ABSTRACT

This study explores possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga, or Indigenous self-determination. We start by illustrating the role of taxation in erasing Indigenous sovereignty to first establish colonial authority, and then maintain this authority through an inequitable taxation system. We are motivated by emerging arguments around the importance for Indigenous practices and perspectives in governance, but without the proper resourcing to do so, Indigenous peoples rely on limited capacity and immeasurable amounts of unpaid labour. We thus explore how a colonial authority has resourced its authority, and erased Indigenous sovereignty, while exploring opportunities to resource Indigenous self-determination. This study merely scratches the surface of possibilities by mapping and mirroring sources of revenue generated by the Government of New Zealand and imagining how this revenue can either be shared through various means (incremental opportunities) or how Indigenous authorities can resource themselves through alternative means (progressive opportunities). In doing so we take the possibilities of a Te Tiriti-compliant taxation system seriously.

Introduction

Self-determination is vital for Indigenous Peoples in settler-colonial contexts. But self-determination needs to be resourced. In the context of New Zealand, Indigenous self-determination is guaranteed in Te Tiriti/The Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti). Te Tiriti sets up two spheres of sovereignty (Matike Mai Aotearoa Citation2016). Kāwanatanga, generally translated as ‘the complete right to government’, was granted to the Crown in Article One. Tino rangatiratanga, generally translated as ‘the unqualified exercise of chieftainship’, was guaranteed to Māori in Article Two (Kawharu Citation1998). However, the kāwanatanga sphere, via the Crown, has claimed exclusive right to expansive resourcing (including taxation), limiting the ability of the rangatiratanga sphere to resource itself. So, while Te Tiriti establishes the possibility for two forms of sovereignty, only one Tiriti Partner is able to directly resource itself. This limits self-determination for Māori. This contradiction surfaces related questions: what are the implications of how the kāwanatanga sphere resources itself? And what are the possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga?

This study explores resourcing of kāwanatanga and opportunities for rangatiratanga by addressing the above question. We do so because the increasing expectations for Māori to participate, partner and protect, are seldom properly resourced, relying on limited capacity and immeasurable amounts of volunteer labour (Scobie and Sturman Citation2020). This paper merely scratches the surface of possibilities by mapping and mirroring Crown revenue generating sources, and imagining how this revenue can either be shared through various means (incremental opportunities) or how the rangatiratanga sphere can resource itself through alternative means (progressive opportunities). In doing so we take the possibilities of an anti-racist, or more specifically, a Te Tiriti-compliant taxation system, seriously (Lipman Citation2022).

This paper makes two primary contributions. Theoretically, we assemble a brief but troubled history of resourcing kāwanatanga and colonisation in order to historically situate the possibilities for the future of resourcing rangatiratanga. This theoretical exploration surfaces a simplified framework to understand how taxation has resourced the kāwanatanga sphere, while contributing to dispossession in the rangatiratanga sphere and gradually erasing Māori sovereignty. This challenges rangatiratanga and Article 2 of Te Tiriti by recasting Māori from sovereigns to engage with, to citizen subjects of the Crown. Once sovereignty was erased and Māori had been fiscally disciplined, inequities have been maintained and exacerbated through taxation, which challenges equity and Article 3 of Te Tiriti. Empirically, we lay out several possibilities for directly and indirectly resourcing rangatiratanga. This is often limited to grants from the assumed sovereignty of the Crown, or distributions from existing development by land trusts and post-settlement governance entities. However, by thinking critically, new possibilities are introduced for resourcing rangatiratanga.

This paper consists of a desk-based exploratory study of possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga. As such, we have not engaged in primary interview/case study or archival research. We conducted a literature review, including grey literature, to explore historical and contemporary Crown sources of revenue, and arrangements for resourcing Indigenous peoples in other jurisdictions. We then set about discussing as a team how these existing sources could be used by Māori and the Crown to resource rangatiratanga Footnote1. The study is broadly inspired by the spheres of influence framework set out in Matike Mai (Matike Mai Aotearoa Citation2016). This acts as both an empirical category for research, e.g. how do we resource the rangatiratanga sphere, but also an overriding metaphor or our theoretical approach, e.g. that spheres of influence exist and can be resourced is a theoretical commitment in itself.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a brief overview of existing literature on the relationship between Māori and colonisation and taxation, including how kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga are resourced. In doing so, we present a possible Te Tiriti-based framework for thinking through resourcing kāwanatanga and rangatiratanga. We then present the findings of this exploratory research and introduce incremental possibilities including revenue sharing of existing streams and other transfers; and progressive possibilities including direct revenue generation. We support these possibilities with existing case studies from here and abroad. We conclude with a discussion of findings and contributions, provide some final thoughts, and suggest opportunities for future research.

Taxation, colonialism, sovereignty and equity

Māori were made to fund their own colonisation (Barber Citation2020). This occurred through early speculation and pre-emption, war and confiscation, and the Native Land Court, among other methods. The settler-government’s ability to resource its kāwanatanga over time was the flip side of the diminishing ability for Māori to resource their own rangatiratanga over the same time. Taxation, whether direct or indirect through dispossession, served the dual purpose of resourcing the Crown’s kāwanatanga and extending the Crown’s assumption of sovereignty to obscure and erase rangatiratanga.

Comyn (Citation2019) provides a fine-tooth analysis of the relationship between the New Zealand Company (NZC) and the Crown. The socialising power of finance was able to provide material support for the early colonisation of New Zealand, not initially from the Crown or British government but from the British capitalist class. The maiden voyage of the NZC’s Tory set off both without sanction and in direct defiance of the authority of the British Crown. Comyn (Citation2019) points out that prior to the Tory even landing in New Zealand and negotiating purchase with Māori, Māori land amounting to 110,000 acres had already been ‘sold’ by the NZC. It was pure and rampant fraud.

Comyn (Citation2019) concludes the NZC thus occupied a paradoxical position where reckless speculation was required to keep it afloat, but was driving it towards collapse. It ended up heavily indebted and because there was so much and so many invested; one of the first orders of business for the newly established New Zealand Parliament in 1854 was to authorise the public bailout of NZC. ‘It was thus that the founding of the modern nation of ‘New Zealand’ quite aptly coincided with the settling of its colonial debts’ (Comyn Citation2019, p. 63). The New Zealand settler government was born into debt, and it would need to fund itself to maintain and extend its authority. It did so by taking up a key part of Wakefield’s (Citation1849/1914) theory of systematic colonisation - an artificially (high) price on land independent of supply and demand. This approach was otherwise known as Crown pre-emption.

