Following an exhausting process undertaken by Hamelin (Citation1960), the council of Laval University founded the Centre d’études nordiques (CEN) in April 1961. The CEN was then officially recognized on 2 August 1961 by an Order in Council of the Executive Council Chamber of the Government of Quebec, which provided the very first CEN grant to fund research in northern Quebec. In the early 1960s, the development of northern Quebec aimed at exploiting natural resources, particularly hydroelectricity (Payette and Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). The CEN was created to ensure the presence of French-speaking scientists in the circumpolar world, particularly in northern Quebec, which until then was less well-known than other northern regions such as northern Europe and Alaska. In 1961, the CEN had two main objectives: to carry out wide-scale research on several aspects of northern regions and to disseminate scientific results through a publication center and information library (Payette and Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Louis-Edmond Hamelin established three additional objectives for the CEN (Hamelin Citation1960): (1) ‘To make the North’, i.e. to produce outputs of many kinds from the North, whether intellectual, material or those that are visible in the landscape; (2) ‘To do the North’, i.e. to contribute to building an optimal system of life for the people who inhabit the North and (3) ‘To tell about the North’, i.e. to disseminate information about the North via specific education programs, publications and digital circulation.

Louis-Edmond Hamelin created an inclusive, multidisciplinary research center for the natural, human, and social sciences and directed the CEN during its first ten years. At the turn of the 1970s, the changing context for research funding forced the CEN to concentrate its efforts on the natural sciences (Payette and Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Through his rich personality and great sensitivity, Louis-Edmond Hamelin was an ardent defender of the rights of Indigenous peoples (Payette Citation2020). In his writings and conferences, and when he assisted to meetings, he discussed the importance of respecting various cultures and customs as well as the emancipation of Indigenous populations (Payette Citation2020). His autobiographies provide an invaluable perspective on the achievements and the personality of this man who defended the North all his life (Hamelin Citation1996, Citation2006). To underline his role as a visionary, the CEN named a boat used for coastal, river, and lake research in his honour during the 50th anniversary of the CEN (Vincent et al. Citation2011). This mobile maritime platform () is part of the Qaujisarvik network of CEN research stations ().

Figure 1. Professor Louis-Edmond Hamelin, during the inauguration in April 2011 of CEN’s scientific boat. The boat is named the Louis-Edmond Hamelin, in honor of the founder of the CEN

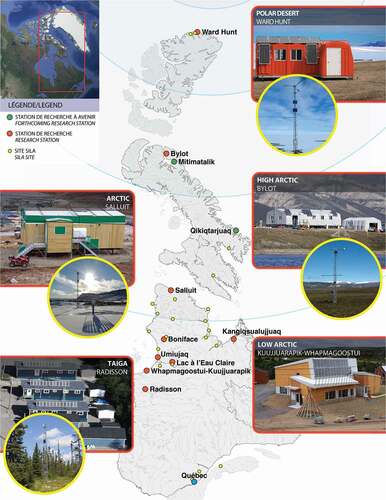

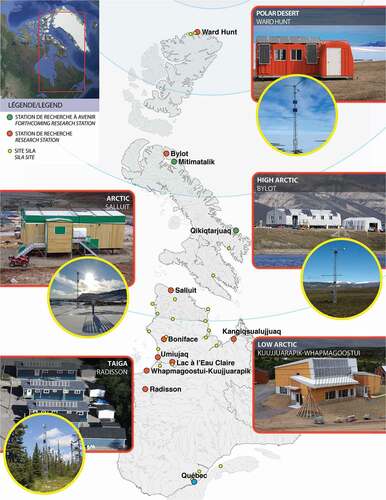

Figure 2. Locations of the research stations of the Qaujisarvik network, and of the environmental monitoring stations of the SILA network, operated by the CEN across a latitudinal gradient from the boreal forest to the polar desert. SILA stations are found at all Qaujisarvik research stations. Photographs: D. Sarrazin

Today, the CEN’s mission is to meet the challenges of research on nordicity in partnership with Indigenous communities by contributing to the sustainable development of northern regions by improving the understanding of cold environments and the ability to predict changes that affect them (CEN Citation2021). Due to remoteness, security issues and high logistical costs, the access to the North presents major challenges for research work. The realities of Indigenous communities must also be taken into account. The CEN was created 60 years ago to meet these challenges and to serve the needs of northern communities and the Government of Quebec. Such challenges are still relevant today. Over the decades, the CEN has developed unique know-how and strong relationships based on trust with Indigenous communities, as well as a set of pan-Canadian and international collaborations. The CEN is therefore in an excellent position to meet the challenges of the 21st century by expanding our understanding of the issues that increasingly affect northern environments, such as the impacts of climate change and accelerated socio-economic development. The CEN addresses these topics using a multidisciplinary approach, in close partnership with Indigenous communities. The CEN includes researchers from a dozen universities in Quebec and other Canadian provinces. Their fields of expertise are diverse such as periglacial geomorphology, limnology, plant and animal ecology, microbiology, paleoecology, geology, numerical modeling, hydrology, bioarchaeology, engineering, as well as remote sensing. With approximately 300 members (80 researchers, 186 graduate students, 18 postdoctoral interns, and 10 research professionals) the CEN is one of the main drivers of Quebec’s status as a hub of excellence in northern research, both in Canada and internationally.

To illustrate the CEN’s leadership in northern research, the next two sections focus on the Qaujisarvik and SILA networks in the North (), as well as the numerous partnerships with northern communities in northeastern Canada. In addition to the first five decades of CEN’s development (Payette and Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011), recent achievements and challenges it has faced during the past decade are described in the third section which includes a sub-section devoted to the prospects for northern research over the next decade. Finally, the articles in this special issue celebrating the 60th anniversary of the CEN are introduced and linked to the diversity of CEN’s research themes.

The CEN’s physical presence in the North

In addition to establishing a strategic group of scientists with expertise in multiple disciplines and community partners, the CEN set up a unique network of research stations, as well as an environmental monitoring network along a south-north gradient, from the boreal forest to the Arctic, over nearly 26 degrees of latitude (). These research infrastructures are used for various research projects in eight bioclimatic zones spread across Quebec and the eastern Canadian Arctic.

The first network established and managed by the CEN is called Qaujisarvik, from the Inuktitut term meaning a ‘place of study’. This network is made up of ten research stations, stretching over nearly 20 degrees of latitude from Jamésie in Quebec to the far north of Canada on Ellesmere Island (). These stations include all the facilities required for northern research (laboratories, meeting rooms, accommodations, kitchen, bedrooms, means of transport, field equipment, etc.) and are suitable for interaction with members of the communities in which they are located. They also provide essential logistical and scientific support to the CEN research teams and their partners. The stations of the Qaujisarvik network are used to study the state of ecosystems and geosystems in order to predict their responses to climate change via, for example, the study of the dynamics of permafrost, key plant and animal species, and natural and cultural landscapes. The projects carried out via the Qaujisarvik network are designed to meet the specific needs of the local communities (e.g. co-construction of projects, consultation, co-management of stations).

The second network currently includes more than 100 environmental and climatological monitoring stations (). It is named the SILA network, after a polysemous Inuktitut term, one of whose meanings refers to climate. This network of permanent observatories is for characterizing, quantifying, and evaluating the northern climate and environmental changes. The sites of the SILA network are equipped with multiple probes that record several parameters including air temperature, wind speed and direction, and precipitation.

Several stations are operational year-round, even when extreme meteorological conditions limit fieldwork campaigns in winter. The oldest station is the one of Whapmagoostui-Kuujjuarapik (WK), which was opened to researchers in 1971, followed by the stations of the Boniface River (near the treeline) (1985), Bylot Island (1989), Ward Hunt Island (1998), Radisson (1999), and Lac à l’Eau-Claire (2005). Two major grants were secured in 2009 from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Arctic Research Infrastructure Fund (CFI-ARIF) that were used to acquire a small research vessel, the Louis-Edmond-Hamelin, and to modernize and extend the Qaujisarvik network. For example, the WK station was renovated and enlarged by adding a Community Science Center, which opened in 2012. The design and construction of the station were carried out in a spirit of openness with the local communities in order to facilitate the exchange of knowledge between the Cree, the Inuit, and the scientists working there. This station includes a conference room and an interactive permanent exhibition describing the human and natural history of the region. Thanks to the funding from CFI-ARIF, research stations were built at Umiujaq and Salluit and made available to scientists and their collaborators in 2011. In 2018, the Kangiqsualujjuaq station (also called Sukuijarvik, which means a ‘place for sciences’ in Inuktitut) was set up following another CFI funding. Two new stations in the High Arctic (at Mittimatalik and Qikiqtarjuaq) are under construction and will be managed by the CEN and Québec-Océan.

