ABSTRACT

The main objective of this research is to establish the analytical framework of enemy-based foreign policy in order to understand certain actions of Russia’s foreign policy towards Ukraine during the invasion of 2022. Through a literature review on the construction of the enemy, the analysis of academic and journalistic sources, as well as the analysis of Vladimir Putin’s speeches and other official positions from the Kremlin, we determine that Russia’s foreign policy is oriented towards the reconfiguration of its identity in the international system through the disintegration of Ukraine, and at the same time serves as a benchmark in defining Russia’s survival. In other words, the creation of the enemy functions as an instrument of ontological position. Finally, based on the work of Esposito and Butler, we find that enemy-based foreign policy accomplishes a dual function of separating lives worthy of mourning from those that are not: it allows the killing as a way to eliminate the Other, but at the same time reinforces the inner life of the political body through annexation, which is used to guarantee immunity from the Other.

RÉSUMÉ

L'objectif principal de cette recherche est d'établir le cadre analytique de la politique étrangère basée sur l'ennemi afin de comprendre certaines actions de la politique étrangère de la Russie à l'égard de l'Ukraine pendant l'invasion de 2022. À travers une revue de la littérature sur la construction de l'ennemi, l'analyse de sources académiques et journalistiques, ainsi que l'analyse des discours de Vladimir Poutine et d'autres positions officielles du Kremlin, nous déterminons que la politique étrangère de la Russie est orientée vers la reconfiguration de son identité dans le système international à travers la désintégration de l'Ukraine, et qu'elle sert en même temps de point de repère pour définir la survie de la Russie. En d'autres termes, la création de l'ennemi fonctionne comme un positionnement ontologique. Enfin, sur la base des travaux d'Esposito et de Butler, nous constatons que la politique étrangère basée sur l'ennemi accomplit une double fonction de séparation de vies dignes de deuil de celles qui ne le sont pas : elle autorise la tuerie comme moyen d'éliminer l'Autre, mais renforce en même temps la vie intérieure du corps politique par l'annexion, qui est utilisée pour garantir l'immunité contre l'Autre.

Introduction

The construction of analytical frameworks for the study of foreign policy offers approaches to decision-making processes (Allison, Citation1971; Potter, Citation2010), the definition of interests, behavior (Brecher et al., Citation1969), and the relations between the actors involved (Carlsnaes, Citation1992). These visions have generally been associated with contexts of relative calm and balance of power. Nonetheless, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the previous approaches may converge in a new framework: enemy-based foreign policy.

This study recognizes that there has been important literature on foreign policy, but at the same time, there is a gap in the study of foreign actions taken by some state actors to eliminate others. The leading literature in foreign policy has emphasized that its analysis is characterized by a focus on actors and roles, based on the fact that what happens between states is due to the incentives of human decision-makers acting individually or in groups (Holsti, Citation1970; Hudson, Citation2005, p. 1). In fact, it was traditionally considered that the intrinsic motivations of an actor mold the forms and conduct of foreign policy (Rose, Citation1998; Rosenau, Citation1966), but this lacks a deeper exploration of the ontological justifications regarding the extrinsic causes that make a state adopt certain positions in relation to others, for example, trying to destroy them. Therefore, enemy-based foreign policy is the analytical framework that bridges intrinsic and extrinsic causes. To develop this idea, this research takes the particular Russian military aggression led by its leader, Vladimir Putin, against Ukraine that began in February 2022 as a case study. With this, it is not intended to indicate that the enemy-based foreign policy starts with Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, but rather that it serves as a context within which to build the analytical framework.

The justifications for Putin’s actions can be traced back to events that are not as widely acknowledged by the West, such as NATO’s expansion towards the Russian border, the overthrow of Gaddafi with false promises, and the forced withdrawal of the Ukrainian president Yanukovych in 2014 and the resulting crisis. These events, according to Cohen, led to Putin’s reactive measures in response to a perceived threat from the West (Kovalik, Citation2015) which is inferred in Putin’s speeches –reviewed in this study– to justify the invasion of Ukraine.

In this context, Putin’s approach to foreign policy towards Eastern Europe is confrontational and views the West as the aggressor, while Russia is reacting to protect itself (Cohen, Citation2017). The Russian discourse and media construct Russian identity, in an intersubjective process (Wendt, Citation1999) that is not one-way. However, this does not necessarily mean that Putin’s interpretation is true or false.

In this research, we construct the analytical framework of enemy-based foreign policy in order to analyze Russian actions towards Ukraine through the “special military operation” announced by Putin. Therefore, the question that guides this article is: How do Russia’s political actions reflect an enemy-based foreign policy in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine? The article uses a literature review, analysis of academic and journalistic sources, and discourse analysis, to perform a qualitative analysis of Russia’s foreign policy. To this end, we used the MAXQDA software.

The analysis shows that Russia’s focus is on redefining its identity in the international system by disintegrating Ukraine, which serves as a benchmark for Russia’s survival. The creation of an enemy is used as a tool for ontological location. The concept of understanding foreign policy as both elimination and immunization is valuable in anticipating actions from neighbors in conflict areas and can be used to develop national security policies. Viewing Moscow’s actions through the lens of enemy-based foreign policy allows for alternative ways to understand survival and contestation vis-á-vis its neighbors, different from a simple direct confrontation. It also helps policymakers understand how the Russian notion of enmity can turn into aggression and find ways to avoid violence. Reducing Russian actions to totalitarian or imperial impulses only leads to further military defense.

The article is organized as follows: first, we outline the methodology used. Second, we explain why Russia is constructing Ukraine as its enemy through revisionist historical features that help to clarify the current behavior of Putin. Third, we develop the analytical framework of enemy-based foreign policy as an agenda under construction. Fourth, we show the link between the conceptualization of the construction of the enemy and Putin’s discourse, and evidence of the forms and ways through which Russia has undertaken Ukrainian disintegration. Fifth, some final considerations are indicated where we suggest this analytical framework as an instrument for new analyses in foreign policy.

