ABSTRACT

Many intersecting factors influence the identity, motivations, and experiences of women entrepreneurs. This paper explores the experiences of female water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) entrepreneurs in the context of the region of Nusa Tenggara in Eastern Indonesia. We conducted in-depth interviews with a diverse set of female WASH entrepreneurs, and applied intersectionality concepts in combination with the Gender at Work analytical framework [Rao et al., 2016. Gender at work: Theory and practice for 21st century organizations. Routledge] to analyze and present qualitative data. This approach and combined framing helped to unpack the varied identities and characteristics such as occupation, educational background, disability, social position, religion, age, economic status, and ethnicity that shape their experiences within societal structures including ableism, patriarchy, and social class. The findings demonstrate how all these aspects influence individual consciousness and capabilities, help to navigate, and challenge structural social norms that transcend ethnicity and religion, and build social networks, to support entrepreneurial activity and facilitate access to resources. This study has implications for development practitioners who can strengthen consideration of these complexities while designing training programs for private and public sector workforces with responsibility for WASH service delivery.

ABSTRACT IN BAHASA INDONESIA

Banyak faktor yang bersinggungan yang mempengaruhi identitas, motivasi, dan pengalaman seorang perempuan wirausaha. Naskah ini mengeksplorasi pengalaman perempuan pengusaha air, sanitasi dan kebersihan (water, sanitation, and hygiene/WASH) dalam konteks wilayah Nusa Tenggara di Indonesia Timur. Kami melakukan wawancara mendalam terhadap beragam perempuan pengusaha WASH, dan menerapkan konsep interseksionalitas yang dikombinasikan dengan kerangka analisis Gender di Tempat Kerja (Rao et al., 2016) untuk menganalisis dan menyajikan data kualitatif. Pendekatan dan pembingkaian gabungan ini membantu membongkar beragam identitas dan karakteristik – pekerjaan, latar belakang pendidikan, disabilitas, posisi sosial, agama, usia, status ekonomi, dan etnis – yang membentuk pengalaman mereka dalam struktur masyarakat termasuk kemampuan, patriarki, dan kelas sosial. Temuan penelitian kami menunjukkan bagaimana semua aspek tersebut memengaruhi kesadaran dan kemampuan individu, membantu menavigasi dan menantang norma sosial struktural yang melampaui etnis dan agama, dan membantu perempuan pengusaha WASH membangun jaringan sosial, untuk mendukung aktivitas kewirausahaan dan memfasilitasi akses ke sumber daya. Studi ini berimplikasi bagi praktisi pembangunan yang dapat memperkuat pertimbangan mereka tentang kompleksitas identitas dan karakteristik saat merancang program pelatihan untuk tenaga kerja sektor swasta dan publik yang bertanggung jawab atas pemberian layanan WASH.

Introduction

This paper investigates the intersectional aspects that influence the experiences of female entrepreneurs in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector business activities. Our research aim is to extend studies to date, which examine gendered experiences of micro entrepreneurs (Indarti et al., Citation2019), given the significant gendered inequalities that exist in the context, but did not consider other dimensions of marginalisation or discrimination. We explored how heterogeneity among women, in terms of their socio-economic status, cultural values, occupation, ableism (discrimination in favor of able-bodied people), educational background, age, and position in the community, shaped their experiences as a female entrepreneur, particularly in low- and middle-income, predominantly patriarchal context.

While several WASH programs and recent research focus on gender, diversity, and inclusion among households and communities accessing WASH services (Mactaggart et al., Citation2021; Water for Women Fund, Citation2021), in the development sector, there is also an emerging focus on gender and diversity amongst those entities responsible for WASH service delivery, including both public (Soeters et al., Citation2021; Grant et al., Citation2019a) and private sector actors (Water for Women, Citation2022). Such efforts have been prompted by recognition that across many contexts, women are absent from the paid workforce that supports WASH services (Das, Citation2017; World Bank, Citation2019). However, bringing women into the picture needs to be done carefully. A comprehensive perspective on the many structural factors that influence the experience of female WASH entrepreneurs and how they are perceived in their social environments as presented in this article is an important contribution to both academic discussion and development programming practice.

This study builds up from the foundation laid by previous research, which conveys the mixed experiences of women in WASH-related economic activities due to a range of structural barriers. Specifically, previous research on WASH enterprises has highlighted the challenges faced by female business owners in terms of their low education levels, and their ability to cope with late payments by customers and negotiate with suppliers and government officials (Leahy et al., Citation2017). Research also points out their differential access to low-interest capital as compared with men (Leahy et al., Citation2017; Soeters et al., Citation2020), and time availability due to the social expectations of managing household and care responsibilities with income generating activities (Leahy et al., Citation2017; Soeters et al., Citation2020; Willetts et al., Citation2016; Grant et al., Citation2019b).

Community perceptions related to professions that involve manual labor (such as masonry and toilet ring manufacturing) being unsuitable for women, social norms regarding women’s primary role in the household (Mebrate, Citation2020; SNV, Citation2021), risk averse attitudes (Murta et al., Citation2015; Willetts et al., Citation2016), mobility restrictions (Mebrate, Citation2020; Soeters et al., Citation2020; Grant et al., Citation2019b), and lack of working space (Mebrate, Citation2020) have also been noted as common barriers that women face when it comes to scaling-up their business. As such, previous research signals caution in assuming that involvement in WASH economic activity will be empowering for women (Indarti et al., Citation2019), and that empowerment is a more complex process (Grant et al., Citation2019b), and this paper takes this basis as its starting point.

Building from these previous studies, this research examines the ways in which women navigate structurally imposed challenges from an intersectional perspective and documents their experiences. An intersectional perspective highlights how the social and structural environment interacts with the multiple identities of an individual. The initial concept of intersectionality is closely linked to black feminism which recognizes the importance of interactions between race and gender (Crenshaw, Citation1991). According to Collins (Citation2000, p. 299), intersectionality is an “analysis claiming that systems of race, social class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, and age form mutually constructing features of social organization, which shape Black women’s experiences and, in turn, are shaped by Black women.” Furthermore, developed concepts of intersectionality aim to take into account the impact of multiple identities on discrimination which intersect and reinforce each other (Prins, Citation2006). Other studies that focus on women micro-entrepreneurs also highlight how intersectionality provides an analytical perspective on complex experiences of entrepreneurship that are impacted by the multiple identities that people hold (Abbas et al., Citation2019; Brydges & Hracs, Citation2019). Past literature touching on this area has examined the experience of women with disabilities (Mulira & Ndaba, Citation2016; Williams & Patterson, Citation2019), the role of informal institutions such as socio-cultural structures (Roomi et al., Citation2018), support of family members (Constantinidis et al., Citation2019; Lenka & Agarwal, Citation2017), age (Stirzaker & Sitko, Citation2019), and how these define women’s entrepreneurial success. This study extends existing research by combining an existing theoretical framework focused on gender equality in the context of the workforce (the Gender at Work framework) with the lens of intersectionality. It applies these to provide insight on the experiences of Indonesian female entrepreneurs in the WASH sector, particularly how prevailing structures interact with unique aspects of identity and characteristics to shape their life experiences.

