ABSTRACT

Māori, as substantial stakeholders in the fishery sector, must play a major role in any imagined or proposed transition to a blue economy. This paper provides the results from a project examining how to indigenise the blue economy in Aotearoa New Zealand, outlining the underlying theory and providing results from five case studies. The paper explores three key thematic constraints identified in consultation with the Māori fishing sector, namely: centralisation of power; quota fragmentation; and product commodification. It concludes that there is a need to focus on: redressing the imbalance between iwi and hapū by providing quota for hapū while providing wrap around financial and capacity support, incorporating local experts in decision making, and creating community clusters; overcoming fragmentation through joint ventures and hybrid governance structures and a focus on quota optimisation; and increasing market differentiation through research, innovation, and branding and marketing initiatives.

Introduction

A key government aim in Aotearoa New Zealand is a transition towards a sustainable, low-emission, and resilient economy (Blaschke Citation2020). As part of this change, the government launched the decade long National Science Challenges in 2014 to tackle the biggest science-based issues and opportunities facing the country. Sustainable Seas was one of these Challenges. Its mandate was ‘enhancing the use of marine resources within environmental and biological constraints’ (Lewis and Le Heron Citation2022, p. 101). Over time, Sustainable Seas (the Challenge) focused on the blue economy, with attention given to Māori rights and interests. As part of the Challenge, the Indigenising the Blue Economy project explored the blue economy from a te ao Māori (Māori worldview) perspective, building on several preceding projects conducted by the authors for the Challenge. This paper presents the findings of this final project.

The paper begins by outlining the methodology used, describing the iterative research process that covers several preceding projects as well as the innovative research structure that saw researchers selected from the case study communities, providing insights an outsider could not achieve. The focus is then directed on the results. The paper examines both the constraints and the suggested solutions individually. Here the key findings of the project are outlined across the five different case studiesHere t. Finally, the paper provides a discussion and conclusion, detailing what is required to ‘indigenise’ the blue economy in Aotearoa as well as providing international insights.

Methodology

This research has been conducted through an iterative process involving multiple sequential projects for the Challenge, with all projects led by two Māori scholars with deep expertise in Indigenous socio-economic development and strong connections with the MME and Māori organisations across the two motu. The final Challenge project builds on insights gained from previous research. The initial phase explored Māori-led innovations grounded in mātauranga (Māori knowledge) that might facilitate Māori participation in marine management, ensuring the long-term profitability and sustainability of the Māori marine economy (MME). The research encompassed a literature review, which delved into the historical foundations of the MME and examined the alignment between mātauranga Māori and ecosystem-based management (EBM). Additionally, a mapping of the institutional structure and value of MME assets was completed. Case studies with Ngāi Tahu Seafood, Moana New Zealand, Iwi Collective Partnership, Ngāti Kahungunu, Whakatōhea, and Aotearoa Clams were also conducted.

Subsequent research involved a political, economic, social, technological, legal, environmental (PESTLE) analysis of the MME as a precursor to the present study on which this paper reports. Stakeholders across the MME were engaged in kōrero (conversations) to ascertain the constraints that Māori encountered in the sector. Those engaged included board members on iwi rūnanga (tribal councils), localised hapu-scale marae (sub-tribal meeting houses) and komiti (committee) representatives, iwi-owned fishing companies, national-level Māori fishing organisations, Māori marine scientists, and Māori fishers. Their insights primarily centred on practical constraints. These constraints fall into three broad categories of concern: centralisation, fragmentation, and commodification. These will be expanded upon in the results section, but in brief, centralisation involves the consolidation of assets such as fishing rights, creating social and cultural tensions across whānau (extended family), hapū (subtribe), iwi (tribe) and pan-iwi (multitribal) scales. Fragmentation refers to the division between customary and commercial Māori fishing rights, which has arisen from the effects of fisheries settlement legislation, the unequal allocation of commercial quota by the Quota Management System (QMS), and the compartmentalisation of the marine estate, here broadly understood as the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) from a common right to fish to individual transferable quota (ITQ) (Joseph et al. Citation2019). Fragmentation also adversely affects sustainable marine ecosystem management because it divides ecosystems up into single species (McCormack Citation2017). Commodification refers to prioritising low-value, high-volume fishing as a consequence of the QMS, which it has encouraged industry consolidation (Lewis et al. Citation2020). While economically sound for quota holders, commodification precludes Māori from more active roles in fishing and marine resource management.

These constraints on the Māori marine economy can be traced to settler colonial laws and customs used to usurp Māori power and divert Māori resources, including the marine estate, to the Crown and its agents (Mika Citation2020). The instrument used to effect this change in fortunes was the Treaty of Waitangi or te Tiriti o Waitangi as the Māori text is known, signed in 1840 between Māori chiefs and the British Crown. While the treaty is now regarded as the founding document of the modern state of Aotearoa New Zealand, its promises to protect Māori rights and interests in their lands, fisheries, forests, and other treasured possessions were set aside by the colonial government in favour of the arriving settlers (Orange Citation2012). It was not until 1985 when the Waitangi Tribunal was given authority to hear claims for treaty breaches extending back to 6 February 1840 that meaningful treaty settlements could be considered (Waitangi Tribunal Citation1992). It was the government’s proposal, however, to establish an Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) based system in 1986 to more sustainably manage commercial fish stocks that the contention that Māori had not relinquished their marine property rights came to the fore; an argument which the courts upheld (Rout et al. Citation2019). The aim of the quota management system (QMS) was to reduce the number of vessels at sea by making ownership of a privatised commercial fishery access right, or quota, a prerequisite for anyone wanting to sell fish caught in New Zealand waters (Rout et al. Citation2019). The QMS has seen multiple changes, but the fundamental concept of holding ITQ as the right to fish remains the same.

Rather than reinstate Māori ownership interests in the marine estate, the Crown negotiated a treaty settlement that granted Māori fishing quota and other compensations. The settlement quota and other assets were transferred to Te Ohu Kaimoana (TOKM), a statutory entity established to oversee and distribute the quota among iwi. In this context, the institutional framework–particularly the QMS and treaty settlements–plays a significant role in framing the MME’s capacity to transition to a sustainable blue economy. The blue economy concept fits within this transition towards a more sustainable future, though the concept needs to be ‘indigenised’ because of the bicultural underpinnings of Aotearoa and the significant stake Māori have in the marine economy.

