?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study investigates whether coverage of family violence that resulted in a death event in New Zealand mainstream media is biased across a range of key factors – namely the gender, ethnicity and age of victims, as well as the victim’s relationship to the primary aggressor. Our results are derived from a cohort of 946 articles published online by New Zealand media outlets. Analysing the number of media articles relating to victims from each group (exposure), the polarity of language used within the articles (sentiment) and their online presence (prominence), we find that although media coverage is generally quite equitable, certain groups of victims are severely under-represented in terms of the media coverage afforded to them. In addition, there are significant differences in the sentiment of articles written about victims from different groups. This study, therefore, identifies an opportunity for raising accurate community understanding of family violence in New Zealand and for supporting victims through objective media coverage.

Introduction

New Zealand’s Ministry of Social Development (Citation2002) provides the following definition of family violence:

Family violence includes child abuse, partner abuse and elder abuse. Common forms of violence in families / whānau include: Spouse / partner abuse (violence among adult partners); Child abuse / neglect (abuse / neglect of children by an adult); Elder abuse / neglect (abuse / neglect of older people aged approximately 65 years and over, by a person with whom they have a relationship of trust).

Family violence has a devastating social and economic impact on people and communities across Aotearoa New Zealand, where nearly half of all homicides and reported violent crimes are family violence related (New Zealand Ministry of Justice Citation2018). With police responding to a family violence incident every four minutes, Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the highest rates of family violence in the developed world and the issue is estimated to cost the country between $4.1bn and $7bn annually (Roy Citation2020).

Described as the ‘new COVID-19 crisis’, countries worldwide have seen a rise in family violence during the recent pandemic (Southall Citation2020; Gupt and Stahl Citation2020; DeMola Citation2020), with incidents surging in epidemic hotspots like China and Italy (Strianese Citation2020; Wanqing Citation2020). Indeed, evidence suggests that the family violence situation in Aotearoa New Zealand, was also exacerbated by the disease, which forced the entire nation into an unprecedented two-month-long lockdown between March and May 2020. During this period, figures revealed a 22% increase in police investigations into domestic abuse, whilst Women’s Refuge reported a 20% increase in calls to its family violence hotline (Foon Citation2020). However, as many in danger would have difficulty reaching out or leaving home due to lockdown restrictions, many experts have expressed concern that the real rise in family violence rates may be much higher than expressed in official figures (Ensor et al. Citation2020; Roy Citation2020). Indeed, that family violence is notoriously under reported in Aotearoa New Zealand is well known (Simon-Kumar Citation2019; Elder Citation2020; Hopgood Citation2020; Radio New Zealand Citation2020; Strang Citation2020). The New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey (New Zealand Ministry of Justice Citation2015) found that around 76% of family violence incidents are not reported to the police, with the subsequent 2018 survey finding that the most common reasons for not officially reporting offences committed by family members were that the victims believed the crime to be a private matter, due to shame or embarrassment or for fear of reprisal.

Mass media is a significant tool in shaping public understanding of key social issues such as family violence and is an effective way to get messaging concerning the subject out to a wide audience (McLaren Citation2010). Thomas and Green (Citation2009) highlight how the media can be a critical ally for those committed to addressing family violence with its coverage both reflecting and shaping public opinion about the matter. By headlining a particular crime, Grabosky and Wilson (Citation1989) argue the media can ensure it becomes a topical and major issue within the country. Thus, many contend that journalists play a critical role in influencing public policy and government interventions regarding family violence (Taylor and Sorenson Citation2002).

However, a variety of studies have shown that the converse can also be true. That is to say that under-coverage of family violence in the media can create an environment that implicitly fosters violence by isolating the victims (Anastasio and Costa Citation2004). As noted by Thomas and Green (Citation2009), lack of media coverage:

allows family violence to remain hidden and can reinforce the control and domination of those who perpetrate such abuse by further isolating their targets as well as by supporting the notion that incidents of family violence are private and rare.

At its worst, media coverage can even serve to fuel family violence and perpetuate the stereotypes that surround it (Evans Citation2001; Carll Citation2003). Anastasio and Costa (Citation2004) found that media coverage of family violence can discreetly reduce sympathy for the victims, strengthen stereotypes and instigate blame for female victims of abuse. Likewise, Thomas and Green (Citation2009) describe that the manner in which some journalists report on the victims of abuse can actually reinforce the victim’s vulnerability to such violence and, in some instances, re-victimize the individuals in question. Analysing media coverage from five Australian newspapers over a 15-week period, the aforementioned study found that reporting varied significantly depending on the ethnicity, gender, age, status and religious affiliation of those involved. As such, the authors concluded that a disproportionately high media profile of family violence associated with specific groups of people can have the effect of blaming specific cultures, thereby encouraging the view that the problems associated with family violence are concentrated somewhere other than in the mainstream communities of the nation.

