Abstract

Aims

To analyse the measurement properties of the Spanish version of the COPM (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure) in older adult rehabilitation inpatients.

Method

A sample of 172 users from 17 inpatient care facilities for older adults (47% nursing homes) participated in a quantitative prospective study. We examined validity by correlating the COPM with the Barthel Index (BI), the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (IADL), the EuroQol-five domains-three level questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L), and the Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire (CCRQ) and by examining associations with demographic variables. Reliability was evaluated through test-retest and responsiveness through differences in change scores in two types of care facilities.

Results

Participants prioritised 637 occupational performance problems, mainly in the area of self-care (70.5%). The COPM scale scores were significantly correlated with BI, IADL, EQ-5D-3L (except the pain dimension), and CCRQ (except the family involvement and continuity dimensions). COPM scores did not show statistically significant differences concerning educational level. Regarding reliability, high test-retest correlations were obtained (>.80). Nursing home users showed less responsiveness to rehabilitation than other users (change score < 2 vs. > 2 points).

Conclusion and significance

The Spanish COPM provides satisfactory measurement properties as a client-centred instrument in older adult rehabilitation inpatient.

Introduction

In recent years, a person-centered practice has been emphasised within the health system, involving the participation of the client themselves in their own treatment and rehabilitation process [Citation1]. Since the vision of the Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021-2030) [Citation2], as well as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Citation3], the development and maintenance of the functional abilities of older adults has been a priority that goes beyond a rehabilitation focused on dysfunction. For this reason, the new definition proposed by the WHO defines rehabilitation as a ‘set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions, in interaction with their environment (WHO, 2020; p.1)’ [Citation1]. It implies attending to the personʼs needs, considering personal characteristics such as age, pathology, and personality, along with the social, physical, or cultural environment in which they live [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5]. In this sense, effective rehabilitation needs to include both a proactive, individualised attention plan and an assessment design, all of which should take place within a collaborative process between the professional and the client. This process should establish significant intervention aims that are focused on the person [Citation5]. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), proposed in 1994 by Law et al. [Citation6], is a suitable response to these requirements.

The COPM is a standardised instrument based on the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance. In this model, the central domain is occupation, and it has client-centred practice as a fundamental principle [Citation7,Citation8]. The model focuses on the interaction of the person, the environment, and the occupation, which gives rise to occupational performance. Occupational performance is considered optimal when the environment, the skills, and the abilities of the person are compatible with the demands of the occupation or activity. An interruption in any of the areas will interfere with performance and quality of life.

The COPM is designed to help users identify and prioritise their own significant occupational performance problems, in addition to evaluating changes in their perception of improvement over time. It provides a client-reported measure of performance (COPM-P) and a client-reported measure of satisfaction with performance (COPM-S) [Citation9,Citation10] regarding the occupational problems established by the person. The COPM is of value to the rehabilitation team (RT) in reinforcing the client-centred practice model, which focuses on a partnership that enables the design of assistance aims and an intervention plan in line with the values, needs, and identity of each individual [Citation7,Citation11–13].

The COPM is an instrument that is widely used by occupational therapists and multidisciplinary teams throughout the world [Citation10,Citation11,Citation14]. Its psychometric properties have been extensively studied with satisfactory results at different types of health facilities and among different types of users [Citation12,Citation15]. Evidence has been provided of its validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change in older adults with varying diagnoses, such as stroke [Citation14], depression [Citation16], hip fracture [Citation17], osteoarthritis [Citation18,Citation19], chronic pain [Citation20,Citation21], and rheumatic conditions [Citation19,Citation22–24]. Likewise, satisfactory results have been reported in rehabilitation services [Citation25,Citation26]. Although the psychometric properties of the COPM have been backed up by numerous studies, as mentioned above, several aspects of this instrument have not been addressed or have unclear results [Citation27].

Whilst some studies refer to the criterion validity of the COPM scores [Citation21,Citation28,Citation29], their evidence cannot be interpreted in terms of the test-criterion relationship as defined by psychometric standards [Citation30]. However, other validity evidence can be given, based on the study of the network of relationships expected between the COPM scores and other constructs and variables. In this sense, the indicators of functionality and of the health-related quality of life construct have been previously justified for studying the convergent validity of COPM scores [Citation12,Citation17,Citation31–33]. Two of the instruments widely used by health professionals for the clinical assessment of functionality are the Barthel Index (BI) [Citation34] and the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [Citation35]. Results from various studies indicate a stronger association between the COPM-P and the IADL scale (r = 0.55-0.62) compared to that between the COPM-P and the BI (r = 0.22) [Citation17,Citation31,Citation36]. With regard to the health-related quality of life construct, there is evidence of convergent validity when studying the relationship between COPM and EuroQol-D5-3L scores [Citation37]. In these studies, a moderate relationship has been observed between COPM-P and the dimension titled’ activities’ (r= −0.35-−0.36), and with that of global perception of health (r = 0.27-0.23) of EuroQol-D5-3L [Citation24,Citation32]. These results are consistent with the expected network of relationships between constructs that assess functional ability. However, the use of external measures to study convergent validity in person-centredness perceived by the person receiving a rehabilitation intervention is scarce. To fill this gap, in the present study we have used the Spanish version of the Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire (CCRQ-e) [Citation38].

The COPM is designed to be used with people with different levels of development and different physical, cognitive, and psychosocial conditions [Citation15,Citation16,Citation27,Citation29], and the manual does not establish restrictions in relation to educational level [Citation10]. Nonetheless, different studies refer to the difficulty of administering the COPM to older people with cognitive difficulties or poor insight [Citation9,Citation12,Citation39]. Educational level has been linked to variations in administration time [Citation40], but the theoretical framework of the COPM would lead one to expect that performance and satisfaction scores are unrelated to educational level. In terms of the relationship between the COPM and the underlying problem that leads to a rehabilitation intervention, differences have been detected both in the performance and satisfaction scores and in the prioritisation of aims in some occupational performance areas [Citation19,Citation40–44]. Some authors attribute these differences to age or type of service, in addition to the underlying diagnosed problem [Citation16,Citation32,Citation45,Citation46].

