ABSTRACT

To be realistic and meaningful, positive ageing conceptualisations should involve a diverse range of perspectives. Yet, problematically, perspectives are often distinguished as ‘researcher versus older adult’. In this scoping review, we suggest that distinguishing perspectives based on the data collection and interpretation approach is more meaningful. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework, we explored diverse positive ageing literature (from across conceptual origins and discourses) to clarify how positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults has been conceptualised. To reflect diverse data and interpretation perspectives, we considered both etic (closed/validatory) and emic (open/exploratory) approaches and developed a conceptual model of positive ageing that consolidated diverse literature and approaches. We synthesised 75 articles and determined that etic and emic approaches generally included similar features; however, emic approaches considered more comprehensive and complex features. Our multidimensional and holistic positive ageing model illustrates the range of unique factors which contribute to the health and well-being of older adults. Furthermore, we find that positive ageing literature largely focuses on individualistic behaviours. Future positive ageing research and policy would have more traction, in our view, if it included wider structural environments to stimulate real-world change. We offer our conceptual model as a useful guide.

Introduction

Positive dialogue around older age has spurred the development of various discourses of ageing, for example productive (Butler and Gleason Citation1985), successful (Rowe and Kahn Citation1987, Citation1997), active (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2002), positive (Ministry of Social Policy Citation2001), and healthy (WHO, Citation2015) ageing. Despite having distinct conceptual origins and contextual differences (cultural, social, political, and temporal) (see summaries in Bülow and Söderqvist Citation2014; Holmes Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010), these discourses similarly position ageing as a process and fundamentally seek to optimise older adults’ health and well-being. Recent systematic reviews highlight similarities in variables and concepts across the literature which draw from these discourses (Cosco et al. Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010), yet call for consensus in terminology, definition, and assessment (Cosco et al. Citation2014). Based on the premise that these discourses contain similar and complementary concepts, we adopted the all-encompassing umbrella term, or label, of positive ageing throughout this scoping review to represent these related concepts. While we recognise there is no perfect umbrella term to use, we have selected positive ageing because of the historic conceptual relevance to the authors’ local context (New Zealand) (Davey and Glasgow Citation2006; Ministry of Social Policy Citation2001). Positive ageing is an evolving, inclusive, and multidimensional concept, guided by the premise that older age should be viewed and experienced positively (Davey and Glasgow Citation2006; Ministry of Social Policy Citation2001; The Office for Seniors Citation2019). Furthermore, positive ageing avoids some of the more robust criticisms that successful or active ageing discourses have received (Dizon et al. Citation2020; Martinson and Berridge Citation2015; Rubinstein and de Medeiros Citation2015).

The concept of positive ageing (and associated synonyms) has a long history within research and policy spaces (Holmes Citation2006; e.g. Bülow and Söderqvist Citation2014; WHO, Citation2015), fuelled in-part by the growing older adult population (United Nations Citation2019). Policy initiatives to support ageing in the community (commonly termed ageing in place) have concurrently arisen, often reflecting older adults’ own desires to remain living in familiar homes and communities as they age (Lewis and Buffel Citation2020). Several systematic reviews have attempted to summarise the vast positive ageing literature but have not explicitly focused on community-dwelling older adults (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010; Peel et al. Citation2004; Phelan and Larson Citation2002). These systematic reviews have identified that components (i.e. individual variables/concepts) of positive ageing span multiple dimensions, including physiological, social, and psychosocial dimensions. However, the heterogeneous nature of positive ageing research has also been highlighted; particularly around inconsistencies in positive ageing definitions and assessment. Ultimately, such inconsistencies contribute to considerable variation in prevalence estimates of positive ageing (Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Peel et al. Citation2004) and limit the advancement of positive ageing research (Cosco et al., Citation2014).

A common critique of previous positive ageing literature and policy, particularly documents drawing from successful or active ageing discourses, is the positioning of older adults as individually responsible for engaging in ‘good health’ practices (Dizon et al. Citation2020; Rubinstein and de Medeiros Citation2015; Martinson and Berridge Citation2015). Additional critiques of this literature include the absence of older adults’ perspectives and lack of consideration of wider social, economic, cultural, and environmental contexts (Martinson and Berridge Citation2015). Policymakers have begun an important shift towards acknowledging the significance and influence of environmental supports on positive ageing, although this shift is not universal (Dizon et al. Citation2020). For example, the WHO policy framework for healthy ageing emphasises the overarching importance of supportive environments (including health systems, service provision, housing, transport, safety) and their interactions with wellbeing in older age (Beard et al. Citation2016; WHO, Citation2015). In the case of New Zealand, the recent Better Later Life – He Oranga Kaumātua strategy (2019) includes a specific focus on access to health, social, and culturally appropriate services; housing; and accessible community and transport environments. These fundamental shifts in focus look beyond the micro-level (i.e. individual interactions in various settings) to consider environmental resources to enhance positive ageing. These include environmental resources which operate at the wider meso-level (interrelations among various settings) and macro-level (overarching institution, including cultural beliefs and political systems) (Bronfenbrenner Citation1977). While the policy context illustrates that positive ageing is a meaningful term with practical implications, policy remains informed by research. Thus, it is also important to look at how positive ageing has been conceptualised by researchers.

In research, distinctions have been made between researcher-led versus lay or older adult-led conceptualisations of positive ageing (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Hung et al. Citation2010). Specifically, older adult conceptualisations tend to include more diverse components (e.g. psychosocial, spirituality, personal growth, positive outlook), compared to researchers’ more narrow conceptualisations, which often reflect dominant biomedical narratives (e.g. maintenance of physical function, absence of disease) (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013; Hung et al. Citation2010). This researcher-older adult distinction is useful in understanding and critiquing policy, by bringing awareness to how the ideal of ‘achieving’ positive ageing is propagated and how older adults have been framed or engaged in research that informs policy (and also in making policy itself) (Dizon et al. Citation2020; Ranzijn Citation2010). However, we argue that simply distinguishing perspectives as ‘researcher versus older adult’ is problematic for several reasons. First, ‘researchers’ are a diverse group which can comprise older adults as researchers, co-researchers, and experts on ageing. Researcher and older adult perspectives are at times interwoven and can be challenging to separate into discrete categories. Second, older adult conceptualisations are predominantly filtered and interpreted through the researcher’s own worldview (Fetterman Citation2012) and this interpretation can differ across disciplines and methodologies (Markee Citation2012). We suggest that distinguishing perspectives based on the approach to data collection and interpretation is perhaps more meaningful, as this distinction better reflects the methodological and theoretical decisions made, and the subsequent prioritisation of voices throughout the research process. Such a distinction can be based on the concepts of etic and emic.

Etic perspectives draw from researchers’ conceptualisations of existing theories, whereas emic perspectives begin with participants’ voices, own life-worlds, and concepts (Fetterman Citation2012; Maxwell and Chmiel Citation2014). In research under the positive ageing umbrella, etic perspectives often include data collection and interpretation methods that are closed or validatory of existing theories and universalised (sometimes decontextualised) tools (Fetterman Citation2012; Maxwell and Chmiel Citation2014). Etic approaches typically occur in research conducted on or about older adults and tend to generate more narrowly-focused definitions of positive ageing, frequently involving physiological components (Cosco et al. Citation2014). In contrast, emic perspectives relate to data collection and interpretation methods which tend to be more open and exploratory and often begin by working with the voices of older adults. Emic research often starts from exploring an ‘insider’ position, where the particulars of culturally and historically bound human behaviour and understanding are sought (Fetterman Citation2012). Such research conducted with older adults characteristically includes more diversity and complexity when defining positive ageing (Cosco et al. Citation2013; Hung et al. Citation2010). Emic research may begin by working with older adults’ voices, but the choice of methodology, theoretical framework, and degree of rigour, including the level of transparency over research decisions, all potentially impact the quality of inclusion of older adults’ voices. Moreover, the distinction between etic and emic is not entirely clear-cut. As Fetterman (Citation2012) points out, even in emic research, etic views are often adopted later in the research process as interpretive explanatory tools in a kind of ‘stepping back’ process. Thus, the etic-emic distinction can be based on which perspectives the data collection and interpretation procedures prioritise – the use of existing tools or theories to frame and interpret research (etic) or using older adults’ voices as the starting point for analysis and interpretation (emic).

