ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the influence of land and property privatization processes on urban development in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), Vietnam. Many scholars have recognized that the privatization policy regarding property and land use rights may create a fragmentation of private land ownership, which eventually can lead to what has been called the tragedy of the anticommons. This paper observes how this phenomenon has also threatened urban development in HCMC after the introduction of the Doi Moi policy. Two case studies show two different types of development processes in HCMC, namely a small self-development project and a large-scale commercial project. Both case studies reveal how (potential) tragedies of the anticommons can be solved in different ways.

1. Introduction

The economic transition from a socialistic and centralized system to a more open market-oriented system is still going on in Vietnam. The transition has also affected urban land (re)development in Ho Chi Minh City – née Saigon (HCMC). As also happened in many other countries experiencing this kind of transition, Vietnam – particularly HCMC – has experienced changes from land and property privatization that reduce the government’s overload responsibilities as well as risks in land developments and enable it to benefit from capitalizing on land use rights by attaching more value to land (Tsenkova, Citation2012). Before the transition, land in Vietnam was underutilized and not considered a resource with real value (Kim, Citation2009).

Although privatization can lead to a more economical use of natural resources (including land) and is generally considered a desirable step in pushing the evolution of an area along (De Soto, Citation2001; Loehr, Citation2012b; Sjaastad & Cousins, Citation2009), it can also bring forward new issues related to land development processes. One such issue – that has also been experienced by other transitional countries (Loehr, Citation2012a) – is the existence of ambiguous and fragmented property rights over land or properties, which in the long run could eventually cause a counterproductive effect, namely the underuse of land resources. Heller (Citation1998) has referred to this issue as the tragedy of the anticommons, in which fragmented ownership leads to diminishing prosperity. Anticommons property can be understood as the mirror image of commons property and the related tragedy of the commons (Hardin, Citation1968) (see Section 2).

As later on argued by Heller (Citation2013), the anticommons theory may seem well-established, but it still requires more empirical studies and evidence. We explored two case studies in HCMC that show two different types of private-led development processes: a small-scale residential development project and a large-scale foreign investment project. This paper aims to observe the impact of the privatization of land and property development in HCMC on the occurrence of the anticommons phenomenon and the way private investors respond. The results of this study may contribute both in offering empirical evidence of the anticommons phenomenon and in providing a better understanding of the consequences of changing land and property rights in transition economies, particularly in HCMC. This research also aims to contribute to recent debates in Vietnam about the involvement of the Central Government in real estate development (Ha, Citation2013).

The contents of this paper are structured as follows. Section 2 outlines the privatization of property rights and land development in transitional economies. Section 3 discusses the phenomenon of the tragedy of the anticommons in general. Section 4 provides a brief explanation of land privatization in Vietnam and HCMC in particular. In Section 5 two case studies from HCMC urban development processes are described, followed by a general discussion of the results in Section 6. Finally, some conclusions are drawn in Section 7.

2. Privatization of property rights and land development in transitional economies

A property right can be seen as the exclusive authority used to determine how a resource is managed, whether a government, collective bodies, or individuals own that resource (Aichian & Demsetz, Citation1973). In many countries that are in transition from a public-led system to a more market-led system, the issue of individual property rights has become a subject of debate. As argued by some scholars, the existence of individual property rights plays an important role in decision-making to increase investments and the use of a resource, which can explain the differences in economic behaviour and performance between the public-led and market-led economic systems (see e.g. Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Libecap, Citation1986). Concerning urban land and property development, the significance of a property rights regime securing individual property rights has received attention in recent decades. The International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization and other governmental development organizations have adopted what is called the capitalization by formalization agenda (Loehr, Citation2012a). This agenda is strongly influenced – particularly in developing countries – by the work of De Soto (Citation2001). Various scholars have stated that secure individual property rights over land may affect urban development in at least three different ways. First, it can enhance investment incentives by limiting the risk of expropriation and by reducing the need to divert private resources to protect property rights (Kapeliushnikov, Kuznetsov, Demina, & Kuznetsova, Citation2013). Second, well-defined property rights over land can facilitate the transfer of assets and assists in the efficient allocation of land resources (Besley, Citation1995; Galiani & Schargrodsky, Citation2010). Third, formal rights over land can improve the ability of landowners to use land as collateral, increasing landowner access to credit markets (De Soto, Citation2001).