In terms of reliability, we have only found one study of older adults that provides evidence of the test-retest reliability of the COPM scores in rehabilitation, with satisfactory results (r ≥ 0.80) [Citation47]. Other studies have included adults and older adults with different diagnoses [Citation22,Citation23,Citation31,Citation48–51], obtaining moderate stability for identified problems, and high stability for performance and satisfaction scores [Citation22,Citation23,Citation31,Citation47,Citation48,Citation50].

Regarding responsiveness, the application procedure of the COPM is designed to detect clients’ perceived change in performance and satisfaction after the intervention, in comparison to before it, always considering that each intervention is planned in an individualised manner and guided by the daily activities that are relevant to each patient. The original COPM manual indicates that a change score of 2 points or more (out of 9) between assessment and reassessment measures is clinically relevant [Citation9]. This criterion has been used in multiple studies for assessing the responsiveness of COPM scores in older adults, with satisfactory results in most cases [Citation18,Citation24,Citation28,Citation42,Citation44]. However, these studies do not put forward a clear hypothesis concerning the expected change in performance perceived by the older adult undergoing a rehabilitation intervention that is basically designed for maintenance, which is what predominates, for example, in nursing homes in Spain. Some authors use the term ‘construct responsiveness’ to encompass the extent to which changes in COPM scores are related to changes in other measures [Citation20,Citation52]. In this sense, the changes in COPM-P showed significant correlations with the domains of other instruments related to activities, and not with the domains related to impairment and to social and emotional behaviour [Citation52]. To the best of our knowledge, the psychometric properties of scores for the Spanish version of the COPM have only been analysed in one study. The study was conducted among people with metacarpal osteoarthritis, with satisfactory results [Citation18].

The aim of our study was to analyse the measurement properties of the Spanish version of the COPM in older adult inpatients treated by an RT in two types of care facilities common in the European Union (EU), by providing evidence on validity, reliability and responsiveness of its scores. One is the nursing home. We will refer to the second type of facility as a ‘social-health centre’ [Citation53], acknowledging that there is no standard designation for it in EU countries. Both types of care facilities cater to older adults who, due to their level of functional dependency and clinical complexity, require rehabilitation and cannot be cared for at home.

Using psychometric standards [Citation30] as a guide, we examined validity based on the relationship of the COPM-P and COPM-S scores with other variables. Thus, we specifically studied: (1a) the convergent relationships with functionality, with the user’s perception of having received a person-centred practice during their rehabilitation process, especially dimensions that are most applicable in older adult inpatients, and with both overall valuations of experienced health state and aspects of health-related quality of life most linked to activity domains; (1b) In line with the study by Roe et al. (2020), where they examined the contribution of COPM satisfaction in explaining variables related to health-related quality of life and functionality, we also analysed whether the initial COPM scores added significant variance to the prediction of functional status post-RT intervention, after accounting for type of care facility (social-health centre or nursing home) and global health perception; and (2) the relationship with the user’s age, type of facility, pathology group, and educational level. More specifically, we expected differences in COPM scores among diagnostic groups and between type of facility, whilst we did not expect to find differences relating to age and educational level. In terms of reliability, we studied the temporal stability both of prioritised problems and COPM-P and COPM-S scores. Lastly, in terms of responsiveness, we studied the COPM’s ability to display changes over time and the relationship between change in the COPM scores and change in both functionality scores and type of care facility.

Method

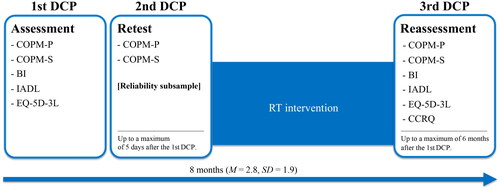

This is a quantitative prospective multicentre study comparing data from three collection occasions illustrated in . The process is described in more detail in the Procedure section. We designed the study to minimise disruptions in daily practice at the participating centres and to add value by training their professional staff. We maintained a commitment to ecological values, which we view as not only a methodological requirement, but also an ethical one.

Figure 1. Schematic outline of the study phases showing the instruments used and when they were applied. DCP: Data Collection Point; COPM-P: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure - Performance; COPM-S: Canadian Occupational Performance Measure - Satisfaction; BI: Barthel Index; IADL: Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Life; EQ-5D-3L: EuroQol-five domain-three level questionnaire; CCRQ: Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire; RT: Rehabilitation Team.

Samples and settings

The sampling procedure was purposive. The participants were recruited from nine social-health centres and eight nursing homes, in Catalonia, Spain.

Settings

In social-health centres, attention is provided for older adults with underlying pathologies who require functional recuperation following a surgical, medical, or traumatological procedure. The profile would, therefore, be of a person with sub-acute disease or chronic disease [Citation54]. The assessment and subsequent intervention of the RT – ranging from one to six months – is initially directed at the treatment of the disability, and afterwards towards dependency compensation in cases in which recovery is not possible. The purpose of rehabilitation in these cases is to maximise function and minimise limitations in activities and participation, in order to be able to live independently on returning home [Citation4,Citation5,Citation55].

In contrast, a nursing home patient is an individual with a functional loss who is unable to continue living in their own home and who experiences an increasing degree of dependency. The focus of the intervention in these facilities is diverse and might be aimed at incapacity prevention, recovery from incapacitating processes, maintenance in chronic processes, together with the modification of the activity and/or the environment where necessary. The RTʼs main aim is stimulation, the maintenance of functional abilities and quality of life [Citation4,Citation55]. Unlike for social-health centres, a stay in a nursing home tends to be indefinite, and the aims of interventions and follow-up care are reviewed on a regular basis.

General sample

At the 17 facilities, the eligible participants were (1) older adults receiving rehabilitation services at these facilities for the first time and (2) aged 60 or over at the time of the study. All participants’ medical histories were checked and they were interviewed in order to assess the following exclusion criteria: (1) users whose general condition was serious and who were unable to describe feelings and thoughts, (2) a score below 20 in the Mini-Mental State Examination, (3) those diagnosed as medically/psychiatrically unstable, (4) a projected treatment length of less than a week, and (5) occupational performance problems not having been described or prioritised in the initial interview. The general sample was made up of 172 participants, and the distribution by gender, age, type of care facility, and diagnostic group is shown in the upper section of .

