Abstract

Similar to other recent Canadian elections, foreign policy did not feature prominently in the 2011 federal election campaign. In fact, many doubt Canadian public opinion on international affairs is linked to the actions taken by recent Governments. In this paper, we examine Canadian public opinion toward a range of foreign policy issues and argue that the survey questions measure two latent dimensions —militarism and internationalism. Our survey evidence indicates the existence of an “issue public” which is prepared to endorse military action and is skeptical of human rights and overseas aid programs, and this group is far more supportive of Prime Minister Harper and the Conservative Party than other Canadians. The absence of an elite discussion, either among politicians or between media elites, about the direction of Canadian foreign policy does not prevent the Canadian voter from thinking coherently about questions pertaining to this issue domain and employing these beliefs to support or oppose political parties and their leaders.

De même que dans d'autres campagnes électorales canadiennes, la politique étrangère n'a pas émergé comme thème prédominant dans la campagne électorale du scrutin fédéral de 2011. En fait, nombreux sont ceux qui doutent que l'opinion publique canadienne soit influencée par les actions des gouvernements récents en ce qui concerne les affaires internationales. Dans cet article, nous examinons l'opinion publique canadienne vis-à-vis d'une série de thèmes de politique étrangère et soutenons que les questions de notre enquête permettent de mesurer deux dimensions latentes – le militarisme et l'internationalisme. Les données de notre enquête révèlent l'existence d'un groupe d'intérêt (issue public) qui est préparé à approuver toute action militaire et est sceptique quant aux programmes de défense des droits humains et d'aide internationale, et que ce groupe est bien plus favorable au Premier Ministre Harper et aux conservateurs que le sont les autres Canadiens. L'absence de débats parmi les politiciens ou les élites médiatiques n'empêche pas à l’électeur canadien de réfléchir de manière cohérente à des questions relatives au domaine discuté ici, et de se baser sur ces croyances pour soutenir les partis politiques et leurs leaders, ou pour s'y opposer.

The distribution and structure of public opinion on foreign policy issues are not prominent themes in research on Canadian political behavior. Save for matters related to trade policy and relations with the United States, foreign policy attitudes among Canadian elites are often presumed to feature cross-party consensus. Much like their more powerful neighbor to the South, politics in Canada appears to stop “at water's edge”. The national image projected onto the international arena is often of a Canada proud of its place as a middle power and a mature democracy that has a compassionate interventionist outlook on international affairs. The ideal is that the function of Canada's military is to serve the global community on missions focused on peacekeeping, promoting human rights and providing humanitarian assistance (see Hogg Citation2004, Berdahl and Raney Citation2010).

In recent years, it has been asserted by both friends and foes that Prime Minister Stephen Harper and the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) have introduced important changes in the orientation of Canadian foreign policy. As leader of the Canadian Alliance in 2003, the future prime minister challenged what, to some, appeared to be a national consensus in opposition to American President George W. Bush's decision to invade Iraq. Criticized in the 2004 federal election campaign for this stand, Harper has since been more circumspect in expressing his foreign policy views. Still, nuances matter – observers note a decidedly hawkish tone in Harper's speeches on matters of foreign policy. This rhetoric has been accompanied by a willingness to use force in Afghanistan and Libya.

When it comes to pleasing the Canadian public, Harper has multiple constituencies to consider. Ideally, perhaps, the Prime Minster would take the full distribution of Canadian public opinion into consideration when developing his foreign policy stance. However, as a pragmatic leader who likely will seek re-election and wants his party to continue to govern, Harper is apt to be sensitive to the attitudes of two important constituencies. The first are voters who identify with the Conservative Party of Canada. Members of this group are highly likely to cast their ballots for Conservative candidates and some serve in the army of volunteers that helps the CPC run their election campaigns. A second group consists of swing voters who may have sympathy for Harper's vision of Canada's place on the world stage and who may be persuaded to support his party at the polls.

In this paper, we employ national survey data collected shortly before and immediately after the 2011 federal election to answer two questions. First, do people who identify with the Conservative Party have foreign policy beliefs that differ from those of other Canadians? Second, do Canadians' foreign policy attitudes correlate with support for Harper and the CPC? Building on previous research, we designed our survey questions to investigate two dimensions of foreign policy beliefs, which we label militarism and internationalism. Questions related to the militarism dimension capture beliefs that Canada should be willing to use its military (and employ other “realpolitik” instruments of power) to achieve international objectives, whereas questions associated with the internationalism dimension tap views about Canadian efforts to secure a stable peace or a more egalitarian world via what Page and Bouton (Citation2006, p. 239) identify as “justice related, humanitarian foreign policy goals”.Footnote1 In both areas, the survey evidence reveals that the foreign policy positions taken by survey respondents who profess a partisan identification with the Conservative Party are distinguishable from positions taken by those who do not. Multivariate analyses further show that for non-CPC identifiers, the correlations between the two foreign policy dimensions and affect toward the CPC and Harper hold even after socio-demographic factors, attitudes about the state of the economy and domestic political matters are considered. Although foreign policy issues may not factor prominently in most Canadian election campaigns, different beliefs about such issues exist in the electorate and these different beliefs correlate with support for Harper and the CPC.

Foreign policy and Canadian electoral politics: a brief overview

Canadian electoral politics typically features competition over “valence” issues, with Conservatives, Liberals, New Democrats and other parties arguing which of them is best able to achieve the goals shared across the electorate – for example, a strong and stable economy and effective healthcare (Clarke et al. Citation2009). Occasionally, the government's handling of foreign policy issues raises questions about its overall competence, but only rarely are elections fought over the direction of Canada's foreign policy.Footnote2 In their retrospective examination of the prominence of foreign policy in Canadian federal elections, Bow and Black (Citation2008) note that the only instances since World War II where foreign policy received widespread attention were the election campaigns waged by John Diefenbaker in 1963 and Brian Mulroney in 1988. The issue of nuclear weapons gained attention in the former case, while the latter campaign became a national referendum on the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement. More recently, during the CPC's 2006–2008 and 2008–2011 minority governments, the opposition parties did not try to use foreign policy disputes as a lever to force the Conservatives from power or as centerpieces of their election campaigns.

The lack of an explicitly stated policy direction for military and foreign policy and the absence of a meaningful debate that might occur if such policies were put forward have been criticized by commentators, particularly those close to the military. For example, Don Martin (Citation2008) quotes a military officer as criticizing the 2008 “Canada First Defence Strategy” document as doing too much to “arm the Prime Minister with military plans for an election campaign battle” rather than offering a coherent strategy – lest it become fodder for the campaigns of opposing parties. Critics also complain that the low priority accorded to foreign policy issues allows a new government to arrive in Ottawa and simply cancel the plans of a previous one with little notice or debate. Summing up the mood among those interested in having foreign policy issues debated in election campaigns, Martin Shadwick (Citation2011) notes:

Defence policy made a cameo appearance in the 2011 campaign (primarily because of the Harper government's proposed acquisition of 65 F-35 s to replace the veteran CF-18s), but the continued absence of foreign and defense policy, both important and not inexpensive public policy areas, from Canadian federal election campaigns, remains deeply troubling. If one examines the role of defense in the four most recent elections, the tally is a cameo appearance in 2011, near-invisibility in the election of 2008 … , a modest (and rather bizarre) appearance in 2006, and a somewhat more edifying stature in 2004.Footnote3

As suggested by this quotation, differences between the parties, as expressed in their election manifestos, were muted in 2011. The Conservatives were committed to following through on the F-35 fighter jets, the Liberals called for the “mismanaged” project's cancellation and the New Democratic Party (NDP) called for a thorough review in a proposed Defence White Paper. The Liberals and NDP both made explicit reference to ensuring that Canada's armed forces had sufficient resources to accomplish the peacekeeping and humanitarian relief missions they wanted the military to perform. In contrast, the Conservatives emphasized expanding Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Bagotville, the economic contributions of the Canadian aerospace industry and developing ships capable of navigating the Arctic to counter potential threats to Canada's sovereignty in the North.

