Abstract

Background

Acquired Brain injury (ABI) causes ripples throughout the occupational and social fabric. It enters people’s lives at a significant personal cost, encroaching on people’s sense of self. Vocational rehabilitation is a viable venue to regain control of their life and support them in forming a new sense of self. From an occupational perspective, little is known about how vocational rehabilitation can support people through transforming their sense of self.

Aim

This study aims to explore how vocational rehabilitation may influence the relationship between sense of self and occupational engagement for persons with ABI. Material and Methods: Six persons with ABI were purposely sampled. Data were collected using semi-structured individual interviews and analysed using a hermeneutic approach.

Results

The analysis resulted in three themes: a new sense of my former self, engaging in occupations as transformation, and the significance of support.

Conclusions

Participating in vocational rehabilitation can enable persons with ABI to form a new sense of self. Engaging in occupations and professional support is significant in the transformation process.

Significance

From an occupational perspective, the knowledge gained in this study stresses the essential role occupational engagement and proper targeted support have for people struggling to return to work after ABI.

Introduction

In Denmark, where this study was conducted, in 2017, around 26.000 adults were admitted to a hospital due to an acquired brain injury (ABI) [Citation1]. In this study, ABI refers to all types of acquired brain injuries caused by stroke, trauma, tumours, infections, or anoxia. The symptoms following ABI can be physical, cognitive, and communicative disabilities of varying extent, severity, and duration [Citation2].

The personal consequences of ABI are diverse and cause ripples and disruption across many areas of daily life [Citation3]. A recurring theme in the literature is the disruption of identity that people experience as a consequence of ABI [Citation4]. They report being estranged from their bodies and pre-injury selves due to the loss of self-continuity and uncertainty about their cognitive and emotional abilities. Consequently, they have to withdraw from occupations that define them, such as those related to work and leisure time [Citation4, Citation5].

According to Baumeister, a person’s sense of self is a part of the person’s identity [Citation6] describes the self as a knowledge structure based on experience. The self is an interpersonal sense of being and an initiator of actions and choices, regulating mental processes. Baumeister writes: ‘The self exists at the interface between the physical body and the social system, including culture’ [Citation6].

Work can be a source of identity and meaning in life, and the same applies to persons with ABI [Citation7]. A study synthesising experiences and meanings related to work among people with traumatic brain injury shows that the process of returning to work serves as a pathway to reconciling with a new sense of self [Citation8]. The study shows a dynamic relationship between how people strive to maintain or re-engage in work-related occupations and the formation of a new sense of self. This relationship between occupation and self has also been stressed by Hanson et al. but from a more general occupational perspective [Citation9].

Another occupational concept we explore in is study is occupational engagement [Citation10]. Engagement in work and other meaningful occupation is fundamentally important to the well-being of all people [Citation11]. For people with ABI the rehabilitation process can be about being able to participate and engage in occupations.

Enabling people to return to work is one of the leading rehabilitation goals [Citation12]. Here, rehabilitation after ABI is a holistic and person-centered approach to support the person to achieve an independent and meaningful life. Rehabilitation is a viable venue for people with ABI to not only manage the practicalities of living with a changed body but also develop a new sense of self, fulfil their potential, and optimise their contribution to family life, community, and society [Citation7]. The vocational rehabilitation centre in this study aims to support persons with ABI in improving their potential and independence and giving them choices and control over their lives. In particular, the services provided are vocational and directed at supporting people with ABI in resuming or obtaining work and shaping a meaningful balance between work and private life.

Several studies have explored how people with ABI form or reconstruct their self and identity in the face of adversity. For example, Sveen et al. [Citation5] explored biographical disruption among people with ABI. They found that the injury and disruption in capacity for occupational engagement caused changes in the participants’ self-perception and sense of time. Moreover, for some participants, returning to work was critical in reconstructing daily life and adjusting their self-perception to the reality of their new situation. However, little attention has been given to the central role of vocational rehabilitation and how regaining abilities is a simultaneous process of transformation into a new sense of self [Citation4, Citation5, Citation11, Citation12].

