ABSTRACT

The Five Ways to Wellbeing were developed in 2008 as a set of simple daily practices for individuals to improve their wellbeing. While there is some evidence to support the association between individual practices and wellbeing, it is unknown whether engaging in multiple practices – and in certain combinations – is associated with higher levels of wellbeing. A survey was undertaken with 10,012 adults throughout Aotearoa, New Zealand, to assess individual wellbeing and participation in the Five Ways to Wellbeing (Connect, Give, Take Notice, Keep Learning and Be Active). Wellbeing was assessed with the Flourishing Scale (Md = 46, IQR 39–49). Three objectives explored the cross-sectional association between the Five ways to Wellbeing and wellbeing: (1) multiple wellbeing practices and wellbeing, (2) clustering of multiple wellbeing practices, and (3) wellbeing practices as predictors of wellbeing. Results show that levels of wellbeing increased with each additional practice (rho = .53, p < .001), regardless of the combination. However, the most important predictors of wellbeing were Keep Learning (β = .23, p < .001) and Take Notice (β = .22, p < .001). Studies investigating ways to increase participation in the Five Ways to Wellbeing are warranted to promote wellbeing in Aotearoa.

Introduction

In this research, wellbeing is defined as a combination of the happiness and satisfaction one has with life and the meaning they attribute to it. Individuals with high wellbeing experience high levels of both positive feelings (e.g. cheerful, calm, satisfied) and positive functioning (e.g. autonomy, competence, engagement) (Huppert and So Citation2013). These characteristics of human functioning are important both for the individual and society. Individuals with higher wellbeing tend to have better health and longevity (Keyes Citation2002; Seligman Citation2008; Huppert Citation2009; Boehm and Kubzansky Citation2012; Park et al. Citation2016), are better equipped to cope with adversity, are more productive and have stronger social relationships (Diener Citation2000; Graham Citation2009). Individuals with low wellbeing may not present with a medically diagnosable disease (Keyes Citation2002, Citation2005, Citation2007), however, they often report poorer overall quality of life and when they are ill or injured they recover more slowly (Perry et al. Citation2010). The wellbeing of a population or workforce impacts on health and social care expenditure as well as overall economic productivity of a nation or organisation (Diener and Seligman Citation2004).

Many adults in Aotearoa have low levels of wellbeing with just one in four reporting high wellbeing (Mackay, Schofield, et al. Citation2015). It is acknowledged that different study populations and cultural expressions of wellbeing make cross-country comparisons of wellbeing difficult (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. Citation2016), however, international research has also demonstrated low wellbeing in some countries. A study of wellbeing in 22 European nations found that rates of high wellbeing were as low as 9.3% (Portugal) and up to 40.6% (Denmark) (Huppert and So Citation2013). A similar study in the United States found that only 20% of the population reported high levels of wellbeing (Keyes Citation2007). The prevalence of wellbeing also differs across different demographic groups. For example, the prevalence of wellbeing increases with age, and income, however, there appears to be no significant difference in levels of wellbeing between men and women (Huppert and So Citation2009; Keyes and Westerhof Citation2012; Mackay, Schofield, et al. Citation2015). These findings highlight the need for targeted approaches to improve individual and national wellbeing.

In 2008, the Centre for Wellbeing at the New Economics Foundation developed the ‘Five Ways to Wellbeing’, a public health message promoting evidence-based practices for improving personal wellbeing (Aked et al. Citation2009). They are: Connect, Be Active, Take Notice, Keep Learning, and Give. In Aotearoa, the Five Ways to Wellbeing message has been adopted by the Mental Health Foundation, Health Promotion Agency, and Canterbury’s All Right? campaign as a framework for wellbeing promotion. These organisations have produced several resources and promotional materials to help individuals, families, workplaces, and communities to improve their wellbeing (Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand Citation2019).

Māori concepts of health and wellbeing in Aotearoa are well aligned with the Five Ways to Wellbeing as they are holistic in scope and able to be adapted and individually expressed. The pillars of hauora (health and wellbeing) that form the Māori health model Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie Citation1984) can relate to each of the Five Ways to Wellbeing. For example, taha tinana (physical health) can be connected to Be Active, taha whanau (family health) can be connected to Connect and Give, taha hinengaro (mental health) can be connected to Take Notice, Be Active, Connect, Give and Keep Learning and taha wairua (spiritual health) can be connected to Take Notice, Give, Connect and Keep Learning. While not developed specifically for Aotearoa, the Five Ways to Wellbeing has been successfully implemented and used in this context. It is appropriate for use in this research due to the universally applicable messages suitable for the socio-demographically and culturally diverse population present in Aotearoa.