With the power to shape community perceptions and improve public visibility of the issues, but also the ability to implicitly condone or even fuel aggression, unbiased equitable media coverage is an essential component in the struggle to eradicate family violence in Aotearoa New Zealand. According to guidelines published by one of NZ’s leading family violence support agencies, Are You OK? (2020), media coverage on family violence should be conducted in such a way that the public knows that victims of family violence ‘cross all socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, sexual orientation, educational, age and religious lines’. The purpose of this research is to address how well Aotearoa New Zealand digital media lives up to this standard. In particular, we investigate whether there is any systematic bias in the media coverage of family violence which resulted in death in terms of the gender, age and ethnicity of the victim as well as their relationship to the primary aggressor. More specifically, we investigate whether any of the aforementioned factors have a disproportionate effect on the number of articles written about the victim (exposure), whether these articles are afforded ‘front page’ status (prominence) and the overall sentiment of the articles (sentiment). We concern ourselves only with instances of family violence which resulted in death because variation in coverage levels of family violence which did not result in death by gender (Browning and Dutton Citation1986; Edleson and Brygger Citation1986; Brush Citation1993; Dobash et al. Citation1998) and ethnicity (Pan et al. Citation2006; Engelbrecht Citation2018) make systematic biases in the surrounding media coverage harder to detect. In the broader context, our analysis could not be more timely, with major Aotearoa New Zealand media outlets recently recognizing historical systematic biases in their own reporting (BBC Citation2020; Stuff Citation2020).

Materials and methods

Family violence victim data

The New Zealand Homicide Report (Ensor and Fyers Citation2019) is the first publicly searchable database of homicides in Aotearoa New Zealand and provides an exhaustive list of all victims of homicide within the country since 2004. The objective of the Homicide Report is to provide the public with greater insight into the socio-economic issues surrounding homicides and the factors contributing to their occurrence. The database publishes details of the victim’s full name, gender, date of death, age, cause of death and the relationship of the victim to the primary aggressor, as well as providing an image of the victim in most cases.

In this paper, we are concerned with victims of family violence, which resulted in death only. As such, we refined the database to victims whereby the primary aggressor was defined either as a partner, relation of a partner, parent, child, sibling or extended family member of the victim. In this way, between 2005 and 2018, we identified 329 victims of family violence, which resulted in death. The (primary) ethnicity of each victim was imputed from digital media articles written about the victim (see the section below).

Digital media articles

Wellington-based analytics company DOT Loves Data (DOT) has, to date, collated an archive of approximately 10 million news articles published within publicly available main-stream media platforms. This digital archive, referred to as ‘The Pressroom’, dates back to 2005 and contains comprehensive collections of articles published on Aotearoa New Zealand websites. The Pressroom is used to report on current events and to track trends in both media reporting and social opinion (Bracewell et al. Citation2016; McNamara et al. Citation2018; Bracewell et al. Citation2019; Dissanayake et al. Citation2020; Pappafloratos et al. Citation2020).

Using its proprietary natural language processing tool, ‘The Hound’, DOT extracted from The Pressroom a total of 946 online articles and associated URLs which mentioned exactly one of the aforementioned 329 victims of family violence which resulted in death (articles mentioning two or more of the victims were discounted to prevent any possible conflation of results). This was achieved by using Ethel to explicitly search for the victim’s full name within the text of all Pressroom articles. To ease the subsequent exposition, we refer to the collection of 946 media articles obtained in this manner as the ‘cohort of articles’ or simply as ‘the cohort’.

Prominence of digital media articles

The Wayback Machine (Citation2021) is a digital archive of the world wide web with over 446 billion web pages saved at specific points in time. Using the URL associated with each article within the cohort, DOT used the Wayback Machine (Citation2021) to determine whether the article appeared on the ‘front page’ of the publishing website or whether the reader would have had to click through various sections in order to access the article. In this way, a binary variable was assigned to each article within the cohort; being equal to 1 if the article appeared on the front page of the publishing website and zero otherwise. In total, 296 (31%) of the 946 articles were deemed to have been afforded front-page status.

Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis is a natural language processing technique that quantifies the emotional polarity of text. The technique has spawned a burgeoning field of research in recent years (Ravi and Ravi Citation2015), with applications ranging from analysing the wide-spread mood of the population (Bracewell et al. Citation2016), to quantifying customer satisfaction (Kang and Park Citation2014), to predicting voter behaviour (Agarwal et al. Citation2018). DOT’s proprietary sentiment analyser Ethel (Bracewell et al. Citation2019), converts the free text within articles into a ‘bag of words’. Each sentence within an article is assigned a score in the interval [−1,1], with sentences containing words with highly negative connotations (e.g. awful, horrendous, terrible, etc.) being assigned a score close to minus one and sentences containing words with highly positive connotations (e.g. fantastic, amazing, wonderful, etc.) assigned a score close to plus one. This is achieved using the natural language toolkit within the Python programming language. The initial sentiment score of an article is then calculated as the weighted average of all sentences within the article, with sentences getting a higher weighting the closer they are to the start of the article. Initial sentiment scores are then standardised against a historical benchmark (i.e. the mean and standard deviation of initial sentiment scores for all Pressroom articles) before being converted to a standard normal distribution to derive final article sentiment scores. Hence, the greater the deviation of the final sentiment score from zero, the greater the polarity of the language used within the article.

