ABSTRACT

Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA) is a highly active area within the social sciences, intersecting with the study of International Relations in any number of ways. The purpose of this article is to put studies from FPA in contact with each other via a graphic method, systemism, to obtain insights that otherwise might prove elusive. Completion of this task is anticipated to yield both academic and policy-related value. This study will unfold in six sections. Section one provides an overview of the project. Systemist graphics are used in sections two through four to convey arguments for three studies from FPA that focus on leadership and decision-making in multiple locations. Section five engages in systematic synthesis based on those works. The sixth and final section sums up the contributions of this article and passes along a few thoughts about future research.

RÉSUMÉ

L'analyse de la politique étrangère (APE) est un domaine très actif des sciences sociales qui recoupe l'étude des Relations Internationales de nombreuses façons. L'objectif de cet article est de rapprocher des études de l'APE les unes des autres par le biais d'une méthode graphique, le systémisme, afin d'obtenir des perspectives qui pourraient autrement s'avérer insaisissables. L'accomplissement de cette tâche devrait avoir une valeur à la fois académique et politique. Cette étude se déroulera en six sections. La première section offre un aperçu du projet. Des graphiques systémistes sont utilisés dans les sections deux à quatre pour transmettre des arguments en faveur de trois études d'APE qui se concentrent sur le leadership et la prise de décision dans plusieurs endroits. La cinquième section se livre à une synthèse systématique sur la base de ces travaux. La sixième et dernière section résume les contributions de cet article et émet quelques réflexions sur les recherches futures.

Overview

Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA) is a vibrant research area within the social sciences. It also intersects with the study of International Relations (IR) as a discipline in multiple ways. At the same time, many FPA-style studies focusing on different research questions and case studies show limited contact with each other.Footnote1 This is an observation that can be made about areas of research within many academic fields. Increasingly silo-like programs of research constitute an observable trend within IR a century into its existence (James, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Pfonner & James, Citation2020). The purpose of this article is to put studies from FPA in contact with each other via a graphic method, systemism, to obtain insights that might otherwise prove elusive. Completion of these tasks is anticipated to yield both academic and policy-related value.

Based on the systemist approach, three scholarly works subscribing to FPA tradition will be converted to graphic form and engaged with each other. These studies are “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership: An Operational Code Approach” (Özdamar & Canbolat, Citation2018), Leaders in Conflict: Bush and Rumsfeld in Iraq (Dyson, Citation2014), and US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes (Walker & Malici, Citation2011). The purpose of the analysis in this article is to illustrate that the systemist diagrammatic exposition of theoretical arguments can be employed to compare, discuss, and put works in contact with each other productively.

A graphic method enables researchers to justify their case selection on the basis of stratified sampling and thematic variety. We chose these three specific FPA-style works for systematic synthesis because they exemplify a range of diverse topics such as new leadership profiles in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), wartime decision-making in the second Bush Administration, and a theoretical account of foreign policy mistakes evidenced by a sample of American presidents. While these three studies are informed by cognate methodological advances in the FPA field, they also differ from each other on the basis of their theoretical underpinnings. Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018) employ operational code analysis based on leaders’ political statements whereas Dyson (Citation2014) and Walker and Malici (Citation2011) utilize hybrid theoretical frameworks combining diverse leadership and decision-making assessment tools such as the Leadership Trait Analysis (LTA), management style analysis, and formal modeling.

All three works visualized here have appeared in significant academic outlets, yet it is unlikely that any prior study has included this full set in its bibliography. Respective figures for these studies will be presented in total and then by installments through alphabetized subfigures. Each subfigure is fleshed out by interpretive text to offer further explanation of its respective linkages. While the connections between and among the variables and the underlying logic of certain graphics are virtually self-evident in some cases – like and its subfigures – more complex visuals, such as and , are accompanied by further commentary to articulate the causal linkages.Footnote2

Figure 1. “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership: An Operational Code Approach” (Özdamar & Canbolat, Citation2018).

Figure 2. Leaders in Conflict: Bush and Rumsfeld in Iraq (Dyson, Citation2014).

Figure 3. U.S. Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes (Walker & Malici, Citation2011).

Establishing links between and among these studies via systematic synthesis, an activity encouraged within Systemist International Relations (SIR), represent further added-value from the present article.Footnote3 The function of systematic synthesis is to identify points of agreement among a set of studies that share subject matter (James & James, Citation2017, p. 289). For example, the degree of consensus about why some crises escalate to war, while others do not, has been investigated on the basis of 14-data based studies from the International Crisis Behavior Project (James, Citation2019a). The basic approach is to take systemist graphics of individual studies and use them in combination to identify patterns that otherwise might not be detected.

This study will unfold in five further sections. Systemist graphics are used in sections two through four to convey arguments for the three studies from FPA that focus on leadership and decision-making in the US and the MENA. Section five engages in systematic synthesis based on those works. The sixth and final section sums up the contributions of this article and passes along a few thoughts about future research.

