ABSTRACT

This Kaupapa Māori narrative review identifies themes in literature concerning sport, ethnicity and inclusion, from an indigenous ‘culturally progressive’ perspective. Scholars suggest that sport influences national identity and in Aotearoa/New Zealand, rugby is a rich site for examining such connections. Inclusiveness within sport is an expressed desire, although the academic scrutiny on this is limited. This study identifies and examines themes within literature (2008–2017), using a ‘Ngā Poutama Whetū’ culturally progressive review process, contributing nuanced understandings from the content. Results suggest that racist othering, representations and practices of ethnic minority exclusion are a reality in sport, although, locally, at least, the ‘cultural climate’ in sport strives for greater ethnic inclusivity. Conclusions suggest that current research in this domain is largely theoretical, insofar as challenges to organisations, power and privilege. However, future research should explore participants’ lived experiences at the intersections of ethnicity and inclusion in sport.

Introduction

Review methods are useful for interpreting findings across multiple, individual, qualitative and/or quantitative studies to combine knowledge and synthesise the conclusions drawn from them (Atkins et al. Citation2008). Review article variations are also becoming increasingly popular in research (Smith and Sparkes Citation2013). Quantitative researchers typically employ systematic review approaches including meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, meta-summaries and rapid reviews, with the latter involving an accelerated or streamlined version of the previous three (Onwuegbuzie and Frels Citation2016). These review types tend to be exhaustive, linear, detached, deductive, objective and population aggregative. They can be useful, except perhaps when aspiring to do research that enhances outcomes and experiences for ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples positioned within the margins of society who tend to be ignored or silent in the published literature (Smith Citation2006; Coakley Citation2015; Onwuegbuzie and Frels Citation2016).

To date, scholarship that synthesises ethnic or cultural diversity and inclusive practices within sport is scant (Coakley Citation2015; Cunningham Citation2015); however, it is an area that is receiving increased attention from sport practitioners (Dagkas Citation2016). There have been continued calls for more scholarly interrogation of the connections between sport and ethnicity globally (Donnelly Citation1996; Adair and Rowe Citation2010; Coakley Citation2015; Cunningham Citation2015; Dagkas Citation2016) and locally within Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) society (Palmer Citation2006; Dickson Citation2007; Watson Citation2007). Such interest was evident in four international Sport, Race and Ethnicity (SRE) conferences (2006, 2008, 2010 and 2012), and two Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) conferences (2008, 2011) in NZ where the intersections of sport, ethnicity and marginalised minorities were interrogated.

An analysis of the learnings from the 2008 and 2011 EDI conferences, suggested that in smaller research communities, such as Aotearoa NZ, academics and practitioners ought to work closer together (Myers et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, indigenous Māori scholars and activists at the 2011 EDI conference pushed for other ethnic groups and immigrant communities to speak out more against contexts that reinforce hegemonic privilege (Myers et al. Citation2013).

In order to privilege an indigenous perspective, this review uses an adapted ‘culturally progressive’ review process (Onwuegbuzie and Frels Citation2016) to incorporate a narrative approach from a Kaupapa Māori (KM) worldview. Reviewing literature from this perspective seeks to counter the privileged mono-cultural voice within academic literature (Donnelly Citation1996; King Citation2005; Coakley Citation2015). The timeframe covered (2008–2017) for the publications reviewed was to dovetail with the seminal local studies of Dickson (Citation2007), Palmer (Citation2006), Spoonley and Taiapa (Citation2009) and Watson (Citation2007), and the international SRE and EDI conferences (2006–2011) mentioned previously.

In their review of the EDI conferences, Myers et al. (Citation2013) suggested that research needs to move beyond measuring disadvantage (i.e. deficit theory), and indicated that there were promising signs that some research explored alternatives. Although, Spaaij et al. (Citation2014) argued that global sport communities continue to be unwelcoming, elitist and exclusionary to particular minority groups who do not reflect ‘the dominant white, male, high socio-economic status, high ability hegemonic discourses that continue to be pervasive within sport’ (pp. 140–141). This global viewpoint is also supported by local scholars who stated that dominant, ethnic majority members often find it difficult to:

see themselves as having a culture or belonging to an ethnic group … this opposition may take the form of an assertion of nationalism, for example … ‘we are all New Zealanders’ … [which] has the effect of declaring that expressions of minority ethnicity are at best, insignificant, and at worst, ‘unpatriotic’. It serves to reassure members of the dominant group … that theirs [ethnicity] … is the legitimate one. (Cormack and Robson Citation2010, p. 5)

Contribute an alternative analytical, interpretative lens that offers indigenous understandings of knowledge contained in extant literature (2008–2017) regarding ethnicity and inclusion within sport scholarship.

Apply Kaupapa Māori (KM) analytical themes to relevant international and local studies of sport, ethnicity and inclusion; with a focus, if possible, on rugby and Māori.

Synthesise the arguments and extrapolate conclusions from the selected studies, for the benefit of players, coaches, administrators and scholars regarding sport, ethnicity and cultural inclusion, especially in relation to rugby and Māori.

Sport and identity in NZ

Dickson’s (Citation2007) research on national identity and sport, commissioned for Sport NZ, summarised key findings from more than 70 national and international publications, including peer-reviewed journal articles, books, chapters and unpublished theses. He concluded that sport is well placed for developing the dominant majority group’s preferred national identity, while non-majority preferences are often ignored (see Bruce Citation2013). This resonates with the findings of other local (Cormack and Robson Citation2010) and international scholars in terms of ethnic minorities, national identity and dominant ‘ruling elite’ groups (Donnelly Citation1996; King Citation2005; Spaaij et al. Citation2014; Coakley Citation2015). Watson’s (Citation2007) historical review of research explored issues of ethnicity within NZ sport and revealed that, to that point, there had been ‘no systematic scholarly assessment of the connections between sport and ethnicity’ (p. 1). Similarly, in reviewing NZ’s Regional Sport Organisations and other sport providers’ responsiveness to cultural diversity, Spoonley and Taiapa’s (Citation2009) study discovered that ‘there was relatively little’ (p. 17) literature on this issue.

Moreover, the importance of sport to Māori identity and society has been explored by several indigenous scholars (e.g. Te Rito Citation2006, Citation2007; Hippolite and Bruce Citation2010; Palmer and Masters Citation2010; Erueti Citation2015) and government agencies focused on Māori wellbeing and development (e.g. Te Puni Kōkiri Citation2006b). In particular, the role rugby, as the nation’s ideologically dominant sport, plays on Māori wellbeing and identity has been closely analysed (Hokowhitu Citation2004, Citation2005, Citation2007; Te Puni Kōkiri Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2012).

The Ministry of Māori Development, Te Puni Kōkiri (TPK), highlighted that Māori ‘have been avid players of rugby since its introduction in 1870’ (TPK Citation2006a, Fact sheet 23). In 2004, over 26,000 players (20%) of all registered rugby players in NZ identified as Māori. Furthermore, 54 (34%) of the 160 NZ-based professional rugby players were Māori, representing the highest conversion rate from amateur to the professional ranks of all ethnic groups in NZ (TPK Citation2006a). In 2017 more than 41,000 (26.67%) registered players identified as Māori, and 27% of high performance players identified as Māori (NZ Māori Rugby Board Annual Report, Citation2017). Māori, therefore, are heavily invested in rugby and over-represented at the elite-level of the game compared to their 15% representation of NZ’s overall population (Statistics NZ Citation2017).