This is supported by Hooper and Kearins (Citation2003), who find that the formation of the settler-government in the early years was predominantly funded by Māori resources through two means: Crown pre-emption of Māori land through the 1840s and customs revenue (predominantly from Māori) through the 1850s. The first concept, the authors refer to as ‘taxation by pre-emption’, the second as ‘taxation without representation’. The low prices paid by the Crown for Māori land were justified by benefits, such as ‘civilisation’ for Māori under British rule. Already by 1844, £4,054 had been paid for land sold for £40,263 and the authors estimate from data gathered that Māori resources contributed disproportionately (at times over 3x more per capita than Pākehā) to government revenue throughout the mid-1800s and early 1900s (see also Hooper and Kearins Citation2004, Citation2008). They liken this to a capital gains tax on Māori in substance if not form, because the Crown directly accrued all the revenue from the capital gain that its own single-buyer status enabled.

Hooper and Kearins (Citation2004) focus on land confiscations through the New Zealand Settlements Act 1863 and Public Works Land Act 1864 which were another major source of Crown revenue and, as they were only targeted at Māori, were further colonial land appropriations (Hooper and Kearins Citation2004). Their 2008 paper notes examples of undervaluing Māori land, exploiting the Crown’s single buyer position, extortionate transaction and valuation costs and the use of local Land Boards as agents, all working towards prizing the oyster from its shell (Māori land from Māori) to sell at considerable profit (Hooper and Kearins Citation2008). They conclude that whatever form a government requisition or pre-emption of land may take, its substance remains the same: indigenous landholders are displaced from their lands and their lands become a source of revenue to finance further colonisation.

While directly and indirectly taxing Māori to resource the Crown is an apparent strategy, Comyn (Citation2021) gets to the heart of the matter in a study of the Hokianga Dog Tax Uprising of 1898. Comyn evaluateswhy a seemingly mundane tax levied on dog owners was met by widespread repudiation and an armed uprising from Māori. On the surface, an obvious answer is Māori did not want to pay tax to the Crown for their dogs, which were economically, socially and culturally important. But Comyn argues that rangatiratanga and mana motuhake (sovereignty, autonomy, self-determination) were at the core of this resistance.

The Dog Registration Act 1880 was just one of a series of fiscal and regulatory measures restricting rangatiratanga, along with a wheel tax, land tax and seasonal restrictions on hunting. These were not only financially burdensome for Māori but represented another advance in the disciplinary financial regime of the Crown (Comyn Citation2021). These measures were a means to absorb Māori as financial subjects – citizens of the Crown rather than sovereign nations – and tacitly elicit consent to Crown authority (Comyn Citation2021). The Kingitanga (Māori King movement), a core part of the resistance, understood that complying with this new tax lent legitimacy to the Crown’s singular assumed sovereignty, and that submitting to it would be acceptance of a designation as colonised subjects and a breach of Te Tiriti (Comyn Citation2021). If at this time Crown taxation of Māori was seen as a breach of Te Tiriti, what does this mean for today in terms of resourcing multiple spheres of influence through, for example, taxation?

Taxation and dispossession is not just confined to the nineteenth century. Māori continued to be dispossessed under a liberal and sympathetic veneer following World War Two. Tau argues that the combination of the Town and Country Planning Act 1953 and the Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1967 resulted in a mass migration by external design of Māori from rural land that they owned, to urban areas that they predominantly had to rent (Tau Citation2015). These acts reduced the capital value of Māori land, which then came under the Ratings Act 1967. This meant councils could sell Māori land when rates were unpaid, despite often providing insufficient services to these lands. Land was often commercially and residentially unusable, so rates were unable to be paid, and Māori land was effectively confiscated. In this case, local government rates – a form of land tax – continued to be a tool of accumulation by dispossession (Harvey Citation2003). Accumulation for the Crown and propertied interests, by dispossession of Māori.

Taxation, colonisation, sovereignty and equity have been discussed in the taxation literature with varying levels of criticality. Christians (Citation2009) builds an argument around the relationship between sovereignty and taxation on the basis that tax policy both influences and is influenced by relationships among markets, citizens and states. Taxation is an essential component of sovereignty and it is difficult to imagine a sovereign being able to maintain its authority without raising revenue through taxation (Christians Citation2009). Because of this, taxation is plausibly an inherent right of sovereign status, and infringing on the right to taxation is an infringement on sovereignty (Christians Citation2009). Barrett and Strongman (Citation2013) argue if the Crown cannot guarantee autonomous development for Māori, why should Māori believe in the Crown’s assertion of sovereignty? A unitary construction of state ideology is questionable in even the most conservative interpretations of New Zealand as a bicultural society. They argue that antiquated and disputable conceptions of sovereignty should not present barriers to a more fundamental issue, which is whether there is space for indigenous self-determination (Barrett and Strongman Citation2013).

One of these antiquated views of sovereignty is that the Crown as single sovereign has exclusive right to taxation. Barrett (Citation2018) points out how highly centralised New Zealand’s taxation system is relative to other jurisdictions, and discusses possibilities and prospects for subsidiarity (government decisions to be made as closely to the citizen as is practicable) and fiscal devolution in New Zealand. While Barrett (Citation2018) does not touch on the possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga through taxation, the general proposition of fiscal devolution, where taxation powers shift from centre to local, or at least revenue sharing is formalised, opens up this possibility.

It is critical to re-examine basic assumptions about sovereignty and taxation, and this re-examination must remain open to alternative viewpoints about sovereignty, taxation and the social contract being shaped by people (Christians Citation2009). We argue this re-examination is crucial in settler-colonial contexts seeking reconciliation, and, especially, New Zealand, as we explore the possibilities of and challenges for resourcing rangatiratanga. Because if Māori never ceded sovereignty, and taxation is an inherent right of sovereignty, should Māori have been paying tax all this time? Is further compensation appropriate? Or could Māori raise taxes?

