Abstract

Introduction

Residential reasoning is a complex process that includes decisions on whether to age in place or to relocate. Ageing in the Right Place (ARP), a web-based housing counselling service was created to support older adults in this process. The study’s aim was to evaluate the usability of the ARP as regards content, design, specific functions, and self-administration as a mode of delivery and to lay the ground for further optimisation.

Material and method

Nine women and five men (aged 66–82) completed a series of tasks using the ARP. Qualitative and quantitative usability data were collected through online interviews. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis and descriptive statistics.

Results

Experiences of the specific functions, content, and design of the ARP were described as mainly positive. Additions to the content and optimisation to assist in the general navigation of the website were suggested. The participants disagreed regarding the preferred mode of delivery, which indicates a need for selectable options. A system usability scale median score of 84 indicated acceptable usability.

Conclusion

The ARP seems to have acceptable usability, which paves the way for further evaluation.

Significance

By enabling residential reasoning, older adults are supported to make proactive choices based on informed decisions.

Introduction

Paragraph: use this for the first paragraph in a section or to continue after an extract.

It is well known that most older adults want to stay in their homes as they age [Citation1–3], and ageing in place can offer a sense of familiarity and autonomy as well as enable control in later life [Citation4–6]. The home is recognised as a place of comfort and safety [Citation2,Citation7,Citation8], and ageing in place is therefore supported by the policy when health care and social services are centralised around the home [Citation8,Citation9]. Occupational therapists working with older adults can offer a variety of interventions to support ageing in place. Assistive devices and/or environmental modifications are common interventions aimed at supporting walking (indoors and outdoors), self-care, and social contact [Citation10]. As part of environmental modifications, housing adaptations can allow a person to age in place despite disability [Citation11]. Ageing in place is linked to policy and practice that aim to support older people in maintaining autonomy and the possibility of remaining living in their current home in later life [Citation4,Citation12]. The concept of ageing in place is grounded in theory and can be understood from different perspectives [Citation4,Citation13,Citation14]. The predominant approach in the literature is the systemic ecological perspective, primarily influenced by the competence-press model, which conceptualises older adults as being part of a series of dynamic transactions with their environments [Citation15]. From this perspective, ageing in place can be facilitated when there is a balance between the demands of the environment and the abilities of the individual. In policy contexts and the public debate, ageing in place is used as a goal in line with the wishes of most older adults and contributes to societal cost-savings. In Sweden, most home care interventions are developed and customised by that policy, and environmental modifications to support ageing in place are regulated by law [Citation16]. However, such reactive and compensatory interventions fail to deal with the challenges of today’s critical demographic change. The Swedish government has recognised the problems of reactive health care and social services, which has led to nationwide reforms in integrated care [Citation17]. It follows that services promoting health should also be developed, evaluated, and incorporated into occupational therapy services.

Summarised in a literature review by Roy et al. [Citation18], studies have shown that housing decisions are affected by many factors related to the built and natural environment, social, psychological, and economic aspects, etc. Granbom et al. [Citation19] described the reasoning of older adults about whether to age in place and defined residential reasoning as a changing process that includes ongoing adjustment and decision-making. In general, persons around retirement age relocate for social or family reasons, often to smaller dwellings, with the aim of reducing housing costs, improving proximity to services, and getting access to better neighbourhoods [Citation2,Citation20,Citation21]. If the need for care and support increases later in life, residential reasoning is more preoccupied with how the home environment might impact feelings of safety as well as participation and independence when it fails to accommodate health, social, and financial changes or life events [Citation2,Citation22,Citation23]. Thus, for many older adults, residential reasoning is an ongoing, complex decision-making process that extends over time and includes negotiations with oneself, partners, and family members [Citation21,Citation24]. An overall bad fit between the home environment and the older adult’s needs could be a source of disablement or dissatisfaction [Citation25], causing loneliness, reduced quality of life, increased caregiver burden, unnecessary care needs, restricting opportunities to age in place and eventually lead to a move to residential care [Citation26]. Ageing in the right place expands on the concept of ageing in place by emphasising the importance of selecting an appropriate and supportive environment for older adults to age comfortably [Citation27,Citation28]. This concept suggests that simply staying in one’s current home may not always be the most suitable option. ‘The right place’ takes into consideration factors beyond the residence itself, such as the overall community, access to healthcare, social opportunities, and the ability to meet changing needs as individuals age and recognises that the ideal environment may vary from person to person. As such, a novel approach from an occupational therapy perspective could be to support the residential reasoning process independent of if the individual prefers to remain in his/her current home or relocate to another dwelling. As far as we know, there are no services to support residential reasoning in Sweden.

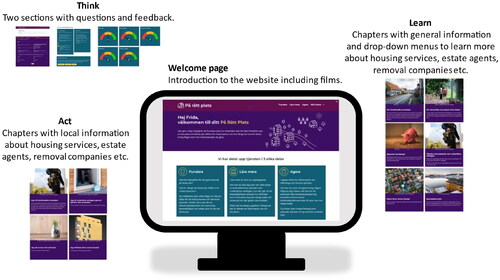

Recognising the complexity and dynamic relationship between the person and the environment [Citation25], the Ageing in the Right Place (ARP) housing counselling service was developed in collaboration with older adults and representatives of the housing sector to assist older adults in making informed decisions regarding their housing situation [Citation29]. Theoretically, the ARP was based on the Model of Human Occupation [Citation25], the Model of Residential Normalcy [Citation30], and the Transtheoretical Model of Behaviour Change [Citation31] to address the user’s unique situation and tailored to individual needs. To accommodate people at different stages of residential reasoning and decision-making, the ARP consists of three modules: Think, Learn, and Act [Citation29]. The idea is to facilitate awareness and stimulate users to reflect on their current and future housing situation (Think), increase knowledge in support of informed decision-making (Learn), and enable the user to take action once a decision has been reached (Act), see Apppendix 1 for a full overview. The Think module consists of two sets of questions: Think and Think More. Based on the responses to the questions, an algorithm integrated into the ARP generates individualised feedback in the form of text (for the Think questions) and graphics (for the Think More questions), see . The Learn module, divided into six chapters, provides information on topics related to housing. The information is accessed via drop-down menus, enabling the user to choose on the basis of interest and knowledge gaps. The Act module includes information about local, private, and public services regarding housing and relocation, for example, services related to construction or cleaning, health and social care services, and housing agencies. Once implemented, the update of the information in the Act module will be monitored according to an agreement between representatives of the research team (holding the scientific and commercial rights for the ARP) and the municipality and companies, respectively. The modules can be used separately or in combination, regardless of whether the user wants to make an immediate change or just wants to seek more information for future housing decisions. After creating a personal account, the user can save information and individual feedback, thus enabling continued personal reflection on changes in resources and needs related to the decision-making process.