Most blue economy definitions revolve around balancing economic, environmental, and social objectives consistent with conventional wisdom on sustainable development as an interplay between competing notions of improving material wellbeing within environmental limits (Voyer et al. Citation2018,). While not an exact one for one match, centralisation, fragmentation, and commodification can be seen as the near antithesis of each of the blue economy’s triple bottom lines of social equity, environmental sustainability, and economic growth. Centralisation has seen the marginalisation of communities, damaging the social fabric, it also has environmental and, more specifically, economic consequences, as wealth is concentrated and decisions are made based primarily on short term gains. Fragmentation is unsustainable on fishing stocks, and is also economically and socially problematic as it creates inefficiencies and inequalities. Commodification trades short term profit for the few over long term wealth for the many, but also has knock on effects on both environmental and social outcomes, as operators seek high volumes to make up for low value and fishing communities miss out. Thus, the institutional framework within which Māori operate in the MME is a significant barrier to the transition to a blue economy.

The concept itself is also somewhat problematic. Scholars have raised concerns about the concept, spanning from mild criticism to severe scepticism. At the mild end, the blue economy has been faulted for being an ambiguous, contradictory, abstract and unusable concept. Part of this ambiguity arises from its diverse definitions. At the critical end, this ambiguity is considered deliberate, allowing the blue economy to serve as a proxy for dominant capitalist interests. Critics argue that the concept is vague, compartmentalised, unsystematic, and contradictory (Winder and Le Heron Citation2017). Schutter et al. (Citation2021) contend that the blue economy can be seen as a new version of the passive revolution initiated by the green economy, further embedding capitalism’s dominance in ocean-related activities. They argue that the blue economy’s underlying profit and growth agenda obstructs fundamental changes necessary for sustainability (Schutter et al. Citation2021). For some proponents, blue economies appear to promise a triple-win scenario where the needs of coastal and island communities, environmental concerns, and capitalist growth can be simultaneously satisfied (Mallin and Barbesgaard Citation2020). Yet, the blue economy poses risks for Indigenous peoples long marginalised by capitalism (Bargh Citation2014; Tiakiwai et al. Citation2017).

Initially, Sustainable Seas defined blue economy as an aspiration, an opportunity to mobilise interest in the concept as a platform for just transitions in marine economy (Lewis Citation2018; Lewis et al. Citation2020; Lewis and Le Heron Citation2022). A final set of blue economy principles, intended to underpin Aotearoa New Zealand’s journey towards a sustainable blue economy, were outlined by the Challenge in 2023:

Intergenerational: Empowering holistic and long-term governance and management that support the moana (the ocean) to provide for economic, social, cultural, and environmental well-being.

Treaty-led: Providing for the application of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the Treaty of Waitangi principles, tikanga (protocols to do what is right), and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge).

Sustainable: Adopting approaches to resource management that improve marine ecosystem health.

Prosperous: Generating economic success and actively transitioning towards resource use that is productive, resilient and enhances ocean-dependent livelihoods and coastal communities.

Inclusive: Engaging communities to realise benefit from marine resources to align with, deliver upon and balance multiple values and uses (both commercial and non-commercial).

Accountable: Making transparent decisions that reflect the value of and impact upon the ocean’s natural, social, and cultural capital (Short et al. Citation2023).

While there is alignment between the new principles of the blue economy and te ao Māori, a truly indigenous blue economy in Aotearoa would further embed te ao Māori.

As part of the Challenge, the Indigenising the Blue Economy project explored the blue economy from a te ao Māori (Māori worldview) perspective. We interpret it to mean taken-for-granted ways of seeing the world are seen instead through an Indigenous lens and articulated through Indigenous experience, words, and meanings. This is encapsulated by the phrase whai rawa, whai mana, whai oranga which refers to, respectively: the pursuit of resources to satisfy human and nonhuman needs; the pursuit of spiritual power, authority, and dignity; and, the pursuit and state of the well-being of Tangaroa (ocean deity) and ngā tāngata (people) (Rout et al. Citation2019). Thus, a blue economy MME must be mana-enhancing, mauri-inducing and kaitiaki-centred, rendered as holistic wellbeing and reciprocal relations between Tangaroa and ngā tāngata as his descendants (Mika et al. Citation2022a).

These insights are built on the four fundamental principles of te ao Māori (Harmsworth et al. Citation2016; Hēnare Citation2016; Rout et al. Citation2019): (1) the belief in a holistic reality where nature and humanity are interconnected and the material and spiritual worlds are inseparable; (2) relationships are paramount and mutually influential; (3) maintaining balance in these relationships is foundational; and (4) time is cyclical, with the past and future being as significant as the present. We contend that these presuppositions not only offer an understanding of what an indigenised blue economy should encompass but also guide the process of indigenising it (Harmsworth et al. Citation2016; Hēnare Citation2016; Rout et al. Citation2019):

Holistic framing emphasises viewing the ocean as a network of relationships rather than just a resource. Ecosystems and species within it should be respected for both their intrinsic worth and instrumental value. Economic considerations should serve natural, social, and cultural outcomes.

Relationships, or mutually shaping interactions and interconnections, are fundamental to the marine estate and cover not just the species and ecosystems within but also broader dynamics including human interaction. Viewing the marine estate as a network of relationships identifies critical connections and their relative importance.

Emphasising balance or dynamic equilibrium sets an ideal outcome for all identified relationships. The ideal balance will vary for each relationship and over time, but all actions and reactions should strive to achieve this balance. This concept does not eliminate financial incentives but rather demands they be built on balanced outcomes.

Recognising the importance of cyclical understanding means that decisions should consider historical insights and future impacts. This involves incorporating cultural practices (tikanga) and local knowledge (mātauranga) to inform current decision making and practices, an emphasis on long-term broad benefits over short-term profit, and a focus on inclusivity and equality across human and non-human domains.

In preparation for the final phase of research, further discussion with stakeholders and Sustainable Seas leaders distilled the constraints into three themes from which a research plan focusing on initiatives and resolutions in each theme, was devised. The themes are: (1) whakatautika–creating a balance between whānau, hapū, and iwi scale entities and activities; (2) auahatanga–generating differentiation in the products, processes, and markets of Māori marine-based enterprises; and (3) pāhekoheko–increasing integration to counteract the problem of fragmentation. These themes were understood as needing to not only overcome the constraints to the blue economy transition but also help to indigenise this transition.

In the research, we partnered with Māori authorities, including iwi and pan-iwi entities, and Māori enterprises, to explore the transition to an indigenised blue economy–working with our partners to build and activate knowledge in real time. These partnerships were crucial in comprehending the constraints and exploring solutions. The five case study partners are shown in .

Table 1. Case study partners.

