ABSTRACT

Local councils governing Auckland, New Zealand, underwent restructuring in 2010, amalgamating eight local authorities and establishing the Auckland Council as a unitary authority. Key objectives for Auckland’s amalgamation included achieving reform and a single direction in governance, facilitating democratic representation of local communities, overcoming prevalent problems of fragmentation in governance and addressing lack of engagement from local communities. Qualitative interviews with key public and private sector stakeholders suggest the amalgamation effected changes to collaborative practices in anticipation of the restructure and after the amalgamation occurred. The creation of one council eased many collaborative processes. At the same time, the amalgamation strained collaboration in several ways.

Introduction

Regions adopt municipal amalgamation as an expansion strategy for various reasons, including the small size of municipalities (Calciolari et al. Citation2013), cost savings associated with amalgamation, improved accountability, better economic growth (Schwartz Citation2009), reduced governance and elimination of service replication (Kushner and Siegel Citation2003). Perceived lack of collaboration and coordination in merged jurisdictions frequently features as a justification for municipalities to subsequently opt out of the merger (Sancton Citation2005). A review of experiences in metropolitan areas that have undergone jurisdictional changes reveals that collaboration in amalgamated cities is challenging, as it is a process involving joint decision-making in ‘problem domains’ (Gray Citation1989, p. 227).

In 2010, Auckland, the largest of city of New Zealand, amalgamated eight previously separate local councils to form a unitary governing body (GB) – the Auckland Council (AC). The eight disestablished local bodies were the Auckland City Council, Auckland Regional Council (ARC), Franklin District Council, Manukau City Council, North Shore City Council, Papakura District Council, Rodney District Council and Waitakere City Council. The establishment of a unitary authority stipulated changes in the new council’s structure, functions, responsibilities and authorities, which made it unique among local and regional councils in New Zealand. The objective of this original research is to analyse changes that may have occurred to ways of collaborating as a consequence of the formation of the ‘supercity’.

Collaboration in amalgamated cities

Irrespective of the metropolitan governance model, combining established municipalities that can deliver a ‘consensual … leadership … framework within which municipalities can voluntarily cooperate with each other’ is a daunting task (Schwartz Citation2009, p. 12). Enthusiasm for amalgamations is rarely unilateral (Boudreau et al. Citation2006); feelings of discontent start to increase when proponents perceive that attention to local neighbourhoods is diminished under the new model. Under-representation in the larger jurisdiction creates tensions within metropolitan arenas (Tomas Citation2012). Larger metropolitan areas consolidate regulations and services, often leading to increased taxes and fees. When the increased costs are not matched with enhanced redistributive policies and do not seem to yield tangible benefits, the imbalance leads to stakeholder discontent (McKinlay Citation2011).

Cases from across the globe demonstrate that merged jurisdictions struggle to work collaboratively. Swedish reforms started in 1952 cut local government units from 2500 to 282 (Gustafsson Citation2007), and by the late 1970s, Sweden accepted separation of hostile municipalities from the merger because enmity between municipalities impeded cooperation. In Queensland, Australia, the 2007 amalgamation of local councils reduced local authorities from 157 to 73 (Drew et al. Citation2014), but organisational differences and loss of political representation led four of the councils to separate from the union (de Souza et al. Citation2015). In Canada, both Toronto and Montreal amalgamated to stimulate economic growth (Weir and Rongerude Citation2007). Sheer size and diversity presented severe challenges to coordination, however (Boudreau et al. Citation2006; Quesnel Citation2006; Smith Citation2007). Although the merger had the support of trade and labour unions, suburban citizens opposed it, and tensions between English-speaking and French-speaking populations mounted (Smith Citation2007). Increased competition favoured by the new megacity model, which threatened local retailers, was not universally supported (Boudreau et al. Citation2006), and in 2006, 15 out of the 27 suburban districts seceded (Tomas Citation2012). Although the aim of the new system was to create a collaborative approach to governance, discontent continues between demerged areas and the government today (Boudreau et al. Citation2006).

