ABSTRACT

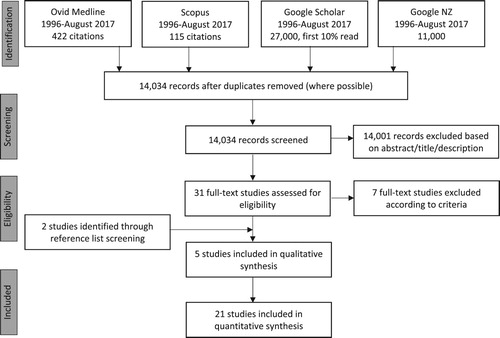

New Zealand is considering a change in law to permit euthanasia and/or assisted dying (EAD). We reviewed 20 years of research to investigate New Zealanders’ attitudes towards EAD, including those of health professionals. A systematic search was conducted using relevant databases. We identified 21 quantitative and 5 qualitative studies. For quantitative data, descriptive analyses were used to examine any demographic patterns that influenced attitudes. We reviewed the circumstances under which people think that EAD should be accessible, and which forms of EAD they support. All public attitude studies reported that the majority (68%) of respondents support EAD. There are few statistically significant demographic associations with attitudes toward EAD; exceptions include religiousity, educational attainment, and some ethnic groups. Health professionals’ attitudes varied by speciality. Qualitative research was analysed for reoccurring themes; ‘feeling like a burden’ was evident across most studies. We conclude from the quantitative research that public attitudes are stable and a majority are open to legislative change. However, the qualitative research reveals the complexity of the issue and indicates a need for careful consideration of any proposed law changes. It is unclear what safeguards people expect if the law changes. We found little research involving vulnerable and marginalised populations.

Introduction

Euthanasia and assisted dying (terminology discussed below) are known to provoke strong legal, ethical and political debate. There are a variety of regulations in place surrounding these practices in various countries around the world. As of 2018, some form of euthanasia/assisted dying (EAD) could be practiced legally in Canada, Belgium, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, and Colombia, and in the US states of Oregon, Washington, Vermont, Montana, Colorado, California, and Washington, DC; EAD is also decriminalised in Switzerland (Emanuel et al. Citation2016). Likewise, Hawai’i and Victoria, Australia, have recently passed EAD legislation (Victorian Parliamentary Library & Information Service Citation2017; Office of the Governor Citation2018). At present, all forms of EAD are illegal in New Zealand (NZ). While the debate has been ongoing for several decades, there has been increased impetus for change in recent years.

There have been three unsuccessful attempts in NZ to pass legislation to allow EAD through private members’ bills: one in 1995 was voted down 61–29; another in 2003 also failed by 60–58 votes, and a third bill that was withdrawn from the ballot in 2014 (Health Committee Citation2017).

EAD was brought to the fore in NZ in 2015 by the case of Seales v Attorney General. Lawyer Lecretia Seales, who was dying of brain cancer at the time, sought confirmation from the High Court as to whether or not her doctor would be acting unlawfully in administering or prescribing a lethal drug (Vickers Citation2016). Seales also asked the court to clarify whether her inability to access EAD was a breach of her rights under the NZ Bill of Rights Act 1990. Although Justice Collins ruled the issue needed to be dealt with in the House of Representatives, the case attracted considerable media coverage and stimulated much public debate.

In addition, the parliamentary Health Committee received a petition in 2015 signed by 8975 New Zealanders, requesting that it ‘investigate fully public attitudes towards the introduction of legislation which would permit medically-assisted dying in the event of a terminal illness or an irreversible condition which makes life unbearable’ (Health Committee Citation2017, 5). The Committee held an inquiry, seeking submissions from the public. The inquiry did not formally recommend or oppose the legalisation of EAD, but instead presented a summary of information and arguments both for and against it (Health Committee Citation2017). One analysis by an opposition group found that 77% of submissions were opposed to such legalisation (Care Alliance Citation2017). Public opinion about EAD has been surveyed a number of times in NZ by various sources, and these surveys appear to indicate a majority support. In 2017, the ACT Party's David Seymour's End of Life Choice Bill was drawn from the Members’ Ballot. This bill aims to give ‘people with a terminal illness or a grievous and irremediable medical condition the option of requesting assisted dying’ (End of Life Choice Bill Citation2017, 1). It passed its first reading (77–44 votes) in December 2017 and is now being considered by the Justice Select Committee. This committee has received over 35,000 submissions, which is the highest number ever received in response to any bill (Justice Committee Citation2018).

Given the current relevance of EAD in NZ and the conflicting findings, we undertook the first review of the extant research focussing explicitly on New Zealanders’ attitudes toward this issue. Our aim in this paper is not to enter the ethical debate on EAD, rather to understand the current landscape and to identify areas where more research is needed. The research team does not share a collective position as to whether or not the law should be changed.

Definitional issues

There are a variety of terms used to refer to the intentional act of hastening or causing death. Here we use the acronym EAD as the most general descriptor, while acknowledging that this term may not be universally acceptable. We use the term ‘euthanasia’ to mean a lethal injection that is administered at the voluntary request of a competent patient by a doctor or a nurse practitioner. ‘Assisted dying’ means that a doctor provides a prescription for lethal medicine at the voluntary request of a competent patient; the patient then self-administers the prescription at the time of their choosing.

