Abstract

Background

Few studies synthesising knowledge about meaningful occupation are available. Meta-ethnography allows the synthesising of a variety of empirical findings and translational knowledge may be developed.

Aim

Investigate how individuals from diverse cultures and contexts experience meaningful occupation as described in qualitative research, applying meta-ethnographic approach.

Material and methods

The study was based on 44 qualitative articles, selected by following a systematic procedure. Articles published between 2003-2021 were included. Studies on children, intervention and review articles were excluded. All authors conducted the analysis and synthesis, in several steps, and reached a consensus interpretation of the data.

Results

Five categories explaining why and how people experienced meaning emerged. They were represented in all contextual settings. The main category was 1) Constructing identity and self-actualising throughout life. The other four categories were 2) Cultivating valued feelings 3) Spiritualising by being energised or disentangled 4) Connecting and belonging 5) Rhythmizing and stabilising by being occupied.

Conclusion and significance

The synthesis provided novel insights into how people experience meaning in occupation in various contexts as part of their process of constructing identity and self-actualisation throughout life. This knowledge is valuable as expanding and nuancing the understanding of meaningful occupation.

Keywords:

Introduction

All over the world studies exploring meaningful occupation have been carried out among different populations in different settings using different methodologies and designs. This meta-ethnography is an attempt to gain an overall macro-level vision of peoples’ experiences of meaningful occupation across populations and contexts. The concept of meaningful occupation is defined from many perspectives, which is an important consideration when incorporating empirical studies from a multitude of populations and contexts into a synthesis. The main perspective is occupational therapy/occupational science, which is complemented with research on the experience of meaning from existential/individual, group and anthropological perspectives.

Occupational therapy/occupational science perspective

Research into experiences of meaningful occupation was revived and expanded within the fields of occupational therapy and occupational science development in the 1990s. Elizabeth Yerxa [Citation1], Zemke and Clark [Citation2] and Clark [Citation3] then highlighted the concept of meaning and the importance of experiencing meaning in the occupations of daily lives. Setting goals as well as planning for successful occupational interventions for clients relied on identifying meaningful occupations for their clients. The occupational therapy paradigm had changed focus at this point as well from a more functional and medicalized view to a more humanistic and social viewpoint i.e. back to the roots of the profession.

Occupation

The World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT) defined occupation to everyday activities that people do as individuals, in families and with communities to occupy time and bring meaning and purpose to life [Citation4]. Pierce [Citation5] defined occupation as a specific individual’s personally constructed, nonrepeatable experience in the occupation. That is, an occupation is a subjective event in perceived temporal, spatial, and sociocultural conditions that are unique to that one-time occurrence. The individual can perform the occupation again, however now with new experiences. An occupation has a shape, a pace, a beginning, and an ending, a shared or solitary aspect, a cultural meaning to the person, and an infinite number of other perceived contextual qualities [Citation5, p. 4–5].

Meaning

In the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance [Citation6] meaning is related to the individual’s spirituality, which is in turn imperative for the person’s drive to be occupied [Citation7]. To be motivated in for example a rehabilitation process has a great impact on how successful the rehabilitation will be, by achieving goals. Meaningful occupations to the specific individual are important. Wilcock [Citation8] described the dimensions of doing, being, becoming as capturing meaning experiences when performing occupations. Rebeiro et al. [Citation9] and Hammell [Citation10] added the dimension of belonging as a necessary contribution of social interaction. Belonging also included experiences of mutual support, inclusion and friendship that gave one’s life value for others as well as for oneself. These four dimensions of occupation and their relation to the experience of meaning served as a lens and pre-understanding by the authors when we started the present study. The four dimensions has been further elaborated by Hitch et al. [Citation11,Citation12] and will be described more in detail below. The KAWA model [Citation13] gives another view of understanding meaningful occupation symbolised as a river, life-flow and hinders along our life. Thus, experiences of meaningful occupation is existential, biographical, dynamic and socio-culturally bound to time and place” [Citation14].

Existential and individual perspective

Experiences of meaning in occupations is dynamic and become to be like a compass and a drive guiding individuals to make new occupational choices for the future. Which occupations one finds meaningful is dependent on who one is, what one wants to accomplish and together with whom [Citation14–16]. What one finds meaningful to do is also dependent on human needs and development. Existentialism, based on the theories of Kierkegaard described the struggles of finding one’s true self and the meaning in life [Citation17–19] while investigating what it means to be human. A need for personal development often begins with questions or a discomforting feeling; – Why am I here? – What do I want? – Who am I? – What should I do now?

This is in line with occupational therapy theory described by Jonsson and Josephsson [Citation7] who stated that meaningful occupation is constructed by both existential and socio-cultural influences in life. Another perspective outside OS/OT is Tornstam [Citation20] who described, in line with existentialism, the theory of gerotranscendence. The theory described a developmental pattern beyond the old dualism of activity and disengagement that gave new insights about meaningful occupation throughout life. Older individuals are, for example, more selective concerning activities and social interaction, reflect over life, and redefine the Self. Perspectives of meaning and becoming change from highly individual concerns into belonging in a much broader and existential way. The theory is in line with the view of people being able to transform especially in crises or having a severe disability [Citation21].

Doing and being [Citation10,Citation22], are dimensions of occupation within occupational therapy for the promotion of wellbeing. Hitch and co-authors [Citation12] described the dimension doing as the medium for occupational engagement, skills, abilities, active engagement, and that people are able to adapt their doing over time. Being is the essence of existing, an occupational being striving for self-discovery including meanings in life, and expressed in, for example, reflection, creativity, identity and roles [Citation23]. Another dimension, becoming, reflects the process of development and growth and is often directed by aspirations and the goals in life (on individual/group/societal levels), targeting the fourth dimension of belonging as previous described by Rebeiro et al. [Citation9]. Hitch, Pepin and Stagnatti [Citation12] have recently described these dimensions of occupation in the POP (Pan Occupational Paradigm) model, as crucial in guiding practice in change processes and adapting to new circumstances. Doing, being and becoming also often used for explaining individually perceived meaning in occupation, have also been shown to explain several developmental processes and processes in learning and education [Citation24].

Concerning biological conditions and resources for experiencing meaningful occupation, Ikiugu [Citation25] found that occupations that contribute to and facilitate rewarding experiences for individuals such as eating, sex, sleep, social inclusion are often perceived as meaningful and motivational. Psychologically rewarding and meaningful occupations have also shown to be quite similar in that they were both physically stimulating [Citation26]. Personality and different preferences also affect which occupations individuals chose and find meaningful, for example, if you are predominantly introvert or extrovert. Knowledge from an existential perspective and individual paths in life are thus very important when trying to understand meaningful occupations among the individuals we meet and work with as occupational therapists. Their stories are often told as narratives of individual life trajectories [Citation3,Citation22].

Group perspective

The second perspective could be described as a group perspective, focusing different groups of individuals and their experienced meaning in occupation. Meaning in occupation has been studied in many different populations, as for example people with depression, cancer, living as homeless, or by focusing on people of a certain age-group or living situation such as having work or not working etc. This research generates a better understanding of the specific group and their perceived meaning in daily occupations and is important since it contributes to client-centred practice and an understanding of the individuals’ meaning in occupations and effects on their well-being [Citation23,Citation27,Citation28]. The groups studied have most often at least one common factor and the knowledge is often applied into practice in intervention programmes. Some examples of this type of study are for example people with psychiatric disability [Citation29,Citation30], being a working mother [Citation31], being an asylum seeker [Citation32] or by focusing on a certain age period [Citation33]. The knowledge base supports occupational therapy in developing programs and guidelines for intervention with a focus on specific groups or populations.