In light of the increasingly diverse cultural demographics of NZ society, reflected in rugby, there remains limited published literature examining the lived realities of Māori in rugby from an indigenous perspective. Historical research examining the ethnic make-up of the ‘All Blacks’ (the national NZ men’s rugby team) over the period 1890–1990 revealed that for around 100 years Pākehā (predominantly Europeans of Anglo-Saxon descent who settled in NZ) averaged a 90% majority position in the team (Hapeta et al. Citation2015). Thus, a Pākehā worldview dominated team culture, creating an environment that was ‘culturally blind’ to ethnic diversity (Hapeta Citation2017). A significant shift in the ethnicity of All Blacks (AB) players started to occur in the 1990s decade where Māori and Pasifika player numbers doubled from 10% to 20% on average (Hapeta et al. Citation2015). In the 2000s Māori and Pasifika players collectively represented 40%, and now they comprise almost 60% of AB players. The changing ethnic makeup of this team has influenced the overall culture of the AB team, which included the pre-match ritual of the haka ‘Ka Mate’ (composed by Ngāti Toa chief, Te Rauparaha).

In 2006, for instance, the team worked on educating the culturally diverse players about the meaning and importance of the haka (Hodge et al. Citation2014) and shortly after his appointment as the Head Coach of the All Blacks, Graham Henry expressed:

[NZ] Society has changed tremendously … and a coach needs to change with the people … to reflect society … the Polynesian influence … has become very significant. The whānau [family] is very important … the team becomes more like an extended family … you need to bring the element of inclusiveness into your coaching to be more effective. (in Romanos Citation2007, p. 87)

In the terms of reference for this review a perspective on inclusiveness included creating a safe environment where people are treated with dignity, are valued and respected and not abused, harassed, humiliated or discriminated against. Additional to the findings regarding diversity and inclusion in NZ rugby broadly, the report found that, in terms of Māori experiences within NZ rugby, ‘there are still issues of racism that need to be acknowledged and explored’ (Cockburn and Atkinson Citation2017, p. 40). To address racism and create an ethnically inclusive rugby environment, the report suggested interventions that included celebrating cultural identity. Specifically, adopting bi-cultural practices that would allow Māori to thrive – where their Māori identity ‘is acknowledged and reflected and they do not have to ‘switch modes’ to a mono-cultural environment or suppress the very things they value most’ (Cockburn and Atkinson Citation2017, p. 41). However, the findings suggested there was still some way to go and work to do to achieve genuine inclusivity in NZ rugby in regards to ethnic diversity. Similar sentiments can be expressed in terms of the lack of Māori voices within the academic literature.

A culturally progressive review method

Paradigms and perspectives, therefore, are fundamentally important for researchers to consider when conducting research, as they guide decisions and actions and provide the appropriate analytical and interpretative frameworks (Denzin et al. Citation2008). Onwuegbuzie and Frels (Citation2016) posit that a ‘culturally progressive’ narrative review requires that researchers work towards cultural awareness of their beliefs; as well as acquiring cultural competency along the way and/or generating cultural knowledge in order to communicate the role that culture plays in the review process. Moreover, they argue that a culturally progressive literature reviewer:

responds respectfully and effectively to research and other knowledge sources stemming from people (i.e. participants) and generated by people (i.e. researchers, authors) who represent all cultures, races, ethnic backgrounds … and other diversity attributes in a way that recognises, acknowledges, affirms and values the worth of all participants and researchers/authors and protects and preserves their dignity. (p. 36)

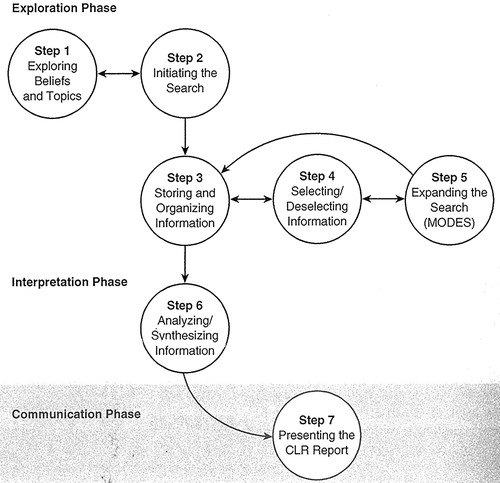

Figure 1. Onwuegbuzie and Frels’ (Citation2016) ‘seven steps’ to a comprehensive literature review.

A Kaupapa Māori review method: Ngā Poutama Whetū

‘Kaupapa Māori’ is a term that has become synonymous with an indigenous movement in NZ that was practitioner-based before it became a research perspective applied both locally and internationally (Smith Citation1997, Citation1999; Rodriguez et al. Citation2017). It aligned philosophically and pragmatically with Māori worldviews and values that mainly considered the advancement and development of Māori people and Māori knowledge (Pihama et al. Citation2002). Kaupapa Māori concepts and practices when applied to research involves an epistemological, ontological, axiological and methodological stance that aligns with research perspectives that examine cultural production, power relations and ideological struggles (Donnelly Citation1996; King and Springwood Citation2001; King et al. Citation2002; Pihama et al. Citation2002; King Citation2005) in institutions and organisations such as sport (Coakley, Citation2015).

According to Smith (Citation2006), knowledge is ‘one of the key commodities of the twenty-first century’ (p. 20). As gatekeepers of knowledge, editors of journals, article reviewers, as well as public and private funding providers have the privilege to determine whose and what knowledge counts in the ‘knowledge economy’ (Smith Citation2006). As a result, existing academic ‘regimes of control’ (Smith et al. Citation2016, p. 132) tend not to recognise, understand or indeed value indigenous knowledge. This raises the question ‘how do we include ethnic minority voices and indigenous knowledge in sport scholarship’?

Functional Kaupapa Māori sport researchers (e.g. Te Rito Citation2006, Citation2007; Hapeta and Palmer Citation2009, Citation2014; Palmer and Masters Citation2010; Hodge et al. Citation2011; Erueti and Palmer Citation2014) analyse the meanings and experiences of Māori in sport, and on sports in general as potential sites for cultural wellbeing and transformation. Critical Kaupapa Māori sport researchers (e.g. Hokowhitu Citation2004, Citation2005; Hippolite Citation2008) also advocate for action and social change within sports institutions, structures and contexts that aim to challenge and transform exploitive and oppressive practices (Pihama et al. Citation2002; Coakley Citation2015).

