Abstract

Background

The concept of an occupational pattern in occupational therapy and occupational science has evolved with varying definitions, ranging from activity patterns to patterns of daily occupation.

Aims

This study aimed to explore the concept of occupational pattern, develop an updated definition of the concept, and theoretically validate the concept’s definition.

Method

Walker and Avant’s concept analysis method was used, where both theoretical frameworks and peer-reviewed scientific literature were searched and synthesized to clarify and define the concept. Furthermore, seven occupational therapists theoretically validated the concept.

Findings

The analysis included forty-nine references from various research contexts and theoretical perspectives. The synthesis yielded a conceptualization of the concept of occupational pattern, outlining it into three overarching categories: ‘content in an individual’s occupational pattern’, ‘designing an occupational pattern’, and ‘balancing the occupational pattern’.

Implications

An updated operational definition of the multifaceted concept of an occupational pattern now exists, with practical implications for enhancing the education of occupational therapy students and guiding the utilization of the concept. Moreover, it holds significance for instrument development and outcome measurement in research; especially in lifestyle intervention studies within the field of occupational therapy.

Background and aim

Occupational pattern is a concept frequently assessed and studied in both occupational science (OS) and occupational therapy (OT). It is a concept with different names and definitions, and in 2006, Bendixen et al. [Citation1] presented a definition of the concept of ‘occupational pattern’. They defined the concept as including occupations, activities, and actions organized within social and physical contexts over time. Furthermore, this content includes different characteristics, defined as human engagement manifesting in interconnected and parallel occupations, where, e.g. meaningful themes bind activities, motivations, and values into a purposeful narrative [Citation1]. However, despite this concept clarification in 2006, the concept of an occupational pattern is currently defined differently within diverse theoretical descriptions. For instance, the American Association of Therapy Association (AOTA) [Citation2] identifies the concept as performance patterns; i.e. roles, habits, routines, and rituals associated with different lifestyles and used in the process of engaging in occupations or activities. Contexts and time use influence these patterns and can either support or hinder occupational performance [Citation2].

In summary, as theories evolve and concepts are ever-changing, the concept of occupational pattern has also changed and is labelled differently and described in various ways [Citation3]. However, concepts are the basic building blocks of theory construction, and they should be solid and strong enough that there is no misunderstanding regarding what they refer [Citation4]. If a concept is not clearly defined, it gives insufficient guidance for clinical and theoretical reasoning. Furthermore, it is also difficult to assess, as the dimensionality of the construct has not been defined [Citation3]. As the occupational patterns of individuals are commonly assessed within both OT research and practice (cf. Kroksmark et al. [Citation5], Hersch et al. [Citation6], Reynolds et al. [Citation7]), a concept with a clear definition avoids confusion regarding description, explanation, or prediction [Citation3]. Consequently, the various definitions of ‘occupational pattern’ need to be re-explored and re-defined, as the concept is complex and essential within many theoretical frameworks in OT and OS. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore the concept of occupational patterns and to develop an updated definition of the concept for future work related to teaching, assessment development, and research. Furthermore, we intend to theoretically validate the defined concept with occupational therapists.

Methods

Defining a complex concept, such as occupational pattern, requires a structured synthesis of the diverse descriptions available in the literature. Therefore, a concept analysis was conducted, according to the eight steps outlined by Walker and Avant [Citation3]. This method was chosen since it is not merely a linguistic method, but may also be used to explore entire concepts and their defining attributes. All steps were conducted by at least two persons, except for step 3, which was conducted by only one person.

Step 1 is selecting a concept; Step 2 is determining the aims of the analysis. For instance, the chosen concept should be useful to the authors and the intent for conducting the concept analysis should be stated. All aspects of the concept should also be considered [Citation3]. Step 3 is identifying all uses of the concept. In this study, the search was conducted between 2006, the year Bendixen et al. [Citation1] was published, and 2022. The year limitation was chosen since concepts evolve and vary according to current use [Citation3]. It would be irrelevant to search databases before Bendixen et al. was published in 2006 since the paper influenced how the concept of occupational pattern was used. See for the search string and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1. Search string and additional information regarding identifying concept use.

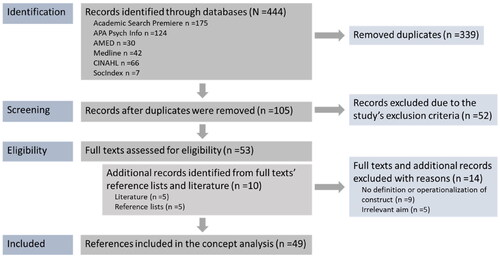

The following databases were searched: Academic Search Premier, AMED, CINAHL, PyschINFO, MEDLINE, and Soc INDEX. All literature found when searching databases was added to RAYYAN, a web application for conducting reviews [Citation9]. Then, duplicates were removed, and titles and abstracts were screened; see for a flowchart regarding the search strategy as well as inclusion and exclusion in different stages.

Figure 1. Flowchart presenting steps for the identification, screening, and eligibility and included scholarship in the concept analysis, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.

Step 4 is determining the defining attributes; i.e. in this step of the analysis, the constellation of characteristics most often associated with the concept is analyzed [Citation3]. Thus, when all the searches had been conducted and the manual searches had been added, the content was listed and compared in MAXQDA.

In Step 5 a model case is created, illustrating the fundamental components of the concept. Moreover, in Step 6 a borderline, related, contrary, or illegitimate case is created; illustrating what the concept is not. Ultimately, Step 7 involves identifying antecedents and consequences; i.e. what happens before and after the concept, and Step 8 defines empirical referents of the concept. Empirical referents are categories or classes of phenomena demonstrating the concept in the real world. It may be useful for instrument creation, facilitating the definition of the concept to be measured [Citation3]. According to Foley and Davis [Citation4], concept analysis transforms abstract ideas into tangible concepts, which makes it a relevant method for operationalizing a construct’s dimensions when designing an instrument.

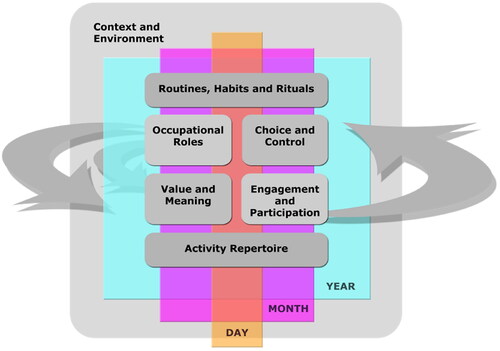

To further strengthen the definition of the concept, we also validated the theoretical construct as a separate step after the concept analysis was conducted. As Boateng et al. [Citation10] assert, this procedure is important for instrument development and uses theoretical construct validation to confirm the identified domains of a concept following its operationalization. Hence, a workshop was performed consisting of seven experts, in this case occupational therapists, with experience within different areas of OT. Furthermore, all participants are also teachers or researchers within the OS and OT fields. The experts were provided with results from this study’s concept analysis, including the concept’s dimensions and the operationalized description of the concept. They were also provided with two figures explaining the concept visually. They were then asked to discuss these different dimensions, as well as the figure, while their feedback was recorded. The feedback was then noted down in bullet points and revised accordingly. Ethical approval exists from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority under Reg No 2022-03690-02.

