Abstract

Background

In Denmark, stroke represents a leading disability cause. While people with difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADL) due to poststroke cognitive impairments are often referred to occupational therapy, limited knowledge is available on the nature of these services.

Aim/Objective

To explore how Danish occupational therapists describe their practice when addressing decreased ADL ability in people with poststroke cognitive impairments in hospital and municipality settings.

Material and Methods

National, cross-sectorial, web-based public survey.

Results

244 occupational therapists accessed the survey; 172 were included in the analysis. Most respondents could indicate the theory guiding their reasoning; half used standardised assessments. Regarding intervention, restorative and acquisitional models were preferred; specific strategies were identified. Intensity: 30-45 min 3-4 times/week in hospitals; 30-60 min 1-2 times/week in municipalities.

Conclusions

Therapists report to be guided by theory in their reasoning. Standardised assessments are used to a higher extend than previously reported. Still, the results invite critical reflections on correct use of assessment instruments, content and intensity of interventions, and how therapists keep themselves updated.

Significance

The results document the need for practice improvements and may inform the definition of standard care in future trials.

Introduction

Stroke is globally ranked as the third-leading cause of death and disability combined [Citation1]. In Denmark, stroke represents a leading cause of adult disability [Citation2]. Difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADL) after stroke are reported to be more severe in the presence of cognitive impairments [Citation3]. One in two people with stroke suffers from cognitive impairments in the first two weeks after first-ever stroke [Citation4]. In the long term, cognitive impairments are still frequent, even in those with an apparently good neurological recovery [Citation5–8].

Occupational therapists represent one of the major groups of healthcare professionals involved in assessment and intervention focused on enabling occupational performance, including ADL task performance, throughout the whole rehabilitation path after acquired brain injury [Citation9–11]. Still, according to a recent Cochrane review [Citation12], the effectiveness of occupational therapy on ADL task performance and cognitive functions in people with poststroke cognitive impairments is unclear, and additional trials with improved methodology and better descriptions of the delivered interventions are needed. Before initiating a process of developing and evaluating an occupational therapy program addressing decreased ADL ability following poststroke cognitive impairments, more information on current clinical practice may be helpful. While there are descriptions internationally [Citation11,Citation13–21], we identified only one study exploring Danish occupational therapists’ choices of assessment tools to evaluate occupational performance [Citation22], and none regarding occupational therapy interventions addressing decreased occupational performance caused by poststroke cognitive impairments. Thus, there is limited available knowledge on the nature of the occupational therapy services in Danish hospital- and municipality-based rehabilitation settings. Systematically collected knowledge on e.g. types of assessments and interventions, and theoretical frameworks employed may provide insight into the extent to which the currently provided services are complying with the latest research findings and clinical guidelines in the field.

Objective

The objective of the present study was to explore how Danish occupational therapists working in hospital- and municipality-based rehabilitation settings describe their clinical practice patterns when addressing decreased ability to perform ADL in people with poststroke cognitive impairments. The term ‘clinical practice’ covers elements of assessment, intervention, and re-assessment in accordance with occupational therapy frameworks [Citation23,Citation24].

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This study was designed as a national, cross-sectorial, web-based public survey. All licenced occupational therapists directly involved in providing occupational therapy services to people with decreased ADL ability due to poststroke cognitive impairments in hospitals and municipality settings in Denmark were included in the survey population. According to the Danish Association of Occupational Therapists’ membership database, there were 640 therapists working at hospitals (psychiatric hospitals excluded) and 1,155 therapists working in municipality-based rehabilitation centres (incl. home-based rehabilitation), when this survey was conducted [Citation25]. Approximately 80% of the Danish occupational therapists are members of the professional association [Citation26]. The exact size of the survey population remains unknown as no list of occupational therapists working with people with stroke was available.

Data collection methods

A survey questionnaire was developed (EG, EEW) specifically for the stated objective based on occupational therapy frameworks of clinical reasoning and practice models [Citation23,Citation24], the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [Citation27], and similar surveys conducted in other countries [Citation15,Citation16,Citation21]. The questionnaire included a combination of questions with multiple choice and free-text response options. The questions covered the following TIDieR items: why (choice of theoretical framework guiding the clinical reasoning), what (materials, generic intervention models, individualised intervention plan describing specific intervention strategies/techniques to be used), who provides the intervention (professional group), how (modes of delivery), where (types of locations), when and how much (frequency and duration of intervention sessions, their schedule, expected length of the intervention). The questionnaire was divided into the following sections: A) a screening question, B) information on respondents’ education and clinical experience, C) information about respondents’ workplace, and D) clinical practice patterns based on a vignette which described a female stroke survivor experiencing dressing problems due to neglect of the left side of space and body, spatial relation difficulties, self-awareness deficits, and left sided paresis. Dressing practice has been reported as one of the most frequently provided by occupational therapists [Citation13], and, consequently, we expected that respondents would be familiar with addressing difficulties in dressing. The respondents were asked to imagine they had to provide occupational therapy intervention to the stroke survivor described in the vignette, and to answer questions regarding their clinical reasoning, including the development of an individualised intervention plan.

