ABSTRACT

In this paper, we explore how immersion in nature implicitly relates to consumerism and how our emotional engagement with nature is manifested as power dynamics in our drive to connect with nature. Utilizing insights from Aristotelian ethics (specifically eudaimonic wellbeing), mindfulness, and aesthetics, we propose a tripartite framework of moods associated with ‘friluftsliv’ in a Norwegian context, arguing that engagement with nature harbours a concealed ecological fallacy. Identifying the means by which we can deepen and enrich our emotional awareness of nature – especially by pinpointing emotions that spur people to act in harmony with the environment – holds immense potential for the development of sustainable lifestyles. We categorize these conceptual moods as the hedonic mood, the eudaimonic mood, and the mood of self-transcendence. Addressing the Western, individualistic perspective on the human-nature relationship, we suggest that leisure and recreational interactions with nature are conducive to a revitalization of the concept of ‘friluftsliv’.

Introduction

During the recent years, the Nordic notion of ‘friluftsliv’ has got increased attention as a cultural term relevant to understand human bonding to nature. One example is the introduction of the term ‘friluftsliv response’ which is a term indicating a positive response of connection to place (Castro et al. Citation2022). Surely, there could be some strong connections between engaging in friluftsliv and connection to place. Connecting with nature relates to better quality of life (Capaldi et al. Citation2015; Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2011; Pritchard et al. Citation2020), and emotional connection to nature moreover is associated with pro-environmental behaviour (Anderson and Krettenauer Citation2021; Pirchio et al. Citation2021). However, connecting emotional experience to pro-environmental behaviour is complex (Anderson and Krettenauer Citation2021), undertheorized, and understudied, according to a summary from van Heel, van den Born, and Aarts (Citation2024). Merely exposure to nature does not build these associations per se. Neither ‘loving nature’ have clear implications for a positive eco-social change (Crowley Citation2013). Hence, more conceptual understanding of how to relate emotional experiences in nature to pro-environmental behaviour is needed. This article develops a stronger theoretical understanding of the role of emotions during typical friluftsliv approaches and identifies different emotional dynamics that are associated with environmental choices. We identify these hidden emotional influences – which often are unconscious – as psychological power dynamics. Emotional responses regulate our liking and wanting (Berridge and Robinson Citation2016), and these dynamics are relevant for our general consumer behaviour and interest in developing sustainable practices. In our everyday life, our emotional distance to nature versus emotional connection to nature is challenged when selecting choices for living. Hence, our emotional tone, or mood, is relevant for identifying our purposes and willingness to include sustainability or consumption in our desires for engagement with and in nature.

A critical perspective of friluftsliv and the development of moral emotions

Researchers outside the Nordic countries (Breunig Citation2022; Farkić, Filep, and Taylor Citation2020) discuss friluftsliv as an aspect of ‘slow experience’. As a cultural practice, friluftsliv is related to wellbeing and felicity through intrinsic values derived from the natural environment. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this concept emerged as a means of combating wintertime and pandemic blues.Footnote1 While such ideas romanticize the idea of Norwegian culture as a deep way to feel connected to nature, there are good reasons to problematize ways of engaging in nature in light of the influence of western consumerism and individualism.

Originally, friluftsliv referred to a way of being in nature in a mindful way, as an escape from daily life that involved valued nature experiences (Breivik Citation2020; Gelter Citation2000; Citation2010; Henderson and Vikander Citation2007; Hofmann et al. Citation2018). Summarizing characteristics found in the Scandinavian friluftsliv literature, Bachman (Citation2010) proposed that the features of friluftsliv involve a wide range of dimensions: experiences of nature; resistance to competition; health; cultural perspectives on the landscape; environmental awareness; simplicity; folksiness; free and uncivilized nature; fostering of character; resistance towards consumption and commercialism; ecological perspectives; and mindfulness. The original notion of friluftsliv is ambiguous, at least in relation to the normative aspects of nature connectedness, mindfulness, and sustainability.

Therefore, friluftsliv could be both part of the main problem of consumerism, as well as a solution depending on chosen approach. For example, there is a significant and meaningful relation between friluftsliv and environmental connectedness (Beery Citation2013). In contrary, awareness and the articulation of how friluftsliv and environmental consciousness are tied together is found to be missing among mountain hikers interviewed in a Norwegian national park (Høyem Citation2008). Friluftsliv is moreover the number one leisure activity with the highest ecological footprint in Norway, caused by travelling, accommodation, and material needs (Aall et al. Citation2011). In a time where general friluftsliv discourses are influenced by sportification (Sjödin Citation2024), and higher education in outdoor studies are discussing code of conducts for professionalism (Polley Citation2021), our emotional connection to nature when practicing friluftsliv is somewhat taken for granted. At least, it has not been properly examined within modern friluftsliv.

To enable the development of a stronger theoretical understanding of the role of emotions during typical friluftsliv approaches we are using an interdisciplinary approach (Moran Citation2002) with resources from philosophy (second author), psychology (first and third author), and outdoor studies (first author). This collaboration between psychologists as measurement experts and philosophers as conceptual experts (Intelisano, Krasko, and Luhmann Citation2020) not only enables an interdisciplinary approach that takes the role of emotions and aesthetic experiences seriously, but also allows an identification of similarities between friluftsliv and mindfulness as a psychological process. Through such an interdisciplinary approach we offer a novel perspective on how different emotional experiences provide a (subconscious) template from which the phenomenon of friluftsliv is approached, experienced, and understood.

To explore the potential links between varied emotional approaches to friluftsliv and environmental choices, we first explore how attraction to nature can exhibit differing emotional valences associated with love and attraction to nature. Subsequently, by affirming the role of emotions as a crucial element of forming bonds with nature, we delve deeper into the intricate interplay of psychological liking and wanting, along with the role of emotional awareness, ending up with the delineation of three distinct moods relevant for approaching friluftsliv. We discuss the evolution of moral emotions – as they relate to pro-environmental intentions – within the framework of a psychological power perspective. Finally, we discuss the implication for friluftsliv practices.