Partnership with northern communities in northeastern Canada

Thanks to the long-term commitment to maintain its research infrastructure in the North and the dedication of its members in pursuing various long-term northern research projects, the CEN is actively present in the North, both physically and intellectually. This presence is based on fruitful interactions and collaborations with the Inuit and Cree communities. As socio-economic and environmental realities became more complex in northern communities, the CEN was also able to establish increasingly close and formal relationships with communities in terms of northern research, training and, more recently, co-production of knowledge.

Establishment of the CEN in the North and subsequent development

Following its establishment in 1961, the CEN’s researchers were able to use government buildings in Fort Chimo (now the northern village of Kuujjuaq) along the Koksoak River in Ungava to carry out research in this area. These were the beginnings of the Qaujisarvik network of research stations. Later, the research station at Kuujjuaq was abandoned and the Ministry of Natural Resources transferred ownership of the government buildings located at Great Whale (now the northern village of the Cree Nation of Whapmagoostui and the Inuit village of Kuujjuarapik) at the mouth of the Great Whale River in Hudsonia by transferring title to Université Laval in the late 1960s. This research infrastructure has made it possible to carry out field campaigns in multiple disciplines of natural and applied sciences and to conduct studies related to economic and industrial development, while facilitating fieldwork by Canadian and international researchers.

The CEN was one of the first centre to organize science conferences in the North (Rencontre de nordistes Citation1967) and to initiate distance learning efforts through television broadcasts. After 1970, the first research stations were renovated and enlarged and others were built in the following decades to meet the growing needs of researchers in terms of space and infrastructure. Long-term agreements to occupy territories under Indigenous control were signed with the Inuit and Cree communities of Kuujjuarapik and Whapmagoostui, as well as with other Inuit communities. In response to the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) strategic plan set up in 2000 for research in the North and taking into account the CEN’s expertise in maintaining a constant physical presence in northern communities, this expansion has involved a formalization of bilateral relations with Indigenous communities. These included consultations and discussions with various administrative organizations, including the Kativik Regional Government, the Makivik Corporation, the Nunavik Landholding Corporation Association, the local landholding corporations, the local municipalities, the Cree Nation of Whapmagoostui, and Parks Canada. These discussions focused on the negotiation of rental agreements for lots under Indigenous control to accommodate the buildings, the identification of research areas of interest to the communities and the CEN’s members, the development of research, educational, and training objectives and the creation of structures to allow the co-management of research activities and facilities.

Main achievements, opportunities, challenges, and perspectives of the CEN

The sixth decade of the CEN (2011–2021)

Université Laval significantly increased its contribution to research in northern regions between 2001 and 2011 (Payette and Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). In fact, northern research became an essential part of the institution’s strategic research plan. Throughout the following decade (2012–2021), Université Laval increased its efforts to be a catalyst for northern and Arctic research while also promoting sustainable northern development. For example, Université Laval co-founded the Institut nordique du Québec (INQ) in partnership with the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), McGill University, and four Indigenous peoples (Inuit, Cree, Innu, and Naskapi). The CEN was among the original founders of the INQ and contributed at each stage of its development. The INQ brings together various research centres and Quebec-based institutions that work in northern studies and that represent fields as diverse as the natural sciences, social sciences, humanities and health studies.

Université Laval is also pursuing its Sentinel North strategy, funded by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, supporting innovative transdisciplinary research in northern environments. Several CEN members assume leadership roles in these projects. At the provincial level, the Quebec government’s publication of the Plan Nord in 2011 and the establishment of the Société du Plan Nord in 2015 as a commitment to socioeconomic development in the North yielded many research opportunities, for example on renewable energy, environmental protection, and biodiversity conservation. At the national and international levels, the CEN is actively involved in several research projects to understand the changes occurring in the North, such as the Terrestrial Multidisciplinary distributed Observatories for the Study of Arctic Connections (T-MOSAiC).

The CEN is a strategic research cluster (regroupement stratégique) funded by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et Technologies (FRQNT). Its governance structure evolved recently to account for changes in the northern research environment. Beginning in 2012, the leadership of the CEN was put in the hands of an administrative director (Najat Bhiry from 2012 to 2018 and Richard Fortier since 2018) as well as a scientific director (Warwick Vincent from 2012 to 2016 and Gilles Gauthier since 2016). Two assistant directors were appointed from partner universities (Joël Bêty from the Université du Québec à Rimouski since 2012 and Monique Bernier from INRS from 2012 to 2016, who was succeeded by Milla Rautio from the Université du Québec à Chicoutimi in 2016 and by Esther Lévesque from the Université du Québec à Trois Rivières in 2020).

The CEN’s fundamental research priorities include the study of northern geosystems and ecosystems. The many young researchers who have joined the CEN recently have helped expand research into innovative areas such as renewable energy and green technologies and the study of biomolecules and microbiomes. The researchers who began their careers at the CEN in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s still play a key role today, as part of the leadership of the CEN or as mentors for new researchers. Notwithstanding fluctuations in funding, the valuable work of the CEN led to increased scientific productivity, enhanced training of new researchers, and development of innovative research partnerships.

During the decade between 2011 and 2021, several large-scale projects were successfully launched, such as the ‘Arctic Development and Adaptation to Permafrost in Transition’ (ADAPT) project funded by NSERC, led by Warwick Vincent and involving many CEN members. Several noteworthy academic publications that were also of interest to the public, stakeholders, and decision makers were published during this period, such as Allard and Lemay (Citation2012), Berteaux et al. (Citation2014), and Payette (Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018). Excellence in research was also demonstrated by the publication of thousands of papers in high-impact research journals.

In 2018, the CEN received approximately $3 million in research and infrastructure funding from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) to build a research station at Kangiqsualujjuaq (Nunavik). The municipality and the Inuit community participated in the selection of the site and were consulted about the architecture and the management of the research station. In 2021, the CEN and Québec-Océan obtained additional funding from the CFI to build two new research stations in the Canadian High Arctic.

A scientific look at the rapidly changing North and resolutely turned towards the future

Nunavik (in northern Quebec), Nunatsiavut (in Labrador), and Nunavut (in northern Canada) are part of the Inuit Nunangat region of Canada, a vast Arctic territory that is changing rapidly in response to climate change. On the one hand, the rapid thaw of the cryosphere is transforming northern ecosystems and geosystems, and it affects the availability of ecosystem services for Inuit. On the other hand, the civil infrastructures of Inuit communities and access to the land for hunting, fishing, tourism, and industrial activities are also affected by the degradation of the cryosphere.

These Arctic territories are sentinels of environmental responses to climate changes. The research carried out therein presents major challenges in understanding their dynamics, but also in anticipating their future state and determining how Inuit communities can adapt to them. Access to Inuit Nunangat and the complex logistics of work in the North require many human and technical resources commanding high costs. Nevertheless, the CEN’s strategic research cluster, the structuring of northern research around common themes (), and the partnership with Inuit communities and stakeholders from the North make it possible to conduct productive northern research.

Table 1. CEN’s scientific programming: research axes and themes

Through the Qaujisarvik and SILA networks, the CEN is fulfilling its role as a facilitator of northern research in Inuit Nunangat. Research work conducted in the North is generally of very short duration and is carried out in the summer months, but the physical processes at play in the cryosphere, the dynamics of plant and animal populations, and biogeochemical cycles occur throughout the year. So far, the physical and biological processes occurring during the winter months have received little attention from researchers in Inuit Nunangat due to the challenge of working in an extremely cold environment with little to no light. In addition, the health restrictions of the last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic have prevented access to the North for researchers from the South. Even though this is an important part of the effort to protect vulnerable Inuit communities, this temporary inaccessibility has increased the challenges of carrying out research and hindered the long-term monitoring of environmental changes in the North.