Method

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted by JY with advice from a subject librarian using the electronic databases Ovid Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar and Google NZ using terms from Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and subheadings, as well as keywords (see ).

Table 1. Final database search strategy.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Research articles published in English between 1996 and August 2017 were included. Commentaries, editorials, ethical and legal arguments, and position statements were excluded, so as to focus on empirical work that examined New Zealanders’ attitudes toward EAD. See .

Critical appraisal

We did not use tools such as the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (Citation2017) to identify study quality, instead opting to include all identified research irrespective of methodological quality or systematic bias. Our intention was to make the review as comprehensive as possible, and to identify where interpretative or methodological questions arose.

Analysis

We grouped the results according to quantitative and/or qualitative methodology. Meta-analysis was not achievable as studies did not use comparable data points. We explored support for, and opposition to, EAD in relation to a number of demographic factors, and among different health professions. We did so by presenting available data from a number of studies that have been conducted over time, and by drawing comparisons where possible. We further examined overall support for, and opposition to, EAD here in NZ, and support and opposition according to ethnicity and to political party preference; we did so by collating available data using weighted averages (JY, AG with advice from CJ). Further, we reviewed the circumstances under which people think that EAD should be accessible, and which forms of EAD are supported (JY, AG with advice from CJ). The small body of qualitative research was read and analysed for recurrent themes, and these were compared and contrasted similar to narrative summary (Dixon-Woods et al. Citation2005) (JY, RE, SW).

Results

In total, five qualitative and six quantitative research articles and 15 polls/surveys were identified. All 17 studies of public attitudes reported on the percentage of respondents that were supportive of EAD. In the studies that have been conducted, it is not always clear whether respondents were being asked to consider euthanasia or assisted dying.

Public support and opposition

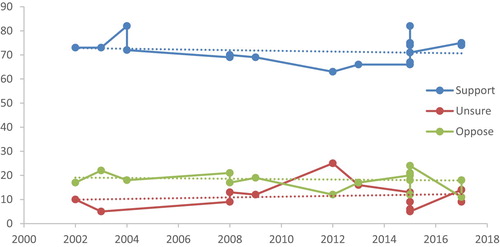

A number of NZ studies have examined public opinion on EAD. Across all polls and surveys, there was found to be an average (weighted) of 68.3% support (range 63–82%) for EAD (Gendall Citation2002, Citation2008, Citation2009; Colmar Brunton Citation2003, Citation2008, Citation2015, Citation2017; Beautrais et al. Citation2004; Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Horizon Research Citation2012, Citation2017; Key Research Citation2013; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Rae et al. Citation2015; Reid Research Citation2015; Research New Zealand Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). 14.9% (range 12–24%) on average oppose legalisation, while 15.7% (range 5–25%) are neutral or unsure. A total of 36,304 people were surveyed. The questions employed typically ask respondents whether doctors should be allowed to assist a patient to die, at that patient's request, when the patient's condition is terminal or incurable and/or that they are in pain. Appendix 1 lists questions used, results, number of respondents, response rates and the mode of survey delivery. The same question- ‘Suppose a person has a painful incurable disease. Do you think that doctors should be allowed by law to end the patient's life if the patient requests it?’, has been asked seven times across studies, with the results indicating between 63 and 74% support (see Appendix).

Given that there appears to be strong public support for EAD, that a number of polls have been conducted in the last 20 years, and that support has increased, plateaued and decreased in international regions (Emanuel et al. Citation2016), we examined NZ public support, opposition and uncertainty over time: as shown in , all three appear to be relatively consistent.

Demographic factors

Several studies reported on support and opposition for EAD in relation to demographic factors, including gender, religiosity, age, ethnicity, income, deprivation, education, occupation, personality traits, residential location, and political orientation. The variety of reporting methods and measures limits comparison.

Several studies found overall support and opposition to be highly similar according to gender (Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Gendall Citation2008; Horizon Research Citation2012, Citation2017; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Research New Zealand Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). One study found stronger support among men, as compared to women, for assisted dying (Gendall Citation2002). Other studies did not differentiate between genders in terms of support for, or opposition to, EAD.

Two studies tested for an association between religiousity and attitudes towards EAD, with both reporting that those with religious beliefs were less likely to support EAD; a moderate (Rae et al. Citation2015) to strong associated was found (Lee et al. Citation2017). Other studies did not explore religiosity.

Results varied when examined by age group. Several studies found that older respondents are significantly less likely to support EAD (Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Lee et al. Citation2017). Other studies revealed a similar trend, although statistical significance was either not reached (Research New Zealand Citation2015), or was not reported on (Horizon Research Citation2012). Other studies found higher support for EAD among older respondents (Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Horizon Research Citation2017), while one study did not find a significant difference across the life course (Rae et al. Citation2015). A number of surveys found majority support (i.e. greater than 50%) in every age group (Gendall Citation2002, Citation2008; Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Horizon Research Citation2012, Citation2017; Curia Market Research Citation2015). A study among 25 year olds found the most support (82%) for EAD under certain circumstances (Beautrais et al. Citation2004). The only study to examine support for ‘non-doctor assisted dying’, (i.e. assisted by family) found that support was higher among those under 50 years of age, as compared to those aged 50+ (Gendall Citation2002).