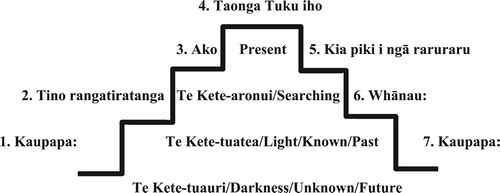

Respected Māori scholar, Sir Mason Durie (Citation2004, Citation2010) articulated that the tools of one worldview ought not to be used to analyse and understand another. Thus, an adapted version of Onwuegbuzie and Frels (Citation2016) ‘seven steps’ review model that reflects an indigenous worldview is presented for this review (see ). This model titled ‘Ngā Poutama Whetū’ (NPM) incorporates Kaupapa Māori principles (see Pihama et al. Citation2002) as a tool that rejects the colonial canons (Adair and Rowe Citation2010; Smith et al. Citation2016) and is used here for identifying, selecting, reviewing and synthesising literature on sport, ethnicity and inclusion.

As Durie (Citation2004) suggested, critical indigenous scholars reject ‘the tools of the colonizer … [and place] greater emphasis on the construction of models where multiple strands … make up an interacting whole’ (p. 1140). Literally, Ngā Poutama Whetū (NPW) translates into ‘the stairway to the stars’ and from a KM perspective, there is a more meaningful narrative of enlightenment implied about Tāne, known primarily as the Māori God of the forests and birds, and his ascent to the heavens to retrieve the baskets of knowledge (Kāretu Citation2008). Tāne has other claims to significance, especially in relation to the separation of his parents Ranginui, the Sky Father, and Papa-tū-ā-nuku, the Earth Mother, whereby he is/was credited with allowing light into the world (Kāretu Citation2008).

An indigenous perspective of knowledge attainment, symbolised by these three ‘kete’ (baskets), thus, underpins this multi-faceted model. Scholar Reverend Māori Marsden (Citation2003), suggested that the basket of darkness, ‘Te kete-tuauri’, represents the unknown or things not yet known (indicative of future knowledge). ‘Te kete-tuatea’ (basket of light) represents what is known or extant knowledge that we have already been enlightened with (handed down from past generations). Finally, ‘Te kete-aronui’ is the pursuit of knowledge that we currently seek (the life-long search). These past, present and future realms of knowledge, which are potentially ‘messy’ and non-linear (Jackson Citation2015), supports Webster and Watson’s (Citation2002) notion that analysing the past is an essential feature when reviewing literature to prepare for the future.

NPW begins with the kaupapa, which is about the collective aims and aspirations of Māori (Pihama et al. Citation2002). In particular KM research, which in this case is focused on literature in the area of sport, ethnicity and inclusion, explores the lived realities of ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples. Kaupapa, therefore, is most pertinent to consider in a ‘culturally progressive’ narrative review at the start (NPW step 1) and then revisited again (NPW step 7) at the end of the review process. At step 1, (i.e. CLR’s exploring beliefs and topics) we considered what key words and topics to include in our search to locate and identify literature. These included ‘sport’, ‘ethnicity’ and ‘inclusion’ spanning the decade 2008–2017 to identify studies related to the kaupapa (NPW step 1) that have been published in international peer-reviewed journals. For the local literature the key words ‘Maori’ and ‘sport’ were used to identify publications in the same data bases that were to be searched.

Next, the NPW step 2, the principle of tino rangatiratanga (self-determination) was applied when reviewing the abstracts of the literature that emerged. This principle also reinforces the autonomy for KM researchers to determine which articles should be considered as relevant to the review’s kaupapa. In alignment with CLR’s step 2 (initiating the search) this involved identifying publications in two search databases that are commonly used in review research within sport (Schulenkorf et al. Citation2016). At the time the search was conducted SportDiscus returned 27 and Scopus 26 international publications. For local studies, SportDiscus (44) and Scopus (38) also returned multiple ‘hits’.

At step 3 of the NPW model, the KM principle of ako (culturally preferred pedagogies and reciprocity), was considered. The CLR process identifies this step as storing and/or organising information. In an applied review context, we considered if the research design and methodologies were organised in line with the ako principle often underpinning KM research, which is sometimes referred to as research ‘by, with, and for’ Māori (Smith Citation1997, Citation1999; Bishop Citation1998). Although meeting all three of these criteria would be ideal, the decision was made to include articles (to step 4), if they met at least two of the three criteria for KM research.

During NPW’s step 4 the KM principle of taonga tuku iho (treasures to pass on) was applied, consistent with CLR’s step 4 (de/selecting information), to decide whether to include or exclude studies. An adapted NPW position involved appraising and evaluating each study’s overall applicability, to see if the aims aligned with the kaupapa of this paper, and if so it progressed. If the article was not aligned with the kaupapa, it was excluded. The consideration of contributions as ‘taonga’ (valued treasure) meant that if theoretical assumptions or findings were deficit-based they were not considered. If articles were strengths-based or had perceived value for Māori or other Indigenous/ethnic minorities’ aspirations, then they were included. Because this review wanted to reveal extant literature on sport, ethnicity and inclusion that focused on the lived realities of ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples, the exclusion criteria below were also considered to be justified:

Research that merely considered ethnicity as one of many variables (i.e. sports-related injuries, epidemiological, or psychological studies).

Quantitative data collection methods (e.g. close-ended surveys) that did not give voice to ethnic minorities and/or indigenous peoples’ lived realities.

Articles where ethnicity was only a secondary or minor focus with regards to diversity and inclusion in sport (e.g. articles that primarily focused on diversity and inclusion in sport with regards to gender, sexuality, disability, and religion and where ethnicity was only mentioned in passing).

Articles that were ‘for’ indigenous peoples or ethnic minorities, but it was unclear whether they were ‘by’ such researchers or conducted ‘with’ them (as research participants).

During NPW step 5, we adapted and applied the KM principle ‘kia piki ki ngā raruraru o te kainga’ (socioeconomic mediation) to question whose and what knowledge counts as valid or legitimate in the ‘knowledge economy’ (Smith Citation2006). Onwuegbuzie and Frels’ (Citation2016) stress the value of expanding a search to include Media, Observations, other Documents, Experts and Secondary data sources (MODES). However, in order to align with scholarly expectations we could not consider such other ‘sources’ as robust if they were published outside of rigorous, peer-reviewed, journal articles.

After the ‘exploration’ phase (steps 1–5) comes the NPW analytical phase (also CLR’s step 6). Here we applied the KM principle of whānau (NPW step 6) to reveal the ‘richness’ of emergent concepts (tangata) regarding their inter-relatedness with others (Whānau/hapū) and synthesised these translations into themes (Iwi) from paper 1 with those from paper 2 and so forth, consistent with Onwuegbuzie and Frels’ (Citation2016) procedure. For included articles, we identified concepts (tangata) and considered these vis-à-vis themes (Iwi) throughout subsequent studies.

Pragmatically, the qualitative analysis, synthesis and subsequent translation processes could not and were not simply reduced to mechanistic conventions, which we acknowledge may prove difficult to replicate. However, to facilitate replicability, during the NPW step 6, we used preliminary indigenous concepts that help to explain relationships that includes singular units (tangata – people) to compile broader codes (whānau – family), then developed categories (hapū – larger collectives in Māori communities/society) in order to identify themes (iwi – the bones or tribes that Māori often affiliate with). To determine if studies related, in terms of supporting or refuting previous themes, we compared and contrasted if/how these whānau and hapū inter-related (translated) to iwi (themes) in other local or international studies.

