ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research was to gain an understanding of child consultation in policies for healthy environments in the international evidence base, and examine national and local-level policy and processes regarding child consultation. A systematic mapping review was conducted and grey literature was sought from Aotearoa New Zealand urban and neighbourhood planning, local board, and transport authority websites. A local exemplar project (in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland City) of child engagement in policy planning was presented. Twenty-four articles met the inclusion criteria for the literature search. The literature was synthesised into three broad themes: co-design and planning processes, green space, and physical activity and body size. Despite the existence of high-level national policies, there was little regional consistency. The ‘Healthy Puketāpapa’ project presented provided a replicable model for high-quality, local consultation processes. Child consultation is a method through which decision-makers can respect children as citizens, and the process has been found to be beneficial to all stakeholders involved. This research provides an international perspective of literature, and a methodology that can be replicated in other countries and regions for comparability.

Background

Community participation in designing and developing healthy neighbourhood environments is important for ensuring designs are relevant and appropriate for the community of interest (Kyttä and Kahila Citation2011). Positive outcomes of effective community participation can include policies and actions that facilitate health and health equity into planning and fiscal decision making; support or formation of community identity; and ongoing community engagement in, and guardianship of, neighbourhood environments (Mahjabeen et al. Citation2009; Ismail and Said Citation2015; Kelkar and Spinelli Citation2016; Leyden et al. Citation2017). Localised approaches are needed that fit with community requirements and preferences. It is worth recognising that while models and frameworks exist (Cascetta et al. Citation2015; Kelkar and Spinelli Citation2016), conceptual clarity is still needed in terms of what community participation actually looks like, and this may differ by context. As with general community participation, clarity on exactly what child ‘participation’, ‘consultation’ and related concepts look like and encompass remains lacking (Reid et al. Citation2008; Sanders and Stappers Citation2008; Cele and van der Burgt Citation2015). The degree to which engagement with children occurs can differ, with the most substantial participation evidenced by child initiated and shared decisions with adults (Hart Citation2008). Quality and types of participation across degrees of engagement can also vary (Hart Citation2008; Simovska Citation2008; Hagen et al. Citation2012). No one approach is necessarily better than the other, but rather optimal processes are context-dependent. In the context of this research, the terms participation, engagement, consultation, and co-design are used interchangeably to represent the overarching concept of engaging with children regarding environmental design.

For the most part, research in this space has focused on adult perspectives, despite an acknowledgement of the importance of understanding priorities and needs from ‘people of all ages’ (American Planning Association Citation2017). The United Nations Convention Rights of the Child (UNCROC; United Nations (Citation1989)) and the Child Friendly City Framework for Action (UNICEF Citation2004) prioritise activating child voice for informing neighbourhood design. In Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ), the recent Tamariki Tū, Tamariki Ora: Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy aspires for children to be involved and empowered through representation of youth voice; and happy and healthy, living in healthy, sustainable environments (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2019). Importantly, child-reported perspectives, priorities, and needs were used to inform this national strategy – setting a strong precedent and standard for subsequent policy directives. As a signatory of the UNCROC, NZ has agreed to uphold certain rights and conditions for children, including giving children a voice and representation in government, and listening to children’s views. This is explicit in Article 12 which guarantees the ‘right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight’. These key policy documents all place importance on enabling child voice – respecting their opinions and ensuring their opinions are reflected in policy.

Whether these aspirations are realised is likely influenced by the presence or absence of policies that stipulate the need for (and means by which to undertake) child consultation, engagement, and participation in planning. In NZ, the Child Impact Assessment Tool was developed by NZ’s Ministry of Social Development to support the nation’s commitment to the UNCROC in policy-making processes (Ministry of Social Development Citation2018). Importantly, the tool recognises the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi (foundational document for NZ) as a source of rights for children living in NZ, and stipulates that policy proposals must comply with this. The tool also recommends incorporating views of a diverse range of children and young people when assessing whether policy proposals will improve the wellbeing of children and young people. The recent ‘Child Friendly Planning in the UK’ report by Wood et al. (Citation2019) contextualised child consultation in a UK context. This report provides an excellent platform for other regions to draw from, in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of child consultation in planning environments that promote and support child health. A growing evidence base documents child consultation in planning and the benefits of such approaches (Danenberg et al. Citation2018; Freeman and Cook Citation2019; Witten and Field Citation2019). For example, children see the world through a different lens than adults – enabling them to identify issues and develop innovative solutions that might not otherwise be noticed by adults (Danenberg et al. Citation2018; Freeman and Cook Citation2019). Including recommendations from young people can lead to improved efficacy of interventions, policies, and programmes (Derr et al. Citation2018). Social inclusion (important for child and youth wellbeing) is facilitated through child engagement in plannning. Finally, participation in environmental planning and consultation can lead to children acting as environmental stewards during childhood and beyond (Derr et al. Citation2018).

The purpose of this research is to contribute to this knowledge base through: (1) conducting a systematic mapping review of international literature to identify the prevalence of policies and practices including child consultation, engagement, or participation in urban and neighbourhood planning, and (2) identifying national and local urban planning policies in NZ that describe the inclusion/exclusion of child participation policies.

Methods

Aim 1: literature review

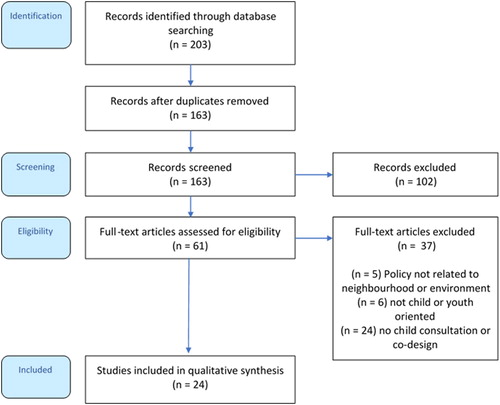

A systematic mapping review (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Miake-Lye et al. Citation2016) in Scopus and PubMed was undertaken. The study protocol is registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/y3erw/) and follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews Checklist (Supplementary material). Studies were eligible at the searching stage if they were: (1) peer reviewed articles published in academic journals, (2) published in the English language, and (3) conducted with human populations. Search terms were identified from MeSH terms, existing literature reviews, and the expertise of the research team ().

