Abstract

The White-bellied Sea Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster (Gmelin JF, 1788) and Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus (Boddaert, 1783) are two resident coastal raptors from India through Australia. Data on the breeding landscape and nest spacing of these raptors in Southeast Asia are limited. In this study, field observations were conducted bimonthly from February 2012 to July 2013 on Penang Island and in Matang Mangrove Forest in Western Peninsular Malaysia. Nine types of landscape and 17 study areas were investigated, and habitat variables were analyzed using ArcGIS software. A total of 88 White-bellied Sea Eagle and 212 Brahminy Kite nests were located. Logistic regression analysis showed that the proportion (%) of forest land and urban areas was significantly different between study areas with and without nests (p < 0.05). By contrast, area size (ha), elevation (m above sea level), and distance to shore (m) had no significant differences (p > 0.05). The White-bellied Sea Eagle and Brahminy Kite preferred dipterocarp and mangrove forests, respectively. Nest spacing was analyzed for 75 White-bellied Sea Eagle nests (consisting of seven occupied and 68 unoccupied nests) in Penang National Park and 210 Brahminy Kite nests (consisting of 27 occupied and 183 unoccupied nests) in Matang Mangrove Forest. The average distance between the occupied nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle was 663.6 (± 377.3 standard deviation, SD, n = 7) m, whereas that of the Brahminy Kite was 1489.4 (± 1134.5 SD, n = 27) m. The proportion of nest occupancy to all nests was 9.3% for the White-bellied Sea Eagle and 12.8% for the Brahminy Kite. Conservation of islands covered with dipterocarp and mangrove forests is essential to the survival of coastal raptors in Southeast Asia.

Introduction

Studies on the breeding habitat of coastal raptors have focused mainly on the Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Hodges et al. Citation1984; Saalfeld & Conway Citation2010), Steller’s Eagle Haliaeetus pelagicus (Pallas, 1811) (Potapov et al. Citation2000), and White-bellied Sea Eagle (Emison & Bilney Citation1982; Thurstans Citation2009a). The White-bellied Sea Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster (Gmelin JF, 1788) and the Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus (Boddaert, 1783) reside in India through Southeast Asia to Australia (Birdlife International Citation2012a, Citation2012b). The White-bellied Sea Eagle inhabits coastal areas and nests in trees, on rocky ledges or on electricity pylons 10–50 m above the ground. The Brahminy Kite also inhabits coastal areas (Robson Citation2002), large estuaries, low-relief coasts (Wells Citation1999) and nests in trees that rise 5–25 m above the ground (Robson Citation2002).

Despite its large range, the White-bellied Sea Eagle has been studied primarily in Australia (Emison & Bilney Citation1982; Bilney & Emison Citation1983; Shephard et al. Citation2005; Thurstans Citation2009b). The few studies on the Brahminy Kite are mostly from India and Australia (Balachandran & Sakthivel Citation1992; Sivakumar & Jayabalan Citation2004; Lutter et al. Citation2006; Indrayanto et al. Citation2011). However, a wide range of both species can be found in Southeast Asia, where data on their breeding habitat and nest spacing are limited (Sarker Citation1986; Sarker & Iqbal Citation1988; So & Lee Citation2010; Indrayanto Citation2011; Masduqi Citation2011).

Thus, this study aims to understand the nesting habitat of the White-bellied Sea Eagle and Brahminy Kite in coastal areas of Southeast Asia. This study provides new information on the breeding landscapes and nest spacing of these species in Western Peninsular Malaysia.

Study areas

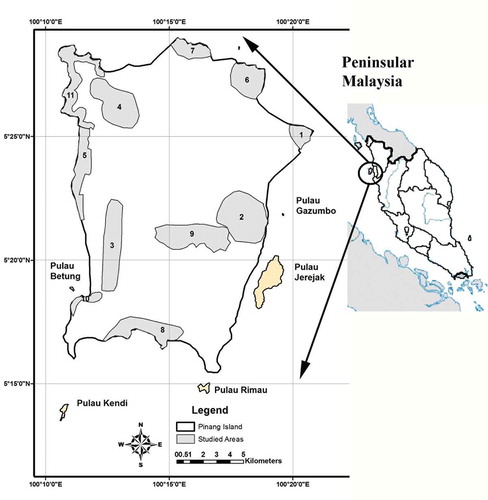

Field work was conducted in two areas on the west coast of the Malaysian Peninsula, namely, Penang Island and its associated islets () and Matang Mangrove Forest (MMF; ). Penang Island contains several nests of both White-bellied Sea Eagle and Brahminy Kite (Masduqi Citation2011), and MMF holds nests of the Brahminy Kite (Indrayanto Citation2011).

