Abstract

Background

Information and communication technology (ICT) provides one solution to meet increasing demands for occupational therapy for older adults.

Aims/Objectives

To examine if and how municipality-based occupational therapists (OTs) include ICT in their work, and which factors are associated with use of occupational therapy at a distance.

Material and Methods

Survey study including 167 OTs. Data were presented descriptively. Associations were analysed by Chi2 test and logistic regression models.

Results

Forty-eight percent of OTs used ICT once a month or more. OTs belief on possibilites to use ICT is associated with replacement of physical home visits. Managers expectations and support also seem to be important factors.

Conclusion

ICT solutions are frequently used by OTs in home health care and can be considered complementing rather than replacing physical home visits. More knowledge is needed on when and how ICT solutions can be used by OTs and how factors that impact the use of ICT can be managed.

Introduction

Due to an ageing population worldwide, and larger numbers of people living with consequences of disease and injury there is an increasing need for health care services, including occupational therapy, [Citation1]. Given that the number of occupational therapists (OTs) is limited, one way to improve the availability of occupational therapy is to provide services at a distance through Information and Communication Technology (ICT) [Citation2]. Adding to this line of reasoning, the competency description for OTs interationally as well as in Sweden emphasise that OTs should have the competence to work digitally, to use digital systems, interact digitally, and adapt activities to digitalisation [Citation3,Citation4].

Different concepts are used in this field of research and practice to describe how health care services and rehabilitation is delivered at a distance by ICT, e.g. e-health and tele rehabilitation [Citation5]. Whereas e-health is an overarching term covering how ICT is used to affect health, telerehabilitation is more specifically focused on the delivery of rehabilitation services at a distance by using ICT. In the present study the concept ICT will be used in relation to occupational therapy delivered at a distance directed at clients, relatives, and staff, including various solutions, e.g. direct use of ICT in real time, for example by videoconferences or phone calls, or indirectly, by using for example recorded videos or messages [Citation6]. Whereas some researchers argue that OTs are suitable to and should push digitalisation forward to support peoples’ everyday lives, and to promote occupational justice and health [Citation7], recent reviews provide promising evidence that OTs can perform assessment, intervention, and evaluation through ICT [Citation8–11]. Examples of ICT-solutions used by OTs are videoconferencing, phone calls, text messaging, applications, other web-based interventions [Citation8] and photographs [Citation12]. While phonecalls is an established technology, more recent ICT solutions, e.g. new applications can provide both opportunities and challenges for OTs [Citation7]. Applications and other web-based interventions can for example be used to increase physical activity by providing individualised exercise programs or fall prevention through balance training. Photographs can provide the OT with a clearer picture of the client’s home environment, for exampel when discussing fallprevention, when a physical home visit (PHV) is not carried out [Citation12].

The research on occupational therapy delivered at a distance through ICT with older adults mainly include studies with a small number of participants [Citation12–18] and studies that lack randomisation [Citation12–17,Citation19]. However, the results of these studies indicate that occupational therapy at a distance delivered through ICT could be an alternative to PHVs to provide occupational therapy for older adults. Interventions delivered through ICT that have been studied within occupational therapy include fall-prevention programs [Citation12,Citation18,Citation20], hand and arm exercise [Citation15], and strategy training in ADL-performance [Citation13]. Two studies show similar results for occupational therapy delivered by using ICT as occupational therapy delivered through PHV regarding technical aids [Citation17,Citation20]. In addition, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) [Citation21], indicated that delivery of a dementia care program through ICT showed the same results on caregiver assessment of dementia clients’ function and activities of daily living, as delivery of the same program using PHV. Previous studies have shown that assessments of home environment and risk of falling [Citation16,Citation19], body function measurements [Citation22], and technical aid needs assessments [Citation17] are feasible and potentially cost-effective to perform through ICT. Whereas the emerging evidence base is promising, we identified only three studies conducted in Sweden with a focus on rehabilitation delivered by using ICT [Citation20,Citation23,Citation24]. None of these studies examined occupational therapy exclusively. One study focused on older adult’s perceptions and experience of a digital fall-prevention program [Citation20] and one on a more digitalised community [Citation23]. The third Swedish study [Citation24] examined perceptions about the transition towards digital home visits early during the COVID-19 pandemic among staff in social care and home health care. Whereas respondents reported having access to the technical equipment required to use ICT for service delivery, only one third used it [Citation24].

