ABSTRACT

Systemism as a method for the study of Canadian foreign defence policy offers an opportunity for fruitful collaboration across theoretical and methodological subdivisions in the field. In particular, the approach could provide an excellent method through which to showcase feminist causal logic for a more mainstream audience, which tends to view feminist scholarship as being far removed from its concerns and policy-relevant Canadian foreign policy. This review offers a somewhat idiosyncratic assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of systemism as presented in this special issue of CFPJ. I discuss how I see myself using sytemism as a writing and teaching tool in the future.

RÉSUMÉ

En tant que méthode d'étude de la politique étrangère et de défense du Canada, le systémisme offre l'opportunité d'une collaboration fructueuse entre les subdivisions théoriques et méthodologiques du domaine. En particulier, cette approche pourrait constituer une excellente méthode pour présenter la logique causale féministe à un public plus large, qui a tendance à considérer la recherche féministe comme étant très éloignée de ses préoccupations et de la politique étrangère canadienne pertinente. Cette revue propose une évaluation quelque peu idiosyncratique des forces et des faiblesses du systémisme tel que présenté dans ce numéro spécial du CFPJ. J'aborde la manière dont je me vois utiliser le systémisme comme outil d'écriture et d'enseignement à l'avenir.

As both a proponent of CFP and an inveterate whiteboard scribbler, I was immediately intrigued by the possibilities presented by the essays in this special issue. Although unfamiliar with the VIR (check) project before being invited to participate in this forum, I read James’ Citation2019 piece and found myself nodding “yes” throughout: yes to better ways of identifying causal arguments for grad students; yes to encouraging intra-disciplinary understanding by creating a common visual “language;” yes to encouraging “bricolage” as a way of freely-but-systematically incorporating seemingly-disparate arguments into one’s own work. In my current job, I teach courses incorporating IR and CFP to adult professional students, many of whom have little to no background in the social sciences or humanities. I am therefore always interested in learning new ways of conveying complex theoretical knowledge that don’t rely on assumed familiarity with the canon, or necessitate deep familiarity with “battle of the paradigm”-type debates.

So, what follows in this review is perhaps wholly idiosyncratic, and subject to the following caveats: what I teach and what I (mostly) write and read are themselves not perfectly locatable within academic IR; my workflow as professor-cum-student-cum-”lead parent” is somewhat disjointed and resistant to an organization, and; I have a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects the way in which I process and manage information, with a resultant mental toolbox of shortcuts and “hacks” that I’ve developed and which may or may not make sense to anyone else. I read the articles in this special issue first by looking at the accompanying diagrams, then by reading the papers with the diagrams open next to them. I considered each article both as a standalone “nugget” of visual information, and as an article accompanied by images. This review begins with where I think the utility of the method is most directly applicable. It then discusses what I see as drawbacks of the method as it was presented here, and finishes with an illustrative case from Canadian foreign policy as an example of how I might incorporate systemism into my own scholarship.

Strengths of systemism

The process of physically drawing a “causality flowchart” seems to me to be very useful in three specific scenarios: by an author, at the argument drafting phase; by students seeking to understand a causal argument in greater depth, and; by readers using the technique to either incorporate another’s argument (“bricolage”) or compare/contrast/critique competing explanations for the same phenomenon. Particularly for a subfield such as Canadian foreign policy, which is inherently interdisciplinary and also attracts a fair number of “one-off” scholarship from analysts outside the field (Boucher, Citation2020) using the VIRP systemism technique at the drafting stage could be a useful way of making sense of the interaction between system-, nation- and subnational-level variables and causality chains. The act of drawing these variables, and thereby mentally adjudicating their causal and physical “locations,” could contribute to a richer, better developed argument, regardless of on which level of analysis a scholar wished to focus. For example, if one wished to dissect the long-term effect of Trump on Canada–US relations, it is tempting to begin the story with Trump himself, and view he and his policies as being sui generis and exceptional. Even if one chose to begin their analysis with Trump, a better argument as to the long-term effect on our relations with the US would start with all the things that came before Trump, especially those variables which are systems-level or environmental, and whose effects we feel in Canada, too. Creating a “box” that describes “globalization” as the disciplining phenomenon that then produces “uncompensated losers from free trade” or “manufacturing decline” or “White deaths of despair” or whichever particular variable one wishes to focus on as a catalyst to Trump’s rise, we can more easily see that, while Canada has thus far escaped a similar populist fate (pace, Maxime Bernier), our country’s politics are subject to similar electoral pressures and thus similarly constrained in the range of acceptable political responses to Trumpist policies. This exercise acts as a sort of sea anchor on unintentional flights of causal fancy, forcing the author to pay closer attention to the causal chain underpinning their larger argument. “Seeing” an argument floating alone on paper can create a visceral moment of reflection, and force the identification of previously-unexamined “cryptocausal” assumptions. (more on this in the example, below).

