ABSTRACT

The application of systemism, an innovative and user-friendly technique for generating lucid, graphic summaries of analytical arguments, can enhance the study of Canadian foreign policy. As research and pedagogy on Canada and international relations move forward, its content becomes increasingly vast and intellectually diverse. Systemism offers both a means and a method toward enhanced communication in the face of challenges posed by the rapid expansion of topics and the proliferation of new theories and terminology in the fast-paced world of the new millennium. This is the motivation for a special issue of CFPJ that will show systemism in action across a wide range of issues and locations. This introductory article will proceed in four sections. The first section provides an overview of the project as a whole. Section two introduces systemism as a graphic approach toward the communication of ideas. The third section applies systemism to convey the framework for analysis from the standard textbook in the field – The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (Nossal, K. R., Roussel, S., & Paquin, S. The politics of Canadian Foreign Policy. Queen’s policy studies series (4th ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015). Section four outlines the articles that follow in making up the special issue.

RÉSUMÉ

L'application du systémisme, une technique innovante et conviviale permettant de générer des résumés graphiques et lucides d'arguments analytiques, peut améliorer l'étude de la politique étrangère canadienne. À mesure que la recherche et la pédagogie sur le Canada et les relations internationales progressent, leur contenu devient de plus en plus vaste et intellectuellement diversifié. Le systémisme offre à la fois un moyen et une méthode pour améliorer la communication face aux défis posés par l'expansion rapide des sujets et la prolifération de nouvelles théories et terminologies dans le monde au rythme soutenu du nouveau millénaire. Voilà ce qui motive la publication d'un numéro spécial du CFPJ qui montrera le systémisme en action à travers un large prisme de questions et de lieux. Cet article introductif se développera en quatre sections. La première section donne un aperçu du projet dans son ensemble. La deuxième présente le systémisme comme une approche graphique de la communication des idées. La troisième section applique le systémisme pour transmettre le cadre d'analyse du manuel standard dans le domaine - The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (Nossal, K. R., Roussel, S., & Paquin, S. The politics of Canadian Foreign Policy. Queen's policy studies series (4ème édition). Montréal : McGill-Queen's University Press, 2015). La quatrième section présente les articles qui composent le numéro spécial.

Overview

Canadian foreign policy is a specialized field in one way, but quite encompassing in others. On the one hand, it focuses on the experiences of a single state. On the other hand, over time the range of topics included within, and methods used to study, Canadian foreign policy have come to reflect input from any number of academic disciplines. Like International Relations (IR) at its modern point of origin in the aftermath of World War I, the study of Canadian foreign policy featured and maintained a state-centric orientation.Footnote1 Accounts of diplomacy and elite-level decision-making took center stage, with an emphasis on historical cases and a kinship with area studies. A century later, Canadian foreign policy is vast in comparison to its early days. Subject matter still includes the interaction of states with each other but also incorporates the activities of international organizations and transnational actors. Methods have expanded as well, with inspiration from disciplines such as psychology and economics. In these ways, Canadian foreign policy continues to resemble IR, the discipline within which it resides: rapidly expanding in both size and diversity. Important differences also exist and will be brought into the analysis at an appropriate point.

The application of systemism, an innovative and user-friendly technique for generating lucid, graphic summaries of analytical arguments, can enhance the study of Canadian foreign policy. As research and pedagogy on Canada and international relations moves forward, its content becomes increasingly vast and intellectually diverse. Systemism offers both a means and a method toward enhanced communication in the face of challenges posed by the rapid expansion of topics and the proliferation of new theories and terminology in the fast-paced world of the new millennium. This is the motivation for a special issue of CFPJ that will show systemism in action across a wide range of issues and locations.

This introductory article will proceed in three additional sections. The second section introduces systemism as a graphic approach toward the communication of ideas. The third section applies systemism to convey the framework for analysis from the standard textbook in the field – The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (Nossal, Roussel, & Paquin, Citation2015). The final section outlines the articles that follow in making up the special issue.

Systemism

What is systemism? It is a way of thinking about theory that emphasizes completeness and logical consistency (Bunge, Citation1996). Systemism is an approach rather than a substantive theory (Bunge, Citation1996, p. 265). It focuses on building comprehensive explanations; systemism transcends individualism and holism as the other available “coherent views” with respect to the operation of a social system (Bunge, Citation1996, p. 241). The essence of systemism is its emphasis on graphic communication to obtain those goals. A shift to a visual approach is in line with findings from educational psychology, which emphasize a combination of words and graphics to maximize comprehension and retention of analytical arguments (Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, Citation2009). With a combination of text and systemist visualization, it becomes possible to convey even complex arguments in a way that helps to counteract a pernicious side-effect of specialization, notably language that quickly can become inaccessible.Footnote2

Important to note also is the ability of systemism to pass an important test: offering graphics that improve rather than impede understanding. The concept of “hyperactive optical clutter” is introduced in Tufte (Citation2006), an authoritative exposition on how to communicate more effectively through the implementation of graphics. Systemist visualizations are mindful of Tufte’s (Citation2006) admonitions about problems arising from graphics that contain too much text and end up making things worse rather than better. The archetypal and perhaps most widely-cited instance of hyperactive optical clutter is the PowerPoint slide that contains so much material that the viewer becomes annoyed and even tunes out altogether (Tufte, Citation2006). By contrast, systemist graphics contain only a limited amount of text. These visualizations are based on relatively simple notation and thereby become easy to understand and compare with each other.

