ABSTRACT

Although access to leisure is a right for all, people with disabilities (PwD) face great constraints in exercising this right. Using a qualitative approach, this study examines the view of a group of Portuguese social organizations (PSO) that support PwD concerning the needs, motivations and constraints that they face when participating in tourism activities, as well as the benefits obtained through the participation in these activities. The results highlight that PwD are strongly motivated to participate in tourism activities, but they face a great number of constraints (intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural). Moreover, according to the view of PSO, PwD feel the benefits obtained from their participation in tourism activities intensely, which contributes to enhancing their well-being. The paper ends with strategies that should be implemented in tourism destinations to overcome the travel constraints faced by PwD to increase their participation in tourism activities.

Introduction

Although participation in leisure activities is considered a human right (Evans, Bellon, and Matthews Citation2017; Singleton and Darcy Citation2013), there are a great number of people for whom participation in these activities is just a dream that has not come true. However, the literature highlights the importance of leisure, which encompasses a large part of the tourism activities, to the well-being of those who undertake such activities, independently of their conditions or functional limitations (Gillovic and Mcintosh Citation2020; Richards, Pritchard, and Morgan Citation2010; Sedgley et al. Citation2017). Nevertheless, people with disabilities (PwD) tend to feel the benefits of leisure and tourism activities with greater intensity when compared to people without disabilities (Kastenholz, Eusébio, and Figueiredo Citation2015; Moura, Kastenholz, and Pereira Citation2018; Patterson and Pegg Citation2009). Specifically, these activities can be a tool to overcome the pressure brought about by disability, contributing directly to improving physical and mental health and social relations (Bergier, Bergier, and Kubińska Citation2010; McCabe Citation2009; Moura, Kastenholz, and Pereira Citation2018; Patterson and Balderas Citation2020; Patterson and Pegg Citation2009). Moreover, participation in leisure activities, including tourism activities, has a positive impact on individual self-esteem and well-being (Bergier, Bergier, and Kubińska Citation2010; McCabe Citation2009; Moura, Kastenholz, and Pereira Citation2018; Patterson and Balderas Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2017), preventing isolation and increasing social interactions (Patterson and Pegg Citation2009).

Despite the considerable benefits that PwD can obtain through participation in leisure and tourism activities, several studies (e.g. Alves et al. Citation2020; Innes, Page, and Cutler Citation2015; Thomas Citation2018) show that a great number of PwD are excluded from these activities due to internal (intrapersonal) and external (interpersonal and structural) constraints. This exclusion is even more intense in the case of institutionalized PwD (in the care of a formal caregiver) (Gillovic Citation2019; Melbøe and Ytterhus Citation2017).

PwD is a growing market with relevant economic contributions to the tourism industry (Benjamin, Bottone, and Lee Citation2021; Kong and Loi Citation2017; Darcy, McKercher, and Schweinsberg Citation2020). Although one million people, about 15% of the world's population, currently have some type of disability (WHO Citation2020), this number is likely to increase in the future, as a result of population aging, increase in chronic diseases and improvements in the measurement of disability. Moreover, PwD desire and are motivated to carry out leisure and tourism activities (Alves et al. Citation2020; Bauer Citation2018; Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011). Therefore, the great challenge of tourism supply agents (TSA) is to make tourism experiences accessible for all, not only as a social responsibility, but also because it is an excellent business opportunity (Patterson and Balderas Citation2020). However, PwD are a heterogenous market with different needs, motivations and travel constraints. This heterogeneity depends on the type (i.e. physical, hearing, visual or intellectual) and level of disability (Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011; Burns, Paterson, and Watson Citation2009; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012).

PwD may live their lives independently (with or without a personal assistant) or with a support of a caregiver (formal or informal). A great number of PwD depend on a formal caregiver to obtain the support they need to engage in various dimensions of their lives, such as daily tasks and even specific leisure and tourism activities (Abraham et al. Citation2002; Ager et al. Citation2001; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009). Therefore, it is of utmost relevance to examine the view of these formal caregivers concerning the needs, motivations, constraints and benefits that PwD obtain from participating in tourism activities. In some countries, such as Portugal, social organizations (SO) (e.g. non-governmental organisations, associations, charities, foundations and cooperatives) that help PwD in various domains of their lives, including participation in leisure and tourism activities, have a crucial role in the tourism experiences of this market (Carneiro et al. Citation2022). However, the literature in this field is very scarce and the majority of the studies published examine only the views of PwD concerning these issues. However, a great number of PwD depend on a formal caregiver, such as a social organization, to participate in leisure and tourism activities. Without the intervention of these organizations, many of these people would never have had the opportunity to engage in leisure and tourism experiences (Abraham et al. Citation2002; Carneiro et al. Citation2022; Gillovic Citation2019; Hansen et al. Citation2021; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009). As Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen (Citation2011) highlight, there is a research gap concerning the intervention of formal caregivers, specifically caregiving organizations, in the access of PwD to leisure and tourism activities.

To overcome the aforementioned gaps, the intention of this paper is: (i) to examine the view of Portuguese caregiving organizations that provide support to PwD (formal caregivers) regarding the needs, motivations, constraints and benefits of their members (PwD) participating in tourism activities; and (ii) to propose strategies, based on the view and experiences of caregiving organizations, to overcome the travel constraints of PwD.

This paper has four important contributions. First, it provides relevant insights to increase theoretical knowledge in an area that has been neglected in the leisure and tourism literature. Second, it provides relevant information to TSA on how to develop accessible tourism products. Thirdly, it provides relevant contributions to increase the involvement of SO that provide support to PwD (caregiving organizations) on the supply of leisure and tourism activities. Finally, the aim of this article is also to sensitize all TSA, SO providing support to PwD, politicians and all citizens about the importance of leisure and tourism activities for the well-being of PwD. The involvement of all will contribute to the development of a more inclusive society.

Literature review

Needs of PwD to engage in tourism activities

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) recognizes “the importance of accessibility to the physical, social, economic and cultural environment, to health and education and to information and communication, in enabling PwD to fully enjoy all human rights and fundamental freedoms” (UN Citation2006, 3). However, this segment of society faces great constraints to enjoying all human rights, including participation in leisure activities, with tourism being a subset of these activities, as a result of an intersection between bodily functions (mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive) and characteristics of the physical and social environments (Froehlich-Grobe et al. Citation2021; Oliver Citation1990a).

Disability is a multidimensional, complex and dynamic concept (WHO Citation2011) that has mainly been studied in the past 30 years with a medical and a social approach (Evans, Bellon, and Matthews Citation2017). According to the medical model, the disability is viewed as a deficit from the normal that needs treatment to overcome it (Singleton and Darcy Citation2013). There is, therefore, a form of biological determinism, because it focuses on the physical or intellectual difference between individuals, ignoring the social and economic context where they live. According to Shakespeare (Citation1996), this model is based on the idea of the existence of a standard of normality, from which PwD (physical or intellectual) deviate precisely because they have a medical diagnosis which classifies them as PwD. On the other hand, the social model “recognizes the importance of placing disability on the social, political, economic and cultural agendas” (Singleton and Darcy Citation2013, 186) and focuses on removing barriers to full participation by people with physical or intellectual limitations in all life dimensions. In this line of thought, understanding the disability from a social model perspective is of utmost relevance in providing necessary services and support to remove these barriers. Thus, according to the social model, disability results from “a dynamic interaction between health conditions and contextual factors, both personal and environmental” (WHO Citation2011, 4), can be permanent or temporary and varies in degree (e.g. mild, moderate, and severe) (ICF Citation2002). The level of support needed varies according to the type and intensity of the disability. Moreover, the adequacy of environmental conditions, and attitudes towards PwD affect their participation in tourism activities (Buhalis and Michopoulou Citation2011; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009).