To address the expected demand of health care services due to an ageing population [Citation25] different initiatives focused on how to improve access to such services by the use of ICT have been initiated in Sweden [Citation26,Citation27]. To enable a transition towards making use of the potential in digitalisation, the Swedish government have allocated extra resources focused on development and use of technical solutions and digital working methods [Citation25]. While the use of ICT increased in municipal social care and home health care early during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation28], there seems to be differences in the actual use of ICT depending on contextual factors such as municipality size. In Sweden, municipalities with a high number of inhabitants, social care and home health care staff use more ICT in their work than staff in municipalities with few inhabitants [Citation28]. Other enabling or hindering factors that seem to be important in the use of ICT in occupational therapy world wide are expectations and support from managers, OTs own belief that ICT is possible in occupational therapy, strategies and guidelines, policy changes, education [Citation11], poor administrative support, lack of knowledge [Citation25], lack of access to technology, limitations in technology, and an inertia in system changes to implement and use digital solutions [Citation11]. Also in a Swedish context, the lack of access to technology and limitations in technology, e.g. limited internet connection, have been identified as hindering factors.

Whereas the use of thechnology in occupational therapy to facilitatie participation in occupations is identified as a prioritised research area by the World Federation of Occupational Therapists [Citation29], there are few studies on occupational therapy at a distance through ICT in Sweden. Specifically, there is a lack of knowledge about how OTs work with ICT in social care and home health care for older adults in Swedish municipalities, and how different factors have an impact on the implementation of such work. The aim of this study is to examine (i) if and how OTs in municipal social care and home health care for older adults include ICT in their work and (ii) which factors are associated with the use of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT. The specific research questions were:

How do OTs include ICT in their work for older adults in municipal social care and home health care?

Which factors are associated with if occupational therapy at a distance through ICT replace PHVs?

To what extent does different factors explain replacement of PHVs by occupational therapy at a distance through ICT?

Material and methods

Design

A cross-sectional design [Citation30], including a web-survey was used to address the purpose and research questions.

Participants and recruitment

OTs who worked in municipal social care and home health care for older adults were eligible to participate. The Local Authority Senior Rehabilitation Advisor (LASRA) network [Citation31] in Sweden was used as a national recruitment base for this study. In Swedish municipalites the LASRA is responsible for the quality assurance of rehabilitation in home health care. At the time of the recruitment, the LASRA network included 96 LASRAs in 84, out of Sweden’s 290, municipalities. Five municipalities had more than one LASRA. An e-mail was sent to all 96 LASRAs in the beginning of December 2021 including information about the study, a question about the municipality’s willingness to participate in the study, and if the LASRA accepted to be a contact person transferring information from the researcher and the OTs in each municipality. In January 2022 reminders were sent to the LASRAs who had not already answered. By the end of January, LASRAs from 34 municipalities had expressed interest to participate in the study and agreed to be a contact person. Based on estimates from the LASRAs these municipalities included approximately 610 OTs. To get as accurate picture as possible of how OTs worked with ICT in Swedish municipalities, it was important to include as many respondents and as broad representation of OTs from different municipalities as possible. Therefore, there was no limit on number of participants determined in advance; participants in this study were those OTs who considered themselves eligible and consented to participate.

To inform participants about the study, an information letter was sent out to the LASRAs who forwarded it to the OTs. The letter included information that it was voluntary to participate and that neither the manager nor LASRA would find out whether they had chosen to participate or not.

Data collection

Data were collected through a web survey created in Microsoft Office Forms. A link to the web survey was included in the information letter sent to the OTs. The letter was distributed on January 20th 2022 to the LASRAs who forwarded it to the OTs. In February 2022 a reminder was sent out. The last day to respond to the survey was February 25th 2022.

The questionnaire was constructed for this study and consisted of 38 questions. The first question was about giving informed consent to participate in the study. The remaining 37 questions were constructed with support from literature [Citation32], literature about occupational therapy and ICT [Citation8,Citation10,Citation24,Citation33] and feedback from a panel of OTs (n = 7), and one LASRA. OTs in the panel worked in different areas of occupational therapy, including older adults and younger clients, in municipal home health care and within regional settings. Feedback from the panel resulted in changes in sentence constructions and clarifications, more options were added in multiple-choice questions and questions were added to separate which ICT OTs use to perform assessments, interventions, and follow-ups. The guestionnaiare consisted of 10 likert scale questions, 25 nominal scale multiple-choice questions, two nominal scale questions with free text answer and one free text answer question. Twenty-two questions were designed to answer the first research question and focused on what type of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT the OTs performed (eight questions), and which type of ICT-solutions they used (14 questions). One question ‘How often OTs replace a physical home visit with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT’ was designed both for descriptive reasons and as a dependent variable to analyse which factors were associated with the use of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT (research question 2 and 3). Twelve questions were designed as independent variables to answer the second and third research questions. The independent variables were municipality size, access to hardware, access to ICT-solutions (software, e.g. computer programe, applications), knowledge in how to use ICT, education in how to use ICT, guidelines, governing documents or policies, support from manager, administrative support from IT department, managers expectations, OTs belief if it is possible to use ICT in occupational therapy, limiting factors, and motivating factors.