As Aotearoa moves towards measuring societal progress with indicators of wellbeing, such as Indicators Aotearoa, greater understanding of wellbeing-promoting activities in Aotearoa is needed. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to understand the cross-sectional associations between participation in each of the Five Ways to Wellbeing practices (Connect, Give, Take Notice, Keep Learning and Be Active) and wellbeing. Specific objectives are to: (i) determine empirically whether practicing one, some, or all the Five Ways to Wellbeing are associated with higher levels of wellbeing, (ii) investigate whether these Five Ways to Wellbeing practices cluster together, and (iii) examine which Five Ways to Wellbeing practice is the best predictor of wellbeing. This information could inform and develop future interventions and targeted campaigns.

Materials and methods

The Sovereign Wellbeing Index (SWI) was an online survey undertaken in New Zealand in 2012 and again in 2014. The survey was designed to specifically measure a broad range of individual wellbeing indicators alongside measures of health, lifestyle, and socio-demographics. This paper uses data from the 2014 survey of the SWI. Some questions in the 2014 survey differed from the 2012 survey and thus statistical comparison between the two time points was not possible. Only details relevant to the present analyses are reported henceforth; full details of 2014 SWI methodology are presented in the SWI Methodology report (Mackay, Prendergast, et al. Citation2015).

Participants

The New Zealand office of TNS Global, an international market research company, recruited participants from one of the largest research panels in New Zealand (Smile City Citation2012). The 2014 SWI used a two-stage process to select the sample from the research panel. The first stage involved selecting all panel members who participated in the 2012 survey. A total of 10,009 adults participated in 2012; all these participants were invited to participate in the 2014 survey, of which 4,435 consented and completed the 2014 survey (44%). The second stage involved selecting a random sample of panel members that did not participate in 2012; with replacement, to reach the intended target of 10,000 participants. Panel members aged under 40 years were marginally oversampled to achieve a sample representative of New Zealand adults over 18 years. Stage two invitations were sent to 53,628 panel members that did not participate in 2012. Of these invitations, a total of 5,577 adults participated (10%). Overall, the SWI collected survey responses from 10,012 adults in 2014 (4,435 returning and 5,577 new participants).

Procedures

Each selected panel member was sent an email invitation by the panel provider. Participants were directed to the web-based survey where a study information sheet was provided (ethical approval granted by the AUT Ethics Committee: 12/201). Participants who agreed to participate proceeded to the anonymous web-based survey. The survey contained the full personal and social wellbeing module from the European Social Survey, Round 6 (European Social Survey Citation2012), along with additional items to assess wellbeing, health, lifestyle behaviours, and demographics. Only those items relevant for the present analyses are described below.

Wellbeing

Wellbeing was measured using the Diener et al. (Citation2010) eight-item Flourishing Scale to assess dimensions of wellbeing, including: competence, self-acceptance, meaning and relatedness, optimism, giving, and engagement (Diener et al. Citation2010). Each item is phrased in a positive direction with a 7-point response scale from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. Responses to the eight items were summed so that scores range from 8 to 56, with higher scores denoting higher levels of wellbeing. The scale’s one-factor structure has been demonstrated (Hone et al. Citation2014), and according to Diener et al. (Citation2010), the Flourishing Scale has good internal consistency, with a Cronbach alpha coefficient reported of .87. In this current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was .92. The correlation matrix was inspected for patterns of correlation between individual items of the Flourishing Scale and Five Ways to Wellbeing. The minimum correlation among items of the Flourishing Scale was between Social Relationships and Competence (r = .497, p < .001); all of the Five Ways to Wellbeing had lower correlations with singular items of the Flourishing Scale (range r = .081 – .452) (Supplementary Table 1).

Flourishing is the term used to describe high levels of wellbeing in the field of positive psychology (Keyes Citation2002). However, in Aotearoa, the use of the term flourishing outside of the positive psychology field is rare and thus wellbeing has been used by the authors.