Admittedly, scholars have previously used this style of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Braun et al. Citation2016) to code, categorise and organise themes within and among studies (Atkins et al. Citation2008). However, none (to our current knowledge) have done so from an indigenous/Māori perspective in the way that we have here using the proposed ‘NPW’ model.

Finally, step 7 of the NPW model reconsiders the Kaupapa (reconnecting with step 1); the CLR defines this as the communication phase, which seeks to express the results and findings making them accessible for readers. This re-interpretation and re-presentation of the extant literature directly links to the kaupapa of this review. We sought to contribute an alternative, culturally progressive, analytical lens (NPW) that offers understandings from international and local literature on sport, ethnicity and inclusion. Applying KM prinicples to relevant literature and where possible in rugby by/with/for Māori; synthesise the arguments and conclusions from these studies for the benefit of inclusion for sport players, coaches, administrators, scholars and others with an interest in the topic.

For the international literature, at the time of conducting this review research, the key words ‘sport’, ‘ethnicity’ and ‘inclusion’ were searched in the SportDiscus (27) and Scopus (26) search databases. The same respective databases were used for the local studies, the exception being that the key words ‘Māori’ and ‘Sport’ were used to identify local studies published in SportDiscus (44) and Scopus (38). Eventually, eight articles from the international and local publications were eventually included in this study after progressing through the NPW review process. At an applied level, this was because the articles were more applicable and directly focussed on the kaupapa of this KM, culturally progressive review and met the criteria at each checkpoint of the NPW steps.

Results

This section presents the results of this KM narrative review. The international () and local () results consider the three ‘kete’ of knowledge: past, present and future, insofar as the literature identified from the past decade (2008–2017) are synthesised and discussed herein. As Onwuegbuzie and Frels (Citation2016) suggested, on occasion the translated results are likely to be presented in a delineated (by time) and potentially ‘messy’ (Jackson Citation2015) fashion, which in this case reflects the fluidity and non-linearity and intertwined fusion of Māori temporal perspectives (Jackson Citation2015; Palmer Citation2016).

Table 1. International literature.

Table 2. New Zealand literature.

Results: an integrated discussion

The international literature selected through the Ngā Poutama Whetū process indicated that research of this kaupapa tended to be conducted in and across four cultural or colonial contexts, including Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), North America (Canada/United States) and Taiwan. While the literature spanned various sports, colonial sports such as Football/Soccer dominated the studies (4/8) as did Rugby (Union) in the local research (5/8). Regardless of the cultural context or sporting code, two major themes emerged (i) ‘Racism, otherness and assimilation’, and (ii) ‘Representations and expressions of identity’ which are discussed below. Later, in the concluding section, future research directions that address the gaps and limitations identified herein are recommended.

Theme #1: Racism: otherness and assimilation

The findings within the 10 studies (international = 4, and local = 6) that highlighted this theme, indicated that while ethnic racism still exists in sport in some colonised countries (e.g. expressed through ‘othering’), some ethnic minorities felt they were successfully assimilated into (White) society in part due to being athletes who gained status and high recognition through sport.

Sawrikar and Muir’s (Citation2010) research involved focus groups that examined the experiences of ethnic minority women in Australian sport. Of their 94 participants, 38 were from four countries: Iraq (n = 11; 12%), Japan (n = 10; 11%), Somalia (n = 9; 10%) and India (n = 8; 9%), while the remaining 56 women came from 30 other countries outside Australia. The results of this study revealed that Australian sport’s dominant ‘us’ verses minority ‘other’ psyche was a major theme. Their participants reported experiencing both covert ‘institutional racism’ and overt racism within Australian sports settings. Also due to public hostility some participants experienced (e.g. being called ‘terrorists’), they felt their safety was compromised.

In the United Kingdom (UK), Bradbury’s (Citation2011) research demonstrated similar trends. His qualitative, semi-structured, interviews with Black Minority Ethnic (BME) amateur Football (Soccer) ‘workers’ at 10 case study clubs aimed to identify issues they faced around access and sustainability of participation levels as players, coaches and managers. The ‘locally grounded narratives’ of respondents suggested that racism existed at multiple levels of Soccer, not only in Leicestershire county, but UK-wide. Further, unchallenged BME stereotypical assumptions and overtly racist remarks continued to circulate within ‘the largely under-researched area of ‘race’, culture and identity in amateur football’ (p. 24).

Other Soccer-based studies supported both Sawrikar and Muir (Citation2010) and Bradbury’s (Citation2011) studies. Indeed, Spaaij’s (Citation2012, Citation2015) three year, ethnographic field-based study, which included 51 Somali refugees involved in Australian clubs, found that the inclusive/exclusive ethnic boundary was often a difficult border for those participants to cross due to the entrenchment of the ‘us’ verses ‘other’ racist attitudes, deeply ingrained into sport’s psyche.

Additionally, Canadian-based scholars Abdel-Shehid and Kalman-Lamb (Citation2015) provided a deconstructive analysis of the UK-based film ‘Bend it like Beckham’, which is about the daughter of a strict Indian couple in London, who is not permitted to play organised soccer. Exploring the seductive ‘myth’ of sport (Soccer) as an instrument for social inclusion those scholars argued that the film actually did little to challenge the inequalities and racist stereotypes of Indian persons in the hegemonic structure of English (and Canadian) society.

In the United States (US), however, Gems’ (Citation2012) historical analysis revealed that the sporting successes for early Italian migrants (from whom he himself descends) countered originally racist, derogatory and stereotypical ‘perceptions of Italians as gangsters and greatly aided their gradual inclusion, acceptance and identity as [White] Americans … Sport and popular culture [music, movies] afforded a means other than crime to achieve recognition’ (p. 486). Thanks to the achievements of Joe DiMaggio and others in sport, especially boxing, early Italian immigrants, while initially subjected to racism, were eventually accepted into ‘mainstream’ (white) American society.

Through our analysis, the majority of these international findings, identified within the theme above, were able to be translated and related to some of the experiences of indigenous Māori in Aotearoa NZ. For example, due largely to the spread of Christianity and colonisation, Māori were eventually assimilated, but in many cases are still marginalised in NZ society, and as we saw in Gems’ study (Citation2012), sport became a way for them to gain some degree of ‘entry’ into ‘white’ mainstream NZ society. Hokowhitu’s (Citation2009) critical and de-colonial examination of NZ rugby, for example, traced the genesis of dominant racialized discourses back to the 1888–1889 ‘Natives’ team’s rugby tour to Great Britain. He argued that, while some historical moments of ‘creative flair’ within the Māori game subversively disrupted and fractured dominant discourses of Māori rugby players in NZ, this legacy of resistance to colonial dominance needed to be escalated.

