ABSTRACT

In industrialised countries, a large number of older adults with increasingly complex end of life care needs will die while in long-term care. It is essential that processes be in place to facilitate quality end of life care in these settings. In collaboration with two local hospices over the course of one year, we developed a new model of palliative care within long-term care – Supportive Hospice Aged Residential Exchange (SHARE). SHARE fostered knowledge exchange between hospice nurses and long-term care staff to improve palliative care delivery within 20 long-term care facilities (LTCF’s). An in-depth qualitative investigation of the views of 59 healthcare professionals and 12 bereaved family members of residents, regarding SHARE implementation, was undertaken through semi-structured interviews. Transcripts were analysed thematically and mapped to the theoretical domains framework (TDF) in order to identify facilitators and challenges to SHARE implementation. Domains facilitating SHARE implementation provided benefits in terms of ‘knowledge’, ‘skills development’, and supported the mentoring and role modelling provided by the hospice. Challenges highlighted the resource constraints of the long-term care context. The use of the TDF has enabled the identification of essential components such as skills development, which facilitate the implementation of SHARE in LTCF’s.

Introduction

Increasing life expectancy in industrialised societies has led to a growing concern with the health of older people (World Health Organisation Citation2015b). The realities of older people’s health translate into an increased chance of death due to cardiovascular diseases, stroke, neurological conditions and some cancers (Hall et al. Citation2010). The prolonged death trajectory associated with these conditions, as well as the complex comorbidities experienced, translate into rising palliative care need (Morin et al. Citation2016). Palliative care enhances the quality of life for those facing life-limiting illness (World Health Organisation Citation2015a). Internationally, the number of deaths in long-term care facilities (LTCF) is also projected to increase by 108% by 2040 (Bone et al. Citation2018). In New Zealand, the proportion of those over 65 using LTCF for end of life care is over 47% (Broad et al. Citation2015). LTCF includes rest homes, hospitals, dementia care and psychogeriatric care (New Zealand Government Citation2001).

Yet, despite this growing need, LTCF staff (registered nurses [RN’s] and healthcare assistants [HCA’s]) are often unprepared to care for residents with palliative care needs. Marshall et al. (Citation2011) found gaps in knowledge in areas such as symptom control and care for residents with dementia. Internationally, staff education is seen as the most effective way of optimising palliative care provision in LTCF settings (Ronaldson et al. Citation2008; Latta and Ross Citation2010). Yet, Frey et al. (Citation2015a) found that burnout decreased the likelihood of engaging in further palliative care education. In LTCF a lack of consideration of organisational factors also creates barriers to sustainable change (Frey et al. Citation2015b).

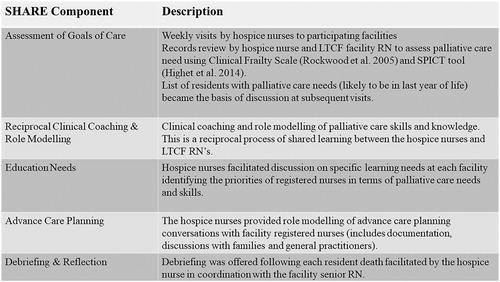

Staff education and greater interaction with hospice are linked to improved end of life care in LTCF, including symptom assessment and management (Miller et al. Citation2002). Developed from prior research (Frey et al. Citation2015b, Citation2016), the Supportive Hospice and Aged Residential Exchange (SHARE) model (Frey, Boyd et al. Citation2017) is designed to (1) improve integration between specialist palliative care services offered by hospice and LTCF’s, (2) aid the development of staff in-house expertise in palliative care delivery, (3) provide an ongoing feedback mechanism for facilities to identify areas of service delivery in need of improvement, (4) increase hospice nurses’ (palliative care nurse specialists) gerontology/frailty care knowledge and expertise ( SHARE model). SHARE was implemented for 1 year in 20 LTCF’s across two district health boards.

There is an established literature on the use of theory to provide a better understanding and explanation of how and why the implementation of interventions succeed or fail (Nilsen Citation2015). The theoretical domains framework (TDF) is composed of 14 domains and 84 component constructs (Cane et al. Citation2012; Phillips et al. Citation2015). Drawing on behaviour change theories, the TDF may prove useful as an overarching framework to guide the coding of qualitative data in relation to behaviour change (Duncan et al. Citation2012; Francis et al. Citation2012). Although often utilised in intervention development, TDF has also been used to guide a retrospective process evaluation (Little et al. Citation2015).

