ABSTRACT

Brexit has forced Canada to reconfigure relations with its European partners: the European Union (EU), on the one side, and the United Kingdom (UK), now on the other. This article examines whether this reconfiguration has led to debates in the Canadian news media that reassess the purpose and priorities of Canada’s transatlantic relationships. Did Canada-Europe relations after Brexit become a more prominent issue in Canadian newspaper commentary? Which policy aspects were highlighted? How did evaluations of Canada’s European partners change? Which new controversies and divisions emerged within Canadian discourse about transatlantic relations? The study is based on an analysis of almost 1,900 commentary articles from six Canadian newspapers between June 2014 and June 2021.

RÉSUMÉ

Le Brexit a forcé le Canada à reconfigurer ses relations avec ses partenaires européens : l'Union européenne (UE), d'un côté, et le Royaume-Uni (RU), désormais de l'autre. Cet article examine si cette reconfiguration a conduit à des débats dans les médias d'information canadiens qui réévaluent l'objectif et les priorités des relations transatlantiques du Canada. Les relations Canada-Europe après le Brexit sont-elles devenues un sujet plus prééminent dans les commentaires des journaux canadiens ? Quels aspects politiques ont été mis en évidence ? Comment les évaluations du Canada par les partenaires européens ont-elles évolué ? Quelles nouvelles controverses et divisions sont apparues dans le discours canadien sur les relations transatlantiques ? L'étude est basée sur l'analyse de près de 1,900 commentaires dans six journaux canadiens entre juin 2014 et juin 2021.

Introduction

On January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom (UK) withdrew from the European Union (EU). The UK’s “Brexit” was the culmination of a lengthy process set in motion by the referendum of June 23, 2016, in which a narrow but decisive majority of British voters opted for their country to leave the EU. Brexit resulted in the establishment of new, uncertain and, at times, tense economic and political relations across the English Channel. It also affected the EU’s and the UK’s international partners, including Canada (Adler-Nissen et al., Citation2017; Chaban et al., Citation2020). Whenever a divorce occurs, friends are forced to ask themselves if they can maintain close relationships with both divorcing parties, or if they must choose one over the other. The answer to that question depends on the type of relationship that the divorcing parties manage to develop with each other: cordial or acrimonious. It also depends on whether one blames one party or the other for the divorce. In Canada’s case, Brexit and its aftermath generated questions and analysis regarding future relations with both the EU and the UK, two of Canada’s most important international political and economic allies (Hurrelmann, Citation2020; Hurrelmann et al., Citation2021).

This article examines how such questions about the future of Canada’s transatlantic relations were raised in political commentaries in Canadian newspapers. International news coverage in Canada is usually limited to, and dominated by, reporting on the United States (US) (Burton et al., Citation1995; Goodrum & Godo, Citation2011; Soderlund et al., Citation2002). However, the Brexit referendum was an exception; it generated intense media interest, owing both to its unexpected outcome and to the political and economic tensions that it caused in the UK and in the EU (Waddell, Citation2018, p. 310). Along with the strategic challenges of reconfiguring the Canada-Europe relationship after the EU-UK divorce, this media attention implies a potential for broader public debates about the future of Canadian foreign policy, especially with respect to the purpose and priorities of Canada’s transatlantic relationships.

Our conceptual framework for the analysis of media debates builds on these considerations. We start from the literature on guiding ideas about Canada’s role in world politics, especially the concepts of Europeanism, internationalism, and continentalism (Mérand & Vandemoortele, Citation2011). In the first section, we show that transatlantic relations prior to Brexit could be embraced as a priority by all three of these conceptions. However, Brexit and the controversies it triggered have the potential to upset this consensus, to make Canada’s transatlantic relations an increasingly contentious political topic, and thus to contribute to the development of new conceptions of Canada’s international role. Our analysis probes if such changes have indeed occurred. In the second section, we detail our methodological approach. We provide a rationale for our selection of material – opinion articles from six Canadian newspapers (The Globe and Mail, The National Post, The Toronto Star, Le Devoir, La Presse/La Presse+, and Le Journal de Montréal) over a seven-year period (June 2014 to June 2021) – and explain our key analytical categories. We then proceed to the presentation of our empirical results. The third section examines if Brexit led to an increase in media debates that raised questions about Canada’s transatlantic relations. The fourth section reviews if Brexit resulted in a higher number of explicit – positive or negative – evaluations of the EU and the UK, Canada’s most important transatlantic partners. The fifth section takes stock of political conflicts and divisions that emerged within Canadian media discourse on Brexit, for instance when comparing English- and French-language newspapers or left- and right-leaning publications. Our analysis allows for a first assessment of whether Brexit has set in motion lasting changes in perceptions of Canada’s international priorities and partnerships.

Conceptual framework

As Mérand and Vandemoortele (Citation2011) have spelled out, Canada’s foreign policy since the end of the Second World War has been shaped by the constructive tension between three conceptions of Canada’s international role: Europeanism, internationalism, and continentalism (Mérand & Vandemoortele, Citation2011). Europeanism emerges from Canada’s relationship to its former colonial powers, Great Britain and France, which has resulted in lasting cultural and political linkages to Europe. This conception has found expression in descriptions of Canada as being a part of the Anglosphere (Vucetic, Citation2011) and/or the Francosphere (Massie, Citation2013), but also in the relationship with the EU and its predecessor institutions. Internationalism, which emerged in the 1950s, reflects Canada’s aspiration to shape global institutions as an internationally minded “middle power”; it emphasizes multilateralism, international law, and a commitment to peaceful conflict resolution (Roussel & Robichaud, Citation2004; Keating, Citation2012). Continentalism, finally, takes Canada’s economic and geopolitical dependency on the US as its starting point. This view calls for foreign policies that are in sync with Canada’s powerful neighbour (Hart, Citation2008). While the balance between the three conceptions has often been the subject of controversy, they are not in principle incompatible, and Canadian policy makers have usually pursued some combination of them.