When examined according to ethnicity, results were also variable. features those studies that report percentages, according to ethnicity, in support and opposition to EAD in the case of terminal illness. Support among NZ Europeans is consistently at or above 65% across all surveys. The average support across all non-Māori is 67.2% while support among Māori is slightly lower at 63.5% (see ). One study found no significant association between being of Māori ethnicity and support for EAD (Lee et al. Citation2017), while another found that an unexpectedly high proportion of Māori were supportive (93%) (Rae et al. Citation2015). Although both studies involved a nationally representative sample from the electoral roll, the response rates were only around 17% (see Appendix for more detail). A single study revealed that, among Māori, support for euthanasia (61%) was higher than support for non-doctor assisted dying (56%) (Research New Zealand Citation2015). Some studies reported that higher numbers of Pacific Islanders (Horizon Research Citation2012; Citation2017) and Asians (Horizon Research Citation2012, Citation2017; Colmar Brunton Citation2017) were unsure about EAD, as compared to other ethnic groups. The NZ Attitudes and Values Study (NZAVS) (Lee et al. Citation2017) found that those of Pacific or Asian ethnicity were less supportive than Europeans. One study found no statistically significant differences by ethnicity (Research New Zealand Citation2015) and another found a weak association between ethnicity and desire for legalisation.(Rae et al. Citation2015).

Table 2. Support and opposition for euthanasia/assisted dying by ethnicity.a

There are mixed results as to the effect of education, deprivation, income, and employment on support and opposition for EAD. This may be due to the various study measures used, and in some cases because of relatively small population sample sizes. Three studies found that people with higher educational attainment (i.e. Bachelor's degree or higher qualification) appear more likely to oppose EAD (Horizon Research Citation2017), with two of these reporting significant differences between subgroups (Research New Zealand Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). Several studies found that those living in areas of higher deprivation were more likely to oppose EAD than people living in less deprived areas (Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). In two surveys, there does not appear to an association between income and support for, or opposition to, EAD (Research New Zealand Citation2015; Horizon Research Citation2017). Only one study found significantly higher than average support among those earning $40–50,000 per year, as compared with all other income bracket sub-groups (Colmar Brunton Citation2008). In examining responses according to occupation, one study found that support for EAD among clerks (80%) and among agricultural and fishery workers (85%) was significantly higher than average; it was also found that unemployed and retired people were significantly less supportive of EAD (58%), as compared with other sub-groups (Colmar Brunton Citation2008). The same study demonstrated significantly higher than average support for EAD among the self-employed, when examining responses according to employment status alone.

Other factors measured were personality traits, regional variances and political party support. The NZAVS examined the ‘Big-Six’ personality traits in relation to attitudes towards EAD: greater support was found among those who scored high on extraversion, conscientiousness and neuroticism, whereas people who exhibited high agreeableness and honesty-humility were less supportive (Sibley Citation2012; Lee et al. Citation2017). The authors of the study claim that this association between honesty-humility ‘is characterised by morals linked to concern for the wellbeing of others’ (Lee et al. Citation2017, 14). In terms of support according to regional variances, those living in rural areas were found to be more supportive of EAD, when rurality is defined as being ‘non-urban’ (Curia Market Research Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). Although Wellingtonians were less likely to support EAD than those in other regions (Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Curia Market Research Citation2015), there does not appear to be an overall relationship between attitudes toward EAD and the size of an urban area (Curia Market Research Citation2015). shows attitudes according to political party preference. Aggregated data reveals little variation with support for EAD just above two thirds across almost all voter groups (Horizon Research Citation2012, Citation2017; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Reid Research Citation2015). However, the NZAVS (Lee et al. Citation2017) found there to be less support among those who are more politically conservative.

Table 3. Support, opposition and unsure for euthanasia/assisted dying by political party preference.a

Support and opposition among health professionals

A number of studies have examined health professionals’ views on EAD (Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Havill Citation2015; Malpas and Mitchell Citation2017; Malpas et al. Citation2015; Taylor Citation2015; Sheahan Citation2016; Oliver et al. Citation2017).

A 2004 study (n = 120; 40% response rate[RR]) of justifiability and legality of actions around assisted dying showed that 41% of GPs thought it was appropriate, upon request from a patient with a terminal illness and intractable pain, to supply drugs to hasten death (Mitchell and Owens Citation2004). Twenty-six percent of GPs were unsure about the legality of supplying information and drugs so as to hasten death; 34% considered it ethically justifiable to help a patient to take drugs to hasten death, and 30% considered it ethically justifiable to give a lethal injection in this case.

