Abstract

Although widely ignored by political scientists and scholars of international relations alike, historically unprecedented demographic change is arguably the most powerful force to affect national security and international stability over the coming decades. Fertility, mortality and migration are the one set of variables in the social sciences that can be projected into the more distant future with a reasonable degree of accuracy. As a result, the structural constraints and possibilities of demographic trends provide traction in anticipating future developments. This article examines the evolution of Canada - United States defence and security relations. It turns out that demographic trends among allied countries are bolstering Canada's value as a U.S. ally in both a bilateral and a multilateral context. In fact, demographic trends imply that Ottawa will be able to expand ability to punch above its weight in Washington, thus making Canada and the United States even more co-dependent in asserting their defence and security interests.

Bien que largement ignoré par les politicologues et les spécialistes des relations internationales, le changement démographique sans précédent historique auquel nous assistons est sans aucun doute la force la plus puissante qui affectera la sécurité nationale et la stabilité internationale dans les prochaines décennies. La fertilité, la mortalité et la migration sont, dans le domaine des sciences sociales, l'ensemble des variables qui peuvent être projetées dans un futur plus distant avec un degré de précision raisonnable. Ainsi, les contraintes et les possibilités structurelles des tendances démographiques suscitent-elles de l'intérêt pour l'anticipation des futurs développements.

Cet article examine l’évolution des relations de défense et de sécurité entre le Canada et les États-Unis. Il s'avère que les tendances démographiques dans les pays alliés renforcent la valeur du Canada en tant qu'allié des États-Unis, aussi bien dans le contexte bilatéral que dans le contexte multilatéral. En fait, ces tendances impliquent qu'Ottawa sera capable de renforcer ses capacités jusqu’à pouvoir peser de tout son poids face à Washington, rendant ainsi le Canada et les États-Unis encore plus dépendants l'un de l'autre, en affirmant leurs intérêts en matière de défense et de sécurité.

Rarely can social scientists claim to be observing genuinely unprecedented phenomena. Hitherto, high birth rates had ensured predominantly young populations with few older people. War and epidemics, such as the plague, would intervene to depress population growth (Anderson Citation1996, Livi-Bacci Citation2007). By contrast, depressed population growth today is a function of a historically unprecedented decline in birth rates. That is, women are consistently having fewer (or no) children than at any previous time in history. Demography in all its facets – fertility, net migration (immigrants – emigrants), mortality, population size, age structure, the first and second demographic transitions – is a vital ingredient in shaping the political process. Its effect can be proximate or remote; first, second or third order; necessary, but rarely sufficient; it can serve as a precipitant or a conditioning factor (Horowitz Citation1985, pp. 258–259, Fischer and Hout Citation2006). As this article shows, it is an important determinant in – albeit not deterministic of – bi- and multilateral defence relations. Relative population aging is having a differentiating effect on the sustainability of allied defence resources and capabilities: owing to similar demographic trends, Anglo-Saxon allies – not only the United States but to a lesser extent Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia – are becoming relatively more important allies, while demographic fundamentals are already having deleterious consequences for some continental European allies. Demography is not destiny. Demographic developments can, however, be projected into the future with a high degree of reliability. These demographic developments bode well for Canada as an American partner in international security and defence, as, structurally, they are giving rise to an even greater degree of mutual co-dependence. The benefits of this shift are bound to accrue disproportionately to Canada: as Canada becomes an even more indispensable ally, its leverage over the bilateral defence and international security relationship is likely to grow.

The first section of this article operationalizes the concept of political demography, defends its significance for the study of foreign relations and national interest, and surveys key demographic trends. The following section explores the implications of these trends on fiscal capacity and expenditure pressures. The third section discusses consequences of these trends within a North American perspective.

Political demography

Just as no credible political scientist can afford to ignore the role of economic incentives, institutions, or culture, [ … ] political scientists cannot afford to ignore demography in seeking to understand patterns of political identities, conflict, and change. (Kaufmann and Duffy Toft Citation2012, p. 3)

The next four decades will present unprecedented changes in long-term demographic trends, including the shrinkage of Europe's labor force, the extreme aging of the advanced industrial societies, a global shift from mainly rural to mainly urban habitation, and a substantial turn in global economic growth toward the developing world (where nine out of every 10 of the world's children under 15 now live).

