ABSTRACT

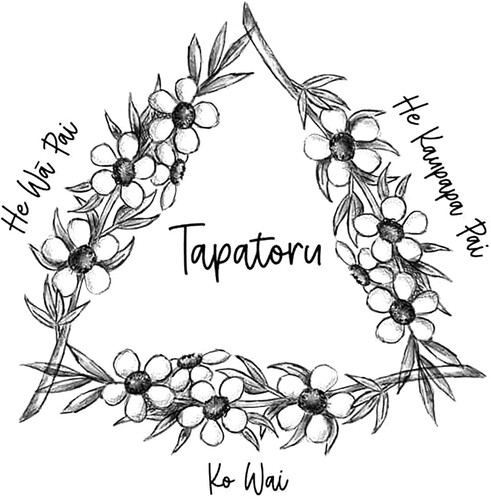

Whanaungatanga (nurturing of relationships) is at the heart of wellbeing for rangatahi (Māori youth), yet little research has considered how rangatahi understand and experience whanaungatanga. Furthermore, policy makers, organisations and practitioners have had limited guidance to reflect on whanaungatanga with young Māori in ways that support rangatahi wellbeing and aspirations. As part of a broader photo-elicitation project on whanaungatanga with young Māori, we describe Te Tapatoru, a model of whanaungatanga based on the experiences and insights of 51 rangatahi. Using a Māori critical realist approach, we demarcated rangatahi descriptions of whanaungatanga into three interconnected areas. The first component, ko wai, a reciprocal connection, emphasised the importance of a reciprocal connection with people (or more than people). The second component, he wā pai, a genuine time/place, spoke to how contexts, time and places provided the space for meaningful connections to take root and flourish. The final component, he kaupapa pai, a genuine kaupapa (activity, process) considered how rangatahi desired connection which responded to their desires and aspirations. This approach harnesses rangatahi potential by creating reciprocal and invigorating supportive environments based on rangatahi aspirations and insights. Policy and practice recommendations are made which centre this rangatahi informed approach to whanaungatanga.

Introduction

Whanaungatanga as a practice and value has increasingly been discussed within Māori research as a core part of who we are. Whanaungatanga has been described as the glue that brings Māori together (McNatty Citation2001) and the ‘basic cement that holds things Māori together’ (Ritchie Citation1992, p. 66). In practice, whanaungatanga is the nurturing of relationships, through care, connection, common understandings and shared obligations (Bishop et al. Citation2014). Rangatahi continue to emphasise the importance of whanaungatanga with whānau (extended family) in conditions of economic hardship, marginalisation and colonisation (Edwards et al. Citation2007; Groot et al. Citation2017; Hamley et al. Citation2021). Institutional racism foregrounds many challenges, enabling contexts of poverty and marginalisation (Borrell Citation2005; Reid et al. Citation2014), experiences of distress, and negative interactions with healthcare and education systems for rangatahi (Clark et al. Citation2011; Rata Citation2015). Despite the many socio-political and structural challenges rangatahi MāoriFootnote1 (Māori youth) face (Reid et al. Citation2014; Rata Citation2015), whanaungatanga continues to be associated with higher levels of wellbeing for young Māori (Clark et al. Citation2011; Williams et al. Citation2018; Greaves et al. Citation2021; Hamley et al. Citation2021). Thus for whānau, hapū (collection of shared whānau), iwi (collection of hapū) and broader Māori communities, whanaungatanga continue to contribute to rangatahi identity and wellbeing (Durie Citation2001; Le Grice et al. Citation2017).

The centrality of whanaungatanga aligns strongly with Māori models of wellbeing, which emphasise the importance of whānau, whanaungatanga and whakawhanaungatangaFootnote2 in providing a foundation for wellbeing (Pere and Nicholson Citation1997; Durie Citation2001; Wilson et al. Citation2021). This focus on relationships supporting wellbeing is also a consistent theme that weaves across more general youth development models both internationally (Bronfenbrenner Citation1995) and within Aotearoa New Zealand (hereafter Aotearoa) (Keelan Citation2001, Citation2014; Ware and Walsh-Tapiata Citation2010; Deane et al. Citation2019; Tuhaka and Zintl Citation2019). Whanaungatanga then has been positioned as central to supporting rangatahi wellbeing within the Aotearoa Youth Development literature (Ware Citation2009; Keelan Citation2014). Other academic disciplines have also emphasised the importance of whanaungatanga for rangatahi, including psychology (Pomare Citation2015; Le Grice et al. Citation2017), social work (Walsh-Mooney Citation2009), health (Durie Citation1997; Carlson et al. Citation2016), and education (Hall et al. Citation2013; Bishop et al. Citation2014; Webber and Macfarlane Citation2017; Webber Citation2020). Thus, whanaungatanga is increasingly discussed in a wide range of literature and policies as a vital process in practice to support the wellbeing of rangatahi. We (the authors), as researchers and practitioners, affirm this stance.

However, to our knowledge, there is minimal literature that has explored how to help nurture whanaungatanga for practitioners. Although there is substantive literature situating whanaungatanga as a central aspect of rangatahi wellbeing, little is available from rangatahi understandings of whanaungatanga, nor how this may be nuanced differently across life stages and generations. What literature is available to support practitioners consistently emphasises the importance of tikanga and mātauranga Māori as therapeutic tools which can enhance engagement, build trust and help address barriers for Māori whānau seeking support (Pomare Citation2015). Relationships in mental health care shape the confidence and willingness of Indigenous clients and families to engage with services (Isaacs et al. Citation2012; Hinton et al. Citation2015; Pomare Citation2015).

Yet, there remain challenges in articulating mātauranga and tikanga Māori within Eurocentric systems and policies (Ahenakew Citation2016; Hamley and Le Grice Citation2021). Translation of concepts in te reo Māori (the Māori language), in policy and practice, risk becoming diluted or erased through a lack of engaging with the deeper ways of being and knowing which underpin the concepts in te reo Māori (Mika Citation2016). Without any guidance about what comprises a meaningful and reciprocal practice of whanaungatanga, there is a risk of whanaungatanga being conflated with Eurocentric forms of rapport building (Cooper Citation2021).

While there are similarities in the intended outcomes of rapport building and (whaka)whanaungatanga, we envision the latter as a dynamic and ongoing engagement practice. Whanaungatanga requires practitioners to reflexively engage with the relational dynamics that better support Māori whānau, extending beyond an essentialised, one-size-fits-all idea of ‘being Māori’ (Lacey et al. Citation2011). The basis of establishing a connection through whanaungatanga is that this connection endures beyond short interventions. Once ties are made, they are always there ready to be nurtured. In summary, there is a need for research and practice to guide practitioners in building whanaungatanga with Māori, especially rangatahi.

As such, this article provides a guide for practitioners through developing Te Tapatoru model. This model centres rangatahi experiences of whanaungatanga to better articulate how to build whanaungatanga with rangatahi, and what systemic and policy changes may been needed to support this. Importantly, we want to offer a model that can guide practitioners, organisational policy, codes of practice, and services to consider how youth services can engage with rangatahi in ways that are informed by rangatahi perspectives. We hope through this process to expand understandings of whanaungatanga and develop considerations for broader system change, occurring through a focus on rangatahi insights.

Materials and methods

This research draws from a Health Research Council Kaupapa Māori funded project, ‘Harnessing the Spark of Life’, that explores how whanaungatanga supports rangatahi wellbeing. Kaupapa Māori research centres Māori ways of knowing and being as the foundations for the research questions, approach, analysis, and outcomes, alongside an agenda for Māori self-determination, of Māori being Māori, and living in health and prosperity (Walker et al. Citation2006). The broader project aims to explore the potential for mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge, culture, values and worldview; Hikuroa Citation2017) to strengthen positive social, health and educational outcomes for rangatahi. Ethical guidelines for Indigenous research were engaged with (Smith Citation2006) and approval was obtained from The University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Reference number 020085).