FPA and leadership in the Middle East

Individual leaders play a crucial role in politics and foreign policy in the MENA. Specifically, the Arab MENA stands out as one of the few regions in the world characterized by powerful and charismatic political leaders (Canbolat, Citation2014; Dekmejian, Citation1975). There is, however, a dearth of systematic, FPA-based treatments of MENA leadership (for a few exceptions see Canbolat, Citation2020a, Citation2021; Çuhadar, Kaarbo, Kesgin, & Ozkececi-Taner, Citation2017; Kesgin, Citation2013; Malici & Buckner, Citation2008; Özdamar, Citation2017; Özdamar & Canbolat, Citation2018). Hinnebusch (Citation2015, p. 84) stresses the dominance of a rational choice model in actor-specific studies at the expense of psychological approaches to leadership analysis in the region. MENA leadership studies also have grappled with the problem that, until very recently, an automated at-a-distance analysis of key decision-makers’ verbal statements to create leadership profiles has remained largely confined to English-language texts (see Brummer et al., Citation2020; Canbolat, Citation2020b; Özdamar et al., Citation2020). In that context, “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership” is among a relatively small but expanding number of theory- and data-driven studies on the subject of the resurgent political Islamist ideology and its foreign policy propensities in the era after the Arab uprisings early in the new millennium (Özdamar & Canbolat, Citation2018).

Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018) focus on political leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), which generally is viewed as the world’s largest and most influential Islamist organization. Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018, p. 19) assess the MB at-a-distance by comparing Mohamed Morsi of Egypt, Rachid Ghannouchi of Tunisia, and Khaled Meshaal of Gaza as examples of Islamist leaders to expound their political beliefs and assess their foreign policy propensities. Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018) use the operational code approach, implemented through a content-analysis software and statistical test, to profile the MB’s political leaders and account for their foreign policy decision-making. The three leaders’ foreign policy beliefs, Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018, p. 23) discover, approximate averages of world leaders across basic dimensions. It also turns out that master operational code beliefs of MB leaders are similar to each other. In an operational code research program, there are three master beliefs shaping a leader’s operational code (i.e. P-1, I-1, and P-4 beliefs).Footnote4

illustrates cause and effect from “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership” in visual form.Footnote5 A collection of subfigures, (a–g), depicts the connections of either one or a few at a time to facilitate comprehension. ( and unfold in the same way.) All of the figures emulate , which displayed the systemist notation at the outset of this special issue (Gansen and James, this volume) and is included here again for purposes of lucidity and ease of comprehension.

Table 1. Systemist Notation.

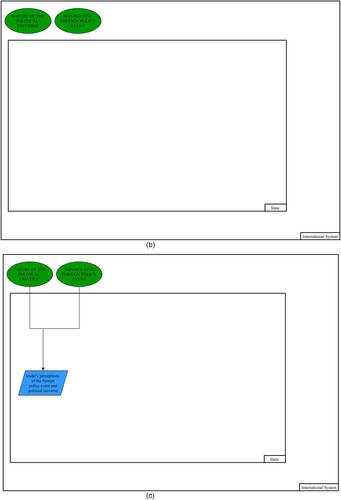

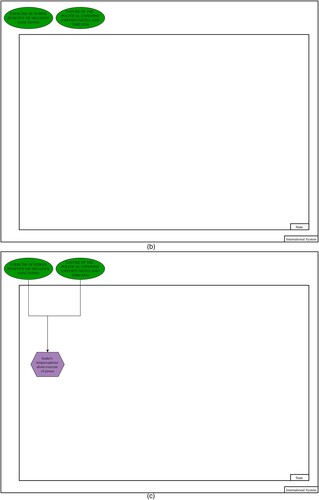

(a) exhibits the international system as the environment that subsumes the state as its system. Within the state, respectively, the micro and macro levels correspond to leadership and decisions produced by it.

(b) shows two variables in the international system, “NATURE OF THE POLITICAL UNIVERSE” and “NON-ROUTINE FOREIGN POLICY EVENT”, as green ovals, i.e. initial variables, which spark off a series of relationships. As mentioned in the introductory article of this issue, the functions of variables are best understood using a river as an analogy. In that sense, an initial variable, that is colored in green as it serves as the “green light” to start a chain of causal linkages, is analogous to the source of a river.

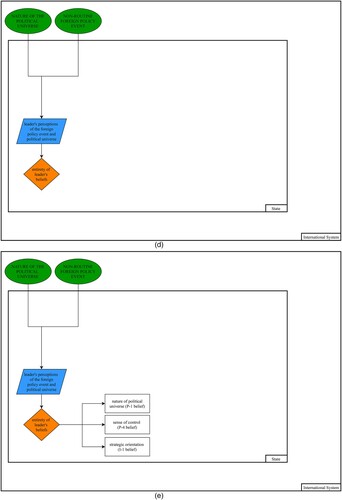

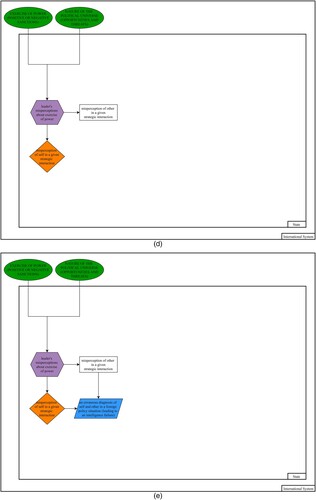

(c) depicts a connection from the international system to the micro level of the state via an explicit macro–micro linkage: “NATURE OF THE POLITICAL UNIVERSE”; “NON-ROUTINE FOREIGN POLICY EVENT”→“leader’s perceptions of the foreign policy event and political universe”.Footnote6 As a convergent variable, the latter appears in the form of a blue parallelogram creating a single pathway from multiple inputs – like several streams coming together into one river. The ensuing micro level route seen in (d) leads from the convergent variable into “entirety of leader’s beliefs”, a divergent variable that is depicted as an orange diamond. Directly opposed to a convergent variable, a divergent variable’s function is the creation of multiple pathways from a single linkage, i.e. it only has one input but multiple outputs – analogous to a river separating into several streams. Applied in this context, political beliefs of leaders include their philosophical and instrumental positions. While the former explains how leaders perceive not only their own but also other power relationships in the political universe, the latter provides cues about the strategic orientation and tactical preferences about attaining political objectives (Schafer & Walker, Citation2006, p. 4).