Two 2015 surveys were highly similar among GP respondents: almost half supported, and nearly half opposed a law change (n = 110, no RR) (Havill Citation2015; Taylor Citation2015). One specified the patient has end-stage terminal disease or is suffering from irreversible unbearable suffering and the request from a competent adult (n = 78, RR = 39%) (Havill Citation2015). Similar results were found for the allowance of assisted dying provisions within advanced care directives, though support dropped to 40% with regard to dementia (Havill Citation2015). More recent research has shown that some 37% of doctors (n = 298) and 67% of nurses (n = 474) are supportive of legislative change to allow assisted dying for mentally competent patients who make clear and repeated requests; conversely, 58% of doctors and 29% of nurses were found to oppose, and 5% were unsure (Oliver et al. Citation2017). A response rate was not provided, likely due to diverse recruitment strategies, though respondents were demographically representative of their colleagues. Of those who were supportive, the majority were willing to partake in assisted dying where the patient's circumstances clearly aligned with eligibility criteria (Oliver et al. Citation2017).

A 2016 study (n = 165; 43% RR) found very low support for legalising euthanasia (7.1%) and assisted dying (8.9%) among Australasian palliative care specialists and GPs with palliative care practice interests: 80.1% were opposed and 15.9% were undecided about euthanasia; 75.2% were opposed and 15.9% were undecided about assisted dying (Sheahan Citation2016). The values that most informed these attitudes, as selected from a list, were: ‘the physician's professional obligation to do no harm’ (28%), ‘the community interest in protecting life and not intentionally taking life’ (26%) and ‘spiritual belief in the intrinsic value or sanctity of human life’ (15%). Respondents’ views were mixed with regard to the potential impact that legalisation would have on palliative care.

Euthanasia vs assisted dying

Among studies that specifically differentiated between euthanasia and assisted dying, support for a doctor to end a person's life upon request was 68.3%, whereas support for assistance from someone other than a doctor (e.g. family) was only 48.0% (Gendall Citation2002; Citation2008; Horizon Research Citation2012; Research New Zealand Citation2015). Opposition to assisted dying is stronger than to euthanasia (19.2% vs. 16.1%) and fewer respondents are unsure when considering assisted dying (6% vs 13.8%) (Gendall Citation2002; Citation2008; Horizon Research Citation2012; Research New Zealand Citation2015). Of those who support legalisation, 67% want both euthanasia and assisted dying to be legal; 19% think that only assisted dying should be legal, while 13% believe that only euthanasia should be legal (Rae et al. Citation2015). Among palliative care specialists there was slightly higher support for assisted dying (8.9%) than euthanasia (7.1%) (Sheahan Citation2016). Very few palliative care specialists were willing to participate in euthanasia (2%) or assisted dying (4.5%) (Sheahan Citation2016). We calculated (and confirmed with authors) that of the total sample of NZ doctors (n = 298), 34.5% would be willing to prescribe the lethal medication, and 28.5% would administer the medication if it was legal to do so (Oliver et al. Citation2017).

Criteria for when EAD should be accessible

Questions in polls typically mention eligibility criteria for EAD, such as prognosis or suffering (see Appendix), but it can be difficult to infer which factors respondents view as being appropriate or important. Several studies have explored this question directly.

One study explored how participants (n = 677; 17% RR) weighted different factors (e.g. age, prognosis, and nature of suffering) in situations where assisted dying might be considered (Rae et al. Citation2015). The patient's age and life expectancy did not significantly influence responses; the type of suffering (i.e. pain or loss of dignity) did, however, have an impact. Respondents indicated that EAD is most appropriate for loss of dignity scenarios, even when pain is controlled (Rae et al. Citation2015). As expressed in two studies, treatability of pain is a factor in determining whether or not participants support EAD, suggesting that EAD is viewed by some as a last resort (Gendall Citation2009; Rae et al. Citation2015). It should be noted, however, that scenarios that mentioned pain did not normally address treatments, side effects, prognosis, or impact on quality of life (Gendall Citation2002, Citation2008, Citation2009; Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Research New Zealand Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017).

In two studies, EAD for paralysis and permanent dependence was supported by 44–49% of respondents (Gendall Citation2009; Rae et al. Citation2015), while 18% were unsure and 39% were opposed (Gendall Citation2009). Another study, which asked about a person who had irreversible unbearable suffering which may not cause death in the immediate future (motor neurone disease, for instance), reported that support for EAD was much higher than opposition (66% and 14%, respectively) (Horizon Research Citation2017).

Few studies have explored decision-making capacity itself as a qualifying factor. In a single study, in response to a question about which criteria were necessary for a person to qualify for EAD, 46% of respondents indicated that the person should not be depressed or mentally ill (Rae et al. Citation2015). While respondents may have presumed that depression or mental illness impair one's capacity to make decisions, this is not necessarily the case (Bharucha et al. Citation2003). In another study, 67% support was found for adults being allowed to write, sign, and register an advanced directive to terminate their life in the case of mental incompetence, while 12% were opposed and 21% were either unsure or neutral (Horizon Research Citation2012).

Qualitative research

Qualitative research exploring EAD has been conducted with healthy adults (Ryan Citation2014), including some older adults (Malpas et al. Citation2012, Citation2014), kaumātua Māori (elders) (Malpas et al. Citation2017), and GPs (Malpas and Mitchell Citation2017).

