Abstract

There is an ongoing clinical dilemma of how best to treat patients who present themselves with visceral crisis. The time needed to undo the state of visceral crisis is the most relevant outcome for this patient group. We describe four patients treated with CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy for HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer who presented themselves with a visceral crisis. Two of them are male and three of them had synchronous metastatic breast cancer. Two patients had lymphangitis carcinomatosis of the lungs, one extensive disease of the eye and one of the liver. Time to first clinical response was observed within a few weeks in three patients. For one patient a switch to chemotherapy was needed. These cases show that treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors can achieve a rapid response in patients experiencing visceral crisis. We conclude that chemotherapy is not the sole possibility in visceral crisis, and that CDK4/6 inhibitors can be considered as well.

Introduction

Nowadays the treatment of patients with hormone receptor positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (HR+/HER2-) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) primarily consists of endocrine therapy, generally with the addition of CDK4/6 inhibitors. It is recommended by international guidelines to use at least two lines of endocrine-based therapy and postpone chemotherapy until endocrine resistance has occurred [Citation1]. The use of chemotherapy as first given treatment is only advised for patients who are showing signs of imminent organ failure [Citation1].

Visceral crisis is the state of extensive metastases accompanied by signs of rapidly deteriorating organ function failure [Citation2]. In the 3rd advanced breast cancer guideline of 2017, visceral crisis was defined as ‘severe organ dysfunction as assessed by signs and symptoms, laboratory studies, and rapid progression of disease’ [Citation3]. In the 5th advanced breast cancer guideline of 2020, the definition was further specified with two examples [Citation4]. Liver visceral crisis is defined as a rapidly increasing bilirubin >1.5 ULN in the absence of Gilbert’s syndrome or biliary tract obstruction. Lung visceral crisis is defined as rapidly increasing dyspnoea at rest, not alleviated by drainage of pleural effusion. The guideline also states the situation of ’impending visceral crisis’, with a given example of a fully metastatic liver with considerably altered liver enzymes, but normal bilirubin. Real-world evidence of the proportion of patients presenting with visceral crisis is unknown, but the situation is estimated to occur in around 10–15% of MBC cases [Citation4]. Patients with visceral crisis are considered to have a poor prognosis [Citation2,Citation5]. A retrospective study in 133 patients with several types of visceral crisis reported a median overall survival of 11.2 months [Citation6]. In the presence of either visceral crisis or impending visceral crisis the most rapidly efficacious therapy is indicated [Citation4]. Thus, patients experiencing a visceral crisis are traditionally treated with chemotherapy with the presumption that chemotherapy provides the fastest response on aggressive, extensive metastases. On the other hand, little research is done on treating patients with visceral crisis. Patients with organ dysfunction due to visceral metastases are usually excluded from randomized clinical trials. Therefore, chemotherapy as the preferred treatment option in visceral crisis is more of an assumption than evidence based practice.

In clinical practice, patients can have visceral crisis of varying severity. The course and degree of imminent organ failure can be diverse, with possibly varying opinions among oncologists. Consequently, patients might be treated differently. It can be questioned if the most rapidly efficacious therapy should always be a chemotherapy regimen. Potentially, CDK4/6 inhibitors combined with endocrine therapy might also lead to a rapid response. We here describe a series of patients with visceral crisis where oncologists chose to start with a CDK4/6 inhibitor combined with endocrine therapy.

Case presentations

Case 1

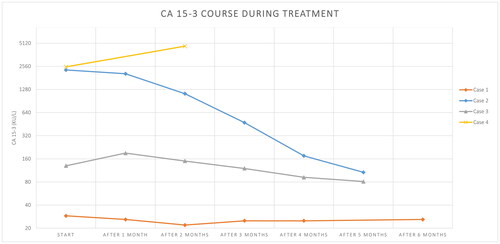

A 70-year-old man was evaluated at the outpatient department for swelling of the right breast (). He mentioned a slowly progressing, palpable swelling for four years, which started bleeding 6 weeks ago. The patient reported rapid deterioration of physical condition in the past weeks characterized by increasing fatigue and shortness of breath. On physical examination, there was dyspnoea with minimal physical activity and an ulcerating tumour of 20 × 15 cm around the right nipple without palpable lymph nodes. Laboratory findings showed no abnormalities and a low CA 15-3 value (; ). Imaging and biopsy results showed grade 2 non-specified type (NST) carcinoma, HR+/HER2-, with metastases in the ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes, the sternum and both lungs. The CT scan was suspected for lymphangitis carcinomatosis in the lungs (). Due to the rapid decline in physical condition within a few weeks and possible lymphangitis carcinomatosis, a visceral crisis was suspected. The patient was treated with ribociclib, letrozole and an LHRH-agonist. After one cycle the tumour size was already decreased by more than 50%, to a size of 8 × 7 cm. After two full cycles the patient reported no other complaints than fatigue. After four months partial response was confirmed by imaging ().