Researchers must break away from the paradigm of difficult access to the North and find new ways to ensure long-term environmental monitoring in their absence. For example, innovative technologies that use new approaches in optics/photonics, microfluidics, genomics, remote sensing by satellites and drones could be developed and tested to adapt to the extreme conditions of the North. However, this paradigm shift should not only rely on technological developments. Indeed, researchers have the opportunity and the duty to include first-hand witnesses and privileged observers of environmental changes in the North; that is to say, the participation of the Inuit themselves, with their unique know-how and their knowledge of Inuit Nunangat. A citizen research initiative involving the community of Kangiqsualujjuaq lead by CEN members has shown that this is an interesting avenue for filling certain gaps in scientific knowledge, particularly in terms of environmental monitoring (Gérin-Lajoie et al. Citation2018).

CEN’s members are applying this new inclusive strategy of northern research to establish partnerships with Inuit communities, stakeholders, and decision makers in the North, to co-develop northern research, to train highly qualified personnel, to integrate the skills and services of observers well positioned in the North, and also to help in the mobilization and transfer of knowledge in northern science. By following this inclusive strategy, the CEN contributes to the achievement of several of the United Nation’s (UN) sustainable development goals. For instance, the study of emblematic species such as caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) can help identify the threats to these traditional food sources (UN objective 2; ). In addition, during school visits by CEN members, young Inuit are introduced to the collection of scientific information (objectives 4 and 10; ). Studies are carried out on the browning of surface water caused by global warming and the impact of permafrost degradation on groundwater, which are key sources of drinking water for Inuit communities, as well as on the water supply chain (from the source to the tap) (objective 6; ). Several CEN research stations are equipped with photovoltaic systems and new approaches are being developed to reduce the carbon footprint of buildings in the North (objectives 7 and 13; ). Indigenous partners are hired to take care to the CEN’s research stations and assist with fieldwork (objective 8; ). In partnership with Inuit communities, the CEN members are developing adaptation methods to predict the impacts of permafrost degradation on transportation infrastructure and buildings (objective 9; ). Adaptation methods are also developed to restore disturbed environments (objective 15; ). The training of highly qualified Indigenous personnel is also an aim that CEN members are helping to achieve through knowledge transfer and mobilization activities (objectives 4 and 10; ).

An eloquent sample of the diversity of research topics addressed by the CEN

The articles in this special issue are a representative sample of the co-production of knowledge on northern geosystems and ecosystems carried out at the CEN. Four of these articles are syntheses linked to one of the CEN’s three research axes (). The paper by Nozais et al. (Citation2021), which fits into Axis 1, focuses on the aquatic ecosystem of Great Whale River, which includes not only the river, but also its streams, lakes and mouth. Delwaide et al. (Citation2021) combine the results of 40 years of studies on black spruce at the treeline to present a 2233-year dendrochronological series, the longest to date in northeastern North America. This contribution relates to Axis 2, as does the paper by Royer et al. (Citation2021), which compiles snow survey data along a 4000 km south-north transect over a 20-year period. Finally, for the first time, the links between the progressive settlement of the region of Nain (Labrador) and forest dynamics over the last 500 years are presented in Roy et al. (Citation2021), which fits into Axis 3.

Five original paper are related to Axis 1 (Frederick et al. Citation2021; Moran et al. Citation2021; Lemay et al. Citation2021; Pellerin et al. Citation2021). Frederick et al. (Citation2021) answered questions from northern communities about the potential infection of migratory snow geese with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. Moran et al. (Citation2021) examined how the rabies virus, which is dangerous for Northerners, can persist despite the low density of its definitive host, i.e. the Arctic fox. Lemay et al. (Citation2021) determined the impact of shrubs, which are expanding in the north, on caribou food sources. Pellerin et al. (Citation2021) looked at the recent history of the invasion of broadleaved tree species in a temperate peatland, and Touati et al. (Citation2021) produced a freeze-thaw mapping of the sub-Arctic tundra using satellite images acquired in the microwave spectrum.

With respect to Axis 2, Narancic et al. (Citation2021) reconstructed the Holocene variations in the water quality of a large lake in the High Arctic, while Desjardins et al. (Citation2021) looked at the northernmost plant communities on Earth by establishing a baseline. Langlais et al. (Citation2021) identified the causes of temporal changes in vegetation in a permafrost bog.

Finally, an original paper relates to Axis 3. Using a numerical modeling approach, Perreault et al. (Citation2021) assessed the impacts of climate warming and changes in surface conditions on permafrost degradation.

In summary, 61 authors have contributed to this special issue; 40 of whom are members of the CEN. Notably, 8 of the 13 papers were first-authored by seven students and a postdoctoral fellow, whose research is ongoing or has just been completed. The 61 co-authors are associated with several universities in Quebec, other Canadian provinces, and outside Canada. This special issue is a concrete example of the principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion dear to the CEN, since more than 50% of the authors are women and many are associated with universities outside of Canada.

Conclusion

The CEN is a group of researchers working on northern themes. It also operates the Qaujisarvik and SILA networks along a latitudinal gradient of more than 3000 km, facilitating access to the North and the monitoring of environmental changes. During its 60 years of existence, the development of the CEN was made possible by its recognition as a ‘strategic research cluster’ by the FRQNT. The CEN has also benefited from the unwavering commitment shown by Université Laval and several other universities to meet the challenges of research in northern and remote regions. In addition to sharing infrastructure, equipment and data, CEN’s members have structured research around common axes and themes and they have established partnerships with Indigenous communities, various levels of government, and industrial stakeholders.

Through joint research projects with the Inuit and Cree communities who are directly affected by environmental changes in the North, CEN’s members will continue to pursue research activities that respond to societal issues and lead to sustainable development. This joint endeavor requires the creation of promising partnerships, the availability of funding for knowledge mobilization and transfer, and the training of highly qualified personnel, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. This training should enable Northerners to carry out field sampling, surveys, equipment maintenance, and activities in research facilities, while benefiting from the remote supervision of university researchers.

The founder of the CEN, Louis-Edmond Hamelin, proposed three objectives for the CEN: make the North, do the North and tell about the North. The CEN members have pursued the founder’s vision despite the logistical challenges and the uncertainties linked to research funding. Over the next decade, the CEN members will continue to do the North, engaging in joint research projects with their Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners. They will continue to tell about the North through their scientific contributions, while making the North.

References

- Allard M, Lemay M, editors. 2012. Nunavik and Nunatsiavut: from science to policy. An Integrated Regional Impact Study (IRIS) of climate change and modernization. Québec: : ArcticNet Inc. Quebec City, Canada, 303, Doi: https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1041.7284

- Berteaux D, Casajus N, De Blois S. 2014. Changements climatiques et biodiversité du Québec: vers un nouveau patrimoine naturel? Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. 202, D3950, ISBN 978-2-7605-3950-1.

- CEN. 2021. Québec: Centre d’études nordiques. [accessed 2021 June 14]. http://www.cen.ulaval.ca.

- Delwaide A, Asselin H, Arsenault D, Lavoie C, Payette S. 2021. A 2233-year tree-ring chronology of subarctic black spruce (Picea mariana): growth forms response to long-term climate change. Écoscience:1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1952014.

- Desjardins É, Lai S, Payette S, Vézina F, Tam A, Berteaux D. 2021. Vascular plant communities in the polar desert of Alert (Ellesmere Island, Canada): establishment of a baseline reference for the 21st century. Écoscience:1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907974.

- Frederick C, Girard C, Wong G, Lemire M, Langwieder A, Martin MC, Legagneux P. 2021. Communicating with Northerners on the absence of SARS-CoV-2 in migratory snow geese. Écoscience:1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1885803.