In each case, the research was organised into two distinct processes and groups. First, a localised approach where senior Māori researchers collaborated with community researchers who may have been an employee of the Māori authority or chosen by them to complete the case studies. The community researcher was primarily responsible for fieldwork and community-oriented communication while the senior Māori researcher guided investigations, analysed data, and developed case study reports. Second, the synthesis team, consisting of Māori and non-Māori research specialists analysed case study data to generate research and practice-based outputs. Each case study employed a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods based on subthemes, including interviews, archival record research, focus groups, desktop analysis, and value chain analysis. In a further innovation, appropriate to working with Indigenous communities on knowledge projects, community researchers conducted interviews, coordinated with Māori authorities for co-development, and facilitated appropriate forms of presentation and framing. Site visits to the Chatham Islands, Tauranga, Akaroa Harbour, and Auckland were an integral feature of the research and relationship-building process.

Results

Centralisation

Centralisation refers to the consolidation of quota at iwi and pan-iwi levels, resulting in reduced local political control and economic involvement. The traditional Māori political unit was the hapū, which held authority over local marine territories (Rout et al. Citation2019). Colonisation disrupted these systems, but Māori never sold their marine property rights (Mika Citation2020). The unresolved legal situation became critical when the government attempted to implement the QMS in the 1980s. The High Court ruled that the government could not allocate rights that still belonged to hapū, leading to a Waitangi Tribunal settlement process (Webster Citation2002). Māori were offered compensatory property rights and assets for supporting the QMS, but negotiations were conducted with the ‘large natural groupings’ of iwi rather than hapū, consolidating the right at a broader than traditional scale (Webster Citation2002). This decision caused significant tension for three primary reasons: first, some Māori do not have as strong an affiliation with their iwi as their hapū; second, several iwi have struggled with localised development; and third, not all Māori affiliate with an iwi, while many have numerous affiliations (Barr and Reid Citation2014; Kukutai and Webber Citation2017; Webster Citation2002). At a practical level, international research has shown better social and economic outcomes when property rights align with traditional Indigenous structures (Cornell and Kalt Citation2000).

To receive settlements, iwi had to adopt Western corporate principles, forming mandated iwi organisations (MIO) to receive and manage settlement assets, which forced MIO to focus on financial returns rather than capacity building and local fishers (Song et al. Citation2018). A separation between MIOs and their asset-holding companies divorced commercial decisions from political, social, and cultural considerations (McCormack Citation2021). Disagreements within Māoridom arose over the apportionment of settlement quota, with divisions between urban Māori and iwi (Mika et al. Citation2022). Some quota remains with TOKM, actively involved in catching and processing fish (Rout et al. Citation2019).

The QMS introduced a centralised quota market that generates higher profits than actual fishing, benefiting incumbent quota holders through economic rent. The abandonment of resource rentals in 1994 allowed economic rents to grow as profits slumped (Torkington Citation2016). Pre-QMS, inshore fishing was dispersed, with Māori playing a significant role. Now, most fishing occurs offshore, with jobs concentrated in South Island hubs. This change in industry structure has disproportionately impacted Māori fishers and their communities, leading to job decline, disconnection from local communities, and loss of fishing expertise. Overall, centralisation has distanced Māori from their fisheries, turning fishing into an abstract right with limited Māori engagement (Reid et al. Citation2019).

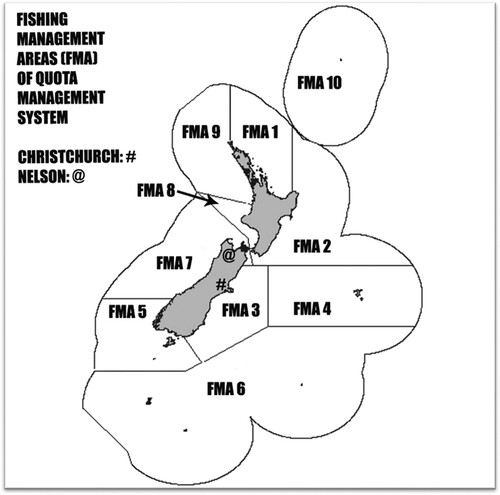

The QMS has also caused geographic centralisation. Pre-QMS, fishing was geographically dispersed and largely inshore, but it has now moved offshore, with Nelson and Christchurch serving as hubs providing access to the Chatham Rise (FMA4), sub-Antarctic (FMA6), and Tasman (FMA7) fisheries, as shown in . The sector has seen a prolonged decrease in job opportunities, with remaining jobs concentrated in hubs situated in the South Island, while most of the Māori population resides in the North Island, further excluding them (Winder Citation2018). Most Māori fishers were excluded from receiving quota because of the stringent criteria, while a report that warned of the ‘devastating impacts’ of such a decision was ignored (Memon and Cullen Citation1992, p. 160). Iwi fish quota holdings have increased over time, even as the number of Māori fishers has declined, highlighting a divide between the centre and the periphery (McCormack Citation2018). In these various contexts, McCormack (Citation2017, p. 42) asks who has benefited from the settlements, and argues that for many Māori they have been ‘virtually non-existent’, especially at the local level.

Figure 1. Map of Fishing Management Areas (FMA) for QMS. Adapted from NIWA map, n.d. (https://niwa.co.nz/media-gallery/detail/109673/42525).

Whakatautika

Ring-fencing quota and ACE

The key cause of the centre-periphery tension is unequal access to fishing rights. Several case studies indicate that one plausible solution lies in ring-fencing quota or Annual Catch Entitlement (ACE) for local, whānau-based fishing operators. In its simplest form, the allocation of commercially viable quota to smaller communities with a substantial history of fishing aligns with traditional Māori fishing rights. Even a modest rectification of this imbalance could significantly restore local connections and participation. Moreover, it offers a means of reinforcing relationships between iwi, hapū and whānau. The ring-fencing of quota can be executed at different levels, including MIO, TOKM, or central government. For instance, Hokotehi Moriori Trust has reserved blue cod, crayfish, pāua, and kina ACE for members already established in fishing, with the allocation either directly from Hokotehi or through agreements with fish processors. This solution can be effectively combined with differentiation strategies, particularly those emphasising community and cultural revival. The objective would be to offset any financial loss resulting from quota redistribution, rendering the solution cost neutral. Although the provision of quota is a substantial solution, it remains relatively risky when pursued in isolation, given the numerous challenges small operators encounter, including commercial and regulatory barriers. It is, therefore, best accompanied by comprehensive support from the MIO and central or local government.