Figure 1. Penang Island, adjacent islets and study areas. Key to numbers: 1 = Georgetown; 2 = Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) and Gelugor; 3 = Balik Pulau; 4 = Teluk Bahang dam; 5 = mangrove forests; 6 = Tanjung Bungah; 7 = Batu Ferringgi; 8 = Teluk Kumbar; 9 = Balik Pulau to USM; 10 = Kampung Pakar Kapur; 11 = Penang National Park.

Penang Island (293 km2) is in Penang State in the northwest of Peninsular Malaysia (5°15' to 5°29' N and 100°10' to 100°21' E) (Masduqi Citation2011). The island is 26 km long and 10.7–19.7 km wide, and the highest point on the island is 795 m above sea level (a.s.l.) The study site has an average annual rainfall of 2670 mm and a monthly average temperature of 23.2–32.2°C (Anonymous Citation2012). Much of the island is hilly and covered with inland forest, with mangrove forests on the coast. Major forms of land use include fruit plantations, scrub, grassland, mining areas and urban areas (Masduqi Citation2011). However, most of the forests in the lowlands have been converted into agricultural land and urban settlements, and forests are mostly confined to upland areas (Ho et al. Citation1999). Most of the urban areas of Penang Island lie in the eastern part of the island. Several islets, including Pulau Jerejak, Pulau Kendi and Pulau Rimau, can be found around Penang Island ().

Penang National Park (PNP, Taman Negara Pulau Pinang) is located in the northwest of Penang Island (5°28 N, 100°10 E) (). It covers 2563 ha comprising 1182 ha of land, primarily coastal hill dipterocarp forests, coastal mangrove forests, sandy beaches and rocky shores, and 1381 ha of sea areas (Department of Wildlife and National Parks Citation2012). Throughout the PNP area, vegetation cover at high elevations consists primarily of emergent dipterocarp tree species of Shorea sp., Hopea sp. and Dipterocarpus sp., which are believed to be the preferred nesting sites of sea eagles (Masduqi Citation2011).

MMF (4°25' to 5°01' N and 100°25' to 100°45' E) is located approximately 10 km west of Taiping City in the State of Perak, Peninsular Malaysia. The mangrove forest covers approximately 40,466 ha (Muda et al. Citation2005), with an annual rainfall of 2000–2800 mm and a temperature of 33–22°C (Muda & Nik Mustafa Citation2003; Muda et al. Citation2005). MMF is believed to be the last remaining area with “natural” mangroves in Peninsular Malaysia. The forest is bordered by agricultural plantations, aquaculture ponds and other types of human development (Muda & Nik Mustafa Citation2003). There are several villages around the forest, including Kuala Gula to the north, Kuala Sepetang and Kuala Trong to the east and Kuala Kerang to the south.

Materials and methods

Field observations

Field studies were conducted from February 2012 to July 2013, which covered two kite/eagle breeding seasons (Robson Citation2002), to determine the nesting areas of the White-bellied Sea Eagle and Brahminy Kite. Twice-monthly surveys were undertaken by car and boat between 10:00 and 16:00. Various potential breeding landscapes were selected to identify suitable breeding habitats for the species. Nine types of habitats from virgin forests to urban areas and 17 study areas were investigated to search for nests of these species. These locations were scattered throughout Penang Island, including adjacent islands, in addition to MMF (). During our field surveys, we were assisted by local people and park rangers who were highly skilled in finding eagle nests.

Table I. Characteristics of the study areas and nest numbers of the White-bellied Sea Eagle and Brahminy Kite on Penang Island (and adjacent islets) and in Matang Mangrove Forest.

Nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle were identified by their large size (approximately 100 cm in width), the presence of adults and juveniles, and the lack of any other large raptor species in the vicinity. Nests of the Brahminy Kite were identified in a similar manner. The White-bellied Sea Eagle is the most common breeding raptor in PNP and the Brahminy Kite in MMF (Indrayanto Citation2011; Masduqi Citation2011). Therefore, unoccupied nests in these areas were identified based on the same sizes of nests among occupied nests, built on the same tree species and at the expected height range, in addition to temporary occupation by adults during the study period visits. Other individual nests were approved by observation of adults and juveniles. Observations of all raptors were recorded. Nest locations were determined by handheld global positioning system (GPS; Garmin GPS 60). Doubtful nests were not included in the results.