To increase the participation of PwD in tourism activities, several needs must be met. These needs may be categorized into two groups according to the stage of a tourism trip: (i) during the planning of a tourism trip; and (ii) during a trip. Concerning the first stage, PwD need correct, useful and up-to-date information concerning the accessibility level of spaces and tourism services (e.g. accessibility of outdoor areas, transports, accommodation, restaurants and tourism attractions), in addition to which, the information sources used should be accessible (Buhalis and Michopoulou Citation2011; Darcy, Cameron, and Pegg Citation2010; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012). During participation in tourism activities, PwD need: (i) tourism services and outdoor areas that accomplish the requirements of physical accessibility related to universal design; (ii) reliable information on accessibility; (iii) accessible communication (e.g. sign language); (iv) to feel safe (e.g. specific security plans must exist in the tourism supply to this market); and a (v) welcoming atmosphere (appropriate attitudes of residents, tourism professionals and other visitors) (Buhalis and Michopoulou Citation2011; Darcy 2010; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012). The majority of the literature published on needs of PwD to engage in tourism activities examines the perspective of PwD (e.g. Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011; Evans, Bellon, and Matthews Citation2017; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Melbøe and Ytterhus Citation2017; Ray and Ryder Citation2003; Richards, Pritchard, and Morgan Citation2010; Yau, McKercher, and Packer Citation2004) or of their informal caregivers, primarily family members (e.g. Cohen-Mansfield, Gavendo, and Blackburn Citation2019; Evans, Bellon, and Matthews Citation2017; Melbøe and Ytterhus Citation2017; Nyman, Westin, and Carson Citation2018; Gladwell and Bedini Citation2004; Sedgley et al. Citation2017). However, a great number of PwD in some countries participate in tourism activities organized by social organizations that provide support to PwD (caregiving organizations). A limited number of studies examine the view of formal caregivers concerning the needs and desires of PwD to participate in tourism activities (e.g. Cohen-Mansfield, Gavendo, and Blackburn Citation2019; Richards, Pritchard, and Morgan Citation2010). Therefore, it is of utmost relevance to examine the views of these organizations concerning the needs of PwD to engage in tourism activities.

Motivations of PwD to participate in tourism activities

The daily-life of PwD and their needs in terms of recreation and tourism activities are highly influenced by their characteristics and motivations (Buhalis and Michopoulou Citation2011). Motivation is a key factor influencing tourism decision-making (Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011). The reasons for participating in recreation and tourism activities have been subject of reflection in different areas of academic knowledge, as an important indicator of how decisions, well-being and performance vary according to the individual motivations of the social actors (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). On this subject, the works of Crompton (Citation1979), Iso-Ahola (Citation1980) and Neulinger (Citation1981) stand out.

In Crompton’s (Citation1979) study, the subjects’ motivations are discussed according to push or pull factors to participation in tourism activities. According to this theoretical model, participation is based on the distinction between factors that encourage leaving the domestic environment (push factors); and others, which attract them to a new place (pull factors) (Adam, Kumi-Kyereme, and Adutwum Citation2017). Push factors are, therefore, intrinsic factors, which are related, for example, to the search for rest, relaxation, better health and well-being of the subjects. The pull factors are related to the attributes of a given destination, which are configured as attractive to the subjects to the point of leading them to visit it. They can include tangible resources, but also the perception and expectation of benefits, as well as the destination’s marketing image. Festivals and events, amusement and/or theme parks, the existence of easy and accessible access, among others, are examples of pull factors.

Iso-Ahola (Citation1980) presented a model in which motivations were seen in accordance with an “evasion/escape dichotomy”. In other words, this author points out that leisure, including tourism activities, assumes a logic of psychological reward in the lives of the subjects, when they are seen as means of escape from something that is less pleasant to them (Adam, Kumi-Kyereme, and Adutwum Citation2017). In turn, Neulinger (Citation1981) theorized the leisure paradigm, categorizing motivations into three types: intrinsic, extrinsic and the combination of the two previous forms. Intrinsic motivations are internal motivations, in which the desire to participate in a particular activity is related to the fact that this activity provides benefits, for example, for one’s psychological well-being. In turn, extrinsic motivations always involve external reasons for subjects to participate, such as obtaining monetary rewards related to participation in these activities. Finally, the combination of motivations of the two types happens when the subjects decide to participate in an activity, not only because it brings together a set of attributes that attracts them, but also because their participation brings benefits to them. This work was relevant in the study of the motivations of PwD to participate in tourism activities, and has been used by academics in different contexts (Allan Citation2015; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Ray and Ryder Citation2003; Shaw and Coles Citation2004; Yau, McKercher, and Packer Citation2004).

Although PwD have the same predisposition to participate in leisure and tourism activities as anyone else, previous studies reveal that their motivations to participate in these activities are more intense (Bauer Citation2018). Moreover, the published studies show the multiplicity of travel motivations of PwD, ranging from social motivations (e.g. meeting people of similar interests; being together as family) to personal motivations (e.g. being more physically active; learning about lifestyle) (Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Ray and Ryder Citation2003). The literature in this field has also shown that, in general, when PwD engage in tourism experiences they seek to challenge themselves (sometimes even desiring to take risks), to explore new things and have new experiences and to expand their knowledge (Shaw and Coles Citation2004; Yau, McKercher, and Packer Citation2004), but also to gain pleasure and personal satisfaction (Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012). Escape from everyday life and forgetting about personal problems are also benefits sought by PwD when engaging in tourism activities (Shi, Cole, and Chancellor Citation2012; Zhang et al. Citation2019). Frequently, this sense of escape, relaxation and enjoyment is felt by PwD and by their caregivers (Kim and Lehto Citation2013). Moreover, when PwD travel in family they search for family closeness and socialization (Kim and Lehto Citation2013). Therefore, PwD are usually motivated to participate in leisure activities, including tourism activities.

Although travel motivations are a frequently explored theme in studies related to disability and tourism, most studies analyse only the perspective of PwD (e.g. Adam, Kumi-Kyereme, and Adutwum Citation2017; Allan Citation2015; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Lyu, Oh, and Lee Citation2013; Shi, Cole, and Chancellor Citation2012). Studies that examine the view of caregivers (formal and informal) are very scarce (e.g. Kim and Lehto Citation2013), despite the relevance that these caregivers have as facilitators for a considerable number of people with special needs to participate in tourism activities.

Constraints for PwD participating in tourism activities

Although some studies (e.g. Bauer Citation2018; Benjamin, Bottone, and Lee Citation2021; Kim and Lehto Citation2013; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Zhang et al. Citation2019) show that PwD are strongly motivated to participate in tourism activities, their participation is often difficult due to the existence of travel constraints (Darcy, Cameron, and Pegg Citation2010). The formal caregivers, such as SO that provide support to PwD, may have a crucial role in identifying these constraints, as well as helping PwD to overcome them.

Crawford and Godbey (Citation1987) developed a model that allowed the identification of constraints on participation in leisure activities and categorized them into three types: intrapersonal, interpersonal and structural. According to the authors, these constraints affect not only individuals’ participation but also their preferences (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987). Intrapersonal constraints are individual factors, which may be related to the psychological state or to the physical/cognitive functions of the individual, and which affect their leisure preferences (e.g. lack of interest) (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008). On the other hand, interpersonal constraints (e.g. lack of a companion), related to individual’s interaction with others (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008), are social factors that affect the participation of PwD in leisure activities, as well as their preferences. Intrapersonal and interpersonal constraints vary during the lifetime of the subjects for multiple reasons, such as size of personal network (e.g. family, friends) and marital status (Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008). In turn, structural constraints (e.g. lack of money, lack of accessible products and information) correspond to environmental factors that inhibit PwD’s participation in leisure activities (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008). In 1991, Crawford, Jackson, and Godbey (Citation1991) modified the leisure constraints model proposed by Crawford and Godbey (Citation1987) transforming it into an integrated hierarchical model. According to this model, leisure constraints are encountered hierarchically. First and most powerfully, intrapersonal constraints are felt, which condition the motivation to participate. In the second stage, interpersonal constraints usually appear, especially when a companion is needed. If these leisure constraints are overcome, then the structural constraints begin to be encountered, strongly influencing participation (Crawford, Jackson, and Godbey Citation1991). After thirty years, this model is still up to date and is of great relevance to the study of leisure constraints (Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008). Moreover, this model has been a reference in studies analysing the constraints faced by PwD participating in leisure activities, including tourism activities (e.g. Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018).