Conceptual framework

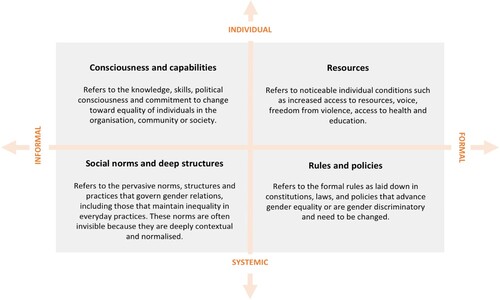

The Gender at Work framework (Rao et al., Citation2016) was used to guide the research, including informing the interview guide and situating our findings. This framework sheds light on gender dynamics within a work context and provides a perspective of positive gender equality change. It recognizes the interrelationships between formal and informal societal and workplace structures and separates individual and systemic dimensions (see ).

The Gender at Work framework is comprised of formal structures, including access to resources at an individual level (such as micro-capital), along with the encompassing rules, laws, and policies at a systemic level (such as the rules of lending by formal financial institutions). The informal structures include consciousness and capabilities at an individual level (such as the knowledge, skills, and commitment to drive change), with the underlying discriminatory social norms and practices that permeate deep and govern gender dynamics within society. Social norms can be understood as the set of expectations, rules, and values that women and girls have to constantly negotiate and resist, which maintain their subordinate position in society (Rao et al., Citation2016).

The four quadrants of the Gender at Work framework are conceptually different to one another, but as our research revealed, when applied, were not always distinct but rather fluid. Issues and experiences often cut across more than one quadrant, alluding to the combined framing of intersectionality (Rao et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). This framework, with its specific focus on work and organizations, contributes to the broader frame and aim of women’s empowerment, taking Cornwall and Rivas (Citation2015, p. 404) view on women’s empowerment as a process of transforming power relations in favor of women’s rights and social justice and the transformation of economic, social, and political structures.

We integrated the lens of intersectionality—including structures such as ableism and ageism interacting with social position, occupation, and other characteristics within each quadrant of the framework to investigate women’s experiences. These experiences included both aspects of oppression in relation to prevailing structures, and also of potential opportunity by drawing on the individual’s accumulated social capital. In this context, social capital may include factors such as local community participation, connections with local community and neighbors, family and social connections, and work-related connections (Onyx & Bullen, Citation2000).

An intersectional perspective enabled an understanding of the multiple fluid and stable identities of individuals (Abbas et al., Citation2019), and their response to complex social environments and context (Dy & Agwunobi, Citation2019) and entrepreneurial experiences. Based on Crenshaw’s arguments (Citation1991), an intersectionality lens supported the analysis in considering how oppressive constructs in society intersected in complex and compounding ways for our female participants.

Methods

Research context and participant selection criteria

The research was conducted in the archipelago of Nusa Tenggara which lies in eastern Indonesia. Along with having one of the lowest per capita incomes in the country, this region is characterized by poor infrastructure, a remote location with widely dispersed islands, and a complex social structure (Barlow et al., Citation1991).

Since eastern Indonesia is an extensive and diverse region, the focus included several districts, namely Sumbawa, Central Lombok, East Lombok, and Mataram in Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT) province, and Malacca, Manggarai, and Kupang in Nusa Tenggara Barat (NTB) province. Our research partner, Yayasan Plan International Indonesia (Plan Indonesia) (YPII), conducted projects located in these provinces, which enabled identification of research participants through their networks. Additionally, we identified other networks of development partners that had supported training and development of entrepreneurship in the sanitation sector. While a quarter of the population in NTB practice open defecation (UNICEF, Citation2019b), NTT has one of the lowest sanitation coverages in the country (UNICEF, Citation2019a). In this context, prior to the YPII project, there were few women-owned-and-operated WASH enterprises in our research locations.

Prevailing socio-cultural norms in the area tend to be patriarchal, with men dominating political and public participation and women’s role restricted to domestic and household tasks (Shamier et al., Citation2021). Patriarchal culture has a strong bearing on women’s thinking, attitude, and behavioral patterns (Djobo et al., Citation2023), in turn reinforcing traditional gender roles in society. In NTT, customary norms of women taking care of husbands, children, the elderly, and the house are prevalent, and women are raised from childhood to conform to these expectations. Furthermore, women’s participation in community activities is also dictated by social and familial responsibility (Djoeroemana et al., Citation2007). Such norms are compounded when we consider ableism and ageism (Bahtiar, Citation2021). Stigma and discrimination against women and girls with disabilities is a pervasive social norm, even from their own family members, leaving this group highly vulnerable to violence, abuse, and isolation. Although, there are beginnings of positive change in this regard (Daniel et al., Citation2023; Rembis & Djaya, Citation2020). Christianity is the dominant religion in NTT, contrary to the Muslim majority NTB, which follows the country’s dominant religious practice, Islam.

Data collection approach and methods

A qualitative research approach comprising in-depth interviews with eleven women leading WASH-related enterprises, including one woman with a disability, was undertaken in 2021. This includes preliminary scoping interviews in the early stages of this research which were conducted in February 2020. Due to COVID-19 restrictions in Indonesia during the time of this research, data collection in 2021 was through phone interviews with research participants. A semi-structured interview guide was followed, informed by the Gender at Work conceptual framework presented in the previous section.

Profile of research participants

The research participants were diverse women entrepreneurs working in varied aspects of WASH, with some currently engaged in their business (active), and others, not (dormant). Across the eleven participants, the sample included diversity in educational qualifications, age, ableism/ability, socio-cultural background, and economic status. Participants were identified from a list of individuals who previously participated in a Plan Indonesia training program. The training program aimed to support and mobilize private sector engagement in WASH to address the need for WASH products and services in the relevant communities. The skills acquired through this broader program were expected to enable participants to develop new businesses in sanitation and hygiene. These included latrine construction services and products such as reusable face masks, menstrual pads, and reusable diapers. Among trainees, not all participants went on to set up businesses and the sample for this research was drawn from those who did. The age of the participants fell between 32 and 56 years old and all participants were married. As described earlier, these participants had participated in trainings offered by either NGOs, development programs, or agencies of the Government of Indonesia (GoI).

A subset of the sample held government staff roles in addition to their WASH business, such as with the Department of Health or as a health worker. In addition, several participants also had other sources of income. At the time of the interviews, six entrepreneurs had an active business (attended the training and started a business, which was active at the time of the interview), and five had a dormant business (attended the training and started a business which was no longer active at the time of the interview). Many participants held previous or current community-related voluntary roles. A profile of the research participants is provided in .