With increasing numbers of residents in LTCFs who could benefit from a palliative approach to care, an in-depth qualitative investigation of the views of all key healthcare professionals involved in the implementation of SHARE as well as family members of residents is needed. The aim of this study is to conduct, an in-depth qualitative investigation of the views of all key healthcare professionals involved in the implementation of SHARE as well as family members of residents. Following this aim, our objectives were to explore which theoretical domains facilitated as well as presented challenges to SHARE implementation.

Materials and methods

Sample

Participants represented a convenience sample of both health professionals and bereaved family members associated with the 20 LTCF’s implementing SHARE. In order to ensure staff, resident and family confidentiality, the invitation for contact by a research assistant (SF) was via the facility managers. The manager provided assurance that the research was independent of the facility and that their decision to participate or not would not affect their relationship with the organisation. Potential participants were informed of the ongoing study, and requested to provide permission for contact from SF (interviewer).

Staff Interviews. Semi-structured interviews (approximately one hour in length) were conducted with staff, GP’s and hospice nurses associated with 20 LTCF’s. The topic guide for the healthcare professional interviews, developed from a review of the literature, addressed any previous education in palliative or end of life care, palliative care experience, as well as benefits and areas of improvement for SHARE. Interviews were conducted between November 2018 and February 2019 at the facility or practice (GP’s).

Bereaved Family Interviews. Interviews were also conducted (Feb–March 2019) with a sample of 12 bereaved family members whose relative died within the 12-month implementation period for SHARE.

The interview guide for bereaved family members explored psychosocial effects including staff communication skills, and perceptions of their relatives’ end of life experience and was developed drawing on questions from the pilot study for SHARE (Frey, Foster et al. Citation2017). The bereaved family interviews (approximately one hour in length) conducted either by phone or face to face. SF a trained social worker has extensive experience in conducting interviews on sensitive topics. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission and transcribed verbatim by a transcriptionist who has signed a confidentiality agreement. SF kept reflective field notes for both the bereaved family and staff interviews to provide an audit trail (Koch Citation1994).

Analysis

Transcripts were imported and analysed using QSR NVIVO (12). Drawing on Schulz’s theory of social phenomenology (Schutz Citation1967), analysis proceeded using both inductive and deductive thematic analysis to interpret the raw data (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006). RF and DB initially coded transcripts together with a sub-sample of transcripts trialled for the TDF coding domains to ensure consistency between coders and a preliminary coding scheme was constructed. The goal was to maintain an accurate representation of participant views and beliefs. Health professional and bereaved family interviews were then analysed separately by RF and DB based on the initial coding as well as differences in the bereaved family and health professional interview guides. Any disagreements following coding were resolved by discussion. Preliminary codes were then fitted within the domains established by the TDF through discussion between RF and DB. Reflexivity in the analysis phase was achieved through researcher teamwork and through rigorous reflexive notes.

Results

Staff. Fiftynine interviews were conducted with two facility managers, 31 RN’s, and 18 HCA’s from 20 LTCF, as well as five general practitioners (GP’s) and the three hospice nurses. The interviewees were associated with 7 large (70 or more beds), 13 small (< 70 beds) facilities. Sixteen facilities were for profit, and four were not for profit LTCF’s. The selected facilities reflected the balance of facilities based on the size and ownership model within New Zealand (Lazonby Citation2007).

The majority of health professionals were female (85%), were most often between the ages of 30–39 (28.8%) and most frequently had worked in LTCF’s for five years or less (39%) ().

Table 1. Staff interview participant and facility characteristics.

Bereaved families. Twelve bereaved family member interviews were also conducted one month after SHARE. Participants were most often female (75%), half were between the ages of 70 and 79 and the majority self-identified as New Zealand European (84%). Half of the bereaved family members reported that their relative had a diagnosis of dementia (50%) ().

Table 2. Bereaved family characteristics.

Theoretical domains framework

Domains were divided into two groups: Domains supporting implementation and domains presenting challenges to SHARE (). Research has demonstrated the importance of assessing both positive and negative aspects of health programmes (Glasgow et al. Citation1999). Themes (in bold text) derived from the transcripts were then linked to the domain under which they were most related. Role and respondent number identify participant quotes. Domains not identified from the transcripts are omitted (optimism, beliefs about consequences, memory and behavioural regulation).

Table 3. Summary of domains and related themes that facilitate and challenge SHARE implementation.