Indeed, this is happening in other jurisdictions, and this has surfaced both new possibilities and new contradictions. In the country currently known as Canada, Willmott (Citation2022) argues that sentiments about Indigenous peoples and government spending or welfare are expressed as fiscal concerns that often derive from racist critique. These fiscal concerns obscure white entitlement, racism and ultimately erode Indigenous legal and political sovereignty. They are best described as ‘fiscalized racism’ (Willmott Citation2022, p. 9). This marks a discursive and therefore substantive policy move, in terms of taxation and spending, from questions by settlers about Indigenous identity, nationhood and sovereignty – to questions by taxpayers about fiscal concerns. While Comyn (Citation2021) demonstrates how taxation established Crown sovereignty, Willmott’s scholarship demonstrates how this is maintained today.

In New Zealand, assumptions of the Crown’s singular sovereignty reinforces its exclusive right to taxation (Barrett and Strongman Citation2013; Barrett Citation2018). Emerging and accepted interpretations of Te Tiriti argue that Māori never ceded sovereignty (Fletcher Citation2022; Waitangi Tribunal Citation2014). What does this mean for taxation and wider possibilities for resourcing? This commitment to ‘oneness’ makes it difficult to imagine an alternative taxation regime, or nested sovereignties. At the very least, the exclusive right of the Crown to taxation and the revenue generating ability this enables to reinforce its kāwanatanga seems to have implications for the tino rangatiratanga guaranteed in Article 2 of Te Tiriti. A fundamental question is whether kāwanatanga gives an exclusive right to taxation, or if there is a basis within rangatiratanga for revenue generation. What then are the implications of Article Two and tino rangatiratanga for tax policy? We take up this discussion in the next section but first we need to deal with Article Three, which granted Māori all the rights of British subjects Because putting the crucial arguments of sovereignty and taxation aside, tax distribution has failed to meet the promises of protection and full citizenship, emphasising equality, within Article 3. This is particularly the case when social, health and economic outcomes are taken into consideration.

Article Three considerations for tax policy are fundamentally about equity. Scobie and Love (Citation2019) explore the Māori perspectives associated with the Tax Working Group Future of Tax report (Tax Working Group Citation2019). In alignment with these perspectives, they argue that a Māori worldview can contribute to a more equitable and sustainable tax system; engaging with Māori beyond tokenistic gestures can challenge and enhance public policy; and this is not just an obligation under Te Tiriti but will result in positive outcomes for all (Scobie and Love Citation2019).

Marriott (Citation2021) explores who is actively participating in and making submissions on tax proposals, finding that active Māori participation is limited. This lack of engagement could be for any number of reasons, not least of which is a lack of resourcing. The contradiction here being that a lack of resourcing from the tax system results in a lack of resourcing to engage and participate in designing the tax system. Although they do not engage in depth with questions of tax and sovereignty, Scobie and Love (Citation2019) point out that to better exercise something like kaitiakitanga (the ethic of stewardship), which has been put forward as a possible value to inform the tax system, a decision maker requires rangatiratanga. Without rangatiratanga, kaitiakitanga can be easily watered down and removed from the authority of Māori communities (see e.g. Kawharu Citation1998). While both studies take equity for Māori in the taxation system seriously, neither explicitly explore possibilities for taxation beyond equity (Article Three) towards rangatiratanga and shared sovereignty (Article Two). But they gesture towards a future where tax policy takes rangatiratanga and Article Two seriously.

The Treasury’s Living Standards Framework (LSF) is one attempt to take Te Tiriti seriously in tax and other policy development. The LSF was developed in 2011 to guide the Treasury to consider a more holistic view of wellbeing; rather than only accounting for traditional economic measures such as GDP (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2021b). The framework connects indicators of wellbeing (like cultural identity, health, and housing) to four capitals: natural, social, human, and financial and physical. This framework underpins policy making, budget discussions, and informs Treasury’s wellbeing reporting (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022d). However, the framework initially lacked Māori perspectives, knowledge, and wellbeing measures. As such, any policy decisions would have failed to account for Māori wellbeing, including within the budgeting process, creating further inequities in resourcing.

The LSF was updated by The Treasury with the ‘He Ara Wairoa" framework in 2019, which aims to incorporate Māori perspectives and take a tikanga-based approach to wellbeing (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2021a). The framework provides a holistic, intergenerational approach that is not exclusive to Māori wellbeing but emerges from Māori perspectives (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2021a). The framework recognises the interconnectivity between wairua (spirit), taiao (earth), he kāinga (collective) and he tangata (individual). This framework was developed through a principled engagement process with Māori, and as such, has been remarked by Māori researchers as an example of positive partnership between iwi and the Crown (McMeeking et al. Citation2019). However, this remark comes with the warning that if there is not continued engagement led by Māori, then He Ara Waiora could lose legitimacy in recognising Māori concepts of wellbeing (McMeeking et al. Citation2019). With authentic implementation, He Ara Waiora represents an opportunity to reduce historical and ongoing inequities in the tax and budgeting system for Māori. If the further development of the framework takes Article Two of Te Tiriti seriously, it may be able to contribute to resourcing of rangatiratanga within the policy and budgeting process.

One final study has informed our thinking through Article Three, equity and taxation. Lipman (Citation2022) sketches out how to design an antiracist state and local tax system by following Ibram X Kendi’s antiracist framework (Citation2019). This framework holds that a racist policy is any measure that produces or sustains racial inequity, which occurs when different racial groups are not on approximately equal footing. Racist policies come from racist ideas and systematically exclude, marginalise, exploit and generate unequal economic outcomes, while justifying and normalising those unequal outcomes. Policies that produce or sustain racial inequity are racist policies. Policies that produce or sustain racial equity are antiracist policies (Lipman Citation2022; following Kendi Citation2019).

Lipman (Citation2022) argues that the tax system in the US is racist because it sustains racial inequity. This is largely derived from existing income, spending and wealth inequity along racial lines that is perpetuated by regressive or inequitable tax systems. For example, if tax policies benefit high-income and wealthy taxpayers (decreasing top income tax rates, preferential treatment for investment income, eliminating wealth taxes, regressive consumption taxes) and high-income and wealthy taxpayers are disproportionately white, then this exacerbates racial inequity. But it does not have to be this way, if racism has informed the tax system, which continues to perpetuate racial inequity, antiracism can redesign the tax system and contribute to racial equity.

What are the implications of these arguments and possibilities for New Zealand? Are Māori and Pacific peoples disproportionately low-income and low-wealth households? Does New Zealand’s tax system rely heavily on the taxation of income and spending on goods and services, while giving preferential treatment to wealth? If the answer to the latter two questions is yes, then New Zealand’s tax system is racist, and requires an anti-racist redesign. This has implications for Article Three and equity for New Zealand more broadly. We might imagine together how to design an anti-colonial tax system that that takes Article Two and Three seriously.