A preponderance of published literature suggests that the objectives of amalgamation are not always achieved (Sancton Citation2005), that effective coordination post-merger is absent and that no savings are made on service costs levied by supercities (Schwartz Citation2009). These failings are evident in Spain, France, Italy and Germany (Dollery and Robotti Citation2008; Wollmann Citation2010), Scandinavia (De Ceuninck et al. Citation2010; Vrangbæk Citation2010), Eastern Europe (Swianiewicz Citation2010), the US (Leland and Thurmaier Citation2006; Leland and Thurmaier Citation2010; Faulk and Hicks Citation2011; Faulk and Grassmueck Citation2012), Greece (Hlepas Citation2010) and Macedonia (Kreci and Ymeri Citation2010).

The creation of the Auckland supercity

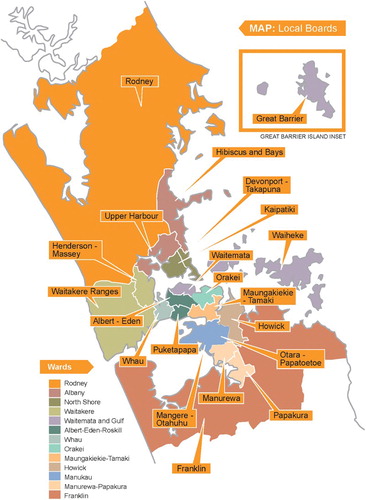

Campaigns supporting the amalgamation of Auckland have been regularly mounted since as early as 1901 (Edgar Citation2012), when friction, divisiveness and disharmony dogged councils and boards due to fundamental differences in philosophy, responsibilities and cost-sharing ideas. In 1989, the national government reviewed and restructured local governance systems, introducing regional councils with mandated functions (Collins and Wardlow Citation2011). The Auckland Regional Authority was reborn as the ARC, its former 44 local authorities rebranded as four cities and three districts (Dixon and Dupuis Citation2003), a relatively stable structure that lasted 21 years, from 1989 to 2010 (Edgar Citation2012). Recent re-emerging issues of fragmentation in governance and lack of engagement from local communities led to the 2010 amalgamation of eight local councils into a unitary authority. The resultant AC consists of 21 local boards (LBs) and 13 wards, collectively referred to as ‘Auckland City’ (). Based on its unprecedented and unique-to-New Zealand size, the merger was informally labelled a ‘supercity’ (Blakely Citation2015, p. 10).

Figure 1. Map of Auckland Region, wards and local areas. Source: Figure reproduced from AC (Citation2012).

AC structure

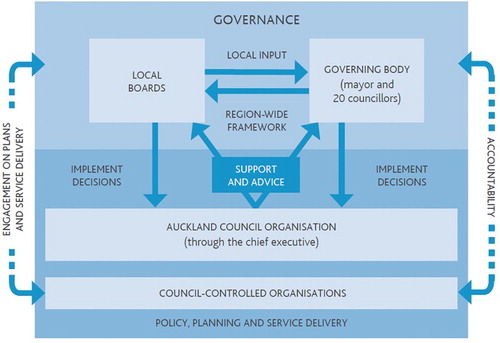

The AC is made up of two elected bodies: the GB, chaired by a mayor and attended by 20 councillors; and 21 LBs, representing local communities and comprised of board members elected by constituents. The GB is responsible for region-wide strategic decision-making. The LBs focus on matters related to their specific areas, provide leadership for communities and input to region-wide strategies and plans (AC Citation2012). Council Controlled Organisations (CCOs) were also established to assist the AC in achieving its strategic goals. Some CCOs are responsible for the delivery of important services and may manages assets valued at >$10 million. illustrates how the AC works today.

Figure 2. Components and structure of the AC. Source: Figure reproduced from AC (Citation2011, p. 29).

Emerging issues

In 2014, three years after its establishment, the AC signalled difficulties by embarking on a review of the seven CCOs (AC Citation2014). Issues cited included a lack of understanding between the councillors and LB members regarding management, ownership and governance; miscommunication causing councillors to bear responsibility for CCO blunders; councillors taking over the roles of CCOs; and the CSOs’ ‘no-surprises’, open communication policy not being reciprocated by the mayor (Orsman Citation2014; AC Citation2015). These disagreements in working style and confusion over roles led to the CCO review.