(e) continues on with a micro level coupling and makes a transition from a leader’s entirety of beliefs to their “master beliefs”. Multiple pathways from “entirety of leader’s beliefs” go through three generic variables. Generic variables serve to represent a linear step in the process as they have exactly one input and one output. Envisioned in the riparian context, a generic variable represents the river flowing forward in one stream without any points of contingency. In the present diagram, the generic variables are “nature of political universe (P-1 belief)”; “sense of control (P-4 belief)”; “strategic orientation (I-1 belief)”. According to Schafer and Walker (Citation2006, p. 12), leaders have many disparate political positions, but the collection can be boiled down to three master beliefs for the sake of parsimony and analytical rigor.

Considered together, these three master beliefs constitute a decision-maker’s operational code profile and leadership type through multiple linkages, as depicted in (f): the three generic micro variables connect to “leader’s operational code (leadership type)”, a nodal variable that appears as a purple hexagon. As it both brings together multiple linkages and then serves as a point of divergence, i.e. creating multiple pathways, a nodal variable has numerous inputs and outputs. These three operational code beliefs are the main determinants of the leadership typology, which has been utilized in the operational code analysis and role theory research programs since the seminal work of Holsti (Citation1977). These three generic variables, therefore, are inextricably linked to the leader’s operational code, from which multiple pathways ensue.

Finally, (g) displays two micro–macro linkages: “leader’s operational code”→“LEADER’S FOREIGN POLICY DECISION-MAKING” and “FOREIGN POLICY DECISION OUTCOMES”. This diagram extends the micro–macro level pathways to the point of termination. The first coupling transpires within the system (state) as it connects a micro level variable (leader’s operational code) with a macro level one (LEADER’S FOREIGN POLICY DECISION-MAKING) that is executed domestically, i.e. the decision-making occurs within the state as the system. The second pathway links a leader’s operational code (micro level variable) within the state to “FOREIGN POLICY DECISION OUTCOMES” (macro level variable), which resides in the international system. The two-terminal variables are depicted as red octagons, visually equivalent to stop signs, and thus constitute the end of the story about cause and effect. Since a terminal variable serves as the endpoint of a series of relationships, it has one or more inputs but no outputs. Using the analogy of the river once more, a terminal variable is identical to the river’s mouth.

Overall, as can be seen in ((g), the last of the sub-figures), the nodal variable “leader’s operational code (leadership type)” is at the heart of things. Translated to the context of a river, its importance also becomes evident as it serves to join multiple streams together, only to break them apart again in novel ways. Here, the operational code is the product of different linkages, i.e. the three master beliefs that are central to the analysis of Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018), and also creates the terminal variable outputs – “LEADER’S FOREIGN POLICY DECISION-MAKING” and “FOREIGN POLICY DECISION OUTCOMES” – that are filled with meaning based on the beliefs, choices, and decisions of an individual leader.

FPA and Leaders in wartime

Leaders in Conflict (Dyson, Citation2014) is a foundational study of behavioral FPA in general and political psychology of elite decision-making in particular. It makes the case that “leadership matters” in both foreign policy processes and outcomes. Moreover, the study challenges structural approaches for their lack of actor-specific lenses (Hudson, Citation2005). Dyson (Citation2014, pp. 4–5) shows that each leadership style/worldview has its own upsides and downsides. Unlike certain prior studies of political leadership, Leaders in Conflict is not a story of pathological and irrational personalities. The book is an extension of the “leadership is multifaceted” argument in FPA; Dyson (Citation2014, p. 5) asserts that (i) leadership contains both internal (management style) and external (worldview) elements and (ii) one does not determine the other. The volume features more than two dozen interviews with Bush 43 Administration officials and comprehensive speech data to construct leadership profiles of Bush and Secretary of Defense, Donald H. Rumsfeld, in the course of the Iraq War.

Bush and Rumsfeld, Dyson (Citation2014) argues, thought about and acted upon leadership in different ways. Research reveals the impact of idiosyncratic points of divergence over the course of the Iraq War. While Rumsfeld was prepared to terminate the US military presence in Iraq by turning things over to the Iraqis right at the end of conventional warfare in the spring of 2003, Bush favored continued involvement. The president thereby risked paying a high cost in American treasure, prestige, and lives to declare a military and political victory (Dyson, Citation2014, p. 125).

However, as Dyson (Citation2014, p. 1) notes, Bush brought US policy and war strategy fully into line with his personal goals only after he fired Rumsfeld in 2006. With his decision to dispatch additional troops to Iraq, the president flexed American military muscle and brushed aside the Rumsfeld-led approach that favored limited deployment and rapid withdrawal. This shift in policy came at the expense of Iraq’s disintegration as the occupation force proved unable to maintain order.

