ABSTRACT

Renewed focus on mental health has put the spotlight on the ‘black box’ that is the acute mental health facility. Drawing on a larger programme of research, key issues relevant to the planning and design of mental health units were identified from in-depth interviews with those using the facilities. Contemporary issues included visibility from the outside and wayfinding, the need to accommodate cultural needs extending to the family and community, safety and violence, the need for access to nature and fresh air, and facilitating meaningful activities. Stigma and its spatial expression were a crosscutting theme throughout.

Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry; identifier: ACTRN12617001469303.

Introduction

The design of acute mental health units has changed significantly over time with them fulfilling different functions depending on the context and the era. Historically their initial purpose was to contain, control and facilitate social segregation (Foucault Citation1976; Pevsner Citation1976); however, increasingly they became an environment to treat or rehabilitate people suffering from mental illness (Vavyli Citation1992; Bartlett and Wright Citation1999; Yohanna Citation2013). There were even attempts to provide refuge and sanctuary, mostly depending on socio-cultural and economic conditions of a particular period rather than an evolution of models from custodian to more caring. For example, the York Retreat (Edginton Citation1997) of Lamel Hill in York, the UK, which opened in 1796, adopted a ‘moral treatment’ behavioural model and introduced the design of spatial qualities of peaceful spaces, surrounded by nature and the countryside, opportunities for meaningful work and recreation. Physical restraints and punishment were substituted by physical activity and the alienating conditions of the former asylums were replaced by a greater sense of community. Similarly, the Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex County UK, built in 1831 for the ‘pauper insane’ under the initiatives of Dr. William Charles Ellis, successfully deployed theories for the therapeutic value of meaningful work, therapy and care (Suzuki Citation1995).

After the second part of the nineteenth century and as social-economic conditions deteriorated and unemployment rose, psychiatric inpatients in many institutions lost the opportunity to participate in creative and productive practices. Hard labour remained but, on many occasions, was not accompanied by a sense of achievement, as patients were not producing something meaningful. Patient numbers grew significantly, staff numbers fell and the conditions inside psychiatric institutions deteriorated. Yet, as the evolution of care was not the same everywhere, glimpses of change started to appear in several parts of the world from the end of the First World War onwards. The birth of psychiatry as a discipline and the gradual change of power from judges to psychiatrists as responsible for determining patients’ status, facilitated the trend towards inclusion of the psychiatric ward in the general hospital and later the community as models of care (Chrysikou Citation2014). The latter was introduced with the development of social psychiatry after the return of large numbers of shell-shocked soldiers after WW1. The subsequent establishment of social care in the late 1920s and 1930s in countries, such as the UK, was fuelled in the 1960s by the realisation that the new antipsychotic drugs could not offer a permanent cure and that care in the community was humane and financially sound as advocated by President Kennedy. Psychiatric inpatient numbers peaked during the 1950s, which is speculated to have contributed to the need for change (Houston Citation2020). Service users started to create advocacy bodies (Gallagher Citation2017) and sometimes managed their mental health projects, such as the Clubhouses (Chrysikou Citation2014). Community mental health facilities emerged in countries, such as the US, France and the UK, following a trajectory of experimentation that fostered local variations and later expanded to other European countries as a result of a central policy of de-institutionalisation (World Health Organization Citation2015). These developments started to change the psychiatric provision of services across the world.

In New Zealand, the process of de-institutionalisation started in the 1960s (MacKinnon and Coleborne Citation2003). The increasing dissatisfaction with the old-style ‘asylum’ model and advances in the development of pharmaceuticals to treat mental illnesses, along with the clear financial arguments for treatment closer to home, fuelled the process of de-institutionalisation in New Zealand. This was a gradual process, from a halt in planning new institutions in 1963, and a stop to building institutional accommodation in 1973 and further closures in the 1980s (MacKinnon and Coleborne Citation2003). The eventual de-commissioning of old-style institutions and the movement of their residents back into the community as outpatients led to the emergence of contemporary acute mental health units as additions to general public hospitals. Rather than long-term care, these units aimed to provide short-term care and stabilisation for those experiencing symptoms that could not be safely treated in the community.

In New Zealand today, psychiatric care and treatment are now delivered through a web of services including crisis services, short-term and general-hospital-based acute psychiatric care units and outpatient services. However, this has not worked out as expected. Psychotropic medications have not successfully improved function for all people even when they ameliorate symptoms, and underfunded community mental health services have been overwhelmed with a demand they have struggled to handle (Patterson et al. Citation2018). The quality and availability of outpatient services vary widely, and most modern acute mental health units, often hidden from public sight, remain as much of a mystery to the general public as the historic asylums.

Contemporary trends for acute mental health facilities include a greater variety of spaces, inside and outside, to accommodate the complex range of service user presentations (Weich et al. Citation2002; Galea et al. Citation2005; Mair et al. Citation2008). In particular, there is a need for greater access to therapeutic outdoor spaces that provide for social interaction and contemplation (Liddicoat et al. Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022b). New research into the interior architecture of acute mental health facilities has increased focus on the service user experience following recovery models of care. These stress the importance of greater service user autonomy, social connectivity, cultural identity, meaningful activities, empowerment and safety (Jenkin et al. Citation2021a). Environmental qualities, such as indoor air quality, natural light, noise and perceived attractiveness, are also shown to be influential in patient recovery (Shepley et al. Citation2016; Jenkin et al. Citation2022).