Systemist graphics of many hundreds of books and articles exist in an expanding archive from the Visual International Relations Project (VIRP). The VIRP archive will be made accessible to the public at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association in the spring of 2022. Graphics for articles in this special issue of CFPJ on systemism also will go into the VIRP archive, with creators being cited whenever these visualizations are referenced in subsequent publications.

How are items to be selected among many and perhaps even millions of possibilities? Resources are finite and thus it is essential to set priorities in order to produce an archive that attracts interest and produces academic value for those accessing it. Emphasis is placed, therefore, upon the incorporation of highly visible items from academic IR and frameworks from other disciplines that are referenced frequently, such as the logic of collective action from Economics (Olson, Citation1965). At the same time, to reduce any sense of elitism within the VIRP, an effort is made to include items that are not cited a vast number of times. To some extent, this ends up as a convenience sample because, for at least the near future, most of the work on the archive is being produced at USC and includes items that are familiar to the leadership of the VIRP. Since the archive is expanded continuously, insights from recent literature and new scholars in the field just like traditional classics can be accessed in the archive to make the vast amount of scholarship more comprehensive as a whole. Furthermore, a conscious effort is made to be inclusive, notably bridging significant ongoing gaps such as problem-solving versus critical IR. As participation expands beyond those presently involved in leading the VIRP, it is expected that the archive will become more representative of the discipline as a matter of course.

Systemism as a method emphasizes the diagrammatic exposition of cause and effect that promotes comprehension and rigor. Thus, the overall value of systemism is that its visual representations clarify relationships expressed in a theory. Systemism goes beyond holism and reductionism through a focus on all types of connections needed to fully specify a theory.Footnote3 Systemism thereby facilitates the comparison of alternative visions through a clear and comprehensive presentation. Consequently, systemism is both an approach and a method that, through its lucidity and completeness, has the potential to benefit the discipline as a whole.

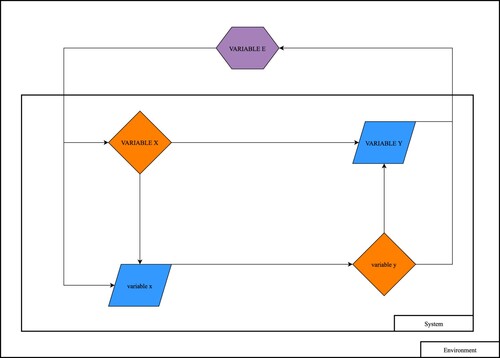

depicts functional relations in a social system from a systemist point of view. The varying shapes and colors that appear will be explained a bit later.

Figure 1. Finding Philosophy in Social Science (Bunge, Citation1996). Diagrammed by: Michael R. Pfonner and Patrick James. This figure represents a generic set of variables and full set of potential connections involving a system and its environment.

depicts the system and its environment. Variables that operate at macro (VARIABLE X, VARIABLE Y) and micro (variable x, variable y) levels of the system appear at its upper and lower levels. In this diagram and others based on systemism, UPPER- and lower-case characters correspond to MACRO- and micro-level variables, respectively. The macro and micro levels are designated in line with the research question at hand. For example, consider a study of the foreign policy of Thailand. A natural designation for the macro and micro levels would be the government and society of that state as a system. The environment for Thailand then would be the international system beyond its borders.

While the preceding set of labels – state and international system – is the default in the VIRP archive, various other combinations are observed. Take, for instance, a study of IR as a discipline. The field of IR would become the system. The discipline as a whole and individual scholars within it would correspond, respectively, to the macro and micro levels. The world beyond IR would serve as its environment. In all instances, boundaries for system and environment should reflect what is anticipated to be most helpful in the visualization of the logic of a particular argument. This variation in the diagrams is welcomed to ensure the utmost level of lucidity and accuracy when producing an individual diagram while at the same time adhering to a clearly defined, overarching structure to facilitate the integration of paradigms and methods.

Four basic types of linkages are possible for macro and micro variables with each other: macro-macro (VARIABLE X → VARIABLE Y), macro–micro (VARIABLE X → variable x), micro–macro (variable y → VARIABLE Y) and micro-micro (variable x → variable y). The figure also includes a variable to represent the environment (VARIABLE E). The environment can be expected to stimulate the system and vice versa: (i) “VARIABLE E → VARIABLE X” and “VARIABLE E → variable x” and (ii) “variable y → VARIABLE E” and “VARIABLE Y → VARIABLE E”. All potential types of connection for a theory to incorporate now are in place.Footnote4

provides the notation for systemist figures. Color and shape are used to designate roles for variables. The functions of variables as they appear along pathways will be explained, wherever possible, using a river as an analogy.