In the context of the current study, we applied Ethel to each of the 946 articles within the cohort in order to obtain a (final) sentiment score for each article. For further information on the mechanics of sentiment scoring the reader is directed to Pappafloratos et al. (Citation2020) and McNamara et al. (Citation2018).

Data preparation

DOT merged the data described in the previous sections together to create two main data sets. Data Set 1 consisted of a list of all 329 victims of family violence which resulted in death, along with two dependent variables:

The data set also contained four categorical independent variables describing the characteristics of the victim, that is, their Gender (male and female), Ethnicity (Asian, European, Maori, Pasifika), Age (0–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–25, 26–65, 65+) and their Relationship to the primary aggressor (partner, relation of partner, parent, child, sibling, extended family member). In order to ease the subsequent exposition, we refer to the concepts of Gender, Ethnicity, Age and Relationship to the primary aggressor as characteristics and refer to the associated sub-categories as groups.

In contrast, Data Set 2 consisted of a list of all 946 articles from the cohort, the name of the victim the article was written about, the four categorical independent variables describing the characteristics of the victim as listed above and the (final) sentiment score associated with each article. Data Set 2 was used primarily to investigate differences in the distribution of sentiment scores relating to different groups of victim.

Statistical analysis

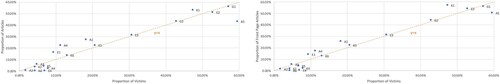

A simple, yet instructive, way to determine whether there is any systematic bias in the level of media exposure (prominence) afforded to victims from different groups is to compare the proportion of victims belonging to that group to the proportion of (front page) articles written about them. The intuition here is that unbiased reporting should result in these proportions being roughly similar, that is, if a particular group accounts for x% of the total number of victims of family violence which resulted in death, then one would expect roughly x% of (front page) articles from our cohort to be devoted to victims from that group. To test whether there were any significant differences between the proportion of victims belonging to each group and the proportion of (front page) articles written about them, we conducted successive exact 1-sided binomial hypothesis tests for population proportions. The results of this process are shown in .

Table 1. Victims of extreme family violence, exposure and prominence by group.

Continuing with the themes of exposure and prominence, DOT used Data Set 1 to construct a generalised linear model to predict the number of (front page) articles written about victims given their specific characteristics. The exact forms of these generalised linear models are specified below:

The nature of the models just described is such that a coefficient will be produced for each individual group within each characteristic. More specifically, the models will produce a coefficient for each gender, each ethnicity, each age group and each class of the victim’s relationship to the primary aggressor.Footnote1 In the current context, we are not as interested in the comparison of the coefficients across characteristics as we are with the relative direction and magnitude of the coefficients applied to groups within the same characteristic. For instance, a larger more positive coefficient applied to males in comparison to females would be suggestive of the fact that male victims of family violence, which resulted in death are likely to have more (front page) articles written about them. In this respect, the coefficients and metrics of fit associated these generalised models are provided in .

Table 2. Modelled regression coefficients and fit statistics.

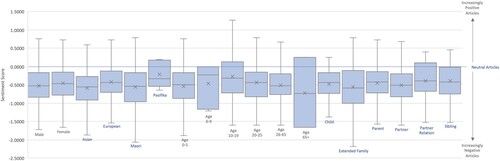

Turning our analysis to the theme of sentiment, DOT wished to examine whether there was any systematic bias in the polarity of language used within media articles relating to different groups of victims of family violence which resulted in death. As a first step in this regard, the mean sentiment score for each group of victims is displayed in , with a visual illustration of the distribution of sentiment scores for each group being presented in .

Table 3. Group sentiment means.

When attempting to determine whether there are significant differences in the means of multiple groups, it is inappropriate simply to conduct successive pairwise t-test due to the problem of multiple testing (Bland and Altman Citation1995). Instead, the correct way to proceed is to conduct a one-way ANOVA test to determine whether there is any evidence against the null hypothesis that all groups share the same mean. If one-way ANOVA reveals a significant result, then one may conduct a post hoc Tukey Multiple Comparison test, which tests for pairwise differences in means amongst groups in such a way that appropriate adjustments are made for multiple testing and the probability of incurring Type I errors (Olleveant et al. Citation1999).