Methodology

The article used a qualitative-descriptive analytical model to develop the analytical framework of enemy-based foreign policy. This involved conducting a literature review to collect information on the principal factors that constitute a state’s foreign policy, and then extracting central elements to characterize foreign policy based on ontological justifications for the disintegration of the Other. The review used a Boolean equation to search databases such as SCOPUS, Taylor and Francis, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search yielded 78 documents, which were filtered to focus on the topic studied. The review identified four factors – interests, decision-making, behavior, and relationship to others – that were relevant to the proposed analytical framework, even though they had been studied during times of peace (Beasley et al., Citation2002; Brecher et al., Citation1969; Hudson, Citation2005; Potter, Citation2010; Rosenau, Citation1966). The characterization of each of these is shown in and is built from the conceptualization provided by the vast literature. Then, a review of the literature was carried out on the topic of enemy-based foreign policy in the context of Russia and Ukraine to explain why Ukraine is Putin’s enemy. At this point, theoretical sources as well as the official document of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (Citation2023) were reviewed.

Table 1. Factors of foreign policy from theory.

Considering these factors and their role in outlining the foreign policy of a state, we analyze Putin’s discourse delivered in three different speeches: the first, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” published in article format in July 2021 on the official Kremlin website (Putin, Citation2021), the second in the speech addressed to the nation on February 21, 2022 after the Russian military move to the Ukrainian border, and the third in the speech announcing the military operation in Ukraine on February 24 of the same year. Due to the ongoing nature of the conflict, this study relied on these sources because Putin’s speeches easily explain the reason for the “special military operation”, and thus to understand Russia’s actions. In Putin’s view, recent Western-Russian relations suggest an attempt by the West –understood in principle as the United States of America and its great NATO allies- to make Russia an outsider country without any relevance in the international scene, to the point of isolating it (Cohen, Citation2014).

Hence, Putin’s speeches were analyzed to identify the four factors mentioned in , thus establishing a primary relationship between what is presented in the conceptualization of the construction of the enemy and Putin’s discourse. This part also made it possible to identify a fifth factor that complements the analytical framework proposed in this research. This factor is the justification and it helps, with the other four factors, to materialize the enemy-based foreign policy as seen in . For this documentary analysis, the MAXQDA software was used through the deductive coding of the code system that the tool allows.

Table 2. Enemy-based foreign policy as an analytical framework.

The words with the highest frequency in the speech text that indicated a correspondence with the idea of the enemy were selected to determine the intensity of these words in the discourse and clarify whether the construction of the enemy was evident in the foreign policy factors from the discourse used. The word cloud instrument in MAXQDA was used for this purpose. The article also reviewed some of the most relevant actions of Russia against Ukraine documented by media outlets to demonstrate a direct correlation between the theoretical, the textual discourse, and the actions taken.

Our analysis found a correspondence between Putin’s speeches and the actions taken by Russia. At this point, it is important to clarify that, given the recent nature of the events, the actions considered for the study go as far as Russian attacks on Ukraine’s energy grid in October 2022.

Why is Ukraine Putin’s enemy?

From a historical approach, the Soviet vision cultivated under Stalin’s regime excluded connections and influences from the world outside its borders. This characteristic defined the Russian identity because all foreign matters were considered to be threats. Therefore, when Ukraine became independent from the Soviet Union, it became its enemy (Melnikova, Citation2013, p. 46).

The Kremlin’s ideology of multiple civilizations and resistance to Western hegemony includes Slavophilia. This vision of Slavic solidarity may still involve using Pan-Slavic rhetoric as a smokescreen for hegemonic politics, a tactic used by Russian political elites since the mid-nineteenth century (Gaufman, Citation2017).

Modern Russian conservatism lacks an organic nature and primarily exists to support the current semi-authoritarian regime in Russia. Putin uses the same rhetorical strategy as Russian nineteenth-century conservatives to maintain his legitimacy by decrying the “liberal” Yeltsin era. The annexation of Crimea brought conservative thought about Russian greatness to the forefront, exposing fundamental ideological inconsistencies such as its confrontation with the West, despite having Western origins. This led to the fragmentation of the conservative movement, with diverging attitudes towards the Kremlin’s Ukraine policy (Gaufman, Citation2021).

The Pan-Slavic discourse in Russian attitudes towards the West highlights the identification of Western Europe with Germanic presence and aggressiveness (Suslov, Citation2023, p. 36), which allows the Kremlin to construct a narrative that links the latter with the “Great Patriotic War” and justify its war against Ukraine as a war against fascism (Gaufman, Citation2021, p. 120). Pan-Slavism implies that independence might mean separation from the “core of the Slavic Civilization – Russia,” creating an underlying inconsistency in Russian attitudes towards the West (Suslov, Citation2023; Gaufman, Citation2021).

Russian foreign policy has undergone both continuities and discontinuities from the Stalin era to the Putin era (Gaufman, Citation2017; Grachev, Citation2005). Continuities include the pursuit of a strong and respected global power status, the use of military force to protect national interests, and the policy of containment towards the West (Tucker, Citation1977). However, discontinuities can also be observed in the shift from Stalin’s isolationist foreign policy to Putin’s integration of Russia into the global economy (Rubinstein, Citation1964), and pursuit of friendly relations with some Western countries (Cohen, Citation2014, Citation2017). Another major difference is Putin’s strategy of strengthening ties with China, whereas Stalin saw China as a potential threat (Doris & Graham, Citation2022; McFaul & Götz, Citation2020). Additionally, if one were to follow Cohen’s reasoning, the attitude towards its neighborhood has shifted from Stalin’s imposition of his political model to Putin’s pursuit of more balanced and respectful relations.

However, looking at the official document titled “The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation” by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (Citation2023), it gives us another picture. The document highlights Russia’s intention to eliminate the vestiges of domination by unfriendly states in global affairs and strives towards a multipolar system of international relations based on diversity of cultures and civilizations, non-imposition of development models and values, and reliance on a common spiritual and moral guideline. The document warns against the imposition of destructive neoliberal ideologies that run counter to traditional spiritual and moral values.