The etic-emic distinction matters because policy documents tend to rely on more etic definitions of positive ageing as the prevailing source of ‘truth’ or evidence, risking a restriction of knowledge (and subsequent policy and practice) to more etic understandings (Dizon et al. Citation2020; Ranzijn Citation2010). Even with the movement towards acknowledging the environmental impacts on positive ageing, reliance on etic understandings prevails (Dizon et al. Citation2020). Ultimately, research informs policy and policy influences the support mechanisms a government provides for community-dwelling older adults. To frame positive ageing in a realistic and meaningful way, it is imperative that researchers and policymakers consider the substantial heterogeneity in positive ageing definitions and incorporate a diverse range of data and interpretation perspectives, including those of older adults and their supporters.

Scoping reviews are a relatively recent addition to knowledge synthesis methodologies and differ from systematic reviews. Both systematic and scoping reviews require rigorous and transparent methods to ensure trustworthiness; however, scoping reviews address exploratory research questions and have more expansive inclusion criteria than systematic reviews (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Munn et al. Citation2018). Scoping reviews are useful for a range of purposes, including for identifying the types and characteristics of available evidence; examining how research has been conducted; and clarifying key concepts within the evidence-base (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Munn et al. Citation2018). Thus, we conducted a systematic scoping review of diverse positive ageing literature (from across conceptual origins and discourses) to clarify how positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults (defined as ≥65 years for this international sample of articles) has been conceptualised in extant literature. As part of this process, we consolidated diverse positive ageing literature and identified various characteristics and methods used within the available evidence.

Guided by findings of Hung et al. (Citation2010), we expected to see substantial differences according to the data and interpretation perspective used to conceptualise positive ageing. To explore the distinction and similarities between etic (closed/validatory) and emic (open/exploratory) approaches to conceptualising positive ageing, we constructed our scoping review around an etic-emic synergy. Ultimately, we developed a realistic and meaningful conceptual model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults by consolidating diverse literature and approaches to data collection and interpretation.

Methods

We were guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five-stage scoping review framework and enhancements by Levac et al. (Citation2010) and Daudt et al. (Citation2013). To ensure methodological and reporting quality, we employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; supplementary material 1) (Tricco et al. Citation2018). Our review protocol was prospectively registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/d7v46/). As scoping reviews are iterative (Arksey and O'Malley Citation2005), protocol deviations were occasionally necessary to balance comprehensiveness and feasibility, as noted below.

Stage one: develop the research question

We addressed the following research question (clarified over the course of the review): How is ‘positive ageing’ for community-dwelling older adults conceptualised in published, peer-reviewed, empirical literature?

Stage two: identify relevant articles

A feasible and replicable search scope was maintained by considering published peer-reviewed empirical articles, of any study type and publication date, that were available in the English-language. Our search strategy comprised terms based on the population (i.e. adults ≥65 years), concept (positive ageing [umbrella term] conceptualisations), and context (community-dwelling) of interest (; supplementary material 2). Individual search terms were informed by keywords located in an initial search of CINAHL Plus and Medline, research team expertise, and seven relevant systematic reviews (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010; Peel et al. Citation2004; Phelan and Larson Citation2002). Based on the search terms used in the seven relevant reviews, our all-encompassing umbrella term of positive ageing incorporated the following related terms and concepts: active ageing, effective ageing, healthy ageing, optimal ageing, positive ageing, productive ageing, robust ageing, successful ageing, usual ageing, and ageing well. As these discourses similarly seek to optimise older adults’ health and well-being, the combination of these terms/concepts enabled a broader and multidimensional picture of positive ageing to be established. Test searches established search term sensitivity and specificity.

Table 1. Description of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Our search strategy was adapted for the nuances of six databases which spanned medicine, health science, allied health, science, and psychology: CINAHL Plus, Embase, Web of Science Core Collection, Medline, Scopus, and PsycINFO (supplementary material 2). All searches were completed on 30 July 2019 by TP. Manual bibliographic scans of articles included in the seven aforementioned systematic reviews complemented our search (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010; Peel et al. Citation2004; Phelan and Larson Citation2002). Results from database searches were imported into EndNote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates removed. Articles identified from relevant systematic reviews were transferred into a Microsoft Excel file and duplicates were removed.

Stage three: article selection

We screened all identified articles using the inclusion criteria outlined in . We first completed combined title and abstract screening, followed by full text screening of all potentially relevant articles. Our first iteration of full text screening captured many articles of little relevance to the review question (n = 184 articles originally included). We revised our inclusion criteria to include a ‘focus on positive ageing [umbrella term]’ () and reviewed the full texts a second time. To facilitate our full text screening, we followed a stepwise approach; we first identified whether participants were community-dwelling, followed by whether participants were ≥65 years of age, and then whether the article focused on positive ageing. TP completed all screening (title/abstract, full text), and DR independently screened a random 10% selection of articles at each stage. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Full text of articles meeting our inclusion criteria were imported into NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International Pty Ltd).

Stage four: data charting

Data charting focused on how authors assessed, developed, or explored positive ageing. Data charting is iterative (Levac et al. Citation2010), hence our data charting form was refined to reflect changes in our review question and inclusion criteria. We extracted and charted relevant data using NVivo 12. Codes were created to reflect:

Study characteristics: Positive ageing assessment methods, methodology, theoretical/conceptual framework, larger study details (if secondary data were reported)

Participant characteristics: Number, age, sex, ethnicity, geographic location of study

Positive ageing conceptualisations: Terminology used, etic perspectives (closed/validatory methods and interpretation, generally involving assessment tools and variables), emic perspectives (open/exploratory methods and interpretation, generally involving participant conceptualisations)

TP charted each article, while DR independently completed charting on a random 10% sample of articles. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Charting of etic perspectives focused solely on author descriptions of positive ageing assessment variables, while charting of emic perspectives involved subjective assessment of the relevance of the participant conceptualisation to our review question. For example, we excluded negative aspects of ageing present in participant conceptualisations (e.g. negative implications of home on loneliness and depression (Sixsmith et al. Citation2014)).

To increase the utility of our results for future practice (Daudt et al. Citation2013), article quality was assessed. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al. Citation2018) was considered appropriate given the heterogeneity in study designs considered. MMAT assesses methodological quality across different study designs through responses to five unique criteria. Methodological quality scores were not used to exclude articles, rather these results informed our interpretations and discussions of findings. TP completed MMAT screening, while MS independently assessed a random 10% sample of articles. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Stage five: collating, summarising, and reporting results

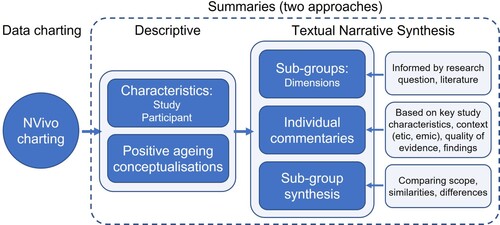

Using the Framework Matrix option in NVivo, all charted data were summarised and exported to Microsoft Excel. At protocol stage, we planned for descriptive and thematic summaries; however, thematic summaries were deemed inappropriate for comparison across study designs. Our revised approach to reporting results involved a two-step process of descriptive summaries and Textual Narrative Synthesis (TNS) (Lucas et al. Citation2007), as shown in .