Five Ways to Wellbeing

The Five Ways to Wellbeing incorporates items designed to assess engagement in individual wellbeing promoting activities these include: Connect, Give, Take Notice, Keep Learning and Be Active. Participation and non-participation in Connect, Give, Take Notice and Keep Learning was determined using thresholds reported by Harrison et al. (Citation2016) (). Participation in Be Active was determined by responses to a set of items developed for the purposes of the SWI; the total number of days per week were summed across different exercise activities, with three or more days per week classified as endorsing Be Active (). Three or more days per week was selected as the minimum number of days likely to achieve health benefit (World Health Organization Citation2010; Hamer et al. Citation2017). The final variables for analysis were a dichotomy of participation and non-participation for each wellbeing practice.

Table 1. Five Ways to Wellbeing classification.

Risk of bias

Prior to analysis, differences between returning and new participants were examined to establish whether there was bias in returning participants. A Chi-square test for independence (with Yates Continuity Correction) indicated no significant association between participant type (returning and new participant) and achievement of Connect, Give, or Keep Learning (p >.05). However, a very small significant association was found between participant type and achievement of Take Notice (achieved by 58% returning and 53% new participants), χ2 (1, n = 9828) = 24.69, p < .001, phi =.05, and Be Active (achieved by 61% returning and 59% new participants), χ2 (1, n = 9828) = 4.34, p < .05, phi = −.02. The Mann–Whitney U test indicated a very small, but statistically significant, difference in wellbeing scores between returning (Md = 46, n = 4,313) and new participants (Md = 45, n = 5,393), U = 11109813, z = −3.798, p < .001, r = .04. Although statistically significant, the effect size of the differences was considered very small and thus returning and new participants were combined for further analyses.

Data analysis

All data analyses were undertaken using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), with the alpha set at p < .05 to determine statistical significance. Variables were examined for accuracy of data entry, distributions, missing values, and problematic outliers. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality indicated a non-normal distribution of wellbeing scores (p < .001), and inspection of the histogram identified significant negative skewness, thus non-parametric tests were used were appropriate.

Multiple wellbeing practices

Due to the non-normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine whether wellbeing scores were higher among those who participated in each individual practice. To determine whether participating in multiple wellbeing practices was associated with wellbeing, the prevalence rates of the sample engaging in zero to five wellbeing practices were calculated. Spearman’s rank order correlation was used to determine the strength of the relationship between the number of achieved wellbeing practices and wellbeing scores.

Clustering of wellbeing practices

Clustering of wellbeing practices was examined by comparing the observed and expected prevalence of the different possible combinations for participation and non-participation of all wellbeing practices (n = 32). The observed prevalence was calculated as the proportion of the sample in each combination. The expected prevalence of a specific combination was calculated based on the individual probabilities of each wellbeing practice; by multiplying the observed prevalence of each individual wellbeing practice in a combination (Poortinga Citation2007). Clustering ratios (O/E) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated as observed prevalence over expected prevalence and were used to determine whether wellbeing practices clustered or occurred independently in the sample. Ratios >1 indicated clustering (i.e. the observed prevalence is higher than the expected prevalence); ratios of <1 indicated that the wellbeing practices occurred independently (Poortinga Citation2007). Median wellbeing scores with interquartile range were calculated for all possible combinations.

Predictors of wellbeing

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to evaluate the ability of the Five Ways to Wellbeing to predict wellbeing, after controlling for the influence of age, gender and income quintile. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity. Age (years), gender (male, female), and income quintile (5 levels) were entered in Model 1; the Five Ways to Wellbeing (non-participation/participation) were added simultaneously in Model 2.

Results

The 2014 SWI collected survey responses from 10,012 adults (4,435 returning and 5,577 new participants). Participants were excluded from further analysis if they were missing data from any of the five wellbeing practices (8.8%, n = 880). Thus, valid data were available from 9,132 (48% Male) participants. Of these, wellbeing scores were available for 8,997 participants (Md = 46, IQR 39–49). provides a summary of the participant characteristics.

Table 2. Sample characteristics.

Multiple wellbeing practices

Of the total sample, 64% practiced Connect, 68% practiced Give, 55% practiced Take Notice, 72% practiced Keep Learning, and 61% practiced Be Active. There were statistically significant differences in wellbeing scores between those that participated and those that did not participate in each individual wellbeing practice (). The greatest difference in wellbeing scores between participation and non-participation was for Take Notice (moderate effect), followed by Keep Learning (moderate effect).

Table 3. Wellbeing practices and wellbeing.