- Gérin-Lajoie J, Herrmann TM, MacMillan GA, Hébert-Houle É, Monfette M, Rowell JA, Anaviapik Soucie T, Snowball H, Townley E, Lévesque E, et al. 2018. IMALIRIJIIT: a community-based environmental monitoring program in the George River watershed, Nunavik, Canada. Écoscience. 25(4):381–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2018.1498226.

- Hamelin LE. 1960. Pour un centre nordique. Second mémoire présenté au Gouvernement de la Province de Québec au nom de l’Université Laval. Mémoires de la Société royale du Canada. 55:13–20.

- Hamelin LE. 1996. Écho des pays froids. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 484. ISBN 2-7637-7472-5.

- Hamelin LE. 2006. L’âme de la terre. Parcours d’un géographe. Québec: Éditions MultiMondes. 246 pages. ISBN 2-89544-087-5.

- Langlais K, Bhiry N, Lavoie M. 2021. Holocene dynamics of an inland palsa peatland at Wiyâshâkimî Lake (Nunavik, Canada). Écoscience:1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907975.

- Lemay E, Côté SD, Tremblay J-P. 2021. How will snow retention and shading from Arctic shrub expansion affect caribou food resources? Écoscience:1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1917859.

- Moran EJ, Lecomte N, Leighton P, Hurford A. 2021. Understanding rabies persistence in low-density fox populations. Écoscience:1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1916215.

- Narancic B, Saulnier-Talbot É, St-Onge G, Pienitz R. 2021. Diatom sedimentary assemblages and Holocene pH reconstruction from the Canadian Arctic Archipelago’s largest lake. Écoscience:1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1926642.

- Nozais N, Vincent WF, Belzile C, Gosselin M, Blais MA, Canário J, Archambault P. 2021. The Great Whale River ecosystem: ecology of a subarctic river and its receiving waters in coastal Hudson Bay, Canada. Écoscience:1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1926137.

- Payette S, editor. 2013. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 1. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 553.

- Payette S, editor. 2015. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 2. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 711

- Payette S, editor. 2018. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 3. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 711.

- Payette S. 2020. Louis-Edmond Hamelin (1923–2020): un géant de la géographie. Le Naturaliste canadien. 144(2):3–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/1071604ar.

- Payette S, Saulnier-Talbot E. 2011. Un demi-siècle de recherche au Centre d’études nordiques: un défi de tous les instants. Écoscience. 18(3):171–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.2980/18-3-3492.

- Pellerin S, Lavoie M, Talbot J. 2021. Rapid broadleave encroachment in a temperate bog induces species richness increase and compositional turnover. Écoscience:1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907976.

- Perreault J, Fortier R, Molson JW. 2021. Numerical modelling of permafrost dynamics under climate change and evolving ground surface conditions: application to an instrumented permafrost mound at Umiujaq, Nunavik (Québec), Canada. Écoscience:1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1949819.

- Rencontre de nordistes. 1967. Problèmes nordiques des façades de la baie de James: recueil de documents colligés par Hugues Morrissette et Louis-Edmond Hamelin à la suite d’une rencontre de nordistes à Moosonee, Ontario, en février 1967. Québec: Université Laval.

- Roy N, Woollett J, Bhiry N, Lemus Lauzon I, Delwaide A, Marguerie D. 2021. Anthropogenic and climate impacts on subarctic orests in the Nain region, Nunatsiavut: dendroecological and historical approaches. Écoscience:1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1932294.

- Royer A, Domine F, Roy AR, Langlois A, Marchand N, Davesne G. 2021. New northern snowpack classification linked to vegetation cover on a latitudinal mega-transect across northeastern Canada. Écoscience:1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1898775.

- Touati C, Ratsimbazafy T, Poulin J, Bernier M, Homayouni S, Ludwig R. 2021. Landscape freeze/thaw mapping from active and passive microwave Earth observations over the Tursujuq National Park, Quebec, Canada. Écoscience:1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1969790.

- Vincent WF, Côté SD, Bernier M. 2011. From boreal forest to high Arctic desert: a theme issue commemorating 50 years of research by the Centre for Northern Studies (CEN) in Eastern Canada. Écoscience. 18(3):iii–iv. doi:https://doi.org/10.2980/18-3-3497.

Le Centre d’études nordiques (CEN): Défis et perspectives de la recherche sur la nordicité en partenariat avec les communautés autochtones

Najat Bhirya, Monique Bernierb, Nicolas Lecomtec, Richard Fortierd and James Woollette

aCentre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Département de géographie, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; bCentre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Centre Eau, Terre, Environnement, Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Québec, Québec, Canada; cCentre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Canada Research Chair in Polar and Boreal Ecology, Department de Biologie, Université de Moncton, Moncton, Nouveau Brunswick, Canada; dCentre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Département de géologie et génie géologique, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada; eCentre d’études nordiques (CEN) et Département des sciences historiques, Université Laval, Québec, Québec, Canada

Suite à de longues démarches entreprises par Hamelin (Citation1960), le conseil de l’Université Laval fonde le Centre d’études nordiques (CEN) en avril 1961. Le CEN est ensuite reconnu officiellement le 2 août 1961 par un arrêté en conseil de la Chambre du Conseil exécutif du gouvernement du Québec qui confirme la toute première subvention du CEN pour la réalisation de travaux de recherche dans le Nord du Québec. Au début des années 1960, le développement du Nord québécois visait l’exploitation des ressources naturelles, notamment l’hydro-électricité (Payette et Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Le CEN fut créé pour assurer une présence de scientifiques francophones dans le monde circumpolaire, plus particulièrement dans le Nord du Québec qui demeurait jusque-là plus méconnu que les autres régions nordiques, notamment de l’Europe du Nord et de l’Alaska. En 1961, le CEN poursuivait deux objectifs principaux: la réalisation d’une recherche « générale » sur plusieurs aspects des régions du Nord et la diffusion des résultats de recherche par l’intermédiaire d’un centre de publication et de centres d’information et de documentation (Payette et Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Louis-Edmond Hamelin avait établi trois objectifs pour le CEN (Hamelin Citation1960): (1) « Faire du Nord », c’est-à-dire réaliser des productions de toute nature du Nord, qu’elles soient intellectuelles, matérielles ou visibles dans le paysage; (2) « Faire le Nord », c’est-à-dire contribuer à bâtir un système optimal de vie pour chacun des peuples qui habitent le Nord et (3) « Faire le dit du Nord », soit matérialiser le Nord dans les programmes d’éducation, les communications, les informations, les publications et les circulations numériques.

Louis-Edmond Hamelin a créé un centre de recherche multidisciplinaire inclusif dans les domaines des sciences naturelles et des sciences humaines et sociales. Il a dirigé les destinées du CEN durant les dix premières années de son existence. Au tournant des années 1970, l’évolution du contexte du financement de la recherche a forcé le CEN à concentrer ses efforts uniquement dans le domaine des sciences naturelles (Payette et Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Parmi les aspects de sa riche personnalité et de sa grande sensibilité, Louis-Edmond Hamelin était un ardent défenseur des droits des peuples autochtones (Payette Citation2020). Tant dans ses écrits que dans ses allocutions et lors de réunions, il discutait de la question du respect des cultures, des mœurs et de l’émancipation des populations autochtones (Payette Citation2020). Pour en connaître plus sur ses réalisations nordiques et la personnalité de cet homme qui a défendu le Nord toute sa vie, vous pouvez consulter ses autobiographies (Hamelin Citation1996, Citation2006). Afin de souligner son rôle de visionnaire, le CEN a baptisé en son honneur lors du 50e anniversaire du CEN (Vincent et al. Citation2011) un bateau utilisé pour appuyer la recherche côtière, fluviale et lacustre (). Cette plateforme maritime mobile fait partie du réseau Qaujisarvik de stations de recherche du CEN.