This study explores how vocational rehabilitation may influence the dynamic relationship between a sense of self and occupational engagement for persons with ABI.

Material and methods

In this study, we thus seek to understand the participants’ perspectives and their understanding of the subject matter, why a hermeneutic approach is appropriate.

In Gadamer’s delineation of hermeneutics, interpretations of the studied phenomenon will develop through dialogue, and shared understanding will be achieved through the fusion of horizons to enable a deeper understanding of the subject matter [Citation13, Citation14].

Participants and recruitment

A purposive sampling of six participants was made [Citation15]. The participants were recruited from a follow-up study completed by a research unit at ‘BOMI’ a Danish Centre for Rehabilitation and Brain Injury [Citation14]. Inclusion criteria were delimited to persons with ABI and post-concussion syndrome (PCS) who had participated in vocational rehabilitation at BOMI. Persons with PCS were also included since their symptoms are similar to persons with ABI and thus participate in rehabilitation together with persons with ABI. See .

Table 1. Demographic profile of participants.

Based on the inclusion criteria, the participants were invited to participate in this study by a senior researcher from ‘BOMI’ and subsequently given oral information about this study by the first author. Everyone who was invited agreed to participate.

Vocational rehabilitation

The vocational rehabilitation program consisted of individual and group therapies based on the person’s needs and goals. It also included a work placement program with supported employment [Citation16]. The rehabilitation varied in intensity and was continuously adjusted to accommodate individual needs. Group sessions took place at the rehabilitation centre. Other interventions took place in the participants’ homes or at their workplaces. Vocational rehabilitation consists of one or several of the following components [Citation16]:

Group-based mindfulness

Group-based therapies, including psychoeducation

Vision and balance training with a physiotherapist in collaboration with an optometrist

Individual sessions with a neuropsychologist

Individual session with an occupational therapist about ways to obtain a balance between work, everyday life, and job match

Individual work placement program, including work practice and supported employment with the rehabilitation team at the workplace

The rehabilitation was based on ‘Collaborative Brain Injury Intervention: Positive Everyday Routines’ [Citation17].

Data collection

Data were collected through six individual semi-structured interviews [Citation18, Citation19] and carried out by the first author. Four interviews were conducted face-to-face, and two were conducted online. The first author’s knowledge of Danish vocational rehabilitation practice informed the interview guide and key themes from the theoretical perspective presented above [Citation20–22]. The interview guide included questions like: ‘How did you experience your sense of identity while returning to work?’ and ‘What significance did it have for, e.g. your roles, relationships, and daily routines?’ (see ).

Table 2. Excerpt from interview guide.

In line with the hermeneutic methodology, attention to one’s pre-understanding is essential to producing new understandings [Citation13, Citation23]. The first author’s profession influenced her pre-understanding of the phenomenon studied as an occupational therapist and her previous experience working in the same organisation as the research setting, but never been in contact with the participants prior to the project. Therefore, preparing the interview guide included an awareness of one’s pre-understanding by creating room for being open and sensitive to the participant’s experiences [Citation14, Citation23]. Openness was also facilitated by discussing the questions with the last author.

The interview questions were continuously adjusted, and the interview guide was flexible, enabling the interviewer to follow the participant’s reflections and narratives during the interviews [Citation14, Citation23, Citation24].

Following the hermeneutic methodology, the participants received information about the interview in advance [Citation25]. This allowed them to prepare and think about their experiences during vocational rehabilitation. The participants could choose where and how the interview should be conducted. Accordingly, two interviews were conducted online, and four were conducted in the participants’ homes. The interviews lasted approximately one hour and were recorded digitally.

After the interview, the first author contacted the participants by phone, which provided the opportunity for follow-up questions. The participants were asked if new perspectives had emerged after the interview that they would like to add.