Results

Selecting a concept, and determining the aims and purposes of the analysis (Steps 1 and 2)

For the purpose of this article, the concept is useful in several ways. First of all, the first and last authors are developing a tool for the assessment of occupational patterns of employees in a specific profession. Thus, a concept analysis is needed to clarify the theoretical aspects and dimensionality of the construct to be assessed. Secondly, clearly defining the concept is important for supporting clinical reasoning as well as for further research and teaching within OS and OT. In addition to contributing to the OS and OT fields, this clarification is highly useful for all authors of this study, given our teaching at an OT programme.

First, an initial literature search of both the concept itself, as well as the instruments used to assess the concept of occupational pattern, was undertaken. The search uncovered diverse descriptions of the concept. Furthermore, the instruments found for assessing occupational patterns targeted different dimensions of the concept. Thus, to date, there is no tool measuring all dimensions of an occupational pattern, despite the concept’s presence within OT and OS.

Identifying all uses of the concept (Step 3)

Different literature review strategies, including database and manual searches, were undertaken. Of the 105 abstracts identified in databases, 53 were retained. Additionally, five articles found in reference lists and five theoretical frameworks or reference literature were added after full-text reading had been conducted (n = 10). Then, 14 full texts were excluded. Altogether, 49 different references were included in the analysis. Key characteristics of the reviewed articles, such as title, aim of the study or article, participants, and references are presented in .

Table 2. Included articles, as well as other references, in the concept analysis.

Determining the defining attributes (Step 4)

Several different labels of the concept were found within OT and OS. Examples include habituation, lifestyle pattern, occupational pattern, patterns of occupations, patterns of daily occupations, activity pattern, or everyday patterns of doing. Activity pattern and occupational pattern were the most-used labels for the concept. However, the term ‘activity pattern’ was also used in other areas, such as physical activity [Citation41,Citation43,Citation60], or circadian rest activity [Citation61]. Thus, according to our findings, we suggest the use of ‘occupational pattern’.

The similarities and differences found describing the concept of occupational pattern resulted in three overall categories: ‘content in an individual’s occupational pattern’, ‘designing an occupational pattern’, and ‘balancing the occupational pattern’. These three categories are presented below, along with their respective sub-categories. The category named ‘content in an individual’s occupational pattern includes: ‘context and environment’ (including the ‘temporal domain’); ‘activity repertoire’; ‘occupational roles’; and ‘routines, habits, and rituals’. The category ‘designing an occupational pattern’ includes how an occupational pattern is designed; i.e. the internal and external forces for doing: ‘occupational engagement and participation’; ‘occupational value and meaning’; and ‘choice and control’. The third category, ‘balancing the occupational pattern’, includes how people balance their occupational pattern. Hence, within life balance, both ‘occupational balance’ and ‘role balance’ exist, and balancing an occupational pattern means managing and redesigning occupational patterns in striving for a meaningful, manageable, healthy, and sustainable way of living. To establish the trustworthiness of our results, all references that were included in the analysis have been used to provide at least one reference example to describe the concept.

Content of the occupational pattern

Contexts and environments in the content of an occupational pattern

Various life contexts, including illness and family members’ health conditions, as well as different life circumstances, influence individuals’ occupational patterns and which types of occupations are added into an occupational pattern, healthy occupations, or the ‘dark sides’ of occupations [Citation13,Citation16,Citation20,Citation25,Citation34–36]. Diverse life contexts and environments simultaneously engage, nurture, and support individuals by providing access to different settings and their contents [Citation62]. These environments refer to temporal, physical, and social environments [Citation57]. The access and usage of the environment influence a person’s occupational patterns and are important regarding what a person does during their day, also incorporating new occupations within the occupational pattern [Citation12,Citation18,Citation53,Citation56]. Thus, there are many potential constraints and facilitators of participation, depending on which context and environment a person exists in, influencing their occupational patterns [Citation21,Citation33]. For example, the physical environment can either encourage or limit access to a diverse occupational pattern [Citation12,Citation14]. Social and cultural environments, along with interactions within one’s social network, mutually shape an occupational pattern, influencing the temporal structure and locations of activities [Citation12,Citation18,Citation53,Citation56].

The temporal domain, a part of contexts and environments

Contexts and environments include a temporal domain, as the occupational pattern includes multifaceted temporal aspects of everyday occupations [Citation27]. Time can be both subjective, referring to conducting a specific occupation, as well as be related to the clock, making it objective. The occupational pattern is also shaped by biological rhythms regarding the sleep–wake cycle, life stages, family situations, and values and beliefs emanating from a person’s social environment. Moreover, places, time of day, and required time for performance influence people’s use of time by being performed under specific circumstances [Citation23,Citation41,Citation42,Citation51,Citation58].

The temporal domain should also be considered within a cultural context [Citation58] and geographical locations and times of the year, since time use may differ depending on location [Citation45]. Certain occupations are also carried out in cycles, like daily chores and tasks, and can be transient due to frequent interruptions and alterations [Citation40]. Hence, several occupational patterns occur over time and space [Citation21], signifying that a person may have different occupational patterns during life. For instance, three perspectives of time have been suggested, existing on macro, meso, and micro levels. The macro perspective refers to a person’s activity repertoire during his or her life course, the meso perspective refers to a person’s activity repertoire as it exists right now, and the micro perspective refers to a person performing specific occupations [Citation58]. Hence, the sum of all occupations, with the individual’s personal use and organization of time, is reflected in a unique pattern of occupations for each individual [Citation27].

It is also influenced by the social context in which a person lives and acts, being integrated with those in their social environment [Citation46].

Metaphors have been used to describe occupational patterns through time. Examples include weaving with warp and weft, orchestrating one’s daily occupations throughout life [Citation46], or as ‘windows on the lifestyles of individuals, cultures, and eras and—over time—as evidence of social change’. Hence, occupational patterns are how occupational therapists and occupational scientists view and explain lifestyles, and how lifestyles can be redesigned [Citation19,Citation28,Citation47,Citation56,Citation57,Citation59,Citation62].