For students, knowing an argument’s strengths and weaknesses is key to integrating a piece into a larger corpus of synthesized knowledge, such as one might create while preparing for comps or field exams. Although myself somewhat of slow adopter of technology, many “notes” apps already allow for the addition of detailed “tags” to assist students in the categorization of arguments. When combined with the visual systemization process, students could create categories of authors and theories by grouping them together first by the level of analysis, then by tagged causal chains: “anarchy,” or “balancing,” or “national unity” to give examples from IR and CFP. This itself could be a two-step analysis: the first pass would sketch out what the author describes as their argument, and the second could incorporate a student’s own critique, as well as prominent extant critiques, either of which might show another hidden or undertheorized causal chain, or challenge the original author’s causal claims directly.

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of systemism and the VIRP for me personally as a feminist scholar is the opportunity for constructive cross-field engagement afforded by the “bricolagic bridging” aspect of systemism. Both my research and my teaching practice have a foot in each of the “mainstream” and feminist defence and foreign policy communities, and I am frequently saddened by the extent to which the important insights of each subfield fail to penetrate the consciousness of the other. Some of this lack of dialogue is a function of “space:” different conferences, different journals, different scholarly networks, for example. Some of it is a natural outcome of different scholars choosing different microareas of focus. I would argue that a not-insignificant chunk of the divide, however, comes from a lack of familiarity with (or interest in?) the causal logic of feminist security studies, and a resultant difficulty in “seeing” how feminist arguments apply to “real issues”Footnote1 in practice. While the special issue revealed some difficulty in portraying critical or constructivist-type arguments in a way that reflected their complexity and gravitas, in the abstract, I believe that being able to display feminist empirical research in a mainstream vernacular could lead to it being incorporated more frequently into mainstream defence and foreign policy scholarship.

Weaknesses – as I perceived them

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the special issue for me was the inescapable tension between the necessity of having a standard lexicon of symbols and relationships with which to be able to compare causal claims, and the manner in which this lexicon taxed both the reader’s attention and the author’s ability to express an argument. For example, Henders’ article was one which, by my reckoning, ought to have been among the most useful examples of systemism, comparing as it did three separate, but related, aspects of border crossing as foreign policymaking. However, first contact with the figures accompanying the article almost put me off reading it altogether: in , each box had too many words in it and seemed to contain variables which themselves demanded precursor variables in order to be intelligible; the shapes and colors of the boxes were evidently meaningful, but I struggled to recall their meaning and couldn’t intuitively figure them out by their placement on the paper. (The subsequent figures, which presented a sort of timelapse of the argument, helped somewhat.) Unfortunately, it seems to be the most sophisticated arguments which are the most disadvantaged by the complexity of the visual lexicon: Young and Henders’s argument was the most compelling of those analysed in Henders’ article, and yet as a piece of visual information, it was far less descriptive than Leuprecht’s more simplistic causal story.

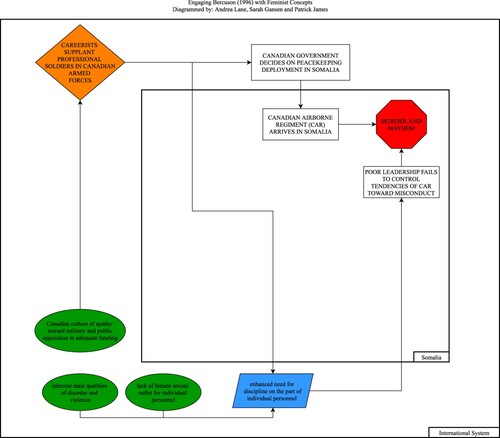

Figure 1. Engaging Bercuson (Citation1996) with Feminist Concepts Diagrammed by: Andrea Lane, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