The reiteration of the claim that the current international system is based on spiritual and moral values that have a detrimental effect on the current system, as highlighted by Sakwa (Citation2011), is evident throughout the text. The supposed endorsement of Russian spiritual and moral values may suggest a binary opposition that posits that the current system is flawed. Sakwa argues that Russian elites perceive certain principles of international politics as imposed and, therefore, that they should be considered instrumental and lacking vitality (Citation2011). This discourse is intended to be read alongside the pan-Slavic narrative that opposes fascism and challenges a naturally aggressive international order.

To understand why Ukraine is viewed as the enemy by Russia, it is important to consider historical events such as the division of Ukraine’s territory between Russia and Austria-Hungary in the nineteenth century and Ukraine’s recent rapprochement with NATO in the twenty-first century. Ukraine has experienced divisions in its territory since World War I, and the beginnings of a nationalist movement and desire for statehood became evident. However, Russia has denied Ukraine’s existence and the possibility of statehood, as evidenced by former Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov’s statement at the Paris Peace Conference (Mankoff, Citation2022) and Putin’s statement to former US president George W. Bush.

Stalin took over Ukrainian territories in World War II, leading to the installation of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and its later annexation to the USSR (Wertsch, Citation2000). Nationalist movements returned in the 1990s after Ukraine gained independence from the USSR. Education and language policies during this period were based on Russian ideals, which strengthened roots in Crimea, Donetsk, and Lugansk (Wertsch, Citation2000). Despite this, a 1991 referendum showed over 80 per cent of the population voting on the Act of Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, with 90 per cent in favor, according to a report by the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, Citation1992.

Russia has attempted to regain Ukraine in various ways, including through interference in Ukrainian politics, as seen with Yushchenko and Yanukovych (Mankoff, Citation2022; Volgy et al., Citation2011), or directly with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia’s sentiment towards Ukraine is based on its unwillingness to lose said territory, as it would diminish their unity and prevent geographical expansion, which gives them security on the international stage. It would also indirectly give the West a territory Russia has always seen as its own. This threatens the modern reconfiguration of Russia’s identity and jeopardizes its goal of being considered a relevant and influential actor in the current international system (Hansen, Citation2016; Volgy et al., Citation2011). This is especially true due to the wound left by the idea spread by the West about the failure of the USSR, which has undermined Russia’s status as a power (Hansen, Citation2016; Mankoff, Citation2022; Sakwa, Citation2011; Volgy et al., Citation2011).

The strategic stance of the Putin regime on Ukraine comprises a complex dimension. Their approach includes the thesis that there are pro-Russian regions in Ukraine and that a hypothetical accession to NATO threatens the country’s disintegration (Carment & Belo, Citation2022; Nikolko & Carment, Citation2017). This stance justifies the notion of a Ukrainian threat to Russian identity (Gaufman, Citation2017). Therefore, as Ukraine is a divided country, Russia has argued that its “special military operation” in February 2022 is based on the need to liberate pro-Russian regions and bring them back to where they originally belonged (Carment & Belo, Citation2022).

To this extent, the above is evidenced when looking at the current leaders of Russia’s foreign policy for the invasion of Ukraine, who have based their decisions on the enemy. The most relevant ones are President Vladimir Putin, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, Secretary of the Security Council Nikolai Patrushev, Deputy Chair of the Security Council of the Russian Federation Dmitry Medvedev, and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. By Putin’s appointment, Shoigu and Patrushev oversee Russia’s military and security strategy and are playing a key role in the planning and execution of the invasion of Ukraine.

The implications of Ukraine’s nationalist signs, the time elapsed since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opportunities brought by commercial exchange with Europe, led to a growing closeness between Ukraine and the West to the point where Ukraine sought integration with the European Union in the twenty-first century, a factor that exacerbated Russia. If one adds Ukraine’s attempts to get closer to NATO, this lays the groundwork for Russia identifying the West as the enemy and Ukraine as the means to materialize it.

Russian foreign policy has been extensively studied, and several historical approaches deal with the former empire and the USSR (Moulioukova & Kanet, Citation2021). The studies provide a narrative about the history of Russian foreign relations and a framework within which Russia sees its place in the world and the configuration of its foreign policy, but without details of any particular policy decisions (Moulioukova & Kanet, Citation2021, p. 840). A key concept in this narrative is the self-perception as a great power, influenced by its objective capabilities and its subjective aspirations (Feklyunina, Citation2018; Levinson, Citation2022; Mankoff, Citation2022; Sakwa, Citation2011). For Moulioukova and Kanet (Citation2021), imperial nostalgia and the need to find continuity of its place in the system can help explain why Moscow is often a challenging actor.

Enemy-based foreign policy: an agenda under construction

Justifying the existence of the Other as an enemy is both an ontological (Krickel-Choi, Citation2022) and discursive process (Hilmy, Citation2009). The enemy thus becomes a dehumanized “other” whose destiny is elimination. Putin’s political and military stance on Ukraine is a demonstration of this. He configured a means of annihilation, a foreign policy that positions everything not aligned with the interests of Moscow as its enemy, and materialized his doctrine on Kiev to redefine its ontological position. While Russia’s invasion is a crime to the West, for Russia, its vision of Ukraine as its enemy is necessary, while for Ukraine it becomes a question of survival (Snyder, Citation2022, july 26).

The intention of creating an enemy is to eliminate the threat they pose. An enemy is the Other in binary opposition to the self (Mitzen, Citation2006). The existence of the enemy defines the identity of the self, and provides a standard to justify their own existence, giving it an absolute nature (Eco, Citation2011, p. 7).

Schmitt’s idea of the enemy (Citation2007) remains relevant to foreign policy decision-making and international security. For Schmitt (Citation2007), the enemy is a threat to the state from within and must be destroyed at all costs, which creates a binary of friend/enemy. However, in foreign policy, the enemy is an external entity that endangers the integrity of the state, which means the enemy is not integrated in the heart of the political body.