In addition, it seems that while amalgamation provided the region with opportunities associated with increased scale, capacity and resources, it also brought challenges related to the merging of incompatible regulatory systems. Eight property rating systems were combined to create a region-wide, proportional, single rating system based on capital value. This resulted in a huge increase in government valuations and rates payments for some property owners and to decreases for others. A new property revaluation scheme and a uniform charge meant that high-value property owners were required to pay more than they did previously. These changes led to dissatisfaction among Aucklanders who owned property in the region (Orsman Citation2014, p. A9).

Materials and methods

Data about the municipal amalgamation of Auckland City were gathered by conducting qualitative interviews with 41 participants from key public and private sector organisations in the region. In-depth, face-to-face interviews were conducted with practitioners employed by the AC, municipal associations, small-to-medium private enterprises (SMEs) based in the central and outlying areas of Auckland, cultural associations and non-government organisations (NGOs). Individual semi-structured interviews enabled identification of key factors that impact and influence collaborative decisions and actions. An interview guide that included a list of questions and the topics to be covered enabled consistency in the questions helped direct the discussion and ensured that the general areas of the research were covered. The questions were mostly open-ended, with some probes and a few scales. Probes were used to prompt further discussion and elaboration from participants.

Each interview lasted approximately one hour. Participants were 66% male and 34% female; all interviewees were ≥18 years of age. Over 58% of the participants were from the public sector, while private sector participants made up >46% of the 41 interviewees. The private sector participants comprised businesses (>26%) and associations (>31%). More than 34% of the organisations represented were SMEs (with <30 full-time employees), and nearly 66% were large businesses or organisations (with ≥30 full-time employees). Data gathered were based on the opinions and viewpoints expressed by the interviewees.

To ensure the anonymity, confidentiality and the rights of the participants involved, the identity or any information that identifies the participants are not revealed. All comments or direct quotes are presented in a manner that does not reveal the identity of the informant. References made to any individual or agency during the interviews are concealed and presented in a way that did not affect the flow of the narrative and still gives clarity to readers.

Results

Ways in which Auckland’s amalgamation facilitated collaboration

The majority of the interviewees (92%) believed that the creation of one entity has made collaboration within the region easier in many ways. A participant from an Auckland think tank commented:

The way the supercity is now, instead of having meetings with four or five different heads of councils or heads of different … organisations, you only meet with one person, and they try and understand your business better and push you forward. It’s all very good.

I have to say the supercity is working; it’s starting to reflect that the supercity and the subsequent collaboration between all the departments of the government within the council and major players are working. The collaboration stretches to organisations like the Property Council to the Employers and Manufacturers’ Association to the Chamber of Commerce to business forums to the Automobile Association.

Interviewees also believe the greater authority and size of the current city have generated a more collaborative approach. One councillor commented, ‘Very few organisations are game enough to go against this council. Because it is that big and powerful, they are forced to collaborate with people.’ The size of Auckland is seen by interviewees as a factor that compels attention from the central government and national public agencies. When there were eight different councils, central government agencies had difficulty in collaborating with them. The CEO of an Auckland CCO noted, ‘It was really difficult to get departments to work together for different councils.’ Interviewees note that AC’s satellite organisations are now able to take a holistic view of the region, enabling strategic distribution of resources according to changing regional requirements, which ‘puts [Auckland] way ahead of anywhere in the country’ as mentioned by the CEO of a national tourism organisation. A councillor noted, ‘Having one organisation that is professionally run, properly focused, positively engaged and has a mayor who is very engaging [in collaborative activities] has made processes simpler and more straightforward.’

The new council incorporates participants from the private sector in its governing structure and in the boards of its various CCOs. Most of these individuals are in positions that enable them to influence private sector processes and decisions. Several interviewees from large private companies noted this as a positive outcome and a factor that encourages collaboration from the private sector. Under the new structure, LBs are given the authority to initiate activities or projects in their regions that benefit local communities. The community and advisory boards that existed under the previous local councils only had an advocacy role within communities, and all events and activities had to be approved by the parent council. Although the previous local councils had closer contact with communities, some interviewees expressed the view that these local bodies lacked authority to influence decision-making.