With few exceptions, all questions were compulsory. A pilot version of the questionnaire was tested on a purposive sample of six occupational therapists, three working at hospitals and three working in municipality settings in the Capital Region of Denmark. After minor revisions, the questionnaire was additionally reviewed by an experienced occupational therapy clinical supervisor, a communication specialist, a chief therapist, and one of the authors (CHA). The final version was available in two versions: one for therapists working with inpatients in the early poststroke phase and one for therapists working with stroke survivors in municipality settings.

Survey administration

The survey was conducted on the REDCap® platform – a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases [Citation28] hosted by the Capital Region of Denmark. The survey was conducted using a public link and collected responses anonymously. Public links allow for the possibility of taking the survey multiple times. To prevent multiple participation, respondents were asked to save and return later using the generated personal code in case they had to leave the survey before it was completed.

The survey invitation, including an information sheet and the survey link, was distributed through several channels: a) chief therapists across all Danish regions were approached by e-mail and asked to pass the invitation to all eligible occupational therapists at their institution. Contact information on chief therapists were identified by visiting the websites of hospitals and municipality settings delivering stroke rehabilitation across all Danish regions. This resulted in 35 contacts based at hospitals and 129 contacts in municipalities; b) two professional groups for occupational therapy on Facebook; c) the board of the Danish occupational therapy interest group for neurorehabilitation was asked to forward the survey invitation by e-mail to all their members; and d) the Danish Association of Occupational Therapists shared the survey invitation on their LinkedIn profile.

The survey was released to participants for a two-week period in June 2021. A reminder e-mail was sent to the chief therapists after the first recruitment week.

Ethical considerations

Participation consent was implied by the commencement of the survey (questionnaire section A). Respondents were not asked questions that would reveal their identity. The study was approved by the Knowledge Centre on Data Protection Compliance in the Capital Region of Denmark (P-2020-985, 20-10-2020). The survey invitation contained information about the expected completion time (i.e. 20-30 min, depending on how detailed information the individual respondent was willing to provide). Moreover, we informed that the objective was to chart the current clinical practice, and knowledge on current clinical practice is useful when defining the control intervention in clinical trials.

Data analysis

Data were included in the analysis, if the respondent answered to at least one question regarding their clinical practice patterns in the questionnaire section D. Categorical data were summarised using frequencies and percentages; interval data using mean and standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed, and median and range when not normally distributed. Two of the authors (EG and SSC) went independently through the qualitative data generated by the individualised intervention plans based on the vignette and identified all suggested intervention strategies/techniques. Most disagreements were solved by discussions between these two authors; if agreement was not reached, a third author (CHA) was involved.

Results

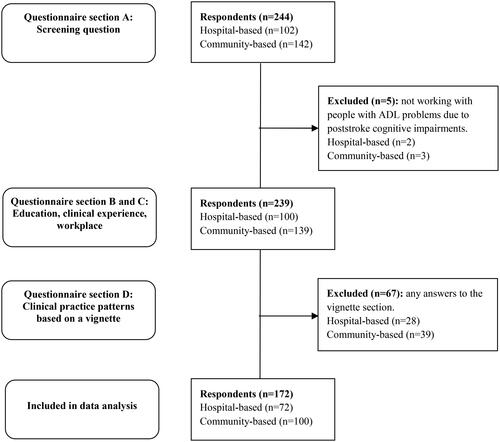

A total of 244 respondents accessed the survey. Of these, five were excluded, as they were not working with people with stroke and PADL problems due to cognitive impairments. Of the remaining 239 respondents, 172 (72 from hospitals and 100 from municipalities) answered at least one question in the vignette section D of the survey, corresponding to a completion rate of 72% ().

Education and clinical experience

Ten percent of the respondents held a higher degree than Diploma or Professional Bachelor’s degree in Occupational Therapy. The participants working in hospitals and municipalities reported a clinical experience of 11 and 12.5 years (median), with nine and ten years (median) of work in stroke rehabilitation, respectively ().

Table 1. Characteristics of survey respondents and their workplaces.