In New Zealand, an acute mental health unit is a publicly funded space with restricted access. Such units provide short-term mental health care, primarily by diagnosis, stabilisation, medication and respite for people experiencing acute and serious mental distress (Jenkin et al. Citation2021a). While there is a lack of clarity and agreement on unit purpose, the underpinning philosophy of mental health care in New Zealand, as in many other western jurisdictions, is the recovery model (Jenkin et al. Citation2021a). This paper explores the key contemporary social issues relevant to the architectural design of acute mental health units as identified by those who use them.

Materials and methods

This research reports on interview data collected as part of a large study ‘Acute Mental Health Facility Design: The New Zealand Experience’ conducted between 2017 and 2020 to examine the design and social milieu of acute adult inpatient mental health units in Aotearoa New Zealand. The study protocol is available at: http://www.ANZCTR.org.au/ACTRN12617001469303.aspx, accessed 26 February 2021.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Central Health and Disability Ethics Committee in 2017 (17/CEN/94). Consultation with Ngāi Tahu Research Consultation Committee was undertaken as per the University of Otago requirements for research proposals involving Māori.

Case selection method: With the help of the Office of the Ombudsman and our list of 21 publicly-funded adult inpatient acute mental health units across NZ, we developed a prioritised list for a diverse sample, based on age and condition, location and setting and size, on the understanding that the diverse sampling strategy would provide us with the most learning (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008). The first four units from our prioritised list agreed to participate in this research.

Interviews: GJ, a social scientist and experienced qualitative researcher, conducted 96 interviews with staff, service users and visiting family members in the four units during 2018–2019 (). Staff were recruited with the consent of the management of the units and were selected purposely to ensure some representation from the key health professionals working in the facilities. These included nurses, mental health support workers, occupational therapists, cultural or consumer engagement advisors, social workers, psychiatrists and clinical team leaders. Service users were recruited with the help of various staff, once approved by the lead clinician as well enough, competent and willing to consent to participate. Sometimes service users changed their minds and withdrew their interest in participating before the interview could take place, resulting in the need for extra site visits to increase the number of participants. Family members were recruited by way of poster advertisements around the unit entrance and notices were sent to consumer and family support NGOs to assist in recruitment. Due to resource limits, interview numbers for each participant group were capped at 10.

Table 1. Case study and participant characteristics.

Interview questions were developed by GJ and DP based on the broad study aims, pilot-tested with a sample of nurses known to the study investigators and service users from the Ombudsman service user advisory group, and refined by the lead author (GJ). The interviews, lasting 30–90 min were conducted by GJ, audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Eighty-six interviews were conducted face to face in a private room on the unit and 10 were conducted by phone. The questions asked followed three general topic areas: Physical Environment (including decoration, furniture, aesthetics and sensory aspects), Therapeutic Environment (available therapies and activities) and Social Organisation (unit rules, regimes, social relations and cultural issues). For each of these topics staff, service users and visiting family members were asked what they thought or felt about the topic, what they liked and disliked, where and how they spent their time on the unit, and what services and resources they used and wanted.

Analysis: GJ and JM, DP and SEP, separately identified themes in the interview transcripts, then met together to discuss, refine and agree on the key common themes in the data following the multi-step process outlined by Clarke and Braun (Citation2017): familiarisation with the data, generating initial codes, generating themes, defining and naming themes and writing up the themes.

Reflexivity: Our team was multi-disciplinary, predominantly female with one male, and comprised a social scientist, an academic with lived experience of mental illness, an academic psychiatrist and three academic architects. Although we acknowledge that research in the field is moving towards the involvement of research participants in the data analysis, and that practices of co-design are deemed especially critical in the area of mental health where the voices of those with lived experience have been largely overlooked or absent, this was not possible in this study due to resource and time constraints and it would have added a level of complexity to an already complex project and setting.

Data and subject matter sensitivity: Our participants were aware and agreed that their quotes might be used in the research outputs, so we assured anonymity. For this reason, in place of names we have used a code to show the unit the participant was speaking from (A–D), their participant group (S for Staff, MH for service user and F for family member of service user), their gender and ethnicity (M for Māori NM for non-Māori) and participant number.

We note that the results should be read with some caution as some of the quotes might be confronting and sensitive for some readers. However, we decided not to sanitise and edit these as their authenticity provides the most compelling illustration of the participants’ perspectives and experiences of the issues. Participants who opted in the consent form to receive the study results were provided with a high-level lay summary, following a similar format as the results of this paper using, direct to their email/postal address in late 2021.

Results

The key characteristics of the four facility case studies and participant characteristics are given in .

As shown in , between 19 and 28 interviews were conducted for each facility. Despite the number of interviews for each participant group being capped at 10, greater than anticipated interest in participation meant that a few more interviews were conducted than anticipated, for the staff and service user groups. Family members were the most difficult to recruit (we speculate that this may be due to stigma) and none were recruited for the last case study as the budget only provided for site visits to three facilities.