Table 1. Profile of the research participants

Although this research sought out a range of diverse participants that would incorporate varied identities, since an essential criterion to be included in the sample was to have an active or dormant WASH business (as opposed to training participants who never started such a business), most participants held some sort of elite status in a local socio-cultural context. Drawing on previous work by Salverda and Abbink (Citation2013) and Constantinidis et al. (Citation2019), elite status is associated with an individual’s economic class, educational level, and occupation (particularly with respect to employment in government). These aspects of elitism interacted with opportunities to build social capital such as local networks and position in a society. While the sample did not encompass the full diversity of women in the local context, particularly with respect to more marginalized groups, it did contain sufficient diversity to permit analysis from an intersectional perspective and provide valuable implications for development programs.

Results

The findings are presented according to the Gender at Work framework dimensions, which are (1) consciousness and capabilities, (2) social norms and deep structures, (3) resources, and (4) rules and policies. We ordered our findings in this sequence to first place a focus on the individual and their agency within their work and societal context and second, to pay attention to how they navigated their path as agents of change rather than passive recipients oppressed by unequal structures and norms (Carrard et al., Citation2022).

Consciousness and capabilities

Our findings demonstrate how the consciousness and capabilities of participants were shaped by their disability, age, occupation, and related societal structures. Overall, interviews revealed that previous life experiences provided participants with self-confidence and social awareness. In turn, these experiences created the motivation to start a socially oriented business, to challenge stereotypes, and to enable access to necessary resources.

One woman entrepreneur with a disability had developed a determined and optimistic mindset which led her to set up her business in a way that offered opportunity to people with disabilities in her community. Her early life experiences included struggles to navigate oppressive and systemic ableism in society, such as discrimination based on her physical disability in school during childhood and later, when attempting to access a loan from a bank. These experiences gave her determination to ensure others didn’t face the same oppression, hence her focus on leading a disabled people’s organization and her efforts to build her own connections among the local government and NGOs. She was successful in these roles and over time, she managed to receive large production orders that support the development of human capital among other people with disabilities participating in the business.

Age impacted the ability of female business owners, with older women demonstrating easier access to networks and resources and younger women facing time constraints due to reproductive roles. In the research locations, older women held positions of influence in civil society organizations and tended to be active in community activities. Their relatively older age, community position, and years of experience gave them access to strengthened kinship-based socio-cultural-economic networks. These local connections enabled access to raw materials, financial capital, and human capital to support their activities. Older women also enjoyed greater respect compared to younger female business owners. Younger female business owners tended to have young children and their reproductive roles in the home constrained the time available for business activities. This is another example of how societal structures and norms dictate the role of women even within the private space of the household based on age and life stage.

Participants with existing government staff roles as their occupation demonstrated high levels of confidence to learn new skills, an established basis of trust in their community, and social-minded interests to empower other vulnerable women. Individual consciousness influenced by participants’ occupations was found to have an impact on their business experience and their access to and development of social capital. As an example, one of the research participants, who was a young district health worker at a community health center, was motivated to make face masks for her family out of concern for their health as there were no masks available in her area. She used her mother’s old sewing machine and taught herself by watching YouTube videos. Over time, her friends and colleagues at the health center started placing orders and also helped to market her product via their positive testimonials. Additionally, she was able to secure large orders for her product due to her social capital as a government health worker (occupation) and active involvement in community organizations. While her status as a health worker created a sense of trust among potential customers, her active involvement in community welfare trainings and activities within the Plan Indonesia Water for Women project helped to secure a collaboration with Plan Indonesia to produce cloth masks for them. To meet the increase in demand, she recruited a widowed woman who lost her income due to COVID-19 and a couple with disabilities and taught them how to sew and make face masks. Her past experience of running a business in waste recycling, along with the training she received from Plan Indonesia in entrepreneurship and financial management, gave her the confidence to set up her present business, to establish her own brand of face masks, and to provide a livelihood for other vulnerable people. This is a powerful example of how one woman’s social capital, social consciousness, and values were leveraged to contribute to wider empowerment outcomes for others in society, beyond business success.

In summary, the female business owners, age, and elite status with respect to their past experience, occupation, social position, and accumulated social capital influenced individual consciousness and capabilities in their entrepreneurial work. Also, previous discriminatory experiences of a disability in a society founded on ableism built the necessary character strength for one participant and her sense of solidarity with others living with a disability.

Social norms and deep structures

Several social norms in Nusa Tenggara led to differentiated experiences of participants based on their life stage, existence of a disability, socio-economic class, and family structure and arrangements. At the same time, certain other social norms affected all participants similarly, in spite of ethnic and religious differences.

Social norms at the household level in Nusa Tenggara placed women at the center of domestic responsibility. This meant that reproductive roles, including looking after children and domestic chores in the home were left to women. As such, these roles were considered primary and a higher priority than any business-related activities or training. This left women with young children in a difficult position to balance these different demands on their time.

When my children were small, I really took care of them myself with my own hands … . all domestic work, I do by myself with my own hands … Everyday, I always prepare all the needs of my husband, [from] clothes, food, to the pen that my husband will bring to work … . (Participant 5, personal communication, February 01, 2021)

In general, all research participants who were married women needed to request their husband’s permission in many areas, including accessing their own personal financial resources, taking training, or carrying out specific activities related to their business. A participant noted that marketing of sanitation products entails socializing with the community, inviting them to change habits, and building trust, so that they realize the importance of buying and using the sanitation products. Behavior change requires frequent group meetings and since the majority of the community members are available in the evening or at night, this hindered women’s participation in such activities—either due to the need for permission from the husband or to the priority given to domestic responsibilities.

Based on the religious teachings and cultural norms in Sumbawa, which is dominated by Muslims, and in Manggarai, which is dominated by Christians, women are positioned as secondary to men (Prikardus & Frederik, Citation2020). The permission of the husband is necessary for any decision that women take. In situations where a participant’s husband resided in a different location from the family (two women in our sample), these women demonstrated greater freedom and flexibility to choose their activities. For instance, they were able to easily attend training and run their business in the community context. This finding was consistent across the two districts, in spite of ethnic and religious differences. This is an interesting point to note as interpretation of religious teachings is embedded in conformity to socio-cultural norms in our research locations.

Among the participants, there were also specific cases where men directly contributed to childcare and domestic roles (four cases in our sample) and were positive in their support for their wife’s business activities. These positive deviance cases demonstrate the potential for wider structural transformation in gender roles in the Nusa Tenggara society. The key influencing factors were education level as well as the family and social context of the relevant men. This meant that the husbands mentioned could go beyond existing taboos that held most men back from taking on such roles.