Financial support and mentoring

Financial support and mentoring from MIO, the government, and the public sector, were mentioned by case study participants and are deemed critical for achieving whakatautika. In the case studies from the Chatham Islands, the suggestion was made that the government should offer subsidies to assist fishers in operating their businesses. This is particularly significant for the remote Chatham Islands, where additional operational costs are incurred due to factors such as transportation to markets, storage and packaging expenses, income loss caused by disruptions, and the overall higher cost of operating within a remote island economy, which can be up to three times higher than mainland costs. Subsidies could take the form of removing Goods and Services Tax from operational costs or providing low-cost financing for the acquisition of necessary vessels and equipment. Participants in the Chatham Island interviews also raised the possibility of the government offering guarantees for product loss due to weather disruptions. Hokotehi Moriori Trust has initiated the distribution of grants to contribute to the cost of compliance for mandatory electronic monitoring required on fishing boats. Moana New Zealand also provides insights into the form such support might take, as they have implemented a strategy to assist whānau fishers. Moana has underwritten the construction and refurbishment of two fishing vessels for RMD Marine Limited (RMD), a whānau fishing company. Moana New Zealand views this initiative as an opportunity to fund the upgrading of fishing fleets. This partnership yields mutual benefits, as the new vessels employ precision seafood harvesting technology, aligning with Māori sustainability values and enabling value addition. RMD’s fleet enhancement increases their equity and capacity to acquire more vessels and gear. The partnership secures Moana New Zealand a multi-year contract with RMD to catch all its iwi quota packages. RMD recognises the invaluable experience and knowledge Moana New Zealand brings and views the partnership as a relationship. Moana envisions this as the initial phase of a broader strategy aimed at fostering a network of whānau fishing companies that actively engage in fishing Māori quota in alignment with te ao Māori, building networks of mutually-beneficial and balanced relationships.

Community clusters

An additional solution, identified in multiple case studies, involves establishing community business clusters that can integrate into local and national value chains. While these solutions need not replicate the scale of Nelson, the sole region in Aotearoa with a substantial marine cluster, they can be developed in smaller, more niche ways. Creating a cluster similar to the size of Nelson may be unnecessary and counterproductive to the focus of whakatautika, which requires smaller, more localised solutions built on mātauranga and tikanga and tailored to whānau and hapū scales. Moana New Zealand is actively working to establish a cluster of whānau fishing businesses from harvesting to processing. Moana New Zealand’s aquaculture division is collaborating with contract growers on long-term arrangements. This allows Moana New Zealand to geographically expand while assisting Māori to establish and grow their businesses. As local business owners and operators, contract growers provide work opportunities and on-the-job training and development, in addition to accessing Moana New Zealand’s capabilities. Another idea in several case studies is utilising waste produced by fish processing in other businesses. Hokotehi Moriori Trust are determining the feasibility of a composting project, that would include fish waste, to manufacture compost, potting mix, and other products.

Local experts

The Iwi Collective Partnership (ICP) has identified a valuable solution, involving the active engagement of local experts in centralised decision-making, part of a broader grouping they have labelled ‘implementation agents’ which include are (a) ICP, (b) ICP iwi members, (c) ICP's partners, (d) mātauranga experts, (e) industry experts, (f) scientists, and (g) Tangaroa and Hinemoana (the atua or gods of the ocean). This strategy is being applied in their Kia Tika Te Hī Ika (KTTHI) project. The goal of this initiative is to explore the integration of mātauranga and tikanga within fisheries operations, which local experts can help with. This development is achieved through collaborative and consensus-based processes that align with traditional Māori decision-making principles. This approach has potential to yield multiple outcomes, one of which is the restoration of balance between the central and peripheral decision-making. By providing a platform for local experts across ICP’s membership to offer insights into the collective’s operations, this process ensures that local voices are heard and influence decision-making on a broader scale.

Fragmentation

Fragmentation is the division of a sector, institution, or entity into inefficient or even conflicting components. The root cause of this problem is the allocation of Māori fishing rights, including commercial and customary rights. Commercial rights, known as settlement quota (SET), were distributed among 58 iwi. However, these allocations were considerably less than required to sustain Māori engaged in pre-QMS inshore fishing. Most iwi lack sufficient quota for commercial fishing, with quota packages primarily consisting of high-volume, low-value species. Consequently, many iwi lease their quota to commercial operators, with only 8% actively fishing (Reid and Rout Citation2020).

Iwi are only able to trade their quota to other iwi under specific regulations, limiting quota consolidation into commercially viable bundles. No SET sales have taken place since 2004 (McCormack Citation2018). Day and Emanuel (Citation2010) have calculated that up to 30% of the value is lost because of these quota trading restrictions. The wider sector has seen significant quota consolidation, as big companies have come to dominate. Quota fragmentation has given rise to three types of quota holders: large Māori fishing companies employing a consolidation strategy, smaller Māori joint ventures that combine iwi quota into commercially viable bundles, and iwi that lease quota (McCormack Citation2018). SET fragmentation, in essence, has led to both commodification and centralisation.

The regulations define customary fishing as an activity devoid of any commercial aspects, pecuniary gain, or trade, with a specific exclusion of ‘barter’ due to its use in financial transactions. The exclusion of barter fundamentally disconnects the right from historical Māori fishing practices, where barter was commonplace in pre-QMS fisheries and continues to be a method of exchange within the broader customary food gathering economy. The Māori fisheries settlement has, in effect, resulted in the fragmentation of Māori rights and the emergence of structural tensions. This is evident in the dichotomy between iwi overseeing commercial quota and customary rights being vested with hapū and marae (Memon and Kirk Citation2011; Te Ohu Kaimoana Citation2018).

Marine and coastal policy in Aotearoa suffers from extreme institutional fragmentation. As Macpherson et al., (Citation2021, p. 4) explain, embedded in 18 main statutes, 14 agencies, and six government strategies it is ‘fragmented, ad hoc, and sometimes inconsistent across maritime planning, regional planning and fisheries management.’ This creates friction for Māori when operating in the marine estate, exacerbated by the roles Māori have across commercial, political, and cultural realms.

The QMS also fragments fish and ecosystems by dividing the ocean into separate ‘resource zones’ and managing species independently, which has resulted in unsustainable outcomes despite the system being promoted as having significant environmental benefits (McCormack Citation2017). The QMS is essentially a single-species management system, independently setting annual commercial catch (TACC) and quota shares for each species, leading to ecological fragmentation (McCormack Citation2017; Reid and Rout Citation2020b).