Given the complexity of the ARP service, the context it was designed for, and potential outcomes, the development process was guided by the framework for the development and evaluation of complex health interventions produced by the British Medical Research Council (MRC) [Citation32]. Focus group interviews conducted during the development phase indicated that the ARP was relevant with regard to its content, the logic of the modules, and the preliminary design [Citation29]. In an iterative process of development and small-scale testing, the ARP has been finalised as a web-based, ready-to-use, online prototype developed for one municipality in central Sweden as a test site. To determine how older adults experience the ARP, the next step in the process of future evaluation and implementation [Citation32] was to explore the usability of the service. Usability is here defined as efficiency (whether the ARP behaves as expected), effectiveness (whether the user can achieve his/her goals with the ARP accurately, completely, and within an appropriate time span), and overall satisfaction (the user’s perception, feelings, and opinions) [Citation6,Citation33]. Thus, the aim of this study was to (i) assess usability in relation to how users experienced content, design, specific functions, and the self-administered use of the ARP web-based housing counselling service and (ii) prepare for further optimisation.

Material and methods

This study was performed as a usability study using interviews and content analysis to evaluate the experience of performing a set of tasks in the web service. In addition, the participants rated their experience using an established questionnaire for evaluation of usability. To improve the ARP, we sought to identify its strengths and deficiencies as experienced and described by the users [Citation34].

Recruitment and participants

Participants were recruited based on convenience snowball sampling using personal networks, suggestions from already recruited participants, senior citizen organisations in the test municipality, and the User Board at the Centre for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE), Lund University. The User Board includes older adults who are representatives of non-governmental organisations such as senior citizens’ associations, are interested in research, and provide input and ideas for various research projects [Citation35].

The inclusion criteria were being 65 years of age or older, living in ordinary housing, having access to a smartphone, tablet, or computer, ability to use the internet, having an active email address, and being able to communicate and read written instructions in Swedish. Exclusion criteria were not being able to complete the tasks or interviews because of cognitive decline or insufficient language skills. When data had been collected from 14 participants, we observed that the same comments reoccurred, and no further recruitment for participants was made. The sample included nine women and five men (N = 14) aged 65–82. Four participants lived in the test municipality. See for further details.

Table 1. Participant characteristics, N = 14.

The participants received a letter with written information about the study, instructions, and material for testing the usability of the ARP, and a consent form to be returned in a prepaid envelope. The instructions and material included a logbook (see Appendix 2) with two lists of tasks to be completed and the System Usability Scale (SUS) questionnaire [Citation36]. The first list of tasks focused on first impressions of content, design, and specific functions, when initiating the use of the service and using the Think module. The specific functions addressed were logging into the system, watching three short introductory films, considering the relevance for the target group, and responding to the questions in the Think and Think More module. The second list of tasks focused on the impressions of content, design, and specific functions in the Learn and Act modules. The users were asked to click on three different chapters, use the drop-down menus, and click on hyperlinks. The chapters to be explored were Finances and housing in the Learn module, and I want to future-proof my housing and I want to move house in the Act module. Questions in the first task list focused on optimisation of the service and whether the participant used the service independently or with assistance. The specific functions addressed in the second task list included internal navigation on the website, navigation between external web pages, and returning to the ARP. The completion of each task list was followed by a semi-structured online interview. Examples of core questions were: what was your impression of the page/the chapter; was there anything missing/superfluous; how did you find the design in the specific chapter; were you able to answer all questions using the response options available; were you able to find your way back from the external links to the web service; was the text synced with the sound in the film; did the drop-down menu work accordingly? For added credibility, the interview guide (see Appendix 3) was tested prior to the first interview. All interviews were conducted by the first author, a chartered occupational therapist with 15 years of clinical experience and previous experience of interviews in a research context. During the interview, screen-sharing was used to jog the memory and ensure that the interviewer and the participant were referring to the same part of the ARP. The interviews lasted 35–60 min each.

After the interview, following the second task list, the participant was asked to rate usability on the SUS questionnaire [Citation36,Citation37]. The questionnaire consisted of 10 statements, scored on a 5-point Likert scale of strength of agreement, where 1 indicated no agreement [Citation36]. The questionnaire has a reasonable level of reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83–0.97 [Citation37,Citation38].

All participants completed the tasks in the logbook and the SUS questionnaire and were interviewed. Although one participant viewed the website on her smartphone, only tablets and computers were reported to have been used to complete the tasks.

Data analysis

The interviews (22 h in total) were transcribed by the first author and analysed using a deductive approach and qualitative content analysis [Citation34,Citation39]. Transcribing took place partly continuously, partly in connection with coding, over a period of 10 months. Prior to the coding, all transcriptions were read through several times to increase credibility. Predefined categories based on content, design, specific functions, self-administration definitions, anchor examples, and coding rules were put together in a study-specific coding guide [Citation39]. Codes were then created based on the logbook tasks using the NVivo software (version 12) to facilitate the analytic procedure. Half of the transcripts were coded with the predetermined codes and discussed at meetings involving the first, second, and last authors. The remaining material was then coded in the same fashion. Next, the content of each category was summarised to describe the variation in the material. When participants expressed similar experiences and opinions in different ways, this was taken into account [Citation40]. The first author analysed all interviews, and the second and last authors read through two transcriptions. The analysis process was discussed in detail with the last author.