Information about respondents’ workplace

We received responses from all five Danish regions, with the highest proportion of respondents from the Capital Region of Denmark (32% working in hospitals and 36% in municipalities) and the lowest from the North Denmark Region (7% and 12%). Most of the hospital-based therapists worked at acute stroke units and inpatient stroke rehabilitation units; municipality-based therapists worked in home-based rehabilitation and outpatient rehabilitation centres. As reported by more than half of the respondents, the number of occupational therapists working with stroke survivors was six to ten per hospital, and maximum five per municipality setting. Most therapists delivered services to up to ten stroke survivors weekly in both settings. The percentage of work time spent daily on assessment was up to 50% in hospitals and up to 25% in municipalities. In both sectors, the percentage of time spent on delivering intervention varied; the range from 25% to 49% was the most common. The length of a typical rehabilitation stay for stroke patients in hospitals were evenly distributed between one to more than five weeks. In municipalities, more than half of the respondents reported rehabilitation stays ≥13 weeks; only 12% reported rehabilitation stays shorter than nine weeks. Occupational therapists delivered services as part of interdisciplinary teams. Most workplaces provided internships for occupational therapy students. About 60% of the respondents based in hospitals indicated that their workplace was involved in research activities of relevance to their clinical practice with stroke survivors. Research activities were present in 14% of cases in municipalities ().

When asked about which sources of information they used to remain updated on treatment of stroke survivors and how often the used these sources, 73% of the respondents working at hospitals and 84% working in municipalities indicated they each time or often discuss with colleagues. Moreover, 56% of the hospital-based and 46% of the municipality-based respondents each time or often attend courses. Local or national clinical guidelines were each time or often used by 22% and 35% of the hospital-based therapists, and 15% and 23% of the therapists in municipalities, respectively. About 60-80% of the respondents never used database searching or international clinical guidelines for the purpose in question ().

Table 2. Sources of knowledge.

Clinical practice patterns based on a vignette

TIDieR-WHY: Over 90% of the respondents indicated which occupational therapy theoretical framework they would employ; the most frequently used were Powerful Practice, including the Occupational Therapy Intervention Process Model (OTIPM) and the Transactional Model of Occupation (TMO) [Citation23], Enabling Occupation, including the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E), the Canadian Practice Process Framework (CPPF) and the Canadian Model of Client-Centred Enablement (CMCE) [Citation29], and the Model of Human Occupation (MoHO) [Citation24] ().

Table 3. Clinical practice patterns based on a vignette.

TIDieR-WHAT: All therapists would assess the overall quality of the dressing performance by means of observation and/or interview. About 51% of the respondents based in hospitals and 44% based in municipalities indicated they would use standardised assessment instruments for this purpose. Of the ten examples of standardised assessment instruments provided, the Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS) [Citation35,Citation36] was on the top leading position in both hospitals and municipalities. The second most common choice in hospitals was ADL-focused Occupation-based Neurobehavioral Evaluation (A-ONE) [Citation37] and in municipalities the ADL Interview (ADL-I) [Citation38]. Over 90% of the therapists confirmed they would investigate the underlying cognitive impairments; both observation and interview were used. Less than half of the responders would use standardised assessment instruments for this purpose, with the Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) [Citation39] and A-ONE as the most frequently used in hospitals, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [Citation40] and AMPS as the most common choices in municipalities. All therapists would document the intervention effect, with observation as the most used assessment method. Approximatively 32% of hospital- and 40% of municipality-based respondents would evaluate the intervention outcome in a standardised way, with AMPS being the most preferred assessment instrument followed by ADL-I, COPM [Citation41], and the ADL-taxonomy [Citation42] ().

As generic intervention models for the stroke survivor presented in the vignette, both hospital- and municipality-based respondents would primarily select a restorative model for enhancing impaired cognitive functions through various activities and/or an acquisitional model for training of decreased dressing skills. When asked for a description of an individualised intervention plan in enough details that an occupational therapy colleague could step in and deliver the intervention, 68 and 89 responses were received from therapists working in hospitals and municipalities, respectively. Of these, ten percent and 29%, respectively, were invalid, as no details on their clinical practice were provided (questionnaire section D was not completed) (). The specific intervention strategies/techniques suggested by the remaining respondents, including examples, are outlined in . Clothing items, assistive devices, furniture, toilet articles, and mirrors were commonly used as training equipment.

Table 4. Suggested intervention strategies/techniques.

TIDieR-HOW: The most preferred mode of delivery was individual practice provided by an occupational therapist followed by individual practice provided by nursing staff supervised by an occupational therapist, and self-training under supervision of an occupational therapist. Involvement of family members was mentioned by approximately 60% of the hospital- and 80% of the municipality-based respondents ().