Pāhekoheko

Joint ventures

Joint ventures is one strategy for addressing fragmentation. This strategy involves pooling quota to create commercially viable quantities. ICP is a noteworthy model. During formation, ICP members developed a strong collective vision that delineated their objectives and requirements. Substantial voluntary work was undertaken to facilitate the unification, demonstrating the significance of long-term planning and a focus on relationship building. Geographical proximity between the members of ICP was a beneficial factor for fostering collaboration, as it signifies a shared history and common tikanga. This relationship among members provided a basis for cooperation, underlining the importance of shared vision and tikanga as a foundation for joint ventures. According to their model, ICP iwi members maintain ownership of the quota, while ICP manages and administers their ACE. ICP itself does not engage in fishing. Instead, ICP’s commercial partners fish this quota, with many of these commercial partners being partially owned by ICP iwi. The aggregation of iwi ACE through ICP yields benefits for ICP iwi members, including economies of scale, mitigating fragmentation, enhancing revenue, and providing for those members who lack the capital to fish their quota independently. Furthermore, participating in ICP reduces competition between iwi members. Iwi that own or partially own ICP partner companies also benefit from the dividends generated. ICP actively promotes sustainable fishing practices through its partnerships, ensuring that iwi members gain knowledge and capabilities that contribute to their active participation in the fisheries industry. ICP’s governance structure includes six directors, with three appointed by the three largest iwi shareholders and three elected by the remaining nine shareholders. This governance model provides security for larger partners while engaging smaller partners.

Quota optimisation

Optimising existing quota is another useful strategy to address fragmentation. Moana New Zealand has been at the forefront of developing technologies and practices aimed at improving the quality and timeliness of fishing operations. Moana New Zealand’s investments include establishing in-house Geographic Information System mapping capabilities and software to predict fishing locations, thus streamlining the fishing process and minimising environmental impacts. Additionally, Moana New Zealand has invested in precision seafood harvesting technology, enhancing catch selectivity and, consequently, catch quality. These measures enhance returns, especially after the technology investments have been recouped. In a similar vein, the Chatham Island case studies have focused on revitalising traditional Māori knowledge to improve operational efficiency. Both Chatham Islands case studies have worked on reviving mātauranga pertaining to fishing practices and operations. For Moriori, the preservation of this knowledge is crucial as it is embedded in their own language. They have undertaken the collection of traditional knowledge related to various critical fish cycles and behaviours to enhance the efficiency and sustainability of their catches.

Hybrid governance structures

Another response to fragmentation found in the case studies involves the adoption of hybrid governance structures. These are structures that incorporate elements of traditional Māori socio-economic arrangements, such as flexible, adaptive, and distributed networks, non-hierarchical leadership, consensus decision-making, and specialised input into decision-making (Rout et al. Citation2019). While these structures may not directly resolve fragmentation, they serve as facilitators for solutions and strategies. An exemplar can be seen in ICP’s Kia Tika Te Hī Ika project. In this project, the idea is to include implementation agents in the decision-making process, which provides adaptative capacity for evolving contexts. As noted above, there are a number of different implementation agents, including (a) ICP, (b) ICP iwi members, (c) ICP's partners, (d) mātauranga experts, (e) industry experts, (f) scientists, and (g) Tangaroa and Hinemoana. These hybrid structures also incorporate experts into decision-making processes, aligning with traditional practices of involving tohunga (experts) and community members in decision-making. This focus on kotahitanga (unity) by involving all stakeholders, even the atua, can provide an overarching pāhekoheko. Moana New Zealand, for its part, has been developing a networked approach to its business, focusing on establishing semi-independent Māori-owned businesses that operate collectively while retaining a degree of autonomy. Moana New Zealand have been actively supporting suppliers and contractors to establish their businesses through access to Moana New Zealand’s knowledge, expertise and innovations. This model resembles traditional Māori economic organisational structures, which optimised distributed yet interconnected governance groups, and offers resilience through relationship building and rebalancing centre-periphery relations and functions. The Chatham Islands case studies underscore the importance of adapted forms of governance and management, emphasising collective and holistic approaches both on island and with mainland networks. The participants in the Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri and Moriori case studies have recognised the necessity of a whole-of-island and integrated approach that involves various stakeholders, such as the Chatham Islands Council, Chatham Islands Enterprise Trust, and government agencies.

Commodification

The commercialisation of marine resources is characterised by a focus on a low-cost, high-volume approach that sees product sold without differentiation and with no value adding strategy (Reid et al. Citation2019; Rout et al. Citation2019; Mika et al. Citation2022). This commodity-oriented strategy is mainly adopted by larger operators who frequently shift their focus from one species to another as stock levels decline, with smaller operators driving innovation (Reid and Rout Citation2020b; Rout et al. Citation2019).

Māori hold a 35% interest in the seafood industry by value, having doubled their economic stake since settlement. However, 45% of this value is concentrated in just four species (koura [rock lobster], pāua, snapper, and hoki), three of which are highly vulnerable to climate change (Reid et al. Citation2019). In contrast, many iwi possess substantial low-value quota, and there has been a lack of research and development to bring these assets into profitable markets. The wild fisheries sector, the most profitable, faces limitations due to quota restrictions, with export volumes growing at a mere 0.2% per year, thus imposing a significant constraint on future expansion (Inns Citation2013). The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) (Citation2017) predicts minimal opportunities for significant volume or throughput growth.

Following the introduction of the QMS, the industry underwent significant consolidation. With the tradability of quota, large companies began acquiring commercially unviable quota, while smaller holders faced difficulties in using their quota as collateral. Within 15 years, most fishers receiving less than 20 tons per annum had sold to larger corporations, causing fish prices to plummet and leading to another round of consolidation (Torkington Citation2016). Presently, around 75% of quota by volume is owned by just eight companies, thus reducing competitive pressures that could drive innovation (Rout et al. Citation2023). This consolidation also impedes the development of value chains and restricts market linkages between smaller-scale fishers and independent buyers seeking high-value, quality fresh fish. Consequently, the industry is trending towards high volume, low value production, resulting in declining returns, decreased employment, and the loss of rents to international owners, causing regional decline (Lewis et al. Citation2020).

Commodification is further driven by the international market, where over 77% of New Zealand's seafood is sold but only 0.3% of the total direct value added to the New Zealand economy. A substantial portion of the country’s seafood exports consist of unprocessed frozen fish and fish fillets, both representing the lowest value seafood categories. Chilled (fresh) fish, among the highest value ways to export finfish, accounts for just over 8% of exports. To exacerbate matters, a considerable portion of New Zealand-caught fish is processed in China (Norman Citation2016). This scenario leaves few alternatives other than selling the fish as landed or seeking more efficient offshore processing (Rout et al. Citation2023).