Ethics

Ethical considerations were based on the Helsinki Declaration [Citation34]. Since no sensitive personal information was collected through the survey and the nature of the questions entailed a low degree of emotional risk for the participants, an ethical application was not required. The survey results were submitted anonymously, and data was analysed and presented at a group level. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, that data was treated confidentially, that participation was voluntary and that neither the LASRA nor manager would be informed if they chose to participate or not. Participants received contact information to the authors to be able to ask questions about the study. In the first question of the questionnaire the OTs were asked about informed consent to participate in the study and the OT were informed that by answering yes to that question he/she consented to participate in the study.

Analysis

All data collected through the web surveys were organised in Microsoft excel and exported to the statistics program Jamovi version 1.6.23.0. Given the number of respondents and distribution of responses, dichotomisation of ordinal data was used to separate positive responses from negative responses. For example, in the question about OTs opinion about access to ICT-solutions, responses were dichotomised as positive, including response options ‘very good’ and ‘quite good’, or as negative including response options ‘not so good’, ‘bad/none’ and ‘don’t know’. On a question about how often OTs had replaced PHV with a digital meeting on a regular basis, responses were dichotomised as ‘yes’, including response options ‘once or more times a day’, ‘4-6 times a week’, ‘1-3 times a week’ and ‘1-3 times a month’ or as ‘no’ including response options ‘never’ and ‘less than once a month’.

To answer research question 1, questions focused on what type of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT that the OTs included in their work were analysed and presented descriptively in frequency tables. The answers of both direct and indirect ICT-tools were combined to present which assessments, interventions, and follow-ups that the OTs performed through ICT. Direct ICT-tools include e.g. videoconference, phonecall, chatt, text-message (related to direct communication). Indirect ICT-tools include e.g. applications, e-mail, pre-recorded video, text-massage (related to indirect communication such as reminders).

To answer the second research question, chi2 tests were used to analyse which factors were associated with if the OTs had replaced PHV with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT on a regular basis [Citation30]. These factors were: access to hardware, access to ICT-solutions, knowledge how to use ICT, education in how to use ICT, guidelines, manager support, administrative support, manager’s expectations, and OTs own beliefs in using ICT in occupational therapy. These factors were chosen since they previously have been identified in relation to occupational therapy at a distance through ICT in the literature [Citation35]. The descriptive analysis showed that two other factors (that OTs got a better overall picture when using PHVs than ICT and that ICT is a good complement to PHVs) might be important, since a large proportion of the OTs identified them as limiting or motivating factors respectively. Thus, those two factors were added to the chi2 tests. In addition to the survey data, municipality size was included as a factor, based on the municipality the OTs answered they worked in. The municipalities were categorised into three groups according to Sweden’s municipalities and regions sectioning [Citation36]. Group A include large cities and municipalities near large cities (more than 200 000 inhabitants), group B include medium-sized towns and municipalities near medium-sized towns (more than 50 000 inhabitants), and group C include smaller towns/urban areas and rural municipalities (less than 50 000 inhabitants) [Citation36]. In this study, LASRAs from five group A municipalities (approximately a total of 220 OTs), 18 group B municipalities (approximately a total of 270 OTs) and 11 group C municipalities (approximately a total of 120 OTs) agreed to be contact person for the OTs in their municipality.

To answer the third research question, a logistic regression analysis was performed [Citation35]. All variables that were significant in the chi2 tests were included in a multivariate logistic regression to examine to what extent different factors explained replacement of PHVs by occupational therapy at a distance through ICT. A multicollinearity test showed no significant correlation between variables [Citation35]. The logistic regression was performed, including calculation of odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. The McFadden pseudo R2 test [Citation37] was used to describe the overall effect size of the factors on the outcome. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant for both the chi2 tests and the logistic regression.

Results

In all, a total of 167 OTs from 36 municipalities agreed to participate in the study. Out of the 167 OTs, 10 OTs from 4 municipalities responded to the survey despite that the LASRA had not agreed to be contact person. There were two municipalities where the LASRAs agreed to be contact person, but no OT responded to the survey. One OT responded to the survey but declined to participate in the study; the responses from this OT were excluded. With regards to municipality size, 38 OTs (23%) worked in a group A municipality, 77 OTs (46%) worked in a group B municipality and 52 OTs (31%) worked in a group C municipality.

Occupational therapy at a distance through ICT

There were 25 OTs (15%) who stated that they did not use occupational therapy at a distance through ICT. Out of the OTs that replied they used occupational therapy at a distance through ICT (n = 142), 56% used ICT with community-dwelling clients, 27% used ICT with both community-dwelling clients and clients living at special housing and 17% used ICT with clients living at special housing. One hundred and thirty-seven (82%) OTs considered occupational therapy at a distance through ICT to be a complement to PHV whereas 18% replied that occupational therapy at a distance through ICT can never replace PHV. None of the OTs replied that occupational therapy at a distance through ICT can completely replace PHV.