There is a large literature arguing that the relevance of a specific issue or policy domain to electoral politics is dependent on rival parties or candidates taking distinct positions on a given matter, voters perceiving the differences and citizens believing the issue or domain is salient (cf. Campbell et al. Citation1960, Rabinowitz et al. Citation1982, Fournier et al. Citation2003, Soroka Citation2003, Wlezien Citation2005). Above, we documented the near absence of foreign policy discussions from Canadian political discourse. Further, data from the survey discussed below indicate that less than 1 in 100 respondents considered a foreign policy matter as the most important issue in the 2011 federal election. This suggests that the positions survey respondents take on matters related to Canada's foreign and defence policies are unlikely candidates when it comes to identifying issues that correlate highly with partisan identification or affect toward the parties and candidates.Footnote4 Investigating whether this is the case is our primary task below. Given the relative thinness of research on mass public opinion and foreign policy, however, an overview of how Canadians and citizens in other mature democracies make sense of foreign policy issues is warranted.

Two dimensions of foreign policy attitudes

Research on mass public opinion toward foreign policy and the relationship of these beliefs to party and candidate support long was stymied by the so-called Almond-Lippmann consensus. This “consensus” was based on the assumption that “ordinary people” were incapable of formulating meaningful beliefs about foreign policy and, as a consequence, policymakers would be unwise to heed public opinion on such matters (Lippmann Citation1922, Almond Citation1950). In his famous essay on the “belief systems in mass publics”, Philip Converse (Citation1964) employed American national election study data from the 1950s to codify these pessimistic conclusions about the public. He reported only weak associations among survey respondents' answers to foreign policy questions and even weaker relationships between answers to foreign and domestic issue questions. In light of this research, comparatively few questions about foreign policy topics appeared on major election study surveys fielded in the United States, Canada and elsewhere during the second half of the twentieth century.

In the 1980s, analysts were able to use topic-specific surveys supported by the Chicago Council of Foreign Relations (CCFR) to demonstrate that Americans do have structured foreign policy attitudes (e.g., Wittkopf Citation1986, Citation1990, Holsti Citation1992, Chittick et al. Citation1995). The key move by these researchers was to abandon the assumption that a single overarching dimension structured opinions toward foreign policy. Rather than looking for a single ideological orientation that served as a guide to thinking about issues across various policy domains, these authors instead chose to focus on the patterns in the survey data to uncover the underlying structure to the public's beliefs.

Analysts currently differ about the number of foreign policy dimensions (or factors) that characterize public opinion about foreign policy in various countries. Still, most studies find that questions tapping citizen beliefs about how their country should maintain, expand and use its military abroad fall on a separate axis from questions attempting to ascertain citizen beliefs about how that country should conduct diplomacy or use soft power and other foreign policy instruments that do not involve military force. Echoing previous research, we designate the former concept “militarism” and the latter “internationalism”. Questions in our 2011 national survey, we believe, are reflective of these two concepts.

The presence of multidimensional frameworks structuring citizen views of foreign policy is reported in studies comparing public attitudes in the United States with those in contexts as diverse as Costa Rica (e.g. Hurwitz et al. Citation1993) and Sweden (Bjereld and Ekengren Citation1999). These studies document cross-national differences in the structure and distributions of such beliefs. Explanations for these differences point to variations in “strategic cultures” as well as to varying capacities of the states to project diplomatic pressure and military force (see Kagan Citation2003; Haglund Citation2004).

In the case of Canada, it is unlikely that the beliefs Canadians have about their country's role in the international arena would simply mimic those found in the United States. For example, the American public is depicted as divided over beliefs regarding whether the United States should act alone (unilateralism) or in conjunction with other countries (multilateralism) in the international arena (Chittick et al. Citation1995). The existence of such a belief structure is unlikely in Canada where “going it alone” is neither feasible nor congruent with the practice of Canadian foreign policy over the past 70 years. However, even in the absence of a charged partisan debate, we show below that Canadians do have different ideas concerning the role and size of the military and whether their country should contribute militarily when other western powers are engaged in conflicts abroad. There is also an opinion divide concerning whether Canada should continue its role as an advocate of human rights across the globe, provide forces for peacekeeping operations and generously fund overseas aid.

Given the paucity of research on public opinion on foreign affairs in general, it should not surprise that most existing research on the topic in Canada focuses on trends in responses to single survey questions about specific foreign policy questions rather than patterns of opinion across multiple foreign policy topics.Footnote5 As indicated above, we investigate responses to questions designed to be reflective of the militarism and internationalism dimensions of foreign policy beliefs present in other countries. We document significant differences in responses to these questions among Conservative Party supporters and Canadians who support other political parties. When the seven foreign policy questions on our survey are analyzed, we find that they form valid constructs measuring internationalism and militarism beliefs observed in studies of public opinion in other countries. A person's position on the internationalism and militarism scales correlates with the likelihood that they will support Harper and the Conservative Party.

Data

During the 2011 federal election campaign we asked a representative national sample of 2800 Canadian voters to complete the online Canadian Co-operative Election Survey (CCPES). Shortly after the election, 2059 of these respondents completed a follow-up wave of the CCPES. Respondents were asked a series of questions about the election, the parties and the candidates (e.g., vote choice, party identification, feelings about Stephen Harper and other party leaders) and several domestic issues animating debate in the 2011 election (e.g., desirability of a majority government, condition of the economy, state of the health care system, etc.). The survey also included a number of questions about foreign policy. Responses to these items permit us to compare similarities and differences in opinions about how Canada should conduct itself on the world stage between those who favor the Conservative Party and those who favor other parties and leaders.Footnote6

Militarism

The first group of questions, with the specific wording discussed below, taps respondents' broad beliefs about the necessity of war, the use of the military beyond the immediate need for national defence and support for involvement by the Canadian military in the conflicts in Libya and Afghanistan. Collectively, these questions attempt to measure whether Canadians want their military to go beyond Ørvik's (Citation1973) suggestion that middle-power states should maintain a military just large enough to provide a “defence against help”. This phrase refers to the idea that Canada's armed forces should be strong enough to defend the national borders against aggression without help from the United States but not so large as to tempt politicians to send it on excursions abroad (see also Barry and Bratt Citation2008). We designate militaristic individuals as those who welcome a large military and are willing to see the armed forces deployed beyond Canada's borders.

When aligning itself on questions of military intervention, Canada often has become involved after taking cues from Britain and the United States, something that many of those on the political left in Canada find uncomfortable (Massie Citation2009, McDonough Citation2012). Cooperation and responsiveness to United States/United Kingdom interests places Canada in the middle of a “North Atlantic Triangle”. The concept originally was offered to explain the importance of British and American interests to Canada's emergence as a sovereign state (see Haglund Citation1999), but in modern times, the “Triangle” is more about the commonality of values and security concerns shared by the three countries that they can choose to pursue “above and beyond [the actions taken] by other western democracies” (McCulloch Citation2010–2011, p. 26). For some, Canada's substantial combat role in Afghanistan has been indicative of the three countries' close ties on security matters – although over two dozen nations suffered casualties in this intervention, Canadian forces suffered the third highest number. Canada's involvement in Libya perhaps was even less surprising as France also played a prominent role in advocating action against Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, thereby pointing to a commonality of purpose among the “North Atlantic Quadrangle” of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Canada (Massie (Citation2008/2009).Footnote7

Broad restraints: the necessity of war and use of the armed forces

There is little in Canada's history in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century to suggest Canadians are prone to pacifism. The country contributed more than its share to the military effort in two world wars and also fought actively in Korea.Footnote8 As a middle power, the chances that Canada will unilaterally engage militarily with hostile powers abroad are slim to none. However, since the end of World War II, Canada's military forces have been involved in over 50 missions around the world in conjunction with the militaries of other countries.