TIDieR-WHEN, HOW MUCH: In hospital-settings, the intervention was provided at various frequencies; 44% of the respondents indicated a frequency of three to four times/week. The duration of a typical intervention session was of 31 to 45 min (57% of respondents), and the intervention was commonly delivered for one to two weeks (57%). In contrast, municipalities delivered the intervention one to two times/week (73%) at a duration of 31 to 60 min/session (79%) for about three to 12 weeks (89% of respondents). The intervention sessions were scheduled when it was relevant for the stroke survivor ().

TIDieR-WHERE: The stroke survivor’s room and bathroom were the most frequent locations for delivering the intervention in hospital; in municipalities, the stroke survivor’s home ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to survey how Danish occupational therapists working in hospitals and municipalities describe their clinical practice when addressing ADL task performance problems in people with poststroke cognitive impairments, adding to the body of knowledge on current clinical practice in stroke rehabilitation. Overall, the therapists’ clinical reasoning seems to be guided by occupational therapy theoretical frameworks. Half of the respondents used standardised assessment instruments, and therapists at hospitals spend double as much time on assessments compared with their colleagues in municipalities. The therapists opt for a restorative and/or an acquisitional approach rather than compensation. Discussions with colleagues are the most common ways to remain updated, whereas database searching or consulting international clinical guidelines rarely occurs.

Survey results

Positively, almost all respondents could specify which theoretical frameworks guided their clinical reasoning. However, even though some therapists felt guided by theory in their clinical reasoning, this was not fully reflected in their practice. For example, some respondents reported assessment instruments such as OCS, MOCA and hand assessment as theoretical frameworks. Keeping in mind that these are assessments of body functions and not theoretical frameworks, this might indicate that some occupational therapists follow a medical bottom-up approach in their work rather than a top-down occupation-centred approach.

All respondents except one would perform an assessment of the quality of task performance in terms of independence, effectiveness, and safety. Still, only half would use standardised instruments. AMPS and A-ONE were the preferred assessment instruments at hospitals, and AMPS and ADL-I in municipalities. Some respondents indicated MOCA and OCS, although these are not suitable for the purpose in question. Overall, it is an encouraging development that 51% of the survey respondents indicated they were using standardised assessments in the early stroke rehabilitation phase as opposed to only 9% in the Danish study by Pilegaard et al. from 2011 [Citation22], or 24% in a British audit of dressing practice by occupational therapists working in acute stroke settings from 2018 [Citation16].

Even though almost all OTs would investigate the cognitive impairments underlying the stroke survivor’s dressing difficulties, less than half would use standardised instruments for this purpose. OCS, MOCA, A-ONE and AMPS were the most common choices; A-ONE did not seem to be used in municipalities. Both OCS and MOCA are recommended by national clinical guidelines [Citation43] as screening instruments for impaired cognition. If signs of cognitive impairment are identified, the screening should be followed by an in-depth assessment of cognitive functioning [Citation43]. A-ONE and the Dynamic Lowenstein Occupational Therapy Cognitive Assessment (DLOTCA) [Citation44] are examples of comprehensive, occupation-based assessments of cognitive functioning available for occupational therapists. Surprisingly, some respondents would use AMPS to investigate deficits in cognition. It is important to emphasise that AMPS is suitable for assessment of ADL process skills, which are observable, goal-directed actions a person performs when selecting, interacting with, and using task tools and materials, logically carrying out individual actions and steps of an ADL task, or when modifying performance when problems occur [Citation35]. AMPS cannot be used as assessment of cognitive functioning. It would have been relevant also to include a question regarding to which degree therapists draw upon results from assessments performed by neuropsychologists, when available.

When documenting the outcomes of the intervention, even fewer would employ standardised instruments. Our survey did not address the reasons for not choosing standardised assessment instruments as this topic has been extensively investigated by other studies [Citation14,Citation19,Citation22]. However, not prioritising standardised assessments may conflict with evidence-based practice and invites to reflection [Citation19]. For example, when using non-standardised observation, OTs might miss problem areas [Citation45] and lack normative data to interpret the results [Citation46], requiring additional skills from clinicians [Citation18].