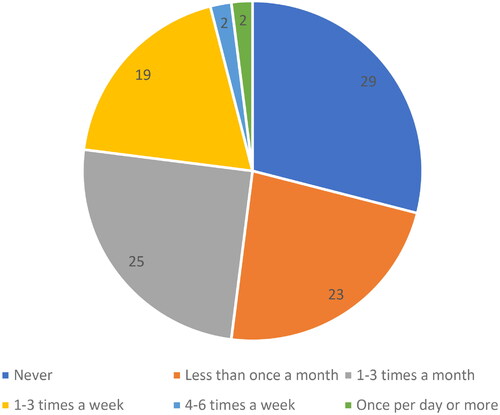

Approximately half of the OTs answered that they never, or less than once a month had replaced a PHV with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT and the remaining 48% of the OTs replied that they replaced PHVs with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT on a more regular basis (new ).

Figure 1. Proportion (%) of occupational therapists who replaced a physical home visit with occupational therapy at a distance through information and Communication Technology (ICT).

The hardware that most OTs had access to were smart phones and/or laptops and the ICT-solutions most OTs had access to were phone calls, e-mails, or videoconferences ().

Table 1. Occupational therapists’ accesses to hardware and information and Communication Technology (ICT) -solutions (nTable Footnotea= 167).

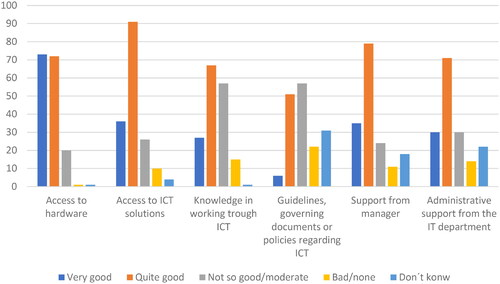

In all, the OTs reported having very good or quite good access to hardware (87%) and ICT-solutions for occupational therapy at a distance through ICT (76%) (). Only 21% of the OTs had received education in using ICT, but despite that, more than half of the OTs replied that they have very good or quite good knowledge of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT ().

Figure 2. Occupational therapists’ access to hardware and information and Communication Technology (ICT) -solutions, knowledge and education, guidelines, and support to use ICT (n = 167).

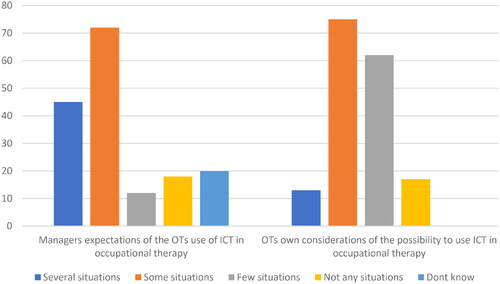

One of four OTs (23%) replied that their manager did not expect them to use ICT in any situation or that they did not know if the manager expected them to use ICT (). More than half (53%) of the OTs considered it is possible to use ICT in several or some situations ().

Figure 3. Occupational therapists’ (OTs) considerations of their managers expectations, and the possibility to use information and Communication Technology (ICT) in occupational therapy (n = 167).

The assessments, interventions, and follow-ups that most OTs replied they performed through ICT were focused on technical aids, see . Other assessments and follow-ups OTs performed through ICT were focused on the home environment, mobility and occupational performance, and interventions regarding supervision of staff or relatives, or giving instructions/counselling. The OTs performed more follow-ups than assessments through ICT. There were OTs that replied they never had performed assessments (41%), interventions (26%) or follow-ups (15%) through ICT. However, only 11 (7%) of the OTs replied that they never had performed either assessment, intervention, or follow-up through ICT.

Table 2. Assessments, interventions and follow-upsTable Footnotea that occupational therapists performed through information and Communication Technology (ICT).

The type of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT that most OTs performed were communication with staff (84%), relatives (78%) and clients (76%). Phone calls, followed by SMS, and e-mails, were the most frequently used ICT-solutions (). Almost 10% of the OTs highlighted that they worked through secure systems.

Table 3. Description of information and Communication Technology (ICT) -solutions used in occupational therapy at distance (nTable Footnotea = 167).

The OTs replied that there were several factors that limited or motivated them to use ICT (). The factor that most OTs (68%) considered limited the use of ICT was that PHVs provided a better overall picture of the client and the client’s situation. The factor that most OTs (77%) considered to be motivating was that occupational therapy at a distance through ICT is a good complement to PHVs. In addition, around half of the OTs considered it was fun to try something new and highlighted that it could save time and reduce environmental impact. In all, 19 (11%) of the OTs considered there were no limitations in using ICT in occupational therapy, whereas 12 (7%) of the OTs responded they were not motivated to work with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT.

Table 4. Occupational therapists (OTs) motivating and limiting factors for occupational therapy at a distance through information and Communication Technology (ICT) (n = 167).

Factors associated with occupational therapy through ICT

Based on the chi2 tests, factors that were associated with if the OTs had replaced PHV with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT on a regular basis (once a month or more) were: access to ICT-solutions, support from manager, if the manager expects the OTs to use ICT in several or some situations and the OTs belief that it is possible to use ICT in occupational therapy in several or some situations ().

