ABSTRACT

In order to improve visual communication of disaster research, this article provides a systemist visual representation of the cause and effect relationships, trends, and logical impacts of different pieces in the field of Canadian disaster risk reduction and corresponding policy decisions on assistance. Three studies are included. These works focus, in interconnected ways, on resilience, governance, and related factors vis-à-vis Canadian disaster risk reduction. In carrying out this graphic analysis, the article highlights areas of crossover as well as fruitful directions for future learning to further develop and improve the decision-making process and Canada’s efforts to reduce the risks of disasters. Work proceeds in six sections. The first section provides an overview of the project. Sections two through four create systemist visualizations of the respective studies. The fifth section engages in systematic synthesis based on the preceding graphics. Sixth, and finally, conclusions are offered, along with a few ideas about future research.

RÉSUMÉ

Afin d'améliorer la communication visuelle de la recherche sur les catastrophes, cet article offre une représentation visuelle systémiste des relations de cause à effet, des tendances et des impacts logiques de différents éléments dans le domaine de la réduction des risques de catastrophes au Canada et des décisions politiques correspondantes en matière d'assistance. Trois études sont incluses. Ces travaux se concentrent, de manière interconnectée, sur la résilience, la gouvernance et les facteurs connexes en ce qui concerne la réduction des risques de catastrophes au Canada. En procédant à cette analyse graphique, l'article met en évidence les points de recoupement ainsi que les orientations fructueuses pour l'apprentissage futur afin de développer et d'améliorer le processus décisionnel et les efforts du Canada pour réduire les risques de catastrophes. Six sections composent l'article. La première section offre un aperçu du projet. Les sections deux à quatre créent des visualisations systémistes des études respectives. La cinquième section s'engage dans une synthèse systématique basée sur les graphiques précédents. La sixième et dernière section offre des conclusions, ainsi que quelques idées sur les recherches futures.

Overview

Increasingly, information about disasters is visual: video, images, and illustrations shape the framework for action, including the perception of risk, vulnerability, and response. The visual nature of information has also impacted researchers seeking to communicate their findings. Following these trends, the London School of Economics “Impact Series” of blogs has emerged as a “best practices” guide for researchers on communicating social science research to the public and policymakers. The importance of visual communication is an ongoing theme of the “Impact” blogs; for example, Hadley Wickham comments on the visual elements of data science and the importance of visualization in communicating statistics (Wickham, Citation2014).

In searching for the “value added” that a visual communication of key research findings can provide, this article will create and analyze graphic depictions of three articles on disaster risk reduction and assistance. By providing a clear visual representation of the cause–effect relationships, conceptual trends, and logical impacts, this work will be able to illuminate areas of crossover and fruitful policy-relevant directions for future learning regarding disaster risk reduction and assistance. Conclusions will centre on the new insights and potential contribution of visual communication of research for Canadian foreign policy decision making.

Global disasters are affected by trends in communication. In an age of potential “mega-crises” amplified by complexity and global scale, the possibility for “information super storms” to derail policy and disaster response is apparent (Helsloot, Boin, Jacobs, & Comfort, Citation2012, p. 16). The need for research that links together disaster risk reduction, good governance, and techniques for effective communication is clear.

Responses to disasters often are dominated by short-term and instrumentalized thinking or feed preconceived notions and images of disaster risk that is removed from facts on the ground and so can lead to policy missteps. Hazards can develop into disasters when researchers discount the need for effective communication about risks, vulnerabilities, and responses. Recently, the global pandemic has highlighted the importance of strong, clear communication in order to affect peoples’ interpretation of risks and build trust in leadership (Richard Eiser et al., Citation2012). Even as valuable knowledge of the sources and effects of disaster risk has become more refined and policy-focused, the ecosystem of information has at times outstripped the ability of researchers to communicate their findings effectively. In response, efforts to improve the communication of research findings can assist in decision making, as well as improve the quality of research communication, and hence public understanding of the sources of disaster risk and the means of disaster risk reduction.

Recent work in disaster risk reduction by international organizations and the scientific community has shifted toward a broader view of risk, vulnerability, and resilience that explicitly incorporates concerns with societal factors in the preparation for, and response to, disasters. The increasing prominence of disaster risk governance as a concern in the Sendai Framework is a product of decades-long discussions around the nature of risk, the role of human and societal factors in contributing to disasters, and a critique of dominant “technocratic” approaches to disaster risk reduction in the literature (Haque & Etkin, Citation2012, p. 7) As described by Eiser et al., “understanding the historical and political processes that create and maintain … vulnerabilities is absolutely central to an explanation of disasters” (Citation2012, p. 6). Moving away from the framing of “natural disasters” toward “systemic risk” has led both practitioners and academics in disaster management to centre institutional cooperation, disaster risk governance, and communication.

