ABSTRACT

Questionnaires about alcohol use were administered to consenting Year 10 students at 10 secondary schools located in regions of Southland, Otago and Hawkes Bay (n = 579) to examine drinking patterns and attitudes about alcohol of 14–15-year-olds. The average age of first drink was 12.6 years, two years younger than previously reported, with no difference in age of first drink for different socioeconomic statuses or ethnicities. Fifty-four per cent self-reported having consumed alcohol, and 23% had done so at least once within the last four weeks, with 13% reported regularly drinking more than five drinks in one session. While almost half of the 14–15-year-olds in this study reported never drinking alcohol, 75 individuals reported regular binge drinking. This was more common for students in lower socioeconomic schools; almost a third of students in the lowest socioeconomic group reported drinking five or more drinks every time they drink. There may be benefits of alcohol education resources for children as young as 12 years.

Introduction

This study explored attitudes about alcohol and drinking behaviour amongst adolescents in New Zealand, a country with issues of excessive drinking (Conover and Scrimgeour Citation2013; Ministry of Health Citation2013a). The New Zealand Ministry of Health conducts surveys asking about frequency and volume of alcohol use (Ministry of Health Citation2013b) which analyse hazardous drinking or drinking behaviour that involves the risk of harm to the drinker (socially, physically, or mentally) or to others (Babor et al. Citation2011). Socioeconomic factors, gender and geographical location are predictors of New Zealanders developing alcohol misuse or dependency behaviour. Individuals living in lower socioeconomic areas are more likely to develop hazardous drinking patterns (Ministerial Committee on Drug Policy Citation2007). Although people from Māori and Pacific cultures are less likely to drink alcohol, those who do drink are more likely to develop hazardous drinking patterns (Ministry of Health Citation2016). The 2015–2016 survey found 80% of New Zealand adults drank alcohol in the past year, down from 84% in the 2006–2007 survey. In the same 2015–2016 survey, 57% of the New Zealand population aged between 15–17 years reported having an alcoholic drink in the past 12 months, a large decrease from 75% in 2006–2007 (Ministry of Health Citation2016). Many of the long-term consequences of early alcohol consumption are not completely understood (Maldonado-Devincci et al. Citation2010). Yet, there is convincing evidence that the brain is vulnerable to the harmful effects of alcohol at this developmental stage (Medina et al. Citation2008; Guerri and Pascual Citation2010; Roaten and Roaten Citation2012). Results from Squeglia and colleagues (Citation2009) suggest that youth who participated in heavy drinking behaviour for a period longer than one or two years had small changes in the neural organisation, ultimately showing greater abnormalities and differences in neurocognition. Some of these abnormalities include: brain structure and white matter volume when comparing 15–17-year-olds with and without alcohol use disorders (Medina et al. Citation2008); and brain activation in cognitive tasks (Squeglia et al. Citation2009). In addition to anatomical and functional changes in broad areas of the brain, Nixon and McClain (Citation2010) reported that alcohol interacts with the reward neurocircuitry of the adolescent brain, in turn encouraging maladaptive behaviours. Thus, the adolescent brain, because of its vulnerability to alcohol-induced harm, is a critical window for developing substance misuse and addiction (Nixon and McClain Citation2010).

Adolescent drinking behaviour

New Zealand’s Ministry of Health identified youth as a group at high-risk of alcohol harm. A binge drinking session, or ‘risky drinking’ is defined as five or more standard drinks in any one drinking session. Although people in the 18–24 year age bracket do not consume as much total alcohol as those in the 55–65 age bracket, they are more likely to consume large amounts of alcohol in any one drinking session (Ministerial Committee on Drug Policy Citation2007). Few studies and reports have examined the drinking behaviour of New Zealand youth (Adolescent Health Research Group Citation2008; Kypri et al. Citation2009; White Citation2013). As many as 61% of New Zealand secondary school students have been classified as regular drinkers (Adolescent Health Research Group Citation2008). In a survey of 2548 undergraduate New Zealand university students (average age 20.2 years), the self-reported recalled the average age of a first drink was 14.6 years (Kypri et al. Citation2009). The 2007–2008 New Zealand Alcohol and Drug Use Survey found that for people aged 16–64 years who had ever had an alcoholic drink, the median age for when they first tried alcohol was 16 years (Ministry of Health Citation2009). Nearly one in three people (31.9%) had tried alcohol at 14 years or younger. In that study 14 years or younger was the youngest age bracket to choose from, therefore the results may not accurately identify the age of first drink.