Table 1. Search categories and terms used in this review.

Duplicates were removed then titles and abstracts of remaining articles were screened for inclusion. Studies were included if they detailed an urban or neighbourhood planning policy, recommendation, or process that incorporated child consultation, engagement, or participation in some form. All study types (cross-sectional, natural experiments, prospective, retrospective, experimental, longitudinal studies; quantitative, qualitative and mixed/multi methods) were included providing they met other inclusion criteria. Where it was not clear whether articles met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, full text articles were sourced.

Study characteristics and key findings were extracted using a study-specific data extraction form. Variables included study author, year of publication, country, policy/strategy description, information on child consultation, engagement, or participation in urban and neighbourhood planning, and key findings. Key findings were collated into main topic areas, summarised, and synthesised.

Aim 2: national grey literature review

A manual search of websites of urban and community planning authorities, local boards, and transport authorities in NZ was undertaken. The presence or absence of recommendations on child consultation, engagement, or participation in urban and neighbourhood planning, was documented and details were extracted. NZ has 78 local, regional and unitary councils, 74 of which were relevant to this review. Excluded were environmental councils such as Environment Southland, as their policies did not pertain to neighbourhood or community planning. The Significance and Engagement policy (which enables councils to determine whether areas of interest warrant public consultation and outlines consultation processes) of each of the 74 relevant councils was sourced, in addition to the council’s most recent long-term plan. In the event that a long-term plan was not made available, the most recent annual plan was sought. Additionally, any separate youth or consultative policy that each local council may have made available was sourced. Descriptive data for the presence or absence of recommendations on child consultation, engagement, or participation in urban and neighbourhood planning policies and strategies was generated.

An exemplar project, ‘Healthy Puketāpapa’ was identified and detailed as an example of local-level incorporation that is recommended through local council action. Puketāpapa is a local board area of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland City, NZ’s largest city and home to over a third of its population. In 2018, the Puketāpapa local board created ‘Healthy Puketāpapa’, a series of policies and strategies focused on the health and wellbeing of the community (Puketāpapa Local Board Citation2019; Wilson Citation2019). The main goal of Healthy Puketāpapa is to enable feelings of safety, comfort, happiness, and satisfaction in the people of Puketāpapa, as well as promoting holistic health and wellbeing. There are two significant document types under Healthy Puketāpapa – the Strategic Framework (5–10 year plan) (Puketāpapa Local Board Citation2019), which is a long-term development strategy, and the Action Plan (2 year plan) (Wilson Citation2019) which is concerned with implementation of the strategy. Both documents are guided by Te Pae Mahutonga (Durie Citation1999), a holistic Māori (indigenous people of NZ) health model and were developed in collaboration with the community, including with children (defined as aged <16 years). Examples of community-identified neighbourhood needs in consultation were to improve access to water fountains, to improve safety for walking and cycling, and to create public spaces (including green spaces) that support activity for people of all ages. Thus, Healthy Puketāpapa was identified as an optimal exemplar project to demonstrate a model for weaving child consultation throughout strategy and policy document development for healthy environments.

Results

Aim 1: literature review

The initial search yielded 203 results, of which 24 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review (). No articles focused on policies that stipulated the need for child consultation, engagement, or participation in urban and neighbourhood planning. However, the 24 articles included did cover the four topic areas to some extent. Two approaches to child consultation were evident – one approach centred child consultation as the primary phenomenon of interest (n = 11) while the other used child consultation as an element of methodology or as a particular approach to a pre-existing issue (n = 13) (). Focus groups were commonly employed to gather children’s perspectives on the built environment and other relevant issues. Alternative techniques such as photovoice (n = 3), child community audits (n = 4), child-led workshops (n = 1) and mapping techniques (n = 1) were also used. Research predominantly arose from the USA, with representation also from Europe, Africa, and Australia.

Table 2. Characteristics and key findings of included studies.

Co-design and planning processes

Children’s co-design in retrofitting a particular built space or feature was outlined in two articles (Carroll et al. Citation2017; Pawlowski et al. Citation2017). Carroll et al. (Citation2017) investigated the redesign of a city square that occurred during a consultative process with children. The methods presented provide helpful guidelines for other researchers or authorities to conduct effective child consultation. Key aspects included a child friendly audit which involved children visiting and playing in the city square as well as taking pictures. Another element was a fun and engaging workshop which involved analysing photographs and annotating a map of the area. From this, the authors created a plan which was fed back to the children and cross-referenced with the children’s ideas. In this case, the authors noted that this consultation and redesign process was both a first for Auckland Council and has seldom been investigated within research spheres. Additionally, the process fulfilled the study criteria for enabling effective and meaningful participation, with metrics including giving children ‘appropriate support’ to participate. Similarly, Pawlowski et al. (Citation2017) asserts that children in their study were involved in co-design, where spaces were designed with children’s input, not just for children. Key methodological aspects of this study that could be reproduced included supporting children to create collages and models of potential urban installations.

Benefits and barriers

Co-design processes and the inclusion of children in decision-making were seen as beneficial to children (Carlson et al. Citation2012; Carroll et al. Citation2017; Frerichs et al. Citation2018). In many cases, educational and development-focussed programmes (all with at least a minor focus on consultation or urban and neighbourhood design) incorporated or were centred around child development. For example, in many cases researchers identified youth as having learned valuable skills and competencies (Nelson Citation2008; Lapalme et al. Citation2014; Frerichs et al. Citation2018). Children’s self-efficacy and ability to participate in civic processes was seen to increase in a study of focus groups about HIV in terms of neighbourhood development, health promotion, and civics (Carlson et al. Citation2012). Winter et al. (Citation2016) recruited children as citizen scientists which helped to develop their skills in technology use, environmental science, and urban design as well as contributing to positive change in their local environments. The researchers suggested this process amplified the voices of marginalised youth, as it provided youth with a platform to engage with decision-makers and important community stakeholders regarding their environments.