Key design themes

We identified five key design-related themes () common across all case studies and one cross-cutting theme:

Incorporating cultural and spiritual values and needs and family/whanau visitors.

The need for outdoor spaces and access to nature and fresh air.

Lack of therapies, models of care and meaningful activities.

Issues around safety and violence in the unit.

Visibility of units, entry thresholds and wayfinding.

Stigma was a cross-cutting theme interweaving through all the other themes.

Incorporating cultural and spiritual values and needs and family/whānau visitors

Although many service user participants reported that they had no visitors, with staff explaining that this was often due to stigma around visiting a mental health facility, staff and service users supported the universal provision of family/whānau rooms which were provided in all four units.

The family/whānau room is critical as it provides a space for service users to meet with family and friends without visitors needing to enter other areas of the facility. This room can provide a safe space for visiting relatives including children which is important for maintaining connections and demystifying and destigmatising mental illness. In all cases, the family/whānau room was located near the entrance to the unit. However, the four case studies varied considerably in the space allocated for this purpose (from seating for 4 to more than 20). One unit’s whānau room () was 2 m × 3 m; a space so small it was difficult to photograph, with this room intended to serve a 64-bed facility.

Other whānau rooms were basic, uninviting and run down, or lacked windows ().

It’s a very small room. I wouldn’t call it a whānau room. You would not get much of a whānau in there. Yeah, you might get your mum and dad and a kid but that’s about it. We would need bigger spaces for a whānau room. (C_S_M_NM_5)

Figure 4. Whare – for culturally appropriate admissions and cultural activities, like waiata (singing) and karakia (prayer).

Various unit rules and layouts resulted in different issues being faced in different units. In one unit a father wanting to visit his suicidal daughter could not because the small family room () was occupied and he was not, as a male, allowed down the female corridor:

Their reasoning being there are other vulnerable patients who perhaps have been a victim of sexual assault … And there was a small lounge at the top end of the [female] corridor where I thought you could probably meet there but it still was in the corridor so he [service users’ father] couldn’t do that. My husband couldn’t do that. (C_F_F_NM_3)

I guess the only privacy issue I had was with visitors and it wasn’t always about my visitors, it was about other people’s visitors, like there was a visitor on the ward that I’ve known from years ago, and I thought I don’t want them to know that I’m unwell. (C_MH_M_M_6)

The need for outdoor spaces and access to nature and fresh air

Although all facilities featured courtyards, and in three units these were internal, they varied in the degree to which they contained any greenery or nature. Hard surfaces dominated the majority of the unit’s outdoor spaces, even in the newest facility featuring two modern internal courtyards, nature and greenery were sparse (see ).

Accommodation for outdoor activities was also very limited by the basic nature of the courtyards. The predominant way the courtyards were used by service users in three of the four case study facilities, was for smoking and the socialisation that accommodated this activity (Jenkin et al. Citation2021b). Despite the smoke-free policy in all hospitals, only one acute mental health unit, Unit D, succeeded in achieving a smoke-free environment.

Smoking in the courtyards led to complaints from non-smoking service users who saw the courtyards as ‘gross’ due to the smell and mess created by smoking:

always smells like smoke, which is fine if you’re a smoker, but … (C_MH_F_M_1)

There’s nowhere else to sit except out in the courtyard or stand in the courtyard basically because the tables are covered in cigarette butts and disgusting things. (A_MH_F_NM_2)

I gave up smoking. I pretty much [spent] a whole lot of time on my own because most people were outside in the courtyard smoking or hanging around in smoking area. (A_MH_F_NM_6)

There’s nowhere for people to bring their family to visit … there’s two picnic tables and they’re usually full of smokers and there’s nowhere to go with your visitors. (A_MH_F_NM_2)

Lack of therapies, models of care and meaningful activities

Staff and service users from all four units noted a lack of available therapies. While professional staff on the unit consisted of psychiatrists, nurses, support workers, social workers, and cultural or consumer engagement advisors, medication was described by staff as the primary intervention. This was to the extent that staff described the model of care as ‘beds and meds’:

The end of the day it’s meds and beds. We have to medicate people; they have to be in beds. Most people on the ward are on some medication. (B_S_F_NM_9)

They’re wanting therapy, they’re wanting talking therapies, they're wanting all this sort of stuff. [In a better system] you would actually be able to cater to that a lot more. It would help them. (A_S_F_NM_4)

I at least expected someone to be talking to me. (C_MH_F_NM_12)

I was expecting a psychologist or social worker to be talking to me and sort of—you know, making a baseline to help me get my life sorted, when I go out or what to do during a day or just really practical stuff. (C_MH_F_NM_12).