Although Canada's forces were participating in over a dozen missions abroad in 2011, Canadians were, at best, lukewarm when it came to deploying the military when the national interest was not at stake.Footnote9 When the CCPES asked respondents if “Canada should not employ its armed forces unless the country's security is directly threatened”, fully 44 per cent agreed that Canada's own security interests should drive the decision to use the military. A large number were ambivalent, with 26 per cent opting for “neither agree nor disagree” or “don't know” responses. Less than one-third (30 per cent) opposed placing such a constraint on the use of military force. On a broader agree-disagree question asking whether “Sometimes going to war is the only solution to international problems”, more disagreed (41 per cent) than agreed (35 per cent), with an additional 24 per cent neither agreeing nor disagreeing or saying that they “didn't know”.

As the results from illustrate, people who identified with the Conservative Party were significantly more likely to disagree with binding the country to using its military abroad only to defend the national interest. The response distributions comparing Conservative identifiers to other respondents on the three-point agree-disagree question was statistically significant (χ2 = 72.80, df = 2, p < 0.001).Footnote10 Nearly half (44 per cent) of Conservatives disagreed with limiting the role of the Canadian military solely to defending national security interests, but only 25 per cent of those identifying with another party (or not identifying with any party) held this opinion.

Table 1. Militarism beliefs among the Canadian public.

Conservatives appear more interventionist and less willing to put constraints on the use of the military than other Canadians. On the matter of war “sometimes being the only solution” in international affairs, the difference in responses between those who identified with the Conservative Party and others was stark – 57 per cent of Conservatives agreed with the statement while only 28 per cent of others did so, and the difference across the two types of respondents was significant (χ2 = 141.51, df = 2, p < 0.001). Overall, Conservatives were more comfortable with the notion that force is sometimes necessary in an uncertain world, and they were more willing to see Canada use it.

Specific restraints: Afghanistan and Libya

Canada's intervention in Afghanistan dates from its joint military operation with American troops during the early part of the War on Terror and Canada was third only to the United States and United Kingdom when it came to the level of troops supplied to the theater over the course of the conflict (McCulloch Citation2010–2011). In the 2003–2005 period, Canadian troops were involved primarily in nation-building activities, and a clear majority of the Canadian public supported the deployment of forces (Whitaker Citation2003). Fletcher et al. (Citation2009) document the decline in public support that came with the geographical and tactical shift in Canada's mission away from providing assistance with rebuilding local infrastructure and supporting elections in the Kabul region (Operation Athena) to taking (with a force of over 2000 troops) a more active combat role in Kandahar (Operation Archer). Initial political responsibility for the mission shift rested with Paul Martin and his minority government, and the Liberal Party remained supportive of Canada's more aggressive role when Harper and the CPC came to power in 2006. Still, support for the mission among Quebeckers was low and the Bloc Québécois pushed for an end to Canada's combat role in Afghanistan (Chase Citation2006). The NDP added its voice in opposition when NDP Members of Parliament voted against a 2008 House of Commons motion to move the planned exit date for Canadian troops from 2009 to 2011.

On the eve of the May 2011 election, there was a cross-party consensus that Canada's military role in Afghanistan would conclude by the end of the year, which it did when the last rotation of Canadian troops returned from Kandahar in December.Footnote11 During the 2011 election campaign, CCPES respondents were asked about this decision in a question with four options concerning the future role of the Canadian military in the conflict: (1) “pull out of Afghanistan immediately”, (2) “pull out of Afghanistan by the end of 2011, regardless of whether the Taliban is defeated”, (3) “stay in Afghanistan after the end of 2011, but only in a non-combatant role” or (4) “stay in Afghanistan in a combat role as long as it takes to defeat the Taliban”.

As documents, 41 per cent of Conservative identifiers compared to 59 per cent of those identifying with another party (or no party) wanted Canada to exit Afghanistan by the end of 2011. Fully one-third of non-Conservative identifiers wanted the Canadian military to end its role before the stated timescale. In contrast, only 14 per cent of Conservative identifiers felt this way, with the most frequent response among Conservative supporters being that they wanted Canada to stay in the theater in a non-military role. Again, differences between Conservative supporters and other partisans were statistically significant (χ2 = 157.87; df = 4; p < 0.001).

Differences between Conservative identifiers and supporters of other parties also were apparent in an analysis of a survey question concerning Canada's role in the operations over Libya. Shortly before the 2011 election was called, Canada joined a multi-nation North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) group, Operation Mobile, a coalition assembled to enforce a United Nations (UN)-mandated no-fly zone in Libya. In this mission, Canadian warplanes saw their first combat action since the 1999 conflict in Kosovo. In spite of their relatively small size, Canada's forces flew a disproportionate share of the air combat and reconnaissance missions in the theater (Blackwell Citation2011).

Approximately one month after Harper committed Canada's military to Operation Mobile, CCPES respondents were asked if they approved or disapproved of Canada taking on a combat role in the Libyan campaign. Reactions were mixed, with approximately 36 per cent stating that they approved of the mission, 35 per cent saying they disapproved and the rest either unsure or in the middle. As shows, Conservatives were significantly more likely to approve than disapprove (53 per cent vs. 24 per cent) than were those identifying with other political parties or non-identifiers (33 per cent vs. 44 per cent).Footnote12

The 2011 election was unusual in that voters went to the polls when Canadian forces were engaged in combat in two different theaters – Libya and Afghanistan. Commentators were critical of the lack of discussion about the direction and future of the two military missions during the campaign (e.g., Shadwick Citation2011). There was agreement between the Liberals and the Conservatives about the need for Canada to remain in Afghanistan until 2011 and be militarily engaged in Libya. However, those who identified with the Conservative Party again were far more supportive of the combat operations in Libya, and more supportive of a continued Canadian presence in Afghanistan, than were supporters of other parties.

Internationalism: peacekeeping, foreign aid and human rights

Perhaps closer to the comfort zone of many Canadians is the country's outlook on the provision of humanitarian assistance and defending human rights. Many scholars have described Canada's post-war “strategic culture” as dominated – in word if not in deed – by an embrace of “internationalism” which emphasizes multilateralism and participation in intergovernmental institutions to maintain peace and to promote human security (Bloomfield and Nossal Citation2007, p. 299; see also Roussel and Théorêt Citation2004).Footnote13 Through this policy agenda, peacekeeping became engrained in the national consciousness, and, even as the size of its military declined, Canada found its soldiers on the ground trying to maintain peace. In recent years, problems have arisen because overt military missions have been couched in the rhetoric of peacekeeping, or, as Mair (Citation2011) has noted, Canadian military missions have shifted from attempting to keep the peace to attempting to restore peace, often in the middle of violent conflicts (see also Fletcher et al. Citation2009). Perhaps as a consequence of Canada's experience in Afghanistan and in prior missions (in particular, Somalia), the culture may value the ideas behind Canada as a peacemaker, but the public may be skeptical of turning words into deeds. Debates over the effectiveness and direction of overseas aid also persist, and although internationalism appears more firmly rooted in the Canadian psyche than militarism, elite divisions over policy directions are arguably more overt in recent years.

