Abstract

Background

For many children, public playgrounds represent environments that are playful and important in developing good health. Without efforts to facilitate climate change adaptation of outdoor playgrounds there may be a negative impact on children’s health and well-being.

Aim

With a special focus on play value, to explore the reasoning and described strategies among professionals responsible for development, planning and solutions concerning outdoor playgrounds in the context of climate change.

Materials and methods

Eight semi-structured interviews were held with purposefully selected interviewees. Analysis was conducted with manifest content analysis.

Results

Four themes with supporting categories; 1: a new design paradigm for outdoor play environments, 2: a need for updated regulation- and security guidelines for outdoor play environments, 3: nature-based play environments are more climate change resilient, and 4: maintenance and construction of nature-based outdoor play environments. The findings showed an overall awareness and a will to use innovative and nature-based strategies and planning to deal with climate change implications for outdoor play environments.

Conclusions and significance

The findings suggest that the strategies employed lean towards implementation of increased ecosystem services and natural elements. Ensuring strengthened resilience against hazardous climate change effects may positively facilitate diverse play activities with high play value.

Introduction

Climate change is a human driven global health challenge with a more frequent and intensified occurrence of extreme weather hazards, such as heatwaves, storms and floods, which can indirectly impact food security, air, water quality, human and animal security and health [Citation1–3]. A recent systematic review [Citation4] highlights the dire effects of climate change on global physical activity behaviours as well as the recovering and community building role of physical activity after natural disasters. Gasparri et al. [Citation5] conclude that a changed climate create severe impacts on children’s recreational opportunities. Left unconfronted, the deprivation of outdoor play possibilities will accelerate intergenerational occupational injustices and further worsen existing social inequalities [Citation6]. Consequently, it is becoming increasingly important to plan and design outdoor playgrounds with the effects of climate change in mind, as children are more vulnerable than adults to environmental extremes, such as heat, sun exposure or other thermal effects [Citation7,Citation8].

Play is the foundation of early childhood development and the possibility to play is a central and basic human need [Citation6]. It is considered a fundamental right for children [Citation9]. In the lens of child development, outdoor play activities are characterised and defined by flexibility, innovation, spontaneity, intrinsic motivation and non-literal or symbolic use of objects [Citation10,Citation11]. Outdoor play is universally recognised as vital to a healthy physical and emotional development in children [Citation12–14].

Children use increased energy levels and thereby strengthen muscle groups through movements such as climbing, running, swinging, and jumping, develop fine motor skills, as well as the ability to experiment with sensory experiences and social interactions with peers [Citation15]. These qualities are strongly manifested in unstructured play, shown in several studies to be vital for children’s healthy development [Citation11,Citation16,Citation17]. Unstructured play occupations stem from children’s initiatives, are spontaneous and without parental constraints [Citation18]. Outdoor play environments offer not only an arena for these types of playing, but also qualities considered ‘risky’ to stimulate children performing more varied and diverse play patterns with increased physical activity levels. Children’s innate attraction to risk-taking is observed in cultures worldwide, and can be characterised by mastery, the feeling of thrill, play with great heights and speed and involving dangerous elements [Citation18]. There are positive associations [Citation19–21] between engagement in risky play and children’s development, mental and physical health. The concept of ‘play value’ is used to describe the qualities experienced at an outdoor play space and how well it facilitates children’s innate developmental needs and functions. Outdoor environments promoting unstructured play offerings and diverse play patterns are usually ascribed high play value, often synonymously containing natural elements with a higher degree of flora, fauna and ecosystems [Citation22,Citation23]. Without mitigating strategies, climate change is putting these environments at risk.

Despite the benefits, previous research suggests opportunities for unstructured and risky play have diminished, increasing the risk of longer-term health issues [Citation24–26]. Concurrently, scholars have raised concerns over decreases in children’s time spent on outdoor play occupations in favour of a rise in sedentary activity patterns [Citation27–30]. Threats and increased barriers to different play enablers, such as accessible and usable outdoor playgrounds, positive socio-cultural attitudes and efforts to facilitate climate change adaptations of public outdoor playgrounds, negatively affect health and wellbeing during childhood and may even have long-term consequences [Citation7].

Affecting the entire planet, climate change results in a myriad of complex and joint consequences for all living life. The World Health Organisation [Citation31] promotes the cross-disciplinary approach ‘One Health’ with the goal of increasing health and well-being within the human-animal-environment relationships. Drawing upon the interdependencies between public health, ecosystem services stemming from nature and animal welfare, it provides a framework to describe their transactions and consequent impacts on mutually shared health outcomes. One Health has for instance been used in a study to investigate the synergies between a virus outbreak, ecosystem services and human behaviour at a natural playground [Citation32]. The approach aims to mobilise diverse sectors and stakeholders creating action for solving interconnected planetary and societal challenges, including the span of prevention and health promotion of populations. Folke et al. [Citation33] propose a holistic understanding of intertwined social-ecological systems; where the biosphere provides fundamental qualities for human and societal well-being, meanwhile ecological processes are highly influenced by human behaviour and actions. ‘Ecosystem services’ describes ecosystem functions and the subsequent benefits provided to human communities. These could be water sanative, climate regulative, disturbance regulative and cultural values, to name a few [Citation34].

