ABSTRACT

Using questionnaire data collected from one gym in 1995, 2005, and 2015 this study examines 861 women’s and 1827 men’s training patterns and their motives for weight training. Between 1995 and 2015, the gym increased its membership, equipment, and machines. The analysis shows that the participants increased the time they trained in gyms and changed the muscle groups they prioritized. The motives to become stronger, healthier, and more fit remained stable over time, but both the men’s and women’s training de-emphasized building muscles and firmer shapes and emphasized fun, attractiveness, and endurance. The analysis suggests that how the socially constructed body should be shaped and the goal with the shaping has changed. In conclusion, the 20-year perspective captures changes that have not been reported previously and contributes to knowledge about the intersection of gyms and gender, shedding light on how gym culture has changed and the reasons for these changes.

Introduction

Drawing on questionnaire data from 1995, 2005, and 2015, this study examines training patterns, motivations for training in a gym, and whether these patterns and motivations have changed during this 20-year period. The interest in training with weights at a gym has increased in Sweden since the 1970s (Söderström Citation1999). Between 1970 and the 1990s, the number of gyms increased in Sweden. In 1990, there were 350 000 active gym-goers (Johansson Citation1998) and the gym and fitness market continued to grow (+41.5%) between 1998 and 2003 (The Swedish Sports Confederation Citation2003). According to the Swedish Sports Confederation (Riksidrottsförbundet), training with weights increased more than other types of training offered by gyms, especially for women (2004). In a study from 2011, the Swedish Sports Confederation found that 2.6 million Swedes trained with weights regularly (The Swedish Sports Confederation Citation2011). Since then, the gym and fitness market has continued to grow markedly in terms of number of gyms, the number of people training at gyms, and the number of people working in the fitness industry (Andreasson and Johansson Citation2014; Neville and Gorman Citation2016; Sassatelli Citation2016). According to the Swedish business registry, the number of commercial gym companies, not including community gyms, school gyms, company gyms etc., increased from 212 to 825 between 2008 and 2020 (Statistics Sweden Citation2020). As the number of gyms has increased, so has the number of new training methods (e.g. CrossFit and kettlebells) as well as the number of machines, developments that have created more possibilities for strength and endurance training (e.g. Sibley and Bergman Citation2018).

This growth in gym training goes beyond the borders of Sweden. Rojas (Citation2016), in a study of the gym culture in Europe and South America, found that the gym market continues growing even in countries such as Chile where leisure time and sport participation or physical activity in general is low. Similarly, a study of Norwegian youth shows an increase in the participation rate in strength training between 1997 and 2007 (Green, Thurston, and Vaage Citation2015). In addition, Storm and Hansen (Citation2019) found that the number of fitness centres in Denmark has increased over the last decade (see Fisher, Berbary, and Misener Citation2018).

The worldwide growth of gyms and the interest in working out in gyms illustrate that training in commercial gyms is now a significant part of many people’s lives. As the gym market has grown, health has become an increasingly important issue for various sectors of society (e.g. Blair Citation2009; World Health Organization Citation2012). The interest in gym training seems related to the growing interest in health. However, this connection does not seem to explain the marked increase in gym training solely from a collective idea that strength training is the most effective physical activity to be healthier or counteract health problems. Other aspects may help explain the interest in gym training. Research suggests that training at a gym is more than physical training – it is about a consumer culture, which has steadily grown since the 1980s, where consumption, style, and symbolic values are tied to gym culture (e.g. Horton, Ferrero-Regis, and Payne Citation2016; Klein Citation1993; Rojas Citation2016; Sassatelli Citation2016; author). From this perspective, the body is seen as an investment that can be shaped according to what is desirable and an individual’s responsibility for his or her physical health (e.g. Featherstone Citation2010; Fisher, Berbary, and Misener Citation2018). In addition, the body and the symbolic signs the body conveys (e.g. success, beauty, and character) play a major role in understanding the growing interest in gym training (e.g. Featherstone Citation2010; Halliwell, Dittmar, and Orsborn Citation2007; Turner Citation1996).

Research on motives for gym training, which is central to this study, has shown that people have many reasons for joining gyms, continuing to train at gyms, and choosing particular training routines. Quantitative studies show that central motives for gym training are related to physical appearance and health. For example, Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016 show that university students are motivated to train at a fitness centre to improve their health, muscular development, fitness, and body satisfaction as well as to establish a daily routine and increase mental relaxation (Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016). Lim et al. (Citation2012), in a study of male gym participants, show that an attractive body and health consciousness were strongly related to training at a gym. In another study using the same dataset, Lim et al. (Citation2013) found that training at a gym was related to a desire to improve one’s physical attractiveness and health, media’s influence on body image, and the need for socialization. Other studies have shown that people’s perceptions of their body influences their choice of exercise routines. Caudwell and Keatley (Citation2016) show that losing weight to improve one’s body image was a both strong motivating force for training in a gym and for training per week. Male gym participants with higher negative attitudes towards their body fat (i.e. body image) trained more often. Similarly, Urbonavicius, Janonyte, and Amirebayeva Reardon (Citation2019) found that females who think more often about their appearance combined with a belief that it is possible to achieve a better looking body are more likely to use fitness services. However, Pope and Harvey (Citation2015) found that university students’ motivation to regularly train at a fitness centre to manage their weight (i.e. probably a body image motive) decreased over two semesters, probably as a result of changing priorities and motivations over the two semesters.

Quantitative studies comparing the motivations of men and women, which is a particular focus in this study, to train in gyms have produced inconsistent results. Zach and Adiv (Citation2016), for example, found no significant differences between men and women regarding motivations such as appearance, weight management, and muscular development. However, they did find differences related to which muscle groups men and women prioritize. For example, compared to women, men placed more emphasis on development of the upper body and a majority of the women trained with relatively lighter weights than men, a result that they attribute to gender norm perceptions regarding strength training. However, McCabe and James (Citation2009) found significant differences between men’s and women’s motives for training in fitness centres: women are motived to improve fitness and lose weight, whereas men are motivated to improve fitness and increase muscle development. To date, quantitative research only superficially compares female and male motivations. In some cases, the analyses have considered gender issues in relation to consumer cultural values (e.g. desirable masculinity ideal) or psychological perspectives (e.g. intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation). Furthermore, most studies ignore training patterns – e.g. muscles trained and cardiovascular training – and therefore have not included these in the analyses of motives. Therefore, these studies provide a snapshot of people’s motives at a given time but provide little information about differences between sex and changes in motives over time, and the relationship to the general growth in gym training.

Previous qualitative studies found similar motives as the quantitative studies, but qualitative studies deepen the analysis and include, for example, what continuous training at the gym means for people’s motivation to train. Crossley’s (Citation2006) ethnographic study of a gym in the UK examined why people start and continue training at a gym. Crossley found that athletes train at a gym to enhance performance or recover from injury, whereas non-athletes typically start training at a gym to lose weight, improve musculature, and increase fitness. Crossley argues that a key reason for starting to train at a gym is the desire to recover a body (e.g. to become healthier and fitter) they once had. However, Crossley (Citation2006) notes that people are motivated to train at a gym to maintain an enjoyable routine that promotes a sense of well-being and relaxation (i.e. to counteract work-related tiredness and stress) although issues related to body image are also important. New motives for regular gym-goers, in Crossley’s words, ‘become available in the course of the gym career’ (46) as a consequence of learning to like the training as well as a transformed sense of the self. This routine also boosts the experienced gym-goer’s self-esteem and confidence. This physical and psychological well-being motive is also evident in other studies. Dogan’s (Citation2015) interview study of gym participants found that people were motivated to start gym training to improve fitness as well as to improve daily work performance and psychological well-being. He relates these motives to a desire and responsibility to create an optimized self – a version that is better, fitter, and stronger (453). Similarly, Stewart, Smith, and Moroney (Citation2013), in an interview study of male and female regular gym-goers, found that the gym-goers started training as the result of critical self-perceptions of their body although men more likely wanted to build muscle mass and women more likely wanted to develop a more lean and toned body. Although improving one’s physique and physical functioning are important to gym-goers, improving one’s emotional health and cognitive abilities were also associated with training (Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013).