The literature on leisure and travel constraints of PwD reveal that the intrapersonal constraints are related to age, health conditions, physical problems, lack of autonomy, dependence on others and discomfort and stress (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987; Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Gillovic Citation2019; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008; Zajadacz and Śniadek Citation2013). However, these constraints change over time (Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008).

The interpersonal constraints have a relational component and, in the case of PwD in the context of leisure and tourism activities, occur whenever interaction with people outside their social network or service providers results in barriers to their participation (Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008). The most common obstacles are communication barriers, socially negative attitudes, family context, influence of friends, and even the resistance to some norms, like assistance by guide dogs (Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Froehlich-Grobe et al. Citation2021; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008).

Finally, the structural constraints are external factors that hinder effective participation (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987). These constraints have an environmental origin and, according to the literature, may include lack of time, economic reasons, lack of opportunities, lack of accessible information (e.g. Braille, sign language, pictographic writing), lack of information about destination accessibility, destination characteristics (e.g. accessibility of restaurants, accommodation, museums and other attractions), or lack of specialized support services (Card, Cole, and Humphrey Citation2006; Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Gillovic Citation2019; Nyaupane and Andereck Citation2008).

As can be seen, constraints can limit the formation of preferences and/or inhibit participation and enjoyment of tourism activities, not only for the PwD (Jackson Citation2000), but also for the families (Freund et al. Citation2019). These constraints also prevent the supply of tourism activities for members of SO that support PwD (Carneiro et al. Citation2022). However, due the intersection between individual functions (mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive) and characteristics of the environment, the constraints do not influence all PwD in the same way (Lyu, Oh, and Lee Citation2013). For example, people with sensory disabilities (the blind, low sighted and deaf), frequently face strong constraints related to information and communication. Due the lack of visual support (e.g. sign language or visual alarms systems), deaf people have various difficulties accessing information and communicating with others during a leisure and tourism experience (Zajadacz and Śniadek Citation2013). For blind people and those with low vision, the absence of audio (e.g. audio guides) and tactile supports (e.g. Braille or high relief mock-ups) for access to information is still a huge barrier to their participation (Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Kong and Loi Citation2017; Small, Darcy, and Packer Citation2012). In addition, the non-compliance with rules and regulations (e.g. access to guide dogs) and the physical conditions of the environment can affect the mobility and safety of blind people and those with low vision, especially in unfamiliar environments (Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018; Small, Darcy, and Packer Citation2012).

In the case of people with intellectual disabilities, lack of accessible information and adapted communication (e.g. pictographic writing, simple language), lack of personal support in daily activities (e.g. personal assistance to help in travel and transports, schedules and routines), and negative attitudes towards disability (e.g. prejudice) are the most common barriers both according to the literature that examines the view of PwD and the view of their caregivers (Gillovic Citation2019; Gillovic and Mcintosh Citation2020; Kim and Lehto Citation2013).

For people with physical disabilities, structural constraints (e.g. lack of accessibility of buildings or public transports) are the factors which most inhibit participation in society, according to the literature (Card, Cole, and Humphrey Citation2006; Bauer Citation2018; Benjamin, Bottone, and Lee Citation2021). Physical disability affects people’s capacity to move around, which restricts accessibility to the environments and services, essential for participation in leisure and tourism activities (Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Ray and Ryder Citation2003).

Despite the numerous constraints on PwD participating in leisure activities, a vast number of PwD desire to do so, specifically in tourism activities, due to the numerous benefits they may obtain.

Benefits of participating in tourism activities for PwD

The literature on the perspective of PwD, as well as the literature on the perceptions of their caregivers (Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011; Bergier, Bergier, and Kubińska Citation2010; Wang et al. Citation2017; McCabe Citation2009; Patterson and Pegg Citation2009; Patterson and Balderas Citation2020; Sedgley et al. Citation2017), highlights the numerous benefits that PwD can obtain from participating in leisure activities.

The work of McCabe (Citation2009) evidenced that the participation of PwD in tourism activities contributes to their personal development and to improving their health and well-being. When the participation in tourism activities results in a positive experience, there is an increase in self-esteem and optimism, but also an improvement of physical and mental health (McCabe Citation2009; Patterson and Pegg Citation2009). Moreover, Bergier's research (Citation2010) highlights personal development, the satisfaction of overcoming barriers, the ability to adapt to unfamiliar environments and the acquisition of new knowledge. In turn, Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen (Citation2011) not only demonstrate the subjects’ health improvements, but also identify the opportunity to escape from habitual care environments and the feeling of having attention (care). Moreover, various studies (e.g. McCabe Citation2009; Darcy, Cameron, and Pegg Citation2010; Wang et al. Citation2017) emphasize the importance of participating in tourism activities for combating social isolation.

Some works that examine the view of caregivers, mainly informal caregivers (e.g. Innes, Page, and Cutler Citation2015; Kim and Lehto Citation2013; Sedgley et al. Citation2017) have gone beyond individual benefits and extended their analysis to families. In general, these studies have concluded that family participation in tourism activities are an opportunity for caregivers to relax and escape from routine and from the responsibilities of care and the possibility of socializing outside the family context, but also spending quality time with family, and carrying out activities to improve the competences of PwD (Freund et al. Citation2019; Innes, Page, and Cutler Citation2015; Kim and Lehto Citation2013; Morgan, Pritchard, and Sedgley Citation2015).

Despite the diverse benefits that PwD and their families may obtain from participating in leisure activities, in a considerable number of cases, access to these activities is only possible with the support of a caregiving organization (Carneiro et al. Citation2022). However, the literature that examines the benefits perceived by caregiving organizations that organize tourism activities to their members is very scarce.

Social organizations and the participation of PwD on tourism activities

SO can take different forms, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), cooperatives, charities and associations, among other typologies and designations (Fernandes Citation2000), reflecting the history of each country (Fernandes Citation2000; Ferreira Citation2009; Nogueira Citation2017). Although there is no common designation, there is consensus on the main functions that these organizations assume in society, the most common of which are “service provider”, “representational” and “advocacy” for its members (Salamon, Hems, and Chinnock Citation2000).

In Portugal, SO are part of third sector organizations (TSO) and operate in social, cultural, recreational, sports and local development areas (Nogueira Citation2017). Their main domains of intervention are social services, health and education, addressed to people with high social vulnerability (e.g. children and young people, elderly, PwD, people with economic difficulties).

Historically, PwD are one of the most excluded groups in several countries (Oliver Citation1990b), including Portugal (Fontes Citation2014; Portugal and Alves Citation2015). For social and physical reasons, PwD may need assistance and support from SO (Portugal and Alves Citation2015). This support is sometimes indispensable due to the various physical and social barriers that PwD face in various spheres of their lives, including participation in tourism activities (Fontes Citation2014). Therefore, SO are an important support for many PwD, providing daily-life support (e.g. support for feeding, personal hygiene, and companionship), therapy and rehabilitation services (e.g. occupational therapy, physiotherapy, psychotherapy), as well as support for participation in leisure activities, including tourism activities (Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011; Carneiro et al. Citation2022). Sports activities and cultural events (Abraham et al. Citation2002; Carneiro et al. Citation2022; Hall and Hewson Citation2006; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009) are examples of activities organized by SO for PwD.