The temporal domain is often informative when it comes individuals’ occupational patterns, utilizing terms like ‘temporal patterns’ or ‘temporal patterns of daily occupations’ to reveal habits, routines, daily activities, the temporal structure of days/weeks, and the sequencing of occupations over time. Additionally, it aids in comprehending aspects like tempo, duration, balance, daily rhythm, and time allocation during occupational performance [Citation23,Citation37,Citation41,Citation42,Citation44]. Temporality may also be experienced differently—e.g. it may seem short in passing, but long when looking back at the situation. Time can also be viewed prospectively as well as retrospectively, including aspects of having a sense of time. Moreover, experiencing flow, and not realizing how much time has passed [Citation21,Citation50]. Hence, the temporal domain and how an occupational pattern changes over time is crucial when studying people’s occupational patterns, as it enhances understanding of the risk of ill health [Citation11,Citation46].

Time and space may constrain or enable occupations. Furthermore, people’s occupations in time and space relate to their experiences of doing. Hence, occupational patterns are described as ‘doing in time’ [Citation46], and the temporal domain is considered the ‘when’ in occupational patterns [Citation56]. Time use is considered important, since it gives insights into the nature and frequency of people’s occupations [Citation28], and differs between genders [Citation27], as well as within gender and age [Citation54]. Time use can also be assessed when identifying strategies for changes in routines to support life goals [Citation54], and also changes during life [Citation54]. Time use is also affected by societal changes during different centuries [Citation23], or may change due to impairment and illness [Citation11,Citation57].

Activity repertoire

Activities can be understood by examining various domains of human occupation, such as work, play, rest, and sleep [Citation39,Citation41,Citation46]. Different taxonomies categorize human actions, with one dividing them into maintaining, working, playing, or engaging in recreational activities. Another taxonomy introduces main categories dominating time and awareness, hidden occupations performed with less attention on a routine basis, but essential for performing main occupations, and a third category—unexpected occupations—which disturb the flow of main and hidden occupations [Citation41,Citation46,Citation58].

The activity repertoire refers to the individual’s whole activity repertoire of both activities and occupations, which they have collected their entire life. The activity repertoire can be viewed in the macro, meso, and micro perspectives, as described above in the temporal domain [Citation58]. In their unique activity repertoire throughout life, an individual will search for activities and keep the occupations that are most important, engaging, socially valuable, or beneficial [Citation58]. Thus, people accumulate their activity repertoires and develop their different occupational patterns according to, e.g. values, contexts, and interests [Citation56], making occupational patterns individual [Citation57].

Occupational roles

Occupations related to roles split persons’ daily and weekly cycles into time frames. However, an occupational pattern changes as new roles are introduced in life. Across a person’s days, weeks, and lives, roles are social spaces which he or she enters, enacts, and exits. In new contexts, also adapts to according to the environment’s rhythm, aligning actions with the social system. This integrates roles into identities, emphasizing some over others, and it also evolves throughout life. A diverse role set is healthier, providing identity, purpose, and structure [Citation57]. One example is the worker role, which has been found to contribute to creating meaning in everyday life and connection to society [Citation49]. Another example is how roles may be experienced as meaningful, contribute to a positive identity, and provide a foothold on conventional daily life, but at the same time have negative consequences in a person’s occupational pattern. Thus, there may be a societal expectation that engaging in the occupation does not fit into the common responsible societal roles [Citation13].

Routines, habits, and rituals

The occupational pattern includes both routines and habits [Citation24] and may be shared with others in within a social environment [Citation56,Citation59]. Routines are a higher order of habits, involving sequencing and combining processes, procedures, steps, or occupations, and provide structure for daily living [Citation59]. Routines are considered regular, repetitive patterns of behaviour or time use, including habits, rituals, and rhythms of life. They reflect familiarity and position individuals within a culture [Citation21], as well as within a social environment, such as families [Citation47]. Thus, most people choose a familiar path by managing time and space in daily life so that they go through the same routines over again [Citation57].

Routines typically change when a person is inflicted with illness or impairments [Citation11], but can also be a source of stability and promote health [Citation21] since they provide consistency [Citation17,Citation24]. The consistency of routines is important while experiencing impairment [Citation25], because routines provide daily structures, and the loss of these routines may be disruptive. Thus, maintaining a steady routine may be difficult when inflicted with illness [Citation59]. Sleep or loss of synchronicity with the routines of others may also disrupt daily rhythms and routines [Citation37]. Hence, routines can be an important component of managing overall health, but may also be damaging to an occupational pattern [Citation59]. When routines that should be flexible and autonomous are affected by change, and a person lacks resources and opportunities, established routines may appear random and unpredictable [Citation21].

Habits are established over time when everyday occupations are woven into habits [Citation56] through conducting routines that organize a person’s daily life. Habits provide familiarity and enable adaptation to the demands of the environment. Most of a person’s occupations in life belong to habits, such as occupations including taking care of ourselves. They help people be where they should be, and do what they should be doing, during daily, weekly, and other life cycles. They also organize time and resources so that less cognitive effort is needed throughout the day [Citation21,Citation57–59]. Habits are performed with little variation in different contexts. However, they are not necessarily performed the same way each time, but can be useful, dominating, or impoverished, and sometimes may be difficult to break [Citation59]. When a habit becomes dominating, it starts interfering with a person’s occupational performance and health. Habit domination may also occur within specific disorders and can be very difficult to change [Citation59]. Thus, useful habits may be developed to manage time and reduce stress, while dominating habits may do the opposite [Citation59]. Thus, habits may also affect persons negatively [Citation57], becoming problematic and jeopardizing well-being. Moreover, illness can introduce new habits linked to disability, which can result in dysfunctional or addictive habits, as well as introduce productive ones [Citation57,Citation59].

Rituals are different from routines, as they include elements of symbolism, reflecting a person’s culture. A strong sense of meaning and identity is included and often signifies a community, or a transition from one state to another, such as child to adulthood or student to graduate. Rituals also exist within families, such as having family picnics or occupations occurring at regular intervals or on certain occasions [Citation59].

Designing an occupational pattern

The internal and external forces for doing is what designs an occupational pattern. Thus, an occupational pattern is every day [Citation19], regular ways of doing, which include complex and subtle elements that interact with each other, residing both within and outside the person in their environments [Citation56]. They are the prerequisite for ‘control and choice’, ‘occupational value and meaning’, as well as ‘occupational engagement and participation’. For example, an occupational pattern is formed by habits, volition, and performance capacity, and motivation influences which choices we make [Citation47]. Choice and control over an occupational pattern have also been linked to motivation to participate in occupations [Citation21], and when facing occupational challenges might also evoke an intrinsic motivational force that leads to occupational adaptation, to feel self-dependent [Citation25]. Thus, people may lose the ability, as well as the motivation, to participate in occupations that usually give life meaning, separating them from their social roles and status [Citation36]. Increased self-efficacy also has a large impact on motivation and goal setting, life choices, and on moving forward in life. Having a sense of competence and efficiency—also known as personal causation—is important for volition and motivation to occupy oneself [Citation49]. If a person shows little motivation, others may need to support their occupational participation [Citation16].