In line with the work of James (Citation2019) and the Visual International Relations Project (VIRP), graphical depictions of research work in International Relations can improve communication across disparate and complex theoretical paradigms, as well as identify potential areas of linkage, dialogue or synergy. In the case of disaster risk reduction, the need for coordinated action suggests a premium for knowledge sharing and effective communication to identify areas of vulnerability, exposure and hazards. Canadian foreign policy decision-makers will likely find value in theoretical and policy work that can effectively capture areas of need, gaps in knowledge, or linkages between otherwise distinct bodies of research. As the field grows in complexity and scope, with rapid changes and radical shifts in global forces, clarity of communication is likely to be more highly valued by academics and practitioners alike. As well, graphical depiction of problems can aid in constructing new knowledge by creating a “flash-like insight”. As stated by Kramer and Ljungberg, “the visual arrangement of a figure shows something that is itself not contained and not even articulated in the constructive rules of the figure. Thus, an informative cognitively added surplus value emerges” (Krämer & Ljungberg, Citation2016, p. 8).

In line with the respective objectives of systemist visualization, diagrams can reveal a degree of consensus around a research question or, in this case, a particular issue or set of challenges posed for decision making. The general agenda of the articles analyzed here is the problematic of disaster risk reduction, “a systematic, whole-of-society approach to identifying, assessing and analyzing the causal effects of disasters and reducing the risks and impacts of disaster based on risk assessments” (Public Safety Canada, Citation2018). Disaster risk reduction as a policy issue originates in the international regime defined by the Hyogo and Sendai Protocols, which over time have evolved and been refined in ways that impact Canadian foreign policy decision making. As mentioned above, the current trends in disaster risk reduction toward a focus on disaster risk governance provide a timely opportunity to revisit findings using a systemist graphical depiction to identify key trends and gaps. These trends, relationships and their logical impacts provide the focus of this comparative study, with systemist visualization offering a means for identifying areas of consensus as well as gaps that might prompt new inquiries. below illustrates the systemist notation used to develop the analysis.Footnote1

Table 1. Systemist notation.

Resilience or relief: Canada’s response to global disasters

Published in 2013, the main argument of the first article is that Canada’s disaster response should pay greater attention to the need for resilience, as framed in the international regime of disaster risk reduction (Warner, Citation2013). Resilience-oriented assistance is tasked with helping communities to reduce vulnerabilities and risk, by preparing for future disasters. Although it is not incompatible with relief, an orientation of resilience does contrast with one of relief in terms of the allocation of resources, the involvement of local authorities, and the underlying purpose of disaster response. Canada’s response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti is used to analyze the way in which disasters are framed in Canadian foreign policy, the way in which competing frames affect the provision of disaster assistance, and the effects of this framing on the recipients of disaster assistance (Warner, Citation2013).

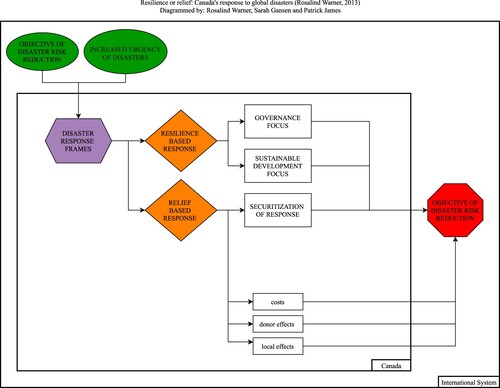

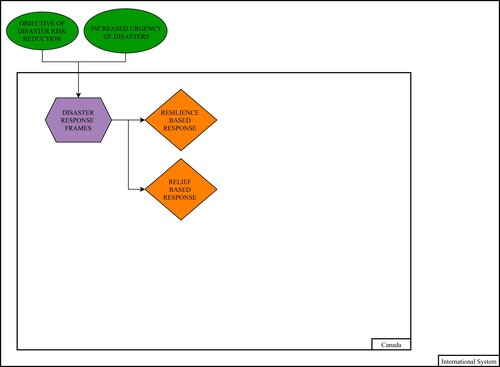

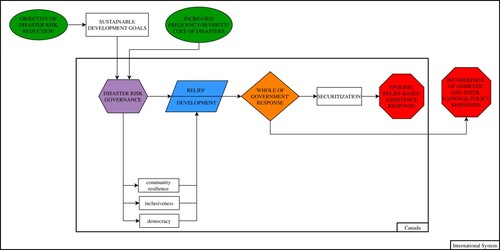

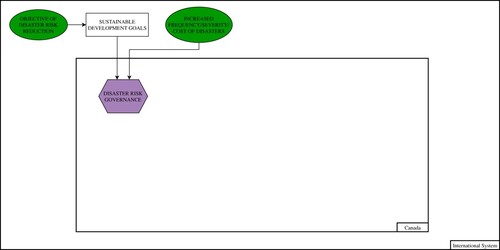

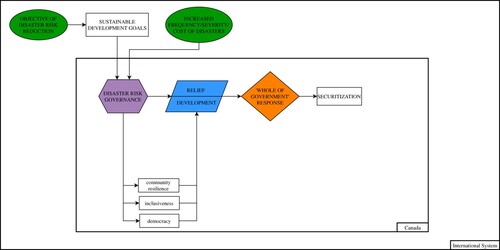

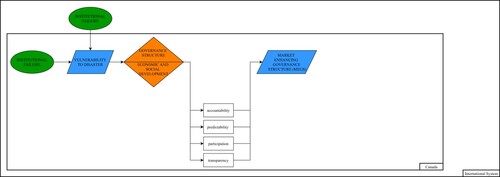

displays this article in a systemist graphic form. The international system forms the environment within which a Canadian system operates, and it impacts Canadian foreign policy decision making in particular ways.