Facilitators - skills and skills development

Clinical coaching and role modelling of palliative care skills and knowledge is a key component of SHARE. Skills development was described in relation to LTCF ‘staff interactions with the hospice nurses’. One RN spoke about the benefits of interactions with hospice nurses for medication management.

They [hospice nurses] will come and talk to us … how the residents are … And we update them if they are needing a lot of pain relief … they will then sit down and see if they need to review their medication or if the pain relief is not enough or if we need to put the pump. RN (267)

Results of the ‘mentoring’, which occurred, were evidenced in the quotes, particularly on the part of the RN’s. The impression is that for LTCF RN’s the introduction of hospice nurses has been very helpful particularly around medication needs, learning when someone is palliative and learning how to talk with families:

All the Nurses are aware now that, like with the prescription. Before … Nurses or those who are younger, just new to the organisation … They won’t notice that there’s no medications there for the end of life … now everybody’s looking and saying, oh why was he not chartered this? I just ring the Doctor and remind him and all that. RN (261)

Facilitators – knowledge

Knowledge within the context of this study was often defined in terms of ‘education sessions’ attended during SHARE. These were most often one-hour sessions requested as part of SHARE on topics related to palliative care. RN (263) reported, ‘On the Last days [of Life] we have this like in-service programme, like lecturer, just learned it [palliative care] more clearly … when we had the education maybe I can do better.’ This was a marked change for some overseas-trained RN’s. ‘In my previous Practice in the Philippines, we don’t have that palliative care there.’

GP’s had mixed views of the level of skill of LTCF RN’s participating in SHARE. One GP (322) stated, ‘I believe they’ve changed for the better, just more knowledge.’ While another GP had a more pessimistic outlook: ‘I don’t know whether they get enough regular in-service training about the palliative side of things’. GP (326)

Knowledge was also demonstrated by an expanded view of the ‘definition of palliative care’ because of SHARE. While still equating palliative care with end of life care, HCA’s perceived that the care needed related not only to the care of the resident but also to the family as well. ‘Well it’s, it’s all about the end of life … the way how we look after them and … their family as well.’ HCA (253). Facility manager (272) provided an extended timeframe in which palliative care is to be provided: ‘In the last, you know, like a month or so of their life where if they’re really sick at that stage that you start into the palliative care.’

Facilitators – beliefs about capabilities

Beliefs about capabilities were represented along a number of dimensions. Capabilities in specific areas of palliative care delivery were highlighted, most notably in terms of ‘communication’ during SHARE. RN (276) stated, ‘I’m confident with talking with the family.’ There was a lack of confidence in abilities around communication for some RN’s however, particularly for those trained overseas.

I’m not really like … fluent in English … I think one of the problems that I have in dealing with the families. RN (290)

There was also evidence of ‘staff confidence’ enhanced by SHARE as highlighted by Manager (310) ‘I felt the RN … feel more confident dealing with palliative care … they’ve got somebody [hospice nurse] to help them, to give them a hand.’ The ability to recognise the need for assistance when a resident’s condition changed was also reported by hospice nurse (304):’ A few facilities they were quite capable to send referral to my committed Team if they feel like they need symptom management support.’

During SHARE hospice nurse self-reported confidence increased in dealing with end of life for frail older people, particularly in those with a diagnosis of dementia. According to hospice nurse (304), ‘I would definitely learn a lot how elderly dying with frailty or dementia.’ She (304) continued:

my background of roughly ten years of hospice and … I have learned a lot compared to my colleagues [other hospice nurses] now. Because I have more time and space to really observe what my colleagues in residential aged care are doing.‘

They’ve spent maybe the first 20 years of that time working in hospitals and then just change to GP. They may not have that perspective, the long term for palliative care patients.

Sometimes self-confidence decreased the perceived need for collaboration between hospice nurses and certain GP’s: ‘I very rarely bring Hospice in because I’ve done Palliative Care for a long, long time.’(GP 318) Hospice nurse (307) reported that during SHARE: It’s been quite hard to collegially get them [GP’s] to discuss processes, improving capability in their residential aged care.’