Participation in peacekeeping operations is what Middlemiss and Sokolsky (Citation1989, pp. 173–174) called “one of the longest-standing roles for the Canadian Forces since 1945”. Lester B. Pearson, as both Secretary of State for External Affairs in the 1950s and Prime Minister in the 1960s, made the cause of peacekeeping in the world's hotspots a chief priority of Canadian foreign policy (see Carroll Citation2009). Martin and Fortmann (Citation1995) note that in a series of four polls conducted between 1986 and 1989, Canadians ranked peacekeeping as a top priority for the Canadian Armed Forces, above defending territory. It was only after Canadian peacekeepers were accused of murder and torture in Somalia did support for peacekeeping drop. Still, few respondents in a February 1994 poll wanted Canada to completely withdraw from all peacekeeping operations. In the 2000s, Anker (Citation2005) reported that 81 per cent of Canadians wanted their country's armed forces to participate in peacekeeping missions and over 40 per cent wanted to see the budget for peacekeeping increased.

At the elite level, Canada also places great importance on the need to promote human rights, and that support appears to cross party lines. Brysk (Citation2009, ch. 4) documents Canada's historic role in promoting human rights resolutions and protocols in the halls of the UN and developing the notion of “the responsibility to protect”. She observes that the Harper government, while promoting trade, has been particularly critical of the Chinese government's treatment of dissidents. Others, however, believe that human rights promotion in practice receives short shrift from policymakers. Stephen Brown (Citation2007) notes that the topic was removed from criteria prioritizing the countries to whom Canada granted bilateral aid in the mid-2000s, and Blackwood and Stewart (Citation2012), inter alia, assert that Canadian development assistance is routinely granted to private contractors with poor records for delivering aid.

In polling conducted during the Chrétien era, Canadians appeared to believe that they had a role in furthering the cause of human rights. For example, in a 1995 Environics survey, 94 per cent wanted Canada to “promote human rights in the world”. Similarly, in 2001, a CROP poll showed that 66 per cent believed that “the [Canadian] Government [should] take a hard line against countries that violate human rights, even if that means missing out on some opportunities to expand Canadian trade” (Mendelsohn Citation2002).

Another key pillar of internationalism is development assistance. Overseas aid is seen by some as the expression of Canada's compassionate side, which enables the country to play a role in what retired diplomat Jeremy Kinsman labeled a uniquely Canadian form of “international institution and capacity building” (quoted in Davison Citation2012). It was again former Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson who chaired the UN commission that came up with the proposal to devote 0.7 per cent of a country's gross national income to foreign aid. Much was made of this goal in the 1970s, but Canada's foreign aid budget has never reached the 0.7 per cent level (Clemens and Moss Citation2007). At just over CAD $5 billion annually, it represents approximately 0.34 per cent of the county's Gross National Income (GNI). This is an increase from levels in the Chrétien years, but since the Harper government froze aid spending in 2010, it appears unlikely that Canada will soon meet this international target (Davison Citation2012).

Similar to the issue of promoting human rights, elites frequently extol a vision of providing generous overseas aid. However, the mechanisms and targets of Canadian aid distribution have come under scrutiny and criticism, with many stating that successive federal governments have lacked coherent policies to achieve aid goals (McGill Citation2012). Many on the left decry tying development aid policies to other foreign policy goals such as trade, with this criticism reaching a crescendo when the Harper Government folded the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) into the newly named Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development (DFATD) (Brown Citation2013). For their part, the Conservatives claimed that previous governments distributed Canadian aid inefficiently, and their goal was to improve “aid effectiveness” (McGill Citation2012). In terms of public opinion toward increased overseas aid, in the years following the Chrétien cuts of the 1990s, public support for increasing Canada's foreign aid commitments was high, though still regarded as a low priority (see Nöel et al. Citation2004).

The 2011 CCPES survey reveals large splits in public attitudes towards each of the three pillars of internationalism described above (peacekeeping, the protection of human rights and support for foreign aid). Despite Canada's historic engagement in peacekeeping operations, Canadians were divided over whether their country's commitment in this arena was justified. A surprisingly high 36 per cent agreed with the notion that Canada had overcommitted itself to peacekeeping operations in recent times, with only 31 per cent disagreeing, and 32 per cent reporting ambivalence. This is the one item in the foreign policy question battery where the attitudes of Conservative identifiers and other respondents were reasonably similar. The results displayed in show that Conservatives were, on the whole, slightly more likely than others to disagree with the idea that Canada had overcommitted itself to peacekeeping operations (37 per cent vs. 31 per cent, χ2 = 7.44; df = 2; p < 0.03). One reason support for involvement in peacekeeping may be lower now than in times past is that the Canadian experience in Afghanistan featured both peacekeeping and combat activities (Fletcher et al. Citation2009). It is an interesting and open question as to whether those who viewed Canada's role in Afghanistan as combat oriented have as a consequence become more skeptical of the country's future involvement in peacekeeping operations.

Table 2. Internationalism beliefs among the Canadian public.

Shortly after the 2011 election, a clear plurality of CCPES respondents believed the country was overspending on overseas aid, with 42 per cent agreeing and only 28 per cent disagreeing with the statement that “Canada should spend less money on foreign aid to developing countries”. Data displayed in demonstrate that Conservative identifiers were more suspicious of the amount of money Canada was spending – a majority of Conservatives (51 per cent) wanted cuts in aid spending, and they were significantly more likely than supporters of other parties to advocate reducing Canada's commitments in this area (χ2 = 33.19; df = 2; p < 0.001).

A clear plurality of the CCPES respondents wanted Canada to be more actively engaged in protecting human rights. Specifically, 44 per cent agreed and only 17 per cent disagreed with the statement that “Canada should take a more active role in protecting human rights around the world”. However, ambivalence was substantial, with 37 per cent reporting that they neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement or did not know how to answer the question. Conservative identifiers were significantly less likely than others (37 per cent vs. 50 per cent) to agree with this statement. It is interesting that this question elicited less support than similar questions asked about human rights in surveys conducted in the 1990s and 2000s, suggesting that possibly Canadians have become less favorable towards taking an active role to promote human rights in recent years.

Overall, Conservative supporters appear more skeptical than others when it comes to Canada deploying instruments of soft power such as spending money on overseas aid and being vocal about the need to protect human rights. However, when it comes to deploying the military to further the ends of peace, Conservatives appeared more eager than other Canadians at the time of the 2011 federal election. As shown below, this may be because peacekeeping is seen as a reflection of both militarism and internationalism. Conservative supporters are more favorable towards the former and more skeptical of the latter.Footnote14

Support for Prime Minister Harper and the Conservative Party

To assess the effects of foreign policy attitudes and several other factors on evaluations of Harper and the Conservative Party, we performed ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses.Footnote15 Our dependent variable was a composite of three 0 to 10 “feeling thermometer” scales: those from the campaign period and post-election survey asking about Harper, and the post-election survey item asking about the Conservative Party.Footnote16 To gauge the relative contribution of domestic and international political considerations in shaping attitudes toward the Harper government and avoid overstating the importance of foreign policy attitudes, variables measuring both sets of attitudes were included in the model.

To capture domestic policy attitudes and themes pertinent to the 2011 federal election, three composite scales were used.Footnote17 Each demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability. The first scale concerns views of the state of Canadian democracy. It is important to recall that concern over the state of Canadian democracy – and its purported abuse by the previous minority Conservative government – was a salient theme in the 2011 federal election. Harper's prorogation of the House of Commons in December 2008 and again in December 2009, as well as the March 2010 finding of the Conservative Government in contempt of Parliament (for refusing to release a raft of costing documents), all factored into a feeling among parts of the Canadian electorate that the Harper government was abusing Canadian democracy (Dornan Citation2011). Other considerations aside, these sentiments influenced voting in the 2011 election (Clarke et al. Citation2011). Our “concern with democracy” scale is based on responses to the following three statements (where possible responses range from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”): “allegations about the Conservative Government's contempt of Parliament are a political smear”, “Harper acted properly when he asked Governor General to prorogue the House of Commons” and “Harper has run rough-shod over Canada's democratic political traditions”.

