ABSTRACT

This article compares Canada’s approach to foreign investment (FDI) policies on a global level at different points in time. Focusing on three publications, it analyzes development of Canadian FDI policies since the 1980s in the context of Kingdon’s model of policy streams. Through the systemist analysis of this chronological development, it identifies factors that have shaped the convergence and divergence of these policy streams. This study also discusses the continuing relevance of these factors, notably growing geopolitical tensions between China and the United States. This study unfolds in six sections. Section one provides an overview of the article. The second section introduces systemism in connection with FDI policies. Sections three through five produce systemist graphics related to each of the above-noted publications. Section six sums up the applications and constraints on systemism as an analytical tool in addressing the evolution of Canadian FDI policies.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article compare l'approche du Canada en matière de politique d'investissement étranger (PIE) au niveau mondial et à différents moments. En se concentrant sur trois publications, il analyse l'évolution des politiques canadiennes en matière de PIE depuis les années 80 dans le contexte du modèle des flux politiques de Kingdon. Grâce à l'analyse systémique de ce développement chronologique, l'article identifie les facteurs qui ont façonné la convergence et la divergence de ces flux politiques. Cette étude aborde également la pertinence continue de ces facteurs, notamment les tensions géopolitiques croissantes entre la Chine et les États-Unis. Cette étude se déroule en six sections. La première section offre un aperçu de l'article. La deuxième présente le systémisme en relation avec les PIE. Les sections trois à cinq produisent des graphiques systémistes en rapport avec chacune des publications mentionnées ci-dessus. La section six résume les applications et les contraintes du systémisme en tant qu'outil analytique pour aborder l'évolution de la politique canadienne d'investissement étranger.

Overview

Canada’s foreign direct investment (FDI) policies have moved from the periphery of Canada’s foreign and international economic policies during the 1970s to closer integration with broader trade and security policies in the 2020s, but with significant variations across international and domestic economic and policy sectors.

This article explores the evolution of Canada’s FDI policies since the 1970s, particularly since 2005, through the lens of “systemism”: a technique for visual representation of theorizing (Pfonner & James, Citation2020, p. 192), applied to three published (or soon-to-be-published) articles by the author. Systemism analyzes the development of different aspects of these policies through Kingdon’s (Citation2011) model of policy streams and windows in successive eras, illustrating the continuing evolution of these policies within North American and wider international political economy.

Kingdon’s model of policy continuity and change notes the interaction of ideas, interests, and institutions of governance in the context of focusing events or “policy windows” – “opportunit(ies) for advocates of proposals to push their pet solutions, or push attention to their special problems” (Kingdon, Citation2011, p. 167). Such events may force a convergence of

policy streams: discourses that affect policy choices in particular fields based on their relative technical feasibility, acceptability to relevant decision-makers and publics, and feasibility within institutional constraints (Kingdon, Citation2011, pp. 131–39); Canadian policy streams generally have elements internal to governments (e.g. public servants in lead departments, advisory bodies), and external sources of policy analysis, including think tanks and academics;

problem streams: conditions which erode or threaten the well-being of politically or economically significant constituencies until they achieve levels of societal awareness and authoritative sponsorship to emerge on the public agenda (Kingdon, Citation2011, pp. 90–115); Beland and Howlett (Citation2016, p. 221), among others, note that policy-makers’ sensitivities to latent or persistent problems are often reinforced by “dramatic” or “focusing” events which increase their relative political prominence or “salience”; and

political streams: the intellectual and/or ideological orientation of relevant decision-makers, trends in public opinion or the agendas of “organized political forces,” and opportunities within the electoral cycle, including changes of government and key government decision-makers (Kingdon, Citation2011, pp. 145–64). Significant policy changes usually require authoritative policy champions (including “policy entrepreneurs”) within governments capable of translating particular proposals into authoritative actions to addressed politically salient problems (Tomlin, Hillmer, & Hampson, Citation2007). However, the choices of key actors are often sensitive to questions of political timing, especially electoral cycles, and balancing of major stakeholder interests within constraints of public opinion.

Central to Kingdon’s analysis – as with various theories of bureaucratic politics in international relations – is the premise that the modern state is rarely a unitary actor. This premise is particularly applicable to international trade and investment policies, in which governments seek to balance varied domestic (state and societal) interests and policy goals with international policy objectives, often using a mix of offensive and defensive policy instruments (Kukucha, Citation2016).

This article uses systemism to summarize three of the author’s articles on significant dimensions of Canadian FDI policies since 1985. These articles explore federal responses to extensive inward FDI-related merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in 2005–08 for Canada’s market-based FDI regime, subsequent responses to increasing M&A activity by foreign state-controlled enterprises (SCEs), and the emergence of national security reviews as major instruments for screening FDI. The first two articles are case studies; the third is a policy note for a wider comparative study.

“The Dog that Hasn’t Barked” case study (Hale, Citation2008) explores the structural economic factors which helped to diffuse pressures for domestic government intervention to constrain unprecedented levels of foreign takeovers of Canadian businesses during the 2005–08 market boom. It seeks to explain the resilience of Canada’s FDI regime within the broader (WTO) international trade system despite significant domestic contestation. It highlights the intermestic character of policy streams which govern M&A activity by market-based corporations.

The CNOOC-Nexen case study (Hale, Citation2014) assesses the disruptive political and policy impacts of the largest takeover to date of a major Canadian firm by a foreign-based SCE in 2012. The political window opened by this transaction exposed several competing policy streams with cross-cutting implications for Canada’s efforts at market diversification, interaction with different economic systems, and related issues of sovereignty and national security.

“Converging and Diverging Streams” (Hale, Citation2022 forthcoming) explores the maturing of these intersecting streams and their interaction with a renewed interest in strategic sector approaches to FDI regulation. It concludes with an overview of factors which have shaped the convergence and divergence of these policy streams, including growing geopolitical tensions between the United States and China.

This study unfolds in five additional sections. The second section introduces systemism in connection with foreign investment policies. Sections three through five produce systemist graphics corresponding to each of the above-noted publications. Section six sums up the applications and constraints on systemism as an analytical tool for Canadian FDI policies.

Systemism and foreign investment policies

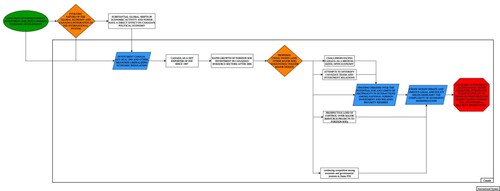

Systemism uses variables to display graphically links in a series of relationships describing a causal process (Pfonner & James, Citation2020). This technique enables analysts to address policy challenges on different levels of aggregation. The nature of Canadian FDI policy requires acknowledgement of at least four levels of aggregation: international, regional (North American), national economic and security-related, and sub-national, whether particular industry sectors, provincial economic strategies, or both. As noted in Gansen and James (introduction to this volume), systemism identifies both macro- and micro variables contributing to policy outcomes in a system, along with reciprocal effects involving its environment. provides an overview of key concepts and notations used in subsequent figures.Footnote1

Table 1. Systemist notation.

Canadian FDI policies and their relationship to international economic policies and the global economic system have shifted substantially since the 1980s. Debates over foreign investment between the 1940s and 1980s involved successive trade-offs primarily within domestic economic policies between attracting foreign capital to finance economic development, including infrastructure, beyond the immediate capacity of domestic capital markets, and governments’ pursuit of industrial policies to encourage the more rapid development (often including domestic control of) particular economic sectors (Bliss, Citation1985). At times, they also championed a defensive economic nationalism (Aitken, Citation1967) aimed at limiting Canadian dependence on US and other foreign capital and reducing imbalances of economic power between capital exporting and importing countries. These goals informed more restrictive inward FDI policies during the 1970s and early 1980s.