Participants

We draw on interviews with 51 rangatahi aged 12–22 years. This included 34 rangatahi wāhine (young women), 16 rangatahi tāne (young men), and 1 young person who did not disclose their gender. Rangatahi were from across the Aotearoa regions of: Te Tai Tokerau (Northland), Tāmaki-Makaurau (Auckland) and Waikato. Most (28) lived in rural areas, 17 in urban areas, and six in semi-rural areas. The majority were in intermediate and secondary education (42), with three in tertiary education, and six not in education. Recruitment focused on rangatahi who were doing well in their lives to highlight their accounts of how whanaungatanga supported rangatahi to flourish.

Five wāhine Māori researchers conducted the recruitment and interviewing process. Researchers travelled to meet the young person at a location of their choice: often at a whānau home, or a community location such as a school or community centre. Each used existing networks to recruit participants with the aid of partner organisations (schools and youth organisations), which align with a kaupapa Māori approach, highlighting the relational nature of research with Māori communities (Walker et al. Citation2006). Researchers gave participants a portable electronic tablet as a koha (an offering for their contribution) they could also use to take photos to illustrate what whanaungatanga means to them and how it supports their wellbeing. A video including instructions about the photo-elicitation task were provided on the tablets. This video highlighted that we (the researchers) were interested in rangatahi insights into specific practices of whanaungatanga that support the wellbeing of rangatahi and their whānau. Specifically, the video asked that they take photos that highlighted their understandings of whanaungatanga, that they could then bring to the photo-elicitation interviews.

Each researcher met with the young person and whānau at least twice: first, to build relationships, share kai, and provide the tablet; the second acted as the interview. Whānau could opt to be involved with the interview process if they chose, and 26 rangatahi interviews had whānau present. This included parents, siblings, grandparents, cousins aunts and uncles across the interviews. There was a rich narrative added by whanau hearing rangatahi persectives, with whānau expanding on the stories of rangatahi.

Photo-elicitation is widely recognised for bringing perspectives of minoritised groups to the fore and facilitating social change (Harper Citation2002; Groot et al. Citation2017; Vandenburg et al. Citation2021). Rangatahi led the photo-elicitation interviews with the images they produced to direct researcher attention to specific issues regarding their understandings of whanaungatanga. This process discussed in turn the different photos rangatahi had taken and how these photos highlighted whanaungatanga for the rangatahi. Rangatahi on average took twenty photos, with the fewest number of photos taken being nine, and the highest being fifty-one. Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed. Names and specifying information have been pseudonymised. Photos included in this analysis have also been digitally modified to preserve anonymity. Consent was sought for any quoted material or photos used in publications.

Model creation and analytic methods

The model creation began with the first author engaging with the different photos and descriptions of whanaungatanga that were storied by rangatahi and whānau. This engagement was guided by a Māori social constructionist epistemology and Māori critical realist ontology (see Le Grice Citation2014) under a broader conceptual frame and tradition of Kaupapa Māori (Pihama et al. Citation2002) and qualitative research (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2018). Social constructionist epistemologies attend to participant descriptions of their lives and ideas about the world, to explore how knowledge and experience are dynamically shaped by historically and culturally situated social formations. When paired with a critical realist ontology, researchers regard participant experiences as real and valid yet also seek to draw out the contextual specificity and multiplicity of participant experiences (Willig Citation1999).

A Māori critical realist ontology provides researchers with a way of attending to, articulating, and highlighting distinctly Māori ways of being that are imbued in Māori language, and informed by Māori culture; but acknowledging that may be shaped and constrained by the colonial context. Through this initial analysis, the first author identified a consistent pattern across rangatahi photos and interview transcripts. Primarily, intergenerational support, meaningful places, and resonant activities became co-constitutive aspects of what rangatahi described as meaningful whanaungatanga.

This initial analysis was then presented to the broader research group of 10 Māori academics and practitioners during a two-day wānanga (research group forum) centred on creating a rangatahi health model. Across this wānanga, the research group decided to shift the focus to creating a model of whanaungatanga based on the first author’s initial ideas about inter-generational support, meaningful places, and resonant activities. Additional potential components were considered to include within the model, however, it was decided at the conclusion of the wānanga that a three-component model held the most potential for implementation in practice and policy.

Through collaborative engagement, areas of interest were refined into the final model of whanaungatanga, Te Tapatoru, that is the focus on this article. This included two writing retreats where the research team ensured the model resonated across the full dataset of rangatahi photos and interviews, and could respond to the diversity of rangatahi within the dataset. This process also highlighted a particularly salient photo and narrative from one rangatahi wāhine that now informs the introduction to the model. When selecting accounts to highlight components of the model, participants have been provided with pseudonyms to preserve their confidentiality. The model has been shared with Māori health colleagues, academics and young people – it’s simplicity and centreing of Indigenous knowledge seems to resonate with them.

Notes on the model

Before we outline this model, we feel it important to preface two interconnected notes. Firstly, this model sets up some of the conditions which can support whanaungatanga. It is not intended to be a complete picture of whanaungatanga for rangatahi: three components will never capture the complexity of whanaungatanga for all Māori. The model draws on insights from Te Ao Māori (the Māori world) but seeks to respond to rangatahi aspirations, and how practitioners can practically engage in whanaungatanga with them. We hope the model serves as a flexible and practical guide for practitioners, organisations developing youth services, funders and planners and policymakers to think about a more expansive approach to conceptualising whanaungatanga, instead of the best way of doing so.

Secondly, rangatahi are embedded within complex and diverse realities (Borrell Citation2005; Kukutai and Webber Citation2017). Colonisation and urbanisation have led to varied expressions of rangatahi and whānau identity: there is no fixed concept of what it means to be a rangatahi (Cram and Vivienne Citation2010). Thus, a core challenge was ensuring that the model is not read as a template to uncritically follow when engaging a process of whanaungatanga with all young Māori. We see the solution to this as similar to recommendations made by Pitama et al. (Citation2007), who urged practitioners to centre clients’ experiences of their identity over and above predominant assumptions of what Māori culture ‘is’. Any engagement with the model must engage with this complexity of Māori identities and practitioners can fluidly respond to the needs and aspirations of rangatahi.

Results

The Tapatoru model

Three components (described fully below): ko wai, a reciprocal connection, he wā pai, a genuine time and place, and he kaupapa pai, a genuine kaupapa (topic). These form three sides of a tapatoru (triangle). The triangulation of these components in our model is tangibly illustrated by Pania, a seventeen year old wāhine, who grew up in rural Northland. During her interview she shared a tapatoru symbol she created with her two closest friends, Kahukura and Manu ().

The tapatoru was a symbol of their relationship and enduring whanaungatanga. Pania described difficulties in one particular class at school and how Kahukura had immediately come to her house to support her. This reciprocal connection meant a lot to her in a time of need. The tapatoru spatially connects Pania to where she grew up and had whakapapa (ancestral connections) to, as Kahukura and Manu’s three houses formed a triangle filled with places, people and memories that were important to her. Finally, Pania described various shared interests with Kahukura and Manu: time on school trips, hanging on the field, and being together. She described the strength this provides for her while at school where she is not scared to be someone like I can be myself cause I’ve known them my whole life growing up. Pania’s account encapsulates the possibilities that can occur when recognising the importance of people, time and place, and kaupapa in creating contexts that enable rangatahi to flourish. We now provide more in-depth descriptions of each part of the model and recommendations for incorporating these insights into policy and practice to support rangatahi wellbeing.

Ko wai? A reciprocal connection

This first component of this model describes the centrality of rangatahi connections to whānau, communities and places. Traditionally, rangatahi and tamariki (children) are viewed as the central element of whānau, nestled within complex networks of whanaungatanga with elders (Pihama et al. Citation2015). With relevance to our conceptual model, intergenerational support provided rangatahi with scaffolded skills and support as they developed and grew (Marsh et al., in preparation). This was illustrated in rangatahi narratives about their everyday lives, including Heremaia, who reflected on a photo to describe how whānau meaningfully cultivated contexts where new skills and talents could be embraced.