Table 1. Demographics and initial assessment.

Reliability subsample

To study the test-retest reliability of the COPM measures in a subsample of the two types of facilities, the specific participant selection process used the following criteria: (1) Within six days following the initial assessment, a different COPM-trained staff member from the same RT that carried out the initial patient assessment was able to reapply the first three steps set out in the COPM manual [Citation10]; (2) This professional was available to conduct this second assessment before the patient’s planned rehabilitation sessions began. The subsample was made up of 31 older adults. It was verified that the distribution of the variables gender, age, type of care facility, and diagnostic group did not show statistically significant differences when compared to the distribution observed in the overall study sample (p ≥ .171).

Instruments

Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM) [Citation6]

The official Spanish translation of the COPM was used [Citation10]. The COPM is administered as a semi-structured interview with the client, with a view to identifying and rating their occupational performance problems in three occupational performance areas and three occupational categories: self-care (personal care, functional mobility, and community management), productivity (paid/unpaid work, household management, and school/play), and leisure (quiet recreation, active recreation, and socializing). There are four steps to administering the COPM. In the first step, the client identifies occupational performance problems that are important for them. In the second step, the client determines the degree of importance of each problem using the visual analogue scale method (VAS) from 1 to 10 (maximum importance). In the third step, after confirming a prioritisation of up to five problems, the client rates their performance and satisfaction for each of them, using a VAS score from 1 to10 (maximum performance/satisfaction). Then, the therapist calculates an average COPM performance score and satisfaction score. The final step is a reassessment, which involves the client re-scoring their level of performance and satisfaction following the intervention, which enables us to define the respective change scores in terms of the occupational performance perceived [Citation6,Citation10].

Barthel index (BI) [Citation34]

The Spanish version validated by Baztán et al. [Citation56] was used. The BI is administered by a professional in order to assess a person’s ability to carry out the following daily activities dependently or independently: eating, moving from chair to bed, conducting personal hygiene, using the toilet, bathing, moving around, going up and down stairs, getting dressed, and maintaining bowel and bladder control. Each item can be rated with a score of 0 (dependent), 5 (requires help), or 10 (independent), with the exception of the activity of moving from chair to bed and moving around, which includes an additional score to identify different levels of help given. The total score ranges from 0 (dependent) to 100 (independent). The BI is widely used by RTs and forms part of the series of assessment instruments already used in the facilities studied. Cronbach’s alpha for the BI ranges from 0.86 to 0.92 [Citation57].

Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scale (IADL) [Citation35]

The Spanish version validated by Vergara et al. [Citation58] was used. The IADL is administered by a professional to assess the client’s functional capacity via eight items: ability to use the telephone, go shopping, prepare meals, look after the house, wash clothes, use transport, be responsible for their own medication, and handle their finances. Each item has a numerical value: 0 (dependent) or 1 (independent). The total score is the sum of responses to all items and can range from 0 (maximum dependence) to 8 (total independence). The IADL is widely used among RTs and forms part of the series of assessment instruments already used in the facilities studied. The Spanish version shows a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94 [Citation58,Citation59].

EuroQol-D5 questionnaire (EQ-5D-3L) [Citation37]

The Spanish version was used [Citation60]. The EQ-5D-3L is a standardised instrument used to assess health-related quality of life. It encompasses a descriptive system with five dimensions (EQ-5D): mobility, personal care, daily activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Three levels of severity are assessed for each dimension: (1 = no problems, 2 = some problems, 3 = extreme problems). A single health index score is derived from these five dimensions based on Spanish coefficients [Citation61], which range from 0 (death) to 1 (best state of health), although there can be negative values when the health state is valued as worse than death. It also includes an EQ visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) used to obtain the self-rated perception of health with a type-format ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state). EQ-5D-3L scores have been shown to be valid in relation to socio-demographic variables and health status, along with having an acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α between 0.70 and 0.95) [Citation37,Citation60,Citation62].

Client-Centred rehabilitation questionnaire (CCRQ) [Citation63]

The version adapted to Spanish was used [Citation38]. The CCRQ-e is a questionnaire that measures the degree to which a person perceives whether they have undergone a client-centred practice during the rehabilitation process. The Spanish version is comprised of 29 items distributed over the following seven domains: client participation in decision-making and goal setting (6 items), client-centred education (3 items), evaluation and outcomes from the client’s perspective (4 items), family member involvement (5 items), emotional support (4 items), coordination/continuity (3 items), and physical comfort (4 items). The items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree), plus a response option for ‘does not apply’ (0). Lower scores correspond to a higher perception of client-centredness. As in the original version, in the Spanish version Cronbach’s α was between 0.64 and 0.85, and in the present sample it was between 0.66 and 0.81.

Procedure

At the start of the study, training in the use of the COPM was given to 21 occupational therapists and nine physiotherapists from the RTs of the 17 participating centres. This professional training in the use of COPM was spread over 12 months, and the process is described in a previous article [Citation64]. These professionals approached the users in their centres who fulfilled the eligibility criteria. None of the authors were involved in either participant selection or the administration of data collection instruments.

The participants’ socio-demographic and medical information was collected from service records.

As illustrated in , the study consisted of four phases and three data collection points conducted by the RT of each facility (assessment, retest, and reassessment). The main characteristics of each phase were:

Assessment: first administration of BI, IADL, EQ-5D-3L, COPM-P and COPM-S.

Retest: Another professional from the RT administered the COPM again to 31 participants within the same week, repeating the identification and problem prioritisation process, and the process of scoring performance (COPM-P) and satisfaction (COPM-S). The clients received no intervention between the two sessions. No information regarding the results of the initial assessment was given, either to the professional responsible for the retest or to the client.