Table 1. Systemist notation.

An initial variable takes the form of a green oval, while a terminal variable is depicted as a red octagon. In virtually all instances these designations are arbitrary and based upon starting and finished points for argumentation within a given text. For the point of initiation, it always is possible to think of something else prior and, in principle, imagine effects beyond what is marked as the point of termination. The initial and terminal variables, respectively, are analogous to the source and mouth of a river.

With exactly one connection coming in and out, a generic variable appears as a plain rectangle. In the context of a river, this might be thought of as a simple flowing forward – neither a point of convergence nor divergence for streams of water.

Three variable types – convergent, divergent and nodal – include contingency. A convergent variable, indicated with a blue parallelogram, designates a bringing together of multiple pathways. It is the same as a point of confluence for multiple rivers. Represented with an orange diamond, a divergent variable signals the onset of multiple pathways. It is analogous to the emergence of multiple streams from a single river. A purple hexagon denotes convergence followed by the divergence of pathways – a nodal variable. In the riparian context, this would refer to multiple streams joining together and then coming apart. A co-constitutive variable – one with mutually contingent variables – appears in bifurcated form. This type of variable is included to recognize co-constitution as an essential aspect of constructivist theorizing in particular and critical scholarship in general.

Line segments are depicted in different ways, depending on what they are supposed to represent, and will be explained as relevant within respective figures. All of this combines to facilitate the creation of graphic summaries with high mutual intelligibility and thus the potential to assist in managing a field’s complexity and attendant communication-related challenges.

Return for a moment now to and the notation within it becomes intelligible. There are divergent and convergent variables – orange diamonds and blue parallelograms, respectively – at both the macro and micro levels of the system. The lone variable in the environment is of the nodal variety – a purple hexagon.

With notation in place, several observations can be made at this point about the relevance of systemist graphics to cause and effect. Systemism, in a word, is unforgiving. Its graphic format requires arguments to be made explicitly, with errors of either omission or commission being much easier to detect than from words alone. The structure of an analysis with regard to cause and effect also comes into bold relief. Consider necessary and sufficient conditions. If there is just one pathway in a diagram – meaning the absence of any divergent, convergent or nodal variable – all conditions are deemed necessary. Sufficient conditions are represented in all diagrams that contain at least one terminal variable. Systemist diagrams also identify permissive and effective causes. An effective cause is any variable leading directly into the terminal variable. A permissive cause is most directly visible in the form of an initial variable, from which multiple connections ensue and the terminal variable serves as a point of culmination. Another way of thinking about the cause of effect that can be facilitated by systemist visualization is counterfactual analysis. Those arguments, which obviously concern events that take place only in the abstract and can be especially challenging to understand, are in a particular position to benefit from a parallel graphic exposition.

With so many analytical frameworks and methods available already, it might be reasonable to ask this question: Who needs systemism? Once answered, the question itself seems ironic. It is precisely the scope and scale of research in place that makes the adoption of an approach such as systemism a major priority for all academic disciplines in the new millennium. The study of Canadian foreign policy is no exception. This argument is based on the sociology of knowledge as the field has progressed over the course of decades. In addition to Canadian Foreign Policy Journal and International Journal, the pages of academic material relevant to the field continue to expand at a rapid pace. So, too, does the range of disciplines represented.Footnote5

Systemist graphics can be implemented in three basic ways. One application is to a specific publication, namely, to tell its story about cause and effect in graphic form. This can begin with a pencil sketch and move through stages that include consultation with (one of) the author(s) of the respective piece.Footnote6 Two other techniques also exist within systemism: systematic synthesis and bricolagic bridging. Each is introduced briefly in turn.

Systematic synthesis refers to the assembly of causal connections from a set of studies into one representative diagram. Thus, systematic synthesis is in line with the logic of confirmation – identifying the degree of consensus that exists about a given research question. One example would be putting together the propositions confirmed in 14 studies of the causes of war based on data from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project. The study assembled an overall network of cause and effect out of individual hypotheses that focused on crisis escalation to war (James, Citation2019b). A graphic of this kind can be accessed as a type of visual “literature review”. It also could be used to summarize an area of academic literature within a lecture or discussion section by a professor or teaching assistant. Furthermore, a systematic synthesis might be of value as a graphic overview and aid to memory – to either an undergraduate student studying for a test or a doctoral student preparing for qualifying exams. Systematic synthesis could be carried out for any number of areas in order to advance communication within the field of Canadian foreign policy.

Bricolagic bridging might be introduced most easily with an antinomy – explaining its meaning through a point of contrast. In architecture, a plan is put forward, materials are obtained, and some kind of structure is assembled. The end product is expected to correspond as clearly as possible to what appears in the design. Bricolage, by contrast, consists of assembling materials in the absence of a plan.Footnote7 Thus, it is in line with the logic of discovery – generating rather than testing hypotheses. The priority in bricolagic bridging is to take studies that normally would not be engaged with each other and see if assembly into a single diagrammatic exposition stimulates new ways of thinking. By implementing this approach, Canadian foreign policy could counteract tendencies toward segmentation and even isolation within a vast and expanding field of study.