Table 5. Factors associated with if the occupational therapists replaced PHVa with occupational therapy at a distance through information and Communication Technology (ICT) once or more a month. n = 167.

When variables that were significant in the chi2 tests were included in the logistic regression model, the results showed that the OTs belief that it is possible to use ICT in occupational therapy in several or some situations was the only statistically significant factor (). These results indicate that the probability to replace a PHV with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT is more than twice as high when OTs believe it is possible to use ICT in occupational therapy in several or some situations compared to OTs that only believe it is possible to use ICT in few or no situations, see . In addition, support from the manager had a similar effect on the probability that PHVs were replaced although the difference was not significant. Results of the McFadden pseudoR2 indicate that 10,7% of the difference in the outcome is explained by the four factors together ().

Table 6. Logistic regression model for replacing PHVTable Footnotea with occupational therapy at a distance through information and Communication Technology (ICT) once or more a month (n = 167).

Discussion

The findings from this study indicate that nearly half of the OTs use occupational therapy at a distance through ICT in Swedish municipal social care and home health care for older adults on a regular basis. These results are in line with recent studies, wich showed an increased use of ICT the past years worldwide [Citation11] as well as in Sweden [Citation28]. One explanation might be that restrictions implemented to reduce physical contacts during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to an increased use of easily accessible ICT that could be implemented quickly in Swedish municipalities [Citation28]. The increased use of occupational therapy at a distance through ICT found in this study, compared to previous studies [Citation11,Citation27,Citation32], may also be a result of recent extra resources from the Swedish government and Sweden’s Municipalities and Regions, to develop digitalisation in Swedish municipalities [Citation25,Citation26].

Although nearly half of the OTs replied that they used occupational therapy at a distance through ICT on a regular basis, the results indicate that ICT seem to be a good complement, rather than replacement for PHVs. There might be various reasons to why the OTs consider ICT as a complement rather than a replacement of PHV. One reason is that some tasks are difficult to perform through ICT since the task itself requires physical presence. In line with a previous study [Citation33], also when OTs use ICT the most frequent focus is on technical aids. In contrast, whereas walking indoors was frequently addressed by OTs in general municipality practice [Citation33], walking was seldom addressed through ICT. These findings indicate that certain tasks appear to be easier or more suitable to perform through ICT, as shown previously [Citation24]. In OT practice, OTs must acknowledge each individual client with regards to their unique situation and conditions through a person-centered approach and minimise exposure to risks [Citation38]. For activities that involve potential risks, e.g. fallrisk in relation to walking or performing activities, using ICT for assessment and intervention may not be considered suitable. While previous research has shown that it is possible to perform fall risk-prevention programs through ICT, these programs involved environmental changes [Citation14] or balance exercise [Citation22] and not training in activity. To further develop how ICT is implemented in a safe and efficient manner, there is a need for more research to establish which specific tasks are suitable for occupational therapy at a distance through ICT.

The result that OTs who believe it is possible to use ICT, are more than twice as likely to replace PHVs to OTs who do not think it is possible is not surprising. Findings from a recent study including OTs responding to a global survey provide some understanding to the importance of believing in possibilities to use ICT. Initiating use of ICT led to experiences on benefits of using it and stimulated further interest on how to use ICT in other situations [Citation11]. The finding that only one OT in five had received education in using ICT-solutions whereas more than half of the OTs considered themselves to have good knowledge raises the question which type of education is needed. The rapid increase in the use of ICT in municipal occupational therapy due to the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation11], might have forced OTs to learn how to use ICT which stimulated knowledge through learning by doing rather than through education. Gaining experiences in which situations ICT is possible and suitable to use seems to be important if larger numbers of OTs are to use ICT as part of their practice, which in turn may contribute to a more resource efficient use of limited OT resources by making use of the potential in ICT. However, since OTs should have the competence to work digitally and use digital systems [Citation3], education in combination with practice to gain practical, relevant experiences on the possibilities to use ICT with regards to assessment, intervention and follow-up in different situations is needed. In addition, to ensure optimal use of ICT, education and supervision for others involved in OT practice such as home care staff and clients is also important [Citation11]. To strengthen the evidence base and to guide education in this area, there is a need for reasearch to identify when and how ICT can be used in occupational therapy, explore reliability when assessments are made through ICT and evaluate effects on health and cost-effectiveness of interventions delivered using ICT in comparison to PHVs.