There were numerous barriers to consultation processes involving youth. Firstly, it was reported that children, particularly in minority communities, felt hesitant to get involved (Winter et al. Citation2016). According to these researchers, this may be due to lack of trust of researchers and decision-makers. A similar level of hesitancy was reported in the study by Arredondo et al. (Citation2013). In this research, there was a high dropout rate from the initial surveys to the child-led audits, which made assessing the success of consultations difficult. Researchers commented that children did not feel confident participating in such in-depth research and leading the process. In other cases, even where participation rates were high it was not always feasible to execute children’s visions completely. For example, according to the research by Carroll et al. (Citation2017) pedestrianising the area of interest (i.e. making it exclusively for pedestrians and removing all motorised transport modes), as per children’s recommendations, was not possible due to pressure from tradespeople and shop owners in the local area (who also felt that they were not adequately consulted). In the case of Rodriguez et al. (Citation2019), the extent to which children were able to disseminate their research as citizen scientists through, for example, attending conferences, was limited. The students were not able to attend an environmental conference due to liability issues.

The built environment

The built environment – referring to the man-made physical structures and spaces in cities and neighbourhoods, including any feature that has been created or manipulated through human action (Srinivasan et al. Citation2003) – was a prominent focus in the literature. Authors also used phrases such as ‘urban environments’, (Davis and Jones Citation1997) and ‘urban sprawl’ (Goltsman et al. Citation2009) to describe the built environment. Thirteen of the 24 included articles discussed the built environment in relation to child consultation, neighbourhoods, and co-design.

The literature emphasised that children’s views on the built environment are important because children interact with the built environment differently to adults, and their local built environment often has a significant impact on their lives. For example, the safety and suitability of pavements and roads can significantly impact children’s abilities to walk to and from school due to safety concerns and other barriers (Nelson Citation2008; Hanssen Citation2019; Rodriguez et al. Citation2019).

Current systems and structures were foci of discussion in terms of positive and negative environmental attributes (Davis and Jones Citation1997; Trayers et al. Citation2006). Commonly, the unique insights of children were used to identify and value environmental attributes that were seen to be working well or as being good examples from children’s perspectives (Davis and Jones Citation1997; Hackett et al. Citation2015; Hanssen Citation2019). Identification of positive attributes helped to identify facilitators for children’s physical activity, feelings of safety, and health. For example, Hanssen (Citation2019) created an innovative process called the ‘children track methodology’. This allowed children to mark off local areas of interest and to discuss their neighbourhood, including features that they enjoyed and valued, or more negative features, and their use of the built environment. Negative aspects of the built environment were highlighted as potential areas for policymakers to create change and to spur the introduction of new interventions (Hackett et al. Citation2015; Rodriguez et al. Citation2019). For instance, one study found that neglected spaces and inaccessible footpaths were barriers to children’s physical activity in a low-income United States suburb, and were identified as areas for improvement (Hackett et al. Citation2015).

Green space

Green space was the primary phenomenon of interest in two articles (Goltsman et al. Citation2009; Arredondo et al. Citation2013). Green space refers to environments such as parks that are outdoors, open public spaces which include ‘natural’ features such as trees and plants, water, and other similar aspects. Recreating natural environments was the focus of Goltsman et al. (Citation2009) in order to facilitate children’s play. The authors considered there to be a preoccupation with artificial playground equipment and children’s spaces, rather than shared, integrated environments. Arredondo et al. (Citation2013), on the other hand, was more concerned about access to, and improvement of, existing green space. Methodologically, Arredondo et al. (Citation2013) employed youth as leaders to survey and suggest improvements to these green spaces. Goltsman et al. (Citation2009) held an open day for children to explore the park and to contribute ideas for improvement. This meant that the park design was based on community needs and aspirations. Overall, these articles show that urban design and neighbourhood planning do not only involve creating or improving spaces, but also facilitating access through child-centred improvements and changes.

Physical activity and body size

Physical activity featured as a central area of concern in eight articles and body size in four. Physical activity was most commonly explored in the context of the built environment and green space, and how these elements can facilitate or hinder activity (Aarts et al. Citation2009; Badland et al. Citation2009; Finkelstein et al. Citation2017). Body size was often considered to be a consequence of urban and neighbourhood planning. In particular, researchers were concerned with walkability and food choice, and how these factors relate to body size (Aarts et al. Citation2009; Finkelstein et al. Citation2017).

Consulting with children on barriers to physical activity amplified children’s unique perspectives on this issue. For example, a study by Hackett et al. (Citation2015) found children to be highly aware of the assets in their local community which encouraged physical activity and barriers which hindered activity. Assets included a local farmer’s market and parks, whereas drawbacks included inaccessible footpaths and neglected spaces. This information was used as motivation to form the Roosevelt Environmental Justice Coalition which appealed for federal funding to further environmental advocacy, particularly amongst youth. Similarly, Davis and Jones (Citation1997) found that children considered walkability and proximity to facilities to be assets in their local area. Barriers included noise and perceptions of safety as well as rubbish and vandalism.

In terms of body size, many researchers, including Corsino et al. (Citation2013) and Sharifi et al. (Citation2015) were motivated by the childhood obesity epidemic and wanted to gain the unique perspectives of children in order to investigate causal pathways and potential solutions. Sharifi et al. (Citation2015) conducted focus groups with children who lived in obesogenic environments but were able to reduce their body mass index. Children provided information on both personal and neighbourhood attributes that they felt supported their weight loss. Children discussed many neighbourhood attributes that aided or hindered their lifestyle change, such as accessibility of parks and the food environment. The authors have outlined these factors as potential guidelines for designing interventions, particularly for public health practitioners and policy makers.