Walker’s analysis (Citation1995) shows that the dichotomy of interior and exterior is fundamental to International Relations (IR) discourse, and that state sovereignty is central to most IR theory, as it enables the functioning of sovereignty-related binary oppositions (Walker, Citation1995, p. 6). Walker highlights the importance of the universality/particularity binary in relation to state sovereignty, which has often been viewed as a spatial characteristic. According to this dichotomy, the state represents universal control, sameness, and progress, while the outside is seen as a place of excessive multiplicity and national self-determination. Hence, the international is inevitably a space of difference and a negation of state universality, a modern inheritance that drives state authority to achieve stability by resolving the different into the same (Walker, Citation1995, p. 78).

The direct consequence of this understanding of sovereignty is, in Butler’s terms (Butler, Citation2002), that the international becomes the constitutive outside which gives meaning both to state authority and the modern idea of progress inside the border: whatever happens and whoever lives outside the state is immediately determined as the abject which needs to be reduced to “someone just like me” in order to be epistemologically/ontologically apprehended.

The need to establish an abject entity outside of borders as a constitutive move of sovereignty might suggest a Schmittian rationality that relies on the friend/enemy binary. However, the problem of the sovereignty/anarchy binary cannot be overlooked. (Neo)Realist thinking considers anarchy to be the primary condition that drives international interactions, with material variables being the sole determinant. Waltz’s definition of the system as a function of the distribution of capabilities ignores the social element of politics, transforming it into a mechanical interplay of like-units (Buzan & Albert, Citation2010). This move seems to forget that, in any structure, functional differentiation depends on the existence of roles (Wendt, Citation1999). Agents in social interactions attribute roles to each other, which over time become pervasive and take over as the “logic of the system”, forming collective beliefs about Otherness (Wendt, Citation1999, p. 264). Realist thought uses the enmity/friendship binary as roles, with Hobbesian anarchy as the narrative trope (logic of the system) that guides interactions based on what they “know about their roles [rather] than on what they know about each other, enabling them to predict each other’s behavior without knowing each other’s ‘minds’” (Citation1999, p. 264).

State sovereignty is yet another powerful and parallel trope to anarchy that uses the same roles and completes the Hobbesian logic. Ultimately, it follows a “heroic practice” (Ashley, Citation1988) aimed at rescuing the inside from the chaos, disorder and ambiguity of the outside with universal certainty and sameness. Hence, IR (but, mostly, Realist thought) gives a normative and binary depiction of the international system disguised as empirical description.

The move to exclude that which is “not the Same” responds to a thanatopolitical need to assert the sovereign’s authority through legal exclusion (Agamben, Citation2013). The true power of the sovereign is seen in the use of the law to suspend law itself, creating a situation of ontological (epistemological) indeterminacy which allows the excluded subject to be killed without moral and legal consequences. Agamben’s concept of bare life helps explain Putin’s actions in eastern Ukraine. Surkov, Putin’s former ideological advisor, argued that Ukraine does not exist (Düben, Citation2020), which represents a sovereign attempt to fabricate a legal condition of Ukrainian non-existence and reduce Ukrainians to bare life (Medvedev, Citation2023). This sovereign ban allows Russian policymakers to legitimize violent actions against Ukrainians.

This construction of Ukrainians as bare life allows for a thanatopolitical understanding of an enemy-based foreign policy: foreign policy is thus, on the one hand, an action that reinforces the sovereign’s own condition as such, and on the other, uses the power of the law to assert authority. Against this backdrop, Putin’s statement about Ukraine’s non-existence serves his epistemological standpoint: one cannot regret the death of someone who is not considered to be alive from the start. In this way, Ukraine and its people become a constitutive outside that serve the purpose of guaranteeing Russia’s ontological and identitarian security.

Putin’s enemy-based foreign policy is a result of the construction process of Russian security and insecurity (Tsygankov & Tsygankov, Citation2021), where the security of Russia is dependent on the existence of an “other,” which, in this case study, is Ukraine. This creates negative ontological security and nourishes the reasons to invade Ukraine. As a result, military invasion and war become the means to define Russianness, the ethos of confrontation and national redemption.

The ethnocentric vision from the perspective of Putin’s foreign policy warns that the Russiancentric idea becomes the measurement of everything. Under such a measure, Western posture aims to prevent Russian imposition, thus unleashing an “anger” that seeks to overcome extrinsic inhibitions and restrictions (Butler, Citation2021, p. 181) and further legitimizes the enemy-based foreign policy pursued by the Kremlin.

However, certain authors, such as Sakwa (Citation2011), Cohen (Citation2014, Citation2017), Levinson (Citation2022), Medvedev (Citation2023) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Citation2023) argue that the Russian position is not an imperial imposition but a consequence of the attacks that come from the West; hence, Moscow needs to defend itself. All of this would explain Russia’s enemy-based approach to foreign policy.

Vladimir Putin’s discourse and its link with the conceptual framework

To analyze a state’s foreign policy, one needs to consider the four classical factors of interests, decisions, behaviors, relationships between actors, and a new fifth one: the justification to attack. This five-factor framework is essential for understanding enemy-based foreign policy, which is characterized by a violent future aimed at the disintegration of the enemy. In the case of Russia’s current policy towards Ukraine, these factors are present, leading to the construction of an enemy-based foreign policy. Such an assumption would only define the war partially, limiting the objective of what enemy-based foreign policy pursues.

The enemy construction is based on the state’s need for recognition and validity in the system, with any restriction or opposition representing a threat. The Russian and Slavophile identity determines the interest at stake: Putin finds its origins in the past as the intrinsic causes for his decision to invade Ukraine, and it directs the extrinsic causes for enemy-based foreign policy. The Kremlin’s July 2021 publication “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” reveals a nostalgic tone for the loss of Ukraine and hints at the possibility of eventual reunification, with frequent use of words indicating “union” between Ukraine and Russia. The most frequently used word in the analyzed documents was “'Ukraine” (37.25 per cent), followed by “Russia” (27.18 per cent). The documents emphasize historical unity between the two countries, using the word “union” 18 times.