Among others, Hart (Citation2002), has argued that the federal government’s simultaneous pursuit of closer North American integration since 1985 and its support for US efforts to strengthen the multilateral trading system complemented traditional Canadian efforts to pursue relative discretion in foreign (and domestic economic) policy decision-making while maximizing the benefits of working within the US orbit. The negotiation of successive international trade agreements, such as the Canada–US (CUFTA) and North American (NAFTA) Free Trade Agreements, and the Uruguay Round Agreement, have provided an international anchor for reciprocal policy commitments, often constraining unilateral or discriminatory uses of domestic policy instruments.

However, the exclusion of protected or “strategic” sectorsFootnote2 from broader North American and multilateral (WTO) commitments is consistent with Kukucha’s characterization (Citation2016) of simultaneous “offensive” and “defensive” elements in Canadian trade policies. The use of domestic policies to promote the internationalization of major Canadian-based businesses (“outward FDI”), which combined “grandfathering” of multiple exceptions and potentially open-ended application of GATT Article XXI’s national security provisions (Alexandroff & Sharma, Citation2005), also requires continued balancing of domestic and international priorities in Canada’s FDI policies.

FDI-related national security concerns have increased with the growing role of state-controlled and influenced corporations (SCEs) in global and Canadian markets since 2005, particularly from authoritarian states such as China and Russia. These developments add a significant foreign policy dimension to traditional domestic political considerations. These factors, together with Canada’s strong commitment to the preservation of rules-based, generally reciprocal international trade and investment systems and continued growth of Canadian direct investment abroad, reinforce the “intermestic” character of foreign investment policies, blurring traditional international/domestic policy distinctions (Hale, Citation2012; Manning, Citation1977).

Nice Dog … Nice Dog

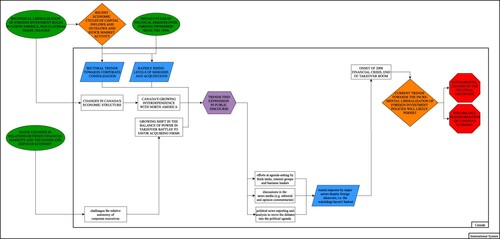

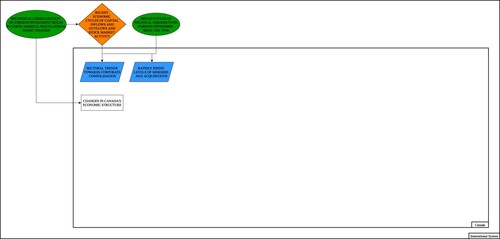

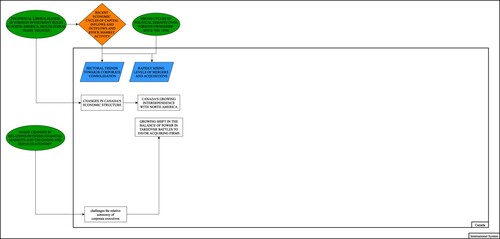

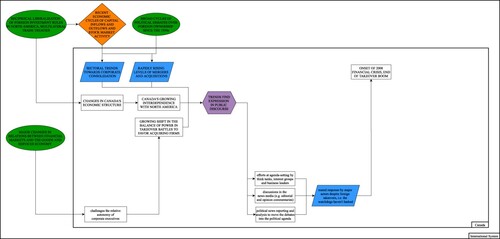

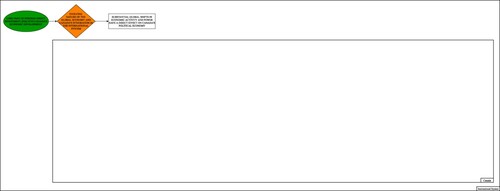

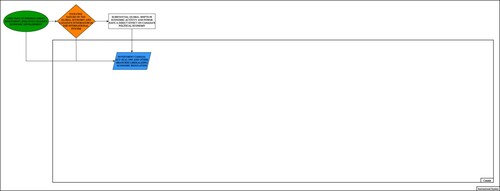

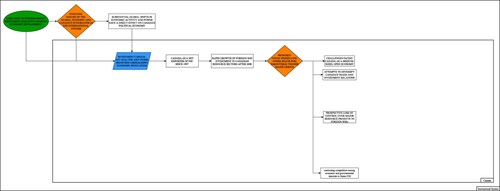

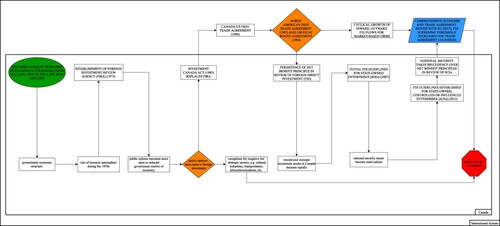

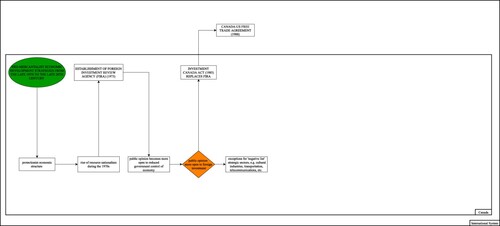

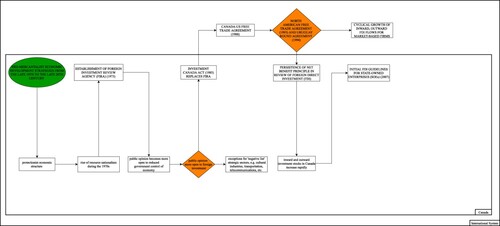

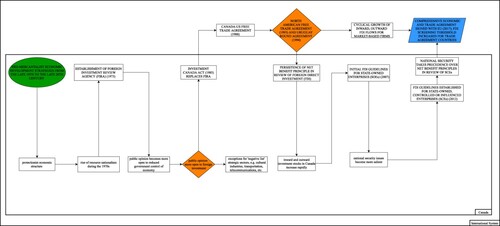

“The Dog that Didn’t Bark” is a case study that analyzes interaction between domestic political debates and intermestic policy realities over the record volume and value of foreign takeovers of major Canadian-based corporations in 2005–08. displays the story of cause and effect from “The Dog that Didn’t Bark” in a systemist graphic form. shows Canada as the system, and the international system as its environment. Macro and micro levels within Canada correspond, respectively, to developments within the country and its society.

Figure 1. The dog that hasn't barked: the political economy of contemporary debates on Canadian foreign investment policies ( Hale, Citation2008) Diagrammed by: Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

Consider Canada’s historically ambivalent position within the international economic system. Initial variables selected reflect underlying aspects of systemist analysis. Canadian foreign investment debates have long reflected tensions between its vulnerability to international economic forces and shifting policy preferences of its major trading partners and competing nation- (or province-) building strategies, along with debates over the most effective strategies to reconcile these tensions (Bow & Lennox, Citation2008; Bradford, Citation1998). The interaction of new waves of financial globalization, partial domestic deregulation, and financial sector innovation between the 1980s and 2010s have added additional dimensions to these debates.

recognizes “BROAD CYCLES OF POLITICAL DEBATE OVER FOREIGN OWNERSHIP SINCE THE 1950s” as an initial variable (green oval); its relationship to the role of the Canadian state and Canada’s evolving place in the international economic order are a recurring reality of Canadian political life. Both “policy” and “problem” streams, in Kingdon’s terminology, often have been contested. The intensity of debate frequently correlates with the potential for higher resource rents from rising global commodity prices, which tend to attract higher volumes of FDI – as in other traditionally resource-based economies. Unlike earlier similar debates, however, Canadian FDI policies since the 1990s have functioned within the constraints of North American (NAFTA) and multilateral trade treaties (Uruguay Round/WTO), which provide for “RECIPROCAL LIBERALIZATION OF FOREIGN INVESTMENT RULES IN NORTH AMERICA, MULTILATERAL TRADE TREATIES”, another initial variable (green oval) ((b)), subject to historical “negative list” exceptions negotiated by participating governments.