“Heremaia: So I’m really into cooking and I think a few weeks back, I was making pancakes. Like, I’m really into cooking, it’s really fun … Last night I cooked dinner for my aunty and my cousin coz these guys were all at dinner, at the graduation of my brother.

Interviewer: Oh yep, where do you think … how did that start?

Heremaia: Mum does a lot of baking, I just liked helping. And then, I used to just like cooking just eggs and not even eating it. Coz I started cooking in Australia. Uncle taught me how to cook scrambled eggs.” (Heremaia, 12, tāne, urban)

Heremaia describes their joy in preparing meals for his whānau, referencing particular occasions where he has been able to learn, assist and share his talents. Further research has also illustrated how rangatahi connections to the broader whānau are essential to development and wellbeing (Clark et al. Citation2011; M. H. Moeke-Pickering Citation1996; Durie Citation1997; Edwards et al. Citation2007; Le Grice et al. Citation2017). Other rangatahi identified non-familial mentors and support people who had an important role in their lives, in cultivating their talents and facilitating their wellbeing. These included teachers, coaches, neighbours, tutors, and tohunga (people with expertise in an area) who were influential in their lives, and friends (as in the first narrative of Pania) with whom rangatahi shared experiences and reciprocal connections. Thus, similar to other research with young Māori (Clark et al. Citation2011; S. Edwards et al. Citation2007), both whakapapa whānau (whānau connected by shared genealogy) and kaupapa whānau (whānau connected by a shared purpose/interest) resonated with rangatahi.

Equally, many rangatahi also extended experiences of whanaungatanga beyond human relationships, to include atua (sacred and revered being), whenua (land), moana (a large body of water), awa (river) and maunga (mountain). This component therefore also can include the relationality many Māori have to the environment, as a living and deeply connected part of their networks of whakapapa relationships (Boulton et al. Citation2021; J. Graham Citation2005; Roberts Citation2013; Le Grice et al. Citation2017; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor Citation2019).

“Rahiri: Then this picture here is my friend in the bush and I thought this was just so beautiful seeing Papa [Papatūānuku – the Māori god associated with the Earth]Footnote3 thrive in this sense. Just being able to see papa thrive is just like a beautiful thing, just embracing her, walking in her presence and walking in Tāne Māhuta’s [the Māori god associated with the forest] presence. Not like walking on a track that has been designated for [anyone] … just being able to embrace it all, embrace the taiao [the environment].” (Rahiri, 20, tāne, urban)

This participant reflects on a deeply spiritual moment of re-storing hauora for some rangatahi, where connecting to ngā Atua Māori (Māori Gods) as parts of the land (such as Papatūānuku and Tāne Māhuta) enabled them to be well. Equally, this account highlights the reciprocal nature of wellbeing through whanaungatanga. These connections provided support and opportunities to reflect and re-centre during challenging times, which can facilitate a deeper appreciation for te taiao and its richness. The physical environment (i.e. ngāhere, awa, moana, maunga) has deeply associated narratives relating to Māori ancestors and important histories which occurred there (Lee-Morgan Citation2019): in seeing Papa(tuanuku) thrive, Rahiri was able to also experience a heightened sense of joy and connection in a way which moved beyond aesthetic pleasure or a one-way engagement, to a reciprocal relationship of respect.

Relevance to policy and practice

Ko wai, a reciprocal connection, emphasises the importance for policy and practice to recognise rangatahi as nurtured within reciprocal relationships. Our model echoes research exploring youth development, which asserts that whānau contexts are crucial to youth wellbeing (Bronfenbrenner Citation1995; Keelan Citation2014; Deane et al. Citation2019). Equally, this emphasis on recognising rangatahi as nourished by reciprocal relationships resonates with other research which asserts that rangatahi wellbeing is embedded within whānau and community wellbeing (Durie Citation1997; Kara et al. Citation2011; Pihama et al. Citation2015).

Importantly, the insights of rangatahi further extend on Eurocentric approaches that emphasise family in youth development, to shift beyond just those who would be considered biological (nuclear) whanau to include a wide variety of elders, ancestors and atua/environments which support them. Rangatahi insights highlighted diverse networks of people who supported their wellbeing through practices like shared cooking, cultural practices such as mau rākau (Māori weaponry), waka ama (traditional outrigger canoeing), kapa haka (Māori performing arts), manu kōrero (a Māori speech contest held for secondary school students), farming, hunting, sports and an array of other activities. Rangatahi engaged in whanaungatanga with a wide array of people: whānau, tohunga (cultural experts), teachers, mentors and community leaders. This practice of rangatahi whanaungatanga in turn supported rangatahi wellbeing through having a strong network of elders/adults who could nurture them.

In particular these practices highlighted how whanaungatanga works best when rangatahi engage reciprocally with people to enable collective wellbeing or achievement of a goal. For practitioners, exploring with rangatahi the reciprocal relationships that matter to them, and how they can be involved in supporting wellbeing, is an important implication. In particular, this may involve thinking about how particular tīpuna (ancestors) or Atua Māori may be involved in this process as well as usual support systems. This perspective presents an essential and often unconsidered layer of whanaungatanga to explore to foster wellbeing for rangatahi.

For policymakers, we assert that work with rangatahi must clearly outline how practice and resourcing is informed by an approach to rangatahi wellbeing which reflects this interconnected sense of self. Policy that supports mātauranga Māori as a core component of working with rangatahi to resource Indigenous modes of healing must be prioritised. This could look like, for example, engaging with Mahi a Atua (Rangihuna et al. Citation2018) to explore how Atua Māori can support flourishing. Equally, organisational policy may need to be expanded to reflect the people who rangatahi have alongside them in journeys of wellbeing, and employ Māori who are able to draw on this Indigenous expertise.

(2) He wā pai, a genuine time and place

The second component of the model explores the ways in which time and place are connected to whanaungatanga. Māori scholars have written about the interconnections of space–time within Māori ways of knowing and being, captured by the concept of wā (Paewai Citation2013; Mika Citation2015). For this model, we (the researchers) are therefore using wā to stimulate thought about how honouring time and place can support or constrain whanaungatanga with rangatahi and their whānau. Connection to place for Māori is well documented across research which emphasises the importance of tūrangawaewae (a place to stand informed by whakapapa), and how attachment to places through whakapapa are captured in interrelated sets of practices, thoughts and relationships (Teddy et al. Citation2008; King Citation2019; Boulton et al. Citation2021; Hamley et al. Citation2021). Similarly, a Māori view of time emphasises relationality between past, present and future, encouraging intergenerational thinking and relationship building (Burgess and Painting Citation2020). Moana Jackson (Citation2013) describes this perception as a view where ‘time turns back on itself in order to bring the past into the present and then into the future’ (pg. 59), emphasising the interconnectedness of people, places and events within time and whakapapa. Thus, Māori conceptualisations of time and place exist in relation to whakapapa, and the sense of intergenerational connection and reciprocity.

However, in contemporary times, colonisation and neoliberalism have tried to reshape Māori connections to place and time. In particular, colonial and neoliberal practices have attempted to disrupt Māori connection to place (and vice-versa) through the erasure of Māori histories embedded within the physical environment, to enable it to be available for settler-colonialism and production of capital (Kidman Citation2012; Pihama et al. Citation2014; Kidman et al. Citation2021). Similarly, colonisation and neoliberalism have reconfigured our relationship to time to prioritise productivity, efficiency, and control over relationality which supports wellbeing (Sugarman and Thrift Citation2020). Together, these shifts in time and place have constructed systems which constrain the ability for Māori to engage in whanaungatanga, and to live well lives (Bennett and Liu Citation2018; R. Reid et al. Citation2014; Graham and Masters-Awatere Citation2020). Thus, within a socio-cultural context of colonisation and neoliberalism, there are serious obstacles for Māori to engage in our ways of understanding time and place. This challenge has been highlighted by Māori across a range of systems and organisations (Mooney Citation2013; Berryman et al. Citation2017; Bennett and Liu Citation2018; Came et al. Citation2019).

