ABSTRACT

Amongst other things, election year 2017 will be remembered for record levels of permanent and long-term migration. Immigration featured regularly in the media, both as a topic in its own right, as well as a factor associated with a deepening housing crisis in Auckland, increasing congestion on the roads in Auckland and in major tourist towns, and much faster population growth than had been anticipated. Yet immigration was not a prominent issue in either the election or during the first six months of the Labour-led Coalition Government. In this paper we assess the impact of policy changes introduced by the National Government in October 2016 and July 2017. Our analysis draws on several data sets, some of which have been withdrawn from public access regrettably. Declining net migration gains and concerns over exploitation of people on study and short-term work visas has delayed major changes in immigration policy through to June 2018.

Introduction

Immigration hit the headlines in the New Zealand Herald on successive days in late February 2018 for all the wrong reasons. Firstly, almost 200 Malaysian construction workers were found to be abusing visas which allowed them to visit but not to work in the country under a visa-waiver arrangement between Malaysia and New Zealand that dates back to 1986 (Bedford and Lidgard Citation1998; Savage Citation2018, p. A1). Secondly, a convicted immigration scammer was back selling fake citizenship certificates to people desperate to stay on in New Zealand despite their visas having expired (Tan Citation2018, p. A1). Tan (Citation2018, p. A3) reported that around 11,000 people were in New Zealand as ‘overstayers’ on expired visitor, study or temporary work visas in February 2018. He went on to note that the biggest source of overstayers is Tonga, followed by Samoa, China, India and Great Britain. The latter three are also the largest sources of immigrants approved for residence under the skilled migrant category.

Reports of visa abuse and fraud relating to immigration and citizenship invariably raise public concern about levels of immigration. New Zealand has had record numbers of visitors and temporary workers for several years in succession and there has been considerable comment in the media about high levels of immigration and population growth since 2015. Immigration policy was one of the issues on which the major parties contesting the national elections in September 2017 had quite divergent views.Footnote1 But despite record numbers of people arriving in the country with the intention of staying for 12 months or more, immigration did not become one of the ‘hot button’ political issues in the lead up to New Zealand’s national elections in late September 2017.

In the six months since the elections immigration has not featured as an issue that required immediate attention by the Labour-led coalition government despite broad agreement over the need for a reduction in net gains to the population through international migration. Immigration was number 13 in the list of Coalition Priorities in the Labour and New Zealand First Coalition Agreement signed on 24 October 2017 (New Zealand Labour Party and New Zealand First Citation2017, p. 6). Several things have contributed to this surprisingly low political profile of immigration both at the time of the election and during the initial six months of governance by the Labour-New Zealand First Coalition. In the sections that follow we examine three factors that may have contributed to a more muted debate about immigration than expected.

The first is the introduction in October 2016 and August 2017 of major changes in both skilled migrant policy and temporary work policy by the National Government. These were deliberate attempts to manage better flows of labour into the country. The second is a gradual reduction in momentum surrounding the growth in both numbers of arrivals and the net gain to New Zealand’s population of people intending to stay for 12 months or more which began around July/August 2017. The third factor, which we only touch on briefly in the conclusion to this paper, is the continued pressure on the domestic labour market by demand for skilled and semi-skilled workers in the country’s building and construction industries, the tourism and hospitality industries and the primary sector, especially horticulture, viticulture and dairy farming.

Immigration and the elections in September 2017

New Zealand’s elections were spared the negative polarising debates about immigrants that characterised recent elections in the United Kingdom, the United States of America and, to a lesser extent, Australia. Despite some major variations in the immigration policies of the main parties, the issue failed to become a significant talking point in either the media or during the three Leaders Debates in the run up to the election on 23 September.

The future of the economy (including taxation), shortages of affordable housing, pressures on the public health system, and the deteriorating quality of water in New Zealand’s rivers and aquifers were the ‘hot button’ issues. In the Herald-ZB-Kantar TNS poll of 1000 households between 13 and 17 September only 8% of those interviewed said that immigration was an issue ‘most likely’ to affect their vote in the election (Young Citation2017, p. A13). This compares with 31% stating that ‘the economy’ would influence their vote, followed by health (15%) and housing (15%).

There had been no shortage of discussion about immigration in the media or amongst researchers and policy makers during the preceding year, especially following the National-led government’s announcement in September 2016 of some significant changes to immigration policy. The major changes introduced on 1 October 2016 were, firstly, to raise the number of points required for selection into the skilled migrant category for residence approval from 140 to 160, and secondly, to reduce the capped parent, sibling and adult child category from 5000 to 2000 approvals by terminating forthwith selection of parents (Woodhouse Citation2016). The increase in points for skilled migrants was the first stage in a process to reduce the numbers of people being approved for residence who were employed in relatively low-skilled jobs. In the case of parents, siblings, and adult children the backlog of parents seeking entry under the two-tier selection system (Bedford and Liu Citation2013) was becoming excessive, especially for those who were applying under the tier 2 criteria. There have been virtually no admissions under tier 2 since the changes to policy relating to entry of parents in April 2012.