Obstacles to collaboration caused by Auckland’s amalgamation

Some of the participants (6%) argued that Auckland’s restructuring had complicated things and had made the process of collaboration more difficult, while a few (2%) stated that the amalgamation had made no difference to collaboration. The AC’s structure is purportedly designed to enable co-governance by LBs and the GB; accordingly, the LBs are potentially significant local decision-makers, albeit with no resources of their own. The staff and other advisory services the LBs require are provided by the Council. According to one interviewee, this makes Auckland’s governing structure ‘neither one nor the other … what they have ended up with is a hybrid’. A statement by the previous deputy mayor of the AC, who was commenting on 5 years’ performance since the amalgamation, conveys similar views: ‘The co-governance model is still evolving in terms of the interface between what LBs do and what the GB does, and that will take a while to settle.’

As noted by one ward councillor:

Where collaboration is being hindered is through the votes system. You have got to look after your home patch. I could be collaborative without being political if I have been supportive of everything that [the mayor] stands for. I support a lot of his stuff, not all of it, but if I were a supporter of [the mayor] around the council table, I would get kicked out. So I can collaborate to an extent. That’s not what my people want. Collaboration is only slowed down by political realities. At the end of the day, you have got to represent the wishes and wants and needs of your local community, and sometimes, that is not the needs and wants of the mayor of the AC. So, I could probably do better on collaboration at the end of my tenure.

[The areas whose councils were disestablished are] the ones probably feeling the most disempowered by the supercity. They used to be able to knock on the door of the council to get an answer. Some of them are feeling the AC is getting too big, too powerful, and there is nothing they can do to change it.

Difficulties and confusion exist among some groups, including LBs, in understanding the responsibilities and accountabilities of the AC, and how the decision-making process works within the AC. One interviewee commented that concerns about ‘who controls whom’ within the AC represent a hurdle for anyone engaging in collaborative activities. In addition, some interviewees believe a lack of collaboration and coordination between local public agencies has led to duplication of tasks. Statements from some interviewees indicate that local and central government engagements are neither well-coordinated nor complementary.

Interviewees described ‘frustrations’ at not having any control over the consequences of Auckland’s restructuring. A tourism business operator from a peripheral area noted that their regional ‘offices were taken away’, and they were left struggling, ‘trying to re-establish again’. Some regional associations that were formerly singular agencies were split between two or more areas, while others went under the boundary of a different area, causing loss of business and funding to the organisations. An operator from one such organisation described the consequences:

[The organisations] were bound by local government formation, local government funding. Funding was taken away; funding was given to different areas in a different manner. Now, as an operator, you can imagine that is a very big thing to be controlled by an outside entity.

The structure of the AC has created uncertainty among SMEs and larger organisations about the right person to contact. An interviewee from a large private firm noted that due to the vastness of the AC, unless the person seeking contact knows someone higher in the Council’s hierarchy, getting through to the right person is difficult:

The biggest challenge, I think, is now that you have formed one big large local government with 8,000-odd employees, you have got a much larger bureaucracy, and unless you have got those key contacts with persons of influence in the top two to three tiers of management, then you are going to struggle. So the flip side to that same coin is that if your organisation is quite large and strong and powerful, those relationships and those collaborations are way better.

A number of interviewees described the top tier of the AC as ‘extremely accessible’; however, the same level of support does not seem to be available from the lower tiers. A senior employee from a large firm explained:

What you have got at the top two or three tiers is new people, and they are great to engage with. As you drop down the structure, you get the people that were there before [the amalgamation], and you still have a cultural dichotomy between the top and the middle and the bottom.

Comments made by interviewees from associations and SMEs from peripheral areas of Auckland reveal that pre-amalgamation feelings of distrust have not been ameliorated by the merger. An interviewee from a peripheral area described the amalgamation of areas that were formerly independent as akin to a business attempting to increase its customer base through hostile merger.

Local communities in outlying areas perceived that the 3-year cycles of local government mean that a degree of pressure is required for the AC to achieve its goals, whereas for local businesses, 3 years is not sufficient to achieve their targets. According to feedback at interviews, the pressure for the AC to achieve its goals within such a short timeframe may compel actions that are detrimental to local businesses and that bypass collaborative approaches. The feeling of ‘being left out’ was a recurring theme brought up by some business operators from peripheral areas. Participants from peripheral areas, in particular, expressed the feeling that they are isolated from most activities and events that occur in Auckland and have little opportunity to participate or benefit from them. A senior official from the Auckland branch of a national tourism association stated, ‘As an organisation, we feel that we are left out … As a branch, we are limited in what we can do. We try to do what we can.’