Despite these challenges, rangatahi accounts emphasised the importance of a genuine time and place in fostering whanaungatanga and wellbeing. One rangatahi, Kimiora, included photos of a whānau walk around his community which represented an important experience of whanaungatanga with his whānau .

“Kimiora: This photo is when our family planned to go for a walk around our community and we really encouraged my Dad and sister and brothers to come for a walk and spend some family time.

Interviewer: Did they want to? Did they want to walk?

Hera, Kimiora’s mum: It’s just our way of encouraging them to ‘cos my husband’s got diabetes and my sister-in-law had diabetes but she’s now off it. So it was all about hauora and, you know, doing it together as a whānau.

Kimiora: Summertime’s a big time, like we play basketball or anything. Beach, walks around the basin, yeah.” (Kimiora, high school aged tāne, urban)

Exploring the meaning of a photo that showed a family walk, elicited further discussion about whānau hauora and taking time ‘whenever we can’ to be outdoors and be active together. This cultivated a more expansive notion of time – beyond a carefully scheduled practice – to instead articulate a flexible approach to time that supported whānau wellbeing in constrained circumstances. Although there are hints of the impacts of neoliberalism and colonisation on whānau hauora, collectively they have come together to look after one another. Equally, the suburb where their extended family all lived, was a place which was layered with memories. Despite the displacing impact of government housing policies and the gentrification of their area, the whānau has been able to secure housing there again, and were able to continue their practice of whanaungatanga with people and place. This importance of time and place echoes across various accounts. Rangatahi described the time spent doing everyday practices of whanaungatanga: being picked up from after-school activities, cooking together, playing games, or going for walks together highlighted how time spent together mattered. The reliability and ongoing nature of reciprocal relationships for rangatahi helped to foster wellbeing for rangatahi and whānau.

Rangatahi also highlighted how a variety of different places (i.e. awa, moana, maunga, schools, local community spaces, churches) could facilitate whanaungatanga. Schnell and Mishal (Citation2008) stated that places can act as powerful nurturers of identity for rangatahi, shaping and forming their identities as cultural agents. The marae (a Māori cultural complex connected to specific whānau, hapū and iwi) was one space where place-based identities were embedded within networks of whanaungatanga, enacted through time spent looking after the marae and reciprocally being looked after as well (Adds et al. Citation2011). Schools were another important space that created whanaungatanga, particularly through class trips such as for Ngā Manu Kōrero, kapa haka, school camps and different national competitions. Churches and spiritual spaces (including youth groups) provided another opportunity for creating a space that facilitated whanaungatanga. Some spaces made rangatahi feel comfortable and safe, and enabled them to explore different parts of their identity collectively.

Many rangatahi notably described how whanaungatanga could be facilitated by the taiao (environment). Participants spoke to the role of place and time within the taiao as formative within the context of whanaungatanga – being on the moana or awa as part of doing waka ama, being on the maunga while hiking with youth groups, or appreciating the distinctiveness of whenua while travelling and exploring overseas. Paraone described how the ngāhere (forest) played a key role within his leadership role in a rangatahi group.

“Interviewer: Very important mahi. Restoring mauri (vitality and wellbeing) into the whenua (land) aye? The awa me te whenua (the river and the land).

Paraone: We always go into the realm of Tāne (atua of the forest) and take rākau (sticks) for mau rākau purposes. This is another way of us giving back. You give and you take. You don’t just take, take, take and all those moumou korero (phrases). (Interviewer: The balance you were talking about i te ao Māori (in the Māori world)) Yeah. Maintaining te mauri o te ngahere (the vitality and wellbeing of the forest). All those things”. (Paraone, 22, tāne, rural)

Here, Paraone described taking a rangatahi group to the ngāhere to collect the rākau needed for mau rākau. Paraone illustrated how this enabled rangatahi to appreciate the vitality of the forest and how they were responsible to engage reciprocally with the forest and with one another. This kaupapa also took place across several days, where the group would stay in the ngāhere, learn stories about it and the relationships the ngāhere has with their community. As such, the kaupapa was afforded both the time and the place to enable the group to come together and learn skills they needed for mau rākau. This improved the whanaungatanga within the group and with the ngāhere, as well as enabling them to develop skills as a group relating to mau rākau.

Relevance for policy and practice

Threaded across all these accounts was a recognition of how particular places and the provision of time create enhanced possibilities for whanaungatanga. In particular, being outdoors, in the environment, and spending considered time with people help to foster whanaungatanga. However, the ongoing neoliberal structuring of time/place that emphasises productivity and is so often premised on efficiency, constrains the possibilities for engaging with places and time in a way that supports whanaungatanga (Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021). Services within Aotearoa require bold restructuring to enable whanaungatanga to flourish within Indigenous understandings of time and space (Smith Citation1999; Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021). The insistence on appointments within an allocated time (when professionals have an appointment available), within office walls (clinics, processes and people that rangatahi do not know), and with referral-based agendas (often based on risk, deficits and problems requiring specific outputs) are in opposition to rangatahi accounts of the contexts that nurture their wellbeing.

There are many practitioners that dedicate time and effort to engaging with whānau in community and outside of regular work times (see Pomare Citation2015 Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021;, for examples). However, policy and structures need to create possibilities for whanaungatanga to flourish by negotiating time and place with rangatahi and their whānau, while resourcing practitioners to do this crucial work without sacrificing their wellbeing. This can enable stronger whanaungatanga with rangatahi (Carlson et al. Citation2016) and enable staff to be responsive to the needs of rangatahi without having this work be unrecognised and undervalued. Being flexible and responsive to the needs of rangatahi and whānau indicates an appreciation for the relationship and can be an important element of building whanaungatanga.

Another important consideration for organisational policy and practice is the recognition that sometimes it is not the right time to have a particular conversation around a topic which may be viewed as time-sensitive. Space needs to be afforded to whanaungatanga and how this relationality can enable this conversation to occur when the time is right. When time, effort and resourcing is put into developing meaningful relationships these enable positive engagements with rangatahi. This could include non-Māori practitioners building relationships with Māori communities, iwi, hapū and whānau, alongside Māori practitioners (Isaacs et al. Citation2012; Hinton et al. Citation2015).

Alongside these considerations, there is ample space for practitioners and organisations to think about possibilities for practice within a culturally suitable environment. Isaacs et al. (Citation2012), highlighted that Indigenous clients and families felt more optimistic about their service engagement when assessments and interventions occurred in an environment that reflected their worldview. Connection to whenua can give rise to different practices than those of clinical settings or even community-based centres. In particular, being outside can activate different senses and experiences in contrast to dominant spaces of confinement. In particular, practitioners can take an active interest in areas where rangatahi have whakapapa connections. These often have specific environmental markers that resonate with rangatahi and may include stories associated with their ancestors and whānau. As such, these spaces provide opportunities to connect with rangatahi meaningfully. Spaces of this kind can open up new ways of exploring connections and interests to enable whanaungatanga.

(3) He kaupapa pai, a genuine kaupapa

This final component of the whanaungatanga model relates to the different kaupapa (practices/activities) that enable whanaungatanga. In particular, we emphasise the importance of kaupapa which are rangatahi-led and centre their interests, aspirations and potential. Research published about rangatahi often focuses on their disparities in relation to other youth in Aotearoa (see Berryman et al. Citation2017; Henwood et al. Citation2018; Hamley and Le Grice Citation2021, for discussions of this). More broadly, Māori have often been positioned as inherently lacking, inadequate or requiring Eurocentric interventions (Groot et al. Citation2018). Ironically, many of these inequities Māori face stem from colonisation and neoliberalism, which are both rooted in particular forms of Eurocentrism that are now embedded within systems in Aotearoa. Subsequently, Māori must navigate a context of policy and practice where the strengths, knowledge frameworks, histories, capacities, and solutions that Māori have are often absent or ignored (Groot et al. Citation2011, Citation2018; Le Grice Citation2014; Pomare Citation2015; Came et al. Citation2019).