Intervention: In every case, the rehabilitation intervention was directed and individualised in line with the client-centred criteria established by the COPM. The interventions were focused on both the recovery and maintenance of body functions and structures, as well as daily life activities and participation in their environment. Interventions to support occupations were proposed, including preparatory methods and techniques, orthotics and prosthetics, assistive technology and environmental modifications, wheeled mobility, and self-regulation interventions. Additionally, interventions through occupations and activities, education and training, advocacy, and group interventions were implemented [Citation55].

Reassessment: For each client in the general sample, the same RT member who conducted the initial assessment carried out the reassessment, which included the administration of COPM-P, COPM-S, BI, IADL, EQ-5D-3L, and CCRQ.

The participantsʼ socio-demographic and medical information was collected from service records. The only extra assessments that the participants completed as part of their involvement in the study were the COPM and the CCRQ. The data collection period was spread over eight months (M = 2.8, SD = 1.9).

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Terrassa Health Consortium (Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa) via a resolution dated 18th July 2016. All the facilities agreed to support the study in advance, and all the participants provided written informed consent. The documents followed the European rules for easy reading and cognitive accessibility [Citation65].

Data analysis

The following statistical analyses were conducted for validity purposes: (1) Spearman’s rank correlations to assess relationships between COPM scores and BI, IADL, EQ-5D-3L and CCRQ scores; (2) one-way ANOVA on ranks (Kruskal-Wallis H test) to analyse the differences in COPM scores among the different groups – age, education level, diagnosis, and type of care facility – with Mann-Whitney U test for post-hoc analyses between groups when necessary with Bonferroni-Holm’s correction for p-values due to multiple comparisons; (3) hierarchical linear regression models to determine whether initial COPM scores would add significant variance of the functional evaluation (BI and IADL) to the reassessment, after accounting for type of care facility and global health perception (EQ-VAS).

Test-retest of the COPM outcomes was analysed using Cohen’s kappa for problem prioritisation and Spearman’s rho correlations for COPM-P and COPM-S scores, the latter coefficient due to the small size of the subsample (n = 31) and the result of the Shapiro-Wilk normality test.

Regarding responsiveness, Wilcoxon’s signed rank test was applied for testing changes in perceived occupational performance and satisfaction scores between the initial assessment and post-intervention reassessment. Furthermore, differences in responsiveness between type of care facility (nursing home and social-health centre) were studied using Mann-Whitney U test. In addition, Spearman’s correlation was used to study the relationship between COPM and BI and IADL change scores.

The critical level for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The following proposals have been used as orientation thresholds to interpret the strength of the relationships studied. On the basis of Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, correlation coefficients of at least 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 were interpreted as representing small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. Also, according to Cohen’s guidelines (1988), d values of at least 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 for mean comparisons were interpreted as representing small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. The strength of agreement for categorical measures was evaluated using the [Citation66] criteria: kappa values from 0 to 0.2, 0.21 to 0.40, 0.41 to 0.60, 0.61 to 0.80 and 0.81 to 1 were interpreted as slight, fair, moderate, substantial, and excellent agreement, respectively.

Results

Complete data were obtained from 172 users whose scores on the instruments administered at the beginning of the study are summarised in the lower section of .

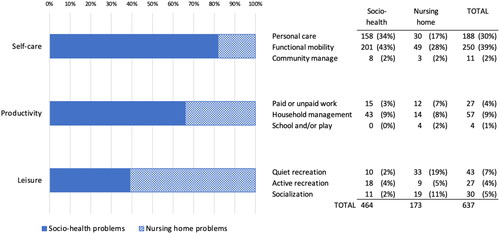

The participants described and prioritised a total of 637 occupational performance problems. Their distribution is shown in for each type of facility and occupational category. In relation to the number of problems identified per person, a mean of 4.07 (SD = 1.11) was obtained among the users of the social-health centres and a mean of 2.98 (SD = 1.44) in the nursing homes.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution of prioritised problems by COPM occupational performance areas and occupational categories for each type of Centre.

Validity evidence based on relationships to other variables

shows evidence of convergent validity for the different measures collected concurrently. The pattern of correlations was mainly as expected and similar for COPM-P and COPM-S scores: a high or medium degree of correlation with the BI; both EQ global scores (health index score and EQ-VAS); the EQ-5D-3L dimensions of mobility, self-care, and daily activities; and the CCRQ outcome evaluation and a low degree of correlation with the IADL; EQ-5D-3L anxiety; and CCRQ decision-making, education, emotional support, and physical comfort dimensions. Associations with the EQ-5D-3L pain dimension and the CCRQ family involvement and continuity dimensions were null or almost null.

Table 2. Association (spearman’s correlations) between the COPM and other measures.

shows the results of the four hierarchical regression analyses. Findings were similar in the four models, with only slight differences. After accounting for the type of care facility in step one, the EQ-VAS did not produce a significant change in the explained variance of the functional score (step two). However, when the COPM score was entered in step three, a significant change in the explained variance of the functional score was accounted for. However, the total percentage of variability explained by the functional score for the four final models was low (around 0.09).

Table 3. Summary of hierarchical regression models.

shows evidence of validity regarding the relationship network between the COPM scores and other demographic and clinical variables. No statistically significant differences were observed between the initial COPM-P and COPM-S scores by age and educational level. However, there were statistically significant differences regarding diagnostic group and type of centre. In terms of diagnostic group, both COPM-P and COPM-S in geriatric functional rehabilitation were significantly higher than in the trauma and neuro-rehabilitation groups. With respect to type of centre, both COPM-P and COPM-S were higher in the nursing homes than in the social-health centres.

Table 4. Evidence of validity based on the relationship with other variables.

Test-retest of the prioritised problems and COPM scores

Considering only the data provided by the subsample (n = 31), whose characteristics did not differ from the overall study sample, as explained in the method section, 127 occupational performance problems were identified during the initial COPM interview and 123 during the retest COPM interview. Some 81% of the patients prioritised the same problem (self-care 32% and functional mobility 48%). Cohenʼs Kappa values measuring test-retest for each of the five problems varied from 0.67 to 0.86 (all p-values: < .001). Also, Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient evaluating test-retest was 0.88 (p < .001) for performance scores and 0.86 (p < .001) for satisfaction scores.