However, one-way ANOVA (and the subsequent post hoc tests) rely upon the assumptions that the response variable is normally distributed for each group under consideration and that all groups have equal variance. Although one-way ANOVA is generally considered to be robust against violations of the normality assumption. If the assumption of homogenous variances is violated, but the normality assumption is not, one replaces the one-way ANOVA test with a Welch test. However, if both assumptions are violated, then one typically applies a Kruskal–Wallis test (which may be thought of as the non-parametric counterpart of one-way ANOVA) to test whether the distributions of the response variable across groups are the same. If the Kruskal–Wallis test reveals significant evidence against the null hypothesis of equivalent distributions, then one then applies Dwass–Steel–Critchlow–Fligner (DSCF) tests to help determine for which pairs of groups the response variable is distributed differently (Hollander et al. Citation2014).

In the current context, although the sentiment scores for each article are drawn from a standard normal distribution (i.e. the sentiment scores for the entirety of The Pressroom library) the sentiment of articles written about each group of victim generally fails a Shapiro–Wilk test. Indeed, since the sentiment of such articles tends to be highly negative, they are not a representative sample of all Pressroom articles. More often than not, the sentiment of articles written about each group also fails a Levene test for homogeneity of variance. As such, to test whether there was any difference in the sentiment of articles written about different groups of victim, DOT first conducted one-way ANOVA tests/Welch tests before conducting post hoc multiple Tukey comparison tests to identify significant differences in the mean sentiment across groups. However, in light of the aforementioned violation of normality and the heterogeneity of group variances, DOT supplemented this by conducting appropriate Kruskal–Wallis tests and post hoc DSCF tests to determine whether there were any differences in the distribution of sentiment scores relating to different groups of victim. The results of this process are shown in .

Table 4. Statistical tests.

Results

shows the proportion of victims of family violence which resulted in death belonging to each group plotted against the proportion of (front page) articles from the cohort written about each group (). The fact that the majority of points are clustered around the line y = x indicates that, in general, there is a good correspondence between the proportion of victims belonging to each group and the proportion of (front page) articles written about them. Indeed, this can be seen by comparing the corresponding columns of .

Figure 1. Scatter plot of the proportion of victims of extreme family violence vs proportion of (front page) articles from the cohort.

However, there are some obvious outliers to this correspondence. With regard to ethnicity, Asian victims of family violence, which resulted in death, are over-represented both in terms of exposure and prominence, whereas Pasifika victims are severely under-represented in both these regards. As demonstrated in , these effects are all significant with p < 0.0000. Furthermore, the over (under) representation of Asian (Pasifika) victims in terms of exposure and prominence is also reflected in the magnitude of the relevant coefficients for Model 1 and Model 2 expressed in . That is to say that the larger coefficients applied to Asian as opposed to Pasifika victims imply that, ceteris paribus, one would expect more (front page) articles to be written about victims from the former group.

With respect to age groups, victims aged 0–5 and 20–25 are strongly over-represented in terms of exposure and prominence, whereas victims aged 26–65 and 65+ were found to be strongly under-represented in these regards. Indeed, of the 14 victims of family violence which resulted in death aged 65+, only three articles from our cohort pertained to these victims, none of which were afforded front-page status. Again, the relevant binomial hypothesis tests were all significant at the p = 0.0008 level, with the coefficients for Model 1 and Model 2 also reflecting the over and under-representation exhibited within these groups.

In terms of the victim’s relationship with the primary aggressor, victims killed by their partner were over-represented in terms of exposure and prominence, whilst victims killed by a child or sibling were under-represented with respect to these metrics. In these instances, the associated binomial hypothesis tests were all significant at the p = 0.04 level with the under and over representation also being reflected (to an extent) within the coefficients associated to Model 1 and Model 2.

Moving to the theme of sentiment, measured by the sentiment scores drawn from a population with mean 0 and standard deviation 1, indicates that the mean sentiment of articles written about Pasifika, European, Maori and Asian victims of family violence which resulted in death become increasingly negative. However, although the associated one-way ANOVA, Welch and Kruskal–Wallis tests all produced significant results (see ), from the subsequent post hoc Tukey tests it is only possible to say that the mean sentiment score of articles written about Asian victims was significantly lower than that for European victims, with the same also being true for Maori victims. These results should be interpreted as saying that, on average, articles written about Asian and Maori victims of family violence which resulted in death use more highly negative language than those written about European victims. Differences in the distribution of sentiment scores of articles relating to these victim groups were also detected in the corresponding DSCF tests.

In contrast to the under representation of victims aged 65+ in terms of exposure and prominence, the mean group sentiment score for victims in this age group was lower than for any other age group. In other words, although a disproportionally small number of (front page) articles were written about victims from this group, the articles that were written tended to employ more negative language than articles written about victims from other age groups. Again, although one-way ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests produced significant results, it is only possible to say that the mean sentiment score for the under 5s group was significantly lower than that for the 10–19 age group and that the same was true for the 25–65 age group. Analogous differences in the distribution of sentiment scores were detected in the corresponding DSCF tests.