Population aging will beset much of the world at some point this century. The scope of this aging process is remarkable. By 2050, at least 20 per cent of the population in allied countries, but also in China and Russia, will be over 65. In Japan it will be as high as one-third of the population. Population aging, as shows, is accompanied by a diffusion of absolute population decline. Russia's population, for instance, has been contracting by 500,000–700,000 people per year. Unprecedented population aging in East Asia and Europe will see many developed countries' over-60 populations approach 40 per cent of the national total by 2050. This demographic development is historically without precedent; we do not know what to expect from a state with over one-third of its population over 60, nor how its economic growth and finances will be affected (Friedman Citation2005, Bloom et al. Citation2011). Most of the world's affluent countries – in Europe, East Asia (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore) and North America – have completed their demographic transition and have stable or very slow-growing populations. Several of them, including Germany and many in Eastern Europe, have seen their total fertility rate fall well below 2.0 children per woman, so that they are forecast to decline in population in the near future, save for considerable in-migration.

Table 1. Countries projected to have declining populations, by the period of the onset of decline, 1981–2045.

Never before has humanity witnessed such dramatic, widespread aging among the world's most industrialized and powerful military allies. Two long-term demographic trends have coincided to produce population aging: decreasing fertility rates and increasing life expectancy. Fertility rate refer to the average number of children born per woman. For a state to sustain its population (assuming zero net immigration), fertility levels must exceed about 2.1 children per woman. Today the United States is the only liberal democracy that comes close to meeting this requirement. Most other liberal democracies fell below this threshold some time ago.

Notably absent from the table are both Canada and the United States. Owing to the world's highest per-capita rate of legal immigration, Canada's population continues to grow rapidly compared to much of the industrialized world. As the average annual rate of population growth slows and median age rises, the compound effect of immigration and immigrants' above-average fertility rates will become ever more significant in prolonging the onset of population decline.

Fiscal constraints

On the one hand, demographic factors are likely to crowd out spending on defence. The costs incurred by aging populations, especially in combination with probable slowdowns in economic growth – with a drag of 1 per cent on gross domestic product (GDP) due to slowing employment growth in Europe, for instance – will preclude other major powers from increasing defence expenditures to catch up to the United States (Haas Citation2011). Aging populations and shrinking workforces will pressure North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member countries to spend more of their defence budgets on personnel costs and pensions at the expense of research, development and procurement of sophisticated technology. The more states spend on defence personnel and pensions, the greater the gap between United States (and allied) security capacity and that of possible challengers. The cost of engaging the United States in an international conflict grows accordingly, and the probability of a major international war engaging the United States and its allies declines. The United States population is aging, but to a lesser extent and less quickly than those of possible challengers – and some allies. As a result, the pressures of elderly care over defence spending remain favorable, and the increased substitution of labor for capital in defence budgets is bound to be smaller in the United States than among its competitors.

On the other hand, these developments are not deterministic. Countries can compensate for shrinking labor forces by substituting capital (machines) for labor to increase productivity. Higher productivity increases national wealth and, in theory, the capacity for defence spending. In practice, though, aging populations are likely to prioritize health and social spending (Global Agenda Council on Aging Citation2012).

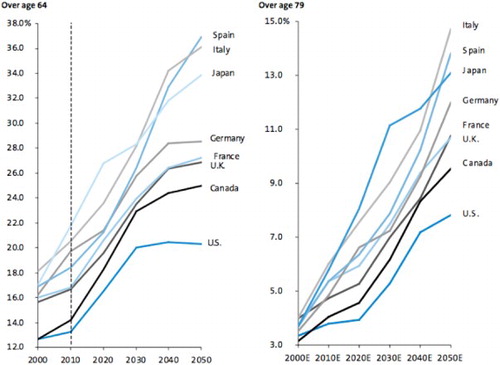

An unprecedented 70 per cent of people in the developed world are between 15 and 64 years of age. Yet, as shows, the United States and some other Anglo-Saxon countries are aging less rapidly than other countries, owing largely to higher fertility rates and immigration.

Figure 1. Elderly population by country (as a proportion of the total population). Reproduced with permission from Culhane (Citation2001, p. 6).

Never before has that proportion been as high – and it is only expected to decline henceforth. This has important implications for consumption, productivity, tax revenue and fiscal expenditures. Over the next two decades, the proportion of seniors to the working-age population will climb from fewer than 1 in 4 to 1 in 2 in countries such as Japan. In many countries, the aging effect is exacerbated by a contracting working-age cohort, although that effect is less pronounced in countries with higher immigration and/or effective pro-natalist policies, including the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Scandinavia.

The costs created by NATO allies' and great powers' aging populations will constrain spending on economic development and national defence. Among NATO allies at least, the massive costs of aging are likely to create so austere a financial climate that there will be little room for politicians to begin substantial new spending in areas not related to the care of seniors. We may already be witnessing this trend: The Japanese government is on record as stating that general expenditures will have to be cut 25–30 per cent to cope with expenses associated with population aging.