Occupational engagement and participation

Engagement involves initiating and maintaining participation in a particular occupational pattern. It’s a continuous process that varies in nature, intensity, and extent. This concept includes theories like flow, where confidence in one’s ability matches the task’s challenge, and mindfulness, defined as being fully present during an activity. Unlike flow, mindfulness can be felt during everyday tasks, sometimes making time seem slower and leading to feelings of peace or emotional release [Citation21]. Occupational engagement is also closely intertwined with those of others; e.g. when experiencing illness and being dependent on planning and support from others [Citation16], or how parents influence the occupational engagement of their children [Citation53]. Occupational engagement is also determined by the physiological effects of the body, as well as by personal choices [Citation13]. Context and environment influence occupational engagement by shaping acceptable occupations, values, expectations, and boundaries, or limiting access to participation. For instance, alcohol prohibition in some cultural contexts leads to alternative engagement experiences, classifying them as problematic engagement in activities [Citation13].

The experience of participation is subjective and arises from conducting meaningful occupations. This experience is affected by a person’s experiences, and individual beliefs, habits, volitions, and roles, as well as by an enabling or restrictive context [Citation48]. Participation in an occupation may be regarded as enabling growth, as well as recovery when experiencing illness [Citation29]. When people are unable to participate in a variety of meaningful activities because of external constraints or conditions, their ability to lead balanced, healthy lifestyles is compromised [Citation62].

Choice and control

When individuals construct their lives, they exercise choice. These choices are based on resolving the paradox between fully expressing a person’s unique self, versus meeting the demands and expectations of others. Occupational integrity is achieved by resolving this paradox in a way that honours a person’s values, and at the same time allowing a person to live in an interdependent relationship with his or her environment [Citation52]. Hence, individuals carve out social space through their actions. To grasp their occupational choices, it’s crucial to grasp how desires, values, beliefs about capabilities, and meaningfulness intersect with environmental possibilities and limitations [Citation48].

According to Moll et al. [Citation21], people gain a sense of control by choosing and orchestrating their daily occupations by consciously appraising opportunities and shaping their future and identity. Choices, culturally defined within traditions and rituals may vary in emphasis based on cultural context. While Western values prioritize autonomy and empowerment, collectivist societies may prioritize shared societal goals. Despite contextual variations, human rights underscore the importance of choice and access in activities like work, education, and leisure [Citation21].

Occupational deprivation is a state where individuals feel torn beyond their control, potentially leading to a higher risk of life imbalance [Citation62]. It may also be the result of being in a state with too low complexity in the occupational pattern [Citation27]. Occupational deprivation may arise from illness, disrupting a person’s occupational pattern, reducing capacities, and resulting in loss of self-identity and freedom [Citation32]. In addictions and impulse-control disorders, individuals become preoccupied with an activity, dedicating excessive time to obtaining, engaging in, or recovering from it. This preoccupation results in a loss of choice, leading to impaired functioning in daily occupations and the abandonment of previously meaningful activities [Citation13].

Occupational value and occupational meaning

Value has been proposed by Erlandsson and Persson [Citation58] to include three occupational values—concrete value, socio–symbolic value, and self-rewarding value. Concrete values are visible outcomes linked to cultures, such as economic value. Socio–symbolic value allows for emotional expression within occupations, fostering belonging and identification. Self-rewarding value brings immediate joy and pleasure, potentially leading to a state of flow [Citation58].

By valuing and prioritizing daily occupations, individuals may discover certain activities with greater significance, shaping an occupational pattern that aligns better with their needs and prerequisites, ultimately enhancing well-being [Citation58]. Moreover, one’s values have tremendous potential to profoundly shift the culture away from values that are endangering it and towards those that enable survival and flourishing [Citation52]. Emphasizing the significance of valued occupations is crucial in the occupational patterns of individuals affected by impairment or illness [Citation11].

Occupational value is also an important prerequisite for experiencing meaning in life [Citation58]. An important characteristic of an occupational pattern is the extent to which it holds meaning for individuals [Citation21], and how the person values occupational performance [Citation57]. Meaning is typically seen as an internal, subjective process influenced by individual values and history, yet it is also shaped by broader culture and society, as well as by social norms [Citation21]. For many persons, working contributes to a sense of meaning [Citation49], as does being helpful to others and fulfilling important roles [Citation14]. Thus, meaning is derived from participation in activity, and in turn, an occupational pattern may be shaped by the meaning and values that they hold to the individual [Citation21,Citation30]. To underscore the role of occupation in shaping meaning in people’s lives, it can be seen as having dimensions of meaning: doing, being, belonging, and becoming [Citation46]. Meaning may also be adapted and rearranged by people due to life circumstances, forcing them to find new ways to give meaning to their everyday activities [Citation18].

Balancing an occupational pattern

Life balance

Within OS, balance is perceived on a continuum unique to an individual’s assessment of current versus desired placement. It encompasses role balance, occupational balance, life balance, and occupational integrity [Citation21]. It is based on subjective experiences of engagement in everyday activities, as well as on having a perception of control [Citation26]. A static or ideal state of balance does not exist; instead, it is a dynamic interaction between the person’s environment and the occupational pattern, which results in varying degrees of satisfaction and sustainability over time. Thus, this range is considered from the standpoint of how activities meet important needs and are congruent with a person’s values and expectations at any particular point in time [Citation55].

Life balance, or lifestyle balance, describes balance as the extent to which an individual’s unique pattern of occupation in a context and over the life course enables the meeting of needs essential to resilience, well-being, and quality of life. Accordingly, life balance is based on the perspective of an occupational pattern within daily lives and over time [Citation62]. For example, to experience life balance, having time for recreational activities is important since it allows a person to catch his or her breath and gain new energy for challenges in life [Citation58]. Experiencing life balance is the ability to find occupations that simultaneously meet multiple needs in life, which seems important to managing time, energy, and other resources necessary to balance life [Citation62]. Thus, keeping a balanced, personally satisfactory daily rhythm, which enhances participation in society and tunes to the societal rhythms [Citation42] as well as living congruently with one’s meaning and values is essential. The connection between the configuration of occupations and well-being lies in a person designing and living in integrity with their values, strengths, and attributions of meaning, rather than balance itself. The degree to which an individual can align their occupational life with their values determines their sense of balance and well-being [Citation52].

An occupational pattern in a balanced life should enable people to meet important needs, such as biological health and physical safety, contributing to positive relationships, feeling engaged and challenged, and creating a positive personal identity. When engaging in an occupational pattern that addresses these needs, a person will perceive their life as more satisfying, less stressful, and more meaningful or balanced. Additionally, the person needs skills to manage their time, e.g. to create a match between how much time he or she desires to engage in occupations and how much time is actually used to engage in occupations that meet these important needs [Citation59].