In contrast ‘family confidence’ in the LTCF staff’s skills and capabilities post SHARE was fairly high ‘the nurses were wonderful … Even the carers were, were quite good’ Interview (342). All said that their relatives were treated with dignity and respect. In fact, many reported how close their relatives became to the carers and enjoyed the relationship they had developed. There were, however, still some gaps in detail of care at times, as one family member recalled:

She’d get angina … they did get onto it pretty quick. But one day she’s puffing away there with a couple of puffer things … I check them … I said, Mum, these aren’t doing anything. I said, they’re empty. Family (339)

Facilitators – reinforcement

Reinforcement provided through SHARE was exemplified by three themes, the first of which was identified with ‘presence’ in the moment. The quote on communication with family demonstrates the benefits of role modelling in terms of supporting new learning:

I saw her [hospice nurse], the way, how she was explaining things to him [relative] as well … providing that time was very helpful and she’s very knowledgeable as well. RN (252)

The hospice nurse presence not only supported learning but also reinforced ‘emotional well-being’. Facility manager (272) stated ‘She’s very good [hospice nurse] with their [staff] psychological beings.’ Reinforcement also came in the form of ‘debriefing’ following resident deaths. One HCA (258) stated, ‘She’s also here if we’re really attached to the resident who’s like dying, so if you’re emotionally attached.’ RN (273) reflected: ‘She [hospice nurse] provided a debriefing session with us.’ Families sometimes felt disconnected from staff post-bereavement. Family (342) stated, ‘They just gave me a bit of sympathy, the usual sorry for your loss and all that sort of stuff. But I suppose they’ve got work to do afterward.’

Facilitators - intentions/goals

Intentions took various forms. Among RN’s, there was a spoken goal to ‘maintain the gains’ provided by SHARE.

I hope that the researchers … would take a look into that consideration or into that aspect on how are they going to encourage the staff or the Nursing staff to keep doing this. RN (291)

Other themes included the ‘intrinsic job motivation’ of the individual. An HCA (268) commented on her motivation: ‘To care for them and to try to make them happy, that makes me happy.’ A GP (318) reflected on his motivation for working with LTCF residents: ‘I do it because it spins my wheels it turns my brain over. Secondly, I do it because I think I can make a difference to some of those people.’

The final theme related to goals concerning desires and goals with respect to ‘further palliative care education’. Hospice nurse (304) in speaking of the manager’s goals stated, ‘They really want that education to be given to support the team to grow.’ RN (317) added, ‘curious people learn and you will learn and it’s gonna be a good thing for you, up-skilling yourself.’

Challenges – role

The domain of role brought forth numerous reports from the staff concerning the heavy ‘workloads’ required of both RNs and HCAs. These workloads along with high staff turnovers represented challenges to the continued implementation of SHARE. RN (261) reported, ‘I’m the ones that I’m doing the medications and all directly, I’m responsible for 30 residents.’ HCA (268) described her role, as ‘I am the primary caregiver for five residents.’ HCA (253) added ‘Sometimes five, sometimes if we’re short it’s six, six and a half, and seven [residents].’ With the noticeable fewer staff, families identified less attention to detail because of the more rushed care:

They always would be like, we’re so understaffed … in situations like that, you would wait you know, to the point where like just sit there Mum and don’t move … I’d go off looking for somebody. Family (343)

Position within an organisation based on professional role also presented ‘limitations’. RN’s, for example, were limited in what information they could communicate to families. RN (263) explained, ‘We nurses we cannot say, oh the patient is dying, we just can say, oh the patient seems to be like that, dying.’ Rank within the LTCF could also affect needed communication. As RN (290) observed, ‘If the Senior Nurse is the one asking him [the doctor] he replies immediately. But you know for other RN’s he [the doctor] doesn’t probably.’ Duties associated with a role could also create obstacles to learning for staff. As one hospice nurse (304) reflected, ‘It’s only the Manager doing [family conversations], so the Nurses are not able to be trained or grow in that perspective.’

Challenges – environmental context and resources

‘Resource constraints’ found within the LTCF sector also challenged the implementation of SHARE. These constraints were most keenly felt in small privately-owned facilities.

Nurses become a task person. So no matter how good the nurses want to be, at the end of the day you don’t have the resource, you don’t have your colleague to discuss … so in the … small size nursing home I feel that the nurses are limited with the growth. hospice nurse (304)

I accept having worked in hospitals for a very long time that hospital are staffed in a way that is just not feasible for most rest homes … it’s a significant cost.