One further advantage of systemism is that averts a debate about the virtues of qualitative versus quantitative methods. Systemist graphics can convey arguments from any source and, through its rigor and lucidity, results in them being more comprehensible in comparison to appearance in words alone. As a consequence, the method entails very low barriers to entry. Participants in the VIRP are able to “get up to speed” with grasping and retaining the basic principles of creating entries in just a matter of hours.Footnote8 It is worth reiterating here that the technique also is in line with research from educational psychology that identifies a reinforcing effect for visual and verbal communication with respect to understanding and retention of material (Pashler et al., Citation2009).

Systemism also can help to move forward episodic and inconclusive debates that take place about Canadian foreign policy vis-à-vis its overall degree of progress. Consider, as a relatively recent and prominent example, the views of Gecelovsky and Kukucha (Citation2008) vs. Boucher (Citation2014).

On the one hand, Gecelovsky and Kukucha (Citation2008) pass an essentially favorable judgment on the field. This assessment is based on a survey of scholars who identify with Canadian foreign policy in terms of their research and teaching. Those surveyed generally (i) see the field as improving; (ii) claim to have an active research agenda; and (iii) express a high degree of satisfaction with teaching and research in the field (Gecelovsky & Kukucha, Citation2008, p. 111, 114). These survey-based findings are cited as evidence that the field of Canadian foreign policy is progressive.

On the other hand, Boucher (Citation2014) offers a more critical assessment of the field of Canadian foreign policy. This judgment is based on a survey of 531 peer-reviewed articles that appeared in leading journals from 2002 to 2012 (Boucher, Citation2014, p. 215). The standard approach in that sample of articles – just over 75% – is described as a “loose strategy” of validation that can be summed up as “casual empiricism” (Boucher, Citation2014, p. 221, 226). For such reasons, Boucher (Citation2014, p. 214, 227) sees the field of Canadian foreign policy as being in a “state of disarray” and assuredly not progressive.Footnote9

What should be made of such diametrically opposed conclusions about Canadian foreign policy? This question will be answered in the final contribution of this special issue. In that article, Gansen and James will convey an assessment of the field from a systemist point of view.

The politics of Canadian foreign policy

With four editions in print, The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (Nossal et al., Citation2015) is the industry standard.Footnote10 This textbook is at once comprehensive and friendly to any reader seeking to obtain an introduction to the subject matter. The main argument is that “a country’s foreign policy is forged in the nexus of politics at three levels – the global, the domestic, and the government – and that to understand how and why Canada’s foreign policy looks as it does, one has to look at the interplay of all three” (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. xv). The analysis is carried out in a clear and precise manner across the preceding levels, with many helpful illustrations from the history of Canadian foreign policy along the way.

What, then, in the preceding context, is the agenda of Canadian foreign policy? Nossal et al. (Citation2015, p. xv) provide a basic answer:

Those tasks are to grapple with the anarchical nature of international politics; to cope with the greater power of other political communities, particularly the United States; to protect Canada from the predations of others; to protect and advance the interests of Canadians; and to wrestle with the competing and contending demands Canadians impose on their governors. This is the enduring essence of foreign policy regardless of the era.