Similar pressure for cuts in defence spending to finance elder-care costs are evident in France and Germany. In February 2006, the European Commission warned Germany that it had to cut discretionary spending across the board “to cope with the costs of an aging population.Union” (Haas Citation2011:56). Speaking on behalf of the government, Germany's then Minister of Finance, Peer Steinbrück, agreed with this analysis and promised to put the commission's recommendations into practice. This decision is a continuation of a policy that Germany has followed over the past decade of “letting defence spending languish … while investing in social welfare instead.” Even in the post-September 11 world, “cutting social programs or raising taxes to buy weapons is considered [in Germany] politically impossible.”

Also in 2006, the French president created the Public Finance Guidance Council, led by the prime ministers and the ministers of the economy, finance and industry, whose primary purpose is to reduce France's national debt. It has grown significantly in recent years in no small measure due to increasing costs for elderly care. The council's primary policy mandate is to reduce to a substantial degree expenditures “of all public players,” (Office of the Prince Minister, France Citation2006) including the military.

Population aging is likely to crowd out military spending – but not just in the democratic world. China, for instance, is projected to become the first country to grow old before becoming an advanced industrial state. Even if its economy were to continue growing rapidly, by 2035, its median age will reach that of France, Germany and Japan today, but at levels of per-capita GDP that are significantly lower, and with massive unfunded pension liabilities of state-owned enterprises (Haas Citation2011). With its economic and fiscal constraints approaching those of most Western European countries, but with far greater shortfalls between the government's obligations to the elderly versus saved assets, China's ability to invest in defence and security will be crowded out as its leaders, by about 2020, will be faced with a dilemma: tolerate growing levels of poverty among a mushrooming elderly population, or curtail other spending to provide the requisite resources to safeguard internal stability by alleviating these circumstances (Jingyuan Citation2002, Longman Citation2004, England Citation2005, Eberstadt Citation2006).

No country will be able to challenge NATO's and especially the United States's military dominance without the ability to wage highly technologically sophisticated warfare (Posen Citation2003). Societal aging, however, will cause militaries to spend more on personnel and less on capital, such as weapons development and procurement. This trend is already prevalent among NATO member countries, especially when escalating pension and health-care liabilities are factored in. It is sometimes said that NATO's European members have the most heavily armed pension systems in the world. Since 1995, both France and Germany have consistently dedicated nearly 60 per cent of their military budgets to personnel. Canada spends about half its budget on personnel. Germany spends almost four times more on personnel than on weapons procurement. France, Japan and Russia spend nearly 2.5 times more. By contrast, the United States dedicates less than 1.3 times more money to personnel than to weapons purchases (Haas Citation2011).

There are two reasons why population aging causes military-personnel costs to rise. First, as demographic growth slows but economies continue to grow, the labor market tightens. Concomitantly, the nature of modern military organizations – as Morris Janowitz (Citation1960) observed four decades ago – is less and less “an organization set apart” for a uniquely specific purpose, but instead increasingly approximate other private or public-sector organizations. As a result, it competes for the same highly skilled and educated labor. The combination of a tightening labor market and the growing competition of a small pool of highly qualified labor causes salaries to grow exponentially (European Defence Agency Citation2006). In 2008, the Russian government announced plans to raise military salaries to 25 per cent above the average wage by 2020 and to improve housing and pension benefits for military personnel. China, its conscripted force notwithstanding, had to raise officers' wages by 85 per cent and soldiers' wages by 92 per cent between 1992 and 2002. In fact, the Chinese government – which is usually coy and conservative in revealing its defence expenditures – is on record as identifying growing personnel expenses as the greatest driver in the growth of China's defence budget over those 10 years (People's Republic of China Citation2004, chap. IV).