Canada’s transatlantic relations must be interpreted in this context. Outside of the security realm, which has been dominated by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the relationship to the EU was the most important institutional cornerstone of this relationship prior to Brexit (Potter, Citation1999; Dolata-Kreutzkamp, Citation2010; Chaban, Citation2018; Rayroux, Citation2019; Hurrelmann, Citation2020). While the UK was an EU member state, the Canada–EU relationship could be embraced by all conceptions of Canada’s international role. For Europeanism, it represented an updated framework for relations with traditional allies, while not forcing a choice between Anglosphere and Francosphere loyalties. For internationalism, European integration was an embodiment of what could be achieved through multilateral cooperation, leading the EU to become a strong supporter of (effective) multilateralism beyond its borders (Kissack, Citation2010; Bouchard et al., Citation2014; Drieskens & van Schaik, Citation2014). And most versions of continentalism did not object to complementing Canada–US continental relations with connections to the EU, which after all was a reliable US ally. Nevertheless, the Canada–EU relationship always had limitations. It never meaningfully reduced Canada’s dependency on the US. It also retained a heavy focus on economic relations, while political or security aspects of the partnership remained shallow (Haglund & Mérand, Citation2011, p. 38; Rayroux, Citation2019; Verdun, Citation2021).

These considerations underline why Brexit has the potential to lead to new debates and divisions in Canadian foreign policy (Hurrelmann, Citation2020; Hurrelmann et al., Citation2021). Brexit means that Canada now needs to cooperate with two transatlantic partners – the EU and the UK – which are themselves struggling to define their new relationship. It raises questions not only about the country’s primary attachments and loyalties in the transatlantic relationship, but also about whether Europeanism, internationalism, and continentalism can still be reconciled as guidelines for Canadian foreign policy in the North Atlantic region. It also relates to other issues of contention in contemporary politics, especially on questions of democracy, as it can be seen either as example of a global populist assault on evidence-based politics (like Donald Trump’s election in the US in 2016) or as an affirmation of national self-determination and sovereignty over technocracy and unaccountable international institutions. Such perceptions have coloured the initial responses of some Canadian politicians, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who harshly criticized Brexit, and former opposition leader Andrew Scheer, who was an enthusiastic proponent (Bell & Vucetic, Citation2019; Hurrelmann, Citation2020).

It matters greatly, however, whether such questions are debated primarily in diplomatic and policy circles, or in broader political discourse. Foreign policy professionals are skilled in managing relations with different international partners, including ones who might not see eye to eye. But if broader societal debates develop about future priorities of Canada’s transatlantic relations, involving, for instance, opinion leaders from civil society or prominent media pundits, this may create controversies within Canada that Canadian diplomacy may struggle to bridge (Coppock et al., Citation2018). Our objective in this study is to examine political commentary in Canadian news media to obtain an understanding of the ideas and arguments that have had the potential to influence Canada’s foreign policy decision makers.Footnote1 Our analysis is guided by three research questions.

Did Brexit lead to an increase in media debates that raised questions about Canada’s transatlantic relations? Previous studies of Canadian media reporting about the EU – at the time still including the UK as a member state – have described a limited, relatively superficial, and largely economically framed coverage. Croci and Tossutti (Citation2007; Citation2009) examine EU-related reporting in the Globe and Mail, National Post, and Toronto Star between 2000 and 2007. They find that “Canadian dailies devote little attention to the EU” (Croci & Tossutti, Citation2007, p. 303). When the EU is covered, it is presented primarily as an important market for Canadian firms, especially to reduce Canada’s economic dependence on the US. Rayroux (Citation2019), in his analysis of reporting in Canada’s two national English-language dailies as well as La Presse (Canada’s largest French-language daily) over a three-month period in 2015, also finds that news coverage about the EU was dominated by economic issues. Analyzing Canadian media coverage of the Brexit referendum in June 2016, Waddell (Citation2018, p. 315) finds that the “issue was covered as primarily a debate about economics”, especially before the vote. If Brexit has indeed triggered a reconsideration of Canada’s strategic priorities and alliances in Europe, we would expect these patterns to change. Canadian media debates about Europe should be characterized by a quantitative and qualitative expansion: a higher number of articles that talk about Europe and transatlantic relations as well as a broadening of the scope beyond economics.

Did Brexit lead to more explicit – positive or negative – evaluations of the EU and the UK? Based on the influential typology by Hallin and Mancini (Citation2004), Canada is usually described as a liberal media system. Such systems are characterized, inter alia, by highly professionalized media organizations, a clear separation of news reporting and editorial pages, and – within the latter – internal political diversity in the positions taken, notwithstanding relatively consistent political orientations of different media sources. Previous research about media representation about the EU in Canada has shown that this media system has resulted in relatively little explicitly evaluative coverage of the EU. When evaluations occurred, they followed predictable patterns. For instance, Croci and Tossutti (Citation2007:, p. 304) find that “the articles in the National Post tend to portray the EU as too interventionist and the economic problems that result from it, whereas those in the Globe and Mail tend to underline the benefits” of European integration. Gänzle and Retzlaff (Citation2008:, p. 644), in a study of newspaper discourses on the occasion of the Treaty of Rome’s 50th anniversary in 2007, show how the National Post and the Globe “used different linguistic strategies to construct particular representations of the EU according to their own ideological affiliations”. Waddell (Citation2018:, pp. 313–315), in his analysis of Canadian news media’s coverage of the Brexit referendum, notes that the Globe, especially in its editorials, advocated for the Remain side, while the Post avoided taking sides. If Brexit indeed has given rise to broader societal debates about Canada’s transatlantic relationships, we would expect an increase in such evaluative content: more opinion articles that present positive or negative assessments of the EU and/or the UK, possibly including explicit judgements on their suitability as strategic partners for Canada in the post-Brexit era.