In a Youth Insights Survey, 40% of New Zealand Year 10 students aged between 14 and 15 years had consumed alcohol in the last month and 17% of these youth drinkers self-reported engaging in risky drinking behaviour within the last month (White Citation2013). Those who reported engaging in risky drinking were also more likely to consume alcohol weekly, without parents’ or caregivers’ knowledge. Māori were more likely to have experienced risky drinking and consumed alcohol in the last month than any other ethnicity involved in the study (White Citation2013). Eight per cent of students under the age of 16 years would classify as binge drinkers (Fleming et al. Citation2014).

A Youth 2000 survey series identified decreased New Zealand secondary school binge drinking between 2001 and 2012 (Adolescent Health Research Group Citation2012). The largest drop in alcohol consumption was in those aged 15–17 years, where the proportion fell from 75% in 2006–2007, to 59% in 2011–2012 reports (Ministry of Health Citation2013b). There was a significant decrease in hazardous drinking of those aged 15–17 years between 2006–2007 and 2015–2016 (Ministry of Health Citation2016). Similarly, while people aged 18–24 years have the highest rates of hazardous drinking, the proportion decreased from 49% in 2006–2007 surveys, to 36% in the 2012 survey (Ministry of Health Citation2013b). New Zealand remains slightly under (8.7 litres per capita, 2015 and 8.8 litres per capita, 2017) the international OECD average of recorded alcohol consumption of 9 litres of pure alcohol per capita in 2015 of those 15 years and older, equivalent to 96 bottles of wine (OECD Citation2019). Although New Zealand sits slightly below the OECD average of pure alcohol per capita there is no safe limit for adolescent drinking and therefore warrants further investigation and development of tools to curb adolescent drinking.

Research aims

This study explored attitudes about alcohol use and drinking patterns of New Zealand adolescents in 2015. Questions were asked about the age of first drink, amount and frequency of drinking and how alcohol was obtained.

Materials and methods

Studies have suggested that alcohol harm reduction education is more beneficial when it is provided before adolescents establish a drinking pattern (Perry et al. Citation2002; Stigler et al. Citation2011). Since Kypri et al. (Citation2009) found the self-reported age of first alcoholic drink by New Zealand youth was 14.6 years, 14–15-year-olds (School Year 10 in New Zealand) were chosen as the target age for this study. The University of Otago's Human Ethics Committee granted approval for the study (15/093). Qualitative and quantitative data were collected via questionnaire as part of a larger study (Campbell Citation2016). In that study, students were asked questions about alcohol and drinking patterns both before and after exposure to an alcohol educational resource, which resulted in significant changes in awareness in immediate post testing and follow-up test 3–6 weeks later (P < .001, highly significant) (Campbell Citation2016). Results reported here are from the questionnaire administered before exposure to the educational resource.

Data collection

The questionnaire was embedded within the introduction to an educational resource, with participants completing it before exposure to the resource. It was administered via QualtricsTM with the consent of school principals, parents and participants. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw at any point. Because questions about alcohol use were asked, safety messages and contact numbers for services were displayed throughout the questionnaire and all participants were given a card with contact details for relevant services at the conclusion of the testing.

Questions relating to alcohol use were modelled on those used in the University of Auckland’s Youth2000 Survey Series (Adolescent Health Research Group Citation2008; Campbell Citation2016). The full questionnaire used in this study can be found in Campbell (Citation2016).

Questionnaires were administered at 10 participating schools over a three-week period in August 2015. Data were collected in one class period in classrooms with 14–30 students. The first author gave a five-minute introduction and instructions. Students were reminded that all answers would be kept anonymous and participating schools would not have knowledge of any individual’s answers. Students wore headphones during testing and were encouraged not to speak to each other.