Figure 1. Resilience or relief: Canada’s response to global disasters (Warner, Citation2013). Diagrammed by Rosalind Warner, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

There are a total of 12 variables in play, organized into 9 macro and 3 micro levels, with 3 macro variables operating in the international system, and 6 macro and 3 micro variables operating within the Canadian system. The macro variables within Canada are distinguished from the micro variables by their level of visibility in the causal relationships analyzed. In general, micro variables represent societal ones, while macro variables operate at the level of state structures.

The types of connections between and among macro and micro variables include all four basic types of linkages. Two variables are initial, one is nodal, depicting multiple pathways and linkages, two are divergent, depicting multiple pathways arising from a single connection, three are macro generic, three are micro generic, and there is one terminal.

shows Canada as the system and the international system as its environment. As depicted in , there are two initial variables, indicated as green ovals: “OBJECTIVE OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION” and “INCREASED URGENCY OF DISASTERS”. Both variables arise from the international system and impact upon Canada by connecting to the nodal variable of “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES”, depicted as a purple hexagon, which incorporates multiple pathways and linkages, as depicted in . “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES” are constructed in the process of developing policy responses to the environmental variables, and so incorporate “OBJECTIVES OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION” and the initial trend of “INCREASING URGENCY OF DISASTERS”.

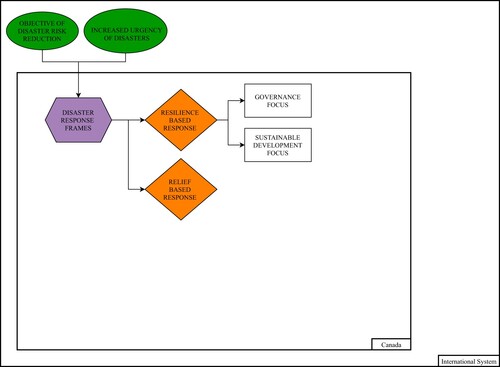

then introduces two new divergent variables arising from “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES”: “RESILIENCE BASED RESPONSE” and “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE”. These two variables are divergent, indicated by orange diamonds, because they initiate multiple pathways created by the single linkage of “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES”. Relief-based responses are exemplified in the article by Canada’s pattern of allocating resources to security and the military in the response to the Haitian earthquake, while resilience-based responses are exemplified by the work of organizations like Partners in Health and Fonzoke which focused on longer-term and local resilience (Warner, Citation2013, p. 232).

Here the logical mechanism is evident: environmental variables are impacting upon Canada by leading to the creation of “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES” that generate separate possible pathways for disaster response and therefore impact upon the shape of disaster assistance policies. Resilience and relief-based responses are not mutually exclusive but their contrasting implications are important to the argument. As described in the article, the contrast between the two frames is evident in the “allocation of resources, the involvement of local authorities, and the underlying purpose of disaster response” (Warner, Citation2013, p. 233). The contrast between “RELIEF-BASED RESPONSE” and “RESILIENCE-BASED RESPONSE” is then exemplified in the article through the case of Haiti, where vulnerability to disasters continues to persist, despite Canada’s comprehensive disaster assistance response to the earthquake of 2011.

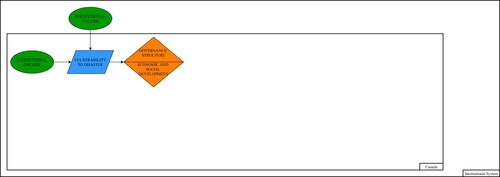

The contrast between disaster response frames is further developed when additional variables are added. depicts a new connection, between “RESILIENCE BASED RESPONSE” and two additional generic variables, “GOVERNANCE FOCUS” and “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT FOCUS”. “RESILIENCE BASED RESPONSE” leads directly to “GOVERNANCE FOCUS”, which incorporates “the institutional or structural features that impact the society’s vulnerability” (Warner, Citation2013, p. 233). “RESILIENCE BASED RESPONSE” also leads to a “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT FOCUS”, which means resisting a strict separation of disaster response from development and the “incorporation of risk reduction … into sustainable development assistance” (Warner, Citation2013, p. 225).