This brief review has raised two fundamental issues to consider when thinking about resourcing rangatiratanga – sovereignty and equity. We can broadly map the substantive issue of sovereignty to Article Two, and the issue of racial equity to Article Three of Te Tiriti. Breaches of Article Two have, over time, reinforced the Crown’s sovereignty and exclusive right to taxation. This has radically limited capacity within the rangatiratanga sphere and gradually incorporated Māori from collective groupings with rangatiratanga to individual citizens of the Crown. Tax policy has constrained rangatiratanga and therefore Article Two. But if this is not enough, the promises under Article Three have failed to manifest within current tax policy and racial inequity has been reinforced by the tax system. Māori have less household wealth (Rashbrooke Citation2021, p. 82) and if we use household wealth as a measure of tax burden, our tax system maintains racial inequity and is therefore racist. While the income tax (including Working for Families) welfare system is progressive on the surface, low incomes for Māori and Pacific peoples prevent the accumulation of capital that allows generation of wealth which is taxed less relatively. Tax policy keeps Māori poor.

Māori therefore face a double taxation along Te Tiriti lines – first, impositions on and restrictions of rangatiratanga, secondly, inequitable policy as citizens. These two issues frame our response to the overriding research questions for this study: what are the implications of how the kāwanatanga sphere resources itself? And what are the possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga? We have addressed the first in this section and tend to the second in the next. We do so by exploring incremental opportunities seeking to better respond to Article Three and equity, and progressive opportunities seeking to better respond to Article Two and rangatiratanga.

Resourcing rangatiratanga

The Government’s main sources of revenue are taxes, levies, fees, investment income, and from the sales of goods and services. The Government’s total accumulated revenue for the year ended 30 June 2021 was $121.931b (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022a). 91 per cent of this ($110.789b) is from taxation, with the majority of taxation revenue from income, goods and services, and company tax. At the combined local government level, $12.5b (excluding valuation changes) was accumulated mostly from rates for the year ended 30 June 2021 (Stats Citation2022).

A surface level comparison of this with varying estimates of iwi asset bases or ‘the Māori economy’ suggests disparity in ability to resource governance. For example, TDB Advisory’s 2021 analysis estimates the combined assets of 9 iwi to be $10.8b in total, making up approximately 58% of all post-settlement iwi assetsFootnote2 (TDB Advisory Citation2022). Business and Economic Research Ltd’s (BERL) estimate of the asset base of the Māori economy in 2018, which includes Māori employers, self-employed, trusts, incorporations, and other entities, is $68.7b (BERL Citation2021). To produce a return on these total assets to either reinvest, distribute towards social spending (arguably not an iwi, land trust, or Māori business responsibility under Article Three of Te Tiriti) and advance rangatiratanga, these assets are subject to market conditions. Market conditions are volatile, but also fundamentally limited in opportunity compared to the ability to raise taxation.

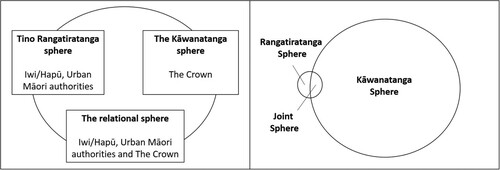

These comparisons are somewhat crude, and only give a vague indication of the real nature of resourcing and distributions. Comparing private and iwi asset bases, revenues and distributions, with government taxation and spending is problematic but this is part of the problem with resourcing rangatiratanga as it currently stands. The Crown can levy taxes and generates most of its revenue from doing so, Māori rely on a mix of grants/distributions from the Crown and subjecting assets to market forces. Rather than the representation of constitutional transformation depicted on the left in from Matike Mai (Matike Mai Aotearoa Citation2016), the reality is better represented in the figure on the right from He Puapua (Charters et al. Citation2019). Both Matike Mai and He Puapua have been put forward by Māori as possibilities for advancing rangatiratanga.

Figure 1. Left: Spheres of influence (Model 2) adapted from Matike Mai. Right: Spheres of influence (Model 2) adapted from He Puapua.

Constitutional transformation aspires towards a just, equitable and practical future for New Zealand. But this transformation must take economic transformation seriously to be considered just, equitable, and practical (Bargh and Tapsell Citation2021). As it stands, the kāwanatanga sphere has multiple means for generating revenue and reproducing its authority. The rangatiratanga sphere is structurally limited from doing the same. The relational sphere where they meet operates at the intersection of inequitably resourced spheres of influence. With this context established, we explore possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga as a contribution to conversations around constitutional transformation. We do so on a spectrum from incremental opportunities for resourcing to better commit to equity and issues with Article Three to progressive and radical opportunities more in line with rangatiratanga and Article Two.

Incremental opportunities

There are pre-existing methods for resourcing rangatiratanga via the kāwanatanga sphere. These are subject to the three-year political cycle and related whims, rotating public servants, and the boom and bust of the capitalist economy. Nonetheless, they are substantial and do materially advance Māori ability to advance rangatiratanga in some ways, but in many cases on the terms of the kāwanatanga sphere.

Grants are a well-known means for resourcing rangatiratanga. These refer to the financial sums given from the government to an entity, often for projects that align with the government's economic and social and environmental goals. These grants are outlined in yearly budgets, with the most recent Wellbeing Budget 2022: A Secure Future granting Māori $1.256bover four years (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022b). Meanwhile, total estimated actual expenditure was $131.4bfor the year ending 30 June 2022 (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022a). While this total expenditure will include spending that benefits Māori individuals as citizens of the Crown, for example, superannuation, education, health, this is spending in the kāwanatanga sphere. The Crown also provides estimates of yearly appropriations. For example, the estimated combined total funding for Māori affairs for year ending 30 June 2023 is $984.6 m (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022c).

An advantage of grants is that they typically require no repayment. Furthermore, organisations receiving grants often gain credibility that is beneficial for relations and securing future funding. However, for government grants Māori must rely on uncertain political environments, with changing parliamentary politics and public priorities. This revenue stream is also limited to the government's funding capacity with most of the budgeting process spent reconfirming existing projects and baseline expenditure restricting new spending initiatives (Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Citation2021).