A second scale measures attitudes toward the economy and comprises items measuring how the economy is doing these days (on a continuum from “very well” to “very bad”), change in the economic situation in the past 12 months (on a scale from “got a lot better” to “got a lot worse”) and expectations about how the economic situation will develop over the next 12 months (on a scale from “get a lot better” to “get a lot worse”). Finally, attitudes about social spending were measured using four items: agreement with the statement that “Canada can't afford to spend more money on health care system”, scores on a 0 to 10 semantic differential scale ranging from “government should increase taxes a lot and spend much more” to “government should cut taxes a lot and spend much less”, and agreement with the statements “the federal government should do more to equalize standard of living” and “more money should be transferred from richer parts of Canada to poorer parts.”

To delineate foreign policy beliefs, scales measuring the previously described constructs of militarism and internationalism were used. Both scales exhibited acceptable levels of statistical reliability. Militarism was measured using five variables: the item about commitment to the mission in Afghanistan (with responses ranging from “stay in Afghanistan in a combat role as long as it takes” to “pull out of Afghanistan immediately”), an item measuring approval of Canada's involvement in combat role in Libya (on a scale from “strongly approve” to “strongly disapprove”) and agreement with the statements “sometimes, going to war is only solution to international problems”, “Canada should not employ armed forces unless country's security is directly threatened” and “in recent years Canada has participated in too many international peacekeeping operations”. Internationalism was measured as agreement with the statements “in recent years Canada has participated in too many international peacekeeping operations”, “Canada should spend less money on foreign aid to developing countries” (reverse coded), and “Canada should take a more active role in protecting human rights around the world”.Footnote18 As before, all items were scaled between 0 and 1 before being averaged to produce the composite militarism and internationalism scores.

We initially estimate the effects of domestic policy variables while excluding foreign policy variables (Model 1). Next, we estimate the effects of foreign policy variables while excluding those concerning domestic policy (Model 2). We then include both domestic and foreign policy variables in the analysis (Model 3). Finally, we examine interactions between Conservative party identification and both militarism and internationalism (Model 4). This latter analysis tests the hypotheses that the effects of militarism and internationalism beliefs on feelings toward the Harper Government and the Conservative Party differ between Conservative identifiers and non-identifiers. Conservative party identification, socio-demographic variables (age, sex and education) and province of residence are included in all four models.

The analyses yield several interesting findings (see ). As expected, identification with the Conservative Party is positively associated with feelings toward the Harper Government/Conservatives in all models. Also, all domestic policy attitudes have highly significant effects in theoretically expected directions. Concern with Canadian democracy exerts a strong negative effect on feelings toward the Harper government and the Conservatives. Robust but more modest effects are also evident for evaluations of the economy (positive effect) and preferences for greater social spending (negative effect).

Table 3. Multivariate analyses of Canadians’ feelings about Prime Minister Harper and the Conservative Party of Canada (OLS regression models).

Regarding beliefs about foreign policy, a number of findings are noteworthy. First, the covariation of militarism and internationalism with feelings toward the Harper government/Conservatives prior to controlling for domestic policy attitudes (Model 2) is quite strong. Controlling for socio-demographics, region of residence and party identification, increasing militarism attitudes from their minimum to their maximum value raises feelings about Harper and the Conservatives by 3.67 points (on the 0 to 10 scale). Similarly, increasing internationalism attitudes from their minimum to their maximum value lowers feelings about the prime minister and his party by 2.64 points. The covariation of both militarism and internationalism with party and leader affect remain significant once domestic policy attitudes are introduced (Model 3), but they are reduced in magnitude to 1.65 and –1.17 points, respectively. Still, both domestic and foreign policy attitudes are powerful: the model including both sets of policy attitudes improves the power of the model compared to models that include only domestic policy attitudes (F (2, 2780) = 31.03; p < 0.001) or only foreign policy attitudes (F (3, 2780) = 470.50; p < 0.001). Furthermore, the effects of militarism and internationalism attitudes are approximately equal to those for evaluations of the economy and preferences for social spending – variables traditionally considered important in models of party support and voting behavior (e.g., Clarke et al. Citation2009; Gidengil et al., Citation2012). These results testify that foreign policy attitudes are consequential for assessments of Harper and his party. The bivariate analyses presented in and asked whether foreign policy attitudes were correlates of identification with the Prime Minister's Conservative Party. The multivariate estimation presented in Model 3 asks whether foreign policy attitudes are correlates of individual affect towards the Conservative Party and its leader even after a voter's propensity to have a longstanding bond with the CPC is considered. The answer to both questions is a strong “yes”.

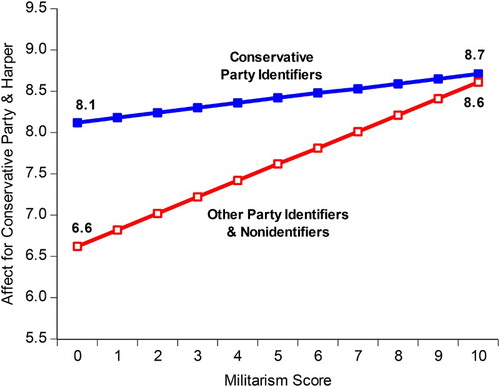

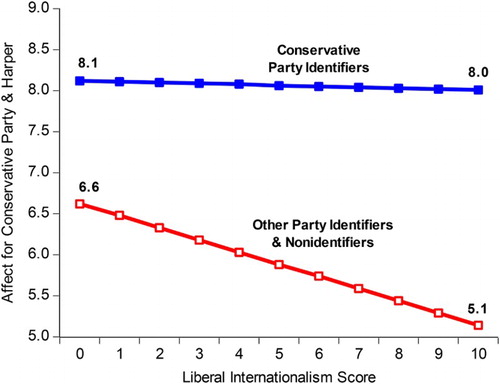

However, it may be the case that the effects of foreign policy attitudes on feelings about Harper and the Conservative Party differ between Conservative partisans and other segments of the Canadian public. Put another way, Conservative Party identification may moderate the effects of militarism and internationalism (e.g., Jaccard and Turrisi Citation2003). We examine this possibility and find that there are significant interaction effects between Conservative Party identification and militarism attitudes, as well as between Conservative Party identification and internationalism attitudes. Both interactions contribute additional explanatory power to the model (F (2, 2778) = 6.08; p < 0.01). The effects of militarism and internationalism are heterogeneous in the electorate. To explicate the substantive meaning of this finding, graphical displays of these interactions are helpful (Fox Citation1987). The graphical depiction of the relationship between militarism and feelings toward the Harper government in makes clear that the effect of militarism on feelings about Harper and his party generally is much more pronounced among non-Conservative identifiers. However, among those scoring high on militarism, evaluations of the Harper government differ only negligibly between Conservative Party identifiers and non-identifiers. Militarism attitudes thus work to close the partisan gap in evaluations of the Harper government.Footnote19 In contrast, internationalist beliefs widen this gap. Scoring high on internationalism works to lower feelings about the prime minister and his party, but only among non-Conservative identifiers (see ). Among persons who identify with the Conservative Party, the correlation of internationalism attitudes with party and leader affect is effectively zero.