In addition, Neville and Gorman (Citation2016), in their interview study of 12 experienced male and female gym-goers, found that a functioning body and health benefits were more motivating and meaningful than bodily appearance. Rojas (Citation2016) study of gyms in Chile and the Netherlands found that males mainly emphasized improving their physical appearance and health and women mainly emphasized health rather than physical appearance. However, in both countries, people hoped, as noted in other studies, to develop a functional body and a competent body as defined by their culture so as to improve their daily lives. That is, Rojas found that culture influences how people value physical appearance. Likewise, Maguire and Mansfield (Citation1998) found that cultural values regarding female physical appearance motivated women to participate in aerobic training. These women expressed a desire to lose weight, to be slim, and to have a toned physique, characteristics associated with what culture deems a beautiful body, although they also expressed that their aerobic training was an enjoyable routine that generates a sense of well-being and relaxation. In a study of women participating in aerobics, Markula (Citation1995) found that this desired toned physique is particularly related to training the lower body and achieving a non-masculine muscular ideal (cf. Coen, Rosenberg, and Davidson Citation2018). For the women, however, weight loss is more desirable than a firm body.

Compared to the quantitative studies, these qualitative studies extend the understanding of gym goers’ motives as they analyse the relationship between initial motives for starting to train (e.g. improving one’s body) and what the training successively means for them (e.g. routines). In addition, the qualitative studies draw attention to differences between males and females as well as between people’s motives in the context of broader discourses relating to health and fitness, although Crossley (Citation2006) notes that understanding gym training does not require exclusively emphasizing consumer culture. However, it is worth noting that in some studies where both men and women have been interviewed, comparisons were not made (e.g. Dogan Citation2015) or any analytical focus on gender norms (Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013). Nevertheless, as with the quantitative studies, these qualitative studies give little information of the relationship between training patterns and motives and the relationship to the general growth in gym training.

Research is not in agreement about the socializing dimension of gym training. For example, Damásio, Campos, and Gomes (Citation2016) found that socializing with others was the least important motive, whereas Lim et al. (Citation2013) found a positive relationship between socializing with others and training in a gym. Similarly, Crossley’s (Citation2006) study shows that gyms for experienced users have become a place for social interaction, whereas Stewart, Smith, and Moroney (Citation2013) found a greater ambivalence regarding the gym’s social dimension. In addition, Burke, Carron, and Eys (Citation2006) found that the least preferred option for both aerobic and weight training for females was to be alone, whereas the least preferred option for males was to participate in a structured class setting. This difference between sex was also evident in Rojas’ (Citation2016) study: women to a greater extent than men socialized at the gym. Cardone’s (Citation2019) ethnographic study of how gyms influence integration of people adds to the understanding of the social dimension by highlighting that training habits and times for training have binding effects for gym goers. That is, the social dimension seems to be related to people’s training habits and gym routines.

In the more theoretically-driven analyses of gym-goers’ motivations, the symbolic signs the body conveys are more important for understanding the attraction of gym training. For example, the empirical findings presented here about the chief motives such as muscular development, fitness, and attractiveness, although the strength of them vary between studies, are argued to be associated with maintaining a youthful and firm body as represented in the media (e.g. Sassatelli Citation1999; Wright, O’Flynn, and Macdonald Citation2006) and that the ‘pursuit of the ‘body beautiful’ is intertwined with a cultural distaste for fat and the desire to control the body according to social norms of femininity’ (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998, 135). Here, Maguire and Mansfield draw attention to a gender dimension that, as the literature presented above shows, has not been in the foreground in research on gym-goers’ motives, although it has been a central theme in gym and fitness research in general. In such studies, the empirical data consider people’s motives for exercising, without focusing solely on them, to understand the contemporary cultivation of the body in the gym and fitness industry from a gender perspective. Clearly, questions about gender in gym culture are related to consumer cultural style and symbolic values (e.g. Johansson Citation1996; Markula Citation1995). Within this research, studies since the 1990s have, for example, analysed the gym as a place for the construction of gender identity (Johansson Citation1996), power relations, and values of femininity (Markula Citation1995; Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998). More recently, the focus has been on gendered socially-constructed thresholds that influence where men and women train in a gym (Bladh Citation2020; see also Clark Citation2017) and visceral geographies and structures of power in the gym (Coen, Davidson, and Rosenberg Citation2020).

In summary, irrespective of methodological approach, the reviewed studies show that there are many motives for training in a gym, but some of these are more fundamental such as improving one’s physique, increasing strength, improving fitness, increasing attractiveness, and improving overall physical and psychological health (e.g. Crossley Citation2006; Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016; Lim et al. Citation2012; Zach and Adiv Citation2016). However, research has not arrived at consensus concerning the social dimension as a motivator for gym training. The studies suggest that body-related motives, although the value and strength of them vary in the studies, are constantly present. Over the last several decades, interest in gym training has expanded markedly and what was previously reserved for body-builders has increasingly become the domain of all gym goers. However, questions about the relationship between this growth of gym training and women’s and men’s motives for gym training has yet to be examined empirically. Quantitative cross-sectional studies have explored chief motives, and qualitative studies have added in-depth explorations of the meaning making attached to gym training, but previous research has, more or less, ignored training patterns, comparisons between males and females, as well as changes over a longer time, although researchers have called for studies that investigate gym-goers from a time perspective (e.g. Caudwell and Keatley Citation2016; Halliwell, Dittmar, and Orsborn Citation2007; Lim et al. Citation2012). The lack of a time perspective also contributes to the fact that we have limited knowledge about the relationship between training patterns and motives and the relationship to the general growth in gym training within contemporary consumer culture. These shortcomings contribute to the lack of knowledge about how, for example, whether particular forms of physical capital or masculinity and femininity are related to the growth in gym training.

This study supplements the knowledge about what motivates people to train in a gym by presenting new data and analyses of this data. That is, this study’s longer time perspective (i.e. relative to previous studies) provides useful information regarding the expanding gym culture and the differences between the way women and men train at gyms. Questions remain about changes in motivations and training routines within gym culture as well as about whether and how people’s motivations and training routines are embedded in and shaped by consumer cultural values since the 1990s, questions that have motivated this study. Drawing on questionnaire data from 1995, 2005, and 2015, this study empirically examines women’s and men’s gym training patterns and their motives for training at a gym. That is, this study contributes to knowledge of gym-goers in the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s and whether and how training patterns and motives for female and male gym-goers have changed during this period. Therefore, this study contributes to knowledge about the intersection of gyms and gender and sheds light on whether, how, and why gym culture has changed.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from questionnaires from the same gym completed in 1995, 2005, and 2015. All individuals completed the questionnaires when they entered the gym to train with weights and machines. Data were collected during the same month of the year from the morning until close over two days in 1995 and one day in 2005 and 2015. In total, 2688 gym participants (1827 men and 861 women) completed the questionnaires (). The respondents completed the questionnaires at the gym and the completion time was about 20 min.