Another major change in immigration policy was announced in April 2017 when the Minister of Immigration gave notice of introducing income thresholds for both skilled migrant residence visas and essential skills temporary migration visas. In the case of the latter, the intention was to prevent people in lower-wage jobs from being able to apply for more than three years of temporary work in New Zealand before having to return home for a minimum period of 12 months (Woodhouse, Citation2017a). There was a period of public consultation over these proposed changes and some quite considerable debate in the media about the desirability or otherwise of using arbitrary income thresholds as a surrogate for skills that were in demand in New Zealand’s twenty-first century economy and society (see, for example, Collins Citation2017; Crampton Citation2017). These changes to residence and temporary migration policy were announced on 27 July (Woodhouse Citation2017b) and became effective on 28 August – less than a month before early voting began and just as the battle lines over which the election would be fought were being finalised.

Two days before the election StatsNZ released the international migration statistics for the month and year ending 31 August 2017 (StatsNZ Citation2017a). The number of arrivals for 12 months or more (including New Zealanders returning after more than 12 months overseas) was the highest ever recorded for a 12 month period – 132,153 (32,157 New Zealand citizens and 99,996 citizens of other countries). However, there had been signs in the recent monthly releases of international migration statistics that growth in what are termed permanent and long-term (PLT) arrivals was slackening.

While it is important not to read too much into small changes in the monthly PLT statistics, it can be noted that there were only 64 more PLT arrivals during August 2017 than there had been during August 2016. The overall net gain for the month (5120) was down by 320 on the monthly net gain in August 2016 (5450). The number of New Zealand citizens who returned during August 2017 (2431) was smaller than the number returning in August 2016 (2709) while the number of New Zealanders leaving during the month had increased from 2687 (2016) to 2761 (2017) (StatsNZ Citation2017a).

Although immigration did not feature in the final two weeks of political and public debate before the election, it was one of several critical points of negotiation in the formation of a coalition government following the failure of either the National or Labour parties to win enough seats to govern without the support of New Zealand First. The Coalition Agreement that was finally signed by the leaders of the Labour Party and New Zealand First on 24 October 2017 contains the following short statement on immigration:

As per Labour’s policy, pursue Labour and New Zealand First’s shared priorities to: ensure work visas reflect genuine skills shortages and cut down on low quality international education courses [and] take serious action on migrant exploitation, particularly of international students. (New Zealand Labour Party and New Zealand First Citation2017, p. 6)

What effect did changes made to residence policy in October 2016 and August 2017 have on approvals in the skilled migrant and parent/adult child and sibling streams? To what extent did raising the points required for residence from 140 to 160, along with the introduction of income thresholds and some changes in the allocation of points for work experience and education qualifications, affect the composition of the migrants selected for residence in the skilled migrant category? What has been the impact of closing the parent category on approvals for residence given the large backlog of applications that required processing? Have the changes in policy relating to essential skills visas, which came into effect in August 2017, had any noticeable impact on flows of migrants approved for temporary work in New Zealand?

Answers to these questions all have relevance for the way that migration trends have been assessed by policy makers and politicians, especially since the elections in September 2017. In the next section data from two sources are examined briefly to assess the extent to which the policy changes reduced the selection and approval of new migrants seeking residence via the skilled migrant and parent, siblings and adult children categories. Following this, the impact on migrant flows resulting from changes in temporary work policy that came into effect just before the election, are examined briefly.

Managing migration, October 2016-December 2017

At the time changes to the points system on 1 October 2016 came into effect there was quite an acrimonious debate playing out in the media over the fate of 41 Indian students whose temporary visas for study in New Zealand were found to be fraudulent sometime after they arrived to commence their tertiary education courses.Footnote2 The agent through whom they obtained their visas had submitted false financial information according to Immigration New Zealand. The students claimed that they had no knowledge of this deception but this explanation was not accepted by either the Minister of Immigration or the Minister of Tertiary Education on the grounds that the students signed the visa applications that were being submitted on their behalf. The protesters argued that the students should not be punished for the deceitful acts of their education agents.

The threatened deportation of a group of Indian international students was part of a much larger, increasingly contentious context that was placing pressure on the New Zealand government to tighten up on visa irregularities at a time when the country was experiencing record levels of immigration. Exploitation of migrant labour, including international students on visas that allowed them to work part-time or full-time depending on the nature of their education programme, had become an issue of concern to policy makers and the wider public. This concern gained greater prominence following release of a widely publicised report on worker exploitation in New Zealand (Stringer Citation2016).Footnote3 Following a visit to a region where worker exploitation was known to be an issue, an Indian Member of Parliament in the New Zealand First party, observed ‘workers are given basic rations, and they basically work like slaves, in the hope that their student visa can be converted into a work visa, and then on to permanent residence’ (Hoyle Citation2017, p. A6).