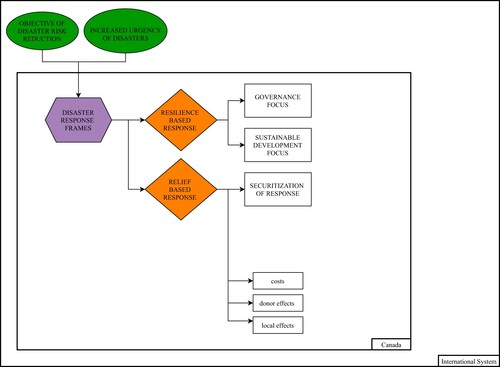

introduces four additional variables to provide further nuance to the argument, the macro variable of “SECURITIZATION OF RESPONSE”, and three micro variables of “costs”, “donor effects”, and “local effects”. All four of these variables are generic, and follow from the divergent variable “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE”. “SECURITIZATION OF RESPONSE” is a more visible trend variable arising from the divergent variable “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE”. “SECURITIZATION OF RESPONSE” is described on p. 226, which portrays the connection between “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE” and “SECURITIZATION OF RESPONSE” this way: “when framed in terms of relief and provision of basic emergency needs, disaster responses are also vulnerable to becoming inordinately focused on security threats” (Warner, Citation2013, p. 226).

Also in , the micro variables emerge from “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE” and are associated with less visible effects of that divergent variable. For example, local effects of a “RELIEF BASED RESPONSE” include the displacement and delegitimization of governing authorities in disaster response, costs include potential misallocation of resources, and donor effects include donor fatigue (Warner, Citation2013, p. 225).

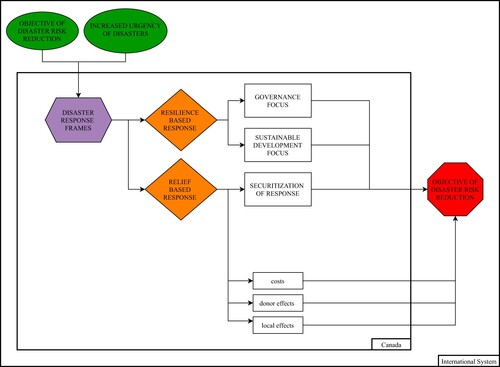

brings the argument full circle to the terminal variable, “OBJECTIVE OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION”, which appears as a red octagon. At this point, variables converge after following their respective separate pathways. The causal line between the two divergent variables and the corresponding pathways they produce is clear, as the pathways affect Canada’s response in the context of the international system, from which the impetus of disaster risk reduction also emerges. Ultimately, the effects of Canada’s response to “DISASTER RISK REDUCTION” and “INCREASED URGENCY OF DISASTERS” can be traced back to the “DISASTER RESPONSE FRAMES” that shape the various micro and macro policy options and responses with Canada.

Depicting the article using systematist notation facilitates an interpretation of the articles’ concepts and argumentative conclusions. The argument progresses from the “outside-in”, starting with the influence of the environment on decision making by the Canadian state. Using the concept of disaster frames to “filter” the effects of the environment on policy outcomes helps to simplify the range and complexity of variables and their role(s). It also emphasizes the divergent comparative effects of disaster frames on the overall goal of disaster risk reduction. One conclusion of the article, that relief-based responses to disasters tend to have little effect on pre-existing vulnerabilities, is reinforced. The gaps in disaster response to the Haiti earthquake, namely the tendency to favour relief-based rather than resilience-based policies, are more easily identified using the graphical depiction, which also reveals the important linkages between governance and sustainable development, and shows these as a “refinement” of the rather broad concept of resilience.

Governance for resilience: Canada and global disaster risk reduction

The second article, published in 2019, addresses similar themes to the first with different emphases and a more defined and detailed discussion of governance in disaster risk reduction. The purpose of “Governance for Resilience” is to capture the impact and implications of international developments in Disaster Risk Reduction on Canadian foreign policy planning, decision making, and institutional responses (Warner, Citation2019). In general, the article argues that a broadening of the international community’s normative and institutional frame of DRR has notably moved toward the concept of “resilience” and community transformation, as reflected in the Sendai Framework (distinguished from earlier DRR agreement the Hyogo Protocol). This trend has specific implications for Canadian decision making, requiring a more sustained examination of the concept of disaster risk governance both domestically and internationally. Similarly to the first article, “Governance for Resilience” seeks to explore the blurring of development and disaster response activities, but does so in the context of Canada’s more robust support for the Sendai Framework, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the incorporation of resilience principles into policy making.

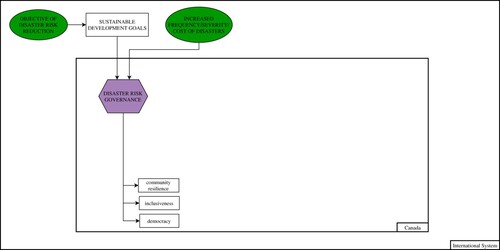

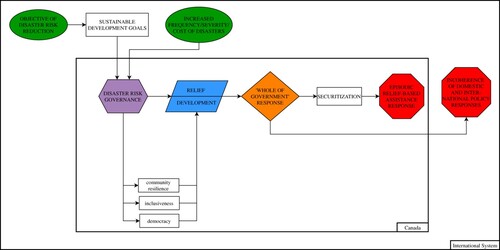

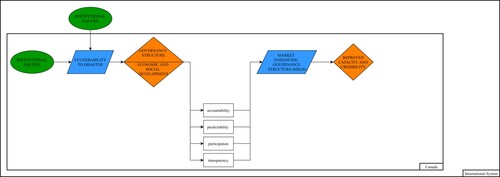

displays the article in systemist graphic form. There are a total of 12 variables in play, organized into 9 macro and 3 micro levels, with 4 macro variables operating in the international system (two as initial, one generic and one as a terminal variable). There are five macro and three micro variables operating within the Canadian system. As with the first article, the micro variables operate at the societal level, while macro variables operate at the level of state structures.