In many transitional countries, the endorsement of individual property rights in land privatization processes takes place as part of a broader land reform policy. The goal of land privatization is mainly to improve livelihood opportunities and to enhance access to land (May & Lahiff, Citation2007). However, two (related) problems may arise as a consequence of this privatization process. First, not all transitional countries provide full ownership rights to individuals or private entities in land, nor do they sufficiently add to the ownership of rights the obligation to contribute to community costs (e.g. infrastructure). After privatization processes are enacted, some restrictions for individuals to use the land may remain, such as in China, Russia, Mongolia, Cambodia and Vietnam. The new property rights regime may lead to the occurrence of ambiguous property rights (see e.g. Bagdai & Tsolmon, Citation2009). Under ambiguous property rights, the owner’s control over his/her resource is not guaranteed; that is, pre-agreed and binding rules regarding who will be in control in various ex post contingencies are absent (Li, Citation1996). As shown by Bagdai, van der Molen, and Tuladhar (Citation2012) in the case of Russia, the restrictions for individuals to use the land are aggravated by the lack of access to land information and inefficient land administration systems. Li (Citation1996) and Jieming (Citation2002) have observed problems with ambiguous property rights in China, while (Loehr, Citation2012a, Citation2012b) refers to the same phenomenon in Cambodia. Li (Citation1996) argues that ambiguous property rights lead to high transaction costs and increased uncertainties in the market place. Interestingly, however, Jieming (Citation2002) and Li (Citation1996) also show that despite the ambiguity of property rights, the private sector – particularly in China – can still be successful. Apparently, the ambiguous allocation of property rights over urban land has created opportunities in the development process for various actors who have been able to capture resources that have been left in the public domain. Loehr (Citation2012b) points to a different issue: ‘in contrast to the viewpoint of the property rights theorists, private property in land may also result in a decoupling of benefits and costs of land use’ (p. 776). The owners of ambiguous property rights sometimes receive all the benefits from the ownership of these rights, but do not contribute to public costs.

Secondly, privatization of property rights often contributes to the fragmentation of these rights in existing urban areas, which may act as an institutional barrier to sustainable transformation processes (Zhu, Citation2012). These two (related) problems, in fact, demonstrate the possibility of the tragedy of the anticommons.

3. The tragedy of the commons and the anticommons

Before we discuss the tragedy of the anticommons, it is useful to explain its mirror image, the tragedy of the commons, which has been more widely known and grounded in mainstream scholarly debates. The term ‘the tragedy of the commons’ was introduced by Hardin (Citation1968) to explain the relations between human population growth, the use of the Earth’s natural resources, and the state welfare system. The tragedy of the commons is a situation in which resources are over-utilized by excessive usage of different agents under open access of the resources to all potential users. Eventually, this overuse will reduce the value of the resource to the users themselves (Buchanan & Yoon, Citation2000). Hardin has referred to this as a tragedy because in this situation all individual users are expected to act for short-term individual benefits despite the long-term collective loss as a result of the overuse.

The concept of the tragedy of the commons is helpful to explain why people overuse shared resources (Barnett, Citation2010; Lin, Citation2012; Sturges, Citation2011). In 1998, Heller (Citation1998) examined a mirror situation of the tragedy of the commons in which resources are underutilized rather than over-utilized, which he called the Tragedy of the Anticommons. Heller (Citation1998) defines the tragedy of the anticommons as follows:

In an anticommons (p. 624) multiple owners are each endowed with the right to exclude others from a scarce resource, and no one has an effective privilege of use. When there are too many owners holding rights of exclusion, the resource is prone to underuse – a tragedy of the anticommons.

The problem of anticommons is mainly caused by the inefficient division of property among multiple individuals (Heller, Citation1998). The perceived transaction and strategic cost of consolidating the property among those individuals is greater than the increased values that are expected from the reunification of those properties. Heller developed his theory after observing the situation in Moscow in the 1990s, where he noted that many storefronts were empty while the street kiosks in front were full of goods. The tragedy of the anticommons can also be observed in the case of fragmented land ownership in a particular urban area, especially when each landowner would prevent others from developing the land resource. This situation will eventually create a hold out or stalled-development problem. According to Heller (Citation1998), this is a type of coordination breakdown in which a single resource has various rights holders, and no one has sufficient privilege of use. The anticommons tragedy would therefore emerge when initial endowments are created as disaggregated rights rather than as combined bundles of rights over scarce resources. This problem can appear whenever governments create new property rights. Heller (Citation1998) also argued that although the initial endowment of property rights was clearly defined, the tragedy of the anticommons might remain, especially when there are ambiguous property rights in which the government is still a right-holder along with the rights that are given to private individuals.

Eminent domain is often used as a way to solve the problems of the tragedy of the anticommons on land and property markets (Buchanan & Yoon, Citation2000; Loehr, Citation2011, Citation2012b; Sim, Lum, & Malone-Lee, Citation2002; Zhu, Citation2012). Heller (Citation1998) specifically called for an intervention of the central government in such cases, for instance by abolishing the rights that were previously granted, eliminating lower levels of government or by expropriating the existing rights. In Vietnam, and particularly in HCMC, problems of the anticommons have also occurred. Though we have no exact data that show how often these problems occur, the substantial amount of stalled developments can be used to indicate that it is a serious issue in HCMC’s land and property development. In 2014, the HCMC Department of Construction listed around 536 housing and commercial development projects that were stalled, covering a total area of over 5397 ha of land. As explained by the HCMC Department of Construction, the delays in these projects, on the one hand, seem to be caused mainly by lack of public funding and planning procedures, and on the other hand problems with clearing the land due to fragmented property rights that can be related to the tragedy of the anticommons. The present study will demonstrate through two different case studies how tragedy of the anticommons-like problems have occurred in the land and property market in HCMC and how the related stakeholders have dealt with these problems. However, before we explore these two case studies, we will first pay attention to the privatization processes, with respect to land and property in Vietnam, that have occurred since the introduction of the Doi Moi policy.