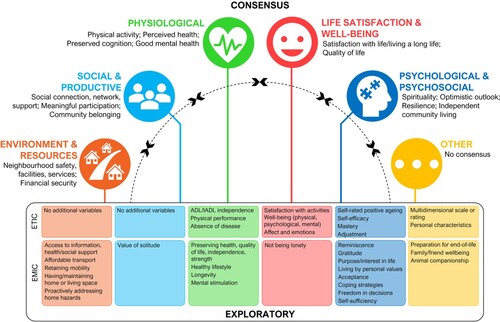

First, descriptive summaries were based on study and participant characteristics and positive ageing conceptualisations. Only relevant participant characteristics (e.g. older adults ≥65 years, community-dwelling) from articles stratifying by age or setting were reported. When multiple articles stemmed from a larger representative project and used the same assessment of positive ageing, the earliest publication was retained (n = 2 articles excluded). A priori, six broad dimensions (Physiological; Life Satisfaction and Well-Being; Social and Productive; Psychological and Psychosocial; Environment and Resources; Other) and a series of 21 narrower components were developed from findings of the seven relevant reviews (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010; Peel et al. Citation2004; Phelan and Larson Citation2002) (). From this, we created a master list of dimensions, components, and examples. All charted data on positive ageing conceptualisations (i.e. assessment variables and participant conceptualisations) were categorised into one or more of the most relevant components across six dimensions. The master list was constantly reflected on to ensure categorisation remained consistent.

Table 2. Six a priori dimensions of positive ageing and related components developed from findings of seven relevant reviews.

Step two involved TNS which is well-suited to identifying a body of knowledge and exploring scope, similarities, and differences across study designs and contexts (Lucas et al. Citation2007). TNS involves three steps: (1) creation of sub-groups (the unit-of-analysis); (2) production of individual article commentaries; and (3) sub-group synthesis comparing scope, similarities, and differences across articles (Lucas et al. Citation2007) (). We defined six sub-groups based on the six a priori identified dimensions (Physiological; Life Satisfaction and Well-Being; Social and Productive; Psychological and Psychosocial; Environment and Resources; Other). Lucas et al. (Citation2007) note that the process of pre-defining sub-groups means transparency becomes an issue. However, by grounding our sub-groups in the findings of relevant reviews (Bowling Citation2007; Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Hung et al. Citation2010; Peel et al. Citation2004; Phelan and Larson Citation2002), we attempted to mitigate this concern. Next, we identified articles belonging to each sub-group (overlap between sub-groups is possible) and produced individual commentaries based on key aspects of the articles (Supplementary table 1). Finally, we produced a sub-group synthesis comparing article scope, similarities, and differences. We separately considered etic and emic perspectives in our sub-group synthesis.

Results

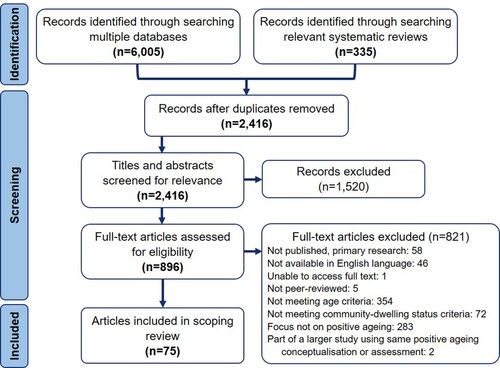

We describe identification, screening, and reasons for exclusion in . Ultimately, 75 published peer-reviewed empirical articles met all inclusion criteria. Study and participant characteristics and positive ageing conceptualisations are summarised in Supplementary table 1.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow chart: Identification, screening, and exclusion of articles (adapted from Tricco et al. (Citation2018))

Descriptive summary: study and participant characteristics

Of the 75 included articles, 65 were quantitative and 10 were qualitative (Supplementary table 1). Questionnaires and surveys were the most common data collection method, used either individually (n = 30) or in combination with another method (n = 15) (e.g. alongside geriatric assessment (García-Lara et al. Citation2017)). Interviews were also frequently used, either individually (n = 16) (e.g. life-story interviews (Nosraty et al. Citation2015), semi-structured interviews (Nguyen et al. Citation2019)) or with additional data collection methods (n = 14) (e.g. computer-assisted interviews, questionnaire, nurse visit (Rodriguez-Laso et al. Citation2018)).

Methodology was explicit in five articles and involved grounded theory (Chen et al. Citation2020; Sixsmith et al. Citation2014), community-based participatory research (Bacsu et al. Citation2014), fundamental qualitative description (Carr and Weir Citation2017), and narrative inquiry (Tate et al. Citation2013). Theoretical frameworks were explicitly mentioned across six articles and spanned environmental gerontology and life-span psychology (Vogt et al. Citation2015), productive engagement (Wang et al. Citation2019), successful ageing theories (Reker Citation2001; Troutman et al. Citation2011), and active ageing models (Bélanger et al. Citation2017; Willie-Tyndale et al. Citation2016).

Fifty-eight articles included participants and/or positive ageing assessment methods from a larger representative project, while nine projects were drawn from two or more times (e.g. Americans’ Changing Lives Survey (Garfein and Herzog Citation1995; Kahng Citation2008) and Omnibus Survey in Britain (Bowling Citation2006, Citation2008; Bowling and Iliffe Citation2006)). Methodological quality ranged from low to high across articles (composite MMAT score range of 2–5, with 5 being the highest). Quantitative descriptive and non-randomised study scores were generally reduced due to inadequate sample/participant representativeness (Supplementary table 1, detailed scores in Supplementary material 3).

All included articles explored positive ageing with participants ≥65 years of age. Sample sizes ranged from 15 (Sato-Komata et al. Citation2015) to 21,493 (Hank Citation2011), and 24 articles included a statement on participant ethnicity. The majority of articles were from countries within North America (n = 34), followed by Asia (n = 19), Europe (n = 17), Oceania (n = 3), Africa, and South America (both n = 1).

Descriptive summary: positive ageing conceptualisations

Articles frequently incorporated etic (closed/validatory) conceptualisations of positive ageing (n = 59) to determine positive ageing prevalence (e.g. Li et al. Citation2006; Rodriguez-Laso et al. Citation2018), predictors (e.g. Curcio et al. Citation2018; Lee Citation2009; White et al. Citation2015), and correlates (e.g. Choi et al. Citation2017; Feng et al. Citation2015; García-Lara et al. Citation2017). Emic (open/exploratory) perspectives were less explored (n = 12) and often involved participant conceptualisations developed qualitatively (e.g. Bacsu et al. Citation2014; Sixsmith et al. Citation2014) or through open-ended responses to questions (Tate et al. Citation2013; Troutman et al. Citation2011). Four articles included multiple conceptualisations of positive ageing integrating etic and emic perspectives (Bowling Citation2006, Citation2008; Hsu Citation2007; Lee Citation2009). Successful ageing terminology was favoured among included articles (n = 61).

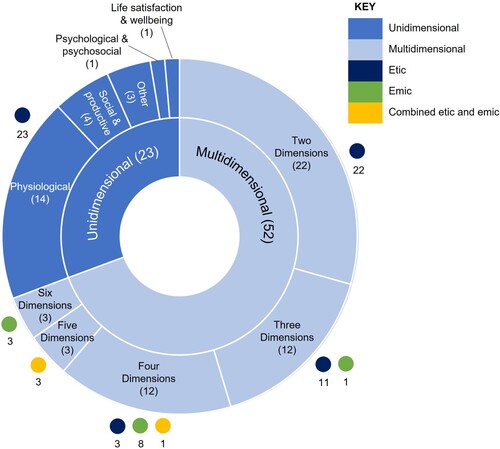

The combination of etic (validatory assessment variables) and emic (exploratory participant conceptualisations) approaches to conceptualising positive ageing are summarised in Supplementary table 1. Supplementary table 1 also details the use of multiple positive ageing assessments across etic perspectives (n = 24 articles; maximum assessments stated = 5 (Bowling and Iliffe Citation2006)). Each individual variable/concept was classified into one or more components across the six a priori dimensions. Full descriptions of individual assessment variables (i.e. specific criteria, tools, thresholds) and concepts within positive ageing conceptualisations are presented in Supplementary materials 4 and 5, respectively, and should be consulted alongside Supplementary table 1. Articles most frequently included components within the Physiological (n = 63 articles) dimension, followed by Social and Productive (n = 43), Psychological and Psychosocial (n = 28), Life Satisfaction and Well-being (n = 22), and Environment and Resources dimensions (n = 14). Fourteen articles included variables/concepts classified as ‘Other’ (Supplementary table 1).