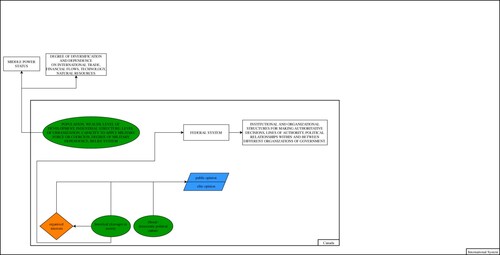

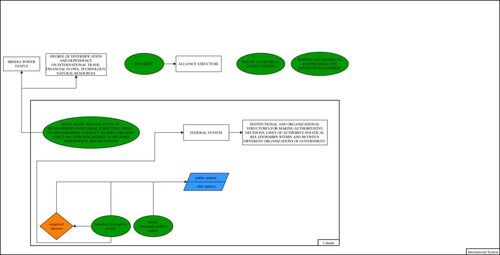

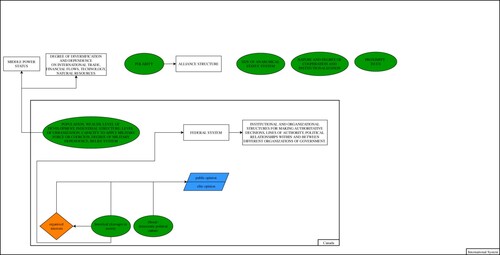

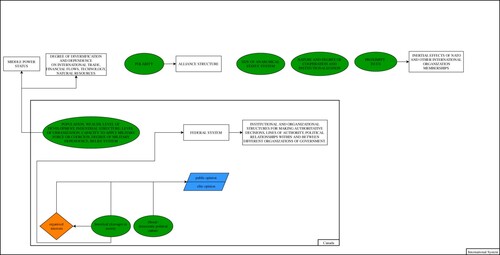

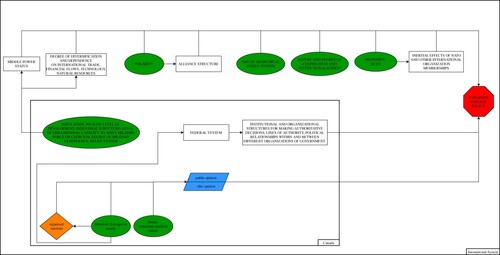

, a systemist graphic, tells the story of cause and effect from The Politics of Canadian Foreign Policy (2015).Footnote11 Canada is designated as the system, with the international system as its environment. The diagram conveys Canada as a system; state and society correspond to the macro and micro levels, respectively. Note the presence of lower- and upper-case characters for the micro and macro level variables. The diagram contains 16 variables; nine are in the international system and seven (three macro, four micro) in Canada. Seven variables are initial, six generic, one divergent, one convergent and one terminal. Note that the convergent variable also is co-constitutive. While two points of contingency exist (i.e. divergent and convergent variables), there is no nodal variable.

Figure 2. The politics of Canadian foreign policy (Kim Richard Nossal, Stéphane Roussel and Stéphane Paquin). Diagrammed by: Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

Among respective types of connection, most possibilities are in place: micro-micro, micro–macro, macro-macro, macro-system and micro-system. Absent are macro–micro, system-macro and system-micro. This is not at all surprising, given that the goal of Nossal et al. (Citation2015) is to explain foreign policy. Thus, reverberations from the system back into either state or society, along with the impact of state on society, are not developed within the current framework that addresses Canadian foreign policy as an outcome. The preceding absent types of connection stand out as potential points of elaboration for the future.

Before moving through the sub-figures, a point of explanation is in order for the layout. What are the criteria for placing one or more connections into a given sub-figure? The answer is purely pragmatic – ease of explanation. Some linkages make more sense to put forward alone, while others may be explained with greater effectiveness in combination with each other. This is not an exact science, of course, and in principle, it is possible to move through a series of connections in different ways that produce the same overall result. The process, however, is guided by consultation with authors, who have approved a final draft of their publication for inclusion in the VIRP archive.

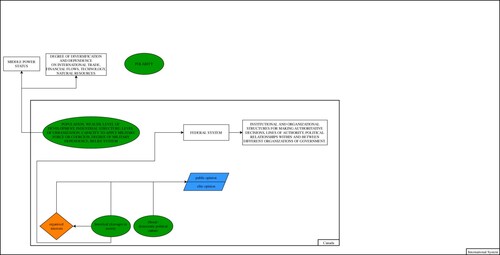

(a) begins the assembly of sub-graphics into the overall story of cause of effect in . Canada is the system, and the international system is the environment, in (a). An initial variable, “historical cleavages in society”, is depicted as a green oval in (b). A pathway begins at the micro level in (c) with “historical cleavages in society” → “organized interests”. The latter, a divergent variable, appears as an orange diamond. One important point of division in society, which continues to impact upon politics to this day, is the way in which English- and French-speaking Canadians have organized to pursue their interests from Confederation onward. A historical example would be conflict during World War II over conscription – viewed much less favorably in Québec than elsewhere in Canada (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 149).

(d) introduces another initial variable with “liberal-democratic political culture”. This aspect of Canadian identity is expected to impact upon foreign policy in various ways (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 10). One illustration would be a longstanding identification with peacekeeping, from the time of Lester B. Pearson as foreign minister onward. In recognition of his role in brokering a deal to end the Suez crisis, the future prime minister received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 64).

Two routes come together in (e). One connection is “organized interests” → “public opinion | elite opinion”. Since it is a convergent variable, “public opinion | elite opinion” appears as a blue parallelogram. Interest groups impact upon public and elite opinion, notably the media. This creates a symbiotic property for elite and public opinion that is represented in graphic form as a co-constitutive variable. Consider, for example, the clash of opinions over the Iraq War that reflected any number of influences and reverberations between the public and elites (Nossal et al., Citation2015, pp. 344–345). The other link in (e) is “liberal democratic political culture” → “public opinion | elite opinion”. The connection is an obvious one; Canadian culture shows high and sustained support for freedom of expression. Instances at the elite level would include “talking heads” on television and columnists in both newspapers and internet outlets, along with polling that provides a usually accurate sense of public opinion. All of this proceeds unimpeded, aside from rare wartime interventions by government.

(f) starts a new pathway: “historical cleavages in society” → “FEDERAL SYSTEM”. Confederation in 1867 certainly reflected the impact of divisions in society; for example, bargaining over local versus national authority took place then and continues to this day (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 182). This route continues at the macro level in (g) with “FEDERAL SYSTEM” → “INSTITUTIONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES FOR MAKING AUTHORITATIVE DECISIONS, LINES OF AUTHORITY, POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN AND BETWEEN DIFFERENT ORGANIZATIONS OF GOVERNMENT”. Consider, for example, the importance of consultative structures in the post-NAFTA era – entities within which the federal and provincial governments coordinate with each other on policy relevant to matters at home and abroad (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 333). A host of bureaucracies within the federal system also impact upon issues within Canadian foreign policy.