For the quantitative data, an individual sum score of SUS was calculated for each participant: higher scores indicate better usability [Citation36,Citation37]. These individual scores were used to calculate a group median. A score > 70 was considered to meet the usability requirement [Citation37].

Ethical approval

Participants in the study were given written and verbal information about the study and were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Written informed consent was obtained prior to assigning a login for the website. Interview data is saved in secure data storage at the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University. Participant names have been pseudonymised to ensure anonymity.

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (No. 2020-03457).

Results

The participants described a mainly positive experience with regard to the content, design, and specific functions of the ARP service. Most participants described the website as being information-rich, although additions with respect to content and function were suggested. The use of recurring colours and design features created a sense of familiarity, which enhanced overall usability and shaped the expectations of the different modules. Some participants described navigation difficulties, but overall, the satisfaction with content, design, and functions was high, both as described in the interviews and as rated through the SUS questionnaire.

Content

The content of all modules was described as informative, relevant, and extensive. The texts were perceived as well-written, clear, concise, and easy to understand, with a non-judgemental tone. The different chapters were relevant, practical, and rich in information. It was considered positive to be able to continue reading more about specific areas of interest:

‘Something that was particularly good was this thing of clickable links that I could move on straight away. Without having to make much of an effort personally.’ (Emelie, aged 76)

‘They did not mention what would happen if one of us disappeared. Would the one remaining then be able to continue to live in this apartment?’ (Lillemor, aged 65)

Most of the participants described the question section in the Think module as relevant and easy to answer. The number of questions was appropriate, with no redundancy, and the follow-up questions in Think More were seen as a logical continuation going deeper into the reasoning process. The response options were appropriate, and overall, it was easy for participants to choose a relevant answer. However, participants described difficulties answering questions specifically directed at families when there was none, and similarly for those with a family when response options did not consider different partner constellations:

‘Then, all these questions are addressed to me as an individual, but that is not how it works if you are a couple. And this makes it difficult to answer some questions’ (Anna, aged 75)

‘… in my case, they ended up in the same direction, so to speak. Where the value arrows pointed (graphic feedback), that was also where the recommendations (written feedback) that I received pointed.’ (Thomas, aged 71)

The films were described as interesting and thought-provoking. They captured the complexity of decisions about moving or staying, presented good reasoning, and elucidated different ways of thinking about the future. Opinions varied about how far the people presented in the films and pictures were representative, and some criticisms were raised. Some participants saw a lack of variation in terms of age and health status of older adults and described the ARP as portraying unrealistically helpless people who knew nothing at all. Others made the opposite criticism that the pictures and films showed persons who were too healthy, thereby excluding those who were dependent on others. Also, the older adults presented in the films lived in normative relationships that did not reflect the current variety of relationships and households. This criticism was also directed at the pictures as it was important for the participants to be able to relate to the people shown:

‘It should be people with a few flaws. And I think that would be a very good thing because then you can make comparisons, I think. (Märta, aged 81)

Design

The design was perceived as facilitating use. Recognising the same layout in different modules and chapters made the participants know what to expect, which contributed to the perceived accessibility. The choice of colours facilitated general orientation and made the participants feel welcome, and the text was easy to read:

‘The first impression was that it was something that was positive.’ (Sofia, aged 83)

Specific functions

Overall, the specific functions were described as straightforward. This applied to creating a new user login, answering questions, saving answers, receiving feedback, navigating internally on the website, navigating between external webpages and the ARP, watching films and pictures, etc. However, some technical issues arose when responding to the questions in the Think and Think More module, such as the site not loading or not being able to fill in numbers in the box. Furthermore, several participants had difficulties finding all the questions in Think More, which led to feedback being generated that did not match the participant:

‘Difficult to find the second page of questions. Didn’t understand that there were more questions, so then the feedback got slanted, it didn’t fit with the arrows.’ (Bo, aged 75)

‘That was really great because I can be a bit too quick and I wanted to go back and check, did I really say what I think, and I had.’ (Linda, aged 83)

Most participants had no difficulty navigating the website, but there were exceptions. A few participants expressed the need for a table of contents or an overview of the website structure to assist orientation and a search function. Some experienced difficulties finding their way back to the ARP after clicking on external hyperlinks:

‘Something that is difficult here is when you want to switch from external… It is easy to leave, but it can be difficult to find your way back.’ (Anna, aged 75)

Self-administration mode

The participants were satisfied with self-administration, or they wanted it combined with some kind of in-person support. Those who were satisfied with self-administration thought it enabled autonomy:

‘I am very much of a lone wolf, and for me as a person, it is very important to reach my own decisions.’ (Linda, aged 83)

‘So, as far as I am concerned, it needs to be a personal meeting, or as they say, physical. Because naturally, you often want to ask a follow-up question or you have something to add and this, of course, only applies to me, nothing generally applicable.’ (Kajsa, aged 83)

Usability ratings

The median individual SUS score was 84 (q1–q3; 78–95), and 12 of 14 participants ranked the ARP > 70 on the SUS questionnaire. In general, the rating on the SUS questions indicated that the website was experienced as easy to use without further knowledge or technical support (see ).

Table 2. Results of system usability scale questionnaire single evaluation, N = 14.

Discussion

This study shows that the usability of the novel web-based housing counselling service ARP is satisfactory as assessed by representatives of the target group. The fact that all tasks were performed successfully is a sign of the usability of the website. Comments from interviews showed high user satisfaction regarding website layout and design. The content of the service was perceived as informative, and it generated reflections on housing-related factors and decisions, which is in line with the overall purpose of the ARP. The qualitative findings were supported by the fact that the median SUS score exceeded the level of acceptable usability. However, the study also generated valuable suggestions for optimisation of the content, design, specific functions, and self-administration as the delivery mode, which need to be considered before further evaluation guided by the MRC framework is conducted.