Summary

Studies identified were diverse in their topics of interest (including green spaces, children’s physical activity and body size, and informing built environment design), methods (including photovoice, focus groups, audits, workshops, and participatory mapping), participants, and region of study. Methods employed were outlined in detail in two studies. Overall, child co-design and participatory approaches were seen to be beneficial, however a number of barriers existed, including a reluctance of children to participate, and challenges with actualising children’s visions.

Aim 2: aotearoa New Zealand policy environment

Here, we shift from a broader international focus on extant literature to describing the national policy context in NZ. The NZ government is divided into central and local branches. Central government encompasses the legislature, executive, and judiciary, with responsibilities including housing, education, justice, foreign policy, health, and immigration, amongst other areas. Additionally, NZ has 78 local councils with responsibilities such as water, rubbish, public transport, and roads. While local governments are bound to some central government regulations and requirements, they operate relatively autonomously to represent their residents. Consequently, there is significant variation in the policies and practices of each local council.

One protocol that all local councils must follow is creating long-term and annual plans for their area. These plans provide a consistent metric for assessing child consultation. All 74 local council plans had some mention of consultation and public involvement in the creation of the plans themselves, as well as general consultation practices. However, child consultation was not mandated across councils, and had a more prominent role in some councils compared to others.

At a national level, both the Department of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet and the Ministry of Social Development have created reports and policies to uphold the UNCROC (). Tamariki Tū, Tamariki Ora: NZ’s First Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy utilised both child consultation itself and emphasised the importance of including children’s opinions in decision-making across the government generally (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Citation2019). The Ministry of Social Development’s Agenda for Children (Ministry of Social Development Citation2002) laid out what is currently being done to enhance child consultation throughout central and local government. This included representing children’s views in family court, as well as creating youth boards and representational roles at a local government level and in schools. Additionally, the report detailed a child consultation process, which elicited children’s views on how they would like their voices to be heard in government. The Ministry of Social Development’s Child Impact Assessment Tool can be used by government and non-government agencies to assess whether any proposed policy or legislation is likely to support child and youth wellbeing and includes child and youth consultation as a key evaluation component (Ministry of Social Development Citation2018). Despite this supportive policy environment at the national level, there was inconsistent evidence of these policy directives being implemented at the local level.

Table 3. Key national-level documents involving child consultation or participation for healthy environments.

The Local Government Act (Citation2002) provides central government guidelines on how local councils must operate. Of note is the article which obliges local councils to consult ‘persons who will or may be affected by, or have an interest in, the decision or matter’. Because children are citizens impacted by governmental decisions, this article implies that child or youth consultation is necessary, despite no explicit mentions of this. Under the Local Government Act (Citation2002), each local council must have a Significance and Engagement Policy in place. The council, having been elected to make decisions on behalf of its residents, cannot and should not consult the public on every issue. Thus, Significance and Engagement Policies enable councils to determine whether areas of interest warrant public consultation. This policy also outlines the ways in which councils can and should engage with the public in consultation processes. Engagement tools may differ depending on the demographic the council is aiming to engage with; for example, social media may be a suitable consultation tool for youth, but not for elderly people.

Each of the 74 local councils’ Significance and Engagement Policy is outlined in the supplementary material. Based on an analysis of each of these policies, the basic premise is the same within each local council. They outline when and how consultation will happen, list strategic assets, and define various levels of community engagement. However, there is some scope for each local council to define particular areas of importance, one of these being child consultations. While all 74 local councils state in their Significance and Engagement Policy that they consult those who will be affected by the decision, only 32 local councils explicitly mentioned child or youth engagement in their policy. The scope of the issues addressed differed between each of the 32 councils. Some councils directly addressed youth as important stakeholders in decision-making or outlined the purpose of local Youth Councils in consultation processes, while others took a broader focus on youth engagement. While there are numerous procedures that local councils must follow, including under the Local Government Act (Citation2002), councils have autonomy on many issues. This autonomy extends to youth councils. The purpose of youth councils is to amplify youth voices in the community and to gather a youth perspective on significant issues. Forty eight local councils had current, established youth councils or similar groups. The remaining 25 local councils either had no youth council or youth group (n = 18), were currently in the process of establishing a youth council (n = 2) or had a youth council that was currently inactive (n = 5).

Forty one local councils had at least one explicit mention of child or youth consultation in their long-term or annual plans. This ranged from identification of youth as stakeholders or explanations of the role of the Youth Council, to detailed plans regarding youth consultation. Additionally, some local councils had a separate policy regarding youth consultation. For example, Central Hawkes Bay Council created a Youth Action Plan which discussed youth development at length, including consultation processes and representation.

Exemplar project – healthy Puketāpapa

The previous section identified inconsistencies in policies for child consultation and participation in urban planning activities at the local council level. Here we narrow down to one local council area in NZ and present an examplar project from this council, Healthy Puketāpapa, that demonstrates processes for and outcomes of child participation in policy development for health promoting environments. The consultation process for strategy development was held from April to May 2019, and involved numerous hui (meetings), workshops, online consultations and a review of the Puketāpapa Children’s Panel. This panel is made up of 89 children in school (aged approximately 7–11 years old and representing 19 different ethnicities) from 8 local primary (elementary) and intermediate (junior high) schools. Children’s voice was developed through interactive 2-hour discussion workshops at each school with the primary aim of developing a localised action for the children and school community to implement on a health topic of their choice. Strong themes emerged from this panel including mental health and environmental issues including climate change. Results from the consultation process in its entirety were consolidated and presented to a co-creation group (comprising individuals from the community and those with specific topic expertise) that led the design and development of the Strategic Framework and Action Plan. An equity review on the draft plan and framework was completed by the Healthy Puketāpapa Project Manager using the Ministry of Health NZ Health Equity Assessment Tool (a planning tool encompassing 10 questions to assess interventions for current or future impact on health inequalities; Signal et al. (Citation2008)) and feedback from stakeholders and the community was sought through hui and online consultation. The resulting Strategic Framework and Action Plan set out five priorities that reflect the community consultation. Children’s insights with regard to play, engaging with neighbours and family and protecting the environment are prominent and reflected in one of five priority areas and associated actions within the plan – ‘Encourage Movement’ (). These perspectives has also informed the development of one of three ‘signposts’, Wāhi Takāro Wāhi Ora – Connecting People Through Welcoming Spaces, that provides directions for the focus of project delivery ().