This notion of resisting racist and disrupting majoritarian (i.e. coloniser) perspectives and dominance also featured in Palmer and Masters’ (Citation2010) investigation of Maori women’s experiences in sport leadership roles. Their study explored the barriers that such women faced and the strategies used to negotiate their presence in the male-dominated and often racist structure of sport. These authors, for instance, argued that organised sport is ‘one of the most privileged, Eurocentric and masculine institutions in NZ’ (p. 332). The participants in their research reported using hybrid leadership styles that integrated Māori values along with their ethno-cultural and gendered identities, which also placed additional strain on their wellbeing. These scholars also reinforced the necessity for future studies to examine intersectionality in sport with regards to indigeneity and gender.

Calabrò (Citation2014) did exactly that in her year-long, field-based, ethnographic study of Māori rugby in NZ that included first-hand interviews with 18 Māori participants. Her research, which included some key figures in both NZ and Māori rugby, confirmed that the marginalisation of Māori rugby was often ‘silenced’ and concealed by seemingly egalitarian policies. As a result Calabrò (Citation2014) recommended that Māori should use rugby to politically reassert their identity in NZ’s colonised landscape.

Furthermore, Hippolite and Bruce’s (Citation2010) critical KM research involving 10 Māori pukengā (experts) who collectively had 360 years’ experience in NZ sport settings, assessed the lived realities of these participants in regard to NZ sport’s ‘cultural competency’. True to rejecting the colonial canon, they adapted the ‘cultural competency continuum’ (Cross et al. Citation1989), which extends from cultural destructiveness at one extremity to cultural proficiency at the other. Between these polar-opposites are four other points: cultural incapacity; cultural blindness; cultural pre-competence; and cultural competence. Their pukengā expressed beliefs that NZ sport reflected ‘colonial ways of thinking that frequently ignore or devalue Māori values or interpret assertions of self-determination as separatist and devisive’ (Hippolite and Bruce Citation2010, p. 85–86). Indeed, the participants’ informed views suggested that NZ sport was positioned between cultural incapacity and cultural blindness. In concluding, however, they suggested that the collective aspiration of these pukengā for NZ sport lay between cultural competency and towards sport becoming a culturally proficient institution.

Theme #2: Representations and expressions of identity

This theme is about the representations (or lack of) and/or expressions of ethnic rituals, symbols and identity in sport as indicated in the literature. It examines the balance and in/visibility of how ethnic diversity is represented or celebrated in sport. Returning to Sawrikar and Muir’s (Citation2010) Australian study that interrogated the mainstream media’s portrayal of sport in that country, they found that ‘one of the most significant barriers to participation in sport … is a feeling that sport is an exclusively white institution … [which] generates social exclusion’ (p. 366). Indeed, their ethnic minority participants believed that representations of sport participation within the mainstream media were largely exclusive to white Australians.

Related, albeit indirectly, to the subliminal saturation (i.e. over-representation) of whiteness in Australian sport was Bradbury’s (Citation2011) UK-based study. In it he argued that despite the high-levels of representation of BME participants in Soccer at the ‘grassroots’ level, issues of ‘race’ have traditionally been under-researched and marginalised as being ‘unworthy’ of (white) academic scrutiny. The normalisation of whiteness in football/soccer alongside the invisibility of BME players in the research space they saw as ‘WEIRD’ (Henrich et al. 2010).

In the US, an ‘Italian quest for whiteness’ involving representations of ‘similarity’ expressed as ‘we’re just the same as you’ were uncovered by Gems (Citation2012); a finding synonymous with Hwang’s (Citation2015) observations from Taiwan where he highlighted the notion of ‘mimicry’ of western ways in Baseball. Hwang argued that cultural rituals in the local game mimicked those in US Baseball traditions. It appeared that Taiwanese Baseball players and spectators were culturally blind to western, colonial ways of hegemonic assimilation through sport.

An explicit example of dominant culture representations was offered in Abdel-Shehid and Kalman-Lamb’s (Citation2015) study of the UK-based film ‘Bend it like Beckham’ that reinforced a ‘culture clash’ understanding of society. This ‘clash’ is where non-hegemonic groups are blamed for: ‘their refusal to fully integrate to the principles and norms of the liberal state, thereby reasserting the centrality of whiteness’ (p. 143). Instead of promoting multiculturalism and challenging cultural and gendered stereotypes, they argued that the film clearly demonstrates that ethnic fusion is not ideal suggesting that ‘it must be England verses Asia and England must prevail’ (p. 148).

Another UK study by Rankin-Wright et al. (Citation2016) that involved interviews with ‘key’ (all white) stakeholders (N = 15) from nine UK sport National Governing Bodies (NGBs) reinforced a similar theme. Drawing on Black feminist and critical race theory (CRT), Rankin-Wright, et al. identified ‘whiteness’ as one of three key themes. These scholars argued that colour-blind ignorance to whiteness was a key feature within the sport coaching UK (scUK) sector, a workforce weakened by its white similitude. The authors also found that ethnic diversity within the scUK workforce did not automatically equal inclusion and that agency to advocate for BME groups was left up to individual champions, rather than policies to ensure that practices and people were inclusive of diversity.

In terms of the international studies, then, the representations, reflections and consequent normalisation of whiteness featured across various continents from the Australian, Asian, North American and UK contexts. In Aotearoa NZ, Hokowhitu and Scherer’s critical investigation (Citation2008) of historical Māori rugby representations in mainstream NZ media also demonstrated the centrality of whiteness. These scholars argued that the mediated and dominant discourse of egalitarianism served only to veil the reality of historical Māori and Pākehā segregation within NZ rugby. However, they suggested that more recently, the ‘hyperrace’ post-modern condition is de-centering the dominance of whiteness whereby new ‘hybrid’ identities are challenging white privilege such as with the inclusion of blonde-haired, blue-eyed, white-appearance players (e.g. Daniel Braid, Tony Brown and Christian Cullen) selected to ‘represent’ the Māori All Blacks’ rugby team due to their distant whakapapa (genealogy) links.

Hokowhitu’s (Citation2009) later investigation reinforced these critiques in relation to a specific Māori ritual (i.e. the haka) important within NZ rugby and how that is represented in the dominant discourse. Hokowhitu indicates that the haka ritual was first performed by the Natives rugby team (predominantly Māori players) that toured the UK in 1888–89. Furthermore, the first sanctioned NZR (Union) team captain, Tamati (Tom) Ellison, a Māori, introduced the haka ritual to the national men’s team, and has also been credited for the eventual adoption of the Black Jersey and Silver Fern emblem. According to Hokowhitu, Ellison’s subversive creativity and mana (prestige), however, have been obscured by dominant ‘popular memory’ that positions Māori ‘within the margins of a superior white nation … only able to perform [their] practices in [a] segregatory fashion … as token gestures within broader colonial society (e.g. the haka)’ (p. 2321).

Other investigations into Māori rugby concurred with these findings. Calabrò (Citation2014), for example, argued ‘that the All Blacks representations conceal more than they reveal of the connection between Māori and rugby … [who] as indigenous subjects [are] trying to cope with enduring manifestations of colonialism’ (p. 392). Specifically, she discussed the haka ritual with her ‘interlocutors’ who reiterated that, in the public platform now provided in professional rugby contexts, the haka represents a dramatisation of the team’s mana (respect) as well as acknowledgement of their opponents. Moreover, this ritual also represents a way for Māori to ‘transmit their knowledge to the younger generations, reinforce their sense of identity, and exercise their culture’ (p. 393), even if ‘the country [NZ] usually fails to recognise it’ (p. 395).