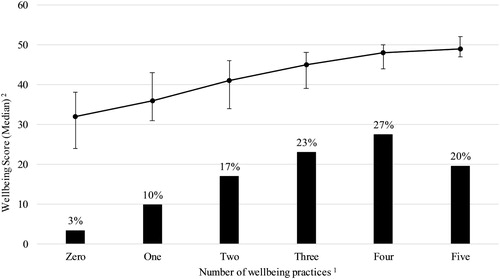

Overall, 3% did not participate in any of the Five Ways to Wellbeing, and 19% participated in all five practices (). Wellbeing scores increased with each additional wellbeing practice: zero (Md = 32, n = 308); one (Md = 36, n = 894); two (Md = 41, n = 1545); three (Md = 45, n = 2097); four (Md = 48, n = 2503); five (Md = 49, n = 1785). The strength of this positive correlation was large (Spearman rho = .53, n = 8997, p < .001).

Clustering of wellbeing practices

Clustering was observed for eight of the thirty-two possible combinations, with ratios ranging from 0.4–5.9 (ratios >1 indicate clustering). presents the observed and expected prevalence, clustering ratios, and the wellbeing scores for these eight wellbeing practice combinations (full results are presented in Supplementary Table 2). The greatest degree of clustering was observed for those who did not participate in any wellbeing practices. That is, the observed prevalence of not participating in any of the Five Ways to Wellbeing practices (3.4%) was greater than could have been expected based on the individual probabilities of not participating in each of the five practices (0.6%; cluster ratio 5.9). Similarly, clustering was observed for participating in all Five Ways to Wellbeing practices (cluster ratio 1.9). Aside from participating in none or all wellbeing practices, one four-practice combination (Connect, Give, Take Notice, and Keep Learning), one two-practice combination (Connect and Be Active), and four single-practice combinations (all except take notice) occurred more frequently in the population than would be expected.

Table 4. Combinations of wellbeing practices that cluster together.

Predictors of wellbeing

presents the results of the hierarchical multiple regression. Age, gender and income were entered as Model 1, explaining 7.6% of the variance in wellbeing score. After entry of the Five Ways to Wellbeing in Model 2, the total variance explained by the whole model was 35.1%, F(8, 6663) = 451.402, p < .001. These wellbeing practices explained an additional 27.6% of the variance in wellbeing score, after controlling for age, gender, and income, R squared change = .276, F change (5, 6663) = 566.82, p < .001. In the final model, all wellbeing practices were statistically significant, with Keep Learning (β = .23, p < .001) and Take Notice (β = .22, p < .001) recording the highest standardised coefficient values. These results indicate that between non-participation to participation for Keep Learning, there is a predicted 4.37 difference in wellbeing score, controlling for all other variables in the equation.

Table 5. Hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting wellbeing score.

Discussion

Overall, the results from this study show that participating in any of the Five Ways to Wellbeing is associated with higher levels of wellbeing. The data showed incremental increases in wellbeing scores for each additional wellbeing practice. Clustering analysis showed that some combinations occur more frequently than would be expected, that is, some combinations of the wellbeing practices are more commonly achieved together. This was particularly the case for non-participation of all five practices and participation of all five practices. However, the clear majority of two-, three-, and four-practice combinations occur less often than would be expected, which indicate that wellbeing practices occur independently. In the final model, hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess the ability of the Five Ways to Wellbeing to predict wellbeing, after controlling for the effects of age, gender and household income. All the Five Ways to Wellbeing were able to predict wellbeing, with the greatest unique contribution from Keep Learning and Take Notice, and the least from Be Active.

The Five Ways to Wellbeing were designed with respect to personal choice for practices that could be taken to improve personal wellbeing, and it was suggested that there is no single pathway to wellbeing (Aked et al. Citation2009). Findings from this study would support this assertion that there are multiple ways to achieve high levels of wellbeing; but practicing more of the Five Ways to Wellbeing, in whichever combination, is associated with higher levels of wellbeing. These findings build upon earlier analysis of the 2012 SWI sample that found that participation in each individual wellbeing practice was associated with higher wellbeing (Hone et al. Citation2014) and Take Notice and Keep Learning were the greatest predictors of flourishing among working adults (Hone et al. Citation2015). Findings also support reports from the European Social Survey where participation in each practice was associated with increased life satisfaction (Harrison et al. Citation2016). What is unclear from the current study, and previous studies (Hone et al. Citation2014; Hone et al. Citation2015; Harrison et al. Citation2016), is whether there is a causal pathway from engagement in the Five Ways to Wellbeing and wellbeing. It is unknown whether these wellbeing practices are characteristics of individuals with high wellbeing, or whether engagement in these practices leads to improved wellbeing; to test this, intervention-control studies are needed.