Twenty-three articles were unidimensional in nature and 52 were multidimensional (included components from two or more dimensions) (). Unidimensional articles were predominantly grounded in the Physiological dimension (14/23 articles). Multidimensional articles generally incorporated two, three, or four dimensions (46/52 articles); three articles included components across all six dimensions (Chen et al. Citation2020; Nosraty et al. Citation2015; Tate et al. Citation2013). Unidimensional and two-dimensional articles drew solely from etic perspectives, while all those drawing from emic perspectives incorporated three or more dimensions. No articles from an etic perspective included greater than four dimensions ().

Textual Narrative Synthesis (TNS)

Sub-group synthesis at the dimension-level considered all components () and compared scope, similarities, and differences across etic and emic perspectives. The relative proportion of etic/emic focus across each a priori dimension is reported at the bottom of Supplementary table 1, while the proportion of etic/emic articles contributing to each dimension are presented in text below. Individual references can be accessed in Supplementary materials 4 and 5.

Physiological

Etic perspectives (75%) contributed to five of seven components (excluding General health and Longevity), while emic perspectives (25%) contributed to all. In general, etic perspectives lacked consensus in tools and thresholds used to determine positive ageing, and emic perspectives considered the wider impacts of physiology. Physical Function presented a single etic-emic similarity in physical activity engagement. Etic perspectives predominantly considered independence in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) when determining positive ageing, followed by objective (e.g. sit-to-stand) and subjective (e.g. self-reported ability) assessment of physical performance. The tools and thresholds used to determine independence in ADL, IADL, and physical performance ability varied considerably across articles. Emic perspectives of Physical Function largely focused on how independence in daily activities could be maintained through preserving sufficient bodily resources, mobility, and health (a corollary of physical activity). Emic perspectives also considered preservation of physical health, function, and strength as crucial (although not always possible) for positive ageing.

Etic perspectives considered absence of physical Disease, chronic health conditions (most commonly cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer, diabetes, arthritis), and cardiovascular risk factors as essential for understanding positive ageing. In contrast, emic perspectives stressed that disease was a natural part of ageing. Consequently, accepting physical declines and illnesses, having a good quality of life, and remaining independent and engaged were seen as more important than being disease-free. Good Perceived Health primarily consisted of etic perspectives which assessed variations of self-rated health and physical constitution. The single contribution from an emic perspective similarly related to perceived health (‘feeling healthy and energetic’). General Health and Longevity were solely considered in emic perspectives. General Health centred around making conscious decisions to maintain a healthy lifestyle through eating well, not smoking or drinking, staying active and engaged, using medications as directed, and receiving regular medical check-ups. Longevity was briefly explored as living a long life and resisting the process of ageing.

Etic perspectives of Cognitive Function principally involved questionnaires or assessments, although thresholds for meeting the “high cognitive function” criteria varied. Emic perspectives focused on the importance of preserving cognition by use of examples: retaining senses, preserving personality and role in society, and having the ability to communicate. Absence of dementia was noted across both perspectives. Emic perspectives also emphasised maintaining cognition by way of good nutrition and exercise habits and mental stimulation. Etic perspectives were predominant in work focusing on Mental and Emotional Function, with the most frequently mentioned item being absence of depression, determined by a variety of tools. Self-reported mental health and absence of mental illness were also assessed. Emic perspectives similarly suggested that having good mental health and no mental illness were important for positive ageing, while also indicating the interconnectedness of physical and mental health.

Life Satisfaction and Well-being

Life satisfaction and well-being were predominantly considered from an etic perspective (82% etic vs. 18% emic). Etic considerations of Life Satisfaction were generally assessed through self-rating or scale instruments. Agreement that living up to 100 years of age is good and satisfaction with engagement activities were also considered. Emic perspectives similarly reflected satisfaction with life and living a long life. Well-being included consideration of quality of life. Etic perspectives focused on self-rated and assessed quality of life, while emic perspectives considered quality of life as synonymous with a good lifestyle where basic needs were met. Etic perspectives also considered assessment of physical, psychological, and mental well-being. Etic variables tended to consider Mood as a broad concept constituting positive/negative affect, somatic symptoms, interpersonal problems, emotional vitality, and self-evaluated mood. In contrast, emic perspectives centred around not feeling lonely.

Social and Productive

Etic perspectives predominantly contributed to this dimension (64% etic vs. 36% emic). Across Social Participation, etic and emic perspectives explored social contact and connection, with emic perspectives highlighting the added value of socialisation. Etic perspectives largely considered the frequency of social contact with family, friends, and neighbours. Comparably, emic perspectives included reference to maintaining social contact, positive social interaction, company, and relationships with the same groups. Positive relationships/interactions were highly valued from an emic perspective, providing meaning in life and mental stimulation. Emic perspectives also highlighted the role of communication technologies, personal mobility, and ethnic-specific agencies in facilitating social interaction. Furthermore, as a complement to socialisation, solitude was also valued.

Social Support from both perspectives included social networks and support provided by family, friends, and neighbours. Etic perspectives used various statements and tools to determine presence of social networks and support; emic perspectives focused on high quality and reciprocal relationships and having support networks available when needed. Specifically, friendships with those of a similar age and understanding (of language, culture, migration perspectives), transactional social relationships which enabled support to be exchanged, and having (or having had) a good marriage were valued. Having a spouse was not considered essential to all older adults, but companionship was appreciated.

Etic perspectives predominantly contributed to Active Engagement. Etic perspectives considered positive reports of participation in paid or volunteer work, social or leisure activities, family or household support/tasks, and/or religious activities as meeting the criterion for active engagement. However, there was a large degree of heterogeneity in specifying how often participation should occur. Having a strong sense of belonging to the local community and voluntary organisations were also indicative of active engagement. Emic perspectives generally considered similar activities as important but placed more emphasis on meaningful community involvement which positively contributed to the household or community. Emic perspectives also demonstrated specific methods of managing activity involvement (e.g. setting goals/plans to remain productive) and the need to gradually reduce involvement in activities (when necessary) to maintain self-respect.

Psychological and Psychosocial

Etic and emic perspectives similarly contributed to this dimension (52% etic vs. 48% emic). Personal Outlook incorporated intrinsic beliefs and had a similar etic-emic scope in three respects: spirituality, optimistic outlook/attitude, and resilience. Etic perspectives predominantly considered variations of self-rated positive ageing, although thresholds for determining positive ageing were discrepant. Additionally, etic perspectives considered self-efficacy in assessment of positive ageing. Emic perspectives contributed the significance of reminiscing on experiences, expressing gratitude for life and other people, maintaining interest and purpose in life, and living by personal values (e.g. not letting age determine abilities, aspiring to live a peaceful life).

Personal Resources largely reflected strategies for coping and maintaining a sense of control over age-related challenges and changes. Etic perspectives considered adjustment and assessment of mastery, while emic perspectives frequently considered acceptance (e.g. of the ageing process, health and physical abilities, and anticipated adverse events) and focused on various coping strategies. Examples of coping strategies included focusing on the present and one’s capabilities, making conscious decisions to reframe success and change behaviours, and proactively adapting actions and environment to match strengths.

Autonomy was presented in a similar manner across etic and emic perspectives in relation to independent community living (or living in a personally selected location). Emic perspectives also considered autonomy in more depth, presenting autonomy as freedom in decision-making and actions, self-sufficiency to avoid burdening others, and retaining self-mastery over one’s life.