Figure 2. ‘Wāhi Takāro Wāhi Ora – connecting people through welcoming spaces’ – one of three key ‘signposts’ in the Healthy Puketāpapa Action Plan.

Table 4. Actions and delivery time frames for the ‘Encourage Movement’ priority in the Healthy Puketāpapa Action Plan.

Summary

Policies exist at a national level in NZ to support (but not mandate for) children’s participation and consultation in policy development for health promoting environments. Over half of the 74 local councils in NZ showed at least some awareness and made mention of child consultation. Overall, there was little consistency across local councils in policies for child participation and consultation in planning processes.

Discussion

Child consultation in the development of healthy environments is not a new concept, yet its prevalence in academic and policy contexts remains low. This research aimed to contribute to this evidence base. The small amount of literature identified through the mapping review was derived from a wide range of different academic perspectives and covers a number of phenomena. Relatively few concrete policies or documents existed relating to child consultation within the international literature. The built environment featured in the bulk of the literature – an unsurprising finding considering environmental design is regulated by policy and affects children’s activity levels, health, and wellbeing. Several articles assessed child consultation in the development and redesign of aspects of the built environment (Carroll et al. Citation2017; Pawlowski et al. Citation2017).

Benefits and barriers

Authors including Carroll et al. (Citation2017) found that child-friendly, engaging and fun consultation processes were possible and beneficial for children, researchers, and policy-makers alike. Also notable were the numerous barriers to child consultation such as council constraints and pushback from other members of the community who also felt deserving of a special consultative process (Carroll et al. Citation2017). Macro-level barriers to community consultation have been previously identified, perhaps most notably Fung’s (Citation2015) identification of the absence of systematic leadership, lack of consensus by decision makers (the ‘elite) on the place of community participation, and limited scope and power of participatory innovations. Time-related barriers have also been highlighted by Del Gaudio et al. (Citation2017) namely local rhythm, community participation speed, timing norms of partners, and timing required for achieving change. These barriers likely existed in relation to the research identified in this review, but were not articulated here. It is possible this was because the main focus of research identified research that included child participation processes (and so to some extent already having overcome these broader issues).

Children’s insights

Children gave significant insight on the built environment. Some ideas emerged which would not have been considered by academics or other community members. A clear example of this is given by Davis and Jones (Citation1997), where it was found that children were particularly concerned about walkability while adults were seemingly more preoccupied with parking and car-related issues. Green spaces and parks also arose as a key area of interest for child participation in environmental design, aligning with earlier research with children and adolescents (who also appreciated neighbourhood environments that were safe and supported social relationships; e.g. see Passon et al. (Citation2008) and Egli et al. (Citation2019)). In the literature, children were able to assess features of green spaces in co-design processes and initiated potential improvements. Importantly, the literature considered green space to be an environmental asset that could be used to encourage physical activity and improve health across numerous domains (Goltsman et al. Citation2009; Arredondo et al. Citation2013). Indeed, systematic reviews have demonstrated the importance of green space for children’s physical and mental health (Twohig-Bennett and Jones Citation2018; Vanaken and Danckaerts Citation2018). Moreover, children’s outdoor natural experiences can lead to environmental action in young environmental leaders (Arnold et al. Citation2009) and environmental stewardship in later life (Chawla Citation1999; Broom Citation2017).

Direct benefits to children as participants

Another issue explored in the literature was using consultative processes to benefit and uplift youth. Rather than trying to solve a particular issue and create change in the community, this subsection of the literature used child consultation to directly benefit study participants. For example, a number of articles were focused on consultative processes which developed youth civic skills, aligning with findings from Derr et al. (Citation2018). Many other articles attempted to benefit children and youth in their communities of interest, for example through facilitating easy access to green space and other healthy environments. However, in this subsection of the literature, articles were set apart by the fact that the interventions were targeted at the study participants themselves (Nelson Citation2008; Carlson et al. Citation2012; Winter et al. Citation2016).

Aotearoa New Zealand policy

Most policies and plans were guidelines for governments and organisations to follow in their general practices. In addition, while national-level guidance in NZ related to child consultation exists, there was little specific/mandated guidance to local councils on how to engage children and youth in urban and neighbourhood planning processes. Many reports or policies that existed were ad-hoc. This was particularly clear within the local government context where some governments have clear and stringent policies for child consultation and others neglect child consultation in their policies. Overall, these findings reflect the fact that, traditionally, children have been marginalised and excluded from decision-making processes – governments, policy makers and planners have only recently begun to realise the critical importance of including children in such processes.

In order to put child consultation at the forefront in decision-making processes in planning, it would be more effective to provide urban planning guidelines across local councils that comes from national-level policy such as the work from the Office of the Children’s Commissioner and the Ministry of Social Development’s Child Impact Assessment Tool. This requirement is especially significant because of the large number of local councils in NZ. This makes it difficult to have consistency and widespread representation of youth unless higher-level policy is created to regulate the local councils, as is the case with the Local Government Act (Citation2002). However, this is not to say that change cannot be driven at a grassroots, local level. Numerous case studies demonstrate that local councils have effected significant change in the area of child consultation. Additionally, a few simple additions to local council policy could have a significant impact. For example, 16 local councils have a Youth Council that is not mentioned in their Significance and Engagement Policy. The addition of explicit mentions of the role of the Youth Council in consultations could be beneficial. Along with such changes, national-level guidelines on how to engage children with planning would simply ensure that every local area is consulting with children at an adequate level.