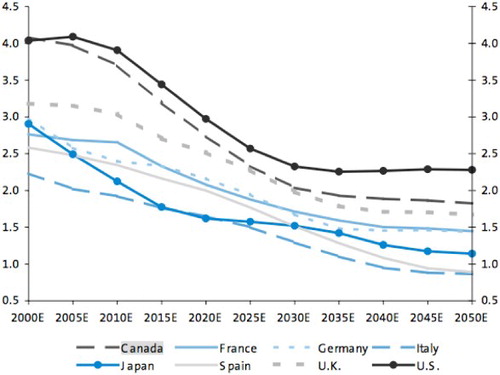

Second, pension liabilities (which are often un- or under-funded) are escalating. Russia, for instance, has been spending more on retired military personnel than on either weapons procurement or military research and development (International Institute for Strategic Studies Citation2010). Similarly, rising pension costs are the second most important reason for increases in Chinese military spending over the past decade (after the aforementioned pay raises for active personnel; International Institute for Strategic Studies Citation2010). Pensions, of course, are a liability in that they are ongoing and growing obligations that add little value to defence capabilities. In countries such as Germany, which pays its pension obligations out of general revenue (i.e., current contributions, instead of being invested to grow, pay for current liabilities – a system commonly known as “pay as you go”), every Euro spent on retirement benefits is one Euro less to spend on other services, let alone weapons, research or personnel. The United States, the United Kingdom and Canada, by contrast, use funded pensions to augment social security. Pay-as-you-go systems redistribute revenue from the working-age population to pensioners through taxes. When the benefits paid replace a high proportion of average earnings, they also create a disincentive to save and work past the normal retirement age, both of which depress GDP growth (an issue to which we shall return below). In light of population aging, pay-as-you-go systems are fiscally unsustainable because they have to be paid for either through tax increases by the working-age population or through issuance of government debt (thus crowding out defence spending). Yet many pay-as-you-go countries already register some of the highest marginal tax rates in the world. This is problematic insofar as high payroll taxes are a drag on a workforce's competitiveness. Pay-as-you-go is a vicious circle: as countries raise taxes to pay for pay-as-you-go, their workers become increasingly uncompetitive, thus further undermining the ability to pay for the pay-as-you-go system. As the dependency ratio of the working-age population to elderly in Germany is halved by 2050 (), considerable increases in payroll taxes are to be expected.

Figure 2. Elderly support ratio: actual workers/population aged over 64. Reproduced with permission from Culhane (Citation2001, p. 10).

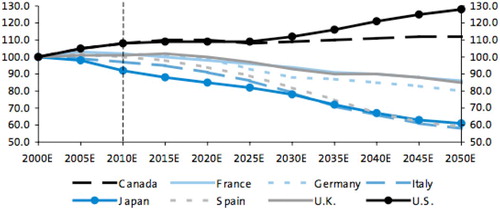

As Europe, Japan and South Korea lose one quarter to one third of their prime labor force by 2050, the dependency gap widens. is notable for stagnating or declining populations of prime working age due to aging outpacing growth even in countries with high rates of immigration, such as France, Spain and Switzerland.

Table 2. Aging and labor force change in major European and other countries, 2009–2050.

While their labor force faces an unprecedented decline, the proportion of their population over 60 years of age will rise by 50 per cent on average. However, in countries whose labor force continues to grow, such as the United States, Canada and Spain, the proportion of the population over 60 will actually double over the same period, to 16–17 per cent in the United States and 28–30 per cent in Canada, for example. Similar trends, albeit time-delayed, obtain for South Korea, China and Ireland. As details, by 2050, the population over 60 years of age will reach 35 to 40 per cent in many of these countries. Europe's working-age population has been on the wane since its apex of 480 million in 2005 and, by 2050, is expected to revert to its 1950s level of 330 million.

A growing dependency ratio aggravates the situation further by depressing GDP growth as people work less, exercise their exit option in favor of lower-tax jurisdictions, migrate to the underground economy, opt not to work at all and, squeezed by high taxes, opt for fewer children. Modest retirement promises and funded public and private pension plans have direct and indirect benign effects on demographic growth by encouraging fecundity and immigration along with stronger economic-growth prospects, thus positioning countries that operate in this vein demographically and fiscally more robustly with respect to their international-security capacities.

There are nuances nonetheless: high tech is quickly becoming integral to full-spectrum warfare in the twenty-first century (Singer Citation2009). That capability is expensive, though, because it requires a critical mass of research in both research and development and a capability to deploy on a grand scale. That explains why the United States is more heavily invested in technology than its allies. Given a choice imposed by resource constraints, allied capabilities are erring on the side of conventional warfare. For Canada and its mid-sized allies, technology plays a pivotal yet subsidiary role in warfare, in part because resource constraints due to demographic developments make it difficult to sustain equivalent conventional and technological capacities.

As populations age and the dependency ratio between the old and the young is strained, pension systems turn out to be integral to the capacity to contribute to international security. Funded pension systems redistribute income through the purchase of assets by workers and the sale of assets by retirees. As they encourage workers to save, they increase capital and, thereby, productivity and GDP growth. The United States and Canada have fairly well-funded pension systems (especially compared to China, France, Germany and Russia) (Culhane Citation2001).