Table 1. Data collection 1995, 2005, and 2015.

The questionnaire

The 1995 questionnaire was part of a larger study of the gym culture (Söderström Citation1999). The questionnaire was not designed for a longitudinal study instead the time perspective has evolved over time and the questionnaire has been modified after the 1995 data collection. The questionnaire was designed to capture training patterns and motives. In the first part of the questionnaire, the participants were asked to identify their age, gender, and previous sport participation in childhood and adolescence. In addition, they noted how many years they had trained at the gym, how many hours they train per week, what exercises other than gym training they engage in, and which muscles they prioritize in their training. However, the question about the muscle groups they prioritized was written differently in the 2005 and 2015 study: in 1995 the participants ranked the priority they gave to each muscle (first, second, etc.) and in 2005 and 2015 the participants marked the priority they gave to each muscle group on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = low and 5 = high).

In the second part of the questionnaire, the participants’ motives for training at the gym were captured on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 5 (very important). The 1995 questionnaire used a seven-point Likert-type scale that was adapted to a five-point scale. After the 1995 data collection, the 2005 and 2015 questionnaires were modified to include more motives for training. As the 1995, 2005, and 2015 questionnaires had ten overlapping motives for training, the comparisons between the three decades are based on these ten overlapping motives.

The development of the 1995 questionnaire was based on several months of observations of the gym and the people who trained there. The observations revealed many types of people training, many training routines, and many ways gym-goers interacted, raising questions about their motives for training: Did they train to become stronger, to gain more muscles, to socialize, etc? In the final phase of the construction of the questionnaire, the derived questions from the observations were compared with and inspired by a large Swedish lifestyle and health study (Engström et al. Citation1993). The questionnaire gathered information about the following ten motives: strength; muscles; attractiveness; health; socializing; enjoyment/fun; endurance/cardiovascular; firmer shapes; fitness (well-trained); and location (indoors). Subsequent studies of people’s motives in relation to exercise behaviour or gym training have also used these items, which were developed in the original 1995 questionnaire (Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016; Halliwell, Dittmar, and Orsborn Citation2007; Ingledew and Markland Citation2008; Loze and Collins Citation1998; Maltby and Day Citation2001).

After being informed of research ethics, all the respondents agreed to participate. The investigation followed ethical principles of research and no questions were considered ethically sensitive.

Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate differences between years and gender for the ten motives. Descriptive statistics and independent t-tests were used to compare groups (men and women) for each year (1995, 2005, and 2015) with respect to the ten motives. To adjust for multiple comparisons (t-tests), the P-value was set to 0.01. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0.

Results

The gym

The gym, which includes the weight training area, is part of a larger independent fitness centre that has a pool, volleyball courts, group training rooms, etc. The fitness centre is located near a university, an upper secondary school, and other large businesses. The people who train at this gym are people that Crossley (Citation2006) would call engaged in ‘mundane, everyday forms of working out’ (24). The number of gym-goers at the gym has increased over the years. Between 1995 and 2015, the gym was rebuilt and expanded several times, including the regular addition of new equipment. At each expansion, more room was devoted to machines, treadmills, cycles, climbers, rowers, as well as weights (e.g. dumbbells). In addition, areas for functional movement training and CrossFit-style training have expanded over the years (this type of training did not exist in 1995). This expansion of the facility and number of gym-goers is reflected in the fact that in 2005 and 2015 only one day was needed to collect about the same amount of data that took two days to collect in 1995. Interestingly, the number of students at the nearby university and upper secondary school had increased significantly since the 1990s. The physical layout of the gym changed throughout the years, but it has always been divided into areas for cardiovascular machines, weight training machines, and free weights, and more recently areas for functional movement and CrossFit-style training have been added. In these areas, mirrors are mounted on the walls, an arrangement found in most gyms (Sassatelli Citation1999).

The people at the gym

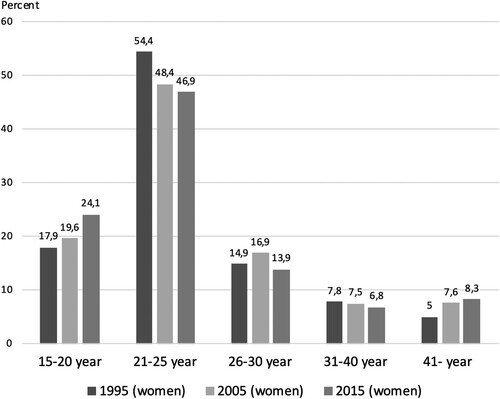

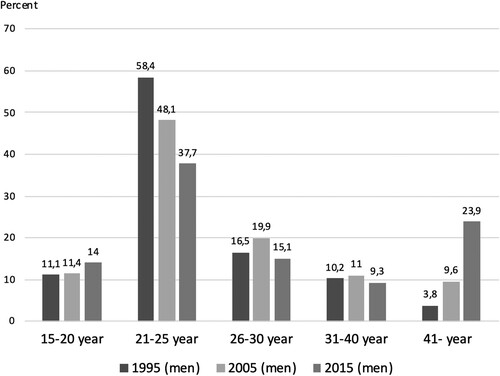

About two-thirds of the participants were men. However, the proportion of women increased from 28% in 1995–34% in 2015, reflecting an increase of women training with weights since the 1990s (). Although the age range with the largest group of both female and male participants was 21–25 years old, most likely because many university students train at the gym, the gym-goers represent an age range from adolescence to retirement age. However, between 1995 and 2015, female participants trended younger and male participants trended older ( and ).

and show that women training at the gym under the age of 20 had increased from 17.9% in 1995–24.1% in 2015, and the proportion of men 41 years and older had increased from 3.8% in 1995–23.9% in 2015. Although women under the age of 20 had increased, the average age for women was about the same for all years: 25.2 (SD 7.7) in 1995; 26 (SD 9.1) in 2005; and 25.3 (SD 9.6) in 2015 (1995–2005, t(502) = −1.027, P > 0.01; 2005–2015, t(650) = 0.801, P > 0.01). illustrates that the average age for men had increased: 25.2 (SD 6.3) in 1995; 27.4 (SD 9.7) in 2005; and 27.8 (SD 10.9) in 2015. There were significant age differences between 1995 and 2005 (t(1117) = −4.604, P < 0.01) but not between 2005 and 2015 (t(1296) = −0.689, P > 0.01). This average age is lower than what McCabe and James (Citation2009) found but similar to what Zach and Adiv (Citation2016) found.

Moreover, the results show that more than 80% of both women and men training at the gym in 1995, 2005, and 2015 had a background in organized sports in childhood and adolescence (women 83–90%; men 88–92%). The results also show that the gym-goers regularly engaged in other training activities and that a higher proportion of the men compared to women trained only at the gym ().

Table 2. Gym training only (%).

shows that about 20% of the male gym-goers only trained at the gym, except for in 2015, when 38.4% of the men stated that they only exercised at the gym, a large change compared to previous decades.

Training patterns at the gym

The results show that the number of years people had trained at the gym increased over the years. For the women, the average number of years they had been training at the gym significantly increased from 3.1 (SD 1.9) in 1995–4.5 (SD 2.2) in 2015 (t(552) = −7.087, P < 0.01). Similarly, the number of years men had been trained at the gym significantly increased from 3.8 (SD 2.1) in 1995–4.8 (SD 2.5) in 2015 (t(1206) = −6.878, P < 0.01). The results show further that men on average trained more hours each week than the women ().