Moreover, in an attempt to make heard the untold and often silenced stories of Māori women, including within rugby, Forster et al.’s (Citation2016) paper used a mana wāhine (Māori feminist) and pūrākau (narratives/storytelling) approach to share their auto-ethnographic accounts of leadership as Māori women. In particular, as the former Black Ferns’ (the NZ Women’s national rugby team) captain over the period 1997–2006, Palmer’s pūrākau provided a mana wāhine perspective of their team haka ritual as she recounted what that represented to them. Also, similar to Māori rugby, according to Forster et al. (Citation2016), the Black Ferns players have struggled to gain recognition, resources and credibility in this hyper-masculine sport.

Closely related to these ‘representations’, in the literature there were other expressions of cultural identity as a representative form of celebrating cultural diversity. Erueti and Palmer’s (Citation2014) investigation, specifically on expressions of Māori ethno-cultural identity with elite-level athletes, examined the lived realities of ten Māori Olympians and/or Commonwealth Games team members. These environments had been making explicit efforts to include authentic bicultural dimensions within the overall team culture (Hodge and Hermansson Citation2007). Employing critical race theory (CRT) Erueti and Palmer (Citation2014) used a pūrākau methodology to investigate the public and private ways that such Māori athletes expressed their identity. Their analysis of the athletes’ narratives revealed that the inclusion of tikanga (protocols) and mātauranga Māori (knowledge) into the Games team environment ‘encouraged a public expression of ethno-cultural identity for Māori elite athletes. Subsequently, the different strands of their identities as Māori, NZers/Kiwis, athletes and as part of a team/whānau were weaved together to enrich their experience, [and] wellbeing’ (Erueti and Palmer Citation2014, p. 1071).

Participants’ insights also suggested that there were benefits for them privately, including for some reconnecting with their whenua (land-base) and whānau (family). Overall, from their perspectives, these Māori athletes advocated that it was seen as acceptable to be unique and to express identities dissimilar to the dominant group. This suggests that expressions of diverse ethno-cultural identities in some NZ sports teams and settings at least (e.g. the Olympics and Commonwealth Games), are starting to be ‘normalised’ and celebrated.

Conclusions

The aim of this KM narrative-review was to identify key themes from relevant global and local studies of sport, ethnicity and inclusion; with a focus on indigenous or ethnic minorities and, where possible, on rugby and for Māori. While the results presented here may not apply to all sports contexts and participants, the reviewed literature has identified and illuminated some commonalities, especially in terms of racism and representations of cultural diversity that differs to the academic and sport’s hegemonic ‘mono-culture’ (King Citation2005; Coakley Citation2015).

In terms of the international scholarship reviewed, it is clear that racist representations and ethno-cultural exclusionary practices are still a reality today for many indigenous and ethnic-minority players, coaches and leaders in sport. Once included in mainstream sport and society, there is also the risk of assimilation and the annihilation of cultural difference, which ethnic minority individuals in sport either accept or resist. This review highlights that in some NZ sports, aspects of Māori culture are becoming better integrated, but there is still a tendency to ignore or minimise the role that ethnic minorities can play in NZ sport. Some of this scholarship, however, comes from a non-Māori perspective, and the issues of tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), therefore, are not sufficiently addressed, which necessitates further, critical, Kaupapa Māori studies of sport.

Internationally, sport has an impactful influence over national identity and culture as well as ethnic minority culture and identity, and in NZ, rugby continues to be a rich site for examining ethnic identities and how minority cultures are ignored, assimilated or fully integrated into the culture of the organisation, the club, or the team. The impact that this has on the wellbeing of teams and individuals (players and coaches in particular), however, is largely unexplored.

Critically, though, current scholarship in this space appears to be peripheral insofar it questions the organisational structures or power relationships privileged in the sport of rugby at more latent analytical levels rather than at the practitioner and coal-face of rugby. There does appear to be a desire from NZR and other sports organisations to address issues of diversity and inclusion and provide culturally safer and more enriching sport settings. Further research is required that explores the impact of culturally inclusive settings on Māori and non-Māori participants’ wellbeing, because, as Calabrò (Citation2014) suggested ‘Māori engagement with mana in the context of rugby will continue to be played out in contradictory ways for some time to come’ (p. 402). Through applying a KM lens and proposing the indigenous ‘Ngā Poutama Whetū’ model, this present review has sought to contribute nuanced understandings of themes and findings that may bridge the gap between extant scholarship and the lived realities of ethnic minority and indigenous people in sport.

The ‘snap shot’ provided by the international and local literature reviewed here has limitations, such as studies not included through the KM-alignment screening process utilised. Furthermore, non-English journal publications, for example, were not included in this review, despite some ethnic-minority experiences potentially being published in other languages. Another limitation of this research, was that other scholarly works, such as non-peer reviewed publications and dissertations were excluded. In this latter regard Smith et al. (Citation2016) asked if axiological ‘mayhem’ is at play within the academy, and a search of NZ University library data bases revealed that there were over 50 Māori Masters’ theses or PhD dissertations in sport, yet this level of scholarship is not reflected within published, peer-reviewed, journal articles. As such, we cannot and do not claim that all perspectives are represented in this KM, culturally progressive, narrative review. This point prompts us to reconsider the question posed earlier: how do we include ethnic minority voices and indigenous knowledge in sport scholarship’? Is the silence reflective of either minority authors’ hesitancy to publish or perhaps also an issue of ‘silencing’ through manuscript acceptance rates when WEIRD ‘worldviews collide’ with others?

In summation, while starting to grow, there remains scant scholarship as expressed by scholars (e.g. Dickson Citation2007; Watson Citation2007; Spoonley and Taiapa Citation2009), with regards to research that critically analyses the intersections of ethnicity, national culture and sport. In particular, there needs to be more research that explores what the lived realities are for Māori as people heavily invested in rugby. Therefore, we reiterate Erueti and Palmer’s (Citation2014) recommendation that future research is required using KM methods, undertaken (ideally, although not exclusively) by Māori researchers with and for Māori communities; especially studies that examine the realities facing Māori in sport, and rugby in particular, so that dominant discourses can be analysed from indigenous perspectives. Indeed, as these scholars posit, further research is needed that interrogates how ‘incorporating elements of tikanga and Matauranga Māori for the purposes of national identity on the international stage … impacts on Māori and non-Māori athletes’ (p. 1072) in terms of their holistic well-being.