Data analysis

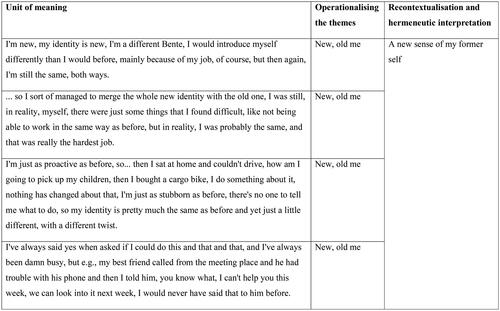

The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data were analysed using Dahlager & Fredslund’s [Citation23] hermeneutic approach to qualitative analysis [Citation23, Citation26]. Step one, overall impression: The first author listened to and transcribed the interviews to gain an overall understanding of the data set as a whole. Step two, identification of meaning units: The first author identified and operationalised the meaning units inductively one interview at a time. Step three, operationalising the meaning units into themes: This meant carefully reading each meaning unit several times to understand what the unit covered and how it was connected to other similar meaning units. The theme selection was guided by the research question. Up till this point, the analysis was an iterative process of moving back and forth in the three steps several times, getting new perspectives and a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences.

Step four, recontextualising and hermeneutic interpretation: The themes were sent to the participants for feedback and reflections to ensure they aligned with their individual experiences. All six participants could recognise themselves in the themes, though reading them evoked new perspectives on the subject matter they had not been aware of during the interview. This feedback contributed to further reflections and interpretations. Here, the recontextualisation and hermeneutic interpretation were made using the theoretical perspective presented in the introduction and the first author’s pre-understandings to gain a deeper understanding of the themes. The process comprised juxtaposing the themes and theoretical perspectives and thinking about them based on the first author’s professional experiences. The analysis was continuously discussed with all the authors who are experienced qualitative researchers. The results and quotes were translated from Danish to English during this process. Initially, the quotes were translated by the first author and afterward checked by a professional translator. The authors discussed and compared the translation of quotations and culturally bound words with the Danish original to ensure that the meaning was preserved () [Citation27].

Ethics

Following Danish legislation on research ethics, the study did not require approval by a Research Ethics Committee. In Denmark, only research that entails biological sampling and testing of pharmacological and hospital equipment on human subjects needs permission from regional or national ethics committees [Citation28]. All participants were given verbal and written information about the project, and consent was obtained before data collection. The participants were also informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their consent at any time. To ensure confidentiality, the data presented in this article is anonymised. Data storage was managed according to The Danish Data Protection Agency’s regulations [Citation29]. All data and information about the participants’ identities were handled in complete confidentiality throughout the research process and deleted according to ethical guidelines. The Declaration of Helsinki and the Danish Code of Conduct were followed [Citation28, Citation30].

Results

The analysis resulted in three themes: A new sense of my former self, Engaging in occupations as a transformation, and The significance of support.

A new sense of my former self

In rehabilitation, the goal for the participants is to maintain valued parts of their former selves before the ABI by engaging in the same occupations as before. The participants described how they wished to remain the same person as before the injury, even though they knew it may not be possible.

The participants described going through a personal development process during the vocational rehabilitation, where they experienced dilemmas about their former selves concerning their new life situation. The participants described wanting to be the same person as before and being able to do their usual occupations. They described feeling like a new person while simultaneously feeling connected with their former self. For Bente, vocational rehabilitation initiated a process which she described in this way:

…so I sort of managed to merge the whole new identity with the old one; I was still, in reality, myself; there were just some things that I found difficult, like not being able to work in the same way as before, but in reality, I was probably the same, and that was really the most challenging job.

I’m new, my identity is new, and I’m a different Bente; I would introduce myself differently than I would before, mainly because of my job, of course, but then again, I’m still the same, both ways.

I still have a dream about being my old self again. The feeling of not being satisfied with the new situation and having lost something is part of coming to terms with my new sense of self.