However, one of the events of the last century that marks Russia’s desire to become its former self dates back to the collapse of the USSR in 1991. This situation meant, to a large extent, the disintegration not only of the Russian Union around socialist republics, but also the disintegration of a great power recognized on the international stage.

In this context, Russia’s decision-making process involves pursuing its interests and countering threats from third parties. Western interference in Ukraine hinders Russia’s aspirations for reunification and reconfiguration. To achieve its interests, Russia employs strategies that correspond to the threats at hand, such as invading to prevent losing the whole, even if it comes with costs. The analyzed documents show that Russia is concerned about “external forces” which threaten its ideals through manipulation of Ukrainian nationalism. The phrase “external forces” is related to the word “Western” which appears with a frequency of 4.36 per cent.

From the events of the past related to Ukraine and the West, Russia’s actions have defined a warlike behavior in the construction of enemy-based foreign policy and, from there, its relationship to the actors involved. On this occasion, the documents that best reflect Russia’s behavior in its relations to the actors involved are the speeches addressed to the nation on February 21, 2022 after Russian military deployment to the Ukrainian border and the speech announcing the “special military operation” in Ukraine on February 24. In these speeches, words such as “threat”, “sovereignty”, “protect”, “arm”, and “military” gain relevance after the invasion and, in turn, demonstrate the behavior of what enemy-based foreign policy represents.

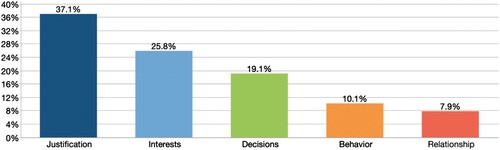

The above is observed through the deductive content analysis carried out in MAXQDA. Thus, Putin’s speeches are categorized through the five factors of foreign policy (interests, decisions, behavior, relationship, and justification). This makes it possible to identify that the interventions present a high level of concentration in justifying Russia’s actions against Ukraine with 37 per cent, followed by interest and decision factors with almost 25.8 per cent and 19.1 per cent respectively, as can be seen in .

Figure 1. Foreign policy factors on Putin’s speeches analyzed. Source: Own elaboration based on Vladimir Putin’s speeches.

After revising Russia’s actions against Ukraine, the implementation of enemy-based foreign policy is evident. These actions denote, first, the interest of the reconfiguration of Russia’s identity by mobilizing military troops to the Ukrainian border and the subsequent annexation under referendums of the Ukrainian territories of Luganzk, Donetsk, Zaparozhye and Kherson. In second place are the missile and drone attacks against various Ukrainian cities, causing damage in the country’s infrastructure. Those actions represent not only the decision taken to achieve Russia’s interest, but the means to do so despite the economic and political costs they represent. Finally, there is a defiant relationship towards the actors involved, by responding to the economic and political sanctions imposed on Russia by the West through one of its weapons: the gas industry.

The literature review’s conceptual elements are related to Putin’s statements and materialized in Russia’s actions towards Ukraine, reflecting an enemy-based foreign policy as a framework under construction. MAXQDA analysis reveals a word count and frequency that supports this framework. These processes determined that the central themes of Putin’s discourse are around “Ukraine”, “Russia”, the identification of what is “ours”-meaning Russia’s- and “our own” in relation to the unity of these countries and, in turn, “Soviet”, “empire”, “territory”, “state”, “duty”, “military”, and “unity”, among others, as shown in of the word cloud of the documents analyzed by the software.

Figure 2. Central themes of Vladimir Putin’s discourse. Source: Own elaboration based on Vladimir Putin’s speeches.

Consequently, in the last two decades, Putin has gone from “the great unknown” to “the new tsar” (Isachenko, Citation2019, p. 1479), occupying a central place in Russian politics and standing out for his outward attempts to invoke revisionist logics of the Russian state. Thus, Putin’s foreign policy posture, as enemy-based foreign policy, is less a reaction to external pressures and more a pattern driven by internal factors: embedded routines of the country’s ontological security and quest for continuity of its place in the world (Isachenko, Citation2019; Moulioukova & Kanet, Citation2021, p. 848).

Elias Götz and Jørgen Staun (Citation2022), suggest that the Putin-commanded invasion of Ukraine was driven by two main elements: a deep-seated sense of vulnerability vis-à-vis the West and a sense of entitlement to great power status. Indeed, Putin perceived Ukraine’s trajectory towards the European project and NATO as a threat to both Russia’s security interests and its geopolitical aspirations (McFaul, Citation2020). As a result, Russia’s rhetoric regarding Ukraine was radicalized by configuring it as the enemy to destroy (Götz & Staun, Citation2022). For McFaul and Götz (Citation2020), President Putin’s anti-liberal worldviews are an important driver of Russia’s international behavior in a context of multiple orders (Flockhart & Korosteleva, Citation2022). There are some popular hypotheses on why Russia decided to militarily attack Ukraine. On one hand, the historical revisionism that defines certain discursive attitudes of Putin emulates imperial positions (Liik, Citation2022; Mueller, Citation2022), on the other hand, there is the exacerbated rigidity of the autocratic regime to unite Russian identity (Youngs, Citation2022), and finally, the NATO enlargement that causes unease in the Kremlin (Williams, Citation2022).

Final considerations

If Ukraine is under threat by Russia in 2022, it is because of the democratic opportunity Russia let slip away between 1991 and 1999 (Ignatieff, Citation2022). Putin’s distaste for democracy reinforces his objections to NATO because the organization’s expansion played a major role in the 2022 invasion (Doris & Graham, Citation2022). The above suggested an adversarial approach and a challenge to its supremacist belief system. Democracy implies hostility toward Moscow and, in the long run, a strong democratic impulse could lead to Putin’s decline because his autocratic neighbors are more prone to influence (Doris & Graham, Citation2022, p. 81).