Finally, this study disrupts to a degree the whiteness in sport scholarship and contributes to the kōrero (discussion) privileging an indigenous lens and the often silenced voices of ethnic minority and indigenous communities; re-interpreting and re-presenting the extant scholarship from an indigenous worldview. With this in mind, we close with a reminder to the academy. As prominent Māori scholars Durie (Citation2004) and Smith (Citation2006) already alluded to, and as King (Citation2005) once suggested: sport and all scholars must be mindful of the implications of their social and epistemological positionality, as neither the ‘epistemological status of whiteness as the implicit framework for the organisation of what we know as human sciences nor the epistemological status of white scholars as the authorized agents of institutional knowledge is called into question by a field’ (p. 402) that is dominated by white academics.

Indeed, similarly in sport, in academia we cannot claim to be inclusive of diversity, if we demonstrate exclusionary practices. The proposed Ngā Poutama Whetū as an analytical tool, may help move the conversations along with regards to an alternative and ‘culturally progressive’ way to review literature within domains of this kind.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jeremy Hapeta http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8853-1572

References

- Abdel-Shehid G, Kalman-Lamb N. 2015. Multiculturalism, gender and bend it like Beckham. Social Inclusion. 3(3):142–152. doi: 10.17645/si.v3i3.135

- Adair D, Rowe D. 2010. Beyond boundaries? ‘Race’, ethnicity and identity in sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 45(3):251–257. doi: 10.1177/1012690210378798

- Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, Engel M, Fretheim A, Volmink J. 2008. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 8(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-21

- Bishop R. 1998. Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research: a Maori approach to creating knowledge. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 11(2):199–219. doi: 10.1080/095183998236674

- Bradbury S. 2011. From racial exclusions to new inclusions: black and minority ethnic participation in football clubs in the East Midlands of England. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 46(1):23–44. doi: 10.1177/1012690210371562

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. 2016. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Brett Smith, Andrew C. Sparkes, editors. Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise. London: Routledge; p. 191–205.

- Bruce T. 2013. (Not) a stadium of four million: speaking back to dominant discourses of the Rugby World Cup in New Zealand. Sport in Society. 16(7):899–911. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2013.791153

- Calabrò DG. 2014. Beyond the all blacks representations: the dialectic between the indigenization of rugby and postcolonial strategies to control Māori. The Contemporary Pacific. 26:389–408. doi: 10.1353/cp.2014.0039

- Coakley JJ. 2015. Assessing the sociology of sport: on cultural sensibilities and the great sport myth. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 50(4–5):402–406. doi: 10.1177/1012690214538864

- Cockburn R, Atkinson L. 2017. Respect and responsibility review. A commissioned report for New Zealand Rugby. http://nzrugby.co.nz/what-we-do/rugby-responsibility/respect-and-responsibility-review.

- Cormack D, Robson C. 2010. Ethnicity, national identity and ‘New Zealanders’: considerations for monitoring Māori health and ethnic inequalities. Wellington (NZ): Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare.

- Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Isaacs MR. 1989. The cultural competence continuum. Toward a culturally competent system of care: a monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Center for Child Health & Mental Health Policy, Georgetown University Child Development Center, 13.

- Cunningham GB. 2015. Diversity and inclusion in sport organisations. 3rd ed. Oxon, UK; New York (USA): Holcomb Hathaway Publishers.

- Dagkas S. 2016. Problematizing social justice in health pedagogy and youth sport: intersectionality of race, ethnicity, and class. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 87(3):221–229. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2016.1198672

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, Smith LT, editor. 2008. Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Dickson G. 2007. National identity: an annotated bibliography. Auckland (NZ): AUT University. New Zealand Tourism Research Institute.

- Donnelly P. 1996. The local and the global: globalization in the sociology of sport. Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 20(3):239–257. doi: 10.1177/019372396020003002

- Durie M. 2004. Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Epidemiology. 33(5):1138–1143. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh250

- Durie M. 2010. Outstanding universal value: how relevant is indigeneity? In: R. Selby, P. Moore, M. Mulholland, editor. Maori and the environment: Kaitiaki. Wellington (NZ): Huia Publisher; p. 239–249.

- Erueti B. 2015. Ngā kaipara Māori: ngā pūmahara o te tuakiri Māori me te ao hākinakina = Māori athletes: perceptions of Māori identity and elite sport participation: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Management, Massey Business School, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand [Doctoral dissertation]. Massey University.

- Erueti B, Palmer FR. 2014. Te Whariki Tuakiri (the identity mat): Māori elite athletes and the expression of ethno-cultural identity in global sport. Sport in Society. 17(8):1061–1075. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2013.838351

- Forster ME, Palmer F, Barnett S. 2016. Karanga mai ra: Stories of Māori women as leaders. Leadership. 12(3):324–345. doi: 10.1177/1742715015608681

- Gems GR. 2012. Sport and the Italian American quest for whiteness. Sport in History. 32(4):479–503. doi: 10.1080/17460263.2012.738610

- Hapeta J. 2017. Is New Zealand rugby culturally blind or competent? Conference paper presented at the World in Union (New Zealand) International Rugby conference. New Zealand: Sport and Rugby Institute, Massey University.

- Hapeta J, Mulholland M, Kuroda Y. 2015. Tracking the stacking: the all blacks from 1880–1980. Conference paper presented at World in Union (UK) conference; UK: University of Brighton.

- Hapeta J, Palmer F. 2009. Tū Toa–‘Māori youth standing with pride as champions’ in sport and education. Journal of Australian Indigenous Studies. 12(1–4):229–247.

- Hapeta JW, Palmer FR. 2014. Māori culture counts: a case study of the Waikato chiefs. In: T. Black, editor. Enhancing Matauranga Māori and global indigenous knowledge. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Qualifications Authority; p. 101–116.

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. 2010. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature. 466(7302):29.

- Hippolite HR, Bruce T. 2010. Speaking the unspoken: racism, sport and Māori. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies. 2(2):23–45.

- Hippolite R. 2008. Towards an equal playing field: racism and Māori women in sport. MAI Review LW. 1(1):12.

- Hodge K, Hermansson G. 2007. Psychological preparation of athletes for the Olympic context: the New Zealand summer and winter Olympic teams. Athletic Insight. 9(4):1–14.

- Hodge K, Henry G, Smith W. 2014. A case study of excellence in elite sport: motivational climate in a world champion team. The Sport Psychologist. 28(1):60–74. doi: 10.1123/tsp.2013-0037

- Hodge K, Sharp LA, Heke JI. 2011. Sport psychology consulting with indigenous athletes: the case of New Zealand Māori. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. 5(4):350–360. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.5.4.350

- Hokowhitu B. 2004. Tackling Maori masculinity: a colonial genealogy of savagery and sport. The Contemporary Pacific. 16(2):259–284. doi: 10.1353/cp.2004.0046

- Hokowhitu B. 2009. Māori rugby and subversion: creativity, domestication, oppression and decolonization. The International Journal of the History of Sport. 26(16):2314–2334. doi: 10.1080/09523360903457023

- Hokowhitu B, Scherer J. 2008. The Mäori all blacks and the decentering of the white subject: hyperrace, sport, and the cultural logic of late capitalism. Sociology of Sport Journal. 25:243–262. doi: 10.1123/ssj.25.2.243

- Hokowhitu BJ. 2005. Rugby and tino rangatiratanga: early Māori rugby and the formation of Māori masculinity. Sporting Traditions: Journal of the Australian Society for Sports History. 21(2):75–95.