International policy

While this literature review focused specifically on the NZ policy environment, other similar developed OECD nations approach child consultation differently. For example, Australia has six state governments as opposed to numerous local councils. All six state governments have at least some legislation or special report on the role of children and youth consultation in their government, although there is significant variation between states. For example, New South Wales has a specific branch of government called the Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People. South Australia, on the other hand, has a specific report detailing child voice (Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People Citation2016) but no special advocate or position to enact this.

Despite having some national-level guidance on involving children and youth with decision-making, institutional systems and policies within local governments can also hinder developing participatory initiatives (Freeman et al. Citation2003). Several factors including entrenched ways of working, limited time frames and training for planning professionals to work with children, lack of budgets and resources, and hierarchical power structures within local councils (Freeman et al. Citation2003) could help explain why engaging children in decision-making and planning in NZ has, to date, been ad-hoc. Understanding how participatory planning can be integrated from the perspectives of planners is also necessary (Freeman and Cook Citation2019). Previous case studies with planners in NZ reported that an overwhelming majority wanted to be more actively engaged with children and youth and highlighted the need for training and good-practice guidelines (Freeman and Aitken-Rose Citation2005).

Recently, there has been an increase in policy-based research in the area of child consultation. For example, Wood et al. (Citation2019) published ‘Child Friendly Planning in the UK’, a report on this subject matter. This review concerned itself in part with UNCROC article 12 and found that, within the UK, children are largely absent in policy considerations. The release of this report, amongst others, demonstrates that the issue of child consultation is coming to the forefront and further investigation within other countries, such as this mapping review, will add to the current body of literature and further create incentive for governments to change their practice and policies. Furthermore, recent work by Witten and Carroll (Citation2019) and Freeman and Cook (Citation2019) provides timely and useful guidance for planners to undertake meaningful engagement with children, providing methods, techniques and country-specific examples of good practice.

Exemplar project: healthy Puketāpapa

The community of Puketāpapa is an example of a community that has a strong focus on health and wellbeing, with many grassroots and community actions related to health, development, and rights having been initiated in the local area. Healthy Puketāpapa is an example of a local board exercising its autonomy to further uplift the community and provide a platform for children’s views. However, not all local areas have such a strong, mobilised community or a local board so strongly committed to respecting the rights of children. Through the Healthy Puketāpapa initiative, the government was able to empower the community to continue and strengthen actions already taking place, and to more directly influence policy at a local government level. Puketāpapa is one of the few local boards that has centred and legitimised child consultation to such a significant degree. This is likely due to community influence and aspirations as well as political incentives and push from the local board.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this mapping review. The primary drawback of this review is its scope – only NZ policy was examined in detail. This means that there is less relevance of the policy considerations in this review internationally. However, this could also be a strength because it has resulted in an in-depth exploration of one policy environment, as well as a short comparison to other similar contexts such as the UK. Another limitation of this review is its methodology. Compared to systematic reviews, mapping reviews provide a broad overview rather than a comprehensive identification and evaluation of the academic literature. However, the mapping review approach was chosen specifically for this topic due to the general limited evidence available currently. Consequently, this mapping review was able to generally demonstrate the current state of the literature and to emphasise the need for deeper exploration. Similarly, there was a small sample of literature both from the initial search and after exclusions which may have limited the breadth covered in the review.

Conclusion

This literature review has brought forward many concerns relevant to child consultation and its impact on public health. Firstly, there is a need for more investigation into this topic at both a local and international level, by both academics and government decision-makers. The literature that currently exists demonstrates the potential benefits child consultation can have both for the child themselves, the community in question. This area of research and policy is promising in its ability to enact change and pin down drivers of large-scale social issues, in addition to uplifting children as citizens and enhancing their rights. Encouraging and enabling children’s participation in urban planning beyond ad-hoc approaches in an on-going and systematic way could lead to empowering a new generation of youth to engage with planning, redressing previous power imbalances. While the Healthy Puketāpapa project sets out a framework for local governments or even organisations to strengthen child consultation, it would be even more effective and powerful if child consultation was organised on a wider scale, for example through national legislation and nationwide programmes. Children have the right to be consulted, as set out in the UNCROC, and these rights should be guaranteed for all, not just those who happen to live in particular parts of a country.

Supplementary material

Download MS Word (43.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ailsa Wilson (Auckland Council; Auckland District Health Board) for providing input to this manuscript. ES was supported by a University of Auckland Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences summer studentship. VE is supported by a Lotteries New Zealand Health Research Grant. MS is supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Sir Charles Hercus Research Fellowship (17/013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarts MJ, van de Goor IA, van Oers HA, Schuit AJ. 2009. Towards translation of environmental determinants of physical activity in children into multi-sector policy measures: study design of a Dutch project. BMC Public Health. 9:396. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-396

- American Planning Association. 2017. Healthy communities policy guide. Chigago, Illinois, (USA): Author.

- Arnold HE, Cohen FG, Warner A. 2009. Youth and environmental action: perspectives of young environmental leaders on their formative influences. The Journal of Environmental Education. 40(3):27–36.

- Arredondo E, Mueller K, Mejia E, Rovira-Oswalder T, Richardson D, Hoos T. 2013. Advocating for environmental changes to increase access to parks: engaging promotoras and youth leaders. Health Promotion Practice. 14(5):759–766.

- Auckland Council. 2014. Auckland design manual: designing child friendly parks & open spaces. Auckland (NZ): Author.