Figure 2. Governance for resilience: Canada and global disaster risk reduction (Warner, Citation2019). Diagrammed by Rosalind Warner, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

The types of connections between and among macro and micro variables include all four basic types of linkages. Two variables are initial, one is nodal, depicting multiple pathways and linkages, and two are convergent, with a single pathway created from multiple linkages (composed of a co-constitutive variable). One is divergent, depicting multiple pathways arising from a single connection, five variables are generic, and two are terminal.

As depicted in , Canada operates within the context of an international system, which impacts its operations in complex ways and creates unique inter-linkages and interactions across the levels that are important to understanding disaster response. adds the green oval (initial variable): “OBJECTIVE OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION”, which has changed in its relationship with other international variables due to the adoption of the UN’s “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS” as a generic variable, depicted in . Adoption of the SDGs in 2015 within the UN system was embraced by the Canadian government, and while the exact relationships between the international variables are still being shaped to this day, the anchoring of Canadian decision making to international norms and institutions is a key consideration for policy that underpins both articles. “INCREASED URGENCY OF DISASTERS”, an initial variable that appears as a green oval in , remains as a longer-term trend arising from the international system but operates independently in its impact on the Canadian system.

Both initial variables arise from the international system and impact upon Canada by connecting to the nodal variable of “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE”, a purple hexagon, which incorporates multiple pathways and linkages, as depicted in . “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE” is a nodal variable with multiple macro connections, micro connections, and causal linkages, and so occupies a central place in the analysis. The centrality of “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE” is explained in the article this way: “Disaster risk governance can be considered a distinct dimension of the broader goal of DRR, with a characteristic shift toward resilience-based rather than relief-based governance and assistance models (2)”. “Resilience or Relief” outlined the tension between these two competing “frames” and the impact of this for disaster response. “Governance for Resilience”, in line with international trends, moves the analysis toward elaboration of a resilience-based conception of governance.

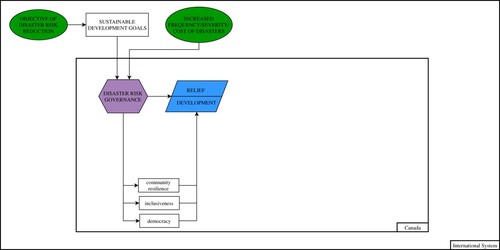

elaborates three additional connections to the micro level from the nodal variable of “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE”: “community resilience”, “inclusiveness”, and “democracy”. This move is supported by disaster assistance literature and by a reading of the treatment of “governance” in the Sendai Framework. These micro variables operate at the level of the society, but have implications for a whole-of-government response, as indicated by the connections to the convergent variable “RELIEF|DEVELOPMENT” that appears in .

“RELIEF|DEVELOPMENT” is a convergent variable, indicated by a blue parallelogram, due to its role in creating a single pathway from multiple connections. “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE” impacts the “RELIEF|DEVELOPMENT” variable both directly and indirectly, through the micro variables of “community resilience”, “inclusiveness”, and “democracy”. This depiction describes visually a set of complex interactions across societal and state levels. The “RELIEF|DEVELOPMENT” dichotomy is potentially both sharpened and blurred, impacted by the pathway (MACRO or micro) one takes to arrive there. This tension is addressed in the article in this way: “While the language of the Sendai Framework in regard to disaster risk governance incorporates references to risk, losses, and implied fragility on the one hand, it also includes goals of resilience and development on the other hand” (Warner, Citation2019, p. 334). As a co-constitutive variable, “RELIEF/DEVELOPMENT” appears in a shared space.

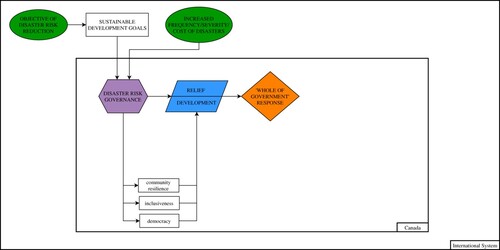

The convergent variable “RELIEF|DEVELOPMENT” combines the micro and micro variables to produce a single connection to the “WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT” response, the next step shown in . As a divergent variable, “WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT” takes the form of an orange diamond. From here the graphic moves, in , toward “SECURITIZATION”, a generic variable that is discussed in the article at some length. In sum, the article argues that “SECURITIZATION” is a variable to be considered that emerges from a “WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT” response, but that, as stated: “the approach of the DRR framework is wider and deeper in its (admittedly light) rendering of disaster risk governance as a result of the deliberate blending of relief and development activities, and its focus on strengthening resilience, which is a much more central goal of DRR than humanitarian assistance per se” (Warner, Citation2019, p. 335).

adds the article’s findings, in the form of two terminal variables. The diagram indicates the extent to which the generic variable of “SECURITIZATION” connects with the terminal variable of “EPISODIC RELIEF-BASED ASSISTANCE RESPONSE”, a reiteration of the findings of “Resilience or Relief”. Going further than “Resilience or Relief”, the findings of “Governance for Resilience” are elaborated at the international level and the level of the Canadian system, in order to portray the terminal variable of “INCOHERENCE OF DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL RESPONSES”. Both terminal variables are depicted as red octagons.