Did significant internal conflicts and divisions emerge within Canadian media discourse in how Brexit was discussed? An increase in positive or negative evaluations of the EU and/or the UK would be particularly consequential politically if it were structured by clear political cleavages. Ideological left-right differences have already been mentioned as one potential fault line. Another element to consider when analyzing Canadian news coverage is whether there exist significant differences between English-language and French-language media organizations. Using an expert survey conducted in 2018, Thibault et al. (Citation2020) analyze the “parallelism” between politics and the media in Canada to determine if (French-speaking) Quebec represents a “sub-system” in the liberal Canadian media system. The authors do not find that this is the case: “There is scant evidence of regional variations across provinces with respect to the level of professionalization and politicization within the Canadian media system” (Thibault et al., Citation2020, p. 652). However, they do find that there is a “variety of ideological and political preferences displayed by Canadian news media organizations” (ibid), thereby confirming the findings of the above-mentioned studies regarding news coverage of the EU. If Brexit has led to increased contestation of Canada’s transatlantic relations, we would expect to see an intensification of such patterns. We should observe differences in evaluations between media sources that reflect Canada’s linguistic divide and/or the newspapers’ partisan leanings. For instance, the National Post would be expected to be more favourable to Brexit while focusing on Canada-UK relations as a strategic priority, while the Globe and Mail should offer a more critical stance on Brexit as well as highlighting the EU’s importance as an economic partner for Canada.

If Brexit provoked more media discussions of Canada’s transatlantic relations, and those discussions were not only more evaluative but also more divided between support for Brexit and the UK and support for the EU and against Brexit, then those discussions, if sustained, would lead to a reconfiguration of perceptions of Canada’s international role. For instance, they could bifurcate – and hence weaken – the Europeanist conception of Canada’s foreign policy, especially if the tensions between the EU and the UK caused by Brexit remain unresolved. This could result in a strengthening of the internationalist and continentalist conceptions of Canada’s role in the world, especially as Canada faces increased pressures to be more involved in the Indo-Pacific region (Holland, Citation2021; MacDonald & Vance, Citation2021).

Methodological considerations

To assess whether Brexit has triggered these developments in Canadian media discourse, we performed a content analysis of commentary articles about Canada’s transatlantic relations in six newspapers: The Globe and Mail, The National Post, The Toronto Star, Le Devoir, La Presse/La Presse+, and Le Journal de Montréal.Footnote2 We focused on broadsheet newspapers – as opposed to tabloids, television, or social media – because these tend to provide the most differentiated and reflective assessment of political developments; they are also often assumed to have a particularly strong opinion-leading influence on foreign policy practitioners. As Chaban et al. (Citation2018, p. 200) note, they are “a mechanism that spreads ideas on foreign policy and actors, typically originating from the national administration and elites – the typical readers of national prestigious press – ‘down the cascade’ to the general public [and] ‘pumps up’ feedback from the public back to the decision-makers”. In addition to their reach and potential influence, the six newspapers were also selected to reflect the linguistic and ideological diversity of Canada’s media system (Young & Dugas, Citation2012; Thibault et al., Citation2020).

The period under analysis encompasses the two years prior to the Brexit referendum (June 24, 2014 to June 23, 2016) and the five years that followed (June 24, 2016 to June 23, 2021). Hence, it covers the political debates in the lead-up to the referendum, its immediate aftermath, as well as the various milestones of the Brexit process (including the Withdrawal Agreement, transition period and eventual UK exit from the EU). Our study is ambitious with respect to both the diversity of newspapers included and the period covered – most previous work on media debates about Canada–EU relations examines only English-language media (for an exception, see Rayroux, Citation2019) and tends to look at periods of only a few months or less (for an exception, see Croci & Tossutti, Citation2007; Citation2009).

In light of the fact that most news reporting about Europe in Canadian media stems from international news agencies – such as Reuters or Agence France-Presse – and thus does not present a specific Canadian perspective (Chaban et al., Citation2018, p. 199, 217-18; Rayroux, Citation2019, p. 71), we decided to focus only on opinion articles (editorials, op-eds, and commentaries), which tend to be produced or at least procured in Canada.Footnote3 As mentioned above, these articles are also the ones most likely to influence policy makers or reflect the ideas that might influence their decisions. Relevant articles were selected from the media databases Factiva (for English-language sources) and Eureka (for French-language sources) in a two-step process: First, an automatic keyword search was conducted to identify articles in which (a) Canada, (b) the EU or the UK, and (c) their economic/political relations or policies are mentioned in the same paragraph.Footnote4 Second, the search results were manually screened by three extensively trained coders – co-authors of this article – to identify opinion articles. An inter-coder reliability test confirmed that this determination could be made with a high degree of reliability (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.783).

This selection process generated a total of 1,874 articles. All of them mention Canada with some reference to the EU and/or the UK. However, transatlantic relations with the EU or UK are not necessarily their primary focus; articles may also discuss broader foreign policy issues not restricted to transatlantic affairs or even issues of domestic politics, as long as both Canada and the EU/UK are mentioned. The articles were read carefully by our three coders and manually coded based on pre-defined categories. In addition to formal characteristics (time of publication, language, etc.), the following content categories were identified as relevant for the analysis in this article:

Regional focus: Are transatlantic relations the primary focus of the article, or are the EU and/or UK mentioned in an article that primarily deals with a different geographical area? Our coding options in this respect are (a) focus on transatlantic relations with the EU and/or the UK, (b) Canadian foreign policy/international relations more broadly, (c) Canadian domestic politics, and (d) EU/UK domestic politics.

Substantive focus: Which policy fields are addressed in the article? In this respect, we distinguish between (a) economics/trade, (b) security/defence, (c) energy/environment, and (d) other policy issues.