When it comes to intervention, most respondents would choose to target the specific cognitive impairments which affect the stroke survivor’s dressing performance in the context of meaningful ADLs (the restorative model) or/and would attempt to improve the dressing ability directly by training decreased dressing skills (the acquisitional model). One of the cognitive impairments affecting the stroke survivor’s dressing performance was neglect. Several of the strategies currently recommended to manage neglect are suitable to be practiced in the context of ADL training, for example: visual scanning training (the lighthouse strategy) [Citation47–55], visual scanning training combined with upper limb activation (voluntary movements of the affected arm in the neglected side of the space) [Citation47,Citation48,Citation51–54,Citation56,Citation57], and visual scanning training combined with trunk rotation (the trunk rotation is initiated by the non-neglected arm, which moves across the midline of the body to the neglected side) [Citation52–54,Citation56]. Twenty-four of the survey respondents would teach the stroke survivor unspecified visual scanning techniques; only one therapist mentioned the lighthouse strategy specifically (). Although activating the most affected upper limb is the third most mentioned strategy (), it is not clear whether voluntary arm movements in the neglected side of the space are used in combination with visual scanning training as recommended by research. Visual scanning training combined with trunk rotation is not suggested at all. Neuropsychological theory and strategies/techniques have a lot to offer to the field of cognitive rehabilitation [Citation10]. However, it has been shown that clinicians responsible for intervention delivery receive limited training, and clinical practice guidelines do not provide in-depth descriptions of these neuropsychological strategies/techniques [Citation47,Citation55,Citation58,Citation59]. When we analysed the data, we realised it was impossible to make a clear distinction between strategies for cognitive impairments and strategies for motor impairments. Some of the strategies may have even been suggested for both types of impairments. Leaving out motor impairments from the vignette case would have prevented this ambiguity.

Danish clinical guidelines [Citation60] acknowledge that the intensity of therapy should be adjusted according to the individual’s needs. However, in line with international stroke guidelines [Citation47,Citation55,Citation59], it is recommended to aim for 45-minutes sessions several times per week (daily, if possible) for each type of relevant therapy if the stroke survivor can participate. The current recommendations are mainly based on research within motor rehabilitation, though; less is known about the intensity required to induce cognitive improvements after stroke [Citation59]. The results of our study raise concerns regarding the frequency of occupational therapy provided, particularly in the later rehabilitation phases (only one to two times per week in municipality settings). However, this lower frequency might express an adjustment to the needs of the stroke survivor presented in the vignette case, as judged by the survey respondents. According to our survey, occupational therapists working in Danish stroke units typically spend 25% to 74% of their work time on delivering intervention. As a comparison, therapeutic activities occupied between 33% to 63% of the time for occupational therapists working in four stroke rehabilitation units across Europe in 2004 [Citation61]. Not much seems to have changed concerning designated time for intervention during the past almost 20 years; possible reasons have been suggested elsewhere [Citation62].

As a general trend, discussions with colleagues were the most preferred source of information to keep updated; the least common were database searching and consulting international clinical guidelines. These results are in alignment with research findings throughout the past two decades [Citation21,Citation63], and raise concerns regarding evidence-based practice within Danish occupational therapy. The proportion of occupational therapists who base their clinical decision making on research results was estimated to 56% [Citation63] and 61% [Citation21] in previous international surveys.

Methodological considerations

Four main areas of error or bias have been proposed for surveys: coverage of the study population, sampling, non-response bias, and measurement bias [Citation64].

As it was not possible to forward the survey invitation directly to each individual member of the survey population, we cannot be sure that all eligible occupational therapists had an equal chance of participating. Consequently, the presence of some random coverage error cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, the percentage of respondents from each Danish region () corresponds fairly to the population size of that geographical area [Citation65].

The respondents reported a clinical experience of around 10 years within stroke rehabilitation. Consequently, the survey results might be biased against the group of less experienced therapists. A purposive sampling method aiming to reach a more heterogeneous participant group with respect to characteristics such as clinical experience and professional involvement would have strengthened the external validity of our findings. The survey was open for only 2 weeks; a longer period and several remainder e-mails to the chief therapists might have generated additional responders. However, it is questionable whether a longer period would have motivated less experienced therapists to participate.

Despite careful pre-testing of the questionnaire, some measurement bias may be present. One source of measurement bias is wording [Citation64]. Examples of inaccurately worded questions are: Would you document the effect of the dressing intervention? or Which standardised effect instruments would you use to document the effect of the dressing intervention? When analysing the free-text responses, we realised the term ‘to document’ was wrongly perceived by some respondents as documenting each intervention session in the electronic healthcare record rather than evaluating the intervention outcome as intended. Some respondents perceived the term of neuropsychological dysfunctions as including behavioural and emotional dysfunctions, and thus being broader than the intended perceptual and cognitive impairments. However, this inaccuracy is unlikely to have induced measurement bias, as respondents were asked to resonate on how to approach specific impairments and activity limitations described in the vignette. In retrospect, the term ‘perceptual and cognitive impairments’ might have been the most accurate choice.

Surprisingly, less than 30% of the OTs indicated they each time or often use local or national clinical guidelines to remain updated. A possible explanation could be that the questions was perceived as looking up in the documents each time a stroke survivor was treated. This confusion might have been prevented by replacing each time with always in the response scale.