Indeed, Putin gave a speech on February 21, 2022 in which he listed, according to him, the causes and justifications for a “special military operation” in Ukraine (Reuters, Citation2022). It was evident that the main impetus for the assault on Ukraine was the legitimacy of Ukrainian identity, the state, and its right to exist (Mankoff, Citation2022). During the Putin era, the Kremlin has sustained an absorbing imperial narrative in which modern states such as Ukraine and Belarus must share a unique future and unity with Russia (Mankoff, Citation2022, p. 1). In fact, in 2008, Putin assured George W. Bush that Ukraine is not even a country (Remnick, Citation2014). Within Putin’s revisionism, history is revisited to show that before Ukraine’s “neo-Nazis” there were Hitler’s Nazis and that it is Russia’s duty to reshape the order and save the world (Mankoff, Citation2022; Meyer, Citation2022).

In April 2022, Timofei Sergueitsev justified de-Ukrainizing and de-Europeanizing Ukrainian territory by denazifying Zelensky’s government, which would also require the abolishment of Ukraine’s name (Sergueitsev, Citation2022). This supports the idea of the enemy, as well as the reasons to implement its disintegration by means of military aggression, “what Russia should do with Ukraine is destroy it” (Remnick, Citation2014; Sergueitsev, Citation2022). For Sergueitsev and thus for Putin’s government, achieving Russia’s ultimate goal requires both establishing institutions dedicated to de-nazifying the country and forbidding any kind of educational material containing Ukrainian ideological patterns (Sergueitsev, Citation2022). In addition to Sergueitsev, Aleksandr Dugin seemed to be another source of influence on Putin’s conception of the world (Barbashin & Thoburn, Citation2014).

Within the framework of enemy-based foreign policy, the enemy is necessary to sustain an ontological thesis of the one who wishes to destroy it. In other words, projecting the process of “denazification” for 25 years suggests that the war may be long and that the Russian military approach is the clearest bet for the disintegration of its enemy. In Ukraine, especially in Mariupol, Putin is repeating the Grozny doctrine implemented in Chechnya in 1999. Consequently, the disintegration of Ukraine and its respective de-Ukrainization is the way to establish the identity that the Russian government believes corresponds to Russia.

Putin’s foreign policy decisions, while strongly framed as security concerns, aim at the construction of Russian identity linked to its past power, glory and capacity in the European space. Following his words during his address on February 21, 2022, Ukraine was, in his view, created by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in 1917. This is consistent with several other statements by Russian government officials, such as Medvedev stating in 2016 that there is “no state in Ukraine”, or Vladislav Surkov saying in an interview in 2020 that there is no Ukraine yet, but that Ukrainians will come around and “make it” (Surkov, Citation2020).

However, the thanatopolitical drive to enact lethal violence on Ukrainians (while explaining how Ukraine is framed as the enemy or the bare life whose death is needed to legitimize Russian sovereign rule) is a partial narrative that does not explain why and how the deployment of death to produce sovereignty is coupled with an equally strong plead to integrate Ukraine and defend the lives of Russian-Ukrainians. This discourse, which is evident in Putin’s own speeches about, on the one hand, defending Ukrainians in Donbass from a Nazi European incursion (Putin, Citation2022), and on the other, about continuing the war, reflects a paradox constitutive of the enemy-based foreign policy: such a foreign policy aims to both establish sovereignty by excluding and throwing the outsider into a space of indeterminacy and, at the same time, to assimilate the Other as a means of inoculation against the particularity of the international system.

This aporia of simultaneously annihilating and assimilating is unsolvable through a thanatopolitical (and perhaps rather Realist) understanding of foreign policy. The attempt to annex Ukraine responds, rather, to a vitalist drive to isolate the Russian space from the influence of a growing process of Europeanization (framed as nazification and, recently, satanization) in Eastern Europe. In this sense, the concept of “immunitas” proposed by Esposito (Citation2017) is useful to capture the vitalist dimension of an enemy-based foreign policy. Behind the idea of immunitas lies the fact that immunity is both a juridical and a medical concept: to be immune means to be exempt from the law and, simultaneously, to acquire protection from a disease by accepting a small part of it to build defenses. As Esposito argues, the prophylactic function of the immunological mechanism not only presupposes the existence of the disease which it must fight, but also does so by reproducing, in a controlled manner, that same illness in order to use it (Esposito, Citation2017, p. 17). The body politic constantly uses strategies to achieve immunization from the community, which is deemed dangerous to self-identity: nothing can reinforce the body politic better than dominating illness and turning it against itself (Esposito, Citation2017, p. 176).

The ideas that lie behind Russian ethnonationalism, such as practically being the same people, is a foreign policy discourse with the double function of justifying war and death, but also to seek a reason to insert Ukraine into the Russian body (politic) to achieve immunization against all that is not Russian. Putin’s speeches as part of his foreign policy thus work as a frame (Butler, Citation2016) that guarantees a differential distribution of recognition, suffering and grieving: if Ukraine can exist only as part of Russia, then anyone who opposes the Russian version of history, as long as they were also part of the Russian notion of “Motherland” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Citation2023), is immediately deemed as unworthy of mourning, purged in a medical sense through the power of death or forced into healthiness by annexation to legitimize Russian identity and security. This is what enemy-based foreign policy really is: it is a foreign policy that frames the Other as both outside of the law and the body politic, facilitating the elimination of the illness without moral consequences, and also as a vital part of the body politic to inoculate it from the disease of communitarian life.

The benefit of this approach lies in the fact that an enemy-based foreign policy clears some degree of noise in the current foreign policy analysis literature (Hudson, Citation2005). It would seem most of the methodological contributions to the field still fall in an either/or way of understanding foreign policy action regarding war: either war for the sake of hard power, or for soft power. However, these interpretations do not capture the fact that both reasons can be complementary. Eliminating an enemy to re-legitimize sovereignty is not necessarily opposite to integrating said enemy to gain protection from another “other”. This solves the classical (Neo)Realist way of interpreting conflict simply as action/passivity, attacker/defender, secure/insecure actor.