… .my husband is very supportive; making me happy to do this job. Because I'm not bothered by him for example, I must prepare his meals, no. He keeps up. When I work, he can also prepare food by himself. When I have a lot of mask requests, I find it difficult to deliver the materials to the tailors, my husband helps me … Thank God, I have a husband that can do any work (including domestic work). (Participant 6, personal communication, January 21, 2021)

One of the older research participants held a contrary view to this norm that viewed latrine businesses as unsuitable for women. Her opinion can be attributed to her relatively elite position as a government officer (civil servant) who also co-manages a successful and sustainable business along with her husband. The support of her husband also provided access to family finances for initial capital. However, in spite of her being the only female sanitation entrepreneur in the district and the fact that she initiated the business, the community views the business as jointly run by the couple, reflecting deeply oppressive societal constructs. This also highlights the lack of women role models which discourages other women to pursue this business and reinforces the occupational stereotypes.

Systemic ableism constructs perceptions of people with a disability as incapable. However, this research demonstrates how such social norms can be challenged and gradually changed. One female business owner, who was also a district health worker, was a remarkable example in this regard. She initially felt reluctant about the idea of employing people with disabilities. However, once she gave it a chance and noticed that they were able to develop the necessary skills, she changed her mind and became an advocate for greater inclusion. She made efforts to empower disabled folks through employment opportunities and developed increased empathy and patience. This experience demonstrates a step towards increased critical consciousness with potential to incrementally transform wider discriminatory structures.

To summarize, our findings highlighted strong prevalent social norms concerning women’s reproductive roles, particularly impacting women with younger children, regardless of religion or ethnicity. Meanwhile, evidence of changing attitudes towards people with disabilities demonstrated that existing perceptions could be overcome, allowing people with disabilities to gain employment.

Resources

Women without a disability and with elite status granted through their economic class, occupation, and educational level (three women across our sample) were able to access financial capital more easily to start their businesses. This included giving them access to informal rather than formal mechanisms to secure finance, such as through family members. However, they, like all participants, required approval and permission from husbands, reflecting the social norms described earlier. Borrowing finance from formal institutions required women to address stringent requirements including availability of a guarantor (usually a male family member), proposal-writing skills, acquisition of a business license in their own name, and capacity to meet repayment requirements. As a result, across the sample of participants of diverse identities and backgrounds, women tended to avoid bank loans (three women across our sample).

One participant with a disability faced particular challenges, as ableism influenced her ability to access formal mechanisms of finance. She experienced direct and overt discrimination when dealing with bank officials and despite her proposal fulfilling all the relevant requirements, her application was rejected. The low level of trust in her ability to repay and succeed in her business is a demonstration of systemic ableism within formal institutions.

Once we [LPDS, organization for people with disabilities] wanted to borrow money from the bank, but the bank didn't give it, they said we were sick. (Participant 7, personal communication, January 20, 2021)

Local level village funds were another source that were often accessed by the entrepreneurs for business activities and similar to formal sources of finance, a person’s elite status in terms of social position and networks was found to influence awareness of and easy access to these funds. One of the latrine business owners was able to easily access these resources due to her active role in various community associations and close connection to the village head. Her elite position also provided access to spaces for making and storing her products, as well as to avenues for promotion and marketing. Similarly, a government district health worker was able to leverage her occupation to access market information about potential customers.

Age was found to influence the access to and use of different marketing strategies. While the younger women in our sample (three women under 40 years old) used social media to promote their products, the older women (three women over 40 years old) used their local networks built over the years and their connections established while holding other positions in their respective communities. This could be explained by different levels of technological literacy. On the other hand, another reason behind this difference can be attributed to cultural practices where most women in the research locations are expected to move to their husband’s village after marriage, where younger entrepreneurs may not have a strong local network to tap into for marketing their products.

In addition to financial support and other forms of support and approval from the husband, women with extended family and community were more easily able to run their business. Women entrepreneurs with younger children found it particularly challenging to manage the demands of running a business, attending training programs, along with childcare and domestic responsibilities. In such cases, where support from the husband or other family members was forthcoming (all three younger women in our sample), it was greatly valued. Activities that benefited from family support, including from husbands, included marketing, financial management, access to raw materials, quality assurance, and product deliveries. At the same time, the level, type, and form of support from their husbands (in domestic and business activities) varied from one individual to another as this was influenced by socio-cultural understanding which intersected with interpretation of religious teachings.

Thus, this research highlights how women’s pre-existing social status and networks impacted their access to finance through formal mechanisms, and that women with disabilities face particular challenges. It also demonstrates how differently aged women employ different approaches to marketing and communications based on their familiarity with technology and access to social networks, and that for women with children, extended family support was particularly important.

Rules and policies

Formal rules and policies relevant to small-scale businesses were more accessible to participants who were government employees, who actively participated in community organizations and who belonged to a higher socio-economic status.

Access to local government funds for their business was easier for some participants compared with others. One of the entrepreneurs in our study was considered an “elite” as she had served in various positions in several village community organizations. Her position and social status in the village, along with her good relations with the village head played a significant role in her gaining access to village-level resources to support community latrine provision.

Similarly, a woman’s social position as the head of a disabled people’s organization helped her to establish good connections with other government and non-government organizations. Even though she had a disability, her social status and networks enabled awareness of the provincial regulation concerning the protection and fulfillment of the rights of people with disabilities. Therefore, she was able to use this regulation for raising awareness among other people with disabilities about their rights and advocating in support of people with disabilities to become entrepreneurs to other NGOs.

Government support for latrine provision could also be detrimental to some businesses and served to create competition for women’s businesses, resulting in decreased motivation and success. Those participants with lower socio-economic status and limited social connections were particularly impacted.

Formal banking regulations were discriminatory against women. This was because they included requirements for collateral. Most assets such as land were held in the name of the household head, which in the majority of cases was a man rather than a woman. Women are less likely to own property in their name, unless inheriting it from family, or buying property in their name. This situation meant that women were forced to request their husbands to be involved in financial transactions, including signing credit agreements and providing finance documentation. These factors contributed to participants avoiding formal bank loans.

Thus, our research demonstrates that access to information about various policies and schemes for business support is influenced by social position and connections, and this meant that some participants had greater access to local village government funds than others. In addition, formal regulations requiring collateral for bank loans discouraged most women from taking bank loans since they lacked assets in their own name.

Discussion

Our discussion covers three areas—first, we consider the additional insights through combining intersectionality and gender equality provided and their application to the field. Second, we compare our findings to recent research on intersectionality and women micro-enterprises in Indonesia and elsewhere, followed by a focus on the implications of our research for development programs that aim to support diversity among WASH enterprises.