Applicants experience barriers when accessing grants, including monetary and time resources spent on hiring and/or training staff for the lengthy application process (Parsons et al. Citation2021). Māori and smaller organisations often compete against larger and more resourced organisations. The expenditure required to access grants comes with limited certainty that it will eventuate into funding, producing further insecurity. Any funding granted is accompanied with conditions for spending, limiting Māori autonomy and rangatiratanga.

Another well-known form of returning resources to Māori are reparations through Treaty settlements. Reparations are a form of redress through a gesture of compensation for injustices that occurred in the past but continue to have egregious ramifications today. While often financial or ‘asset-based’, this compensation can also include non-monetary measures such as formal apologies and reform (Fisher Citation2020)

An advantage of reparations is that they seek to address the inequalities resulting from historical abuse or grievances. They also seek in some ways to restore the honour of the Crown and promote trust in institutions (Fisher Citation2020). This is crucial to demonstrating that reparations encompass more than just the financial gain to those harmed; they also serve as an imperative step towards reconciliation between states and peoples. Finally, they formally recognise the injustices experienced and reassert those impacted as rights holders. Disadvantages of reparations are well documented including who is entitled to reparations, quantifying loss, political will, and management and distribution of reparations following settlement (Mutu Citation2019).

In New Zealand, modern Treaty settlements are forms of reparation. Often framed by reactionary critics as a massive transfer of wealth, the total redress of finalised settlements from 1993 to 2018 sits at an estimated $2.24b (Manatū Taonga Citationn.d.). This figure includes the more easily quantifiable aspects of settlements like cash and land, but not cultural redress. This is less than 0.2% of the government's total expenditure, estimated at $1322b, over those 25 years (Fyers Citation2018). Not only is the amount received by Māori well exceeded by the government's spending capacity, but these settlements represent a tiny fraction of the value lost to Māori (Fisher Citation2020). The Crown has acknowledged this and instead places the focus on providing an economic base for iwi for their future development (Fisher Citation2020). Indeed, these small individual settlements have become sustaining economic bases in some cases. PSGEs have used Te Tiriti settlements for multiple purposes including sustaining identity, social spending and defending the realm, or defending rights and resources (O’Regan Citation2014).

Treaty settlements are controversial from many angles. However, they can offer PGSEs financial autonomy independent or at least interdependent with the Crown. This has its advantages in directing spending and investing in ‘defending the realm’ in a contemporary context. They certainly contribute to resourcing rangatiratanga but because of the low sums and high demands/requirements for future spending they are by no means equitable with the kāwanatanga sphere’s ability to resource its authority.

An emerging possibility in New Zealand that is established in other jurisdictions is an adaptation of social procurement, for example, Te Tiriti-led procurement. Public procurement refers to when a government agency buys goods or services from an external organisation. Social procurement aims to create social value by providing more opportunity for marginalised groups to participate in the economy.

The primary advantages of social procurement policy include the economic participation of marginalised groups in the economy, start-up and small business development, and increased training and employment opportunities. However, social procurement can also harm beneficiaries and risks undermining the aims of the policy, for example, by uprooting individuals from their people and place to take up the policy’s employment opportunities (Rogers et al. Citation2008). Another disadvantage for Indigenous procurement policy is the risk of double-taxing by shifting the responsibility of employing Indigenous peoples from the Crown onto Indigenous businesses, with the same responsibilities for capacity building not placed on non-Indigenous businesses. Finally, social procurement can incentivise misleading behaviour, for example, where contractors meet requirements by providing provisional or tokenistic jobs which overstate the positive impacts of the policy (Denny-Smith et al. Citation2020).

The Government of New Zealand has recently set a target that five percent of public sector contracts should be awarded to Māori businesses (defined as at least 50% Māori owned or classified as a Māori authority) (Nash and Jackson Citation2020). An early analysis of New Zealand’s procurement policy critiques its ability to only provide enhanced revenue-generating opportunities to Māori for contacts under $100,000 (Ruckstuhl et al. Citation2021). In addition, the policy could be rolled out to local government and in our view, advancing Te Tiriti-led procurement policy in New Zealand as a contribution to rangatiratanga needs to be workshopped seriously with mana whenua (people with rights to a territory).

Progressive opportunities

New Zealand’s tax system is highly centralised relative to other jurisdictions. The tax system is necessary to support the wellbeing of New Zealanders by providing revenue for public goods such as healthcare, education and infrastructure (Tax Working Group Citation2019). New Zealand's use of a progressive income tax in its system also plays a minor role in reducing inequality through redistributing wealth (Tax Working Group Citation2019). In 2017, the Tax Working Group (TWG) was tasked with considering how to make the taxation system fairer. Although they did not have a direct remit along the lines of Lipman’s (Citation2022) designing an anti-racist tax system, they took both equity and Māori perspectives seriously.

The TWG found that New Zealand's tax system has many strengths, such as a globally competitive broad-based, low-rate tax system that generates comparable tax revenue to other OECD countries (Tax Working Group Citation2019). This makes the tax system efficient, but it is not highly equitable or balanced. Indeed, TWG found that New Zealand's tax system reduces income inequality by less than the OECD average (Tax Working Group Citation2019). This is because New Zealand, unlike other developed countries, does not include a tax on capital gains. As a result, individuals earning the same amount of income may face differing tax obligations due to whether that income stems from capital gains or wages (Tax Working Group Citation2019). As such, TWG recommended that instating a capital gains tax to reduce the bias towards investing in assets, and particularly the property market, will improve the ‘fairness, integrity and fiscal sustainability of the tax system’ (Tax Working Group Citation2019, p. 8). This recommendation was not accepted by the government, which was surprising to many, given earlier indications (Maples and Yong Citation2019).

At the time, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced ‘All parties in the Government entered into this debate with different perspectives and, after significant discussion, we have ultimately been unable to find a consensus. As a result, we will not be introducing a capital gains tax’ (Ardern Citation2019). One of the ramifications of this for our purposes is that as Māori tend to be represented in labour and not capital markets, this has equity implications beyond socio-economic standing (Tax Working Group Citation2019). Maples and Yong (Citation2019) suggest that although some of the benefits of a capital gains tax may be overstated (e.g. addressing housing affordability), this may have been a missed opportunity to provide an additional source of revenue and ensure a more sustainable fiscal programme over the long term.