Sampling

A pilot test was conducted and consisted of 98 students enrolled in a first-year health science course at the University of Otago; most (78%) of this pilot cohort were between 18 and 20 years old. There were minor modifications to the questionnaire after pilot testing. For example, in the categorical question that asks if students consider themselves a binge drinker, the possible answer of ‘I’m not sure what a binge drinker is’ was added.

Secondary schools were contacted via email in the Otago, Southland and Hawkes Bay regions of New Zealand, due to availability and funding of the study. Ten consenting schools were selected to represent a range of ethnicities, religions, co-education/single-sex schools and socioeconomic decile ratings. Socioeconomic decile ratings are analysed in this study, rather than geographical location, as not all areas of New Zealand were tested. Decile ratings are generated by the Ministry of Education in New Zealand as an indicator of socioeconomic status (SES). Decile rating is calculated from information provided from the national census and takes homes’ income, jobs, dependants and beneficiaries into consideration (http://www.ero.govt.nz).

Participant demographics

Demographic, religion and ethnicity questions in the survey mirrored those used in the 2013 New Zealand Census. Most students (81%) consider themselves to be of New Zealand European ethnicity. About 26% of the participants in this study self-identified as Māori or Pacific Island ethnicity, 17% as Chinese and just below 1% as Filipino or ‘other’ (any ethnicity where only one student chose that option). Students could identify with more than one ethnicity.

Most of the cohort was aged 14 (64%) or 15 (35%) years. Students identified as male (56%), female (43%) or other (1%). The majority (71%) of the Year 10 cohort identified as having no religion, 22% self-identified as Christian (Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian, Methodist, Ratana, Ringatu), 3% (17 students) as having ‘other’ belief system (Buddhist, Hindu, Jehovah’s Witness, Jewish, Mormon, Muslim or atheist) and 4% of students providing no answer about their religion.

Data analysis

Quantitative data collected were continuous or categorical and analysed using IBM SPSS Version 22. Statistical analysis used to examine relationships between demographic data, habitual drinking patterns, attitudes and preferences included the McNemar Test and Cochran’s Q Test.

Participants were asked to give three words associated with (1) their own personal use of alcohol and (2) why they think people more generally use alcohol. Answers were collated and streamed into root words. Separate word clouds were developed through a Wordle application online (http://www.wordle.net/) for those participants who reported they did drink alcohol and for those who reported they did not.

Results

Drinking patterns and perceptions

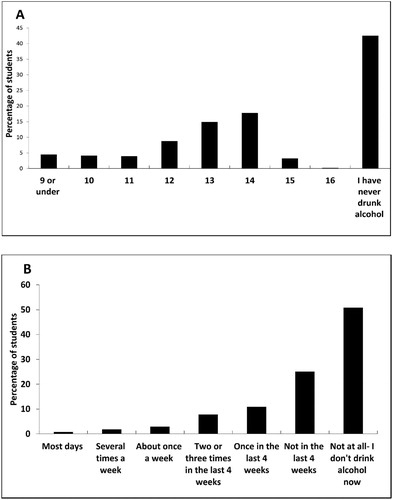

Over half (54%) of the Year 10 students said that they had drunk alcohol (more than a few sips), 43% said they had never drunk alcohol and 4% reported they were unsure. Age of first drink was recalled by 18% as 14 or 15 years, 15% as 13 years and 21% at 12 years or younger (A). The average self-reported age of the students’ first drink (more than a few sips) was 12.6 years. The actual average may be even lower than this, as the lowest optional answer for this question was nine or under (4.5% of respondents chose that option). For the nine years old or under response, the number 9 was used to calculate the average.

Figure 1. Student recall of drinking (N = 579); A, Age at which they first had an alcoholic drink (more than a few sips); B, Frequency of recalled drinking of alcohol in the previous four weeks.