In the end, then, there are two key contrasts noted in the article. Having journeyed through the initial variables (green ovals) of “OBJECTIVE OF DISASTER RISK REDUCTION” and the likely increased frequency, severity and costs that contribute to the urgency of disasters, the “WHOLE OF GOVERNMENT RESPONSE” that results is characterized by an outsized focus on relief rather than resilience.

The second key contrast noted is between domestic and international responses, the former being more informed by disaster risk governance than the latter. Finally, the article concludes, “A closer reading and more conscious application of the disaster risk governance components of the Sendai Framework can positively contribute to the longer-term effectiveness of these efforts by refocusing humanitarian assistance on the need for development and community resilience, similar to the ways that Sendai is being applied in the Canadian domestic context within Public Safety Canada” (Warner, Citation2019, p. 342).

In this article, the use of systemist notation allows the reader to identify and contrast the “inside” and “outside” factors affecting Canadian policy. The graphical depiction also centres on the nodal variable of “DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE”, a rich concept which captures key institutional and ideational features of the international regime of Disaster Risk Reduction (particularly the goals of community, inclusiveness and democracy). Depicting Relief and Development as a Co-Constitutive Variable captures the contingency of these goals on one another without implying the dominance of either one. This idea of a co-constitutive variable can be difficult to explain in a narrative. In practice, disaster response aimed at immediate relief can impact development (negatively or positively) and vice versa. Funding food airlifts and setting up field hospitals can practically impact development efforts to produce food locally or improve the provision of healthcare to communities. At the same time, and more conceptually, seeing these as contingent implies that, for example, “relief” takes on a different meaning when contextualized by “development”, than when it is considered on its own. In other words, relief-based responses to disasters do not occur in isolation, without some relationship to prevailing institutions, policies, and ideas surrounding “development”. The focus shifts to the relationship between the two variables rather than the discrete impact of each on policy decision making. For example, food airlifts and field hospitals would make little sense as responses to the widespread slum conditions in Haiti’s urban areas prior to the earthquake, but the implications of the latter (prevailing conditions of poverty and hunger) on disaster risk reduction are equally important to consider when analyzing disaster response. In the conclusion, the article asks the reader to consider the relationships between these variables and their complex impacts on one another, rather than to analyze them in isolation.

The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management

Analysis here represents one interpretation of the argument in (Ahrens & Rudolph, Citation2006) “The Importance of Governance in Risk Reduction and Disaster Management”, which appeared in the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. As described in the abstract, the goal of the article is to identify institutional failure as a source of vulnerability and to identify specific aspects of governance (accountability, participation, predictability and transparency) that can further the goals of development and disaster risk reduction (Ahrens & Rudolph, Citation2006). The diagrams here are not meant to displace the already-existing graphical depictions contained in the article itself, which are highly precise in elaborating the argument; however, it is meant to interpret the article in the terms and vocabulary established by the VIRP (Visual International Relations Project) as a means of “translating” findings. The purpose of including a third paper on a similar topic is to identify areas of crossover and potentially fruitful subjects of further study that might not be apparent using traditional methods of analysis. This article expands the subject beyond the immediately narrow focus on Canadian foreign policy to explore insights from the disaster risk reduction literature as it straddles domestic and international realms, something that has obvious relevance for Canadian foreign policy studies. The paper also adopts an explicitly comparative and conceptual focus, using and developing concepts (disaster management, governance) that are referenced in the later papers, and which continue to have salience in the field of studies of disaster risk reduction. Part of the underlying argument of the first two papers is that the broader study of disaster risk reduction, and the international processes which are analyzed by that literature, are especially relevant for Canadian foreign policy, so this third paper makes that link more explicit.

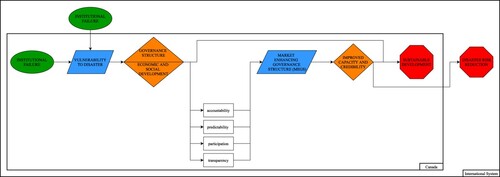

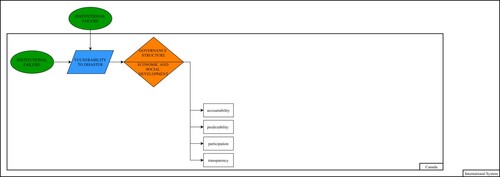

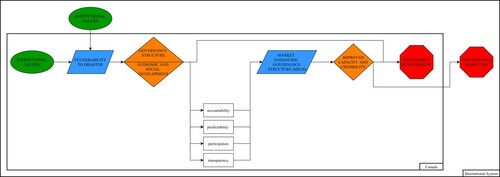

conveys a systemist visualization of the third paper. In “The Importance of Governance”, there are also a total of 12 variables in play, organized into 9 macro and 3 micro levels, with 4 macro variables operating in the international system (2 as initial, 1 generic and 1 as a terminal variable). There are five macro and three micro variables operating within the domestic system. As with the first two articles described above, the micro variables operate at the societal level, while macro variables operate at the level of state structures.