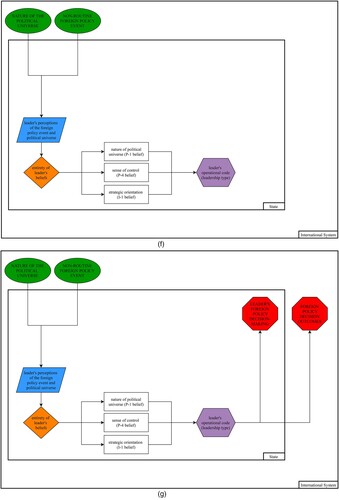

displays the arguments of Leaders in Conflict from a bird’s eye view.Footnote7 (a) designates (i) the state as the system and (ii) the international system as its environment. The micro and macro levels in the state correspond, respectively, to perceptions of leaders and resulting policies. (b) depicts an initial variable, “FOREIGN POLICY CRISIS”, as a green oval in the international system. A crisis situation is construed as a “key foreign policy episode” that must be resolved in some way (Dyson, Citation2014, p. 4). Such events, in the context of the Iraq War, include the emergence of the Bush doctrine, Coalition Provisional Authority, and divergent exit strategies of Rumsfeld and Bush.

(c) displays a macro–micro level linkage crossing over from “FOREIGN POLICY CRISIS” in the international system to the micro level of the system and leading into “leader’s perceptions of foreign policy crisis”. Located at the micro level, this variable concerns the perceptions of the respective leader in question, e.g. Bush with regard to the Iraq War. (d) continues on with a micro-micro level linkage: “leader’s perceptions of foreign policy crisis”→“leader’s response to the crisis (war response)”. This coupling concerns the well-established causal relationship between leadership political psychology and policy deliberation and choice. The latter is a divergent variable and appears as an orange diamond. (e) expands on the micro level connections, bifurcating the internal and external elements of political leadership, and creates two links: “leader’s response to the crisis (war response)”→“leader’s worldview”; “leader’s management style”. As a divergent variable, each of the latter two, therefore, is depicted as an orange diamond.

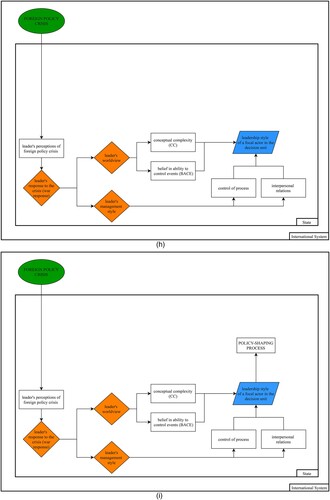

(f) focuses on two micro-micro level linkages: “leader’s worldview”→“conceptual complexity (CC)”; “belief in ability to control events (BACE)”. Dyson (Citation2014) draws CC and BACE variables from the Leadership Trait Analysis research program (Hermann, Citation1980, Citation2005) that, respectively, measure the complexity of thinking about political events and how much control/power a leader can attribute to Self as opposed to Other. In (g), the lower orange diamond, “leader’s management style”, extends into its core elements – “control of process” and “interpersonal relations”. These components of management style are introduced from the literature on elite political decision-making (Dyson, Citation2014, p. 12; for the origins of these concepts, see Johnson, Citation1974; George, Citation1980).

(h) displays the intersection for all of the prior micro pathways. The four generic variables meet together at “leadership style of a focal actor in the decision unit”. As a convergent variable, this appears as a blue parallelogram. Thus, the study brings together aspects of the literature on leadership traits and political psychology of elite decision-making to obtain a more complete picture of leadership profiles for Bush and Rumsfeld. Dyson (Citation2014, p. 12) argues that worldviews and management styles can be traced to pivotal decision points and makes a case for counterfactuals: “other individuals would have acted differently” throughout the key episodes of the Iraq War.

(i) introduces a micro–macro linkage: “leadership style of a focal actor in the decision unit”→“POLICY-SHAPING PROCESS”. This connection concerns the indispensability of the political actor and stresses how leaders’ beliefs and styles can impact differently from each other on processes. (j) continues on with a macro level coupling: “POLICY-SHAPING PROCESS”→“POLICY CHOICE”. According to Dyson (Citation2014, pp. 125–126), Bush pursued his own foreign policy strategy when he removed Rumsfeld from office in late 2006.

(k) completes the story of cause and effect: “POLICY CHOICE”→“CRISIS DECISION OUTCOME”. As a terminal variable, the latter is depicted as a red octagon.

Overall, Leaders in Conflict leverages its actor-specific lenses with decision units and FPA-related insights to evade the trap of either the individualistic fallacy or an all-out reductionist approach. The most significant connections are the divergent variables: “leader’s worldview” (broken down into Conceptual Complexity and BACE) and “leader’s management style” (control of process and interpersonal relations). Taken together, these traits can account for the “leadership style of a focal actor in the decision unit”. Following these essential micro-micro linkages, there is a shift from micro level leadership variables to macro level variables, “POLICY-SHAPING PROCESS” and “POLICY CHOICE”, which impact upon the terminal variable, “CRISIS DECISION OUTCOME”, within the environment as opposed to the state as the system.

FPA, US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes

Memorable for its critical examination of US foreign policy, US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes focus on leadership errors in the exercise of power. According to Walker and Malici (Citation2011, p. 5), fundamental questions in FPA need to be addressed: “What are foreign policy mistakes? How and why do they occur? What can be done to avoid them?” Distilling insights from past scholarship on elite decision-making, and US foreign policy, Walker and Malici (Citation2011) argue that foreign policy errors fall broadly into two general categories of commission and omission concerning the nature of the political universe, which are manifested either as threats or opportunities.Footnote8

Walker and Malici (Citation2011, p. 13) note that each kind of mistake may occur at the levels of “diagnosing a foreign policy situation or prescribing a foreign policy response,” while a third possibility is that an error can happen at both stages of the decision-making process. US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes cautions that what is missing from the FPA literature in general and the study of US foreign policy, in particular, is an explanation for why mistakes occur. They (Citation2011, pp. 13–14) therefore examine in more detail the processes of diagnosis and prescription in making or avoiding foreign policy mistakes.