Of the Year 10 participants, 77% reported not drinking at all in the previous four weeks while 23% reported having drunk one or more times in the previous four weeks. Four individuals reported that they drank alcohol most days (B). When asked specifically how many times they consumed more than five standard drinks in one occasion (binge drinking) in the previous four weeks, 11% reported that they had binged once in the last four weeks and 9% had binged two or more times in the last four weeks.

Year 10 students were asked how many standard drinks they would usually consume in one session. A number of respondents (n = 75; 13%) reported they drink five or more standard drinks when they consumed alcohol. Yet when students were asked if they consider themselves binge drinkers, only 1% answered yes, 8% were not sure and 12% answered that they did not know what a binge drinker was. Most participants reported drinking less, with 39% reportedly not drinking at all, 24% one drink in an average session and 24% two to four drinks per session.

In response to being asked why they drink alcohol, the main reasons given by 14 and 15-year-old students were to have fun (28%), enjoy parties (17%) and relax (15%). Participants were asked to supply three words (free choice, with no lists or words provided) that they themselves would use to describe alcohol. Results are presented separately for those students who do not drink (A and C) and those who do (B and D). The size of the word in a word cloud is related to the frequency of use. Those students who do not drink used words like ‘dangerous’, ‘bad’ and ‘addictive’ more frequently (A). The group who drink alcohol used these same three words but were more likely to use the words ‘fun’, ‘drink’ or ‘drunk’, ‘yum’, ‘good’ and ‘social’ (B).

Figure 2. Word cloud representation of words used to describe alcohol (A, B), and words describing why people use alcohol (C, D), separated by Year 10 students who do not drink alcohol (A, C n = 236) and Year 10 students who do drink alcohol (B, D n = 343).

When participants gave three words to describe why other people in general use alcohol, those who do not drink alcohol frequently used words like ‘fun’, ‘party’, ‘peer-pressure’, ‘stress-relief’, ‘relaxation’, ‘depression’ and ‘addicted’ (C). Participants who self-reported they do drink also frequently used ‘fun’, ‘depression’, ‘relaxation’, ‘party’ and ‘stress-relief’ but were more likely to use the words ‘good-time’ and ‘cool’ (D) than participants who do not drink alcohol.

About 14% of the Year 10 cohort who drink are potentially doing so without their parents’ knowledge and sourcing alcohol illegally. Two Year 10 students reported that they buy their own alcohol illegally, 5% of students said that their friend’s parents bought their alcohol for them and 8% of students said that another adult buys alcohol for them.

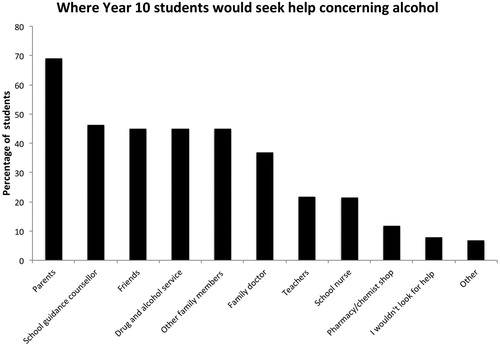

Most students (69%) said they would consider turning to their parents for help concerning alcohol (). Over 40% of the students said they would seek help from a school guidance counsellor, friends, drug and alcohol services or other family members, while 9% of students said that they would not look to any of the options listed for help concerning alcohol.

Socioeconomic status indicators and ethnicity in relation to drinking habits

Data were analysed with SES indicators and self-identified ethnicity as independent variables. Schools were categorised into four different SES groups for analysis (). Schools in the lowest SES group D had a higher percentage of Māori or Pacific Island students (60%) than the other SES groups. There was no difference in the average age of 12.6 years for a first drink between any SES groups. However a lower proportion of students at the highest SES group A schools (32%) self-reported having ever drunk alcohol compared to 51%–64% of students in lower SES schools. Of students in the lowest SES group D schools, 30% reported drinking five or more drinks every time they drink and 6% reported they had binged (five or more standard drinks on any occasion) every week in the last four weeks ().