Anthropological perspective

Anthropology and occupational therapy share the interest in having a holistic approach to understanding meaning in what humans do in their lives taking the context, cultures, and societies into account [Citation34]. The third perspective could therefore be described as an anthropological perspective inheriting both OS/OT as well as other theories. This entails studying the meaning in human activities and behaviour in different socio-cultural contexts [Citation35]. Meaning has also been described as socially constituted, created through the dynamic interaction with others [Citation7,Citation36]. Iwama [Citation13,Citation37] framed the cultural contexts as situated meanings, which means that people create meaning within their socio-cultural context that can be viewed as shared dimensions of meaning such as norms, behaviours, religious values, and arts. The concept of belonging [Citation9] is very much in line with how meaning is situated from an anthropological perspective. Belonging was defined as the necessary contribution of social interaction, support and friendship, the feeling of inclusion and that one’s life has value for others as well as for oneself. Meaning in occupation is thus partially socially constructed and some occupations are shared in terms of meaning within a certain culture (or subculture) [Citation13,Citation38]. Meaningful occupations occur in time and space as part of the environment and relate time and space to the experience of occupation, also reflecting place i.e. our “occupation-spaciality” [Citation39]. Time and ageing were investigated within the field of anthropological research [Citation40], where “elderscapes” (pp. 3) were outlined, describing the spatio-temporal aspect of ageing, the uncertain shifting terrain, different circumstances, ideas, and norms shifting along life for individuals and their change of meaning. Experiences of meaning in time and space are thus part of our autobiographical story about meaningful occupations, in the light of the past, the present and the future.

Research about meaningful occupation should not exclusively be based on white middle-class and western countries as the norm, it should preferably focus on richness and diversity, and be culturally relevant for populations across the world [Citation41–44]. Gaining meaningful occupations in life will probably change in the future due to climate changes and other crisis [Citation45]. Synthesised knowledge about experiences of meaningful occupation could therefore guide occupational therapists in enabling meaningful occupations for people in life changing events both on an individual- and group level in different socio-cultural context.

Knowledge from the existential-individual, group and anthropology perspectives as well as research from OS/OT about meaningful occupation form the pre-understanding of meaningful occupation in the present meta-ethnographic study.

Synthesising research

It is essential for researchers to synthesise valuable findings about an important subject within their profession, thereby avoiding knowledge formation in isolated islands or repeatedly producing one-shot research reinventing the wheel [Citation46]. Synthesising provides opportunities to discover the connections between findings and the possible theory development and understanding that could be ynthesized [Citation47,Citation48], in this case of the experience of meaningful occupation. Few efforts have been made to synthesise studies and compile the findings of qualitative research on meaningful occupation in both occupational therapy and occupational science. Focusing on qualitative research can help us develop a deeper understanding of the experiences in occupation, define concepts and develop theoretical models that could guide clinical practice in occupational therapy. This knowledge is critical to client-centred practice [Citation49]. One meta-synthesis has been found concerning meaningful occupation in occupational science [Citation50] and the results showed that there is evidence of the link between engagement in meaningful occupation and having a sense of personal and social well-being. However, the articles in the mentioned meta-synthesis were mainly focused on occupational science and an analysis performed on theme descriptions. A study using a more extensive search strategy while also considering the context and different life situations when synthesized experiences of meaningful occupation is thus needed. Meta-ethnographies facilitate a higher analytical understanding of human experiences and highlight the different, as well as common, dimensions of meaning in occupation across cultures and contexts [Citation51]. The synthesized knowledge discovered could be used to do ethnographic generalisations by producing narratives or theoretical combinations of the topic.

Thus, the rationale for the present study is to provide synthesized knowledge about experiences of meaningful occupation based on qualitative empirical research performed in diverse populations in a variety of socio-cultural contexts. The knowledge could guide occupational therapy practice in both understanding the characteristics of how and why people experience meaning as well as providing knowledge for further theory development and implications for interventions.

Aim

Investigate how individuals from diverse cultures and contexts experience meaningful occupation as described in empirical qualitative OT and OS research by applying a meta-ethnographic approach.

Method

Qualitative meta-ethnography

The meta-ethnography approach used in this study was based on the method described by Noblit and Hare [Citation51] in combination with suggested guidelines by Paterson, Thorne, Canam and Jillings [Citation52]. Noblit and Hare [Citation51] described meta-ethnography as putting together research focusing the interpretative explanations of qualitative studies into another. The analyst is always translating studies into his own world view when analysing qualitative studies and the product will always be a product of the synthesizer/synthesizers. The unique nature of a meta-ethnography compared to meta-analysis is the translation theory of social explanation. Basically, the research process consists of the following procedure (a) Selection of focus of meta-ethnography, i.e. the aim (b) Search strategy, retrieval, and assessment of primary research to determine rigour (c) Outcome of study selection c) Meta-analysis (d) Analysis and synthesis (e) Reporting outcome of synthesis process [Citation52,Citation53]. The study was registered in Prospero in 2020 (CRD42019135666) at the commencement of the data search.

Search strategy, retrieval, and rigour of primary research

The initial procedure for conducting the meta-ethnography involved determining which studies were to be included. This was based on research concerning the phenomenon, event or experiences described in the aim of our study [Citation53]. The search procedure, aiming to find relevant articles, started with identifying research by selecting the databases together with a professional librarian, the databases selected were: Cochrane, PubMed, Psych Info and CINAHL. The search terms were: Meaning OR meaningful OR meaningfulness OR (AND purposeful, in the first step) in combinations with AND occupation/daily occupation/everyday occupation, AND Activity, as in the second step using Occupational Therapy AND Occupational Science. A test search based on the search terms mentioned was performed by a professional librarian and 50 articles were extricated from the test search by the librarian and given to the first author who read the 50 abstracts and discussed further optimal search strategies and inclusion criteria with the librarian. The search strategy was then refined, and the total search performed by the librarian ended up with 808 articles, after duplications were removed. The inclusion criteria used were: Academic journals in English published 2003 to the spring 2019 and only qualitative empirical studies. An additional search in the same manner was performed 2019–2021 to update and complement the search and one further study was found [Citation8], which was not applicable for our selection. The search thus included articles published between 2003–2021. In the third step (see ), the first author read the 808 abstracts based on the following exclusion criteria: review articles, articles focusing children up to 18 years old, articles not focusing the same phenomenon as the aim of the study, intervention studies, non-empirical studies, studies focusing experiences among professionals and articles with quantitative, mixed or focus group study designs This selection procedure resulted in 107 articles remaining in the search process for the next step.

Figure 1. Flow chart of search strategy and search result following the steps in PRISMA [Citation54].

![Figure 1. Flow chart of search strategy and search result following the steps in PRISMA [Citation54].](/cms/asset/046e6735-9272-4b01-b161-a7158f593e12/iocc_a_2294751_f0001_c.jpg)

Determining rigour

The APA standards for qualitative research [Citation55] were used in Step Four of the selection procedure to determine the rigour of the 107 articles together with the exclusion criteria in Step three in case anything had been unclear in the abstracts that had previously been read. Firstly, the authors made a control for that the article focused the same phenomena as intended in the aim of this study, otherwise they were excluded (for example that the concept meaning only referred to the methods used like phenomenology and IPA). Further, the research questions, method section, ethical approval, findings and discussion were assessed concerning clarity and transparence. Articles not fulfilling the criteria of APA standards [Citation55] were excluded. This rigour process was performed by the first and last author.

Outcome of selection procedure

A flow diagram inspired by Moher Liberati & Tetzlaff ‘s [Citation54] PRISMA show the steps taken and the search strategies applied (see ). The outcome of the selection procedure resulted in 44 selected articles that fulfilled the criteria. The articles are described in (see ).