Intersectionality and the gender at work framework

This research supplements existing literature on female entrepreneurship by highlighting the enablers and barriers a diverse group of female WASH entrepreneurs in Indonesia face. It not only demonstrates an application of the Gender at Work analytical framework (Rao et al., Citation2016), which has a core focus on gender equality in the workforce, but also advances the framework by adding consideration of intersectionality within each quadrant of the framework. By taking this approach, our intent was to understand the confronting complexities, diverse influences, structures of power and inter-connected systems that come into play when one considers intersectionality as an analytical tool (Soeters et al., Citation2019; Vaiou, Citation2018). These complexities inevitably influence the individual and systemic, as well as formal and informal dimensions identified by Rao et al. (Citation2016). This approach and combined framing supported consideration of diverse identities and corresponding societal structures, and their impacts on experiences of female entrepreneurs. A key insight was that these intersectional characteristics were not distinct and unrelated from one another, but often intersected with each other, shaping women’s experiences, challenges, and opportunities. An understanding of this heterogeneity has significant implications for development partners and NGOs so that they may consider these complexities when designing development programs for micro-entrepreneurs in the WASH sector. In addition, overlaying the Gender at Work framework with an intersectionality lens will be important for future research on female entrepreneurship in similar research contexts.

The influence of “eliteness,” disability, age, religion, and family support on entrepreneurial success

“Eliteness” emerged as a fluid but key concept in the context of our research locations that defined which aspect of a woman’s identities played a dominant role in influencing her entrepreneurial experiences. While the definition of an “elite” in modern societies is most commonly related to positions of power, prestige and influence, these concepts can be relational (Schijf, Citation2013) and contentious. Our findings revealed that most of the participants in our research were “local elites,” with the factors shaping their elite-ness being heterogeneous and extending beyond socio-economic class to their educational level and occupation. This resonates with elements of an anthropological approach to elites which defines them as “societal frontrunners and usually the loci of dynamics and change” (Salverda & Abbink, Citation2013). Constantinidis et al. (Citation2019) define the “elite category” of women entrepreneurs with reference to economic class, higher (often tertiary) education, previous work experience, personal and professional networks, and strong financial and moral support of husbands and families. While our research covered all these aspects, additionally, we included the experiences of women with disabilities, women with younger children, social status, differences in age and occupation, and to a lesser extent, ethnicity, and religion. Therefore, our definition reflects a broader and non-categorical understanding of a local elite at the community level.

Stirzaker and Sitko (Citation2019) find traditional roles and social expectations to be barriers for older women to establish their entrepreneurial activity in the context of a developed country. In our research locations, we observed that certain middle-aged female business owners have relatively easy access to resources and overcame many social norms by virtue of their elite social position, as they were active in various community activities, had established relations with local government officials, and were well-known by local organizations. Cawood and Rabby (Citation2021) also highlight similar characteristics that mediated participation of women in community-based organizations (CBOs) engaged in WASH projects. At the same time, we also saw other aspects of elite-ness in terms of the occupation of a government district health worker, which influenced a WASH enterprise due to the common focus on hygiene behaviors and access to sanitation.

Studies in the context of entrepreneurship have focused on the intersection of gender and disability, revealing the motivations and unique challenges faced by women with disabilities as entrepreneurs. Rugoho and Chindimba (Citation2018) talk about the medical model and charity model of disability wherein the former views people with disabilities as sick people who are discouraged to engage in innovative activities such as entrepreneurship or any kind of employment, and the latter views them as victims of impairment, pitied by the community. Our findings resonate with the societal stereotypes shaped by these models as illustrated by the treatment of our research participant when she approached a bank official for a loan as well as the initial hesitation of another participant to hire people with disabilities as her employees. Negative societal attitudes towards the capabilities of people with disabilities are often exacerbated in case of women with disabilities. While Mulira and Ndaba (Citation2016) found such perceptions evident in trainers of micro-enterprise learning programs, our research identified manifestation of these norms by family members through feelings of shame towards the disability of their daughter, restricting her access to educational opportunities. On the other hand, we also found evidence of how these stereotypes were overcome and how social and human capital were developed and maintained (Williams & Patterson, Citation2019) by women with disabilities to achieve positive business outcomes and create livelihood opportunities for vulnerable people.

We did not see a significant difference with respect to religion which is interesting in itself due to the strong influence of religious teachings on economic activity and socio-cultural roles (Aryaningsih et al., Citation2017; Koning, Citation2011). In Islam, religion has a role to play in household financial management (Arsyianti, Citation2011) and how families invest and spend their money on business activities is one pertinent example. There is no Islamic law which differentiates between women’s and men’s access to their household finances. Rather, it is the interpretation of religious teachings which influences personal values (Dana, Citation2009) and the segregation of gendered roles in entrepreneurial activities, along with local traditions or societal values of a community (Rafiki & Nasution, Citation2019). Similarly, in our research, while we found that participants’ entrepreneurial experiences are shaped by a combination of personal values, social norms on gendered role segregation, and collective community traditions, we additionally observed similarity in these social norms across different religions and ethnicities. Group ethnicities have also been shown to influence entrepreneurial decisions via the pathway of social identity and culture (Cahyono et al., Citation2021). While we propose that the intersection of religion and ethnicity with prevalent social norms can certainly influence entrepreneurial activities, it would be interesting to explore the pathways of this complex aspect further.

The role of family support in women-led enterprises is a significant factor shaping women’s experiences, particularly in case of women with younger children. Similar to Constantinidis et al. (Citation2019), we observed direct or indirect involvement of the spouse in the form of providing start-up capital, being a guarantor for bank loans, taking on advisory roles, and contributing to various business activities, as well as providing moral support and sharing domestic responsibilities. Guidance from extended family members in terms of information about the market, customers, finance, and resources is also of key importance. In Pakistan, Roomi et al. (Citation2018) found the lack of family support to be the biggest barrier for any woman starting her own business, but at the same time, a supportive family was cited as the greatest strength for women-led businesses. These two scenarios are further reflected in our findings and also highlight how women often exert their agency while convincing unsupportive family members in favor of their entrepreneurial activities, sometimes succeeding, sometimes not. As such, women experienced either oppression or empowerment in relation to their particular family situation.

Implications for development programs that aim to support diversity in WASH enterprises

This research highlights important considerations for development programs that focus on WASH enterprises, and these also extend to women’s enterprises in general. Given the imperative to increase diversity in the WASH workforce, it is important to consider, in practice, how this can be achieved in an empowering manner, given intersecting societal structures and social norms that may serve to limit or reduce the opportunity and potential for less well-positioned women to participate and contribute as female business owners. The results presented in this paper demonstrate the impact of differing age, socio-economic status, occupation, physical ability, and educational background on women’s experiences. The paper has also shown how many of the research participants, through their business activities, not only successfully navigated the oppressive social structures through their business activities, but also reshaped them. Both of these findings have important implications for development practitioners.

This research reveals significant potential to empower and provide independence for people with a disability through provision of support. Moreover, women with disabilities through their social networks (such as with Disabled People’s Organizations, etc.) can provide employment opportunities to other vulnerable populations in society (Usman & Projo, Citation2021). Therefore, there is evidence which supports a clear need to recognize the value of engaging people with disabilities, particularly women with disabilities, and the strengths that they bring in terms of generating further sources of employment and challenging social norms.