Responsiveness

provides details of the significant differences between the initial and reassessment COPM scores in both types of care facilities. For comparisons in the social-health centre subsample, the lower bound of the confidence interval exceeded the relevant change criterion established in the COPM manual (2 points).

Table 5. Descriptives (M and SD) of COPM scores and comparison before and after intervention.

Furthermore, the mean difference between COPM change scores among social-health centre users and nursing home users (M, CI95%, and SD values also provided in ) was statistically significant (COPM-P: U = 1175.5, z = 6.91, p < .001; COPM-S: U = 1396.5, z = 6.19, p < .001), with a higher change score observed for social-health centre users than nursing home users (COPM-P d = 1.27; COPM-S d = 1.09).

Finally, regarding the two functionality criteria used (BI and IADL), the correlation between their change scores (reassessment minus initial assessment) and the change in COPM scores was as follows: COPM-P change and COPM-S change were highly and significantly correlated with BI change (r = 0.65, p < .001; r = 0.64, p < .001; respectively) and to a lesser extent with IADL change (r = 0.45, p < .001; r = 0.42, p < .001; respectively).

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to analyse the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the COPM among older adult rehabilitation inpatients in social-health centres and nursing homes. In relation to convergent validity, moderate correlations were obtained between the performance and satisfaction variables of the COPM with functional measures of ADL and perceived quality of life; and in turn with measures of experience of person-centred care, such as most of the dimensions assessed by the CCRQ. In the validity exploration related to other variables, no differences were observed with respect to educational level, but differences were evident with respect to pathology, type of facility, and age. The regression analysis showed good incremental validity of the COPM to help explain functional results of the sample, beyond the measure of perceived quality of life. The test-retest reliability of the COPM was excellent. Additionally, it provided satisfactory evidence of responsiveness in capturing differences before and after the intervention.

The prioritisation observed in occupational problems in the area of self-care (79.1% in the social-health centre and 47.3% in the nursing home) is in line with previous studies on the rehabilitation of older adult hospital inpatients [Citation40–42,Citation44] and older adult home rehabilitation patients [Citation24]. Likewise, differences can be observed by type of centre, both in the number of problems prioritised and in the categories prioritised [Citation19,Citation40,Citation43]. The largest numbers of occupational performance problems to be addressed among the users of social-health centres were in the categories of personal care and functional mobility, whilst in the nursing homes functional mobility, quiet recreation and personal care were prioritised. This can be explained as much by personal and diagnostic characteristics as by the aims of each institution [Citation24]. On the other hand, and contrary to what Phippsʼ study [Citation46] suggests, it is important to highlight the low prioritisation of problems in the occupational category ‘household management’ in social-health centre clients, given that the main aim of rehabilitation is to enable the client to return home. In our case, it would appear that this aspect has more to do with the characteristics of the rehabilitation services themselves than with the client’s diagnosis or needs [Citation4,Citation54]. Traditionally, in Spain these services focus more on the functional recuperation of basic self-care activities and hardly ever refer to the daily needs of the person on discharge. In fact, very few rehabilitation departments have areas dedicated to the simulation and training of instrumental daily life activities.

The validity of the COPM scores has been examined by correlating them with functional scores that aim to measure specific constructs linked to health and functionality [Citation12,Citation14,Citation17,Citation24,Citation31–33,Citation45]. Our study also found strong correlations between the COPM and the functional scores. The COPM is a tool that allows identifying and prioritising problems in occupational performance in different occupational categories. One of the main categories in which clients in this study identified occupational problems for which they required intervention from rehabilitation professionals was basic activities of daily living. This is why it is consistent that COPM measures are related to functional measures such as BI (basic ADL) and to a lesser extent with the IADL. In this sense, and supporting the same reasoning, the performance and perceived satisfaction measures of the COPM also obtain a strong correlation with the measures of the EQ-5D-3L (mobility, self-care, and activities). The COPM was also positively correlated with the health index score and the EQ-VAS. The greater the perception of performance and satisfaction, the greater the functional capacity for carrying out daily activities and therefore, the greater the quality of life. This finding can be corroborated with the study by Thyer et al. (2018) in which significant correlations were obtained between the COPM and quality of life scales (Thyer, 2018). The data produced by our study are in line with Enemark et al.ʼs study [Citation32], in which the self-care and activities dimensions of the EQ-5D-3L correlated with COPM-P, and the EQ-VAS correlated both with COPM-P and with COPM-S. In this same study, with a sample of users from different rehabilitation facilities, the authors also did not find significant correlation of the COPM with the pain dimension. In these cases, users did not present primary pain, but rather pathologies that clinically manifest without pain or pain secondary to interventions (Carpenter, 2001). On the other hand, the correlations of the COPM with the anxiety dimension of EQ-5D-3L could be linked to the negative state of mind produced by a loss in health condition, as has been observed in other studies that used instruments that measure emotional state [Citation28,Citation29,Citation67].

In line with the idea that the COPM was created to carry out a client-centred intervention [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10], one of the contributions of this study is to address its convergence with the CCRQ, a specific measure for client-centred rehabilitation [Citation38]. The results indicate that the higher the performance and satisfaction scores of the COPM, the higher the perception of having received client-centred attention in most of the CCRQ dimensions. The COPM records the subjective individual experience in relation to occupational performance, establishing objectives jointly between the professional and the client. This experience is what is also evaluated in the CCRQ by clients of rehabilitation services, meaning that the results of our study are coherent. However, the dimensions of continuity and family involvement, and also the physical comfort dimension, which includes items related to pain control, showed a low to moderate degree of correlation with the COPM, in line with the correlations obtained with the pain dimension of the EQ-5D-3L. This may be due to the fact that this population recovers its lost functionality and returns home after rehabilitation, without needing to involve family members [Citation63,Citation68]. In fact, the weak correlations observed between the COPM and the CCRQ dimensions pertinent to decision-making, educational needs, and physical and emotional comfort can be attributed to the nature of the pathologies commonly addressed in these rehabilitation services, which generally do not necessitate focused attention on physical and emotional well-being, nor do they require extensive information for making critical health-related decisions [Citation38,Citation68,Citation69]. It is worth highlighting specifically that the correlation between the dimensions of the CCRQ and COPM-S could indicate a positive relationship linked to a client-centred practice proposed at the beginning of a rehabilitation service, with continued assessment throughout the intervention [Citation70]. Although functional improvement has a positive effect on the client’s experience [Citation71], it would be interesting to examine this hypothesis in subsequent studies in which the COPM is not used as an instrument to establish the intervention aims.