Table 3. Number of average hours training at the gym each week (Mean value).

The training hours each week are rather similar for the men over the years, whereas the training hours varied more for women (). The results also show that at all three data collection points nearly 70% of the men preferred training with weights; however, the proportion of women who preferred training with weights increased: in 1995, 22% preferred training with weights; in 2005, 38% preferred training with weights; and in 2015, 65% preferred training with weights. This shift of preference from machines to free weights means that a majority of the women in 2015 used the same equipment as the men, which was not the case 20 years earlier. In addition, the questionnaires show further that what participants prioritize in their gym training (ranked in 1995) or train to a high degree (option 4–5 on the Likert scale) varied between 1995 and 2015.

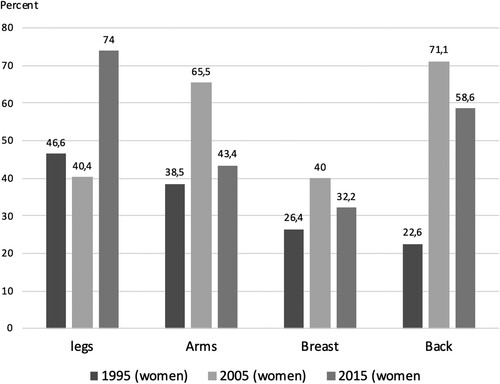

What muscles women trained changed (). Legs were prioritized in 1995 and 2015 but were not as important in 2005. In 2015, women prioritized training their legs and backs, but in 2005 women prioritized training their arms and back. This preference for training legs in 2015 is in line with what other studies have found (e.g. Markula Citation1995; Zach and Adiv Citation2016), although the importance for training the back has not been noticed in other studies.

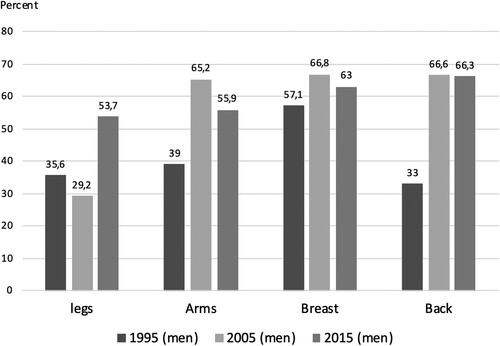

The muscles men prioritize have also shifted over the years. In 1995, men prioritized training their chest, whereas in 2005 they prioritized training the arms and back as well as the chest (). In 2015, men exercised different muscles rather equally. The 1995 prioritization is similar to Zach and Adiv’s study from 2016 but the gym-goers’ prioritization in 2015 in this study is quite different.

Motives for training at the gym 1995–2015

Between 1995 and 2015, the analysis of the ten motives shows both that some motives consolidated their position as high priority as well as that the importance of some of the motives changed (). provides mean values for each motive as well as the test statistics.

Table 4. Motives for training at the gym 1995–2015 (Mean value, scale 1–5).

As shown in , some motives had consistently high and low importance, but the importance of some motives changed significantly between 1995 and 2015.

High importance motives

For all years, both the men and women judged motives 1–3 to be important. Both men and women marked the motive ‘to improve strength’ as a consistently strong motive for all years, although a significant difference is noted between the years (highest in 1995). However, women valued the motive as more important in 2005 (t(884) = −4.79, P < 0.01) and 2015 (t(1038) = −4.04, P < 0.01). For all years, both men and women valued the motive ‘because it is healthy’ high, but women judged the motive as more important than men: 1995 (t(715) = 5.14, P < 0.01); 2005 (t(883) = −6.66, P < 0.01); and 2015 (t(1042) = −6.97, P < 0.01). The analysis of the motive ‘to be fit’ (well-trained) shows that there is a significant difference between years, but there was no significant difference between men and women. Although the motive is valued a bit less important in 2005 and 2015, the importance of the motive is consistently strong for both men and women over the years.

Low importance motives

As with the strong motives, some motives are consistently low for training at a gym. For example, ‘because it is indoors’ (9) and ‘to meet others’ (10) are less important for training at the gym (). The motive ‘because it is indoors’ has significantly decreased between 1995 and 2015, and the t-test shows no significant difference between men and women. Both males and females value the motive ‘to meet others’ low for all the years and the t-test shows no significant difference between men and women.

Motives that greatly changed in importance

Five of the motives, 4 through 8, changed in importance between 1995 and 2015 (). In 1995, the motive ‘to build muscles’ was of high importance, but between 1995 and 2015 both women and men equally decreased (not a statistical difference, however) the importance of the motive ‘to build muscles’. The motive ‘because it is fun’ became more important over the years and women judged the motive as more important than men in 1995 (t(713) = −3.461, P < 0.01) and in 2015 (t(1038) = −5.256, P < 0.01). The motive ‘to get firmer shapes’ has decreased in importance over the years but was still a rather important motive for women. Women judged the motive ‘to get firmer shapes’ as more important than men for all years: 1995 (t(706) = −9.298, P < 0.01); 2005 (t(874) = −9.315, P < 0.01); and 2015 (t(1037) = −10.531, P < 0.01). For both men and women, the motive ‘to improve endurance’ increased over the years. However, women valued the motive more important in 1995 (t(713) = −3.461, P < 0.01) and 2015 (t(1034) = −8.921, P < 0.01). Finally, the motive ‘to look attractive’ has greatly changed in importance for training at the gym. This motive increased in importance, especially for women, between 1995 and 2005. Men valued the motive more important in 1995 (t(706) = 5.326, P < 0.01), whereas both men and women judged the motive equally important in 2005 and 2015.

Overall, there has been a change in how motives are valued over the years. ‘It’s fun’ and ‘improving endurance’ have become highly important motives, especially for women, whereas ‘to build muscles’ and ‘to get firmer shapes’ has decreased in importance for both men and women. The motive ‘to get firmer shapes’ has increased in importance over the years, although it was not a top valued motive in 2015. In 2015, women valued strength, health, fun, firmer shapes, and endurance as more important than men valued these motives, but men and women valued the other motives equally.

Discussion

The 20-year perspective of Swedish gym-goers show that some motives were rather constant over the years, but that there were changes in both training patterns and motives, which are discussed below.

Gym-goers training patterns 1995–2015

In general, the data show that the number of people training at the gym increased during the 20-year period. Women who trained in the gym increased from 28% in 1995–34% in 2015. Overall, both men and women who trained in the gym were relatively young, and the number of women under the age of 20 had increased in 2015. The increase in young women training regularly at the gym might be attributed to the fact that the interest in training increases during later adolescence (Craike, Symons, and Zimmermann Citation2009) and that young girls are now introduced to gym training in secondary and upper secondary schools, making it easier for them to start training at a public gym. A majority of upper secondary schools in Sweden have their own gym equipment or cooperate with commercial gyms to provide weight training during school hours, which was not the case in the 1990s. Thomson and McAdoo (Citation2016) also point out that participating in sports in school may facilitate young people becoming regular exercisers. The increase of young girls at this gym could be the result of an increase in students at the nearby upper secondary school between 2005 and 2015. The results also show that men over 40 training at the gym increased in 2015. This finding could be because these men had been training for a longer time than the men who were training in 1995 and 2005. That is, in Crossley’s (Citation2006) terms, their gym training had become routine. Men also trained more hours each week in 2015 (5.1 h) compared to women (3.8 h), which reinforces the image of an almost daily routine.