Environment and Resources

Emic perspectives contributed to all five components (86%), while etic perspectives (14%) contributed only to Physical environment and Financial Security. Within these two shared components, emic perspectives included the essential elements from etic perspectives and presented specific examples. For instance, etic perspectives of Physical environment included assessment of perceived neighbourhood facilities (transport, amenities, somewhere nice to walk), services, and safety; emic perspectives included examples of having safe ramps and footpaths and limited ice/snow in winter. Likewise, etic perspectives of Financial Security considered perceived income security and gross annual income, while emic perspectives provided examples of having sufficient income to cover expenses, being free from financial worry, and living a dignified, independent, and engaged life. Emic perspectives also highlighted differences in financial security across contexts (e.g. receiving good crops and fishing catches).

Access to information, support, and services, Transport, and Housing were solely emic considerations. Access comprised access to reliable information, timely and affordable health/social support, and community services and facilities. Transport highlighted the importance of access to affordable transportation options and the ability to be mobile. Housing illustrated the significance of having and/or maintaining a comfortable home or living environment and preserving the functional capacity to care for the home. Furthermore, proactively addressing home hazards and security (e.g. with home modifications) to enhance safety/independence was valued.

Other

The majority of articles contributing additional variables/concepts were from an emic perspective (40% etic vs. 60% emic). There were clear differences in content across perspectives, indicating that distinct features are important for understanding positive ageing. Etic perspectives highlighted the utility of multidimensional positive ageing scales/ratings and the identification of pertinent personal characteristics through principal coordinate analysis. Conversely, emic perspectives considered the importance of end-of-life desires and preparation, well-being of family and friends, and animal companionship.

Conceptual model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults

Drawing from findings of the TNS, we propose a comprehensive conceptual model to illustrate the multidimensional nature of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults (). In essence, our positive ageing model illustrates the range of factors which contribute to older adults’ health and well-being in the community. This model is not intended to be hierarchical, instead we consider the six positive ageing dimensions to be complementary (as indicated by the dashed half-circle) and part of a holistic understanding of positive ageing. Our model consolidates etic and emic perspectives to highlight the similarities and discrepancies between perspectives. We have labelled the similarities between etic and emic perspectives as ‘consensus’ statements in our model, while we have referred to the discrepancies between perspectives as ‘exploratory’ statements which have been explored differently across perspectives. Both consensus and exploratory statements demonstrate the breadth of literature and highlight how the approach to data collection and interpretation shapes how positive ageing is conceptualised.

Figure 4. Conceptual model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults illustrating consensus and exploratory factors across etic and emic perspectives. Note. Consensus statements refer to the similarities across etic and emic perspectives; exploratory statements refer to the discrepancies between perspectives.

Discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to explore diverse positive ageing literature to clarify how positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults has been conceptualised in extant literature. To reflect diverse data and interpretation perspectives, we also considered similarities and distinctions between etic (closed/validatory) and emic (open/exploratory) perspectives. Using positive ageing as an all-encompassing umbrella term, we identified and consolidated literature from across a range of related conceptual origins and discourses. From the 75 articles located in our systematic search, we summarised article characteristics, methods, and positive ageing conceptualisations. Furthermore, we framed positive ageing in a meaningful way and synthesised all relevant literature across six dimensions using the TNS approach of Lucas et al. (Citation2007). Ultimately, we have generated a comprehensive and multidimensional conceptual model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults by consolidating complementary etic and emic perspectives.

Our findings indicate that (1) positive ageing literature, when considered in terms of the approach to data collection and interpretation, is diverse, comprising heterogeneous study characteristics, assessment variables, and concepts; (2) emic conceptualisations of positive ageing include essential elements from etic perspectives, while also including distinct features and indicating the wider impact of a concept; and (3) when consolidated, etic and emic perspectives are multidimensional and holistic, and offer a more meaningful conceptualisation of positive ageing. We use these findings to offer suggestions for the future development of positive ageing research and policy.

Evaluation of scoping review and TNS

The scoping review methodology facilitated use of an exploratory review question, rigorous and transparent methods, and systematic literature searches (Grant and Booth Citation2009; Munn et al. Citation2018). However, the exploratory nature of a scoping review also created challenges. As documented by Levac et al. (Citation2010), we similarly struggled to maintain a balance between comprehensiveness and feasibility. Our first iteration of full-text screening captured many articles with little relevance to the review question, leading us to agree with Bülow and Söderqvist (Citation2014) that “‘[positive] ageing’ has become an obligatory passage point for medical researchers, and for scholars” (p. 139). Only by revising our inclusion criteria and rescreening the full texts, were we able to locate a sample of relevant articles.

Descriptive summaries facilitated exploration of broad article characteristics and the etic-emic scope of positive ageing conceptualisations. Unexpectedly, methodology and theoretical frameworks were rarely mentioned across the 75 included articles, illustrating an area for future improvement. Situating research methodologically and theoretically helps to strengthen the research by adding rigour, facilitating understanding of how and why particular questions are asked, indicating the expertise brought to research data collection and interpretation, and signalling the possible intended audience. Likewise, methodological quality scores highlight the need for authors to improve the clarity of their reporting, especially in relation to sample/participant representativeness. Research was largely conducted in North American countries; however, exact details on participant ethnicity were infrequently provided. Positive ageing conceptualisations are known to differ according to culture (Hsu Citation2007; Hung et al. Citation2010), hence further exploration and integration of culturally-specific conceptualisations of positive ageing are required.

Given the findings of previous reviews (Cosco et al. Citation2013, Citation2014; Hung et al. Citation2010), it was unsurprising that etic perspectives of positive ageing dominated the included literature. Likewise, the predominance of the MacArthur model of successful aging (characterised by low probability of disease/disability, high physical, cognitive, and social functioning) (Bülow and Söderqvist Citation2014; Foster and Walker Citation2015; Rowe and Kahn Citation1987, Citation1997) potentially explains the popularity of ‘successful ageing’ terminology across perspectives, and the high frequency of grounding positive ageing conceptualisations in Physiological and/or Social and Productive dimensions. While most etic (61%) and all emic articles presented multidimensional conceptualisations of positive ageing, emic perspectives were broader and incorporated between three and six dimensions. This finding is unsurprising considering the data collection methods and interpretation that etic (validatory) and emic (exploratory) perspectives incorporate; etic perspectives often include a limited number of positive ageing indicators, such as disease or disability, while emic perspectives are typically based on narrative material from participants which are not limited to specific indicators. Furthermore, this finding concurs with previous suggestions that older adult’s conceptualisations, stemming from exploratory research, consider a more diverse range of features as important for positive ageing (Cosco et al. Citation2013; Hung et al. Citation2010; Nosraty et al. Citation2015).

TNS proved a useful way to synthesise evidence and draw conclusions across study designs and etic-emic contexts (Lucas et al. Citation2007). Across the six pre-defined dimensions, etic perspectives predominantly contributed to Physiological and Life Satisfaction and Well-being dimensions, while emic perspectives had a greater contribution to the remaining four dimensions. Of note, etic perspectives were not included in the Physiological components of General health and Longevity, nor in the Environment and Resources components of Access, Transport, and Housing. Etic perspectives were characterised by a wide variety of variables, tools, and thresholds used to determine positive ageing (Supplementary material 4). Interestingly, several articles from an etic perspective used data from pre-existing databases to assess positive ageing (e.g. Negash et al. Citation2011; Kahng Citation2008; ). Thus, constituent variables in a positive ageing assessment can differ substantially (Supplementary table 1), potentially explaining why other authors have highlighted variation in prevalence estimates of positive ageing (Depp and Jeste Citation2006; Peel et al. Citation2004). It was not within the scope of this review to specifically comment on the tools used to assess positive ageing. However, we do suggest that positive ageing assessment methods be standardised, while also acknowledging that the tool and threshold used will differ by context.