Significantly, from the perspective of Kingdon’s “political stream,” Canadian FDI policies demonstrated broad continuity from changes initiated by the Mulroney government (1984–93), and consolidated under the Chrétien (1993–2003), Martin (2003–06) governments. No Canadian government used the Investment Canada Act’s (ICA) “net benefit” provisions to block investments between their passage in 1985 and 2007, despite cyclical takeover “waves” in 1995–2000 and 2005–08.

(c) portrays the immediate consequences of FDI (and trade) liberalization from CUFTA and NAFTA: “RECIPROCAL LIBERALIZATION OF FOREIGN INVESTMENT RULES IN NORTH AMERICA, MULTILATERAL TRADE TREATIES” → “CHANGES IN CANADA’S ECONOMIC STRUCTURE”. Trade liberalization encouraged widespread industrial restructuring and varying degrees of sectoral integration within North American and wider global economies. These developments reinforced the international divergent variable, (, orange diamond), “RECENT ECONOMIC CYCLES OF CAPITAL INFLOWS AND OUTFLOWS AND STOCK MARKET ACTIVITY”. Declining inflation and interest rates stimulated significant growth in stock market activity. For example, the market capitalization of the TSX, Canada’s largest stock exchange, grew 240 percent between January 1993 and July 2000 (Trading Economics, Citation2020).

Ongoing trends towards trade liberalization, especially in North America, combined with Canada’s growing integration within international capital markets to produce cross-cutting effects that contributed to converging variables diagrammed in (blue parallelogram): “RECENT ECONOMIC CYCLES OF CAPITAL INFLOWS AND OUTFLOWS AND STOCK MARKET ACTIVITY”; “BROAD CYCLES OF POLITICAL DEBATES OVER FOREIGN OWNERSHIP SINCE THE 1950s” → “RAPIDLY RISING (if cyclical) LEVELS OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS”; “SECTORAL TRENDS TOWARDS CORPORATE CONSOLIDATION”.Footnote3 For the first time in Canadian history, overall Canadian Direct Investment Abroad (CDIA) stocks exceeded inward FDI stocks in 1997. During both the 1990s and 2000s, earlier parts of market cycles were characterized by the rapid growth of Canadian multinational firms (MNCs), with high-profile foreign takeovers of Canadian-based firms growing as each cycle progressed.

adds a further macro-macro connection: “CHANGES IN CANADA’S ECONOMIC STRUCTURE" → “CANADA’S GROWING INTERDEPENDENCE WITH NORTH AMERICA”, resulting from established trends which predated CUFTA’s negotiation in 1986–88. Canadian firms’ capacity to expand through M&A activity within and beyond North America often paralleled the extent or conditions of foreign-based firms’ access to Canadian markets.

A third initial variable (, green oval) which enabled these takeover cycles reflected “MAJOR CHANGES IN RELATIONS BETWEEN FINANCIAL MARKETS AND THE GOODS AND SERVICES ECONOMY”. This macro variable also operated in the international environment. Lower barriers to entry and consolidation in Canadian financial services sectors after 1985 catalyzed Canadian banks’ expansion into large-scale investment banking and facilitated multiple new entrants in Canadian and global capital markets. Previously noted trends towards disinflation and declining interest rates encouraged shifts in Canadians’ savings – including those of major pension plans – into equity markets. These developments transformed traditional relationships between financial and non-financial sector firms, increasing the power of institutional investors, fostered broader cultures of shareholder capitalism in both the US and Canada, and reinforced a regulatory environment more protective of minority shareholders (Gourevitch & Shinn, Citation2005; Hale, Citation2018, pp. 318–44).

These trends often reinforced the role of corporate boards as fiduciaries of shareholder interests, with results noted in : → “challenges the relative autonomy of corporate executives”. These trends contributed to macro outcomes noted in : → “GROWING SHIFT IN THE BALANCE OF POWER IN TAKEOVER BATTLES TO FAVOUR ACQUIRING FIRMS”, further reinforcing the takeover booms of the 1990s and, more particularly, 2005–08.

shows the convergence of multiple pathways representing economic trends and cross-cutting interests in a new nodal variable (purple hexagon) noted above: “SECTORAL TRENDS TOWARD CORPORATE CONSOLIDATION”; “RAPIDLY RISING LEVELS OF MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS”; “CANADA’S GROWING INTERDEPENDENCE WITH NORTH AMERICA”; “GROWING SHIFT IN THE BALANCE OF POWER IN TAKEOVER BATTLES TO FAVOR ACQUIRING FIRMS” → “TRENDS FIND EXPRESSION IN PUBLIC DISCOURSE”. This variable catalyzed multiple discourse linkages contributing to the intersection of Kingdon’s “problem streams,” “policy streams,” and “political streams.” The declining autonomy of corporate executives and their firms’ vulnerability to takeovers might form a “problem stream” for executives (and nationalists) disturbed by takeovers of major Canadian firms during this period, but also opportunities for more efficient (and profitable) use of capital for many shareholders, informing a broader “policy stream” for many policy analysts and financial journalists.

shows micro-level pathways emerging from the nodal variable: → “efforts at agenda-setting by think tanks, interest groups and business leaders”; “discussions in the news media (e.g. editorial and public commentaries)”; “political news reporting and analysis to move the debates into the public agenda”. A cross-section of think tanks, interest groups, and business leaders competed in multiple venues in “efforts at agenda-setting” by interpreting and contextualizing takeover trends, seeking to influence government, media, and public perceptions of the “problem(s)” – domestic and international – to be addressed by government action “through discussions in the news media e.g. editorial and opinion commentaries” (). Competing groups also sought to leverage “political news reporting and analysis,” hoping to influence a minority government heavily dependent on opposition votes to remain in power.

Debates within news media and business circles in 2005–07 recalled previous public scares over widespread foreign takeovers, not least the wholesale takeover of Canadian-based steelmakers. However, other voices noted that the aggregate value of M&A transactions was relatively balanced between inward and outward acquisitions over the market cycle. The continued growth of Canadian-based multinationals (MNCs) – and their outward FDI – provided a political safety valve for Kingdon’s “problem stream” through the peak of the takeover boom. This balance enabled the federal government to emphasize reciprocal, rule-based approaches to FDI– maintaining continuity within Kingdon’s “political” and “policy” streams.

The Harper government responded to these trade-offs by choosing to deflect and reframe debate, and to defer a decision by appointing an external review panel. , a blue parallelogram, shows the three micro pathways coming together in a convergent variable: “muted response by major actors despite foreign takeovers, i.e. the watchdogs haven't barked”.