Walker and Malici (Citation2011) propose a novel theory of foreign policy mistakes. The main thrust of the theory is its underlying typology of mistakes along two dimensions: failures of analysis and of prescription and the mistakes of omission and commission. The rigorous typology and formal models then are complemented by quite rich empirical data gleaned from the history of foreign relations when US presidents either did too much too soon or too little and too late (Walker & Malici, Citation2011, pp. 11–12). The well-known foreign policy mistakes that the book covers include President Woodrow Wilson’s refusal to compromise on the Versailles Treaty and President John Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs invasion. Owing to the application of this novel typology and illustrating each type of mistake with a series of consequential cases, US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes is an important contribution to both the literature on decision-making and about American foreign policy.

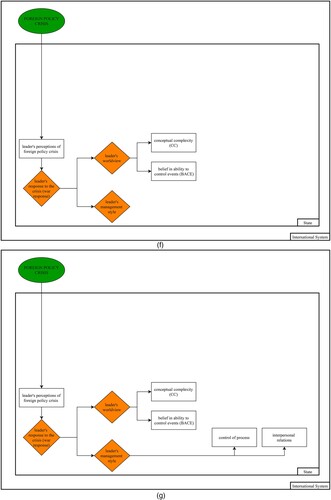

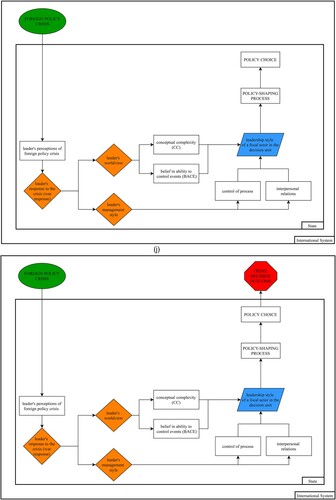

conveys the main arguments from Walker and Malici (Citation2011).Footnote9 Depicted in (a), the state serves as the system, while the international system is its environment. The micro and macro levels within the state as a system correspond, respectively, to (i) political elite decision-making and (ii) foreign policy outcome. (b) displays two initial variables, located in the environment and depicted as green ovals: “EXERCISE OF POWER (POSITIVE OR NEGATIVE SANCTIONS)” and “NATURE OF THE POLITICAL UNIVERSE (OPPORTUNITIES AND THREATS)”.

(c) gets underway with a pair of macro–micro linkages: “EXERCISE OF POWER (POSITIVE OR NEGATIVE SANCTIONS)”; “NATURE OF THE POLITICAL UNIVERSE (OPPORTUNITIES AND THREATS)”→“leader’s misperceptions about exercise of power”. As a nodal variable, the latter appears as a purple hexagon. In (d), linkages from this variable lead to two more micro level variables: “misperception of other in a given strategic interaction” and “misperception of self in a given strategic interaction”. While the former pathway points toward a generic variable, the latter extends into a divergent variable that is depicted as an orange diamond.

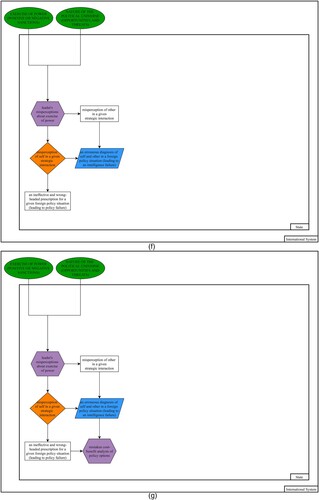

(e) connects the two variables just mentioned with another micro level variable: “an erroneous diagnosis of self and other in a foreign policy situation (leading to an intelligence failure)”. As a convergent variable, it is depicted with a blue parallelogram. (f) follows on with another micro level connection: “misperception of self in a given strategic interaction”→“an ineffective and wrong-headed prescription for a given foreign policy situation (leading to policy failure)”.

(g) extends the micro level routes to an intersection: “an ineffective and wrong-headed prescription for a given foreign policy situation (leading to policy failure)”; “an erroneous diagnosis of self and other in a foreign policy situation (leading to an intelligence failure)”→“mistaken cost–benefit analysis of policy options”. Via this nodal variable connection, Walker and Malici (Citation2011) delve into the anatomy of foreign policy mistakes by dissecting diagnostic and prescriptive reasons for such developments.

(h) conveys two micro-micro extensions from the nodal variable: “mistaken cost–benefit analysis of policy options”→“omission-based mistakes (doing too little or too late) associated with pragmatic political leaders”; “commission-based mistakes (doing too much or too soon) associated with dogmatic political leaders”. Both of these variables are divergent and therefore depicted in form of an orange diamond. Walker and Malici (Citation2011, p. 11) contend that “decision makers can engage in mistakes of omission or commission regarding an opportunity or a threat.” While the former is a cooperative situation in which gains are likely, the latter is a conflict-prone setting in which losses become probable (Herrmann, Citation1988; Lebow & Stein, Citation1987).

Extended in (i,j) are two new micro pathways. The first divergent variable “omission-based mistakes (doing too little or too late) associated with pragmatic political leaders” leads into two generic variables: “deterrence failure in foreign policy decision-making” and “reassurance failure in foreign policy decision-making” in (i,j) complements that by unveiling two additional micro level pathways. The second divergent variable, “commission-based mistakes (doing too much or too soon) associated with dogmatic political leaders”, leads into two additional micro level generic variables: “false alarm failure in foreign policy decision-making” and “false hope failure in foreign policy decision-making”.