Conclusion: foreign policy beliefs and political support in Canada

Do foreign policy beliefs matter for Canadian electoral politics? Since the first election studies were conducted in the 1960s, research on support for Canadian political parties and their leaders has typically emphasized domestic political considerations, with attitudes towards issues such as management of the economy and policy delivery in important areas such as health care featuring prominently in accounts of why Canadians vote the way they do. The present paper departs from this tradition by focusing on the nature of foreign policy beliefs and their covariation with feelings about Prime Minister Harper and the Conservative Party.

Congruent with research conducted in the United States and other countries, analyses of national survey data gathered at the time of the 2011 federal election show that Canadians' foreign policy beliefs can be structured along two dimensions – internationalism and militarism. The internationalism dimension has been familiar to students of Canadian foreign policy since the Pearson era, and it involves topics such as Canada's longstanding leadership role as an international peacekeeper, protection of at-risk populations around the globe from human rights abuses and the generous provision of overseas aid. In contrast, the militarism dimension involves beliefs about the necessity of war and the conditions in which Canada is justified in engaging in military conflicts. More specific, context-relevant militarism beliefs studied with the survey data concern the desirability of Canadian forces engaging in combat roles in Afghanistan and Libya.

Analyses reveal that Conservative party identifiers differ from identifiers with other federal parties (and those who do not identify with any federal party) on a majority of the specific topics organized by the militarism and internationalism dimensions. As expected, Conservative partisans are more apt to endorse the idea that there are occasions when military force is required and to support the use of military force in theaters such as Afghanistan and Libya. As also anticipated, Conservative supporters are less enthusiastic than other Canadians about the country's roles in peacekeeping missions and as guardians of human rights and less prone to favor providing overseas aid to developing countries.

These internationalism and militarism attitudes are consequential. Controlling for a variety of the “usual suspects” in models of Canadian voting behavior such as party identification, economic evaluations, attitudes towards social spending, socio-demographics and province of residence, multivariate analyses demonstrate that internationalism and militarism attitudes are strong correlates of support for Harper and the CPC. Persons who score high on the militarism dimension and low on the internationalism dimension are more likely to favor Harper and his party, whereas those with low militarism scores and high internationalism scores are more likely to accord low ratings to Harper and the CPC. Further analyses reveal that internationalism and militarism attitudes interact with partisanship, with their effects being concentrated among people who do not identify with the Conservative Party.

Viewed generally, contrary to suggestions of an “absent mandate” in the realm of foreign policy, our findings suggest that Harper has a basis of public support for a more militaristic and less internationalist foreign policy agenda. Being willing to contemplate the use of military force enhances the popularity of Harper and his party among that subgroup of Canadian voters who hold such views. By the same token, the size of the group not identifying with the federal Conservative Party – 60 per cent at the time of the 2011 federal election – suggests that foreign policy beliefs can have broad relevance for understanding attitudes towards Canadian political parties and their leaders. The typically low salience of foreign policy issues in federal elections does not mean that foreign policy beliefs and the underlying values that animate them are irrelevant for understanding the political choices Canadians make.

Notes

1. See Wittkopf (Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation1994) for a discussion of how these dimensions form in the minds of the American public. For public opinion studies employing the dimensions outside of the United States, see, e.g., Reifler et al. (Citation2011) for the United Kingdom and Desposato et al. (Citation2013) for Brazil and China.

2. For example, Bow (Citation2008) notes that Joe Clark's Progressive Conservative Government was hurt by a controversy over the location of Canada's embassy in Israel, and Prime Minister Paul Martin appeared indecisive on the issue of missile defence in the 2006 campaign.

3. The 2004 federal election featured a debate over the appropriateness of a military build-up and the discussion over Harper's advocacy of sending Canadian troops to Iraq. The 2006 campaign featured a minor debate over the status of a “territorial army” (see Shadwick Citation2011).

4. The survey respondents' declarations of what issue(s) are most important are often taken as a proxy for salience. But there are critiques of this approach – see Johns (Citation2010).

5. See Martin and Fortmann (Citation1995), Munton (Citation2002–2003) and Rioux and Hay (Citation1998–1999). An important exception is Munton and Keating (Citation2001), who performed an exploratory factor analysis of responses to a series of survey questions and found multiple dimensions of Canadian internationalism. This paper is, perhaps, a testament to the rarity of comprehensive batteries of foreign policy questions on Canadian surveys as their analysis had to rely on a survey fielded in 1985.

6. The survey was conducted by YouGov, Plc. YouGov's matching algorithm is designed to create a web-based sample whose characteristics approximate a probability sample, thus permitting model-based inferences (Rivers Citation2006). An initial sample of 3511 Canadian adults with proportionate representation from all provinces and territories completed an online screening survey. These respondents were matched on demographic factors (gender, age, education and region) to produce the final pre-election sample of 2800 respondents. The survey data were then weighted to the known population marginals for the Canadian adult population. Non-probability samples have been debated in the survey methodology literature. Some research focusing on the American context found differences in the estimates obtained from probability and non-probability survey samples (e.g., Malhotra and Krosnick Citation2006). However, other research concludes that there are very few differences between inferences made from high-quality online survey data gathered via “active” sampling methods such as those employed in our survey and those gathered by other survey modes (i.e., in-person, telephone or mail-back questionnaires) (see Ansolabehere and Schaffner, Citation2014). Similarly, analyses in Canada (Stephenson and Crête Citation2010) and Great Britain (Sanders et al. Citation2007, Clarke et al. Citation2008) have found that differences between probability and online data are very small, and substantive conclusions about relationships between variables of theoretical interest are identical across modes. For a recent review, see Baker et al. (Citation2013). Support for CCPES was provided via a grant to Jason Reifler from the National Science Foundation (SES #1003254), and to Thomas J. Scotto from the Canadian High Commission, London and by grant RES-061-25-0405 from the Economic and Social Research Council of the United Kingdom.

7. The idea is that the decision of France to commit to action abroad plays a distinct role in Canadian foreign policy because such actions signal to Quebeckers that Canada's involvement is justifiable.

8. Support for intervention in Quebec, where support for the Conservatives was weak in 2011, is historically low, a stance some scholars have viewed as a likely reaction to a military and political establishment that is largely English speaking and has a historically British lineage (e.g., Granatstein Citation2004).

9. The bulk of troops were stationed in Afghanistan. In many locations, Canada's commitment involved less than one dozen troops (e.g., the lone troop the nation has as part of the United Nations peacekeeping force in Cyprus). However, the number of missions the Canadian military is partner to might surprise many citizens and, given the results of this study, would likely engender opposition.

10. Possible responses to both questions included: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree and don't know. For ease of presentation in the cross-tabulations, the two agree and two disagree categories were combined. Responses in the “don't know” and “neither agree nor disagree” categories also were pooled. The conclusions drawn from the cross-tabulations when the full six-point scales were analyzed are not substantively different from those drawn when the collapsed scale is analyzed. The multivariate analyses below use a full five-point scale, with “don't know” responses treated as missing at random and multiply imputed. The substantive interpretations that stem from the results are not sensitive to coding decisions.

11. Combat missions involving Canadian troops formally ended in July 2011 (see Government of Canada Citation2013).

12. In contrast to the division at the public level, elite support for the Libyan mission was quite high with even the Bloc Québécois supporting the government, perhaps noting the leadership France was taking in the operation. Before the dissolution of Parliament, Prime Minister Harper did not seek approval from Parliament. After the election, approval was granted via a 294–1 vote, with the lone Green Party MP, Elizabeth May, dissenting. NDP opposition grew over the summer (Nossal Citation2013). The difference in the distribution of responses provided by Conservative identifiers and other respondents was significant χ2 = 98.31 (df = 2; p < 0.001).

13. The human security agenda was a particular focus of Lloyd Axworthy during his tenure as the Minister for Foreign Affairs for Jean Chrétien in the late 1990s (see Hillmer and Chapnick Citation2001, Bloomfield and Nossal Citation2007).