Figure 3. The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management (Ahrens & Rudolph, Citation2006). Diagrammed by Rosalind Warner, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

The types of connections among macro and micro variables include three basic types of linkages, excluding the nodal type. Two variables are initial, two are convergent, with a single pathway created from multiple linkages, and two are divergent (composed of one co-constitutive variable and one divergent variable). Four micro variables are generic, and two are terminal (one macro and one micro).

As depicted in , the domestic system is depicted as operating within the context of the international system; however, the bulk of the analysis is implied to operate domestically. Interestingly, the initial variable (green oval) is depicted in as operating at both domestic and international levels, in the form of “INSTITUTIONAL FAILURE”. Thus the initial variable for the logic of the paper is understood to be operating at both domestic and international levels.

As seen in , the “INSTITUTIONAL FAILURE” at both levels lead to “VULNERABILITY TO DISASTER”, which is consequently depicted as a convergent variable (blue parallelogram) arising from the action of those two initial variables. adds the divergent variable of “GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE|ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT” as an orange diamond. Note the co-dependent nature of the duality of governance and economic and social development, which share the visualization of this variable. This dual variable then is specified in terms of the four micro variables – “accountability”, “predictability”, “participation” and “transparency” – in , which are connected to both. Those variables, in turn, are connected with a second convergent variable, “MARKET ENHANCING GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE” (or MEGS as it is termed in the article), depicted as a blue parallelogram in .

adds the resulting second convergent variable of “IMPROVED CAPACITY AND CREDIBILITY”, which is deemed to be an outcome of the preceding. This variable, in turn, follows through in to the terminal macro variables of “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT” (domestically) and “DISASTER RISK REDUCTION” (in the context of the international system). Each of these terminal variables appears as a red octagon.

Similarly to the above two articles, the benefit of using systemism to depict the variables and their relationships in this article is the depiction of relationships as well as causal forces and factors described in the argument. In this case, vulnerability emerges as an important convergent variable that is a consequence of institutional failure and, in turn, impacts governance structures and economic and social development negatively.

Systematic synthesis of the three articles

The method of visual and graphic depiction of studies in Canadian foreign policy is meant to improve clarity (and by extension, understanding), to illustrate relevance and linkages where they might not be apparent, to identify gaps, and to work toward completeness and coherence in analysis. The broad problematique of the three articles is how can institutions, policies, and values work to reduce disaster risk? Each article goes about this problem in different ways and offers different syntheses and connections. “Resilience or Relief” argues that institutions, policies and values intersect to favour relief-based disaster responses that incur costly imbalances, while alternatives like resilience-based responses can improve outcomes while clarifying purposes of disaster response. “Governance for Resilience” argues that the mismatch between domestic and international trends in disaster risk governance has hampered the full development of resilience-based responses to disaster risk. “Disaster Risk Governance” argues that attention to governance can assist efforts to reduce disaster risk and vulnerability. The three articles complement each other by building out different aspects of the arguments around disaster risk reduction and assistance.

A number of observations can be made from the diagrams that might not be apparent even on a close reading of each article:

The linkage between “GOVERNANCE” (understood variously as a feature of institutional arrangements, societal values, and/or policy frames) and “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT” (either as a set of values/outcomes or as an institutional regime) is central to the logic of all three diagrams. Whether as an outcome of a disaster frame focused on resilience rather than relief (“Resilience or Relief”), whether as a nodal variable with complex implications for policy responses (“Governance for Resilience”), or whether as a variable with the potential to be divergent or convergent (depending on its specific forms) as in “Governance in Risk Reduction”; “GOVERNANCE” and “SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT” have close, sometimes interdependent implications in disaster risk reduction and responses.

The three diagrams spark an implicit conversation about the relationship between values (inclusiveness, democracy, transparency, participation, accountability, predictability, transparency, resilience), and institutions (governmental structures, capacities, resources, procedures), and the policy effects of this relationship. At times, governance as a factor in disaster risk reduction appears as a bundle of values and goals, either at the societal or state level. At other times, governance appears as primarily institutional or legal arrangements. What are the implications of considering governance as value-based or as institution-based? This question could also arise as one for policy decision-makers: to what degree do current policies lean toward notions of governance as value-based or as institution-based, and how might policies need to change to incorporate a more complete picture of governance?

The diagrams also highlight the operation of different variables at different levels. In particular, the state and the international levels are key areas suggesting a need for further study of how the initial and terminal variables play out domestically and internationally.