In July 2007, at the peak of the takeover boom, the federal government appointed the Competition Policy Review Panel (Industry Canada, Citation2007), composed of senior business executives and former government officials. Its terms of reference framed the takeover debate in the broader context of competition and market dominance in a global economy, signaling Ottawa’s decision to maintain control of the political stream and defer any decisions until after the panel’s report.

The deferral between the panel’s appointment and its June 2008 report coincided with a significant development noted in : “ONSET OF 2008 FINANCIAL CRISIS, END OF TAKEOVER BOOM”. Indeed, the Panel’s Report (2008) ultimately recommended major increases in thresholds for screening inward M&A activity by market-based firms, although these changes were not implemented until the conclusion of Canada–EU trade talks in 2017.

The article concludes that incremental liberalization of Canada’s FDI policies and related changes in domestic political discourse are likely to persist as long as Canadians continue to benefit from rising incomes and increased job security. portrays this anticipated outcome, “CURRENT TRENDS TOWARDS THE INCREMENTAL LIBERALIZATION OF FOREIGN INVESTMENT POLICIES WILL LIKELY PERSIST” as a divergent variable (orange diamond) in contrast to historical patterns of Canadian domestic debates over FDI. This assessment has subsequently been vindicated, at least for policies governing market-driven firms. In sharp contrast to previous debates, illustrates the inability of nationalist “watchdogs” to shift public debate despite unprecedented levels of foreign takeoverspointtoward two results (terminal variables / red octagons): “FUNDAMENTAL CHANGES OF THE POLITICAL DISCOURSE”; “REMARKABLE TRANSFORMATION OF CANADA’S ECONOMY”.

This retrospective review of “The Dog that Didni’t Bark” illustrates the value of systemism to case study analysis, particularly in combination with Kingdon’s “multiple streams” model. The latter helps to identify contingencies arising from the interaction of individual agency – e.g. political leaders leveraging their central positions to guide policy processes – with system-level forces. The final section of “The Dog That Didn’t Bark” notes two prospective caveats to these conclusions. It suggests that continued public support for relatively unfettered FDI flows could depend on “measures to secure reciprocal measures from foreign governments and discipline the market behaviour of state-controlled or influenced enterprises.” Ironically, policies aimed at the latter outcome became the next major inflection point for Canada’s FDI policies.

Closing the barn door

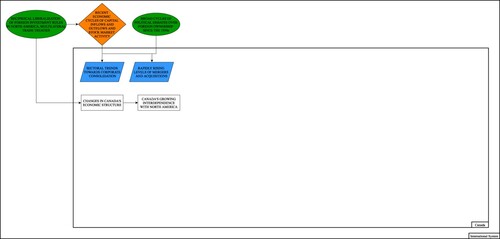

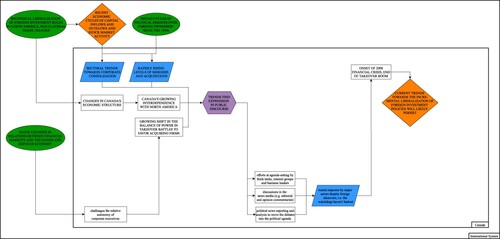

“CNOOC-Nexen, State-Controlled Enterprises and Canadian Foreign Investment Policies” is a 2014 case study which addresses the evolving context for FDI and related policies that shaped the Canadian government’s response to the largest takeover to date of a major Canadian firm (Nexen Inc.) by a SCE: China National Overseas Oil Company (CNOOC) in 2012. In Kingdon’s multiple policy streams model, the CNNOC-Nexen takeover was a focusing event which exposed latent tensions in Canada’s trade diversification and FDI policies. The Harper government permitted the takeover under existing FDI and international trade rules after extended review. But its decision also expanded provisions for screening SCE investments in Canada. This case study marks a turning point – divergence in systemist terms – distinguishing between FDI rules governing market-based transactions and those involving foreign SCEs as distinct policy streams, with more extensive national security screening of proposed investments.

This transaction opened a political window involving the intersection of four policy streams: (i) pursuit of export market diversification for Canada’s resource exports; (ii) longstanding domestic FDI restrictions in strategic (or politically-sensitive) sectors; (iii) growing concerns over limits on genuine reciprocity in market access and competition between market-based and state-controlled or “influenced” firms (SCEs), particularly those based in authoritarian, non-market economies without independent judicial systems; and (iv) application of national security considerations to FDI transactions.

SCEs have become significant players in global equity markets and business operations. Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) from both Western “developed” (e.g. Norway) and “emerging” economies (e.g. Middle Eastern petrostates, Singapore) have long invested in public markets, usually with commercial orientations. Although many Western countries privatized much of their state-owned sectors between the 1980s and 2000s, many newly-industrialized countries retained state control of resource and industrial firms either through direct ownership (SOEs) or other means of exercising political leverage and effective control (SCEs). By 2012, SOEs (15) and SCEs (2) accounted for two-thirds of the world’s 25 largest oil and gas firms by production volume (Helman, Citation2012). Many of these firms expanded their international operations during of the 2000s. Some of these investments displaced Western shareholder-owned firms that faced higher levels of public and political scrutiny in their countries of origin related to human rights or environmental concerns, or vulnerability from resource nationalism in host countries. Responding to such challenges, several Canadian resource firms divested international assets – generally to SOEs from China and/or India (e.g. Kobrin, Citation2004; McClearn, Citation2005).

During this period, Canada welcomed growing resource sector investment by foreign-based SOEs, usually as part of broader investment consortia or joint ventures. Some foreign SOE activity sought to secure access to Canadian resources as investments in home country energy security or industrial production. With growing US environmental opposition to expansion of Canadian-based pipelines and other resources, such investments complemented Ottawa’s policy goals of diversifying markets for Canadian resources. The Harper government enacted ICA regulations governing SOE transactions in 2007, institutionalizing a separate “policy stream” within Kingdon’s model but with little effect on investment flows before the 2012 CNOOC-Nexen takeover proposal.