Love of nature, sustainability, and ecological fallacy

Our understanding of sustainability includes the full and simultaneous integration of social, environmental, and economical solutions for living. We consider the UN sustainability development goals (https://sdgs.un.org/goals) as milestones within separate areas of society, where a sustainable society is realized only when collaboration of all sustainability goals is taken into account. This points to regenerative practices, circle economy, and personal transformation in how to live good lives that include a perspective of sustainability. What can friluftsliv offer in this transformation process? Friluftsliv pedagogy have stressed the value of facilitating for nature experiences when bringing awareness to our dependency on the natural environment (Bachman Citation2010 Wold Citation2023;). However, approaching nature in terms of experiences and emotions is less developed. For example, loving nature can be seen as a romantic project disconnected from real life problems unless we take a holistic perspective of eco-social solutions (Crowley Citation2013). How our emotional connection to nature relates to consumption is thus guided by dynamics of power, such as romantic versus hands-on approaches to living. Moreover, other hidden emotional power dynamics can be found in more masculine ideas, such as loving mountains and alpinism as a particular way of loving nature (Crowley Citation2013; Pedersen Gurholt Citation2008).

Through investigating different emotional responses, we explore how our engagement with nature implies consumer perspectives of ‘liking’ and ‘wanting’ (Berridge and Robinson Citation2016), and introduce perspectives that could challenge these dynamics. This ‘wanting’ could take many forms. We already know that the distribution of societal participation in friluftsliv is skewed. The most educated people in Norway and those with highest income also benefit the most from having access to green spaces in close proximity to their homes. In particular, this was seen during the COVID19 pandemic (Grau-Ruis, Løvoll, and Dyrdal Citation2024). Norwegian friluftsliv is also skewed by Sami perspectives being systematically suppressed (Skille, Pedersen, and Skille Citation2023). A dialogue regarding ways of understanding how to live more sustainably could be enriched by indigenous perspectives of complex nature understandings. Moreover, other critical aspects such as gender issues and narratives of heroic males (Pedersen Gurholt Citation2008), have also influenced the way we culturally think about friluftsliv.

The consumer culture theory perspective is fundamentally concerned with cultural meanings, influences and dynamics that shape experiences and identities in everyday life (Arnould and Thompson Citation2005). When we immerse ourselves in nature for wellbeing purposes, we may not consider ourselves as consumers. Yet, our constant seeking of positive experiences to feel satisfied is identified as an ongoing treadmill process, as we tend to adapt to the new levels of pleasure relatively quickly. This is called the ‘hedonic treadmill’ or hedonic adaptation (Brickman and Campbell Citation1971). Such process of constantly seeking what is new or better to sustain high levels of pleasure or happiness can be driving consumer behaviour, leading to acquisition of whatever is seen as ‘more’ and ‘better’ (equipment, clothes, places, experiences). This is an example of how psychological power dynamics drives our attraction to nature, which leads to consumer behaviour and unsustainability. Another example is the motivational dynamic behind collecting points through digital registering of check-in places in nature. Technology has become increasingly popular in facilitating for health promotion in nature. In a Norwegian sample, frequent users of a mobile app (n = 22) reported ambivalent feelings about what was driving their interest in nature, hiking itself or collecting points. This ambivalence relates to ‘wanting’, which is connected to obsessivity and is challenging our autonomy. In this case, the role of nature itself became secondary in the total experience (Vikene et al. Citation2023).

Immersion, power dynamics, and connectedness to nature

The steady emergence of urbanized and industrialized cities results in a lack of closeness to nature and simultaneously an increased interest in nature immersion. Mountains and climbing have been seen as inhabiting transformative possibilities for the awakening of environmentalism in this context (Ord Citation2018). Yet, the transformative intrinsic quality of awe and wonder that is reported in the vertical and altitude mountain elements build on vague conceptualizations of awe and wonder resulting from alpinism and can be considered rather speculative. Do we need mountains to engage in nature immersion?

When engaging in friluftsliv, some feelings seem to be in the foreground of an experience, while others are less apparent or unconscious. While positive emotions are important for our wellbeing in many ways, more subtle or complex emotions could be harder to identify, especially while doing an activity that needs our full attention. A pioneer in the scientific investigation of ‘awe’, Dacher Keltner, states that ‘when we experience awe, regions in the brain that are associative with the excesses of the ego, including self-criticism, anxiety, and even depression, quiet down’ (Keltner Citation2023, 36). This way of being is influenced by how we pay attention: The more we practice, the richer it gets (106). Hence, there are huge differences in our emotional engagement in nature and in our willingness to act with pro-environmental behaviour, as there are many motives for engaging in nature.

The Norwegian official definition of friluftsliv (St.meld.Citation18 [Citation2015] Citation2016), include the term ‘nature experiences’, yet a common understanding of what this experience involves, is lacking. Nevertheless, connecting with nature is implicit in the Norwegian understanding of health and wellbeing. Engaging in nature can invoke positive emotions related to many aspects of living, such as appreciating moments of beauty or fulfilling a goal. Immersion typically relates to flow experiences of being fully engaged in activity (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1975; Citation1990), but could also denote the opposite – simply being mindfully present, in the body, in the present moment (Kabat-Zinn Citation2015). On the axis from doing nothing to being fully engaged in activity, aesthetical nature experiences invite immersion, which relate to different aspects of attention like life satisfaction or awe and wonder (Keltner Citation2023). Research also shows a significant association between mindfulness and connectedness to nature (Howell et al. Citation2011), however this association seems dependent on how mindfulness is conceptualized and what aspects of mindfulness are measured (Schutte and Malouff Citation2018). Connectedness to nature seems related to mindfulness as a trait, a natural tendency to feel connected to nature, rather than a characteristic of the experience of nature itself. Immersion thus has many directions depending on the intention of being in nature, like the attention brought to one’s experiences, or the attitude adopted in meeting the natural environment. Furthermore, the focus of attention, whether it is on the mind itself or on the direct experiences of nature, invites different perspectives and kinds of experiences when being in natural environments.

Moods affecting our approach to friluftsliv

Human attention is like ‘a stream of thoughts’ (James Citation1890), including subtle mental processes affecting what we attend to. Following James, we might experience connection to nature during friluftsliv if we consciously choose to attend to nature. Alternatively, we might be attending to other aspects of the outdoor experience or of life. In our analysis, the understanding of different moods affecting how individuals approach friluftsliv is helpful for understanding psychological variations and their implications for ethical awareness.