Owing to low social-security promises, the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada are less affected by social aging. As borne out in the political culture of those countries, polling data show that Americans have the highest prediction of when they would retire (67.2) and (by far) the lowest expectations regarding governmental support of their retirement (AgeWave and HarrisInteractive Citation2009). What is more, countries that are already facing the greatest expenditure burden on aging populations aggravate matters further: instead of liberalizing working conditions, they ease their unemployment burden by encouraging early retirement, thus enlarging the pool of unused potentially productive labor. That aggravates social conflicts over issues such as pensions, migration and labor/employer relations, and presents opportunities for countries to invest instead in technology to spur gains in productivity (Friedman Citation2005).

Although the United States' population, too, is aging, documents that due to above-replacement fertility and persistent immigration, America has the youngest population among G8 countries.

Table 3. Median age by country, 1950–2050.

The combination of fertility and immigration (along with comparatively low welfare-state and state-pension obligations, with most of the latter liabilities funded) will strengthen America's relative demographic position vis-à-vis the other G8 countries. According to 2008 estimates published by the United Nations, between 2010 and 2050, the United States will remain the largest net receiver of international migrants. Between 2008 and 2010, Gallup conducted a rolling survey of 401,490 people across 146 countries (Esipova and Ray Citation2011). It found that 14 per cent of the world's population – some 630 million people – would like to migrate to another country if they could. People across sub-Saharan Africa (33 per cent), North Africa (23 per cent) and the Middle East, and Latin America (23 per cent), had the greatest urge to move permanently. The United States as the destination of choice (23 per cent) is followed by Canada and the United Kingdom (7 per cent each). Half of those migrating to the developed world now choose the United States, which results in an annual rate of migration five times greater than that of the second-place country in this category: Canada (1.1 million people vs. 214,000). However, as a proportion of its total population, Canada will continue to have the highest immigration rate in the industrialized democratic world. The compound and selection effects of migration to these two allies means that North America's global leadership role is likely to prevail – and that Canada is likely to become an even more important defence partner because of its relatively rosy demographic and, as of late, fiscal outlook. Still, these developments are structural, not deterministic: While Canada maintains comparatively greater potential to spend more on defence than some other allies, public policy constraints imposed by an aging population and other intervening variables impose considerable constraints on doing so. Nonetheless, while key allies, including the United States, are cutting their troop strength precipitously, Canada has been holding its own on a per-capita basis (International Institute for Strategic Studies Citation2010), thus bolstering the argument that, relatively, Canada's defence clout within the alliance, and Canada's importance as a defence partner to the United States, is on the rise. Concomitantly, on a per-capita basis and as a percentage of GDP, the extent of Canada's defence reductions is actually fairly tame (SIPRI Citation2014), which bolsters the argument about Canada enjoying greater demographic leeway.

By contrast, lists the countries whose median age is expected to be 50 or higher by 2050. European countries figure prominently, but with key notable exceptions throughout Western Europe in what neoconservative theologian George Weigel piously fantasizes about as “Europe committing demographic suicide, systematically depopulating itself” (Weigel Citation2005). Europe is about to witness “the greatest sustained reduction in population since the Black Death in the fourteenth century” (Ferguson Citation2004, p. 13).

Table 4. Countries whose median age is projected to be 50 or over by 2050.

China's median age will surpass the United States' by 2025. In China, France, Germany, Japan and Russia, the working-age population is also projected to decline by 2050, or increase modestly (the United Kingdom). contrasts those trends with the United States, where the working-age cohort is expected to grow by 23 per cent.

Figure 3. Working age population (aged 20–60) by country, 2000–2050 (index 2000 = 100). Reproduced with permission from Culhane (Citation2001, p. 8).

(North) America's youth demographics will help offset some of the challenges of social aging. As a rule of thumb, countries with slower demographic growth tend to have slower GDP growth. Yet the differences are significant: whereas GDP is expected to rise by only 30 per cent in Japan, Spain and Italy as a result of an aging population, it is projected to rise some 300 per cent in the United States. That is, demographic differentials (largely owing to higher fertility) account for a difference in economic growth of a magnitude of 10!

Discussion

The aging crisis is less acute in some countries than in others. Where it is less acute, countries have better prospects to shape international security according to their national interests. Still, the magnitude of the costs will be unprecedented (due to the compound effect of diminished overall contributions and expanded demand), as will the constraints they will impose on security spending. The more countries sustain their comparative demographic advantage and relatively superior ability to pay for the costs of their elderly population, the more we are likely to see a middle-power renaissance among those allied countries that continue to enjoy favorable demographic developments. It is in the allies' security interest to rein in the costs of old-age security and health care, minimize the gap between elder-care obligations and resources set aside for them, raise the retirement age, and maintain as open an immigration policy as possible to keep their median age down. Proactive policies that are designed to take full advantage of the opportunities created by global aging while mitigating the costs created by this phenomenon will enhance international security through the twenty-first century.