Overall, the highest levels of wellbeing were observed for Take Notice (Md 48, IQR 44–51); also, the largest difference in wellbeing between participation and non-participation in any practice was observed for Take Notice (moderate effect size). In the regression model, Take Notice made the second largest contribution, after Keep Learning. The prevalence rate for Take Notice in this sample was much lower than European countries; for example, 75% in Germany and 63% in United Kingdom participated in Take Notice (Harrison et al. Citation2016), compared with just 55% in this sample. Taking time to notice one’s surroundings, or being mindful, is associated with positive mental health benefits (Brown and Ryan Citation2003). Evidence supporting the importance of Taking Notice stems from mindfulness intervention research. Mindfulness can be described as one’s awareness of self and surroundings in a given moment. Several studies have found that mindfulness training (to be aware of sensations, thoughts, and feelings) can promote wellbeing for several years (Brown and Ryan Citation2003; Carmody and Baer Citation2008; Huppert Citation2009). Awareness of what is happening at a given time is also positively linked to wellbeing because it allows one to appreciate their surroundings and reflect on life priorities (Fredrickson Citation2003). This awareness or mindfulness can facilitate the fulfilment of one’s basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, relatedness (Ryan et al. Citation2013) and reduce symptoms of anxiety and stress (Zargarzadeh and Shirazi Citation2014).

On the other hand, the lowest levels of wellbeing were observed for non-participation in Keep Learning (28% of the sample). Keep Learning also made the greatest unique contribution to the regression model, with a predicted 4.36 gain in wellbeing score for participation in Keep Learning versus non-participation (holding all other predictors constant). Research has shown that learning in general has a positive effect on wellbeing, but specifically, different types of learning promote different types of wellbeing. For instance, work-related learning positively influences economic wellbeing, while learning for personal interest positively influences social wellbeing (Desjardins Citation2001). Life-long learning has been shown to aid recovery from mental health issues and coping in stressful circumstances, such as chronic illness and disability (Hammond Citation2004). A study by Feinstein and Hammond (Citation2004) found that academic learning is not associated with changes in health behaviours, depression, or civic activity; however, is associated with changes in social and political attitudes. They also found that employer-provided learning opportunities are positively associated with greater life satisfaction and race tolerance and negatively associated with authoritarian attitudes. Lastly, they argued that leisure learning can increase the likelihood of giving up smoking, civic participation, and regular exercise.

Despite the consistent evidence base for the importance of social connections for wellbeing, the findings of this study show that just 15% of the sample participated in both Connect and Give in combination, regardless of participation or non-participation in the other Five Ways to Wellbeing practices. Several studies have clearly demonstrated that having strong supportive relationships and broad networks are important for wellbeing. Social connectedness has been shown to predict greater psychological wellbeing (Brugha et al. Citation2005; Armstrong and Oomen-Early Citation2009) and this can hold over time (Jose and Pryor Citation2010). A core component of strong relationships is the act of providing help and support for others (Rilling et al. Citation2007). Research suggests that receiving support is beneficial to one’s health (Pantell et al. Citation2013; Chen and Feeley Citation2014; Hill et al. Citation2014); however, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that giving support may be more beneficial than receiving support. For example, giving support is associated with a lower mortality risk whereas receiving support has no significant effect on mortality (Brown et al. Citation2003; Krause Citation2006). Furthermore, individuals that help others are more likely to have greater self-esteem, a greater sense of self-worth, and rate their health more positively than those who do not help and support others (Krause et al. Citation1992; Krause Citation2016).

Many cultures have an intrinsic and culturally specific understanding of what is necessary to achieve individual, family and community wellbeing (Wright and Pascoe Citation2015). For Māori, this is evidenced by Te Whare Tapa Whā, and for Pacific, models of health such as the Fonofale framework, Te Vaka Atafaga health assessment model, the Kalaka concept and Fa’afaletui model, among others. Connections with others and giving with reciprocity are critical elements of these models and are fundamental to the partnership principle of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Interventions to improve wellbeing at a population level that focus on reciprocity and partnership, with respectful appreciation of cultural understandings of wellbeing, will likely benefit wellbeing through improving the co-occurrence of the wellbeing practices Give and Connect.