Overall, the ARP content was considered relevant, based on the interviews as well as SUS data. A number of additional relevant topics were suggested for inclusion and may be considered as a means of broadening the content of the ARP. Furthermore, since the development of the ARP is closely linked to the ongoing RELOC-AGE project [Citation41], which focuses on how housing and relocation are associated with active and healthy ageing, new research findings will be integrated into the ARP over time. However, one issue that emerged from criticism expressed by participants in this study concerns whether pictures, films, and the phrasing of some questions in the ARP were sufficiently representative of the diverse target group. Showing nonrealistic, exaggerated, stereotypical, or distorted portraits of older adults is a problem linked to ageism in the media [Citation42–45]. Older adults are a heterogeneous group, and for a web-based housing counselling service to be relevant, it must appeal to a broad range in terms of age, financial and social situation, health status, etc. It is, therefore, necessary to address the representativeness of the ARP and revise it accordingly. With increased relevance for the target group of users, the usability would also be expected to increase [Citation6].

Interview and SUS data indicated high usability with regard to the design of the ARP. The decline in vision, hearing, and psychomotor coordination that becomes more common as people age can have implications for the usability of the internet and websites [Citation46,Citation47]. While we did not specifically aim to include older adults with such functional limitations in our group of participants, we recognise that website design is crucial for good usability and should be tailored to the target group [Citation6]. As the ARP target group consists of older adults, the design features should accommodate these specific characteristics. Although all participants described themselves as completing the tasks successfully, indicating high utility for the target population, it was also reported that computers and tablets were preferred over smartphones as the text size was bigger. Our results indicated that design features such as the layout and colours enhanced usability, but some participants nevertheless found the ARP somewhat complicated, which indicates a possible efficiency deficit. In the usability literature, the terms task performance and error are used as interconnected concepts [Citation6], referring to whether the task is solved in the way intended by the developer. In this study, the tasks were completed, but not with perfect efficiency, as was indicated by errors when the ARP’s specific function for saving answers was misunderstood. Such misunderstandings, as well as other suggestions for easier navigation, indicate that the design features could be further enhanced to improve usability.

The results showed that the participants had mixed opinions, in terms of satisfaction as well as efficiency, about using the ARP in self-administrative mode. Some participants expressed satisfaction with self-administration as it allowed autonomy in the decision process. Others suggested that support should be available for those with less digital skills. All participants owned a smartphone and/or tablet or computer and described their everyday use and varied digital skills, but the differences in digital skills may have affected their experience of the ARP. There is a clear disparity in how adults aged 65 years and older use websites [Citation48,Citation49]. Therefore, we cannot consider older adults as a homogenous user group because the degree of technology experience, proficiency, and adoption varies greatly [Citation50], as does their engagement with digital technology and social media [Citation51]. In Sweden and other parts of Europe, growing numbers of older adults are using the internet [Citation48,Citation49,Citation52], with 90% of people in Sweden aged 66–75 using it frequently or every day, despite some people feeling less comfortable utilising digital services [Citation52]. All participants in our study indicated regular use of the internet, although some rated their confidence lower when using websites, which seems to be representative of the target group. The ARP was constructed as a web-based, self-administered service widely accessible to the older population. However, the digital mode of delivery may also create inequitable access to housing counselling and thus add to digital exclusion. Although high-income countries are more digitalised than middle and lower-income countries, digital exclusion is still noticeable, especially for older adults [Citation53]. Such exclusion means not only that older adults are excluded from participating in the digital realm but also that they miss out on the benefits associated with digital interventions [Citation54]. Reflecting further on risks of exclusion, the population in Sweden includes citizens of many nationalities, speaking different languages [Citation55]. Whereas ARP is currently available only in Swedish, further development and research are needed to determine how alternative modes of delivering the ARP, including other languages, can affect equitable access, reach, and efficiency of web-based housing counselling.

Overall, the ARP was described as useful in creating awareness and reflection regarding housing-related decision-making. Residential reasoning is a complex process where aspects of housing and health and thoughts about the future interact and change over time [Citation19,Citation21,Citation56]. As previous research has indicated, social and family aspects are important in housing-related decision-making in later life [Citation2,Citation24,Citation56]. This was confirmed by our results, as spouses and other family members were mentioned as partners in the residential reasoning process when discussing housing-related decisions. But even for those with a family, there is a lack of support to facilitate informed housing-related decisions. Some respondents suggested that professionals might act as housing counsellors and deliver more objective input. Free-of-charge housing advice is offered by some municipalities in Sweden [Citation57,Citation58], but this is focused on special housing and targets only 3% of people over 60 [Citation59]. For occupational therapists, a broad theoretical foundation creating an understanding of person–environment dynamics provides a basis for interventions focused on how the housing context can enable activity [Citation25]. However, while assistive devices and housing adaptation are common occupational therapy interventions intended to enhance independence in daily activities, improve housing accessibility, and support ageing in place [Citation10,Citation60], these interventions are reactive and implemented once activity limitations have emerged. While housing adaptations and assistive devices remain relevant intervention components for some older persons, the ARP offers an alternative approach. It supports residential reasoning with a focus on ageing in the right place, i.e. recognising that housing-related needs can be met either in the current dwelling or by moving to another dwelling. Thus, the ARP can be seen as a novel proactive approach in contrast to the current reactive occupational therapy practice. Guided by the Swedish code of ethics for occupational therapists [Citation61] and empirical evidence [Citation62], supporting clients in making informed housing-related decisions is a warranted and promising development in occupational therapy for older adults. Expanding the occupational therapy intervention repertoire by including the ARP as a proactive tool for supporting housing-related interventions would also be in line with the development of health-promoting services and the use of digital means of delivering interventions, which have been highlighted as central to integrated care [Citation63].

To address the consequences of the demographic shift towards a more aged population, it is appropriate for policy and interventions to enable independence and participation as a prerequisite for health. Proactive ageing, as discussed by Iwarsson et al. [Citation64], includes preparations for future housing needs as a natural part of the life journey, which is in line with how residential reasoning is an ongoing adjustment and decision-making process. Whereas our study contributes knowledge to the process of development of proactive housing counselling and to its eventual implementation [Citation65], additional studies are needed to determine the optimal mode of delivery and how such an intervention should be evaluated. Bearing in mind that interventions should lead to measurable outcomes [Citation66], future steps in the development of the ARP include the identification of feasible and sensitive primary and secondary outcome measurements [Citation65] and the exploration of its effects in municipal contexts.