Another interesting result is the relative contribution of the initial COPM and EQ-VAS scores to the prediction of the functional assessment at the end of the rehabilitation period. After adjusting for the type of care facility, the contribution of the COPM scores was greater than the contribution of a measure of perceived general health (i.e. EQ-VAS). These results should be treated with caution since the predictive capacity of the regression models was low. However, we consider that these results add relevant information to those provided by previous studies, since they establish a positive association between the COPM pre-intervention scores and the functional reassessment [Citation26,Citation33,Citation72]. Information about whether the COPM scores are more predictive of users’ functional scores than EQ-VAS would assist therapists in clinical settings who use the COPM as a tool for an initial outcome measurement.

With regard to clinical aspects, our study shows differences in the COPM scores according to type of centre. This fact could be explained by the characteristics and needs of the type of user that is treated by this service and the results obtained following intervention. It is logical to assume that the initial assessment of performance and satisfaction would be lower in users who have acute, more disabling pathologies than in people whose health conditions are chronic [Citation4,Citation5,Citation45,Citation54].

The reliability of COPM scores in terms of test-retest in our study can be considered excellent, with an interval of almost one week between measurements. These results are consistent with those of the study carried out by Ataschi et al. (2010) on performance and satisfaction in older adults, both for the temporal stability of the prioritised problems and for the satisfactory test-retest correlation values. Our results are also aligned with those of other studies that include an adult and older adult population [Citation22,Citation23,Citation31]. The difference compared to other studies that presented lower values [Citation48–50] could be attributed to methodological aspects, such as the time between assessments and inter- and intra-assessor differences [Citation49]; training prior to the administration of the measure; sample size; personal characteristics such as age and diagnosis; and the perceptions of the participants at the time of the assessment [Citation22,Citation31,Citation50]. Additionally, the COPM interview itself leads to awareness and resolution of problems, which can influence how patients prioritise problems in the second evaluation [Citation47,Citation64].

With regard to the 2-point clinically relevant COPM change proposed by the authors [Citation9], the results obtained from older adults in social-health centres clearly exceeds this criterion both in performance and satisfaction, as in other studies [Citation28,Citation41,Citation44]. It makes sense that changes would be subtler among users in nursing homes, where priority is given to maintaining the functional capacities and quality of life in this fragile population in which there is a higher prevalence of complex diagnoses. The evidence points to the possibility that this value could depend on numerous factors, such as the reassessment format (blinded previous scores) or the sample characteristics themselves (age, diagnosis, or degree of disability) [Citation23,Citation24,Citation52], suggesting that the difference in the change is greater for diagnoses that are only related to physical problems [Citation41]. Similarly, the difference in these change results is relevant in that it is an indicator of the sensitivity of the measure when it is used to assess performance and satisfaction for different people, diagnoses, and contexts [Citation12,Citation19,Citation26].

Limitations and methodological considerations

We now present the main limitations of this study with some methodological considerations and proposals for the future. Firstly, it is worth highlighting the small size of the sample for studying test-retest reliability – a greater number of participants would have produced more precise data – although the subsample did not present differences in its distribution with respect to the general sample. Secondly, although the COPM can be used with all populations, we excluded users with cognitive problems or poor insight in order to homogenise the sample. Therefore, whilst the number of centres and the heterogeneity of the group could indicate representativeness of clients using these services, because we did not include a sampling frame for all service clients, we cannot extrapolate results to the older adult population as a whole. Thirdly, in the multidisciplinary RT there was a difference between the number of assessors who were occupational therapists and those who were physiotherapists. For this reason we trained professionals to ensure that administration of the measures would be as homogeneous as possible [Citation64]. The recommendations of the authors of the COPM and of previous studies were respected both in relation to the inclusion criteria and the assessors’ training [Citation9,Citation12,Citation15]. Similarly, the study methods were adapted as much as possible to the reality of the centres, with the aim of respecting their usual dynamics. It is worth mentioning that the COPM is an instrument that can be complemented with other health measures in the planning and evaluation of interventions, in addition to being used by the different professionals in the RT [Citation11,Citation14,Citation19,Citation27]. We suggest that further studies go deeper into examining the convergent validity of the COPM scores with new measures of quality and perception focused on people in other populations with different ages and diagnoses, along with expanding the study to a community environment.

Conclusion

Our study supports the use of the COPM as a client-centred assessment and outcome measure for older adult inpatients receiving rehabilitation services. We have demonstrated the validity of the COPM through its correlations with variables related to functionality, activities of daily living, and health-related quality of life. We have also provided evidence of test-retest reliability. Additionally, we have shown that the COPM is responsive to changes, revealing that it is a sensitive tool for measuring outcomes in rehabilitation services. In summary, this study provides evidence of the quality of the Spanish version of the COPM, which has been little studied. Moreover, it pioneers the study of the psychometric properties of the COPM in rehabilitation settings for older adults in Spain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants, occupational therapists and physiotherapists from the 20 socio-health centers and nursing homes in Catalonia for their active involvement. I would also like to thank the COPM authors for their support, especially Mary Law for her involvement and contribution throughout the research process. We would also like to thank the Research Department of the Escola Universitària de Infermeria i Teràpia Ocupacional, for their support in the study. The first and second authors are grateful for the support of the Department of Research and Universities of the Generalitat de Catalunya to the Research Group and Innovation in Designs (GRID). Technology and multimedia and digital application to observational designs (Code: 2021 SGR 00718).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation competency framework.Geneva WHO; 2020.