Interventions to promote Give and Connect may also reduce prevalence rates of isolation and loneliness in Aotearoa. Loneliness and isolation, both actual and perceived, are clear predictors of poor mental health outcomes, including but not limited to clinical depression and anxiety (Cacioppo et al. Citation2010; Mustafa et al. Citation2018). Loneliness and isolation are also linked to a range of poor physical health outcomes across all age groups, such as poor dietary and hygiene behaviours (Rew Citation2000; Cornwell and Waite Citation2009). Further research to explore the causal relationship between the practices of giving and connecting and the prevalence rates isolation and loneliness is needed.

The benefits of exercise for physical wellbeing are well documented with extensive evidence to support the role exercise plays in reducing the risk of many non-communicable diseases (Kohl et al. Citation2012; Lee et al. Citation2012). Exercise has also been found to be important for wellbeing (Prendergast et al. Citation2016), particularly as an effective treatment for reducing the symptoms of mild to moderate major depressive disorder (Meyer et al. Citation2016). Intervention studies have shown that engaging in exercise can improve mood, and lower confusion, anger, and tension (Janisse et al. Citation2004; Penedo and Dahn Citation2005; Meyer et al. Citation2016). However, the results from this study indicate that while levels of wellbeing were greater among those who achieved Be Active compared with those who didn’t, the magnitude of the difference is small. It is possible that even greater levels of physical activity are required (more than 3 days per week) – or specific types and contexts – for a larger effect on wellbeing to be seen.

Findings from this study indicate that participating in multiple wellbeing practices was associated with higher levels of wellbeing. There are many opportunities for integrating multiple wellbeing practices in the same activity. For example, going for a walk in the park with friends meets Be Active and Connect. Activities such as yoga, which incorporates Be Active and Take Notice, has been shown to be beneficial for wellbeing (Ivtzan and Papantoniou Citation2014). Another example is joining a community garden, where research has shown that community gardens are excellent promotors of individual and social wellbeing (Egli et al. Citation2016), and through regular, sustained participation community gardening has the potential to meet all five wellbeing practices (Egli et al. Citation2016). Wellbeing interventions that promote participation in two or more of the Five Ways to Wellbeing practices together may yield greater improvements in wellbeing, however further research is needed.

Overall, this study provides empirical evidence to support promotion of the Five Ways to Wellbeing message. It goes beyond earlier research that has determined the wellbeing levels of each of the practices independently (Hone et al. Citation2014), to show that engaging in more practices, in whatever combination, is associated with greater wellbeing. Furthermore, it confirms the importance of Take Notice and Keep Learning as important predictors of wellbeing (Hone et al. Citation2015). A methodological strength of the study was the large sample size (10,000 respondents represents approximately 0.3 percent of the total adult population in New Zealand) and the ethnic make-up is comparable to the composition of ethnicities in Aotearoa.

Despite the strengths of the study, there are some limitations to this evidence. Firstly, the data were cross-sectional, so causality cannot be implied. It is unknown whether these practices promote wellbeing, or whether people with high levels of wellbeing engage in these behaviours. Intervention studies that specifically test the benefit of the Five Ways to Wellbeing for improving wellbeing in a range of populations are needed. The Flourishing Scale used as the dependent outcome measure of wellbeing contains items that relate to the latent constructs of some of the Five Ways to Wellbeing (e.g. Social Relationships and Give). As such, regression coefficients may be inflated for related constructs. However, Take Notice and Keep Learning explained the greatest amount of variance in the wellbeing outcome, despite being only moderately correlated with individual items of the wellbeing scale (r = .199 – .418). Furthermore, the results of the analyses are dependent on the thresholds used to classify participation in wellbeing practices; this process is arbitrary given the lack of objective support for thresholds. However, for consistency, thresholds reported by Harrison et al. (Citation2016) were replicated in this study. It is also possible that there are differences in patterns of responding between the frequency-based response scales (Connect and Be Active) and Likert-type scales (Give, Take Notice, and Keep Learning) that may impact the results of clustering analysis and relationships with wellbeing.

Finally, approximately one-fifth of the sample was not included in the regression analyses due to missing income data. A missing value analysis was performed to determine whether responses were missing at random. A separate variance t-test revealed a very small difference in wellbeing scores (mean difference = 1.0, t(3495) = 4.7, p < .001, eta squared = .002) between those who provided income details and those who did not, therefore household income was retained in the regression model.