4. Land and property privatization in Vietnam

In 1986, the Vietnamese central government started economic reform by introducing the Doi Moi policy. It marked the beginning of Vietnam’s economic transition from a socialist-centralistic system to a more market-oriented one. The change also affected land and property in Vietnam with the introduction of a new land law in 1988 that permitted the grant of land use rights to organizational and individual land-users while still affirming that only the state – in the name of all citizens – is the sole administrator of the land. However, it was not until 1993 that the land market in Vietnam began to change when another new land law was introduced that gave wider land use rights to private parties. The individual rights included the right to transfer, exchange, lease, inherit and mortgage property. Soon after the introduction of this 1993 land law, many new commercial as well as residential developments (also redevelopments) emerged. Individuals in Vietnam were now able to secure long-term land use rights that were almost similar to full ownership (Tuyen, Citation2010).

After several revisions and further changes in land laws, the latest update of the Vietnamese Land Law took place in 2013. This 2013 Land Law contains some improvements with respect to land transactions and land prices. It regulates the procedures for both the state and private sector to take decisions on land acquisitions and upgrades the rights of foreign investors.Footnote1 Currently 100% of foreign-owned investment is possible in Vietnam, although joint ventures between foreign and local companies are still very common. For foreign companies, cooperation with Vietnamese companies (which can be both state-owned or fully private) usually makes land acquisition and procedures easier (Thao, Citation2013).

Another important regulation related to property was introduced in 1994 in Vietnam. It was Decree 61/1994/NĐ-CP, which proclaimed that the municipality wanted to sell all state-owned houses to their existing tenants. Under this regulation, large numbers of old houses were transferred to the current users at a subsidized price. It was much lower than the market price to reward them for their engagement in the war. Most of the buyers were war veterans and government officers. Particularly in HCMC, up to 2013, the city authority had sold around 97,000 houses under this regulation, but it still aims to sell another 13,000 houses. In 2013, this regulation was replaced by Decree 34/2013/NĐ-CP, which stated that the new price would be closer to market prices, and a user could buy two or three state houses instead of only one.

5. The tragedy of the anticommons in land and property development: two case studies from HCMC

In general, land development in HCMC can be categorized into two different types: small, individual projects by the owner-user, and large-scale projects by real estate developers. The amount of each type of development can be derived from the number of construction permits that were issued by the HCMC Department of Planning and Architecture (). According to the Vice-Director of the Department, most of the capital for the high-rises or large residential projects comes from foreign funds, either direct or indirectly.

Table 1. Building permits in HCMC in 2001–2014.

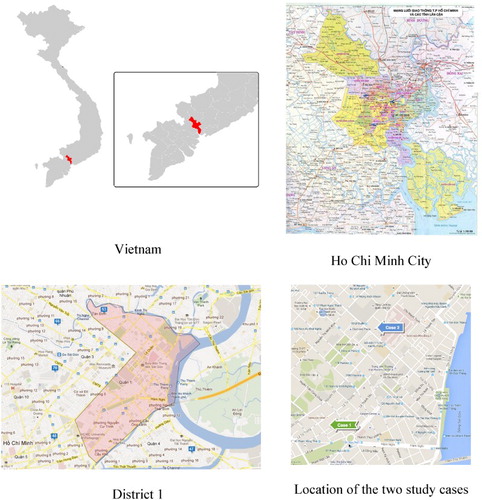

In this section, two case studies in District 1, HCMC () will be presented: one case for each type of development mentioned above. The basic profiles of these two case studies are shown in .

Table 2. Profiles of two projects.

This study is based on both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected from on-site observations and interviews with principal informants during field research conducted for a period of six months from 2011 to 2012. There were 17 interviews with 6 real estate experts (developers, academics and researchers); 9 government officers at the HCMC Department of Planning and Architecture, Department of Investment, Institute for Development Studies and Real Estate Association; as well as two individual homeowners who were involved in the cases. The secondary data were gathered from the HCMC Department of Architecture and Planning as well as documents and paperwork related to the projects owned by the interviewees in the case studies. The officers and homeowners provided inside stories about the projects. This paper uses the primary and secondary data to form independent opinions about the cases, which do not necessarily represent the opinions of the interviewees.