Due to the characteristics of some disabilities, especially those entailing a high level of physical or intellectual dependence, many activities organized by SO have therapeutic and rehabilitation purposes (Ager et al. Citation2001). In addition, the presence of SO staff to support PwD during the activities is frequent (Ager et al. Citation2001; Ashman and Suttie Citation1996; Carneiro et al. Citation2022). This support is identified as an important pull factor in the participation of PwD, especially in cases of high level of dependency (physical or intellectual) (Ager et al. Citation2001; Verdonschot et al. Citation2009). Despite the important role of SO in enabling a considerable number of PwD to participate in leisure and tourism activities, no studies carried out in Portugal are known which analyse the view of these organizations on the needs, motivations and constraints of PwD to participate in leisure activities and the benefits they obtain from this participation. However, SO are very knowledgeable about this market, as they know its characteristics, needs and constraints, which makes them able to identify the motivations to participate and the constraints that inhibit their effective participation (Kong and Loi Citation2017). Moreover, as evidenced in the study conducted by Carneiro et al. (Citation2022), many of these organizations arrange some tourist trips, mainly domestic and short-duration trips, for their members. Additionally, these organizations also have valuable knowledge about strategies that can be used to increase the participation of PwD in leisure activities.

Methodology

Case study: Portuguese social organizations that provide support to PwD

It is estimated that in Portugal there are around 1,900,000 people aged five years or over who have a disability (INE Citation2012), a great number of them being supported by SO in their daily lives. Thus, these organizations play the role of formal caregivers for a great number of Portuguese PwD, especially for those who are institutionalized. Despite their importance, these organizations are recent in the country's history, as most of them were created after 1974.

Portuguese social organizations (PSO) have an important role in the support and representation of groups of citizens that, for some reason, live in a situation of social exclusion or have a special need (physical or intellectual), like PwD (Franco et al. Citation2005). According to the Portuguese law (Decree-law 106/Citation2013), non-governmental organizations that provide support to PwD are organizations that are not administered by the state and are non-profit organizations. These organizations have the purpose of defending the rights and legally protected interests of PwD and contribute to increasing their social participation.

In 2019, there were around 293 non-governmental organizations in Portugal that provided support to PwD registered in the National Rehabilitation Institute (INR Citation2021). These organizations represent people with different kinds of disabilities (physical, hearing, visual, intellectual), of different ages, and their families. Therefore, they are aware of the needs, motivations, constraints and benefits that PwD experience when participating in leisure and tourism activities. Thus, it is of utmost relevance to examine the view of these organizations concerning these issues.

Data collection methods

To examine the view of SO that support PwD regarding the needs, motivations, constraints and benefits obtained from their participation in leisure and tourism activities, a qualitative approach using semi-structured interviews was adopted. A sample of representatives of Portuguese caregiving organizations that support PwD (physical, hearing, visual or intellectual) were selected using a non-probability sampling technique to participate in this study. Given the lack of a database of SO supporting PwD in Portugal, an internet search on Google, between January and March 2019, using the following keywords: “formal caregivers”, “social organizations”, “disability”, “impairment”, “deaf”, “blind”, “mental disorders” and “intellectual disabilities”, was made to identify the caregiving organizations that support PwD aged 18 years or over. A database with 90 organizations was created and all organizations were invited by email to participate in this study. However, only twenty-two representatives of caregiving organizations accepted the invitation and were interviewed between February and May 2019, by two trained interviewers, most of them in person (20) and only two via Skype. The face-to-face interviews were carried out in the social organization's office. The research carried out meets the ethical principles followed by the University of Aveiro and signed informed consents were obtained. The average length of the interviews ranged from 40 to 60 min; all were audio-recorded with the interviewees’ permission and later completely transcribed and anonymised.

The interview script (Appendix 1) was designed based on Portuguese legislation (DL 163/2006) related to the accessibility of facilities and on the studies carried out by Morgan, Pritchard, and Sedgley (Citation2015) and Yau, McKercher, and Packer (Citation2004). The representatives of caregiving organizations were asked about their views on the following topics related to the participation of PwD in tourism activities: (i) travel needs; (ii) travel motivations; (iii) travel constraints; (iv) benefits obtained; (v) strategies that can be used to improve the participation of PwD in tourism activities; and (vi) characteristics of the SO (e.g. target groups, number of associates).

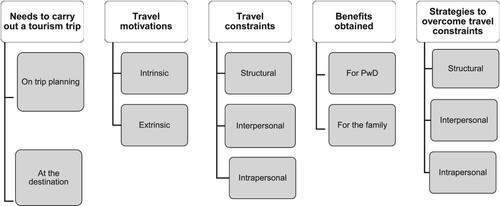

Data analyses methods

All interviews were recorded, transcribed and anonymized to guarantee the confidentiality of the participants. The content analysis method, following the procedure proposed by Denscombe (Citation2017), was used to analyse the transcriptions. Due the exploratory nature of this research, both inductive and deductive approaches were used to identify the categories and subcategories used to classify the data (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006). All the interviews’ contents were read, and the main characteristics of the phenomena were identified in discourses. Therefore, a coding scheme () was defined based on the literature review carried out (Crawford and Godbey Citation1987; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Kim and Lehto Citation2013; McCabe Citation2009; Neulinger Citation1981; Sedgley et al. Citation2017) and on the information obtained from the interviews. This methodology is particularly useful to analyse under-researched topics (Neuendorf Citation2020), as is the case of the current study. Thus, the needs to carry out tourism trips were categorized into two groups according to the stages of tourism trips (on trip planning and at the destination). The motivations were categorized based on Neulinger (Citation1981) into intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, and specific subcategories of intrinsic motivations were identified (exploring the new, socializing, learning, escape from routine, relax and personal satisfaction), based on literature (e.g. Alves et al. Citation2020; Freund et al. Citation2019; Kong and Loi Citation2017). The travel constraints and the strategies suggested to overcome travel constraints were categorized according to the model proposed by Crawford and Godbey (Citation1987). The benefits were categorized into benefits to PwD (well-being, self-esteem, new knowledge, skills to deal with unfamiliar environments and relaxation) and benefits to their families, based on the literature review (e.g. Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Kim and Lehto Citation2013) and on the discourses of the interviewees. All the discourses were categorized into categories and sub-categories, using NVivo, version 12. To meet the criteria for reliability, different researchers did the coding process and the findings were compared and the discrepancies in coding were discussed.

Results and discussion

Sample profile

summarizes the profile of caregiving organizations and of the representatives of these organizations interviewed. The sample is heterogeneous and composed by SO working with people with cognitive or intellectual disabilities (40.91%), people with physical disabilities (18.18%), people with blindness or low vision (13.64%), deaf people (13.64%), and with all types of disability (13.64%).

Table 1. Profile of the sample of social organizations interviewed.

The majority of SO are from the Central Region of Portugal (59.09%), followed by those of the North Region (22.8%) and Lisbon (13.6%). Moreover, almost half of the sample was founded after the 1990s (45.45%) and there is heterogeneity concerning the number of associates, with about 32% of the SO examined having more than 400 associates. The SO that has been operating the longest (since the 1960s) supports people with cognitive and intellectual disabilities. On the other hand, the most recent SO was founded in 2015 and works with people with physical disabilities. Moreover, the SO studied in this research according to their status are private social solidarity institutions (PSSI) and non-governmental organisations supporting PwD (NGOPwD). According to the information available in their websites, their scope of activity is service providing and advocacy to their members and families (see ).

Regarding the sociodemographic profile of the interviewees (), the sample is balanced in terms of gender and the ages range from 27 years to 86 years. Most are employed, have higher education, and do not have a disability. There is heterogeneity in terms of the role they play in the organization, ranging from volunteers, psychologists, therapists and secretaries to presidents and directors.