Some countries are better positioned to weather demographic change than others and some will even have security benefits accrue to them, especially as a result of the continental multiplier effect in North America that is generated by virtue of the demographic advantage and concomitant economic growth enjoyed by the United States. In the context of slowing economic growth, increased costs of labor, and defence spending that is being crowded out, no state or combination of states appears likely to overtake the United States' position of economic and military dominance. Haas argues that global aging is likely to extend American hegemony. Not only will the other major powers lack the resources necessary to overtake the United States' lead in economic and military power, but also deepen it as these other states are likely to lag behind the United States (Haas Citation2011). Demographic developments suggest that there is no other country on the horizon that is able to muster America's combination of innovation, economic growth and low ratio of spending on capital versus personnel (which is key to military dominance on the high-tech battlefield of fourth-generation warfare). Global population aging is thus likely to generate considerable security benefits for North America.

At the same time, demographic changes portend a growing gap between the United States and select allies on the one hand, and the rest of NATO on the other hand. As more countries, and especially NATO allies, face growing fiscal constraints, fewer allies will end up having to pay for a growing share of the common international security interests. But even for countries that are relatively well positioned, it is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain military spending as they face their own fiscal challenges growing out of population aging. In effect, the United States' defence budget's expenditure burden within NATO is on the rise: from 50 per cent during the Cold War (66 per cent including Canada) to 75 per cent today, and a projected 85 per cent once known allied cuts are fully implemented. But among the six countries that have been covering 90 per cent of total NATO expenditures, only one country's contribution has remained stable as a percentage: Canada (at 1.8 per cent). The United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and the others' contributions have been waning. Although the transatlantic expenditure bifurcation is widening as a result, Canada is notably absent from American concerns (Larrabee et al. Citation2012). Of course, figures can be deceiving insofar as the type of capabilities, force structure and strategic posture is equally important, but is not as readily quantifiable. Nonetheless, the economic impact of population aging is already challenging allied countries that lack the fiscal room necessary to maintain the extent of their global position and involvement, let alone adopt major new initiatives. For the sake of collective burden-sharing, the remainder are having to do more with less. Realists might contend that this puts NATO at risk. Liberal institutionalists, by contrast, conceive of NATO as a mechanism to overcome collective action problems: allies who are drawing down are becoming more reliant on the United States, while for the United States, the alliance serves the purpose of stemming the bleeding by forestalling a race to the bottom.

Global aging and youth unemployment fueled by high fertility are compounding the problem. The latter is prone to make the twenty-first century particularly unstable for allied international interests (Cincotta et al. Citation2003). Population aging will beset much of the world at some point this century. In fact, the aging problem in many developing states is likely to be as acute as for industrialized countries, but the former have the added disadvantage of growing old before growing rich, thus greatly handicapping their ability to pay for elder-care costs (Qiao Citation2006). If the strain on governments' resources caused by the cost of aging populations becomes sufficiently great, it may exacerbate systematically both the number of fragile states and the extent and depth of that fragility. Fragile states are prospective havens for organized crime and terrorism. The prospect of having to contend with a proliferation of fragile states with significantly fewer resources at the allies' disposal could prove the single greatest security challenge of this century (Jackson and Howe Citation2008, chap. 4–5). This is complemented by an already reduced capacity to realize other key international objectives, including preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, funding nation-building, engaging in military humanitarian interventions, and various other costly strategies of international conflict resolution and prevention.

Several important implications follow for defence and the armed forces. First, bilateral defence relationships will become more important as the United States’ proportion of the developed world's population remains fairly constant (). Among its allies, America will be shouldering a growing fiscal burden of relative expenditures on international security.

Figure 4. United States and developed world population as a percentage of world total.

Population aging will hamper the ability of select allies to “step up to the plate.” Following the logic of relative population aging, the Anglo-Saxon allies – that is, not only the United States but to a lesser extent Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia – are becoming relatively more important allies.