When she [hospice nurse] come(s) in and she checks on that residents and then we got a chance to talk over the care … it’s another way to reflect me, it can make me to reflect okay, what I can do better. RN (269)

Challenges – social influence

Increasing cultural diversity on the part of both the residents and the staff has led to increased ‘cultural challenges’ for LTCF staff. Cultural challenges created barriers to the ability of the LTCF RN’s, managers and hospice nurses to conduct conversations surrounding resident and family wishes for future care – creating an additional barrier to SHARE role modelling of care planning communication. A manager reflected on cultural challenges with Chinese residents and their families:

Culturally sometimes, there is a difference … they don’t like to tell you much about the end of life because they think that’s … looking for trouble … Some residents won’t even cut their little fingernails. Because if you cut that nail means you’re going to kill them … Chinese people are like that. Manager (272)

A Māori family member recalled how staff were supportive of their spiritual and cultural needs post-bereavement … although some aspects were overlooked:

They’ve just started this new idea of putting a photo up and having like a little prayer table if you like or a book there for people to write in. Which I thought was wonderful. There was only one thing … , which on reflection I should have thought to get someone older to go in. You know, we do a, a cleansing ritual.Footnote1 Family (331)

‘Organisational culture’ could also present challenges to the implementation of SHARE. A new Manager commented on the need for a culture change among the LTCF staff:

When we first came, it was what I saw was lacking. Was that personal touch … we’ve, really campaigned quite hard for that. Manager (272)

‘Family influence’ would sometimes provide challenges to the provision of care. Comments by RN (267) reflected this sentiment, ‘To be with the family sometimes it gives us, the family gives us too much pressure … It’s good for them to have their family but their family expectations; they were up, up there.’ Family member (329) confessed, ‘I was pretty fussy on the care that Mum got’ GP (322) reiterated this point in relation to difficult conversations ‘often families don’t want to think that you know, that you’re giving up, you know’. The hospice nurses assistance however, was seen as key in dealing with family concerns:

They [hospice nurses] can explain more about how people are going … they have more experience there. So for the family support I think it’s a good idea to, Hospice to be involved. RN (252)

For family members, the care was perceived as good overall although the impact of staff shortages on the organisational culture of some facilities was also felt:

I couldn’t have faulted anybody. The attentive and the respect was ten out of ten … as time went on … significant changes in staff … it was more just, well I’m here to do my job and nothing more. Not disrespectfully … I guess what I’m trying to say is there was definitely a culture shift. Family (343)

SHARE as a positive social influence was also represented. This was illustrated in the development of care plans for residents’ future needs.

Once I receive it [care plan] I always read it and then where it says family’s wishes and so it just gives us a little bit more opportunity to find out what their goal is and what their perspective is. RN (305)

Challenges – emotion

Emotions both positive and negative reflected the influence of SHARE as well as the psychological and social ‘stressors’ associated with the context of LTCF’s. In relation to SHARE’s impact a manager (300) stated, ‘We have less stressed families worrying about things not being done because we’re more proactive not reactive.’

Love and affection were evident in the staff comments, and residents were often described as ‘like family’ HCA (279). However, with connection came feelings of grief and loss after a beloved resident’s death. One RN (287) reflected, ‘It’s hard for me to facing death still but I feel sad … I’ll really miss her.’ However, statements of ‘relief’, drawn upon as a tool for meaning-making, followed this grief and sadness: ‘I’m a bit happy that you know … for me because [resident] is free in pain, rest in peace.’ HCA (256)

Family members often expressed similar emotions concerning the experience of their relatives’ deaths.

It was just so beautiful, she just started off into this, this beautiful Waiata [song] and I sang the little words that I knew that I could sing and within about, oh two sentences Mum just let go … it was, it was just so peaceful. Family (343)

Where hospice nurse mentoring was absent, disconnections in ‘relationships with families’ led to disconnections in communication concerning a relative’s condition, ‘They [RNs] never told me a thing that she was -going downhill. That her body was shutting. If I’d known that I would have prepared myself a bit better.’ Family (342)