The term ‘mood’ is chosen to illustrate how different emotions arise when moving in natural environments and how these moods can influence how we approach friluftsliv and our experience of being in nature. Following Oatley (Citation1992), moods refer to emotional states that last for more than a few hours. As they relate to the attention and intention brought to friluftsliv experiences, they affect the planning for, thinking of, and participating in friluftsliv. Moods can oscillate and include both conscious and unconscious processes. An investigation of emotional valences during different experiences illuminates the subtle transitions between emotions and cognitions and actualizes the possible mindful and ethical relevance of this approach, providing insights into how we think of and present friluftsliv for ourselves and to others. Our approach recognizes the centrality of emotions as emerging prior to our thinking (Damasio Citation1999; Nussbaum Citation2003; Tomkins Citation1970). Without emotions, we lack the mental representations required for concepts and words. As postulated by Oatley (Citation1992, 19f), emotions are the mental states of readiness for action – or change for readiness – building on evaluations that does not need to be consciously made. When we are engaged wholeheartedly in something, either alone or with someone else, we tend to experience a particular mental tone (Oatley Citation1992, 348). Consequently, because of this mental tone, our minds are semantically filled with what we are doing, creating what we refer to as a mood. According to the communicative emotion perspective (Oatley Citation1992), emotions can help us discover our inner purpose through attention and thinking, informing our ethical thinking in a back-and-forth process of recognizing our emotions. Being wholeheartedly emotionally connected with what we do resembles Spinoza’s writings on ‘perfectio’ and ‘potentia’. ‘Perfectio’ is what makes us more integrated and complete and builds our power of action. ‘Potentia’ enable us to act in correspondence with the deepest premises, goals, and purposes in our lives (Næss Citation1999, 111).

With positive psychology and the scientific study of the stability and change of positive emotions (Vittersø Citation2016), hedonic (e.g. pleasure, happiness, and satisfaction) and eudaimonic (e.g. interest, engagement, enthusiasm, and inspiration) emotions are associated with different conceptualizations of wellbeing (Vittersø Citation2016). These different groups of positive emotions are informed by different philosophies of the good life. For example, pleasure is important for satisfaction with one’s life, while interest assumes significance for personal growth (Vittersø and Søholt Citation2011). In general, positive emotions are important because they broaden our mindsets and build resources for future actions (Fredrickson Citation2004). All positive emotions are imbued with this potential for flourishing. In psychological parlance, hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing are identified as distinct but related approaches to the good life (Ryff and Singer Citation2008; Steger Citation2016; Vittersø Citation2016).

By exploring emotions in the context of the different moods of friluftsliv, a clarification of the relationship between cognition and emotions is needed. We recognize emotions and cognition as strongly intertwined. Following Arne Næss (Citation1999), emotions belong to a deeper rationality together with cognition. Inspired by Spinoza, he argues for ratio as the inner voice of reason, expressing that something is not rational if it is not in accordance with the deepest premises, goals, and purposes in our lives (Næss Citation1999, 43). Hence, by understanding emotions as an important aspect of our rationality, ratio also points out a direction to move with ethical implications. A hypothesized representation of the three moods is given in . These moods will be further elaborated and discussed.

Three different moods of immersive nature experiences

Based on our analysis, the difference between three distinct moods of nature immersion is suitable for the discussion of power dynamics from consumer theory and psychology.

Hedonic mood: positive emotions

A key attribute of a hedonic mood is to feel relaxed and filled with pleasure and satisfaction, which are related to the concept of hedonic wellbeing (Waterman, Schwartz, and Conti Citation2008) and life satisfaction (Vittersø and Søholt Citation2011). Negative emotions are managed, and attention is shifted towards positive experiences, such as the smell of sunburned mosses, the taste of sweet blueberry, and the sound of waves on the shore, which can fill us with pleasure. Seeking a daily dose of nature is a beneficial strategy for wellbeing.

A common understanding of the value of immersion in nature comes from the biophilia hypothesis, which suggests that to feel healthy, humans need nature (Kellert and Wilson Citation1993). The predictive value of recreation in nature on human wellbeing is remarkable (Gladwell et al. Citation2013; Passmore and Howell Citation2014; Wolsko and Lindberg Citation2013), and nature can maintain human wellbeing through reducing stress and providing positive health (Laumann Citation2004). A lack of a natural environment in daily life might lead to increased stress and lifestyle diseases. Hence, nature has recreational and restoring qualities not only through the positive effects of exercise and physical activity, but also in and of itself (Kotera, Richardson, and Sheffield Citation2022).

The value of landscape qualities for recreation has elicited increased international attention over the past few years, including active interpretations of the value of context in subjective experiences (Knez and Eliasson Citation2017). Facilitation of parks and hiking trails in areas where people live is a part of this approach. The heavy development of cabins or second homes in the Norwegian mountains and along the coastline, with 422,827 cabins for the population of 5.2 million citizens in Norway in 2016 (Statistics Norway Citation2021), can be seen as a wish to change environments for recreational purposes and adopt a lifestyle closer to nature (Garvey Citation2008). Second homes are often markers of freedom, happiness, identity, and the wish of living close to nature, enabling a combination of urban and rural living. However, this comes at the cost of increased use of transportation and material resources, energy consumption, and the loss of non-facilitated natural environments. Building cabins with high comfort is increasing, questioning the romantic notion of Norwegians as going ‘back to nature’ (Xue et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, friluftsliv could have high economic costs resulting in a high ecological impact, placing friluftsliv in a leading position for the consumption of outdoor clothing, equipment (e.g. skiis, bicycles, backpacks), cabins, leisure boating, and leisure transportation (Aall et al. Citation2011). Within the hedonic mood, the distinction between consumption for pleasure and a mindful presence, including paying attention to the natural environment as it is through the senses, makes a difference for emotional awareness.

‘Pleasure’ in this mood needs to be further analysed. According to neuropsychologists, emotional processes of hedonic liking or disliking can occur without conscious awareness (Skov Citation2023). All sensory liking systems include three basic functional components: a sensory system, an evaluative system that represent the hedonic value, and a decision-making system. However, the evaluative judgement is not limited to sensory stimulus information alone. According to Skov, multiple factors matter in this judgement, such as psychological states, motivational needs, prior experiences with the stimulus, cognitive knowledge, and the weighing of goals and requirements associated with the act (Citation2023, 51). This means that how we attend to our hedonic feelings in nature matter. Put differently, ‘pleasure’ and ‘pleasure’ are not the same thing. There are ecological power differences in how we emotionally engage in ‘pleasure’, as this could also be an unconscious process of seeking pleasant feelings as consumption. Learning complex ways of feeling pleasure in nature is especially developed within the Japanese framing of being mindfully present to the atmosphere of the forest, known as the Shinrin Yoku practice (Kotera, Richardson, and Sheffield Citation2022). This practice is itself inspired by Shinto and Buddhism with an animist understanding of nature, seeing human beings as a fundamental part of nature.