Only 172 of 239 respondents answered at least one question concerning their clinical practice and were included in the data analysis; of these, even fewer (124 respondents) provided a valid description of an individualised intervention plan (). We can only speculate why respondents were less willing to answer questions on their clinical practice based on a vignette; too long questionnaires, competing paperwork and high workloads have been suggested as reasons [Citation16,Citation20,Citation64].

Implication for future research and clinical practice

The present study provides a description of clinical practice patterns from the perspective of therapists themselves and may therefore be affected by social desirability bias. Ideally, these results should be confirmed by studies using data collection methods such as direct observations or healthcare record review.

As implications for clinical practice, we invite clinical occupational therapists, chief therapists, and clinical supervisors and lecturers to critically reflect on the following issues: How can barriers for implementing standardised assessment instruments be overcome in institutional settings? Are standardised assessment instruments used for the correct purpose? Is the content of intervention in accordance with the latest national and international clinical guidelines? How can therapists be supported in accessing and following the latest evidence-based knowledge? Is the provided intervention intensity high enough to expect improvements beyond the spontaneous neurological recovery?

Conclusion

This is the first study to survey how Danish occupational therapists across sectors describe their clinical practice when addressing ADL problems in people with poststroke cognitive impairments. Positively, respondents indicate to be guided by theory in their clinical reasoning. Standardised assessments are used to a higher extend than previously reported. On the other hand, the survey results invite critical reflections on the correct use of assessment instruments, content and intensity of provided intervention, and how therapists keep themselves updated. Finally, the results may inform the definition of standard care in future clinical trials.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of all the survey respondents who made this study possible, as well as the contribution of chief therapists, the Danish Association of Occupational Therapists and the EFS Neurorehabilitering in distributing the survey. Special thanks to Camilla Hole Ringsted, Rikke Levring, and Helene Binau for critically reviewing the questionnaire, and to Christian Gunge Riberholt for valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stark BA, Roth GA, Adebayo OM, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(10):1–16. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0.

- sst.dk/da [Internet]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority]. Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark - sygdomme [Burden of Disease in Denmark]. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2023/Sygdomsbyrden-2023/Sygdomme-Sygdomsbyrden-2023.ashx. [2022, accessed 2024 January 17].

- Stolwyk RJ, Mihaljcic T, Wong DK, et al. Poststroke cognitive impairment negatively impacts activity and participation outcomes a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2021;52(2):748–760. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032215.

- Nys GM, van Zandvoort MJ, de Kort PL, et al. Cognitive disorders in acute stroke: prevalence and clinical determinants. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(5–6):408–416. doi:10.1159/000101464.

- Lipskaya-Velikovsky L, Zeilig G, Weingarden H, et al. Executive functioning and daily living of individuals with chronic stroke: measurement and implications. Int J Rehabil Res. 2018;41(2):122–127. doi:10.1097/MRR.0000000000000272.

- Turunen KEA, Laari SPK, Kauranen TV, et al. Domain-specific cognitive recovery after first-ever stroke: a 2-year follow-up. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24(2):117–127. doi:10.1017/S1355617717000728.

- Kapoor A, Lanctôt KL, Bayley M, et al. ‘Good outcome’ isn’t good enough: cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and social restrictions in physically recovered stroke patients. Stroke. 2017;48(6):1688–1690. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016728.

- Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(9):1288–1294. doi:10.1111/ene.12743.

- Downing M, Bragge P, Ponsford J. Cognitive rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: a survey of current practice in Australia. Brain Impairment. 2019;20(1):24–36. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2018.12.

- Stringer AY. Cognitive rehabilitation practice patterns: a survey of American hospital association rehabilitation programs. Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;17(1):34–44. doi:10.1076/clin.17.1.34.15625.

- Geraghty J, Ablewhite J, Nair R D, et al. Results of a UK-wide vignette study with occupational therapists to explore cognitive screening post stroke. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2020;27(7):1–12. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2019.0064.

- Gibson E, Koh CL, Eames S, et al. Occupational therapy for cognitive impairment in stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;3(3):CD006430. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006430.pub3.

- Richards LG, Latham NK, Jette DU, et al. Characterizing occupational therapy practice in stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(12):S51–S60. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2005.08.127.

- Sansonetti D, Hoffmann T. Cognitive assessment across the continuum of care: the importance of occupational performance-based assessment for individuals post-stroke and traumatic brain injury. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60(5):334–342. doi:10.1111/1440-1630.12069.

- Korner-Bitensky N, Barrett-Bernstein S, Bibas G, et al. National survey of Canadian occupational therapists’ assessment and treatment of cognitive impairment post-stroke. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58(4):241–250. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00943.x.