Methodological considerations

The design of this study resulted in relatively large amounts of data regarding the content but less on the design, specific functions, and delivery modes of the ARP. This could be a sign of overrepresentation of interview questions about the content. The web service was described as containing a lot of information, which could be another reason why the content was discussed at length. The fact that only one delivery mode was used is a limitation deserving consideration when interpreting the results.

The SUS questionnaire has been evaluated for psychometric properties and translated into several languages [Citation38,Citation67]. The SUS has previously been used in Swedish contexts with minor differences in the phrasing of some of the questions [Citation68,Citation69], but there has been no psychometric evaluation. However, the use of both interviews and the SUS questionnaire, with data from both sources confirming each other, is a notable methodological strength of our study.

In the literature, the recommended number of participants for testing usability ranges from 10 to 20, although varying depending on study-aim, complexity of the product being tested, time and resources, and feasibility [Citation6,Citation33]. In this study, with the continuous recruitment and interview transcription, it became apparent after 10–12 interviews that the described experiences reoccurred. The already scheduled interviews with the last two participants were performed as planned, but no further recruitment attempts were made.

As recruitment was made from both the test municipality and another municipality, some of the information in the Act module did not apply to all participants, possibly creating representation bias. However, to take part in the study, the participants were not required to use the ARPor to make use of the information in the service. The purpose of the study was about the function, usability, and clarity of the web service, rather than the outcome of the ARP as an intervention. Since all participants completed the set of tasks, we considered that the inclusion of participants living outside the test municipality did not limit the results of the study.

Conclusion

The ARP appears to be usable and, thereby, suitable for supporting older adults’ residential reasoning based on informed decisions. Suggested optimisations concern the phrasing of questions and the overall representativeness to enable the ARP to appeal to and be relevant to a diverse ageing population. Some design features warrant revision to alleviate misconceptions and facilitate navigation. The findings of this study constitute an important knowledge base for further development and evaluation of the ARP in authentic municipal contexts.

Declaration of interest

Availability of data

The data sets generated during this study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

Authors MG, SI, and MZ have shared ownership of the ARP, which is under development towards a commercial service.

Author contribution

Frida Nordeström was involved in conceptualisation, data collection and analysis, project administration, validation, and writing (original draft, review, and editing). Marianne Granbom was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, validation, and writing (review and editing). Susanne Iwarsson was involved in acquisition of funding, conceptualisation, and writing (review and editing). Magnus Zingmark was involved in conceptualisation, methodology, validation, and writing (review and editing). All authors read and approved the final manuscript before publication.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahn M, Kwon HJ, Kang J. Supporting aging-in-place well: findings from a cluster analysis of the reasons for aging-in-place and perceptions of well-being. J Appl Gerontol. 2020;39(1):1–18. doi:10.1177/0733464817748779.

- Löfqvist C, Granbom M, Himmelsbach I, et al. Voices on relocation and aging in place in very old age—a complex and ambivalent matter. Gerontol. 2013;53(6):919–927. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt034.

- Golant SM. The Changing Residential Environments of Older People. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, 7th ed. Academic press; 2011. Chapter 15. pp. 207–220.

- Bigonnesse C, Chaudhury H. The landscape of “aging in place” in gerontology literature: emergence, theoretical perspectives, and influencing factors. J Aging Environ. 2019;34(3):233–251. doi:10.1080/02763893.2019.1638875.

- Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, et al. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontol. 2012;52(3):357–366. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr098.

- Tullis T, Albert A. Measuring the user experience. Collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. United States of America: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; 2013.

- Ahn M, Kang J, Kwon HJ. The concept of aging in place as intention. Gerontol. 2020;60(1):50–59. doi:10.1093/geront/gny167.

- World report on ageing and health [Internet]. World Health Organisation (WHO); 2015 [accesed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565042.

- Live well throughout life SOU 2008:113. [Bo bra hela livet SOU 2008:113] [Internet]. Government Offices of Sweden (Regeringskansliet); 2008 [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2008/12/sou-2008113/.

- Zingmark M, Evertsson B, Haak M. Characteristics of occupational therapy and physiotherapy within the context of reablement in swedish municipalities: a national survey. Health Soc Care Commun. 2020;28(3):1010–1019. doi:10.1111/hsc.12934.

- Ninnis K, Van Den Berg M, Lannin NA, et al. Information and communication technology use within occupational therapy home assessments: a scoping review. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;82(3):141–152. doi:10.1177/0308022618786928.

- Rowles GD. Housing for older adults. In: Devlin AS, editor. Environmental psychology and human well-being. London: Academic Press; 2018. pp. 77–106.

- Scharlach AE, Moore KM. Aging in place. In: Bengtson VL, Settersten RA, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. New York, United States of America: Springer Publishing Company; 2016. pp. 407–428.

- Pani-Harreman KE, Bours GJJW, Zander I, et al. Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: a scoping review. Ageing Soc. 2020;41(9):2026–2059. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20000094.

- Wahl H-W. Ecology of Aging. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. Germany: Elsevier Ltd; 2015. pp. 884–889.

- Housing Adaptions Law SFS 2018:222. [Lag om bostadsanpassningsbidrag SFS 2018:222] [Internet]. Swedish Parliament (Sveriges Riksdag); no date [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2018222-om-bostadsanpassningsbidrag_sfs-2018-222/.

- High-Quality and Accessible Healthcare. A Primary Care Reform SOU 2018:39 [God och nära vård. En primärvårdsreform SOU 2018:39] [Internet]. Stockholm: Swedish Government (Regeringskansliet); 2018 [accessed 12 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/85abf6c8cfdb401ea6fbd3d17a18c98e/god-och-nara-vard–en-primarvardsreform_sou-2018_39.pdf.

- Roy N, Dubé R, Després C, et al. Choosing between staying at home or moving: a systematic review of factors influencing housing decisions among frail older adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189266.

- Granbom M, Himmelsbach I, Haak M, et al. Residential normalcy and environmental experiences of very old people: changes in residential reasoning over time. J Aging Stud. 2014;29:9–19. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2013.12.005.