Another factor nudging iwi towards a commodity strategy is the lack of internal capacity to actively engage in fishing operations or create value chains. Leasing quota enables iwi to achieve high returns with minimal effort (Memon and Kirk Citation2011). With the exception of some smaller Māori operators, there is limited emphasis on branding, traceability, authentication, and other approaches that would foster the creation of value chains (Rout et al. Citation2019). Notably, there is no overarching New Zealand seafood brand or a comprehensive system to trace and verify the origins of exported fish (Norman Citation2016). Although recent efforts have aimed to add value through Indigenous branding and values-centred business practices, these endeavours remain largely unrealised, with the majority of fish caught being sold undifferentiated, resulting in limited additional value (Rout et al. Citation2019).

In some ways, aquaculture–the main case study in this section–escapes the issues raised here. It is not governed by the QMS, so the sector is not constrained or shaped by this system, and has consequently not seen consolidation. Also, the sector has no ‘quota’ though the consent process acts as a similar limitation to growth. As a relatively high premium product, salmon is able to capture value in ways that other species cannot. Still, as detailed in Whitehead et al. (Citation2023), the sector, and our case study, face restrictions that auahatanga can help them overcome, including limited market penetration and lack of consumer awareness.

Auahatanga

Market research

Market research is vital for increasing premiums. Akaroa Salmon were interested in understanding how they could add value by diversifying their markets and targeting the best consumer segments. Thus, the market research focused on both analysing market opportunities and determining consumer willingness to pay (WTP) (Whitehead et al. Citation2023). The research identified opportunities for Ōnuku in terms of new markets. Currently, the Aotearoa New Zealand salmon industry is concentrated in the United States and China markets. This exposes the sector to risk from adverse geopolitical, trade, and market conditions. The trade modelling conducted during this research revealed promising new markets such as Korea and Thailand that could reduce risk exposure. The research also identified consumer attitudes towards salmon and associated WTP premiums for a variety of different ‘credence attributes’, or intangible qualities of the product such as who produced it, what methods were used producing it, and where it was produced. This analysis, combined with insights into the values and competencies of Ōnuku and Akaroa Salmon’s current identity, provided us with a foundation to construct a potential brand identity for Ōnuku in the salmon industry. The identity emphasises authenticity, quality, people, and place in a way that is unique to Ōnuku. This unique identity within Aotearoa New Zealand’s salmon industry allows for a highly differentiated product offering. It also helps Ōnuku build relationships internationally by communicating essential information to a broad array of consumers, while also utilising mātauranga and tikanga.

Branding and marketing

The case studies also focused on branding and marketing, particularly Akaroa Salmon. Working with Ōnuku, a triangulation of their values, market opportunities, and consumer WTP for credence attributes allowed for development of a salmon brand identity that is uniquely Indigenous yet caters to international consumer preferences. This identity revolves around a framework designed to enhance reputation linked to enterprise strategy, differentiation, communication, and interaction. The export market analysis alongside the willingness to pay research culminated in a product identity strategy to differentiate Ōnuku products in market. below outlines this identity based on research and discussions with Ōnuku representatives.

Table 2. Identity attributes of a salmon product from Ōnuku.

Linkages between the identity attributes in and reputational characteristics such as trustworthiness, responsibility, and performance could be useful in guiding Ōnuku in the salmon industry. One reputational area in which Ōnuku need to be careful is potential conflict between an brand identity built on kaitiakitanga and sustainability clashing with perceptions of aquaculture. It could certainly be argued that aquaculture is more sustainable than wild harvest, Ōnuku, the rūnanga are already examining the possibility of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture and broader approaches that consider the potential issues around aquaculture sustainability and branding market issues are also being developed. Moriori are also interested in creating a distinct Rēkohu brand for fisheries products to highlight their heritage and values. Such differentiation, as evidenced by the Ōnuku case study, suggests that communicating Indigenous values to premium consumers can prove advantageous. The data indicate that by focusing on innovative practices, potential economic opportunities akin to those leveraged by Ōnuku in the salmon market could be realised. The identity strategy for Ōnuku in salmon emphasises authenticity, quality, people, and place. The differentiation offered by this strategy appears significant. Nevertheless, communication, especially targeting international audiences, remains an area needing attention. Effective communication paired with an understanding of consumer preferences, may offer avenues to enhance returns. Yet, caution is advised in the findings given the dynamism of markets.

Innovation

Innovation is an essential means of differentiation and generating additional value. Moana New Zealand has been innovative in their aquaculture division, investing significantly in their oyster hatchery, Kirikiritātangi, and broader oyster farming infrastructure. Kirikiritātangi will provide end-to-end control of the oyster growing process, which will increase the consistency and reliability of spat supply. This investment supports the company’s growth in the blue economy aquaculture space. Most oyster spat is still harvested in the wild, providing Moana New Zealand with an edge as they are able to selectively breed their spat and can do it year-round. Moana New Zealand is also replacing timber oyster farming infrastructure and replacing it with semi-automated farming technology, which includes floating oyster baskets on longlines. This not only provides better working conditions but also has less impact on the environment. Entering into mutually beneficial partnerships has meant Moana New Zealand is leading the way in single-seed oyster farming. They are working on research, working in a shared space with a patented Cawthron Institute Research method for producing an all-season oyster. This innovation means Moana New Zealand is one of only three or four businesses globally that has a fully integrated oyster business. Alongside this innovation enabling auahatanga, it is also helping to provide whakatautika as the oyster farms are spread across Aotearoa New Zealand, which are not limited by quota. Hokotehi also indicated the importance of innovation through diversification, noting that marine tourism presents potential opportunity for gaining premiums. Preliminary findings suggest that establishing a marine tourism offering, distinguished as a ‘Moriori experience’, may align with efforts to diversify marine economic activity. Moreover, the exploration of boutique industries, notably paua jewellery branded with Moriori insignia and the exploration of Kaeo's medicinal potential, is recommended. Such industries, if realised, could tap into a segment of consumers who indicate a preference for products associated with Indigenous values, seeing mātauranga and tikanga used to guide innovation.

Discussion and conclusion

Te ao Māori is grounded in the belief that reality is holistic, relational, balanced, and cyclical. While the solutions outlined here were derived from the case study participants, they all align with at least one of these four key beliefs, as shown in :

Table 3. Solution alignment with te ao Māori beliefs.