No significant differences were detected with regards to the exposure, prominence or sentiment of media articles in terms of gender or the victim’s relationship to the primary aggressor.

Discussion and conclusion

There are several qualifications that should be made with regard to this study. First and foremost, this study does not say anything about whether or not the issue of family violence which resulted in death is given sufficient coverage by mainstream Aotearoa New Zealand media. That is to say that this study only seeks to address whether the coverage afforded to the issue is equitable, that is, whether there are differences in the polarity of language used in relation to victims belonging to different groups and whether the proportion of (front page) articles relating to victims from each group accurately reflects the proportion of victims pertaining to such groups.

Secondly, it should be stressed that differences in the sentiment of articles written about victims belonging to different groups are not necessarily an indication of a favourable or unfavourable bias by the media towards any particular group. Instead, differences in sentiment are only an indication of the fact that there is a difference in the nature of the language used within articles relating to those groups. For instance, the fact that the sentiment of articles written about Asian and Maori victims of family violence which resulted in death is significantly more negative than the sentiment of articles written about European victims does not, on its own, imply an unfavourable bias towards either Asian, Maori or Europeans, but merely indicates that victims from such groups are talked about in different ways within the media.

Thirdly, whilst we have attempted to draw conclusions about media bias by modelling the number of (front page) articles were written about each group using gender, ethnicity, age and primary aggressor relationship as categorical independent variables, it is acknowledged that the fit of these models is weak. In other words, the R2 value obtained when regressing (without intercept) the modelled number of (front page) articles against the actual number of such articles is low (see ). Herein, however, it should be recognised that we are not as interested in the strength of the models as we are with the direction and relative magnitude of the coefficients produced since it is these metrics that enable us to infer media bias.

Finally, with regards to the under or over representation of specific groups in terms of exposure and prominence, we should acknowledge the possibility of a ‘novelty factor’ effect. For example, whilst there is fewer male than female victims of family violence, which resulted in death, there is a slight (statistically insignificant) over representation of male victims in terms of the exposure and prominence of media articles. In this particular instance, the over-representation of male victims in the media may result precisely because there are fewer victims from this group, that is, the associated articles hold a ‘novelty factor’ potentially making them more likely to be read by the general public. Whilst we must concede the possibility of the existence of such novelty factor effects, this would not explain the dearth of (front page) articles written about elderly or Pasifika victims of family violence which resulted in death.

With the above said, there are some notable strengths of our study. In particular, we are the first that we know of (certainly in the Aotearoa New Zealand context) to be able to collate a comprehensive cohort of media articles concerning victims of family violence which resulted in death, thereby allowing the over/under representation of specific groups to be ascertained. We are also the first to be able to statistically analyse the polarity of the language used within articles relating to different groups of victims of family violence which resulted in death. It should be noted that the line-by-line analysis of free text required in this regard is very computationally intensive.

Our study finds that elderly victims (65 years of age and older) of family violence, which resulted in death, are strongly under-represented in terms of the media coverage afforded to them. Indeed, this finding supports an array of other research studies that have reached similar conclusions. For instance, Beard and Payne (Citation2005) found that coverage of elder abuse in the newspapers was far less than the level of prevalence of this crime, whilst Payne et al. (Citation2008) describes how sexual abuse crimes committed against elderly people are almost completely excluded from national news media. The lack of media coverage afforded to elderly victims of family violence which resulted in death is all the more concerning given that as many as three in four cases of elder abuse in Aotearoa New Zealand go unreported (NZ Police Citation2018). With this in mind, it is no wonder that elder abuse has been dubbed the ‘silent problem that affects thousands of elderly Kiwis’ (Trigger Citation2019).

As eluded to above, our study finds that there is a significant difference in the sentiment of the language used within articles written about Maori victims of family violence, which resulted in death in comparison to European victims. Whilst in the context of the current paper, we cannot say that this is an indication of an unfavourable bias within the media toward either of the aforementioned ethnicities, previous studies on related topics have been far more unequivocal. For instance, in analysing a cohort of articles concerning child abuse from three of Aotearoa New Zealand’s largest newspapers, Maydell (Citation2018) found that the dominant construction within these articles was of child abuse as a ‘Maori issue’. This was achieved through individual framing, focused on the personalities of the perpetrators and their inferred innate characteristics (such as being prone to violence and being dysfunctional by nature), which were further generalised to Maori society as a whole. Such criticisms are not unique to Aotearoa New Zealand media. For instance, Smith (Citation2003) and McCallum (Citation2007) both suggest that media coverage of family violence within indigenous communities is often used to depict the entire community as complicit. In particular, McCallum (Citation2007) investigated the media coverage of family violence in indigenous Australian communities and found that such coverage was employed to present aboriginal Australian people as innately backward, characteristically violent and a risk to national social stability.