Evaluation of the EU, the UK, and Brexit: Are the EU, the UK, and/or Brexit explicitly mentioned in the article? If they are, we code for each of them if they are evaluated (a) positively, (b) negatively, or (c) in a neutral/differentiated manner.Footnote5

Coders were trained in the application of these categories, drawing on a detailed codebook.Footnote6 An inter-coder reliability test was performed, which resulted in satisfactory results (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.847 for regional focus, 0.739 for substantive focus, 0.699 for evaluation of the EU, 0.934 for evaluation of the UK, and 0.794 for evaluation of Brexit).

Our selection and coding of newspaper articles generated a dataset that provides us with differentiated material to answer our three research questions. We can sketch the importance of transatlantic relations with the EU and/or the UK in Canadian media debates (first research question) by mapping the number of articles that meet our search criteria in each given year. We can also examine how many of these explicitly mention Brexit. In addition, we can get a more nuanced sense of how transatlantic relations are discussed by analyzing whether transatlantic relations are the articles’ main focus and which substantive policy issues dominate. The evaluation of Canada’s transatlantic partners, as well as of Brexit itself (second research question), can be studied based on our evaluative coding categories, focusing in each case on the subset of articles that contain positive, negative, or neutral/differentiated evaluations. The diversity of newspapers included in our analysis makes it possible, finally, to assess differences between media sources (third research question), for instance between English- and French-language publications or between newspapers that are commonly perceived as left-wing (Toronto Star, Le Devoir), centrist (Globe and Mail, La Presse), or right-wing (National Post, Le Journal de Montréal) (for empirical data on perceptions of newspapers’ political leanings, drawing on an expert survey, see Thibault et al., Citation2020).

Results I: thematic focus of newspaper debates

The first step of our inquiry assessed how the Brexit process has impacted Canadian media debates on transatlantic relations over time. Did Brexit lead to an increase in media debates that focus on Canada’s relations with European partners? Did these debates shift from a focus on economics/trade to a broader discussion of political and strategic partnerships? Our findings on the regional and substantive focus of media debates allow us to investigate these questions.

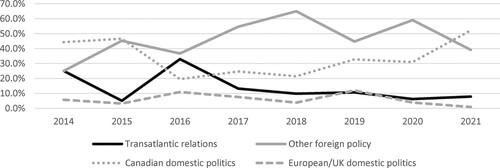

As previously mentioned, our text corpus is composed of opinion articles that discuss Canada with reference to the EU and/or the UK. Our selection strategy did not require that articles be about transatlantic relations in a narrow sense; they may also discuss broader foreign policy issues or Canadian/European/UK domestic politics. It also did not require that articles explicitly mention Brexit. This selection strategy allows us to map the rise and fall of Brexit as a topic in opinion articles that discuss Canada with reference to its European partners. As shows, the UK’s withdrawal from the EU was barely discussed prior to 2016, but it made up almost 40 percent of articles in 2016, the year of the referendum. It declined in 2017 and 2018 to rise in 2019 when the Withdrawal Agreement faced a difficult passage through the British parliament; subsequently, it largely disappeared from Canadian commentary pages. These findings suggest that Canadian debates were primarily driven by day-to-day events in the Brexit process, rather than longer-term reflections about Canada’s foreign policy priorities.

Table 1. Share of selected opinion articles that mention Brexit.

Our findings on the articles’ regional focus also shed doubt on the extent to which Brexit triggered longer-term changes in how Canadian newspapers discussed relations with Canada’s European partners. As shows, Brexit did not lead to a lasting increase in the share of articles that focus on transatlantic relations in a narrow sense. Although there was substantial interest in transatlantic relations in 2016, triggered by Brexit but also by the conclusion of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the EU, this interest faded relatively quickly. From 2017 onwards, other issues gained in importance. These included broader foreign policy issues, such as the election of Donald Trump in the US or relations with China. They also included aspects of Canadian domestic politics that were discussed with a European reference point, such as the “Wexit” debate following the federal election of 2019 and the response to COVID-19 in 2020/21. In the context of COVID-19, comparisons to the EU and/or the UK were frequently made in terms of pandemic management or access to vaccines.

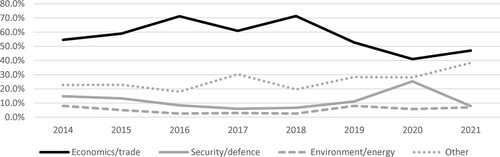

The substantive focus of opinion articles in our text corpus confirms that Europe – understood as encompassing both the EU and the UK – continues to be important for Canada primarily for economic reasons (). Articles with an economics/trade focus represent 60 percent of all selected articles, which is in line with previous studies of Canadian news coverage of the EU. The predominance of articles focusing on economics/trade did not decline in the immediate aftermath of Brexit. This is in part an effect of CETA, which was discussed both as a cornerstone of Canada–EU relations and as a possible blueprint for EU-UK relations post-Brexit (described in the UK as the so-called “Canada model”). Future Canada-UK economic relations after the British withdrawal were another matter for discussion, including the possibility of a Canada-Australia-New Zealand-UK (CANZUK) trade deal.

Non-economic issues did become more important in the analyzed articles after 2018, even though economics/trade remained the dominant category. It is important to note, however, that the non-economic issues that gained ground – especially debates about China after the imprisonment of the “two Michaels” and debates about health issues (coded as “other”) in light of COVID-19 – were mainly not linked to transatlantic relations in a narrow sense. The lasting dominance of an economic framing of Canada’s transatlantic relationship becomes evident if we examine linkages between the articles’ regional and substantive focus (). This analysis shows that, while about one in five articles about economic issues have a regional focus on transatlantic relations, this is the case for fewer than one in fifteen articles focusing on security and defence. The share of articles with a transatlantic focus is similarly low for “other” policy issues, and only slightly higher for energy/environment. In other words, as soon as non-economic topics move to the centre of media commentary, Canada’s relations with its European partners become a secondary issue at best.