Urgency and proactive measures to manage and mitigate climate change effects are called upon by scholars [Citation35,Citation36]. Society must communicate awareness of climate adaptation demands and prevent health related problems, with focus on vulnerable groups in society, such as children and their recreational needs. Extreme heat and an increasing number of hot days each year present a risk to public health [Citation37,Citation38] and heat waves will have an impact on the availability of outdoor play and activity. Some effects can be mitigated through an increase in trees and green spaces at playgrounds, hence ensuring play opportunities are maintained in the face of climate change and thereby reduce future health inequities for those living in areas more exposed to the effects of climate change [Citation35,Citation38]. Measurements using shade protection and cooling materials in Australia and China have shown an increase in visitors to playgrounds and playtime [Citation37]. Shade significantly decreased the heat stress in children playing at outdoor playgrounds, and design of the built environment can improve the microclimate through design interventions [Citation39]. The impacts of a future with more recurring heat waves, floods, humidity, wind and harmful UV radiation put the outdoor playground and children’s outdoor play in a vulnerable position [Citation40]. Veccellio et al. [Citation41] elaborate on how thermal comfort should be taken into consideration when constructing an outdoor play environment as well as designing for adaptations limiting the impact of weather extremes to ensure play and physical activity opportunities for children are possible.

According to Kennedy et al. [Citation7] environmental and ecological factors have not been fully integrated or taken into consideration in outdoor playground design. Despite the evidence [Citation42–44] for elevating nature-based play spaces as supportive for children’s risk taking and play value, it has been underprioritised in comparison with standardised safety and low maintenance design emphasising fixed play equipment, rubber surfaces and fenced grounds [Citation45,Citation46]. Working towards inclusive, resilient and sustainable cities and settlements is a priority outlined by the United Nations Agenda 2030 goals [Citation47], with universal access to green public spaces being one of the measurable targets. There is a current scientific discourse [Citation23,Citation48–52] exploring outdoor play environments and their levels of accessibility for children with disabilities. Recent studies [Citation23,Citation48–52] identify the needs and wishes for a diversity of intense play experiences similar to ‘risky’ play patterns, as well as how physical planning, equipment and social attitudes constrain and create barriers to engaging play. The literature covers the properties of natural elements in play spaces and notes their obstacles to assistive technology mobility, their provision of sensory enriching, aesthetically pleasing, unstructured play opportunities and calming qualities for children with or without disabilities [Citation23,Citation48–52].

Occupational therapy practitioners and occupational scientists have tools [Citation53–55] enacting on community health promotion and preventive health through agency and interventions concerning different environmental factors. Scholars [Citation56–59] have been stressing the linkage between planetary ecological crises and their potential harm on human occupation and activity globally, simultaneously emphasising that what humans do and the roles they live are major drivers in creating disastrous consequences for biodiversity and thriving ecosystems. Voices [Citation56,Citation58] argued the need of multifaceted solutions on preventing and managing lifestyle diseases and climate change together, for instance through lifestyle modulation or designing public health policies and environments facilitating more sustainable, just and meaningful occupational patterns. A scoping review [Citation60] used this dual intersection to study household waste sorting performed by migrants and their engagement in everyday activities. Simó Algado and Townsend [Citation58] proposed a clinical paradigm of eco-social occupational therapy, which addresses community and ecological health challenges with joint efforts and interventions. They draw upon two Spanish eco-social community interventions where individuals with long-term poverty and mental health issues were employed to reforest and restore a protected nature area, as well as an urban regreening and gardening project together with occupational therapy students. Evaluations showed increased health and well-being, a higher degree of social inclusion and an expansion of areas receiving nature restoration efforts. The occupational science concepts of ‘Ecopation’, ‘Transpersonal ecology’ [Citation61,Citation62] discusses a needed paradigm shift in the view and usage of human, societal and ecological resources for a healthy and sustainable future. The concepts argue for the experience of meaningfulness in acting responsibly for the environment now and in the future, and developing an ecopational identity through re-valuing economic growth in favour of ‘economically non-productive’ occupations that ensures human and planetary health and vitality, such as outdoor play. Assuring intergenerational occupational justices through increasing individual, community and societal ecopational action on climate change leverages the chances for future generations being able to engage in meaningful occupations.

To date, research in the field of children’s health and climate change has been centred around food supply, shelter, mental illnesses, diseases and morbidity [Citation3,Citation63,Citation64]. Research within the field of occupational science studying the transactional interactions between a changed climate, play environments and play are lacking [Citation59]. With a special focus on play value, the aim of this study was to explore the reasoning and described strategies among professionals responsible for development, planning and solutions concerning children’s outdoor playgrounds in the context of climate change.

Materials and methods

Study context

This study was carried out in the context of the Occupational Therapy programme at Lund University, Sweden. Two of the authors worked on the study as the basis for their Bachelor’s thesis, and the third author was their supervisor.

Study design

The study used semi-structured interviews and applied a qualitative inductive approach [Citation65] to identify, describe and explain data around the knowledge and planning from professionals around climate change effects and outdoor playgrounds for children. A qualitative method was deemed particularly valuable in understanding unique knowledge from a chosen group of people in a certain time [Citation66]. Semi-structured interviews with a strategically selected target group made it possible to get detailed and specific perspectives, strategic thinking, problems, future planning and ideas concerning outdoor playgrounds for children including potential climate change effects from persons involved or responsible for matters related to outdoor playgrounds.