While tackling social norms can seem like an onerous task, WASH enterprises can provide an entry point for changing gendered norms on the condition that explicit attention is given to this area and associated strategies are developed. Development partners can specifically target men in their WASH training programs, as spouses or other family members, particularly those who exhibit positive deviance and are interested in sharing household roles, can offer support to women interested in running a business (Cavill et al., Citation2018; Mihretu & Uraguchi, Citation2017). Training programs can also incorporate topics related to questioning gender roles within a household, time spent for various household and business tasks, and negotiation skills (required for running a business as well as managing the expectations of the spouse and other family members) (SNV, Citation2021). Any entrepreneurship training program can benefit from recognizing that being an entrepreneur is woven with other aspects of a woman’s life. Therefore, it would be useful to prompt explicit discussions on how to manage different and concurrent roles and to encourage the sharing of household tasks. This can help promote supportive spouses and address the differentiated needs of women with young children, as they appeared to be the ones who tended to discontinue their enterprise due to the double burden of business and childcare responsibilities (SNV, Citation2021). It is recognized that shifting norms is a long-term prospective, and in the meantime, direct support could be provided in the form of childcare, and sharing the experiences of men who participate in household work can encourage changed practices.

As indicated in earlier research (Indarti et al., Citation2019), to ensure a more empowering experience, development partners should invest effort in use of appropriate criteria with careful targeting and screening prior to accepting potential participants for training programs, and in gaining an early and detailed understanding of participant motivations, interests, and identities. Such insight can then inform program design and better match activities and support differentiated needs. A tailored approach to follow up action after training designed to mentor female entrepreneurs during the early stages of their business is also likely to be beneficial in ensuring diversification of the workforce and in recognizing the unique challenges faced by different women of varied identities in a timely fashion. At the same time, such screening processes should include diverse selection criteria so that they do not result in benefitting elite women only.

This research revealed a range of skills that women interested in starting their own business need to acquire. This includes proposal writing to enable access to finance, marketing skills matched to women’s particular life stage, digital literacy, and existing social networks. Training programs should also take into account the differentiated access to information about local or village government funding support and provide background to support diverse women to navigate the complex requirements of different lending institutions.

Lastly, development partners can play a role in shifting the broader context at local and district level for WASH-related businesses. For instance, other studies have shown how linkages with local financial institutions can support easier access to capital (Anggadwita et al., Citation2015). Development partners also have a role to play in supporting linkages with microfinance organizations as well as networks of female entrepreneurs which have been successful in supporting women to share experiences with one another and providing access to mentoring support (Lenka & Agarwal, Citation2017).

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the diverse experiences of women of different identities engaged in WASH businesses in Nusa Tenggara. It extends previous research on the topic which focused on gendered experiences but without attention to intersectionality. The application of an intersectionality lens to the Gender at Work framework provided an effective approach to explore women’s unique experiences and recognize the value and criticality of diverse characteristics in supporting women entrepreneurs to navigate their social environments to benefit both their business and them.

The findings are wide-ranging, and demonstrate aspects of both oppression and challenges, particularly for entrepreneurs of lower socio-economic status. The findings also illustrate the means by which women of different backgrounds navigate and overcome some aspects of existing societal structures. The key aspects that impacted women’s consciousness and capabilities were identified as disability, age, and occupation. Meanwhile, several social norms, particularly with respect to reproductive roles, were pervasive across different identities; for instance, across different religions or ethnicities. Social norms about reproductive roles significantly affected women of a particular age, at the life stage of having young children. Discriminatory attitudes against people with disabilities were identified, particularly with respect to access to finance. However, the study also revealed how attitudes can change and highlighted the capabilities of people with disabilities developed through their participation and employment in WASH enterprises. Social networks were found to be important for entrepreneurial activity, and women’s occupation, age, and participation in community-related organizations and activities were key aspects of identity that shaped such networks.

For development partners interested in supporting diversification of the WASH and other areas of small-scale entrepreneurship, this study provides new insights and implications that can inform better strategies which better address the different challenges and barriers that existing societal structures create for women entrepreneurs. Furthermore, we highlight that there is opportunity to reshape these societal structures over time and the need to intentionally apply strategies that can facilitate wider change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (10.1080/12259276.2023.2292882)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Avni Kumar

Avni KUMAR is a Senior Research Consultant at the University of Technology Sydney—Institute for Sustainable Futures. She specializes in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), with a cross-cutting focus on gender equality and social inclusion (GEDSI) and climate resilience in WASH. She has a background in development economics and has worked in various capacities with government, civil society, private sector and multilateral organizations. Avni has been a part of several projects related to women in the WASH workforce as well as promoting equality and inclusion in WASH programs. She recently led a research project on fostering inclusion and diversity amongst female WASH entrepreneurs in Indonesia, and is involved in several projects that touch upon the impact of climate change on the WASH needs of women, girls and other vulnerable populations in communities. Email: [email protected]

Mia Siscawati

Mia SISCAWATI is a lecturer at and the head of Gender Studies Graduate Program, School of Strategic and Global Studies, Universitas Indonesia. She also teaches at the Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Indonesia. Her expertise covers feminist anthropology, feminist ethnography, feminist political ecology, feminist agrarian studies, gender and environment, gender and natural resources, gender and forestry, gender and land tenure, gender and development, gender and human rights. She has participated in several international collaborative research projects and has been actively involved in international professional associations. Additionally, she has been actively involved in social movements in Indonesia, which include women's movement, indigenous peoples’ movement, environmental movement, and natural farming movement. Email: [email protected]

Septiani Anggriani

Septiani ANGGRIANI is a researcher at the Gender Studies Graduate Program, School of Strategic and Global Studies, Universitas Indonesia. Her expertise covers gender and disability inclusion in WASH, gender and infrastructure, gender and employment, gender and development. She has more than 10 years of experience in project management and evaluation, particularly on projects financed by ADB, DFAT, World Bank, JICA and the Government of Indonesia. She has worked as a research assistant, project associate, and surveyor engineer in several research studies, and has experience of organizing dissemination workshops as well as being involved in preparing research reports. Email: [email protected]

Ratnasari

RATNASARI is a researcher at the Center of Gender Studies Program, School of Strategic and Global Studies, Universitas Indonesia. Her expertise covers gender and environment, gender and natural resources, gender and agriculture, gender and land tenure, gender and development. She has participated in several international and national collaborative research projects and has been actively involved in social movements at grassroots level. In 2002, she joined Yayasan Rimbawan Muda Indonesia (RMI) and now serves as associate of RMI. She received scholarship from UC Berkeley and Ford Foundation on 2012 for joining Beahrs Environmental Leadership Program (ELP) Summer Course UC Berkeley “Sustainable Environmental Management” at University of California, Berkeley, USA. Email: [email protected]

