ABSTRACT

As in many countries, lockdown measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa resulted in the large-scale cancellation of cultural festivals. To preserve business continuity, many festivals shifted to online events to continue providing value for audiences, sponsors and artists. This paper focuses on the experiences of two of the oldest and largest mixed festivals in the country: The National Arts Festival and the Klein Karoo Nationale Kunstefees. Both festivals adapted by shifting online, necessitating significant programme, business model, and management innovation. Using the framework provided by the literature on visitor leisure experiences and e-eventscapes, the paper questions how arts festivals have achieved new e-eventscapes alongside providing online cultural programming. The paper uses a mixed methods research approach to analyse the experiences of festival managers and audiences in the differing approaches developed by the two festivals. Theoretical and practical implications from the study are discussed in the conclusions.

Introduction

Cultural festivals play important roles in building social cohesion through the creation of collective identities and social capital (Carneiro et al. Citation2019). This is especially important in multicultural societies, like South Africa, which is still recovering from the deeply socially divisive policies of apartheid.

In addition to their local economic impact through cultural tourism, festivals also provide important non-market intrinsic and social impacts through the way that audiences experience the event itself (Ellis et al. Citation2019). The festival eventscape plays a vital role in the ways in which festivalgoers interact with both the festival content and fellow attendees, and thus in the value of the experience (Richards Citation2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many festivals, in South Africa and around the world, to transition suddenly from their traditional in-person to online formats as the only way in which festival continuity could be maintained. Lockdown measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa resulted in the large-scale cancellation of many cultural festivals and events in 2020 and 2021: Of the 230 cultural festivals that took place in 2019, only 122 were held in 2020, and only 95 in 2021 (Drummond Citation2021). The majority of those that continued to take place pivoted to digital formats. This led to a period of intense disruption and innovation for festival managers and artistic producers, who had to learn new skills and develop new business models and techniques in order to deliver on their mandate to sponsors, creatives and audiences.

While there has been research on production (supply-side) shift to online platforms (Estanyol Citation2022; Hanzlík and Mazierska Citation2022; Valck and Damiens Citation2020), Richards (Citation2019) notes that there is a more limited body of work on audience (demand-side) impacts. This paper seeks to fill a gap by bringing these together. Experiences are designed by event managers with certain goals or aims in mind, but the ways in which participants engage with these are not completely controlled by organizers. Ellis et al. (Citation2019, 100) argue that ‘participants thus are co-creators of their own experiences’ through their cognitive engagement with the event (Bosworth Citation2021). By drawing on theories of ‘e-eventscapes’ (Bosworth Citation2021), this paper seeks to determine how the experiences designed by festival managers link with the experiences of online festival audiences.

The shift to online festivals offered some demand-side advantages, such as improving audience geographical reach and accessibility (Jess-Cooke Citation2020; Lee, Baker, and Haywood Citation2020). However, in the South African context where only 9% of households have access to fixed line internet at home (Stats SA Citation2019), online provision can also be exclusionary, especially for lower income groups. Screen fatigue and the lack of social interaction have also been reported as barriers to participation in online events in many countries (Chapple et al. Citation2023; Mulet Citation2021; Sargent Citation2021). On the supply-side, for organizers, the financial sustainability of online events is also a challenge (Fernandes Citation2020; Layman Citation2020).

This paper aims to add to the growing literature on how audiences experience online festivals, and thus whether online or hybrid event formats are a sustainable future strategy for festivals wishing to continue capitalizing on some of the benefits of this format. The research takes a mixed methods approach including focus group discussions with festival managers during the COVID-19 period, as well as online audience surveys, and the use of other data sources (such as Google Analytics) to track the experiences of online festivalgoers and their responses to the new format.

As case studies, two very different national mixed arts festivals in South Africa were considered: The National Arts Festival, which is one of the oldest and largest mixed cultural festivals in South Africa with a strong focus on artistic content and quality; and the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (KKNK), which is a more recently established Afrikaans-medium cultural festival with more of a focus on the social and tourism aspects of the event.

The first sections of the paper review the literature on how cultural festivals internationally have shifted online, and the ways in which eventscapes and e-eventscapes influence festival visitor experiences. Section ‘Research methods and data’ introduces the case studies, followed by the research design and methods. Results are divided into two sections: a thematic analysis of the focus group data from festival organizers and sponsors with a focus on their thinking about continuity and audience experience; followed by an analysis of quantitative survey and online data that captures the experiences of festival visitors themselves. The discussion reflects on, and contrasts, the impacts of the sudden shift to the online format of these two events, and draws conclusions about how future festivals can learn from these experiences in their own online and hybrid strategies.

Understanding online festivals: a literature review

Pivot to digital: the shift to online festivals

The shift to online platforms as a result of the global COVID-19 pandemic, has made digital cultural participation a major area of study. Internationally, the shift to online cultural consumption had already started to take place before the lockdown, although the COVID-19 pandemic sped up the trend (Nobre Citation2020).

Online cultural participation and consumption have some potential advantages, such as allowing larger and more geographically spread audiences to access the content. Online participation ‘ … exposes little-known … micro-cultures to a larger, newer and geographically more dispersed audience, giving cultural diversity a whole new level of expression’ (Lee, Baker, and Haywood Citation2020). It may also be more inclusive in some ways, since those with mobility difficulties or family care responsibilities can join from home (Jess-Cooke Citation2020).

However, there are also challenges associated with the shift to online, such as the inclusion of those without the means to access digital content, the effective monetization of online content so that sustainable business models can be developed, and (in an African setting) the inclusion of informal economic activity, which was largely suppressed during the COVID-19 lockdown period (Arndt et al. Citation2020).

Writing early in the pandemic Mair (Citation2020) and Davies (Citation2020) suggested that there were four possible scenarios, or ‘potential futures’ for festivals. Two of these, capitalism and barbarism, leave festivals essentially unprotected and unsupported, which is likely to lead to smaller, non-profit events being closed down, as only those who are financially most secure and are resilient to anti-social behaviour (increased levels of crime and fraud) will survive. Exploitative labour practices, such as zero-hour contracts, will increase, as will fraudulent activities, such as black-market ticket sales.

However, there is also the potential for very positive outcomes for festivals. In ‘state socialism’ the important social roles that festivals play is recognized (although the authors think it unlikely that they would be regarded as essential services in the same way as food, shelter, or energy), and at least some financial support is provided, ensuring a higher level of survival. The best scenario is ‘transformation into a big society built on mutual aid’ (Mair Citation2020). In this case, networks between artists and festival organizers, as well as between artists themselves, are strengthened and used to promote emerging artists, thus increasing the diversity of offerings (Davies Citation2020).

For online festival adaptations to be sustainable, new business models will need to be developed. Central to the financial sustainability of many festivals is sponsorship from private-sector companies. In return for financing, sponsors access festival audiences for marketing and branding purposes (Dholakia Citation2020; Hubbard Citation2020). However, few festivals have experience in online sponsor promotion, and to retain current sponsors, festivals will need to be innovative in the kinds of exposure and marketing opportunities that they offer sponsors in the digital environment (Fernandes Citation2020; Layman Citation2020). Festival organizers have also had to develop new social media strategies in order to retain and build an online community that is more likely to support the digital editions of their event (Mello Citation2020).