Our results indicate that access to equipment for ICT (both hardware and ICT-solutions) was good, and it seems as there had been an increase in access to equipment since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to a previous study [Citation24]. This increase may be a result that extra resources allocated to municipalities in 2021, were primarily used for digital equipment [Citation28]. Good access to equipment is necessary since ICT-solutions is a prerequisite to be able to perform occupational therapy at a distance through ICT. While phone calls were the most frequently used ICT solution, this cannot be considered new or innovative. Nevertheless, using phone calls is a solution something that all OTs have easily access to and therefore can use as a feasible option to replace or complement some aspects of PHVs with. In contrast, other aspects e.g. assessment of a client’s occupational performance is likely difficult to conduct by phone, as there is a risk of misjudgments due to a lack of visual information [Citation39]. The quality of such assessments could potentially be enhanced if a videocall was used. However, the benefit of using different ICT-solutions remains to be further explored. In a Canadian study on ICT-use in occupational therapy for older adults, including different areas of practice, commonly used technologies aimed to support for example communication, e.g. by text to speech applications, video calls; cognition, e.g. by using calendar, remainder or timer applications; knowledge about health status e.g. by diagnosis-specific websites and health applications [Citation40]. Taken together, there is a wide range of opportunities to integrate ICT in occupational therapy practice in terms of conducting assessments and intervention, communication between the OT and the client, relatives, and other staff, as well as providing ICT-based solutions to empower the client to manage his/her situation.

One additional perspective that warrants further research is that many older adults in need of municipal social care and home health care have physical and/or cognitive impairments which, in combination with lack of knowledge and equipment makes it difficult for them to use a videoconference [Citation5,Citation24]. Thus, factors related to the client’s situation might also be reasons to why almost half of the OTs reported that ICT is not suitable to use with their clients. When communication directly with the client is difficult, communication through staff or relatives may be more feasible. A large proportion of the OTs used ICT to communicate with staff and relatives, which is in line with results from a previous study [Citation5]. Also, during the COVID-19 pandemic, communication with staff through ICT-solutions were frequently used in Swedish municipal social care and home health care [Citation28]. Previous studies have shown that videoconferencing can be used when communicating with a caregiver to a client with dementia regarding care, activities of daily living and home-safety [Citation18,Citation21,Citation29]. It is always important for OTs to consider ethical aspects in relation to the client and for example respect the client’s integrity and self-determination [Citation38]. When performing occupational therapy with caregivers to clients with dementia through videoconferencing the ethical aspects may be even more important since a client experiencing cognitive impairments may be restricted to adequately speak for him/herself. Thus, video conferencing has a potential to provide a clearer picture of the client’s needs and it seems possible to perform through a caregiver, but at the same time it is important to consider ethical aspects when using it.

Ethically, it is also important that the OTs safeguard the clients’ integrity and have the possibility to work in secure systems to follow laws and guidelines, and to make sure that no information about the client spreads to a third party [Citation38]. The importance of working through secure systems was seen in this study, since over 10% of the OTs specified that they worked in secure systems, even though no question was asked about it. While secure systems appear to be an important issue for OTs and that it is a prerequisite for the use of ICT [Citation28], it has also been identified as a challenging factor in the transition towards increased occupational therapy at a distance through ICT [Citation24]. This highlights that further research and development related to secure systems for ICT is important.

While the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare states that it is important that the municipalities have clear guidelines in how to integrate ICT in municipal social care and home health care [Citation28], almost one fifth of the OTs replied that they did not know if they had guidelines, governing documents, or policies regarding ICT at their work. Since supportive guidelines, policies and strategies have been identified as an enabling factor for the use of ICT [Citation11], this is an area of improvement.

Even though not significant in the logistic regression, the support and expectations from the manager appear to be of importance regarding if OTs replaces PHVs with occupational therapy at a distance through ICT or not. These findings are in line with previous research [Citation5,Citation11,Citation24]. One explanation might be that it is important to get active support from the manager during implementation of new methods [Citation41], and routines for digital solutions [Citation42]. In contrast, results from a recent study in Canada indicated that managers support was considered a facilitator for recommending occupational therapy at a distance through ICT for less than one in five OTs [Citation40].