Life imbalance, on the other hand, means that an occupational pattern is incongruent with establishing or maintaining physiological health and satisfactory identity; or is mundane, uninteresting, or unchallenging; for example, when a person, due to disability, cannot participate in valued occupations because of personal or environmental barriers [Citation59]. It is also vital to identify known indicators of imbalance since much can be learned about an unhealthy occupational pattern and a person’s lifestyle; examples include workaholism, presenteeism, insomnia, burnout, etc. [Citation28]. Thus, imbalance may result in increased risk and prevalence of the negative consequences of stress [Citation33].

Occupational balance and role balance

Inherent in the concept of occupational pattern is also the concept of occupational balance [Citation56], and to achieve occupational balance, people have been found to change their occupational pattern based on their experiences of meaning and values in occupations by making more conscious choices between different occupations [Citation30].

Occupational balance is not the same as life balance, although they are sometimes used interchangeably [Citation59]. Hassles and uplifts in life have been seen as reflecting experiences in an occupational pattern [Citation40], whereas occupational balance has been seen as a subjective construct with an occupational pattern as its objective counterpart [Citation31]. Occupational balance is commonly described as an individual’s perception of having the right amount and variety of occupations in one’s daily occupational pattern. The ‘right amount’ and ‘variety’ are desired among diverse occupational categories, such as in work, play, leisure, and rest; physical, social, mental, and rest-occupations; relaxing, exacting, and flowing occupations; challenging versus relaxing occupations, occupations meaningful for oneself versus occupations meaningful to others; and occupations intended to care for oneself versus caring for others. Therefore, these different occupations consist of a harmonic mix of activities and resources that are in congruence with the individual’s values [Citation31,Citation46]. It is also important how persons perceive certain aspects of their occupational balance [Citation44]. Occupational balance is culture-dependent, as well as linked to satisfaction and meaning [Citation46]. Unfortunately, not all persons have the opportunity and potential to prioritize and choose valuable occupations that contribute to occupational balance [Citation30].

Having meaningful and valued roles in life has also been found to affect the experience of having occupational balance [Citation46]. Thus, the balancing of roles is an important aspect to consider when regarding roles and balance in life [Citation21]. Also, multitasking is part of an occupational pattern [Citation56]. This has been found to be especially true for women, who often perform parallel occupations, or ‘integrated occupations’ [Citation58], juggling different responsibilities, resulting in little free time [Citation54]. Furthermore, parallel occupations may be integrated and performed simultaneously with other occupations, such as when a person engages in more than one occupation simultaneously; for example, combining addictions and leisure, work, etc.[Citation13].

Creating a model case (Step 5)

A model case was created to illustrate the fundamental components of an occupational pattern, along with how occupational patterns are designed and re-designed. This case shows Jennifer exerting choice and control over her occupational pattern by engaging and participating in occupations that hold personal and communal value and meaning. In doing so, she selects activities from her activity repertoire in line with her desired occupational roles while developing and reinforcing suitable routines, habits, and rituals. The design is influenced by contextual and environmental support and demands.

Every morning, Jennifer would jolt awake to the piercing sound of her alarm clock. Her day would immediately kick into high gear as she rushed to prepare breakfast, and together with her spouse, Sarah got their son Liam ready for school. As Jennifer later embarked on her journey to work, her mind would already be buzzing with the day’s demands. She had a fulfilling yet demanding career as a detective, which often demanded flexibility, multitasking, and dealing with interruptions from colleagues. At least once a week, Jennifer would try to meet up with friends, unless all of them were too busy.

Jennifer truly valued her work, personal life, and relationships, but as years passed, her struggle to balance her various roles became increasingly apparent. She decided to focus on her family, along with her work, which she recognized as important to her community. Still, she found herself forgetting important tasks like packing her gym bag and missing appointments with her dentist. She would often recall chores late in the evening, occasionally having to pack tomorrow’s lunch box right before bedtime.

One day Jennifer realized that by reducing her daily activities to the bare necessities she had lost touch with part of herself. She used to love playing the guitar and exploring nature through hiking and photography. Jennifer remembered discovering these hobbies through friends and longed to reconnect with someone who shared her interests. Recognizing the toll that Jennifer’s career and parental demands had taken on her well-being, Sarah actively supported Jennifer in finding a balance between work, family, and her passions.

Determined to make a change, Jennifer decided to take small steps towards reclaiming her time and reconnecting with her hobbies and friends. She began by setting aside moments each week for her artistic pursuits. Even if it were just a few minutes in the evenings, Jennifer would strum her guitar or snap a few photos in her backyard. She eventually began reconnecting with friends by sending photos or sharing guitar tabs. These interactions enriched her life and brought her a sense of belonging.

As Jennifer reconnected with her hobbies and cultivated her relationships, she found that her overall well-being improved. Carving out time for herself was not always easy, and there were moments of guilt and doubt. With Sarah’s help, Jennifer reminded herself that self-care and self-fulfilment are not selfish, but rather essential parts of a healthy life.

Creating borderline, related, contrary, or illegitimate cases (Step 6)

A borderline case was created to illustrate the disruption of an occupational pattern. This case initially displays all fundamental components of an occupational pattern, until Joseph’s internal forces for doing so are taken from him.

Joseph is a 45-year-old man who is deeply engaged in several roles in life: he’s a dedicated father, a caring brother, a loving husband, and a proud lawyer. In his younger years, he also had an interest in various physical activities and a passion for choir singing which he shared with his wife. However, nowadays Joseph feels as if the demands of his career take precedence, which has made him realize that he has gradually shifted away from his hobbies and interests.

As a father, Joseph also cherishes spending time with his children and actively engaging in their school and extracurricular activities. He has always been highly motivated to be a part of his children’s lives even when they grow older, sometimes even overextending himself in his children’s occupations. Lately, Joseph has started to realize that his time and energy are precious and that he needs to be selective about his engagements. To also carve out time for his interests, Joseph has established a routine. He dedicates late evenings to his love for physical fitness, working out vigorously after everyone has gone to bed. However, the physical activity makes it challenging for him to wind down and fall asleep. This has led to tiredness and a general feeling of imbalance in his life, as he is too tired for other needs in life. In addition to his sleep difficulties, Joseph also has a secret habit he is not proud of, smoking. He keeps this addiction hidden from his family, contributing to a sense of guilt and imbalance.

Tragedy struck one fateful night, when Joseph, fatigued from another restless night, was hit by a bus while crossing the road on his way to work. The accident left him with irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain, with no chance of revival. His family received the devastating news and grappled with the sudden loss of a beloved father and husband.