Engaging in occupations as a transformation

For the participants, an essential part of forming a new sense of self through vocational rehabilitation was augmented by their occupational engagement. In vocational rehabilitation, the focus is primarily on returning to work. Engaging in work-related occupations gave the participants a sense of meaning in life and contributed to a positive sense of self and, in particular, their sense of self-continuity in going through a severe life transition. Related to this, doing work-related occupations in a natural work environment was perceived as significant for the participants. Lars expressed the significance of actual work experience like this:

I forgot that I was sick. Well, you never really forget that, but for me, it meant everything because it is a part of becoming, how should I put it, being healed.

I do not want to become some early retiree who sits at home and does nothing, and my life just goes by. I want to go out and move on.

The participants reported that vocational rehabilitation helped them find meaning and motivation to explore new occupational possibilities. For example, Bente decided to mentor other persons with ABI, offering the support she needed in the early stages of her rehabilitation. She found meaning in her new role, which she also felt was crucial to others.

The participants described acceptance of not being able to work like before as essential to adapting to their new life situation and continuing towards developing a new everyday life. Having less energy and endurance could be challenging to accept, as Torben explains here:

I have tried to go too far [working for too long], but I discovered that it doesn’t work. You have to listen to your body. I have to balance things and that is extremely difficult for me to accept.

I think this will never get better, I have to accept that I am only able to function at this level.

For Mette, who was uncertain about her future job situation, the lack of possibility of doing work-related occupations was interfering with her wish to get on with her life:

I just feel like I’m in a sort of time bubble, and I feel like I am holding my breath, so my new life has not really begun.

The significance of support

Joining a collaboration process with the professionals in the rehabilitation program was of great importance to the participants. The feeling of being understood and receiving appropriate counselling about how to manage the new life situation was something the participants especially emphasised as important. Tine described how she experienced starting vocational rehabilitation and meeting with professionals and other persons with ABI in this way:

No one understands what it means to have a brain injury and […] not being able to grasp why you feel the way you do fully. So, to come here [to the Rehabilitation Center] and get such a helping hand and be with others who are in the same boat, and with people who look at you and say, ‘Well, I believe you need this and this’ is very helpful.

I got an explanation of all these things and learned about the brain; it gave me a lot. It all just makes perfect sense, and it provided me with tools to understand myself and to be in this situation.

You cannot have these conversations with anyone other than professionals about accepting that there is no set timeline [for recovery]. You have to accept the situation; you will not move forward until you allow yourself time,and it might be that you will not return to the life you had before. There were many tough nuts to crack, and there still are, but there were people who helped me.

In vocational rehabilitation, the support of professionals is also about finding a match between work tasks and the person’s working capacity and current skills. It is a collaboration between the person with ABI, the professionals, the municipal employment centre, and the workplace. Finding the right match can take time and may contain steps, such as trying to work, evaluating, adjusting, and repeating it until the match is appropriate. Bente described having professional support when returning to work after her sick leave:

It’s worth its weight in gold to have someone involved in such a process here, without which I would have pushed myself way too hard. There is no doubt about that.

5-6 months later [after my brain injury], I worked in a kindergarten, and it backfired completely, and I think, overall, I should have been spared from that if there had been someone to take care of me.

Discussion

This study explores how vocational rehabilitation may influence the dynamic relationship between a sense of self and occupational engagement for persons with acquired brain injury (ABI). We found that vocational rehabilitation facilitated training and the skills required to handle a new life situation. In parallel to this, the participants formed a new sense of self while at the same time maintaining a relation to their old self.