- Li S, Hu W, Guo F. Recent relocation patterns among older adults in the United States. J Am Plann Assoc. 2021;88(1):15–29. doi:10.1080/01944363.2021.1902842.

- Koss C, Ekerdt DJ. Residential reasoning and the tug of the fourth age. Gerontol. 2017;57(5):921–929. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw010.

- Franco BB, Randle J, Crutchlow L, et al. Push and pull factors surrounding older adults’ relocation to supportive housing: a scoping review. Can J Aging. 2021;40(2):263–281. doi:10.1017/S0714980820000045.

- Granbom M, Nkimbeng M, Roberts LC, et al. So I am stuck, but it s OK": residential reasoning and housing decision-making of low-income older adults with disabilities in Baltimore, Maryland. Hous Soc. 2021;48(1):43–59. doi:10.1080/08882746.2020.1816782.

- Nygren C, Iwarsson S. Negotiating and effectuating relocation to sheltered housing in old age: a Swedish study over 11 years. Eur J Ageing. 2009;6(3):177–189. doi:10.1007/s10433-009-0121-0.

- Taylor RR. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Park S, Han Y, Kim B, et al. Aging in place of vulnerable older adults: person–environment fit perspective. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(11):1327–1350. doi:10.1177/0733464815617286.

- Golant SM. Explaining the ageing in place realities of older adults. In: Skinner MW, Andrews GJ, Cutchin MPE, editors. Geographical gerontology: perspectives, concepts, approaches. London: Routledge; 2017.

- Hoh JW, Feng Q, Gu D. Aging in the right place. In: Gu D, Dupre ME, editors. Encyclopedia of gerontology and population aging. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 299–303.

- Granbom M, Szanton S, Gitlin LN, et al. Ageing in the right place—a prototype of a web-based housing counselling intervention for later life. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(4):289–297. doi:10.1080/11038128.2019.1634756.

- Golant SM. The quest for residential normalcy by older adults: relocation but one pathway. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(3):193–205. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.003.

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. Framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions: gap analysis, workshop and consultation-informed update. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(57):1–132. doi:10.3310/hta25570.

- Rubin J, Chisnell D. Handbook of usability testing. How to plan, design and conduct effective test, 2nd ed. USA: Wiley publishing; 2008.

- Lazar J, Feng JH, Hochheiser H. Research methods in human–computer interaction. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: John Wiley Sons Inc; 2010.

- Granbom M, Slaug B, Brouneus F, et al. Involving members of the public to develop a data collection app for a citizen science project on housing accessibility targeting older adults. Citizen Sci Theory Pract. 2023;8(1):22. doi:10.5334/cstp.509.

- Brooke J. SUS: a quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Evaluation In Industry. 1995;189.

- Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2008;24(6):574–594. doi:10.1080/10447310802205776.

- Lewis JR. The system usability scale: past, present, and future. Int J Human–Comput Interact. 2018;34(7):577–590. doi:10.1080/10447318.2018.1455307.

- Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. 2014 [accessed 2022 Dec 02]. Available from: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39517/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf.

- Tullis T, Albert A. Measuring the user experience. Collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. Burlington, United States of America: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; 2008.

- Zingmark M, Björk J, Granbom M, et al. Exploring associations of housing, relocation, and active and healthy aging in Sweden: protocol for a prospective longitudinal mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(9):e31137. doi:10.2196/31137.

- Makita M, Mas-Bleda A, Stuart E, et al. Ageing, old age and older adults: a social media analysis of dominant topics and discourses. Ageing Soc. 2019;41(2):247–272. doi:10.1017/S0144686X19001016.

- Xu W. (Non-)stereotypical representations of older people in swedish authority-managed social media. Ageing Soc. 2020;42(3):719–740. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20001075.

- Markov Č, Yoon Y. Diversity and age stereotypes in portrayals of older adults in popular American primetime television series. Age Soc. 2020;41(12):2747–2767. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20000549.

- Loos E, Ivan L. Visual ageism in the media. In: Nelson TD, editor. Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cham: Springer; 2004. p. 163–176.

- Romano Bergstrom JC, Olmsted-Hawala EL, Jans ME. Age-Related differences in eye tracking and usability performance: website usability for older adults. Int J Human-Comput Interact. 2013;29(8):541–548. doi:10.1080/10447318.2012.728493.

- Wagner N, Hassanein K, Head M. The impact of age on website usability. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2014;37:270–282. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.003.

- König R, Seifert A, Doh M. Internet use among older europeans: an analysis based on SHARE data. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2018;17(3):621–633. doi:10.1007/s10209-018-0609-5.

- Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. A review of internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 2018;20(10):3937–3954. doi:10.1177/1461444818787348.

- Czaja SJ, Weingast SZ. The changing face of aging: characteristics of older adult user groups. Gerontechnology. 2020;19(2):115–124. doi:10.4017/gt.2020.19.2.004.00.

- Quan-Haase A, Williams C, Kicevski M, et al. Dividing the grey divide: deconstructing myths About older adults’ online activities, skills, and attitudes. Am Behav Sci. 2018;62(9):1207–1228. doi:10.1177/0002764218777572.

- The Swedes and the Internet 2022. [Svenskarna och internet 2022] [Internet]. The Swedish internet foundation; 2022. [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/rapporter/svenskarna-och-internet-2022/.

- Lu X, Yao Y, Jin Y. Digital exclusion and functional dependence in older people: findings from five longitudinal cohort studies. E Clin Med. 2022;64:102239. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102239.

- Mubarak F, Suomi R. Elderly forgotten? Digital exclusion in the information age and the rising grey digital divide. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221096272. doi:10.1177/00469580221096272.

- Parkvall M. Sweden’s languages in numbers - Which languages are spoken and by how many [in swedish: sveriges språk i siffror – vilka språk Talas och av hur många]. Stockholm: Språkrådet Morfem; 2015

- Sergeant JF, Ekerdt DJ. Motives for residential mobility in later life. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2008;66(2):131–154. doi:10.2190/AG.66.2.c.

- House and home searching [Söka bostad] [Internet]. Municipality of Gothenburg (Göteborgs stad); no date [accessed 1 november 2023]. Available from: https://goteborg.se/wps/portal/start/bygga-bo-och-leva-hallbart/bostader-och-lokaler/soka-bostad.