Figure 1. Le professeur Louis-Edmond Hamelin lors de l’inauguration en avril 2011 du bateau scientifique du CEN. Ce bateau a été nommé le Louis-Edmond Hamelin en l’honneur du fondateur du CEN

Aujourd’hui, la mission du CEN est de relever les défis de la recherche sur la nordicité en partenariat avec les communautés autochtones en contribuant au développement durable des régions nordiques par l’amélioration de la compréhension des environnements froids et de la capacité à prédire les changements qui les affectent (CEN Citation2021). La recherche dans les régions arctiques et subarctiques implique des difficultés d’accès au territoire dues à l’éloignement, des enjeux de sécurité et des coûts logistiques élevés pour les travaux de terrain en régions éloignées, et la prise en compte des réalités autochtones. C’est pour répondre à ces défis et aux besoins des communautés nordiques et du gouvernement du Québec que le CEN a été créé il y a 60 ans. Ces défis et ces enjeux sont toujours d’actualité. Au fil des décennies, le CEN a développé un savoir-faire unique, des relations de confiance avec les communautés autochtones et des collaborations pancanadiennes et internationales. Il est ainsi en très bonne position afin de répondre aux défis du XXIe siècle. En effet, la compréhension des enjeux qui affectent de plus en plus les milieux nordiques tel que les impacts des changements climatiques et le développement socio-économique accéléré commande des approches multidisciplinaires en partenariat avec les communautés autochtones. Le CEN rassemble des chercheurs et des chercheuses d’une douzaine d’universités québécoises et d’autres provinces canadiennes. Leurs champs d’expertise sont diversifiés dont notamment la géomorphologie périglaciaire, la limnologie, l’écologie végétale et animale, la microbiologie, la paléoécologie, la géologie, la modélisation numérique, l’hydrologie, la bioarchéologie, l’ingénierie, ainsi que la télédétection. Avec près de 300 membres (80 chercheurs et chercheuses, 186 étudiantes et étudiants aux cycles supérieurs, 18 stagiaires au niveau postdoctoral et 10 professionnels et professionnelles de recherche), le CEN est un des principaux moteurs du positionnement du Québec comme pôle d’excellence en recherche nordique aux niveaux national et international.

Pour illustrer le rôle de leader en recherche nordique du CEN, les réseaux Qaujisarvik et SILA dans le Nord () ainsi que les nombreux partenariats avec les communautés nordiques du nord-est du Canada sont présentés dans les deux prochaines sections. En plus des cinq premières décennies de son évolution et de ses réalisations tel que présenté par Payette et Saulnier-Talbot (Citation2011), les réalisations récentes du CEN et les défis relevés lors de la dernière décennie sont décrits à la troisième section laquelle comprend une sous-section consacrée aux perspectives en recherche nordique et aux défis pour la prochaine décennie. En guise de conclusion, les articles de ce numéro spécial soulignant le 60e anniversaire du CEN sont présentés, représentant un échantillon de la diversité des thématiques de recherche du CEN.

Figure 2. Localisations des stations de recherche du réseau Qaujisarvik et des stations de suivi environnemental du réseau SILA du CEN le long d’un gradient latitudinal de la forêt boréale au désert polaire. Des stations SILA se trouvent à toutes les stations du réseau Qaujisarvik. Photographies: D. Sarrazin

Présence physique du CEN dans le Nord

En plus de ce regroupement stratégique de scientifiques à expertises multiples et de partenaires communautaires, le CEN a mis en place un réseau unique de stations de recherche ainsi qu’un réseau de suivi environnemental le long d’un gradient sud-nord, de la forêt boréale à l’Arctique, sur près de 26 degrés de latitude (). Ces infrastructures de recherche sont utilisées pour différents projets de recherche au sein de huit zones bioclimatiques du Québec et de l’Est de l’Arctique canadien.

Le premier réseau établi et géré par le CEN est appelé Qaujisarvik qui signifie « lieu d’étude » en Inuktitut. Ce réseau est constitué de dix stations de recherche qui s’étale de la Jamésie au Québec jusqu’à l’extrême nord canadien sur l’Île d’Ellesmere, donc sur près de 20 degrés de latitude (). Ces stations comprennent toutes les infrastructures requises pour la recherche nordique (laboratoires, salles de rencontre, lieux d’hébergement, cuisine, dortoir, moyens de transport, matériel de terrain, etc.) et permettent non seulement l’échange avec les membres des communautés dans lesquelles elles sont implantées, mais aussi le soutien logistique et scientifique aux équipes de recherche du CEN et à leurs partenaires. Les stations du réseau Qaujisarvik servent à étudier l’état des écosystèmes et des géosystèmes afin de prévoir leurs réponses aux changements climatiques via, par exemple, l’étude de la dynamique du pergélisol, d’espèces végétales ou animales clés, des paysages naturels et culturels, etc. Les projets réalisés grâce au réseau Qaujisarvik répondent aux besoins des communautés locales (co-construction de projets, consultation, cogestion des stations, etc.).

Le second réseau regroupe actuellement plus d’une centaine de stations de suivi environnemental et climatologique automatisées (). Il s’agit du réseau SILA nommé d’après un terme Inuktitut polysémique dont une des significations réfère au climat. Ce réseau d’observatoires permanents a été mis en place pour caractériser, quantifier et évaluer les changements climatiques et environnementaux nordiques. Les sites du réseau SILA sont équipées de multiples sondes qui enregistrent plusieurs paramètres, dont la température de l’air, la vitesse et la direction des vents et les précipitations.

Plusieurs stations de recherche sont fonctionnelles à l’année, même lorsque les conditions hivernales extrêmes limitent les campagnes de terrain. La plus ancienne station est celle de Whapmagoostui-Kuujjuarapik (WK), qui fut ouverte aux chercheurs en 1971, suivie par les stations de la Rivière Boniface près de la limite des arbres (1985), de l’île Bylot (1989), de l’île Ward Hunt (1998), de Radisson (1999) et du Lac à l’Eau-Claire (2005). L’obtention de deux subventions majeures en 2009 de la Fondation canadienne pour l’innovation et du Fonds d’infrastructure de recherche dans l’Arctique (FCI-FIRA) a permis d’acheter un navire de recherche, le Louis-Edmond-Hamelin, et de moderniser et étendre le réseau Qaujisarvik. Par exemple, la station de WK a été rénovée et agrandie en y ajoutant un Centre scientifique communautaire ouvert en 2012. Sa conception et son édification ont été placées sous le signe de l’ouverture sur les communautés locales afin de faciliter l’échange de savoirs entre les Cris, les Inuit et les scientifiques sur place. Cette station offre une salle de conférence et une exposition permanente interactive sur l’histoire humaine et naturelle de la région. C’est aussi grâce à ce financement que les stations d’Umiujaq et de Salluit ont été construites en 2011. Plus tard, en 2018, la station de Kangiqsualujjuaq (aussi appelée Sukuijarvik qui signifie « place des sciences » en Inuktitut) a été mise en place grâce à un financement du programme FCI innovation. Deux nouvelles stations dans le Haut-Arctique à Mittimatalik et Qikiqtarjuaq sont en voie de construction qui seront gérées par le CEN et le regroupement Québec-Océan.

Partenariat avec les communautés nordiques du nord-est du Canada

Grâce au maintien à long terme de ses infrastructures de recherche dans le Nord et au dévouement de ses membres en poursuivant différents travaux de recherche nordique de longue haleine, le CEN est présent dans le Nord tant sur les plans physique qu’intellectuel. Cette présence est fondée sur des interactions et des collaborations fructueuses avec les communautés inuit et cries. Au fur et à mesure que les réalités socio-économiques et environnementales se complexifiaient dans les collectivités du Nord, le CEN a su établir des relations de plus en plus étroites et formelles avec les communautés au niveau de ses infrastructures de recherche nordique, de formation et, plus récemment, de coproduction des connaissances.

Établissement du CEN dans le Nord et développement subséquent

Suite à son établissement en 1961, les chercheurs du CEN ont pu disposer de bâtiments gouvernementaux à Fort Chimo (maintenant le village nordique de Kuujjuaq) le long de la rivière Koksoak en Ungava afin de réaliser des travaux de recherche dans ce secteur. Il s’agit des débuts du réseau Qaujisarvik de stations de recherche. Plus tard, la station de recherche à Kuujjuaq fut abandonnée et, vers la fin des années 1960, le ministère des Ressources naturelles a transféré à l’Université Laval les titres de propriété des bâtiments gouvernementaux situés à Poste-de-la-Baleine (maintenant le village nordique de la Nation crie de Whapmagoostui et le village inuit de Kuujjuarapik) à l’embouchure de la Grande-Rivière-de-la-Baleine en Hudsonie. Ces infrastructures de recherche ont permis, en plus de la réalisation de campagnes de terrain dans de multiples disciplines des sciences naturelles et appliquées, des études sur le développement économique et industriel, tout en soutenant les travaux de terrain de chercheurs et chercheuses du Canada et d’ailleurs.