Whilst our study found that Pasifika victims of family violence which resulted in death were strongly underrepresented in terms of the degree of (front page) media coverage they were afforded, the same could not be said of Maori victims. This latter fact contrasts with the prevailing international literature, which has typically found indigenous populations to be underrepresented in such regards. For instance, in Canada, indigenous female victims of domestic violence have often been described as being largely invisible in mainstream media (Jiwani and Young Citation2006; Gilchrist Citation2010). Similarly, in Hawaii, Chagnon’s (Citation2014) content analysis of femicides found that Hawaiian newspapers tend to dedicate greater media coverage to upper and middle-class victims. Chagnon describes how class indirectly serves a proxy for ethnicity here, given how strongly intertwined class, ethnicity and indigeneity are within colonial communities.

In terms of contextualising our results in the wider literature with regard to gender differences, it has been frequently noted that domestic violence perpetrated against men typically receives less media attention than violence against women or children (Turchik et al. Citation2016; Barber Citation2008; Naffine Citation2002). Despite this, our study found a weak (but statistically insignificant) tendency for male victims of family violence, which resulted in death to be overrepresented in terms of the degree of media coverage afforded to them. No statistically significant gender-specific differences were observed with regards to the sentiment of articles.

Another notable departure of our analysis from the wider extant literature can be seen with regard to the media coverage afforded to victims killed by their own child. That is to say that within this study, we found that victims killed by their own child received a disproportionately low level of media coverage. However, due to its numerical rarity and cultural reprehensibility, such crimes (particularly matricide) tend to generate large amounts public attention and attract substantial media coverage in the international context (Dogan et al. Citation2010; Schug Citation2011; Ohbuchi and Kondo Citation2015; Adinkrah Citation2018).

To conclude this paper, we suggest a few ways in which our research could be extended. First, instead of focusing on victims of family violence which resulted in death, the exact same analysis could be applied to all murder victims within Aotearoa New Zealand. In this regard, the New Zealand Homicide Report (Ensor and Fyers Citation2019) could be used to extract a list of all murder victims over a specified period, whilst a comprehensive cohort of articles about such victims could be extracted from The Pressroom (see above). Applying the exact same analysis as outlined in this paper could then reveal systematic biases in the coverage afforded to victims from different groups and differences in the polarity of language used therein. Next, returning to the question of whether or not the issue of family violence which resulted in death is provided sufficient coverage by Aotearoa New Zealand media, one would posit that this could only be ascertained by means of international comparison. That is to say that DOT could extract from the 10 million articles within Pressroom all articles relating to family violence, which resulted in death, to obtain a measure of the prominence of this topic within Aotearoa New Zealand media. Collaboration within organisations in other countries which have also amassed similar digital archives could then reveal how the proportion of articles on this topic differed from country to country.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of a larger body of work, ‘Data informed decision bias’, a PhD Thesis supported by Callaghan Innovation and DOT loves data. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Tamsyn Hilder, Lead Data Scientist – Product at Dot Loves Data, for her invaluable contribution in accessing the outputs from The Hound, Ethel and The Pressroom.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Within the SAS programming language, it is convention that the group that is last alphabetically within each characteristic is assigned a coefficient equal to zero. The coefficients applied to all other groups in the same characteristic are expressed relative to this benchmark.

References

- Adinkrah M. 2018. Matricide in Ghana: victims, offenders, and offense characteristics. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 62(7):1925–1946. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X17706891.

- Agarwal A, Singh R, Toshniwal D. 2018. Geospatial sentiment analysis using twitter data for UK-EU referendum. Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences. 39(1):303–317.

- Anastasio P, Costa D. 2004. Twice hurt: how newspaper coverage may reduce empathy and engender blame for female victims of crime. Sex Roles. 51(9):535–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-5463-7.

- Barber CF. 2008. Domestic violence against men. Nursing Standard. 22(51):35–39.

- BBC. 2020. News Zealand’s Stuff news group apologises for anti-Maori bias. [accessed 2021 April 6]. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55169004.

- Beard H, Payne BK. 2005. The portrayal of elder abuse in the national media. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 29:269–284.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. 1995. Statistics notes: multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ. 310(6973):170.

- Bracewell PJ, Hilder TA, Birch F. 2019. Player ratings and online reputation in super rugby. Journal of Sports and Human Performance. 7:2.

- Bracewell PJ, McNamara TS, Moore WE. 2016. How rugby moved the mood of New Zealand. Journal of Sport and Human Performance. 4(4):1–9.

- Browning J, Dutton D. 1986. Assessment of wife assault with the conflict tactics scale: using couple data to quantify the differential reporting effect. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 48:375–379.

- Brush LD. 1993. Violent acts and injurious outcomes in married couples: methodological issues in the national survey of families and households. In: P. B. Bart, editor. Violence against women: the bloody footprints. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; p. 240–251.