Data analysis

In each study area, five points (i.e., north, east, south, west and center) were randomly selected, and elevation (m a.s.l.) and distance to shore (m) of each point and average for each study area were obtained using SPOT 5 Imagery. Area size of a sampled area (ha), the proportion of forest land to total area (%) and the proportion of urban areas to total area (%) were also calculated for each study area.

Distribution of nests was mapped using ArcGIS 9.3 geographic information system (GIS) software. Data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0 software. Binary Logistic Regression was performed to find effective variables through multivariate analysis (method Enter) for study areas that had at least one nest (compared with study areas without any nest).

We studied nest spacing of the White-bellied Sea Eagle in PNP where a large breeding population of this species occurs. Similarly, the study of nest spacing of the Brahminy Kite was focused on MMF. However, all occupied and unoccupied nests were considered for breeding landscape and nest spacing for both species. Euclidean distance analysis (test of distribution ranging from clustered to dispersed) was conducted with ArcGIS 9.3 software.

Kite and eagle territories can have alternative nests or nests from different years (Emison & Bilney Citation1982). We counted the number of clumped or clustered nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle that occurred in the study areas. These nests were located within a 100-m radius of each other, which is the usual breeding territory of a pair during different breeding seasons (Emison & Bilney Citation1982).

Results

Breeding landscape

Seventeen study areas were characterized by nine types of landscapes, which ranged from pristine forest to urban areas (, ). All nests (n = 88) of the White-bellied Sea Eagle were in dipterocarp forests and 211 of the 212 Brahminy Kite nests were in mangrove forests (). Inland forests and forests surrounded by urban areas were not suitable for the breeding of these species. Of the located White-bellied Sea Eagle nests, 75 were in PNP on Penang Island, eight on Pulau Kendi (southwesternmost of Penang Island), four on Pulau Jerejak (east of Penang Island) and one on Pulau Rimau (southeasternmost part of Penang Island) (). Three cases of double nests (two nests on the same nest tree) were recorded (one case on Pulau Kendi and two cases in PNP) (). Two hundred ten Brahminy Kite nests were found in MMF, of which one was on Pulau Rimau and another was on mangroves in Balik Pulau south of PNP (). Logistic regression analysis showed that the variables of proportion of forest land (%) and urban areas (%) were significantly different between study areas with and without nests (p < 0.05). By contrast, area size (ha), elevation (m) and distance to shore (m) showed no significant difference (p > 0.05). shows the linear regression of the variables forest land and urban areas with total nest numbers of both species.

Nest spacing

White-bellied Sea Eagle

A total of 75 nests were found on 73 nest trees in PNP on Penang Island (). Two nest trees had double nests. On average, the nearest neighbour distance for all nest trees was 143.4 (± 112.7 standard deviation, SD) m apart in PNP. When only the nests located within a 100-m radius of another nest were considered, we identified 36 single nests and 12 clumps of nests containing 39 nests (). Only seven of the 75 nests in the PNP showed breeding activity during the study period (each nest at least two times), giving a nest occupancy proportion of 9.3%. In addition, only three occupied nests were placed within the clumped nests, whereas nine clumped nests were left with no occupied nest. The average distance between neighboring occupied nests was 663.6 (± 377.3 SD) m. However, Euclidean distance analysis showed that all nest trees were significantly clustered (Nearest Neighbor Ratio = 0.683, Z score = –5.041 (SD), p < 0.01).

Brahminy Kite

A total of 210 nests of the Brahminy Kite were found in MMF (), 27 of which were occupied and 183 were unoccupied, giving a nest occupancy proportion of 12.8%. Up to 84% of the kite nests were within 500 m of neighboring nests. The average neighboring nest for the occupied nests was 1489.4 (± 1134.5 SD) m away. Euclidean distance analysis confirmed that all nest trees were clustered [Nearest Neighbor Ratio = 0.29, Z = –19.31 (SD), p < 0.01]. Among four forestry divisions of MMF, the highest nest number was observed in the northern part of Kuala Sepetang (68 nests).

Discussion

Breeding landscape

Historical and contemporary factors in a multi-scale approach can provide current distribution of the White-bellied Sea Eagle (Shephard Citation2004). However, no historical data on these species are available in Malaysia. The results of our study showed that both species nest in coastal areas (, –).