Table 1. Drinking patterns of participants and frequency of having five or more standard drinks in any one session in the previous four weeks for respondents in different socioeconomic status (SES) groups. Group A was the highest socio-economic decile; D was the lowest. Percentages are proportion of students in the SES group. Note: The minimum age option was ‘nine years or below’ in question about age of first drink, N = 571.

The average age of first drink of Māori students was the same as that of students of other ethnicities. Nearly 61% of Māori within this study reported having drunk alcohol compared to 50% of non-Māori students. Just under 5% of Māori or Pacific Island students reported having binged every week in the last four weeks compared to 0.5% of non-Māori/Pacific Island students. In this study, SES had a larger effect size than ethnicity in correlation with drinking (medium effect for SES, small effect for ethnicity).

Discussion

The initiation of alcohol use reported in this study (age of first drink) was 12.6 years, two years earlier than previously reported (Kypri et al. Citation2009). Age of first drink did not vary with SES indicators or ethnicity. Kypri et al. (Citation2009) surveyed university students with an average age of 20.2 years, which would have been many years after their first drink. In our study, participants were 14 or 15 years old. While it is possible that participants in this study exaggerated their response, it is likely that these results are more accurate because participants may have better recall of the actual age of their first drink given a more recent occurrence. A limitation of any study of this nature is reliance on self-reporting. The reliability of reported age of first use has been questioned (Bailey et al. Citation1992). Nonetheless, self-report methods can offer a reliable and valid approach to measuring alcohol consumption (Del Boca and Darkes Citation2003). While there are reports that adolescent alcohol use in New Zealand is on the decline (Ministry of Health Citation2013a, Citation2015, Citation2016) our data suggest persistent problems of adolescent alcohol misuse.

Almost 70% of participants identified their parents as the primary point for help regarding their alcohol use. This is a critical finding and indicates the need for comprehensive support, investment and advice for parents, as they are a key influencer of drinking behaviour and attitudes (Chung et al. Citation2013). Nearly half of the participants in this study reported that they would access school counsellors and drug and alcohol services for help regarding their alcohol use, supporting the value of those services in assisting adolescents. This is consistent with studies in the United Kingdom (Fox and Butler Citation2009), Zimbabwe (Chireshe Citation2011) and the United States (Anglin et al. Citation1996) which have shown an important role of student counsellors and health centres in schools, as well as drug and alcohol services and the support they provide to adolescents.

The 13% (n = 75) of 14–15-year-olds who self-reported binge drinking in this study is lower than the 19.3% of New Zealanders aged 15 years and older reported to have hazardous drinking patterns (Ministry of Health Citation2016). However, there is no limit considered safe for adolescents to drink. Five standard drinks per occasion are considered hazardous for a person over 18 years of age and the brain is more vulnerable to alcohol-related damage at younger ages (White Citation2013).

Poudel and Gautam (Citation2017) showed that psychosocial problems were significantly associated with the age of onset of substance use. In assessing psychosocial problems among individuals with substance use disorders (n = 221) residing in a drug rehabilitation centre, those who initiated substance use early (17 years or younger) had higher mean scores of psychosocial problems than those who started substance use later (Poudel and Gautam Citation2017). It cannot be determined whether the psychosocial problems encouraged the early onset of substance use or alternatively the early onset of substance use resulted in psychosocial problems in the patients.

The 2018 Health Promotion Agency report on New Zealanders’ alcohol consumption patterns across the lifespan has shown that men who are high-frequency drinkers, consuming high quantities per occasion, initiated earlier alcohol use in life and had a lower socioeconomic status than males who drank more infrequently (Towers et al. Citation2018). Also, the report found that for men the presence of parents who were heavy drinkers was linked to high frequency and high quantity drinking behaviours later in life (Towers et al. Citation2018). The report indicates that, once established, a pattern of drinking (whether hazardous or non-hazardous) is unlikely to be changed and becomes a stable behavioural characteristic throughout life. This illustrates that normalising hazardous drinking patterns is at the point of initiation in adolescence or early adulthood, and is therefore the critical point of intervention to reduce alcohol-related harm (Towers et al. Citation2018).