Another related problem with the “visual lexicon” aspect (as presented in this collection, at least) is that the visualizations did not present the author’s argument-building process. For example, the lexicon allows for variables to be visually represented as having multiple potential pathways stemming from them, and yet in the diagram (and summaries) we aren’t privy to the usual scholarly weighing, choosing, and discarding of competing or alternative causal pathways. While I acknowledge that I have perhaps strayed beyond the “preservation/display” purpose of the VIRP more generally, being able to see an author’s deliberative process would be especially instructive, and could be accomplished in much the same manner as the arguments were presented here, in a series of sequential diagrams. Alternatively, as a solution to both problems, I propose that it could be useful to sacrifice uniformity and instead embrace technology to allow the pdf capture of authors’ own diagrammatic representation process. Using author’s own drawings – within some guidelines, lest chaos completely defeat the comparative goal – would allow readers to see how each scholar represents variables in space, how they view causality as flowing, which “branches” of arguments they prune as unhelpful, which variables are given more visual weight or heft, and so on. All these nuances would potentially greater insight into the arguments presented, and also mitigate against the confusing visuals that seem to result from more constructivist arguments such as those presented in Henders’ article in this collection.

Another aspect of the special issue I found challenging was in the requirement to “verbally” explain the pictorial representation of the argument in the accompanying article. As an illustration of the difficulty is Hale’s article in this collection. In Hale’s case, the visual representation (, for example) produced by the analysis is fairly easy to “read” and understand. The difficulty, however, is in reading the accompanying article, without which the “picture” is almost meaningless. The flow of his argument was greatly impeded by the necessity of representing micro and MACRO variables through typecase changes. While recognizing that this special issue serves to introduce systemism to the CFP audience, the difficulty of reading the “legend” text drove me to instead read the original articles discussed by Hale, so that I might better understand the arguments presented.

As a final critique – and one I freely admit is rooted in my own “level of analysis” preferences, rather than in the goals of the VIRP – I found that, in general, the amount of information that was presented in each diagram/series of diagrams was simultaneously too much and too little. Too much in that many of the diagrams were cluttered and difficult to parse, and too little in that the desire to present entire arguments did a disservice to authors whose arguments were dense and multifactorial. Mahant’s essay in this collection is an excellent example. While some of the variables presented were straightforward, such as “first democratic elections,” () others demanded their own causal chains in order that their impact could be properly understood: why did “Mbeki ha[ve] a more practical approach and value African-ness,” for example? And what does African-ness mean, in this context? The diagram, for me, posed more questions than it answered.

Opportunities – how would I use systemism?

As I wrote above, I feel there is real potential in systemism as a way of prompting deeper reflection both for authors, and for scholars wishing to incorporate and/or critique their work. Visually representing a causal chain at its naked, primordial stages, when the details are being worked out and the whole thing is messy and fluid, is for me where the utility of the method shines through. And using the method to sketch out another scholar’s causal claims is an excellent thought exercise, as it can readily expose where the strength and weaknesses are, and where the potential for “bricolagic bridging” might exist. It is in this spirit that I describe my own process of (semi)systemism, with the semi indicating the adaptations I have made to make the method work with my own cognitive quirks. As an illustrative case, I will be analysing the tacit causal claims underpinning the argument in David Bercuson’s Significant Incident, his Citation1996 explanation for the murder and misconduct in Somalia which lead to the eventual disbanding of the Canadian Airborne Regiment (CAR). I chose this example for two reasons: one, it is the most commonly-cited description of the Somalia events among my students, and its influences and logic are often heard in my classroom, and two, its causal argument diverges completely from the two most prominent feminist analyses of the Somalia scandal, namely Sherene Razack’s (Citation2004) Dark Threats and White Knights and Sandra Whitworth’s (Citation2004) Men, Militarism and UN Peacekeeping.

Bercuson’s explanation for the murderous conduct of the Airborne Regiment in Somalia lies at the societal level: he describes the murder of Somali teenager Shidane Arone as being “caused by the remarkable apathy Canadians have towards their military,” (Bercuson 239) with the intervening variable of the CAF “being choked to death by budget cuts” and bureaucratized by the NDHQ structure (Bercuson vi.) This societal neglect and bureaucratization, Bercuson argues, created a culture in the Canadian Army in which careerists supplanted “the warriors – the real professional soldiers.” (242). Careerists are bad leaders who tolerate poor discipline and create situations in which murderous misfits can gain the upper hand, according to Bercuson’s logic. I have written previously about the gendered connotations inherent in the “bureaucratization is killing the CAF” argument (Lane, Citation2017) but it is not Bercuson’s explicit causal argument I wish to analyse from a feminist perspective. Rather, it is the tacit, and unacknowledged, thread of feminist analysis running throughout Bercuson’s book that I wish to explore using systemism.