In contrast, during SHARE many of the families also reported how close their relatives became to the carers and enjoyed the relationship they had developed, ‘So I’m grateful, that was great … Totally respectful … every single staff member that had anything to do with her came and said goodbye to her.’ Family (341)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first use of the TDF to evaluate the outcomes of a palliative care intervention in long-term care. Transcript analysis revealed themes related to a range of domains supporting SHARE implementation. In the first instance, staff found value in hospice nurse visits in terms of knowledge, skills as well as reinforcement for those skills. For many of the RN’s, the visit from the hospice nurse allowed them to build a key relationship and encouraged them to share gaps in their knowledge as well as to ask for support in working with families. The ongoing presence of the hospice nurses and the mentoring provided also supported the building of RN’s own beliefs in their capabilities. According to self-efficacy theory, self-efficacy beliefs result from the process of internalising experiences (Bandura Citation1977). Consistent with previous research (Eby et al. Citation2008) findings from this study also indicated that mentoring from the hospice nurses resulted in greater perceived workplace motivation on the part of the nurses. Drawing on cognitive evaluation theory, the intrinsic motivation of staff members (RN’s, HCA’s) for their work and for further education may be enhanced by the supportive mentorship provided by the hospice nurses (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). Reflecting the reciprocal nature of the knowledge exchange in SHARE (Frey, Boyd et al. Citation2017) hospice nurses reported improved confidence in their understanding of geriatric care. Learning in SHARE moved beyond mentoring to reciprocal peer learning (Boud Citation2001). Reciprocal peer learning can increase self-confidence and self-esteem through the sharing of other’s knowledge and experience (Boud Citation2001).

A number of domains posed challenges to the implementation of SHARE. Key themes reflected under the domains of role and environmental context included evidence of the detrimental effects of resource constraints and increasing staff turnovers. These factors not only influence palliative care education and delivery but also resident, family and staff well-being (Frey et al. Citation2015a; Costello et al. Citation2018; Plaku-Alakbarova et al. Citation2018). The creation of genuine connections on the part of the hospice nurses, even in brief encounters, can build social capital and opportunities for teamwork to develop (Ragins Citation2007). In addition, a palliative care orientation package for new residential care staff, which can be used as a supportive tool alongside the mentoring, coaching and reciprocal learning, is needed.

Social influence was in part illustrated by the difficulties in addressing the needs of culturally diverse residents and their families. Given the increased cultural diversity of the elderly population in industrialised societies (Walsh and Näre Citation2016), and consequently in LTCF (Badger et al. Citation2012; McLeod Citation2013), there is a need for increased sensitivity of culturally diverse residents. RN’s also described family influence as a tension between resident/family autonomy and their own clinical judgment. Through SHARE, role modelling of palliative care conversations with residents and families from diverse cultural backgrounds may mitigate issues with miscommunication. As recommended by Candib (Citation2002) these conversations must constitute a ‘collaborative construction’ for cultures that privilege family and community rather than autonomous decision-making (p. 213). Communication should include identification and respect for cultural preferences regarding disclosure, advance care planning and decisional processes (Searight and Gafford Citation2005). Language barriers on the part of overseas-trained RN’s also created cultural challenges to communication with families. However, as evidenced in the results, mentoring by the hospice nurses improved both communication and confidence on the part of LTCF RN’s in dealing with families. Clinical supervision accompanied by reflection on practice can support the practice of overseas-trained RN’s (Viken et al. Citation2018). Results also suggest the expansion of SHARE to include more interaction between the hospice nurse, LTCF’s and GP’s. Banerjee et al. (Citation2018) concluded that a strong engaged relationship between GP’s and LTCF’s improved both GP satisfaction and delivery of quality medical care. The style of management in the LTCF’s played a large part in the success – where the leadership was supportive, managers used the project to create an organisational culture that facilitated staff upskilling. Many change initiatives in LTCF’s begin with strong leadership by managers (Silvestre et al. Citation2015). In contrast, where management privileged hierarchical position educational opportunities could be obstructed. Positive workplace culture has been found to facilitate RN learning and professional development (Davis et al. Citation2016).

The close connection between staff (particularly HCA’s) and residents was evident in the emotions domain in the transcripts. However, this connection could lead to feelings of grief and distress at the loss of a ‘family member’. Debriefing was offered for deaths within the facility, facilitated by the hospice nurse in partnership with a senior LTCF RN. Evidence indicates that debriefing provides an opportunity for staff to reflect on the care provided whilst acknowledging the emotional impact of caring for people at the end of life (Marcella and Kelley Citation2015). Although SHARE provided debriefing for RN’s and HCA’s following deaths, evidence also indicates a need for follow-up with families post-bereavement, including access to counselling services (Aoun et al. Citation2017).

Limitations

In the first instance, there is the potential that participants who agreed to take part in an interview would hold views that were more supportive of SHARE than were non-participants. However, participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. Participants were encouraged to elaborate through additional probing questions, giving them the opportunity to ‘tell their story’. Our previous experience of conducting potentially sensitive research has demonstrated that many bereaved family will share their experiences (both positive and negative), particularly when these can be used to further knowledge and have the potential to improve practice.