In 2010 37 countries participated in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study, which was comprised of cross-sectional survey data on 13- and 15-year-olds. This study found that high levels of adult alcohol consumption and limited alcohol control policies are associated with higher alcohol use among adolescents (Bendtsen et al. Citation2014).

A population-based study in the US found that a younger age of first alcohol use was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of heavy alcohol use in the 30 days prior to data being collected (Liang and Chikritzhs Citation2013). King and Chassin (Citation2007) tested whether the age of onset of alcohol and drug use predict alcohol and drug dependence and concluded that early-onset adolescent use of alcohol is a marker of risk for later dependence. Internationally both cross-sectional (McGue et al. Citation2001; Hingson et al. Citation2006) and longitudinal studies (Warner et al. Citation2007; Pitkänen et al. Citation2008) have suggested that the age of initiation of alcohol consumption is one of the strongest predictors for the development of alcohol dependence later in life. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study has followed people born in 1972 and obtained data periodically throughout their lifetime. In one study of this cohort (n = 933), participants were asked questions of alcohol use from age nine. A measure of ease of access to alcohol at age 15 was predictive of both men and women consuming higher typical quantities at ages 18–26 years (Casswell et al. Citation2003). Casswell et al. (Citation2003) found that early onset of drinking before or at the age of 15 years predicted higher frequency of drinking in males aged 18–26 years. Our study involved 14–15-year-olds in 10 secondary schools of diverse SES in three regions of New Zealand. Our results corroborate other reports (Adolescent Health Research Group Citation2008; Kypri et al. Citation2009; White Citation2013) that some young people in New Zealand have already started hazardous drinking at this age. An education resource could benefit young people who are engaging in risky drinking behaviours but may not have accurate knowledge about the effects of alcohol consumption (De Visser and Birch Citation2011; Campbell Citation2016). A systematic review between 2002 and 2012 of health, social policy and specialist review databases were searched for the effectiveness of population-level alcohol interventions on consumption or alcohol-related health or social outcomes and found that there has been mixed evidence for school-based interventions and family- and community-level interventions (Martineau et al. Citation2013).

This study found there were binge drinking misuse patterns within all SES groups, but prevalence was highest in the lowest SES group. Young people in schools with lower socioeconomic indicators were more likely to drink regularly and more heavily.

Parental monitoring and attitudes are strongly associated with the probability of non-drinking (Larm et al. Citation2018) and parental supply of alcohol is associated with risky drinking (Gilligan et al. Citation2012). An Australian study found that drinking behaviours of parents, friends and/or siblings were good predictors of frequent alcohol consumption (Jones and Magee Citation2014). Jones and Magee (Citation2014) also found higher disposable income was a good predictor of frequency of consumption. This is potentially inconsistent with our findings which showed that students in the highest SES schools were more likely to drink less frequently. Our questionnaire assessed links between consumption and school SES but did not ask about individual access to money, which should be included in future studies.

Within the lowest SES schools in this study, 60% of participants self-identified as being of Māori or Pacific Island ethnicity. The findings here are consistent with previous studies that have shown that these youth are more likely to be at risk of dangerous drinking habits. However, it must be considered that this could be due to socio-economic influence, rather than ethnicity/culture driving the risk of alcohol misuse. This should be explored further in future studies, as studies outside of New Zealand have reported ethnicity differences in substance use profiles (Gilligan et al. Citation2012; Chung et al. Citation2013). As a result, culturally tailored interventions for use before hazardous drinking patterns are established could be particularly useful in lower economic status communities with higher proportions of Māori and Pacific Island youth.

Summary

We found the initiation of alcohol use (age of first drink) to be 12.6 years, two years earlier than previously recorded in New Zealand. This is the same for students of all SES indicators or ethnicity. Nonetheless, there were differences in proportions and patterns of alcohol use between students in schools with different SES. Students in the highest SES schools were less likely to drink at all. Students in the lower SES schools were more likely to drink and those who did were more likely to exhibit hazardous patterns of alcohol misuse, with nearly 30% of students in the lowest socioeconomic group reporting drinking five or more drinks every time they drink, an amount defined as binge drinking for an adult (White Citation2013). Thirteen per cent (n = 75) of all 14–15-year-olds in this study self-identified as binge drinkers.