The White-bellied Sea Eagle occupies mostly coastal areas rather than inland waters (Shephard et al. Citation2005) and islands rather than the mainland (Dennis et al. Citation2011). Although all types of shorelines and large estuaries, including lower-relief coasts backed by mangrove and peatswamp forests, have been breeding grounds of the species (Wells Citation1999), only dipterocarp rainforests have been chosen by the White-bellied Sea Eagle for breeding. All of the nesting habitats on Penang Island and adjacent islands are on offshore islands far from the Peninsular Malaysian coast () (Dennis & Lashmar Citation1996). All nests on the Penang islands were built in dipterocarp forests where tall emergent trees habituate (Wells Citation1999). However, the results of our study showed that both species avoid urban areas. The White-bellied Sea Eagle builds its nests at least 320 m away from human habitation (Thurstans Citation2009a), and nest sites selected by the Bald Eagle are habitats farther from human activity and disturbance (Andrew & Mosher Citation1982).

We observed that the Brahminy Kite preferred mangrove forests for breeding (). Although it inhabits coastal areas (Robson Citation2002), large estuaries and low-relief coasts (Wells Citation1999), the primary habitat of the species is broad, muddy, mangrove-backed intertidal flats (Wells Citation1999). The Brahminy Kite seems dependent on vast mangrove forests, at least in the Sundarbans and MMF (Sarker Citation1986; Indrayanto Citation2011).

We also found that all nests of both species were built in trees. The White-bellied Sea Eagle builds its nests in trees, on rocky ledges or on pylons (Robson Citation2002). Although a few examples of potential nest sites other than trees can be found outside PNP (three cases of pylons in the south) and on Pulau Kendi (one case of rocky ledge), none of them were used as a nest site.

Nest spacing

Coastal raptors, such as ospreys (Pandion spp.) and sea eagles (Haliaeetus spp.), may occasionally nest in loose colonies or congregate in feeding areas. Thus, the nest spacing of different raptors varies from less than 200 m to more than 30 km apart in suitable habitats (Newton Citation1979). The proportion of occupied nests of different species varies among different nests and nesting territories (Thurstans Citation2009b). It also varies even for the nests of one species; for example, the proportion of occupied nests of the Wedge-tailed Eagle Aquila audax (Latham, 1802) varies from 22.5% (Silva & Croft Citation2007) to 57.5% (Sharp et al. Citation2001).

In our study, we found three cases of double nests on Penang Island and adjacent islets. Such an interesting phenomenon was not mentioned in the literature (Bilney & Emison Citation1983; Dennis & Lashmar Citation1996; Dennis Citation2004; Debus Citation2005; Shephard et al. Citation2005; Spencer & Lynch Citation2005; Dennis & Baxter Citation2006; Corbett & Hertog Citation2011; Masduqi Citation2011) although S. Thurstans (unpublished data) provided anecdotal evidence of double nesting.

PNP had lower nest spacing and higher density than its surrounding areas on Penang Island. This finding indicates the densest spacing for the White-bellied Sea Eagle compared with previous studies. In contrast to the assumption of one active nest in each clumped nest, only three of the 12 clumped nests in this study showed breeding activity.

The nearest distance between neighboring nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle varies from 0.9 km (Corbett & Hertog Citation2011) to 10.3 km (Dennis et al. Citation2011). In our study, the average distance to the nearest conspecific nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle was approximately 143.4 m for all nests and 663.6 m for occupied nests. In the Furneaux and Hunter groups, Tasmania, nests were 3–5 km apart (Mooney Citation1986). In Tasmania, the nearest distance between nests ranged from 4.4–9.5 km, with an average of 6.6 km (Thurstans Citation2009a). In the subtropical Northern Territory of Australia, White-bellied Sea Eagle nests were 0.9 and 6.5 km apart (Corbett & Hertog Citation2011). Looser nest separation has been observed in the Nuyts Archipelago, western Eyre Peninsula (9.7 km, n = 8), and on Sir Joseph Banks Group, Spencer Gulf (10.3 km, n = 5), both on the southeast coast of Australia (Dennis et al. Citation2011).

According to the landscape ecological perspective, the nest dispersion of raptors is affected by two factors: availability of nest sites and food resources (Newton Citation1979). The availability of food resources (Marchant & Higgins Citation1993), availability of optimal foraging habitats (Sergio et al. Citation2006) and abundance of the eagles’ main prey items, including fish (Robson Citation2002; Hoff et al. Citation2004), affect the breeding performance of eagles. In general, the availability of nest trees is not a limiting factor in PNP. Instead, food could be a limiting resource for the current number of breeding pairs (Newton Citation1979) in the park, as evidenced by the lack of any sign of intraspecific competition for nest sites during the field surveys we conducted.