5.1. Case study 1: 240 Le Thanh Ton street building

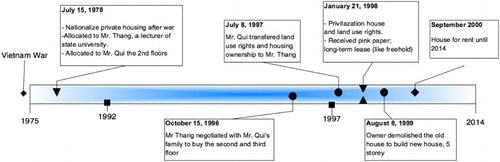

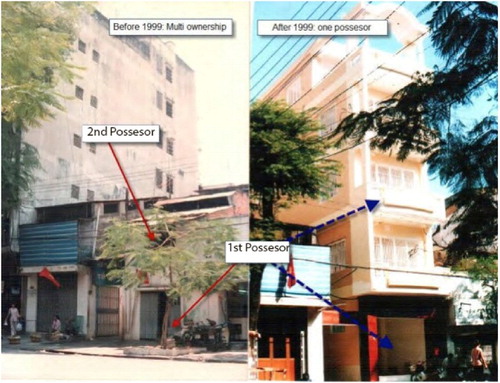

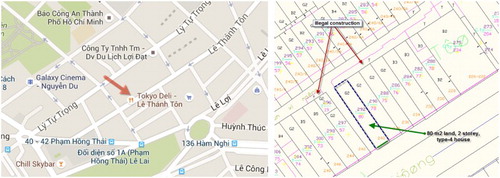

The first case study concerns a redevelopment project in a small residential apartment block located at 240 Le Thanh Ton St., District 1, downtown HCMC and close to the historic Ben Thanh Market (). The apartment block was first built in the 1940s as a two-storey residential building. During the Vietnam War (1954–1975), an Indian national owned the property and let the building to a Chinese family. The tenant, in turn, sublet part of the building to a hairdresser shop. After HCMC – which was still called Saigon at that time – became part of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam on 30 April 1975, the Indian owner went to his homeland and relinquished his ownership of the property. Along with that, the Chinese tenant and the owner of the hairdresser shop also left the country because of the difficult political and economic situation at that time. Consequently, the building was vacant and unoccupied until it was taken over by the State on 22 September 1975 as part of a national programme to nationalize empty houses in the city after the war from 1955 to 1975 between the USA and Vietnam. Later on, those empty houses were handed over to the city government. On 19 September 1978, the city government officially issued a certificate for the building at 240 Le Thanh Ton St. to be used by the HCMC University of Architecture for its employees. According to this decision, the Housing Management Company of HCMC had the rights to make a rental contract and collect rent from the users of the building. The property changed hands and was redeveloped for commercial use ().

Figure 2. Location of the first case study. Source: Ho Chi Minh City Department of Planning and Architecture (2002).

On 5 October 1978, the HCMC University of Architecture made a decision to allocate the house to two of its lecturers and their families: one professor (user 1) and his family occupied the ground floor, and the other (user 2) occupied the first and second floor. Each household paid 11.2 VND monthly (out of an average salary of 80 VND/month in the 1970–1980s) for rent.

With the state as the sole owner of the land and the building, maintenance and upgrades of the building also depended on the State. For almost 20 years, the State did not make any significant maintenance or renovations to the building. As a result, the quality of the building had deteriorated, as did most of the other state house rentals in the city.

After the introduction of Decree 61/1994/NĐ-CP about the selling of state houses, user 1 intended to buy the building to upgrade it. User 2, however, was not interested in doing this. In 1997, user 1 made an informal agreement with user 2 that if the municipality transferred the ownership of the building to both of them, user 2 would agree to sell his ownership rights to user 1. With that agreement in place, both users submitted an application later that year to purchase the building. The HCMC Municipality, through the Housing Business Company of District 1, agreed to sell the right to use the building based on a long-term ‘eternal’ lease to each of the two existing tenants. According to the contracts of the sale (7*9/97/HD-MBNO-1 and 2*0/97/HD-MBNO) dated 30 December 1997, each buyer was required to pay US$40,000, which, according to user 1 in an interview, was around 50% lower than the market price at that time for the following items:

The house (2 stories and very low quality construction).

The land use rights.

This transaction, however, did not include ownership of the land, which still belonged to the State.

Since only user 1 was interested in buying the building, user 1 paid US$80,000 to the State both for his and user 2’s land use rights and housing ownership. On 1 April 1998, the HCMC municipality decided to issue two land use rights and housing ownership certificates for the building: one to user 1 and one to user 2. With this decision, user 2 obtained the rights without paying, and he retained legal ownership of the first and second floor, including the rights to build on top of it (air rights). As previously agreed, user 1 had to buy user 2’s rights to obtain full ownership of the property. User 1 then paid user 2 another US$40,000 and completed the old contract in January 1998, which was before the contract with the HCMC municipality was made. This process meant that the property was transferred from State ownership into a single private ownership via a multi-private ownership, with a US$120,000 investment by user 1 (around |US$1500/m2). By doing this, user 1 obtained the rights to redevelop the whole building and the rights that enabled him to make profit from it.

After user 2 left the house, user 1 – as the sole holder of the use rights of the building – asked the municipality for permission to change the function of the property from residential to commercial. It is a compulsory process to enable the building to be rented by foreigners.Footnote2 On 13 July 1998, the owner was granted permission to let the house to foreigners (Certificate #2*1/GPCT.DB). Also in the same year, user 1 applied for another permission to demolish the old two-storey building and to build a new five-story building. Permission was granted (Certificate # 21*/GPXD) soon afterwards, and the new building was completed one year later ().

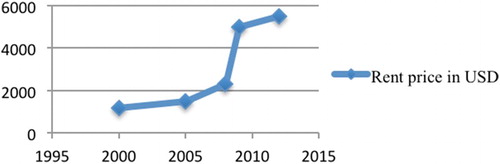

The first lease went to a Taiwanese merchant, who rented the building for the price of |US$1200/month. A few years later, both the value of the new commercial building and its rent had tripled. In 1997, before the purchase from the state, the building was valued approximately at US$150,000; this increased to US$1 million in 2003 and US$2.5 million in 2013. Within two years after the completion of the project (2000), the investment costs were recovered, and it started to make a profit. The rental price has continued to increase since 2000 (). From 2009 up until now, the whole building has been let to a Japanese Restaurant () for a rent of US$5500/month (2015). The owner pays a city income tax of 18% from the monthly rental income. Compared with the earnings gained during the pre-privatization period, both the developer and the government have thus seen their income from the building increase substantially.