- Housing counselling [Bostadsrådgivning] [Internet]. Municipality of Malmö (Malmö stad); no date [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://malmo.se/Bo-och-leva/Bygga-och-bo/Hitta-tomt-och-boende/Bostadsradgivning.html.

- After age 60. A description of older people in Sweden. Demographic reports 2022:2. [Internet]. Statistics Sweden; 2022 [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/publication/47310.

- Lien LL, Steggell CD, Iwarsson S. Adaptive strategies and person-environment fit among functionally limited older adults aging in place: a mixed methods approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):11954–11974. doi:10.3390/ijerph120911954.

- Code of Ethics for Occupational Therapists in Sweden [Internet]. The Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists’s; 2018 [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.arbetsterapeuterna.se/media/1633/code_of_ethics_ot_sweden_2018.pdf.

- Walker E, McNamara B. Relocating to retirement living: an occupational perspective on successful transitions. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60(6):445–453. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12038.

- High-quality and accessible healthcare [God och nära vård] [Internet]. National board of Health and Wellfare [Socialstyrelsen]; 2021 [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/kunskapsstod-och-regler/omraden/god-och-nara-vard/.

- Iwarsson S, Jönson H, Deierborg T, et al. ‘Proactive aging’ is a new research approach for a new era. Nat Aging. 2023;3(7):755–756. doi:10.1038/s43587-023-00438-6.

- Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2061.

- Rychetnik L, Hawe P, Waters E, et al. A glossary for evidence based public health. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2004;58(7):538–545. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.011585.

- Hvidt JCS, Christensen LF, Sibbersen C, et al. Translation and validation of the system usability scale in a Danish mental health setting using digital technologies in treatment interventions. Int J Human–Comput Interact. 2019;36(8):709–716. doi:10.1080/10447318.2019.1680922.

- To procure usability of IoT systems [Säkra användbarhet i upphandling av IoT-system] [Internet]. Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR); 2022 [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://skr.se/download/18.2867e67f185050c7b9f1ecb6/1671107894602/Sakra-anvandbarhet-i-upphandling-av-IoT-system.pdf.

- Rosenfeld JC. System Usability Scale in Swedish [Internet]. 2011. [accessed 1 November 2023]. Available from: https://rosenfeldmedia.com/announcements/sus-svensk-system-usability-sc/.

Appendix 1:

Module overview and chapter description

Introduction page includes three films (4:58, 4:40 and 4:11 min), information about the modules and testimonials.

Think module

Table

Learn

Act

Appendix 2.

Logbook

Logbook part 1

Below are a few tasks we want you to go through on the web service. Use this journal to record your experiences as you go. In the section called Think, there are questions about, among other things, your housing and family situation. Answer the web service’s questions based on how you live today and what your circumstances actually look like. When you are done with the tasks, answer the last questions in the logbook and save them for follow-up. If you have any questions or concerns, please write them down for the follow-up.

Now it’s time to start using Ageing in Right Place!

Task 1:1

Register as a user and log in to the program.

How did you experience registration and login?

What do you think of the introductory text (content, text size, page colouring, etc.) on the first page?

Task 1:2

Watch the three films.

How did you experience the film ‘For those who want to stay’?

How did you experience the film ‘For those who want to move’?

How did you experience the film ‘For you who are a relative’?

Task 1:3

Go to the Think page. Go through all the question pages and, as far as possible, answer the questions according to your own conditions. Click Submit.

What did you think of the questions (number of questions per page, content, answer options, etc.)?

How did you experience answering the questions?

How did you experience the suggestions and recommendations of the website (relevance, meaningfulness, etc.)?

Task 1:4

Go to the Think more. Go through all the question pages and, as far as possible, answer the questions according to your own conditions.

What did you think of the questions (number of questions per page, content, answer options, etc.)?

How did you experience answering the questions?

There are no recommendations in Think more; how did you experience that?

How did you experience Think more when you compare with the questions in Think?

Now that you’ve started watching Ageing in the right place, what’s your first impression of the web service?

Were you able to click on the answers for all the questions?

Did all the pages load as they should?

When you watched the videos, were the captions synced with the audio?

How do you experience the function of being able to save your answers to be able to answer in batches?

Any other questions or concerns?

Now, the first part is finished, and it’s time for a follow-up via video link.

_______________________________________________

Logbook part 2

During the second part of the test, we want you to go through the entire service. You can choose whether you want to do all the tasks in one or more sessions.

Start with the Learn and Act modules. You can go through these modules based on your own circumstances or from a more general perspective, perhaps based on someone you know. Use the journal to record your experiences as you go. When you have completed the tasks described in the logbook, answer the last questions in the logbook.

We also want you to go back to Think and change your answers, for example, that your health has deteriorated. You can imagine yourself in the situation of using the service if your situation looked different than it actually does. How does it affect your experience of recommendations and how you can use Learn and Act modules?

Task 2:1

Start by logging in to your account. Go to the Learn module.

What do you think of the first page (images, content of the different boxes, text size, colour scheme of the page, etc.)?

Task 2:2

Click on the Housing-related finances chapter. Read the text and watch the video.

How did you experience the text?

How did you experience the film?

Task 2:3

Go further on the Housing-related finances. Click on Housing supplement and on to the external pages; there are two links we want you to click on. Once you’ve looked at the external links, click back to Ageing in the right place.

How did you experience moving on to external pages?

How did you experience navigating between external pages and Ageing in the right place?

When you think about all the chapters or sections under the Learn module:

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that were particularly good?

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that you think were less good?

Feel free to think through suggestions for improvements and make a note of them here:

Task 2:4

Go to the Act module. Read the headings of the different chapters.

Based on the headlines, what impression do you get of Act? Are you missing a chapter?

What additional/other services would you like to see more information about?

Task 2:5

Click on the section I want to future-proof my home.

What do you think of the introductory text (content, text size, colour scheme of the page, etc.)?

If you had wanted to future-proof your home, had you benefitted from the information?

Task 2:6

Click the chapter I want to move to another home.