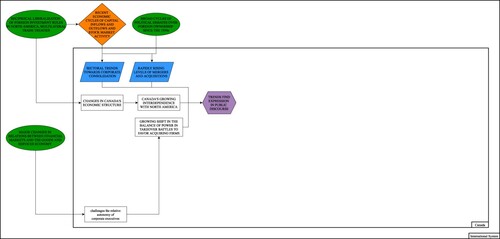

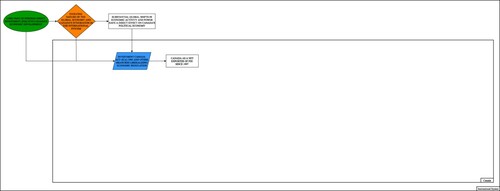

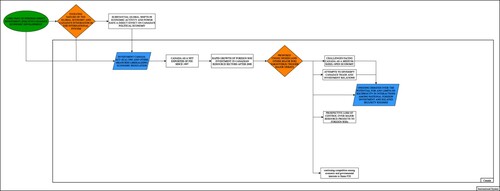

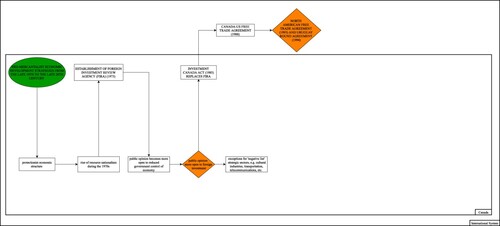

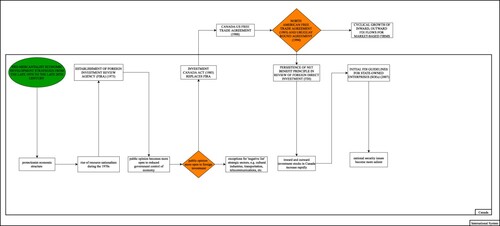

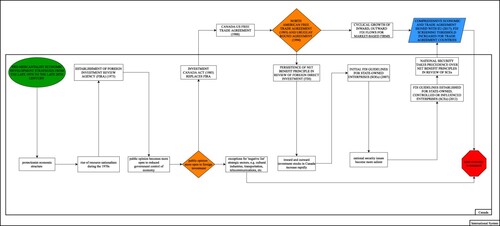

provides a cause-and-effect summary of the CNOOC-Nexen article. Canada as a system, along with the international system as its environment, appear in . The initial variable (, green oval), “LONG PAST OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN CANADA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT”, condenses more than a century of dependence on foreign capital for economic development and related controversies of economic nationalism. Several factors discussed in the previous section of this article are also condensed in the divergent variable (orange diamond) noted in (c): “EVOLVING NATURE OF THE GLOBAL ECONOMY AND CANADA’S INTEGRATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM”. This composite variable includes factors such as reciprocal liberalization of trade policies and Canada’s progressive integration within North American energy markets.

Figure 2. CNOOC Nexen, state-controlled enterprises and Canadian foreign investment policies: adapting to divergent modernization (Hale, Citation2014) Diagrammed by: Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

recognizes a further variable: “SUBSTANTIAL GLOBAL SHIFTS IN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY AND POWER HAVE A DIRECT EFFECT ON CANADA’S POLITICAL ECONOMY”. Although Ottawa and several provinces had used crown corporations (SOEs) to control resource development before 1985, most resource sector SOEs outside the electrical utility sector were privatized in the 1980s and 1990s (Boardman & Vining, Citation2012), sometimes with legislated ownership constraints.

shows convergence of several pathways (blue parallelogram): “LONG PAST OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN CANADA’S ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT”; “EVOLVING NATURE OF THE GLOBAL ECONOMY AND CANADA’S INTEGRATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM”; “SUBSTANTIAL GLOBAL SHIFTS IN ECONOMIC ACTIVITY AND POWER HAVE A DIRECT EFFECT ON CANADA’S POLITICAL ECONOMY” → “INVESTMENT CANADA ACT (ICA) 1985 AND OTHER MEASURES LIBERALIZING ECONOMIC REGULATION”. The Investment Canada Act of 1985, with its “net benefit test” and higher screening thresholds, replacing the more restrictive Foreign Investment Review Act (FIRA) of 1973 and its “significant benefit test.” This was a key domestic point of convergence which shaped Canada’s adaptation to these forces. Subsequent trade agreements further liberalized investment rules and provided for regulatory reciprocity in North American and global contexts.

Indeed, the cumulative effect of these measures encouraged rapid growth of both inward and outward FDI during the 1990s, as reflected in : → “CANADA AS A NET EXPORTER OF FDI SINCE 1997”, reversing previous patterns of FDI dependence. Widespread divestiture of Canadian resource assets by foreign MNCs during the 1990s created significant opportunities for the growth of major Canadian-based firms. Nexen Energy, a former subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum, became independent in 2000, growing its domestic and international operations to become Canada’s 8th largest oil firm by 2012. The escalation of global oil and gas prices after 2000 attracted large amounts of foreign capital, both in conventional operations and Alberta’s oil sands. However, after the price crash of 2008–09, foreign-based (including Chinese) SOE investments grew rapidly as illustrated in : → “RAPID GROWTH OF FOREIGN SOE INVESTMENT IN CANADIAN RESOURCE SECTORS AFTER 2008”. The Harper government welcomed these investments for their contribution to economic growth and their potential contribution to diversifying Canadian energy markets. Notwithstanding a more restrictive US environment for foreign SOE investment after 2004, such investments were not viewed as a “problem stream” in Canada until 2012.

However, political and policy dynamics changed significantly when Chinese SOE CNOOC made a friendly offer to purchase Nexen Energy for $US15.1 billion in June 2012: the single largest foreign SOE acquisition in Canadian history – illustrated in ’s divergent variable (orange diamond), → “PROPOSED CNOOC-NEXEN (AND OTHER MAJOR SOE) TAKEOVER(S) TRIGGER MAJOR DEBATE”.The proposed deal triggered a major debate over the extent to which an FDI regime designed for market-based firms based on national reciprocity was compatible with large-scale SOE investments from non-market-based economies (e.g. China) without independent legal regimes capable of adjudicating disputes fairly.

The CNOOC-Nexen deal spilled over into several policy and problem streams, diagrammed in (i): → “CHALLENGES FACING CANADA AS A MEDIUM-SIZED, OPEN ECONOMY”; “ATTEMPTS TO DIVERSIFY CANADA’S TRADE AND INVESTMENT RELATIONS”; “PROSPECTIVE LOSS OF CONTROL OVER MAJOR RESOURCE PROJECTS TO FOREIGN SOEs”; and “continuing competition among economic and governmental interests to frame FDI”. The deal highlighted challenges across several policy and problem streams facing Canada’s one-size-fits-all FDI regime as a medium-sized open economy. It tested Canada’s commitment to the rule of law: applying existing rules to different SOE takeovers with very different domestic and international policy implications.

The CNOOC-Nexen deal tested major resource producers’ relative openness to FDI, raising fears of the prospective loss of control over major resource projects in Alberta’s oilsands to foreign SOEs, evoking memories of the wholesale foreign takeover of major Canadian steel-makers in 2005–07, even as smaller producers continued to welcome foreign capital (and takeovers).

These cross-cutting challenges triggered vigorous debates among government and among business interests and policy groups over ways of reconciling competing objectives – or choosing priorities among them, condensed in : “continuing competition among economic and governmental interests to frame FDI”. Major industry figures questioned the government’s ability to enforce conditions imposed on SOEs given existing challenges in enforcing such conditions against market-based companies (Vanderklippe, McCarthy, & McNish, Citation2012). Prominent economist Jack Mintz (Citation2012) asked: “should Canada permit the nationalization of its business sector through foreign state ownership?” – after privatizing its crown corporations to achieve greater productivity and competitiveness. Another major debate related to the capacity of international agreements between countries such as China and Canada with very different political, economic and legal systems and huge differences in relative size, power, and openness to achieve meaningful levels of reciprocity beyond conventional provisions for “national treatment” of foreign investors.

Others argued that being seen to discriminate against Chinese investments placed billions of dollars of Canadian agri-food and other resource exports at potential risk, aggravating political contests among domestic industries (and their political sponsors).

Pathways from these debates converged in (blue parallelogram): → “ONGOING DEBATES OVER THE POTENTIAL FOR AND LIMITS ON RECIPROCITY IN INTERACTIONS AMONG NATIONAL, FOREIGN INVESTMENT AND RELATED SECURITY REGIMES”. reveals another convergent variable (blue parallelogram): “→ ‘CNOOC-NEXEN DEBATE AND VARIOUS LEGAL AND POLICY ISSUES HIGHLIGHT THE COMPLEXITY OF DIVERGENT MOBILIZATION’”: the substantial institutional and policy differences among countries at different stages of development in growing and diversifying their economies.

These debates, which reflected the convergence of multiple policy, problem, and political streams according to Kingdon’s model, slowed the Harper government’s internal policy processes. Rather than an external inquiry, as in the previous case study, the government’s internal review was directed by a special cabinet committee chaired by the Prime Minister and containing both apparent supporters and opponents of increased Chinese investment.