We observed that only seven nests of the White-bellied Sea Eagle were occupied among 12 clumped nests and 36 single nests. The proportion of nest occupancy for all nests (9.3%) was lower than the proportion (38.7%) for all nests surveyed in Tasmania (Thurstans Citation2009b). This finding was also applicable to nesting territories because 14.6% of clumped and single nests were occupied in PNP, whereas 77.5% of nesting territories were occupied in Tasmania (Thurstans Citation2009b). No previous studies on the nest spacing of the Brahminy Kite are available. Therefore, the results of this study have no counterparts for comparison. However, further research is necessary to determine more precisely the distance between active nests and the distance between alternative nests within clumps of nests.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial and logistic support provided by the School of Biological Sciences and RU-Research Grant (815075), Universiti Sains Malaysia. Our special thanks go to Mr. Kalimuthu Subramanian and Mr. Norodin Ahmad for assisting us during our field surveys. We are extremely thankful to Dr. Michael McGrady for reviewing and editing an earlier draft of our manuscript. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers who suggested invaluable comments.

References

- Andrew JM, Mosher JA. 1982. Bald Eagle nest site selection and nesting habitat in Maryland. The Journal of Wildlife Management 46:382–390. doi:10.2307/3808650.

- Anonymous. 2012. Penang Island. Available: http://www.reference.com/browse/Penang. Accessed Jul 2012 05.

- Balachandran S, Sakthivel R. 1992. Site-fidelity to the unusual nesting site of Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society 91:139.

- Bilney RJ, Emison WB. 1983. Breeding of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle in the Gippsland Lakes Region of Victoria, Australia. Australia Birdwatcher 10:61–68.

- Birdlife International. 2012a. Haliaeetus leucogaster. IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1. Available: http://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed Jul 2012 06.

- BirdLife International. 2012b. Haliastur indus. IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. Available: http://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed Nov 2012 26.

- Corbett L, Hertog T. 2011. Diet and breeding of White-bellied Sea-Eagles Haliaeetus leucogaster in subtropical river habitats in the Northern Territory, Australia. Corella 35:41–48.

- Debus S. 2005. White-bellied Sea-eagles breeding in the Australian Capital Territory? Canberra Bird Notes 30:146–147.

- Dennis TE. 2004. Conservation status of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Osprey and Peregrine Falcon on western Eyre Peninsula and adjacent offshore islands in South Australia. South Australian Ornithologist 34:222–228.

- Dennis TE, Baxter CI. 2006. The status of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and Osprey on Kangaroo Island in 2005. South Australian Ornithologist 35:47–51.

- Dennis TE, Detmar SA, Brooks AV, Dennis HM. 2011. Distribution and status of White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, and Eastern Osprey, Pandion cristatus, populations in South Australia. South Australian Ornithologist 37:1–16.

- Dennis TE, Lashmar AFC. 1996. Distribution and abundance of White-bellied Sea-Eagles in South Australia. Corella 20:93–102.

- Department of Wildlife and National Parks. 2012. Penang National Park. Peninsular Malaysia: Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP). pp. 21.

- Emison WB, Bilney RJ. 1982. Nesting habitat and nest site characteristics of the White-Bellied Sea-Eagle in the Gippsland Lakes Region of Victoria, Australia. Raptor Research 16:54–58.

- Ho M, Chuan AS, Ooi J, Fah QL. 1999. Selected Nature Trails of Penang Island. Malaysian Nature Society, Penang Branch. Unpublished report.

- Hodges JIJ, King JG, Davies R. 1984. Bald Eagle breeding population survey of Coastal British Columbia. The Journal of Wildlife Management 48:993–998. doi:10.2307/3801455.

- Hoff MH, Meyer MW, Van Stappen J, Fratt TW. 2004. Relationships between bald eagle productivity and dynamics of fish populations and fisheries in the Wisconsin waters of Lake Superior, 1983–1999. Journal of Great Lakes Research 30(SUPPL. 1):434–442. doi:10.1016/S0380-1330(04)70404-9.

- Indrayanto P. 2011. Distribution and breeding behaviour of Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus) on Penang Island and Matang mangrove forest reserve, Kuala Sepetang, Perak. MSc thesis, School of Biological Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- Indrayanto P, Latip NSA, Mohd Sah SA. 2011. Observations on the nesting behaviour of the Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus on Penang Island, Malaysia. Australian Field Ornithology 28:38–46.