5.2. Case study 2: Kumho Plaza, 39 Le Duan Boulevard

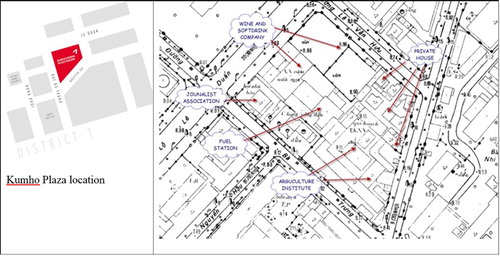

The second case study is the development of a large-scale foreign investment project at 39 Le Duan Boulevard, also known as Kumho Asiana Plaza. The total project covered an area of 13,632 m2, and the location is surrounded by four streets: Le Duan Boulevard, Hai Ba Trung Street, Nguyen Du Street and Le Van Huu Street (). The whole block was in use by several buildings for different activities, including: residential use for mostly government officers, some office buildings in use by both government and non-government organizations, as well as some small commercial activities ().

Figure 7. The previous land use structure of case study 2. Source: Ho Chi Minh City Department of Planning and Architecture (1988).

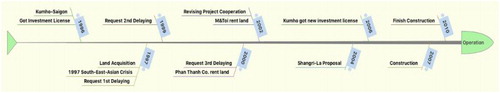

After the introduction of the 1993 Land Law, many private real estate developers – both domestic and foreign – took the chance to invest in the Vietnamese land development, particularly in HCMC.Footnote3 Some foreign investors expressed their interest to develop the whole block at 39 Le Duan Boulevard because of its strategic location in the heart of the city centre. It took 14 years for Kumho E&C to develop the project ().

In June 1996, the joint venture company Kumho-Saigon gained approval from the Ministry of Planning and Investment (MPI) to operate the development of the block with an investment up to US$225 million. The joint venture consisted of three companies: Saigon Tourist (SGT), Housing Development & Service of District 1 (SHD.D1) – the two of them were the original owners of the property – and the Kumho Construction & Engineering Inc. Kumho C&E is a Korean construction and real estate company and member of a large, internationally well-known conglomerate, the Kumho Asiana Group. Kumho contributed 65% of the capital, while the remaining 35% came from the Vietnamese parties, SGT and SHD.D1. The investment share of the two Vietnamese companies was equal to the value of the land they already owned on the block. The operation period of the land lease was 45 years from the date issued on the license, with a land rent paid of US$13.6/m2 per year. After 45 years, the local authority would give the existing users priority to apply for an extension of the land use rights.

The planned development included a luxury hotel, a conference centre, offices, high-class apartments, a restaurant, and entertainment with a total investment of US$150 million. In 1996, Kumho contributed US$15.2 million to the joint venture company for the first stage of the project to be used for land acquisition (compensation paid to families living at that location) and site clearance. Kumho also promised the HCMC authorities to donate US$1 million to the public infrastructure investment fund of the city.

The Asian financial crisis occurred in 1997, and many big companies were heavily affected, including Kumho. On 18 June 1997, the joint venture company, Kumho-Saigon officially requested postponement of the deployment of the project. In response, the Ministry of Planning & Investment and other state agencies approved the request to restart the project by the year 2000 at the latest. However, Kumho still had financial problems in 2000 and asked to postpone the project again. The request was again approved by the State. A new deadline for Kumho-Saigon to start the project was set for September 2002. In order to minimize the inefficient use of the cleared site of the block in the interim period, the Vietnamese partners leased the land to Phan Thanh LTD. Co. to develop a temporary shopping centre from simple construction that was called the Saigon Square in 2000. Later, in 2002, the M & Toi music café also rented a part of the area ().

Figure 9. The Saigon square and M & TOI music café. Source: Đức (Citation2005).

In mid-2002, SGT – one of the two local partners in the joint venture – put forward a proposal to purchase Kumho’s share in the joint venture with support from the HCMC municipality. The main reason for this proposal was that both the domestic partners and the city were worried about Kumho’s capability to invest. The municipality had become impatient with the delays of the project and wanted to put the land into operation as quickly as possible. The municipality therefore supported the idea to replace Kumho as the foreign partner in the project, but promised Kumho that the municipality would secure Kumho’s involvement in another development projects in the future if Kumho would agree to the proposal. Moreover, as confirmed by an officer from the HCMC Department of Investment during an interview, Shangri-La Asia, a well-known Hong Kong-based hotel chain company, knew about the financial issues that Kumho faced and asked the domestic partners to be substituted for Kumho.

Kumho decided to offer its share to SGT for a price of US$13.6 million, but SGT agreed to pay only US$10.3 million, which was equal to the actual costs for the land acquisition that had been spent earlier. At that time, Kumho was in a weak position because according to the agreement between Kumho and the MPI, property rights over the land would be revoked if the development did not start by the given deadline. Kumho then responded to SGT’s proposal by stating that it would agree to the price, but under two conditions. First, the Vietnamese partners would not transfer the project to any other investor. Second, the Vietnamese partners would have to continue with the project by themselves under the name and the design of the original Kumho Project.