Needs of PwD related to the participation in tourism activities: the view of social organizations

As the previous literature highlights (e.g. Buhalis and Michopoulou Citation2011; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012), PwD have specific needs both in terms of trip planning and during a trip. The representatives of social organizations interviewed identified main needs in these two stages of a tourist trip. However, these needs differ according to the type and the degree of intensity of that disability, as highlighted in the literature review (Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012). PwD’s perception and recognition of needs regarding tourism activities started when planning the activity. In most situations, travel planning is a challenge that they cannot overcome alone and, consequently, they need the help of a caregiver (formal or informal) or of a friend (Gillovic and Mcintosh Citation2020). The narratives of interviewees show that the planning stage is a key step in the success or failure of a tourism trip. Therefore, it is essential to previously collect reliable information concerning the level of accessibility of the destination, as one interviewee explains:

Nowadays, to leave home, a person [with disabilities] must carry out exhaustive planning to know where to go, how to go, if the place where they are going has a step or not, if there is an adapted room in the hotel or not, if it is not adapted, if it has a bathtub. In other words, there must be exhaustive planning in terms of accessibility. (SO22)

During the planning stage of a tourism trip, PwD need to obtain reliable information about the level of accessibility of the destination and of the tourism services they will use (e.g. accommodation, transport, restaurants and cafés, museums and other cultural attractions). Moreover, the information provided by the TSA should be accessible, which does not happen in most cases, with many tourism supply agencies’ websites showing serious problems in terms of accessibility (Teixeira, Eusébio, and Teixeira Citation2021). Therefore, PwD have great difficulty planning their own tourism trips and, in most cases, they need support. The difficulties increase as the intensity of the disability also increases. In this vein, the accessibility of accommodation facilities is one of the most important criteria for the selection of a tourism destination, especially for people with physical and visual disabilities, as can be noted in the following testimony: “We must check if there is accessibility, what accessibility exists, if the room is accessible, or if there is the possibility of it being accessible … if the bathrooms are accessible […]” (SO2). In addition, it is crucial that accommodation establishments have qualified human resources in inclusive service, support services and safety plans adapted to the characteristics of PwD.

PwD also have specific needs in terms of transport. An accessible transport network with accurate information about the accessibility is a facilitating factor for mobility and has a positive impact on participation in tourism trips, as observed in the following discourse:

People with disabilities or their caregivers need to plan very carefully how they will move from one place to another. However, these plans depend on the type of disability. For example, if we are talking about a person who uses a wheelchair the planning should be even more careful, because it is necessary to use an adapted transport. (SO22)

PwD also have specific needs related to the use of restaurants. However, in most cases these needs are not fulfilled. The interviewees’ narratives reveal the urgency of introducing changes in this type of tourism service to ensure not only physical accessibility, but also adequate services (e.g. Braille menus, explanation of where the food is on the plate for people with visual disabilities), as one interviewee reported: “At meals, blind people do not see the content of the plate, so someone has to introduce the plate to them” (SO7).

Museums and other cultural attractions must meet a number of requirements in order to provide memorable experiences for PwD. However, the interviewees reveal that frequently the needs of PwD in this type of tourism attractions are not considered, specifically in terms of information and communication. Therefore, PwD are prevented from visiting these attractions in many cases. According to the interviewees’ opinions, these TSA should invest in alternative methods of communication (e.g. accessible language, pictograms), audio descriptions, replicas (touchable experiences for the blind), and in information in Braille and in Portuguese sign language (PSL) in order to facilitate access to these cultural facilities for all PwD (physical, hearing, visual and intellectual). The absence of these solutions makes the planning of visits, as well as access to these tourism facilities, difficult, as can be observed in the following testimony:

The absence of information in accessible formats, for example Braille, audio description, Portuguese sign language and tactile maps of the space, as well as access barriers to the museums, for example if there are floors without elevators, prevent people with disabilities from visiting museums. (SO15)

Although the planning stage of a tourism trip is crucial to have memorable tourism experiences, the interviewees reveal that in a great number of situations the existence of barriers is only noticed during the visit. These barriers are frequently related to the lack of adequate and reliable information concerning the accessibility level of the tourism products, as the following example discourse illustrates: “Many times, they say it [the hotel] is adapted but then [at the destination] the bathroom is so small that it does not allow a wheelchair to move around” (SO22). This reveals the importance of having correct information about accessibility in the communication channels used by the service providers (e.g. websites) (Teixeira, Eusébio, and Teixeira Citation2021).

Travel motivations of PwD: the view of social organizations

According to the opinion of the interviewees, PwD have the same motivations to participate in tourism activities as other citizens if their needs are fulfilled, as can be observed in the following testimony: “The motivation is exactly the same as for people who have no problems at all: to go out, to have fun, to go on holiday, to spend some very pleasant days with friends, to meet new people (…).” (SO15).

In the opinion of the interviewees (see ) the main motivations of PwD for participating in tourism activities are: exploration (e.g. exploring new places, trying new things), socialization (e.g. meeting new people, socializing with friends), learning (e.g. learning about different cultures and ways of life, knowing new things), escaping from routine (escaping from daily routine, staying away from home, exchange experiences), relaxation (relieving stress and tension, relaxing and resting, being in a calm environment) and personal satisfaction (e.g. having fun). These results are in line with the motivations identified in studies on the view of PwD which were reviewed in the literature review section (e.g. Allan Citation2015; Lyu, Oh, and Lee Citation2013; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Moura, Eusébio, and Devile Citation2022; Shi, Cole, and Chancellor Citation2012).

Table 2. Travel motivations.

These results show a clear combination of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, although, in the narratives, the interviewees placed more emphasis on the intrinsic motivations, in line with the findings of other studies (Crompton Citation1979; Iso-Ahola Citation1980; Allan Citation2015; Moura, Eusébio, and Devile Citation2022). In addition, in the opinions of the SO, although PwD are attracted by the characteristics of destinations (extrinsic motivations), they seek to take something that benefits them individually from the tourism experience (e.g. learning, exploring the new). This is also in line with the results of other studies (e.g. Allan Citation2015). Therefore, the view of the interviewees concerning travel motivations of PwD is similar to the view of PwD.

Travel constraints of PwD: the view of social organizations

The representatives of caregiving organizations interviewed highlight several constraints that prevent the participation of PwD in tourism activities. However, these constraints differ according to the type and intensity of the disability. The travel constraints most identified in narratives of those interviewed are structural constraints, with a particular focus on the absence of physical accessibility. These results are in line with the literature that examines the perspective of PwD regarding their travel constraints (e.g. Alves et al. Citation2020; Daniels, Rodgers, and Wiggins Citation2005; Devile and Kastenholz Citation2018) and with the literature that examines the view of caregivers (e.g. Freund et al. Citation2019; Nyman, Westin, and Carson Citation2018; Innes, Page, and Cutler Citation2015; Kong and Loi Citation2017). Thus, the interviewees identified a lack of accessibility in accommodation, transport, restaurants, museums and other tourism attractions and public spaces.

According to the views of the interviewees, the majority of public spaces in tourism destinations continue to be inaccessible for people with mobility issues. Architectural barriers constitute an obstacle to the full exercise of citizenship, including the right to participate in tourism activities. The presence of multiple obstacles (e.g. steps, lack of handrails, ramps and elevators, lack of adapted bathrooms and narrow doors) limits the mobility of PwD in public spaces, as can be seen in the following testimony: “We still do not have ramps on the pavements to cross, we still do not have lowering of pedestrian crossings … we still do not have signs for the blind when they use a pedestrian crossing” (SO20).