Selections from the skilled migrant pool

While no particular migrant group was being targeted in the policy changes that came into effect in October 2016, the rapid increase in temporary migration from India, largely in response to opportunities to work while gaining education qualifications and work experience that would count towards points in New Zealand’s skilled migrant selection system, had attracted the attention of policy makers and politicians (Bedford and Didham Citation2017). Since May 2010 citizens of India had consistently been the largest group selected in the fortnightly draws of expressions of interest (EOIs) from the pool of prospective applicants for residence via the skilled migrant category. In the residence approval statistics, India had consistently been the most prominent source country since 2012. Citizens of India had also become very prominent in the flows of people into New Zealand for 12 months or more on temporary visas for study and work. India has been second largest source country, after China, for students approved to study in New Zealand since 2010.

It did not take long for the policy changes that came into effect on 1 October 2016 to have an effect on the EOIs selected from the skilled migrant pool. contains comparative statistics for two 10 month periods: October 2015-July 2016 (a couple of months before the policy changes came into effect) and October 2016-July 2017 when selection from the skilled migrant pool ceased for a month while operational systems in Immigration New Zealand were being adjusted to accommodate the changes to residence and temporary work policy announced in July.

Table 1. Selections from the skilled migrant category pool, October 2015-July 2016 and October 2016-July 2017.

Raising the points threshold for selection to 160, and not selecting anyone below this threshold after 1 October 2016, resulted in a drop in EOIs selected by just under 35%, and a 41% reduction in the number of people covered by these EOIs. There were obvious increases in the shares of EOIs scoring points of 160 or more as well as the shares of Principal Applicants (PAs) who had job offers at the time they applied and who lodged their applications while in New Zealand on other visas ().

While there were some changes in the mix of migrants selected after the October policy changes came into effect, citizens of India continued to dominate by a large margin. In the period between 1 October 2016 and mid-July 2017, when the skilled migrant pool closed temporarily, 31% of all EOIs selected had been submitted by citizens of India compared with just under 27% in the October 2015-July 2016 period (). The shares of EOIs selected for citizens of China and Great Britain also rose while those for citizens of the Philippines and South Africa, as well as those from all other countries, fell.

When the comparison is made between the four months spanning September and December 2016, after the public was alerted to the October 2016 policy changes and a year before the elections, and September and December 2017, after the skilled migrant pool was re-opened in late August, and including the elections that were held in late September, rather different patterns emerge (). The number of EOIs selected fell by just over 7%, continuing the policy commitment towards reducing the number of potential residence approvals. The number of people covered by the EOIs increased slightly reflecting the much more significant change which was in the mix of citizens whose EOIs were selected. There was a significant decline in the share of citizens of India (down by 10%) while the shares of EOIs for citizens of South Africa, Great Britain and China increased. The shares of EOIs with points in excess of 180 and 200 also increased ().

Table 2. Selections from the skilled migrant category pool, September-December 2016 and September-December 2017.

The EOI selection statistics for the two September-December periods indicate that the 1 October 2016 policy changes were having the desired impact on selection from the skilled migrant pool. It would take time for these to play out in the actual approvals for residence under the skilled migrant category because selection from the pool is just the first stage in the process immigrants have to negotiate in order to gain residence in New Zealand.Footnote4 However, given that the great majority of EOIs selected are submitted on-shore by people who already have job offers, the decision to follow through on the subsequent steps in the application process would, presumably, have been made quickly. There is some evidence in the residence approval data for the years ending June 2016 and June 2017 that the changes observed in were having an effect on the actual numbers of residence approvals in the skilled migrant substream during the first six months of 2017.

Residence approvalsFootnote5

Approvals for residence before and after the October 2016 policy changes are shown with reference to four six month periods in (a and b). The first period, January-June 2016, covers approvals up to three months before the changes in policy that came into effect on 1 October 2016. The second period, January-June 2017, begins three months after these changes in policy ((a)). In the case of the first period, announcement of changes to the points threshold occurred a couple of months before the changes were introduced on 1 October and this could have encouraged an influx of new expressions of interest in applying for residence as skilled migrants. In the case of the second period, a lag of three months would have allowed some of those selected from the skilled migrant pool immediately after the policy changes to follow up on their subsequent invitations from Immigration New Zealand to apply for residence as skilled migrants.

Table 3. Skilled migrant residence approvals, 2016 and 2017.

As (a) shows, the total number of residence approvals in the skilled migrant substream between January and June 2017 was 6% smaller than during the comparable period in 2016 (). The biggest declines in approvals were for citizens of the Philippines and India, two groups that had been affected more by the increase in the points threshold for selection as skilled migrants than the citizens from the other major source countries. The impact that the policy changes had on the fortnightly draws of expressions of interest from the skilled migrant pool was quickly evident in the approval statistics.