In December 2012, Harper finally announced the government’s decision. Both CNOOC-Nexen and the parallel Petronas-Progress deal were allowed to proceed, subject to legal assurances under existing ICA provisions. The resulting three-tier approach is summarized in the terminal variable (red octagon), in : → “CANADIAN GOVERNMENT ALLOWS CNOOC-NEXEN TAKEOVER, INTRODUCES TIERED FDI POLICY TO SEPARATE PROCESSES FOR MARKET-BASED, FOREIGN SCE, AND NATIONAL SECURITY SENSITIVE FDI”.

The CNOOC-NEXEN case study catalyzed explicit segmentation of Canadian FDI policies (and policy “streams”) between market-based proposals and foreign state-based and national security sensitive takeovers. A fourth, pre-existing stream of politically-sensitive domestic industries excluded from international trade and investment agreements paralleled these emerging policy streams.

As with the previous article, this case study illustrates the value of systemism as an analytical tool, particularly in tandem with Kingdon’s policy streams model. The wider international implications of debates among key policy-makers reduced the relative importance of individual agency in policy decisions, visible in occasional federal vetoes of controversial transactions (e.g., Macdonald Dettwiler, 2008; Potash Corp., 2010). It led instead to formalization of separate policy systems to reconcile tensions among competing policy goals and rival societal interests. The next section of this article examines implementation of these measures since 2012 and the changing geopolitical context for trade and investment relations.

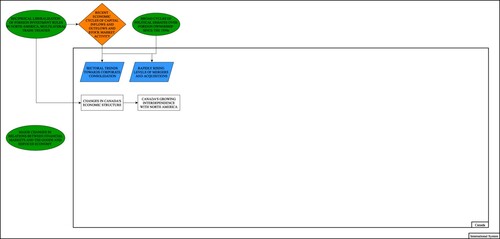

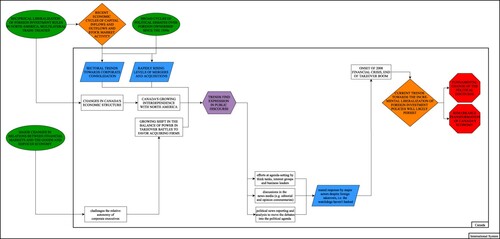

Bifurcated FDI policies: market-driven reciprocity, state-influenced corporations, and national security

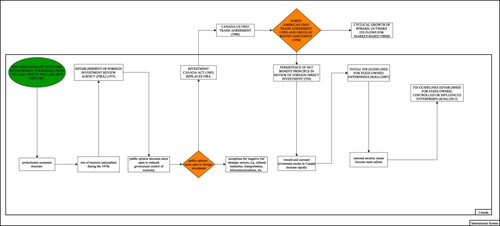

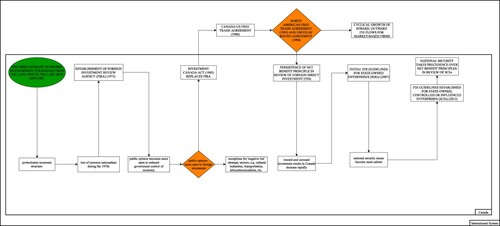

The third article reviewed here is a book chapter entitled “State-Owned and Influenced Enterprises and the Evolution of Canada’s Foreign Direct Investment Regime” in a comparative collection entitled Regulation of State-Controlled Enterprises, edited by Julien Chaisse, Jędrzej Górski, and Dini Sejko (2022 forthcoming). Noting the evolution of “multiple personalities” in Canada’s FDI regime since the 1980s, it distinguishes between investments by market-based firms outside historically protected sectors, SCEs and, particularly, investments which raise national security concerns.

The chapter is organized in five parts: (i) an introduction, (ii) a historical overview of Canada’s post-1973 FDI regimes; (iii) a summary of the evolution of Canada’s state enterprise sector; (iv) debates over foreign state-owned and “influenced” investors including the evolving processes and geopolitical context for national security screening of such investments since 2014, and (v) a conclusion summarizing the chapter’s findings.

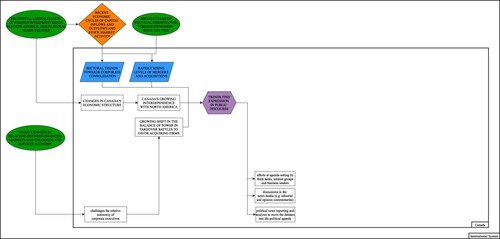

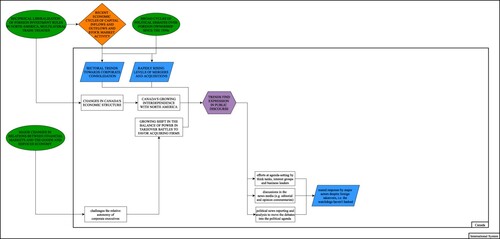

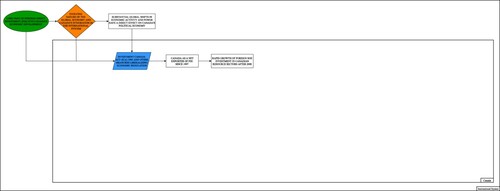

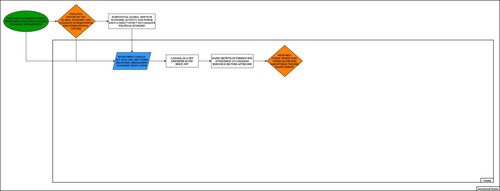

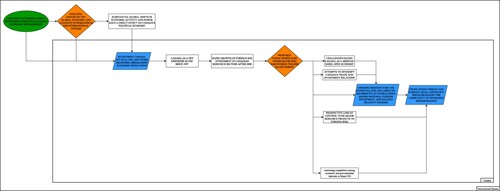

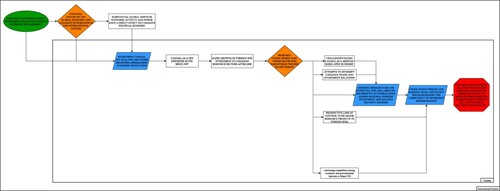

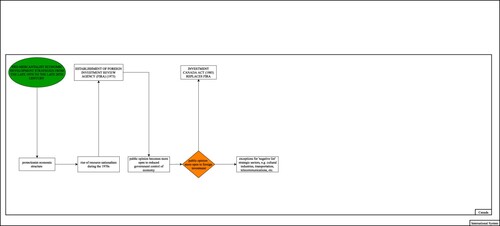

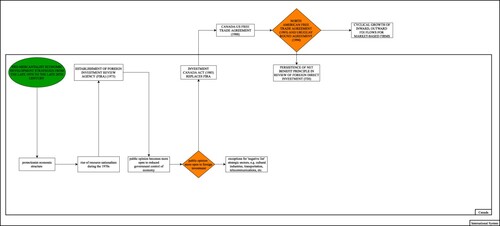

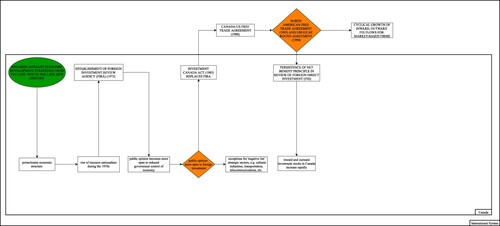

provides a systemist overview of the evolution of Canada’s FDI regimes from the article that encapsulates major elements of continuity and change since the 1970s. , as in earlier instances, shows Canada as the system, and the international system as its environment, with macro and micro levels referring, respectively, to processes at the national level and within society.