Table 1. Study characteristics of the selected articles for analysis (n = 44).

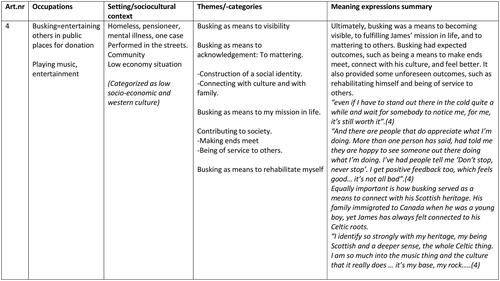

Analysis and synthesis

After the decision about which articles to include in the study, the first and last authors firstly followed the guidelines of Noblit and Hare [Citation51] and read the studies repeatedly with great attention to the details in the accounts concerning how the meaning in occupation was described, how it was experienced, in which occupational settings, the described themes and categories and important content and quotes were noted (i.e. both first level and second level interpretations). We also scrutinised our reading and divided the use of meaning expressed as attached to occupation and when it was attached to the method described, such as phenomenology etc. The sociocultural context within the studies was identified and all the noted data was structured in an overarching table, called a master table by the authors, where all the noted data illustrating the phenomena investigated for each article was compiled (see ). The data was sorted into the following categories in the master table: occupations, settings and sociocultural context, meaning expressions and themes/categories with content and quotes from the articles. These were labelled with the article number to facilitate going back and forth in the analysis process. The authors also noted key messages, metaphors, phrases, and ideas for each article, which were aimed to be used in the next step of the analysis. This first step provided a good feeling of a “sense of the whole” concerning the data collected.

Figure 2. Example of a part of the master table in step 1 analysis process and categorisation concerning contextual setting.

The contextual settings were then categorised concerning the most prominent context described to be used for further data interpretation. The categories and distribution were non-western context (n = 6), western context (n = 39), low socio-economic context (n = 7), living with disability (n = 18), and institutional context (prison, hospital) (n = 13). One article could comprise more than one category at the same time.

The selected articles were reread in the second step of the analysis in order to determine the ways in which they were related with each other. The authors determined the relationships between the studies and started synthesising within this step. A list of key messages and metaphors phrases, ideas, concepts, and their relationships (see ) were conducted by the first and third authors separately prior to meeting and being able to juxtapose them. An initial assumption about the relationships concerning experiences of meaningful occupation between the studies was made at the end of this step using both the master table and the list of key messages, ideas, concepts, and metaphors together with quotes from the 44 articles.

The studies were translated into one another in the third step of the analysis, which was first performed by the first and third authors. Translations protect the main central metaphors and concepts in each article, and within this step the researchers focused on metaphors and concepts in the articles, and the relationships between them, to identify emerging categories. The researchers also noted if the text the interpretations were made upon were first, second or third order constructs and made the abbreviations 1OC, 2OC or 3OC in the material. The number of studies included in this meta-ethnographic study was large, so within this step the various translations were interpreted and compared in order to determine whether some of the metaphors and/or concepts could be collapsed, resulting in eight emerging categories. One example of an emerging category was for instance that ideas and metaphors like “joy, satisfaction, hope, positive feelings in body and soul, instant reward and feeling wellbeing” that was a premature category framed as “cultivating feelings that are valued to individuals”, finally becoming category two. A co-analyzer with long and extensive experience in qualitative research, especially grounded theory (second author) was invited at this stage, and the authors met to discuss the categories with the second author to validate the findings for the first time. The second author had previously read the master tables, noted her interpretations and her emerging categories. The meeting resulted in a revision of the eight categories. The fourth step of the analysis was performed by synthesising the translations, which refers to “making a whole into something more than the parts alone imply” [Citation51, p. 32). All the authors met several times during this step discussing the interpretations over a period of several months. Five categories of experience of meaningfulness in occupation (with one main) were finally identified, and the five categories were all inter-related. The authors chose to exemplify the categories with quotes mainly from the first-level interpretations since Jensen and Allen [Citation99] had stated that this could internally validate the categories, thus increasing the trustworthiness. All the contextual categories were represented in the categories i.e. data from different socio-cultural contexts were represented in the five categories of experienced meaning.

Findings

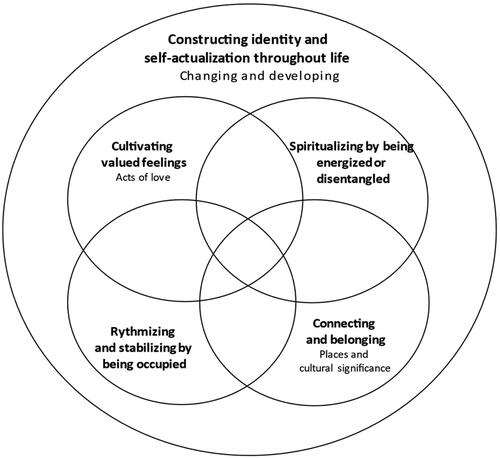

Five inter-related categories explaining the characteristics of experiences of meaningful occupation were identified in the synthesis, all related to each other, with category one representing the main category. The findings are firstly described with tables showing the articles revealing the category and the distribution of context categories from the articles. The findings concerning the interpreted texts synthesised are then described with illustrating quotes from the articles. Most of the quotes are voices from the participants who took part in the studies, where otherwise comments are made within brackets. The data revealed experiences of both present and absent characteristics explaining meaning within the categories in the synthesis. The authors have chosen to incorporate these findings, in accordance with the methodology [Citation51,Citation52], within the respective categories in order to highlight the meaning aspect in occupations, and the reduced well-being consequences when absent. The inter-related categories explaining why and how individuals experience meaningful occupation is illustrated in .

Constructing identity and self-actualising throughout life

The synthesis revealed that experienced meaning in occupations was described when performing occupations that were seen as constructing the individuals’ identity and when the occupations actualised the individuals’ sense of self, i.e. answering and discovering the questions of -Who am I? - What do I want? One subcategory identified was change and development described below. Aspects of both searching for identity, constructing identity, expressing identity, and being confirmed concerning one’s identity were interpreted as part of a process over a lifetime, which were also intertwined and in constant transformation.

I was happy. I was finding myself. Again, work really kind of defined me. I think that’s what I realized back then… it is part of my identity. So, when that was taken away from me, I got depressed. So, when I was back, I felt like I was getting myself back into play. (Article 3, p. 2148)

-I call it ‘My [her name] time’… there’s a lot about identity. It’s about reinforcing who I am and getting in touch with that sense of self…because I’m not there being the [job role], or [X]’s partner or [Y]’s co-parent. It is just me…and I’m doing one of the things that I like doing best. So, it’s …something about myself, almost like self-investment. (Article 13, p. 201)

The occupations were described as meaningful since they were actualising identity in their own eyes, as described above, however also in the eyes of others and existing social norms. Feelings of confirmation were interpreted as an important part of constructing one’s identity. For example, by being able to survive and fulfilling your basic needs. The meaningful occupations individuals engaged in confirmed their identity by social/societal norms such as thoughts of being and doing like everybody else or being accepted by others in some way.

I identify so strongly with my heritage, my being Scottish and a deeper sense, the whole Celtic thing. I am so much into the music thing and the culture that it really does … it’s my base, my rock. It’s what I go to when I’m feeling like a ship in the storm. It grounds me and I think that ties in with family and also my sense of separation from my family. It’s a lot about not losing myself in this cultureless norm that our society is. (Article 4, p.197)

-I can also tell that I’ve been doing something useful for a couple of years now… I think it’ s about showing that I’m also part of this and showing that you’re also participating in something bigger… to give yourself an identity in somebody else’ s eyes. (Article 34, p. 26)

The meaningfulness was interpreted as often clearly being attached to the individuals’ life stories and not seldom to culturally important events. The meaning was concerned with memories, history, hopes and goals, guiding the individual both in terms of choosing to do occupations or to abandon them.