Healthy older New Zealanders (n = 11) oppose EAD due to religious beliefs and concerns about a ‘slippery slope’, (i.e. potential abuse and a duty to die for fear of becoming a burden on others) (Malpas et al. Citation2014). Healthy older participants (n = 11) support EAD for various reasons, including anticipated incapacity, dependency on others and becoming a burden, preserving dignity, and respecting a person's autonomy and right to choose (Malpas et al. Citation2012). Personal experiences with health care and the deaths of others influenced participants’ views about EAD (Malpas et al. Citation2012, Citation2014). In another study, both Māori and non-Māori (n = 28) healthy adult participants explained their positions regarding EAD with ideas relating to burden, duty, reciprocity, and deservingness (Ryan Citation2014). This was inherently tied to how people perceived themselves and wished to be perceived by others.

Malpas et al. (Citation2017) using a qualitative kaupapa Māori approach, conducted focus groups with kaumātua Māori (n = 20) about EAD. Their primary concerns were the effects of EAD on hauora (wellbeing) and tikanga (customs and traditional values), particularly with respect to the interruption of the dying process – wairua (spirituality) and kawa (protocol and etiquette) for whānau (extended family), the dying person and Te Ao Māori (the Māori world). Some participants thought there was a possibility for EAD to be guided by tikanga, and one kaumātua noted practices of hastening death in recent Māori history. Seeing their whānau die in pain oriented some kaumātua to the possibility that EAD was acceptable. Conversely, others saw it as a destructive force that could strip the mana from a whānau. Participants stressed that whānau must be involved in decision-making processes. The authors acknowledge that findings may not represent all Māori, particularly those who have less to do with Te Ao Māori. Other research also suggests this may be the case (see ).

The theme of being a burden is evident across qualitative research involving healthy participants (Malpas et al. Citation2012, Citation2014; Ryan Citation2014). Partipants believed they could be an encumbrance on others if their death was protracted, and some did not want to rely on others for care (Malpas et al. Citation2012). Respondents also expressed that they did not want family members to watch them suffer. Some relayed concerns about no longer contributing to society in a meaningful way, and about the cost of care and the desire to leave an inheritance (Ryan Citation2014). Burden was reconceptualised as intergenerational reciprocity and the value of kaumātua by Māori participants. Burden was not identified as a theme in the kaumātua Māori study (Malpas et al. Citation2017).

One mixed-method study invited GPs (n = 9) to participate in an anonymous phone interview after having completed an end of life medical decision-making survey (Malpas and Mitchell Citation2017; Malpas et al. Citation2015). GPs who responded had mixed views. Communication and relationships were identified as key themes, and patient autonomy was paramount for some. There were concerns about potential abuse; adverse effects on doctors and on the profession; patients changing their minds or feeling as if they are a burden; and the limits of palliative care to relieve suffering (Malpas and Mitchell Citation2017).

Discussion

Our review of the quantitative research has shown that support and opposition for some form of EAD among New Zealanders is stable across time: 68.3% and 14.9%, respectively, with 15.7% unsure. This finding is consistent with international research (Sikora and Lewins Citation2007; Ipsos MORI Citation2015; FactCheck Citation2017). Support has grown in Western Europe but is variable in the United States (Emanuel et al. Citation2016). Support and opposition vary across health professional specialities, with those who work exclusively with the dying being most opposed. Most palliative care in NZ is provided by non-specialists, such as GPs, who are more supportive of EAD than palliative care specialists (Ministry of Health Citation2017). The results of studies involving NZ health professionals are similar to those in other countries (Sheahan Citation2016; Oliver et al. Citation2017). Findings relating to healthcare professionals’ views must be interpreted in light of research that suggests one third of NZ doctors may not be willing to answer honestly when asked about EAD because of perceived legal implications, disapproval from others, and suspicion about the intent of the research (Merry et al. Citation2013).

In terms of the relationship between demographic factors and EAD, no differences were found between genders, and results according to age appear to be mixed. Of all indicators of socio-economic status (i.e. income, deprivation, education, occupation) only educational attainment was statistically significant, with lower educational attainment being associated with higher support for EAD. Those living rurally (i.e. non-urban) were found to be more supportive of EAD.

Though findings are limited by a lack of reporting on major ethnic groups (Beautrais et al. Citation2004; Colmar Brunton Citation2008; Citation2017; Research New Zealand Citation2015), there is evidence that attitudes among NZ Europeans and Asians are consistent across studies. The finding that religious beliefs are associated with opposition to EAD aligns with results from Australia, the UK, and some European countries (Cohen et al. Citation2006; Sikora Citation2009; Danyliv and O’Neill Citation2015). Some researchers have concluded that demographics are poorly associated with attitudes (Rae et al. Citation2015; Colmar Brunton Citation2017), while others have found reliable demographic differences (Lee et al. Citation2017). Internationally, the circumstances under which health professionals, lay people, and patients find the practice of EAD to be acceptable may vary depending on demographic characteristics, values and location (Teisseyre et al. Citation2005; Cohen et al. Citation2006). Historical, political and cultural factors also play a role (Cohen et al. Citation2006), which complicates international comparisons.