These respective pathways come together at a point of termination in (k). The route from each of the four generic variables leads into “FOREIGN POLICY MISTAKES”, the terminal variable, which therefore is depicted as a red octagon.

What about the overall character of the model from Walker and Malici (Citation2011) as conveyed in . The work exhibits all the hallmarks of behavioral IR and actor-specific foreign policy scholarship because it positions the concept of power and leader’s (mis)perception of the nature of the political universe at the forefront of the analysis. As noted on page 11, “decision makers can engage in mistakes of omission or commission regarding an opportunity or a threat.” Informed by Figure 1.2 in US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes (Citation2011, p. 12), they suggest a revised typology of mistakes based on types of situations and types of foreign policy consequences. Walker and Malici (Citation2011, p. 11) distinguish threat-related situations from opportunity-related situations on the basis that while “For threat situations there are deterrence failures and false alarm failures … For opportunity situations there are reassurance failures and false hope failures.” Thus, building on Walker and Malici’s (Citation2011) typology of mistakes, conveys that micro level variables of deterrence and false alarm failures concern the macro level THREAT situations, while the other micro variables, reassurance and false hope failures, are linked to the NATURE OF THE POLITICAL UNIVERSE option, that is, OPPORTUNITY situations.

Systematic synthesis

Systematic synthesis focuses on the logic of confirmation. Taken together, what are the common traits and points of consensus among a set of studies with the same approximate subject matter and intellectual tradition? Intuition suggests that such questions can be answered most effectively through the implementation of systemist graphics. The visual shift in presentation enhances the ability to grasp and retain the material and, in turn, exchange views constructively about it.Footnote10

offers a profile of the three preceding studies from FPA.Footnote11 These studies incorporate from ten to 15 variables. The range for initial and terminal variables is one or two in each instance. With regard to contingency, consider the number of divergent, convergent, and nodal variables. The studies from FPA include a range of three to six such contingent variables. The distribution of variables across the macro and micro levels of the system, along with the environment, is revealing. The range is one or two for the macro level, from six to twelve for the micro level, and precisely two each in the international system. Thus, one common trait is a relative emphasis on micro rather than macro level interactions. This common trait comports with one of the case selection criteria that we use in this study: stratified sampling. The extant emphasis on micro level interactions notwithstanding, the three FPA-style studies focus on diverse research topics informed by empirically and geographically different case studies. We observe that our selection of these three specific studies from FPA is also consonant with thematic variety.

Table 2. Profiling the studies.

depict the initial macro situation of the environment (as green initial variables) as well as the end result of the individual leader’s decision-making process for foreign policy. The diagrammatic exposition will be used to identify points of consensus.

First, collectively speaking, the diagrams highlight the impact of an individual leader’s decision-making on events and processes on the global stage (see also Jervis, Citation1976–2017). While Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018) focus on the master beliefs of a leader, which resulted in a specific operational code, Dyson’s (Citation2014) terminology centers on a leader’s worldview and management style that then determines leadership style and policy choices. Echoing the first two works, US Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes prioritizes leader’s perceptions and misperceptions of the material world and of the exercise of power in particular. Parallel to the variables designating the leader’s perceptions in those two pieces, the “leader’s misperceptions about exercise of power” is a nodal variable within the state. Note the primacy of state as the system compared to the international system as its environment. This commonality among the three FPA-style studies comports with an admonition from Hudson and Vore (Citation1995, p. 211) about “unpacking the black box of foreign policy decision-making to add much detail to the analysis of IR.” Taken together, the three FPA studies serve as a reminder not to neglect agency in favor of a structural account for what is observed in world politics.

Second among points of engagement is a salient emphasis on non-routine foreign policy events, which might provide individual leaders with more leeway in shaping foreign policy decision-making processes and outcomes. These non-routine foreign policy events include foreign policy crisis, escalation, variegated brinkmanship strategies, and war (James, Citation2019a). While Dyson (Citation2014) couched such foreign policy events in the notion of “key foreign policy episodes,” Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018) as well as Walker and Malici (Citation2011) use operational code terminology of “nature of political universe” colored by threats and/or opportunities. This common trait of the FPA-style studies can be traced back to the “fire analogy” established and popularized by Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Jervis, Citation1976–2017). In his seminal work, Jervis (Citation1976–2017, p. 20) makes a case for the indispensability of a leader and the importance of decision-making analysis when states are faced by extreme danger as leaders will head for the exits when they see that “the house is on fire.”

Third, the three studies from FPA also employ both the concepts of rationality and power, as well as the concepts of motivations, personality traits, and beliefs. Thus, it might be argued that the third point of consensus among the three works is a concerted effort to develop a mesoscopic (mid-range) theory of IR bridging microscopic and macroscopic levels. Walker and his colleagues (Citation2011, p. 7) attribute such scholarly efforts to the neobehavioral movement in IR. In that sense, these three FPA-style studies move beyond the traditional behavioral IR vs. behavioral FPA dichotomy as the three works from FPA can be identified as cognitivist, realist, and rationalist simultaneously. By incorporating realist, rationalist, and cognitivist variables in mesoscopic frameworks, the neobehavioral movement in IR overcomes the intellectual standoff between older and traditionally regarded as rival or disparate iterations of behaviorism.