Online festival experiences and eventscapes

Richards (Citation2019) argues that, although there has been much research on the patterns of consumption of cultural services in relation to the attributes of consumers, there has been less on visitor experience, and what factors contribute to such experiences, which are essentially subjective and personal. The experience depends on the individual, but also the characteristics of the specific event and the context in which it happens. Pulh (Citation2022, 64) distinguishes different components of festival experiences that make each ‘festivalscape’ unique: ‘the experience occurs when it uses mechanisms to immerse the customer in a memorable event’. As Ellis et al. (Citation2019, 101) point out, in ‘structured experiences’ such as festivals, ‘providers can invite engagement, immersion, and absorption in activities through carefully designed and staged encounters’ however they ‘do not control the subjective experience or the observable behavior of the guest or participant’. Therefore, there is a degree of uncertainty and diversity in planning festivals that mean even similar content can be experienced in very different ways. Different kinds of festivals gain their competitive advantage by focusing of different components of ‘experience-reinforcing levers’ (Pulh Citation2022). For example, some events sell themselves as being strongly linked to a particular venue or place which gives the festival its identity. Others may focus on the product – the quality and quantity of the programme of cultural offerings. The important point is that each event needs to have a differentiation strategy so that they can appeal to audiences by offering a unique experience.

Richards (Citation2019) builds on the work of Gues, Richards, and Toepoel (Citation2015) to develop an Event Experience Scale (ESS) in order to better understand factors that influence visitor experiences, disaggregated into different kinds of engagement including cognitive engagement, physical and affective engagement, and a ‘novelty’ dimension.

Cognitive engagement has to do with the intellect, such as interpretation, learning and gaining knowledge; Physical engagement occurs through active participation and sense perceptions; and Affective engagement describes emotional reactions, such as feelings of excitement, adventure, and intimacy (Gues, Richards, and Toepoel Citation2015). Experiencing novelty can be related to the event content (programme, design, setting) and also to what is new to the visitor in terms of their previous experiences of, and knowledge about, the event (Richards Citation2019). In an application of the ESS to a sample of cultural events, Richards (Citation2019) finds that the most important factor in explaining experience was cognitive engagement, followed by novelty, affective engagement, and physical engagement.

Cultural festival experiences are also location based – they relate to activities and settings outside of the usual environment of participants (Packer and Ballantyne Citation2016). ‘Eventscapes’ refer to physical spaces, mostly in urban environments, that provide the setting for a festival. Geographically, the eventscape consists of interrelated places that are temporarily linked together for the duration of the event (Brown et al. Citation2015). The eventscape can include physical space, the natural environment, the characteristics of the host city, visual features and symbols, the people present (attendees, sponsors, participants), the way they are dressed, and the services they provide (merchandize, food, beverages etc., also referred to as the ‘servicescape’) (Brown et al. Citation2015). Carneiro et al. (Citation2019) argue that eventscapes can describe both the physical attributes as well as the intangible elements of a festival visitor’s experience, which can include the social interactions between visitors, performers or participants, and service staff.

All these factors combine to create the ‘atmosphere’ of the event (what Pulh (Citation2022) calls the festivalscape) and can have a significant impact on the emotions that visitors associate with their festival experience, their satisfaction and consequently, their loyalty to the festival. In a study of three cultural events in Portugal, Carneiro et al. (Citation2019) find that the distinct characteristics of the eventscape of each event play an important role in the emotions, satisfaction and loyalty of attendees.

For communities that host festivals and events, the eventscape influences ‘psychic income’, that is, the emotional benefits of the event associated with the enhanced image of the host city, and feelings of pride and social cohesion. Regularly held events can leave lasting legacies for host locations, such as physical infrastructure, but also including political realignment, social networks, and business relationships (Brown et al. Citation2015). Festivals seek to represent communities in particular ways that are based on the cultural values and identities underpinning them (George Citation2015). Where the vision and values of a host community are aligned, rather than in competition, George (Citation2015, 132) finds that this offers the greatest opportunities for cultural and economic success: ‘Where individuals who help organise the festival, participate in the event, or even simply live in the areas do not agree with the version … being constructed, there will be inevitable problems.’

Bosworth (2021) extends the study of eventscapes to experiences in the digital environment, ‘e-eventscapes’, which describe the attributes of online visitor experiences through their capabilities to sense, learn and create, and link to others. The visitor experience in the online environment is influenced by the aesthetic appeal and design of the website, as well as its structure (usability and ease of navigation). He suggests that these aspects of ‘fundamental [online] infrastructure’ have a direct effect on the affective and cognitive experience of festival visitors and local stakeholders, which translates into participation and future loyalty. summarizes some of the key differences and similarities between eventscapes and e-eventscapes as identified in the literature (Bosworth 2021; Brown et al. Citation2015).

Table 1. From eventscapes to e-eventscapes.

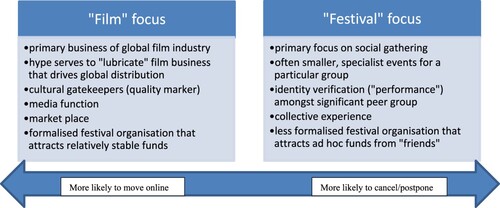

Recent research by Bachman and Hull (Citation2022) on queer film festival participation during COVID-19 highlights the potential of online participation and engagement, but notes the preference of participants for face-to-face formats. This can also be connected to recent work from De Valck (Citation2021) in relation to film festivals in general and the impact of COVID-19. The research suggests that if festivals prioritize film, focusing on their role as gatekeepers in the film industry and the distribution of film, moving online is easier, and does not necessarily impact the role of the event or audience experiences. However, for film festivals focused on the festival as an experience, that is, the event and its social functions and the collective experiences it offers, moving online is much more challenging and cancellation/postponement were more common (). The decision to shift to an online festival format depends on a combination of these factors. The two mixed arts festivals we are focusing on did have the resources to move online and decided to do so in different ways. However, for both of them, the importance of the ‘festival experience’ and ‘cultural content’ cannot be separated: arts festivals care deeply about supporting creativity and the production of new arts experiences, but also about how these are lived and make connections in real communities.

Figure 1. Film festival type and adaptation strategy. Source: Adapted from De Valck (Citation2021).

In the paper, we unpacked this juggling act in festivals where neither art or festival can be prioritized and how they adapted and responded to challenges both on the production and experience side simultaneously.

Overall, it is clear that while festival producers have focused on creating a continuity of provision from off-line (pre-pandemic) to online (during and post-pandemic) festivals, there is little research to understand how both festival managers, who design the online festival experience, and audiences, who co-create their festival experience through different kinds of engagement, connect.

Research context: South African cultural festivals and COVID-19

The COVID-19 lockdown that started in March 2020 had a severely negative effect on the South African economy overall, and on the cultural and creative industries in particular (Snowball and Gouws Citation2022). Those operating in the Performance and Celebration domain (which includes all live music, theatre, dance productions, as well as festivals) suffered a very high level of cancellations and lack of business continuity.

The National Arts Festival (NAF) and the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (KKNK) are two of the largest and oldest cultural events in South Africa. Although they have quite different characteristics, both events decided to switch to an online mode in 2020 and 2021 and agreed to participate as research partners in an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project entitled: Future Festivals South Africa: Possibilities for the Age of COVID-19. The following section of the paper gives some background context to each event including a description of the pre-COVID live festival, and the online versions.