In our TNS, emic conceptualisations of positive ageing included the essential elements of etic perspectives, while also indicating the wider impact of a concept, making connections between components, and providing examples. The Environment and Resources and Other dimensions were the only exceptions to this statement, where clear differences across perspectives were noted. While emic perspectives tended to be more diverse than etic perspectives, there were also considerable differences across the range of emic articles. We viewed emic perspectives as both enhancing and extending our understanding of features important for positive ageing. These differences across etic and emic perspectives could potentially be explained by varying participant characteristics (such as age, ethnicity, culture, country), context (residential setting, income, access to resources), research design (aim, phrasing of the research question), and the researcher, as an integral part of the research process and interpretation.

Interpretation of conceptual model and implications for future research and policy

By consolidating findings from the TNS, we developed a comprehensive and multidimensional model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults, which may be a useful tool in future positive ageing research. Our positive ageing model illustrates the range of unique factors which contribute to the health and well-being of older adults. Our series of consensus and exploratory findings across the six dimensions illustrate the variables and concepts that were considered important from etic and emic perspectives. Specifically, the consensus findings in our model illustrate that etic perspectives (drawing on previously published theories and validated tools) are partially representative of emic perspectives (which often draw inductively from older adults’ perspectives) and therefore have a degree of significance to older adults. Equally, the exploratory statements tell us that theoretical understandings of positive ageing are not sufficient to cover all the features that older adults deem important. Ultimately, these findings support our argument that distinguishing perspectives based on the approach to data collection and interpretation is meaningful. Furthermore, this knowledge can inform research and policy initiatives to enhance positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults. However, researchers and policymakers must be careful not to assume that all older adults, at all times, view these features as important for their positive ageing in the community (Lewis and Buffel Citation2020).

The dashed half-circle in our model indicates the complementary and holistic nature of positive ageing. Just as easily, this half-circle could signify the dynamic factors which may impact how positive ageing is assessed and conceptualised, such as individual characteristics, specific context, research design, and researcher influence. The holistic nature of positive ageing and range of potential influences leads us to suggest that positive ageing differs across circumstances and measurement approaches and is a multidimensional concept that requires careful consideration of context and situation. In other words, positive ageing is not a one-size-fits-all approach and may be better suited to a policy orientation, rather than a static, universal concept. Coupled with the need for improved reporting of research methods, we suggest that researchers and policymakers acknowledge positive ageing as multidimensional and holistic, and we encourage triangulation of etic and emic perspectives. We recognise that it may be impractical to suggest all six dimensions of positive ageing be considered in future research and policy. However, we do argue that those using unidimensional or narrowly focused approaches should be cautious when interpreting their findings and reflect on the significant limitations that a narrow focus produces. We propose that researchers use our comprehensive model of factors contributing to older adults’ health and well-being as a guide when framing their research questions, data collection, and analysis.

In line with the study aim, our model has drawn solely from the literature examined in this review, limiting the identification of variables/concepts, and the relative importance of each, to evidence extracted from the included articles. Our model emphasises the individualistic nature of much of the (particularly etic) positive ageing literature. Only findings within the Environment and Resources dimension extended beyond the individual to highlight the role of the wider environment in supporting positive ageing in the community (e.g. Neighbourhood facilities, services, safety; Access to affordable transport). This finding is in contrast to recent policy advancements which consider the significance and influence of environmental supports on positive ageing (The Office for Seniors Citation2019; World Health Organization Citation2015). Furthermore, an ecological approach suggests environmental factors may have an overarching influence across the identified variables/concepts and interact with all aspects of wellbeing in important ways (Sallis et al. Citation2006). Advancing research in this same direction and considering the environment in a more sophisticated way (e.g. consideration of wider social, economic, cultural, and environmental contexts) will assist in updating traditional, biomedical, and individualistic concepts of positive ageing. Utility of our model might also be enhanced through considering what questions could be asked to measure aspects of positive ageing across the dimensions. Future work is needed to develop the model using targeted empirical work with an ecological focus and may potentially contribute to supporting stronger responses to policy aspirations for supportive and age-friendly communities.

Policy ultimately dictates the actions a government will take. Thus, it is important for researchers and policymakers to explore the environmental and structural/institutional barriers and facilitators to positive ageing to establish real-world change. Our conceptualisation of positive ageing provides the foundation for future research to elucidate the relationship between broad environmental factors and positive ageing.

Limitations

Our scoping review has several limitations. First, our search strategy was limited to positive ageing terms identified in previous systematic reviews and strict criteria on community-dwelling status. We considered positive ageing as an umbrella term, on the assumption that that we identified all relevant terms and that these concepts were comparable. However, there is the potential that articles using different terminology to assess or conceptualise positive ageing were excluded from our search results. Furthermore, articles that did not explicitly mention community-dwelling in title or abstract were excluded. Second, we considered etic and emic perspectives in relation to the emphasis and perspective of data and interpretation, rather than considering whether the conceptualisation originated from an older adult or researcher perspective (e.g. Hung et al. Citation2010). We highlight that while the distinction is helpful, etic and emic perspectives should not be seen as opposites or dichotomous, as researchers beginning with emic perspectives will often draw on etic perspectives as the research progresses (Fetterman Citation2012).

Third, we considered only English-language literature and consequently compiled a largely Western literature base. Additionally, we considered older age as ≥65 years for the international sample of articles included in this review. Differences in positive ageing conceptualisations are apparent across cultures (Hsu Citation2007) and life expectancy is not equivalent across (or even within) all nations and social groups, hence our conceptual model cannot be considered appropriate in all contexts. Fourth, we focused on published, peer-reviewed empirical literature, and excluded all grey literature. Grey literature searches may have revealed additional perspectives from policymakers or practitioners that were not reflected in our included articles. Finally, we did not consider the exclusion criteria of articles included in this review and, consequently, the participant perspectives not included in our synthesis. Nonetheless, we were able to extend previous reviews and develop a comprehensive model of positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults which illustrates the range of factors contributing to older adults’ health and well-being.

Conclusion

Through our systematic scoping review, we explored diverse positive ageing literature (from across conceptual origins and discourses) to clarify how positive ageing for community-dwelling older adults has been conceptualised. When considered in relation to data collection and interpretation approaches, positive ageing literature is diverse. Despite valuable similarities across approaches, differences persist between etic (validatory) and emic (exploratory) perspectives of positive ageing. Our conceptual model consolidates understanding of both differences and integration between etic and emic perspectives, highlighting the multidimensional and holistic nature of positive ageing, and offering a realistic and meaningful conceptualisation. Our positive ageing model illustrates the range of unique factors which contribute to the health and well-being of older adults. However, positive ageing literature remains individualistic. Positive ageing research and policy would benefit from additionally considering wider environmental supports to stimulate real-world change. We suggest our conceptual model is a useful tool for future positive ageing research, particularly in the stages of research question development, data collection, and analysis.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this scoping review.

Contribution of authors

Conceptualisation, T.P., A.W., J.W, and M.S.; methodology, T.P., A.W., J.W, and M.S.; validation, T.P. and D.R.; formal analysis, T.P.; investigation, T.P., D.R. and M.S.; data curation, T.P.; writing – original draft preparation, T.P.; writing – review and editing, T.P., A.W., J.W, D.R. and M.S.; visualization, T.P.; supervision, T.P., A.W., J.W, and M.S.; project administration, T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Table 3

Download MS Word (112.2 KB)Supplemental material 5 Emic perspectives

Download PDF (194 KB)Supplemental material 4 Etic perspectives

Download PDF (225.4 KB)Supplemental material 3 Complete MMAT scores

Download PDF (84.6 KB)Supplemental material 2 Full Search Strategy

Download PDF (77.8 KB)Supplemental material 1 PRISMA-ScR Fillable Checklist

Download PDF (653.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support and assistance of subject librarians Anne Wilson and Lorraine Nielsen of the Philson Library, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, The University of Auckland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arias-Merino ED, Mendoza-Ruvalcaba NM, Arias-Merino MJ, Cueva-Contreras J, Vazquez Arias C. 2012. Prevalence of successful aging in the elderly in Western Mexico. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2012.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 8(1):19–32.