However, rangatahi in their accounts of themselves, their whānau and their communities emphasised lives filled with skills, wisdom and joy. In particular, rangatahi highlighted an array of customary practices like kapa haka and or helping on the marae or contemporary practices like sports, pig hunting, or baking as kaupapa which enabled them to contribute to the collective. Tied to these accounts were admiration and affection towards people who had reciprocally engaged with them in these kaupapa like older siblings, parents, coaches, and members of their marae. Rangatahi also discussed other more informal practices like board and card games, shared kai, or driving places which also helped create whanaungatanga between rangatahi and those around them. Whanaungatanga could also be generated through smaller and more intimate moments, such as sharing a cup of tea, watching movies, and hanging out together. What threaded through all of these different practices was the way in which they resonated with rangatahi.

Anaru spoke of his passion for Māori customary practices and how these had been fostered by his whānau and his teacher, Matua Ruwhiu :

“Anaru: So (photo) number 8 was the whaikōrero (formal speechmaking), which brings me back to [Ngā] Manu Kōrero, and how te ao Māori (the Māori world), te reo Māori (the Māori language) are just flowing within me. Just yeah, whaikōrero is just another one of my passions I love doing. Whenever I get the chance I am just trying to improve my kōrero skills.

Interviewer: Yup, who taught you how to do whaikōrero and tauparapara (formal introduction of a speech) and things?

Anaru: Matua Ruwhiu he helped me a lot when it came to the kōrero side of it, when it came to the way you present yourself, he was a really big inspiration, a really big impact on that”. (Anaru, 13, tāne, rural)

Anaru in this account highlights how his relationship with Matua Ruwhiu is informed by their shared passion for te ao Māori, te reo Māori and whaikōrero. Matua Ruwhiu, as a teacher and mentor has been able to provide inspiration, knowledge, and support to help Anaru grow in this space. In turn, Anaru has been able to help Matua Ruwhiu in supporting younger students who are learning whaikōrero. This framing emphasises a central need to engage in the needs and aspirations of rangatahi through whanaungatanga in a way which highlights their strengths and potentiality.

Relevance for practice and policy

Rangatahi and their whānau are often anxious, afraid, or unsure of what to expect during clinical interactions. Practitioners should engage whānau around a kaupapa that makes sense to them, is familiar, and enables whānau and rangatahi to have some self-determination (Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021). Mooney (Citation2013) discussed the need for a clear kaupapa for successful engagements with rangatahi where rangatahi and their whānau have agency about what is being discussed (alongside at what time, at what place and with whom).

Further, while formalised practices of whanaungatanga like mihimihi, whakatau, pōwhiri (various Māori practices used to bring people together) and pepehā (a stylised introduction often centred around whakapapa/geographic relationships) are important, they are not the only ways of building whanaungatanga. Informal moments of connection also create ample possibilities for whanaungatanga, especially when outside the constraints of time/place within a service. In particular, there is room to consider more expansive creative practice to foster whanaungatanga – using different modes and ways of engaging with rangatahi beyond the dominant forms of engaging with people in therapeutic contexts (Ware and Walsh-Tapiata Citation2010; Fanian et al. Citation2015). While mātauranga Māori is anchored to the past by te reo Māori, it is also re-created and re-produced in flux with a dynamic and ever-changing sociocultural context. Engaging with genuine kaupapa enables a flexible reworking of established therapeutic practices, can present opportunities to foster better whanaungatanga and creatively re-imagine what qualifies as best practice.

Important too, is also making room for rangatahi to highlight where they are going well. Holding space for rangatahi to bring their kaupapa, show off their skills, or develop themselves further, can help foster whanaungatanga and highlight possibilities for practitioners to learn from rangatahi through ako (reciprocal teaching and learning). Durie (Citation2001) reminded researchers and practitioners to move beyond simply exploring what is going wrong to shifting to a consideration of what is going right. These areas of strength are important levers for intervention and engagement. Practitioners need to think carefully about the kaupapa they choose to engage with rangatahi, and how these can foster a sense of rangatahi as filled with potential, skills and talents which can be engaged to support wellbeing.

Policy needs to affirm this shift away from deficits towards the potential of rangatahi and whānau. This approach to whanaungatanga recognises rangatahi for who they are beyond the problems they seek support for, and attends to their potential and possibility. Rangatahi have many talents both within te ao Māori and te ao Pākehā (the Western world/knowledge system) that can be brought into a practice space to inform engagement. Equally, policy and service-delivery outcomes may be different to whānau aspirations for their rangatahi. Therefore, policy and service deliverables which prioritise whānau outcomes, as opposed to dominant Western perspectives of ‘positive’ outcomes. For example, whānau aspirations may not be captured by easily captured output metrics. Rather that expecting the complexity of whānau realities to be captured by Western metrics, we require policy and service deliverables to be responsive to Māori realities.

Summary: Te Tapa Toru

Te Tapa Toru is a model of whanaungatanga that is informed by rangatahi preferences, realities and understandings. There are three interconnected areas, the first component, ko wai, a reciprocal connection, emphasises the importance of a reciprocal connection with people (or more than people). The second component, he wā pai, a genuine time/place, speaks to how contexts, time and places provided the space for meaningful connections to take root and flourish. The final component, he kaupapa pai, a genuine kaupapa, considers how rangatahi desire to connect which privileges their desires and aspirations. This approach harnesses rangatahi potential by creating reciprocal, and invigorating supportive environments based on centring rangatahi aspirations and insights .

Discussion

Whanaungatanga is about looking after and respecting people (Durie Citation1997; Pere and Nicholson Citation1997). This process needs to be contextually responsive, reflecting on how people (atua and tūpuna), time/place and different kaupapa contribute to building whanaungatanga with rangatahi. The accounts from rangatahi highlight how whanaungatanga is nurtured within rich networks of intergenerational support, the environment and practices that connect people. From these narratives, we have synthesised ko wai, he wā pai, and he kaupapa pai as a tapatoru model to inform whanaungatanga for practitioners. Whanaungatanga for rangatahi is dynamic and includes a wide array of ancestral and contemporary activities to nourish their wellbeing. This highlights the persistent importance of te ao Māori to rangatahi, while also recognising the fluidity with which rangatahi engage with cultural ways of being. This article serves as a wero (challenge) to practitioners and organisations to consider how services and systems can reorient to prioritise the insights of rangatahi.

Whanaungatanga is also connected to supporting rangatahi wellbeing (Mooney Citation2013). As such, we see this model as able to work in conjunction with Māori models of health to promote rangatahi flourishing (Durie Citation1984; Pere and Nicholson Citation1997; Pitama et al. Citation2007; Lacey et al. Citation2011). In terms of this integration, we see our model as supporting whanaungatanga with rangatahi, which can create the space necessary to explore and support wellbeing articulated in Māori models of health. This integrated and holistic approach is essential to providing appropriate Māori service across all systems and sectors in Aotearoa. We see our approach within Te Tapatoru as part of the broader reform needed to foster an integrative, rangatahi and whānau-centred approach to wellbeing, where Māori ways of knowing and being are integral to services of care.

Future research and limitations

We deliberately chose rangatahi Māori covering a wide age range (12–22 years) consistent with Indigenous understandings of this developmental period, ensuring diversity of experience was represented. The project also purposely recruited rangatahi who were flourishing in their lives to illustrate case studies of excellence rather than deficits for rangatahi Māori. As such, we recognise there may be contexts in which safety considerations and developmental needs must take priority when working with rangatahi (for example, in emergency rooms or crisis teams) and Te Tapa Toru may not be easily implemented. Nevertheless, we argue that whanaungatanga and relationships should be prioritised to the fullest extent possible given the body of literature showing the connections between whanaungatanga, wellbeing and rangatahi and whānau success (M. H. Durie Citation1997; Clark et al. Citation2011; Curtis et al. Citation2015; Pomare Citation2015; Carlson et al. Citation2016; Bryers et al. Citation2021; Greaves et al. Citation2021). Further, the underpinnings of Te Tapatoru are aligned with the calls of Māori who work in (mental) health services to support rangatahi wellbeing through an integrated and holistic approach to care (Bennett and Liu Citation2018; Came et al. Citation2019; M. H. Durie Citation1997; Pomare Citation2015; Waitoki Citation2016; NiaNia et al. Citation2017; Wilson et al. Citation2021).