Due to demographic aging, the probability of a major international war continues to diminish. Specifically, the demographic challenges faced by China and Russia make an international military conflict between one of them and North America increasingly unlikely. For the same reason, it is highly improbable that any disputes over the Arctic would ever escalate to the point of a war. Global aging also increases the likelihood of continued peaceful relations between the United States and other great powers. Copeland (Citation2000) and Gilpin (Citation1981) have shown that the probability of international conflict grows when either the dominant country anticipates a power transition in favor of a rising state or states, or when such a transition actually occurs. By adding substantial support to the continuation of American hegemony, global aging counteracts either outcome. Haas (Citation2011) surmises that an aging world thus decreases the probability that either hot or cold wars will develop between the United States and other great powers. Given its geopolitical location, this portends well for middle powers such as Canada.

As apprehensive as countries may be about contributing troops, as situations arise where they deem intervention in their interest, fewer allies will be in a position to contribute and those countries with more favorable demographic trends such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but also the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries, should prepare themselves (both at the level of mass psychology and operationally) to take on a greater share of the burden. This is not a normative observation but a sociological one: among many of the traditional allies, fiscal and defence capabilities are likely to erode further. So, if a country deems a given situation as in need of intervention, it will have to put its money (and troops) where its interests are.

Defence budgets will continue to be strained. Although the strain will be less than that experienced by some NATO allies, population aging in North America is bound to marginalize defence spending. So, allied armed forces will need to learn to make do in a severely constrained fiscal environment. For example, at its current 4:1 ratio of personnel to capital, the last thing the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) will want to do is expand its troop strength, especially while its budget is contracting. On the contrary, the CAF will want to work on diminishing its troop levels to free up money for development and procurement. This will be especially difficult in a tight labor market that will cause the costs for highly qualified personnel to rise significantly. The way out of this predicament is to curtail the size of the force, focus on education to impart requisite skills, and develop an aggressive plan to substitute capital for labor (or, at an absolute minimum, ensure that personnel costs do not end up cannibalizing even more of the defence budget than they already do).

Conclusion

Never have there been so many people in the world. Never have there been so many old people. Never have they comprised a greater proportion of the population. Never have they been more affluent. And never have they wielded more political power. Such are the endogenous effects imposed by a historically unprecedented demographic horizon that is introducing considerable uncertainty into allied defence relationships by virtue of being historically unprecedented. The rise in age of the median voter and the proportion of older voters is bound to affect public policy priorities. Older people tend to be more reliant on the State than younger ones. Not only do older voters thus have an incentive to resort to rent seeking, because of their advanced age they also have an incentive to favor short-term payoff over long-term strategy. At least three deleterious consequences follow for national defence.

First, social entitlement programs are likely to crowd out defence spending. Foreign policy rarely wins elections; domestic policy does. Even here, there are important nuances, though. The Canada Pension Plan is generally perceived as an insurance program, co-financed by employers and employees, while 70 per cent of healthcare in Canada is paid by government out of general revenue. That amount is only marginally higher than in the United States (at 60–65 per cent). In the United States, however, social security and Medicare are viewed as insurance programs, because they are funded jointly by employer and employees. In Canada, by contrast, healthcare has effectively become a government-financed entitlement program, as opposed to an insurance program. That difference explains differential voting patterns. Older voters in the United States are wealthier than the young, have substantial assets in the form of a family home (often paid for), savings, investments and pensions. They vote Republican because they oppose a large State, which they associate with high taxes. In Canada, older voters are less ideologically bifurcated and are more predisposed to relying on the State provisioning healthcare entitlements (as opposed to facilitating healthcare insurance). Yet the impact of this difference on defence spending is mitigated by differentials in marginal tax rates and the greater cost of healthcare in the United States.

Second, stagnant or negative population growth appears to correlate with national economic performance. Politicians are not just loath to curtail entitlement programs; electoral logic suggests that they are actually prone to expand them to appeal to the fastest growing cohort among the electorate. Under soft economic conditions, the impact on national security spending is exacerbated.

Third, national defence in general and the management of sources of international instability in particular tend to require a long view, which will be increasingly difficult to defend as the gambit of existential political payoffs for an aging population grows.

However, the United States and Canada get away relatively unscathed. Canada's demographic trends are less favorable than America's, but they are better than those among many allies. This bodes well for the bilateral defence relationship between the two countries. Although Canada will be relying more heavily on its partnership with the United States in matters of defence and international security, its relatively favorable demographic trends will make Canada an increasingly indispensable defence ally for the United States. Yet the United States does not appear to be leaning on Canada to assume a greater burden in sharing North American and NATO defence. Ostensibly the United States is satisfied with Canada's contribution. Canada will continue to benefit from a great deal of discretion and autonomy over both the extent of the burden it shares, and how it shares that burden. Mounting co-dependence in defence and international security notwithstanding, Canada is thus poised to continue to enjoy considerable leverage over the bilateral defence relationship.