Table 2. Linkages between substantive and regional focus (column percentages).

Based on the analysis conducted here, we can conclude that the Brexit process did not lead to an increase in newspaper commentaries surrounding transatlantic relations between Canada and the EU and/or the UK. Brexit was clearly an important topic of media commentary following the referendum vote in June 2016, but the focus on the issue was not sustained, and Brexit-related discussions do not seem to have triggered lasting changes in the thematic focus of Canadian media debates about transatlantic relations.

Results II: evaluations of the EU, the UK and Brexit

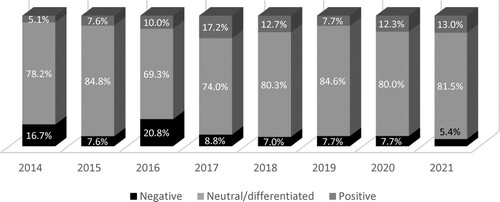

Even in the absence of a growing importance of transatlantic relations in Canadian media discourse, changes induced by Brexit could still have occurred in the form of shifts in how Canada’s transatlantic partners are being evaluated. Of the three objects whose evaluation we tracked in our analysis (EU, UK, Brexit), the EU was mentioned most frequently in our articles (). Most articles mentioning the EU did not contain a clear positive or negative evaluation; these were classified as “neutral/differentiated”. A look at those articles that did develop explicit positive or negative assessments of the EU reveals trends that reflect current political matters under discussion. In 2016, in the wake of the Brexit referendum and the difficult negotiations surrounding CETA, negative evaluations were at their highest point across the period under analysis, at 20.8 percent. These negative articles would often harken to fears over the stability and effectiveness of the European project in light of the UK’s exit. Articles also lamented the EU’s difficulties in agreeing on CETA, especially because of Belgium’s initial failure to sign the agreement as a result of Wallonian opposition.

As the EU developed a strong negotiating position on Brexit and managed to get CETA approved by the Council and European Parliament, while the UK’s difficulties in implementing Brexit became more obvious, EU-related evaluations improved significantly: positive evaluations rose by more than seven percentage points between 2016 and 2017, while negative evaluations dropped by twelve percentage points. The years that followed saw some fluctuations, but no lasting change to this overall pattern. As Donald Trump’s presidency brought challenges to free trade to the fore of the Canadian media landscape,Footnote7 relations with the EU were more frequently framed in a positive light. CETA’s ratification was highlighted as a success in discussions surrounding the NAFTA renegotiations, and the EU came to be portrayed as a bastion of cosmopolitanism in the face of American protectionism and isolation. Negative evaluations of the EU remained stable at around seven percent between 2018 and 2020, before falling to their lowest point (5.4 percent) in 2021.

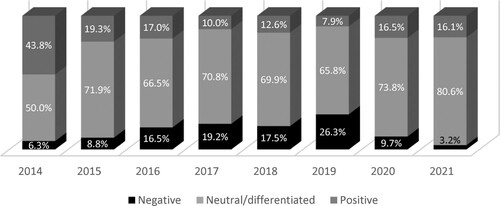

The UK was mentioned in 785 articles in our text corpus. Evaluations of the UK were subject to considerable fluctuation, which can be linked to the political climate in the UK in relation to Brexit (). The Brexit referendum resulted in an increase in negative evaluations and a drop in positive evaluations after 2016.Footnote8 As the political fallout of Brexit unfolded,Footnote9 negative evaluations of the UK increased and eclipsed positive evaluations. In 2019, negative evaluations reached their highest level, with 26.3 percent of all articles mentioning the UK containing a negative evaluation, a clear reflection of the tumultuous politics in the UK at the time. Even in articles featuring sympathetic evaluations of the UK in 2019, which amounted to only 7.9 percent of the UK evaluations made, words such as “chaos”, “bog”, “impasse” and “a mess” were frequently used to describe the UK’s state of affairs. However, after the EU and the UK approved a revised version of the Withdrawal Agreement in January 2020 and the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) in December 2020, negative assessments of the UK declined sharply (dropping to 9.7 percent in 2020 and 3.2 percent in 2021), with a corresponding increase in positive and neutral evaluations. In other words, Brexit does not seem to have done lasting damage to how the UK is perceived in Canadian media commentaries.

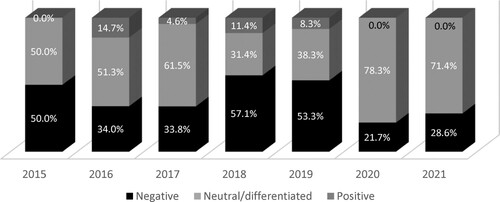

Lastly, we examined evaluations of Brexit itself. In the 352 articles that mentioned Brexit, explicit positive or negative evaluations occurred quite frequently, especially compared to evaluations of the EU and the UK, which were neutral or differentiated in most articles. The character of evaluations of Brexit varied significantly from one year to another (). In 2016, the year of the referendum, 14.7 percent of the commentaries expressing an assessment of Brexit viewed it in positive terms. The share of positive evaluations declined in the following years; in 2020 and 2021, not a single article in our sample evaluated Brexit positively.

The percentage of negative evaluations of Brexit was much higher. While the reaction to Brexit in the early years was predominantly differentiated, by 2018 it had become largely negative, with negative evaluations (57.1 percent) totalling almost twice the number of neutral/differentiated evaluations (31.4 percent). The situation was similar in 2019. These negative assessments of Brexit were no doubt a reflection of the tumultuous political climate in the UK catalyzed by Brexit during this period. Across the newspapers covered, 2020 saw a dramatic drop in Brexit coverage as the political praxis surrounding Brexit in the UK gradually began to subside. This coincided with in a significant decline in negative evaluations of Brexit and a general return to predominantly neutral/differentiated evaluations.