The perception that the AC’s interests are concentrated in Central Auckland has affected the enthusiasm of peripheral areas for working with the Council. One interviewee, who has been operating a motel business for 25 years in a peripheral area, stated, ‘A lot of outlying areas feel that [the Council] is focused on Auckland [central] City. There is no enthusiasm from [outlying] areas to do anything with [the Council].’

The new AC is perceived to be struggling with the novelty of the new structure itself. Understanding that changes will take time to implement and being supportive of those who get ‘frustrated when things don’t work immediately’ was felt to be essential to maintaining the momentum of collaboration. Stakeholders’ confidence in the government having put the right processes in place was seen by interviewees as important in facilitating cooperation. It was suggested that the greater good in working together would be proved by the AC delivering economic benefits promised by politicians when Auckland was amalgamated. A recommendation that was repeated by a number of interviewees was to consistently deliver benefits and to avoid adding to the layers of bureaucracy.

Discussion

Positive perceptions

Based on interviewees’ comments, having one council has simplified comprehensive decision-making. Those who had worked with the previous eight councils stated that, prior to amalgamation, decision-making entailed a great deal of administration. Most interviewees felt that Auckland’s restructuring has created a cohesive, supportive ‘one-stop shop’. In general, the amalgamation is perceived to have created motivation across region to collaborate. Having one entity, one strategy and one set of goals makes it easier to communicate with different stakeholders, and stakeholders also find unity easier to comprehend. By combining previously separate councils, disagreements about the amount of funding that each should receive were eliminated.

In terms of the city’s NZ$3 billion budget and approximately 8000 employees, the AC is second only to the central government. Thus, bringing together the wider region is seen as a competitive advantage. Initiating economic development projects is believed to be easier now that organisers have a single body to deal with, which is responsible for and capable of decision-making. Previous studies have revealed that municipal malgamations provide economies of scale. After the merger reforms in Israel (Reingewertz Citation2012) and Germany (Blesse and Baskaran Citation2016) total expenditures were reduced in amalgamated municipalities compared to non-amalgamated municipalities.

Negative perceptions

However, co-governance of the GB and LBs appears to have affected collaboration in a negative way. This is evident from the subservience of LBs to the GB, an uncomfortable, unproductive relationship made impractical by the fact that AC officers work for both the GB and LBs. Since the AC pays these officers’ wages, it puts council staff in a difficult situation with respect to being impartial in serving both the GB and the LBs. Thus, structure for that tier of governance is suboptimal, and unless rectified, collaboration will continue to be inhibited between LBs and the GB.

The two-tier model comprises of an upper-tier GB encompassing a large geographic area and a lower tier that cover two or more municipal areas (Slack and Bird Citation2013). In principle, the upper tier is responsible for region-wide services and decision-making. Community-based engagement, determining and monitoring local services and bringing local perspectives to region-wide policies are assigned to the lower tier. The two-tier model is believed to have advantages over single-tier structures in terms of accountability, efficiency and local responsiveness according to Slack and Bird (Citation2013, p. 9). On the other hand, Kitchen (Citation1993 , p. 312) believes that councils with multi-level governing structures lead to ‘wrangling, inefficient decision-making, and delays in implementing policies’. Slack and Bird (Citation2013, p. 9) agree that two-tier structures tend to be ‘less transparent and more confusing to taxpayers, who can seldom determine precisely who is responsible for which services’.

When the GB’s plans differ from the needs and interests of voters, conflict between LBs and councillors arises, slowing down and straining the processes of collaboration. The councillors and LB members, who are compelled to please voters, may at times have to take a detached stance from other board and councillors. Although councillors and LB members are aware that certain decisions by the GB are made for the benefit of the wider region, they are unable to agree with the GB without losing the support of the areas that they represent.