Rates are effectively a form of property tax, or the closest thing New Zealand has to a land tax and are the predominant form of funding for local government. Rates thus show some commitment to subsidiarity as they are set and raised by local government on the ground. Some sort of rates relief on Māori reserve land, or formalised revenue sharing of rates raised could represent a step towards resourcing rangatiratanga more directly. Recent reforms to the Local Government (Rating) Act 2002 indicate a willingness of the kāwanatanga to remove rateability on certain types of Māori freehold land, but has stopped short at removing all rates liability for Māori freehold landowners. Determining boundaries within overlapping mana whenua jurisdiction is an obvious challenge, and could exacerbate tensions, but these sorts of arguments can be used by opponents to prevent broader progress.

Levies are a specific tax imposed on individuals or groups to generate revenue, usually to cover the cost of a particular scheme. Those charged may play a role in contributing to an issue that the scheme addresses, such as fuel levies to fund infrastructure, or tourism levies to protect bioheritage. Alternatively, those charged may benefit from the scheme, such as the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) levying from individuals eligible to accidental injury compensation. Levies are thus a targeted form of taxation, and therefore have potential for resourcing rangatiratanga. For example, the $35 International Visitor Conservation and Tourism Levy (IVL) implemented in July 2019, is automatically charged to visitors alongside their visa or travel authority fees. The levy's revenue is evenly divided between conservation and tourism projects (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2021) and some sort of formalised revenue sharing, or targeted and proactive investment plan that includes Māori and iwi, has the potential to fulfil its aim of protecting biodiversity by resourcing rangatiratanga directly. Adjustments would need to be made to the investment plan to include Māori input in investment decisions, and consulting with and planning Māori-led projects. This will also have implications for accountability and may increase reporting requirements for those receiving funds.

While formalised revenue sharing remains a possibility, another more progressive step would be for Māori to resource their own rangatiratanga directly through taxation, rates, levies or something equivalent. Obviously, this would be incredibly challenging politically, given New Zealand’s cultural obsession with ‘oneness’, but in other jurisdictions, like the United States and Canada, some First Nations authorities collect tax revenue.

Canada and First Nations have been working towards a just fiscal relationship to ensure ‘sufficient, predictable and sustained funding for First Nations communities’ (Government of Canada Citation2021). The fiscal relationship outlines all revenue streams received by Indigenous Peoples, with critical components being tax-revenue sharing and the First Nations’ exercise of tax powers within their reserves (Government of Canada Citation2019). Currently, an estimated 30 per cent of First Nations in Canada have exercised the right to levy taxes according to one of the two acts (Boissonneault Citation2021). As an example, the Squamish Nation in British Columbia, which has a total population of 4080, raised over $9 m in 2021 from taxation (equivalent of rates and GST) within their reserve (Squamish Nation Citation2021).

Participating First Nations gained a sufficient revenue-generating opportunity, improving the community's economic situation (Boissonneault Citation2021). This stable revenue stream is being used to support the long-term development and well-being of the community, enhancing First Nation self-determination. Additionally, it improved self-government's performance due to the increased accountability to the community invested in the outcomes. However, although exercising tax has expanded First Nations’ economic authority, this is still restricted by the Canadian government's legal and political authority (Boissonneault Citation2021). This refers to the government's control over Indigenous tax policy and governing structure. For example, the Canadian government has reduced the First Nations governance structure to municipal-style band councils to suit its current configuration, conflicting with enduring Indigenous governance (Boissonneault Citation2021). The existing system treats Nations as synonymous, a limitation identified in New Zealand co-governance arrangements that do not recognise independent iwi-to-iwi and hapū authority. In addition, there are risks that the Crown could withdraw basic service provision based on these new revenue generating possibilities. Finally, at a deeper level, many have expressed discomfort with the advancement of the Canada-First Nations fiscal relationship as extinguishing Indigenous rights, challenging underlying Indigenous sovereignty, in order to gain access to particular revenue generating abilities on the Crown’s terms (Yellowhead Institute Citation2021). Any pursuit of resourcing rangatiratanga in New Zealand should be cognisant of a range of opportunities, perspectives and critiques from other jurisdictions to understand possibilities and pitfalls.

Discussion and concluding thoughts

This paper set out to open up a conversation about resourcing rangatiratanga. We did this by addressing the research questions: what are the implications of how the kāwanatanga sphere resources itself? And what are the possibilities for resourcing rangatiratanga? In order to do this, we had to first set out a framework for understanding the dialectical relationship between resourcing of kāwantanga and rangatiratanga. That is, historically, the resourcing of the kāwanatanga sphere came directly at the expense of the resourcing of the rangatiratanga sphere – Māori were made to fund their own colonisation. The two substantive issues that emerged from this framework are that kāwanatanga taxation has played a part in the diminishing of rangatiratanga, thus challenging Article Two of Te Tiriti. Once established, our inequitable taxation system has failed to fulfil the promises of citizenship and equality under Article Three of Te Tiriti. This means that tax policy design, and broader considerations around resourcing as part of or as a move towards constitutional transformation, need to take Articles Two and Three of Te Tiriti seriously.

The extent of the government's revenue-generating ability and economic base has arisen from New Zealand’s colonial history of dispossession, repression, and assimilation. By maintaining sovereignty and ownership over all financial means including land, water, and taxes, the Government permits an ongoing exclusive and imbalanced fiscal relationship. This has restricted the self-determination of Māori leading to systemic discrimination and reduced well-being outcomes. Such an unequal fiscal relationship does not honour Te Tiriti so long as Māori are dependent on the government for any transfer of that misappropriated wealth. Therefore, resourcing rangatiratanga requires an economically sustaining base with multiple opportunities for revenue streams.

This study is exploratory. It is not exhaustive. There could be a whole suite of possibilities within, against and beyond the status quo that we have not engaged with. And we only introduced a handful of advantages and disadvantages. The point of this paper is to contribute to the conversation around constitutional transformation.

New Zealand has an unwritten constitution and relies on a variety of constitutional sources to make up its constitutional canon (Joseph Citation2021). Joseph (Citation2021) identifies nine sources, and Te Tiriti is one of these. Any constitutional transformation can, even from a conservative perspective, be based on Te Tiriti. We suggest that constitutional transformation needs to take economic transformation seriously if it is to be just and equitable. The increasing demands on Māori to consult, engage and lead are spreading thin resources thinner and as all aspects of the public, private and third sectors start to take their Te Tiriti obligations seriously, this will increase demands on limited resourcing further. Rangatiratanga must be resourced equitably, and we welcome further discussions about how this might look. A lot more work is needed in this space to explore the multitude of possibilities in detail and critique of existing proposals including ours.