Le CEN a été l’un des premiers centres à organiser des conférences scientifiques dans le Nord (Rencontre de nordistes Citation1967) et à initier des efforts d’apprentissage à distance par le biais d’émissions de télévision. Après 1970, pour répondre aux besoins croissants des chercheurs et des chercheuses en espace et en infrastructures, les premières stations de recherche ont été rénovées et agrandies et d’autres ont été construites lors des décennies suivantes. Pour ce faire, des ententes à long terme pour l’occupation du territoire sous contrôle autochtone ont été conclues avec la Nation crie de Whapmagoostui ainsi qu’avec d’autres communautés inuit. En réponse au plan stratégique du Conseil de recherches en sciences naturelles et en génie du Canada (CRSNG) mis en place en 2000 pour la recherche dans le Nord et en tenant compte de l’expertise du CEN en ce qui a trait au maintien d’une présence physique constante dans les communautés nordiques, l’expansion du réseau Qaujisarvik a impliqué une formalisation des relations bilatérales avec les communautés autochtones où les stations ont été emplantées. Il s’agissait notamment de consultations et de discussions avec diverses organisations administratives, dont l’Administration régionale Kativik, la Société Makivik, l’Association des sociétés foncières du Nunavik, les corporations foncières locales et les municipalités des villages nordiques inuit, la Nation crie de Whapmagoostui et Parcs Canada. Ces échanges ont porté sur la négociation d’ententes de location des lots sous contrôle autochtone pour accueillir les bâtiments, sur l’identification des domaines de recherche qui intéressaient à la fois les communautés et les membres du CEN, sur le développement d’infrastructures de recherche, d’objectifs éducatifs, de formation et sur des structures qui permettent la cogestion des activités et des installations de recherche.

Principales réalisations, opportunités, défis et perspectives du CEN

Sixième décennie du CEN (2011–2021)

La recherche nordique durant la décennie 2001–2011 a pris davantage d’ampleur au sein de l’Université Laval, faisant partie intégrante du plan stratégique institutionnel de développement de la recherche (Payette et Saulnier-Talbot Citation2011). Lors de la décennie suivante (2011–2021), l’Université Laval s’est engagée à mieux catalyser la recherche nordique et arctique pour le développement durable du Nord. À titre d’exemple, elle a cofondé l’Institut nordique du Québec (INQ) avec l’Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS), l’Université McGill et quatre peuples autochtones (Inuit, Cri, Innu, Naskapi). Le CEN était parmi les principaux initiateurs de l’INQ et il a contribué à chacune des étapes de son développement. L’INQ fédère les regroupements et les centres québécois en recherche nordique dans les domaines des sciences naturelles, sociales et humaines et de la santé.

Avec sa stratégie Sentinelle Nord financée par Apogée Canada, l’Université Laval a obtenu un financement majeur afin de réaliser des projets de recherche transdisciplinaires innovants sur les environnements nordiques. Plusieurs membres du CEN assument un rôle de leadership dans ces projets. Au niveau provincial, la publication du Plan Nord en 2011 par le gouvernement québécois et la création de la Société du Plan Nord en 2015 dont la mission est le développement socioéconomique du Nord ont créé des opportunités de recherche en lien, entre autres, avec les énergies renouvelables, la protection de l’environnement et la conservation de la biodiversité. Sur les plans national et international, le CEN est activement impliqué dans plusieurs projets de recherche clés pour comprendre le Nord en mutation, tel le projet international Terrestrial Multidisciplinary distributed Observatories for the Study of Arctic Connections (T-MOSAiC).

En tant que regroupement stratégique financé par le Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et Technologies (FRQNT), le CEN est au cœur de la mouvance axée sur la recherche nordique et, pour y faire face, la structure de gouvernance du CEN a été modifiée. Ainsi, depuis 2012, la gestion du CEN est assurée par une direction administrative (Najat Bhiry de 2012 à 2018, puis Richard Fortier à partir de 2018) et par une direction scientifique (Warwick Vincent de 2012 à 2016, puis Gilles Gauthier depuis 2016) lesquelles sont appuyées par des directions adjointes qui proviennent des universités partenaires (Joël Bêty de l’Université du Québec à Rimouski depuis 2012 et Monique Bernier de l’INRS de 2012 à 2016, ayant été remplacée par Milla Rautio de l’Université du Québec à Chicoutimi en 2016 et par Esther Lévesque de l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières en 2020).

En termes de programmation, l’étude des géosystèmes et des écosystèmes nordiques constitue la pierre d’assise de la recherche sur la nordicité au CEN. Les nombreux jeunes chercheurs et chercheuses qui se sont joints récemment au CEN ont contribué à l’émergence de thèmes novateurs tels que le développement des énergies renouvelables et de technologies vertes et l’étude des biomolécules et des microbiomes nordiques. Les chercheurs et les chercheuses qui ont débuté leur carrière au CEN dans les années 1970, 1980 et 1990 et qui sont toujours actifs jouent un rôle clé non seulement à la direction du CEN, mais aussi comme mentors auprès des nouveaux membres. Par conséquent, la productivité scientifique, la formation de la relève, l’innovation et les partenariats n’ont cessé d’augmenter même si le financement de la recherche est hautement compétitif.

La décennie 2011–2021 a vu l’accomplissement de grands projets tel le projet « Arctique en Développement et Adaptation au Pergélisol en Transition » (ADAPT) financé dans le cadre des initiatives Frontières du CRSNG, dirigé par Warwick Vincent et auquel plusieurs membres du CEN ont contribué. Parmi les publications majeures des membres du CEN qui sont destinées aux scientifiques, aux décideurs et aux publics intéressés, figurent Allard et Lemay (Citation2012), Berteaux et al. (Citation2014) et Payette (Citation2013, Citation2015, Citation2018). L’excellence est aussi illustrée par la publication de milliers d’articles scientifiques dans des revues scientifiques de haut niveau.

En 2018, le CEN a obtenu une subvention d’infrastructures de recherche de près de trois millions de dollars de la Fondation canadienne pour l’innovation (FCI) pour la construction d’une station de recherche à Kangiqsualujjuaq (Nunavik). L’emplacement, l’architecture et le mode de gestion ont été établis en concertation avec la municipalité et la communauté inuit. En 2021, le CEN et Québec-Océan ont obtenu un autre financement de la FCI pour la mise en place de deux nouvelles stations de recherche dans le Haut-Arctique canadien.

Un regard scientifique sur le Nord en pleine mutation et résolument tourné vers le futur

Le Nunavik au nord du Québec, le Nunatsiavut au Labrador et le Nunavut au nord du Canada font partie de la terre des Inuit au Canada appelée l’Inuit Nunangat, un immense territoire arctique en mutation en réponse aux changements climatiques. D’une part, le dégel rapide de la cryosphère transforme les écosystèmes et les géosystèmes nordiques, et il affecte la disponibilité des services écosystémiques pour les Inuit. D’autre part, les infrastructures civiles des communautés inuit et l’accès au territoire pour la chasse, la pêche, le tourisme et les activités industrielles sont aussi affectés par la dégradation de la cryosphère.

Ces territoires arctiques sont des sentinelles de la réponse environnementale aux changements climatiques. Les travaux de recherche qui y sont réalisés comportent des défis majeurs pour comprendre leur dynamique, anticiper leur état futur et déterminer comment les communautés inuit pourront s’y adapter. L’accès à l’Inuit Nunangat et la logistique complexe des travaux dans le Nord commandent des ressources humaines et techniques à des coûts élevés. Le regroupement stratégique de chercheurs et de chercheuses au sein du CEN, la structuration de la recherche nordique autour de thématiques communes, et le partenariat avec les communautés inuit et les intervenants du Nord facilitent la recherche nordique.