Figure 3. State-owned and influenced enterprises and the evolution of Canada's foreign direct investment regime (Hale, Citation2022 forthcoming ) Diagrammed by: Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

The initial variable (), “NEO-MERCANTILIST ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES FROM THE LATE 19th TO LATE 20th CENTURY,” telescopes varied federal and provincial economic development strategies used to encourage FDI in selected sectors, while reserving selected “strategic” or protected sectors for Canadian ownership. It is selected to illustrate Canada’s long history of pursuing “offensive” and “defensive” trade and investment policy objectives and instruments, noted earlier. The outcome of these strategies, noted in , is → “protectionist economic structure.” identifies a second major micro-generic variable contributing to changes in Canada’s FDI regime: “protectionist economic structure” → “rise of resource nationalism during the 1970s”. The next step () is → “ESTABLISHMENT OF THE FOREIGN INVESTMENT REVIEW AGENCY (FIRA) IN 1973”. As noted previously, FIRA made new greenfield investments and takeovers of Canadian-based firms subject to a “significant benefit test,” somewhat discouraging new inward FDI. identifies outcomes from significant regional conflicts over these policies, combined with a major recession in 1981–82: → “public opinion becomes more open to reduced government control of the economy”. This development produced the next step in – a divergent variable (orange diamond) reflecting the strong electoral reaction against the (previous) Trudeau government’s nationalist and interventionist policies: → “public opinion more open to foreign investment”.

The Mulroney government, elected in 1984, responded to these developments by introducing greater liberalization (vertical arrow, ) while safeguarding several politically sensitive domestic sectors. → “INVESTMENT CANADA ACT (1985) REPLACES FIRA”; a horizontal arrow notes “exceptions for ‘negative list’ strategic sectors, e.g. cultural industries, transportation, telecommunications, etc.”. These provisions to safeguard domestic economic sectors, effectively created separate and persistent policy streams for market-driven and protected sectors. The new Act also replaced FIRA’s “significant benefit” test for new FDI with the “net benefit principle,” rather than removing all constraints on FDI in market-driven sectors.

extends the macro-level pathway into the international system: → “CANADA–US FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (1988)”. These principles (and disciplines on their use) were entrenched in that bilateral deal, which began the process of formally integrating Canada’s domestic FDI regime into its international economic commitments. These international commitments were broadened and deepened in the next divergent variable (, orange diamond) “→ “NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT (1993)” AND URUGUAY ROUND AGREEMENT (1994)”. These agreements established FDI policy anchors of formal reciprocity in plurilateral and multilateral agreements, with results noted in : “CYCLICAL GROWTH OF INWARD, OUTWARD FDI FLOWS FOR MARKET-BASED FIRMS”, a broader global phenomenon noted previously in the article. (k,l) also depict the accompanying impact at the (domestic) macro and micro levels, respectively: → “PERSISTENCE OF NET BENEFIT PRINCIPLE IN REVIEW OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI) → inward and outward investment stocks in Canada increase rapidly”. The “net benefit” principle, noted in the first case study, continues to inform Canada’s FDI screening regulations in the 2020s, but only for much larger transactions.

extends the pathway → "INITIAL FDI GUIDELINES FOR STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES (2007)". These measures were intended to encourage national governments to adopt market-based, arms-length governance principles and investment practices for their SOEs and Sovereign Wealth Funds to justify comparabletreatment in market-based economies (Marchick & Slaughter, Citation2008).

Following the global financial crisis of 2007–09, changes in power-dynamics between state-capitalist and market-based economies occurred due to growing investments by foreign SCEs. As a result of the CNOOC-Nexen takeover discussed previously in this article, notes macro developments: → “FDI GUIDELINES ESTABLISHED FOR STATE-OWNED, CONTROLLED, OR INFLUENCED ENTERPRISES (SCEs) (2012)”, with subsequent outcomes noted in : → “NATIONAL SECURITY TAKES PRECEDENCE OVER NET BENEFIT PRINCIPLES IN REVIEW OF SCEs”.

Unlike the U.S., national security was largely an afterthought in Canada’s FDI regime until 2009, following Ottawa’s 2008 rejection of the sale of specialized defence contractor Macdonald Dettwiler to a US-based firm. While post-CNOOC-Nexen regulations reinforced incentives for greater reliance on market governance in SCE acquisition, the chapter’s analysis clearly indicates that national security screening subsequently has become the principal means of regulating SCE acquisitions in Canada.

Such screening initially appeared more restrictive for telecommunications, along with other technologically sensitive and critical infrastructure-related sectors. These shifts preceded growing system-wide competition between the US and China since 2016. During the same period, however, the pathways converge somewhat, as shown by : → “COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC AND TRADE AGREEMENT SIGNED WITH EU (2017): FDI SCREENING THRESHOLD INCREASED FOR TRADE AGREEMENT COUNTRIES”. This designation refers to those nations (including the US and Japan) with which Canada has ratified bilateral or plurilateral agreements, reflecting recommendations of the Competition Policy Review Panel (Citation2008, June) referenced above.

However, these provisions also have reinforced and extended the distinction in Canada’s FDI regime between market-based firms (based on reciprocal recognition and national treatment) and SCE investments, especially from state capitalist regimes, due to the presumption of greater national security risks in the latter. While Canada continues to maintain protected sectors, subject to requirements for either Canadian or “widely-held” private ownership, applications of most-favoured nation (MFN) principles to liberalized investment rules with predominantly market-based economies have strengthened provisions to maintain an open economy for Canada, rooted in principles of reciprocity noted in ’s terminal variable (red octagon) → “open economy is sustained”. This outcome reflects growing distinctions since 2014 between investments from countries with market-based investment regimes with their (generally) reciprocal recognition of investors’ legal rights and obligations, and non-market state capitalist regimes, particularly those without independent judicial systems.

These developments have coincided with growing geopolitical tensions between Canada and China after the 2018 arrest of a senior Huawei executive following a US extradition request and Chinese retaliation against Canadian citizens and exports. These strategic concerns are reflected in subsequent Canadian FDI policy changes formalizing national security restrictions across multiple sectors including aerospace, biotech, intellectual property, critical minerals, critical infrastructure, and access to sensitive personal data (Canada, Citation2021). The result is growing formalization of a multi-tier system of investment regulation distinguishing between market-based investments (outside a few protected sectors) and state-controlled firms subject to levels of political guidance which raise significant concerns for national security.

Conclusion

This overview suggests that systemism can be a useful tool in visualizing cause and effect sequences, both in case study analyses, and in longer term dynamics shaping the interaction of international and domestic policies, even if it may condense contingencies from significant micro-level variables. Its broader utility comes in locating particular case studies within a longer trajectory of evolving investment and related trade policies to address their intermestic dimensions. Kingdon’s multiple streams model provides a useful, situationally flexible tool to bridge structural assumptions embedded in systemist analysis with the situational and contingent realities of domestic and bureaucratic politics.

The Mulroney government (1984–93) inherited an FDI regime oriented towards economic nationalism, emphasizing the “defensive” protection of domestically-focussed interests rather than the “offensive” pursuit of new market opportunities, even as both domestic and wider international political circumstances created unique opportunities for policy entrepreneurship and change (Bradford, Citation1998). The persistence of its incremental liberalization of domestic FDI policies, despite contestation, is attributable to their entrenchment within successive international trade agreements based on reciprocal obligation, if with significant “negative list” exceptions to accommodate competing domestic interests.