As a start we suggest that engaging seriously with tax policy and possible reforms around tax principles be taken up by Māori as serious avenues to advance rangatiratanga (see Marriott Citation2021). While this has not historically been the case, for any number of reasons including, at best, ignorant and, at worst, racist dismissals of Māori practices and perspectives, the possibilities remain. What do Māori see as essential tax principles for advancing rangatiratanga? Are manaakitanga (hospitality/kindness) and kaitiakitanga enough? Are selected ‘principles’ of Te Tiriti – participation, partnership and protection – enough? Or do we need principles that honour Article Two and Three of Te Tiriti explicitly? Should principles for tax policy include rangatiratanga and racial equity? It is noteworthy that none of the guiding pieces of taxation legislation have a Te Tiriti clause compelling the Crown to engage in a Te Tiriti principles exercise in taxation. This would appear to be a deliberate omission of Parliament. However recent case law from the Supreme Court suggests that Te Tiriti compliance should not be limited in any exercise of statutory interpretation (Trans-Tasman Resources Limited v The Taranaki-Whanganui Conservation Board [Citation2021] NZSC 127).

Likewise, the institutions of Treasury and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand are starting to seriously engage with Māori perspectives including employing and contracting considerable Māori expertise. Optimistically this could be because of obligations under Te Tiriti, cynically it could be tokenistic. We hope it is the former, but if the latter, moving towards the former requires thinking through ways to hold these institutions to account under Te Tiriti. Engaging with these institutions, including their frameworks like He Ara Waiora, to advance rangatiratanga and broader constitutional transformation is another opportunity to strategically work through the multiple arms of the Crown.

Market and debt mechanisms are often presented as possibilities (The Treasury New Zealand Citation2022e). These are certainly possibilities for iwi, hapū and other entities to resource rangatiratanga, but the potential disadvantages are numerous, including increasing exposure to risk, further dispossession if over-exposed, amplifying inequity, and financialising the environment (see e.g. Yellowhead Institute Citation2021; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Citation2021). These opportunities should be explored further, but with caution. In addition, public budgeting is the predominant form of spending tax revenues towards social, environmental and economic outcomes. Cabinet Circular 18 (2) provides the guidance for how Cabinet is to approve public funding is distributed by the Crown (New Zealand Government Citation2018). Cabinet’s decision making under this document is often undertaken in secrecy and does not seem to commit to the principle of Te Tiriti Partnership let alone a relational sphere between sovereigns. It is noteworthy that Cabinet Circular 18 (2) is silent on Te Tiriti or the Crown’s obligations under Te Tiriti Finally, there are existing versions of Māori collecting forms of revenue internally – e.g. koha (gifts/donations) to support marae (meeting houses) – forms of internal revenue raising are certainly possibilities. All of these avenues for change, and many more, provide new terrains for strategically advancing rangatiratanga as part of a broader Indigenous political economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 At the time of research design, writing and submission of the manuscript. Andraya Heyes was employed at the University of Canterbury. The views, opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are strictly those of the authors.

2 TDB Advisory’s 2021 iwi investment analysis reviews 9 iwi organisations chosen based on year and size of Treaty settlement, number of iwi members, and availability and transparency of financial information. This includes Ngāi Tahu, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Pāhauwera, Ngati Porou, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, Raukawa, Tūhoe and Waikato-Tainui. They include Ngāpuhi because of the size of their membership base despite not being ‘post-settlement’.

References

- Ardern J. 2019. Government will not implement a capital gains tax. [accessed 2023 Mar 23]. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-will-not-implement-capital-gains-tax.

- Barber S. 2020. In Wakefield’s laboratory: tangata whenua into property/labour in Te Waipounamu. Journal of Sociology. 56(2):229–246.

- Bargh M, Tapsell E. 2021. For a Tika Transition: strengthen rangatiratanga. Policy Quarterly. 17(3):13–22.

- Barrett J. 2018. Subsidiarity and fiscal devolution: possibilities and prospects for New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Taxation Law and Policy. 24:382–404.

- Barrett J, Strongman L. 2013. Sovereignty in postcolonial Aotearoa New Zealand: ambiguities, paradoxes, and possibilities. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review. 36(2):341–357.

- BERL. 2021. Te Ōhanga Māori 2018: the Māori economy 2018. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://berl.co.nz/our-mahi/te-ohanga-maori-2018.

- Boissonneault A. 2021. Policy forum: a critical analysis of property taxation under the First Nations fiscal management act as a self-government tool. Canadian Tax Journal. 69(3):799–812.

- Charters C, Kingdon-Bebb K, Olsen T, Ormsby W, Owen E, Ruru J, Solomon N, Williams G, Pryor J. 2019. He Puapua: report of the working group on a plan to realise the UN declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples in Aotearoa, New Zealand. [accessed 2023 Mar 23]. https://www.tpk.govt.nz/documents/download/documents-1732-A/Proactive%20release%20He%20Puapua.pdf.

- Christians A. 2009. Sovereignty, taxation and social contract. Minnesota Journal of International Law. 18(1):99–153.

- Comyn C. 2019. How finance colonised Aotearoa: a concise counter-history. Counterfutures. 7:41–72.

- Comyn C. 2021. The Hokianga Dog Tax uprising. Counterfutures. 11:19–33.

- Denny-Smith G, Williams M, Loosemore M. 2020. Assessing the impact of social procurement policies for Indigenous people. Construction Management and Economics. 38(12):1139–1157.

- Fisher M. 2020. A long time coming: the story of Ngāi Tahu’s treaty settlement negotiations with the Crown. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press.

- Fletcher N. 2022. The English text of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books.

- Fyers A. 2018. The amount allocated to Treaty of Waitangi settlements is tiny, compared with other government spending. Stuff. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/104205997/the-amount-allocated-to-treaty-settlements-is-tiny-compared-with-other-government-spending.

- Government of Canada. 2019. Canada’s collaborative self-government fiscal policy. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1566482924303/1566482963919.

- Government of Canada. 2021. Establishing a new fiscal relationship. [accessed 2022 Dec 04]. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1499805218096/1521125536314.