Conclusion

This research has shown there is a positive association between the participation of Five Ways to Wellbeing practices and wellbeing. While the findings support the notion that there is no one pathway to wellbeing, participation in Take Notice and Keep Learning corresponded with the highest levels of wellbeing and were the greatest unique predictors of wellbeing. These results provide empirical support for the Five Ways to Wellbeing; however, intervention research is needed to test their efficacy for improving wellbeing with specific attention given to the unique cultural and socio-demographic context in Aotearoa.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the host institution’s ethics committee Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (ref 12/201).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplementary Table 2

Download MS Word (23.4 KB)Supplementary Table 1

Download MS Word (19.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Sovereign’s support as the funder of this research. KP was supported by a Sovereign Wellbeing Index Doctoral Scholarship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Lisa Mackay http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7344-5794

Victoria Egli http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3306-7709

Laura-Jane Booker http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8741-5721

Kate Prendergast http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8439-4606

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aked J, Marks N, Cordon C, Thompson S. 2009. Five ways to wellbeing: A report presented to the Foresight project on communicating the evidence base for improving people’s well-being. London: Nef.

- Armstrong S, Oomen-Early J. 2009. Social connectedness, self-esteem, and depression symptomatology among collegiate athletes versus non-athletes. J Am Coll Health. 57(5):521–526.

- Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. 2012. The heart’s content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin. 138(4):655–691.

- Brown KW, Ryan RM. 2003. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 84(4):822–848.

- Brown SL, Nesse RM, Vinokur AD, Smith DM. 2003. Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychol Sci. 14(4):320–327.

- Brugha TS, Weich S, Singleton N, Lewis G, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R, Meltzer H. 2005. Primary group size, social support, gender and future mental health status in a prospective study of people living in private households throughout Great Britain. Psychol Med. 35(5):705–714.

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. 2010. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 25(2):453–463.

- Carmody J, Baer RA. 2008. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 31(1):23–33.

- Chen Y, Feeley TH. 2014. Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults. J Soc Pers Relat. 31(2):141–161.

- Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. 2009. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 50(1):31–48.

- Desjardins R. 2001. The effects of learning on economic and social well-being: A comparative analysis. Peabody J Educ. 76(3–4):222–246.

- Diener E. 2000. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am Psychol. 55(1):34–43.

- Diener E, Seligman ME. 2004. Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 5(1):1–31.

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D-W, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. 2010. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 97(2):143–156.

- Durie MH. 1984. “Te taha hinengaro”: An integrated approach to mental health. Community Mental Health in New Zealand. 1(1):4–11.

- Egli V, Oliver M, Tautolo E-S. 2016. The development of a model of community garden benefits to wellbeing. Prev Med Rep. 3:348–352.

- European Social Survey. 2012. ESS Round 6 Source Questionnaire. London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys, City University London.

- Feinstein L, Hammond C. 2004. The contribution of adult learning to health and social capital. Oxf Rev Educ. 30(2):199–221.

- Fredrickson BL. 2003. The value of positive emotions. Am Sci. 91(4):330–335.

- Graham C. 2009. The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hamer M, Biddle SJH, Stamatakis E. 2017. Weekend warrior physical activity pattern and common mental disorder: A population wide study of 108,011 British adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 14(1):96–101.

- Hammond C. 2004. Impacts of lifelong learning upon emotional resilience, psychological and mental health: Fieldwork evidence. Oxf Rev Educ. 30(4):551–568.

- Harrison E, Quick A, Abdallah S, editors. 2016. Looking through the wellbeing kaleidoscope. London: New Economics Foundation.

- Hill PL, Weston SJ, Jackson JJ. 2014. Connecting social environment variables to the onset of major specific health outcomes. Psychol Health. 29(7):753–767.

- Hone L, Jarden A, Duncan S, Schofield G. 2015. Flourishing in New Zealand Workers. J Occup Environ Med. 57:973–983. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000508.

- Hone L, Jarden A, Schofield G. 2014. Psychometric properties of the flourishing scale in a New Zealand sample. Soc Indic Res. 119(2):1031–1045.

- Huppert FA. 2009. Psychological well-being: evidence regarding its causes and consequences. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 1(2):137–164.

- Huppert FA, So T. 2009. What percentage of people in Europe are flourishing and what characterises them? OECD/ISQOLS meeting “Measuring subjective well-being: an opportunity for NSOs?” Florence - July 23/24, 2009.

- Huppert FA, So TT. 2013. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc Indic Res. 110(3):837–861.