Lifting the ‘slow’ aspect of friluftsliv through attention to presence in natural surroundings could provide the basis from which to build an environmental and wellbeing sustainable lifestyle. To feel positive emotions is partly a skill that can be learned, and is not coming from a stimulus perspective, but a way to pay attention to sensory experiences. Maximizing positive emotions is a way of understanding happiness which point to western ideas of happiness (Krys et al. Citation2024). While maximizing happiness can be seen in leisure culture and comfort seeking by privileged middle-class consumers, there could be resources in Norwegian culture that point to other interpretations of happiness, such as simple living (Næss Citation1999). Inspiration for simple living can be found in the idea of gathering around a campfire, sharing food and histories with friends or family. Pleasure as a slow and mindful way of being with self-conscious ecological awareness could carry larger potential for sustainability than pleasure as based on seeking comfort.

Eudaimonic mood: self-fulfilment

This second mood can be described as ‘nature as a playground’, with the outdoor environment calling for a wide range of adventures, from mountaineering, skiing, and climbing to wilderness camping or sailing. The popularity of extreme sports, such as steep mountain skiing, kiting, terrain biking, and air sports, has increased over the past decades. Many of these nature-based activities have a negative global impact such as increased air travel to arrive at popular destinations. In Norway, the landscape invites a broad range of nature-based activities, including activities involving the sea and the long seashore, the steep mountains rising from the fjords, and the rich alpine areas in the southern and northern part. Other activities use the large areas of wilderness the country also offers, and for these reasons, Norway has been identified as ‘the northern playground’ by British adventurers (Slingsby Citation1904/2022).

The playground mood is motivated by a wish to realize a goal, such as reaching a peak, walking a distance, skiing a certain slope, or climbing a specific route. This mood is rooted in the eudaimonic wellbeing approach where wellbeing stems from seeking purpose, value, meaning, and personal growth. Eudaimonic experiences involve developing and using skills, often challenging personal limits, and assessing and managing risk. Experiencing negative emotions, such as being cold, frightened, and anxious, are likely, and when overcome, new or expert skills can result, which are often rewarded with positive emotions. These experiences (of hiking mountains for summits, reaching peaks or altitude metres, or skiing steep slopes) are aspects of a project-oriented approach to nature, which is also related to the travelling and tourism industries and the shaping of guide professionalism.

The eudaimonic mood often involve flow experiences, typically described as moments of being fully engaged in something, totally concentrated and absorbed during some kind of activity (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1975; Citation1990). Experiences of time can be changed, and there is a loss of self-consciousness. In those moments, people can find themselves to be extremely productive, creative, or motivated, and functioning at their very best. After experiencing flow, there is an emotional boost that can last from seconds to maybe half an hour (Ashby, Isen, and Turken Citation1999), hence these experiences are strongly positive and rewarding. Often, this is how friluftsliv is presented and communicated, appealing to all kinds of people who like to challenge themselves by seeking adventure. Inspiration for seeking the ‘highest, largest, or steepest’ can be encouraged by historic polar heroes and can also be discussed as facets of masculinity (Pedersen Gurholt Citation2008).

There is a risk of increased consumption resulting from the hedonic treadmill effects, and the maximation of happiness-process, where increasingly more is needed to become satisfied. Liking an activity can over time, and at a certain tipping point, develop into dynamics of ‘wanting’ (Berridge and Robinson Citation2016), which is closely related to addiction. The hedonic reward of flow experiences and goal achievements can result in a motivational drive for new experiences: hence wanting new experiences as soon as possible. This eudaimonic mood can thus lead to both healthy and unhealthy wellbeing, and to increased environmental consumption. As positive experiences affect our wellbeing, it can lead to either (1) harmonized passion or (2) obsessive passion (Vallerand Citation2010), with the latter characterized by addiction and consumption. While emotions of interest and engagement are important for doing our favourite activities in nature, we might be insensitive to what the invitations from nature really are (Stockwell Citation2023). These can be related to weather, wildlife, exposure, etc., favouring an individual interest in self-fulfilment over an ecological perspective. Resultingly, nature engagement can both promote and hamper wellbeing and ecological considerations.

Mood of self-transcendence: seeking aesthetic qualities in nature

Expanding on the liking/wanting distinction, the third conceptual mood includes theories of value appreciation, which has a clear aesthetical component. As for the two other moods, there is no direct link between approaching friluftsliv with positive emotions and pro-environmental behaviour. Attributes of the feelings we develop in relation to nature are essential for understanding the link to pro-environmental attitudes, which include complex associations. From the field of neuro-aesthetics, ‘liking’ has very complex associations with wellbeing and learning. For example, it is a myth that dopamine relates to pleasure (Stark, Berridge, and Kringelbavh Citation2023). Rather, dynamics of wanting relates to dopamine, while wellbeing and learning could also be unrelated to pleasure. Building on the Aristotle distinction between hedonia and eudaimonia, Stark et al. suggest investigating a brain state with potential for human flourishing that is best described by ‘meaningful pleasure’ (Citation2023, 64). This empirical field is to be developed in the future. However, the deep connection between meaningful pleasure and value appreciation can be theoretically studied within aesthetical judgements. Also, complex moral emotions, such as disgust, shame, pride, anger, guilt, compassion, and gratitude, relates to intentions of behaviour (Walsh Citation2021). A relevant question is whether we consider such complex emotions as self-aware or not, and if we pay attention to such emotions. According to Jonathan Haidt (Citation2003), the higher the emotionality of a moral agent, the more likely the agent is to act morally. Such emotions go beyond the initial liking/wanting approach and refers to the person’s ability to develop emotional awareness. Emotional development could then be a lifelong process of creating our human capabilities to become better human beings (Nussbaum Citation2011).

People seek nature for inspiration in their life, in art, and in living, which can add a spiritual dimension. In this way, nature offers more than recreation or activities and skills, and people who are not interested in physical exercise are still finding nature as a deeply inspirational source (Davis and Gatersleben Citation2013). Cultural ideas of simple nature living as inspiring a flourishing life have been born from the romantic movement and its rich nature writing tradition (Branch Citation2004). For identifying the mood of self-transcendence, it is important to address the role of aesthetic experiences in nature. Aesthetic experiences in nature affect mood and indirectly promote wellbeing (Mastandrea, Fagioli, and Biasi Citation2019), and they have transformative and evaluative dimensions (Tomlin Citation2008). In understanding these experiences as transformative and evaluative, several facets of the experiences found in nature are qualitatively different. Two of these facets are the experiences of beauty and the sublime (Graves, Løvoll, and Sæther Citation2020).

The sublime experience in nature is often recognized as holistic and evokes a large range of emotions. One of these emotions is awe, and it can be identified as a self-transcendent emotion which expand personal boundaries and can be transformative (Stellar et al. Citation2017). Further, it includes a sense of duration as well as a sense of nature’s capacity to ‘ … overwhelm our powers of perception and imagination’ (Alexander Citation2014, 52).