- Carll E. 2003. News portrayal of violence and women: implications for public policy. American Behavioral Scientist. 46(12):1601–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764203254616.

- Chagnon N. 2014. Heinous crime or acceptable violence? The disparate framing of femicides in Hawai’i. Radical Criminology, 3. http://journal.radicalcriminology.org/index.php/rc/article/view/16.

- DeMola P. 2020. As residents stay home for COVID-19, Schenectady, Amsterdam departments see domestic violence call spike. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://dailygazette.com/article/2020/03/28/agencies-brace-for-spike-in-domestic-violence.

- Dissanayake H, Bracewell PJ, Campbell E, Trowland HE. 2020. Latent drivers of player retention in junior rugby. In: Ray Stefani, Anthony Bedford, editor. Proceedings of the 15th Australian Conference on Mathematics and Computers in sports. Sunshine Coast: ANZIAM Mathsport; p. 92–97.

- Dobash RP, Dobash RE, Cavanagh K, Lewis R. 1998. Separate and intersecting realities: a comparison of men’s and women’s accounts of violence against women. Violence Against Women. 4:382–414.

- Dogan K, Demirci S, Deniz I, Erkol Z. 2010. Decapitation and dismemberment of the corpse: a matricide case. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 55(2):542–545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01266.x.

- Edleson J, Brygger M. 1986. Gender differences in reporting of battering incidences. Family Relations. 35:377–382.

- Elder R. 2020. Sexual assault survivor on why women don’t always speak up. [accessed 2021 April 6]. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/on-the-inside/410240/sexual-assault-survivor-on-why-women-don-t-always-speak-up.

- Engelbrecht C. 2018. Fewer immigrants are reporting domestic abuse. police blame fear of deportation. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/us/immigrants-houston-domestic-violence.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- Ensor B, Fyers A. 2019. The homicide report – the data. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://interactives.stuff.co.nz/the-homicide-report/data.html.

- Ensor B, Gay E, Hurley B. 2020. Coronavirus: death of Auckland baby sheds light on unreported violence during Covid-19 lockdown. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/300019000/coronavirus-death-of-auckland-baby-sheds-light-on-unreported-violence-during-covid19-lockdown.

- Evans I. 2001. ‘We live under a government of men and morning newspapers’: Some findings in the representation of domestic violence in the press’, Domestic Violence and Incest Resource Centre, Newsletter, Spring: 3-7.

- Foon E. 2020. Domestic violence calls to police increase in lockdown. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/415553/domestic-violence-calls-to-police-increase-in-lockdown.

- Gilchrist K. 2010. “Newsworthy” victims? Feminist Media Studies. 10:373–390.

- Grabosky P, Wilson P. 1989. Journalism and justice: How crime is reported. Sydney: Pluto press.

- Gupt AH, Stahl A. 2020. For abused women, a pandemic lockdown holds dangers of its own. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/us/coronavirus-lockdown-domestic-violence.html.

- Hollander M, Wolfe DA, Chicken E. 2014. Nonparametric statistical methods, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Hopgood SJ. 2020. Pacific family violence workers mobilised during NZ’s lockdown. [accessed 2021 April 6]. https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/415568/pacific-family-violence-workers-mobilised-during-nz-s-lockdown.

- Jiwani Y, Young ML. 2006. Missing and murdered women: reproducing marginality in news discourse. Canadian Journal of Communication. 31:895–917.

- Kang D, Park Y. 2014. Review-based measurement of customer satisfaction in mobile service: sentiment analysis and VIKOR approach. Expert Systems with Applications. 41(4):1041–1050.

- Maydell E. 2018. ‘It just seemed like your normal domestic violence’: ethnic stereotypes in print media coverage of child abuse in New Zealand. Media, Culture & Society. 40(5):707–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717737610.

- McCallum K. 2007. Indigenous violence as a ‘mediated public crisis. In: J. Tebbutt, editor. Communications, civics, industry. Australian and New Zealand Communications Association (ANZCA); p. 1–15. http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/31914/20110708-1127/www.anzca.net/download-document/169-indigenous-violence-as-a-mediated-public-crisis.pdf.

- McLaren F. 2010. Attitudes, values and beliefs about violence within families 2008 survey findings. [accessed 2021 April 3]. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/campaign-action-violence-research/attitudes-values-and-beliefs-about-violence-within-families.pdf.

- McNamara TS, Hilder T, Campbell EC, Bracewell PJ. 2018. Gender bias and the New Zealand media’s reporting of elite athletes. In: Ray Stefani, Anthony Bedford, editor. Proceedings of the 14th Australian Conference on mathematics and computers in sports. Sunshine Coast: ANZIAM Mathsport; p. 84–88.

- Naffine N. 2002. Gender and justice. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.