Well, I just wish that they could get a group of people that have actually been through what I’ve went through, and I’ve been inside that place and I’m sure heaps of us have been traumatized too and we haven’t really talked about because I haven’t talked about it, really, not for five years, to anyone. (C_MH_F_NM_5)

There’s nothing to do, you get bored, you get agitated … And the only programs they have here are for three-year olds. They offer colouring in and drawing. (A_MH_F_M_9)

… we had a kaumātua [Māori elder that visited the ward] years ago … he’d do carving and the boys just loved that. (C_S_F_NM_2)

A gym would be fabulous! (C_S_M_NM_5)

A lot of patients get overweight because of their medication and they’re unfit. And a lot of patients also need to release energy and get those endorphins going. So, a treadmill, a boxing bag, some gloves, maybe some weights? (A_MH_F_M_9)

Issues around safety and violence in the unit

Staff and service users were asked if they felt safe in the acute mental health unit. Although staff and service users reported feeling safe on the unit most of the time, most staff and many service users recalled seeing or experiencing violence on the unit, towards others or themselves and even towards visitors. While we acknowledge that only a very few service users engage in violence in a mental health unit, violence appeared as such a salient issue that it warranted a separate paper (see Jenkin et al. Citation2022). From that analysis we found four broad themes identified by both staff and service users as contributing to violence: individual factors, physical environmental factors, organisational factors and the social milieu of the unit (Jenkin et al. Citation2022).

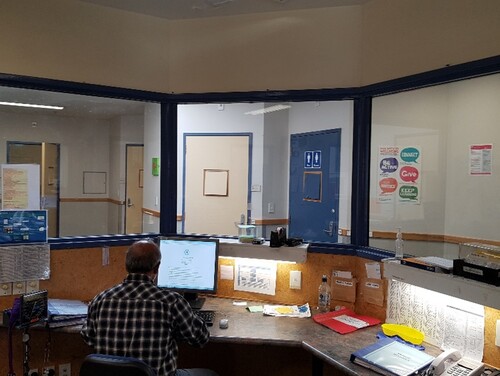

Physical environmental factors identified as contributing to violence in the unit included unit layouts that resulted in poor lines of sight and blind spots, poor temperature control, especially being too hot and a lack of ventilation, insufficient space (to manage agitated service users), issues of proximity between certain areas (nurses becoming barricaded in some areas) and lack of access to alarms (staff and service users) and insufficient exits (staff). Perhaps the most problematic design issue contributing to violence was the old-style glassed-in fishbowl staff stations ( and ).

These are the hub of activity for staff, the ‘control tower’, and outside, is a place of congregation for service users seeking help to meet basic needs, such as requests for a hairdryer or a phone charger. Their purpose as currently designed is that the staff can generally see the service users and service users can see the staff. However, the data revealed that service users did not feel ‘seen’. Staff, busy with an increasing documentation agenda, were often working on computers so were perceived by the service user as though they were ignoring them. This design speaks through its structure, that a unit is a dangerous place where staff need to lock themselves safely away. It also reveals the staff’s privilege of safety.

You can be quite vulnerable if someone’s really aggressive, and you have to retreat to the nurses’ station, and you’ve got nowhere you can go. You’ve just got to hope the door holds. (B_S_M_NM_3)

[Staff are] fearful for their safety while you’re standing on the other side of the glass and you’re actually quite terrified yourself. (A_MH_F_NM_6)

From the service user perspective, other aspects of the social milieu were also important contributors to violence in the unit. In particular were the issues of boredom and the lack of autonomy due to the dominant model of care being one of the locked doors, that restrict, control, and confine service users:

You’re reduced to being three years old. You’re getting your nappies changed, sort of shit. It’s just really bad. You have to ask for pull-ups, or you have to ask for your period pads and stuff like … for an independent adult, it’s really hard to regress back to a child state, where you’re banned from going outside. (B_MH_F_M_1)

I know that people have problems and they could probably destroy things or whatever … I notice that people get very bored … This is supposed to be a health facility … not a gang … I feel like I’m in prison. I actually feel like I’m in prison. (A_MH_F_NM_6)

It’s stigma … it feels like they’re working with prisoners. It almost feels like we’re criminals, even though, some of us can function, and others can’t. Different degrees obviously on the spectrum but at the end of the day it just feels like they don’t want to be near you. You know everything’s blocked off, everything’s, yeah, it’s just, it’s really, really is over the top. (A_MH_F_NM_2)

I mean, honestly, it’s a prison, basically. I used to call myself an inmate, basically. It’s not a nice situation to be in. Like you’re not choosing to be there. It’s not normal life. It’s not … it’s atrocious. (A_MH_M_NM_10)

Other people taking your cigarettes off you. And if it’s anybody too violent, and they want them, you just … I’ve handed all mine over before unwillingly and yeah. Cigarettes are a big problem in there actually. (A_MH_F_NM_8)

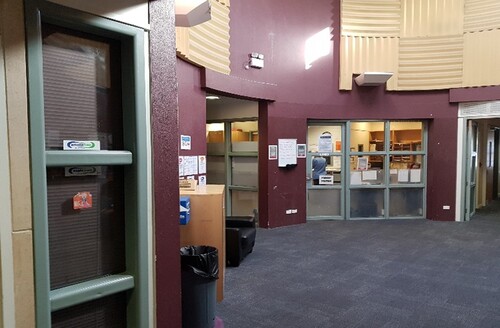

Visibility of units, entry thresholds and wayfinding

Visibility of the unit, versus invisibility, was one of the key themes that came out of the data from service user and family interviews. This refers to how visible and accessible the acute mental health unit is to the public. We know from UK research that acute mental health facilities are typically hidden from the public eye (Chrysikou Citation2017). In many cases, this is also true in NZ where acute mental health units are often situated at the back of the hospital. Being hidden from public view can make these units hard to find as one mother, trying to visit her suicidal daughter on the unit explained:

I came in from the main hospital … I was trying to read the instructions and follow the corridor. And then I was going up and down and around. And then I got to the stairwell that had a sort of said maternity and then I was trying to figure out where’s mental health. … I was so stressed by then. I actually cried and there were people going past looking at me weird cause it was over by the maternity entrance. And I was just so overwhelmed by then. I’m thinking, where is she? I wanted to get to her. And so, I finally figured out you go down these stairs and as I was doing all that, all I could think was I was going down to the dungeon, the bottom, the pit of the hospital where no one cares. The people that no one cares about. (C_F_F_NM_3)

Stigma

The stigma of mental illness was a theme woven throughout the findings. Inadequate resourcing of acute mental health services is an institutional stigma embodied in the poor physical environment, dilapidated appearance, dated layout and furnishing of the facilities themselves. This stigma is likely exacerbated by their often ‘out of public sight’ location. Many mental health facilities being ‘out of sight out of mind’, have obscured uncelebrated entrances and a lack of signposting making wayfinding complex and challenging.

However, because of stigma, not everyone wants a celebrated entrance to the facility, with privacy and invisibility preferred by some. One service user interviewed, was so worried about being seen entering a mental health unit that he crouched in the back seat of the car as his partner drove up, horrified by the huge two metre by two metre sign ‘Acute Mental Health Unit’ at the street entrance to the facility.

Stigma is also expressed in the exterior aesthetics of many acute mental health facilities. Caged outdoor courtyards, while providing access to the outdoors, contribute to their prison-like look and feel, and service users’ feelings of incarceration ().

I mean obviously we’re caged in. But it just makes the whole experience worse. (A_MH_F_NM_6)

Discussion

The key issues identified in this paper were elicited from interviews with staff, service users and family members, staying, visiting or working in four acute mental health units in New Zealand. The overarching finding was that despite the diversity of the facilities visited and participants interviewed, contemporary issues relevant to the design of acute mental health facilities were remarkably similar across the four case studies. We discuss these challenges below with an emphasis on how we might begin to address them if we are to keep the model of hospital-based acute mental health facilities.

Design that provides for cultural and spiritual needs and family/whānau visitors

Much work needs to be done to incorporate cultural and spiritual needs in the architectural design and the models of care, especially for Māori who are overrepresented amongst mental health service users. This should include careful consideration of how family and whānau can be appropriately accommodated (Marques et al. Citation2022a). This includes the redesign and greater allocation of space on units for improved whānau rooms to allow the family to stay connected to tangata whaiora, with provision for sharing kai/eating, sleeping, children and play space. Depending on the size of the facility and the number of the service user population, multiple whānau rooms may be required. Some initial guidance from the Ministry of Health in 2021 (Ministry of Health Citation2021) on how architects and planners might consider Kaupapa Māori concepts and spaces in the design of acute mental health facilities makes several relevant suggestions. For instance, consideration should be given to the inclusion of a whare whakatau—a formal welcoming space located at or adjacent to the facility entry (similar to that in Unit D) to accommodate culturally appropriate protocols around arrival and welcome, gathering, ceremonial events, treatment and activities, discharge and farewell. This is also important for outdoor spaces at the entrance and exit points, where welcoming and transitional spaces need to accommodate cultural protocols (McIntosh et al. Citation2021). As well, the Ministry of Health guidance suggests that the exterior facade of the units and interior design (entrances, corridors and main living spaces) incorporate Māori design in the form of wayfinding and expression of Māori narratives, principles and values.

Design for the provision of therapeutic outdoor spaces and access to nature

Increasingly, the importance of outdoor therapeutic environments is becoming evident (Ferrini Citation2003; Wilson Citation2003; Maluleke Citation2012; Paul Citation2017). Greater attention needs to be given to the unit external spaces, such as courtyards, in terms of dimension and design (Marques et al. Citation2022b). As seen in the findings of this study, there is a pressing need for these outdoor spaces to be fit for purpose. For this to occur, courtyard spaces need to provide for a range of outdoor activities, including walking, sitting, and contemplating, and should provide access to nature for the senses, real greenery, fresh air, and they must be smoke-free. As with whānau spaces, larger facilities will require more courtyard space. Attention to views of nature from indoor areas, especially from bedroom windows, will also add therapeutic value and align with cultural and therapeutic needs (Marques et al. Citation2021).

Design for the provision of meaningful activities

A lack of meaningful activities has been positively linked with deteriorating mental health (Clarke et al. Citation2018; Serowik and Orsillo Citation2019; Cruyt et al. Citation2021; Marques et al. Citation2022c), boredom and smoking (Jenkin et al. Citation2021b). To address this, greater consideration needs to be given to the inclusion of meaningful activities, which are culture, age and gender relevant, accommodating individual differences (Bird et al. Citation2014; Jenkin et al. Citation2021a) and have appropriate spaces to accommodate them.