Recruitment and interviewees

A strategic selection of the informants with a purposive sample approach was used [Citation67]. The interviewees were specifically selected based on their expertise in the area relevant to the research [Citation66]. To obtain diverse perspectives we sought input from persons with expertise within the planning and development of playgrounds and play environments for children, including researchers, architects, landscape planners, urban planners, politicians and decision makers. The inclusion criteria were to have made documented, scientific contributions to academic research in this area or to have professional experiences from planning, designing, or construction of playgrounds and play environments for children. Through unstructured and international internet research around urban planning and outdoor play environments for children, prominent potential interviewees were identified with the intent of collecting a diverse sample in terms of expertise, working roles and knowledge based on the aim of study. Twenty invitations were sent out by email to individuals identified in Australia, France, Sweden, UK and USA. Two invitations bounced back as the contact information was not accurate and ten individuals did not respond. Those eight that responded were then contacted through email or phone. In connection with this contact, they received more information about the study. After confirming that the eight individuals met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate, they signed written informed consent and were subsequently included in the study ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the eight interviewees in the study.

Ethical considerations

The guidelines from the ‘Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects’ [Citation68] were followed, and the interviewees were informed of the study, the aim and how the data would be used. To ensure confidentiality the authors made sure that the interviewees’ names were removed, as well as identifiable variables, such as workplace, profession, or any name used in the document. They were informed that they could withdraw their participation at any time. As the study did not involve any sensitive data concerning the interviewees or constituted any risk to them, it did not require formal approval from an ethical review board.

Data collection procedure

The data were collected through semi-structured interviews with the support of an interview guide to assure continuity and subject relevance. The interview guide included themes such as ‘when planning a playground in an outdoor environment with climate change in mind, what are your strategies?’ and ‘what future scenarios for tomorrow’s playgrounds regarding function and design do you consider?’. With the open and semi-structured format based on the themes, the interviewer and interviewee shaped the conversation in real time. The interview guide ensured that insights were captured in key areas while still allowing flexibility for interviewees to bring their own perspective to the discussion. The interviews were conducted with video-conference software, audio recorded and thereafter transcribed by the authors. The recording allowed the interviewer to concentrate on listening with all senses and be responsive, without being distracted by needing to write extensive notes. Trust, comfort and a professional rapport was created through allowing time for introductions. As the interviewees were selected professionals and experts in their field, it was important to have a professional and trustworthy approach in the interviews.

Data analysis

To ensure trustworthiness and systematisation of the thematic data analysis, the authors followed a meticulous methodological procedure [Citation69]. The transcribed interviews were analysed with a manifest content analysis method. The aim of the content analysis was to reduce the complexity of qualitative and textual material to identify patterns in an inductive manner [Citation70,Citation71]. Using a spreadsheet format, the data was organised into units of meaning, then coded and developed into different categories and thereafter into overarching themes. During analysis, the interviews were read through and listened to slowly several times to gain a deeper understanding of the material. To strengthen credibility, a kind of researcher triangulation was used. That is, two of the authors were first independently analysing the raw data. Thereafter, comparing the individual findings, the final themes and categories were worked out together. The research work moved back and forth from the raw material and to the findings in an iterative process [Citation67]. To further strengthen the trustworthiness peer debriefing was also used, where the emerging themes and categories were continuously reviewed and discussed with the third author.

Findings

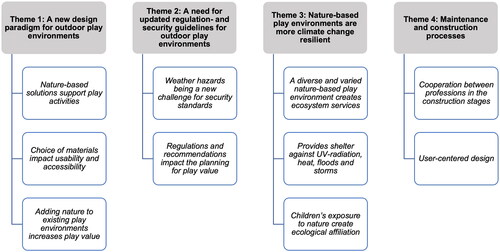

From the manifest content analysis four themes emerged with ten supporting categories (see ). Each theme is presented here with a separate section, and with the supporting categories marked in italics.

Figure 1. Themes and categories highlighting stratergies employed to mitigate the climate change effects in children’s play environments.

Theme 1: a new design paradigm for outdoor play environments

The interviewees expressed a societal need for a coordinated and well-planned adaptation of the play environments, due to a more extreme weather situation today and in the future. This was articulated as a growing design and architectural direction incorporating natural elements, and a belief that nature-based solutions support play activities through high play value. Addressing the accessibility and usability issues caused by climate change effects was advocated in this theme, along with the creation of more stimulating play environments.

The interviewees showcased experience, knowledge and a belief that children’s exposure to nature can create an increased ecological affiliation through experienced play value. Children get stimulated and inspired by nature, using their imagination, inventing new games and cooperating naturally with each other. Some of the interviewees believed that the connection children create with nature in early childhood remains throughout life and builds a care for nature and ecological understanding.

What’s so exciting is the fact that places rich in ecosystem services almost always are very rich play environments. Interview. 6 – Landscape architect

On a practical level, the way in which nature elements support unstructured play was illustrated through how the choice of materials impacts usability and accessibility. For example, increasing the number of loose materials for creative and fantasy driven play activities, constructing a varied topography to create different levels of challenges and risks, as well as channelling rainwater in accessible and usable ways for the children were often mentioned visions. An issue expressed was the current and historical view of the role of risk in play influencing the design of children’s play environments towards safer and less challenging milieus, which according to them hinders valuable experiences and development. That addressing these challenges by adding nature to existing play environments increases play value, was a recurring idea in the interviews.

Some of the interviewees were critical of the term ‘outdoor playgrounds’, for them symbolising a stale, artificial environment with low play value. Instead they preferred using terms referring to ‘play environments’. The concept of ‘Playotop’ had been co-created by a municipality and an architecture bureau, reinventing the ideas of which purposes a play environment could address; such as offering high and risky play values, exposure to nature and several ecosystem services through the implementation of different landscape types and biotopes.