The results show that the gym-goers train according to a weekly rhythm linked to weekly tasks. However, the equipment used in the weekly tasks differed between men and women. In 1995, 2005, and 2015, 70% of the men preferred training with weights; in 1995 and 2005, 78% and 62%, respectively, of the women preferred training with machines. In 2015, however, 65% of the women preferred training with weights, which is a large change from previous years. This shift in preference may be related to an increase of group class activities that use dumbbells and barbells (e.g. Body Pump and Grit). That is, the women who had experienced using weights in these group classes were comfortable training with weights by themselves in the gym. This experience together with more opportunities to train with free weights as well as weight machines, cycles, rowers, and gliders (i.e. training methods not available in the 1990s at the gym) may have contributed to the increase of women attending the gym. In addition, since the 1990s, CrossFit style training, a training approach that also uses weight training, has made its way into gyms, a trend that could explain some of the increase in the use of free weights rather than machines. This new training preference could also be the result of women having trained more years at the gym by 2015 compared to 1995 and therefore had the experience with all available training regimes at the gym. In Maguire and Mansfield’s (Citation1998, 135) terms, the way women control their bodies had changed. Overall, both the men and women who trained with weights also trained outside the gym, so their overall training load each week was relatively high. For both women and men, this training behaviour seems to have been shaped through participation in organized sports in childhood and adolescence. However, in 2015 nearly 40% of the men only trained at the gym. Further study is needed to determine whether these men compensated for not training with other activities by training more hours in the gym.

What the gym-goers in this study prioritize in their weekly tasks have changed over the years. Zach and Adiv’s (Citation2016) study shows that men to higher extent than women train the upper body, a finding partly corroborated in this study although between 1995 and 2015 there were changes. For example, women prioritized training their legs and back in 2015, but prioritized training their arms to a much higher extent in 1995 and 2005. For the women, training legs had always been a top priority over the years, which other studies also found, but the women in this study also gave high priority to training their arms in 1995 and 2005, results not found in other studies (e.g. Markula Citation1995; Zach and Adiv Citation2016). Men prioritized training all muscle groups more evenly in 2015, but they prioritized upper body training in 1995 and 2005. This change in priorities might be due to cultural changes about body ideals (cf. Choi Citation2003). Coen, Rosenberg, and Davidson (Citation2018) also suggest that masculine and feminine ideals of the body determine training practises. Today, for example, culture and society prioritizes legs and back for women and a well-trained symmetric muscular body (although not excessively large muscles) for men (e.g. as reflected in celebrities’ Instagram accounts). In addition, the influence of new training trends such as CrossFit might contribute to changes in training priorities. The change of prioritized muscles during the 20-year period indicates that masculine and feminine body ideals are always under negotiation and that the time needed for changing ideals is relatively short.

Gym-goers motives 1995–2015

Between 1995 and 2015, three of the ten motives remained stable. To become stronger, healthier, and more fit is of great significance for both men and women throughout the study period, although women placed a higher value on health and strength than men. These motives are also visible in most research on gym training (e.g. Crossley Citation2006; Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016; Dogan Citation2015; Lim et al. Citation2012; Zach and Adiv Citation2016). It is not a surprise that these motives are consistently strong for all years. Physical training at a gym contributes to becoming fitter (more well-trained) and healthier, and the very idea of strength training is to develop strength or at least maintain strength. The importance of five of the motives changed between 1995 and 2015. The motive ‘to build muscles’, which other studies have shown to be important for gym training (e.g. Damásio, Campos, and Gomes Citation2016; McCabe and James Citation2009; Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013), decreased between 1995 and 2015 for both men and women. In 2015, this motive was no longer one of the top motives for training in the gym. The decrease in the importance of building muscles may be understood in relation to society’s changing views of the ideal body type (i.e. a cultural shift) since the 1990s. That is, the body builder’s physique prioritized in the 1990s most likely has been replaced by a hard and toned body in 2015 for men (cf. Dogan Citation2015; Sassatelli Citation2016). However, this explanation does not fit with the decline trend for women. Markula (Citation1995) claim that as early 1995 that toned muscles were the primary aim for women training with aerobics (cf. Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998). Interestingly, women’s preference for using free weights in 2015 is not related to building muscles. It is likely, as already mentioned, that in 2015 women had learned to use dumbbells and barbells through group class activities (e.g. Body Pump and Grit) or CrossFit-style training for developing a hard and toned body, which was not the case in previous decades. Another aspect that relates to the decrease in the importance of building muscles in 2015 is that the number of years people trained at the gym increased over the years, which may have resulted in that many of the participants already had enough muscle gains by 2015. That is, the participants had achieved their desired ideal muscle mass, so they were training to maintain rather than to increase their muscle mass. Therefore, building muscles, which Crossley’s (Citation2006) study showed was important when starting training at a gym, is less important after one has trained for some time, because new motives for regular gym-goers ‘become available in the course of the gym career’ (Crossley Citation2006, 46; see also Pope and Harvey Citation2015). In addition, CrossFit-style training emphasizes functional and symmetric muscularity rather than building muscle mass, reflecting the men’s more evenly prioritization of muscle groups in 2015.

The motive ‘because it’s fun’ has increased in importance for both women and men between 1995 and 2015, although women valued the motive more than men. This change in value may be due to several reasons. First, the gym environment in 2015 was not the same as it was in 1995. In 2015, the investigated gym had many opportunities for training with weights, machines, functional movement training, and CrossFit-style training as well as with equipment such as cycles, rowers, and gliders, opportunities not available in 1995. By 2015, the gym could satisfy different training motives and provide a variety of training regimes that appealed to different motives. All of this possibly contributes to the exercise being perceived as more fun. From a psychological point of view, this fun or enjoyment factor is an intrinsic motive and the participants are autonomously motivated, which is associated with sustained engagement (e.g. Ingledew and Markland Citation2008). The motive ‘it’s fun’ may also be understood from a time perspective. Men and women had trained for a longer time by 2015 and their training seemingly had become a routine. The time participants spend at the gym may contribute to what Crossley (Citation2006) means when he claims they learn to enjoy their training. In addition, Maltby and Day (Citation2001) showed that students who had exercised for less than six months had less intrinsic motivation and psychological well-being than students who had exercised for six months or more (see Pope and Harvey Citation2015). Similarly, Box et al.’s (2019) study of high intensity functional training revealed that those who had trained for a longer time reported greater enjoyment than those who had trained for a shorter time (i.e. they were more motivated by body-related motives). It is easier to enjoy and continue training if the training also generates a sense of well-being or feel good factor (e.g. Crossley Citation2006; Dogan Citation2015; Neville and Gorman Citation2016).

For both genders, although especially for women, the motive ‘improving endurance’ increased between 1995 and 2015. In 2015, the women had replaced ‘building muscles’ with ‘improving endurance’ as one of the top motives. For men, ‘improving endurance’ had increased and is valued to a similar extent as ‘building muscles’ in 2015. This increase of the endurance motive may be related to the change of the gym environment, from a facility that focused on weight training to a facility that offered a variety of physical activities. That is, by 2015 the gym could satisfy more needs and desires than what was possible in 1995. However, it is unclear whether this change from a focus on muscle building to a focus on endurance is the result of customer needs or the result of the gym’s offering of alternative training forms. That is, the direction of causality is unclear.