In sum, although Brexit was not viewed very positively in the Canadian newspaper commentaries that we analyzed, it did not lead to lasting changes in commentators’ assessment of Canada’s European partners. While we can observe changes in dominant evaluations in the years that marked the height of the Brexit discussions – 2016–2019 – these changes proved temporary and the years that followed saw a return to a picture close to the status quo ante. These results are coherent with findings in earlier studies on Canadian media reporting about Europe, namely that political or economic tensions or crises influence not only the extent of news coverage but also the assessment of the parties involved. In terms of Canada’s relations with its European partners, our analysis finds that there has not been a major shift in aggregate perceptions towards the EU and the UK because of Brexit.

Results III: differences between newspapers

Even if Brexit has not had a lasting effect on overall assessments of the EU and the UK in Canadian newspaper commentaries, it is still relevant to examine differences across newspapers. As noted above, previous research points to partisan differences between news outlets. It is also plausible to expect differences between English- and French-language newspapers, though this aspect has not been studied systematically in previous work on the Canada–EU relationship. In this section, we turn to such differences across media outlets.

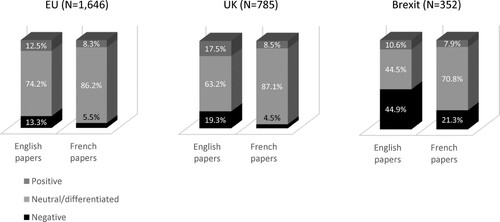

It makes sense to begin by comparing English- and French-language discourses. In this respect, it is striking that opinion articles in the English-language newspapers show a much greater willingness to engage in evaluative (positive or negative) discourse about the EU, the UK, and Brexit than articles in French-language newspapers (). This difference is particularly pronounced for negative evaluations. While 13.3 percent of all selected articles in our English-language newspapers evaluate the EU negatively, the corresponding figure for French-language articles is only 5.5 percent. For evaluations of the UK, 19.3 percent of evaluations in the English-language newspapers are negative, but only 4.5 percent of evaluations in the French-language newspapers. Similarly, while 44.9 percent of English-language articles evaluate Brexit negatively, only 21.3% of French-language articles come to this conclusion.Footnote10

These results may point to differences in the resonance of Brexit for English- and French-language newspaper audiences. While Brexit has a direct effect on how many English-Canadian commentators perceive their country’s British heritage and connections to the UK as a former colonial power, Francophone Canadians’ historical and cultural connections across the Atlantic are affected by the UK’s withdrawal from the EU in a much less immediate way. In fact, the three French-language newspapers studied displayed a particular focus on Quebec internal affairs, covering mostly local and provincial news. The EU, the UK, and Brexit were rather anecdotally mentioned in reference to Quebec’s inward provincial politics. Furthermore, transatlantic relations are often displayed in the bilateral relationship between Quebec’s provincial government and individual EU member states, as opposed to interactions with the EU as whole, which are mainly conducted by the federal government. In this regard, particular attention is given to France, which, as described in previous research (Fletcher, Citation1998), is presented as an important partner and ally for Quebec.

The greater willingness of English-language newspaper commentators to explicitly evaluate Canada’s transatlantic partners as well as Brexit results in more pronounced differences between the various publications (). These reflect the newspapers’ ideological leanings on economic and social issues, with the Toronto Star located left-of-centre, the Globe and Mail located at the centre, and the National Post located right-of-centre. Differences are particularly noteworthy between the Globe and Mail and the other English-language newspapers with respect to the percentage of positive evaluations of the EU: while 22.7 percent of articles in the Globe that mentioned the EU contained a positive evaluation, this was the case for only 8.8 percent in the Star and 5.2 percent in the Post. Conversely, positive evaluations of the UK and of Brexit are much less frequent in the Globe (12.6 and 4.0 percent of articles, respectively) and the Star (13.2 and 4.0 percent) than in the Post (24.2 and 23.6 percent). Comparable partisan differences can be observed in the French-language newspapers only with respect to commentators’ assessment of Brexit. While Le Journal de Montréal and Le Devoir published some articles expressing a positive evaluation of Brexit (19 and 12.5 percent, respectively), La Presse did not. On the other hand, of the three French-language newspapers, La Presse published the highest percentage of articles with negative evaluations of Brexit (27.3 percent).

Table 3. Evaluation of the EU, UK and Brexit by newspaper (column percentages).

These findings on partisan or ideological differences in evaluations of Canada’s transatlantic partners as well as Brexit correspond to differences found in public statements of Canadian federal party leaders on Brexit (Hurrelmann, Citation2020), as well as Canadian public opinion about the issue (Hurrelmann et al., Citation2021). They underline that Brexit and its implications for Canada are potentially divisive in Canadian political debates about transatlantic relations. However, the fact that transatlantic relations as a topic of media commentary did not achieve much prominence in the period under investigation means that these divisions did not register very strongly in newspaper discourse.

Conclusion

The UK’s withdrawal from the EU was a major shock not only for European politics, but also for the EU’s and the UK’s relations with non-European partners such as Canada. In Canadian media reporting on international affairs, Brexit led to a temporary focus on Europe, as an increased number of newspaper commentaries raised questions about its impact on Canada’s transatlantic relations. However, this development proved short-lived. Discussions about Canada’s transatlantic relations with the EU and the UK were soon displaced on newspapers’ commentary pages by broader debates about international affairs – often in the context of US or Chinese international policies, and later COVID-19 – in which Europe was not of primary concern. This means that no sustained media debate about a reconfiguration of Canada’s political relationships with its European partners developed. Evaluations of the EU and the UK were temporarily affected by the Brexit process, but did not change in a lasting way. What became evident, even in the relatively limited media debate, were differences between the various newspapers in their evaluation of the EU and the UK. These differences correspond to the newspapers’ partisan leanings. This finding supports the notion that there is an undercurrent of partisan conflict about transatlantic relations in Canadian public discourse, which could in principle provide a fertile ground for broader controversies about a reconfiguration of Canada’s international priorities in a post-Brexit world. However, in the period under examination, the transatlantic relationship was simply not salient enough for this conflict to achieve major significance in public discourse. Therefore, Canadian policy makers have faced only little public pressures in dealing with the fallout of Brexit. In terms of Canadian foreign policy’s three conceptions (Europeanism, internationalism, and continentalism), this means that we can expect no change because of Brexit. This could change, however, if post-Brexit relations between the EU and the UK – for instance over the contentious issue of the Irish border – were to become sharply more conflictual.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was supported by an Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (435-2019-0770). We thank Amy Verdun for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Achim Hurrelmann