Design for safety without compromising aesthetics and autonomy

The design also needs to better address the safety of staff, service users and visitors (Jenkin et al. Citation2022). Internally this may translate into the re-design of the staff stations and the physical barriers created by the fishbowl design that separates the staff from the service users. We note that the staff in Unit D were situated for most of their time in the shared open-plan space with service users (there was no fishbowl station), and that anecdotal evidence from this facility indicates this reconfiguration has strengthened relationships between staff and service users on the unit. Service users should also be provided with lockers to safely store their personal effects, and for their sense of safety and security, they should have key cards for securing their bedroom door. Unit D was the only facility where service users could independently lock their rooms, with staff being able to override these locks when necessary.

An aesthetically attractive environment, although historically seen as an extravagance rather than an essential feature of a healing environment (Shepley et al. Citation2016), is also critical to remedy the stigmatising aesthetic that characterises many mental health facilities. In the wake of the recent cognitive revolution, the combination of cognitive neuroscience and cognitive neuropsychology along with the spate of technological innovations now allows us to study the human brain and its functions with unprecedented insight and perception (Karakas and Yildiz Citation2020; Sussman and Hollander Citation2021). As a result, we have an ever-growing evidence base that shows how our experience of the built environment is much more significant than previously realised (Eberhard Citation2009; Mallgrave Citation2013, Citation2011; Robinson and Pallasmaa Citation2015). Our understanding of how human beings experience spaces and how our built environments directly affect our well-being is increasingly supported by science. We now know the substantial toll poor quality environments take on their users, telling occupants that their lives do not matter. We also now know how to create enriched environments that facilitate human connection, foster autonomy, hope, empowerment, optimism and support the (re) development of personal identity.

Design to mitigate stigma—improve public visibility, wayfinding and resource allocation

The stigma associated with mental health has meant many mental health service users don’t want to be seen or recognised (Knight and Moloney Citation2005). Perhaps partly because of this, mental health facilities are often hidden from public view, hard to locate, and when sited on a hospital campus may be poorly sign-posted. It is promising that new trends show greater attention to public visibility, facades and entrances and wayfinding (Lockett et al. Citation2021). However, despite mental illness being a major cause of disability globally (Afshin et al. Citation2019), institutional stigma has resulted in reduced resources for mental health care compared with other medical conditions, especially for already marginalised populations (Hatzenbuehler Citation2016). Unfortunately, this reality is reflected in inadequate mental health care facilities in terms of their location, allocated space, size and their dreary, inaesthetic design (Chrysikou Citation2017). The stigma of mental health extends into the work and business of mental health units, adversely impacting workforce retention and recruitment. For example, psychiatry is seen as less prestigious than other medical specialisations (Saxena et al. Citation2007; Monasterio et al. Citation2020; Lockett et al. Citation2021). To mitigate the stigma around mental illness, bold moves are required to address the resource shortfalls that characterise mental health care work, facilities and care provision. Attractive well-located facilities will go a long way to communicating care and social investment to improve the way society thinks about mental illness.

Strengths and limitations

This study was novel and possibly the first research study in Aotearoa New Zealand to go into acute mental health wards and interview service users. Its transdisciplinary nature also makes it highly original. Other major strengths of this study include the diverse case selection sampling strategy for selecting the four acute facilities across Aotearoa New Zealand, a large number of interviews (n = 96) conducted, the range of groups interviewed (this study included three participant groups, whereas most studies focus on one or two participant groups and thus typically exclude visiting family members), and triangulation of the views of all users of mental health units. Another key strength was that data were analysed by a transdisciplinary research team bringing together the disciplines of architecture, social science, psychiatry and lived experience of mental illness to identify and interpret the key themes. The illustration of these themes for the reader has been enhanced by the inclusion of photographs taken during this study.

Potential limitations of this study include the fact that staff participants were self-selected, as were service user participants after being screened by the lead clinician as well enough to participate. Some service users were also still quite unwell during interviews and occasionally their responses reflected this. We also acknowledge the important power differential between staff and service users on the unit, and that this will undoubtedly have impacted what service users shared with us. In hindsight, it might have been better to conduct service user interviews once they returned home and removed from this power dynamic. However, we were concerned about recall bias and wanted to understand the lived experience of being in the unit.

Another potential limitation is the low number of family participants involved in this study. Despite several methods of recruitment, this was a challenge we were unable to resolve. We can only speculate, as suggested by some of the staff, that the stigma of having a family member in a mental health facility was a deterrent to greater participation by family members.

In terms of generalisability, many of the findings of this study will resonate with staff, service users and visiting family members of acute mental health facilities around New Zealand, in similar jurisdictions, and perhaps also internationally.

Implications

If we are to continue with the provision of hospital-based acute mental health care facilities, then we face many challenges to improve or replace most of the current stock of such facilities in New Zealand because they are simply not fit for purpose.

Because there is a commonality of issues across the diverse designs, updated refined guidelines for design at the national level are necessary. These should be performance-based, stating how a building must perform for its intended use rather than describing how the building must be designed and constructed and provide flexibility for local variation. Against the backdrop of considerable new investment in the upgrading of existing facilities and the construction of entirely new units, such guidelines are imperative. As well, given that improved design of mental health units requires training of architects in the needs of building users, we have shared findings from this research with academic architects who will be training future students of architecture in the design of health care facilities.