Between 1995 and 2015, the motive ‘to get firmer shapes’ decreased in importance for both men and women. Although it is no longer one of the top valued motives, it is an important motive for women and valued much higher by women than men. This decrease of the motive ‘firmer shapes’ might be an effect of another view of muscularity (i.e. building muscles decreased in importance) but also that the gym-goers valued endurance training higher in 2015 than in 1995. Compared to other training forms at the gym, endurance training is less effective for ‘firmer shapes’. In addition, in similar ways as with the muscle motive, years of continuous training may have satisfied firmer shapes and therefore it was valued differently in 2015 than in 1995. Losing weight, which is a strong driving force for joining a gym (e.g. Caudwell and Keatley Citation2016; Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013) and related to ‘firmer shapes’, is satisfied, as Box et al. (Citation2019) conclude, with longer exercise involvement and therefore it is not a primary motive (see Pope and Harvey Citation2015).

The motive ‘to look attractive’, which previous studies have shown is an important motive for men (Lim et al. Citation2012; Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013) and women (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998; Urbonavicius, Janonyte, and Amirebayeva Reardon Citation2019), increased in importance for women to an equal level as for men between 1995 and 2015. That men and women value attractiveness equally important confirms Zach and Adiv’s (Citation2016) study but does not confirm Rojas’ (Citation2016) finding that men more than women emphasize physical appearance. However, although the mean values for 2015 suggest that the motive ‘to look attractive’ was important (3.47 men vs. 3.35 women), it was not as important as other motives, confirming findings from other studies (Crossley Citation2006; Dogan Citation2015; Neville and Gorman Citation2016). In that sense is, striving for a beautiful body Maguire and Mansfield (Citation1998) claim is essential for women who prefer aerobic training, a motive that is less important than other motives for the gym-goers in this study. However, the increased importance between 1995 and 2015 for the women to look attractive can also be interpreted as an increased desire to control the body according to social norms of femininity (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998, 135). The high value of being fit and the prioritization of muscle groups in their training regime in 2015 may reflect a stronger desire for women to obtain the ‘ideal’ culturally-valued body type: an ideal body that no longer is exclusively focused on the lower body as in Markula’s (Citation1995) study (see also Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998, Sankari 1995) but also includes the back. In this respect, the femininity to strive for in 2015 was different than in previous decades. In addition, the men’s more evenly training of all muscle groups may be due to, in Markula’s (Citation1995) terms, seeing all body parts as problematic, which was not the case in previous decades. Most likely, ‘to look attractive’ in its broadest sense is related to a cultural distaste for fat and motivates training at the gym (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998, 135; see also Markula Citation1995).

Finally, men and women did not train at the gym because they wanted to socialize or because it was an indoor activity. About 80% of the people training at the gym also participated in other exercise activities, and perhaps the motives related to the socializing that other studies found important (Burke, Carron, and Eys Citation2006; Crossley Citation2006; Lim et al. Citation2013) are satisfied through their other physical activities. Gym training is very flexible as gym-goers can choose the time and day to use the facilities. Therefore, the need for socializing may be a subordinate motive for gym training. However, as Cardone’s (Citation2019) study suggests, studies that do not capture gym-goers training routines might not discover the social dimension at the gym. In addition, training at the gym may be understood as an individual project since it corresponds to the needs and desires of its stakeholders (Braverman Citation1974, 82) and is oriented towards delivering a commodity among other commodities to people in the exercise market (Bauman Citation2001a, 135). Furthermore, other motives for gym training are of such great importance that people do not reflect over their meaning and what importance these motives (socializing or indoors) have for maintaining their training regime.

Some reflections on the gym culture from a 20-year perspective

Between 1995 and 2015, the gym expanded its membership as well as changed its equipment and machines. These changes reflect the influences of society as a whole. From a broader societal perspective, these changes were influenced by discourses that encourage physical activity and healthy lifestyles that, among other things, combat obesity. In Sweden, there are many initiatives for increasing physical activity. For example, employers encourage physical activity during working hours, including training in gyms, and the public health agency provides recommendations for aerobic and anaerobic activities (www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se). Recently, the government tasked a special investigator and national coordinator to increase knowledge about the positive effects of physical activity and to engage relevant actors (www.regeringen.se). This emphasis on lifestyle and physical activity may help explain the increase in gym-goers, which most likely affects training patterns and motives. Within this physical activity discourse, new functional training forms have emerged (e.g. CrossFit, Grit and Kettlebells), which have grown in popularity over the past 20 years. The gym, in Bauman’s (Citation2011) terms, ‘consists of offers [. . .] fashioned to fit individual freedom of choice and individual responsibility for that choice’ (12).

CrossFit-style training has moved into the gym, affecting both its physical design and the training at the gym. CrossFit-style training has experienced enormous growth over the past ten years (Sibley and Bergman Citation2018), a trend evident at the investigated gym as more space was devoted to CrossFit-style and functional movement training between 2005 and 2015. The changes in the motive ‘strength’ include not only women preferring weights over machines but also men’s prioritization of muscle groups may be a reflection of the new training forms. The prioritization of strength and endurance relates to physique enhancement, which crossFit-style training, according to Sibley and Bergman (Citation2018), improves. In addition, being fit and well-trained, which is a top valued motive, might be linked to the expansion of CrossFit-style training in the gym, as this type of training contains high volume workouts engaging multi-joint movements (Sibley and Bergman Citation2018, 556).

The change in motives and training preferences between 1995 and 2015 shown in this study adds new knowledge about the intersection of gyms and gender, raising some questions about both masculinity and femininity as well as the gym as a gendered space. Why did women’s preferences for weights change between 1995 and 2015? Is this change in preference a sign of the decline of masculinity in the gym? What does this change mean for the gender order? Free weights are usually placed in the front area of a gym. For men, this placement means they can more easily demonstrate their strength and muscles in front of others. Between 1995 and 2005, women preferred machines, but by 2015 65% of the women stated that they preferred free weights. In Goffman’s (Citation2015) terms, these women had started to move from the back region of the gym (where the machines are usually placed) to the front region of the gym, in front of the mirrors where barbells and weights are lined up, competing for space in a traditional male domain. This study also shows that more men prioritized endurance in 2015; that is, there were more men in the back region of the gym, the traditional domain for women. Endurance has always been a more important motive for women. Coen, Rosenberg, and Davidson (Citation2018) found that only a few women and men ventured into the other’s gendered domains, but this study suggests movement between gendered domains may be much more extensive. What does this change mean in terms of challenging the traditional gender-based expectations (Fisher, Berbary, and Misener Citation2018) and territorial-gendered spaces (Clark Citation2017, 9)? These questions need further study. Moreover, how has the decreased interest in building muscle mass affected the traditional ideal of masculinity (Johansson Citation1998; Klein Citation1993)? Such findings suggests that the body ideals of men and women are becoming more similar. The changes in the strength of the motives (i.e. in the prioritization of muscles) also make it possible to ask whether it indicate more than the surface they represent – i.e. profound changes in the gender order. All of these changes at the gym and the gym-goers’ training and motives for training over time make it possible to ask whether this is a sign of defying the dominant patriarchy (cf. Markula’s Citation1995 discussion of male and female body ideals; Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998). However, it could be, in Maguire and Mansfield’s terms (1998, 128), a reflection of consumer cultural ‘legitimat[ing] ideas of appearance’ in contemporary society. Legitimated ideas which, in Bauman’s (Citation2007) terms, not keep their shape for long, as shown by the change in prioritized muscles over a 20-year period.