The “multiple streams” of these commitments and trade-offs remain central to Canada’s FDI and other international economic policies and to related public expectations. Residual effects of nationalist policies are visible in sectoral policies limiting foreign control over key sectors, and in the persistence of “net benefit” screening of larger market-based investments.

Broader efforts to integrate state capitalist regimes within this system, which complemented Canada’s historic efforts to diversify its trade and investment relations, fell short as limits to reciprocity progressively revealed system-level incompatibilities of market-based and authoritarian state capitalist regimes (Burton, Citation2015, pp. 177–82). These realities have been reinforced subsequently by growing strategic competition between the US and China. Canada’s initial response to these developments – the incremental application of national security rules, as provided for in international agreements – reflected growing uncertainties (and defensiveness) over a changing, unpredictable international environment, even before spillovers of growing great power competition led to successive unilateral US and Chinese actions affecting Canada.

National security screening processes in specific cases are necessarily opaque, not lending themselves readily to causal analysis. The same can be said for application of “net benefit” principles when institutional actors within or across governments are notably at odds. However, the increasingly public role in FDI-related issues taken by federal security advisors suggests significant internal policy contestation over conditions under which national security priorities should trump conventional economic processes.

Particular contingent actions or responses noted in the article which contributed to relative policy continuity or divergence, including the Competition Policy Review Panel of 2007–08, responses to the CNOOC-Nexen takeover, and the more recent spillover of US-Chinese strategic competition into trade and investment tensions between Canada and China, suggest that systemism is more likely to have explanatory than predictive value in addressing international economic policy issues subject to cross-cutting governmental interests. However, the evolution of a multi-tier approach to managing the multiple personalities of Canadian foreign investment policies has provided a more orderly process – if only in retrospect.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Geoffrey Hale

Geoffrey Hale is Professor of Political Science at the University of Lethbridge and author or co-editor of numerous books and articles on Canada's international economic policies.

Notes

1 A full background to, and explanation of, the contents of appears in the introduction to this special issue by Gansen and James.

2 The terms “strategic assets” or “strategic industries” have never been codified in Canadian foreign investment law, unlike European law. Some observers view their use as a rhetorical device to politicize FDI regulation – particularly when exercising bureaucratic discretion as with rules governing cultural, telecommunications and transportation industries (Assaf & McGillis, Citation2013, pp. 12–14).

3 Whenever two or more variables are on the same side of an arrow, these are separated by semicolons. For example, “X1”; “X2” → “Y” means that both X1 and X2 lead into Y.

References

- Aitken, H. G. A. (1967). Defensive economic expansion: The state and economic growth in Canada. In W. T. Easterbrook & M. H. Watkins (Eds.), Approaches to economic history (pp. 183–221). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Alexandroff, A. S., & Sharma, R. (2005). The national security provision: GATT Article XXI. In P. F. J. Macrory, A. E. Appleton, & M. G. Plummer (Eds.), The world trade organization: Legal, economic and political analysis (Vol. I, pp. 1571–1579). New York: Springer.

- Assaf, D. H., & McGillis, R. A. (2013, April). Foreign direct investment and the national interest. IRPP Study # 40. Montreal: Institute for Study of Public Policy. Retrieved December 23, 2020, from https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/research/competitiveness/foreign-direct-investment-and-the-national-interest/IRPP-Study-no40.pdf

- Beland, D., & Howlett, M. (2016). The role and impact of the multiple streams approach in comparative policy analysis. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, Research and Practice, 18(3), 221–227.

- Bliss, M. (1985). Forcing the pace: A reappraisal of business-government relations in Canadian history. In V. V. Murray (Ed.), Theories of business-government relations (pp. 106–117). Toronto: Trans-Canada Press.

- Boardman, A. E., & Vining, A. R. (2012, January). A review and assessment of privatization in Canada. SPP Research Paper 5, no. 4. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/boardman-vining-privatization.pdf

- Bow, B., & Lennox, P. (Eds.). (2008). An independent foreign policy for Canada? Challenges and choices for the future. Montreal-Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Bradford, N. (1998). Commissioning ideas: Canadian national policy innovation in comparative perspective. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Burton, C. (2015). The dynamic of relations between Canada and China. In D. Bratt & C. Kukucha (Eds.), Readings in Canadian foreign policy: Classic debates and new ideas (pp. 171–185). Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Canada. (2021, March 24). Guidelines on national security review of investments. Ottawa. Retrieved June 25, 2021, from https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/ica-lic.nsf/eng/lk81190.html.

- Competition Policy Review Panel. (2008, June). Compete to win: Final report. Ottawa: Industry Canada. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cprp-gepmc.nsf/vwapj/Compete_to_Win.pdf/$FILE/Compete_to_Win.pdf

- Gourevitch, P., & Shinn, P. (2005). Political power and corporate control: The new global politics of corporate control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hale, G. (2008). The dog that hasn’t barked: The political economy of contemporary debates on Canadian foreign investment policies. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 719–747.

- Hale, G. (2012). So near and yet so far: The public and hidden worlds of Canada-U.S. relations. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Hale, G. (2014). CNOOC-Nexen, state-controlled enterprises and Canadian foreign investment policies: Adapting to divergent modernization. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 349–373.

- Hale, G. (2018). Uneasy partnership: The politics of business and government in Canada (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Hale, G. (2022). State-owned and influenced enterprises and the evolution of Canada’s foreign direct investment regime. In J. Chaisse, J. Górski, & D. Sejko (Eds.), The changing paradigm of state-controlled entities regulation. New York: Springer, forthcoming.

- Hart, M. (2002). Canada: A trading nation. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Helman, C. (2012, July 16). The world’s 25 biggest oil companies. Forbes. Retrieved December 23, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/christopherhelman/2012/07/16/the-worlds-25-biggest-oil-companies/?sh=47bc120160ca

- Industry Canada. (2007, October 9). Creation of the competition policy review panel. Ottawa. Updated June 18, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cprp-gepmc.nsf/eng/h_00004.html

- Kingdon, J. W. (2011). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (updated 2nd ed.). Boston: Longman.

- Kobrin, S. J. (2004). Oil and politics: Talisman energy and Sudan. International Law and Politics, 36, 425–456.

- Kukucha, C. J. (2016). Canada’s incremental foreign trade policy. In A. Chapnick & C. J. Kukucha (Eds.), The Harper era in Canadian foreign policy: Parliament, politics, and Canada’s global posture (pp. 195–209). Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Manning, B. (1977). The congress, the executive and intermestic affairs: Three proposals. Foreign Affairs, 55(2), 306–324.

- Marchick, D., & Slaughter, A. (2008). Global FDI policy: Correcting a protectionist drift. CSR Report # 34. New York: Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/report/global-fdi-policy

- McClearn, M. (2005, August 29). Energy: Trouble in the pipeline. Canadian Business. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://www.canadianbusiness.com/business-strategy/energy-trouble-in-the-pipeline/

- Mintz, J. M. (2012, July 25). Limit state takeovers. Financial Post, FP15.

- Pfonner, M. R., & James, P. (2020). The visual international relations project. International Studies, 22, 192–213.

- Tomlin, B., Hillmer, N., & Hampson, F. O. (2007). Canada’s international policies; agendas, alternatives, and politics. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Trading Economics. (2020). Canada S&P/TSX Stock Market Index: 1979–2020. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/stock-market

- Vanderklippe, N., McCarthy, S., & McNish, J. (2012, December 10). Harper’s line in the oil sands. The Globe and Mail, A1.