While all participants worked or were associated with 20 LTCF’s in one urban area, the diversity of experience from the staff, GP’s and bereaved family members, aids in the identification of any bias and increases the likelihood that the results are an accurate representation of the domains underlying SHARE implementation. Finally, descriptions of the staff members, the bereaved family members and the quotes used may further assist the reader in assessing the transferability of the findings (Tong et al. Citation2007).

Conclusion

The use of the TDF has enabled the identification of essential components such as skills development, reinforcement and goals, which facilitate the implementation of the palliative care educational intervention (SHARE) in LTCF’s. Results also highlight the challenges inherent to such integration activities within the context of the limited resources and high staff turnover common within the sector. Future evaluation studies should incorporate the TDF as a mechanism to obtain a comprehensive understanding from participants’ perspectives of the facilitators and barriers to educational interventions in LTCF’s.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the hospices, hospice nurses, long-term care facilities and their staff, physicians and bereaved family members who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in a de-identified form from the corresponding author, [RF], upon reasonable request.

ORCID

Rosemary Frey http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8758-5675

Deborah Balmer http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8296-5022

Michal Boyd http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8895-1251

Jackie Robinson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9678-2005

Merryn Gott http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4399-962X

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Māori culture, a cleansing ritual usually involving water is performed to ensure the spirit of the deceased safely leaves the space while also making that space safe for others. (Moeke-Maxwell et al. Citation2019, p. 295–316.)

References

- Aoun S, Rumbold B, Howting D, Bolleter A, Breen L. 2017. Bereavement support for family caregivers: the gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS ONE. 12(10):e0184750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184750

- Badger F, Clarke L, Pumphrey R, Clifford C. 2012. A survey of issues of ethnicity and culture in nursing homes in an English region: nurse managers’ perspectives. J Clin Nurs. 21(11–12):1726–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03880.x

- Bandura A. 1977. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Banerjee A, James R, McGregor M, Lexchin J. 2018. Nursing home physicians discuss caring for elderly residents: an exploratory study. Can J Aging. 37(2):133–144. doi: 10.1017/S0714980818000089

- Bone A, Gomes B, Etkind S, Verne J, Murtagh F, Evans C, Higginson I. 2018. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Pall Med. 32(2):329–336. doi: 10.1177/0269216317734435

- Boud D. 2001. Peer learning and assessment. In: Boud David, Cohen Ruth, Sampson Jane, editors. Peer learning in higher education London. London: Kogan Page; p. 67–84.

- Broad JB, Ashton T, Gott M, McLeod H, Davis PB, Connolly MJ. 2015. Likelihood of residential aged care use in later life: a simple approach to estimation with international comparison. Aust NZ J Public Health. 39(4):374–379. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12374

- Candib L. 2002. Truth-telling and advance planning at the end of life: problems with autonomy in a multicultural world. Fam Syst Health. 20(3):213–228. doi: 10.1037/h0089471

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. 2012. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 7(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Costello H, Walsh S, Cooper C, Livingston G. 2018. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 35(1):1–14.

- Davis K, White S, Stephenson M. 2016. The influence of workplace culture on nurses’ learning experiences: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 14(6):274–346. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-002219

- Duncan EM, Francis JJ, Johnston M, Davey P, Maxwell S, McKay GA, McLay J, Ross S, Ryan C, Webb DJ, Bond C. 2012. Learning curves, taking instructions, and patient safety: using a theoretical domains framework in an interview study to investigate prescribing errors among trainee doctors. Implement Sci. 7(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-86

- Eby L, Allen T, Evans S, Ng T, DuBois D. 2008. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J Vocat Beh. 72(2):254–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.005

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. 2006. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 5(1):80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

- Francis JJ, O’Connor D, Curran J. 2012. Theories of behaviour change synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 7(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-35

- Frey R, Boyd M, Foster S, Robinson J, Gott M. 2015a. Burnout matters. The impact on residential aged care staffs’ willingness to undertake formal palliative care training. Prog Palliat Care. 23(2):68–74. doi: 10.1179/1743291X14Y.0000000096

- Frey R, Boyd M, Foster S, Robinson J, Gott M. 2015b. What’s the diagnosis? organisational culture and palliative care delivery in residential aged care in New Zealand. Health Soc Care Community. 24(4):450–462. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12220

- Frey R, Boyd M, Foster S, Robinson J, Gott M. 2016. Necessary but not yet sufficient: a survey of aged residential care staff perceptions of palliative care communication, education and delivery. BMJ Support Palliat Care. [epub]:bmjspcare-2015-000943.