Identifying antecedents and consequences (Step 7)

When an occupational pattern is balanced, it may lead to a continuum between health and ill health, which impacts the thrive towards a sustainable lifestyle. Hence, the person’s occupational pattern, or the person’s lifestyle, can also lead to an overall balance or imbalance, with long-term consequences on health, well-being, and quality of life [Citation59]. The knowledge procured from an individual’s occupational pattern is considered crucial for occupational therapists, especially when supporting individuals with the desire to change or re-organize their lifestyle or daily occupations to reduce stress due to being forced into a new lifestyle. This highlights the importance of promoting health in their new occupational patterns [Citation19,Citation47]. For example, reflection and recreational occupations can satisfy the needs for the development of personal skills and bring satisfaction and happiness [Citation41]. Additionally, when occupational patterns are dysfunctional, health and well-being are at risk [Citation59], and a person may be perceived as being on the margins of their occupational pattern [Citation13]. Thus, in the interest of promoting health, the complexity of daily occupations needs to be recognized, as they impact health and well-being [Citation19]. In understanding how an individual values a specific occupation it is also important to understand the motive and positive and negative effects on the well-being that an occupation gives a person [Citation58].

Engagement in an occupational pattern is linked to perceived health in working-age women. Manageability, a crucial coping mechanism, and personally meaningful occupations are associated with self-rated health and life satisfaction. Occupational balance is correlated with life satisfaction. The collective experience of engagement in an occupational pattern is associated with perceived health [Citation22]. Thus, a person’s entire occupational pattern is important to consider for the experience of health and well-being [Citation26].

Defining empirical referents (Step 8)

The initial step in instrument creation involves defining the construct, pinpointing its dimensions, and precisely operationalizing both concepts and domains [Citation10,Citation63].

To measure all aspects of a person’s occupational pattern, the content, the design, and the balancing of an occupational pattern need to be considered. Hence, the following dimensions need to be regarded: a person’s activity repertoire, occupational roles, routines, habits, and rituals; as well as the person’s social, physical, and temporal environments. Moreover, occupational value and meaning, choice, and control, as well as occupational engagement and participation, need to be considered. Ultimately, also how an occupational pattern is balanced; i.e. how life, roles, and occupations are balanced needs to be regarded.

There are measures available today that claim to assess people’s entire occupational patterns; however, they only measure parts of the construct. Many of them also focus mainly on parts of the temporal environment [Citation11,Citation23,Citation47], or include several instruments capturing a broader perspective, for example, Eklund et al. [Citation46]. Other aspects that are measured mainly focus on interests or skills [Citation14] or if participants experience motivation and control of their everyday lives [Citation26].

Operational definition and theoretical construct validation of the construct

The participants in the workshop felt satisfied with the operationalized concept descriptions and verified the concept regarding dimensions and descriptions. However, they were not satisfied with how occupational patterns were illustrated when provided with images of the concept. Hence, they provided significant suggestions on how the figure could be improved to incorporate the different dimensions of the concept (see ). Hence, the result from the concept analysis and validation of the theoretical construct suggests a person’s occupational pattern as follows:

Figure 2. Designing an occupational pattern involves considering the occupational possibilities encompassing an ‘activity repertoire’. It also includes the interplay of ‘internal and external forces for doing’, as well as ‘occupational roles’ to initiate routines, habits, and rituals. This design incorporates key dimensions, such as ‘choice and control’, ‘occupational engagement and participation’, as well as ‘occupational value and occupational meaning’, all interacting within an occupational pattern. Note that this figure does not address balance, as this is a separate process when an occupational pattern is balanced.

A person’s occupational pattern is regarded as complex and individual. It is a window into a person’s lifestyle and consists of two parts; first, the occupational pattern, consisting of routines, habits, rituals, occupational roles, and activity repertoires collected through life. Second, it also includes how occupational patterns are designed, throughout life. This is initiated by internal and external forces for doing, i.e., occupational engagement and participation, occupational value and -meaning, and choice and control in life. These internal and external forces for doing are initiated by motivation in life and juggled continuously with the content in a person’s occupational pattern. An individual’s occupational pattern is also in constant interaction with their physical, social, and temporal environment, as well as with contexts in life. Furthermore, environments and contexts can be encouraging and supportive, as well as restraining. See for a visual description of an occupational pattern.

Third, an occupational pattern may be experienced in an eclectic manner, where different aspects of a person’s content and design within their occupational pattern may feel more or less balanced. This balance is viewed from a multidimensional perspective, indicating that even if some parts of an occupational pattern may feel unbalanced, we may still experience overall balance, affecting a person’s continuum of health and well-being. As a result, this eclectic view of life balance ranges from a greater equilibrium that contributes to improved health and well-being to a state of imbalance or dysfunction that may jeopardize a person’s overall health and well-being. It is when a person experiences his or her balance over time as an ideal state that sustainability is possible.

Discussion

This study has explored the various labels and definitions of how the concept of an occupational pattern has been used within OT and OS literature and research articles. The aim was to develop a conceptual definition for future work related to teaching, assessment, and research. We have synthesized the different uses and illustrated the concept in an easy-to-read figure of a complex concept. Furthermore, the concept has been theoretically validated with occupational therapists to ensure clarification of the different conceptual dimensions. During the exploration, we identified several descriptions of the concept and its use. Moreover, we were able to categorize the diverse knowledge of an occupational pattern and identified three distinct categories relating to the concept; i.e. the content, the designing of occupational patterns, and how occupational patterns are balanced.

Regarding the design of occupational patterns, we created the label of the internal and external forces for doing, which we consider a pivotal role in understanding the complex interplay between individuals, their engagement in occupations, and the broader context in which their occupations occur. Hence, this concept analysis sheds light on the significance of shaping occupational patterns. For example, a person’s internal and external forces for doing shape actions and are also intrinsically linked to the person’s performance capacity. Hence, understanding a person’s internal and external forces for doing is essential in the field of OT, as they influence occupational performance, choices, and have a profound impact on the person’s well-being. Recognizing this intricate interplay between these forces allows for more effective intervention for people with ill-health, disability, or illness.

One of the aims of this study was to utilize the concept of occupational patterns to develop an assessment tool. This procedure also involves describing the construct to be evaluated and encompassing all its dimensions. Within OT and OS, there are numerous instruments that measure different dimensions; i.e. the different domains of the construct ‘occupational pattern’. However, none of them seem to assess the entire construct of an occupational pattern. When trying to assess a person’s occupational pattern, the lack of a consistent definition makes it challenging to pinpoint precisely which aspects of an occupational pattern are being assessed. With the adoption of a clearly defined operationalized construct, studies can now more explicitly state which specific aspect of an occupational pattern is being investigated. This also paves the way for greater clarity and precision in research efforts, according to Walker and Avant [Citation3] and Boatang et al. [Citation10].