It is clear that differences in opinions that occur between LBs and the GB are a barrier to effective collaboration. The current level of authority given to LBs is insufficient, and this lack of equality is an obstacle to achieving AC goals. Under Section 17 of the Local Government (Auckland Council) Act (Citation2009), the GB assigns decision-making responsibility to the LBs for non-regulatory functions of the Council that do not require an Auckland-wide approach, but whether this mandate is effective, and questions about whether it is practiced, may lead to the misconception that the GB can overrule LB decisions. Previously published literature does not capture this confusion: ‘When a local board [LB] makes a decision within the bounds of its delegated decision-making responsibility, that decision is a decision of the Council, and the GB cannot overturn it’ (Chen Citation2014, p. 13).

Role and power issues seem to stem from the way the governing structure of the AC has been established, with 20 ward councillors and members of the 21 LBs being elected by the areas they represent. The initial Royal Commission recommendation, which was to elect some councillors at large, as opposed to their being elected by wards, was not followed (Thomson et al. Citation2009). The purpose of the recommendation was to ensure transparency and to prevent councillors from focusing on local area matters instead of adopting a region-wide view (Chen Citation2014). When there is a lack of transparency, the issue of distrust will feature more prominently, particularly in the areas that objected to the restructuring.

Confusion about the role of the central government adds to the challenges of working collaboratively. LBs do not understand the responsibilities and accountabilities of the Council, and a perception that central and local government do not relate creates further confusion. This uncertainty leads to a private sector perception that competition between local and central governments exists, destabilising relationships across all sectors.

Communicating with divergent populations in a vast region where local communities previously had close relationships with their own local councils is perceived as problematic. Indeed, cultural SMEs illustrated this problem from their perspective. The inaccessible AC image contrasts with that of previous local councils, which provided full support to community-driven local organisations. Unfortunately, such backing is perceived to be absent after the restructuring by some key stakeholders.

Interviewees’ comments indicate a perception that collaborating under an amalgamated city structure is particularly daunting when different stakeholders have to work together towards lofty targets, such as those set for Auckland’s future. The AC targets may, in fact, be out of synch with what local organisations need. For example, requested guidance from the ATEED does not seem to be forthcoming, which has made tourism operators unsure of how to progress. This in turn has discouraged tourism stakeholders from collaborating with the ATEED. However, it is critical that any nascent misconceptions regarding Auckland’s focus on economic development be resolved in order to avoid potential negative consequences.

Some business groups voiced the strong opinion that any changes at local government level should not impact local businesses. They suggested that a system should be established to ensure that even if governments and leadership change, fundamental strategies are not altered or affected, so that consistency is maintained across or between different political landscapes. To encourage all stakeholders – particularly those from peripheral areas – to collaborate with the council and its satellite organisations, creating opportunities for them to input into AC plans and strategies is critical. In addition, suggestions provided by several interviewees indicate the key to eliminating misgivings and disputes is open communication, creation of awareness, honesty and transparency.

Study limitations

Relying on respondents’ recollection of past events is a limitation in that their reminiscences may have been influenced by evolving views on ease or difficulty of collaboration. The quality of qualitative inquiry can be enhanced using a range of flexible ‘craft skills’ that conform to eight principles: worthy topic, rich rigour, sincerity, credibility, resonance, significant contribution, ethics and meaningful coherence (Tracy Citation2010, p. 839). The research is based on a worthy, well timed, interesting, important and pertinent topic. Conducting in-depth interviews with a range of stakeholder groups provided insights from varied viewpoints. The purposefully selected information-rich participants enhanced the validity of this study through their in-depth understanding of the issues that were investigated. While this research relied heavily on interview data, thick descriptions of the findings enhanced the credibility of this study. Thick descriptions enhance research validity by capturing the thoughts and feelings of participants concerning a situation or action, and ascribing present and future intentionality to the behaviour (Ponterotto Citation2006, p. 539). Since support for the merger by interviewees was divided, opinions offered at interview may have been biased or subjective at the least, depending on whether the participant was supportive of the restructuring in the first instance. However, the interviewees’ opinions and thoughts on the amalgamation were not a focus for this research. Interviewees may not have supported or agreed with the amalgamation, but Auckland has undergone restructuring and it is the impact of this change on collaboration that this research focused on.