Changing and developing

Experiences of meaningfulness in occupations changed over a lifetime as the sense of identity evolved and were affected by both inner and outer circumstances. The individual searched for a change or challenge to develop further at some points of time, while at other times the change was forced upon them or given to them, for example, when losing one’s partner. When life circumstances had changed, the individual was also forced to change and not in a positive way if the enjoyment in occupations no longer existed. However, some changes contained other types of challenges, forcing individuals to push their boundaries, or learn something new, which gave a feeling of growing and developing.

The young amateur soul-singer told about the day when she knew that there had been a significant physical change that impacted on her singing. The narrative describes a meaningful moment. For the audience, it is like witnessing a butterfly emerging from a chrysalis. For the narrator, her sense of self had changed. (Article 14, author, p. 270)

Occupations that were experienced as expressive, and sometimes also being creative, were described as meaningful by constructing and expressing the individual’s identity. Feelings of joy and being absorbed were often described when performing these types of meaningful occupations.

When I come to the group, I can let off steam and just hang out with the others. When I come back home, I’m really tired but I’m getting used to it. I need to come here to get it all out. It’s a way to express oneself, leaving everything aside. To work off your anger and enjoy yourself. (Article 20, p. 137)

The Ikebana activity (Article 21), which was a creative activity with an important socio-cultural link for the practitioner and her/his identity, was described as ‘‘all your creativity that you didn’t know was in there begins to come out and it comes out through the materials … [the materials] help you to express yourself.” (p. 269)

Cultivating valued feelings

The synthesis revealed that occupations could help individuals cultivate valued feelings, for example, satisfaction, happiness, relaxation, love, freedom, and gratitude for life. A subcategory was identified describing meaningfulness when doing activities as an act of love, described below. It could be, for example, when being in nature experiencing an almost healing force filling you with different feelings.

It is some kind of well-being and you just see the positive side of things, you just lie down on the lawn and look up into the tree, feel the warmth of the sun. (Article 27, p. 55)

Occupations giving unique experiences of inner peace, extra stimulation, ecstasy, and a sense of feeling fulfilled were expressed. Cultivating these valued feelings also promoted their well-being.

Acts of love

Expressions of occupations giving meaning as an act of love were interpreted as a subcategory among all the other feelings described above. Love was expressed from different angles as a reason for an occupation to be meaningful, the altruistic love, the love to a partner/friend/family or a passion for a certain occupation. Altruistic love and being benevolent was expressed as a type of moral “for the greater good” or “giving back”. Altruistic love could also be received, for example, by being accepted in society by doing a certain occupation. One participant at a day centre described.

[At the Day Centre] there are people with a particular character or other and we…try to keep the peace between them. And we always try to encourage them so that things go better. We encourage people and we are well liked too…Because of our love. [interviewer: So, you share your love with the people at the DC?]. Yes, yes, that’s why we like it there… (Article 39, p. 83).

Acts of love were also expressed as the bearing meaning when being with a partner, friend or when caring for family and others by doing certain occupations. Two examples of this were described; ‘‘it was love at first sight, so every time I see her it is meaningful. … Yes, that is the greatest, to be with the one you love and then also to have friends who understand you, who are on the same wavelength as you and who you can share the good times with’’ (Article 26, p. 98)

-When we cook there will be love involved in it. When we do it ourselves, the more care we take. (Article 1, p.5)

Spiritualising by being energised or disentangled

The synthesis revealed that occupations were experienced in a spiritual way giving meaning since they energised or set the individual in a disentangled (to be entangled from) state of mind, mostly by being totally absorbed and present in the occupation performed. Energising and disentangling were closely related, as two sides of a coin. For example, an occupation that was experienced as meaningful due to disentangling characteristics such as being absorbed with nature or in meditation were often described as having an effect of being energised, afterwards. Vice versa, being energised as the main meaning aspect within an occupation such as dancing, singing, or creating something was often described as a sensation of being disentangled since the occupation was so energising that the world around them faded out. Being energised could be expressed as feelings of balance, joy, ecstasy or having a flow-experience.

My favourite time is writing … Spirituality is a big thing for me. I’m becoming a recluse. I think a lot of my time I like to be to myself… I’ve been doing a lot of self-examination. Again, my writing is for myself. My writing is it just takes me into this space of spirituality, like I just can’t explain it. (Article 28, p. 282)

Participants were energised in different ways, in both quiet and peaceful activities, as well as in uplifting and demanding activities. Uplifting experiences, such as for example dancing, could be expressed as follows.

When I have been to a circle dance group, either the evening group or a weekend or our residential group, I just feel so much lighter and so much happier inside, better in myself … and it is physical as well because, I mean, the sheer exercise is good for me and that has a good impact. But also I have been around such wonderful people and dancing with them makes me feel good! And I don’t get that anywhere else to the same extent. (Article 13, p 202)

Experiences of being disentangled, were described as giving a sense of being disconnected and releasing/letting go of everything else around, and sometimes as being contemplative, meditative, and also reflecting on slow mood activities. Being creative was also often leading to experiences of being absorbed and being fully present. Nature was explicitly described as a force for contemplation, seen as unique in promoting these experiences. Two participants described; “… if it’s, you know, particularly beautiful landscape or dramatical I think that it gives you a kind of bit of a buzz.’ And ‘… it was the only time I’ve ever, ever heard complete silence and there was not one sound at all, it was absolutely amazing”. (Article 23, p. 89)

Different body and mind sensations when performing occupations were described within this category and expressed as spiritual. Multi-sensory stimulation was for example described in how individuals explored and used their bodies.

Connecting and belonging

The synthesis revealed that the occupations that the individuals valued had social contacts, which were interpreted and framed as connecting and belonging. Connecting was expressed in terms of having social contacts in everyday life that gave meaning in a broader sense, while belonging was described with greater intimacy than for connecting. A subcategory was identified and termed as places and cultural significance.

Connectedness was, for example, described as being at the same place while performing an occupation, just meeting, or doing something together. It could also consist of being in the social rhythm and energy of others, for example, at work.

- I’m here every day, Monday to Friday, I work to 12 o’clock on Mondays and to 12.30 the other days…It means a lot. You need to meet people and since I’ve been working here for many years with this, it’s like a need for me, meeting my work colleagues. (Article 2, p. 183)

Connectedness could also represent a feeling of being needed by and important for others and sometimes providing the individual with a feeling of normality and acceptance while fulfilling norms and values in society. When occupations containing this type of meaning were lost, the individuals spoke of reduced well-being. Belonging, was described as being dependent on closer relationships, with an intimacy with other individuals or groups. The intimacy could unite the individuals both by the sharing of a valued occupation and by a love for each other.

then there’s the social side of it, where I said earlier you meet friends: you, I have some very good friends through cycling and we have stayed friends for many years and we really enjoy meeting up with each other (Article 9, p.323)

A sense of belonging, almost like being in a separate zone or in a world of their own, was spoken of about participating in a group.

Places and cultural significance

Places were described as giving meaning in themselves and in relation to performing an occupation. Individuals described meaning at certain places, such as the home, a certain geographic place or a place that gave feelings of being safe or a personal space.