14. In contrast to previous surveys where the peacekeeping question was “Canada should participate in peacekeeping operations abroad even if it means putting the lives of Canadian soldiers at risk”, we designed the 2011 CCPES question to deemphasize the military aspect of peacekeeping operations. Still, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) suggested that Canadian attitudes towards peacekeeping are manifestations of both beliefs about the use of the military and internationalism. As discussed above, the Canadian mission in Afghanistan evolved to the point where heavy combat operations by the armed forces were the norm, and previous Canadian peacekeeping missions have not been without casualties. Canadians appear to understand that peacekeeping operations require heavily armed soldiers and are not naïve enough to think that such missions are without danger to the lives of soldiers and others on the ground. As shown in , levels of approval, however, vary considerably.

15. To preserve cases that would otherwise be lost due to item non-response (providing a “don't know” response or refusal to an individual survey item) or survey non-response (i.e., completing the campaign-period survey but not the post-election survey), we impute missing data (Rubin Citation1987, Allison Citation2001, Little and Rubin Citation2002). Multiple imputation was carried out using IVEware version 0.1 for SAS (Raghunathan et al. Citation2002). Ten multiply imputed datasets were created, the inferences from which were combined using SAS PROC MIANALYZE to produce inferences that account for sampling variation and the uncertainty associated with the imputation process.

16. This composite scale was highly reliable (coefficient α = 0.96).

17. All items were scaled between 0 and 1 before being averaged to produce the composite scores.

18. As noted above, since EFA demonstrated that the peacekeeping item contributed to both the militarism and internationalism factors (i.e., it cross-loaded), it is included in both composite scales. Further, the EFA indicated that attitudes toward Canada-United States relations (closer or looser ties) and agreement with the statement that “Canada should only use its armed forces abroad when it gets approval from the United Nations” did not load on either the militarism or internationalism factor. We had no theoretical expectations regarding the effects of these two variables on attitudes toward the Harper government, and as neither had statistically significant effects, they were excluded from the analyses.

19. Additional analyses of the interaction effect between Conservative party identification and militarism indicate that there is no significant difference between Conservative identifiers and non-identifiers when militarism is above 0.6 (roughly the 75th percentile). In this regard, one should be mindful of potential “ceiling effects” among Conservative identifiers, whose ratings of the Harper government tend to cluster near the top of the 0 to 10 scale (mean = 7.49, median = 7.71).

References

- Allison, P.D., 2001. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Almond, G.A., 1950. The American people and foreign policy. 1st ed. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Anker, L., 2005. Peacekeeping and public opinion. Canadian Military Journal 6 (2) Available from: http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo6/no2/public-eng.asp [Accessed 27 February 2014].

- Ansolabehere, S. and Schaffner, B.F., 2014. Does survey mode still matter? Evidence from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Analysis, 22 (3), 285–303.

- Baker, R., et al., 2013. Summary report of the AAPOR task force on non-probability sampling. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 1 (2), 90–105. doi: 10.1093/jssam/smt008

- Barry, D. and Bratt, D., 2008. Defense against help: explaining Canada-US security relations. American Review of Canadian Studies, 38 (1), 63–89. doi: 10.1080/02722010809481821

- Berdahl, L. and Raney, T., 2010. Being Canadian in the world: mapping the contours of national identity and public opinion on international issues in Canada. International Journal, 65 (Autumn), 995–1010. doi: 10.1177/002070201006500424

- Bjereld, U., and Ekengren, A.-M., 1999. Foreign policy dimensions: a comparison between the United States and Sweden. International Studies Quarterly, 43 (3), 503–518. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00132

- Blackwell, T., 2011. Canada contributed a disproportionate amount to Libya airstrikes: source [online]. National Post, 25 August. Available from: http://news.nationalpost.com/2011/08/25/canada-contributed-a-disproportionate-amount-to-libya-air-strikes-sources/ [Accessed 28 August 2013].

- Blackwood, E., and Stewart, V., 2012. CIDA and the mining sector: extractive industries as an overseas development strategy. In: S. Brown, ed. Struggling for effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian foreign aid. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 24–52.

- Bloomfield, A., and Nossal, K.R., 2007. Towards an explicative understanding of strategic culture: the cases of Australia and Canada. Contemporary Security Policy, 28 (2), 286–307. doi: 10.1080/13523260701489859

- Bow, B., 2008. Parties and partisanship in Canadian defense policy. International Journal, 64 (1), 67–88.

- Bow, B. and Black, D., 2008. Does politics stop at the water's edge in Canada? Party and partisanship in Canadian foreign policy. International Journal, 64 (1), 7–27.

- Brown, S., 2007. Creating the world's best development agency? Confusion and contradiction in CIDA's new policy blueprint. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 28 (2), 213–228.

- Brown, S., 2013. Canada's foreign aid before and after CIDA: not a Samaritan state. International Journal, 68 (3), 501–512. doi: 10.1177/0020702013505730

- Brysk, A., 2009. Global good Samaritans: human rights as foreign policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, A., et al., 1960. The American voter. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Carroll, M.K., 2009. Pearson’s peacekeepers: Canada and the United Nations Emergency Force: 1956–1967. Vancouver: The University of British Columbia Press.

- Chase, S., 2006. Bloc wants urgent debate on foreign file. Globe and Mail, 5 September, A9.

- Chittick, W.O., Billingsley, K.R. and Travis, R., 1995. A 3-dimensional model of American foreign-policy beliefs. International Studies Quarterly, 39 (3), 313–331. doi: 10.2307/2600923

- Clarke, H.D., Kornberg, A. and Scotto, T.J., 2009. Making political choices: Canada and the United States. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Clarke, H.D., et al., eds. 2008. Internet surveys and national election studies. Special Issue of the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 18 (4).

- Clarke, H.D., et al., 2011. Winners and losers: voters in the 2011 federal election. In: J.H. Pammett and C. Dornan, eds. The Canadian federal election of 2011. Toronto: Dundurn, 271–301.

- Clemens, M.A. and Moss, T.J., 2007. The ghost of 0.7 per cent: origins and relevance of the international aid target. International Journal of Development Issues, 6 (1), 3–25. doi: 10.1108/14468950710830527

- Converse, P.E., 1964. The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In: D.E. Apter, ed. Ideology and Discontent. New York: Free Press, 206–261.

- Davison, J., 2012. Does cutting foreign aid threaten Canada's reputation in the world? [online]. CBC News Online, 3 April. Available from: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/does-cutting-foreign-aid-threaten-canada-s-reputation-in-the-world-1.1185278. [Accessed 1 October 2013].

- Desposato, S., Gartzke, E. and Suong, C., 2013. How popular is the democratic peace? Typescript. University of California, San Diego.

- Dornan, C., 2011. From contempt of Parliament to majority mandate. In: J.H. Pammett and C. Dornan. The Canadian federal election of 2011. Toronto: Dundurn, 7–13.

- Fletcher, J.F., Bastedo, H. and Hove, J., 2009. Losing heart: declining support and the political marketing of the Afghanistan mission. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 42 (4), 911–937. doi: 10.1017/S0008423909990667

- Fournier, P., et al., 2003. Issue importance and performance voting. Political Behavior, 25 (1), 51–67. doi: 10.1023/A:1022952311518

- Fox, J., 1987. Effect displays for generalized linear models. Sociological Methodology, 17, 347–361. doi: 10.2307/271037

- Gidengil, E., et al., 2012. Dominance & decline: making sense of recent Canadian elections. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Government of Canada, 2013. History of Canada's engagement in Afghanistan, 2001–2012 [online]. Modified 10 July. Available from: http://www.afghanistan.gc.ca/canada-afghanistan/progress-progres/timeline-chrono.aspx?lang=eng [Accessed 27 August 2013].