The third period, July-December 2016, covers the three months immediately before the policy changes and the three months immediately after they were introduced. The fourth period begins nine months after the October 1 policy changes came into effect and captures the effects of further changes to the points system that were implemented in late August 2017, along with the changes to temporary migration policy that had been foreshadowed earlier in the year (Woodhouse Citation2017a). The key change was the introduction of two income thresholds into the skilled migrant visa category and some realignment of points ‘to put more emphasis on characteristics associated with better outcomes for migrants’.Footnote6

The combined effect of the changes to the skilled migrant category that came into effect in October 2016 and August 2017 was a much larger percentage decline in numbers of approvals for residence under this category when the two July-December periods are compared ((b)). Numbers of residence approvals during the second half of 2017 were 34% lower than in the same period during 2016. The smallest percentage change (9.3) was in the number of Indians approved for residence with much larger percentage declines for migrants from the other four main source countries, especially, the Philippines (51.3%) , South Africa and China (47.9% respectively).

Increasing the points threshold to 160 in October 2016 and the subsequent reduction in the number of EOIs selected from the skilled migrant pool during 2017 (), as well as the introduction of income thresholds and other amendments to the points system that came into effect in August 2017, was beginning to impact strongly on numbers approved for residence in New Zealand during the latter months of 2017. The policy changes and the smaller numbers of EOIs selected from the pool were having a desired effect of reducing the number of skilled migrant approvals.

During 2017 there was also a major decline in approvals for residence in the capped parent, sibling and adult child migrant category. It will be recalled that the policy changes in October 2016 included closing applications for residence in the parent substream completely and reducing the cap for the entire stream from 5000 to 2000. Between 1 October 2015 and 30 June 2016 a total of 4264 people were approved under the capped parent, sibling and adult child category (). Between 1 October 2016 and 30 June 2017 approvals totalled 517 – only 12% of the total approved in the comparable nine month period a year earlier. The Labour-led Coalition has made no changes in the policies introduced by the National Government in October 2016 and August 2017 so the very small numbers admitted in this capped family migration category will be reflected in what is likely to be a significant reduction in the total residence approvals for the year ending June 2018.

Table 4. Approvals under the capped parent, sibling and adult child category 1 October–30 June 2015/16 and 2016/17 compared.

Temporary migration

The changes made to policy relating to temporary work in August 2017 had not had much impact on the total number of people approved in the different temporary work substreams by the end of December 2017. The total number of people approved for temporary work in the second half of 2017 (114,285), for example, was 1.7% higher than it had been in the second half of 2016 (112,394) (). There were some quite marked variations in trends across different substreams though and two that are of particular interest in the context of transitions to residence are the job search visas and those issued for skilled work. In the case of job search visas there was an increase in numbers approved in the first six months of 2017 followed by a substantial fall in approvals in the second half of the year (). The number of approved skilled work visas, in the other hand, increased steadily across the three periods.

Table 5. Approvals in the temporary work visa substreams Three six-month periods compared, 2016–17.

The job search visa substream is closely linked with the number of international students who complete qualifications and then seek temporary work visas to stay on in New Zealand. The number of international students arriving from India, one of the most significant source countries for students in recent years, have been falling since 2015. Citzens of India comprised more than half of those approved for job search visas in each of the three six month periods shown in (a). Between 1 July and 30 December 2017 the number of citizens of India who were approved for job search visas fell by just under 38% compared with the number approved during the same period in 2016. A gradual tightening of policy relating to approved international education qualifications and their providers, that began under the National Government, is continuing under the Labour Coalition and this is beginning to impact on selected types of temporary work visa approvals.

Table 6. Temporary job search and skilled work visas approved Three six-month periods compared, 2016–17.

The same trend cannot be found for people approved on visas for skilled work. There were increases in excess of 30% in the numbers of citizens of India, China and the Philippines approved for skilled work between 1 July and 30 December 2017 compared with the same period in 2016 ((b)). By contrast, the two other major sources of skilled migrants – Great Britain and South Africa – recorded declines in numbers approved on skilled work visas. However, as noted above, across all countries, there were progressive increases in numbers approved in this substream in each six month period shown in and (b). The changes in temporary work policy introduced in August 2017 have yet to flow though into a decline in the number of approved skilled work visas.

This section has focused on evidence relating to the effect that implementation of policy changes introduced in October 2016 and August 2017 have had on selection and approval of migrants seeking particular types of visas. What about the evidence relating to flows of people across New Zealand’s international border? In the next section we examine the recent statistics relating to permanent and long-term migrants who are entering New Zealand with the intention of staying for 12 months or more, or leaving the country after spending 12 months or more in residence.

The changing role of migration in population growth

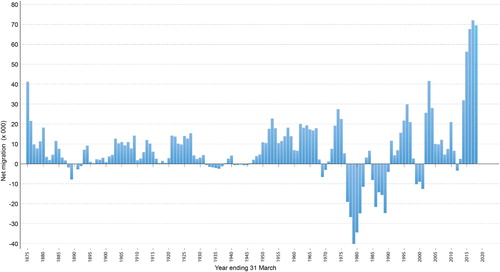

The major spike in PLT net migration gains (the balance of arrivals over departures for 12 months or more) between 2015 and 2018, that has attracted a great deal of media and political comment, is a major aberration when it is placed in the context of such net gains over the past 140 years (). There is no evidence in the historical record of sustained net migration gains in excess of 10,000 per year for periods of more than 3–5 years. Since the late 1960s there have been periods of sustained net losses rather than net gains which have caused concern about population growth being too slow rather than too fast (Spoonley and Bedford Citation2012).