(h) shows a new initial variable, depicted as a green oval at the macro level: “POPULATION, WEALTH LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT, INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURE, LEVEL OF URBANIZATION, CAPACITY TO APPLY MILITARY FORCE OR COERCION, DEGREE OF MILITARY DEPENDENCE, BELIEF SYSTEM”. In brief, this refers to the national capacity to act.

Two pathways emerge in (i) from this macro level variable into the international system: “POPULATION, WEALTH LEVEL OF DEVELOPMENT, INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURE, LEVEL OF URBANIZATION, CAPACITY TO APPLY MILITARY FORCE OR COERCION, DEGREE OF MILITARY DEPENDENCE, BELIEF SYSTEM” → “MIDDLE POWER STATUS”; “DEGREE OF DIVERSIFICATION AND DEPENDENCE ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE, FINANCIAL FLOWS, TECHNOLOGY, NATURAL RESOURCES”. The first of these connections refers to Canadian status – great, middle or small – among the approximately 200 states in the international system. By consensus, Canada is a middle power; it is vast in terms of territory and natural resources, with a state-of-the-art economy, but limited in terms of population size and especially military capability.Footnote12 The second connection in (i) links basic capability to aspects of policy. Population, industrial structure and other features can be expected to impact upon the conduct of international trade, along with a relative emphasis on technology and other policy choices (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 7).

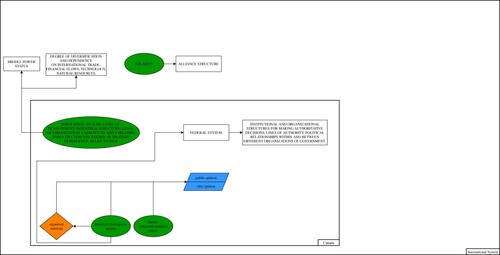

(j) introduces a new initial variable in the international system, which is depicted as a green oval: “POLARITY”. Put simply, this refers to the structure of the international system understood in terms of the number of great powers (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 6). A pathway starts at the international level in (k) with “POLARITY” → “ALLIANCE STRUCTURE”. Polarity impacts upon alignment in a very basic way (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 6). For example, Cold War bipolarity stimulated creation of opposing alliances by the US and USSR, most notably NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

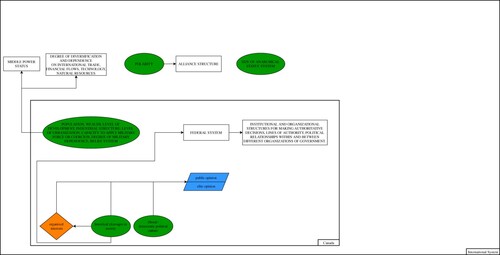

(l–n) introduce three more initial variables, depicted as green ovals in the international system: “SIZE OF ANARCHICAL STATE SYSTEM”; “NATURE AND DEGREE OF COOPERATION AND INSTITUTIONALIZATION”; “PROXIMITY TO US”. These are basic geostrategic factors that enable and constrain action by states in the international system (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 6, 7). Given its position as the longstanding system leader, location relative to the US is of special importance.

(o) starts a pathway in the international system with “PROXIMITY TO US” → “INERTIAL EFFECTS OF NATO AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION MEMBERSHIPS”. Recall the old saying about real estate: location matters. With the system-leading US as a neighbor, a certain momentum comes from membership in the same “clubs”. NATO is just the most obvious example (Nossal et al., Citation2015, p. 8).

(p) brings all of the pathways together into a single point of completion: Two connections lead out from micro and macro levels of Canada, respectively: “public opinion | elite opinion”; “INSTITUTIONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES FOR MAKING AUTHORITATIVE DECISIONS, LINES OF AUTHORITY, POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN AND BETWEEN DIFFERENT ORGANIZATIONS OF GOVERNMENT” → “CANADIAN FOREIGN POLICY”. As a terminal variable, “CANADIAN FOREIGN POLICY” takes the form of a red octagon. Finally, eight variables in the international system feed into the terminal variable: “MIDDLE POWER STATUS”; “DEGREE OF DIVERSIFICATION AND DEPENDENCE ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE, FINANCIAL FLOWS, TECHNOLOGY, NATURAL RESOURCES”; “POLARITY”; “ALLIANCE STRUCTURE”; “SIZE OF ANARCHICAL STATE SYSTEM”; “NATURE AND DEGREE OF COOPERATION AND INSTITUTIONALIZATION”; “PROXIMITY TO US”; “INERTIAL EFFECTS OF NATO AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION MEMBERSHIPS” → “CANADIAN FOREIGN POLICY”. With all of these connections in place, the final sub-figure corresponds to .