Limitations

The distribution of the survey through the LASRA network contributed to a sample of OTs representing a range of municipalities in different parts of Sweden, but at the same time it brought limitations to the study. Since only about one third of the Swedish municipalities have a LASRA, the LASRA network as a recruitment base might not be representative. In all, 34 of 84 municipalities with a LASRA (40%) participated in the study but considering all Swedish municipalities only 11% of Swedish municipalitis were represented in the study. An estimate of response rate (27%) is not exact since the number of OTs working in the participating municiaplities was an approximazation as reporetd from the LASRAS. Another limitation is that there is no data on how many OTs the LASRAs sent the survey to in each municipality. Since OTs answered the survey from municipalities where LASRAs did not respond to the request to be contact person it is not known if they sent the survey to their OTs anyway, or if OTs forwarded the survey to OTs in other municipalities. From two municipalities where the LASRAs agreed to be contact person, there were no respondents. Potential reasons for non-participation and low response rate could be that OTs did not have time to answer the survey due to workload or the short period of time the OTs had access to the survey. A third reason might be that the topic was somewhat new and did not evoke the interest to participate [Citation30]. If so, there might be an overrepresentation of OTs that had knowledge and experience in using occupational therapy at a distance through ICT among the participants. Given the recruitment base and the relatively small sample size, the results are not generalisable to all OTs in Swedish municipal social care and home health care for older adults. An additional, limitation was that no data on age, gender or educational level was collected. Therefore, more complex statistical analyses, including potential confounders such as age, gender, educational level could not be conducted. To address the limitations in the current study, we recommend a broader recruitment strategy aiming to reach a larger proportion of Swedish municipalities as well as a large sample of OTs. Whereas the survey was based on literature about occupational therapy and ICT and developed in an iterative process including a panel of OTs and one LASRA we acknowledge that validity and reliability of the survey was not explored beforehand which is a further limitation of this study.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that ICT could be a complement to physical home visits in occupational therapy. Almost half of the OTs used ICT on a regular basis in municipal social care and home health care for older adults. At the same time, it appears as if ICT is not suitable for certain clients and some tasks since physical presence is needed. The OTs own belief that occupational therapy at a distance through ICT can be used in several or some situations seems to be an important factor for the use of ICT. To further develop occupational therapy at a distance through ICT, managers’ support and expectations seems to be of importance as well as access to ICT-solutions and clearer guidelines. In addition, education, including examples of when and how to use ICT-solutions in a safe and efficient manner seems to be needed to increase OTs readiness to use ICT. While ICT-use in occupational therapy in Swedish municipalities is an emerging field, we conclude that more research is needed in this area to guide education as well as practice.

Authors contributions

CL co‐ordinated the study, analysed and interpreted the data and completed the drafting of the paper. Both authors contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of the data, the drafting of the paper and approved the final version before submission.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank all occupational therapists and LASRAS that contributed to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rehabilitation 2030 Initiative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2023 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/rehabilitation-2030.

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists. World federation of occupational therapists’ position statement on telehealth. Int J Telerehabil. 2014;6(1):1–13. doi:10.5195/IJT.2014.6153.

- Swedish association of occupational therapists. Competence descriptions for occupational therapists. Nacka: Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists; 2018.

- Technology for Occupation and Participation Network. Canadian Association of Occupational therapists; 2022. [cited 2023 June 10]. Available from: https://caot.ca/site/prac-res/otn/technology.

- Nyman A, Zingmark M, Lilja M, et al. Information and communicaton technology in home-based rehabilitation - a discussion of possibilities and challenges. Scand J Occup Ther. 2023;30(1):14–29.

- American Occupational Therapy Association. Telehealth. [Position paper]. American Occupational Therapy; 2013. p. 69–90.

- Larsson-Lund M, Nyman A. Occupational challenges in a digital society: a discussion inspiring occupational therapy to cross thresholds and embrace possibilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(8):550–553. doi:10.1080/11038128.2018.1523457.

- Hwang NK, Jung YJ, Park JS. Information and communications Technology-Based telehealth approach for occupational therapy interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(4):355. doi:10.3390/healthcare8040355.

- Ding J, Yang Y, Wu X, et al. The telehealth program of occupational therapy among older people: an up-to-date scoping review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023;35(1):23–40. doi:10.1007/s40520-022-02291-w.

- Nobakht Z, Rassafiani M, Hosseini SA, et al. Telehealth in occupational therapy: a scoping review. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2017;24(12):534–538. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2017.24.12.534.

- Hoel V, von Zweck C, Ledgerd R. Was a global pandemic needed to adopt the use of telehealth in occupational therapy? Work. 2021;68(1):13–20. doi:10.3233/WOR-205268.

- Breeden LE. Occupational therapy home safety intervention via telehealth. Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8(1):29–40. doi:10.5195/ijt.2016.6183.

- Kringle EA, Setiawan IMA, Golias K, et al. Feasibility of an iterative rehabilitation intervention for stroke delivered remotely using mobile health technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;15(8):908–916. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1629113.

- Zahoransky MA, Lape JE. Telehealth and home health occupational therapy: clients’ perceived satisfaction with and perception of occupational performance. Int J Telerehabil. 2020;12(2):105–124. doi:10.5195/ijt.2020.6327.

- Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Chan M. H-GRASP: the feasibility of an upper limb home exercise program monitored by phone for individuals post stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(9):874–882. doi:10.3109/09638288.2016.1162853.

- Renda M, Lape JE. Feasibility and effectiveness of telehealth occupational therapy home modification interventions. Int J Telerehabil. 2018;10(1):3–14. doi:10.5195/ijt.2018.6244.

- Sim S, Barr CJ, George S. Comparison of equipment prescriptions in the toilet/bathroom by occupational therapists using home visits and digital photos, for patients in rehabilitation. Aust Occup Ther J. 2015;62(2):132–140. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12121.

- Gately ME, Trudeau SA, Moo LR. Feasibility of telehealth-delivered home safety evaluations for caregivers of clients with dementia. OTJR. 2020;40(1):42–49. doi:10.1177/1539449219859935.