We recommend educational programmes delivered at a young age to help decrease hazardous use of alcohol. Intergenerational education may be more effective than traditional classroom efforts alone, since parental attitudes and behaviours are associated with adolescent use of alcohol (Chung et al. Citation2013) and over two-thirds of the participants in our study indicated a willingness to approach their parents for help related to alcohol.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The full data set is available from the authors.

ORCID

Nancy Longnecker http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2798-6389

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adolescent Health Research Group. 2008. Youth ’07: The health and wellbeing of secondary school students in New Zealand: initial findings. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

- Adolescent Health Research Group. 2012. Youth ’12: national health and wellbeing survey of New Zealand secondary school students: data dictionary. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

- Anglin TM, Naylor KE, Kaplan DW. 1996. Comprehensive school-based health care: high school students’ use of medical, mental health, and substance abuse services. Pediatrics. 97(3):318–330.

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. 2011. The alcohol use disorders identification test guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Bailey S, Flewelling R, Rachal J. 1992. The characterization of inconsistencies in self-reports of alcohol and marijuana use in a longitudinal study of adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 53(6):636–647. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.636

- Bendtsen P, Damsgaard M, Huckle T, Casswell S, Kuntsche E, Arnold P, Ter Bogt T. 2014. Adolescent alcohol use: a reflection of national drinking patterns and policy? Addiction. 109(11):1857–1868. doi: 10.1111/add.12681

- Campbell S. 2016. Your brain on booze: impact of a multimedia adolescent alcohol education resource [master’s thesis]. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago.

- Casswell S, Pledger M, Hooper R. 2003. Socioeconomic status and drinking patterns in young adults. Addiction. 98(5):601–610. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00331.x

- Chireshe R. 2011. School counsellors’ and students’ perceptions of the benefits of school guidance and counselling services in Zimbabwean secondary schools. Journal of Social Sciences. 29(2):101–108. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2011.11892960

- Chung T, Kim K, Hipwell A, Stepp S. 2013. White and black adolescent females differ in profiles and longitudinal patterns of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 27(4):1110–1121. doi: 10.1037/a0031173

- Conover E, Scrimgeour D. 2013. Health consequences of easier access to alcohol: New Zealand evidence. Journal of Health Economics. 32(3):570–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.02.006

- De Visser R, Birch J. 2011. My cup runneth over: young people's lack of knowledge of low-risk drinking guidelines. Drug and Alcohol Review. 31(2):206–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00371.x

- Del Boca F, Darkes J. 2003. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 98:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x

- Fleming T, Lee A, Moselen E, Clark T, Dixon R. 2014. Problem substance use among New Zealand secondary school students: findings from the Youth ’12 national youth health and wellbeing survey. The adolescent health research group. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

- Fox C, Butler I. 2009. Evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based counselling service in the UK. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling. 37(2):95–106. doi: 10.1080/03069880902728598

- Gilligan C, Kypri K, Johnson N, Lynagh M, Love S. 2012. Parental supply of alcohol and adolescent risky drinking. Drug and Alcohol Review. 31(6):754–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00418.x

- Guerri C, Pascual M. 2010. Mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral effects of alcohol consumption during adolescence. Alcohol. 44(1):15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.003

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M. 2006. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 160(7):739. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739

- Jones S, Magee C. 2014. The role of family, friends and peers in Australian adolescent's alcohol consumption. Drug and Alcohol Review. 33(3):304–313. doi: 10.1111/dar.12111

- King K, Chassin L. 2007. A prospective study of the effects of age of initiation of alcohol and drug use on young adult substance dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 68(2):256–265. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.256

- Kypri K, Paschall M, Langley J, Baxter J, Cashell-Smith M, Bourdeau B. 2009. Drinking and alcohol-related harm among New Zealand university students: findings from a national web-based survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 33(2):307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00834.x

- Larm P, Livingston M, Svensson J, Leifman H, Raninen J. 2018. The increased trend of non-drinking in adolescence: the role of parental monitoring and attitudes toward offspring drinking. Drug and Alcohol Review. 37:S34–S41. doi: 10.1111/dar.12682

- Liang W, Chikritzhs T. 2013. Age at first use of alcohol and risk of heavy alcohol use: a population-based study. BioMed Research International. 2013:1–5.