- Ivtzan I, Papantoniou A. 2014. Yoga meets positive psychology: Examining the integration of hedonic (gratitude) and eudaimonic (meaning) wellbeing in relation to the extent of yoga practice. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 18(2):183–189.

- Janisse HC, Nedd D, Escamilla S, Nies MA. 2004. Physical activity, social support, and family structure as determinants of mood among European-American and African-American women. Women Health. 39(1):101–116.

- Jose PE, Pryor J. 2010. New Zealand youth benefit from being connected to their family, school, peer group and community. Youth Stud Aust. 29(4):30–37.

- Keyes CL. 2002. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 43(2):207–222.

- Keyes CL. 2005. Mental illness and/or mental health? investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 73(3):539–548.

- Keyes CL. 2007. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 62(2):95–108.

- Keyes CL, Westerhof GJ. 2012. Chronological and subjective age differences in flourishing mental health and major depressive episode. Aging Ment Health. 16(1):67–74.

- Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S. 2012. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 380(9838):294–305.

- Krause N. 2006. Church-based social support and mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 61(3):S140–S146.

- Krause N. 2016. Providing emotional support to others, self-esteem, and self-rated health. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 65:183–191.

- Krause N, Herzog AR, Baker E. 1992. Providing support to others and well-being in later life. J Gerontol. 47(5):P300–P311.

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. 2012. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 380(9838):219–229.

- Mackay LM, Prendergast K, Jarden A. 2015. Sovereign wellbeing Index: methodology report Wave 2, 2014. Auckland: Auckland University of Technology.

- Mackay LM, Schofield GM, Jarden A, Prendergast K. 2015. Sovereign wellbeing Index: 2015. Auckland: Auckland University of Technology.

- Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand. 2019. Wellbeing. Wellington, NZ; [accessed 2019 Jan 10]. https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/home/ways-to-wellbeing/.

- Meyer JD, Koltyn KF, Stegner AJ, Kim J-S, Cook DB. 2016. Influence of exercise intensity for improving depressed mood in depression: a dose-response study. Behav Ther. 47(4):527–537.

- Mustafa N, Khanlou N, Kaur A. 2018. Eating disorders among Second-Generation Canadian South Asian female Youth: An intersectionality approach toward exploring cultural conflict, dual-identity, and mental health. In: Pashang S, Khanlou N, Clarke J, editors. Today’s Youth and Mental Health: Hope, Power, and Resilience. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 165–184.

- Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. 2013. Social isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. 103(11):2056–2062.

- Park N, Peterson C, Szvarca D, Vander Molen RJ, Kim ES, Collon K. 2016. Positive psychology and physical health. Am J Lifestyle Med. 10(3):200–206.

- Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. 2005. Exercise and well-being: A review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 18(2):189–193.

- Perry GS, Presley-Cantrell LR, Dhingra S. 2010. Addressing mental health promotion in chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Am J Public Health. 100(12):2337–2339.

- Poortinga W. 2007. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med. 44(2):124–128.

- Prendergast KB, Schofield GM, Mackay LM. 2016. Associations between lifestyle behaviours and optimal wellbeing in a diverse sample of New Zealand adults. BMC Public Health. 16(1):62–72.

- Rew L. 2000. Friends and pets as companions: Strategies for coping with loneliness among homeless youth. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 13(3):125–132.

- Rilling JK, Glenn AL, Jairam MR, Pagnoni G, Goldsmith DR, Elfenbein HA, Lilienfeld SO. 2007. Neural correlates of social cooperation and non-cooperation as a function of psychopathy. Biol Psychiatry. 61(11):1260–1271.

- Ryan RM, Huta V, Deci EL. 2013. Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. The exploration of happiness. Netherlands: Springer; p. 117–139.

- Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Pieterse ME, Drossaert CH, Westerhof GJ, De Graaf R, Ten Have M, Walburg J, Bohlmeijer ET. 2016. What factors are associated with flourishing? results from a large representative national sample. J Happiness Stud. 17(4):1351–1370.

- Seligman M. 2008. Positive health. Appl Psychol. 57:3–18.

- Smile City Ltd. 2012. ESOMAR: 27 Questions. Smile City Ltd.

- World Health Organization. 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. [accessed 2019 Jan 10]. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/.

- Wright PR, Pascoe R. 2015. Eudaimonia and creativity: The art of human flourishing. Camb J Educ. 45(3):295–306.

- Zargarzadeh M, Shirazi M. 2014. The effect of progressive muscle relaxation method on test anxiety in nursing students. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 19(6):607–612.