On 12 December 2003, the HCMC municipality received an official dispatch (Number 63*/CV-TCT) from the Vietnamese partners stating that Kumho agreed to transfer its share for a price of US$10.3 million. However, this was objected by Kumho. They claimed that the decision had to be made by the Prime Minister of Vietnam, together with the MPI, and not by the HCMC municipality, because it was the Prime Minister, through the MPI, who had approved the investment license.Footnote4 The project was not definitively terminated although the deadline to deploy the project had been passed for quite some time. As a result, the land was not optimally used during that time.

In 2005, the dispute was finally resolved. The Prime Minister of Vietnam issued a final decision to overrule the inclination of the Vietnamese partners in the Kumho-Saigon joint venture company and the HCMC municipality to replace Kumho by another foreign investor in the joint venture. The Prime Minister decided that Kumho Construction & Engineering Inc. was allowed to continue to participate in the joint venture and to carry out the development project. The local partners sold their share of the joint project. Kumho paid US$38,852,800 to obtain ownership of the whole project (creating 100% of the ownership by a foreign company). This step enabled Kumho to capture most of the positive value created by the investment project, though Kumho lost 10 years of its long-lease contract (). Construction started a year later and was completed in 2010. Since it first opened in 2010, the market in HCMC has been continuously splendid for business, including for the Kumho Asiana Plaza. In 2013 it had an occupancy rate of 98% (Colliers-International, Citation2013). Despite all its difficulties, in the end, the development of the Kumho Asiana Plaza has become a successful project ().

Figure 10. The Kumho Asiana Plaza: offices, apartments, the InterContinental Asiana Saigon hotel and residences. Source: https://c1.staticflickr.com/5/4056/4652668334_1ba967fea5.jpg.

6. Discussion

The dynamic of the private sector has created spontaneous development throughout the history of HCMC (Huynh & Peiser, Citation2015). Private developers were able – in different ways – to capture part of the rising real estate values during the transition period. The case studies above provide an inside story of how the stakeholders have been able to overcome a potential tragedy of the anticommons. In this section, the lesson learnt based on both case studies will be discussed, together with some suggestions for policy implications about possible tragedies of the anticommons in Vietnam.

6.1. Lesson learnt

Both case studies display examples of a (potential) tragedy of anticommons in HCMC, Vietnam, and the way the owners were able to actually prevent such tragedies. In the first case study, in the beginning the anticommons problem occurred because of the existence of ambiguous property rights. Before the 1993 Land Law and the announcement of Decree 61/1994/NĐ-CP, most households, especially those who lived in a state-owned house, did not have full control over their property. This was also the case for the occupants at 240 Le Thanh Ton Street after the Vietnam War. The situation prevented the users from upgrading the building and created inefficient use of the building, that is, a tragedy of the anticommons. The problem was solved when the rights over the building were more clearly defined with the introduction of the 1993 Land Law, and later on Decree 61/1994/NĐ-CP. However, if user 2 in case study 1 would have declined to sell his rights over the building to user 1, the intentions of user 1 to upgrade the building could still have been frustrating.

In the second case study, ambiguous property rights also created a tragedy of the anticommons over a period of 10 years. The disagreements between the foreign and domestic partners over the transfer of rights, as well as the unclear rights arrangement among firms, the municipality and the national government, further delayed the project and led to a situation in which the land was sub-optimally utilized. The Vietnamese central government in the current transition era still does not endow any individual or local authority with a bundle of rights that represents full control of land. This situation was used by Kumho to keep the land and stay in business by involving the national government in the dispute with its local partners in the joint venture and the HCMC municipality.

According to Heller (Citation1998), a tragedy of anticommons can be resolved through intervention by a central government: for instance, by abolishing the rights that were previously granted, eliminating lower levels of government, or expropriating the existing rights. Unlike Heller’s approach, Li (Citation1996) argued that a partnership with the authority in a development project could resolve a tragedy of the anticommons, although this will increase the ambiguity of property rights.

In case study 1, neither of those solutions was used to solve the problem. User 1 strategically used an informal negotiation with user 2 to purchase the contiguous and yet fragmented rights over the building before attempting to obtain the necessary approvals from the authority to buy the rights. The advantage of this strategy is that the informal agreement with user 2 minimized the chance of a hold out. Surely, there was the risk of having to buy out user 2’s rights twice. Nevertheless, user 1′s expectation of the future property market eventually paid off. From this case study, we can draw a lesson that even if an ambiguity of property rights still exists, the possibility to transfer property rights between public and private parties, as well as between private parties, can enable the parties to overcome a tragedy of the anticommons. Another important lesson is that strategic speculation over the expected value resulting from the investment can be considered the core of the successful transfer of property rights.

Case study 2 reveals how the Chinese example of using the positive effect of ambiguous property rights (as explained by Li (Citation1996)) also appeared in Vietnam. Unlike Li’s example, however, the government did not seek to be involved as partner or co-owner in the project. Both the domestic and foreign partners in the Kumho-Saigon joint venture tried to link authority only as far as to support their claims over the land. While the local partners found their support from the municipality, Kumho strategically attempted to get support from the national government by involving the Prime Minister and the MPI to solve the dispute. This eventually enabled Kumho to continue with the development.