Since I have had to get rid of so many things [since she moved to the CCRC], it is important for me to make it feel like home in any way I can. And for me, that is primarily through colour and my art. So for example this room – I can work and be in this room, because it feels like me. (Article 29, p. 9)

Places that describe safety, such as a home that feel like me, could be interpreted as being closely related to self-actualising and belonging. Equipment or elements at the place were also described as meaningful due to providing the individual with important triggers and inspiration for engaging in occupations or connecting with others.

It is so nice here in the garden, they have arranged so that we have some tables and benches where we can sit in the sun. This was where I first met [a friend] I came to know her when I was sitting with some of my neighbours down here. I remember that it was a warm summer day and we sat on the benches, just talking and having a cup of coffee. We usually meet there in the summer you know. She came with some other older ladies who live nearby and now we are close friends. So, this is a nice place where we can meet, we have so much fun together. (Article 24, p. 413)

The place could also be of cultural significance, confirming the individuals’ culture, roles and traditions and thereby be experienced as meaningful.

See, in our society, the mother has to cook; no one else will cook. The mother has to cook for the children, for the husband… So it becomes our duty. (Article 1, p. 5)

Places could also give a sense of being imprisoned or unsafe. A lack of common spaces and the fact that, for example, patients in an institution (hospital or prison) were always expected to be in the institutional space provided. A lack of equipment and space to support activities deprived the individuals of engaging in occupations, leading to a sense of meaninglessness and risking a loss of identity.

I really don’t do anything by myself. I’d like to have a shaver and be able to go to the bathroom and shave as much as possible, but I don’t have a shaver—There’s only the hospital one, and that’s an instrument of torture…. (Article 12, p. 543)

Rhythmizing and stabilising by being occupied

The synthesis revealed experiences of meaning from doing occupations in a way that made the life rhythmized and stabilised. This could be seen as a continuum from filling time - to having a balance in life and to feeling harmony in everyday occupational patterns. Occupations, which gave structure and routines and made the individual fulfil important roles, were the key attributes gained attained by performing ordinary daily occupations, productive occupations or just by filling time on a regular basis.

….Really I have created this garden so that I won’t ever get bored. Now that I don’t have to go to work I can do the housework when I like and go out into the garden when I like. I don’t have a rigid structure, but I keep to the habit of going out into the garden every day. The garden is my passion and my project… (Article 30, p.144)

Structure in everyday life were also described by some groups as a very important factor for maintaining health.

“Well, I get sick [if I don’t hold on to my routines], I know that. I can’t sleep my days away”. (Article 27, p. 54). Some places could also have the function of giving structure by just going there on a regular basis. Work was described as an important regulator of time, creating a special rhythm and balance in everyday life. Two participants in article 34 described:

“You sleep normally and so on. Earlier, when I didn’t work, I slept in the daytime and was awake at night”… and “If you are at home, doing nothing, then you easily stay up all night watching TV and start sleeping all day. It’s so easy to turn night into day, and then you get more and more apathetic”. (p. 27)

Until a couple of days ago, I was the type who always took care of myself and have been totally independent, running a home and a family. Suddenly the roles are reversed—I’m glued to an oxygen tube and haven’t any stamina. It feels as if, I don’t know, as if I’ve somehow lost hold of what I was supposed to do. (Article 12, p. 545)

Discussion

The findings of this meta-ethnographic synthesis could be summarised as explaining the characteristics of why and how people experience meaning in occupation. Five inter-related categories with sub-categories built up a multi-facetted unique picture of “Who you are and want to be”. The synthesis included 44 articles from diverse cultures and contexts and the translation was related to the presence and sometimes absence of experienced meaning in occupation.

The main category “constructing identity and self-actualising throughout life” is a journey and transformation starting when you are born and ending when you die. Birth and death form the frame for all humans and over a lifetime we choose and experience occupations that give meaning in multiple ways while developing, transforming, and creating ourselves by doing and being challenged by both inner and outer circumstances and preferences. The journey is unique for everyone which also has been described in The Kawa model [Citation13,Citation37] as a complex journey flowing like a river through time and space. That individuals construct their identities in engaging in meaningful occupations and projects has also been described by Christiansen [Citation100,Citation101]. Further, Hammell [Citation10], Hitch et al. [Citation11] and Hasselkus and Dickie [Citation22] described the concept of becoming, (one of the four theoretical dimensions of doing, being, becoming and belonging) as the potential for growth, transformation and self-actualisation and a way of knowing and expressing oneself. Griffith et al. [Citation93] described meaningful occupation as a subjective, dynamic experience, fulfilling a drive and central to identity development which is in line with our findings. In existentialism [Citation17] this journey is described as finding your true self. Individuals strive for realising their full potential in life i.e. self-actualisation, and this is also in line with the established theory of Maslow [Citation102].

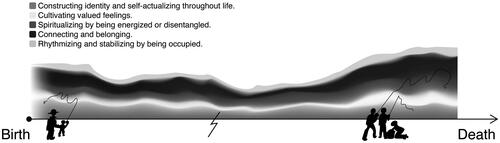

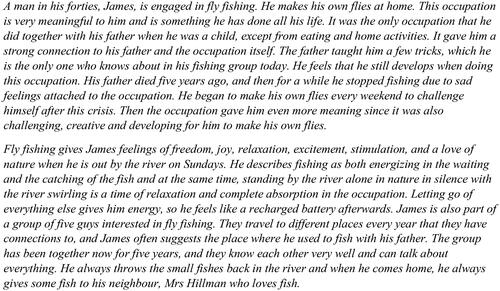

Identity is also shaped by our relationships to others and the socio-cultural context we live in by being confirmed, and both personal and shared values and culture guide our choices in what we want to become [Citation11,Citation13,Citation100,Citation101]. This association is also prominent in the findings of the synthesis. The five inter-related categories are illustrated by describing the fictive case of James and his experiences of meaning in fly fishing () and by visualising his flow of experiences of meaning throughout time ().

Figure 4. Description of the five categories explaining meaning in occupation related to James’ fly-fishing throughout time.

The case of James fly fishing is illustrating the multi-facetted picture of why and how he experienced meaning in one occupation throughout life () also visualise how the flow of inter-related categories shifted during James’s life and how experiences of meaning continued and/or shifted in character or goal. There was a significant shift when James’s father died, him turning towards another part of fly fishing by creating flies. His patterns of experiences were dynamic and complex even though only one single occupation is shown. People engage in a large number of occupations every day, which form an even more multi-facetted picture of meaning throughout life unique for an individual.

The second category “cultivating valued feelings” highlighted that people strive to engage in occupations that is experienced as meaningful due to eliciting desired and valuable feelings. Feelings of joy, satisfaction, freedom, love and relaxation and gratitude were expressed and these feelings were also stated as promoting well-being. These findings are in line with previous OT/OS theory describing the concept of being [Citation8,Citation11,Citation38] and in congruence with the concept of doing. Dubouloz et al. [Citation97] and Ikiugu [Citation25] pointed out that occupations and activities generating experiences of meaning are actions and doing that could generate positive feelings. The sub-category “acts of love” was interpreted as more clearly illuminated within this synthesis than in previous research. The altruistic love was clearly expressed and separated from two other areas of love, namely to others near you and love to a certain occupation. Hammell [Citation103] has previously described “doing for others” as also increasing the feelings of belonging. However, we interpret our findings within this sub-category as being on a more universal level, for the greater good of all people and our planet as a whole and sometimes expressed from religious perspectives. Expressions of love as libido were, however, not seen in the findings of this synthesis.