As the concept of occupational pattern incorporates various separate dimensions, we have only begun to scrape the surface of what constitutes an occupational pattern. Hence, there is a need for a more thorough concept analysis of the different dimensions in the content, design, and balancing of occupational patterns. This warrants further investigation. For instance, when performing activities becomes part of a person’s occupational pattern, how often must they be repeated, and how predictable must they be to be regarded as an occupational pattern? This calls for more discussion and research. Moreover, the findings of this concept analysis also propose a more eclectic view of life balance, where life balance does not only exist on a continuum between two poles of balance and imbalance, or health and ill-health. Instead, it is a state of experiencing different elements as dynamic interactions between all the content and elements of design in a person’s occupational pattern. Hence, the concept is complex and multifaceted, and as such, we propose the concept of life balance to mean that certain dimensions in an occupational pattern may be experienced as balanced or imbalanced, not necessarily leading to health or ill-health. However, when all dimensions are experienced as balanced, it may promote sustainability in a person’s lifestyle. The connection between experienced balance and the possibility of sustainability in life warrants further investigation. Furthermore, future studies should focus on validating our definition of the concept, as the foundations of this study can be used to develop future instruments measuring people’s lifestyles in their specific context. As Walker and Avant [Citation3] suggest, a concept is never fixed in time. Thus, we welcome a debate on our conceptual definition of ‘occupational pattern’, as well as an urge for more research on fundamental concepts within an occupational pattern.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations that should be taken into account. First, not all the available literature in the OS and OT fields was included in the analysis. To address this, we made an effort to incorporate findings from different sections of articles, including the background, to identify multiple definitions of the same concept. We also conducted manual searches of various theoretical frameworks to discover additional definitions. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge this as a limitation, particularly considering that the majority of the research identified in databases and the additional references obtained is based on a Western perspective, including only a few studies from other cultures. This highlights the need for future research to include a broader cultural perspective on an occupational pattern, and the absence of such perspectives should be recognized as a limitation of this study.

Second, it is important to address the limitations of our search string. We encountered challenges in finding relevant subject terms across different databases, which led us to use a free-text search string. To mitigate this issue, we conducted a test search to identify various labels and terminology associated with the concept, ensuring comprehensive coverage in our search. However, despite our efforts, some additional words surfaced when the final search had been conducted, e.g. lifestyle patterns and everyday patterns of doing. Even though the search string managed to find these articles it cannot be excluded that there is a possibility that some articles may have been overlooked in this concept analysis. However, this was also one reason for our choice to carefully examine reference lists of the articles and manually add a few additional references to lessen the effects of this limitation. Additionally, we conducted a theoretical construct validation to further address this potential limitation in our search strategy.

Conclusion and clinical implications

This study presents an operational definition that encompasses multiple dimensions of the concept of occupational pattern. A person’s occupational pattern is a complex and individual representation of their lifestyle, encompassing routines, habits, rituals, occupational roles, and activity repertoires acquired over time. It is influenced by internal and external forces, such as motivation, occupational engagement, participation, value, meaning, choice, and control in life. Additionally, this pattern is in continuous interaction with physical, social, and temporal environments, which can either encourage or constrain it. An occupational pattern can be experienced eclectically, with varying levels of balance, viewed holistically. Even if certain aspects feel unbalanced, an overall sense of balance can impact the continuum of health and well-being, ranging from enhanced equilibrium contributing to well-being to a state of imbalance jeopardizing overall health.

The implications of this study are both practical and theoretical. From a practical standpoint, the findings have relevance in the teaching of OT to students in bachelor’s programs, where it is crucial to have a clear understanding of the various concepts used within the field. The results of this study can serve as a guide for the utilization and clarification of the concept. Additionally, the study holds practical and theoretical implications in the development of instruments that assess individuals’ lifestyles from an OT and OS perspective. Furthermore, the study has implications for research, where there is a need to measure outcomes when conducting, for example, lifestyle intervention studies.

Author note

The Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Umeå University, Sweden sponsored data collection and preliminary analysis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants taking part in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bendixen HJ, Kroksmark U, Magnus E, et al. Occupational pattern: a renewed definition of the concept. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:3–10.

- American Association of Occupational Therapy. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process—fourth edition. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74(Supplement_2):7412410010p1–7412410010p87. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001.

- Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. 6th ed. New York (NY): Pearson; 2019.

- Foley AS, Davis AH. A guide to concept analysis. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017;31(2):70–73. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000277.

- Kroksmark U, Nordell K, Bendixen HJ, et al. Time geographic method: application to studying patterns of occupation in different contexts. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:11–16.

- Hersch G, Hutchinson S, Davidson H, et al. Effect of an occupation-based cultural heritage intervention in long-term geriatric care: a two-group control study. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66(2):224–232. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2012.002394.

- Reynolds S, Bendixen R, Lawrence T, et al. A pilot study examining activity participation, sensory responsiveness, and competence in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(11):1496–1506. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1173-x.

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020 [computer software] [Internet]. Berlin: VERBI Software; 2019. Available from: maxqda.com

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, et al. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149.

- Yavuz Tatlı İ, Semin Akel B. A controlled study analyzing the temporal activity patterns of individuals with stroke compared to healthy adults. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82:288–295.

- Niva B, Skär L. A pilot study of the activity patterns of five elderly persons after a housing adaptation. Occup Ther Int. 2006;13(1):21–34. doi: 10.1002/oti.21.

- Kiepek N, Magalhaes L. Addictions and impulse-control disorders as occupation: a selected literature, review and synthesis. J Occup Sci Aust. 2011;18:254–276.

- Cipriani J, Faig S, Ayrer K, et al. Altruistic activity patterns Among long-term nursing residents. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2006;24:45–61.

- Orban K, Vrotsou K, Ellegård K, et al. Assessing the use of a portable time-geographic diary for detecting patterns of daily occupations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2022;29(4):293–304. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1869824.

- Tsunaka M, Chung JC. Care-givers’ perspectives of occupational engagement of persons and dementia. Ageing Soc. 2012;32:543–560.

- Sinclair C, Meredith P, Strong J. Case formulation in persistent pain in children and adolescents: the application of the nonlinear dynamic systems perspective. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81:727–732.

- van Nes F, Jonsson H, Abma T, et al. Changing everyday activities of couples in late life: converging and keeping up. J Aging Stud. 2013;27(1):82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.09.002.

- Erlandsson L-K. Coaching for learning – supporting health through self-occupation-analysis and revision of daily occupations. WFOT Bull. 2012;65:52–56.

- Cederlund R, Thorén-Jönsson A-L, Dahlin LB. Coping strategies in daily occupations 3 months after a severe or major hand injury. Occup Ther Int. 2010;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/oti.287.