While it is beyond the scope of this exposition to present the case for a systemist graphic such as in great detail, a few basic observations are in order.

First, the graphic is able to probe for logical consistency in a way that is much more direct than through use of words alone. makes it clear that the framework of Nossal et al. (Citation2015) is free from a contradiction in its specification of cause and effect about Canadian foreign policy.

Second, the graphic conveys a relatively complete treatment in terms of levels of analysis. Canadian foreign policy emerges as a combination of many factors that span state and society in Canada, along with the international system. In that sense, the framework is closer to satisfying the requirements for completeness from systemism than alternatives that might tend to emphasize one level of analysis at the expense of others.

Third, consider the potential for the elaboration of the framework once its limitations, as well as contributions, are identified. The framework from Nossal et al. (Citation2015) currently lacks connections downward; this refers to both the absence of connections from (i) the international system into Canada; and (ii) the state into society.Footnote13 Elaboration of the network of cause and effect to include aspects (i) and (ii) would have obvious benefits, for example, to the study of domestic politics in Canada and possibly elsewhere.

Fourth, and finally, consider the fact that an alternative version of the framework might be created – something that seems by intuition like a negative rather than positive feature. In fact, this is a strength of the systemist technique. creates the foundation for what arguably could be a much more productive debate about what Nossal et al. (Citation2015) have communicated via their framework. Put differently, dialogue based on systemist graphics requires greater clarity than a discussion that instead might take place through words alone.

Contributions to the special issue

This special issue includes five substantive contributions that apply systemism to a range of subject matter, which will be complemented by essays that reflect upon accomplishments so far and future prospects in the realm of Canadian foreign policy. To be able to illustrate the versatility and multitude of applications of the systemist technique and method, each of the five substantive contributions varies in its focus and has different points of convergence and divergence. The special issue and its subject matter, therefore, serve to outline the benefits of diagrammatic exposition for the study of regime change (Mahant), treatment of different (non-state) actors (Henders), the evolution of politico-economic policy (Hale), development of a specific policy area (Warner), and in connection with foreign policy analysis (Canbolat, Gansen and James).

In the first article, “Foreign Policy of New Regimes and Their Leaders: A Systemist Exposition”, Edelgard Mahant portrays and diagrammatically analyzes the foreign policies of three different incoming regimes and how the respective leaders in each instance enunciated a new foreign policy designed to promote not only the interests of the state but also identity formation. The article focuses on three key new regimes and their central figures, namely Lenin and Russia, Adenauer and the Federal Republic of Germany, and Mandela and Mbeki in South Africa. Starting with the objectives of the former regime in each instance, Mahant outlines how the foreign policy of each new regime and the respective leader as an individual policy-maker is both a continuation and divergence thereof and which new courses of action the government can take. Systemist graphics are used to carry out systematic synthesis to see what can be learned from the three preceding studies when engaged with each other.

The second contribution is entitled “People Acting Across Borders and Canadian Foreign Policy: A Systemist Analysis”. Its common point of analysis is the understanding of mobile non-state actors linked with Canada. In this contribution, Susan J. Henders illuminates how these mobile and/or border-crossing populations have an impact on Canadian foreign policy. While the three works discussed agree on these interactions being a part of Canadian external relations, the expositions see this effect from different angles and with varying focal points. In using the technique and method of systemism, Henders juxtaposes the diverse (meta)theoretical approaches, concepts, and issues of these works to outline how all of them address different ways in which economic, social and cultural relations, as well as domestic policies, interact with their attempts to manage and instrumentalize mobile populations. In doing so, the analysis from Henders illustrates how these populations make and shape external relations linked with Canada in general and in regard to Canadian foreign policy in particular.

While Henders’ article deals with Canadian foreign policy on a more regional level and compares different authors, the third contribution, “Converging and Diverging Streams: A Systemist Analysis of How Canadian Foreign Investment Policy Adapts to Globalizing and Fragmenting World Orders”, centers on a comparison of Canada’s approach to foreign investment policies on a global level at different points in time. Building on three of his publications, Geoffrey Hale analyzes the development of Canadian foreign investment policies since the 1980s in the context of Kingdon’s model of policy streams. Through the systemist analysis of this chronological development, Hale outlines the different factors that have shaped the convergence and divergence of these policy streams and their relevance today, particularly with regard to growing geopolitical tensions between China and the United States.

The fourth article analyses Canadian policy- and decision-making in yet another area, which once more highlights the versatility of a systemist approach. Systemism can be used regardless of the topic discussed, methods used, or approach taken in the respective piece that is being visualized. The contribution from Rosalind Warner, “A Systemist Depiction of Canadian Disaster Risk Reduction and Assistance 2011–2019”, provides a clear visual representation of the cause and effect relationships, trends, and logical impacts of different pieces in the field of Canadian disaster risk reduction and the corresponding policy decisions on assistance. In doing so, Warner highlights areas of crossover as well as fruitful directions for future learning to further develop and improve the decision-making process and Canada’s efforts to reduce the risks of disasters.