Figure 1. Course of CA15-3 tumour marker tests from start of systemic therapy and during the first 6 months of systemic treatment. Case 4 switched to chemotherapy 2 months after diagnosis.

Table 1. Patient and tumour characteristics of patients per case at time of presentation.

Table 2. Laboratory results of patients per case at time of presentation with (impending) visceral crisis.

Table 3. Imaging results of patient cases 1, 2 and 3.

Case 2

A 66-year-old man was seen by an ophthalmologist for complaints of orbital pain and diplopia since 3–4 weeks (). He also mentioned fatigue and 20 kg weight loss since 9 months. Otherwise he was still able to perform his work at a café and did not feel unwell. On physical examination, he was pale and had a tumour of 4 × 2 cm in the right breast with a palpable, ipsilateral lymph node supraclavicular. Laboratory findings were hypocalcaemia and elevated alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase and CA15-3 values (). The patient was admitted for intravenous calcium administration to treat hypocalcaemia. Imaging and biopsy results demonstrated a grade 1 NST, HR+/HER2-, breast cancer with metastases in the lymph nodes, bones, lungs, adrenal gland, peritoneum, eyes and skin. Several intra-orbital and eye muscle nodes were seen in both eyes, without further cerebral abnormalities (). Hypocalcaemia was concluded to be caused by a combination of bone metastases and pre-existent hypoparathyroidism. Rapid development of orbital pain and diplopia was considered as an impending crisis of the eye function. Treatment with palbociclib, letrozole and an LHRH-agonist was initiated. After one cycle there was no further deterioration of the vision. After two full cycles patient’s diplopia faded and CA15-3 decreased rapidly, considered as a clinical and biochemical partial response (.).

Case 3

A 60-year-old woman experienced a grade 3 HR+/HER2- NST breast cancer 19 years ago, for which she had undergone mastectomy, locoregional radiotherapy on the chest wall and regional lymph nodes, adjuvant chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. After four years of adjuvant tamoxifen use, pathologic lymph nodes were found in the contralateral axilla without any signs of other disease recurrence. She underwent an axillary lymph node dissection, locoregional radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy followed by five years of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment, which had finished ten years ago. She was now admitted to the hospital because of dyspnoea for 7 weeks and difficulty in swallowing, which had resulted in significant weight loss (). She complained of not being able to perform basic activities of daily life without shortness of breath. On physical examination, there was dyspnoea with minimal activity (NYHA grade 3) and she had reduced breathing sounds over the right lung, but no inspiratory stridor was heard. Laboratory findings revealed no abnormalities except an elevated CA15-3 value (; ). Imaging and biopsy results showed metastasized disease of the previous HR+/HER2- breast cancer, with a mediastinal tumour mass growing into the surrounding structures, pleural effusion and lymphangitis carcinomatosis in the lungs (). There were also metastases in the bones with a pathological fracture of the ninth thoracic vertebra. She underwent a pleural drainage, during which 480 cc of exudate was drained, and subsequently a pleurodesis was performed. However, this had no effect on the dyspnoea. Due to no relief of dyspnoea after drainage a visceral crisis was established. She was treated with corticosteroids, radiotherapy on the mediastinal mass and spine, and started treatment with ribociclib and letrozole. After radiation and only one cycle of systemic therapy, both the swallowing and dyspnoea had improved. The clinical response was formally confirmed after three cycles of therapy by imaging and declined tumour marker as stable disease according to RECIST 1.1 criteria ().

Case 4

A 60-year-old woman was evaluated in the emergency department for dyspnoea on exertion for 3 weeks. In the past two months she experienced progressive fatigue and 15 kg weight loss. She also mentioned night sweats (). The medical history was non-contributory. She arrived in a wheelchair and was unable to walk more than 10 m because of fatigue and continuous exhaustion. On physical examination, she had several palpable swellings in the right breast. Laboratory findings were anaemia, hypercalcemia and liver test abnormalities (). The following week she experienced rapid deterioration in her clinical condition with fever without proof of infection, increasing hypercalcaemia, acute kidney failure and progressive liver test abnormalities. Imaging and biopsy results revealed a grade 2, lobular, HR+/HER2-, breast cancer with metastases in the lymph nodes, bones, liver, spleen and peritoneum. Visceral crisis was suspected due to a rapid deterioration of performance status and extensive visceral spread. Treatment with palbociclib and letrozole was initiated. Based on progressive liver test abnormalities (bilirubin 36.5 umol/L) and the development of pancytopenia during the first cycle of CDK4/6 inhibitor-based therapy, the treatment was switched to chemotherapy, although the clinical complaints had improved. The patient was treated with paclitaxel and response was observed after three cycles ().