6.2. Policy implications

To implement successful policies to avoid potential anticommons problems, it is important to understand the nature of anticommons in a particular context. Based on the context of the two case studies in this research, both ambiguous property rights (where there are various rights over land resources with uncertainty to control the resource) and the high cost of consolidating the exclusionary rights are the main cause of the tragedy of the anticommons. Inefficiency persists in the tragedy of the anticommons because the cost of strengthening the full rights of each owner of a parcel of land is greater than the increased rents the unification of the parcels is expected to generate (Buchanan & Yoon, Citation2000). In order to overcome this problem, involved parties may consider taking the risk to cover the cost of consolidating the exclusionary rights. In case study 1, it was user 1 who took the risk to cover the cost by buying the rights. In case study 2, Kumho took the risk to stay in business and faced with high transaction costs due to the length of the negotiation process, which made it lost 10 years of its long-lease contract.

Another important element is the fact that exclusionary rights can only be consolidated when the rights are fully transferable. From case study 1, it was apparent that transferable development rights were part of the solution for the tragedy of the anticommons. Due to the introduction of the 1993 Land Law and Decree 61/1994/NĐ-CP, the right to use and develop the building was transferred from the state to a private entity, and also from one private entity to another. By paying user 2 extra money, with an expectation of high rent values after the redevelopment of the property, user 1 was able not only to transfer the rights from the municipality to the tenants, but also from user 2 to user 1. In case study 2, however, the municipality and the two domestic partners in the joint venture company could not force Kumho to transfer its rights. The price Kumho asked for its rights was considered too high by the municipality and the domestic partners. This fact further delayed the development and intensified the tragedy of the anticommons, while Kumho adequately captured the development values (despite some losses because of the delay of the development).

In the context of land and property development in HCMC, several policy implications can be considered to overcome the potential tragedy of the anticommons. First, regulatory reform can simplify and also handle the enforcement of land use regulations. At the very least, the discretion that regulatory agencies have in enforcing land use regulations should be minimized. As in many countries with transitional economies, coordination and authority between state and local governments to enforce land use regulations is still unclear in Vietnam. To completely replace the current system of land use regulation might not be a plausible short-term solution. However, clarity to enforce a rule that has been made is obviously something that can be done before long to reform the system. Another policy implication that can be considered to mitigate the tragedy of the anticommons, particularly in the case of HCMC, is to engage further in the use of transferable development rights. The successful transfer of development rights might be related to the expected values of the development in an open market. Transparency in land and property values is crucial for the creation of such a market. Public authorities should promote and support this transparency.

7. Conclusions

This article has discussed the privatization of property rights in land and property markets in Vietnam. Privatization has unlocked property values and created new opportunities for land and property development, which has attracted both domestic and foreign investments (Yip & Tran, Citation2015). However, the reforms have created problems as well. One of them is the tragedy of the anticommons. Some have warned against the approach of formalization and capitalization – because of the tragedy of the anticommons phenomenon – and have suggested a reframing of development policy (Loehr, Citation2012a). The present study argues neither in favour nor against the formalization and capitalization processes, but rather provides some evidence of how property owners in situations of ambiguous property rights have been able to avoid anticommons tragedies by way of informal negotiations with other owners.

The results of the present study contribute empirical evidence of the tragedy of the anticommons in Vietnam to existing anticommons literature and provide a better understanding of the consequences of changing land and property rights in Vietnam, particularly in HCMC. Nonetheless, this investigation also contains limitations. First of all, it only shows two cases while there are some evidence indicating that many more of these cases can be found in HCMC (which was also mentioned in this study). Although those two cases somehow represent typical examples of land and property development in HCMC, every single case is unique and one cannot just generalize the results of this study. Nevertheless, the lessons learnt and suggested policy implications from the case studies can probably be extended to land and property development not only in HCMC, but also through greater Vietnam.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this paper is available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2016.1209122

A Curious Case of Property Privatization

Download MP4 Video (221 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCiD

Thanh Bao Nguyen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8703-7372

Erwin Van de Krabben http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2566-890X

D. Ary A. Samsura http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9512-9592

Notes

1 See Nguyen, van der Krabben, and Samsura (Citation2014) for more information about institutional change related to land and property development in Vietnam.

2 Before 2000, the owner of a property still needed a license to let the building to a foreign user. This regulation has been cancelled.

3 According to the law at that time, a foreign company had to establish a joint venture with a domestic company in order to make an investment in Vietnam.

4 According to Vietnamese Law, all projects with a capital investment of US$75 million or more must be approved by the Prime Minister.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty (1st ed.). New York, NY: Crown.

- Aichian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. (1973). The property right paradigm. The Journal of Economic History, 33(1), 16–27. doi: 10.1017/S0022050700076403

- Bagdai, N., van der Molen, P., & Tuladhar, A. (2012). Does uncertainty exist where transparency is missing? Land privatisation in Mongolia. Land Use Policy, 29(4), 798–804. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.12.006

- Bagdai, N., & Tsolmon, R. (2009, October 19–22). Land privatization practices in different Countries. Paper presented at the 7th FIG Working Regional Conference Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Barnett, J. M. (2010). The illusion of the commons. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 25(4), 1751–1816.