- Daniel H, Oesch P, Stuck AE, et al. Evaluation of a novel photography-based home assessment protocol for identification of environmental risk factors for falls in elderly persons. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13884. doi:10.4414/smw.2013.13884.

- Mansson L, Lundin-Olsson L, Skelton DA, et al. Older adults’ preferences for, adherence to and experiences of two self-management falls prevention home exercise programmes: a comparison between a digital programme and a paper booklet. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):209. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01592-x.

- Laver K, Liu E, Clemson L, et al. Does telehealth delivery of a dyadic dementia care program provide a noninferior alternative to face-to-face delivery of the same program? A randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28(6):673–682. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.02.009.

- Hoenig H, Tate L, Dumbleton S, et al. A quality assurance study on the accuracy of measuring physical function under current conditions for use of clinical video telehealth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(5):998–1002. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.009.

- Fischl C, Lindelöf N, Lindgren H, et al. Older adults’ perceptions of contexts surrounding their social participation in a digitalized society-an exploration in rural communities in Northern Sweden. Eur J Ageing. 2020;17(3):281–290. doi:10.1007/s10433-020-00558-7.

- Ahlin K, Zingmark M, Persson ST. A transition towards digital home visits in social care and home health care during the corona pandemic. In: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Global Health Challenges, Barcelona, Spain; 2021.

- Swedish Government. Agreement between the state and Sweden’s municipalities and regions on elderly care technology, quality and efficiency with the elderly in focus [Överenskommelse mellan staten och sveriges kommuner och regioner om äldreomsorg -teknik, kvalitet och effektivitet med den äldre i fokus]. Stockholm: Swedish government and Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions; 2020. Swedish

- Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Vision e-health 2025: common starting points for digitization in social services and healthcare. [vision e-hälsa 2025: gemensamma utgångspunkter för digitalisering i socialtjänst och hälso- och sjukvård]. Stockholm: swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions; 2016. Swedish

- Swedish Government Official Reports. Good and integrated care - a primary care reform. [god och nära vård - En primärvårdsreform]. Stockholm: Swedish Government Official Reports (Statens Offentliga utredningar [SOU]); 2018. p. 39. Swedish

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. E-health and welfare technology in municipalities 2021: monitoring the digital development in social services and municipal health care [e -hälsa och välfärdsteknik i kommunerna 2021: uppföljning av den digitala utvecklingen i socialtjänsten och den kommunala hälso- och sjukvården]. Stockholm: The National Board of Health and Welfare; 2021. Swedish

- Mackenzie L, Coppola S, Alvarez L, et al. International occupational therapy research priorities. OTJR. 2017;37(2):72–81.

- Carter RE, Lubinsky J. Rehabilitation research: principles and applications. 5th ed. St. Louis (MO): Elsevier; 2016.

- The National Association for Medically Responsible Nurses and Medically Responsible for Rehabilitation. What is a local authority senior rehabilitation advisor? [vad är MAR?]. Stockholm: The National Association for Medically Responsible Nurses and Medically Responsible for Rehabilitation. Available from: https://swenurse.se/sektionerochnatverk/riksforeningenformedicinsktansvarigasjukskoterskorochmedicinsktansvarigaforrehabilitering/vadarmar.4.35a497f417684413418eb8.html. Swedish.

- Persson A. Questions and answers – about question construction in questionnaires and interview surveys [frågor och svar– om frågekonstruktion i enkät och intervjuundersökningar]. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden; 2016. Swedish.

- Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. Characteristics of occupational therapy and physiotherapy within the context of reablement in Swedish municipalities: a national survey. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(3):1010–1019. doi:10.1111/hsc.12934.

- World Medical Association. WMA declaration of Helsinki - Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(4):373–374.

- Osborne JW. Best practices in logistic regression. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE; 2015.

- The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Categorization of municipalities [kommungruppsuppdelning]. Stockholm; 2017. Swedish. Available from: https://skr.se/skr/tjanster/kommunerochregioner/faktakommunerochregioner/kommungruppsindelning.2051.html.

- Mcfadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behaviour. New York (NY): Academic Press; 1974.

- Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists. Code of ethics for occupational therapists [in swedish: Etisk kod för arbetsterapeuter]. Nacka: Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists; 2018.

- Karlsson M, Nelsson C. Structured assessment in distance consultations [in Swedish: Strukturerad bedömning viktig vid konsultation på distans]. Swed Med J. 2017;(11):114.

- Aboujaoudé A, Bier N, Lussier M, et al. Canadian occupational therapists’ use of technology with older adults: a nationwide survey. OTJR. 2021;41(2):67–79. doi:10.1177/1539449220961340.

- Salmela S, Eriksson K, Fagerström L. Leading change: a three-dimentional model of nurse leaders main tasks and roles during a change process. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(2):423–433. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05802.x.

- Hofflander M. Implementing video conferencing in discharge planning sessions: Leadership and organizational culture when designing IT support for everyday work in nursing practice [dissertation] Karlskrona: Blekinge Institute of Technology; 2015.