- Worthington E, Whitehead P, Li Z, et al. An audit of dressing practice by occupational therapists in acute stroke settings in England. Br J Occup Ther. 2020;83(11):664–673. doi:10.1177/0308022620926103.

- Menon-Nair A, Korner-Bitensky N, Ogourtsova T. Occupational therapists’ identification, assessment, and treatment of unilateral spatial neglect during stroke rehabilitation in Canada. Stroke. 2007;38(9):2556–2562. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.484857.

- Goodchild K, Fleming J, Copley JA. Assessments of functional cognition used with patients following traumatic brain injury in acute care: a survey of Australian occupational therapists. Occup Ther Health Care. 2023;37(1):145–163. doi:10.1080/07380577.2021.2020389.

- Stigen L, Bjørk E, Lund A, et al. Assessment of clients with cognitive impairments: a survey of Norwegian occupational therapists in municipal practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(2):88–98. doi:10.1080/11038128.2016.1272633.

- Drummond A, Whitehead P, Fellows K, et al. Occupational therapy predischarge home visits for patients with a stroke: what is national practice? Br J Occup Ther. 2012;75(9):396–402. doi:10.4276/030802212X13470263980711.

- Koh CL, Hoffmann T, Bennett S, et al. Management of patients with cognitive impairment after stroke: a survey of Australian occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56(5):324–331. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2008.00764.x.

- Pilegaard M, Pilegaard B, Birn I, et al. Assessment of occupational performance problems due to cognitive deficits in stroke rehabilitation: a survey…including commentary by morgan MFG. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2014;21(6):280–288. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2014.21.6.280.

- Fisher AG, Marterella A. Powerfull practice. A model for authentic occupational therapy. Fort Collins, CO: Center for Innovative OT Solutions, 2019.

- Taylor R, Taylor R. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation - theory and application. 5th ed. Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2017.

- etf.dk [Internet]. Ergoterapeutforeningen [Danish Association of Occupational Therapists]. Ergoterapeuter i tal [Occupational Therapists in Numbers]. Available from: https://www.etf.dk/Om-ETF/Ergoterapeuter-i-tal. [2023, accessed 2024 January 17].

- etf.dk [Internet]. Ergoterapeutforeningen [Danish Association of Occupational Therapists]. Om Ergoterapeutforeningen [About the Danish Association of Occupational Therapists]. Available from: https://www.etf.dk/mere/om-etf. [accessed 2023 Feb 15].

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348(3):g1687–g1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687.

- project-redcap.org [Internet]. Research electronic data capture; 2022. Available from: https://www.project-redcap.org/.

- Townsend E, Polatajko H. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, and justice through occupation. 2nd ed. Ottawa (Canada): CAOT, 2013.

- Affolter FD. Perception, interaction and language. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2011.

- Chen P, Chen CC, Hreha K, et al. Kessler foundation neglect assessment process uniquely measures spatial neglect during activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(5):869–876.e1. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.10.023.

- Dodds TA, Martin DP, Stolov WC, et al. A validation of the functional independence measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74(5):531–536. doi:10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u.

- Wessels R, De Witte L, Andrich R, et al. IPPA, a user-centred approach to assess effectiveness of assistive technology provision. Technol Disability. 2000;13(2):105–115. doi:10.3233/TAD-2000-13203.

- Kowalchuk Horn K, Jennings S, Richardson G, et al. The patient-specific functional scale: psychometrics, clinimetrics, and application as a clinical outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(1):30–42. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.3727.

- Fisher AG, Bray Jones K. Assessment of motor and process skills. Volume 1: development, standardazation and administration manual. 7th rev. ed. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 2012.

- Fisher AG, Bray Jones K. Asessment of motor and process skills. Volume 2: user manual. 8th ed. Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press, 2014.

- Árnadóttir G. Brain and behavior: assessing cortical dysfunction through activities of daily living. 1990.

- Wæhrens EE, Kottorp A, Nielsen KT. Measuring self-reported ability to perform activities of daily living: a rasch analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):243. doi:10.1186/s12955-021-01880-z.

- Demeyere N, Riddoch MJ, Slavkova ED, et al. The oxford cognitive screen (OCS): validation of a stroke-specific short cognitive screening tool. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(3):883–894. doi:10.1037/pas0000082.

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM). 5th Edition-Revised. Ottawa, Canada: COPM Inc., 2019.

- Wæhrens EE. ADL taxonomien (the ADL taxonomy). Danish edition. Copenhagen: ergoterapeutforeningen, 1998.

- sst.dk/da [Internet]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority]. Anbefalinger til nationale redskaber til vurdering af funktionsevne - hos voksne med erhvervet hjerneskade. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2020/anbefalinger-til-nationale-redskaber-til-vurdering-af-funktionsevne–-voksne-m-erhvervet-hjerneskade [accessed 2024 Jan 17].