Conclusion

The amalgamation of Auckland has fostered collaboration across constituencies. At the same time, merging eight councils has strained collaborative processes. The structure of the AC and systems for electing councillors and LB members have created obstacles that hinder collaborative engagement between the GB and LBs. Confusion in understanding the roles of the Council versus the national government in developing the region impact negatively on motivation to collaborate. The top-heavy AC structure, perceptions of lack of transparency and inaccessibility, and the issue of peripheral areas being ignored constrain collaboration. These issues reflect the discord that has triggered amalgamated areas elsewhere in the world to de-amalgamate.

It is clear that support for amalgamated governance is divided in Auckland. The issues described by interviewees bring into focus some of the challenges involved in collaborating under an amalgamated city structure. Reflecting on the experiences of merged cities and regions across the world, overcoming barriers to collaboration is central to achieving the purposes and goals intended by municipal amalgamation. Whether the AC can achieve consensus is questionable, because nascent problems described are serious in that elsewhere in the world, such problems have caused ‘supercity ruptures’. However, the 92% support for the venture voiced by interviewees indicates the will to continue the Auckland experiment is still strong.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- [AC] Auckland Council. 2011. Background paper – Auckland economic development strategy. Auckland: Auckland Council.

- [AC] Auckland Council. 2012. Auckland plan: people and the economy [Internet]. [accessed 2014 Apr 8]. http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/planspoliciesprojects/plansstrategies/theaucklandplan/Pages/theaucklandplan.aspx.

- [AC] Auckland Council. 2014. Council to review super-city organisations [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Mar 3]. http://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/EN/newseventsculture/OurAuckland/mediareleases/Pages/CouncilToReviewSuper-CityOrganisations.aspx.

- [AC] Auckland Council. 2015. Council Controlled Organisations governance and monitoring committee open agenda [Internet]. [accessed 2015 Aug 31]. http://infocouncil.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/Open/2015/03/COU_20150303_AGN_5666_SUP.htm.

- Blakely R. 2015. The planning framework for Auckland ‘super city’: an insider’s view. Policy Quarterly. 11:3–14.

- Blesse S, Baskaran T. 2016. Do municipal mergers reduce costs? Evidence from a German federal state. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 59:54–74. [Internet]. [accessed 2017 Jul 26]. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166046216300254. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2016.04.003

- Boudreau JA, Hamel P, Jouve B, Keil R. 2006. Comparing metropolitan governance: the cases of Montreal and Toronto. Progress in Planning. 66:7–59. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2006.07.005

- Calciolari S, Cristofoli D, Macciò L. 2013. Explaining the reactions of Swiss municipalities to the ‘amalgamation wave’: at the crossroad of institutional, economic and political pressures. Public Management Review. 15:563–583. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2012.698852

- Chen M. 2014. Transforming Auckland: the creation of Auckland Council. Wellington: LexisNexis NZ Limited.

- Collins FL, Wardlow F. 2011. Making the most of diversity? The intercultural city project and a rescaled version of diversity in Auckland, New Zealand. Urban Studies. 48:3067–3085. doi: 10.1177/0042098010394686

- De Ceuninck K, Reynaert H, Steyvers K, Valcke T. 2010. Municipal amalgamations in the low countries: same problems, different solutions. Local Government Studiees. 36:803–822. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2010.522082

- de Souza SV, Dollery BE, Kortt MA. 2015. De-amalgamation in action: the Queensland experience. Public Management Review. 17:1403–1424. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2014.930506

- Dixon J, Dupuis A. 2003. Urban intensification in Auckland, New Zealand: a challenge for new urbanism. Hous Stud; 18:353–368. doi: 10.1080/02673030304239

- Dollery B, Robotti L, editors. 2008. The theory and practice of local government reform. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Drew J, Kortt MA, Dollery B. 2014. Economies of scale and local government expenditure: evidence from Australia. Administration & Society. 46:632–653. doi: 10.1177/0095399712469191

- Edgar J. 2012. Urban legend Sir Dove-Myer Robinson. Salisbury: Griffin Press.

- Faulk D, Grassmueck G. 2012. City–county consolidation and local government expenditures. State and Local Government Review. 44:196–205. doi: 10.1177/0160323X12447955

- Faulk D, Hicks M. 2011. Local government consolidation in the United States. New York (NY): Cambria Press.