The contribution of net migration to overall population growth in a given year is usually well below 50%, with 6 of the past 11 years having less than 30% of overall growth accounted for by net migration (). The main contributor in most years is natural increase – the balance of births over deaths. In the year ended June 2017, however, 72% of the estimated population growth in the previous 12 months was accounted for by PLT net migration (StatsNZ Citation2017d) (). In the light of these statistics, it is not surprising that there was concern in the months before the September 2017 elections about the contribution that international migration was making to the growth of New Zealand’s population, especially in Auckland where there is a major shortage of affordable housing and massive pressure on transport infrastructure. A long-running consultation process over the Auckland Unitary Plan (2015–2040) contributed to heightened public awareness of and concern about the impact of international migration on population growth in the city (Auckland Council Citation2018).

Table 7. Components of population growth, New Zealand 2007–2017, Years ending 30 June.

The growth in PLT arrivals have resulted in frequent adjustments to StatsNZ’s projections of population growth at national and subnational levels since 2012 (see, for example, StatsNZ Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017b, Citation2017c). Alongside this there has been a major increase in the number of tourists in recent years. Debate about the impact of international migration on population growth has, in turn, stimulated considerable interest in the increasing diversity in prospects for future population change in New Zealand’s rural and urban areas (see, for example, the various papers in a Supplementary Issue of Policy Quarterly, reporting on an in depth analysis of New Zealand’s population growth between 1976 and 2013 (Jackson Citation2017)).

Recent trends in PLT migration

Since July 2017 there have been signs that PLT net migration is starting to fall again (). By the year ended February 2018 the net migration gain had fallen to under 70,000 for the first time since September 2016 from a peak of 72,402 in the year ended July 2017. In both the New Zealand citizen component and the other citizens component of the PLT flows there have been little changes in arrivals and gradual increases in departures. The net effect of these changes has been to gradually reduce the annual net migration gain from 72,402 in the year ending July 2017 to 69,943 in the year ending February 2018 (). A trend towards lower net migration gains is now pretty well established although on-going shortages of labour across several key sectors of the New Zealand economy are ensuring the number of arrivals on temporary work visas has continued to grow.

Table 8. PLT migration, NZ citizens and other citizens Years ending July 2017-February 2018.

The gradual increase in the number of PLT departures shown in is hardly surprising since the great majority of arrivals are, in fact, on temporary work or study visas. Only a small proportion of PLT migrants are coming into the country on residence visas. Most of the 48,000–52,000 people approved for residence in New Zealand each year are approved on-shore; they are already in the country on some form of temporary visa when they gain their permanent resident status (Bedford et al. Citation2010; Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2016).

The number of overseas citizens (excluding Australians) arriving in New Zealand with the intention of staying for 12 months or more are summarised by visa type in for the past three years ending December. The two biggest changes are the decline in PLT arrivals entering on visas for study and the growth in PLT arrivals on temporary work visas. The decline in arrivals intending to study is accounted for by a halving in the number of citizens of India entering on study visas between the December 2015 year (10,833) and the December 2017 year (5827). India remained the largest source of PLT arrivals on study visas in 2017, just as it remained the main source of EOIs drawn from the skilled migrant pool in the fortnight draws (). But its dominance as a source in both these migrant streams was diminishing as the policy changes introduced from October 2016 took effect.

Table 9. Visa types for PLT arrivals (excluding NZ and Australian citizens) Years ending 30 December.

Outcomes versus intentions

Since May 2017 StatsNZ has been measuring the extent to which PLT migrants actually do spend 12 months or more in or, if they are New Zealand citizens, away from the country (StatsNZ Citation2017e, Citation2017f). Using travel histories created using international passenger data and the passport details of arrivals and departures, StatsNZ determines independently whether or not a person has resided in New Zealand for 12 months or more. They apply what they term the ‘12/16-month rule’ to establish how many people who entered in a given period actually did stay for 12 months or more (StatsNZ Citation2017e). By referring back to the arrival cards they can determine what visa they had on arrival, and thus establish how many people on study visas, for example, actually did spend at least 12 months in residence.

Because this is an outcomes-based measure, rather than a measure of intentions that migrants have when they complete their travel documentation, there has to be a time-lag of at least 16 months between arrival/departure and the determination of whether someone did spend 12 or more months in or away from the country. In the reports that have been published on this measure to date it is clear that current PLT net migration statistics are overstating the gains to New Zealand’s population through international migration. The ‘Outcomes-based net migration updated’ information release on 2 March 2018 showed that net migration in the September 2016 year was 64,500 rather than 69,954 as determined using arrival and departure data between 1 October 2015 and 30 September 2016 (StatsNZ Citation2018c).