- Frey R, Boyd M, Robinson J, Foster S, Gott M. 2017. The supportive hospice and aged residential exchange (SHARE) programme in New Zealand. Nurse Educ Pract. 25:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.05.004

- Frey R, Foster S, Boyd M, Robinson J, Gott M. 2017. Family experiences of the transition to palliative care in aged residential care (ARC): a qualitative study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 23(5):238–247. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2017.23.5.238

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. 1999. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322

- Hall S, Petkova H, Tsouros A, Costantini M, Higginson IJ. 2010. Palliative care for older people: best practice. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation.

- Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, Boyd K. 2014. Development and evaluation of the supportive and palliative care Indicators tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 4(3):285–290. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000488

- Koch T. 1994. Establishing rigour in qualitative research: the decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 19:976–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01177.x

- Latta LE, Ross J. 2010. Exploring the impact of palliative care education for care assistants employed in residential aged care facilities in Otago. New Zealand. Sites. 7(2):30–52.

- Lazonby A. 2007. The changing face of the aged care sector in New Zealand. Auckland: Retirement Policy and Research Centre.

- Little EA, Presseau J, Eccles MP. 2015. Understanding effects in reviews of implementation interventions using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 10(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0280-7

- Marcella J, Kelley ML. 2015. “Death is part of the job” in long-term care homes. SAGE Open. 5(1):2158244015573912 doi: 10.1177/2158244015573912

- Marshall B, Clark J, Sheward K, Allan S. 2011. Staff perceptions of End-of-life care in aged residential care: a New Zealand perspective. J Palliat Med. 14(6):688–695. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0471

- McLeod H. 2013. Future demographic issues. Wellington: Palliative Care Council.

- Miller S, Mor V, Wu N, Gozalo P, Lapane K. 2002. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 50(3):507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x

- Moeke-Maxwell T, Mason K, Toohey F, Wharemate R, Gott M. 2019. He taonga tuku iho: indigenous end of life and death care customs of New Zealand Māori. Death Across Cultures. Springer. 9:295–316. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-18826-9_18

- Morin L, Aubry R, Frova L, MacLeod R, Wilson D, Loucka M, Csikos A, Ruiz-Ramos M, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Rhee Y, et al. 2016. Estimating the need for palliative care at the population level: a cross-national study in 12 countries. Palliat Med. 31(6):526–536. doi: 10.1177/0269216316671280

- New Zealand Government. 2001. Legislation, health and disability services (Safety) Act, 2001. Wellington: New Zealand Government.

- Nilsen P. 2015. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 10(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

- Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, Jankelowitz SK, Lin IB, Loy CT, Rees G, Sakzewski L, Thomas S, To TP, Wilkinson SA. 2015. Experiences of using the theoretical domains framework across diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 8:139.

- Plaku-Alakbarova B, Punnett L, Gore R. 2018. Nursing home Employee and resident satisfaction and resident care outcomes. Saf Health Work. 9(4):408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2017.12.002

- Ragins B. 2007. Diversity and workplace mentoring relationships: a review and positive social capital approach. The Blackwell handbook of mentoring: a multiple perspectives approach 281-300.

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. 2005. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 173(5):489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051

- Ronaldson S, Hayes L, Carey M, Aggar C. 2008. A study of nurses’ knowledge of a palliative approach in residential aged care facilities. Int J Older People Nurs. 3(4):258–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2008.00136.x

- Ryan R, Deci E. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Schutz A. 1967. The phenomenology of the social world. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Searight H, Gafford J. 2005. Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 71(3):515–522.

- Silvestre J, Bowers B, Gaard S. 2015. Improving the quality of long-term care. J Nurs Regul. 6(2):52–56. doi: 10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30389-6

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Viken B, Solum E, Lyberg A. 2018. Foreign educated nurses’ work experiences and patient safety – a systematic review of qualitative studies. Nurs Open. 5(4):455–468. doi: 10.1002/nop2.146

- Walsh K, Näre L. 2016. Transnational migration and home in older age. New York, NY: Routledge.

- World Health Organisation. 2015a. Palliative care: Fact Sheet No 402. Geneva: WHO. [accessed 2016]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/.

- World Health Organisation. 2015b. World report on ageing and health. Geneva: World Health Organization Geneva.