This research aims, in part, to serve as an input for future foreign policy analysis in terms of enemy-based foreign policy, and we also open the door to foreign policy analysis from the perspective of performativity (Butler, Citation2010) by seeing it as constitutive of political identities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

César Niño

César Niño is Associate Professor and Researcher in International Relations at the Universidad de la Salle (Colombia). He has a PhD in International Law from the Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio (Spain), and is currently a PhD student in International Peace, Conflict and Development Studies at the Universitat Jaume I (Spain). His research areas include international security, conflict, terrorism, violence, peace, and organized crime. mail: cninounisalle.edu.co.

Lucas d'Auria

Lucas d'Auria is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Universidad de La Salle (Colombia). He holds a MSc in International Relations Theory from the London School of Economics and Political Science. His areas of research include Critical Security Studies, migration politics and theories of International Relations. mail: ldauriaunisalle.edu.co.

Ángela Cristina Pinto

Ángela Cristina Pinto Member of the Faculty of Economics, Business and Sustainable Development as Assistant Research Professor at La Salle University, Bogotá, Colombia. Magister in International Studies, Montreal University, Canada. mail: apintoqunisalle.edu.co.

References

- Agamben, G. (2013). Homo Sacer I: El Poder Soberano y la Nuda Vida. Pre-Textos.

- Allison, G. (1971). Essence of decision: Explaining the Cuban missile crisis. Little Brown.

- Ashley, R. (1988). Untying the sovereign state: A double Reading of the anarchy problematique. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 17(2), 227–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298880170020901

- Barbashin, A., & Thoburn, H. (2014, March 31). Putin’s brain. Alexander Dugin and the philosophy behind Putin’s invasion of crimea. Foreign Affairs.

- Beasley, R. K., Kaarbo, J., Lantis, J. S., & Snarr, M. T. (2002). Foreign policy in comparative perspective: Domestic and international influences on state behavior. CQ Press.

- Brecher, M., Steinberg, B., & Stein, J. (1969). A framework for research on foreign policy behavior. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 13(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200276901300105

- Butler, J. (2002). Cuerpos que Importan: sobre los límites materiales y discursivos del “sexo”. Paidós.

- Butler, J. (2010). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York and London: Routledge Classics.

- Butler, J. (2016). Frames of War: When Is life grievable? Verso.

- Butler, J. (2021). La fuerza de la no violencia. Paidós.

- Buzan, B., & Albert, M. (2010). Differentiation: A sociological approach to international relations theory. European Journal of International Relations, 16(3), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066109350064

- Carlsnaes, W. (1992). The agency-structure problem in foreign policy analysis. International Studies Quarterly, 36(3), 245. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600772

- Carment, D., & Belo, D. (2022, February 28). The Russia-west standoff: ‘Locked into war’. The Institute for Peace & Diplomacy. Challenging the Conventional, Rethinking Foreign Policy.

- Cohen, S. F. (2014, February 13). Distorting Russia. How the American media misrepresent Putin, Sochi and Ukraine. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/distorting-russia/.

- Cohen, S. F. (2017, March 29). The Sovietization of the American Political-Media Establishment?. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/the-sovietization-of-the-american-political-media-establishment/.

- Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe. (1992). The December 1, 1991. Referendum/Presidential Election in Ukraine. https://www.csce.gov/sites/helsinkicommission.house.gov/files/120191UkraineReferendum.pdf.

- Doris, A., & Graham, T. (2022). What putin fights for. Survival, 64(4), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2022.2103258

- Düben, B. A. (2020, July 1). “There is no Ukraine”: Fact-checking the Kremlin’s version of Ukrainian history. LSE International History Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lseih/2020/07/01/there-is-no-ukraine-fact-checking-the-kremlins-version-of-ukrainian-history/.

- Eco, U. (2011). Construir al enemigo (Building the enemy). Lumen.

- Esposito, R. (2017). Immunitas: Protección y Negación de la Vida. Amorrortu Editores.

- Feklyunina, V. (2018). International norms and identity. In Andrei Tsygankov (Ed.), Routledge handbook of Russian foreign policy (pp. 5–22). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Flockhart, T., & Korosteleva, E. A. (2022). War in Ukraine: Putin and the multi-order world. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(3), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2091591

- Gaufman, E. (2017). Security threats and public perception digital Russia and the Ukraine crisis: Digital Russia and the Ukraine crisis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gaufman, E. (2021). Contemporary Russian conservatism. Problems, paradoxes, and perspectives. Europe-Asia Studies, 73(2), 413–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2021.1880780

- Götz, E., & Staun, J. (2022). Why Russia attacked Ukraine: Strategic culture and radicalized narratives. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2082633

- Grachev, A. (2005). Putin’s foreign policy choices. In Alex Pravda (Ed.), Leading Russia: Putin in perspective: Essays in honour of Archie Brown (pp. 255–274).

- Hansen, F. S. (2016). Russia’s relations with the west: Ontological security through conflict. Contemporary Politics, 22(3), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2016.1201314

- Hilmy, M. (2009). Masdar Hilmy_manufacturing the “ontological enemy”. Journal of Indonesian Islam, 3(2), 341–369. https://doi.org/10.15642/JIIS.2009.3.2.341-369

- Holsti, K. J. (1970). National role conceptions in the study of foreign policy. International Studies Quarterly, 14(3), 233. https://doi.org/10.2307/3013584

- Hudson, V. (2005). Foreign policy analysis: Actor-specific theory and the ground of international relations. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2005.00001.x

- Ignatieff, M. (2022, March 24). La historia nos trajo aquí. Letras Libres. https://letraslibres.com/politica/la-historia-nos-trajo-aqui/.

- Isachenko, D. (2019). Coordination and control in Russia’s foreign policy: Travails of Putin’s curators in the near abroad. Third World Quarterly, 40(8), 1479–1495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1618182

- Kovalik, D. (2015, July 7). Rethinking Russia: A Conversation with Russia Scholar Stephen F. Cohen. HuffPost News. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/rethinking-russia-a-conve_b_7744498.