It is important to ensure that any solutions proposed for indigenising the blue economy need to align with at least some of these core beliefs. However, while on their own these initiatives discussed are likely to help move Aotearoa to towards an indigenised blue economy, it is believed the full benefits will only be realised if the initiatives are implemented in a coordinated manner and then locked into economic practices or institutionalised into iwi-hapū-government relations. However, they are an important first step because they connect practical responses to constraints to an alternative and formative metaphysical economic reality. Significantly, the various initiatives suggested by our respondents as ways of overcoming the constraints they face have a coherence and complementarity that begins to define an indigenised blue economy. That is to say, that viewed together, or as a set of connected, in some case sequential, steps, a number of these solutions can and should be deployed together as they provide a relatively cohesive strategy.

For example, ring-fencing quota, providing financial support, and mentoring are critical co-solutions, and ones that can be delivered by Māori organisations working together through traditional social relations and practices. Most whānau-level fishing operators would benefit from capacity building and economic support to effectively utilise their quota. Taking it a step further, embedding these whānau-level businesses into community clusters also makes sense. Cooperatives of this sort provide a critical mass of connected businesses providing shared opportunities and resilience–they promise to resolve the consolidation-localisation tensions in a productive and Indigenously authentic local-up manner. Mandated iwi organisations and government could focus on creating value chains based around these clusters, with an emphasis on not only improving economic outcomes but environmental and social outcomes consistent with the evolving notion of a blue economy. These clusters would also benefit from hybrid governance and management structures, incorporating local knowledge, and building on authentic local provenance and practice. Such ‘Indigenous clusters’ can be driven by localised knowledge and innovation and fostered by hybrid structures, which provide branding and marketing opportunities that emphasise cultural revitalisation among other favourable attributes of an indigenised blue economy.

In practical terms, indigenising the blue economy requires a concrete roadmap that positions Māori in governance and management roles and incorporates te ao Māori, ensuring both political authority and philosophical influence. In terms of the political aspect, our claim is that Māori should play a significant role in governing and managing the blue economy from planning to operation. However, determining the meaning of ‘significant’ is complicated. This needs to be worked through against a background in which Māori are already offering operational examples of governance in various sectors and playing significant roles in decision making in business and government. They are already demonstrating the potential of an indigenised blue economy, yet there is some distance to go to fully realising this potential. If indigenisation is a process of transformation over time, a process of transition, then it will involve initiatives to actualise a transition. The initiatives outlined in this research project are important steps, which materialise the aspirations and viewpoints of Māori economic actors. Taken together, they promise a complementarity among social, cultural, economic, and environmental goals and efficiencies in scale and scope. In terms of efficiency, profitability and sustainability, Māori collaboration can bring balance, integration, and value, akin to empowering local communities for premium gains in a way that emphasises the intrinsic value of Tangaroa.

From an international Indigenous perspective, there are several potential insights for transitioning to a blue economy. The first, and most fundamental, would be that any solution needs to be based on the Indigenous worldview. This is fairly obvious, though these solutions must also be guided by a strong understanding of the current constraints and future goals. They need to be ‘contextually calibrated’. That leads to the second insight, that some of these specific solutions may not be right for different Indigenous peoples as their situations are probably quite different. Māori are in a fairly unique position in terms of the QMS, SET quota, and MIO, with many Indigenous peoples likely wishing for same the return of fishing rights–even if it comes with the associated issues outlined here. That said, the work done across these different projects will hold a number of useful approaches and solutions for Indigenous peoples around the world depending on their circumstances. Hopefully as time goes on, Māori can continue to blaze a path towards a fuller restoration of Indigenous relationships with the ocean.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bargh M. 2014. A blue economy for Aotearoa New Zealand? Environment, Development and Sustainability. 16:459–470.

- Barr T, Reid J. 2014. Centralized decentralization for tribal business development. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy. 8(3):217–232. doi:10.1108/JEC-10-2012-0054.

- Blaschke P. 2020. Integrated land use options for the Aotearoa New Zealand low-emissions ‘careful revolution’. Policy Quarterly. 16(2): 26–34.

- Cornell S, Kalt JP. 2000. Where’s the glue? Institutional and cultural foundations of American Indian economic development. The Journal of Socio-Economics. 29(5):443–470. doi:10.1016/S1053-5357(00)00080-9.

- Day C, Emanuel D. 2010. Lack of diversification and the value of Maori fisheries assets. New Zealand Economic Papers. 44(1):61–73. doi:10.1080/00779951003614073.

- Harmsworth G, Awatere S, Robb M. 2016. Indigenous Māori values and perspectives to inform freshwater management in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Ecology and Society. 21(4):9–24. doi:10.5751/ES-08804-210409.

- Hēnare M. 2016. In search of harmony: indigenous traditions of the Pacific and ecology. In: Jenkins WJ, Tucker ME, Grim J, editors. Routledge handbook of religion and ecology. New York: Routledge; p. 129–137.

- Inns J. 2013. Māori in the seafood sector (fisheries and aquaculture)–the year in review. Māori Law Review, 6. https://maorilawreview.co.nz/2013/06/maori-in-the-seafood-sector-fisheries-and-aquaculturethe-year-in-review/.

- Joseph R, Rakena M, Jones MTK, Sterling R, Rakena C. 2019. The Treaty, tikanga Māori, ecosystem-based management, mainstream law and power sharing for environmental integrity in Aotearoa New Zealand: possible ways forward. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/assets/dms/Reports/The-Treaty-tikanga-Maori-ecosystem-based-management-mainstream-law-and-power-sharing-for-environmental-integrity-in-Aotearoa-New-Zealand-possible-ways-forward/MAIN20TuhonohonoSSeas20Final20Report20Nov202019.pdf.

- Kukutai T, Webber M. 2017. Ka Pū Te ruha, Ka Hao Te rangatahi: Māori identities in the twenty-first century. In: Bell A, Elizabeth V, McIntosh T, Wynyard M, editors. A land of milk and honey? Making sense of Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press; p. 71–82.

- Lewis N. 2018. Cultivating diverse values by rethinking blue economy in New Zealand. In: Morrisey J, Heidkamp P, editors. Coastal transitions: towards sustainability and resilience in the coastal zone. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge; p. 94–108.

- Lewis N, Le Heron R. 2022. Experimentation and enactive research. In: Heidkamp CP, Morrissey JE, Duret CG, editors. Blue economy: people and regions in transitions. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge; p. 101–116.

- Lewis N, Le Heron R, Hikuroa D, Le Heron E, Davies K, FitzHerbert S, James G, Wynd D, McLellan G, Dowell A, et al. 2020. Creating value from a blue economy. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/assets/dms/Reports/Creating-value-from-a-blue-economy/Creating-Value-From-A-Blue-Economy-Final-Report.pdf.