Future work is required to explore implementation of Te Tapa Toru into practice and whether the model is acceptable to rangatahi Māori. Work is also needed to explore how to build whanaungatanga with rangatahi who have had negative experiences with organisations and systems of power. Many Māori are enmeshed within various colonial systems of harm, whether in the justice system, in state care, or coercive engagement in education or health (Mooney Citation2013; Henwood et al. Citation2018; Tupaea Citation2020). Many of these rangatahi may have a strong mistrust of services and practitioners or have experienced various forms of institutionalisation. A simplistic model of whanaungatanga may not contain the necessary complexity to support the needs of these rangatahi who have experienced this cruel edge of colonial harm. We see this work as a crucial future contribution to heal intergenerational trauma wrought by the Crown and a variety of Crown agencies and organisations.

One area of whanaungatanga that also requires further research relates to digitally-mediated whanaungatanga. Although our research focused on face-to-face relationships, with the proliferation of social media, online whanaungatanga has increased the possibility for whakapapa and kaupapa whānau to maintain connections across time and space (O’Carroll Citation2013; Waitoa Citation2013). Whanaungatanga in these contexts can create possibilities for resilience where Māori may be physically isolated from other Māori, and enables Māori to unite in collective action (Waitoa Citation2013). This online connection is crucial in the broader online contexts where Māori, especially young Māori, Māori women and takatāpui (Māori of diverse genders, sexualities and sex characteristics), experience higher rates of online abuse and harassment (Manaaki Collective Citation2021). Recognising the connections and divergences between in-person and online whanaungatanga may require different imaginings of the relationship between people, place/time and kaupapa.

Conclusions

Whanaungatanga is a dynamic, fluid and active process for young Māori (Bishop et al. Citation2014), an assertion affirmed by rangatahi narratives within our study. We have privileged rangatahi insights in conceptualising our model, and we hope this will inform practice in concrete and tangible ways. While whanaungatanga may seem like a complex process to grasp for the uninitiated, rangatahi illustrated how expressions of whanaungatanga were an everyday, mundane aspect of their lives. This was aptly summarised by Mikaere:

“Interviewer: When I told you to go take the photos of whanaungatanga or those practices that your whānau do that support you, how did you interpret that or how did you find meaning from that?

Mikaere: I just tried to take the ways they supported me in everyday life, rather than I guess one big action. Just do the things that they always do for me.

Interviewer: I suppose those little things are important, hey?

Mikaere: Yeah, they all add up.” (Mikaere, 17, tāne, rural)

Attending to everyday practices raises important considerations for whānau Māori, practitioners, services, funders and planners and policymakers alike. For whānau Māori, we hope this example provides reassurance that what rangatahi want is people who care and support them with small gestures of aroha (compassion and love) and manaakitanga (nurturing and care). For practitioners, rethinking the way that we engage with rangatahi Māori in ways that are centred on rangatahi needs, not ours, will require some radical changes in practice and service delivery. As services seek to make themselves more equitable and accessible for rangatahi Māori, moving beyond the confine of clinic walls and deficits/safety centred, time constrained consultations is urgently required. This is reinforced by the perspectives of Māori practitioners/youth workers who work with rangatahi, actively resisting mainstream/Western systems that constrict their holistic practices (Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021). Funders and policymakers must ensure that providers have the resources, training and ability to work innovatively, and can report on outcomes that matter to rangatahi and their whānau. Through attending to the relational lives of rangatahi, a greater sense of who rangatahi are as people with skills, talents, and aspirations beyond their problems can be gained.

In this way, policy transformation must be rangatahi and whānau-centred. It further must be underpinned by Te Tiriti o Waitangi, with Māori self-determination being central to the driving system-level transformations that can enable equity for Māori. Western mainstream services are resistant to change, and policies that seek to increase Indigenous decision-making and divest power away from Western norms are often positioned as ‘idealistic’ or ‘divisive’ (Lindsay Latimer et al. Citation2021). However, there is a clear need and desire for policy and practice to change to be response to rangatahi. Through privileging whanaungatanga within care, we hope that practitioners, funders, policymakers and organisations will be able to flexibly adapt their practices to support the wellbeing of rangatahi, their whānau and their communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Rangatahi Māori refers to the developmental stage between childhood and adulthood. For the purposes of this paper, this is defined as 12–22 years, however we acknowledge there is great variability in Indigenous understandings of this period.

2 Whakawhanaungatanga is sometimes used to describe the establishment of relationships. We want to emphasise whanaungatanga as an ongoing relational process.

3 Square brackets have been used to denote when the authors have explained Māori language terms or to modify a quote to preserve confidentiality.

References

- Adds P, Hall M, Higgins R, Higgins TR. 2011. Ask the posts of our house: using cultural spaces to encourage quality learning in higher education. Teach High Educ. 16(5):541–551. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.570440.

- Ahenakew C. 2016. Grafting indigenous ways of knowing onto non-indigenous ways of being: the (underestimated) challenges of a decolonial imagination. Int Rev Qual Res. 9(3):323–340. doi:10.1525/irqr.2016.9.3.323.

- Bennett ST, Liu JH. 2018. Historical trajectories for reclaiming an indigenous identity in mental health interventions for Aotearoa/New Zealand—Māori values, biculturalism, and multiculturalism. Int J Intercult Relat. 62:93–102. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.05.005.

- Berryman M, Eley E, Copeland D. 2017. Listening and learning from rangatahi maori: the voices of maori youth. Crit Quest Educ. 8(4):476–494.

- Bishop R, Berryman M, Wearmouth J. 2014. Te Kotahitanga: effective education reform for indigenous and minoritised students. Wellington: NZCER Press. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/te-kotahitanga.

- Borrell B. 2005. Living in the city ain’t so bad: cultural diversity of South Auckland rangatahi: a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of a Masters of Philosophy in Psychology [master's thesis]. Auckland New Zealand: Massey University.

- Boulton A, Allport T, Kaiwai H, Potaka Osborne G, Harker R. 2021. E hoki mai nei ki te ūkaipō—return to your place of spiritual and physical nourishment. Genealogy. 5(2):45. doi:10.3390/genealogy5020045.

- Bronfenbrenner U. 1995. Developmental ecology through space and time: a future perspective. In: Moen P, Elder GH, Lüscher K, editor. Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development. Washington: American Psychological Association; p. 619–647. doi:10.1037/10176-018

- Bryers C, Curtis E, Tkatch M, Anderson A, Stokes K, Kistanna S, Reid P. 2021. Indigenous secondary school recruitment into tertiary health professional study: a qualitative study of student and whānau worldviews on the strengths, challenges and opportunities of the Whakapiki Ake project. High Educ Res Dev. 40(1):19–34. doi:10.1080/07294360.2020.1857344.

- Burgess H, Painting TK. 2020. Onamata, anamata: a whakapapa perspective of Māori futurisms. In: Murtola A-M, Walsh S, editors. Whose futures? Economic and social research Aotearoa; p. 207–233.

- Came HA, Herbert S, McCreanor T. 2019. Representations of Māori in colonial health policy in Aotearoa from 2006-2016: a barrier to the pursuit of health equity. Crit Public Health. 31(3):1–11. doi:10.1080/09581596.2019.1686461.

- Carlson T, Moewaka Barnes H, Reid S, McCreanor T. 2016. Whanaungatanga: a space to be ourselves. Journey Indig Wellbeing. 1(2):44–59.

- Clark T, Robinson E, Crengle S, Fleming T, Ameratunga S, Denny S, Bearinger L, Sieving R, Saewyc E. 2011. Risk and protective factors for suicide attempt among indigenous Māori youth in New Zealand: the role of family connection. Int J Indig Health. 7(1):16–31. doi:10.3138/ijih.v7i1.29002.