Most interviewees mention that the lack of transport adapted to the needs of PwD is also a strong constraint. The barriers most identified are no accessible entrances and exits, reduced number of places for PwD, reduced space in the transport and lack of information in alternative formats (e.g. audible). Thus, the environment becomes extremely aggressive for PwD, as one interviewee explained:

We found a bus, but it had no accessibility, or had a damaged ramp. The person arrives at the metro and the elevator is damaged, or the metro station is not accessible, or the pavement next to the bus stop will not be lowered and the person gets off the bus but must go on the road [with wheelchair]. There are several problems related to transport in Portugal. (SO22)

Although structural constraints are the most referred to by the interviewees, PwD also face various difficulties in the interaction with others (interpersonal constraints), which jeopardize their choices and participation in tourism activities. The lack of knowledge of characteristics and needs by service providers has an impact on the quality of information provided and the communication with consumers with accessibility requirements. Communicational (e.g. lack of knowledge of PSL) and attitudinal barriers (e.g. social stereotypes and prejudice) occur frequently in tourism destinations, as corroborated by the following excerpts:

The tourism supply agents should be sensitive to receive people differently or with better knowledge of sign language. The issue of deafness is a bit complex because if it is a ramp, it might take years, but you make the ramp, and it is there. A deaf person needs a service, so that [the communication] must exist. (SO8)

I notice that there is embarrassment because people do not have contact with people with disabilities [… .]. However, despite the goodwill they have, they do not know how to deal with people with specific needs. (SO15)

There is still a long way to go … a substantial change in mentality to make everything accessible. People in hotels, in restaurants and so on must know how to act when they receive PwD. (SO22)

The lack of knowledge of service providers about specific needs of PwD provokes insecurity and hinders their participation in tourism activities in unknown places, especially without companions (e.g. family, friends, or SO). This dependence on a companion is one of the main intrapersonal constraints identified by the interviewees and is intricately linked to the other constraints identified earlier.

Benefits obtained: the view of social organizations

The opinion of the interviewees is in line with the results obtained in previous studies (e.g. Blichfeldt and Nicolaisen Citation2011; Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; McCabe Citation2009) concerning the benefits obtained by PwD from participation in tourism activities. According to the interviewees, participation in tourism activities has a crucial role in increasing the well-being and quality of life of PwD, as well as of their families. All the interviewees revealed that participation of PwD in tourism activities improves their lives, specifically contributing to increasing their well-being, self-esteem, obtaining knew knowledge, acquiring skills to deal with unfamiliar environments and relaxing/recovering, as can be observed in the testimonies presented in . Therefore, the perspective of SO is similar to the perspective of PwD.

Table 3. Benefits obtained.

The interviewees also revealed that the benefits obtained with the participation of PwD in tourism activities also extend to their families. The narratives emphasize especially the fact that participation in such activities is often the only opportunity for families to take a break from their caring role ().

Strategies to overcome the travel constraints of PwD: the view of social organizations

Due to their experience in organizing some tourism activities for some of the social organizations interviewed in this study, the strategies suggested by the interviewees for overcoming some of the travel constraints (structural, interpersonal and intrapersonal) faced by PwD were also analysed.

Most interviewees identified physical barriers as one of the most persistent constraints for PwD when engaging in tourism activities. Thus, these barriers must be removed in public and private spaces to increase participation, as the following testimony shows: “As long as access to the surroundings is ensured, it will certainly increase the level of participation in tourism, similarly to the general population” (SO17).

The interviewees also consider important to invest in measures to assess the real conditions of the TSA, to avoid many of the identified constraints. Therefore, they advocate the creation of a seal which certifies that tourism products meet all the accessibility requirements, as can be observed in the following excerpts:

There has to be more interest in investing in certification … . A certain type of seal I think helps to give people greater security. (SO03)

It is important to try to help, because the tourism offer doesn't know what it takes [to be accessible] … for example, to be an inclusive hotel, to have that seal [certification], you need to have this and this and this. (SO01)

Due to the situation of economic vulnerability of most PwD and their families, interviewees present social tourism initiatives as a solution to increase the participation of PwD in tourism activities, involving public organizations as well as TSA, for example. These initiatives are crucial to intensify the level of participation of socially and economically disadvantaged groups in tourism activities, as can be observed in the following testimonies:

The economic reality in Portugal makes social tourism a way of making tourism for all. Social tourism is extremely important to respond to this public. (SO02)

This also goes through the economic aspect; the families we support are families with limited economic conditions. There should also be an accessible offer at the economic level, which responds to people who tend to have low economic resources. (SO14)

Given the relevance of the family in providing care to PwD in Portugal (Portugal and Alves Citation2015), the interviewees also stated that social tourism initiatives should be extended to families. Hence, they consider it to be of utmost relevance to create conditions so that PwD can take holidays with their families, as can be noted in the following testimony: “Why not provide free holiday camps for PwD with their families? Because together, they feel stronger” (SO17).

According to the interviewees’ opinion, the safety of PwD when travelling is another issue that should receive special attention from all those involved in the supply of tourism products. Therefore, it is necessary to create conditions for PwD to feel secure, go out and enjoy the tourism trips. For the interviewees, confidence in TSA depends not only on structural changes, but also on inclusive attendance. PwD need to feel that tourism staff are attentive and sensitive to their needs. Thus, changes in attendance are crucial to overcome these constraints, as can be observed in the following testimony:

They need to feel safe; they need to feel listened to; they need to feel that those on the other side are not paternalistic and are not condescending to them and their needs, while they take their requests and the needs that are presented very seriously. They need to be treated as equals, they need to feel that they are being treated as another person, that they pay for a service, that they enjoy a tourism activity and that they have the same rights. That their privacy is respected. That when trying to help, they do not interfere or are not intrusive. (SO22)

Conclusions and implications

This study provides relevant insights to improve knowledge on needs, motivations, constraints and benefits of PwD related to participation in tourism activities. Given the importance of formal caregivers, in Portugal, specifically social organizations that provide caregiving services to PwD, the view of the people responsible for these organizations was examined. The results obtained reveal that the perspectives of these formal caregivers are similar to those of PwD.

The scarcity of studies published in this field makes this study innovative and of great relevance in increasing theoretical knowledge in an area that has been little explored in the literature. Moreover, the results obtained in this study are also relevant for the TSA to know the needs of this market, their motivations and the main barriers to participating in tourism activities they encounter. Thus, theoretical and practical contributions may be highlighted.

From a theoretical point of view, this study provides relevant contributions to a better understanding of the accessible tourism market, specifically PwD, identifying a set of needs not only related to the planning of a tourism trip, but also related to the tourism trip carried out. Moreover, the travel motivations identified, in line with other studies (e.g. Figueiredo, Kastenholz, and Eusébio Citation2012; Moura, Eusébio, and Devile Citation2022), highlight the importance of intrinsic motivations, especially those related to obtaining personal benefits. Concerning the travel constraints, based on the theoretical model proposed by Crawford and Godbey (Citation1987) about leisure constraints, the findings obtained in this study highlight structural constraints as strong inhibitors to participation of PwD in tourism activities. Thus, the findings reveal that these constraints hinder the concretization of preferences in tourism practices, since these constraints prevent PwD from really doing what they want. The impact that the identified constraints have on the lives of PwD is detrimental to all aspects of their social life, as these constraints constitute an obstacle to the full exercise of citizenship, since they prevent or limit PwD from taking part in tourism experiences like any other citizen.

The identified constraints not only negatively affect PwD and their families, but also have a negative impact on the revenues of tourism enterprises, given that they are not offering a product adapted to the needs of this market. Thus, various practical contributions of this study can be identified. First, the results obtained regarding the needs of this market at the planning stage of a tourism trip and during a trip, as well as the travel constraints found, can be used by those responsible for developing tourism activities (public and private organizations). The accessibility of the tourism products offered can be improved, as can the physical accessibility of facilities, providing information on the accessibility of services in an accessible way, developing specific security plans for this market and improving the skills of staff in terms of inclusive attendance. The market of PwD should not be neglected by the tourism industry, not only because it is an excellent business opportunity, but also out of social responsibility. Second, this study also provides relevant contributions for social policymakers. Due to the benefits that PwD and their families obtain from participation in tourism activities, it is crucial to promote social tourism initiatives that facilitate the participation of PwD and their families in tourism activities. These initiatives are even more relevant due to the great financial constraints of most of these families. Third, due to the relevant role that PSO play in the lives of PwD, the findings of this study also serve to disseminate the benefits associated with the practice of tourism activities, contributing to increased awareness of these organizations regarding the importance of incorporating more tourism activities in the group of activities they offer to their members/associates. Finally, the results obtained also reveal that to increase the accessibility level of tourism products, it is of utmost relevance to provide training in accessible tourism in tourism education programmes. The insufficient knowledge about the characteristics and needs of PwD prevent tourism human resources from working with this market. There is a need for well-trained staff who are able to respond to the needs of a growing heterogeneous market and have a helpful attitude and spontaneity in social interaction with customers with special needs.