The National Arts Festival

The National Arts Festival (NAF) was established in 1974 and is now the largest arts festival on the African continent. Held in Makhanda (Grahamstown) in the Eastern Cape, the programme usually runs for ‘11 days of amazing’. It features drama, dance, physical theatre, comedy, opera, music, jazz, visual art exhibitions, film, student theatre, street theatre, lectures, a craft fair, workshops, and awards for young South African artists (National Arts Festival Citation2021). The festival has a diverse offering that aims to reflect the cultural diversity of South Africa, foster social cohesion, and continue the festival’s history as an important platform for artistic innovation, political and social commentary (National Arts Festival Citation2021; SACO Citation2016). The festival also has a significant economic impact with the contribution of the festival to the Eastern Cape Province being valued at R214.9 million in 2019 (US$14.87 million),Footnote1 of which R85.9 million (US$6.22 million) was directly felt by the host town of Makhanda (Snowball and Antrobus Citation2019). Although parts of the in-person editions of the NAF included a Village Green craft market, pop-up restaurants and street theatre, the NAF is a winter festival, with the focus very much on the shows rather than on outdoor or social activities. An advantage of the host town is that it has a large theatre (‘The Monument’ which seats close to 1000 people in the largest auditorium), and can also utilize many indoor venues at the university and schools in the town.

Held annually in June/July, the NAF organizers had 100 days to develop and implement an adaptation strategy to COVID-19 once South Africa announced that a nationwide lockdown would take effect on 27th March 2020. Faced with only two options, to cancel or to find a way to go ahead, the NAF pivoted to a virtual festival format, one of the first festivals to do so in South Africa. The 2020 virtual festival delivered a full festival programme with works specifically designed for the online environment, and extended the usual festival timeframe ‘beyond 11 days of amazing’ (National Arts Festival Citation2021).

With lockdown restrictions having eased by the start of 2021, the NAF had planned a hybrid festival experience for its 2021 edition. The model included small COVID-compliant live shows in Makhanda and in festival hubs in cities across South Africa, as well as an online offering. However, just 10 days before the festival was due to start, South Africa entered into a strict lockdown that did not allow for live audiences. The NAF quickly regrouped and took the entire 2021 festival online with recorded and live-streamed performances.

Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees

The Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (KKNK) is South Africa’s Afrikaans ‘moederfees’ (mother festival) and has been held in Oudtshoorn in the Western Cape since 1995. The festival programme encompasses all genres of the performing and visual arts. The KKNK strives to promote accessibility to the arts, especially in Afrikaans, to diverse artists and audiences and seeks to support the creation of new and unique content. The festival also supports community development and training in the arts as well as local economic development. The economic impact of the KKNK on Oudtshoorn was R56,4 million (US$4.26 million)Footnote2 in 2018 and the impact on the Western Cape was estimated at between R161,3 million and R178,2 million (US$12.17 million to US$13.45 million) (Snowball and Antrobus Citation2018).

In character, the in-person KKNK is much more of an outdoor festival than the NAF. The history, peoples and landscapes of the town of Oudtshoorn are particularly important to the festival in creating a sense of place. Held in early autumn, much of the in-person festival is orientated around the town centre. Roads are closed off to vehicles and outdoor performances are presented on temporary stages. A wide range of food stalls and crafts are also available in this space. Unlike Makhanda, Oudtshoorn does not have a large auditorium or university venues that can be used. Larger indoor shows are presented in specially erected marquees, while smaller events utilize school facilities and the town hall.

With safety concerns mounting over the spread of COVID-19 in South Africa in March 2020, the KKNK made the decision to cancel their live event just one week before it was due to begin. The festival was in the process of being set-up in Oudtshoorn with artists and technical crews already in the town or soon to be travelling. The first part of 2020 was thus spent compensating or negotiating new contracts with audiences, artists, technical crews, suppliers and sponsors.

With strict lockdown measures in place, the KKNK chose to undertake a virtual adaptation strategy. The duration of the festival was extended until the end of 2020, as time is not a factor in the online environment. The festival programme offered recordings of previous shows as well as new content produced specifically for the virtual KKNK. Fine arts and crafts were also included in the virtual festival, with the KKNK Virtual Gallery where visual artists could display and sell work. In 2021, with safety concerns around live gatherings and lockdown restrictions still in place, the KKNK continued with the virtual festival format as their main offering and also hosted some small COVID-compliant live events for a hybrid festival format.

Research methods and data

The paper builds on data collected during an 18-month research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) in the United Kingdom, entitled: Future Festivals South Africa: Possibilities for the Age of COVID-19. The overall project used a multiple case studies approach, including 7 case studies festivals across South-Africa (Yin Citation2003), these were selected in a purposeful manner as displaying and experimenting with a range of responses to the pandemic (Comunian et al. Citation2023). Ethical clearance for research involving human subjects was obtained from both the human research ethics committees of King’s College London and Rhodes University (Review Reference: 2021-2838-5903).

Across, all 7 festivals, as part of our longitudinal approach, we used a mixed-method approach. The project adopted an interpretivist approach, contextualizing data and findings to each case study and context and also valuing specifically interactive, cooperative, participative knowledge derived over time by dialogue with the research participants (Gasson Citation2004). For this reason, we conducted, in all case studies multiple focus groups with festival organizations to understand responses and changes over time. In total, we conducted 12 focus groups and 1 interview, ranging from 1 to 14 participants. Overall, 47 people took part, with 10 attending multiple groups. The participants were offered anonymity, however, most (including the ones mentioned in this paper) gave informed consent for their title and organization name to be used. All focus groups and the interview were conducted in English, recorded and transcribed for a verbatim account. The data were analysed using both discourse analysis and thematic analysis inductively (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This allowed reflection on the interview data, as well as the language used by respondents. Emerging themes were then identified across the 7 festivals. The principal themes identified overall were: the responses to COVID-19; Innovations/new approaches adopted; the role of technologies and the online environment; financial challenges; challenges to audience engagement; and learning and new knowledge developed through the pandemic.

For this paper, we focus only on two of the case studies: the NAF and the KKNK. Although they have quite different characteristics – both events decided to switch to an online mode in 2020 and 2021 and agreed to participate as research partners in the project. Furthermore, these were 2 largest mixed arts festivals in SA that went online and for which audience surveys were done both before the pandemic as well as part of this research. Links to the audience surveys were distributed via festival mailing lists, so convenience sampling was used. The mixed methods approach allowed the investigation of the impact of COVID-19, from the perspectives of both the festival management and audiences. Although research methods across the two festivals were similar, which allows for some comparison, focus group discussions and audience survey questions were tailored to each individual event.

Focus groups were held with both the NAF and KKNK management teams. The purpose of the focus groups was to explore how the festival management team had responded to the lockdown and determined what was possible in terms of adaptions in 2020 and 2021, support networks that they may have utilized, changes in business models, and relationships with artists and audiences. The NAF focus group discussion included the CEO, artistic director, communications manager, executive producer, Fringe director, technical director and Village Green (craft market) director. Seven members of the KKNK management team participated in the focus group including the artistic director, general manager, and five members of the board of directors. A separate focus group with the KKNK headline sponsor was also conducted. Focus group interviews with festival managers and sponsors were transcribed. Members of the research team then separately identified themes using manual content analysis, after which the identified themes were compared and consolidated.