Experiences captured in category three “spiritualising by being energised or disentangled” have not been described as aspects of meaningful occupation in previous research to the authors knowledge. Spiritualising was evoked in an occupation either by being energised or disentangled and these experiences were related to each other as two sides of a coin. In OT/OS theory this category of meaning in occupation is closest in line with theories of being and belonging results as described in several studies [Citation10,Citation26,Citation38,Citation103] in being true to oneself and feeling united with others and nature in a spiritual way, as shown in our findings. Another interpretation could be that these meaningful experiences could be a result of what the human brain and body needs while also giving meaning. As humans we use our senses all the time, become stimulated, interpret what happens to us and the surrounding. A balance between being energised and disentangled could be a person’s way of choosing meaningful occupations to also get homeostasis and healing [Citation104]. Leung and colleagues [Citation105] also pointed out the importance of a holistic approach with the body, the mind and the spirit as forming a connected system facilitating meaning-making.

Category four “connecting and belonging” described the situatedness in context as an always present influence on how individuals experience meaning in occupations in their lives. The findings pointed out that the need of having connections to others, cultural significance and a sense of belonging were often the reason for meaning in a particular occupation. These findings confirm previous knowledge in OS and have been described by Hannam [Citation106] as a cultural world, and by Hooking [Citation26] and Hasselkus [Citation22] as situated meaning dimensions varying across individuals, families and cultures. The present findings revealed a distinction between experiencing meaningful relations containing intimacy, safety, freedom and the feeling of being authentic, which was framed as belonging. Experiences framed as connectedness in this synthesis represented experiences of having social relations, friends, and a sense of inclusion in relation to both people, places and culture. The authors interpret the findings as if there could be an important distinction in how close the social interaction is and how authentic the person feels. Belonging in relevant theories currently represents both aspects [Citation11,Citation38]. However, further studies are needed within this area to confirm our findings.

The sub-category “places and cultural significance” showed that occupations were experienced as meaningful in connections to a place, both in individuals’ memories and present lives. The home and nature were especially highlighted in the findings. This is in line with Hasselkus and Dickie [Citation22], stating that places can be a “container of memories of experiences” (p. 39) and that a place called home brings centeredness in a person’s life, safety, and a place to reach out from to the world. A home can also be spoken of as your country, or your culture [Citation35] filled with well-known traditions, sensory experiences, and memories. Places that were important for experiencing meaning in occupations were highlighted in the findings of the synthesis, showing that places are probably also important for occupational therapists to ask their clients about in relation to meaningful occupations. The places could represent a safe place, be part of their identity, serve as a personal zone, a place filled with memories awaking certain feelings such as joy, community, relaxation, or a feeling of being themselves. Places were also described as meaningful since they could trigger and stimulate the individual to meaningful occupation, due to having certain equipment, materials, space, or a certain atmosphere. Places and their cultural importance for meaning making has also been described by Hasselkus and Dickie [Citation22] and Rowles [Citation35]. In OT practice this knowledge is important to pay attention to when supporting clients and shaping therapeutic interventions. Experienced meaning due to carrying cultural significance for the individual was an expected finding and the relation to constructing identity and belonging. This has been described in previous research and theories [Citation7,Citation35,Citation37]. A strength of the synthesis, that the authors would like to highlight, is the large number of selected articles supporting the findings while representing different contextual settings and life-worlds, and not only the western culture and white middle-aged working people.

The fifth category explained experiences of meaning connected to “rhythmizing and stabilising by being occupied”. Being engaged in occupations providing rhythm and stability to everyday life instilled meaning by regularly performing cyclic occupations in a temporally meaningful, occupational pattern supporting occupational balance. Occupations served as giving structure during days, weeks and even years. Social and cultural cycles of doing activities performed in temporally structured patterns influence being with others and belonging in society [Citation2,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26]. Experiences of being occupied in rhythmizing and stabilising occupations are comprised of individual preferences, who you are and affected by culture and society, as well as natural circumstances such as day and night. Working with clients having difficulties in performing and orchestrating occupations that could lead to experiences of rhythmizing and stabilising (as for example people with persistent mental illness) [Citation107] is therefore essential, since it contributes to experiences of meaningful occupation.

Implications

The findings revealed a multi-facetted picture of why and how people experience meaning in occupation and the characteristics of the experiences that influence who they are (identity) and want to be (self-actualisation). The synthesis describes a more nuanced picture of how experiences of meaning is related to the development of self and identity. This knowledge emphasises the absolute necessity for occupational therapists working with clients and their meaningful occupations to make efforts in understanding the individual experience, their occupational story, using occupational storytelling and being client centred [Citation22, pp 1–13). The inter-related categories of meaning experiences imply the need of a narrative approach capturing the history, relationships, contexts, and development of the meaning aspects in the clients’ occupations in order to be able to support them. Further, when inner or outer circumstances challenge or force the clients to change or adapt due to, for example, disease, crisis or disasters, the occupational therapist needs knowledge about existential crisis, transformation/change processes and how they could affect engagement in meaningful occupation in interventions. A recent study by Backman et al. [Citation108] investigating useful OS concepts for occupational therapy practice described “occupational meaning” as “The value and significance of occupations, as experienced and interpreted by an individual as an occupational being. Includes the contribution of those meanings to development, identity, agency, and transformation.” (p. 7) and the experts agreed to 90% of the usefulness of occupational meaning in both OT and OS. However, research and theories seem diverse and multi-facetted. Therefore, more research is needed that is empirically grounded. For example, could we understand the occupational loss that contain all five meaning categories as a larger crisis for a client than if the occupation had contained only one category? What does experiences of meaningful occupation mean over time, are there any relationships between different meaning aspects and/or wellbeing? More research is needed to be able to support clients and enabling occupational therapists to share a mutual understanding.

The findings of the synthesis suggests that the five categories characterising the experience of meaning in occupations could be viewed as knowledge explaining WHY and HOW occupations are experienced as meaningful, uniquely based on 44 empirical qualitative studies of participants expressions of their experienced occupations in life. Previous research describing that having meaningful occupations affected an individual’s wellbeing positively, and the lack of meaning in occupation affected well-being negatively [Citation3,Citation9–11,Citation15,Citation103] were also illustrated in our synthesis. This association with the presence or absence of the characteristic lies implicit in the findings based on the 44 articles, however not forming a specific category. More research is needed to strengthen the findings of this synthesis, preferably with longitudinal designs and more qualitative approaches since meaning is individual, unique, dynamic, and time as well as contextual circumstances change throughout the lifespan. The five categories explaining and characterising meaning in occupation were found in all the contextual settings (see –), also in non-western countries, low socio-economic settings, institutional contexts and among people living with disabilities. This knowledge is important for occupational therapy practice and research in occupational science. Occupational therapists need to understand meaningful occupation among all people with all its richness and diversity [Citation41,Citation42] when working in different areas enabling meaningful occupation together with their clients.

Table 2. Main category and subcategory represented in articles and distribution of contextual settings.

Table 3. Category two and subcategory represented in articles and distribution of contextual settings.

Table 4. Category three represented in articles and distribution of contextual settings.

Table 5. Category four and subcategory represented in articles and distribution of contextual settings.

Table 6. Category five represented in articles and distribution of contextual settings.

Need for future research

A reflection on what seems to be absent in the data, which probably could further expand knowledge is relevant. For example, data based on experiences from people occupied in criminal and drug contexts in society or people living in societies with dictatorial rule were missing. People in criminal and drug contexts most likely experience meaning such as constructing identity within their life and context as well as cultivating valued feelings, belonging, being energised or disentangled etc. in the occupations they perform. Even though society views these occupations as negative, criminal, and leading to negative well-being outcomes, they are probably subjectively experienced by the participants as meaningful. Recent articles highlighted the importance of not viewing meaningful occupations as only positive and healthy for the individual or surrounding individuals and community [Citation109,Citation110].

