 rating categories that were correctly ordered in the analyses.

Is performance stable across gender?

No significant DIF for gender was found (p < 0.001, Bonferroni-adjusted).

Are the people in the sample measured successfully?

Regarding the person response validity, the results showed that 7% (n = 7) of the persons in the sample misfit the model’s expectation, i.e. they had fit residuals outside the recommended range of ±2.5. Of these seven persons, three of them had fit residuals close to the recommended range. All persons remained in the analysis.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of the translated Finnish version of the WRI. The results from this first psychometric evaluation of the WRI-FI provide evidence of being a reliable and valid assessment to measure psychosocial work ability. The relative distribution of the item and person locations (scale-to-sample targeting) suggested a valid frame of reference for interpreting the Rasch analysis [Citation29]. Overall, the data confirmed the model’s expectations, indicating a good fit and support for the construct validity of the WRI-FI. The hierarchy among items corresponded with previous studies [Citation10,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25] and was considered clinically relevant among this client group from different clinical settings.

The 16 WRI-FI items mapped out a continuum of psychosocial work ability on which clients can be measured, which is important to separate among person’s ability and capture change between time points [Citation29]. The scale could validly separate persons in the sample into four groups of psychosocial work ability. Taken together, in a clinical context, this means that the WRI-FI can identify persons’ psychosocial work ability and is sensitive enough to distinguish between different levels of the attribute. Thus, the results imply that WRI-FI can provide valid information on a persons’ potential need for interventions and support to improve their psychosocial work ability. Furthermore, the assessment can be used as an outcome measure to evaluate the effect of occupational therapy intervention on psychosocial work ability.

The rating categories worked as intended, except for item 16, indicating an overall acceptable functioning. The disordered thresholds of item 16 might depend on the rare use of the lowest rating categories (rating 1 and 2) [Citation35], as the item was rated as supportive for returning to work or getting into working life for most (78%) of the clients. Furthermore, being an item with a high drop-out because of the dependability of a related workplace, information about client’s perceptions of their co-workers (item 16) could not be collected, and the NA rating was used for 43% (n = 41) of the clients. The demonstrated shortcoming of item 16 is, however, in need of further investigation if present also in future studies.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include the rather small sample size, which limited the possibility to conduct other DIF analyses, than among gender. The heterogeneous sample of the present study is desirable and would have enabled further DIF analyses if it had been larger. To conduct DIF analyses concerning different diagnoses and educational levels, for example, is therefore recommended in future studies to enhance the generalisation of the results among groups. Seven of the 96 participants showed misfit, which slightly exceeds the criterion of 5%. This misfit was further explored, which led to the conclusion that inconsistencies in the persons’ response patterns were present and collected background information could not explain the identified misfit. Since excluding participants with misfits from the analysis did not result in any notable changes, they were kept in the dataset. The potential presence of invalid response patterns among persons should be an observandum in future studies. Furthermore, the data did not allow an analysis of rater severity among the occupational therapists which would be a subject for further study.

Clinical implication

Using the WRI-FI [Citation27] assessment can offer occupational therapy practitioners and researchers a valid tool to evaluate the psychosocial and environmental perspectives of persons’ psychosocial work ability. Furthermore, since the WRI- FI [Citation27] is grounded in the conceptual model MOHO [Citation15], the assessment results can inform interventions and support evidence-based practice in occupational therapy in Finland. The WRI-FI [Citation27] could thus contribute to clarifying the occupational therapy perspective as part of the multi-professional team when it comes to assessing and supporting work ability in Finland, both within traditional health care as well as new areas, such as occupational health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the occupational therapists that collected the data and provided the WRI-FI ratings that enabled the present study.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Statista [Internet]. Global unemployment rate. 2023. [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/279777/global-unemployment-rate/.

- OECD data [Internet]. Unemployment rate. 2022. [cited 2023 Mar 8]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/unemp/unemployment-rate.htm.

- Statistics Finland [Internet]. Unemployment rate. 2023. [cited 2023 May 5]. Available from: https://www.stat.fi/en/statistics/tyti.

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland [Internet]. Work ability programme 2022. Available from https://stm.fi/en/work-ability-programme1.

- Finnish government [Internet]. Finland built on trust and labour market equality. 2023. [cited 2023 Jan 12]. Available from: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/marin/government-programme/finland-built-on-trust-and-labour-market-equality.

- Kerätär R, Taanila A, Jokelainen J, et al. Work disabilities and unmet needs for health care and rehabilitation among jobseekers: a community-level investigation using multidimensional work ability assessments. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(4):343–351. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2016.1248632.

- Cronin S, Curran J, Iantorno J, et al. Work capacity assessment and return to work: a scoping review. Work. 2013;44(1):37–55. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-01560.

- Suomen Toimintaterapeuttiliitto ry [Finnish Occupational Therapy Association] [Internet] 2021. Available from: www.toimintaterapeuttiliitto.fi.