- Moll SE, Gewurtz RE, Krupa TM, et al. “Do-Live-well”: a Canadian framework for promoting occupation, health, and well-being: « Vivez-Bien-Votre vie » : un cadre de référence. Can J Occup Ther. 2015;82(1):9–23. doi: 10.1177/0008417414545981.

- Håkansson C, Lissner L, Björkelund C, et al. Engagement in patterns of daily occupations and perceived health among women of working age. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16(2):110–117. doi: 10.1080/11038120802572494.

- Alsaker S, Jakobsen K, Magnus E, et al. Everyday occupations of occupational therapy and physiotherapy students in scandinavia. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:17–26.

- Häggblom-Kronlöf G, Hultberg J, Eriksson BG, et al. Experiences of daily occupations at 99 years of age. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(3):192–200. doi: 10.1080/11038120601124448.

- Ammann B, Satink T, Andresen M. Experiencing occupations with chronic hand disability: narratives of hand-injured adults. Hand Ther. 2012;17:87–94.

- Erlandsson L-K, Carlsson G, Horstmann V, et al. Health factors in the everyday life and work of public sector employees in Sweden. Work Read Mass. 2012;42:321–330.

- Erlandsson L, Eklund M. Levels of complexity in patterns of daily occupations: relationship to women’s well-being. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:27–36.

- Christiansen CH, Matuska KM. Lifestyle balance: a review of concepts and research. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:49–61.

- Soeker MS. Occupational adaptation: a return to work perspective of persons with mild to moderate brain injury in South Africa. J Occup Sci. 2011;18:81–91.

- Hovbrandt P, Carlsson G, Nilsson K, et al. Occupational balance as described by older workers over the age of 65. J Occup Sci [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://proxy.ub.umu.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-60606-001&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Dhas BN, Wagman P. Occupational balance from a clinical perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2022;29(5):373–379. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1865450.

- Wells SA. Occupational deprivation or occupational adaptation of mexican americans on renal dialysis. Occup Ther Int. 2015;22(4):174–182. doi: 10.1002/oti.1394.

- Stein LI, Foran AC, Cermak S. Occupational patterns of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: revisiting matuska and christiansen’s model of lifestyle balance. J Occup Sci. 2011;18:115–130.

- Holthe T, Thorsen K, Josephsson S. Occupational patterns of people with dementia in residential care: an ethnographic study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(2):96–107. doi: 10.1080/11038120600963796.

- Höhl W, Moll S, Pfeiffer A. Occupational therapy interventions in the treatment of people with severe mental illness. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(4):300–305. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000339.

- Odawara E. Occupations for resolving life crises in old age. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:14–19.

- Pemberton S, Cox D. Perspectives of time and occupation: experiences of people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:488–503.

- Keptner KM. Relationship between occupational performance measures and adjustment in a sample of university students. J Occup Sci. 2019;26:6–17.

- Sernheim Å-S, Hemmingsson H, Lidström H, et al. Rett syndrome: teenagers’ and young adults’ activities, usage of time and responses during an ordinary week – a diary study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27:323–335.

- Erlandsson L-K. Stability in women’s experiences of hassles and uplifts: a five-year follow-up survey. Scand J Occup Ther. 2008;15(2):95–104. doi: 10.1080/11038120701560467.

- Björklund C, Gard G, Lilja M, et al. Temporal patterns of daily occupations among older adults in Northern Sweden. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:143–160.

- Eklund M, Leufstadius C, Bejerholm U. Time use among people with psychiatric disabilities: implications for practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32(3):177–191. doi: 10.2975/32.3.2009.177.191.

- Yu M-L, Ziviani J, Baxter J, et al. Time use differences in activity participation among children 4–5 years old with and without the risk of developing conduct problems. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.013.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson L-K, Leufstadius C. Time use in relation to valued and satisfying occupations among people with persistent mental illness: exploring occupational balance. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:231–238.

- McNulty MC, Crowe TK, Kroening C, et al. Time use of women with children living in an emergency homeless shelter for survivors of domestic violence. OTJR Occup Particip Health. 2009;29:183–190.

- Eklund M, Orban K, Argentzell E, et al. The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance: applications within occupational science and occupational therapy practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24(1):41–56. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2016.1224271.

- Orban K, Edberg A-K, Erlandsson L-K. Using a time-geographical diary method in order to facilitate reflections on changes in patterns of daily occupations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(3):249–259. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2011.620981.

- von Post H, Wagman P. What is important to patients in palliative care? A scoping review of the patient’s perspective. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1378715.

- Liljeholm U, Bejerholm U. Work identity development in young adults with mental health problems. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(6):431–440. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2019.1609084.

- Larson E, von Eye A. Beyond flow: temporality and participation in everyday activities. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(1):152–163. doi: 10.5014/ajot.64.1.152.

- Erlandsson L-K. Fresh perspectives on occupation: creating health in everyday patterns of doing. N Z J Occup Ther. 2013;60:16–24.

- Pentland W, McColl MA. Occupational integrity: another perspective on “life balance”. Can J Occup Ther. 2008;75(3):135–138. doi: 10.1177/000841740807500304.

- Lynch H. Patterns of activity of irish children aged five to eight years: city living in Ireland today. J Occup Sci. 2009;16:44–49.

- DeLany J, Jones M. Time use of teen mothers. OTJR Occup Particip Health. 2009;29:175–182.

- Matuska KM, Christiansen CH. A theorethical model of life balance and imbalance. In: Life balance: multidisciplinary theories and research. 1st ed. New York (NY): Slack and AOTA Press; 2009.

- Townsend E, Polatajko H. Enabling occupation II advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. 2nd ed. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2013.

- Wook Lee S, Kielhofner G. Habituation: patterns of daily occupation. In: Taylor R, editor. Kielhofners model of human occupation. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Erlandsson L-K, Persson D. The ValMO model – occupational therapy for a healthy life by doing. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2020.

- Matuska KM, Barrett K. Chapter 18: patterns of occupation. In: Boyt Schell BA, Gillen G, Willard HS, editors. Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy. 13th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019. p. 212–222.

- Kratz AL, Schepens SL, Murphy SL. Effects of cognitive task demands on subsequent symptoms and activity in adults with symptomatic osteoarthritis. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(6):683–691. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.008540.

- Saito Y, Kume Y, Kodama A, et al. The association between circadian rest-activity patterns and the behavioral and psychological symptoms depending on the cognitive status in japanese nursing-home residents. Chronobiol Int J Biol Med Rhythm Res. 2018;35:1670–1679.

- Matuska KM, Christiansen CH, editors. Life balance multidisciplinary theories and research. Johanneshov: MTM; 2014.

- Benson J. Developing a strong program of construct validation: a test anxiety example. Educ Meas Issues Pract. 1998;17:10–17.