Similarly, the possibilities and contextual frame of for example living in a dictatorial rule could probably impact greatly on choosing occupations that are meaningful since they may be prohibited due to the rules or a religion. More research is needed within this area to expand and strengthen theories and models in occupational therapy as well as in occupational science. Another reflection was that neither an occupation performed such as sex, nor occupations performed for revenge, jealousy, to hurt, through shame or by anger were mentioned in the articles. Neglecting or not mentioning sex activities is quite common in empirical studies [Citation111], and there is a lack of research in the occupational therapy field about sex activities. However, knowledge about meaning in these occupations are needed. Research into negative feelings as a drive for meaningful occupation is to our knowledge lacking [Citation109]. Most of the previous research highlights what is viewed as positive aspects in different ways. However, further research about meaning in occupations due to these prohibited or hidden feelings and circumstances is needed, since the human drive to be occupied is probably more complex.

The OT profession needs overall a more nuanced knowledge about how we can understand individuals and their experiences of meaningful occupation to be able to support them in their socio-cultural context [Citation112]. It is important to take the challenge to research complex phenomena such as meaningful occupation in our field and discuss them in order to move forward, as stated by Borell et al. [Citation113]. The present meta-ethnography is one step on the way, based on qualitative empirical studies from different contexts all over the world.

Limitations

We have synthesised data from 618 participants in this article to identify the five categories explaining characteristics of experienced meaning in occupation. The authors believe that meta-ethnography of qualitative research has a good potential for understanding phenomena and possibilities for theory development. The method is demanding in terms of reflexivity, openness, and transparency, however, suitable for synthesising evidence and large amounts of data about important phenomena within a profession that could lead to moving occupational therapy practice and science forward [Citation112]. PRISMA [Citation54] search strategies were followed during the selection procedure as part of the study design. This was seen as a strength concerning selecting relevant articles and rigour concerning scientific quality. The inclusion criteria of original articles in English decreased the number of selectable articles. A limitation of this synthesis was also that some of the articles capturing the scope of meaning had poor scientific quality and were excluded, which decreased the socio-cultural representation of the articles. The authors were well aware that the concept of meaning could be used differently in qualitative methods, as well as when describing and explaining experiences of meaning in occupation from different perspectives. This could, without our knowledge, be both a weakness and a strength in the analysis process. The findings must also be interpreted with caution concerning the voice of other socio-cultural aspects that are not represented. Despite this, our interpretations highlighted five inter-related categories explaining experiences of meaningful occupation represented by research in different contextual settings. The meta-ethnography proposed by Noblit and Hare [Citation51] was applied for synthesising. It was a time-consuming and team-based work. All the authors were involved in different stages of the analysis, cross-checking the interpretations of data was used several times to increase the trustworthiness of the findings. The second author had another research background in occupational therapy, which was very valuable in the analysis process. All the authors had good qualifications and experience of doing qualitative research. The first author was the leader of the team and arranged continuous meetings to discuss and cross-check the development of the emerging synthesis. The data were handled as faithfully as possible and as true to its source as possible. So true that the research participants should be able to recognise their experiences, as recommended by Jensen and Allen [Citation99]. This monitoring and the processes ought to have increased the credibility of the findings [Citation52].

Summary

The meta-ethnographic synthesis included 44 empirical articles, studying meaning experiences of occupation in diverse populations and different socio-cultural contexts. The findings revealed that subjective experiences of occupation have five categories of characteristics attributing to experiencing an occupation as meaningful. The main category was constructing identity and self-actualising throughout life and the other four categories were cultivating valued feelings, spiritualising by being energised and disentangled, connecting and belonging, and rhythmizing and stabilising by being occupied. The inter-related categories describe and explain why and how individuals experience meaning in occupation and reveals new aspects as well as confirming previous occupational therapy research and theory. This meta-ethnographic synthesis revealed knowledge describing and explaining what characterise occupations experienced as meaningful when present or meaningless when absent.

Acknowledgement

Thank you to all participants and researchers in our selected articles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Yerxa EJ. Seeking a relevant, ethical, and realistic way of knowledge for occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45(3):1–26. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.199.

- Zemke R, Clark F. Occupational science. The evolving discipline. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company; 1996. p. 2003.

- Clark F. Occupation embedded in a real life: interweaving occupational science and occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1993;47(12):1067–1078. doi: 10.5014/ajot.47.12.1067.

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT). About Occupational Therapy. 2022. https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy.

- Pierce D. Occupational science: A powerful disciplinary knowledge base for occupational therapy. In D Pierce, editor. Occupational science for occupational therapy. SLACK Incorporated; 2013. p. 3–4.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). CAOT Publications ACE; 1997.

- Jonsson H, Josephsson S. Occupation and meaning. In: Christiansen CH, Baum CM, editors. Occupational therapy performance, participation, and well-being. Thorafare: SLACK; 2005. p. 117–127.

- Wilcock A. Reflections on doing, being and becoming. Aus Occup Therapy J. 1999;46(1):1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1630.1999.00174.x.

- Rebeiro KL, Day D, Semeniuk B, et al. Northern initiative for social action: an occupation-based mental health program. Am J Occup Ther. 2001;55(5):493–500. doi: 10.5014/ajot.55.5.493.

- Hammell KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(5):296–305. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100509.

- Hitch D, Pépin G, Stagnitti K. In the footsteps of wilcock, part one: the evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28(3):231–246. doi: 10.3109/07380577.2014.898114.

- Hitch D, Pepin G, Stagnitti K. The pan occupational paradigm: development and key concepts. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(1):27–34. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1337808.

- Iwama MK, Thomson NA, Macdonald RM. The Kawa model: the power of culturally responsive occupational therapy. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(14):1125–1135. doi: 10.1080/09638280902773711.

- Leufstadius C. Experiences of meaning of occupation at day centers among people with psychiatric disabilities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(3):180–189. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1325933.

- Ikiugu MN. Meaningfulness of occupations as an occupational-life-trajectory attractor. J Occup Sci. 2005a;12(2):102–109. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2005.9686553.

- Unruh AM, Versnel J, Kerr N. Spirituality unplugged: a review of commonalities and contentions and a resolution. Can J Occup Ther. 2002;69(1):5–19. doi: 10.1177/000841740206900101.

- Harris E. Søren kierkegaard’s existential challenge – become subjective!/Edward Harris. Existentiellt Forum. 2013.

- Kierkegaard S. Antingen – Eller: ett livsfragment. Första delen. [either – or: a fragment of life. First part]. 2002. Swedish: Nimrod.

- Kierkegaard S. Antingen – Eller: ett livsfragment. Andra delen. [either – or: a fragment of life. Second part]. 2002. Swedish: Nimrod.

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence: a developmental theory of positive aging. New York: Springer Publishing Co Inc; 2005.

- Chan CL, Chan TH, Ng SM. The strength-focused and meaning-oriented approach to resilience and transformation (SMART) a body-mind-spirit approach to trauma management. Soc Work Health Care. 2006;43(2-3):9–36. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n02_03.

- Hasselkus BR, Dickie VA. The meaning of everyday occupation. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2021.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare: Slack; 2015.

- Taff SD, Price P, Krishnagiri S, et al. Traversing hills and valleys: exploring doing, being, becoming and belonging experiences in teaching and studying occupation. J Occup Sci. 2018;25(3):417–430. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2018.1488606.

- Ikiugu MN. Meaningful and psychologically rewarding occupations: characteristics and implications for occupational therapy practice. Occup Ther Mental Health. 2019;35(1):40–58. doi: 10.1080/0164212X.2018.1486768.