- Sandqvist J, Ekbladh E. Applying the model of human occupation to vocational rehabilitation. In: Taylor R, editor. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolter’s Kluwer; 2017.

- Köller B, Niedermann K, Klipstein A, et al. The psychometric properties of the German version of the new worker role interview (WRI-G 10.0) in people with musculoskeletal disorders. Work. 2011;40(4):401–410. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2011-1252.

- TOIMIA-tietokanta. Toimintakyvyn mittaamisen ja arvioinnin kansallisen asiantuntijaverkoston tietokanta. [The national expert network for measuring and evaluating performances Functioning Measures Database] Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos [Finnish institute for health and welfare] [Internet] 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 14]. Available from: https://thl.fi/fi/web/toimintakyky/etusivu/toimia-tietokanta/toimia-verkosto.

- Yngve M, Ekbladh E. Clinical utility of the worker role interview: a survey study among Swedish users. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22(6):416–423. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2015.1007161.

- Järvikoski A, Takala E-P, Juvonen-Posti P, et al. Työkyvyn käsite ja työkykymallit kuntoutuksen tutkimuksessa ja käytännöissä [The concept of work abili- ty in the research and practice of rehabilitation.] Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Social security and health reports 13, 2018. pp. 86

- Hemmingsson H, Forsyth KH, Keponen R, et al. Talking with clients: assessment that collect information through interviews. In: Taylor R, editor. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation. Fifth ed. Philadelphia: Wolter’s Kluwer; 2017. p. 275–309.

- Taylor R, editor. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. Fifth ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Loisel P, Anema JR. Handbook of work disability: Prevention and management. New York: Springer; 2013.

- Braveman B, Robson M, Velozo C, et al. The Worker Role Interview (WRI),(version 10.0). Model of human occupation clearinghouse. University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2005.

- Biernacki SD. Reliability of the worker role interview. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47(9):797–803. doi: 10.5014/ajot.47.9.797.

- Velozo CA, Kielhofner G, Gern A, et al. Worker role interview: toward validation of a psychosocial work-related measure. J Occup Rehabil. 1999;9(3):153–168. doi: 10.1023/A:1021397600383.

- Haglund L, Karlsson G, Kielhofner G, et al. Validity of the Swedish version of the worker role interview. Scand J Occup Ther. 1997;4(1-4):23–29. doi: 10.3109/11038129709035718.

- Lohss I, Forsyth K, Kottorp A. Psychometric properties of the worker role interview (version 10.0) in mental health. Brit J Occup Ther. 2012;75(4):171–179. doi: 10.4276/030802212X13336366278095.

- Ekbladh E, Haglund L, Thorell L-H. The worker role interview—preliminary data on the predictive validity of return to work of clients after an insurance medicine investigation. J Occup Rehabil. 2004;14(2):131–141. doi: 10.1023/b:joor.0000018329.79751.09.

- Ekbladh E, Thorell L-H, Haglund L. Return to work: the predictive value of the worker role interview (WRI) over two years. Work. 2010;35(2):163–172. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0968.

- Fenger K, Kramer JM. Worker role interview: testing the psychometric properties of the icelandic version. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(3):160–172. doi: 10.1080/11038120601040743.

- Forsyth K, Braveman B, Kielhofner G, et al. Psychometric properties of the worker role interview. WORK. 2006;27(3):313–318.

- Forsman B, Ihander J, Kaunola R, et al. Työroolia arvioiva haastattelu (WRI). [Finnish version of Velozo C., Kielhofner G. & Fisher G 1998]. A users guide to the worker role interview. 9th ed. Helsinki: Psykologien Kustannus Oy; 1998.

- Nyman J, Keponen R, Nisula S. Työroolin arviointi WRI-FI [Finnish version of: braveman, B., Robson, M., Velozo C., Kielhofner G., Fisher G., Forsyth, K. & Kerschbaum, J. 2005. A users guide to the Worker Role Interview (10th ed.)] 2019.

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. 2020.

- Hobart J, Cano S. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Asses. 2009;13(12):9–10.

- Andrich D, Sheridan B, Luo G. RUMM2030 software and manuals. Perth, Australia: University of Western Australia; 2013.

- Tennant A, Conaghan PG. The rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a rasch paper? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1358–1362. doi: 10.1002/art.23108.

- Hagquist C, Andrich D. Recent advances in analysis of differential item functioning in health research using the rasch model. Health Qual Life Out. 2017;15(1):1–8.

- Linacre J. Sample size and item calibration stability. Rasch Mes Trans. 1994;7:328.

- Schumacker RE, Smith EV.Jr A rasch perspective. Educ Psychol Meas. 2007;67(3):394–409. doi: 10.1177/0013164406294776.

- Andrich D, De Jong J, Sheridan BE. Diagnostic opportunities with the rasch model for ordered response categories. In applications of latent trait and latent class models in the social sciences. New York: Waxmann; 1997. p. 59–70.