- Bacsu J, Jeffery B, Abonyi S, Johnson S, Novik N, Martz D, Oosman S. 2014. Healthy aging in place: perceptions of rural older adults. Educational Gerontology. 40(5):327–337.

- Baker J, Meisner BA, Logan AJ, Kungl AM, Weir P. 2009. Physical activity and successful aging in Canadian older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 17(2):223–235.

- Beard JR, Officer A, de Carvalho IA, Sadana R, Pot AM, Michel J-P, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Epping-Jordan JE, Peeters GMEE, Mahanani WR, et al. 2016. The world report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet. 387:2145–2154.

- Bélanger E, Ahmed T, Filiatrault J, Hsiu-Ting Y, Zunzunegui MV. 2017. An empirical comparison of different models of active aging in Canada: the International Mobility in Aging Study. Gerontologist. 57(2):197–205.

- Bowling A. 2006. Lay perceptions of successful ageing: findings from a national survey of middle aged and older adults in Britain. European Journal of Ageing. 3:123–136.

- Bowling A. 2007. Aspirations for older age in the 21st century: what is successful aging? The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 64(3):263–297.

- Bowling A. 2008. Enhancing later life: how older people perceive active ageing? Aging & Mental Health. 12(3):293–301.

- Bowling A, Iliffe S. 2006. Which model of successful ageing should be used? Baseline findings from a British longitudinal survey of ageing. Age and Ageing. 35(6):607–614.

- Bronfenbrenner U. 1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist. 32(7):513–531.

- Brown LJ, Bond MJ. 2016. Comparisons of the utility of researcher-defined and participant-defined successful ageing. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 35(1):E7–E12.

- Bülow MH, Söderqvist T. 2014. Successful ageing: a historical overview and critical analysis of a successful concept. Journal of Aging Studies. 31:139–149.

- Burns RA, Browning C, Kendig HL. 2017. Living well with chronic disease for those older adults living in the community. International Psychogeriatrics. 29(5):835–843.

- Butler RN, Gleason HP. 1985. Productive aging: enhancing vitality in later life. New York: Springer Publishing.

- Byun J, Jung D. 2016. The influence of daily stress and resilience on successful ageing. International Nursing Review. 63(3):482–489.

- Carr K, Weir PL. 2017. A qualitative description of successful aging through different decades of older adulthood. Aging & Mental Health. 21(12):1317–1325.

- Carver LF, Beamish R, Phillips SP. 2018. Successful aging: illness and social connections. Geriatrics. 3:1.

- Castro-Lionard K, Thomas-Antérion C, Crawford-Achour E, Rouch I, Trombert-Paviot B, Barthélémy JC, Laurent B, Roche F, Gonthier R. 2011. Can maintaining cognitive function at 65 years old predict successful ageing 6 years later? The PROOF study. Age and Ageing. 40(2):259–265.

- Chen L, Ye M, Kahana E. 2020. A self-reliant umbrella: defining successful aging among the old-old (80+) in Shanghai. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 39(3):242–249.

- Choi M, Lee M, Lee MJ, Jung D. 2017. Physical activity, quality of life and successful ageing among community-dwelling older adults. International Nursing Review. 64(3):396–404.

- Chou KL, Chi I. 2002. Successful aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old Chinese. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 54(1):1–14.

- Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BCM, Brayne C. 2013. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. 3:e002710.

- Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephan BCM, Brayne C. 2014. Operational definitions of successful aging: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 26(3):373–381.

- Curcio CL, Pineda A, Quintero P, Rojas A, Muñoz S, Gómez F. 2018. Successful aging in Colombia: the role of disease. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 4:233372141880405.

- Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. 2013. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 13(1):48.

- Davey J, Glasgow K. 2006. Positive ageing: a critical analysis. Policy Quarterly. 2(4):21–27.

- DeCarlo TJ. 1974. Recreation participation patterns and successful aging. Journal of Gerontology. 29(4):416–422.

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. 2006. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14(1):6–20.

- Dizon L, Wiles J, Peiris-John R. 2020. What is meaningful participation for older people? An analysis of aging policies. The Gerontologist. 60(3):396–405.

- Dumitrache CG, Rubio L, Cordón-Pozo E. 2019. Successful aging in spanish older adults: the role of psychosocial resources. International Psychogeriatrics. 31(2):181–191.

- Everard KM, Lach HW, Fisher EB, Baum MC. 2000. Relationship of activity and social support to the functional health of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 55(4):S208–S212.

- Feng Q, Son J, Zeng Y. 2015. Prevalence and correlates of successful ageing: a comparative study between China and South Korea. European Journal of Ageing. 12(2):83–94.

- Fernández-Ballesteros R, Robine JM, Walker A, Kalache A. 2013. Active aging: a global goal. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 298012.

- Fetterman DM. 2012. Emic/etic distinction. In: Given LM, editor. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; p. 249–250.

- Flood M. 2006. A mid-range nursing theory of successful aging. Journal of Theory Construction and Testing. 9(2):35–39.

- Ford AB, Haug MR, Stange KC, Gaines AD, Noekler LS, Jones PK. 2000. Sustained personal autonomy: a measure of successful aging. Journal of Aging and Health. 12(4):470–489.

- Formiga F, Ferrer A, Megido MJ, Chivite D, Badia T, Pujol R. 2011. Low co-morbidity, low levels of malnutrition, and low risk of falls in a community-dwelling sample of 85-year-olds are associated with successful aging: the Octabaix study. Rejuvenation Research. 14(3):309–314.

- Foster L, Walker A. 2015. Active and successful aging: a European policy perspective. The Gerontologist. 55(1):83–90.

- Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Spillman BC. 2017. Successful aging through successful accommodation with assistive devices. The Journals of Gerontology: series B. 72(2):300–309.

- García-Lara JMA, Navarrete-Reyes AP, Medina-Méndez R, Aguilar-Navarro SG, Avila-Funes JA. 2017. Successful aging, a new challenge for developing countries: the Coyoacán cohort. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 21(2):215–219.

- Garfein AJ, Herzog AR. 1995. Robust aging among the young-old, old-old, and oldest-old. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 50B(2):S77–S87.

- Gold DT, Pieper CF, Westlund RE, Blazer DG. 1996. Do racial differences in hypertension persist in successful agers? Findings from the MacArthur Study of Successful Aging. Journal of Aging and Health. 8(2):207–219.

- Grant MJ, Booth A. 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 26:91–108.

- Grimmer K, Kay D, Foot J, Pastakia K. 2015. Consumer views about aging-in-place. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 10:1803–1811.

- Gureje O, Oladeji BD, Abiona T, Chatterji S. 2014. Profile and determinants of successful aging in the Ibadan Study Of Ageing. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 62(5):836–842.

- Gwee X, Nyunt MSZ, Kua EH, Jeste DV, Kumar R, Ng TP. 2014. Reliability and validity of a self-rated analogue scale for global measure of successful aging. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 22(8):829–837.

- Habib R, Nyberg L, Nilsson LG. 2007. Cognitive and non-cognitive factors contributing to the longitudinal identification of successful older adults in the Betula Study. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 14(3):257–273.

- Hamid TA, Momtaz YA, Ibrahim R. 2012. Predictors and prevalence of successful aging among older Malaysians. Gerontology. 58(4):366–370.

- Hank K. 2011. How “successful” do older Europeans age? Findings from SHARE. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 66B(2):230–236.

- Holmes J. 2006. Successful ageing: a critical analysis [Doctoral thesis]. Massey Research Online: massey University.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, et al. 2018. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Canada: canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada.

- Hörder HM, Frändin K, Larsson MEH. 2013. Self-respect through ability to keep fear of frailty at a distance: successful ageing from the perspective of community-dwelling older people. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 8:20194.