Fourth, the studies from FPA facilitate comparison with rational choice, notably game-theoretic models, via case material. Why, and how much, do leaders deviate from the equilibrium path as identified as corresponding to rational decision-making? The concepts from the FPA-based studies are complementary rather than contradictory when attention turns to taking up that question. In summary form, it might be said that the mistaken cost–benefit analysis described by Walker and Malici (Citation2011) is a function of the operational code of one or more actors coming into play (Dyson, Citation2014; Özdamar & Canbolat, Citation2018).

Fifth, and finally, consider once again the missing macro-to-micro connection for all of the studies under review, revealed via the sequence of systemist graphics. This common trait recalls to mind the exposition of Gourevitch (Citation1978), which encouraged a focus on the potential impact of the international system (and by implication, its respective regions) on what goes on within states. The idea of the “second image reversed” (Gourevitch, Citation1978), in effect, encourages the extension of the research included in the three studies at hand. Put simply, how do events in the region reverberate back into its constituent states? Systemist graphic expositions have combined to evoke this interesting question and possibly identify a more general gap in what FPA models have offered to date.

Summing up and looking forward

With a rapidly expanding range of academic studies in IR, a significant challenge arises in maintaining communication between and among areas of research. With increasing specialization, subsets of scholars become prone to enter, figuratively speaking, into silos and eventually fall out of touch with each other. This study contributes to the building literature on SIR, which uses a graphic approach to facilitate communication throughout the discipline. The systemist method and technique is thus intended to counteract current research trends that could jeopardize and ultimately undermine interdisciplinarity and fruitful communication, notably the exchange of ideas between and among different research traditions and disciplines and their potential to learn from each other.

This potential becomes evident from the present article: Three FPA-based studies have been converted to systemist graphics. There is inherent value in such an exercise because it makes the story about cause and effect more explicit and thereby facilitates both comprehension and debate. In addition, implementation of systematic synthesis for the three studies contributes to the logic of confirmation.

Future research could, in a first step, further illuminate and analyze these interaction effects. Such activity would emphasize even more than systematic synthesis not only reinforces but also enlarges the insights gained from one individual scholarly work by putting it into contact with related pieces. Second, as this article exemplifies, FPA is an evergreen research area in the social sciences. Future studies therefore could shed light on potential intersections including crisis decision-making, profiling foreign leaders whose behavior deviates from expectations, and predicting the size of political coalitions and the distribution of public and private goods. In a third step, this then could lead research to become, at the same time, more interdisciplinary and comprehensive. In sum, SIR stimulates a much more transparent exchange of ideas, constructive communication, and productive discussion – an agenda that can help those in different areas of research to stay in touch with each other.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sercan Canbolat

Sercan Canbolat is a Fulbright Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at the University of Connecticut (UConn) and an incoming Visiting Assistant Professor at UConn—Stamford's Department of Political Science. Sercan is also a non—resident Fellow at the Centre in Modern Turkish Studies at Norman Paterson School of International Affairs (NPSIA) at Carleton University.

Sarah Gansen

Sarah Gansen is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California and a graduate of USC Gould School of Law.

Patrick James

Patrick James is the Dana and David Dornsife Professor of International Relations at the University of Southern California.

Notes

1 See, for instance, the review essay from Hudson (Citation2005).

2 These systemist diagrams, even if conveying relatively intricate arguments, remain in compliance with the admonition from Tufte (Citation2006) about “hyperactive optical clutter”. In other words, a basic principle for such diagrams is that each one should facilitate rather than hinder comprehension of the story presented about cause and effect in the source material.

3 It is beyond the scope of the present exposition to offer a more extensive treatment of SIR, within which various graphic-oriented methods reside. See James (Citation2019b) for a comprehensive introduction to SIR.

4 Nature of the Political Universe (P-1 belief) is a measure of the hostility or friendliness the actor sees in the political environment. Lower scores indicate more hostile worldviews. Approach to Goals (I-1 belief) is the counterpart to Nature of the Political Universe – how conflictual or cooperative does the actor present themselves as being. The Perception of Control (P-4 belief) variable evaluates the perceived degree of control of the actor over their political environment. For more information on the P-1, I-1, and P-4 beliefs and the specific formula for each variable, see Walker, Schafer, and Young (Citation1988).

5 is based upon Özdamar and Canbolat (Citation2018, pp. 20–21) and consultations with the authors.

6 Whenever two or more variables are on the same side of an arrow, these are separated by semicolons. For example, “X1”; “X2”→“Y” means that both X1 and X2 lead into Y.

7 is based upon Dyson (Citation2014, p. 41 [Table 3.1], p. 81 [Table 6.1], p. 134 [Table 10.1]) and consultations with the author.

8 For a collection of studies that initiate a wide range of directions in the study of foreign policy errors, see Hermann (Citation2011).

9 is based upon Walker and Malici (Citation2011, p. 5, p. 11 [Figure 1.1], p. 12 [Figure 1.2], p. 54 [Figure 3.1]) and consultations with the authors.

10 See Gansen and James (introduction to this volume) for supporting citations from educational psychology.

11 The extent to which visualization already appears in these three works varies considerably (from one figure in “Understanding New Middle Eastern Leadership” to roughly 100 in U.S. Presidents and Foreign Policy Mistakes). Nevertheless, the pre-existing graphic resources impact favorably upon the systemist visualization process as a foundation beyond the text in and of itself in each case.

References

- Brummer, K., Young, M. D., Özdamar, Ö, Canbolat, S., Thiers, C., Rabini, C., … Mehvar, A. (2020). Coding in tongues: Developing Non-English coding schemes for leadership profiling. International Studies Review, 22, 1039–1067. doi: 10.1093/isr/viaa001

- Canbolat, S. (2014). Understanding the new middle eastern leaders: An operational code approach (Unpublished master’s thesis). İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University.