References

- AgeWave and HarrisInteractive. 2009. Retirement at the Tipping Point: The Year that Changed Everything. A National Study Exploring How Four Generations Think About Retirement. Available from: http://www.agewave.com/RetirementTippingPoint.pdf [accessed 31 March 2014].

- Anderson, M., ed., 1996. British population history: from the black death to the present day. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bloom, D.E., Canning, D., and Fink, G. 2011. Implications of Population Aging for Economic Growth. Harvard Program and the Global Demography of Aging Working Paper No. 64. Available from: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/pgda/WorkingPapers/2011/PGDA_WP_64.pdf

- Cincotta, R., Engleman, R., and Anastasion, D., 2003. The security demographic - population and civil conflict after the cold war. Washington, DC: Population Action International. Available from: http://www.populationaction.org/Publications/Report/The_Security_Demographic/The_Security_Demographic_Population_and_Civil_Conflict_After_the_Cold_War.pdf

- Copeland, D.C., 2000. The origins of major war. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Culhane, M.M., 2001. Global aging: capital market implications. New York: Goldman Sachs Strategic Relationship Management Group.

- Eberstadt, N., 2006. Growing old the hard way: China, Russia, India, Policy Review 136 (April/May).

- England, R.S., 2005. Aging China: the demographic challenge to China's economic prospects. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Esipova, N. and Ray, J., 2011. International Migration Desires Show Signs of Cooling . 11 June. Available from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/148142/International-Migration-Desires-Show-Signs-Cooling.aspx

- European Defence Agency, 2006. An initial long-term vision for European defence capability and capacity needs. Brussels: EDA.

- Ferguson, N., 2004. The Way We Live Now: 4–4–04; Eurabia? The New York Times Magazine, 4 April: 13.

- Fischer, C.S. and Hout, M., 2006. Century of difference: how America has changed in the last one hundred years. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2006.

- Friedman, B. 2005. The moral consequences of economic growth. New York: Alfred Knopf.

- Gilpin, R., 1981. War and change in world politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Global Agenda Council on Aging Society, 2012. Global population aging: Peril or promise? World Economic Forum: Committee on Improving the State of the World, Cologny, Geneva.

- Haas, M.L. 2011. America's golden years? US security in an aging world. In: M. Duffy Toft, J. Goldstone and E.P. Kaufmann, eds. Political demography, op. cit., 49–62.

- Horowitz, D., 1985. Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2010. The military balance 2010. London: Routledge.

- Jackson, R. and Howe, N., 2008. The graying of the great powers. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2008.

- Janowitz, M., 1960. The professional soldier: a social and political portrait. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Jingyuan, K., 2002. Implicit pension debt and its repayment. In: M. Wang, ed. Restructuring China‘s social security system, 2. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

- Kaufmann, E.P. and Duffy Toft, M., 2012. Introduction. In: M. Duffy Toft, J. Goldstone and E.P. Kaufmann, eds. Political demography, op. cit., 3–9.

- Larrabee, F.S., et al., 2012. NATO and the Challenges of Austerity. Monograph 1196. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

- Livi-Bacci, M., 2007. A concise history of world population, 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Longman, P., 2004. The empty cradle: how falling birthrates threaten world prosperity and what to do about it. New York: Basic Books.

- OCED. 2011. Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care, chapter 2. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/47884543.pdf

- Office of the Prime Minister, France, 2006. First National Conference on Public Finance. Paris: Office of the Prime Minister. Available from: http://archives.gouvernement.fr/villepin/information/actualites_20/1ere_conference_nationale_finances_55058.html

- People's Republic of China, 2004. White Paper on National Defense, 2004. Available from: http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/china/doctrine/natdef2004.html (accessed 31 March 2010).

- Posen, B.R., 2003. Command of the commons: the military foundation of US hegemony. International Security, 28 (1), 5–46. doi: 10.1162/016228803322427965

- Qiao, H. 2006. Will China Grow Old Before Getting Rich? Global Economic Paper No. 138. New York: Goldman Sachs Economic Research Group.

- Singer, Peter W., 2009. Wired for war: the robotics revolution and conflict in the 21st century. New York: Penguin Books.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2014. Military Expenditure Database. Available from: http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/milex_database

- United Nations Secretariat. Population Division, 2007. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision Population Database. Available from: http://esa.un.org/unup

- Weigel, G., 2005. The Cube and the Cathedral: Europe, America, and Politics without God. New York: Basic Books.