To gain insight into and discuss how vocational rehabilitation can influence the sense of self and meaning in the life of persons with ABI, Schlossberg’s theory of life transitions and an occupational science perspective of engaging in occupations as a problem-solving process and transformative act are used [Citation31]. According to Schlossberg, life transition can significantly change a person’s relationships, routines, values, or roles [Citation32]. Life transitions can be initiated by unexpected events [Citation32], such as an ABI. The transition process occurs as a transactional interaction between individuals and the environment. It can be affected by the support of others and the strategies the person employs to manage the situation [Citation32]. From an occupational perspective, understood as ‘a way of looking at or thinking about human doing’ [Citation33], life transition is closely related to engaging in occupations that may constitute a transformative act [Citation31]. This means that in this study, occupation is understood as situated and engaging in occupations as a process of overcoming challenges and uncertainties in everyday life [Citation20]. Engaging in occupations is the inquiry process of moving from indeterminate situations to determinate situations that differ from the initial situations [Citation20].

Meaningful occupations

The meaning of work and other everyday life occupations changed for the participants regarding the value they attach to them, and the time spent on them. These results agree with the findings in the qualitative synthesis by Stergiou-Kita et al. They found that how people work and the meaning they attach to work seem to undergo a series of transformations [Citation8]. Transformation appeared as a process of rediscovery that was influenced by various aspects, for example, by changing the amount of time they spend working and the type of work they chose to engage in [Citation8]. Transformation also appeared through existential thoughts about the meaning of life after a brain injury. In this study, returning to work was also viewed as a significant goal, and having a job provided a sense of purpose and normality, the ability to contribute to society, and community reintegration. This meaning of work is also highlighted in the scoping review made by Saunders et al. [Citation7]. They found that returning to the labour market and finding a meaningful job seemed significant for the participants’ transition from their old life to the new and in creating a new self. Similar results are found in the study of Rubenson et al. [Citation34], which concluded that returning to work after an ABI is a long process and maintaining a meaningful occupational balance was crucial to this process. For the participants in Rubenson et al.’s study, the meaning of work was also about personal finances and security in life [Citation34]. The present study demonstrated that maintaining or rediscovering the meaning of work is individual and can change after ABI. For the participants in this study, the meaning of work revolved around embodying their desired self and establishing a connection with their new sense of self.

Studies showed that for persons with ABI who lose the sense of meaning related to their work, other occupations can become important and take on new meanings [Citation7, Citation34]. All the participants in the present study expressed that in their new situation, things besides work became essential for them in their everyday lives. For example, they were spending more time with their children and serving as a mentor for other people with ABI. The results from this study thus indicate that engaging in meaningful occupations as part of vocational rehabilitation may serve as an essential pathway for discovering new meaning in life and the transition from the old life to a new one.

Professional support

The findings showed that professional support can be essential for discovering ways to engage in occupations and what may be perceived as meaningful and transformative for the person’s sense of self. This is also identified in research by Rubenson et al. [Citation28], which showed that professional support is necessary for returning to work. The present study demonstrated that navigating uncertain situations can render individuals vulnerable, and finding strategies to engage in occupations may require support. Support seems important for facilitating transition processes, and the support provided significantly influences the process. The need for support in vocational rehabilitation is also found in the qualitative synthesis of Stergiou-Kita et al. [Citation8], who identified that support from peers, professionals, and workplaces was significant in vocational rehabilitation.

Implication and future research

Understanding the importance of engaging in occupations within vocational rehabilitation and considering the findings of this study, occupational therapists can play an important role in the multidisciplinary team of professionals [Citation35], emphasising occupational-based and focused interventions [Citation36].

Since this study represents the perspective of persons with ABI, it is considered relevant for future research to have other perspectives, such as the perspective of the workplace and relatives. It is also considered relevant for future research to go deeper into and identify which elements of vocational rehabilitation are especially relevant and practical, as well as the transition processes, and to obtain more information about how these things intertwine.

Methodological considerations

The first author interacted with the participants several times during the study, establishing a trusting relationship, to enhance credibility. The encouragement and trust that developed during the interviews fostered openness in the conversation and the participants’ willingness to share their stories, thus strengthening the quality of this study.

Two interviews were conducted online due to the participants’ concerns about the Covid-19 pandemic. Although this format enabled the participants to take part and the participants and the first author were familiar with online meetings, some interactions, non-verbal communications, and nuances may have been missed.