- Cooper E. 2021. Tōku reo, tōku ngakau: learning the language of the heart. In: Waitoki W, Le Grice J, Black R, Nairn R, Pehi P, editor. Kua Tū Kua Oho realising bicultural partnership. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Psychological Society; p. 161–194.

- Cram F, Vivienne K. 2010. Researching with whānau collectives. MAI Rev. 3:1–12.

- Curtis E, Wikaire E, Kool B, Honey M, Kelly F, Poole P, Barrow M, Airini ES, Reid P. 2015. What helps and hinders indigenous student success in higher education health programmes: a qualitative study using the critical incident technique. High Educ Res Dev. 34(3):486–500. doi:10.1080/07294360.2014.973378.

- Deane K, Dutton H, Kerekere E. 2019. Ngā Tikanga Whanaketanga – He Arotake Tuhinga. A review of Aotearoa New Zealand youth development research. Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland. https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/100869.

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. 2018. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 5th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Durie M. 1984. Te Whare Tapa Whā. Māori health model. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health.

- Durie M. 2001. Mauri Ora: the dynamics of Maori health. Auckland, New Zealand: Oxford University Press.

- Durie MH. 1997. Whānau, whanaungatanga and health Māori development. In: Whaiti PT, McCarthy MB, Durie A, editor. Mai Rangiatea Maori wellbeing and development. Auckland: Bridget Williams Books with Auckland University Press; p. 1–24.

- Edwards S, McCreanor T, Moewaka-Barnes H. 2007. Maori family culture: a context of youth development in counties/Manukau. Kotuitui N Z J Soc Sci Online. 2(1):1–15. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2007.9522420.

- Fanian S, Young SK, Mantla M, Daniels A, Chatwood S. 2015. Evaluation of the Kts’iìhtła (“We light the fire”) project: building resiliency and connections through strengths-based creative arts programming for indigenous youth. Int J Circumpolar Health. 74(1):27672. doi:10.3402/ijch.v74.27672.

- Graham J. 2005. He Apiti Hono, He Tatai Hono: that which is joined remains an unbroken line - using Whakapapa (genealogy) as the basis for an indigenous research framework. Aust J Indig Educ. 34:86–95.

- Graham R, Masters-Awatere B. 2020. Experiences of Māori of Aotearoa New Zealand’s public health system: a systematic review of two decades of published qualitative research. Aust N Z J Public Health. 44(3):193–200. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12971.

- Greaves L, Le Grice J, Schwencke A, Crengle S, Lewycka S, Hamley L, Clark TC. 2021. Measuring whanaungatanga and identity for well-being in rangatahi Māori: creating a scale using the Youth19 rangatahi smart survey. MAI J N Z J Indig Scholarsh. 10(2):93–105. doi:10.20507/MAIJournal.2021.10.2.3.

- Groot S, Hodgetts D, Waimarea Nikora L, Leggat-Cook C. 2011. A Māori homeless woman. Ethnography. 12(3):375–397. doi:10.1177/1466138110393794.

- Groot S, Le Grice J, Nikora L. 2018. Indigenous psychology in New Zealand. In: Wen Li W, Hodgetts D, Hean Foo K, editor. Asia-Pacific perspectives on intercultural psychology [Internet]. London: Routledge; p. 198–217. https://doi-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/10.4324/9781315158358.

- Groot S, Vandenburg T, Hodgetts D. 2017. I’m tangata whenua, and I’m still here. Māori youth homelessness. In: Groot S, van Ommen C, Masters-Awatere B, Tassell-Matamua NA, editor. Precarity: uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand [Internet]. Massey University Press; [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. http://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5061916.

- Hall M, Rata A, Adds P. 2013. He Manu Hou: the transition of Māori students into Māori studies. Int Indig Policy J 4(4). doi:10.18584/iipj.2013.4.4.7

- Hamley L, Groot S, Le Grice J, Gillon A, Greaves L, Manchi M, Clark T. 2021. “You’re the one that was on uncle’s wall!”: identity, whanaungatanga and connection for takatāpui (LGBTQ+ Māori). Genealogy. 5(2):54. doi:10.3390/genealogy5020054.

- Hamley L, Le Grice J. 2021. He kākano ahau – identity, indigeneity and wellbeing for young Māori (indigenous) men in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Fem Psychol. 31(1):62–80. doi:10.1177/0959353520973568.

- Harper D. 2002. Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Vis Stud. 17(1):13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Henwood C, George J, Cram F, Waititi H. 2018. Rangatahi Māori and youth justice [Internet]. New Zealand: Iwi Chairs Forum. https://iwichairs.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/RESEARCH-Rangatahi-Maori-and-Youth-Justice-Oranga-Rangatahi.pdf.

- Hikuroa D. 2017. Mātauranga Māori—the ūkaipō of knowledge in New Zealand. J R Soc N Z. 47(1):5–10. doi:10.1080/03036758.2016.1252407.

- Hinton R, Kavanagh DJ, Barclay L, Chenhall R, Nagel T. 2015. Developing a best practice pathway to support improvements in indigenous Australians’ mental health and well-being: a qualitative study: figure 1. BMJ Open. 5(8):e007938. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007938.

- Isaacs AN, Maybery D, Gruis H. 2012. Mental health services for aboriginal men: mismatches and solutions: mental health services for aboriginal men. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 21(5):400–408. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00809.x.

- Jackson M. 2013, July 3. He manawa whenua. Paper presented at: He Manawa Whenua Indigenous Research Conference 2013; Jun 30-Jul 3. Hamilton, New Zealand. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = lajTGQN8aAU.

- Kara E, Gibbons V, Kidd J, Blundell R, Turner K, Johnstone W. 2011. Developing a Kaupapa Māori framework for Whānau Ora. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 7(2):100–110. doi:10.1177/117718011100700203.

- Keelan TJ. 2001. E tipu e rea: an indigenous theoretical framework for youth development. Dev Bull. 56:62–65.

- Keelan TJ. 2014. Nga reanga youth development: Māori styles [Internet]. [Ara Taiohi]; [accessed 2021 Jun 2]. http://www.unitec.ac.nz/epress/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Nga-Reanga-Youth-Development-Maori-styles-by-Teorongonui-Josie-Keelan.pdf.

- Kidman J. 2012. The land remains: Māori youth and the politics of belonging. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 8(2):189–202. doi:10.1177/117718011200800207.

- Kidman J, MacDonald L, Funaki H, Ormond A, Southon P, Tomlins-Jahnkne H. 2021. ‘Native time’ in the white city: indigenous youth temporalities in settler-colonial space. Child Geogr. 19(1):24–36. doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1722312.

- King P. 2019. The woven self: an auto-ethnography of cultural disruption and connectedness. Int Perspect Psychol. 8(3):107–123. doi:10.1037/ipp0000112.

- Kukutai T, Webber M. 2017. Ka Pū Te Ruha, Ka Hao Te Rangatahi: Maori identities in the twenty-first century. In: Bell A, Elizabeth T, McIntosh T, Wynyard M, editor. A land of milk and honey? Making sense of Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press; p. 71–82.

- Lacey C, Huria T, Beckert L, Gilles M, Pitama S. 2011. The Hui process: a framework to enhance the doctor–patient relationship with Maori. N Z Med J. 123:72–78. https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/the-hui-process-a-framework-to-enhance-the-doctor-patient-relationship-with-maori.

- Le Grice J. 2014. Māori and reproduction, sexuality education, maternity, and abortion [dissertation]. Auckland: University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/23730.

- Le Grice J, Braun V, Wetherell M. 2017. What I reckon is, is that like the love you give to your kids they’ll give to someone else and so on and so on": whanaungatanga and matauranga Maori in practice. N Z J Psychol. 46(3):88–97.

- Lee-Morgan J. 2019. Pūrākau from the inside-out: regenerating stories for cultural sustainability. In: Archibald J-A, Lee-Morgan J, De Santolo J, editors. Decolonizing research: Indigenous storywork as methodology; p. 151–166.