- Badland HM, Schofield GM, Witten K, Schluter PJ, Mavoa S, Kearns RA, Hinckson EA, Oliver M. 2009. Understanding the relationship between activity and neighbourhoods (URBAN) study: research design and methodology. BMC Public Health. 9:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-224

- Boelens M, Windhorst DA, Jonkman H, Hosman CMH, Raat H, Jansen W. 2019. Evaluation of the promising neighbourhoods community program to reduce health inequalities in youth: a protocol of a mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health. 19:555. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6901-3

- Broom C. 2017. Exploring the relations between childhood experiences in nature and young adults’ environmental attitudes and behaviours. Australian Journal of Environmental Education. 33(1):34–47.

- Carlson M, Brennan RT, Earls F. 2012. Enhancing adolescent self-efficacy and collective efficacy through public engagement around HIV/AIDS competence: a multilevel, cluster randomized-controlled trial. Social Science and Medicine. 75(6):1078–1087.

- Carroll P, Witten K, Stewart C. 2017. Children are citizens too: consulting with children on the redevelopment of a central city square in Auckland, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Built Environment. 43(2):272–289.

- Cascetta E, Carteni A, Pagliara F, Montanino M. 2015. A new look at planning and designing transportation systems: a decision-making model based on cognitive rationality, stakeholder engagement and quantitative methods. Transport Policy. 38:27–39.

- Cele S, van der Burgt D. 2015. Participation, consultation, confusion: professionals’ understandings of children’s participation in physical planning. Children’s Geographies. 13(1):14–29.

- Chawla L. 1999. Life paths into effective environmental action. The Journal of Environmental Education. 31(1):15–26.

- Corsino L, McDuffie JR, Kotch J, Coeytaux R, Fuemmeler BF, Murphy G, Miranda ML, Poirier B, Morton J, Reese D, et al. 2013. Achieving health for a lifetime: a community engagement assessment focusing on school-age children to decrease obesity in Durham, North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal. 74(1):18–26.

- Danenberg R, Doumpa V, Karssenberg H. 2018. The city at eye level for kids. Amsterdam (NL): STIPO Publishing.

- Davis A, Jones L. 1997. Whose neighbourhood? Whose quality of life? Developing a new agenda for children's health in urban settings. Health Education Journal. 56(4):350–363.

- Del Gaudio C, Franzato C, de Oliveira AJ. 2017. The challenge of time in community-based participatory design. Urban Design International. 22(2):113–126.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2019. Tamariki tū, Tamariki Ora: child and youth wellbeing strategy. Wellington (NZ): Author.

- Derr V, Chawla L, Mintzer M. 2018. Placemaking with children and youth. Participatory practices for planning sustainable communities. (NY): NYU Press, New Village Press.

- Durie M. 1999. Te Pae Māhutonga: a model for Māori health promotion. Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand Newsletter. 49. http://hauora.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/TePaeMahutonga.pdf

- Egli V, Mackay L, Jelleyman C, Ikeda E, Hopkins S, Smith M. 2019. Social relationships, nature and traffic: findings from a child-centred approach to measuring active school travel route perceptions. Children’s Geographies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1685074.

- Finkelstein DM, Petersen DM, Schottenfeld LS. 2017. Promoting children's physical activity in low-incomecommunities in Colorado: what are the barriers and opportunities? Preventing Chronic Disease. 14(12):170111. http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.170111

- Fredriksson I, Geidne S, Eriksson C. 2018. Leisure-time youth centres as health-promoting settings: experiences from multicultural neighbourhoods in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 46(20_suppl):72–79.

- Freeman C, Aitken-Rose E. 2005. Future shapers: children, young people, and planning in New Zealand local government. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 23(2):227–246.

- Freeman C, Cook A. 2019. Children and planning. London: Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd.

- Freeman C, Nairn K, Sligo J. 2003. ‘Professionalising’ participation: from rhetoric to practice. Children's Geographies. 1(1):53–70.

- Frerichs L, Hassmiller Lich K, Young TL, Dave G, Stith D, Corbie-Smith G. 2018. Development of a systems science curriculum to engage rural African American Teens in understanding and addressing childhood obesity prevention. Health Education and Behavior. 45(3):423–434.

- Fung A. 2015. Putting the public back into governance: the challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review. 75(4):513–522.

- Goltsman S, Kelly L, McKay S, Algara P, Larry W, Wight L. 2009. Raising “free range kids”: creating neighborhood parks that promote environmental stewardship. Journal of Green Building. 4(2):90–106.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 26:91–108.

- Hackett M, Gillens- Eromosele C, Dixon J. 2015. Examining childhood obesity and the environment of a segregated, lower-income US suburb. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare. 8(4):247–259.

- Hagen ES, Røsvik SM, Høiseth M, Boks C. 2012. Co-designing with children: collecting and structuring methods. NordDesign; August 22–24; Aalborg, Denmark.

- Hanssen GS. 2019. The social sustainable city: how to involve children in designing and planning for urban childhoods?. Urban Planning. 4( 1TheTransformativePowerofUrbanPlanning):53–66.

- Hart RA. 2008. Chapter 2, stepping back from ‘the ladder’: reflections on a model of participatory work with children. In: Reid A, Jensen BB, Nikel J, et al., editors. Participation and learning perspectives on education and the environment, health and sustainability. Dordrecht, NL: Springer; p. 19–32.

- Hinkle AJ, Sands C, Duran N, Houser L, Liechty L, Hartmann-Russell J. 2018. How food & fitness community partnerships successfully engaged youth. Health Promotion Practice. 19(1_suppl):34S–44S.

- Ismail WAW, Said I. 2015. Integrating the community in urban design and planning of public spaces: a review in Malaysian cities. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 168:357–364.

- Kelkar NP, Spinelli G. 2016. Building social capital through creative placemaking / Construção de capital social através do placemaking. Strategic Design Research Journal. 9(2):54–66.