Grâce aux deux réseaux Qaujisarvik et SILA dans le Nord, le CEN assume son rôle de facilitateur de la recherche nordique dans l’Inuit Nunangat. Les séjours de recherche dans le Nord sont généralement très courts et se concentrent en été, alors que les processus physiques en jeu dans la cryosphère, la dynamique des populations végétales et animales, et les cycles biogéochimiques surviennent durant toute l’année. Jusqu’à présent, les processus physiques et biologiques durant l’hiver ont reçu peu d’attention des chercheurs et des chercheuses dans l’Inuit Nunangat à cause des difficultés liées au travail dans un environnement très froid avec peu de lumière. Par ailleurs, les restrictions sanitaires de la pandémie de COVID-19 ont empêché l’accès au Nord aux chercheurs et chercheuses du Sud. Même s’il s’agissait d’une partie importante des efforts pour protéger les communautés inuites vulnérables, cette inaccessibilité temporaire a exacerbé les défis de la recherche et du suivi à long terme des changements environnementaux dans le Nord.

Les chercheurs et les chercheuses doivent sortir du paradigme de l’accès difficile au Nord et trouver de nouveaux moyens pour assurer la surveillance environnementale à long terme en leur absence. Par exemple, des technologies innovantes qui font appel à des approches en optique/photonique, microfluidique, génomique, télédétection par satellites et drones pourraient être développées et testées pour affronter les conditions extrêmes du Nord. Mais ce changement de paradigme ne doit pas s’arrêter à ces seuls développements technologiques. En effet, les chercheurs et les chercheuses ont l’opportunité et le devoir de faire appel aux témoins et observateurs privilégiés des changements environnementaux dans le Nord, c’est-à-dire aux Inuit eux-mêmes avec leur savoir-faire et leur savoir-être unique de l’Inuit Nunangat. Une initiative de recherche citoyenne menée par des membres du CEN et impliquant la communauté de Kangiqsualujjuaq a d’ailleurs montré qu’il s’agit d’une avenue intéressante pour combler certaines lacunes dans les connaissances scientifiques, notamment en termes de suivi environnemental (Gérin-Lajoie et al. Citation2018).

Les chercheurs et les chercheuses du CEN appliquent ce nouveau modèle inclusif de la recherche nordique pour établir des partenariats avec les communautés inuit, les acteurs et les décideurs du Nord, co-construire la recherche nordique, former du personnel hautement qualifié, faire appel aux compétences et services d’observateurs privilégiés dans le Nord, et mobiliser et transférer les connaissances. En s’appropriant ce modèle, le CEN contribue à l’atteinte de plusieurs objectifs de développement durable de l’Organisation des Nations Unies (ONU). Par exemple, l’étude d’espèces emblématiques comme le caribou (Rangifer tarandus) et l’omble chevalier (Salvelinus alpinus) permet de mieux cerner les menaces qui pèsent sur ces sources de nourriture traditionnelle (objectif 2 de l’ONU). Des interventions des membres du CEN dans les écoles du Nord initient les jeunes inuit à la collecte d’information scientifique (objectifs 4 et 10). Des études sont réalisées sur le brunissement des eaux de surface causé par le réchauffement climatique et les impacts de la dégradation du pergélisol sur les eaux souterraines qui sont des sources d’eau potable pour les communautés inuit, ainsi que sur la chaîne d’approvisionnement en eau, de la source jusqu’au robinet (objectif 6). Plusieurs stations de recherche du CEN sont équipées de systèmes photovoltaïques et de nouvelles approches sont développées pour réduire l’empreinte carbone des bâtiments dans le Nord (objectifs 7 et 13). Des partenaires autochtones sont engagés pour gérer les stations de recherche du CEN et assister aux travaux de terrain (objectif 8). Les membres du CEN développent des méthodes d’adaptation aux impacts du dégel du pergélisol sur les infrastructures de transport et les bâtiments (objectif 9) et des approches de restauration des environnements perturbés (objectif 15) ainsi que des partenariats avec les communautés inuit pour le transfert et la mobilisation des connaissances. La formation de personnel hautement qualifié autochtone est aussi un enjeu que les membres du CEN contribuent à relever (objectifs 4 et 10).

Un échantillon éloquent de la diversité des sujets de recherche abordés au CEN

Les articles publiés dans ce numéro spécial sont un échantillon représentatif de la co-production du savoir sur les géosystèmes et les écosystèmes nordiques réalisée au CEN. Quatre de ces articles sont des synthèses en lien avec un des trois axes de recherche du CEN (). L’article de Nozais et al. (Citation2021), qui s’insère dans l’Axe 1, porte sur l’écosystème aquatique de la Grande Rivière de la Baleine qui inclut non seulement la rivière, mais aussi ses ruisseaux, ses lacs et son embouchure. Delwaide et al. (Citation2021) combinent les résultats de 40 ans de travaux réalisés sur l’épinette noire à la limite des arbres pour présenter une série dendrochronologique de 2233 ans, la plus longue à ce jour dans le nord-est de l’Amérique du Nord. Cette contribution est en lien avec l’Axe 2, tout comme l’article de Royer et al. (Citation2021), qui compile les données d’étude de la neige le long d’un transect sud-nord de 4000 km sur une période de 20 ans. Finalement, pour la première fois, les liens entre le peuplement progressif de la région de Nain (Labrador) et la dynamique de la forêt durant les derniers 500 ans sont présentés dans l’article de Roy et al. (Citation2021) lequel s’insère dans l’axe 3.

Tableau 1. Programmation scientifique du CEN: Axes et thèmes de recherche

Cinq articles de projets originaux sont en lien avec l’Axe 1(Frederick et al. Citation2021; Moran et al. Citation2021; Lemay et al. Citation2021; Pellerin et al. Citation2021). Frederick et al. (Citation2021) ont répondu aux questionnements des communautés nordiques à propos de l’infection potentielle des oies des neiges migratrices par le coronavirus SRAS-CoV-2. Moran et al. (Citation2021) ont examiné comment le virus de la rage, dangereux pour les résidents du Nord, peut persister malgré la faible densité de l’hôte définitif, i.e. le renard arctique. Lemay et al. (Citation2021) ont déterminé l’effet des arbustes, qui sont en expansion dans le nord, sur les sources de nourriture du caribou. Pellerin et al. (Citation2021) se sont intéressés à l’histoire récente de l’invasion d’espèces arborescentes feuillues dans une tourbière tempérée et Touati et al. (Citation2021) ont réalisé une cartographie du gel-dégel de la toundra subarctique en utilisant des images satellitaires acquises dans le spectre des microondes.

En adéquation avec l’Axe 2, Narancic et al. (Citation2021) ont reconstitué les variations holocènes de la qualité de l’eau d’un grand lac du Haut-Arctique alors que Desjardins et al. (Citation2021) se sont intéressés aux communautés végétales les plus septentrionales sur Terre en établissant une base de référence. Langlais et al. (Citation2021) ont identifié les causes des changements temporels de la végétation d’une tourbière à pergélisol.

Finalement, un article original est en lien avec l’Axe 3. En utilisant une approche de modélisation numérique, Perreault et al. (Citation2021) ont évalué les impacts du réchauffement climatique et des changements des conditions de surface sur la dégradation du pergélisol.

En résumé, 61 auteurs et auteures ont contribué à ce numéro spécial, dont 40 sont membres du CEN. Fait notable, 8 des 13 articles ont comme premier auteur un étudiant, six étudiantes et une stagiaire postdoctorale dont la recherche est en cours ou vient d’être terminée. Les 61 co-auteurs proviennent de plusieurs universités québécoises, d’autres provinces canadiennes, et hors Canada. Ce numéro spécial est un exemple concret des principes d’équité, diversité et inclusion chers au CEN puisque la moitié des auteurs sont des femmes et que plusieurs proviennent de l’international.