Combining play value and ecosystem services we’ve divided it [Playotop] in to three different landscapes – the garden, forest and water landscapes. Interview. 2 – Municipal landscape engineer

Another recurring and mentioned feature was the role of vegetation, both as climate resistant factor and as a play facilitator. For instance, vegetation could add secludedness and safety, act as a canvas for the children in their play activities, absorb rainwater and generate loose materials. An increased biodiversity in terms of birds, mammals and insects as a result of more natural elements was seen as simultaneously leveraging play value and climate change resilience towards extreme weather hazards. This was made through adding rich flower beds for pollinators, meadows, penetrable ground materials, keeping dead wood, different grass heights and planned spaces for rainwater.

The climate is already affecting [outdoor play environments], I would say, we already have problems with heat, for example the play environments and high solar radiation, so the way we build play environments today, they are not really useful… with a lot of asphalt surfaces and rubber asphalt and far too little shade from trees and so on. Interview. 7 – Associate Professor

Theme 2: a need for updated regulation– and security guidelines for outdoor play environments

This theme concerns weather hazards being a new challenge for security standards and an expressed wish to update the regulations in governmental agency policies to include the security issues caused by climate change effects. Many past and contemporary outdoor play environment designs have been guided towards low maintenance, security over play value and narrow thinking about accessibility, which have resulted in a lack of vegetation, few trees, high use of different kinds of asphalts and a impoverished and unstimulating play environment that does not support diverse rich play occupations and mitigations of the effects coming from a changing climate. Some of the interviewees active in landscape architecture and planning criticised how the term ‘accessibility’ too often resembled mobility for children using assistive technology, and too seldomly accounted for the increasing percentage of children living with neuropsychiatric disorders. They argued against the idea and concept of making every square metre accessible for children using assistive technology for their mobility, since this inflicts on the possibilities creating different heights, natural obstacles or other risky play features. According to them regulations and recommendations impact the planning for play value. Instead, they wanted to design the outdoor play environments where all the different areas, natural elements and landscape types had points of access and options for play experiences available for children with restricted mobility. Casting light on nature’s salutogenic and recovering effects important for children with or without neuropsychiatric disorders in a heavily digitalised world, the interviewees stressed the need of increasing the green and nature-based play environments, this at the cost of a fully traversable play space for children with mobility devices.

It’s depressing to see schoolyards today that are maintenance-free and totally safe, but with no experiential value left. Interview. 6 – Landscape architect

Theme 3: nature-based play environments are more climate change resilient

Strongly emphasised by the interviewees, the third theme was inter alia about how a diverse and varied nature-based play environment creates ecosystem services and offers resilience against a changing climate and fulfils the role of creating inspiring and rich play environments for children.

Children request that it is varied and they like to have a lot of vegetation and climbing trees and exciting green environments, so they like to show the type of environment that I think has a biological diversity and which is certainly better from many climate aspects and also very popular play environments. Interview. 7 – Associate Professor

Learning from nature’s mechanisms in how to find shelter against UV radiation and heavy wind, taking care of rainwater through good quality soil, lowering the temperature, using the right kind of vegetation that can survive with little water and how a varied and rich natural setting offers ecosystem services to the local urban environment was thoroughly discussed as part of this theme.

The interviewees gave examples of their professional efforts in cooperation with different municipalities to adapt schoolyards and play environments towards more green and natural settings, in order to be more resilient towards a changing climate. They mentioned using the existing nature of the area and making it more playful with play equipment in balance with nature, adapting the schoolyard with planting more trees, removing hard surfaces and replacing them with wood chips and other material that can absorb rainwater more efficiently, emphasising the design of an area which provides shelter against UV-radiation, heat, floods and storms.

…working with submerged plantings that can handle a lot of water, trying to open up and remove hard surfaces and replace them with sand and wood chips which are permeable surfaces that can infiltrate heavy rain… Interview. 6 – Landscape architect

Intertwining the vision to provide children with natural materials, reused material and nature-based solutions as part of enriched play experiences with efforts to raise capacities and shelter against the effects of climate change was commonly discussed and used as an argument when planning new outdoor playgrounds.

… I ́m trying to work out the ways of building tree cover all the time so that the children are more dependent on playing in the trees. Interview. 4 – Playworker

It was also stated that children’s exposure to nature create ecological affiliation through contact with areas containing natural elements in children’s everyday lives. Creating behaviours that increase time and activities spent outdoors, and thereby support personal climate change adaptation strategies and capacities for a healthy and sustainable lifestyle. The interviewees connected the potential positive outcomes from a climate change adapted built environment together with a greater and more likely chance of individuals responding to demanding weather or climate through outdoor activities and thereby finding a refuge in nature. Used as an example from the interviews; a climate change adaptation response to heat waves and high temperatures could be to spend time in a local forest with shade and humidity.

Theme 4: maintenance and construction processes

The fourth theme was outlining the significance of cooperation between professions in the construction stages in ensuring the realisation and preservation of nature-based outdoor play environments.

According to the interviewees, enabling valuable play experiences not only requires thoughtful design and planning, but also requires continuous and meaningful maintenance. In general, nature-based play environments could mean a lower need of maintenance and the concept and vision from some of the interviewees were to leave the nature wild with some simple arrangements to make the space appear taken care of. For instance, showing maintenance and care through constructing a wooden fence or flowering meadows encircling a forest play environment. One issue mentioned was how to support adults accepting and understanding that a nature-based play environment changes through seasons and is not tidy and neat like a typical playground. The challenge is to convince and communicate the high play-value of loose material, nature on its own and the importance of a space always changing with the seasons and in response to use.