Online audience surveys were run at both events. Although somewhat different, to take into account the differences between the two events (and the priorities of the management teams), both surveys asked about audience activities, experiences at, and opinions of, the online festival experience. Respondents were also asked to share some demographic information, such as home language, age, education level, and previous festival attendance.

In both cases, surveys were distributed via festival mailing lists so convenience sampling was used. The NAF audience survey was distributed via the National Arts Festival website, newsletters, and social media platforms. Responses were collected between July and September 2021, with a total of 139 responses received. The KKNK survey was distributed via festival mailing lists and social media, was available in both English and Afrikaans and was open from June to October 2021. In all, 192 responses were received.

At the NAF, Google Analytics data was also captured and analysed for the 2020 and 2021 editions of the festival. To compare the performance of the website and evaluate the visitor numbers and engagement, both editions of the festival were analysed over a 31-day window around the main festival activity dates: 25 June–25 July 2020, and 8 July–7 August 2021.

Given the nature of online surveys, it is not possible to say to what extent the samples of respondents represent the whole population of those who participated in the online editions of the NAF and the KKNK. One can say that the samples are reasonably large and provide some diversity in terms of demographics and previous festival attendance (). A significant difference between the two samples is that a much higher percentage of KKNK respondents spoke one home language (Afrikaans, who made up 94% of the sample, compared to 67% of English home language respondents at the NAF). Since the KKNK is an Afrikaans-language festival, this is to be expected. The NAF also seems to have attracted a younger demographic than the KKNK.

Table 2. Audience survey respondent characteristics at the NAF and KKNK.

While previous research at both festivals has shown that participants tend to be from higher-income and education groups, this trend has intensified in the online environment. For example, the 2019 study of the in-person NAF showed that 55% of respondents had at least one post-school diploma or degree (Snowball and Antrobus Citation2019), compared to 80% of respondents to the 2021 online survey.

An explanation for this change can almost certainly be found in the ‘digital divide’ in South Africa. The Statistics South Africa 2019 Household Income and Expenditure Survey showed that only 9% of South African households have access to fixed line internet at home, and that by far the majority of those who do have such access are in the highest (category 9 or 10) Living Standards MeasuresFootnote3 groups. This is the least expensive way of accessing the internet. The Income and Expenditure Survey (2019) showed that 54% of households can access the internet using a mobile device. However, it is only from LSM 6 that more than half of the households surveyed reported this kind of internet access, which is also more expensive. Challenges with the digital divide are thus a general concern of South African cultural events and festivals that elected to move online and are acknowledged as such by many festival organizers, as also found in a South African Cultural Observatory report (SACO Citation2021).

Another difference in the samples is that more NAF respondents were relatively new to the festival (which corresponds to the younger age group of respondents), while 70% of KKNK respondents had attended four or more previous editions of the festival.

Producing online e-eventscape: balancing cultural production and cultural experiences online

Innovating and moving online

In 2020, the NAF had 100 days in which to move the festival online to the virtual format after the lockdown was announced. The virtual National Arts Festival (marketed as the ‘vNAF’) was a fully online arts festival as they delivered a comprehensive Main and Fringe festival programme of theatre, dance, music, and workshops/webinars as well as a Jazz Festival. The craft market, usually known as the Village Green, was also taken into the online environment as the ‘Virtual Green’ where artists and crafters could display their works and link to their online stores. Every live element of the NAF was thus made virtual. The festival was extended beyond the usual 11 days (although this was still seen as the core event period). To keep the festival feeling, some shows were only available for a limited time while other recorded content and the Virtual Green was available for an extended period. The festival management team reflected on the challenges of shifting a large, mixed arts festival online in a short time, but also recognized that it provided much-needed opportunities for innovation:

We can quite happily push the reset button on the festival because there's nobody who will go, ‘but why aren't you doing it like you always did it?’ Because there is stuff that definitely stopped working a good 10 years ago and is still being done to serve as some sort of tradition … I think I called it a hard pruning. We can get back to the heart of the festival, and let it regrow itself as it needs to. (NAF Focus group discussion 2021)

The KKNK decided to cancel their live festival (23–29 March) just one week before it was due to start. ‘We spent most of early 2020 dealing with the aftermath of the unthinkable – a festival that can’t take place. It was a strange and uncertain time – nobody was prepared for a situation such as this' (KKNK Artistic Director, Focus Group Discussion 2021). One of the initial adaptation strategies considered was a limited outdoor live festival with small audiences and COVID-safety protocols in place, which would allow this highly destination-orientated event to continue to meet their obligations by contributing economically to the town of Oudtshoorn, though on a smaller scale, and bringing people together for social cohesion and connectivity purposes. However, in consultation with the festival board and sponsors, it was finally decided to take the festival online. The virtual 2020 KKNK offered a comprehensive programme including theatre, dance, music, a virtual art gallery, poetry and artist discussions. To account for restrictions on travel the KKNK introduced short films to their festival content along with several online community projects to keep people occupied, connected and to inspire creativity. The festival also established partnerships with international festivals and arts organizations to deliver additional festival content and exchange opportunities for artists. Continued COVID-19 lockdown restriction in 2021 resulted in another online festival, but this time spread over the whole year, rather than focused on the period of the live event. The theme was ‘KKNK Oraloor’, which translates as ‘KKNK everywhere’ as the festival attempted to reach audiences wherever they were, and content would be accessible ‘on television, on the silver screen and even in the palm of your hand’ (KKNK 2021).

Financial challenges to moving online and creating eventscapes

In the case of the NAF, festival tickets could be purchased for individual shows (for the Curated and Fringe programmes) or as a composite ‘Festival pass’ which gave access to all the Curated programme works. Access to online art galleries and the Virtual Green craft markets were free. Despite significant investment in upgrading the NAF website to enable it to act as a platform for the online event, as well as upskilling staff, the NAF website crashed on the first weekend of the 2020 festival, and even when the website was operational, some audience members reported struggling to navigate it. Competition in the online space is also fierce, and much online content is available for free, while most NAF content had to be paid for. Nevertheless, the National Arts Festival CEO explained,

We took a decision right early on, and we maintain this position, that content must be paid for. There's some free content, absolutely. But actually, professional artistic work needs to be paid for by paying customers. And we've still got to figure out exactly how to do that. (National Arts Festival CEO, Focus Group Discussion 2021)

KKNK festival organizers, supported and encouraged by their title sponsors, invested a great deal in upgrading their online platform. With a knowledge base in place after the 2020 online event, the KKNK aimed to extend their festival programme and continue to innovate with their content and the virtual platform. Perhaps more than the National Arts Festival, the location of the KKNK is central to the festival experience:

Oudtshoorn is synonymous with the KKNK and the festival itself. So again, that is a very important factor. And we had to take cognizance of that the whole time. (KKNK Board Member and Mayor of Oudtshoorn, Focus Group Discussion 2021)

Learning and evolving through the pandemic

In 2021, the NAF organizers started to plan for a hybrid festival eventscape that included small COVID-compliant live events and online content, marketed as the ‘National Arts Festival Experience’. The format was innovative as it attempted to reach all of the NAF’s audiences. Firstly, it catered to local live audiences by having events in the host town (Makhanda) with the ‘Makhanda Live’ programme. This would have involved the local community and provided some positive economic impact from festival tourism. Being a national festival, the NAF also has festival attendees from all over South Africa who travel to Makhanda to participate in the event. With travel restrictions and limits to the number of people who could gather in indoor spaces, the NAF intended to introduce live COVID-compliant festival sites in cities across South Africa, marketed as ‘Standard Bank [the title sponsor] Presents’. Lastly, for audiences who were further afield or who preferred to participate in the festival online, a virtual festival similar to the 2020 vNAF was available. This adaptation strategy indicates a different way of thinking about festivals in geographic space as ‘we’re not touring artists anymore, we’re touring audiences’ (National Arts Festival Artistic Director, Focus Group Discussion 2021).