Talking about transitions in life can be a sensitive topic. The phone call after the interview allowed the participants to withdraw or clarify statements. It also allowed the first author to verify if something was unclear. The participants’ possibility to give feedback on the themes is also considered a strength of this study.

Dahlager and Fredslund’s [Citation23] approach to hermeneutic analysis was used to ensure the stability, consistency and reliability of the interpretation and findings during the analysis and throughout the research process. Moreover, the translation of quotations from Danish to English followed the evidence-based recommendations of Van Nes et al. to retain the meaning in what was said [Citation27]. Nevertheless, some meanings may have been lost in translation.

The first author was aware of her own pre-understanding during the data collation, analysis and the writing process, and this was continuously discussed with all the authors to enhance confirmability. The empirical data and the relevant theoretical perspectives used in this study has contributed to a reflective process and producing new nuances of exiting concepts.

Conclusion

The findings from this study show that participating in vocational rehabilitation can support a process of recreation, forming a new or holding on to the sense of self for individuals with ABI. This process is facilitated by engaging in meaningful occupations as part of vocational rehabilitation. The process can be frustrating, and the person can experience conflict with himself/herself when facing a new reality. Accepting the new life situation is a significant step in the transition process.

For persons with ABI, engaging in work occupations seems essential in creating a new sense of self and taking part in life and society. Individual and situated professional support can become significant in engaging in new and familiar occupations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Dataopgørelser vedrørende voksne med erhvervet hjerneskade (Health data regarding adults with acquired brain injury); 2020 [Internet]. 4. Vol. 2021. Sundhedsdatastyrelsen;. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Viden/Hjerneskade/Dataopgoerelser-vedroerende-voksne-med-erhvervet-hjerneskade.ashx?la=da&hash=A6C71400D04FE621A25A19BD3E5F5765DB637896.

- Gilmore N, Katz DI, Kiran S. Acquired brain injury in adults: a review of pathophysiology, recovery, and rehabilitation. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups. 2021;6(4):714–727. doi: 10.1044/2021_persp-21-00013.

- Norlander A, Iwarsson S, Jönsson AC, et al. Participation in social and leisure activities while re-constructing the self: understanding strategies used by stroke survivors from a long-term perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(16):4284–4292. 31 doi: 10.1080/09638288.2021.1900418.

- Martin-Saez MM, James N. The experience of occupational identity disruption post stroke: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. Disabil Rehabil. 2021; 43(8):1044–1055. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1645889.

- Sveen U, Søberg HL, Østensjø S. Biographical disruption, adjustment and reconstruction of everyday occupations and work participation after mild traumatic brain injury. A focus group study. Disabil Rehabil. 2016; 38(23):2296–2304. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1129445.

- Baumeister RF. Self and identity: a brief overview of what they are, what they do, and how they work. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2011 48-55 DOI:10.1111/J.1749-6632.2011.06224.

- Saunders SL, Nedelec B. What work means to people with work disability: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2014; 24(1):100–110. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9436-y.

- Stergiou-Kita M, Rappolt S, Dawson D, et al. Towards developing a guideline for vocational evaluation following traumatic brain injury: the qualitative synthesis of clients’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(3):179–188. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=idre20 doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.591881.

- Hansson SO, Björklund Carlstedt A, Morville AL. Occupational identity in occupational therapy: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2022; 29(3):198–209. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2021.1948608.

- Morris K, Cox DL. Developing a descriptive framework for ‘occupational engagement. J Occup Sci. 2017; 24(2):152–164. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1319292.

- Hammell KW. Opportunities for well-being: the right to occupational engagement. Can J Occup Ther. 2017; 84(4-5):209–222. doi: 10.1177/0008417417734831.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen. Anbefalinger for tværsektorielle forløb for voksne med erhvervet hjerneskade; 2020.

- Gadamer HG, Weinsheimer J, Marshall DG. Truth and method. [Paperback. Bloomsbury revelations. London Bloomsbury; 2013.623.