Alongside the re-design of acute inpatient facilities, it is timely to consider what alternative models of mental health care are required to better serve the needs of mental health service users, their caregivers and the community. It is good news that the recent Government Budget announcement signalled significant public investment to the tune of NZ$27 million for community-based crisis services, such as residential and home-based crisis respite, community crisis teams and peer-led services in the community. As well, alternative models of temporary mental health accommodation have been emerging locally and internationally. New Zealand-based exemplars of temporary mental health care in the community include the Taranaki Retreat—a family-based crisis intervention service for individuals and their families in distress (Magill et al. Citation2021). There is also the NGO-funded peer-led acute residential Piri Pono in Auckland (Centre for Public Impact Citation2019), and some faith-based services have existed for a while (Beth-Shean Trust Citation2022). Additionally, Kaupapa Māori mental health community-based accommodation services have emerged providing more culturally aligned care than the current hospital-based mental health care models can provide.

Conclusion

Drawing on a novel and transdisciplinary programme of research to investigate the spatial and social milieu of adult acute mental health units in Aotearoa/New Zealand, this research identified key issues relevant to the planning and design of contemporary acute mental health units from in-depth interviews with those using the facilities. Contemporary issues included: the need to accommodate family/whānau visitors and more sensitively address cultural needs; the need for access to nature and fresh air, the need for more flexible spaces that can accommodate meaningful activities and better design for the safety of the mental health unit, and overall improved visibility of mental health facilities through improved situation/location within the hospital environment and wayfinding. Finally, much work needs to be done across multiple arenas to address the significant and deep-rooted stigma associated with mental health and alternative models of accommodation for people with mental illness in the community should be considered.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating DHBs and the participants who gave so generously of their time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, Mullany EC, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abebe Z, et al. 2019. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 393:1958–1972. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8.

- Bartlett P, Wright D. 1999. Outside the walls of the asylum: The history of care in the community 1750-2000, studies in psychical research. New Jersey: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Beth-Shean Trust. 2022. Crisis respite [WWW Document]. [accessed 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://bethsheantrust.org.nz/crisis-respite/.

- Bird V, Leamy M, Tew J, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. 2014. Fit for purpose? validation of a conceptual framework for personal recovery with current mental health consumers. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 48:644–653. doi:10.1177/0004867413520046.

- Centre for Public Impact. 2019. Piri Pono – a peer-led acute residential service in New Zealand [WWW Document]. [accessed 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/piri-pono-peer-led-acute-residential-service-new-zealand.

- Chrysikou E. 2014. Architecture for psychiatric environments and therapeutic spaces, EBSCO ebook academic collection. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Chrysikou E. 2017. The social invisibility of mental health facilities. London: UCL.

- Clarke V, Braun V. 2017. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. 12:297–298. doi:10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613.

- Clarke C, Stack C, Martin M. 2018. Lack of meaningful activity on acute physical hospital wards: older people’s experiences. Br J Occup Ther. 81:15–23. doi:10.1177/0308022617735047.

- Cruyt E, De Vriendt P, De Letter M, Vlerick P, Calders P, De Pauw R, Oostra K, Rodriguez-Bailón M, Szmalec A, Merchán-Baeza JA, et al. 2021. Meaningful activities during COVID-19 lockdown and association with mental health in Belgian adults. BMC Public Health. 21:622. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10673-4.

- Eberhard JP. 2009. Brain landscape: the coexistence of neuroscience and architecture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Edginton B. 1997. Moral architecture: the influence of the York Retreat on asylum design. Health Place. 3:91–99. doi:10.1016/S1353-8292(97)00003-8.

- Ferrini F. 2003. Horticultural therapy and its effect on people’s health. Adv Hortic Sci. 17:77–87.

- Foucault M. 1976. Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, 10/18. Paris: Gallimard.

- Galea S, Ahern J, Rudenstine S, Wallace Z, Vlahov D. 2005. Urban built environment and depression: a multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 59:822–827. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.033084.

- Gallagher M. 2017. From asylum to action in Scotland: the emergence of the Scottish Union of Mental Patients, 1971–2. Hist Psychiatry. 28:101–114. doi:10.1177/0957154X16678124.

- Hatzenbuehler ML. 2016. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 71:742–751. doi:10.1037/amp0000068.

- Houston RA. 2020. Asylums: the historical perspective before, during, and after. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:354–362. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30395-5.

- Jenkin G, McIntosh J, Every-Palmer S. 2021a. Fit for what purpose? exploring bicultural frameworks for the architectural design of acute mental health facilities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18:2343. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052343.

- Jenkin G, McIntosh J, Hoek J, Mala K, Paap H, Peterson D, Marques B, Every-Palmer S. 2021b. There’s no smoke without fire: smoking in smoke-free acute mental health wards. PLoS One. 16:e0259984. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259984.

- Jenkin G, Quigg S, Paap H, Cooney E, Peterson D, Every-Palmer S. 2022. Places of safety? fear and violence in acute mental health facilities: A large qualitative study of staff and service user perspectives. PLoS One. 17:e0266935. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0266935.

- Karakas T, Yildiz D. 2020. Exploring the influence of the built environment on human experience through a neuroscience approach: a systematic review. Front Archit Res. 9:236–247. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2019.10.005.