However, on 15 June 2021, stricter lockdown measures, which did not allow for live audiences, were put in place. With just 10 days to go before the start of the 2021 NAF, the organizing team had to re-think their adaptation strategy to move the festival entirely online. With plans already in place for artists to travel to Makhanda to perform to live audiences, the NAF pivoted to live streaming and recording these live performances for the virtual festival. The impact of having to switch to a completely online event once everything had already been put in place for a live festival was described by the festival management team as devastating: ‘There was very little laughter or any joy in the weeks leading up to the festival in 2021. It was hell and actually far more difficult than 2020, in retrospect’ (National Arts Festival CEO, Focus Group Discussion 2021).

Nevertheless, the 2020 virtual festival had given the festival organizing team much experience to draw on. They emphasized that flexibility was key and enabled them to switch to a fully online festival at short notice when lockdown restrictions changed. Scalable adaptation strategies that could be changed to accommodate different COVID-regulations were necessary to ensure continuity and avoid cancellation.

Rather than curators of content, the NAF have begun to take on the role of co-creators in supporting artists to adapt to new festival formats and create online works. The NAF supported artists in taking their works online by running workshops and seminars for creatives on how to produce successful online shows, and by setting up film studios in a number of cities to enable artists, particularly emerging artists who were participating in the Fringe festival, to produce good quality works.

The silos of the different types of creative work also started to break down as people had to take on new roles and learn new skills to deal with the pandemic. For the festival organizing team this involved learning about how to operate online for their own working practices as well as running an online festival and helping artists and audiences to adapt, as they began to appreciate the importance of the online experience.

Understanding how to present ideas and communicate with audiences in a UX [user experience] manner, rather than you coming to experience [the festival live] where we have you all together in a little town has been quite difficult to wrap our heads around. (National Arts Festival Communications Manager, Focus Group Discussion 2021)

However, organizers also recognized the importance of maintaining the focus on providing high quality artistic offerings in the very competitive online environment, both in terms of technical quality, and new and exciting content. One of the most successful innovations of the 2020 and 2021 KKNK was the Virtual Gallery. It offered a virtual gallery online space, through which participants could move to different rooms and view the artwork, read information about each piece, or listen to the ‘audio walkabout’. More than 34,000 visitors ‘walked’ through the virtual gallery in 2020, and the curator won a national award, the KykNET Fiësta Award, for best achievement in the visual arts category.

The virtual experience and interactive offering were expanded in 2021. A virtual version of the host town, Oudtshoorn, was created through which participants could move, thus recreating a live festival experience. Festival-goers in the online space could enter the theatre to watch an online show, visit the Virtual Gallery, enter online social spaces to take part in conversations, or visit the sponsor (a large commercial banking house) for business conversations. The local community was also featured in the Virtual Absa Kuierkamer (visiting room) as they showcased their talents and discussed their town and region. This interactive aspect of the festival was intended to replicate some of the ‘vibe’ of the live festival, to encourage social connections and networking, and to keep the town of Oudtshoorn central to the online festival experience.

Consuming online e-eventscape: spending, participation and engagement

Attendance and spending

There was quite a range of activity types across the two festival platforms, especially for the main curated cultural offerings (Video on Demand and livestreamed shows at the NAF; Music and theatre productions at the KKNK) ().

Table 3. Audience participation at the NAF and KKNK.

Although not directly comparable because of their different formats, a higher proportion of KKNK respondents planned to participate in fine art activities (Virtual Gallery, 35%), than did NAF respondents (Exhibitions, 9%). Although neither festival reported e-commerce sales of arts and crafts as very successful, a greater proportion of KKNK respondents (43%) reported their participation in the craft market stalls than did NAF respondents (8%). While differences in participation can be attributed to other factors (such as differences in sample composition and festival format), results do seem to indicate that the focus of the KKNK festival organizers on enhancing the experiential aspect of their platform encouraged higher levels of participation.

Spending data for KKNK respondents is not available, but results from the NAF survey support the contention by the organizers that online content is difficult to monetize. The biggest group of respondents (31%) spent less than R100 (US$ 6)Footnote4 on Festival-related products and services. The next largest group spent between R100 and R200 (US$6 – $12) (17%). Overall, 64% of respondents spent less than R400 (US$ 24) at the Festival. This is markedly different from the live event, when in 2019, visitors from outside of Makhanda spent an average of R3800 (US$ 230) per person at the festival, while local residents spent an average of R1630 (US$ 99) per person. The largest spending categories have typically been on accommodation (for out-of-town visitors), followed by tickets (an average of R860 (US$ 52) per person for visitors and R540 (US$ 33) for local residents). Other spending categories for the live event in 2019 included food and drinks, shopping, and transport in and around town (Snowball and Antrobus Citation2019).

The spending data reflect a general challenge with online cultural events: monetizing the content is difficult. This may be because of falling household incomes during the pandemic, but the relatively high-income levels of most respondents cast doubt on this explanation. Other reasons for lower online spending could be the very high levels of competition and variety in online content, much of which is provided for free on platforms like YouTube, or at very low prices on OTT services like Netflix. It may also be that online content, which in many cases audiences are used to being able to access for free, is not perceived as having the same value as an in-person experience. The generally lower levels of online participation at the NAF in 2021 compared to 2020 may also be because of the ‘screen fatigue’ that many people (who also do much of their work online) experienced.

Google Analytics data was captured and analysed for the 2020 and 2021 editions of the NAF. To compare the performance of the website and evaluate the visitors, both editions of the festival were analysed over a 31-day window.

The ‘bounce rate’ is a calculation of the proportion of visitors that visit a single page on the site and do nothing on the page before leaving. The higher the bounce rate, the less engaged the visitors are with the site. The average bounce rate for NAF website visitors in 2020 was 30%, which is reasonably low, but in 2021, the bounce rate increased to 60%.

The fall in daily shows accessed between 2020 and 2021 can be explained by a number of possible factors, including online fatigue as the novelty of accessing cultural content online wore off, the social unrest experienced in South Africa at the time of the 2021 festival, and the Olympic Games (23 July to 8 August 2021). The 2020 and 2021 online festival content also had different formats, with the 2021 festival utilizing more livestreaming (compared to 2020, where there was more content ‘on demand’).

Even taking these differences into account, the 2020 NAF had many more online visitors than in 2021. On peak days (over weekends) the 2020 festival had more than 8000 individual visitors to the site, while peak days in 2021 saw only around 3000 visitors. For 2021, returning viewers remained constant across the duration of the festival, which means that the decline in viewership over the festival period was due to the fading of the new users as the festival progressed.