Discussion

The effect of chemotherapy on tumour cells is primarily cytotoxic, leading to a fast response. From endocrine therapy one expects a slower response, resulting from blocking the oestrogen receptor signalling pathway, which is important for the growth, proliferation and invasion of HR + breast cancer cells [Citation7]. The therapeutic effect of CDK4/6 inhibitors is different and based on the inhibition of the cell cycle. Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 are fundamental enzymes for the cell cycle progression. The molecular pathway activated by CDK4 and CDK6 is relevant in several cancer types, but specifically has a central role in the growth of oestrogen-receptor positive breast cancer cells. Oestrogen promotes the CDK4/6 activity and thus cell cycle progression, while in oestrogen deprivation there is an upregulation of alternative oestrogen-independent pathways that activate the CDK4/6 pathway [Citation8–10]. Therefore, CDK4/6 inhibitors are an important addition to endocrine therapy to delay endocrine resistance. Although with a pathophysiologic mechanism different from chemotherapy, cell cycle arrest by CDK4/6 inhibitors also induces cell death [Citation11,Citation12].

To our knowledge, no research has been done on the time needed to avert the threat of visceral crisis during treatment. Although different from time to avert this threat, time to objective tumour response according to RECIST 1.1. criteria may yet be considered as informative. In the PALOMA 2 and 3 trials, the median time to objective tumour response in patients with visceral disease treated with palbociclib combined with an aromatase inhibitor or fulvestrant was 4.3 and 3.8 months, respectively [Citation13]. The phase III PEARL study, comparing palbociclib plus exemestane or fulvestrant versus capecitabine in patients previously treated with aromatase inhibitors, showed comparable results in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) [Citation14,Citation15]. Although the PEARL study did not compare the treatment groups on rapidness of response, the overlapping PFS curves suggests a similar effectiveness. Two systematic reviews and network meta-analyses by Wilson et al. and Guilano et al. also show similar PFS and objective response rates for CDK4/6 inhibitors versus chemotherapy [Citation16,Citation17]. Recently, at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2022, the RIGHT choice study was presented, comparing ribociclib combined with an aromatase inhibitor versus chemotherapy of physician’s choice in patients with symptomatic visceral metastases, rapid disease progression or remarkably symptomatic non-visceral disease [Citation18]. Following the definition of visceral crisis from the MBC guideline of 2017, half of the patients enrolled in the RIGHT choice study were defined as having a visceral crisis, irrespective of treatment arm. The median PFS time for patients randomized to ribociclib plus endocrine therapy was 24.0 months versus 12.3 months for those treated with chemotherapy (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI):0.36–0.79, p = 0.0007). The objective response rates were 65.5% for ribociclib plus aromatase inhibitor therapy versus 60.0% for chemotherapy, with no statistically significant difference in median time to onset of response (4.9 vs. 3.2 months in ribociclib vs. chemotherapy (HR = 0.78 95%CI: 0.56–1.09)). These results suggest that starting a treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors is at least as good as chemotherapy, also for patients with a visceral crisis. However, no data were reported yet on the key question that is relevant for patients with an (imminent) visceral crisis, namely the time needed to avert the state of visceral crisis. Our cases show that based on clinical criteria a response was already seen after one cycle in three out of four patients, which was earlier than the formal radiologic assessment of response was done.

Several lessons can be learned from the four cases of patients with visceral crisis reported here. In case 1, 2 and 3 organ dysfunction was most clear. In case 1 the visceral crisis was caused by lymphangitis carcinomatosis in the lungs, in case 2 by rapidly arising ophthalmologic disease and case 3 also meets the criteria of lung visceral crisis. In case 4 the specific type of visceral crisis is harder to determine, but the rapid deterioration of performance status combined with extensive visceral disease fulfils the definition of the 3rd advanced breast cancer guideline [Citation3]. Overall, a fast and significant improvement of (imminent) organ failure is needed and was accomplished with a CDK4/6 inhibitor plus endocrine therapy in three out of four cases with visceral crisis. In case 3, the radiotherapy could have had an important role on the clinical response as well, but cannot explain the quick improvement in the lymphangitis carcinomatosis of the lungs. Case 4 was an exception, as further biochemical deterioration prevented the continuation of the CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy. The increasing elevation of transaminases and progressive pancytopenia could either be a therapy side effect or due to a progressive visceral crisis. The deteriorating lab results made continuation of systemic therapy challenging, both for chemotherapy and for CDK4/6 inhibitors. In 2 of 3 patients with a good clinical response, the patient was diagnosed with de novo metastatic breast cancer. Patients with de novo metastatic disease and the presence of both oestrogen and progesterone hormone receptors most likely have endocrine sensitive tumours. We could not find any research on time to response in de novo metastatic breast cancer patients. It could be hypothesised that treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors and endocrine therapy would lead to a better and faster response in treatment-naïve tumours, future research could further examine this. Altogether, we emphasise that in patients with visceral crisis the time needed to undo the state of visceral crisis is the most relevant outcome. The time needed to undo visceral crisis is merely based on clinical symptoms and laboratory findings, which is different from results presented in clinical intervention studies where responses are usually based on imaging and RECIST 1.1. criteria.