- Harvey D. 2003. The new imperialism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Hooper K, Kearins K. 2003. Substance but not form: capital taxation and public finance in New Zealand, 1840-1859. Accounting History. 8(2):101–119.

- Hooper K, Kearins K. 2004. Financing New Zealand 1860–1880: Maori land and the wealth tax effect. Accounting History. 9(2):87–105.

- Hooper K, Kearins K. 2008. The walrus, carpenter and oysters: liberal reform, hypocrisy and expertocracy in Maori land loss in New Zealand 1885–1911. Critical Perspectives on Accounting. 19(8):1239–1262.

- Joseph P. 2021. Constitutional and administrative law in New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Thomson Reuters New Zealand.

- Kawharu M. 1998. Dimensions of kaitiakitanga: an investigation of a customary Māori principle of resource management. Oxford University. 8:1239–1262.

- Kendi IX. 2019. How to be an antiracist. London, England: The Bodley Head.

- Lipman FJ. 2022. How to design an antiracist state and local tax system. Seton Hall Law Review.

- Manatū Taonga. n.d. What are Treaty settlements and why are they needed? Te Tai. [accessed 2022 Oct 14]. https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-tai/about-treaty-settlements.

- Maples A, Yong S. 2019. The Tax Working Group and capital gains tax in New Zealand – a missed opportunity? Journal of Australian Taxation. 21(2):66–85.

- Marriott L. 2021. Crown consultation, Māori engagement and tax policy in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Taxation Law and Policy. 27(2):143–171.

- Matike Mai Aotearoa. 2016. Matike Mai Aotearoa. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://nwo.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MatikeMaiAotearoa25Jan16.pdf.

- McMeeking S, Kahi H, Kururangi K. 2019. Implementing He Ara Waiora in alignment with the Living Standards framework and Whānau Ora. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/17608.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. 2021. How the IVL works. [accessed 2022 Oct 07]. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/immigration-and-tourism/tourism/tourism-funding/international-visitor-conservation-and-tourism-levy/how-the-ivl-works/.

- Mutu M. 2019. The treaty claims settlement process in New Zealand and its impact on Māori. Land. 8(10):152–170.

- Nash S, Jackson W. 2020. Increase to supplier diversity through new procurement target for Maori Business. The Beehive. [accessed 2022 Dec 07].

- New Zealand Government. 2018. Cabinet Circular CO (18) 2: Proposals with financial implications and financial authorities.

- O’Regan T. 2014. The economics of Indigenous survival. [Video]. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YXuh8jerjXg.

- Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. 2021. Wellbeing budgets and the environment: a promised land? [accessed 2022 Dec 09]. https://www.pce.parliament.nz/media/197166/wellbeing-budgets-and-the-environment-report.pdf.

- Parsons M, Fisher K, Crease RP. 2021. Decolonising blue spaces in the anthropocene: freshwater management in Aotearoa New Zealand. Springer Nature.

- Rashbrooke M. 2021. Too much money: how wealth disparities are unbalancing Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books.

- Rogers P, Humble R, Helman Z, Funnel S, Scougall J, Hassall K, Tyler P, Elsworth G, Kimberley S, Stevens K. 2008. Evaluation of the stronger families and communities strategy 2000-2004: final report. In: In RMIT University. CIRCLE: RMIT University.

- Ruckstuhl K, Short S, Foote J. 2021. Assessing the Labour Government’s new procurement approach through a Māori economic justice perspective. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work. 33(4):47–54.

- Scobie M, Love T. 2019. The Treaty and the Tax Working Group: tikanga or token gestures? Journal of Australian Taxation. 21(2):1–14.

- Scobie M, Sturman A. 2020. Economies of mana and mahi beyond the crisis. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations. 45(2):77–88.

- Squamish Nation. 2021. Squamish Nation Annual Report 2020/2021. [accessed 2023 Mar 29]. https://www.squamish.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Squamish-Nation-Annual-Report-2020-2021_FINAL.pdf.

- Stats NZ. 2022. Local authority financial statistics: year ended June 2021. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/local-authority-financial-statistics-year-ended-june-2021/.

- Tau T. 2015. Brief of evidence of Rawiri Te Maire Tau for Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Ngā Rūnanga [2458/2821]. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. http://www.chchplan.ihp.govt.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/2458-TRoNT-Ng%C4%81-R%C5%ABnanga-Evidence-of-Te-Maire-Tau-5-11-2015.pdf.

- Tax Working Group. 2019. Future of tax: final report — volume I: recommendations. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://taxworkinggroup.govt.nz/resources/future-tax-final-report.

- TDB Advisory. 2022. Iwi investments report. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.tdb.co.nz/iwi-investment-2021/.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2021a. He Ara Waiora. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/he-ara-waiora.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2021b. History of the LSF. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/history-lsf.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2022a. Budget 2022 data from the estimates of appropriations 2022/23. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/data/budget-2022-data-estimates-appropriations-2022-23.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2022b. Budget at a glance. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/system/files/2022-05/b22-at-a-glance.pdf.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2022c. Māori Affairs Sector - the estimates of appropriations for the Government of New Zealand for the year ending 30 June 2023. [accessed 2023 Mar 23]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/budgets/maori-affairs-sector-estimates-appropriations-government-new-zealand-year-ending-30-june-2023.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2022d. Measuring wellbeing: the LSF Dashboard. [accessed 2023 Mar 28]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/measuring-wellbeing-lsf-dashboard.

- The Treasury New Zealand. 2022e. New Zealand Sovereign Green Bond Framework. [accessed 2022 Dec 07]. https://debtmanagement.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media/media_attachment/nz-sovereign-green-bond-framework.pdf.

- Trans-Tasman Resources Limited v The Taranaki-Whanganui Conservation Board. 2021. NZSC 127.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 2014. Report on Stage 1 of the Te Paparahi o Te Raki Inquiry Released. [accessed 2023 Mar 23] https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/news/report-on-stage-1-of-the-te-paparahi-o-te-raki-inquiry-released-2/.

- Wakefield EG. 1849/1914. A view of the art of colonization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Willmott K. 2022. Taxes, taxpayers, and settler colonialism: toward a critical fiscal sociology of tax as white property. Law & Society Review. 56(1):6–27.

- Yellowhead Institute. 2021. Cash back. [accessed 2022 Dec 05]. https://cashback.yellowheadinstitute.org.