… it is difficult to go the whole way with play environments, you have to convince the designer, the project leader, the constructor and the builder and the maintenance. There are so many people involved and everyone need to have the same goal. Interview. 6 – Landscape architect

Cooperation between professions in the construction stages was a key factor identified by the playground professionals in the study. They reflected on the matter that sometimes it was the organisation with many people involved that made it difficult to implement new ideas and reach new goals not tested before. Discussing and reaching consensus regarding concepts of what playgrounds or play environments can look like and their function offered to society were vital in enabling a new design paradigm for outdoor play environments. To innovate successfully, there was a need for effective collaboration through different units, shared goals and constructive attitudes.

Another important factor highlighted in the interviews was the importance of the early stages of collaborating and engaging different stakeholders, in order to implement new ideas for outdoor play environments. A user-centred design involving children with different needs as the users of the playground, together with designers, architects, constructors, builders and maintenance technicians could be a model for creating a baseline when constructing play spaces with new ideas and planning incorporating qualities increasing accessibility, usability, climate change adaptation while simultaneously offering high play value.

Our idea is to involve everybody and also children because they really are keen on doing things useful for the school yard and being involved in the maintenance, so we are trying to involve them. Interview 3. – Project manager for municipal climate adaptation of school grounds

Discussion

Exploring the reasoning and strategies among professionals dealing with children’s outdoor playgrounds in the context of climate change, the findings illustrate how climate change adaptation strategies for outdoor play spaces using more natural elements have the potential of increasing community resilience as well as increasing play value and the possibilities for risky play. The interviewees showcased an overall awareness of the risks climate change pose for outdoor playing environments and a demonstrated desire to use innovative and nature-based strategies and planning to deal with these risks. The current study also highlights how adapting new strategies can result in attractive, inviting and inclusive playing environments, thereby promoting children’s health.

A main finding of the current study was that it highlighted a new design paradigm of outdoor play environments with more vegetation, natural elements and biodiversity to increase play value, children’s health, and protection against climate change effects. For instance, as a strategy to mitigate climate effects the natural elements of an existing nature such as trees, bushes, stones, tree trunks and hills can be maintained as it adds value and ecosystem services when planning new outdoor play environments. Natural and reused material from other projects can also be used as valuable resources when creating or adapting outdoor playgrounds. Though it is new as a design paradigm, the links between nature, climate change adaptation measures and play value are supported by previous research [Citation41,Citation72,Citation73].

Risky and unstructured play was often highlighted by the interviewees in the study as important to children’s development and underpinning children’s self-confidence, ability to solve problems and the awareness of their physical body and promoting motor skills. Risky play is a natural part of children’s engagement with nature as they jump over trunks, from stone to stone or climb trees; a valuable expression of play as it inspires engagement, discovery, problem solving and sensory experiences. The findings along with previous research acknowledge the importance of offering an environment with risky elements, since it attracts and prolongs the stay of children [Citation11,Citation22,Citation23,Citation44,Citation45].

Importantly, strategies promoting nature-based environments as more climate change resilient are augmented by the current study. For instance, more trees provide shade against the sun, protect against heavy rain and the use of vegetation lowers the temperature. Natural materials can absorb water better, giving strength to the idea of designing and facilitating in the highest means possible self-regulating ecosystem services providing shelter against a variety of hazards. Equipping a landscape with ways of channelling large amounts of rainwater through permeable surfaces, variations in vegetation and dam-like areas, providing shade and natural cooling from trees and vegetation and fostering populations of different insects and bird species through preserving dead wood, meadows, flower beds and fruit trees, contributing to biodiversity are measures increasing resilience [Citation34,Citation73,Citation74]. Seen from the ‘One Health’ approach efforts to increase the levels of ecosystems and biodiversity in human settlements are both positive and negative from a public health point of view; with providing sanctuaries for flora, fauna and the promotion of healthy occupations, simultaneously risking eventual zoonotic virus outbreaks [Citation31,Citation32].The study results covering the importance of design choices incorporating the local climate, solar angles, materials of play facilities, biodiversity, water resources and other environmental factors is supported by previous scholarly work [Citation41,Citation73]. Planning the play environment for the local setting and future climate scenarios will benefit both the costs and an increased resilience towards the impact of climate change, thus increasing its attraction and sheltering functions for children and communities.

The results lift opinions voicing tension between realising a climate change resilient play environment with high play value and abiding to current building regulations assuring accessibility everywhere for children with mobility or orientation difficulties. Building regulations can be seen as depriving outdoor play environments of unstructured and risky play opportunities, inflicting on their ambitions to design a palette of different heights, sensory stimulation, natural obstacles and ecosystem services facilitating play value and climate change adaptation efforts, assuring that some of these qualities were accessible for children using mobility devices. Horton [Citation52] published a qualitative study investigating the accessibility for children with disabilities in nature-based outdoor playgrounds in England. Parents to these children were expressing sadness, experienced mobility barriers hindering joyful play experiences and dread associated with visiting the two nature-based playgrounds mentioned in the study. In the existing scientific discourse [Citation23,Citation47–52] covering nature-based outdoor play environments and the accessibility for children with disabilities, research emphasise both play barriers and enablers. Barriers to play can result from restricted mobility, meanwhile the possibilities for unstructured and risky play and sensory stimulation were emphasised as positives. One argumentation and example used by both the interviewees and literature [Citation23,Citation51] is when play occupations are done with loose natural materials instead of being centred around premade play equipment, this increases the play value for children with or without disabilities. A common knowledge gap found [Citation22,Citation47–52] within the literature is to empirically map how children with disabilities interact with nature-based play environments and identify enablers or barriers to accessible play experiences for this group.