Empirical studies of friluftsliv give voice to how aesthetic experiences in nature are related to the sublime and evoke awe (Løvoll and Sæther Citation2022). These experiences involve a strong feeling of connectedness to nature and feeling at home in nature which are considered positive emotions. In this way, there is a trajectory from aesthetic experiences to the feeling of connectedness to nature. Nature is also a particular place where the positive emotion of belonging flourishes. This emotion of belonging nourishes wellbeing and self-transcendence toward a reorientation of our lives, goals, and values (Fuller Citation2012). Feeling at home in nature is not only about an experience of stability in an environment with some given qualities we strive to take care of and protect, but it is also about our creative process of making nature our home (Bergmann Citation2011, 32).

Wonder is a complex phenomenon and holds relevance for ethical consciousness, which is both intellectual and a motivation for practices (Vasalou Citation2012, 2). Also for Martin Seel (Citation1998), the aesthetic experience of nature is interwoven with an ethical dimension:

… the aesthetic of nature is […] simultaneously part of an ethics of the individual conduct of life […] for aesthetics, being concerned with specific forms of and opportunities for process-oriented activity, is generally part of an ethics of the good life. (342)

Referring to Böhme, Bergmann points out that aesthetics is ‘a self-aware human reflection on one’s living-in-particular surroundings’ (Citation2006, 336). Succinctly put, it is all about an awareness of who we are and how we are connected to nature (awareness of place), and it is this awareness that has intrinsic ethical implications. Building such an awareness is not a straightforward one-way process because there are layers of complexity in the emotional experience, as well as difficulties in transferring emotions into concepts and words. Hence, developing a more profound emotional awareness of our flourishing nature could take years. However, understanding our emotions can make us more wholehearted and better prepared to protect what is important to us, as well as facilitate the realization of what we deem meaningful in our lives (Nussbaum Citation2003).

Such an awareness of ethical impact is echoed in Vetlesen’s (Citation2015) writings, in which he contends that to feel deeply connected to nature is one of the most important virtues of our time. Underlying the reflections from Seel (Citation1998), Bergmann (Citation2006), and Vetlesen (Citation2015) is the role of emotions, which are expressed by phrases like feeling at home, aesthetic experiences, and feeling deeply connected. Hence, the role of emotions is crucial here. However, friluftsliv experiences could further be anthropocentric, setting human beings at the centre of our ethical awareness, which would lead to unlimited nature consumption, or they could be non-anthropocentric (Vetlesen Citation2015), identifying friluftsliv as a practice that could challenge the anthropocentric orientation. Including the relevance of planet well-being for human flourishing (Grenville-Cleave et al. Citation2021), human connection to nature needs this deeper conceptual analysis of how emotions in nature influence our wellbeing, attitudes, and thinking. Resources of attunement to nature as a cultural value is seen in Sami contributions (Skille, Pedersen, and Skille Citation2023), and in eco philosophic writings (Wold Citation2023).

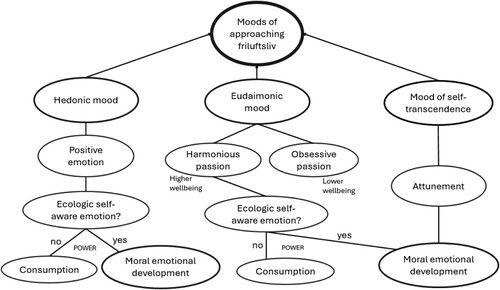

Feeling deeply connected to nature – emerging from aesthetic experiences – could nourish environmental ethical concerns. Paying attention to this emotional experience, being open to aesthetic experience, understanding the cultivation of it, and, finally, learning about aesthetic experiences in nature can stimulate a non-anthropocentric worldview. However, within aesthetic experiences in nature, there are different concepts that are empirically identified as those relating to classical interpretations of beauty (such as beautiful scenery) and those relating to the sublime (such as immersive communion with nature) (Graves, Løvoll, and Sæther Citation2020). These experiences have different functions and could point toward anthropocentrism when beauty of nature becomes a consumer experience, adding positive emotions to the hedonic adaptation. On the contrary, nurturing awe, wonder, and the sublime could have a self-transcendent function, enabling individuals to live in accordance with their own values. In this sense, friluftsliv might hold a key position in education to commence the emotional process of starting to develop an awareness of being a wholehearted, fully flourishing person, also in the sense of developing ratio and ethics (Næss Citation1999). By embracing the self-transcendent potential through engagement with nature, the idea of being mindfully present in nature and cultivating emotional connections to feeling at home in nature, contributes to articulating the concept of friluftsliv by a self-transcendent mood. Although the skill of being emotionally engaged by aesthetic experiences in nature could be trained and cultivated, these need to be put upfront in the idea of friluftsliv as relevant for our ethical awareness. A visual presentation of a more developed model of the hypothesized relationships between moods and consumption or moral emotional development is found in .

Implications for friluftsliv practices

Based on the presented perspectives on the moods of friluftsliv, three distinct and positive emotional paths can be identified. While each of them could be identified for example during a longer hike in nature, attention is directed to only one mood at the time. These emotional paths inform different aspects of wellbeing, with relevance for understanding unconscious power dynamics driving consumption (). How we see nature – what we pay attention to, feel, and engage in – has some intrinsic value components, which are directly connected to our thinking, assessments, choices, and values in life. Accordingly, friluftsliv invites a mindset approach and lifestyle when our experiences in nature become a strongly desired life project. However, wellbeing perspectives of life in nature point to consumerism in subtle ways, pointing to ‘immersion in nature’ as giving opportunities for transformative experiences as well as being part of the main problem of the consumer behaviour. The three different moods in friluftsliv, which typically include feeling states that are outside of our conscious awareness, inform ideas of consumption and how we move towards a higher-level awareness of friluftsliv and its contributions to an environmentally and psychological sustainability approach. Our analysis points to the need of mental change involving a conscious awakening to find sustainable ways to engage with nature. While this is developed as a conceptual analysis, empirical studies are needed to test the assumptions of moral emotional development through emotional awareness, and their implication for pro-environmental behaviour.