Achim Hurrelmann is Professor of Political Science and Co-Director of the Centre for European Studies at Carleton University. His research focuses on the politics of the European Union, with a particular emphasis on political discourses about European integration, the democratization of the EU, as well as Canada-EU relations.

Sarra Ben Khelil

Sarra Ben Khelil is a Master’s degree graduate from the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. Her research focuses on the European Union’s international trade policy, Canada-EU trade relations, as well as intellectual property in relations to international trade. She is also a policy analyst at the federal government, working on international relations files.

Asif Hameed

Asif Hameed is a PhD candidate and instructor with Carleton University’s Department of Political Science. His research focuses on the impact of social media on political discourse, as with as broader issues of race and politics, dis/misinformation, civic engagement, and right-wing politics in the Canadian context.

Akaysha Humniski

Akaysha Humniski holds a PhD from the Department of Political Science at Carleton University. Their research focuses on the discursive politics of the European Union, gender equality policymaking, and political mythmaking in times of crisis.

Patrick Leblond

Patrick Leblond is Associate Professor and holds the CN-Paul M. Tellier Chair on Business and Public Policy in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. He is also Senior Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), Research Associate at CIRANO and Affiliated Professor of International Business at HEC Montréal. Dr. Leblond is an expert on economic governance and policy.

Notes

1 Analyzing the impact of these ideas and arguments on Canadian foreign policy is beyond the scope of this study.

2 Our sample includes the five newspapers with the largest average daily circulation in Canada: The Globe and Mail, 323,133; The Toronto Star, 308,881; La Presse, 279,731; Le Journal de Montréal, 231,069; The National Post, 186,343 (News Media Canada, Citation2015). Le Devoir, despite having a smaller circulation (39,686), is also included because of its historical reputation as Canada’s francophone newspaper of record.

3 A focus on opinion articles is a widely employed strategy in media-content analysis. For a general discussion of its benefits, see Hoffman and Slater (Citation2007). Since our ambition is to map the discourse of “opinion leaders”, our analysis excluded letters to the editor.

4 Factiva search terms: >Canada same ((EU or Europe* or United Kingdom or UK or Britain) and (relations* or cooperation or collaboration or partnership or trade or trading or agreement or deal or policy))<. Eureka search terms: >Canada @ ((UE | Europe* | Royaume-Uni | RU | Grande-Bretagne) & (relations | coopération | partenariat | collaboration | échange | commerce | accord | pacte | politique))<.

5 Positive or negative evaluations were coded when the articles used language that explicitly presents the EU, UK, or Brexit in a favourable or unfavourable light, for instance though the use of adjectives (successful/failing, democratic/technocratic, important/irrelevant as an international partner, etc.) or more elaborate arguments. The category neutral/differentiated was used for articles that mentioned the EU, UK, or Brexit without an explicit evaluation, as well as for articles that included both positive and negative statements without one side being clearly dominant. While these two cases (neutral and differentiated) are not the same, they can be aggregated for the purposes of this analysis, which is interested in the presence and positive/negative nature of evaluations rather than the precise ways in which evaluations are constructed and justified.

6 The codebook is available at https://carleton.ca/ces/wp-content/uploads/Codebook-Media-Analysis-March-2021.pdf.

7 In January 2017, immediately following Trump’s installation as president, the US withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which included Canada as a member. Shortly thereafter, President Trump announced that he would pull the US out of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) unless it was renegotiated in America’s favour. Negotiations for a new NAFTA began in August 2017. Finally, in June 2018, the US imposed “national security” (or section 232) tariffs of 25 and 10 percent on steel and aluminium, respectively, with Canada retaliating immediately with its own punitive tariffs.

8 The high share of positive evaluations of the UK in 2014 should be treated with some caution due to the low number of articles mentioning the UK in that year (N = 32).

9 Events during this fallout period included the Conservative Party’s failed attempt at winning an electoral majority in 2017; Theresa May’s failure to pass the first version of the Withdrawal Agreement in 2018/2019; and Boris Johnson’s succession of May as Prime Minister in 2019, alongside his own subsequent challenges in winning parliamentary support for the Withdrawal Agreement.

10 These differences do not seem to be a result of differences in editorial practices between English- and French-language newspapers. In both groups, the share of opinion pieces written by journalists or regular columnists, as opposed to guest authors – academics, politicians, or civil society representatives – is almost exactly the same (55.2% in the English papers vs. 55.9% in the French papers). The French-language papers lean more heavily on academics as guest authors, and less on civil society representatives; however, the evaluative practices of both types of authors are largely similar.

References

- Adler-Nissen, R., Galpin, C., & Rosamond, B. (2017). Performing Brexit: How a post-Brexit world is imagined outside the United Kingdom. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 573–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117711092

- Bell, D., & Vucetic, S. (2019). Brexit, CANZUK, and the legacy of empire. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 21(2), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148118819070

- Bouchard, C., Peterson, J., & Tocci, N. (2014). Multilateralism in the 21st century: Europe’s quest for effectiveness. Routledge.