- Paterson M, Higgs J. Using Hermeneutics as a Qualitative Research Approach in Professional Practice. Qualitative report. 2015. VOL.10, NR. 2, ARTICLE 9 DOI: 10.46743/2160-3715/2005.1853

- Green J, Thorogood N. Developing Qualitative Research Proposals. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles SAGE; 2018.49–82.

- Hoeffding LK, Nielsen MH, Rasmussen MA, et al. A manual-based vocational rehabilitation program for patients with an acquired brain injury: study protocol of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (RCT). Trials. 2017;18(1):371. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2115-0.

- Ylvisaker M, Feeney TJ. Collaborative brain injury intervention : positive everyday routines. San Diego Singular Publishing Group; 1998.330.

- Green J, Thorogood N. in-depth Interviews. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles SAGE; 2018.115–146.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Conducting an Interview. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, Calif Sage Publications; 2014.149–166.

- Madsen J, Josephsson S. Engagement in occupation as an inquiring process: exploring the situatedness of occupation. J Occup Sci. 2017; 24(4):412–424. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1308266.

- Dickie V, Cutchin MP, Humphry R. Occupation as transactional experience: a critique of individualism in occupational science. J Occup Sci. 2006;13(1):83–93. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2006.9686573.

- Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, et al. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63(1):9–23. doi: 10.1177/000841749606300103.

- Dahlager L, Fredslund H. Hermeneutisk analyse -forståelse og forforståelse. In: vallgårda S, Koch L, editors Forskningsmetoder i folkesundhedsvidenskab. 4. Udgave, Kbh. Munksgaard; 2016. p. 157–181.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. Interview variations. Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles, Calif Sage; 2014.

- Vandermause RK, Fleming SE. Philosophical hermeneutic interviewing. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(4):367–377. doi: 10.1177/160940691101000405.

- Green J. Begining Data Analysis. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles SAGE; 2018. p. 249–284.

- van Nes F, Abma T, Jonsson H, et al. Language differences in qualitative research: is meaning lost in translation? Bronnum-Hansen H, Jeune B, editors. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(4):313–316. Dec doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0168-y.

- Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity; 2014 [cited 2023 Jan 15]; Available from: www.ufm.dk.

- I (Legislative acts) REGULATIONS REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL. of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive. 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA relevance).

- I tvivl om jeg skal anmelde [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 15] Available from: https://komite.regionsyddanmark.dk/i-tvivl-om-anmeldelse#1ujkwl.

- Raanaas RK, Lund A, Sveen U, et al. Re-creating self-identity and meaning through occupations during expected and unexpected transitions in life. J Occup Sci. 2019;26(2):211–218. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2019.1592011.

- Anderson ML, Goodman J, Schlossberg NK. What do we need to know? In: Anderson ML, Goodman J, Schlossberg NK, editors. Counseling adults in transition : linking practice with theory. New York Springer; 2011.p. 3–96.

- Njelesani J, Tang A, Jonsson H, et al. Articulating an occupational perspective. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(2):226–235. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2012.717500.

- Rubenson C, Svensson E, Linddahl I, et al. Experiences of returning to work after acquired brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2007;14(4):205–214. doi: 10.1080/11038120601110934.

- Hitch D, Pepin G, Hitch D. Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy : an analysis of theoretical ways of knowing therapy : an analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(1):13–25. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1726454.

- Fisher AG. Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: same, same or different? Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21 Suppl 1(sup1):96–107. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2014.952912.

- Walder K, Molineux M. Occupational adaptation and identity reconstruction: a grounded theory synthesis of qualitative studies exploring adults’ experiences of adjustment to chronic disease, major illness or injury. J Occup Sci. 2017; 24(2):225–243. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2016.1269240.

- Bryson-Campbell M, Shaw L, O’Brien J, et al. Exploring the transformation in occupational identity: perspectives from brain injury survivors. J Occup Sci. 2016;23(2):208–216. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2015.1131188.