Despite the relevant contributions of this study some limitations may be pointed out. It is an exploratory case study, carried out in one single country (Portugal), and based only on the narratives of the SO that provide support to PwD. The perspectives of PwD were not examined nor those of their informal caregivers. Therefore, more studies should be carried out on this topic in other countries, also involving the informal caregivers. Moreover, the view of PwD should also be examined, to increase knowledge in this area and to make leisure and tourism accessible for all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abraham, C., N. Gregory, L. Wolf, and R. Pemberton. 2002. “Self-Esteem, Stigma and Community Participation Amongst People with Learning Difficulties Living in the Community.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 12 (6): 430–43. doi:10.1002/casp.695.

- Adam, I., A. Kumi-Kyereme, and K. Adutwum. 2017. “Leisure Motivation of People with Physical and Visual Disabilities in Ghana.” Leisure Studies 36 (3): 315–328. doi:10.1080/02614367.2016.1182203.

- Ager, A., F. Myers, P. Kerr, S. Myles, and A. Green. 2001. “Moving Home: Social Integration for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities Resettling Into Community Provision.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 14 (4): 392–400. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3148.2001.00082.x.

- Allan, M. 2015. “Accessible Tourism in Jordan: Travel Constrains and Motivations.” European Journal of Tourism Research 10: 109–19. doi:10.54055/ejtr.v10i.182.

- Alves, J. P., C. Eusébio, L. Saraiva, and L. Teixeira. 2020. “‘Quero Ir, Mas Tenho Que Ficar’: Constrangimentos Às Práticas Turísticas Do Mercado de Turismo Acessível Em Portugal.” Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento 34 (Novembro): 81–97. doi:10.34624/rtd.v0i34.22348.

- Ashman, A. F., and J. N. Suttie. 1996. “Social and Community Involvement of Older Australians with Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 40: 120–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.1996.719719.x.

- Bauer, I. 2018. “When Travel Is a Challenge: Travel Medicine and the ‘Dis-Abled’ Traveller.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 22 (February): 66–72. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.02.001.

- Benjamin, S., E. Bottone, and M. Lee. 2021. “Beyond Accessibility: Exploring the Representation of People with Disabilities in Tourism Promotional Materials.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 29 (2–3): 295–313. doi:10.1080/09669582.2020.1755295.

- Bergier, B., J. Bergier, and Z. Kubińska. 2010. “Environmental Determinants of Participation in Tourism and Recreation of People with Varying Degrees of Disability.” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 73 (17–18): 1134–40. doi:10.1080/15287394.2010.491042.

- Blichfeldt, B., and J. Nicolaisen. 2011. “Disabled Travel: Not Easy, but Doable.” Current Issues in Tourism 14 (1): 79–102. doi:10.1080/13683500903370159.

- Buhalis, D., and E. Michopoulou. 2011. “Information-Enabled Tourism Destination Marketing: Addressing the Accessibility Market.” Current Issues in Tourism 14 (2): 145–68. doi:10.1080/13683501003653361.

- Burns, N., K. Paterson, and N. Watson. 2009. “An Inclusive Outdoors? Disabled People’s Experiences of Countryside Leisure Services.” Leisure Studies 28 (4): 403–417. doi:10.1080/02614360903071704.

- Card, J., S. Cole, and A. Humphrey. 2006. “A Comparison of the Accessibility and Attitudinal Barriers Model: Travel Providers and Travelers with Physical Disabilities.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 11 (2): 161–75. doi:10.1080/10941660600727566.

- Carneiro, M. J., J. P. Alves, C. Eusébio, L. Saraiva, and L. Teixeira. 2022. “The Role of Social Organisations in the Promotion of Recreation and Tourism Activities for People with Special Needs.” European Journal of Tourism Research 30 (October): 3013. doi:10.54055/ejtr.v30i.2153.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., R. Gavendo, and E. Blackburn. 2019. “Activity Preferences of Persons with Dementia: An Examination of Reports by Formal and Informal Caregivers.” Dementia 18 (6): 2036–2048. doi:10.1177/1471301217740716.

- Crawford, D. W., and G. Godbey. 1987. “Reconceptualizing Barriers to Family Leisure.” Leisure Sciences 9 (2): 119–27. doi:10.1080/01490408709512151.

- Crawford, D., E. L. Jackson, and G. Godbey. 1991. “A Hierarchial Model of Leisure Constraints.” Leisure Sciences 13: 309–320. doi:10.1080/01490409109513147.

- Crompton, J. L. 1979. “Motivations for Pleasure Vacation.” Annals of Tourism Research 6: 408–424. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(79)90004-5.

- Daniels, M., E. Rodgers, and B. Wiggins. 2005. “‘Travel Tales’: An Interpretive Analysis of Constraints and Negotiations to Pleasure Travel as Experienced by Persons with Physical Disabilities.” Tourism Management 26 (6): 919–30. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2004.06.010.

- Darcy, S., B. Cameron, and S. Pegg. 2010. “Accessible Tourism and Sustainability: A Discussion and Case Study.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18 (4): 515–37. doi:10.1080/09669581003690668.

- Darcy, S., B. McKercher, and S. Schweinsberg. 2020. “From Tourism and Disability to Accessible Tourism: A Perspective Article.” Tourism Review 75 (1): 140–44. doi:10.1108/TR-07-2019-0323.

- Decree-law 106/2003. 30th of July.

- Denscombe, M. 2017. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. New York: Open University Press.

- Devile, E., and E. Kastenholz. 2018. “Accessible Tourism Experiences: The Voice of People with Visual Disabilities Visual Disabilities.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 10 (3): 265–285. doi:10.1080/19407963.2018.1470183.

- Evans, T., M. Bellon, and B. Matthews. 2017. “Leisure as a Human Right: An Exploration of People with Disabilities’ Perceptions of Leisure, Arts and Recreation Participation Through Australian Community Access Services.” Annals of Leisure Research 20 (3): 331–348. doi:10.1080/11745398.2017.1307120.

- Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5: 80–92. doi:10.1177/160940690600500107.

- Fernandes, R. 2000. Terceiro Setor - Desenvolvimento Social Sustentado. Rio de Janeiro: GIFE, Terra e Paz.

- Ferreira, S. 2009. “Terceiro Setor.” In Dicionário Internacional da Outra Economia, edited by A. D. Cattani, J. L. Laville, L. I. Gaiger, and P. Hespanha. Coimbra: Almedina.

- Figueiredo, E., E. Kastenholz, and C. Eusébio. 2012. “How Diverse Are Tourists with Disabilities? A Pilot Study on Accessible Leisure Tourism Experiences in Portugal.” International Journal of Tourism Research 14: 531–50. doi:10.1002/jtr.

- Fontes, F. 2014. “The Portuguese Disabled People’s Movement: Development, Demands and Outcomes.” Disability and Society 29 (9): 1398–1411. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.934442.

- Franco, R., S. W. Sokolowski, E. M. H. Hairel, and L. M. Salamon. 2005. O Sector Não Lucrativo Português: Uma Perspectiva Comparada. Lisbon: Universidade Católica Portuguesa/John Hopkins University.

- Freund, D., M. C. Chiscano, G. Hernandez-Maskivker, M. Guix, A. Iñesta, and Castelló Montserrat. 2019. “Enhancing the Hospitality Customer Experience of Families with Children on the Autism Spectrum Disorder.” International Journal of Tourism Research 21 (5): 606–14. doi:10.1002/jtr.2284.

- Froehlich-Grobe, K., M. Douglas, C. Ochoa, and A. Betts. 2021. “Social Determinants of Health and Disability.” Public Health Perspectives on Disability, 53–89. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0888-3_3.