Throughout Significant Incident, Bercuson describes soldiers – and in particular, the paratroopers of the Airborne Regiment – as particular sorts of men, whose intrinsic warrior masculinity is palpable in their physicality, demeanor, and sex drive. As opposed to the pencil-pushing careerists emboldened by the NDHQ “tail,” “the fighting units of the army invariably consist of young and spirited soldiers who would be in need of discipline in any institution they were a part of.” (Bercuson 36) Indeed, such men are in Bercuson’s estimation wild, natural creatures whose leaders must “show them what the limits of acceptable behaviour are.” (37) Paratroopers in particular are “action-minded”(176) men, “the type of man who might otherwise seek adventure as mercenaries in foreign armies.”(180) As paratroop regiments are “made up of men who can be presumed to love soldiering for its own sake,” (176), “paratroopers join armies to fight.” (181)

Without the close attention of strong, almost brutal, leaders, paratroop regiments are prone to having “misfits” emerge, men whose natural vigor and high spirits are directed not at the pure love of soldiering, but at unsanctioned violence, crime, and excessive drinking. This indiscipline is explicitly linked by Bercuson to the maleness and masculinity of paratroopers themselves: “these men are usually young, intensely physical, and combative by nature, [thus] discipline is a problem.” (181). These “fighting” soldiers are described as “young, and bent on getting as much sex and booze as they could.”(54) Such behavior is to be expected, and “minor hell-raising in the line of duty could be overlooked,” especially on previous tours of duty to Cyprus, where “off-duty, they enjoyed the sun and the beer and the girls of the island.” (192). The paratroopers’ sex drive warrants multiple mentions in the book: Edmonton is described as being the perfect home for the CAR, because of its distance from Ottawa’s prying eyes, and because of “its many bars, restaurants and women” (198). By contrast, the march to murder begins when the CAR is made to move to Petawawa, a small town with “too few available women,” according to an army report cited without protest by Bercuson (209). Petawawa, Bercuson laments, offered “few places for high-strung young paratroopers to blow off steam after rigorous and demanding trainings.” (202)

The above passages are in some ways incidental to the causal explanation Bercuson presents in his book, but I have chosen them to describe what I view as “cryptocausality,” which I will present visually in , below. Bercuson has – perhaps unintentionally – echoed common feminist international relations arguments, those linking violence with masculinity, and military misconduct with male sexual entitlement. Bercuson alludes to the idea that the virility and energy of paratroopers “requires” female sexual outlet, and that women – and in particular wives – are required to keep the worst of soldiers’ instinct in check. Young men as inherently violent, over-sexed carousers is in fact the first, unacknowledged step along Bercuson’s causal chain – why else would desultory or lax leadership have such grievous consequences? This proto-explanatory step actually places Bercuson’s causal explanation for the CAR’s misconduct in Somalia much more in line–albeit unwittingly, and, one presumes, unwillingly – with Razack and Whitworth’s arguments, which view the violence as rooted in the racist, patriarchal license given soldiers on peacekeeping missions in particular.

So what?

This brief sketch of how I would use systemism is intended to show how a visually-facilitated critique of a “conventional” defence policy argument could potentially build bridges with feminist analyses. Understanding how conventional arguments sometime rest on sex and gender as “cryptocausal” foundations offers an important starting place towards a more fruitful conversation between what I regret still seem to be two solitudes within the study of Canadian foreign and defence policy. While there might still be areas of great disagreement, it would be helpful to recognize at least that feminist and mainstream scholars can discuss common issues using a common (visual?) vocabulary.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Lane

Andrea Lane is a strategic analyst with DRDC-CORA, and a PhD candidate in political science at Dalhousie University.

Notes

1 I am of course using “real issues” ironically, because I believe that issues of sex and gender in defence and foreign policy are both materially real and important.

References

- Bercuson, D. (1996). Significant incident. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Boucher, J.-C. (2020). Canadian foreign policy networks: Scholarship collaborations 2006-16. In B. Bow, & A. Lane (Eds.), Canadian foreign policy: Reflections on a field in transition. Vancouver: UBC Press, 68–97.

- James, P. (2019). Systemist international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 63, 781–804.

- Lane, A. (2017). Special men: The gendered militarization of the Canadian armed forces. International Journal, 72(4 ), 463–483.

- Razack, S. (2004). Dark threats and white knights. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Whitworth, S. (2004). Men, militarism and UN peacekeeping. Denver: Lynne Reiner.