Overall, the findings of the present study amplify the idea that nature promotes play, underpinned by previous research showing the benefits of outdoor play and in nature [Citation11,Citation19,Citation23,Citation42,Citation43]. Suggested by the findings, developing a more cost-efficient, ecologically diverse and high play value outdoor play environment can offer access to nature for children in urban areas, as well as shielding the local community from future climate hazards. Failing to assure climate change resistant spaces for children to play results in occupational deprivation, occupational injustices and deepens existing social inequalities [Citation6].

The relationship between offering children’s exposure to nature and the creation of an ‘ecological attachment’ through doing, engaging in ecopation [Citation61] and playing in environments with natural elements may potentially increase the respect for nature, enhance the feeling of vitality and offer knowledge about nature and ecosystem services. Drawing upon previous research [Citation75–77] and the findings of the present study, creating the chance for children to establish a relationship with nature and view it as a sanctuary may result in children achieving better health and well-being. More research to study the development of ecopational identities and ecopations from a child perspective is therefore warranted, since this theory is predominantly based on adults.

Methodological considerations

Orienting the interview material with an inductive approach has created flexibility, adjustability and openness in ensuring transparency into how the interview material corresponds to the resulting themes and categories. Additionally, choosing a manifest direction of the content analysis enabled to better spotlight and specify the different strategies and design decisions implemented in practice. Regarding limitations, the study’s findings were likely strongly partial by the included sample. Recruiting each of them was based on their prolific engagement in children’s outdoor play, nature-based landscape architecture and urban climate change adaptation. Considering the limited study resources and time connected with the context of a bachelor’s thesis, the sample became rather narrow. Interviewees were primarily found among those actively promoting their work at conferences and thereby their reasoning and choice of strategies were accessible to the authors beforehand. If a different approach to interviewee sampling was adopted, for instance, through a randomised sample of landscape architects and urban planners drawn from across Sweden or Europe, the findings would probably have been more reflective of diverse perspectives and practices. Not having representatives and the perspectives from urban planning and policy makers meant the study lacked the complexity arising from roles responsible for mitigating and balancing a wide array of, sometimes conflicting, priorities in the light of urban development.

Conclusions and significance

The findings of the present study suggest that the reasonings and strategies employed by practitioners and researchers concerned with climate change effects and children’s play in outdoor environments are leaned towards the implementation of increased ecosystem services, natural elements and landscape types mimicking nature. Achieving and ensuring strengthened resilience against hazardous climate change effects through these methods may positively facilitate play value resulting in diverse patterns of play activities and proactively support the possibilities to play in a future, where the conditions undoubtedly will differ compared to today. There is an ongoing growth in the literature investigating the negative health effects on children triggered by the many complex societal and individual effects caused by climate change, however seldomly pointing out the risks for deprivation concerning engagement in meaningful activities for children. The current study highlights how the planning for assuring outdoor play in the future can result in attractive, inviting and inclusive play environments today, thereby generating many positive health spirals for children in their daily lives.

Implications for occupational therapy and occupational science practitioners include the need to advocate locally and nationally to adapt or re-design existing play environments and design new ones using nature-based solutions. This type of advocacy will likely protect everyday outdoor play opportunities and strengthen occupational justice for children. Moreover, the findings of the present study could act as inspiration to offer children needing occupational therapy services access to nature for their development and well-being.

Further research is needed to investigate how climate change adaptation strategies can enable or disable assistive technology mobility at nature-based play environments, how the health benefits and mechanisms of play in rich and varied natural settings can be understood for different groups of children. Lastly, studying how the factors concerning organisation and planning related to implementation of nature-based outdoor play environments may be optimised would be in favour of a healthier and more sustainable future.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely want to thank the study interviewees for their shared time and insights, as well as Professor Emeritus Torbjörn Falkmer at Curtin University for his excellent feedback and perspectives during the manuscript writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Boylan S, Beyer K, Schlosberg D, et al. A conceptual framework for climate change, health and wellbeing in NSW, Australia. Public Health Res Pract. 2018;28(4):2841826.

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022 – impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book.

- Helldén D, Andersson C, Nilsson M, et al. Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(3):164–175.

- Bernard P, Chevance G, Kingsbury C, et al. Climate change, physical activity and sport: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2021;51(5):1041–1059. doi: 10.1007/s40279-021-01439-4.

- Gasparri G, Omrani OE, Hinton R, et al. Children, adolescents, and youth pioneering a human rights-based approach to climate change. Health Hum Rights. 2021;23(2):95–108.

- Drolet M-J, Désormeaux-Moreau M, Soubeyran M, et al. Intergenerational occupational justice: ethically reflecting on climate crisis. J Occup Sci. 2020;27:1–15.

- Kennedy E, Olsen H, Vanos J, et al. Reimagining spaces where children play: developing guidance for thermally comfortable playgrounds in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2021;112(4):706–713. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00522-7.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities. Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2022-impacts-adaptation-and-vulnerability/health-wellbeing-and-the-changing-structure-of-communities/5A5E7494BDF8228C0842B079107A85C4.

- United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Comment No. 17 (2013) on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life and the Arts (Art. 31). New York (NY); 2013 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9bcc4.html

- Fagen RM. Play and development. In: Pellegrini AD, editor. The Oxford Handbook of the Development of Play. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. p. 83–101.