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: 2020-2030. Geneva WHO; 2020.

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015.

- Durante Molina P, Tarrés P. P. Terapia ocupacional en geriatría: principios y práctica [Occupational therapy in geriatrics: principles and practice]. 3rd ed. Barcelona: Masson; 2010.

- Pozzi C, Lanzoni A, Graff MJL, et al. Occupational therapy for older people. In: Pozzi C, Lanzoni A, Graff MJL, Morandi A, editors. Occupational therapy for older people. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020.

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1990;57(2):82–87. doi: 10.1177/000841749005700207.

- Towsend EA, Polatajko H. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being and justice through occupation. Otawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE; 2007.

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT). Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Rev. ed. Ottawa (ON): CAOT Publications ACE; 2002.

- Law M, Polatajko H, Pollock N, et al. Pilot testing of the canadian occupational performance measure: clinical and measurement issues. Can J Occup Ther. 1994;61(4):191–197. doi: 10.1177/000841749406100403.

- Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Medida canadiense de desempeño de funciones ocupacionales. 3th ed. Otawa (ON): CAOT Publications ACE; 2014.

- Enemark A, Carlsson G. Utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure as an admission and outcome measure in interdisciplinary community-based geriatric rehabilitation. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(2):204–213. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2011.574151.

- Parker DM, Sykes CH. A systematic review of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: a clinical practice perspective. Br J Occupat Ther. 2006;69(4):150–160. doi: 10.1177/030802260606900402.

- Wilberforce M, Challis D, Davies L, et al. Person-centredness in the community care of older people: a literature-based concept synthesis. Int J Soc Welfare. 2017;26(1):86–98. doi: 10.1111/ijsw.12221.

- Yang SY, Lin CY, Lee YC, et al. The canadian occupational performance measure for patients with stroke: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(3):548–555. doi: 10.1589/jpts.29.548.

- Carswell A, McColl MA, Baptiste S, et al. The canadian occupational performance measure: a research and clinical literature review. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(4):210–222. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100406.

- McNulty MC, Beplat AL. The validity of using the canadian occupational performance measure with older adults with and without depressive symptoms. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2008;27(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/02703180802206231.

- Edwards M, Baptiste S, Stratford PW, et al. Recovery after hip fracture: what can we learn from the Canadian occupational performance measure? Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61(3):335–344. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.3.335.

- Cantero-Tellez R, Villafañe JH, Medina-Porqueres I, et al. Convergent validity and responsiveness of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure for the evaluation of therapeutic outcomes for patients with carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Hand Ther. 2021;34(3):439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2020.03.011.

- Kjeken I, Slatkowsky-Christensen B, Kvien TK, et al. Norwegian version of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in patients with hand osteoarthritis: validity, responsiveness, and feasibility. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(5):709–715. doi: 10.1002/art.20522.

- Nieuwenhuizen MG, Groot SD, Janssen TWJ, et al. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure performance scale: validity and responsiveness in chronic pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(5):727–746. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.12.0221.

- Rochman DL, Ray SA, Kulich RJ, et al. Validity and utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure as an outcome measure in a craniofacial pain center. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2008;28(1):4–11. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20080101-06.

- Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Uhlig T, et al. Reliability of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(8):1503–1509.

- Spadaro A, Lubrano E, Massimiani MP, et al. Validity, responsiveness and feasibility of an Italian version of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(2):215–222.

- Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Langeland E, et al. Psychometric properties of the Canadian occupational performance measure in home-dwelling older adults. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:411–423. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S113727.

- Stuber CJ, Nelson DL. Convergent validity of three occupational self-assessments. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2010;28(1):13–21. doi: 10.3109/02703180903189260.

- Thyer L, Brown T, Roe D. The validity of the canadian occupational performance measure (COPM) when used in a sub-acute rehabilitation setting with older adults. Occup Ther Health Care. 2018;32(2):137–153. doi: 10.1080/07380577.2018.1446233.

- de Waal MWM, Haaksma ML, Doornebosch AJ, et al. Systematic review of measurement properties of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in geriatric rehabilitation. Eur Geriatr Med. 2022;13(6):1281–1298. doi: 10.1007/s41999-022-00692-8.

- Carpenter L, Baker G A, Tyldesley B. The use of the canadian occupational performance measure as an outcome of a pain management program. Can J Occup Ther. 2001;68(1):16–22. doi: 10.1177/000841740106800102.

- Harper K, Stalker CA, Templeton G. The use and validity of the canadian occupational performance measure in a posttraumatic stress program. Occupat Ther J Res. 2006;26(2):45–55. doi: 10.1177/153944920602600203.

- American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association (APA), National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME). Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington (DC): AERA; 2014.

- Cup EH, Scholte Op Reimer WJ, Thijssen MC, et al. Reliability and validity of the canadian occupational performance measure in stroke patients. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(4):402–409. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr635oa.

- Enemark A, Wehberg S, Christensen JR, et al. The validity of the danish version of the canadian occupational performance measure. Occup Ther Int. 2020;2020:1309104. doi: 10.1155/2020/1309104.

- Roe D, Brown T, Thyer L. Validity, responsiveness, and perceptions of clinical utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure when used in a sub-acute setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(19):2772–2789. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1573934.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living 1. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179.

- Altuntaş O, Özata Değerli MN, Temizkan E, et al. Psychometric properties of the Canadian occupational performance measure in older individuals. Turk J Med Sci. 2024;54(1):338–347. doi: 10.55730/1300-0144.5796.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9.

- Capdevila E, Rodríguez-Bailón M, Szot AC, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Spanish version of the Client-Centred Rehabilitation Questionnaire (CCRQ). Disabil Rehabil. 2022;45(2):310–321. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2022.2028021.

- Stevens A, Beurskens A, Köke A, et al. The use of patient-specific measurement instruments in the process of goal-setting: a systematic review of available instruments and their feasibility. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(11):1005–1019. doi: 10.1177/0269215513490178.