Audience ratings of festival activities

In order to gauge the experiences of audiences at the online festivals, respondents were asked to rate their experiences in terms of how much they enjoyed the various components of the festivals.

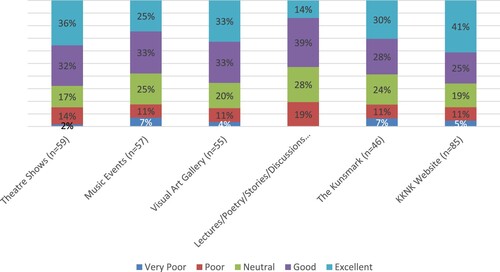

Respondents to the KKNK survey were asked to rate both their festival experiences, as well as the website, out of 5: A rating of 1 meant ‘very poor’; 2 meant ‘poor’; 3 meant ‘neutral’; 4 meant ‘good’ and 5 meant ‘excellent’ ().

The majority of the events were rated as ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. The website received the most ‘excellent’ ratings (41%), which may be explained by the KKNK investing additional resources into updating their website’s Graphical User Interface (GUI), as well as updating the back end, to enhance performance and end-user experience. Lectures/Poetry/Discussion events received the smallest proportion of ‘excellent’ ratings (14%). However, these events were also the least attended amongst the participants who completed the online survey.

68% of respondents rated the Theatre Shows as good or excellent; 66% rated the Visual Art Gallery as good or excellent; 58% rated Music Events and the Kunsmark as good or excellent. The highest average rating was obtained by the KKNK website (3.87), followed by theatre shows (3.86) and Visual Art Gallery (3.80). The events that received lower average ratings were the Kunsmark (3.65), music events (3.58) and lectures, poetry, stories and discussions (3.47). However, it should be noted that the number of responses from some of these event types were quite low (especially poetry, stories and discussions, which was rated by only 36 respondents) making the ratings data less reliable ().

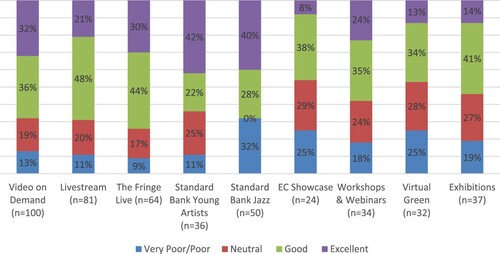

Similarly, for the NAF, the majority of ratings were in the ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ categories for most components. The categories with the highest proportion of excellent ratings were the Standard Bank Young Artists (42%), and Standard Bank Jazz (40%) components. The Eastern Cape Showcase received the smallest proportion of excellent ratings (8%) (although note the low number of ratings for this category); followed by the Virtual Green (13%) and Exhibitions (14%). 74% of respondents rated The Fringe as good or excellent; 69% rated Livestream content as good or excellent; and 68% of respondents rated Video on Demand as good or excellent. Workshops and Webinars did not have a very high number of responses (34), but of those who attended 24% rated them excellent, and another 35% as good ().

Table 4. Overall audience ratings of festival experiences.

The online festival experiences of components of both events were thus generally rated positively. The biggest differences between the festivals was the much higher average rating given to fine arts and online craft market components of the KKNK compared to the NAF. This could be related to the different characteristics of the live events and how these translated into the online eventscape, as well as the focus of the KKNK of creating on online eventscape experience, rather than using the website primarily as a platform through which to access content.

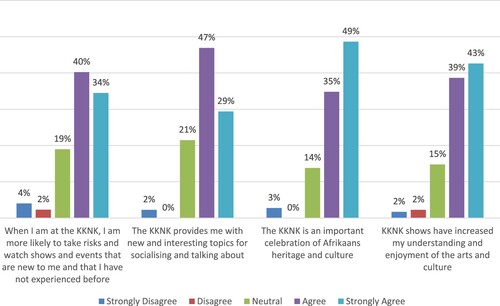

Building social and cultural capital and developing future audiences are important non-market official national goals of the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture, as well as being important aims of the KKNK. Based on a study of social capital at the Edinburgh Festivals (2011), the KKNK online survey also included questions related to audience development (taking risks and trying new things), building cultural capital (appreciation of Afrikaans heritage and enjoyment of arts and culture in general) and building social capital (). Survey respondents were asked to rate their response to various statements designed to measure to what extent the KKNK helped to achieve these goals from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

Response showed that 74% of KKNK respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they were more likely to take risks when consuming content at the KKNK, that is, 74% agree or strongly agreed that they would watch shows and attend events that they have not experienced before. As argued by Richards (Citation2019), the ‘novelty’ of festival offerings is an important part of overall visitor festival experience. However, Richards (Citation2019) also finds that cognitive engagement (defined as interpretation, learning and gaining knowledge) is an important determinant of festival visitor experience. 82% of the KKNK respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the KKNK helped them better understand and enjoy arts and culture within a South African context.

Affective engagement includes emotional reactions to an event, such as excitement, adventure and social interactions (Gues, Richards, and Toepoel Citation2015). While found by Richards (Citation2019) to be less important to overall experience, affective engagement is still important, perhaps even more so in an online environment during times of restricted social interaction. 76% of KKNK respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the online festival provided them with conversational topics, and 84% agreed that the KKNK is an important celebration of the Afrikaans heritage and culture in South Africa.

Despite the generally similar ratings for individual festival activities, in rating their overall festival experiences, a notably higher proportion of KKNK respondents chose the ‘excellent’ category, than NAF respondents. Both surveys explored the reasons for these ratings in greater depth – in particular, which aspects of the online festival experience respondents had enjoyed and not enjoyed.

At the NAF, 57% of respondents said that they preferred the live festival to the online edition. Nearly three-quarters of respondents said that they missed the ‘excitement and vibe of going to a live event’ (74%), and that they missed the experiential aspects ‘the sense of connection to performers and artists that you get at a live event’ (73%). Smaller (but substantial) proportions missed being able to ‘socialise and party with friends and fellow festival-goers’ (49%), being able to experience the food and drinks on offer (39%); and being able to travel to a new place (30%). Only 13% reported that they had struggled with the technology in accessing online content. Interestingly, results were similar between younger and older age groups except that, perhaps surprisingly, a larger percentage of older festinos reported that they missed the ‘excitement and vibe’ and the live event experience of being connected to performers and artists.

However, some aspects of the online editions of the NAF were enjoyed as well: 79% of respondents said that they enjoyed being able to participate in the Festival from home, without having to travel. Smaller proportions said that they appreciated having to pay less for tickets (32%); Being able to move quickly and easily between shows and events (29%); and not having to ‘dress up and go out to see shows and events’ (28%).

Despite the higher proportion of excellent ratings for the KKNK online event, 66% of the respondents preferred the live face-to-face event. Of the remaining 34% who either did not mind the virtual KKNK or liked certain aspects of it, 66% of these respondents enjoyed the flexibility of attending a virtual festival. 40% of these respondents liked that it was more affordable, that there was no travelling (28% of the respondents enjoyed this aspect), and that they had more time to access the content (35%) ().

Table 5. Audience preferences for live, online and hybrid formats.