Conclusions

In an increasingly complex and interrelated world, Canadian foreign policy decisions are impacted by a multitude of information sources of varying quality and impact. Communicating research visually can cut through the noise and provide clarity as well as help to identify new connections and gaps in knowledge that might otherwise be hidden. As the articles on disaster risk reduction suggest, rapid response to disasters makes sense in light of the urgency of meeting human needs, and is expected and embraced by the Canadian public. The ability to convey knowledge visually can contribute to the effort to communicate the need for disaster risk reduction and increased resilience. While not necessarily aimed at public communication of disaster risk reduction, systemist diagramming can bring out connections and trends that may impact the ability of the Canadian state and society to prepare and respond to disasters. Diagrams can assist by helping decision-makers to not only cognitively interpret research and construct new knowledge, but also to “know what to ignore” (Krämer & Ljungberg, Citation2016, p. 9).

Using diagrams to convey knowledge about disaster risk reduction can improve policy decision making in specific ways. Diagrams can aid in the formation and design of new institutional frameworks within the Canadian government for disaster response and risk reduction. New institutional frameworks then can shape responses that are cognizant of the importance of governance, resilience, and sustainable development in disaster risk reduction over the longer term. Such frameworks could also be made more responsive to Canada’s international obligations under the Sendai framework and may help to maintain coherence between domestic and international disaster risk reduction efforts.

Diagrams also can identify areas of need and gaps in resource allocation. For example, a theme emerging from the above diagrams across the three articles is the potential for “SECURITIZATION” to emerge from particular frames and in the context of responses to disasters such as the Haiti earthquake. While not always inappropriate, the connection with “EPISODIC RELEF-BASED RESPONSES” suggests that disaster response spending can be re-cast in terms of preventive and longer-term risk reduction efforts rather than disaster management or relief spending, which may be more securitized. In alignment with the efforts of development partners and the principles of disaster risk governance, such efforts may be more cost-effective in reducing human and financial losses from disasters.

While graphic depictions of Canadian responses to disaster risk reduction are unlikely to reduce the tendencies to respond to information in “realtime”, using diagrams can synthesize and interpret research findings in ways that can improve the impact of research on policy. As well, although there may be downsides to engaging with “visual culture”, systematized diagrammatic visualization of policy ideas and arguments can effectively counter the tendency to incoherence in the information ecosystem by improving clarity and facilitating logical and deliberative discourse that reflects on the relevant variables and their interrelationships.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rosalind Warner

Dr. Rosalind Warner is Continuing College Professor of Political Science at Okanagan College. Her research interests include Canadian foreign policy, ethics and international relations, global environmental politics, ecological modernization and human security. Publications include: “Governance for Resilience: Canada and Global Disaster Risk Reduction”. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 2019, 1-15; “Resilience or Relief: Canada's Response to Global Disasters” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 19:2 (2013) 223-235; “Ecological Modernization Theory: Towards a Radical Ecopolitics of Change?” Environmental Politics Journal 19:4 (July 2010) 538-556; Editor, Unsettled Balance: Ethics, Security and Canada's International Relations (UBC Press, 2015); Editor, Ethics and Security in Canadian Foreign Policy (UBC Press, 2001).

Patrick James

Patrick James is the Dana and David Dornsife Professor of International Relations at the University of Southern California.

Sarah Gansen

Sarah Gansen is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California and a graduate of USC Gould School of Law.

Notes

1 A full background to, and explanation of, the contents of appears in the introduction to this special issue by Gansen and James.

References

- Ahrens, J., & Rudolph, P. M. (2006). The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 14(4), 207–220.

- Haque, C. E., & Etkin, D. (2012). Dealing with disaster risk and vulnerability: People, community and resilience perspectives. In C. E. Haque & D. Etkin (Eds.), Disaster risk and vulnerability: Mitigation through mobilizing communities and partnerships (pp. 3–23). Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

- Helsloot, I., Boin, A., Jacobs, B., & Comfort, L. K. (Eds.). (2012). Mega-crises: Understanding the prospects, nature, characteristics and the effects of cataclysmic events. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- James, P. (2019). Systemist international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 63(4), 781–804. doi:10.1093/ISQ/SQZ086

- Krämer, S., & Ljungberg, C. (2016). Thinking and diagrams – An introduction. In S. Krämer & C. Ljungberg (Eds.), Thinking with diagrams : The semiotic basis of human cognition (pp. 1–20). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Public Safety Canada. (2018). Canada’s platform for disaster risk reduction. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/mrgnc-mngmnt/dsstr-prvntn-mtgtn/pltfrm-dsstr-rsk-rdctn/index-en.aspx.

- Richard Eiser, J., Bostrom, A., Burton, I., Johnston, D. M., McClure, J., Paton, D., … White, M. P. (2012). Risk interpretation and action: A conceptual framework for responses to natural hazards. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 1(1), 5–16. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2012.05.002.

- Warner, R. (2013). Resilience or relief: Canada’s response to global disasters. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 19(2), 223–235. doi:10.1080/11926422.2013.773541

- Warner, R. (2019). Governance for resilience: Canada and global disaster risk reduction. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 26(3), 1–15.

- Wickham, H. (2014). How is data science different to mainstream statistics? Communication and visualization are key features of analysis. Impact of Social Sciences. LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2014/09/23/data-science-statistics-communication/.