Engaging in friluftsliv could include shifting moods. Modern multidwelling lifestyles, including long travels, high energy consumption, infrastructure, and high living standards, challenge the idea of sustainability when seeking nature. How we present friluftsliv in thinking, planning for, and participation could be clarified with the identification of the three moods: What is the main goal of our friluftsliv? When experiencing hedonic adaptation through pleasure and striving for an increasing number of positive experiences, we are in a hamster wheel of hedonism. There is a danger that hedonic adaption inspires the anthropocentric and individualistic view of happiness at the cost of nature erosion in popular areas, transportation, and general consumption. We then become nature consumers at the cost of pristine nature and ecological footprint, which invites a reconsidering of the idea of outdoor education as a sustainable practice (Jeffs and Ord Citation2018). If friluftsliv, by its literary Scandinavian roots should be an alternative to nature consumption, the articulation of friluftsliv needs critical reflection of how and why we pay attention to immersive nature experiences in the first place. We would need to re-establish the relationship to nature through new and more sustainable practices, based on a complex understanding of immersion in nature and the wider context of acknowledging the existing nature as well as society (Wayman Citation2018). Inspired by the term friluftsliv, the mindfulness perspective and ecological awareness can refresh our attention and mindset. While all three moods carry potential for wellbeing, the third mood, the mood of self-transcendence, carry a stronger potential to revitalize the Scandinavian roots of friluftsliv as a contribution to sustainable lifestyles. This would be a more direct way of approaching the idea of linking friluftsliv experience to moral emotional development, with implications for pro-environmental choices.

Very often, activities seem to be dominating when understanding friluftsliv. Several considerations in ‘thinking about friluftsliv’ should be invited in these different phases of the total experience: planning for trips, deciding on equipment, facilities, and travel. Our analysis sheds light on the philosophy and psychology of friluftsliv, where different moods involve power relations relevant to understanding ethical awareness and consumption. This finding highlights the agentic perspective of practicing friluftsliv in a mindful and self-transcendent manner as a core attitude for the promotion of wellbeing – and environmental sustainability. Rethinking the term ‘friluftsliv’ in the era of the fourth industrialized revolution, and severe troubles in keeping nature and environmental sustainability, understanding the differences between moods of nature immersion can move forward the question of ‘how to promote a sustainable lifestyle’ in formal and informal friluftsliv education. In the promotion of friluftsliv, power dynamics of consumption should be considered in understanding how immersion in nature depends on our emotional awareness within different moods.

Conclusion

We offer a new framework to understand the different moods of approaching friluftsliv. The three moods – the hedonic, eudaimonic, and self-transcendence – can be construed as contrasting notions of friluftsliv with different paths of ethical consciousness concerning wellbeing, consumption, and sustainability. The underlying aspects of power dynamics, identified through our readiness to be emotionally aware, form our intentions, attention, and attitudes towards nature immersion in subtle ways. The moods of hedonic, eudaimonic, and self-transcendence all appear as typical attributes in friluftsliv.

By recognizing emotions in our development of value judgments, education for the future should acknowledge friluftsliv and develop a didactic practice that inspires the mood of self-transcendence and a deeper attunement with nature as an emotional process. Because the development of this specific mood is a time-intensive process, it would be imperative to pay attention to this mood from preschool to higher education. In today’s world, where we are more physically disconnected from nature and ourselves, cultivating the self-transcendent mood is highly encouraged to promote wellbeing and make environmentally sustainable decisions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Example: News coverage from the USA by CNN https://edition.cnn.com/2021/02/05/health/friluftsliv-norway-sad-wellness/index.html.

References

- Aall, C., I. G. Klepp, A. B. Engeset, S. E. Skuland, and E. Støa. 2011. “Leisure and Sustainable Development in Norway: Part of the Solution and the Problem.” Leisure Studies 30 (4): 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.589863.

- Alexander, K. E. 2014. Saving Beauty: A Theological Aesthetics of Nature. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

- Anderson, D. J., and T. Krettenauer. 2021. “Connectedness to Nature and pro-Environmental Behaviour from Early Adolescence to Adulthood: A Comparison of Urban and Rural Canada.” Sustainability 13 (7): 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073655.

- Arnould, E. J., and C. J. Thompson. 2005. “Consumer Culture Theory (CCT): Twenty Years of Research.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (4): 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1086/426626.

- Ashby, F. G., A. M. Isen, and U. Turken. 1999. “A Neuropsychological Theory of Positive Affect and its Influence on Cognition.” Psychological Review 106 (3): 529–550. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.529.

- Bachman, E. 2010. Friluftsliv in Swedish Physical Education – a Struggle of Values: Educational and Sociological Perspectives. Ph.d. thesis. University of Stocholm.

- Beery, T. H. 2013. “Nordic in Nature: Friluftsliv and Environmental Connectedness.” Environmental Education Research 19 (1): 94–117. DOI: 10.1080/13504622.2012.688799.

- Bergmann, S. 2006. “Atmospheres of Synergy: Towards an eco-Theological Aesth/Ethics of Space.” Ecotheology 11 (3): 326–356. https://doi.org/10.1558/ecot.2006.11.3.326.

- Bergmann, S. 2011. “Aware of the Spirit: In the Lense of a Trinitarian Aesth/Ethics of Lived Space.” In Ecological Awareness: Exploring Religion, Ethics and Aesthetics, edited by S. Bergmann, and H. Eaton, 23–39. Münster: LiT Verlag.

- Bergmann, S., and H. Eaton. 2011. “Awareness Matters.” In Ecological Awareness: Exploring Religion, Ethics and Aesthetics, edited by S. Bergmann, and H. Eaton, 1–7. Münster: LiT Verlag.

- Berridge, K. C., and T. E. Robinson. 2016. “Liking, Wanting, and the Incentice-Sensitization Theory of Addiction.” American Psychologist 71 (8): 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000059.

- Branch, M. P. 2004. Reading the Roots. American Nature Writing Before Walden. Athens (Georgia): The University of Georgia Press.

- Breivik, G. 2020. “Richness in Ends, Simpleness in Means!’ on Arne Naess’s Version of Deep Ecological Friluftsliv and its Implications for Outdoor Activities.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 15 (3): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2020.1789719.

- Breunig, M. 2022. “Slow Nature-Focused Leisure in the Days of COVID-19: Repressive Myths, Social (in)Justice, and Hope.” Annals of Leisure Research 25 (5): 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1859390.

- Brickman, P., and D. T. Campbell. 1971. “Hedonic Relativism and Planning the Good Society.” In Adaptation Level Theory: A Symposium, edited by M. H. Apley, 287–302. New York: Academic Press.

- Capaldi, C. A., H.-A. Passmore, E. K. Nisbet, J. M. Zelenski, and R. L. Dopko. 2015. “Flourishing in Nature: A Review of the Benefits of Connecting with Nature and its Application as a Wellbeing Intervention.” International Journal of Wellbeing 5 (4): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v5i4.1.