- Hokowhitu BJ. 2007. Māori sport: pre-colonisation to today. In: C. Collins, S. Jackson, editor. Sport in Aotearoa/New Zealand society. 2nd ed. Melbourne (Australia): Thomson; p. 78–95.

- Hwang DJ. 2015. Assessing the sociology of sport: on ethnicity and nationalism in Taiwanese baseball. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 50(4–5):483–489. doi: 10.1177/1012690215569746

- Jackson AM. 2015. Kaupapa Māori theory and critical discourse analysis: transformation and social change. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 11(3):256–268. doi: 10.1177/117718011501100304

- Kāretu T. 2008. Te Kete Tuawhā, Te Kete Aronui-The Fourth Basket. Te Kaharoa. 1(1).

- King CR. 2005. Cautionary notes on whiteness and sport studies. Sociology of Sport Journal. 22(3):397–408. doi: 10.1123/ssj.22.3.397

- King CR, Springwood CF. 2001. Beyond the cheers: race as spectacle in college sport. New York: SUNY Press.

- King CR, Staurowsky EJ, Baca L, Davis LR, Pewewardy C. 2002. Of polls and race prejudice: sports illustrated's errant “Indian wars”. Journal of Sport and Social Issues. 26(4):381–402.

- Marsden, M. 2003. The Woven Universe. C. Royal, editor. Masterton (NZ): Printcraft ‘81 Ltd.

- Mercer P. 2016 Oct 12. New Zealand rugby battered by scandal. BBC News. [accessed 2016 Oct 16]. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-37627971.

- Morton J. 2016 Sep 9. Rugby got it wrong on scandal: Tew. New Zealand Herald. [accessed 2016 Sep 16]. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/sport/news/article.cfm?c_id=4&objectid=11706230.

- Myers B, Pringle JK, Giddings LS. 2013. Reflections from EDI conferences: consistency and change. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal. 32(4):455–463. doi: 10.1108/EDI-11-2012-0100

- New Zealand Māori Rugby Board. 2017. Annual report. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Rugby.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Frels n. 2016. Seven steps to a comprehensive literature review: a multimodal and cultural approach. London (UK): Sage.

- Palmer FR. 2006. Māori sport and its management. In: Leberman, Collins, Trenberth, editors. Sport business management in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Albany (NY): Cengage; p. 62–88.

- Palmer FR. 2016. Stories of haka and women’s rugby in Aotearoa New Zealand: weaving identities and ideologies together. The International Journal of the History of Sport. 33(17):2169–2184. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2017.1330263

- Palmer FR, Masters TM. 2010. Māori feminism and sport leadership: exploring Māori women’s experiences. Sport Management Review. 13(4):331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2010.06.001

- Pihama L, Cram F, Walker S. 2002. Creating methodological space: a literature review of Kaupapa Māori research. Canadian Journal of Native Education. 26(1):30–43.

- Rankin-Wright AJ, Hylton K, Norman L. 2016. Off-colour landscape: framing race equality in sport coaching. Sociology of Sport Journal. 33(4):357–368. doi: 10.1123/ssj.2015-0174

- Rattue C. 2016 Aug 5. Chiefs must front to stripper-gate. New Zealand Herald. [accessed 2016 Aug 16]. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/sport/news/article.cfm?c_id=4&objectid=11687765.

- Rodriguez L, George JR, McDonald B. 2017. An inconvenient truth: why evidence-based policies on obesity are failing Māori, Pasifika and the anglo working class. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 12(2):192–204.

- Romanos J. 2007. Winning ways: champion New Zealand coaches reveal their secrets. Wellington (NZ): Trio Books.

- Sawrikar P, Muir K. 2010. The myth of a ‘fair go’: barriers to sport and recreational participation among Indian and other ethnic minority women in Australia. Sport Management Review. 13(4):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2010.01.005

- Schulenkorf N, Sherry E, Rowe K. 2016. Sport for development: an integrated literature review. Journal of Sport Management. 30(1):22–39. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2014-0263

- Sherwood S. 2016 Jul 7. Racially abused Fijian rugby player Peni Manumanuniliwa: ‘All I want is for my voice to be heard’. Stuff. https://i.stuff.co.nz/sport/rugby/81849747/Bronson-Munro-banned-from-rugby-for-40-weeks-for-racially-abusing-Fijian-player-Peni-Manumanuniliwa.

- Sherwood S, Smith T, Egan B, Mathewson N. 2015 Jul 28. Fijian rugby player Sake Aca speaks of anguish at racial taunts. Stuff. https://i.stuff.co.nz/sport/rugby/70603934/fijian-rugby-player-sake-aca-speaks-of-anguish-at-racial-taunts.

- Smith B, Sparkes AC. 2013. Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: from process to product. London: Routledge.

- Smith GH. 1997. Kaupapa Māori as transformative praxis [Unpublished PhD Thesis]. University of Auckland.

- Smith LT. 1999. Decolonising methodologies research and indigenous people. Dunedin (NZ): University of Otago Press.

- Smith LT. 2006. Researching in the margins issues for Māori researchers a discussion paper. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 2(1):4–27. doi: 10.1177/117718010600200101

- Smith LT, Maxwell TK, Puke H, Temara P. 2016. Indigenous knowledge, methodology and mayhem: what is the role of methodology in producing Indigenous insights? A discussion from mātauranga Māori.

- Spaaij R. 2012. Beyond the playing field: experiences of sport, social capital, and integration among Somalis in Australia. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 35(9):1519–1538. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.592205

- Spaaij R. 2015. Refugee youth, belonging and community sport. Leisure Studies. 34(3):303–318. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2014.893006

- Spaaij R, Magee J, Jeanes R. 2014. Sport and social exclusion in global society. London: Routledge.

- Spoonley P, Taiapa C. 2009. Sport and cultural diversity: responding to the sports and leisure needs of immigrants and ethnic minorities in Auckland. Auckland (NZ): Massey University & Auckland Regional Physical Activity & Sport Strategy.

- Sport New Zealand. 2016. Sports commit to diversity and inclusion through #sportforeveryone. https://www.sportforeveryone.co.nz/2017/05/test-care /.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2017. New Zealand population summary figures 1991–2017. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Government.

- Te Puni Kōkiri. 2006a. Māori in rugby. Wellington (NZ): Te Puni Kokiri.

- Te Puni Kōkiri. 2006b. Māori in sport and active leisure. Wellington (NZ): Te Puni Kokiri.

- Te Puni Kōkiri. 2012. RWC 2011 media highlights. Wellington (NZ): Te Puni Kokiri.

- Te Rito P. 2006. Leadership in Māori, European cultures and in the world of sport. MAI Review LW. 1(1):19.

- Te Rito PR. 2007. Māori leadership: what role can rugby play? [Doctoral dissertation]. Auckland University of Technology.

- Watson G. 2007. Sport and ethnicity in New Zealand. History Compass. 5(3):780–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00423.x

- Webster J, Watson RT. 2002. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly. 26:xiii–xxiii.