Nailah

NAILAH is a researcher at the Center of Gender Studies Program, School of Strategic and Global Studies, Universitas Indonesia. She plays a role in conducting feminist qualitative research including designing and managing research methods such as data collecting, data analysis, conducting an in-depth interview, and facilitating focus group discussion. Nailah has participated in some international and national research projects, workshops, and training on some issues including gender and WASH; youth, gender, and extremism; gender and Islamic moderation; gender and community livelihood. She has experience in managing and facilitating a research workshop, conference, and training for trainers as a researcher, writer, and facilitator. Email: [email protected]

Juliet Willetts

Juliet WILLETTS is a professor at the University of Technology Sydney—Institute for Sustainable Futures. She leads applied research to improve development policy and practice, addressing social justice and sustainable development, including achievement of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). She is a recognized expert in the field of water and sanitation in low- and middle-income country contexts, and also works on gender equality, civil society role in development, governance and accountability, climate change, urban development, monitoring, evaluation and development effectiveness more broadly. Email: [email protected]

References

- Abbas, A., Byrne, J., Galloway, L., & Jackman, L. (2019). Gender, intersecting identities, and entrepreneurship research: An introduction to a special section on intersectionality. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1703–1705. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2019-823

- Anggadwita, G., Mulyaningsih, H. D., Ramadani, V., & Arwiyah, M. Y. (2015). Women entrepreneurship in Islamic perspective: A driver for social change. International Journal of Business and Globalisation, 15(3), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2015.071914

- Arsyianti, L. D. (2011). A study of financial planning of Indonesian family living in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Jurnal Ekonomi Islam Al-Infaq [Journal of Islamic Economics Al-Infaq], 2(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.32507/ajei.v2i2.381

- Aryaningsih, N. N., Irianto, I. K., & Masih, K. (2017). Financial management model on householder based on gender in implementing Yajna. In P. I. K. Ardhana, N. Castro, M. M. Hadj, I. M. Suwitra, A. A. G. Raka, & I. K. Irianto (Eds.), Proceedings International Conference Global Connectivity, Cross Cultural Connections, Social Inclusion, and Recognition: The Role of Social Sciences (pp. 441–449). Digital repository of Warmadema University.

- Bahtiar, B. (2021). Assessing ageist behaviors of Indonesian adult persons using the relating to older people evaluation (ROPE) survey. Jurnal Kesehatan Pasak Bumi Kalimantan, JKPBK [Journal of Health, Pasak Bumi Kalimantan, JKPBK], 4(2), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.30872/j.kes.pasmi.kal.v4i2.6782

- Barlow, C., Bellis, A., & Andrews, K. (1991). Nusa Tenggara Timur: The challenges of development. Panther Publishing.

- Brydges, T., & Hracs, B. J. (2019). What motivates millennials? How intersectionality shapes the working lives of female entrepreneurs in Canada’s fashion industry. Gender, Place & Culture, 26(4), 510–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1552558

- Cahyono, E., Syafitri, W., & Susilo, A. (2021). Ethnicity, migration, and entrepreneurship in Indonesia. Journal of Indonesian Applied Economics, 9(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jiae.2021.009.01.1

- Carrard, N., MacArthur, J., Leahy, C., Soeters, S., & Willetts, J. (2022). The water, sanitation, and hygiene gender equality measure (WASH-GEM): Conceptual foundations and domains of change. Women’s Studies International Forum, 91, 102563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2022.102563

- Cavill, S., Mott, J., Tyndale-Biscoe, P., Bond, M., Huggett, C., & Wamera, E. (2018). Engaging men and boys in sanitation and hygiene programmes – frontiers of CLTS: Innovations and insights. Institute of Development Studies.

- Cawood, S., & Rabby, M. F. (2021). ‘People don’t like the ultra-poor like me’: An intersectional approach to gender and participation in urban water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) projects in Dhaka’s bostis. International Development Planning Review, 44(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2021.7

- Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Constantinidis, C., Lebègue, T., El Abboubi, M., & Salman, N. (2019). How families shape women’s entrepreneurial success in Morocco: An intersectional study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1786–1808. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0501

- Cornwall, A., & Rivas, A.-M. (2015). From ‘gender equality’ and ‘women’s empowerment’ to global justice: Reclaiming a transformative agenda for gender and development. Third World Quarterly, 36(2), 396–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1013341

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- Dana, L. P. (2009). Religion as an explanatory variable for entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 10(2), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000009788161280

- Daniel, D., Nastiti, A., Surbakti, H. Y., & Dwipayanti, N. M. U. (2023). Access to inclusive sanitation and participation in sanitation programs for people with disabilities in Indonesia. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 4310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30586-z

- Das, M. B. (2017). The rising tide: A new look at water and gender. The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/4451f8ac-965c-563c-8268-fc86d0625d58

- Djobo, A., Liliweri, A., & Djaha, A. S. A. (2023). The role of gender in participatory policymaking: The development of Tenun Ikat industry in Ternate village Alor Barat Laut district Alor regency. International Journal of Social and Management Studies, 4(2), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.5555/ijosmas.v4i2.274

- Djoeroemana, S., Myers, B., Russell-Smith, J., Blyth, M., & Salean, I. E. T. (Eds.). (2007). Integrated rural development in east Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. In Proceedings of a Workshop to Identify Sustainable Rural Livelihoods, Held in Kupang, Indonesia, 5–7 April 2006 (pp. 1–196). Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

- Dy, A., & Agwunobi, A. J. (2019). Intersectionality and mixed methods for social context in entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1727–1747. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0498

- Grant, M., Hor, K., Bunthoeun, IV., Soeters, S. (2019a). “‘Women who have a WASH job like me are proud and honoured’: A learning paper on how women can participate in and benefit from being part of the government WASH workforce in Cambodia.” Open Publications of UTS Scholars. https://multisitestaticcontent.uts.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/57/2022/01/31084544/UTS-ISF-Gender-at-Work-Summary-brief-Cambodia.pdf

- Grant, M., Soeters, S., Bunthoeun, I., & Willetts, J. (2019b). Rural Piped-Water Enterprises in Cambodia: A Pathway to Women's Empowerment? Water 2019, 11, 2541. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11122541

- Indarti, N., Rostiani, R., Megaw, T., & Willetts, J. (2019). Women's involvement in economic opportunities in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) in Indonesia: Examining personal experiences and potential for empowerment. Development Studies Research, 6(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/21665095.2019.1604149

- Koning, J. (2011). Business, belief, and belonging: Small business owners and conversion to charismatic christianity. In M. Dieleman, J. Koning, & P. Post (Eds.), Chinese Indonesians and regime change (pp. 23–46). Brill.