Nonetheless, it is possible to conclude that the claim of the 1990s that women train to firm their buttocks and thighs and men train to increase the muscularity of their shoulders and chest were no longer valid by 2015 (Markula Citation1995; Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998). The ideals of ‘the body beautiful’ – how and what to control according to social norms concerning femininity (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998) as well as the ideal muscular masculine body (e.g. McCabe and James Citation2009; Stewart, Smith, and Moroney Citation2013) – are undergoing change. What kind of masculinity and femininity gym-goers strive for is, as we have seen, always negotiated and embedded in a gym that has become more multidimensional each decade (cf. Andreasson and Johansson Citation2014). However, a discussion about both the meaning making surrounding training patterns and motives as well as gender in relation to gym habits is problematic and difficult to catch in this study. Additional empirical in-depth data from, for example, interviews are needed to unravel the underlying meanings and observations of what is going on and to sort out such questions.

Concluding remarks

By comparing men and women and their training patterns and motives over a 20-year period, although repeated and cross-sectional for both training patterns and motives, has made it possible to capture blind spots in research that have not been reported previously. The study sheds light on how gym culture has changed and how training can be understood, at least in the gym examined in this study. It has provided an analysis of how to understand the relationship between the growth of gym training, training patterns, and motives for training in relationship to consumer cultural values. What people do at the gym and why a particular form of physical capital such as stronger, fitter, and healthier bodies remained fundamental, but other dimensions have increased or decreased over time relates to an individual freedom embedded in and shaped by a changing gym culture and broader circulating discourses of health, fitness, and lifestyle.

Although investigating only one gym could be seen as a limitation, the gym in focus has always been located at the same place and recruited about the same type of people (students from the nearby campus, those who work nearby, and other regular exercisers) since the facility houses more activities than just strength training. The gym has expanded its facilities to accommodate more people rather than opening new gyms in other parts of town. Therefore, the results are not due to new groups of people who might have different preferences. The expansion of the facility is also due to the fact that the university has grown during this period and that more companies have established themselves in the immediate area, resulting in an increased membership. The fact that there are more young people who are training in 2015 may be due to the fact that an upper secondary school has established itself in the local area. Therefore, the changes in this gym seem to represent changes in gym culture. In addition, the widespread weight training culture, which Andreasson and Johansson (Citation2014) claim is an international enterprise (cf. Sassatelli Citation2016), makes it plausible that these results can be transferred to other gyms in other settings, including other countries. However, more studies of other gyms in different countries are needed before we can know if the results presented apply beyond this study.

There are limitations regarding the motives used in this study. Only ten motives were overlapping in all three questionnaires, so this study definitely missed motives related to gym training. For example, the questionnaires do not include what previous research acknowledges regarding how enjoyable routines generate well-being and relaxation (e.g. Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998; Neville and Gorman Citation2016). Including more motives would have captured a wider range of reasons for training and therefore would have provided a more nuanced analysis. Moreover, the analysis of the changes that have taken place can be further developed e.g. how motives, priorities, and training regimes vary between ages, how long-term regular training affects gym-goers’ motives, and what gym training means in relation to other training. In addition, the decrease in the muscle motive may also be due to the way the motive question was asked (‘to build muscles’) as this might not capture how people understand the meaning of building muscles, and men’s and women’s views on what building muscle means probably also differ. There is also a chance that the muscle motive was interpreted differently in 1995 than in 2015 as a consequence of changes in society regarding body image and exercise. Therefore, there are uncertainties in how well the question captures the meaning of muscle training in 2015.

Overall, the training patterns and motives during the 20-year period show that the habitual practice (regularity and stability) to control the body, in Sassatelli’s (Citation2016) terms, has not changed. It is still a weekly training regime. However, what Sassatelli (Citation2016, 243) calls ‘projects of well-being’ have changed. In consumer culture, it is every gym-goers responsibility, in a postmodern sense, to find her own path to successful health, which, as the growth of gym tells us, makes the gym market lively (see Bauman Citation1991 for an elaboration of the postmodern conditions). The expectation for individuals to focus on shaping their body (Maguire and Mansfield Citation1998) is still present, but how it should be shaped and the goal of the shaping has changed. In this respect, the changes reflect consumer cultural values of which the youthful, firm, and well-trained body is particularly indicative of the training conducted (e.g. Wright, O’Flynn, and Macdonald Citation2006; Featherstone Citation2010) in a different light. The analysis shows that both exercise regimes with respect to prioritization of muscle groups and motives have changed. Cardiovascular training, although it can lead to weight reduction, has become more important, whereas more visible body shaping motives such as building muscles and shaping firmer bodies have decreased in importance. On the other hand, regardless of the changes in training patterns and motives, training results in a more firm and well-trained body, especially since the gym-goers’ weekly training load is high. Therefore, it is possible to claim that a consumer cultural understanding – i.e. a body to invest in and an individual responsibility for bodily health – is always valid (e.g. Featherstone Citation2010; Fisher, Berbary, and Misener Citation2018).

Finally, the results suggest that new gym-goers will join the gym culture and current gym-goers will continue training at the gym. The increase in the number of people training at the gym suggests a positive association to the gym community because, in Bauman’s terms, the gym has promising pleasures (Bauman Citation2001b). In a way, the attractiveness of the gym culture depends on people being attracted to the promise that their training will help them develop a healthier and better functioning body, which also inevitably reflects the cultural norms of bodily firmness and hardness. However, each refinement of the body or health is temporary, as aging ultimately ravages a physique, health, and well-being (cf. Bauman Citation1991). Therefore, irrespective of health discourses, training trends, or body ideals, the gym will continue to address the needs of gym-goers, male and female, although these needs will mostly certainly change.

Acknowledgments

The author wants to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tor Söderström

Dr. Tor Söderström is a professor in the Department of Education, Umeå University, Sweden. His research interest is within various sport related areas.

References

- Andreasson, J., and T. Johansson. 2014. “The Fitness Revolution. Historical Transformations in the Global gym and Fitness Culture.” Sport Science Review XXIII (3–4): 91–112.

- Bauman, Z. 1991. Modernity and Ambivalence. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bauman, Z. 2001a. The Individualized Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bauman, Z. 2001b. Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bauman, Z. 2007. Liquid Times. Living in an age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bauman, Z. 2011. Culture in a Liquid Modern World. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bladh, G. 2020. Moving thresholds. Body narratives within the vicinity of gym and fitness culture” PhD diss., Umea university.

- Blair, S. N. 1996. “The Future of Sports Medicine.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 30 (1): 2–3.

- Box, A. G., Y. Frito, C. Brown, K. M. Heimrich, and S. J. Petruzello. 2019. “High Intensity Functional Training (HIFT) and Competitions. How Motives Differ by Length of Participation.” PlosOne 14 (3): e0213812.

- Braverman, H. 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital. The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Burke, S. M., A. V. Carron, and M. A. Eys. 2006. “Physical Activity Context: Preferences of University Students.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 7 (1): 1–13.

- Cardone, P. 2019. “The gym as Intercultural Meeting Point? Binding Effects and Boundaries in gym Interaction.” European Journal for Sport and Society 16 (2): 111–127.

- Caudwell, K. M., and D. A. Keatley. 2016. “The Effect of Men’s Body Attitudes and Motivation for gym Attendance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 30 (9): 2550–2556.

- Choi, P. Y. L. 2003. “Muscle Matters: Maintaining Visible Differences Between Women and men.” Sexualities, Evolution & Gender 5 (2): 71–81.

- Clark, A. 2017. “Exploring Women’s Embodied Experience of the ‘Gaze’ in a mix-Gendered UK gym.” Societies 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/soc801002

- Coen, S. E., J. Davidson, and M. W. Rosenberg. 2021. “‘Where is the Space for Continuum?’ Gyms and the Visceral “Stickiness“ of Binary Gender.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13: : 537–553. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2020.1748897.