- Herrington S, Brussoni M. Beyond physical activity: the importance of play and nature-based play spaces for children’s health and development. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(4):477–483. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0179-2.

- Dowdell K, Gray T, Malone K. Nature and its influence on children’s outdoor play. J Outdoor Environ Educ. 2011;15(2):24–35. doi: 10.1007/BF03400925.

- Gill T. The benefits of children’s engagement with nature: a systematic literature review. Child. Youth Environ. 2014;24(2):10–34. doi: 10.1353/cye.2014.0024.

- Van Dijk-Wesselius JE, Maas J, Hovinga D, et al. The impact of greening schoolyards on the appreciation, and physical, cognitive and social-emotional well-being of schoolchildren: a prospective intervention study. Landsc Urban Plan. 2018;180:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.08.003.

- Bento G, Dias G. The importance of outdoor play for young children’s healthy development. Porto Biomed J. 2017;2(5):157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.pbj.2017.03.003.

- Colliver Y, Harrison LJ, Brown JE, et al. Free play predicts self-regulation years later: longitudinal evidence from a large Australian sample of toddlers and preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. 2022;59:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.11.011.

- Lee RLT, Lane S, Brown G, et al. Systematic review of the impact of unstructured play interventions to improve young children’s physical, social, and emotional wellbeing. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22(2):184–196. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12732.

- Hansen Sandseter EB. Categorising risky play—how can we identify risk‐taking in children’s play? Eur Early Child Educ. 2007;15(2):237–252. doi: 10.1080/13502930701321733.

- Dankiw KA, Tsiros MD, Baldock KL, et al. The impacts of unstructured nature play on health in early childhood development: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229006.

- Brussoni M, Olsen LL, Pike I, et al. Risky play and children’s safety: balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(9):3134–3148. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9093134.

- Hansen Sandseter EB, Kleppe R, Ottesen Kennair LE. Risky play in children’s emotion regulation, social functioning, and physical health: an evolutionary approach. Int J Play. 2023;12(1):127–139. doi: 10.1080/21594937.2022.2152531.

- Woolley H, Lowe A. Exploring the relationship between design approach and play value of outdoor play spaces. Landsc. Res. 2013;38(1):53–74. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2011.640432.

- Morgenthaler T, Schulze C, Pentland D, et al. Environmental qualities that enhance outdoor play in community playgrounds from the perspective of children with and without disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):1763. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031763.

- Gray P. The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Am J Play. 2011;3(4):443–463.

- Lee H, Tamminen KA, Clark AM, et al. A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children’s independent active free play. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0165-9.

- Pynn S, Neely K, Ingstrup M, et al. An intergenerational qualitative study of the good parenting ideal and active free play during Middle childhood. Child Geogr. 2018;17:1–12.

- Kemple KM, Oh J, Kenney E, et al. The power of outdoor play and play in natural environments. Child Educ. 2016;92(6):446–454. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2016.1251793.

- de Bruijn AGM, Te Wierike SCM, Mombarg R. Trends in and relations between children’s health-related behaviors pre-, mid- and post-Covid. Eur J Public Health. 2023;33(2):196–201. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckad007.

- Munsamy AJ, Chetty V, Ramlall S. Screen-based behaviour in children is more than meets the eye. S Afr Fam Pract. 2004;64(1):1–4.

- Nigg C, Niessner C, Nigg CR, et al. Relating outdoor play to sedentary behavior and physical activity in youth – results from a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1716. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11754-0.

- World Health Organization. A health perspective on the role of the environment in One Health [Internet]. Copenhagen: Regional Office for Europé; 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 13]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354574/WHO-EURO-2022-5290-45054-64214-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Sips GJ, Dirven MJG, Donkervoort JT, et al. Norovirus outbreak in a natural playground: a one health approach. Zoonoses Public Health. 2020;67(4):453–459. doi: 10.1111/zph.12689.

- Folke C, Biggs R, Norström AV, et al. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecol Soc. 2016;21:3.

- Costanza R, d’Arge R, de Groot R, et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 1997;387(6630):253–260. doi: 10.1038/387253a0.

- Campbell-Lendrum D, Corvalán C. Climate change and developing-country cities: implications for environmental health and equity. J Urban Health. 2007;84(3 Suppl):i109–i117. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9170-x.

- Tarpani E, Pigliautile I, Pisello AL. On kids’ environmental wellbeing and their access to nature in urban heat islands: hyperlocal microclimate analysis via surveys, modelling, and wearable sensing in urban playgrounds. Urban Clim. 2023;49:101447. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2023.101447.

- Pfautsch S, Wujeska-Klause A, Walters J. Outdoor playgrounds and climate change: importance of surface materials and shade to extend play time and prevent burn injuries. Build Environ. 2022;223:109500. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109500.

- Lanza K, Alcazar M, Hoelscher DM, et al. Effects of trees, gardens, and nature trails on heat index and child health: design and methods of the green schoolyards project. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10128-2.

- Vanos JK, Herdt AJ, Lochbaum MR. Effects of physical activity and shade on the heat balance and thermal perceptions of children in a playground microclimate. Build Environ. 2017;126:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.09.026.

- Vanos JK. Children’s health and vulnerability in outdoor microclimates: a comprehensive review. Environ Int. 2015;76:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.016.

- Vecellio DJ, Vanos JK, Kennedy E, et al. An expert assessment on playspace designs and thermal environments in a Canadian context. Urban Clim. 2022;44:101235. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2022.101235.