- Hooking C. The challenge of occupation: describing the things people do. J Occup Sci. 2009;16(3):140–150.

- Law M, Laver-Fawcett A. Canadian model of occupational performance; 30 years of impact!. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(12):519–519. doi: 10.4276/030802213X13861576675123.

- Trombly CA. Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49(10):960–972. doi: 10.5014/ajot.49.10.960.

- Shahbolaghi FM, Rassafiani M, Haghgoo HA. The meaning of work in people with severe mental illness (SMI) in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Ira. 2015;29:179.

- Sutton D. Recovery as the re-fabrication of everyday life: exploring the meaning of doing for people recovering from mental illness. New Z Occup Ther J. 2010;58(1):41.

- Avrech Bar M, Forwell S, Backman C. Ascribing meaning to occupation: an example from healthy, working mothers. OTJR. 2016;36(3):148–158. doi: 10.1177/1539449216652622.

- Lintner C, Elsen S. Getting out of the seclusion trap? Work as meaningful occupation for the subjective well-being of asylum seekers in South tyrol, Italy. J Occup Sci. 2018;25(1):76–86. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1373256.

- Križaj T, Robert A, Warren A, et al. Early hour, golden hour: an exploration of slovenian older people’s meaningful occupations. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2019;34(2):201–221. doi: 10.1007/s10823-019-09369-5.

- Perkinson MA, Briller S. Connecting the anthropology of aging and occupational therapy/occupational science: interdisciplinary perspectives on patterns and meanings of daily occupation. Anthro Aging Quart. 2009;30:25–41.

- Rowles GD. Place in occupational science: a life course perspective on the role of environmental context in the quest for meaning. J Occup Sci. 2008;15(3):127–135. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2008.9686622.

- Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge (US): Harvard University Press; 1990.

- Iwama M. Meaning and inclusion: revisiting culture in occupational therapy [editorial]. Aus Occup Therapy J. 2004;51(1):1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2004.00429.x.

- Hitch D, Pepin G. Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy: an analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(1):13–25. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1726454.

- Zemke R. The eleanor clark slagle lecture- time, space, and the kaleidoscopes of occupation. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58(6):608–620. doi: 10.5014/ajot.58.6.608.

- Kavedzija I. Introduction. The ends of life: time and meaning in later years. A&A. 2020;41(2):1–8. doi: 10.5195/aa.2020.320.

- Hammell KW, Iwama MK. Well-being and occupational rights: an imperative for critical occupational therapy. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(5):385–394. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2011.611821.

- Hammell KW. Building globally relevant occupational therapy from the strength of our diversity. WFOT Bulletin. 2019;75(1):13–26. doi: 10.1080/14473828.2018.1529480.

- Dos Santos V, Spesny SL. Questioning the concept of culture in mainstream occupational therapy. Cad Ter Ocup UFSCar. 2016;24(1):185–190. doi: 10.4322/0104-4931.ctoRE0675.

- Trentham B, Cockburn L, Cameron D, et al. Diversity and inclusion within an occupational therapy curriculum. Aust Occup Ther J. 2007;54:49–56.

- Chan CCY, Lee L, Davis JA. Understanding sustainability: perspectives of Canadian occupational therapists. WFOT Bulletin. 2020;76(1):50–59. doi: 10.1080/14473828.2020.1761091.

- Estabrooks CA, Field PA, Morse JM. Aggregating qualitative findings: an approach to theory development. Qual Health Res. 2018;4(4):503–511. doi: 10.1177/104973239400400410.

- Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus on qualitative methods, qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(4):365–371. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199708)20:4<365::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-E.

- Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;50(2):204–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x.

- Gewurtz R, Stergiou-Kita M, Shaw L, et al. Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on the utility and challenges in occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 2008;75(5):301–308. doi: 10.1177/000841740807500513.

- Roberts AEA, Bannigan K. Dimensions of personal meaning from engagement in occupations: a metasynthesis. Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(5):386–396. doi: 10.1177/0008417418820358.

- Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1988.

- Paterson BL, Thorne SE, Canam C, et al. Meta-study of qualitative health research: a practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2001.

- France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med Res Meth. 2019;25(19):1–13.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

- Levitt HM, Bamberg M, Creswell JW, et al. Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA publications and communications board task force report. Am Psychol. 2018;73(1):26–46.

- Patel S, Dsouza SA. Indian elderly women’s experiences of food procurement and preparation. J Women Aging. 2019;31(3):213–230. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2018.1434963.

- Saunders S, Nedelec B, MacEachen E. Work remains meaningful despite time out of the workplace and chronic pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(18):2144–2151. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1327986.

- Rebeiro Gruhl K. Becoming visible: exploring the meaning of busking for a person with mental illness. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(2):193–202. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1247381.

- Peoples H, Brandt Å, Wæhrens EE, et al. Managing occupations in everyday life for people with advanced cancer living at home. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(1):57–64. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2016.1225815.

- Moloney L, Rohde D. Experiences of men with psychosis participating in a community-based football programme. IJOT. 2017;45(2):100–111. doi: 10.1108/IJOT-06-2017-0015.

- Marshall CA, Lysaght R, Krupa T. The experience of occupational engagement of chronically homeless persons in a mid-sized urban context. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(2):165–180. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1277548.

- Kamwesiga JT, Tham K, Guidetti S. Experiences of using mobile phones in everyday life among persons with stroke and their families in Uganda – A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(5):438–449. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2016.1146354.

- Feighan M, Roberts AE. The value of cycling as a meaningful and therapeutic occupation. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(5):319–326. doi: 10.1177/0308022616679416.

- de Bruyn M, Cameron J. The occupation of looking for work: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of an individual job-seeking experience. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(3):365–376. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1341330.

- Palacios-Ceña D, Gómez-Calero C, Cachón-Pérez JM, et al. Is the experience of meaningful activities understood in nursing homes. A qualitative study. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(2):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.10.015.

- Eriksson L, Öster I, Lindberg M. The meaning of occupation for patients in palliative care when in hospital. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(5):541–552. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515001352.

- da Costa ALB, Cox DL. (2016) The experience of meaning in circle dance. J Occup Sci. 2016;23(2):196–207. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1162191.

- Taylor J, Kay S. The construction of identities in narratives about serious leisure occupations. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(3):260–276. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.803298.

- Lang C, Brooks R. The experience of older adults with sight loss participating in audio book groups. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(3):277–290. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.851763.

- Falardeau M, Morin J, Bellemare J. The perspective of young prisoners on their occupations. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(3):334–344. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2014.915000.

- Cunningham MJ, Slade A. Exploring the lived experience of homelessness from an occupational perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1304572.

- Blank A, Finlay L, Prior S. The lived experience of people with mental health and substance misuse problems: dimensions of belonging. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;79(7):434–441. doi: 10.1177/0308022615627175.

- Van Dongen I, Josephsson S, Ekstam L. Changes in daily occupations and the meaning of work for three women caring for relatives post-stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21(5):348–358. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2014.903995.

- Eidevall K, Leufstadius C. Perceived meaningfulness of music and participation in a music group among young adults with physical disabilities. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(2):130–142. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.764817.

- Watters AM, Pearce C, Backman CL, et al. Occupational engagement and meaning: the experience of ikebana practice. J Occup Sci. 2013;20(3):262–277. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2012.709954.

- Roberts AEK, Farrugia MD. The personal meaning of music making to maltese band musicians. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(2):94–100. doi: 10.4276/030802213X136032444192.

- Wensley R, Slade A. Walking as a meaningful leisure occupation: the implications for occupational therapy. Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75(2):85–92. doi: 10.4276/030802212X13286281651117.