- Canbolat, S. (2020a). Understanding political Islamists’ foreign policy rhetoric in their native language: A Turkish operational code analysis approach. APSA MENA Politics Newsletter, 3, 13–16.

- Canbolat, S. (2020b). Profiling leaders in Arabic. In forum coding in tongues: Developing Non-English coding schemes for leadership profiling. International Studies Review, 22, 1049–1052.

- Canbolat, S. (2021). Deciphering deadly minds in their native language: The operational codes and formation patterns of militant organizations in the Middle East and North Africa. In M. Schafer & S. G. Walker (Eds.), Operational code analysis and foreign policy roles (pp. 69–92). New York: Routledge.

- Çuhadar, E., Kaarbo, J., Kesgin, B., & Ozkececi-Taner, B. (2017). Examining leaders’ orientations to structural constraints: Turkey’s 1991 and 2003 Iraq war decisions. Journal of International Relations and Development, 20, 29–54. doi: 10.1057/jird.2014.31

- Dekmejian, R. H. (1975). Patterns of political leadership: Egypt, Israel, Lebanon. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Dyson, S. B. (2014). Leaders in conflict: Bush and Rumsfeld in Iraq. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- George, A. L. (1980). Presidential decision making in foreign policy: The effective use of information and advice. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Gourevitch, P. (1978). The second image reversed: The International sources of domestic politics. International Organization, 32, 881–912. doi: 10.1017/S002081830003201X

- Hermann, C. F. (2011). When things go wrong: Foreign policy decision making under adverse feedback. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hermann, M. G. (1980). Explaining foreign policy behavior using the personal characteristics of political leaders. International Studies Quarterly, 24, 7–46. doi: 10.2307/2600126

- Hermann, M. G. (2005). Assessing leadership style: Trait analysis. In J. M. Post (Ed.), The psychological assessment of political leaders. With profiles of Saddam Hussein and Bill Clinton (pp. 178–212). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Herrmann, R. (1988). The empirical challenge of the cognitive revolution: A strategy for drawing inferences about perceptions. International Studies Quarterly, 32, 175–203. doi: 10.2307/2600626

- Hinnebusch, R. (2015). Foreign policy analysis and the Arab world. In K. Brummer & V. M. Hudson (Eds.), The foreign policy analysis beyond North America (pp. 77–100). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Holsti, O. R. (1977). The “Operational Code” as an approach to the analysis of belief systems. Final Report to the National Science Foundation grant number Soc75-15368. Durham, NC: Duke University.

- Hudson, V. M. (2005). Foreign policy analysis: Actor-specific theory and the ground of International relations. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1, 1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-8594.2005.00001.x

- Hudson, V. M., & Vore, C. S. (1995). Foreign policy analysis yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Mershon International Studies Review, 39, 209–238. doi: 10.2307/222751

- James, C. C., & James, P. (2017). Systemism and foreign policy analysis: A new approach to the study of international conflict. In S. Yetiv & P. James (Eds.), Advancing interdisciplinary approaches to international relations (pp. 289–321). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, P. (2019a). What do we know about crisis, escalation and war? A visual Assessment of the International Crisis Behavior project. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 36, 3–19. doi: 10.1177/0738894218793135

- James, P. (2019b). Systemist international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 63, 781–804. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqz086

- Jervis, R. (1976–2017). Perception and misperception in international politics (New edition). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Johnson, R. T. (1974). Managing the white house: An intimate study of the presidency. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Kesgin, B. (2013). Leadership traits of Turkey's Islamist and secular prime ministers. Turkish Studies, 14, 136–157. doi: 10.1080/14683849.2013.766988

- Lebow, R. N., & Stein, J. G. (1987). Beyond deterrence. Journal of Social Issues, 43, 5–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1987.tb00252.x

- Malici, A., & Buckner, A. L. (2008). Empathizing with rogue leaders: Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Bashar al-Asad. Journal of Peace Research, 45, 783–800. doi: 10.1177/0022343308096156

- Özdamar, Ö. (2017). Leadership analysis at a ‘great distance’: Using operational code construct to analyze Islamist leaders. Global Society, 31, 167–198. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2016.1269056

- Özdamar, Ö, & Canbolat, S. (2018). Understanding new Middle Eastern Leadership: An operational code approach. Political Research Quarterly, 71, 19–31. doi: 10.1177/1065912917721744

- Özdamar, Ö, Canbolat, S., & Young, M. D. (2020). Profiling leaders in Turkish. In Forum Coding in tongues: Developing Non-English coding schemes for leadership profiling. International Studies Review, 22, 1045–1049.

- Pfonner, M., & James, P. (2020). The visual international relations project. International Studies Review, 22, 192–213. doi: 10.1093/isr/viaa014

- Schafer, M., & Walker, S. G. (2006). Beliefs and leadership in world politics: Methods and applications of operational code analysis. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tufte, E. R. (2006). Beautiful evidence. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press LLC.

- Walker, S. G., & Malici, A. (2011). US Presidents and foreign policy mistakes. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Walker, S. G., Malici, A., & Schafer, M. (2011). Rethinking foreign policy analysis: States, leaders, and the microfoundations of behavioral international relations. New York: Routledge.

- Walker, S. G., Schafer, M., & Young, M. D. (1988). Systematic procedures for operational code analysis: Measuring and modeling Jimmy Carter's operational code. International Studies Quarterly, 42, 175–189. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00074