- New Zealand Ministry of Justice. 2015. New Zealand Crime and Safety Survey: 2014. [accessed on 2021 April 6]. https://www.justice.govt.nz/justice-sector-policy/research-data/nzcass/.

- New Zealand Ministry of Justice. 2018. New Zealand Crime & Victims Survey: 2018. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.justice.govt.nz/justice-sector-policy/research-data/nzcvs/resources-and-results/.

- New Zealand Ministry of Social Development. 2002. Te Rito New Zealand family violence prevention strategy. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/planning-strategy/te-rito/te-rito.pdf.

- New Zealand Police. 2018. Speak out and prevent elder abuse. [accessed 2021 March 18]. https://www.police.govt.nz/news/ten-one-magazine/speak-out-and-prevent-elder-abuse.

- Ohbuchi K, Kondo H. 2015. Psychological analysis of serious juvenile violence in Japan. Asian Journal of Criminology. 10(2):149–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-014-9199-1.

- Olleveant NA, Humphris G, Roe B. 1999. How big is a drop? A volumetric assay of essential oils. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 8(3):299–304.

- Pan A, Daley S, Rivera LM, et al. 2006. Understanding the role of culture in domestic violence: The ahimsa project for safe families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 8:35–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-006-6340-y.

- Pappafloratos TH, Hilder TA, Bracewell PJ. 2020. Societal bias and the discourse on top tennis players in New Zealand sport media. Ray Stefani & Anthony Bedford eds: 15th ANZIAM Mathsport. pp.114–12.

- Payne BK, Appel J, Kim-Appel D. 2008. Elder abuse coverage in newspapers: regional differences and its comparison to child-abuse coverage. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect. 20(3):265–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08946560801973135.

- Radio New Zealand. 2020. Crime survey shows Kaupapa Māori services need more resources, staff – advocate. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/417106/crime-survey-shows-kaupapa-maori-services-need-more-resources-staff-advocate.

- Ravi K, Ravi V. 2015. A survey on opinion mining and sentiment analysis: tasks, approaches and applications. Knowledge-Based Systems. 89:14–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2015.06.015.

- Roy EA. 2020. New Zealand domestic violence services to get $200 m as lockdown takes toll [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/11/new-zealand-domestic-violence-services-to-get-200m-as-lockdown-takes-toll.

- Schug R. 2011. Schizophrenia and matricide: an integrative review. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 27(2):204–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986211405894.

- Simon-Kumar R. 2019. Ethnic perspectives on family violence in Aotearoa, New Zealand. [accessed 2021 April 1]. https://nzfvc.org.nz/sites/default/files/NZFVC-issues-paper-14-ethnic-perspectives.pdf.

- Smith A. 2003. Not an Indian tradition: the sexual colonization of native peoples. Hypatia. 18(2):70–85.

- Southall A. 2020. Why a drop in domestic violence reports might not be a good sign. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/nyregion/new-york-city-domestic-violence-coronavirus.html.

- Strang B. 2020. Ninety-four percent of sexual assaults go unreported-survey. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/417046/ninety-four-percent-of-sexual-assaults-go-unreported-survey#:~:text=One%20in%20four%20people%20experience,crime%20in%20New%20Zealand%20shows.

- Strianese R. 2020. Forced coexistence is an alarm for violence against women. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.ottopagine.it/av/attualita/211981/convivenza-forzata-e-allarme-per-la-violenza-sulle-donne.shtml?fbclid=IwAR2co5gCL-ap_komk92okzct2VR4eOonV3MDb53Jk9fU8WVUQ1pw5jNxPgU.

- Stuff. 2020. Our truth, Tā Mātou Pono: Stuff introduces new treaty of Waitangi based charter following historic apology. [accessed 2021 March 5]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/pou-tiaki/our-truth/123533668/our-truth-t-mtou-pono-stuff-introduces-new-treaty-of-waitangi-based-charter-following-historic-apology.

- Taylor CA, Sorenson SB. 2002. The nature of newspaper coverage of homicide. Injury Prevention. 8:121–127.

- Thomas VL, Green R. 2009. Family violence reporting: supporting the vulnerable or re-enforcing their vulnerability? Asia Pacific Media Educator. 19(2009):55–70.

- Trigger S. 2019. Elder abuse 'rampant' and 'all-hidden' in New Zealand. [accessed 2021 May 4]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/113353630/elder-abuse-rampant-and-allhidden-in-new-zealand.

- Turchik JA, Hebenstreit CL, Judson SS. 2016. An examination of the gender inclusiveness of current theories of sexual violence in adulthood: Recognizing male victims, female perpetrators, and same-sex violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 17(2):133–148.

- Wanqing Z. 2020. Domestic violence cases surge during COVID-19 epidemic. [accessed 2021 April 8]. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1005253/domestic-violence-cases-surge-during-covid-19-epidemic.

- Wayback Machine. 2021. [accessed 2020 July 3]. https://web.archive.org/.