- Hsu HC. 2007. Exploring elderly people’s perspectives on successful ageing in Taiwan. Ageing and Society. 27:87–102.

- Hung L-W, Kempen GIJM, De Vries NK. 2010. Cross-cultural comparison between academic and lay views of healthy ageing: a literature review. Ageing and Society. 30(8):1373–1391.

- Jang SN, Choi YJ, Kim DH. 2009. Association of socioeconomic status with successful ageing: differences in the components of successful ageing. Journal of Biosocial Science. 41(2):207–219.

- Jeste DV, Savla GN, Thompson WK, Vahia IV, Glorioso DK, Martin AS, Palmer BW, Rock D, Golshan S, Kraemer HC, et al. 2013. Association between older age and more successful aging: critical role of resilience and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 170(2):188–196.

- Kahng SK. 2008. Overall successful aging: its factorial structure and predictive factors. Asian Social Work and Policy Review. 2(1):61–74.

- Lamb VL, Myers GC. 1999. A comparative study of successful aging in three Asian countries. Population Research and Policy Review. 18:433–450.

- Lee JJ. 2009. A pilot study on the living-alone, socio-economically deprived older Chinese people’s self-reported successful aging: a case of Hong Kong. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 4:347–363.

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien K. 2010. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 5(1):69.

- Lewis C, Buffel T. 2020. Aging in place and the places of aging: a longitudinal study. Journal of Aging Studies. 54.

- Li C, Wu W, Jin H, Zhang X, Xue H, He Y, Xiao S, Jeste DV, Zhang M. 2006. Successful aging in Shanghai, China: definition, distribution and related factors. International Psychogeriatrics. 18(3):551–563.

- Li CI, Lin CH, Lin WY, Liu CS, Chang CK, Meng NH, Lee YD, Li TC, Lin CC. 2014. Successful aging defined by health-related quality of life and its determinants in community-dwelling elders. BMC Public Health. 14:1.

- Lin PS, Hsieh CC, Cheng HS, Tseng TJ, Su SC. 2016. Association between physical fitness and successful aging in Taiwanese older adults. PLoS ONE. 11:3.

- Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, Law C, Roberts HM. 2007. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 7:4.

- Markee N. 2012. Emic and etic in qualitative research. In: Chapelle CA, editor. The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Martin AS, Palmer BW, Rock D, Gelston CV, Jeste DV. 2015. Associations of self-perceived successful aging in young-old versus old-old adults. International Psychogeriatrics. 27(4):601–609.

- Martinson M, Berridge C. 2015. Successful aging and its discontents: a systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The Gerontologist. 55(1):58–69.

- Maxwell JA, Chmiel M. 2014. Notes toward a theory of qualitative data analysis. In: Flick U, editor. The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- McLaughlin SJ, Connell CM, Heeringa SG, Li LW, Roberts JS. 2010. Successful aging in the United States: prevalence estimates from a national sample of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 65B(2):216–226.

- Ministry of Social Policy. 2001. The New Zealand Positive Ageing Strategy.

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. 2018. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 18:143.

- Negash S, Smith GE, Pankratz S, Aakre J, Geda YE, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Petersen RC. 2011. Successful aging: definitions and prediction of longevity and conversion to mild cognitive impairment. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 19(6):581–588.

- Newman AB, Arnold AM, Naydeck BL, Fried LP, Burke GL, Enright P, Gottdiener J, Hirsch C, O'Leary D, Tracy R. 2003. “Successful aging”: effect of subclinical cardiovascular disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 163(19):2315–2322.

- Ng TP, Broekman BFP, Niti M, Gwee X, Kua EH. 2009. Determinants of successful aging using a multidimensional definition among Chinese elderly in Singapore. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 17(5):407–416.

- Nguyen H, Lee JA, Sorkin DH, Gibbs L. 2019. “Living happily despite having an illness”: perceptions of healthy aging among Korean American, Vietnamese American, and Latino older adults. Applied Nursing Research. 48:30–36.

- Nosraty L, Jylhä M, Raittila T, Lumme-Sandt K. 2015. Perceptions by the oldest old of successful aging, vitality 90+ study. Journal of Aging Studies. 32:50–58.

- Nosraty L, Pulkki J, Raitanen J, Enroth L, Jylhä M. 2019. Successful aging as a predictor of long-term care among oldest old: the vitality 90+ study. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 38(4):553–571.

- Park SM, Jang SN, Kim DH. 2010. Gender differences as factors in successful ageing: a focus on socioeconomic status. Journal of Biosocial Science. 42(1):99–111.

- Peel N, Bartlett H, McClure R. 2004. Healthy ageing: how is it defined and measured? Australasian Journal on Ageing. 23(3):115–119.

- Phelan EA, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ, Larson EB. 2004. Older adults’ views of ‘‘successful aging’’ – How do they compare with researchers’ definitions? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 52:211–216.

- Phelan EA, Larson EB. 2002. "Successful aging” - where next? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 50(7):1306–1308.

- Puig-Domingo M, Serra-Prat M, Merino MJ, Pubill M, Burdoy E, Papiol M, Mataró Aging Study Group. 2008. Muscle strength in the Mataró aging study participants and its relationship to successful aging. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 20(5):439-446.

- Ranzijn R. 2010. Active ageing —another way to oppress marginalized and disadvantaged elders? Journal of Health Psychology. 15(5):716–723.

- Register ME, Herman J, Tavakoli AS. 2011. Development and psychometric testing of the register - connectedness scale for older adults. Research in Nursing & Health. 34(1):60–72.

- Reker GT. 2001. Prospective predictors of successful aging in community-residing and institutionalized Canadian elderly. Ageing International. 27(1):42–64.

- Rodriguez-Laso A, McLaughlin SJ, Urdaneta E, Yanguas J. 2018. Defining and estimating healthy aging in Spain: a cross-sectional study. The Gerontologist. 58(2):388–398.

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL. 1987. Human aging: usual and successful. Science. 237(4811):143–149.

- Rowe JW, Kahn RL. 1997. Successful aging. The Gerontologist. 37(4):433–440.

- Rubinstein RL, de Medeiros K. 2015. “Successful aging,” gerontological theory and neoliberalism: a qualitative critique. The Gerontologist. 55(1):34–42.

- Rubio E, Lázaro A, Sánchez-Sánchez A. 2009. Social participation and independence in activities of daily living: a cross sectional study. BMC Geriatrics. 9.

- Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. 2006. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annual Review of Public Health. 27:297–322.

- Sarnak MJ, Katz R, Fried LF, Siscovick D, Kestenbaum B, Seliger S, Rijkhi D, Tracy R, Newman AB, Shlipak MG. 2008. Cystatin C and aging success. Archives of Internal Medicine. 168(2):147–153.

- Sato-Komata M, Hoshino A, Usui K, Katsura T. 2015. Concept of successful ageing among the community-dwelling oldest old in Japan. British Journal of Community Nursing. 20(12):586–592.

- Sixsmith J, Sixsmith A, Fänge AM, Naumann D, Kucsera C, Tomsone S, Haak M, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Woolrych R. 2014. Healthy ageing and home: the perspectives of very old people in five European countries. Social Science & Medicine. 106:1–9.

- Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI, Cohen R. 2002. Successful aging and well-being: self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. The Gerontologist. 42(6):727–733.

- Tate RB, Swift AU, Bayomi DJ. 2013. Older men's lay definitions of successful aging over time: the Manitoba follow-up study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 76(4):297–322.

- The Office for Seniors. 2019. Better Later Life – He Oranga Kaumātua 2019 to 2034.

- Thompson WK, Charo L, Vahia IV, Depp C, Allison M, Jeste DV. 2011. Association between higher levels of sexual function, activity, and satisfaction and self-rated successful aging in older postmenopausal women. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 59(8):1503–1508.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. 2018. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 169:467–473.

- Troutman M, Nies MA, Davis B. 2013. An examination of successful aging among southern Black and White older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 39(3):42–52.