Among New Zealanders, support for EAD also appears to vary according to patient circumstances. It seems that pain and a life-limiting prognosis are important conditions for support. Similar results are found among Australians (Sikora and Lewins Citation2007). Data from Oregon and Washington show that primary motives for choosing assisted dying are loss of autonomy and dignity, and being less able to engage in enjoyable activities. Inadequate pain control is a motivating factor in only 33% of cases (Emanuel et al. Citation2016).

Qualitative studies produced somewhat different results as compared with quantitative studies. Qualitative studies convey cautiousness and offer a more nuanced account of the reasons people have for supporting or opposing assisted dying. Both EAD proponents and opponents are shown to have concern for the wellbeing of individuals. The theme of ‘feeling like a burden’ to others was apparent across most qualitative studies. A NZ study of end of life care preferences among people of advanced age found that the top priority for participants was ‘not being a burden to my family’ (Gott et al. Citation2017). In the US, ‘burden on others’ has been identified as an end of life concern in less than half of assisted deaths (Emanuel et al. Citation2016). Several systematic reviews have found that self-perceived burden is a significant problem for people with terminal illness, and that this contributes to poor quality of life and to unbearable suffering (McPherson et al. Citation2007; Hendry et al. Citation2013; Rodríguez-Prat et al. Citation2017). Feeling like a burden is related to dignity, identity and loss of social role (McPherson et al. Citation2007; Hendry et al. Citation2013; Rodríguez-Prat et al. Citation2017). Culturally bound notions of independence, autonomy and reciprocity (Hockey and James Citation1993) may help to explain why this theme did not arise in the study with kaumātua Māori. On the other hand, not being a burden to one's family was the top priority among both Māori and non-Māori participants (Gott et al. Citation2017).

There were notable methodological limitations in several of the studies identified, including study design, low response rates (perhaps due to the sensitive nature of the topic and the use of the electoral roll recruitment method), response bias, representativeness, framing effects, and ambiguity of questions and responses. These limit the validity of the findings. With the exception of several studies (Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Horizon Research Citation2012; Rae et al. Citation2015), many studies assessed attitudes using a single item only, which means we do not know about the conditions and safeguards that participants think are important (Colmar Brunton Citation2015, Citation2017; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Reid Research Citation2015; Lee et al. Citation2017). Despite this, estimates were similar across studies.

While most surveys reported that their samples were either stratified or weighted to ensure representation of the NZ population, some did not (see Appendix 1). Other polls did not provide the information required so as to evaluate the reliability and validity of findings (Beautrais et al. Citation2004; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Taylor Citation2015). Furthermore, all quantitative studies were cross-sectional in nature; it is therefore not known if individuals’ views are consistent over time.

Research in this field can be further impacted by framing effects (Parkinson et al. Citation2005; Marcoux et al. Citation2007) Many studies, for instance, mentioned only that a person had an incurable disease, without specifying how close to death they were (Gendall Citation2002, Citation2008, Citation2009; Horizon Research Citation2012; Key Research Citation2013; Curia Market Research Citation2015; Research New Zealand Citation2015; Sheahan Citation2016; Lee et al. Citation2017). There is debate over what terms such as incurable or terminal mean (Hui et al. Citation2014). More than one non-committal response option was occasionally given, rendering answers more ambiguous (Horizon Research Citation2012; Key Research Citation2013; Curia Market Research Citation2015). Two studies provided respondents with medical treatment options and asked lay participants to decide on the most appropriate course of action for the doctor, which assumed a certain level of knowledge about such practices (Mitchell and Owens Citation2004; Rae et al. Citation2015). Social norms may also influence doctors responses to questions about EAD (Merry et al. Citation2013). Bias may also appear in authors’ interpretation and reporting of results.

It is difficult to draw firm conclusions because of the variety of reporting methods, measures, and parameters used within studies. Polls and surveys are useful for investigating attitudes toward policy at the broader level. These do not, however, provide information about context-specific elements that must be considered when deciding whether or not EAD is appropriate in a particular case. Most glaringly absent is research examining the attitudes of New Zealanders who are approaching the end of life or people with disabilities (see Shakespeare Citation2013 for discussion). Some overseas studies have been conducted on the wish to hasten death and the model developed from this research could be applied to the NZ context (Rodríguez-Prat et al. Citation2017). No NZ or international studies have tested whether receiving detailed information about the arguments both for and against legalisation influences participants’ views.

Conclusion

Public interest in EAD in NZ does not appear to be abating. It seems that a majority of the public are open to the possibility of legislative change. It is less clear what form(s) of EAD New Zealanders think should be available, or when and how it should be accessible, though some form of regulation is expected (Horizon Research Citation2012; Rae et al. Citation2015; Oliver et al. Citation2017). Quantitative research serves to highlight associations between religiousity, educational attainment, and some ethnic groups but no other demographic variables and attitudes toward EAD. The studies of health professionals’ attitudes illustrated varied support among specialities. Qualitative research, on the other hand, provides a more nuanced account of people's concerns about EAD, and details why others consider it appropriate. Specific research is needed to understand the views of potentially vulnerable populations, such as people with disabilities, and to evaluate which conditions and safeguards New Zealanders believe should be available.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Richard German for database assistance, and to Reid Research, Key Research, Voluntary Euthanasia Society, Dr Malpas, and Colmar Brunton for providing data. We are grateful to Otago Medical School and Division of Health Sciences Collaborative Research Grants for funding this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jessica Young http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8173-0552

Richard Egan http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9964-6175

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beautrais AL, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. 2004. Knowledge and attitudes about suicide in 25-year-olds. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 38(4):260–265. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01334.x

- Bharucha AJ, Pearlman RA, Back AL, Gordon JR, Starks H, Hsu C. 2003. The pursuit of physician-assisted suicide: role of psychiatric factors. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 6(6):873–883. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654758

- Care Alliance. Health select committee: 77% of submissions oppose euthanasia. 2017. [accessed 2017 8 March]. http://carealliance.org.nz/health-select-committee-77-of-submissions-oppose-euthanasia/.