The report also revealed that whereas during the three months between July and September 2016 11,200 people arrived with approved work visas and the intention to stay for 12 months or more, only 6600 migrants with this visa type had met the requirements of the 12/16-month rule by March 2018. In other words the PLT arrival statistics for the three months ending 30 September 2016 may have overstated by as much as 42% the numbers who had temporary work visas who actually spent 12 months or more in the country after arrival between July and September 2016.

Data derived using the ‘12/16-month rule’ for the five main source countries of immigrants during the 12 months ending 30 September 2016 are shown in .Footnote7 It is important to keep in mind when comparing the arrival and departure numbers that the data come from quite different sources. The PLT data are derived from information given on arrival and departure cards that were completed during the 12 months ending 30 September 2016. The outcomes-based data come from actual movements of people who entered and left for 12 months or more during the period 1 October 2015 and 30 September 2016 over the subsequent 12–16 months after their initial arrival or departure. The methodology is explained in StatsNZ (Citation2017e, Citation2017f).

Table 10. PLT and outcomes-based net migration Year ending September 2016.

The PLT data for citizens of India, China, Philippines and South Africa understated the net gain of people who stayed in New Zealand for 12 months or more, but significantly overstated the number of UK citizens who spent at least a year in the country. Bearing in mind that the total net gain for the year ended 30 September 2016 was smaller than the PLT net gain (StatsNZ Citation2018c), that means that the outcome-based migration of people from all countries other than the five major sources must have been smaller than the PLT net gain for these countries (). Clearly there are some interesting findings emerging from the analysis of actual movement histories of people entering and leaving New Zealand and these data offer rich possibilities for further analysis of the impact of international migration on New Zealand’s population growth and composition.

Population growth at both the national level and in several regions will continue to be heavily impacted by net migration gains for some years yet (Jackson and Brabyn Citation2017; StatsNZ Citation2017b). StatsNZ’s projections suggest that it will not be until around 2022 that net gains begin to fluctuate around 15,000 per annum, close to the level that the Labour Party specified it wished to achieve in its manifesto. Whether the Coalition Government will feel the need to dampen net migration further through new policy interventions is unclear but in March 2018 concern over immigration levels seems to have reduced. Indeed a more pressing issue, at the height of the picking and packing season for the pip fruit industry, is a seasonal shortage of labour. This, coupled with on-going labour shortages in the construction and hospitality industries, is keeping pressure on the demand for temporary work visas.

Conclusion

New Zealand’s record levels of PLT net migration have been fuelled by three priorities that the National Government had with regard to stimulating growth in the economy: increase the numbers of tourists, increase the numbers of fee-paying international students and increase the number of workers on temporary visas to meet demand for labour especially in the primary, hospitality and construction industry sectors. Rapid expansion in the dairy industry saw a significant increase in the number of Filipino migrants entering the country to meet demands for farm labour in Canterbury, Southland and the Waikato; the horticulture and viticulture industries have been pressuring Government continuously for the past five years to increase the cap on seasonal workers admitted under the Recognised Seasonal Employer scheme; the Canterbury rebuild and the demand for construction workers in Auckland has seen a significant influx of migrants with trades qualifications; the rapid expansion of tourism has created increasing demand for workers in the hospitality industry.

Average unemployment levels recorded in the Household Labour Force Survey fell to 4.0% for males and 5.0% for females in the December 2017 quarter, their lowest quarterly levels for more than two years (StatsNZ Citation2018a). On-going shortages of construction workers, and bumper crops of fruit for harvest and packing in the horticulture industry since December 2017 are contributing to keeping unemployment levels low. The number of people approved for residence was significantly lower in the July-December period in 2017 than it had been during a comparable period in 2016 () reflecting the impact of policy changes made by the previous government. These changes, coupled with the onset of a downward trend in PLT net migration gains (), a drop in numbers arriving on visas for study (), and continuation of low unemployment rates may mean pre-election statements by the Labour Party and New Zealand First about reducing levels of net migration do not re-surface in the medium term.

The two immigration-related policy initiatives that were foreshadowed by the Labour Party and the Green Party before the elections have surfaced since September 2017. The first is an increase in the number of refugees admitted under New Zealand’s official programme with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees from 750 a year to around 1500 a year by 2020. The second has been passing reference to plans by the Hon. James Shaw, leader of the Green Party and Minister for Climate Change, to have a humanitarian visa response scoped for people whose livelihoods are being destroyed by climate change, especially in the Pacific region. The latter was a subject of policy consideration within Immigration New Zealand in March 2018, and if a proposal is put out for public consultation it is likely to attract considerable local and international attention.