- Gillovic, B. 2019. Experiences of Care at the Nexus of Intellectual Disability and Leisure Travel. Hamilton: University of Waikato.

- Gillovic, B., and A. Mcintosh. 2020. “Accessibility and Inclusive Tourism Development: Current State and Future Agenda.” Sustainability 12 (22):9722. doi:10.3390/su12229722.

- Gladwell, N., and L. A. Bedini. 2004. “In Search of Lost Leisure: The Impact of Caregiving on Leisure Travel.” Tourism Management 25 (6): 685–693. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.003.

- Hall, L., and S. Hewson 2006. “The Community Links of People with Intellectual Disabilities.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 19: 204–7. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2005.00249.x.

- Hansen, M., A. Fyall, R. Macpherson, and J. Horley. 2021. “The Role of Occupational Therapy in Accessible Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research, 103145. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2021.103145.

- ICF. 2002. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- INE. 2012. Resultados Definitivos. In Censos 2011. https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid = CENSOS&xpgid = ine_censos_publicacao_det&contexto = pu&PUBLICACOESpub_boui = 73212469&PUBLICACOESmodo = 2&selTab = tab1&pcensos = 61969554.

- Innes, A., S. J. Page, and C. Cutler. 2015. “Barriers to Leisure Participation for People with Dementia and Their Carers: An Exploratory Analysis of Carer and People with Dementia’s Experiences.” Dementia 15 (6): 1643–65. doi:10.1177/1471301215570346.

- INR. 2021. “ONGPD Registadas”. Last modified November 20, 2021. https://www.inr.pt/ongpd-registadas.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. 1980. The Social Psychology of Recreation and Leisure. Dubuque: William C Brown Pub.

- Jackson, E. L. 2000. “Will Research on Leisure Constraints Still Be Relevant in the Twenty-first Century?” Journal of Leisure Research 32 (1): 62–68. doi:10.1080/00222216.2000.11949887.

- Kastenholz, E., C. Eusébio, and E. Figueiredo. 2015. “Contributions of Tourism to Social Inclusion of Persons with Disability.” Disability & Society 30 (8): 1259–81. doi:10.1080/09687599.2015.1075868.

- Kim, S., and X. Y. Lehto. 2013. “Travel by Families with Children Possessing Disabilities: Motives and Activities.” Tourism Management 37 (August): 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.011.

- Kong, W., and K. Loi. 2017. “The Barriers to Holiday-Taking for Visually Impaired Tourists and Their Families.” Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 32: 99–107. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2017.06.001.

- Lyu, S. O., C.-O. Oh, and H. Lee. 2013. “The Influence of Extraversion on Leisure Constraints Negotiation Process.” Journal of Leisure Research 45 (2): 233–252. DOI: 10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i2-3013.

- McCabe, S. 2009. “Who Needs a Holiday? Evaluating Social Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 36 (4): 667–88. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2009.06.005.

- Melbøe, L., and B. Ytterhus. 2017. “Disability Leisure: In What Kind of Activities, and When and How Do Youths with Intellectual Disabilities Participate?” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19 (3): 245–55. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1264467.

- Morgan, N., A. Pritchard, and D. Sedgley. 2015. “Social Tourism and Well-Being in Later Life.” Annals of Tourism Research 52 (May): 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.015.

- Moura, A., C. Eusébio, and E. Devile. 2022. “The ‘Why’ and ‘What For’ of Participation in Tourism Activities: Travel Motivations of People with Disabilities.” Current Issues in Tourism, doi:10.1080/13683500.2022.2044292.

- Moura, A., E. Kastenholz, and A. Pereira. 2018. “Accessible Tourism and Its Benefits for Coping with Stress.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 10 (3): 241–64. doi:10.1080/19407963.2017.1409750.

- Neuendorf, K. 2020. “Defining Content Analysis.” In The Content Analysis Guidebook, edited by K. A. Neuendorf, 1–35. London: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781071802878.N1.

- Neulinger, J. 1981. The Psychology of Leisure. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

- Nogueira, R. 2017. “Caracterização das Instituições do Terceiro Setor que Compõem a União de Instituições Particulares de Solidariedade Social.” Master Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Escola Superior de Economia e Gestão.

- Nyaupane, G. P., and K. L. Andereck. 2008. “Understanding Travel Constraints: Application and Extension of a Leisure Constraints Model.” Journal of Travel Research 46 (4): 433–39. doi:10.1177/0047287507308325.

- Nyman, E., K. Westin, and D. Carson. 2018. “Tourism Destination Choice Sets for Families with Wheelchair-Bound Children.” Tourism Recreation Research 43 (1): 26–38. doi:10.1080/02508281.2017.1362172.

- Oliver, M. 1990a. “The Ideological Construction of Disability.” In The Politics of Disablement, edited by M. Oliver, 43–59. London: Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1_4.

- Oliver, M. 1990b. The Politics of Disablement. London: Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-20895-1.

- Patterson, I., and A. Balderas. 2020. “Continuing and Emerging Trends of Senior Tourism: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Population Ageing 13 (3): 385–99. doi:10.1007/s12062-018-9228-4.

- Patterson, I., and S. Pegg. 2009. “Serious Leisure and People with Intellectual Disabilities: Benefits and Opportunities.” Leisure Studies 28 (4): 387–402. doi:10.1080/02614360903071688.

- Portugal, S., and J. Alves. 2015. “Doenças Raras e Cuidado: Um Olhar a Partir Das Redes Sociais.” In Um Olhar Social Para o Paciente Actas Do I Congresso Iberoamericano de Doenças Raras, edited by R. Barbosa, and S. Portugal, 34–40. Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Sociais.

- Ray, N., and M. Ryder. 2003. “‘Ebilities’ Tourism: An Exploratory Discussion of the Travel Needs and Motivations of the Mobility-Disabled.” Tourism Management 24 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00037-7.

- Richards, V., A. Pritchard, and N. Morgan. 2010. “(Re)Envisioning Tourism and Visual Impairment.” Annals of Tourism Research 37 (4): 1097–1116. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2010.04.011.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 25 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020.

- Salamon, L. M., L. C. Hems, and K. Chinnock. 2000. The Nonprofit Sector: For What and for Whom? Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies.

- Sedgley, D., A. Pritchard, N. Morgan, and P. Hanna. 2017. “Tourism and Autism: Journeys of Mixed Emotions.” Annals of Tourism Research 66 (September): 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.009.

- Shakespeare, T. 1996. “Disability, Identity and Difference.” In Exploring the Divide, edited by C. Barnes, and G. Mercer, 94–113. Leeds: The Disability Press.

- Shaw, G., and T. Coles. 2004. “Disability, Holiday Making and the Tourism Industry in the UK: A Preliminary Survey.” Tourism Management 25 (3): 397–403. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00139-0.

- Shi, L., S. Cole, and H. C. Chancellor. 2012. “Understanding Leisure Travel Motivations of Travelers with Acquired Mobility Impairments.” Tourism Management 33 (1): 228–31. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.02.007.

- Singleton, J., and S. Darcy. 2013. “‘Cultural Life’, Disability, Inclusion and Citizenship: Moving Beyond Leisure in Isolation.” Annals of Leisure Research 16 (3): 183–192. doi:10.1080/11745398.2013.826124.

- Small, J., S. Darcy, and T. Packer. 2012. “The Embodied Tourist Experiences of People with Vision Impairment: Management Implications Beyond the Visual Gaze.” Tourism Management 33 (4): 941–50. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2011.09.015.

- Teixeira, P., C. Eusébio, and L. Teixeira. 2021. “Diversity of web Accessibility in Tourism: Evidence Based on a Literature Review.” Technology and Disability 33 (4): 253–272. doi:10.3233/TAD-210341.

- Thomas, T. 2018. “Inclusions and Exclusions of Social Tourism.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Innovation in Hospitality and Tourism 7 (1): 85–99.