- Cohen J, Marcoux I, Bilsen J, Deboosere P, van der Wal G, Deliens L. 2006. European public acceptance of euthanasia: socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 european countries. Social Science & Medicine. 63(3):743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.026

- Colmar Brunton. 2003. Poll on euthanasia. Wellington: Colmar Brunton.

- Colmar Brunton. 2008. Voluntary Euthanasia Society of New Zealand. Wellington: Colmar Brunton.

- Colmar Brunton. 2015. One News Colmar Brunton poll. Wellington: Colmar Brunton.

- Colmar Brunton. 2017. One News Colmar Brunton poll. Wellington: Colmar Brunton.

- Critical appraisal skills programme (CASP). 2017. CASP; [accessed 2017 6 June]. http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists.

- Curia Market Research. 2015. Euthanasia poll. Wellington: Curia Market Research.

- Danyliv A, O’Neill C. 2015. Attitudes towards legalising physician provided euthanasia in Britain: the role of religion over time. Social Science & Medicine. 128:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.030

- Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. 2005. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110

- Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. 2016. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Journal of the American Medical Association. 316(1):79–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8499

- End of Life Choice Bill. 2017. Wellington: New Zealand Parliament. http://www.legislation.govt.nz/bill/member/2017/0269/latest/DLM7285905.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_end+of+life_resel_25_a&p=1.

- Factcheck Q&A: do 80% of australians and up to 70% of catholics and anglicans support euthanasia laws? 2017. [accessed 2017 7 September]. http://theconversation.com/factcheck-qanda-do-80-of-australians-and-up-to-70-of-catholics-and-anglicans-support-euthanasia-laws-76079.

- Gendall P. 2002. Massey survey shows support for euthanasia. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Gendall P. 2008. Massey survey shows support for euthanasia. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Gendall P. 2009. Massey survey shows support for euthanasia depends on circumstances. Palmerston North: Massey University. http://www.massey.ac.nz/massey/about-massey/news/article.cfm?mnarticle=euthanasia-support-dependent-on-circumstances-29-03-2010.

- Gott M, Frey R, Wiles J, Rolleston A, Teh R, Moeke-Maxwell T, Kerse N. 2017. End of life care preferences among people of advanced age: LiLacs NZ. BMC Palliative Care. 16(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12904-017-0258-0

- Havill J. 2015. Physician-assisted dying—a survey of waikato general practitioners. New Zealand Medical Journal. 128(1409):70–71.

- Health Committee. Petition 2014/18 of hon maryan street and 8,974 others. 2017. Wellington: House of Representatives; [accessed]. https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/SCR_74759/4d68a2f2e98ef91d75c1a179fe6dd1ec1b66cd24.

- Hendry M, Pasterfield D, Lewis R, Carter B, Hodgson D, Wilkinson C. 2013. Why do we want the right to die? A systematic review of the international literature on the views of patients, carers and the public on assisted dying. Palliative Medicine. 27(1):13–26. doi: 10.1177/0269216312463623

- Hockey JL, James A. 1993. Growing up and growing old: ageing and dependency in the life course. London: Sage in association with Theory, Culture & Society, School of Health, Social and Policy Studies, University of Teesside.

- Horizon Research. 2012. New Zealanders’ views on end of life choices. Auckland: Voluntary Euthanasia Society of New Zealand.

- Horizon Research. 2017. New Zealanders’ views on end of life choices. Auckland: Horizon Research.

- Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, Kim SH, Kwon JH, Hutchins R, Liem C, Bruera E. 2014. Concepts and definitions for “actively dying,” “end of life,” “terminally ill,” “terminal care,” and “transition of care”: a systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 47(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.021

- Ipsos MORI. Public attitudes to assisted dying. 2015. [accessed 2017 16 October]. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/migrations/en-uk/files/Assets/Docs/Polls/economist-assisted-dying-topline-jun-2015.pdf.

- Justice Committee. 2018. Justice committee to hear views on end of life choice bill. Wellington: Scoop Media.

- Key Research. 2013. Herald on Sunday: Lines in the sand.

- Lee CH, Duck IM, Sibley CG. 2017. Demographic and psychological correlates of New Zealanders support for euthanasia. New Zealand Medical Journal. 130(1448):9–17.