To conclude, we believe that CDK4/6 inhibitors combined with endocrine therapy can achieve a rapid response with better toxicity profile and quality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer experiencing visceral crisis. However, defining the state of (impending) visceral crisis and comparing patients with visceral diseases is complex. From our experience and the available information in studies, we believe that the (time to) response to CDK4/6 inhibitors may be satisfactory, except for patients with expected endocrine resistance or impaired oral or gastrointestinal function. The presented cases show that treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors can be considered in patients with visceral crisis, as chemotherapy is no longer the sole treatment option in patients with visceral crisis.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: VTH and WD; Resources; VTH, WD and MK; Investigation and original draft: MM and MV; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

MM reports institutional grants from Gilead. SG reports institutional grants from Novartis BV, Roche, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Astra-Zeneca and Gilead, and personal fees from Astra-Zeneca. VTH reports institutional grants and personal fees from Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, and Eli Lilly, and institutional grants from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo and Gilead. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this case report.

References

- Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, et al. ESMO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.019.

- Sbitti Y, Slimani K, Debbagh A, et al. Visceral crisis means short survival among patients with luminal a metastatic breast cancer: a retrospective cohort study. World J Oncol. 2017;8(4):105–109. doi: 10.14740/wjon1043w.

- Cardoso F, Costa A, Senkus E, et al. 3rd ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 3). Ann Oncol. 2017;28(1):16–33. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw544.

- Cardoso F, Paluch-Shimon S, Senkus E, et al. 5th ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 5). Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1623–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.010.

- Franzoi MA, Saúde-Conde R, Ferreira SC, et al. Clinical outcomes of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer: an 11-year single institutional experience. Breast. 2021;57:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.03.002.

- Yang R, Lu G, Lv Z, et al. Different treatment regimens in breast cancer visceral crisis: a retrospective cohort study. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1048781. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1048781.

- Zhao M, Ramaswamy B. Mechanisms and therapeutic advances in the management of endocrine-resistant breast cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5(3):248–262. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i3.248.

- Finn RS, Aleshin A, Slamon DJ. Targeting the cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK) 4/6 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0661-5.

- Ballinger TJ, Meier JB, Jansen VM. Current landscape of targeted therapies for Hormone-Receptor positive, HER2 negative metastatic breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:308. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00308.

- Spring LM, Wander SA, Andre F, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 inhibitors for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: past, present, and future. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):817–827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30165-3.

- Zhang J, Xu D, Zhou Y, et al. Mechanisms and implications of CDK4/6 inhibitors for the treatment of NSCLC. Front Oncol. 2021;11:676041. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.676041.

- Wagner V, Gil J. Senescence as a therapeutically relevant response to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Oncogene. 2020;39(29):5165–5176. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1354-9.

- Turner NC, Finn RS, Martin M, et al. Clinical considerations of the role of palbociclib in the management of advanced breast cancer patients with and without visceral metastases. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(3):669–680. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx797.

- Martín M, Zielinski C, Ruiz-Borrego M, et al. Overall survival with palbociclib plus endocrine therapy versus capecitabine in postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer in the PEARL study. Eur J Cancer. 2022;168:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.03.006.

- Martin M, Zielinski C, Ruiz-Borrego M, et al. Palbociclib in combination with endocrine therapy versus capecitabine in hormonal receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor 2-negative, aromatase inhibitor-resistant metastatic breast cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial—PEARL. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(4):488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.12.013.

- Giuliano M, Schettini F, Rognoni C, et al. Endocrine treatment versus chemotherapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1360–1369. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30420-6.

- Wilson FR, Varu A, Mitra D, et al. Systematic review and network meta-analysis comparing palbociclib with chemotherapy agents for the treatment of postmenopausal women with HR-positive and HER2-negative advanced/metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;166(1):167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4404-4.

- Lu Y-S, Mahidin EIBM, Azim H, et al. Abstract GS1-10: primary results from the randomized phase II RIGHT choice trial of premenopausal patients with aggressive HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer treated with ribociclib + endocrine therapy vs physician’s choice combination chemotherapy. Cancer Research. 2023;83(5_Supplement):GS1-10–GS1-10. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS22-GS1-10.