- Lindsay Latimer C, Le Grice J, Hamley L, Greaves L, Gillon A, Groot S, Manchi M, Renfrew L, Clark TC. 2021. Why would you give your children to something you don’t trust?”: Rangatahi health and social services and the pursuit of tino rangatiratanga. Kotuitui N Z J Soc Sci Online. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2021.1993938.

- Manaaki Collective. 2021. About the Manaaki Collective [Internet]. https://themanaakicollective.nz/the-manaaki-collective/.

- McNatty W. 2001. Whanaungatanga [master's thesis]. Hamiton: University of Waikato.

- Mika CTH. 2015. The thing’s revelation: some thoughts on Māori philosophical research. In: Pihama L, Southey K, Tiakiwai S, editor. Kaupapa Rangahau: a Reader a collection of readings from the Kaupapa Māori Research workshop series [Internet]. 2nd ed. Hamilton, New Zealand: University of Waikato; p. 55–62. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/12340.

- Mika CTH. 2016. Worlded object and its presentation: a Māori philosophy of language. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 12(2):165–176. doi:10.20507/AlterNative.2016.12.2.5.

- Moeke-Pickering T. 1996. Maori identity within whanau: a review of literature. Hamilton, New Zealand: University of Waikato. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/464.

- Moewaka Barnes H, McCreanor T. 2019. Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. J R Soc N Z. 49(sup1):19–33. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439.

- Mooney H. 2013. Maori social work views and practices of rapport building with rangatahi Maori. Aotearoa NZ Soc Work. 24(3/4):49–64.

- NiaNia W, Bush A, Epston D. 2017. Collaborative and indigenous mental health therapy: tataihono, stories of Maori healing and psychiatry. New York: Routledge.

- O’Carroll AD. 2013. Virtual whanaungatanga: Māori utilizing social networking sites to attain and maintain relationships. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 9(3):230–245. doi:10.1177/117718011300900304.

- Paewai RA. 2013. The education goal of Māori succeeding “as Māori”: the case of time [master's thesis]. Auckland: University of Auckland; [accessed 2019 Jul 3]. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/20617/whole.pdf?sequence = 6.

- Pere RT, Nicholson N. 1997. Te wheke: a celebration of infinite wisdom. Np: Ao Ako Global Learning NZ.

- Pihama L, Cram F, Walker S. 2002. Creating methodological space: a literature review of Kaupapa Maori research. Can J Native Educ. 26(1):30–43.

- Pihama L, Lee J, Te Nana R, Campbell D, Greensill H, Tauroa T. 2015. Te Pā Harakeke: Whānau as a site of wellbeing. In: Rinehart RE, editor. Ethnographies in pan Pacific research: tensions and positionings. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; p. 251–264.

- Pihama L, Reynolds P, Smith C, Reid J, Smith LT, Nana RT. 2014. Positioning historical trauma theory within Aotearoa New Zealand. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 10(3):248–262. doi:10.1177/117718011401000304.

- Pitama S, Robertson P, Cram F, Gillies M, Huria T, Dallas-Katoa W. 2007. Meihana model: a clinical assessment framework. NZ J Psychol. 36(3):118–126.

- Pomare PP. 2015. He kākano ahau i ruia mai i Rangiātea: engaging Māori in culturally-responsive child and adolescent mental health services. [dissertation]. Auckland: University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/26748/whole.pdf?sequence = 5&isAllowed = y.

- Rangihuna D, Kopua M, Tipene-Leach D. 2018. Mahi a Atua: a pathway forward for Māori mental health? The NZ Med J. 131(1471):7518.

- Rata A. 2015. The Māori identity migration model. Mai J. 4(1):3–14.

- Reid J, Taylor-Moore K, Varona G. 2014. Towards a social-structural model for understanding current disparities in Maori health and well-being. J Loss Trauma. 19(6):514–536. doi:10.1080/15325024.2013.809295.

- Ritchie JE. 1992. Becoming bicultural. Thorndon, Wellington: Huia Publishers.

- Roberts M. 2013. Ways of seeing: whakapapa. Sites J Soc Anthropol Cult Stud. 10(1):93–120. doi:10.11157/sites-vol10iss1id236.

- Schnell I, Mishal S. 2008. Place as a source of identity in colonizing societies: Israeli settlements in Gaza. Geogr Rev. 98(2):242–259. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2008.tb00298.x.

- Smith LT. 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples. London/New York/Dunedin: Zed Books ; University of Otago Press. Distributed in the USA exclusively by St. Martin’s Press.

- Smith LT. 2006. Researching in the margins issues for Māori researchers a discussion paper. Altern Int J Indig Peoples. 2(1):4–27. doi:10.1177/117718010600200101.

- Sugarman J, Thrift E. 2020. Neoliberalism and the psychology of time. J Humanist Psychol. 60(6):807–828. doi:10.1177/0022167817716686.

- Teddy L, Nikora L, Guerin B. 2008. Place attachment of Ngāi Te Ahi to Hairini Marae. MAI Rev [Internet]. 1. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/1233.

- Tuhaka C, Zintl J. 2019. Mana Taiohi – the journey, the destination. Kaiparahuarahi. 1(2):5–7.

- Tupaea M. 2020. He kaitiakitanga, he māiatanga: colonial exclusion of mātauranga Māori in the care and protection of tamaiti atawhai [Masters of Science]. University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/54290/Tupaea-2020-thesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=n.

- Vandenburg T, Groot S, Nikora LW. 2021. “This isn’t a fairy tale we’re talking about; this is our real lives” : community-orientated responses to address trans and gender diverse homelessness. J Community Psychol. doi:10.1002/jcop.22606.

- Waitoa JH. 2013. E-whanaungatanga: the role of social media in Māori political engagement [master's]. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Massey University. [accessed 2021 Jan 25]. https://mro-ns.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/5461.

- Waitoki W. 2016. The baskets of knowledge: a curriculum for an indigenous psychology. In: Waitoki W, Levy MP, New Zealand Psychological Society, editors. Te manu Kai i te mātauranga: indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand. 1st ed. Wellington, New Zealand: The New Zealand Psychological Society; p. 283–296.

- Walker S, Eketone A, Gibbs A. 2006. An exploration of kaupapa Maori research, its principles, processes and applications. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 9(4):331–344. doi:10.1080/13645570600916049.

- Walsh-Mooney HA. 2009. The value of rapport in rangatahi Māori mental health: a Māori social work perspective [master's]. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Massey University.

- Ware F. 2009. Youth development, Māui styles: kia tipu te rito o te pā harakeke: tikanga and āhuatanga as a basis for a positive Māori youth development approach. [master's]. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Massey University. https://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/1152/02_whole.pdf?sequence = 1&isAllowed = y.

- Ware F, Walsh-Tapiata W. 2010. Youth development: Maori styles. Youth Stud Aust. 29(4):18–29.

- Webber M, Macfarlane A. 2017. The transformative role of iwi knowledge and genealogy in Māori student success. In: McKinley EA, Smith LT, editor. Handbook of indigenous education [internet]. Singapore: Springer Singapore; p. 1–25. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1839-8_63-1

- Webber M. 2020. Mana Tangata: the five optimal cultural conditions for Māori student success. J Am Indian Educ. 59(1):26. doi:10.5749/jamerindieduc.59.1.0026.

- Williams AD, Clark TC, Lewycka S. 2018. The associations between cultural identity and mental health outcomes for indigenous Māori youth in New Zealand. Front Public Health. 6:1–9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00319.

- Willig C. 1999. Beyond appearances: a critical realist approach to social constructionist work. In: Nightingale D, Cromby J, editor. Social constructionist psychology: a critical analysis of theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press; p. 37–51.

- Wilson D, Moloney E, Parr JM, Aspinall C, Slark J. 2021. Creating an indigenous Māori-centred model of relational health: a literature review of Māori models of health. J Clin Nurs. doi:10.1111/jocn.15859.