Conclusion

Le CEN est un regroupement de scientifiques qui œuvrent sur des thématiques nordiques. Il opère les réseaux Qaujisarvik de stations de recherche et SILA de stations de suivi environnemental le long d’un gradient latitudinal de plus de 3000 km qui facilitent l’accès au Nord et le suivi des changements environnementaux. Au cours de ses 60 ans d’existence, le développement du CEN a été possible grâce à sa reconnaissance comme regroupement stratégique par le FRQNT ainsi que l’engagement indéfectible de l’Université Laval et de plusieurs universités québécoises dans la recherche nordique afin de relever les défis de la recherche en régions nordiques et peu accessibles. Les membres du CEN ont initié le partage des infrastructures, des équipements et des données, ils ont structuré la recherche autour d’axes et de thématiques communs, et établi des partenariats avec les communautés autochtones et les intervenants gouvernementaux et industriels.

Les membres du CEN continueront à mener des projets de recherche co-construits avec les communautés autochtones affectées par les changements environnementaux, afin de répondre aux enjeux sociétaux et permettre le développement durable du Nord. Cette co-construction demande la création de partenariats porteurs, la disponibilité de moyens financiers pour la mobilisation et le transfert des connaissances et la formation de personnel hautement qualifié autochtone et allochtone. Cette formation devrait permettre aux gens du Nord de réaliser des échantillonnages sur le terrain, des enquêtes, de l’entretien des équipements scientifiques et des activités dans les laboratoires des stations tout en bénéficiant de l’encadrement à distance des chercheurs et chercheuses universitaires.

Le fondateur du CEN, Louis-Edmond Hamelin, avait proposé trois objectifs pour le CEN: faire du Nord, faire le Nord et faire le dit du Nord. Les membres du CEN ont poursuivi la vision du fondateur malgré les défis logistiques et les aléas du financement de la recherche. Dans la prochaine décennie, les membres du CEN contribueront à faire le Nord en co-construisant des projets de recherche avec leurs partenaires autochtones et allochtones. De plus, ils continueront à faire le dit du Nord par leur production scientifique, tout en faisant du Nord.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Editor-in-chief, Hugo Asselin, for his comments and suggestions. of this Editorial and the cover image of this special issue were edited with the help of Erin Lecomte. This work is dedicated to the memory of Louis-Edmond Hamelin.

Remerciements

Les auteurs remercient chaleureusement le rédacteur en chef, Hugo Asselin, pour ses commentaires et ses suggestions pertinentes. La de cet éditorial de cet éditorial et l'image de la couverture de ce numéro spécial ont été éditées avec l'aide d'Erin Lecomte. Ce travail est dédié à la mémoire de Louis-Edmond Hamelin.

Références

- Allard M, Lemay M, editors. 2012. Nunavik and Nunatsiavut: from science to policy. An Integrated Regional Impact Study (IRIS) of climate change and modernization. Québec: : ArcticNet Inc. Quebec City, Canada, 303, Doi: https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1041.7284

- Berteaux D, Casajus N, De Blois S. 2014. Changements climatiques et biodiversité du Québec: vers un nouveau patrimoine naturel? Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. 202, D3950, ISBN 978-2-7605-3950-1.

- CEN. 2021. Québec: Centre d’études nordiques. [accessed 2021 June 14]. http://www.cen.ulaval.ca.

- Delwaide A, Asselin H, Arsenault D, Lavoie C, Payette S. 2021. A 2233-year tree-ring chronology of subarctic black spruce (Picea mariana): growth forms response to long-term climate change. Écoscience:1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1952014.

- Desjardins É, Lai S, Payette S, Vézina F, Tam A, Berteaux D. 2021. Vascular plant communities in the polar desert of Alert (Ellesmere Island, Canada): establishment of a baseline reference for the 21st century. Écoscience:1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907974.

- Frederick C, Girard C, Wong G, Lemire M, Langwieder A, Martin MC, Legagneux P. 2021. Communicating with Northerners on the absence of SARS-CoV-2 in migratory snow geese. Écoscience:1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1885803.

- Gérin-Lajoie J, Herrmann TM, MacMillan GA, Hébert-Houle É, Monfette M, Rowell JA, Anaviapik Soucie T, Snowball H, Townley E, Lévesque E, et al. 2018. IMALIRIJIIT: a community-based environmental monitoring program in the George River watershed, Nunavik, Canada. Écoscience. 25(4):381–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2018.1498226.

- Hamelin LE. 1960. Pour un centre nordique. Second mémoire présenté au Gouvernement de la Province de Québec au nom de l’Université Laval. Mémoires de la Société royale du Canada. 55:13–20.

- Hamelin LE. 1996. Écho des pays froids. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 484. ISBN 2-7637-7472-5.

- Hamelin LE. 2006. L’âme de la terre. Parcours d’un géographe. Québec: Éditions MultiMondes. 246 pages. ISBN 2-89544-087-5.

- Langlais K, Bhiry N, Lavoie M. 2021. Holocene dynamics of an inland palsa peatland at Wiyâshâkimî Lake (Nunavik, Canada). Écoscience:1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907975.

- Lemay E, Côté SD, Tremblay J-P. 2021. How will snow retention and shading from Arctic shrub expansion affect caribou food resources? Écoscience:1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1917859.

- Moran EJ, Lecomte N, Leighton P, Hurford A. 2021. Understanding rabies persistence in low-density fox populations. Écoscience:1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1916215.

- Narancic B, Saulnier-Talbot É, St-Onge G, Pienitz R. 2021. Diatom sedimentary assemblages and Holocene pH reconstruction from the Canadian Arctic Archipelago’s largest lake. Écoscience:1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1926642.

- Nozais N, Vincent WF, Belzile C, Gosselin M, Blais MA, Canário J, Archambault P. 2021. The Great Whale River ecosystem: ecology of a subarctic river and its receiving waters in coastal Hudson Bay, Canada. Écoscience:1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1926137.

- Payette S, editor. 2013. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 1. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 553.

- Payette S, editor. 2015. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 2. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 711

- Payette S, editor. 2018. Flore nordique du Québec et du Labrador - volume 3. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval. 711.

- Payette S. 2020. Louis-Edmond Hamelin (1923–2020): un géant de la géographie. Le Naturaliste canadien. 144(2):3–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/1071604ar.

- Payette S, Saulnier-Talbot E. 2011. Un demi-siècle de recherche au Centre d’études nordiques: un défi de tous les instants. Écoscience. 18(3):171–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.2980/18-3-3492.

- Pellerin S, Lavoie M, Talbot J. 2021. Rapid broadleave encroachment in a temperate bog induces species richness increase and compositional turnover. Écoscience:1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907976.

- Perreault J, Fortier R, Molson JW. 2021. Numerical modelling of permafrost dynamics under climate change and evolving ground surface conditions: application to an instrumented permafrost mound at Umiujaq, Nunavik (Québec), Canada. Écoscience:1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1949819.

- Rencontre de nordistes. 1967. Problèmes nordiques des façades de la baie de James: recueil de documents colligés par Hugues Morrissette et Louis-Edmond Hamelin à la suite d’une rencontre de nordistes à Moosonee, Ontario, en février 1967. Québec: Université Laval.

- Roy N, Woollett J, Bhiry N, Lemus Lauzon I, Delwaide A, Marguerie D. 2021. Anthropogenic and climate impacts on subarctic orests in the Nain region, Nunatsiavut: dendroecological and historical approaches. Écoscience:1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1932294.

- Royer A, Domine F, Roy AR, Langlois A, Marchand N, Davesne G. 2021. New northern snowpack classification linked to vegetation cover on a latitudinal mega-transect across northeastern Canada. Écoscience:1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1898775.

- Touati C, Ratsimbazafy T, Poulin J, Bernier M, Homayouni S, Ludwig R. 2021. Landscape freeze/thaw mapping from active and passive microwave Earth observations over the Tursujuq National Park, Quebec, Canada. Écoscience:1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1969790.

- Vincent WF, Côté SD, Bernier M. 2011. From boreal forest to high Arctic desert: a theme issue commemorating 50 years of research by the Centre for Northern Studies (CEN) in Eastern Canada. Écoscience. 18(3):iii–iv. doi:https://doi.org/10.2980/18-3-3497.