- Macpherson E, Urlich SC, Rennie HG, Paul A, Fisher K, Braid L, Banwell J, Ventura J, Jorgensen E. 2021. ‘Hooks’ and ‘anchors’ for relational ecosystem-based marine management. Marine Policy. 130:104561. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104561.

- Mallin F, Barbesgaard M. 2020. Awash with contradiction: capital, ocean space and the logics of the blue economy paradigm. Geoforum. 113:121–132. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.04.021.

- MBIE. 2017. The investor’s guide to the New Zealand seafood industry, 2017. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/94e74ef27a/investors-guide-to-the-new-zealand-seafood-industry-2017.pdf.

- McCormack F. 2017. Sustainability in New Zealand's quota management system: a convenient story. Marine Policy. 80:35–46. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.06.022.

- McCormack F. 2018. Indigenous settlements and market environmentalism: an untimely coincidence? In: Howard-Wagner D, Bargh M, Altamirano-Jiménez I, editors. The neoliberal state, recognition and indigenous rights: new paternalism to new imaginings. Canberra, ACT: ANU Press; p. 273–292.

- McCormack F. 2021. Interdependent kin in Māori marine environments. Oceania. 91(2):197–215. doi:10.1002/ocea.5308.

- Memon P, Cullen R. 1992. Fishery policies and their impact on the New Zealand Maori. Marine Resource Economics. 7(3):153–167. doi:10.1086/mre.7.3.42629031.

- Memon P, Kirk N. 2011. Maori commercial fisheries governance in Aotearoa/New Zealand within the bounds of a neoliberal fisheries management regime. Asia Pacific Viewpoint. 52(1):106–118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8373.2010.01437.x.

- Mika JP. 2020. Precarity, indigeneity and the market in Māori fisheries. Public Anthropologist. 2:82–126. doi:10.1163/25891715-00201003.

- Mika JP, Rout M, Reid J, Bodwitch H, Gillies A, Lythberg B, Hikuroa D, Mackey L, Awatere S, Wiremu F, et al. 2022. Whai rawa, whai mana, whai oranga: Māori marine economy: it's definition, principles, and structure. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/tools-and-resources/mme-principles-structure/.

- Norman D. 2016. Fishing, aquaculture and seafood. Industry Insights. Westpac Institutional Bank. https://rescuefish.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Westpac-Report-March-2016.pdf.

- Orange C. 2012. Treaty of Waitangi. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/treaty-of-waitangi/print.

- Reid J, Rout M. 2020b. PESTLE analysis of the Māori marine economy to identify trends and research themes. Sustainable Seas. https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/ntrc/research/ntrc-contemporary-research-division/contemporary-research-division-publications/MME-PESTLE-&-Findings.pdf.

- Reid J, Rout M. 2020. The implementation of ecosystem-based management in New Zealand–a Māori perspective. Marine Policy. 117:103889. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103889.

- Reid J, Rout M, Mika J. 2019. Mapping the Māori marine economy. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/assets/dms/Reports/Mapping-the-Maori-marine-economy/MME20JMika20Mapping20the20Maori20Marine20Economy20LR_0.pdf.

- Rout M, Lythberg B, Mika JP, Gillies A, Bodwitch H, Hikuroa D, Awatere S, Wiremu F, Rakena M, Reid J. 2019. Kaitiaki-centred business models: case studies of Māori marine-based enterprises in NZ New Zealand. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/tools-and-resources/kaitiaki-centred-business-models-case-studies-of-maori-marine-based-enterprises-in-aotearoa-nz/.

- Rout M, Reid J, Bodwitch H, Gillies A, Lythberg B, Hikuroa D, Mackey L, Awatere S, Mika JP, Wiremu F, et al. 2019. Māori marine economy: a literature review. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/tools-and-resources/maori-marine-economy-a-literature-review/.

- Rout M, Whitehead J, Mika J, Reid J, Wiremu F, Gillies A, McLellan G, Ruha C, Tainui R. 2023. Indigenising the blue economy in NZ - a literature review. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/our-research/indigenising-the-blue-economy/.

- Schutter MS, Hicks CC, Phelps J, Waterton C. 2021. The blue economy as a boundary object for hegemony across scales. Marine Policy. 132:104673. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104673.

- Short K, Stancu C, Peacocke L, Diplock J. 2023. Developing blue economy principles for NZ New Zealand. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/assets/dms/Reports/Developing-BE-principles/Blue-Economy-Principles-Report.pdf.

- Song A, Bodwitch H, Scholtens J. 2018. Why marginality persists in a governable fishery—the case of New Zealand. Maritime Studies. 17(3):285–293. doi:10.1007/s40152-018-0121-9.

- Te Ohu Kaimoana. 2018. Building on the fisheries settlement. Wellington: Te Ohu Kaimoana.. https://teohu.Māori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Building_on_the_Settlement_TOKM.pdf.

- Tiakiwai SJ, Kilgour JT, Whetu A. 2017. Indigenous perspectives of ecosystem-based management and cogovernance in the Pacific Northwest: lessons for Aotearoa. An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 13(2):69–79.

- Torkington B. 2016. New Zealand׳s quota management system–incoherent and conflicted. Marine Policy. 63:180–183. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.017.

- Tribunal W. 1992. Ngāi Tahu sea fisheries report (Wai 27). https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68472628/NT%20Sea%20Fisheries%20W.pdf.

- Voyer M, Quirk G, Mcilgorm A. 2018. Shades of blue: what do competing interpretations of the blue economy mean for oceans governance. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning. 20(5):595–616.

- Webster S. 2002. Māori retribalization and treaty rights to the New Zealand fisheries. The Contemporary Pacific. 14(2):341–376. doi:10.1353/cp.2002.0072.

- Whitehead J, Rout M, Mika J, Reid J, Wiremu F, Gillies A, McLellan G, Ruha C, Tainui R. 2023. Auahatanga from authenticity: maximising opportunities for Akaroa Salmon and Ōnuku Rūnanga. Sustainable Seas. https://www.sustainableseaschallenge.co.nz/tools-and-resources/auahatanga-from-authenticity/.

- Winder GM. 2018. Context and challenges: the limited ‘success’ of the NZ/New Zealand fisheries experiment, 1986–2016. In: Winder GM, editor. Fisheries, quota management and quota transfer. New York: Springer; p. 77–98.

- Winder GM, Le Heron R. 2017. Assembling a blue economy moment? Geographic engagement with globalizing biological-economic relations in multi-use marine environments. Dialogues in Human Geography. 7(1):3–26. doi:10.1177/2043820617691643.