Social aspects

Both festivals were aware of the lost social aspects of the online experience, and our visitor surveys explored this in several ways. The NAF survey asked if respondents had tried to simulate shared experience by using ‘watch parties’ (where a group of people arranged to watch online shows at the same time, even if not physically together). As shown in , a surprisingly large proportion of respondents did this (44% overall), especially younger (18–35-year-olds) festinos (57%). The survey also asked if respondents watched the festival online content mostly while alone, or with friends and family in the same location. 41% of respondents watched mostly with friends and family, a pattern which was again more prevalent amongst younger respondents (50%).

Table 6. Audience social engagement during online festival participation.

In the KKNK survey, respondents were asked whether having a ‘chat’ function that viewers could use to interact with each other during the shows would be appealing. A minority (29%) of respondents said they would be interested in this, and a larger proportion said they might find it appealing (38%), but a third of respondents were not interested (33%).

Discussion and concluding remarks

The National Arts Festival (NAF) and the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (KKNK) are two of the largest and oldest cultural festivals in South Africa. In response to the strict COVID-19 lockdown measures imposed, they both choose to shift to an online delivery mode in 2020 and 2021. Both festivals were fortunate to have stable relationships with long-time sponsors, and a certain amount of technical expertise, which put them in a better position to navigate the shift than many other cultural events. Nevertheless, there were significant challenges associated with the move, and they took somewhat different approaches to developing their e-eventscapes.

The paper overall highlights that while emphasis and research have been focused on understanding the production side of how festivals have reacted to COVID-19, it is important that our understanding of the changes that took place involve both the production and the consumption sides, including how audiences have perceived the changes to their festival experiences.

Both festivals in the study had strong identities and brands prior to their shift online. The NAF brand was focused on the quality and quantity of cultural offerings – what Pulh (Citation2022) refers to as ‘The Product’ experience-reinforcing lever. Although the location of the NAF has been quite an important part of its identity, the live festival is a winter event, with the primary marketing focus on the large programme of Main and Fringe offerings.

The KKNK live festival is an outdoor autumn event with free shows in the town centre and a strong community focus. The Afrikaans language framing puts the focus on local works and artists, and the location of the event in the Karoo town of Oudtshoorn has always been a central feature of the festival’s identity. As Pulh (Citation2022) explains it, this is the ‘Space–time Framework’ experience-reinforcing lever for the festival.

In the switch to online formats both festivals invested in their ‘e-eventscapes’ (Bosworth Citation2021), but in somewhat different ways. The NAF seems to have focused much more on content delivery rather than interactive user experience. This mirrors the live festival’s strong focus on artistic quality at a national and international level, and the number (intensity) of cultural offerings available over a shorter space of time.

The KKNK on the other hand, significantly changed their model in terms of timing (spreading festival offerings over the whole year). The online edition focused more on user experience, including more in the way of popular activities, and virtual online spaces, rather than a focus on internationally comparable artistic quality and very wide choice (quantity).

Both festivals received good overall rating from audience survey respondents, but perhaps not surprisingly, there was a more positive reaction to the KKNK e-eventscape where more attention had been paid to what Bosworth (2021) defines as ‘fundamental online infrastructure’ (aesthetic appeal and design; layout and functionality). The high bounce rate and lower visitor traffic at the 2021 NAF is an indication that more of a focus on e-eventscape experience levers could be a productive way forward. The more interactive approach adopted by the KKNK also seems to have translated into more participation in the e-commerce parts of the festival than at the NAF.

It is clear from the case studies, that COVID-19 put pressures on many festivals to transfer content online but that many have not had the time and capacity to carefully plan and consider their users’ experience.

Traditionally, in the case of in-person delivery, before COVID-19, festivals would have placed more focus on audiences and their interaction with the festival and its content. The move online has created a virtual barrier and a time–space lag between the performance and performers and the audiences. The audience, while part of online events, is not shaping the production, performance and experience as much as they do in live, in-person spaces. Three key challenges for festivals planning online or hybrid events have been identified: the need to create new forms of audience engagement/participation; the need to create a new e-eventscape, which may involve more active co-creation of content, alongside the usual commissioning of content and gatekeeper roles; and more broadly the need to invest in the human capital and technological infrastructure to enable the creation of the e-eventscape, beyond the traditional use of festival websites for branding and communication.

Festival managers acknowledged both the stressful nature and technical challenge of the sudden shift to online, as well as the opportunities for innovation that it offered. As found in the Bosworth (2021) study, the online festivals achieved important short-term goals for festival organizers related to business continuity, reaching audiences, and supporting artistic producers at a time of crisis. However, of particular concern in the South African context, the lack of access to the internet for most of the population constrained the festivals’ ability to reach audiences, particularly those in lower income and education groups. Monetizing festival content in order to achieve financial sustainability was also a challenge.

There are clear research implications emerging from the initial quantitative work done in the paper. More research and new frameworks need to be put in place to measure the complex dimension of e-eventscapes to allow festival managers but also artists to curate, understand and engage with audiences’ experiences online.

Managers of both events talked about the importance of the physical location of the festival for their identity and audience experience – a particularly difficult aspect to translate into the online environment. Even when discussing live festival experiences, Pulh (Citation2022) points to the importance of asserting a unique identity to avoid ‘McFestivalization’. The work done by both the NAF and KKNK management teams during the COVID-19 period to define and develop the core purpose of their event is thus likely to be extremely valuable in a post-pandemic environment in which hybrid approaches may become the norm: and this clear sense of identity will need to come through strongly in both online and in-person offerings in the future.

There are implications also for policy, especially, in considering whether future funding for festivals will also include finance to develop online content and e-eventscapes, beyond covering the cost of online content production. While some of these challenges have been faced in a moment of crisis, it is important that policy considers the way future funding could enable festivals to remain engaged with online audiences but also invest in their online presence as an experience rather than simple window-dressing. There is a lot of knowledge, expertise and experience that needs to be shared and maximized before festivals can move to their new hybrid futures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Using an average exchange rate for 2019 of R14.45 to the US$.

2 Using an average exchange rate for 2018 of R13.25 to the US$.

3 Living Standards Measures (LSMs) is an index based on household income, facilities and ownership of certain consumer goods. It was developed by the South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) and is used extensively for market segmentation. A full description of what it includes is available here: http://www.saarf.co.za/lsm/lsms.asp.

4 The average South African Rand (ZAR) to US Dollar exchange rate in 2020 was 16.47 which is what is used here to translate Rands into Dollar amounts.

References

- Arndt, C., R. Davies, S. Gabriel, L. Harris, K. Makrelov, B. Modise, S. Robinson, W. Simbanegavi, D. Van Seventer, and L. And Andreson. 2020. Impact of Covid-19 on the South African Economy: An Initial Analysis. Southern Africa – Towards Inclusive Economic Development (SA-TIED).

- Bachman, J., and J. Hull. 2022. “From the Theatre to the Living Room: Comparing Queer Film Festival Patrons and Outcomes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Annals of Leisure Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2022.2055585.

- Bosworth, G., B. Ardley, and S. Gerlach. 2021. “Innovation in agricultural and county shows: conceptualising the e-eventscape.” International Journal of Event and Festival Management 12 (4): 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-02-2021-0017

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using thematic analysis in psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, G., I. Lee, K. King, and R. Shipway. 2015. “Eventscapes and the Creation of Event Legacies.” Annals of Leisure Research 18 (4): 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2015.1068187.