- Gray B. 1989. Collaborating: finding common ground for multiparty problems. London: Jossey-Bass.

- Gustafsson G. 2007. Modes and effects of local government mergers in Scandinavia. West European Politics. 3:339–357. doi: 10.1080/01402388008424290

- Hlepas NK. 2010. Incomplete Greek territorial consolidation: from the first (1998) to the second (2008–09) wave of reforms. Local Government Studies; 36:223–249. doi: 10.1080/03003930903560596

- Kitchen H. 1993. Efficient delivery of local government services. Government and competitiveness project. Kingston: School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University.

- Kreci V, Ymeri B. 2010. The impact of territorial re-organisational policy: interventions in the Republic of Macedonia. Local Government Studies. 36:271–290. doi: 10.1080/03003930903560646

- Kushner J, Siegel D. 2003. Effect of municipal amalgamations in Ontario on political representation and accessibility. Canadian Journal of Political Science; 36:1035–1051. doi: 10.1017/S0008423903778950

- Leland SM, Thurmaier K. 2006. The municipal yearbook. Washington (DC): International City/County Management Association. Chapter 1A, Lessons from 35 years of city–county consolidation attempts; p. 3–10.

- Leland SM, Thurmaier K. 2010. City–county consolidation: promises made, promises kept? Washington (DC): Georgetown University Press.

- Local Government (Auckland Council) Act, New Zealand Statues s17. 2009. [Internet]. [accessed 2014 Aug 4]. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2009/0032/83.0/DLM2044909.html.

- McKinlay P. 2011. Integration of urban services and good governance: the Auckland supercity project. Paper presented at: The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) Seminar on Environmental Sustainability in Urban Centres; Perth, AU.

- Orsman B. 2014 Mar 12. Sect. A1–21. Budget warning for Brown. NZ Herald.

- Ponterotto JG. 2006. Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept ‘thick description’. The Qualitative Report. 11:538–549.

- Quesnel PL. 2006. Is local democracy sacrificed to metropolitan governance? The recent Québec experience. Paper presented at: The annual UAA 2006 meeting; Apr; Montreal, CA.

- Reingewertz Y. 2012. Do municipal amalgamations work? Evidence from municipalities in Israel. Journal of Urban Economics. 72:240–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2012.06.001

- Sancton A. 2005. The governance of metropolitan areas in Canada. Public Administration and Development; 25:317–327. doi: 10.1002/pad.386

- Schwartz H. 2009. Toronto ten years after amalgamation. Canadian Journal of Regional Science. 32:483–494.

- Slack E, Bird R. 2013. Institute on municipal finance & governance papers on municipal finance and governance. Toronto: University of Toronto. Chapter 14, Merging municipalities: is bigger better? p. 1–34.

- Smith DK. 2007. Inter-municipal collaboration through forced amalgamation: a summary of recent experiences in Toronto & Montreal. Paper presented at: The meeting of the NPC Project workshop; Vancouver, CA.

- Swianiewicz P. 2010. If territorial fragmentation is a problem, is amalgamation a solution? An East European perspective. Local Gov Stud. 36:183–203. doi: 10.1080/03003930903560547

- Thomson D, Mulligan P, Dellow T, Hood L, Evitt V. 2009. Putting the Auckland jigsaw together again: at large or ward-based council? [Internet]. Auckland: Buddle Findlay; [accessed 2017 Aug 5]. http://www.buddlefindlay.com/article/2009/05/28/putting-the-auckland-jigsaw-together-again-at-large-or-ward-based-council.

- Tomas M. 2012. Exploring the metropolitan trap: the case of Montreal. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 36:554–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01066.x

- Tracy SJ. 2010. Qualitative quality: eight ‘big-tent’ criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry. 16:837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

- Vrangbæk K. 2010. Structural reform in Denmark, 2007–09: central reform processes in a decentralised environment. Local Government Studies. 36:205–221. doi: 10.1080/03003930903560562

- Weir M, Rongerude J. 2007. Multi-level power and progressive regionalism. Berkeley (CA): University of California.

- Wollmann H. 2010. Territorial local level reforms in the East German regional states: phases, patterns, and dynamics. Local Government Studies. 36:251–270. doi: 10.1080/03003930903560612