- Maldonado-Devincci A, Badanich K, Kirstei C. 2010. Alcohol during adolescence selectively alters immediate and long-term behavior and neurochemistry. Alcohol. 44(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.09.035

- Martineau F, Tyner E, Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Lock K. 2013. Population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm: an overview of systematic reviews. Preventive Medicine. 57(4):278–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.019

- McGue M, Iacono W, Legrand L, Malone S, Elkins I. 2001. Origins and consequences of age at first drink. I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25(8):1156–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02330.x

- Medina KL, McQueeny T, Nagel BJ, Hanson KL, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. 2008. Prefrontal cortex volumes in adolescents with alcohol use disorders: unique gender effects. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 32(3):386–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00602.x

- Ministerial Committee on Drug Policy. 2007. National drug policy 2007–2012. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/national-drug-policy-2007-2012.

- Ministry of Health. 2009. Drug use in New Zealand: key results of the 2007/08 New Zealand alcohol and drug use survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/drug-use-in-nz-v2-jan2010.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. 2013a. A new national drug policy for New Zealand: discussion document. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/new-national-drug-policy-new-zealand-discussion-document.

- Ministry of Health. 2013b. Hazardous drinking in 2011/12: findings from the New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. http://www.moh.govt.nz/NoteBook/nbbooks.nsf/0/81BF301BDCF63B94CC257B6C006ED8EC/$file/12-findings-from-the-new-zealand-health-survey.pdf.

- Ministry of Health. 2015. Alcohol use 2012/13: New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/alcohol-use-2012-13-new-zealand-health-survey.

- Ministry of Health. 2016. Annual update of key results 2015/16: New Zealand health survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/annual-update-key-results-2015-16-nzhs-dec16-v2.pdf.

- Nixon K, McClain J. 2010. Adolescence as a critical window for developing an alcohol use disorder: current findings in neuroscience. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 23(3):227–232. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833864fe

- OECD. 2019. Alcohol consumption (indicator). [accessed 22 April 2019]. https://doi.org/10.1787/e6895909-en.

- Perry CL, Williams CL, Komro KA, Veblen-Mortenson S, Stigler MH, Munson KA, Farbakhsh K, Jones RM, Forster JL. 2002. Project Northland: long-term outcomes of community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Education Research. 17(1):117–132. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.117

- Pitkänen T, Kokko K, Lyyra A, Pulkkinen L. 2008. A developmental approach to alcohol drinking behaviour in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8 to age 42. Addiction. 103(s1):48–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02176.x

- Poudel A, Gautam S. 2017. Age of onset of substance use and psychosocial problems among individuals with substance use disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 17(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1191-0

- Roaten G, Roaten D. 2012. Adolescent brain development: current research and the impact on secondary school counseling programs. Journal of School Counseling. 10(18):n18.

- Squeglia L, Jacobus J, Tapert S. 2009. The influence of substance use on adolescent brain development. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience. 40(1):31–38. doi: 10.1177/155005940904000110

- Stigler M, Neusel E, Perry C. 2011. School-based programs to prevent and reduce alcohol use among youth. Alcohol Research and Health. 34(2):157–162.

- Towers A, Sheridan J, Newcombe D, Szabó Á. 2018. New Zealanders’ alcohol consumption patterns across the lifespan. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency.

- Warner L, White H, Johnson V. 2007. Alcohol initiation experiences and family history of alcoholism as predictors of problem-drinking trajectories. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 68(1):56–65. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.56

- White J. 2013. Use of alcohol among year 10 students. [In Fact]. Wellington: Health Promotion Agency Research and Evaluation Unit. [accessed July 2018]. https://www.hpa.org.nz/research-library/research-publications/use-of-alcohol-among-year-10-students-in-fact.