- Chen YH, Rodger S, Polatjko H. Experiences with the COPM and client-centred practice in adult neurorehabilitation in Taiwan. Occup Ther Int. 2002;9(3):167–184. doi: 10.1002/oti.163.

- Bodiam C. The use of the Canadian occupational performance measure for the assessment of outcome on a neurorehabilitation unit. Br J Occupat Therapy. 1999;62(3):123–126. doi: 10.1177/030802269906200310.

- Donnelly C, O’Neill C, Bauer M, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM) in primary care: a profile of practice. Am J Occupat Ther. 2017;71(6):7106265010p1–7106265010p8.

- Enemark A, Morville AL, Hansen T. Translating the Canadian occupational performance measure to Danish, addressing face and content validity. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;0(0):1–13.

- Wressle E, Samuelsson K, Henriksson C. Responsiveness of the Swedish version of the canadian occupational performance measure. Scand J Occup Ther. 1999;6(2):84–89.

- Chan CCH, Lee TMC. Validity of the canadian occupational performance measure. Occup Ther Int. 1997;4(3):229–247.

- Phipps S, Richardson P. Occupational therapy outcomes for clients with traumatic brain injury and stroke using the Canadian occupational performance measure. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61(3):328–334. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.3.328.

- Atashi SA, Mohammad H, Seyyed Ali H. Reliability of the persian version of canadian occupational performance measure for iranian elderly population. Iran Rehabil J. 2010;8(12):26–30.

- Bianchini E, Della Gatta F, Virgilio M, et al. Validation of the Canadian occupational performance measure in Italian Parkinson’s disease clients. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2022;40(1):26–37. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2021.1942392.

- Chaves G de F dos S, Oliveira AM, Chaves JA, et al. Assessment of impairment in activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment using an individualized scale. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;74(7):549–554. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20160075.

- Eyssen ICJM, Beelen A, Dedding C, et al. The reproducibility of the Canadian occupational performance measure. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(8):888–894. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr883oa.

- Pan AW, Chung L, Hsin-Hwei G. Reliability and validity of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure for clients with psychiatric disorders in Taiwan. Occup Ther Int. 2003;10(4):269–277. doi: 10.1002/oti.190.

- Eyssen ICJM, Steultjens MPM, Oud TAM, et al. Responsiveness of the Canadian Occupational performance measure. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(5):517–528. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2010.06.0110.

- Gómez-Batiste X, Porta-Sales J, Pascual A, et al. Catalonia WHO palliative care demonstration project at 15 Years (2005). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(5):584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.019.

- CatSalut. Servei Català de la Salut. Atenció sociosanitària [Socio-health care]. [cited 2023 Feb 3]. 2020. Available from: https://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/serveis-sanitaris/atencio-sociosanitaria/

- Boop C, Cahill SM, Davis C, et al. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain and process fourth edition. Am J Occupat Therapy. 2020;74(Supplement_2):7412410010p1–741241001087.

- Baztán JJ, Pérez del Molino J, Alarcón T, et al. Índice de Barthel: instrumento válido para la valoración funcional de pacientes con enfermedad cerebrovascular [Barthel Index: valid instrument for the functional assessment of patients with cerebrovascular disease]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 1993;28(1):32–40.

- Cid-Ruzafa J, Damián-Moreno J. Valoración de la discapacidad física: el indice de Barthel [Evaluating physical incapacity: the Barthel Index. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 1997;71(2):127–137. doi: 10.1590/S1135-57271997000200004.

- Vergara I, Bilbao A, Orive M, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Lawton IADL Scale for its application in elderly people. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):130. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-130.

- Trigás-Ferrín M, Ferreira-González L, Meijide-Míguez H. Escalas de valoración funcional en el anciano [Functional assessment scales in the elderly]. Galicia Clinica. 2011;72(1):11–16.

- Badia X. The Spanish version of the EuroQol: description and applications. Med Clin. 1999;112(Suppl):79–85.

- Herdman M, Badia X, Berra S, et al. El EuroQol-5D: una alternativa sencilla para la medición de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en atención primaria. Aten Primaria. 2001;28(6):425–430. doi: 10.1016/s0212-6567(01)70406-4.

- Marti C, Hensler S, Herren DB, et al. Measurement properties of the EuroQoL EQ-5D-5L to assess quality of life in patients undergoing carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016;41(9):957–962. doi: 10.1177/1753193416659404.

- Cott CA, Teare G, McGilton KS, et al. Reliability and construct validity of the client-centred rehabilitation questionnaire. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(22):1387–1397. doi: 10.1080/09638280600638398.

- Capdevila E, Rodríguez-Bailón M, Kapanadze M, et al. Clinical utility of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure in older adult rehabilitation and nursing homes: perceptions among Occupational Therapists and Physiotherapists in Spain. Occup Ther Int. 2020;2020:3071405–3071413. (doi: 10.1155/2020/3071405.

- Inclusión Europa. Información para todos [Internet]. 2016. www.plenainclusion.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/informacion_todos.pdf

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310.

- Jenkinson N, Ownsworth T, Shum D. Utility of the Canadian occupational performance measure in community-based brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2007;21(12):1283–1294. doi: 10.1080/02699050701739531.

- Hansen AØ, Kristensen HK, Cederlund R, et al. Client-centred practice from the perspective of Danish patients with hand-related disorders. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(13):1542–1552. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1301577.

- Wilberforce M, Challis D, Davies L, et al. Person-centredness in the care of older adults: a systematic review of questionnaire-based scales and their measurement properties. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):63. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0229-y.

- Dedding C, Cardol M, Eyssen ICJM, et al. Validity of the Canadian occupational performance measure: a client-centred outcome measurement. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(6):660–667. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr746oa.

- McMurray J, McNeil H, Lafortune C, et al. Measuring patients’ experience of rehabilitation services across the care continuum. Part II: key dimensions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(1):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.408.

- Simmons DC, Crepeau EB, White BP. The predictive power of narrative data in occupational therapy evaluation. Am J Occup Ther. 2000;54(5):471–476. doi: 10.5014/ajot.54.5.471.