- Krickel-Choi, N. C. (2022). State personhood and ontological security as a framework of existence: Moving beyond identity, discovering sovereignty. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2022.2108761

- Levinson, A. (2022, February 17). Dictarorship of “traditional values.” Levada Center. https://www.levada.ru/2022/02/17/diktatura-traditsionnyh-tsennostej/.

- Liik, K. (2022, February 25). War of obsession: Why Putin is risking Russia’s future. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/article/war-of-obsession-why-putin-is-risking-russias-future/.

- Mankoff, J. (2022). Russia’s War in Ukraine Identity, History, and Conflict.

- McFaul, M. (2020). Putin, putinism, and the domestic determinants of Russian foreign policy. International Security, 45(2), 95–139. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00390

- McFaul, M., & Götz, E. (2020). The power of Putin in Russian foreign policy. International Security, 45(2), 95–139. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00390

- Medvedev, D. [MedvedevRussiaE]. (2023, April 8). Why will Ukraine disappear? because nobody needs it. [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/MedvedevRussiaE/status/1644669039095037953.

- Melnikova, E. (2013). The ‘varangian problem’ science in the grip of ideology and politics. In Raymond Taras (Ed.), Russia’s identity in international relations images, perceptions, misperceptions: Vol. First (pp. 1–149). Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Meyer, J. (2022, October 4). El “Mein Kampf” de Putin. Letras Libres. https://letraslibres.com/politica/jean-meyer-mein-kampf-putin/.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. (2023, March 31). The Concept of the Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation. https://russiaeu.ru/en/news/concept-foreign-policy-russian-federation.

- Mitzen, J. (2006). Ontological security in world politics: State identity and the security dilemma. European Journal of International Relations, 12(3), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066106067346

- Moulioukova, D., & Kanet, R. E. (2021). Ontological security: A framework for the analysis of Russia’s view of the world. Global Affairs, 7(5), 831–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2021.2000173

- Mueller, J. (2022, August 2). The upside of Putin’s delusions: Russia’s disastrous invasion of Ukraine will reinforce the norm against War. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/upside-putins-delusions.

- Nikolko, M., & Carment, D. (2017). Post-Soviet migration and diasporas. From global perspectives to everyday practices (M. Nikolko & D. Carment, Eds.). Palgrave Macmillan. http://www.springer.com/series/14044.

- Potter, P. B. K. (2010). Methods of foreign policy analysis. In Oxford research encyclopedia of international studies (issue September) (pp. 1–28). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.34

- Putin, V. (2021). On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians. President of Russia. http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181.

- Putin, V. (2022). Address by the President of the Russian Federation. Retrieved from Official Internet Resources of the President of Russia: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828 on October 26, 2022.

- Remnick, D. (2014, March 10). Putin’S Pique. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/03/17/putins-pique.

- Reuters. (2022, February 21). Extracts from putin’s speech on Ukraine. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/extracts-putins-speech-ukraine-2022-02-21/.

- Rose, G. (1998). Neoclassical realism and theories of foreign policy. World Politics, 51(1), 144–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100007814

- Rosenau, J. (1966). Pre-Theories and theories of foreign policy. In Barry Farrell (Ed.), Approaches to comparative and international politics (pp. 27–92). Northwestern University Press.

- Rubinstein, A. (1964). Stalin’s postwar foreign perspective: A review. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 8(2), 186–193. https://about.jstor.org/terms. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200276400800210

- Sakwa, R. (2011). Russia’s identity: Between the “domestic” and the ‘international. Europe - Asia Studies, 63(6), 957–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2011.585749

- Schmitt, C. (2007). The concept of the political: Expanded edition. University of Chicago Press.

- Sergueitsev, T. (2022, April 3). Что Россия должна сделать с Украиной (What should Russia do with Ukraine?). РИА Новости. https://web.archive.org/web/20220403212023/https://ria.ru/20220403/ukraina-1781469605.html.

- Snyder, T. (2022, July 26). The State of the Russo-Ukrainian War. Thinking About. https://snyder.substack.com/p/the-state-of-the-russo-ukrainian.

- Surkov, V. (2020). Сурков: мне интересно действовать против реальности (Surkov: I’m interested in acting against reality). АКТУАЛЬНЫЕ КОММЕНТАРИИ (Actual Comments). https://actualcomment.ru/surkov-mne-interesno-deystvovat-protiv-realnosti-2002260855.html.

- Suslov, M. (2023). Russian Pan-Slavism: A Historical Perspective. In Mikhail Suslov, Marek Čejka, & Vladimir Ðorđević (Eds.), Pan-Slavism and Slavophilia in Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 35–46). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Suslov, M. (2023). Russian Pan-Slavism: A Historical Perspective. In M. Suslov, M. Čejka, & V. Ðorđević (Eds.), Pan-Slavism and Slavophilia in Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 35–46).

- Tsygankov, A., & Tsygankov, P. (2021). Constructing national values: The nationally distinctive turn in Russian IR theory and foreign policy. Foreign Policy Analysis, 17(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orab022

- Tucker, R. C. (1977). The emergence of Stalin’s foreign policy. Slavic Review, 36(4), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.2307/2495260

- Volgy, T. J., Corbetta, R., Grant, K. A., & Baird, R. G. (Eds.). (2011). Major powers and the quest for status in international politics. Palgrave-MacMillan.

- Walker, R. B. J. (1995). Inside/Outside: International relations as political theory. Cambridge University Press.

- Wendt, A. (1999). Social theory of international politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Wertsch, J. V. (2000). Narratives as cultural tools in sociocultural analysis: Official history in Soviet and post-Soviet Russia. Ethos, 28(4), 511–533. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.2000.28.4.511

- Williams, M. (2022, January 25). If Russia boosts its aggression against Ukraine, here’s what NATO could do. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/if-russia-boosts-its-aggression-against-ukraine-heres-what-nato-could-do/.

- Youngs, R. (2022). Autocracy Versus Democracy After the Ukraine Invasion: Mapping a Middle Way. - Carnegie Europe - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/07/20/autocracy-versus-democracy-after-ukraine-invasion-mapping-middle-way-pub-87525.