- Castro, I. A., H. Hoena, E. Cornelis, and A. Majmundar. 2022. “The Friluftsliv Response: Connection, Drive, and Contentment Reactions to Biophilic Design in Consumer Environments.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 39 (2): 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.09.007.

- Crowley, T. 2013. “Climbing Mountains, Hugging Trees: A Cross-Cultural Examination of Love for Nature.” Emotion, Space and Society 6: 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.10.005.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1975. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: HarperPerennial.

- Damasio, A. R. 1999. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Davis, N., and B. Gatersleben. 2013. “Transcendent Experiences in Wild and Manicured Settings: The Influence of the Trait “Connectedness to Nature”.” Ecopsychology 5 (2): 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2013.0016.

- Farkić, J., S. Filep, and S. Taylor. 2020. “Shaping Tourists’ Wellbeing Through Guided Slow Adventures.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28 (12): 2064–2080. DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1789156.

- Fredrickson, B. L. 2004. “The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 359 (1449): 1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512.

- Fuller, R. 2012. “From Biology to Spirituality: The Emotional Dynamics of Wonder.” In Practices of Wonder: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by S. Vasalou, 64–87. Eugene: Pickwick Publications.

- Garvey, P. 2008. “The Norwegian Country Cabin and Functionalism: A Tale of two Modernities.” Social Anthropology 16 (2): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8676.2008.00029.x.

- Gelter, H. 2000. “Friluftsliv: The Scandinavian Philosophy of Outdoor Life.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 5 (1): 77–92. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/302.

- Gelter, H. 2010. “Friluftsliv as Slow and Peak Experiences in the Transmodern Society.” Norwegian Journal of Friluftsliv, 1–22. http://norwegianjournaloffriluftsliv.com/.

- Gladwell, V., D. Brown, C. Wood, G. Sandercock, and J. Barton. 2013. “The Great Outdoors: How a Green Exercise Environment Can Benefit all.” Extreme Physiology & Medicine 2 (1): 3. http://www.extremephysiolmed.com/content/2/1/3.

- Grau-Ruis, R., H. S. Løvoll, and G. Dyrdal. 2024. “Norwegian Outdoor Happiness: Residential Outdoor Spaces and Active Leisure Time Contributions to Subjective Well-Being at the National Population Level Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Happiness Studies 25 (9): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00732-z.

- Graves, M., H. S. Løvoll, and K.-W. Sæther. 2020. “Friluftsliv: Aesthetic and Psychological Experience of Wilderness Adventure.” In Issues in Science and Theology: Nature and Beyond, edited by M. Fuller, D. Evers, A. Runehov, B. Souchard, and K.-W. Sæther, 207–220. Berlin, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, and New York City: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31182-7.

- Grenville-Cleave, B., D. Gudmundsdottir, F. Huppert, V. King, D. Roffey, S. Roffey, and M. de Vries. 2021. Creating the World we Want to Live in. How Positive Psychology Can Build a Brighter Future. New York: Routledge.

- Haidt, J. 2003. “The Moral Emotions.” In Handbook of Affective Sciences, edited by R. Davidson, K. Scherer, and H. Goldsmith, 855. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Henderson, B., and N. Vikander. 2007. Nature First: Outdoor Life the Frilufsliv way. Toronto: Natural Heritage Books.

- Hofmann, A. R., C. Rolland, K. Rafoss, and H. Zoglowek. 2018. Norwegian Friluftsliv. A way of Living and Learning in Nature. Münster: Waxmann.

- Howell, A. J., R. L. Dopko, H. A. Passmore, and K. Buro. 2011. “Nature Connectedness: Associations with Well-Being and Mindfulness.” Personality and Individual Differences 51 (2): 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.037.

- Høyem, J. 2008. “Miljøvennlig Friluftsliv.” Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 49 (4): 629–636. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-291X-2008-04-08.

- Intelisano, S., J. Krasko, and M. Luhmann. 2020. “Integrating Philosophical and Psychological Accounts of Happiness and Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (1): 161–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00078-x.

- James, W. 1890. The Principles of Psychology (Vol. 1). New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- Jeffs, T., and J. Ord. 2018. Rethinking Outdoor, Experiential and Informal Education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. 2015. “Mindfulness.” Mindfulness 6 (6): 1481–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0456-x.

- Kellert, S. R., and E. O. Wilson. 1993. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Washington, D.C.: Shearwater Books/Island Press.

- Keltner, D. 2023. Awe. The new Science of Everyday Wonder and how it Can Transform Your Life. New York: Penguin Press.

- Knez, I., and I. Eliasson. 2017. “Relationships Between Personal and Collective Place Identity and Well-Being in Mountain Communities.” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (79): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00079.

- Kotera, Y., M. Richardson, and D. Sheffield. 2022. “Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy on Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 20 (1): 337–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00363-4.

- Krys, K., O. Kostoula, W. A. P. van Tilburg, O. Mosca, J. H. Lee, F. Maricchiolo, A. Kosiarczyk, … Y. Uchida. 2024. “Happiness Maximization is a WEIRD Way of Living.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231208367.

- Laumann, K. 2004. “Restorative and Stress-Reducing Effects of Natural Environments: Experiencal, Behavioural and Cardiovascular Indices.” PhD. University of Bergen.

- Løvoll, H. S., and K.-W. Sæther. 2022. “Awe experiences, the sublime, and spiritual wellbeing in Arctic wilderness.” Frontiers in Psychology 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.973922.

- Mastandrea, S., S. Fagioli, and V. Biasi. 2019. “Art and Psychological Well-Being: Linking the Brain to the Aesthetic Emotion.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (739): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00739.

- Moran, J. 2002. Interdiciplinarity: The new Critical Idiom. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nisbet, E. K., J. M. Zelenski, and S. A. Murphy. 2011. “Happiness is in our Nature: Exploring Nature Relatedness as a Contributor to Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 12 (2): 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9197-7.

- Næss, A. 1999. Det frie menneske: En innføring i Spinozas filosofi (3rd ed.). Oslo: Kagge Forlag.

- Nussbaum, M. 2003. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nussbaum, M. 2011. Creating Capabilities. The Human Development Approach. Cambridge: Belknap Harvard.

- Oatley, K. 1992. Best Laid Schemes. The Psychology of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ord, J. 2018. “Mountains, Climbing and Informal Education.” In Rethinking Outdoor, Experiential and Informal Education. Routledge, edited by T. Jeffs, and J. Ord, 108–123. London and New York.

- Passmore, H.-A., and A. J. Howell. 2014. “Nature Involvement Increases Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A two-Week Experimental Study.” Ecopsychology 6 (3): 148–154.