- Lutter H, McGrath MB, McGrath MA, Debus SJS. 2006. Observation on nesting Brahminy Kites Haliastur indus in Northern New South Wales. Australian Field Ornithology 23:177–183.

- Marchant S, Higgins PJ. 1993. Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Vol. 2. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Masduqi MS. 2011. Predicting the habitat selection and distribution of raptors using Geographic information System technique: A case study with the White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster. Pulau Pinang Malaysia: Universiti Sains Malaysia.

- Mooney NJ. 1986. Sea eagles’ greatest problem is nest disturbance, says NPWS. Fishing Industry News Tasmania 9:39–41.

- Muda A, Mat Isa AZ, Lim KL. 2005. Sustainable management and conservation of the Matang Mangrove in sustainable management of Matang Mangrove: 100 years and beyond. Kuala Lumpur, Peninsular Malaysia: Forestry Department.

- Muda DA, Nik Mustafa NMS. 2003. A working plan for the Matang Mangrove Forest Reserve, Perak. Fifth revision- The third 10-year period (2000–2009) of the second rotation. Perak Darul Ridzuan, Malaysia: State Forestry Department. 320 pp.

- Newton I. 1979. Population ecology of raptors. Berkhamsted, UK: T & AD Poyser.

- Potapov E, Utekhina I, McGrady MJ. 2000. Habitat preferences and factors affecting population density and breeding rate of Steller’s Sea Eagle on Northern Okhotia. In: Ueta M, McGrady MJ, editors. First symposium on Steller’s and White-tailed Sea Eagles in East Asia. Tokyo, Japan: Wild Bird Society of Japan. pp. 59–70.

- Robson G. 2002. A field guide to the birds of South-East Asia. London, UK: New Holland Publishers.

- Saalfeld ST, Conway WC. 2010. Local and landscape habitat selection of nesting Bald Eagles in East Texas. Southeastern Naturalist 9:731–742. doi:10.1656/058.009.0408.

- Sarker SU. 1986. Population dynamics of raptors in the Sundarban forests of Bangladesh. Birds of Prey Bulletin 3:157–162.

- Sarker MSU, Iqbal M. 1988. Breeding biology of Brahminy Kite (Haliastur indus indus) (Boddaert). Bangladesh Journal of Zoology 16:241.

- Sergio F, Pedrini P, Rizzolli F, Marchesi L. 2006. Adaptive range selection by golden eagles in a changing landscape: A multiple modelling approach. Biological Conservation 133:32–41. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.05.015.

- Sharp A, Norton M, Marks A. 2001. Breeding activity, nest site selection and nest spacing of Wedge-tailed Eagles (Aquila audax) in western New South Wales. Emu 101:323–328. doi:10.1071/MU00054.

- Shephard JM. 2004. A multi-scale approach to defining historical and contemporary factors responsible for the current distribution of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster (Gmelin, 1788) in Australia. Australia: Griffith University.

- Shephard JM, Catterall CP, Hughes JM. 2005. Long-term variation in the distribution of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) across Australia. Austral Ecology 30:131–145. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2005.01428.x.

- Silva LM, Croft DB. 2007. Nest-site selection, diet and parental care of the Wedge-tailed Eagle Aquila audax in Western New South Wales. Corella 31:23–31.

- Sivakumar S, Jayabalan JA. 2004. Observations on the breeding biology of Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus in cauvery delta region. Zoos’ Print Journal 19:1472–1474. doi:10.11609/JoTT.ZPJ.1025.1472-4.

- So IWY, Lee WH. 2010. Breeding ecology of White-bellied Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus leucogaster) in Hong Kong- A review and update. Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department Newsletter 18:1–8.

- Spencer JA, Lynch TP. 2005. Patterns in the abundance of White-bellied Sea-Eagles (Haliaeetus leucogaster) in Jervis Bay, south-eastern Australia. Emu 105:211–216. doi:10.1071/MU04030.

- Thurstans SD. 2009a. Modelling the nesting habitat of the White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster in Tasmania. Corella 33:51–65.

- Thurstans SD. 2009b. A survey of White-bellied Sea-Eagle Haliaeetus leucogaster nests in Tasmania in 2003. Corella 33:66–70.

- Wells DR. 1999. The birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, covering Burma and Thailand South of the eleventh parallel, Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Vol. 1. Non-passerines. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.