- Besley, T. (1995). Property rights and investment incentives: Theory and evidence from Ghana. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 903–937. doi:10.2307/2138750

- Buchanan, J. M., & Yoon, Y. J. (2000). Symmetric tragedies; commons and anticommons. Journal of Law and Economics, 43(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1086/467445

- Colliers-International. (2013). Ho Chi Minh City CBD Market Report. Ho Chi Minh City.

- De Soto, H. (2001). Why capitalism works in the West but not elsewhere. International Herald Tribune.

- Đức, T. (2005, July 26). Những uẩn khúc sau dự án Kumho Sài Gòn, Dân trí. Retrieved from http://dantri.com.vn/xa-hoi/nhung-uan-khuc-sau-du-an-kumho-sai-gon-1122353728.htm.

- Galiani, S., & Schargrodsky, E. (2010). Property rights for the poor: Effects of land titling. Journal of Public Economics, 94(9–10), 700–729. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.06.002

- Ha, S. K. (2013). Housing markets and government intervention in East Asian countries. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 17(1), 32–45. doi:10.1080/12265934.2013.777513

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248. doi:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

- Heller, M. (2013). The tragedy of the anticommons: A concise introduction and Lexicon. The Modern Law Review, 76(1), 6–25. doi:10.1111/1468-2230.12000

- Heller, M. A. (1998). The tragedy of the anticommons: Property in the transition from Marx to markets. Harvard Law Review, 111(3), 621–688. doi: 10.2307/1342203

- Huynh, D., & Peiser, R. (2015). From spontaneous to planned urban development and quality of life: The case of Ho Chi Minh City. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1–21. doi:10.1007/s11482-015-9442-7

- Jieming, Z. (2002). Urban development under ambiguous property rights: A case of China’s transition economy. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26(1), 41–57. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00362

- Kapeliushnikov, R., Kuznetsov, A., Demina, N., & Kuznetsova, O. (2013). Threats to security of property rights in a transition economy: An empirical perspective. Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(1), 245–264. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2012.05.002

- Kim, A. M. (2009). Land takings in the private interest: Comparisons of urban land development controversies in the United States, China, and Vietnam. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 11(1), 19–31.

- Li, D. D. (1996). A theory of ambiguous property rights in transition economies: The case of the Chinese Non-State sector. Journal of Comparative Economics, 23(1), 1–19. doi:10.1006/jcec.1996.0040

- Libecap, G. D. (1986). Property rights in economic history: Implications for research. Explorations in Economic History, 23, 227–252. doi: 10.1016/0014-4983(86)90004-5

- Lin, G. C. S. (2012). “The tragedy of the commons”? Urban land development in China under marketization and globalization. https://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/dl/2224_1556_Lin_WP13GL1.pdf.

- Loehr, D. (2011). Land reforms and the tragedy of anticommons. Paper presented at the 1st World Sustainability Forum.

- Loehr, D. (2012a). Capitalization by formalization? Challenging the current paradigm of land reforms. Land Use Policy, 29(4), 837–845. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.01.001

- Loehr, D. (2012b). Land reforms and the tragedy of the anticommons-A case study from Cambodia. Sustainability. doi:10.3390/su4040773

- May, H., & Lahiff, E. (2007). Land reform in Namaqualand, 1994–2005: A review. Journal of Arid Environments, 70(4), 782–798. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2006.08.015

- Nguyen, T. B., van der Krabben, E., & Samsura, D. A. A. (2014). Commercial real estate investment in Ho Chi Minh City – A level playing field for foreign and domestic investors? Habitat International, 44, 412–421. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.08.002

- Sim, L. L., Lum, S. K., & Malone-Lee, L. C. (2002). Property rights, collective sales and government intervention: Averting a tragedy of the anticommons. Habitat International, 26(4), 457–470. doi:10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00021-8

- Sjaastad, E., & Cousins, B. (2009). Formalisation of land rights in the South: An overview. Land Use Policy, 26(1), 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.05.004

- Sturges, M. (2011). Enclosing the commons. Virginia Magazine of History & Biography, 119(1), 44–74.

- Thao, B. T. H. (2013). Analysis of the Vietnamese commercial real estate market strategic investment implications for evergreen properties of Michigan, Inc. (Bachelor). Lahti: Lahti University of Applied Sciences.

- Tsenkova, S. (2012). Private sector housing management: Post-socialist. In J. S. Susan (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of housing and home (pp. 420–426). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

- Tuyen, N. Q. (2010). Land law reforms in Vietnam – past & present. Asian Law Institute, National University of Singapore: Singapore.

- Yip, N. M., & Tran, H. A. (2015). Is ‘gentrification’ an analytically useful concept for Vietnam? A case study of Hanoi. Urban Studies. doi:10.1177/0042098014566364

- Zhu, J. (2012). Development of sustainable urban forms for high-density low-income Asian Countries: The case of Vietnam: The institutional hindrance of the commons and anticommons. Cities, 29(2), 77–87. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2011.08.005