- Pedersen Gurholt, K. 2008. “Norwegian Friluftsliv and Ideals of Becoming an ‘Educated man.’.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 8 (1): 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670802097619.

- Pirchio, S., Y. Passiatore, A. Panno, M. Cipparone, and G. Carrus. 2021. “The Effects of Contact with Nature During Outdoor Environmental Education on Students’ Wellbeing, Connectedness to Nature and pro-Sociality.” Frontiers in Psychology 12. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389fpsyg.2021.648458.

- Polley, S. 2021. “Professionalism, Professionalisation and Professional Currency in Outdoor Environmental Education.” In Outdoor Environmental Education in Higher Education. International Explorations in Outdoor and Environmental Education, edited by G. Thomas, J. Dyment, and H. Prince, 9, 363–373. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75980-3_30.

- Pritchard, A., M. Richardson, D. Sheffield, and K. McEwan. 2020. “The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Happiness Studies 21 (3): 1145–1167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6.

- Ryff, C. D., and B. H. Singer. 2008. “Know Thyself and Become What you are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being.” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (1): 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-.

- Schutte, N. S., and J. M. Malouff. 2018. “Mindfulness and Connectedness to Nature: A Meta-Analytic Investigation.” Personality and Individual Differences 127: 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.034.

- Seel, M. 1998. “Nature: Aesthetics of Nature and Ethics.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, edited by M. Kelly, Vol. 3, 341–343. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sjödin, K. 2024. “Friluftsliv och naturmöten i utbildningspraktik.” Ph.D. theses. Örebro universitet, Institutionen för hälsovetenskaper.

- Skille, EÅ, S. Pedersen, and Ø Skille. 2023. “Friluftsliv and Olggonastin – Multiple and Complex Nature Cultures.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2023.2254862.

- Skov, M. 2023. “Sensory Liking.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Neuroaesthetics, edited by M. Skog, and M. Nadal, 31–62. London and New York: Routledge.

- Slingsby, W. C. 1904/2022. Norway, the Northern Playground. Sketches of Climbing and Mountain Exploration in Norway Between 1872 and 1903. Hungerford: Franclin Classics.

- Stark, E., K. C. Berridge, and M. L. Kringelbavh. 2023. “The Neurobiology of Liking.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Neuroaesthetics, edited by M. Skov, and M. Nadal. London and New York: Routledge.

- Statistics Norway. 2021. Land use Planning, Cultural Heritage, Nature and Local Environment. https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank/table/10146/tableViewLayout1/.

- Steger, F. M. 2016. “Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and Meaning: Me Versus us; Fleeting Versus Enduring.” In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being, edited by J. Vittersø, 175–182. Berlin, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, and New York City: Springer International.

- Stellar, J. E., A. M. Gordon, P. K. Piff, D. Cordaro, C. L. Anderson, Y. Bai, L. A. Maruskin, and D. Keltner. 2017. “Self-transcendent Emotions and Their Social Functions: Compassion, Gratitude, and awe Bind us to Others Through Prosociality.” Emotion Review 9 (3): 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916684557.

- St.meld.18. (2015) 2016. “Friluftsliv. Natur som kilde til helse og livskvalitet.” Regjeringen.no.

- Stockwell, L. 2023. “Reinterpreting the ‘Professional'-isation of Outdoor Education in the Context of Higher Education.” In Reflections on Identity, edited by N. Hopkins, and C. Thompson, 123–135. Berlin, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, and New York City: Springer Nature.

- Tomkins, S. S. 1970. “Affect as the Primary Motivational System.” In Feelings and Emotions, edited by M. B. Arnold, 101–110. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Tomlin, A. 2008. “Introduction.” In Aesthetic Experience, edited by R. Shusterman, and A. Tomlin. New York: Routledge.

- Vallerand, R. 2010. “On Passion for Life Activities: The Dualistic Model of Passion.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by M. Zanna, 97–193. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- van Heel, B. F., R. J. G. van den Born, and N. A. Aarts. 2024. “Multidimensional Approach to Strengthening Connectedness with Nature in Everyday Life: Evaluating the Earthfulness Challenge.” Sustainability 16 (3): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031119.

- Vasalou, S. 2012. “Introduction.” In Practices of Wonder: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives, edited by S. Vasalou, 1–15. Eugene: Pickwick Publications.

- Vetlesen, A. J. 2015. The Denial of Nature. Environmental Philosophy in the era of Global Capitalism. London: Routledge.

- Vikene, O. L., R. Fretland, S. Hole, and H. S. Løvoll. 2023. “Ut på tur med app – Teknologi i Hverdagens Bevegelseskultur.” Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum 14: 205–223. ISSN 2000-088x. https://sportstudies.org/2023/12/06/ut-pa-tur-med-app-teknologi-i-hverdagens-bevegelseskultur/

- Vittersø, J. 2016. “The Feeling of Excellent Functioning.” In Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being, edited by J. Vittersø, 253–276. Berlin, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, and New York City: Springer International Publishing.

- Vittersø, J., and Y. Søholt. 2011. “Life Satisfaction Goes with Pleasure and Personal Growth Goes with Interest: Further Arguments for Separating Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 6 (4): 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.584548.

- Walsh, Elena. 2021. “Moral Emotions.” In Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science, edited by Todd K. Shackelford, and Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, 5209–5216. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_650

- Waterman, A. S., S. J. Schwartz, and R. Conti. 2008. “The Implications of two Conceptions of Happiness (Hedonic Enjoyment and Eudaimonia) for the Understanding of Intrinsic Motivation.” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (1): 41–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9020-7.

- Wayman, S. 2018. “Fostering Sustainability in Outdoor and Informal Education.” In Rethinking Outdoor, Experiential and Informal Education, edited by T. Jeffs, and J. Ord, 169–183. London and New York: Routledge.

- Wold, D. E. 2023. “Ferd Toward a Joyful Change: Nature, Mountaineering Philosophers, and the Dawn of “Higher” Friluftsliv Education.” In Views of Nature and Dualism, edited by T. J. Hastings, and K.-W. Sæther, 93–120. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wolsko, C., and K. Lindberg. 2013. “Experiencing Connection with Nature: The Matrix of Psychological Well-Being, Mindfulness, and Outdoor Recreation.” Ecopsychology 5 (2): 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2013.0008.

- Xue, J., P. Næss, H. Stefansdottir, R. Steffansen, and T. Richardson. 2020. “The Hidden Side of Norwegian Cabin Fairytale: Climate Implications of Multi-Dwelling Lifestyle.” Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 20 (5): 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2020.1787862.