How do you feel about the chapter?

If you would have liked to move to another apartment, how would the information have benefitted you?

When you consider all the chapters in Act:

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that were particularly good?

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that you think were less good?

Feel free to think through suggestions for improvements:

Final Questions

If you think about the web service as a whole, what was good? What was less good?

Is this a web service you would recommend to others? If so, why/why not?

Who do you think would benefit from the service?

Did you fill in all the questions yourself? Did you want help or discuss any issues with another person? if so, who?

What technical equipment did you use to carry out the different tasks (mobile phone, computer, or tablet)? If you’ve tried different equipment, how has it worked?

For each statement, please mark with a cross in the box that corresponds to how you feel about the statement. The number 1 means strongly disagree, 5 means strongly agree.

Now, the second part of the task list is done, and it’s time for the second and final follow-up!

_______________________________________________

Appendix 3.

Interview guide

In-depth questions/follow-up interview for:

Ask questions about age, type of housing, and computer skills.

What year were you born?

What is your highest level of education?

How do you live today?

Condominium

Tenancy

Other, namely

Did you use:mobile phonecomputer ortablet to use the web service?

Task 1:1

Register as a user and log in to the program.

How did you experience registration and login?

First impressions after logging in?

What do you think of the introductory text (content, text size, page colouring, etc.) on the first page?

Task 1:2

Watch the three films.

How did you experience the film ‘For those who want to stay’?

How did you experience the film ‘For those who want to move’?

How did you experience the film ‘For you who are a relative’?

When you watched the videos, were the captions synced with the audio?

Did you find the videos to be meaningful examples from the perspective of the people you think might be interested in this website?

Task 1:3

Go to the Think module. Go through all the question pages and, as far as possible, answer the questions according to your own taste. Click Submit.

What did you think of the questions (number of questions per page, content, answer options, etc.)?

Were you able to click on the answers to all the questions? What did you think of the answer options? did you miss anything?

How did you experience answering the questions?

How did you experience the suggestions and recommendations of the website (relevance, meaningfulness, etc.)?

Task 1:4

Go to Think more. Go through all the question pages and, as far as possible, answer the questions according to your own taste.

What did you think of the questions (number of questions per page, content, answer options, etc.)?

How did you experience answering the questions?

There are no recommendations in Think more; How did you experience that?

How did you experience Think more when you compare with the questions in Think?

Now that you’ve started using Ageing in the right place, what’s your first impression of the web service?

How comfortable was the service to use? What was it like to learn the system/understand the structure of the page? How did you feel that the information was presented on the website?

Were you able to click on the answers for all the questions?

Did all the pages load as they should?

How did you experience graphics and language so far?

How do you experience the function of being able to save your answers to be able to answer in batches? Any other questions or concerns?

Make an appointment for the next interview.

_______________________________________________

Logbook Part 2

Did you use: mobilephone, computer or tablet to use the web service?

Did you do all the tasks at once, or did you split it up? What was it that made you split it up?

Task 2:1

You were instructed to log in to the website again and proceed to the Learn module. What was it like to log back in? No technical worries? Difficult/easy to find the right one?

What do you think about the Learn module (the images, the content of the different boxes, the size of the text, the colour scheme of the page, etc.)?

Task 2:2

Click on the Housing-related finances chapter. Read the text and watch the video.

How did you experience the text?

How did you experience the film?

For whom do you think the film can be a meaningful example?

Task 2:3

Go further in the Housing-related finances chapter. Click on Housing supplement and on to the external pages; there are two links we want you to click on. Once you’ve looked at the external links, click back to Ageing in the right place.

How did you experience navigating between external pages and ‘Ageing in the right place ‘?

When you think about all the chapters or sections under Learn:

What do you think of the different chapters? Do the chapters make sense? Is there anything missing?

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that were particularly good?

Can you give examples of some chapters or sections of chapters that you think were less good?

Feel free to think through suggestions for improvements and make a note of them here:

Task 2:4

Go to the Act module. Read the headings of the different chapters.

Based on the chapter headings, what impression do you get of the Act module? Are you missing a chapter?

Based on the headings, do you think the chapters are meaningful? Is there any chapter missing?

What do you think of the introductory text of the Act module (content, text size, colour scheme, etc.)?

What do you think of the different chapters (content, comprehensiveness, etc.)?

What additional/other services would you like to see more information about?

Task 2:5

Click on the chapter I want to future-proof my home.

What do you think of the introductory text of the chapter (content, text size, colour scheme, etc.)?

If you had wanted to future-proof your home, how would you have benefitted from the information?

Task 2:6

Click on the chapter I want to move to another home.

How do you feel about the overall chapter?

If you had wanted to move to another home, how would you have benefitted from the information?

When you consider all the chapters in the Act module:

Can you give examples of some chapters that were particularly good?

Can you give examples of some chapters that you think were less good?

Feel free to think through suggestions for improvements:

Final questions

If you think about the web service, what was good? What was less good?

Is this a service you would recommend to others? If so, why/why not?

Who do you think would benefit from the service?

Did you fill in all the questions yourself? Did you want help or discuss any issues with another person? If so, who?

What technical equipment did you use to carry out the different tasks (mobile phone, computer, or tablet)? If you’ve tried different equipment, how has it worked?

How satisfied are you with how easy or difficult it was to use the system?

What was easy/difficult with the web service?

What was it like to learn the system?

How convenient was the service to use?

How did you feel that the information was presented on the website?

Were you able to go through all the modules in an efficient way? More or less of any module?

What did you think of the balance between the modules?

This service has been developed with the aim of being helpful for your own reflections on how housing or a move supports people to do what they want and need to do.

Is it a service you would recommend to others?

Is this a service you would consider using if or when you start thinking about your accommodation options?

Do you have any other suggestions for improvement?

Would you have liked to have reminders of tips and suggestions that the website came up with? If so, how?

Did you want help or discuss any issues with another person? If so, who?

How do you experience the function of being able to save your answers to be able to answer in batches?

Is there anything else about the web service that you want to tell us about, something we haven’t talked about?

Inform: After the completion of the study, all accounts will be closed.

______________________________________________________________________