- Leahy, C., Lunel, J., Grant, M., & Willetts, J. (2017). Women in WASH enterprises: Learning from female entrepreneurship in Cambodia, Indonesia and Lao PDR, Enterprise in WASH (Working Paper No. 6). https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/bitstream/10453/122061/1/Working-Paper-6_Women-in-WASH-Enterprises.pdf

- Lenka, U., & Agarwal, S. (2017). Role of women entrepreneurs and NGOs in promoting entrepreneurship: Case studies from Uttarakhand, India. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 11(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-07-2015-0088

- Mactaggart, I., Baker, S., Bambery, L., Iakavai, J., Kim, M. J., Morrison, C., Poilapa, R., Shem, J., Sheppard, P., Tanguay, J., & Wilbur, J. (2021). Water, women and disability: Using mixed-methods to support inclusive WASH programme design in Vanuatu. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific, 8, 100109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100109

- Mebrate, E. (2020). USAID transform WASH: Women as business leaders. USAID. https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/women_in_wash_business_ln_irc_final_approved_0.pdf

- Mihretu, N., & Uraguchi, Z. (2017, October 17). “He for she”: Engaging men for women’s empowerment in Ethiopia. Helvetas Blogs. https://www.helvetas.org/en/switzerland/how-you-can-help/follow-us/blog/inclusive-systems/Engaging-men-for-womens-empowerment-in-ethiopia

- Mulira, F., & Ndaba, Z. (2016). Gender and disability: An intersectionality perspective of micro-enterprise learning among women with disabilities in Uganda. Africagrowth Institute, 13(4), 14–17. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC199565

- Murta, J., Indarti, N., Rostiani, R., & Willetts, J. (2015). Motivators and barriers for water and sanitation enterprises in Indonesia, enterprise in WASH (Research report 3). Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. http://enterpriseinwash.info/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ISF-UTS_2015_Research-Report-3-Indonesia-motivators-and-barriers.pdf

- Onyx, J., & Bullen, P. (2000). Measuring social capital in five communities. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 36(1), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886300361002

- Prikardus, H. C., & Frederik, M. G. (2020). Relasi Perempuan dan Laki-laki menurut Luce Irigaray. Jurnal Harkat: Media Komunikasi Gender [Gender Communication Media], 16(2), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.15408/harkat

- Prins, B. (2006). Narrative accounts of origins: A blind spot in the intersectional approach? European Journal of Women’s Studies, 13(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506806065757

- Rafiki, A., & Nasution, F. N. (2019). Business success factors of Muslim women entrepreneurs in Indonesia. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 13(5), 584–604. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-04-2019-0034

- Rao, A., Kelleher, D., Miller, C., Sandler, J., Stuart, R., & Principe, T. (2017). Gender at work: An experiment in “doing gender”. In S. A. Tirmizim & J. D. Vogelsang (Eds.), Leading and managing in the social sector, management for professionals (pp. 155–173). Springer International Publishing.

- Rao, A., Sandler, J., Kelleher, D., & Miller, C. (2016). Gender at work: Theory and practice for 21st century organizations. Routledge.

- Rembis, M., & Djaya, H. P. (2020). Gender, disability, and access to health care in Indonesia: Perspectives from global disability studies. In K. Smith & P. Ram (Eds.), Transforming global health (pp. 97–111). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-32112-3_7

- Roomi, M. A., Rehman, S., & Henry, C. (2018). Exploring the normative context for women’s entrepreneurship in Pakistan: A critical analysis. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 10(2), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-03-2018-0019

- Rugoho, T., & Chindimba, A. (2018). Experience of female entrepreneurs with disabilities in Zimbabwe. In D. Chitakunye & A. Takhar (Eds.), Examining the role of women entrepreneurs in emerging economies (pp. 145–163). Business Science Reference.

- Salverda, T., & Abbink, J. (2013). Introduction: An anthropological perspective on elite power and the cultural politics of elites. In J. Abbink & T. Salverda (Eds.), The anthropology of elites. Power, cultures, and the complexities of distinction (pp. 1–28). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schijf, H. (2013). Researching elites: Old and new perspectives. In J. Abbink & T. Salverda (Eds.), The anthropology of elites. Power, cultures, and the complexities of distinction (pp. 29–45). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shamier, C., McKinnon, K., & Woodward, K. (2021). Social relations, gender and empowerment in economic development: Flores, Nusa Tenggara Timur. Development and Change, 52(6), 1396–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12688

- SNV. (2021). Empowering rural women entrepreneurs in WASH services in Bhutan, Lao PDR, and Nepal, practice brief – SSH4A. The Hague. https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/snv-bfl-rural-women-entrepreneurs-wash-web.pdf

- Soeters, S., Grant, M., Carrard, N., & Willetts, J. (2019). Intersectionality: Ask the other question. Water for women: Gender in WASH – conversational article 2. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wordpress.multisite.prod.uploads/wp-content/uploads/sites/57/2019/03/05175814/ISF-UTS_2019_IntersectionalityArticle2_GenderinWASH_WaterforWomen.pdf

- Soeters, S., Grant, M., Salinger, A., & Willets, J. (2020). Gender equality in water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) enterprises in Cambodia, synthesis of recent studies. Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology Sydney. https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/170406

- Soeters, S., Siscawati, M., Ratnasari, Septiani Anggriani, Nailah & Willetts, J. (2021). Gender equality in the government water, sanitation, and hygiene workforce in Indonesia: an analysis through the Gender at Work framework. Development Studies Research, 8(1), 280–293. DOI:10.1080/21665095.2021.1978300

- Stirzaker, R., & Sitko, R. (2019). The older entrepreneurial self: Intersecting identities of older women entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1748–1765. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0497

- UNICEF. (2019a). Provincial snapshot: East Nusa Tenggara. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/sites/unicef.org.indonesia/files/2019-05/NTT_ProvincialBrief.pdf

- UNICEF. (2019b). Provincial snapshot: West Nusa Tenggara. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/sites/unicef.org.indonesia/files/2019-05/West_Nusa_Tengarra_ProvincialBrief.pdf

- Usman, H., & Projo, N. W. K. (2021). Encouraging entrepreneurship for people with disabilities in Indonesia: The United Nations ‘leave no one behind’ promise. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 29, 195–206. https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv292021.012

- Vaiou, D. (2018). Intersectionality: Old and new endeavours? Gender, Place & Culture, 25(4), 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460330

- Water for Women Fund. (2021, August 23). Water for women launches “transformative trio” of GESI resources at world water week. Australian AID. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/news/water-for-women-launches-suite-of-inclusive-wash-tools-at-world-water-week.aspx

- Water for Women. (2022). Civil society engagement with the private sector for inclusive WASH: Insights from Water for Women. https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/news/civil-society-engagement-with-the-private-sector-for-inclusive-washinsights-from-water-for-women.aspx

- Willetts, J., Murta, J., & Gero, A. (2016). Water and sanitation entrepreneurs in Indonesia, Vietnam and Timor-Leste: Traits, drivers and challenges (Working Paper No. 4). http://hdl.handle.net/10453/58763

- Williams, J., & Patterson, N. (2019). New directions for entrepreneurship through a gender and disability lens. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(8), 1706–1726. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2017-0499

- World Bank. (2019). Women in water utilities: Breaking barriers. The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/61ce4696-1ea1-52f7-90b5-2a9e4f0548c5/content