Debate about immigration is never far from the surface in New Zealand but, to date, the country has been spared the divisive public and political commentary that has produced some heavy-handed reactive responses by politicians in the United Kingdom and the United States of America. The evidence of ever increasing numbers of migrants arriving in and departing from New Zealand’s major international airport in Auckland, and on-going concerns about infrastructure to support the growing resident and temporary populations in the country, have resulted in increasing public ambivalence about levels of immigration. But during the election, and in the six months that followed, immigration was not an issue that attracted a lot of attention from politicians and policy makers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Richard Bedford http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9868-0686

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard Bedford

Richard Bedford

Notes

1 A useful summary of the immigration policies articulated by the six main parties contesting the election can be found at http://insights.nzherald.co.nz/article/policies-2017/. In a nutshell, the Labour Party and New Zealand First both favoured quite significant cuts in net migration gains while the Green Party prioritised increases in the quota refugee intake together with a new humanitarian visa for ‘climate refugees’ from the Pacific. The Māori Party favoured allowing skilled migrants to bring their families with them, including parents, under certain conditions as well as a scheme to attract skilled migrants in demand in the regions to work for two years with support from the community. The Act Party was opposed to cuts to immigrant numbers but wanted more conditions imposed around eligibility for some specific entitlements such as superannuation and domestic school fees.

2 The Indian student protest about their possible deportation because of the submission of fraudulent visa applications commenced in early September 2016 and attracted media attention. The Indian Newslink commented on this dispute through September and its article ‘Students facing deportation to protest again’ on 23 September contains a useful summary of the background to the case. This article can be accessed at: http://www.indiannewslink.co.nz/students-facing-deportation-to-protest-again/ (accessed 26 February 2017). By late February 2017 all of the students involved in the dispute had left the country voluntarily to avoid being compromised by enforced deportation which would have meant they could not have returned to New Zealand in the future.

3 Christina Stringer’s (Citation2016) report on worker exploitation in New Zealand was followed by several lengthy media reports on ‘modern slavery’ in New Zealand during January 2017 including one by Craig Hoyle entitled ‘Modern slavery awaits migrants’, Sunday Star-Times, p. A6-A7, 29 January 2017.

4 An analysis of New Zealand’s innovative Expression of Interest selection system for skilled migrants, which has been adopted with amendments by Australia and Canada, can be found in Bedford and Spoonley (Citation2014).

5 Time-series data on numbers of applicants for various kinds of residence and temporary visas in New Zealand have been available for some years now, in a form that can be manipulated by the user, from the Immigration section of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s website (https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/research-and-statistics/statistics). However, in January 2018 the relevant .csv files were withdrawn by Immigration New Zealand for review to ensure that individual migrants could not be identified in the data. Some summary data are still available on the website in .pdf files but these do not contain the level of detail required for this paper. Following submission of a special request for residence approvals data for the period June 2017-December 2017, staff in Immigration New Zealand did extract the relevant information from the .csv files that had been withdrawn from the website. These data have been included in . The support provided by Robert Heyes, Senior Adviser Migration Trends in the Corporate, Governance and Information Group in Immigration New Zealand is gratefully acknowledged.

6 The changes in immigration policy that the Minister of Immigration announced on 19 April 2017 included

introducing two remuneration thresholds for applicants applying for residence under the Skilled Migrant Category (SMC), which will complement the current qualifications and occupation framework. One remuneration threshold will be set at the New Zealand median income of $48,859 a year for jobs that are currently considered skilled. The other threshold will be set at 1.5 times the New Zealand median income of $73,299 a year for jobs that are not currently considered skilled but are well paid. (Woodhouse, Citation2017a)

7 Kirsten Nissen, Senior Analyst, Population Insights, StatsNZ Christchurch, provided the outcomes-based migration data for people from the five major sources of migrants. Her assistance is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Auckland Council. 2018. Auckland unitary plan. https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/plans-projects-policies-reports-bylaws/our-plans-strategies/unitary-plan/Pages/default.aspx.

- Bedford RD, Didham R. 2017. Contemporary migration to New Zealand from India: what impact will changes to temporary work visa policy have on transitions to residence via the skilled migrant category? Paper presented at: population association of New Zealand conference; July 24–25; Christchurch.

- Bedford RD, Ho ES, Bedford CE. 2010. Pathways to residence in New Zealand, 2003–2009. In: Trlin AD, Spoonley P, Bedford RD, editors. New Zealand and international migration. A digest and bibliography, number 5. Palmerston North: Massey University; p. 1–49.

- Bedford RD, Lidgard JM. 1998. Visa-waiver and the transformation of migration flows between New Zealand and countries in the Asia-Pacific region, 1980–1996. In: Lee Boon Thong, editor. Vanishing borders: the new international order of the 21st century. London: Ashgate International Publishers; p. 91–100.

- Bedford RD, Liu L. 2013. Parents in New Zealand’s family sponsorship policy: a preliminary assessment of the impact of the 2012 policy changes. New Zealand Population Review. 39:25–49.