- Malpas PJ, Anderson A, Jacobs P, Jacobs T, Luinstra D, Paul D, Rauwhero J, Wade J, Wharemate D. 2017. ‘It’s not all just about the dying’. Kaumātua māori attitudes towards physician aid-in dying: a narrative enquiry. Palliative Medicine. 31(6):544–552. doi: 10.1177/0269216316669921

- Malpas PJ, Mitchell K. 2017. “Doctors shouldn’t underestimate the power that they have”: NZ doctors on the care of the dying patient. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 34(4):301–307. doi: 10.1177/1049909115619906

- Malpas PJ, Mitchell K, Johnson MH. 2012. I wouldn’t want to become a nuisance under any circumstances–a qualitative study of the reasons some healthy older individuals support medical practices that hasten death. New Zealand Medical Journal. 125(1358):9.

- Malpas PJ, Mitchell K, Koschwanez H. 2015. End-of-life medical decision making in general practice in New Zealand-13 years on. New Zealand Medical Journal. 128(1418):27.

- Malpas PJ, Wilson MK, Rae N, Johnson M. 2014. Why do older people oppose physician-assisted dying? A qualitative study. Palliative Medicine. 28(4):353–359. doi: 10.1177/0269216313511284

- Marcoux I, Mishara BL, Durand C. 2007. Confusion between euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions: influences on public opinion poll results. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 98(3):235–239.

- McPherson CJ, Wilson KG, Murray MA. 2007. Feeling like a burden to others: a systematic review focusing on the end of life. Palliative Medicine. 21(2):115–128. doi: 10.1177/0269216307076345

- Merry AF, Moharib M, Devcich DA, Webster ML, Ives J, Draper H. 2013. Doctors’ willingness to give honest answers about end-of-life practices: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 3(5):e002598. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002598

- Ministry of Health. 2017. Review of adult palliative care services in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Mitchell K, Owens RG. 2004. Judgments of laypersons and general practitioners on justifiability and legality of providing assistance to die to a terminally ill patient: a view from New Zealand. Patient Education and Counseling. 54(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00167-8

- Office of the Governor. Governor signs our care, our choice act, allowing end of life choices for terminally ill. 2018. Hawai’i: Office of the Governor; [accessed 2018 13 April]. http://governor.hawaii.gov/newsroom/latest-news/office-of-the-governor-news-release-governor-signs-our-care-our-choice-act-allowing-end-of-life-choices-for-terminally-ill/.

- Oliver P, Wilson M, Malpas PJ. 2017. New Zealand doctors’ and nurses’ views on legalising assisted dying in New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal. 130(1456):10–26.

- Parkinson L, Rainbird K, Kerridge I, Carter G, Cavenagh J, McPhee J, Ravenscroft P. 2005. Cancer patients’ attitudes toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: the influence of question wording and patients’ own definitions on responses. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 2(2):82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF02448847

- Rae N, Johnson MH, Malpas PJ. 2015. New Zealanders’ attitudes toward physician-assisted dying. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 18(3):259–265. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0299

- Reid Research. Poll: Kiwis want euthanasia legalised. 2015. http://www.newshub.co.nz/home/health/2015/08/poll-kiwis-want-euthanasia-legalised.html.

- Research New Zealand. Should euthanasia be legalised in new zealand? 2015. Wellington: Research New Zealand. http://www.researchnz.com/pdf/Media%20Releases/Research%20New%20Zealand%20Media%20Release%20-%2024-07-15%20Euthanasia.pdf.

- Rodríguez-Prat A, Balaguer A, Booth A, Monforte-Royo C. 2017. Understanding patients’ experiences of the wish to hasten death: an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 7(9):e016659. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016659

- Ryan A. 2014. Making sense of euthanasia: a Foucauldian discourse analysis of death and dying [Doctor of Philosophy]. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- Shakespeare T. 2013. Disability rights and wrongs revisited. 2nd ed. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Sheahan L. 2016. Exploring the interface between ‘physician-assisted death’ and palliative care: cross-sectional data from australasian palliative care specialists. Internal Medicine Journal. 46(4):443–451. doi: 10.1111/imj.13009

- Sibley CG. 2012. The mini-ipip6: item response theory analysis of a short measure of the big-six factors of personality in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 41(3):20–30.

- Sibley CG. 2014. Sampling procedure and sample details for the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study. NZAVS Technical Documents, e01. http://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/uoa/NZAVS.

- Sikora J. 2009. Religion and attitudes concerning euthanasia: Australia in the 1990s. Journal of Sociology. 45(1):31–54. doi: 10.1177/1440783308099985

- Sikora J, Lewins F. 2007. Attitudes concerning euthanasia: Australia at the turn of the 21st century. Health Sociology Review. 16(1):68–78. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2007.16.1.68

- Taylor C. 2015 8th July. GPs admit to helping patients die, amid calls for law change. NZ Doctor.

- Teisseyre N, Mullet E, Sorum PC. 2005. Under what conditions is euthanasia acceptable to lay people and health professionals? Social Science & Medicine. 60(2):357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.016

- Vickers M. 2016. Lecretia’s choice: a story of love, death and the law. Melbourne (VIC): The Text Publishing Company.

- Victorian Parliamentary Library & Information Service. 2017. Volunatry assisted dying bill 2018. In: Services DoP, editor. Victoria, Australia: Parliament of Victoria.