- Katz N, Erez ABH, Livni L, et al. Dynamic lowenstein occupational therapy cognitive assessment: evaluation of potential to change in cognitive performance. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(2):207–214. doi:10.5014/ajot.2012.002469.

- Bottari C, Dawson DR. Executive functions and real-world performance: how good are we at distinguishing people with acquired brain injury from healthy controls? OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2011;31(1):S61–S68. doi:10.3928/15394492-20101108-10.

- Wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, et al. Estimating functional cognition in older adults using observational assessments of task performance in complex everyday activities: a systematic review and evaluation of measurement properties. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:335–360. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.024.

- rcplondon.ac.uk [Internet]. Royal College of Physicians. National clinical guideline for stroke. Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/stroke-guidelines. 2016).

- healthquality.va.gov [Internet]. VA/DOD clinical practice guideline for the management of stroke rehabilitation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:1–43.

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals From the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2016;47(6):e98–e169. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000098.

- Teasell R, Salbach NM, Foley N, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: rehabilitation, recovery, and community participation following stroke. Part one: rehabilitation and recovery Following stroke; 6th edition update 2019. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(7):763–788. doi:10.1177/1747493019897843.

- Yang NYH, Zhou D, Chung RCK, et al. Rehabilitation interventions for unilateral neglect after stroke: a systematic review from 1997 through 2012. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:187. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00187.

- Luaute J, Halligan P, Rode G, et al. Visuo-spatial neglect: a systematic review of current interventions and their effectiveness. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(7):961–982. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.03.001.

- Pierce SR, Buxbaum LJ. Treatments of unilateral neglect: a review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(2):256–268. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.27333.

- Ma H, Trombly CA. A synthesis of the effects of occupational therapy for persons with stroke, part II: remediation of impairments. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(3):260–274. doi:10.5014/ajot.56.3.260.

- informme.org.au [Internet]. Stroke Foundation. The Australian and New Zealand clinical guidelines for stroke management; 2021. Available from: https://informme.org.au/en/Guidelines/Clinical-Guidelines-for-Stroke-Management.

- Vahlberg B, Hellström K. Treatment and assessment of neglect after stroke – from a physiotherapy perspective: a systematic review. Adv Physiother. 2008;10(4):178–187. doi:10.1080/14038190701661239.

- Cicerone KD, Goldin Y, Ganci K, et al. Evidence-Based cognitive rehabilitation: systematic review of the literature from 2009 through 2014. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(8):1515–1533. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2019.02.011.

- Bayley MT, Janzen S, Harnett A, et al. INCOG 2.0 guidelines for cognitive rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: what’s changed From 2014 to now? J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2023;38(1):1–6. doi:10.1097/HTR.0000000000000826.

- strokeguideline.org [Internet]. National Clinical Guideline for Stroke for the UK and Ireland. London: intercollegiate Stroke Working Party; 2023. www.strokeguideline.org. [accessed 2023 Aug 11].

- sst.dk/da [Internet]. Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority]. Anbefalinger for tværsektorielle forløb for voksne med erhvervet hjerneskade - apopleksi og transitorisk cerebral iskæmi (TCI) - traume, infektion, tumor, subarachnoidalblødning og encephalopat (version 2); 2021. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2020/Anbefalinger-for-tvaersektorielle-forloeb-for-voksne-med-erhvervet-hjerneskade. [accessed 2024 Jan 17].

- Putman K, de Wit L, Schupp W, et al. Use of time by physiotherapists and occupational therapists in a stroke rehabilitation unit: a comparison between four European rehabilitation centres. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(22):1417–1424. doi:10.1080/09638280600638216.

- Clarke DJ, Burton LJ, Tyson SF, et al. Why do stroke survivors not receive recommended amounts of active therapy? Findings from the ReAcT study, a mixed-methods case-study evaluation in eight stroke units. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(8):1119–1132. doi:10.1177/0269215518765329.

- Bennett S, Tooth L, McKenna K, et al. Perceptions of evidence-based practice: a survey of Australian occupational therapists. Aust Occup Therapy J. 2003;50(1):13–22. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1630.2003.00341.x.

- Shelley A, Horner K. Questionnaire surveys - sources of error and implications for design, reporting and appraisal. Br Dent J. 2021;230(4):251–258. doi:10.1038/s41415-021-2654-3.

- regioner.dk [Internet]. Danske Regioner [Danish Regions]. Om de fem regioner [About the five Danish regions]. Available from: https://www.regioner.dk/om-os/om-de-fem-regioner/. [accessed 2024 Jan 15].