- Kyttä M, Kahila M. 2011. SoftGIS methodology – building bridges in urban planning. GIM International (The Global Magazine for Geomatics. 25(3):37–41.

- Lapalme J, Bisset S, Potvin L. 2014. Role of context in evaluating neighbourhood interventions promoting positive youth development: a narrative systematic review. International Journal of Public Health. 59(1):31–42.

- Leyden KM, Slevin A, Grey T, Hynes M, Frisbaek F, Silke R. 2017. Public and stakeholder engagement and the built environment: a review. Current Environmental Health Reports. 4:267–277.

- Linton LS, Edwards CC, Woodruff SI, Millstein RA, Moder C. 2014. Youth advocacy as a tool for environmental and policy changes that support physical activity and nutrition: an evaluation study in San Diego County. Preventing Chronic Disease. 11:E46. eng.

- Mahjabeen Z, Shrestha KK, Dee JA. 2009. Rethinking community participation in urban planning: the role of disadvantaged groups in Sydney Metropolitan Strategy. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies. 15(1):45–63.

- Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. 2016. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic Reviews. 5:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x.

- Ministry of Social Development. 2002. New Zealand’s agenda for children. Wellington (NZ): Author.

- Ministry of Social Development. 2003. Involving children, a guide to engaging children in decision-making. Wellington (NZ): Author.

- Ministry of Social Development. 2018. Improving the wellbeing of children and young people in New Zealand. Child impact assessment guide. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Governnment.

- Ministry of Youth Development. 2008. A guide for local government - an introduction to youth participation. Wellington (NZ): Author.

- Ministry of Youth Development. 2009. Keepin’ it real, a resource for involving young people in decision-making. Wellington (NZ): Author.

- Nelson KM. 2008. Designing healthier communities through the input of children. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 14(3):266–271.

- Office of the Advocate for Children and Young People. 2016. The NSW strategic plan for children and young people 2016–2019. Strawberry Hills, NSW, Australia: Author.

- Parliamentary Counsel Office. 2002. Local government act 2002 No 84. Wellington, (NZ): Author.

- Passon C, Levi D, del Rio V. 2008. Implications of adolescents’ perceptions and values for planning and design. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 28:73–85.

- Pawlowski CS, Winge L, Carroll S, Schmidt T, Wagner AM, Nørtoft KPJ, Lamm B, Kural R, Schipperijn J, Troelsen J. 2017. Move the neighbourhood: study design of a community-based participatory public open space intervention in a Danish deprived neighbourhood to promote active living. BMC Public Health. 17(1):1–10.

- Puketāpapa Local Board. 2019. Healthy Puketāpapa: a strategic health and wellbeing framework. Auckland (NZ): Author.

- Reid A, Jensen BB, Nikel J, Simovska V. 2008. Participation and learning. perspectives on education and the environment, health and sustainability. Dordrecht, NL: Springer.

- Rodriguez NM, Arce A, Kawaguchi A, Hua J, Broderick B, Winter SJ, King AC. 2019. Enhancing safe routes to school programs through community-engaged citizen science: two pilot investigations in lower density areas of Santa Clara County, California, USA. BMC Public Health. 19(1):256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6563-1.

- Sanders EB-N, Stappers PJ. 2008. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Design. 4(1):5–18.

- Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman RE, Cunningham C, Marshall R, Taveras EM. 2015. Engaging children in the development of obesity interventions: exploring outcomes that matter most among obesity positive outliers. Patient Education and Counseling. 98(11):1393–1401.

- Signal L, Martin J, Cram F, Robson B. 2008. The health equity assessment tool: a user’s guide. Wellington (NZ): Ministry of Health.

- Simovska V. 2008. Chapter 4, learning in and as participation: a case study from health-promoting schools. In: Reid A, Jensen BB, Nikel J, editors. Participation and learning perspectives on education and the environment, health and sustainability. Dordrecht, NL: Springer; p. 61–80.

- Srinivasan S, O’fallon LR, Dearry A. 2003. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. American Journal of Public Health. 93(9):1446–1450.

- Trayers T, Deem R, Fox KR, Riddoch CJ, Ness AR, Lawlor DA. 2006. Improving health through neighbourhood environmental change: are we speaking the same language? A qualitative study of views of different stakeholders. Journal of Public Health. 28(1):49–55.

- Twohig-Bennett C, Jones A. 2018. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environmental Research. 166:628–637.

- UNICEF. 2004. Building child friendly cities. A framework for action. Florence (Italy): UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

- United Nations. 1989. The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. London (UK): UNICEF UK.

- Vanaken GJ, Danckaerts M. 2018. Impact of green space exposure on children’s and adolescents’ mental health: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15(12):2668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15122668.

- Watson-Thompson J, Fawcett SB, Schultz JA. 2008. A framework for community mobilization to promote healthy youth development. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 34(3(Suppl)):S72–S81.

- Wilson A. 2019. Healthy Puketāpapa: a health and wellbeing action plan 2019–2021. Auckland (NZ): Puketāpapa Local Board.

- Winter SJ, Goldman Rosas L, Padilla Romero P, Sheats JL, Buman MP, Baker C, King AC. 2016. Using citizen scientists to gather, analyze, and disseminate information about neighborhood features that affect active living. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 18(5):1126–1138.

- Witten K, Carroll P. 2019 . Engaging children in public space design: tips for designers. Auckland (NZ). [accessed 2020 Feb 24]. https://kidsinthecity.ac.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Tips-for-Designers.pdf.

- Witten K, Field A. 2019. Chapter 11, Engaging children in neighborhood planning for active travel infrastructure. In: Waygood EOD, Friman M, O’lsson LE, et al., editors. Transportation and children’s well-being. Amsterdam: Elsevier; p. 199–216.

- Wood J, Bornat D, Bicquelet-Lock A. 2019. Child friendly planning in the UK: a review. London: Royal Town Planning Institute.