- Wishart L, Cabezas-Benalcázar C, Morrissey AM, et al. Traditional versus naturalized design: a comparison of affordances and physical activity in two preschool playscapes. Landsc. Res. 2019;44(8):1031–1049. doi: 10.1080/01426397.2018.1551524.

- Loebach J, Cox A. Playing in ‘the backyard’: environmental features and conditions of a natural playspace which support diverse outdoor play activities among younger children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):12661. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912661.

- Little H, Eager D. Risk, challenge and safety: implications for play quality and playground design. Eur Early Child Educ. 2010;18(4):497–513. doi: 10.1080/1350293X.2010.525949.

- Woolley H. Watch this space! designing for children’s play in public open spaces: watch this space. Geogr Compass. 2008;2(2):495–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00077.x.

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: special edition. New York: United Nations Statistics Division Development Data and Outreach Branch; 2023 July. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023.pdf

- Gately KA, Zawadzki AH, Mosley AM, et al. Occupational injustice and the right to play: a systematic review of accessible playgrounds for children With disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 2023;77(2):7702205040. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2023.050035.

- Movahed M, Martial L, Poldma T, et al. Promoting health through accessible public playgrounds. Children (Basel). 2023;10(8):1308. Jul 29doi: 10.3390/children10081308.

- Dalpra M. Rethinking play environments for social inclusion in our communities. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022;297:218–225. doi: 10.3233/SHTI220842.

- Moore A, Lynch H, Boyle B. Can universal design support outdoor play, social participation, and inclusion in public playgrounds? A scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(13):3304–3325. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1858353.

- Cosco N, Moore R. Creating inclusive naturalized outdoor play environments. [cited 2003 Oct 9]. Available online https://www.childencyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/creating-inclusive-naturalized-outdoor-play-environments.

- Horton J. Disabilities, urban natures and children’s outdoor play. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017;18(8):1152–1174. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1245772.

- Estrany-Munar MF, Talavera-Valverde MÁ, Souto-Gómez AI, et al. The effectiveness of community occupational therapy interventions: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3142. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063142.

- Sakellariou D, Pollard N, editors. Occupational therapies without borders: integrating justice with practice. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2017.

- Rigby P, Huggins L. Enabling young children to play by creating supportive environments. In Letts L, Rigby P, Stewart D, editors. Using environments to enable occupational performance. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 2003, p. 155–177.

- Garcia Diaz LV, Richardson J. Occupational therapy’s contributions to combating climate change and lifestyle diseases. Scand J Occup Ther. 2023;30(7):992–999. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2021.1989484.

- Ikiugu M, McCollister L. An occupation-based framework for changing human occupational behavior to address critical global issues. Int J Prof Pract. 2011;2:402–417.

- Simó Algado S, Ann Townsend E. Eco-social occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(3):182–186. doi: 10.1177/0308022614561239.

- Lieb LC. Occupation and environmental sustainability: a scoping review. J Occup Sci. 2022;29(4):505–528. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2020.1830840.

- Hellwig C, Häggblom-Kronlöf G, Bolton K, et al. Household waste sorting and engagement in everyday life occupations after migration—a scoping review. Sustainability. 2019;11(17):4701. doi: 10.3390/su11174701.

- Persson D, Erlandsson L-K. Ecopation: connecting sustainability, glocalisation and well-being. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(1):12–24. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.867561.

- Do Rozario L. Shifting paradigms: the transpersonal dimensions of ecology and occupation. J Occup Sci. 1997;4(3):112–118. doi: 10.1080/14427591.1997.9686427.

- Clemens V, von Hirschhausen E, Fegert JM. Report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change: implications for the mental health policy of children and adolescents in Europe-a scoping review. Eur Child Adolesc Psych. 2022;31(5):701–713. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01615-3.

- Sheffield PE, Landrigan PJ. Global climate change and children’s health: threats and strategies for prevention. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(3):291–298. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002233.

- Liu L. Using generic inductive approach in qualitative educational research: a case study analysis. JEL. 2016;5(2):129. doi: 10.5539/jel.v5n2p129.

- Lysack C, Luborsky MR, Dillaway H. Gathering qualitative data. In: Kielhofner G, editor. Research in occupational therapy: methods of inquiry for enhancing practice. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 2006, pp. 341–357.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2014.

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):160940691773384. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Dooley KJ. Using manifest content analysis in purchasing and supply management research. J Purch Supply Manag. 2016;22(4):244–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pursup.2016.08.004.

- Kleinheksel AJ, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, et al. Demystifying content analysis. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(1):7113. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7113.

- Bohnert AM, Nicholson LM, Mertz L, et al. Green schoolyard renovations in low-income urban neighborhoods: benefits to students, schools, and the surrounding community. Am J Community Psychol. 2022;69(3-4):463–473. Jundoi: 10.1002/ajcp.12559.

- Olsen H, Kennedy E, Vanos J. Shade provision in public playgrounds for thermal safety and sun protection: a case study across 100 play spaces in the United States. Landsc Urban Plan. 2019;189:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.04.003.

- Frantzeskaki N, McPhearson T, Collier MJ, et al. Nature-Based solutions for urban climate change adaptation: linking science, policy, and practice communities for evidence-based decision-making. BioScience. 2019;69(6):455–466. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz042.

- Li H, Browning MHEM, Cao Y, et al. From childhood residential green space to adult mental wellbeing: a pathway analysis among chinese adults. Behav Sci. 2022;12(3):84. doi: 10.3390/bs12030084.

- Engemann K, Pedersen CB, Arge L, et al. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(11):5188–5193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807504116.

- Mitchell R, Popham F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61689-X.