- Carneiro, M., C. Eusebio, A. Caldeira, and A. Santos. 2019. “The Influence of Eventscape on Emotions, Satisfaction and Loyalty: The Case of Re-Enactment Events.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 82:112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.025.

- Chapple, M., A. Anisimovich, J. Worsley, M. Watkins, J. Billington, and E. Balabanova. 2023. “Come Together: The Importance of Arts and Cultural Engagement within the Liverpool City Region Throughout the COVID-19 Lockdown Periods.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:1011771. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1011771.

- Comunian, R., F. Drummond, J. Gross, J. Snowball, and D. Tarentaal. 2023. Future Festivals South Africa: Lessons from the Age of Covid-19, a Policy Report. https://doi.org/10.18742/pub01-096.

- Davies, K. 2020. “Festivals Post Covid-19.” Leisure Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1774000.

- De Valck, M. 2021. Vulnerabilities and Resiliency in the Film Ecosystem: Notes on Approaching Film Festivals in Pandemic Times. Configurations of Film Series. Pandemic Media. https://doi.org/10.14619/0085.

- Dholakia, A. 2020. “Virtual Event Sponsorship: How to Price & Structure Sponsorship Deals for Online Events?” https://blog.hubilo.com/how-to-structure-a-virtual-event-sponsorship/.

- Drummond, F. 2021. Update on Mapping the Impact of COVID-19 on South Africa Festival.” Blog Published 29 April 2021 in Future Festival South Africa. Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.future-festivals.org/blog/update-on-mapping-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-south-african-festivals.

- Ellis, G., P. Freeman, T. Jamal, and J. Jiang. 2019. “A Theory of Structured Experience.” Annals of Leisure Research 22 (1): 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2017.1312468.

- Estanyol, E. 2022. “Traditional Festivals and COVID-19: Event Management and Digitalization in Times of Physical Distancing.” Event Management 26 (3): 647–659. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599521X16288665119305.

- Fernandes, M. 2020. “A Guide to Virtual Event Sponsorships Part I: Deals & Packages.” https://helloendless.com/virtual-event-sponsorships/.

- Gasson, S. 2004. “Rigor in Grounded Theory Research: An Interpretive Perspective on Generating Theory from Qualitative Field Studies.” In The Handbook of Information Systems Research, edited by Whitman M. and Woszczynski A., 79–102. Idea Group Publishing. ISBN13: 9781591401445

- George, J. 2015. “Examining the Cultural Value of Festivals: Considerations of Creative Destruction and Creative Enhancement Withing the Rural Environment.” International Journal of Event and Festival Management 6 (2): 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-01-2015-0002.

- Gues, S., G. Richards, and V. Toepoel. 2015. “Conceptualisation and Operationalisation of Event and Festival Experiences: Creation of an Event Experience Scale.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2015.1101933.

- Hanzlík, J., and E. Mazierska. 2022. “Eastern European Film Festivals: Streaming Through the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 13 (1): 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2021.1964218.

- Hubbard, D. 2020. Event Sponsorship: The 2021 Guide. https://blog.bizzabo.com/event-sponsorship.

- Jess-Cooke, C. 2020. “Democratising Literature Post-COVID-19.” The Bookseller, March 31. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/213436/1/213436.pdf.

- Layman, M. 2020. Virtual Event Sponsorship. https://www.cvent.com/en/blog/events/virtual-event-sponsorship.

- Lee, D., W. Baker, and N. Haywood. 2020. “Coronavirus, the Cultural Catalyst.” https://www.google.com/url?sa = t&rct = j&q = &esrc = s&source = web&cd = &cad = rja&uact = 8&ved = 2ahUKEwiZ7bSiu8fpAhVRxUIHUl5AGwQFjAAegQIARAB&url = https%3A%2F%2Fwww.researchgate.net%2Fpublication%2F340248507_Coronavirus_the_cultural_catalyst&usg = AOvVaw3S3nAzCWmfLUzCJyGMck1V.

- Mair, S. 2020. “What Will the World Look Like After Coronavirus? Four Possible Futures.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/what-will-the-world-be-like-after-coronavirus-four-possible-futures-134085?utm_medium = email&utm_campaign = Latest.

- Mello, B. 2020. 3 Ways to Build Your Community with Virtual Events. https://marketing.sfgate.com/blog/ways-to-build-your-community-with-virtual-events.

- Mulet, B. 2021. New South Wales Snapshot-Audience Outlook Monitor. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/4355626/november-2021/5152059/.

- National Arts Festival. 2021. The National Arts Festival. https://nationalartsfestival.co.za/.

- Nobre, G. 2020. Creative Economy and COVID-19: Technology, Automation, and the New Economy. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guilherme_Nobre/publication/341189890_Covid-19_and_the_Creative_Economy_surveys_aids_tools_and_a_bit_of_hope/links/5eb5cf0f299bf1287f77d6dd/Covid-19-and-the-Creative-Economy-surveys-aids-tools-and-a-bit-of-hope.pdf.

- Packer, J., and R. Ballantyne. 2016. “Conceptualizing the Visitor Experience: A Review of Literature and Development of a Multifaceted Model.” Visitor Studies 19: 128–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2016.1144023

- Pulh, M. 2022. “Differentiation Through the Over-Experientialization of Cultural Offers: The Case of Contemporary Music Festivals.” International Journal of Arts Management 24 (2): 62–75.

- Richards, G. 2019. “Measuring the Dimensions of Event Experiences: Applying the Event Experience Scale to Cultural Events.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 12 (3): 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2019.1701800.

- SACO . 2021. “The Challenges of Pivoting to Digital: The COVID-19 shut down and cultural festivals and event.” South African Cultural Observatory. Online. https://www.southafricanculturalobservatory.org.za/

- SACO (South African Cultural Observatory). 2016. The Impact of the 2016 National Arts Festival. Port Elizabeth: South African Cultural Observatory.

- Sargent, A. 2021. Covid-19 and the Global Cultural and Creative Sector. What Have We Learned. https://www.culturehive.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Covid-19-and-the-Cultural-and-creative-sector-II-FINAL-UPDATED-SEP2022.pdf.

- Snowball, J., and G. Antrobus. 2018. The Socioeconomic Impact of the 2018 Klein Karoo Nationale Kunstefees (KKNK): 2018. Oudtshoorn: Commissioned by the KKNK.

- Snowball, J., and G. Antrobus. 2019. The Social, Cultural and Economic Impact of the 2019 National Arts Festival. Commissioned by the National Arts Festival.

- Snowball, J., and A. Gouws. 2022. “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Cultural and Creative Industries: Determinants of Vulnerability and Estimated Recovery Times.” Cultural Trends. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2022.2073198.

- Stats, S. A. 2019. “General Household Survey.” Statistics South Africa. Republic of South Africa. Online. https://www.statssa.gov.za/

- Valck, M. D., and A. Damiens. 2020. “Film Festivals and the First Wave of COVID-19: Challenges, Opportunities, and Reflections on Festivals’ Relations to Crises.” NECSUS_European Journal of Media Studies 9 (2): 299–302.

- Yin, R. 2003. “Designing Case Studies.” In Qualitative Research Methods., edited by Maruster L. and Gijsenberg M., 359–400. London: Sage.