Fifth among the substantive contributions, from Canbolat, Gansen and James, is “Systemism, Foreign Policy Analysis and Political Forecasting: An Exercise in Systematic Synthesis”. Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA) is a highly active area within the social sciences. The purpose of this article is to put studies from FPA in contact with each other via a graphic method, systemism, to obtain insights that otherwise might prove elusive. Completion of that task is anticipated to yield both academic and policy-related value.

Finally, four contributions – from (1) Andrea Lane; (2) Kim Richard Nossal, Stéphane Roussel and Stéphane Paquin; (3) Kari Roberts and (4) Heather Smith – reflect upon what has been accomplished, on an individual and collective basis, by the preceding applications of systemism. This is followed by a brief summation from Gansen and James that focuses on what has been learned from the substantive articles in tandem with the commentaries upon them. Answers to overarching questions are pursued: What more is known about specific topics in foreign policy and international relations as a result of implementing systemist diagrams? Is a turn toward systemist graphics the way forward for a more effective study of Canadian foreign policy in particular and IR in general? How might a systemist graphic approach support government decision-making about foreign policy? These and other associated questions will be answered, at least tentatively, in this final contribution to the special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Gansen

Sarah Gansen is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California and a graduate of USC Gould School of Law.

Patrick James

Patrick James is the Dana and David Dornsife Professor of International Relations at the University of Southern California.

Notes

1 As is standard within the field, “International Relations” refers to the academic discipline and “international relations” to its subject matter.

2 Much more detailed introductions to systemism and its potential value to communication are available in James (Citation2019a, Citation2019b), Pfonner and James (Citation2020) and Gansen and James (Citation2021).

3 The diagrammatic exposition that follows is based primarily upon James (Citation2019a).

4 Beyond the scope of the present exposition is specification of functional form for proposed connections; this is required by systemism to completely articulate a theory (Bunge, Citation1996). While incremental change is assumed as the default position, it is important to recognize that functional relationships can be non-linear as well.

5 For a review of applications spanning many disciplines to subjects within international relations and foreign policy in general, see Yetiv and James (Citation2017).

6 If an author is deceased, former students can be consulted on the content and meaning of publications; if that option is not available, experts on the work of a given scholar can be contacted instead. For a more detailed exposition on creation of systemist figures, see Gansen and James (Citation2021).

7 Onuf (Citation1989) is one point of entry for bricolage as a concept within IR.

8 Gansen and James (Citation2021) cover these principles in detail. One example is that work should start with a pencil sketch that identifies the system and its macro and micro levels, along with the environment.

9 In a critique that is beyond the scope of the present exposition, Bow (Citation2014) takes issue with how approaches have been coded in Boucher (Citation2014).

10 Previous editions, authored exclusively by Kim Richard Nossal, appeared from 1987 onward.

11 The exposition that follows is based primarily on the overview of the framework in Nossal et al. (Citation2015, pp. 1–18).

12 Nossal et al. (Citation2015, p. 20) are careful to point out that designation of middle power status only begins to give a sense of potential efficacy for Canadian foreign policy; their emphasis goes beyond capability itself and extends into how tools of foreign policy are used.

13 Introduced in Gourevitch (Citation1978), the point of departure for analysis of system-level impact on state and society is the concept of the “second image reversed”. This refers to a reversal of the standard second image from Waltz (Citation1959), which focused on the impact of developments within the state on the international system.

References

- Boucher, J.-C. (2014). Yearning for a progressive research program in Canadian foreign policy. International Journal, 69, 213–228.

- Bow, B. (2014). Measuring Canadian foreign policy. International Journal, 69, 229–232.

- Bunge, M. (1996). Finding philosophy in social science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Gansen, S., & James, P. (2021). Systems analysis: Systemism and the visual international relations project. In R. Joseph Huddleston, T. Jamieson, & P. James (Eds.), Handbook of methods for international relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, forthcoming.

- Gecelovsky, P., & Kukucha, C. J. (2008). Canadian foreign policy: A progressive or stagnating field of study? Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 14, 109–119.

- Gourevitch, P. (1978). The second image reversed: The international sources of domestic politics. International Organization, 32, 881–912.

- James, P. (2019a). Systemist international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 63, 781–804.

- James, P. (2019b). What Do We know about crisis, escalation and War? A visual assessment of the international crisis behavior project. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 36, 3–19.

- Nossal, K. R., Roussel, S., & Paquin, S. (2015). The politics of Canadian foreign policy. Queen’s policy studies series (4th ed.). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Onuf, N. G. (1989). World of Our making: Rules and rule in social theory and international relations. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9, 105–119.

- Pfonner, M. R., & James, P. (2020). The visual international relations project. International Studies Review, 22, 192–213.

- Tufte, E. R. (2006). Beautiful evidence. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press LLC.

- Waltz, K. N. (1959). Man, the state, and war: A theoretical analysis. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Yetiv, S. A., & James, P. (Eds.). (2017). Advancing interdisciplinary approaches to international relations. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.