- Bedford RD, Spoonley P. 2014. Competing for talent: diffusion of an innovation in New Zealand’s immigration policy. International Migration Review. 48(3):891–911. doi: 10.1111/imre.12123

- Collins F. 2017 Apr 21. Greater marginalization of temporary workers is not the New Zealand we want. New Zealand Herald. Sect. A: p. 26.

- Crampton E. 2017 Apr 21. Salary-based system comes at a good time to lure highly-skilled talent from Trump’s America. New Zealand Herald. Sect. A: p. 26.

- Hoyle C. 2017 Jan 29. Modern slavery awaits migrants. Sunday Star-Times. Sect. A: p. 6–7.

- Jackson N. 2017. Introduction and overview in ‘the ebbing of the human tide: what will it mean? Policy Quarterly (Supplementary Issue June 2017). 13:3–9.

- Jackson N, Brabyn L. 2017. The mechanisms of subnational population growth and decline in New Zealand 1976–2013. Policy Quarterly (Supplementary Issue June 2017). 13:22–36.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. 2016. Migration trends 2015/16. Wellington: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

- New Zealand Labour Party and New Zealand First. 2017. Coalition agreement. New Zealand Labour Party and New Zealand first. Wellington: 52nd Parliament, House of Representatives. https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2017-12/coc-17-10.pdf.

- Savage J. 2018 Feb. 24. ‘They just scarpered’. 200 Construction workers busted in immigration swoop. New Zealand Herald. Sect A: p. 1.

- Spoonley P, Bedford RD. 2012. Welcome to our world? immigration and the reshaping of New Zealand. Auckland: Dunmore Publishing.

- StatsNZ. 2014 Nov 28. National population projections: 2014(base)-2068. Hot Off The Press. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalPopulationProjections_HOTP2014.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2015 Feb 19. Subnational population projections: 2013(base)-2043. Hot Off The Press. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/SubnationalPopulationProjections_HOTP2013base.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2016 Oct 19. National population projections: 2016(base)-2068. Hot Off The Press. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalPopulationProjections_HOTP2016.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2017a Sept 21. International travel and migration: August 2017. Information Release. [accessed 2017 Sept 21]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/Migration/IntTravelAndMigration_HOTPAug17.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2017b Feb 22. Subnational population projections: 2013(base)-2043. Hot Off The Press. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]. http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/SubnationalPopulationProjections_HOTP2013base-2043.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2017c June 29. Auckland’s future population under alternative migration scenarios. Information Release. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/auck-pop-alt-migration-2017.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2017d Aug 14. National population estimates: at 30 June 2017. Hot Off The Press. [accessed 2017 Sept 24]; http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalPopulationEstimates_HOTPAt30Jun17.aspx.

- StatsNZ. 2017e. Defining migrants using travel histories and the ‘12/16-month rule. Wellington: StatsNZ. [accessed 2018 March 13]; https://www.stats.govt.nz/methods/defining-migrants-using-travel-histories-and-the-1216-month-rule.

- StatsNZ. 2017f. Outcomes versus intentions. Measuring migration based on travel histories. Wellington: StatsNZ. [accessed 2018 March 13]; https://www.stats.govt.nz/methods/outcomes-versus-intentions-measuring-migration-based-on-travel-histories.

- StatsNZ. 2018a Feb 7. Labour market statistics: December 2017 quarter. Information Release. [accessed 2018 Feb 26]; https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/labour-market-statistics-december-2017-quarter.

- StatsNZ. 2018b Feb 2. International travel and migration: December 2017. Information Release. [accessed 2018 March 13]; https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/international-travel-and-migration-december-2017.

- StatsNZ. 2018c March 2. Outcomes-based net migration updated. Information Release. [accessed 2018 March 18]; https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/outcomes-based-net-migration-updated.

- Stringer C. 2016. Worker exploitation in New Zealand: a troubling landscape. Auckland: University of Auckland Business School. Report for The Human Trafficking Research Coalition. Available at: https://media.wix.com/ugd/2ffdf5_28e9975b6be2454f8f823c60d1bfdba0.pdf.

- Tan L. 2018 Feb 26. $150: fake citizenship certificates for sale. New Zealand Herald. Sect A: p. 1.

- Woodhouse M. 2016 Oct 11. NZRP [New Zealand Residence Programme] changes to strike the right balance. Press release by the Minister of Immigration. [accessed 2017 Sept 23]; https://beehive.govt.nz/release/nzrp-changes-strike-right-balance.

- Woodhouse M. 2017a Sept 23. Changes to better manage migration. Press release by the Minister of Immigration. [accessed 2017 Sept 23]; https://beehive.govt.nz/release/changes-better-manage-immigration.

- Woodhouse M. 2017b Sept 23. Changes to temporary work visas confirmed. Press release by the Minister of Immigration. [accessed 2017 Sept 23]; https://beehive.govt.nz/release/changes-temporary-work-visas-confirmed.

- Young A. 2017 Sept 22. Economic issues top list of main concerns. New Zealand Herald. Sect A: p. 13.