- Burton, B. E., Sonderland, W. C., & Keenleyside, T. A. (1995). The press and Canadian foreign policy: A re-examination ten years on. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 3(2), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/11926422.1995.9673066

- Chaban, N. (2019). Perceptions, expectations, motivations: Evolution of Canadian views on the EU. Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies, 11(3), 45–62. https://doi.org/10.30722/anzjes.vol11.iss3.15107

- Chaban, N., Kelly, S., & Rayroux, A. (2018). Communicating the EU externally: Media framing of the EU’s irregular migration crisis (case studies of New Zealand and Canada). In R. Bengtsson, & M. Rosén Sundström (Eds.), The EU and the emerging global order: Essays in honour of Ole Elgström (pp. 197–221). Lund University.

- Chaban, N., Niemann, A., & Speyer, J. (2020). Changing perceptions of the EU in times of Brexit. Routledge.

- Coppock, A., Ekins, E., & Kirby, D. (2018). The long-lasting effects of newspaper op-eds on public opinion. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 13(1), 59–87. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00016112

- Croci, O., & Tossutti, L. (2007). That elusive object of desire: Canadian perceptions of the European Union. European Foreign Affairs Review, 12(3), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.54648/EERR2007027

- Croci, O., & Tossutti, L. (2009). Canada and the European Union: A story of unrequited attraction. In F. Laursen (Ed.), The European Union in the global political economy (pp. 149–176). Peter Lang.

- Dolata-Kreutzkamp, P. (2010). Drifting apart? Canada, the European Union, and the North Atlantic. Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien, 30(2), 28–44.

- Drieskens, E., & van Schaik, L. G. (2014). The EU and effective multilateralism: Internal and external reform practices. Routledge.

- Fletcher, F. J. (1998). Media and political identity: Canada and Quebec in the era of globalization. Canadian Journal of Communication, 23(3), 359–380. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.1998v23n3a1049

- Gänzle, S., & Retzlaff, S. (2008). ‘So, the European Union is 50 … ’: Images of the EU and the 2007 German presidency in Canadian news. International Journal, 63(3), 627–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070200806300313

- Goodrum, A., & Godo, E. (2011). Elections, wars, and protests? A longitudinal look at foreign news on Canadian television. Canadian Journal of Communication, 36(3), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2011v36n3a2405

- Haglund, D. G., & Mérand, F. (2011). Transatlantic relations in the new strategic landscape: Implications for Canada. International Journal, 66(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201106600103

- Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Hart, M. (2008). From pride to influence: Towards a New Canadian foreign policy. UBC Press.

- Hoffman, L. H., & Slater, M. D. (2007). Evaluating public discourse in newspaper opinion articles: Values-framing and integrative complexity in substance and health policy issues. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 84(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900708400105

- Holland, K. (2021). Canada and the indo-pacific strategy. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 27(2), 228–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/11926422.2021.1880949

- Hurrelmann, A. (2020). Canada’s two Europes: Brexit and the prospect of competing transatlantic relationships. In N. Chaban, A. Niemann, & J. Speyer (Eds.), Changing perceptions of the EU in times of brexit (pp. 116–131). Routledge.

- Hurrelmann, A., Mérand, F., & White, S. E. (2021). Eurosphere or anglosphere? Canadian public opinion on Brexit and the future of transatlantic relations. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 54(3), 571–592. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000470

- Keating, T. (2012). Canada and world order: The multilateralist tradition in Canadian foreign policy, 3rd edition. Oxford University Press.

- Kissack, R. (2010). Pursuing effective multilateralism: The European Union, international organisations and the politics of decision making. Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacDonald, A., & Vance, C. (2021). Developing a Canadian indo-pacific geopolitical orientation. International Journal, 76(4), 564–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207020221083243

- Massie, J. (2013). Francosphère: L’importance de la France dans la culture stratégique du Canada. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Mérand, F., & Vandemoortele, A. (2011). Europe’s place in Canadian strategic culture (1949–2009). International Journal, 66(2), 241–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070201106600210

- News Media Canada. (2015). “Daily newspaper circulation data”, https://nmc-mic.ca/about-newspapers/circulation/daily-newspapers/, accessed September 15, 2022.

- Potter, E. H. (1999). Transatlantic partners: Canadian approaches to the European Union. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Rayroux, A. (2019). The EU’s reputation in Canada: Still a shallow strategic partnership? In N. Chaban, & M. Holland (Eds.), Shaping the EU’s global strategy: Partners and perceptions (pp. 55–75). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roussel, S., & Robichaud, C. (2004). L’État postmoderne par excellence? Internationalisme et promotion de l’identité internationale du Canada. Études Internationales, 35(1), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.7202/008451ar

- Soderlund, W. C., Lee, M. F., & Gecelovsky, P. (2002). Trends in Canadian newspaper coverage of international news, 1988-2000: Editors’ assessments. Canadian Journal of Communication, 27(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2002v27n1a1273

- Thibault, S., Bastien, F., Gosselin, T., Brin, C., & Scott, C. (2020). Is there a distinct Quebec media subsystem in Canada? Evidence of ideological and political orientations among Canadian news media organizations. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 638–657. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000189

- Verdun, A. (2021). The EU-Canada strategic partnership: Challenges and opportunities. In L. C. Ferreira-Pereira, & M. Smith (Eds.), The European Union’s strategic partnerships: Global diplomacy in a contested world (pp. 121–148). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vucetic, S. (2011). The anglosphere: A genealogy of a racialized identity in international relations. Stanford University Press.

- Waddell, C. (2018). Whose news? How the Canadian media covered Britain’s EU referendum. In A. Ridge-Newman, F. Léon-Solís, & H. O’Donnell (Eds.), Reporting the road to Brexit: International media and the EU referendum (pp. 305–320). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Young, N., & Dugas, E. (2012). Comparing climate change coverage in Canadian English and French-language print media: Environmental values, media cultures, and the narration of global warming. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 37(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjs9733