- Knight MTD, Moloney M. 2005. Anonymity or visibility? an investigation of stigma and community mental health team (CMHT) services using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). J Ment Health. 14:499–512. doi:10.1080/09638230500271329.

- Liddicoat S, Badcock P, Killackey E. 2020. Principles for designing the built environment of mental health services. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:915–920. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30038-9.

- Lockett H, Koning A, Lacey C, Every-Palmer S, Scott KM, Cunningham R, Dowell T, Smith L, Masters A, Culver A, Chambers S. 2021. Addressing structural discrimination: prioritising people with mental health and addiction issues during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Z Med J. 134:7.

- MacKinnon D, Coleborne C. 2003. Introduction: deinstitutionalisation in Australia and New Zealand. Health Hist. 5:1. doi:10.2307/40111450.

- Magill R, Collings S, Jenkin G. 2021. The provision of comprehensive crisis intervention by a charitable organisation: findings from a realist evaluation. Volunt Sect Rev. 1–19. doi:10.1332/204080521X16346520274134.

- Mair C, Roux AVD, Galea S. 2008. Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? a review of evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 62:940. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.066605.

- Mallgrave HF. 2011. The architect’s brain: neuroscience, creativity, and architecture. Dublin: Wiley.

- Mallgrave HF. 2013. Architecture and embodiment: the implications of the new sciences and humanities for design. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis.

- Maluleke M. 2012. Culture, tradition, custom, law and gender equality. Potchefstroom Electron Law J. 15. doi:10.4314/pelj.v15i1.1.

- Marques B, Freeman C, Carter L. 2022a. Adapting traditional healing values and beliefs into therapeutic cultural environments for health and well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19:426. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010426.

- Marques B, Freeman C, Carter L, Pedersen Zari M. 2021. Conceptualising therapeutic environments through culture, indigenous knowledge and landscape for health and well-being. Sustainability. 13:9125. doi:10.3390/su13169125.

- Marques B, McIntosh J, Muthuveerappan C, Herman K. 2022b. The importance of outdoor spaces during COVID-19 lockdown in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Sustainability. 14(12):7308–7318.

- Marques B, McIntosh J, Webber H. 2022c. Therapeutic landscapes: a natural weaving of culture, health and land. In: Ergen M., Bahri Ergen Y., editor. Landscape architecture framed from an environmental and ecological perspective. IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.99272.

- McIntosh J, Marques B, Cornwall J, Kershaw C, Mwipiko R. 2021. Therapeutic environments and the role of physiological factors in creating inclusive psychological and socio-cultural landscapes. Ageing Int. doi:10.1007/s12126-021-09452-8

- Ministry of Health. 2021. New Zealand health facility design guidance note PILOT DGN MH01: acute adult inpatient mental health facilities. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Monasterio E, Every-Palmer S, Norris J, Short J, Pillai K, Dean P, Foulds J. 2020. Mentally ill people in our prisons are suffering human rights violations. N Z Med J. 133:5.

- Patterson R, Durie M, Disley B, Tiatia-Seath S, Tualamali’i J. 2018. He Ara Oranga: report of the government inquiry into mental health and addiction. Auckland: University of Auckland.

- Paul J. 2017. Exploring Te Aranga design principles in Tāmaki. National Science Challenges Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities Ko ngā … .

- Pevsner N. 1976. A history of building types, A.W. Mellon lectures in the fine arts. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Robinson S, Pallasmaa J. 2015. Mind in architecture: neuroscience, embodiment, and the future of design. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press.

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. 2007. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet. 370:878–889. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2.

- Seawright J, Gerring J. 2008. Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Politi Res Quart. 61(2):294–308. doi:10.1177/1065912907313077

- Serowik KL, Orsillo SM. 2019. The relationship between substance use, experiential avoidance, and personally meaningful experiences. Subst Use Misuse. 54:1834–1844. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1618329.

- Shepley MM, Watson A, Pitts F, Garrity A, Spelman E, Kelkar J, Fronsman A. 2016. Mental and behavioral health environments: critical considerations for facility design. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 42:15–21. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.06.003.

- Sussman A, Hollander JB. 2021. Cognitive architecture: designing for how we respond to the built environment, 2nd ed. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003031543.

- Suzuki A. 1995. The politics and ideology of non-restraint: the case of the Hanwell asylum. Med. Hist. 39:1–17. doi:10.1017/S0025727300059457.

- Vavyli F. 1992. G4.15 planning and design issues for healthcare spaces: teaching notes.

- Weich S, Blanchard M, Prince M, Burton E, Erens B, Sproston K. 2002. Mental health and the built environment: cross-sectional survey of individual and contextual risk factors for depression. Br J Psychiatry. 180:428–433. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.5.428.

- Wilson K. 2003. Therapeutic landscapes and First Nations peoples: an exploration of culture, health and place. Health Place. 9:83–93. doi:10.1016/S1353-8292(02)00016-3.

- World Health Organization. 2015. The European mental health action plan 2013–2020. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Yohanna D. 2013. Deinstitutionalization of people with mental illness: causes and consequences. AMA J Ethics. 15:886–891. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.10.mhst1-1310.