- Granatstein, J.L., 2004. Who killed the Canadian military? 1st ed. Toronto: Harper Canada.

- Haglund, D.G., 1999. The North Atlantic triangle revisited: (geo)political metaphor and the logic of Canadian foreign policy. American Review of Canadian Studies, 29 (2), 211–235. doi: 10.1080/02722019909481629

- Haglund, D.G., 2004. What good is strategic culture – a modest defence of an immodest concept. International Journal, 59 (3), 479–502. doi: 10.2307/40203951

- Hillmer, N. and Chapnick, A., 2001. The Axworthy revolution. In: F.O. Hampson, N. Hillmer and M.A. Molot, eds. Canada Among Nations 2001: The Axworthy Legacy. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 67–88.

- Hogg, W., 2004. Plus ça change: continuity, change and culture in foreign policy white papers. International Journal, 59 (3), 521–536. doi: 10.2307/40203953

- Holsti, O.R., 1992. Public opinion and foreign policy: challenges to the Almond-Lippmann consensus. International Studies Quarterly, 36 (4), 439–466. doi: 10.2307/2600734

- Hurwitz, J., Peffley, M. and Seligson, M.A., 1993. Foreign policy belief systems in comparative perspective: the United States and Costa Rica. International Studies Quarterly, 37 (3), 245–270. doi: 10.2307/2600808

- Jaccard, J. and Turrisi, R., 2003. Interaction effects in multiple regression. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Johns, R., 2010. Measuring issue salience in British elections: competing interpretations of “most important issue”. Political Research Quarterly, 63 (1), 143–158. doi: 10.1177/1065912908325254

- Kagan, R., 2003. Power and paradise: America and Europe in the new world order. New York: Alfred Knopf.

- Lippmann, W., 1922. Public opinion. New York: Harcourt.

- Little, R.J.A. and Rubin, D.B., 2002. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley.

- Mair, R., 2011. Canada – peacekeeper to combatant [online]. Strategic Culture Foundation Online Journal, 30 March. Available from: http://www.strategic-culture.org/news/2011/03/30/canada-peacekeeper-to-combatant.html [Accessed 27 February 2014].

- Malhotra, N. and Krosnick, J.A., 2006. The effect of survey mode and sampling on inferences about political attitudes and behavior: comparing the 2000 and 2004 ANES to internet surveys with nonprobability samples. Political Analysis, 15 (3), 286–323. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpm003

- Martin, D., 2008. Election the real battlefront of Harper's military plan [online]. National Post, 12 May. Available from: http://forums.milnet.ca/forums/index.php?topic=76329.55;wap2 [Accessed 30 September 2013].

- Martin, P. and Fortmann, M., 1995. Canadian public opinion and peacekeeping in a turbulent world. International Journal, 50 (2), 370–400.

- Massie, J., 2008/2009. North Atlantic quadrangle: Mackenzie King's lasting imprint on Canada's international security policy. London Journal of Canadian Studies, 24 (5), 85–105.

- Massie, J., 2009. Making sense of Canada's “irrational” international security policy: a tale of three strategic cultures. International Journal, 64 (3), 625–645. doi: 10.1177/002070200906400303

- McCulloch, T., 2010–2011. The North Atlantic Triangle: a Canadian Myth. International Journal, 66 (1), 197–207. doi: 10.1177/002070201106600113

- McDonough, D.S., 2012. Canada, grand strategy and the Asia-Pacific: past lessons, future directions. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 18 (3), 273–286. doi: 10.1080/11926422.2012.737340

- McGill, H., 2012. Canada among donors: how does Canadian aid compare? In: S. Brown, ed. Struggling for effectiveness: CIDA and Canadian foreign aid. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 24–52.

- Mendelsohn, M., 2002. Canada's social contract: evidence from public opinion [online]. Public Involvement Network Discussion Paper 1. Available from: www.cprn.org/documents/15075_en.PDF [Accessed 5 October 2013].

- Middlemiss, D.W. and Sokolsky, J.J., 1989. Canadian defence: decisions and determinants. Toronto: Harcourt Brace.

- Munton, D., 2002–2003. Whither internationalism? International Journal, 58 (1), 155–180. doi: 10.2307/40203817

- Munton, D. and Keating, T., 2001. Internationalism and the Canadian public. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 34 (3), 517–549. doi: 10.1017/S0008423901777992

- Noël, A., Thérien, J.-P. and Dallaire, S., 2004. Divided over internationalism: the Canadian public and development assistance. Canadian Public Policy, 30 (1), 29–46. doi: 10.2307/3552579

- Nossal, K.R., 2013. The use – and misuse – of R2P: the case of Canada. In: A. Hehir and R. Murray, eds. Libya, the responsibility to protect and the future of humanitarian intervention. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 110–129.

- Ørvik, N., 1973. Defence against help – a strategy for small states? Survival, 15 (5), 228–231. doi: 10.1080/00396337308441422

- Page, B.I. and Bouton, M.M., 2006. The foreign policy disconnect: what Americans want from our leaders but don't get. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rabinowitz, G., Prothro, J.W. and Jacoby, W., 1982. Salience as a factor in the impact of issues on candidate evaluation. Journal of Politics, 44 (1), 41–64. doi: 10.2307/2130283

- Raghunathan, T.E., Solenberger, P.W. and Van Hoewyk, J., 2002. IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software user guide. Survey Methodology Program, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- Reifler, J., Scotto, T.J. and Clarke, H.D., 2011. Foreign policy beliefs in contemporary Britain: structure and relevance. International Studies Quarterly, 55 (1), 245–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00643.x

- Rioux, J.F. and Hay, R., 1998–1999. Canadian foreign policy: from internationalism to isolationism. International Journal, 54 (1), 57–75. doi: 10.2307/40203355

- Rivers, D., 2006. Sample matching: representative sampling from internet panels. Polimetrix, 1–8.

- Roussel, S. and Théorêt, C.-A., 2003. A “distinct strategy”? The use of Canadian strategic culture by the sovereigntist movement in Québec, 1968–1996. International Journal, 59 (3), 557–577. doi: 10.2307/40203955

- Rubin, D.B., 1987. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

- Sanders, D., et al., 2007. Does mode matter for political choice? Evidence from the 2005 British election study. Political Analysis, 15 (3), 257–285. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpl010

- Shadwick, M., 2011. Commentary: defense and the 2011 election [online]. Canadian Military Journal, 11(4). Available from: http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo11/no4/64-ayer-eng.asp [Accessed 28 August 2013].

- Soroka, S.N., 2003. Media, public opinion, and foreign policy. International Journal of Press/Politics, 8 (1), 27–48. doi: 10.1177/1081180X02238783

- Stephenson, L.B. and Crête, J., 2010. Studying political behavior: a comparison of internet and telephone surveys. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 23 (1), 24–55. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edq025

- Whitaker, R., 2003. Keeping up with the neighbours: Canadian responses to 9/11 in historical and comparative perspective. Osgoode Hill Law Journal, 41, 241–265.

- Wittkopf, E.R., 1986. On the foreign-policy beliefs of the American-people – a critique and some evidence. International Studies Quarterly, 30 (4), 425–445. doi: 10.2307/2600643

- Wittkopf, E.R., 1990. Faces of internationalism: public opinion and American foreign policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Wittkopf, E.R., 1994. Faces of internationalism in a transitional environment. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 38 (3), 376–401. doi: 10.1177/0022002794038003002

- Wlezien, C., 2005. On the salience of political issues: the problem with most important problem. Electoral Studies, 24 (4), 555–579. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.01.009