- Coen, S. E., M. W. Rosenberg, and J. Davidson. 2018. ““It's gym, Like g-y-m not J-i-m”: Exploring the Role of Place in the Gendering of Physical Activity.” Social Science & Medicine 196: 29–36.

- Craike, M. J., C. Symons, and J. M. Zimmermann. 2009. “Why do Young Women Drop out of Sport and Physical Activity? A Social Ecological Approach.” Annals of Leisure Research 12 (2): 148–172.

- Crossley, N. 2006. “In the gym: Motives, Meaning and Moral Careers.” Body & Society 12 (3): 23–50.

- Damásio, A., F. Campos, and R. Gomes. 2016. “Importance Given to the Reasons for Sport Participation and to the Characteristics if a Fitness Service.” ARENA – Journal of Physical Activities 5: 46–56.

- Dogan, C. 2015. “Training at the gym, Training for Life: Creating Better Versions of the Self Through Exercise.” Europe’s Journal of Psychology 11 (3): 442–458.

- Engström, L.-M., B. Ekblom, A. Forsberg, M. Koch, and J. Seger. 1993. Livstil - Prestation - Hälsa. Stockholm: Folksam.

- Featherstone, M. 2010. “Body Image and Affect in Consumer Culture.” Body & Society 16 (1): 193–221.

- Fisher, M. J. R., L. A. Berbary, and K. E. Misener. 2018. “Narratives of Negotiation and Transformation: Women’s Experiences Within a Mixed-Gendered gym.” Leisure Sciences 40 (6): 477–493.

- Green, K., M. Thurston, and O. Vaage. 2015. “Isn’t it Good, Norwegian Wood? Lifestyle and Adventure Sports Participation among Norwegian Youth.” Leisure Studies 34 (5): 529–546.

- Goffman, E. 2015. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

- Halliwell, E., H. Dittmar, and A. Orsborn. 2007. “The Effects of Exposure to Muscular Male Models among men: Exploring the Moderating Role of gym use and Exercise Motivation.” Body Image 4 (3): 278–287.

- Horton, K., T. Ferrero-Regis, and A. Payne. 2016. “The Hard Work of Leisure: Healthy Life, Activewear and Lorna Jane.” Annals of Leisure Research 19 (2): 180–193.

- Ingledew, D. K., and D. Markland. 2008. “The Role of Motives in Exercise Participation†.” Psychology & Health 23 (7): 807–828.

- Johansson, T. 1996. “Gendered Spaces: The gym Culture and the Construction of Gender.” Young 4 (3): 32–47.

- Johansson, T. 1998. Den skulpterade kroppen. Stockholm: Carlssons.

- Klein, A. M. 1993. Little Big Men. Bodybuilding Subculture and Gender Construction. New York: State University of New York Press.

- Lim, W. M., D. Hooi Ting, A. M. Shandy, S. K. Ann Cheach, N. Net-Ti Ooi, and N. Hana Azlan. 2012. “The State of Mind of Contemporary Male gym-Goers: Goals, Inspirations and Motivations.” International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 11 (3/4): 239–256.

- Lim, W. M., D. Hooi Ting, K. Ying-Ying Loh, W. Teng Loh, and S. Shaikh. 2013. “Men’s Motivation to go to the Gymnasium: A Study of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation.” Journal of Sport Management and Marketing 13 (1/2): 122–139.

- Loze, G. L., and D. J. Collins. 1998. “Muscular Development Motives for Exercise Participation: The Missing Variable in Current Questionnaire Analysis?” Journal of Sports Sciences 16 (8): 761–767.

- Maguire, J., and L. Mansfield. 1998. ““No-Body’s Perfect”: Women, Aerobics, and the Body Beautiful.” Sociology of Sport Journal 15 (2): 109–137.

- Maltby, L., and L. Day. 2001. “The Relationship Between Exercise Motives and Psychological Weil-Being.” The Journal of Psychology 135 (6): 651–660.

- Markula, P. 1995. “Firm but Shapely, fit but Sexy, Strong but Thin: The Postmodern Aerobicizing Female Bodies.” Sociology of Sport Journal 12 (4): 424–453.

- McCabe, M. P., and T. James. 2009. “Strategies to Change Body Shape among men and Women who Attend Fitness Centers.” Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 21 (3): 268–278.

- Neville, R. D., and C. Gorman. 2016. “Getting ‘in’ and ‘out of Alignment’: Some Insights Into the Cultural Imagery of Fitness from the Perspective of Experienced gym Adherents.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 8 (2): 147–164.

- Pope, L., and J. Harvey. 2015. “The Impact of Incentives on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motives for Fitness-Center Attendance in College First-Year Students.” American Journal of Health Promotion 29 (3): 192–199.

- Rojas, A. S. 2016. “I’m Super-Setting my Life! An Ethnographic Comparative Analysis of the Growth of the gym Market.” Sport Science Review XXV (5–6): 321–344.

- Sassatelli, R. 1999. “Interaction Order and Beyond: A Field Analysis of Body Culture Within Fitness Gyms.” Body & Society 5 (2–3): 227–248.

- Sassatelli, R. 2016. “‘You Can all Succeed!’: The Reconciliatory Logic of Therapeutic Active Leisure*.” European Journal for Sport and Society 13 (3): 230–245.

- Sibley, B. A., and S. M. Bergman. 2018. “What Keeps Athletes in the gym? Goals, Psychological Needs, and Motivation of CrossFit™ Participants.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 16 (5): 555–574.

- Söderström, T. 1999. Gymkulturens logik. Om samverkan mellan kropp, gym och samhälle” PhD diss., Umeå universitet, pedagogiska institutionen.

- Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden). 2020. Statistikdatabasen, näringsverksamhet. www.scb.se. Retrieved 20201230.

- Stewart, B., A. Smith, and B. Moroney. 2013. “Capital Building Through gym Work.” Leisure Studies 32 (5): 542–560.

- Storm, R. K., and O. R. Hansen. 2021. “Commercial Fitness Centres in Denmark: A Study on Development, Determinants of Provision and Substitution Effects.” Annals of Leisure Research, doi:10.1080/11745398.2019.1692684.

- The Swedish Sport Confederateiodn (Riksidrottsförbundet). 2003. Svenska folkets tävlings- och motionsvanor. www.rf.se.

- The Swedish Sport Confederation (Riksidrottsförbundet). 2011. Svenska folkets idrotts- och motionsvanor. www.rf.se.

- Thomson, D., and K. McAdoo. 2016. “An Exploration Into the Development of Motivation to Exercise in a Group of Male UK Regular gym Users.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14 (4): 414–429.

- Turner, B. S. 1996. The Body & Society. London: Sage Publications.

- Urbonavicius, S., A. Janonyte, and S. Amirebayeva Reardon. 2019. “The Influence of Body Objectification and Health Locus Control on Using gym Services by Women.” Journal of Business, Marketing and Decision 12 (1): 13–30.

- World Health Organization. 2012. Governance for Health in the 21st Century.

- Wright, J., G. O’Flynn, and D. Macdonald. 2006. “Being Fit and Looking Healthy: Young Women’s and Men’s Constructions of Health and Fitness.” Sex Roles 54 (9–10): 707–716.

- Zach, S., and T. Adiv. 2016. “Strength Training in Males and Females – Motives, Training Habits, Knowledge, and Stereotypic Perceptions.” Sex Roles 74 (7–8): 323–334.