ABSTRACT

Smart city development can be traced back in the urban development trajectories of cities, as well as the respective articulations, framing and practices of ‘inclusive’ and ‘participatory’ smart cities. As smart city development steadily gains more and more traction among urban policy makers throughout the Global South, many scholars warn for its negative consequences on the accessibility of infrastructure and the processes that transform democratic citizenship practices. Rather than perceiving the transformative power of smart cities as a phenomenon particular to the use of new technologies, this paper aims to analyse societal segregation and marginalization through smart city development and traces these externalities as a continuation or intensification of existing governance practices. This is demonstrated by the case study on the metropolitan city of Bengaluru, that participates in India's national Smart City Mission. Due to massive urbanization, Bengaluru's peripheries are suffering from increasing pressures on its basic infrastructure. In response, state actors have turned to hybridizing the city's infrastructure facilities and governance to market- and civil society actors. Furthermore, the efforts of middle-class civil society groups that contribute to infrastructural governance through the assistance in planning, facilitation and controlling state responsibilities are institutionalized by bureaucratic state actors, at the cost of electoral governance by local representatives. This analysis on infrastructure governance in the peripheries has been set in relation to a discourse analysis of official policy documents on the inclusive and participatory character of smart cities. The practices of hybridization and institutionalization not only undermine the access to basic infrastructure for marginalized groups but also heavily underpin the design of Bengaluru's smart city projects. To be called inclusive, we argue that smart city projects should make an effort to improve the overall accessibilities of infrastructures for all classes and population groups.

Highlights

Inclusion of smart city can be evaluated by the access to basic infrastructure

Smart cities are spatially fragmented, causing more inequality in peripheries

Free and fair citizen participation can lead to more inclusive smart cities

Citizen participation for smart city projects can deteriorate electoral governance

Research on smart urbanism benefits from assessing legacy infrastructure

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, smart city projects have taken a more central role in the formulation and positioning of urban development trajectories (Glasmeier & Christopherson, Citation2015), and more recently also gained traction in countries such as India, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia (Joo & Tan, Citation2020). Responding to infrastructure failures that are believed to be caused by rural-urban migration and rapid urban population growth, smart city projects have increasingly been perceived and framed as a policy vehicle for inclusive and participatory development, that seeks to improve the overall liveability of the city (Datta, Citation2015b; Glasmeier & Christopherson, Citation2015; Hoelscher, 2019; Kitchin, Citation2015). This premise can be questioned, as these often self-proclaimed ‘participatory and inclusive projects’ may be selective in which infrastructural pressures are eased, and which urban dwellers benefit from the improvements the smart city plans offer. By analysing a case study on smart city development in the city of Bengaluru,Footnote1 India, this article aims to demonstrate how the urban infrastructural realities of marginalization, segregation and peripheralization to be found in the Global South interact with the discourse of ‘inclusive and participatory smart city planning’.

By comparing the empirical infrastructural realities of peripheries in Bengaluru, India, to the city's rationale on inclusivity and citizen participation in its smart city projects, we seek a critical understanding of ‘inclusive’ technological urban interventions. This paper will expand on three key arguments within the debates on (inclusive) smart urbanism.

First, this case study on Bengaluru demonstrates how the articulations of inclusivity and citizen participation in its smart city projects can be traced as a continuation or intensification of prior infrastructural governance practices, rather than unique or particular to smart city development. This argument follows the line of thought by Shelton, Zook, and Wiig (Citation2015), who claim that ‘smart city interventions are always the outcomes of, and awkwardly integrated into, existing social and spatial constellations of urban governance and the built environment’ (p. 14). We trace this integration by responding to the call of Marvin, Luque-Ayala, and McFarlane (Citation2015), who suggest to relate the urban inequalities produced by ‘splintered infrastructure networks’ to the evaluation of inclusive smart city planning. In the case of the peripheries of Bengaluru, ‘splintered urbanism’ (Graham & Marvin, Citation2001) produced three governance practices. Namely, the fragmentation and marginalization of state infrastructure, the hybridization of market and civil society stakeholders as active infrastructure providers and governance actors, as well as the institutionalization of citizen participation in the management and planning of state infrastructure. This article identifies the integration of these governance practices in Bengaluru's smart city plans, based on the premise of forming an inclusive and participatory development policy.

Second, this article expands on the argument by Lee, Woods, and Kong (Citation2020), who contend in their literature review on ‘smart citizenship’ that ‘the inclusive smart city’ has often been (mis)understood as ‘being inclusive to every segment of the population’. Lee et al. (Citation2020) argue that in doing so, there is no consideration for ‘the [free] choice of people to become aligned with the concepts of scale, economic growth and expansion’. Instead, these scholars advocate for understanding inclusive smart citizenship as an effort to promote equality and liveability (p. 2). In the case of Bengaluru, inclusivity is perceived as what we can define as ‘the right to benefit’, referring to benefits that can (only) be acquired through active citizen participation in the smart city programs.

Third, this article aims to contribute to the epistemological discussion on smart urbanism as scholarly field. The literature review by Lee et al. (Citation2020) suggests that – in comparison to Hollands’ earlier critique on the lack on critical analysis (Citation2008) – the discussion on the rationale of inclusive smart cities has steadily grown, but that ‘the methods on how to study [the inclusivity of] smart cities have received relatively less attention’ (p. 9). Most analyses on smart cities consider the development plans as a central research object. Instead, as analytical venture point, this article considers the inclusivity of basic infrastructure in the urban context prior to smart city development, followed by an evaluation on how the smart city projects could improve the access of that same infrastructure. We therefore agree with Verrest and Pfeffer (Citation2019), who argue that ‘there is a lack of consideration for ‘the urbanism’ in smart urbanism’ (p. 1329). Thus, rather than analysing ‘the smart city’ as entity or goal in itself, the concept of the ‘smart city’ is conceptualized in this article as an infrastructural policy intervention embedded in the empirical reality of the peripheral urban dweller. In our perspective, inclusive urban development should help to answer questions that marginalized groups may ask: how to acquire drinking water? How to keep my environment safe and healthy? The empirical focus thus rests on the inclusivity of basic infrastructure, on the improvements of equal availability and access of basic infrastructures such as water and sewerage. Thus, in turn, we understand ‘the inclusive smart city’ to be a technological urban planning intervention that contributes to the access of basic infrastructure for the vulnerable and marginal groups.

1.1. Access to infrastructure in the Global South and Bengaluru

Taking the access to basic infrastructure as baseline for analysing inclusive smart cities, this research has adopted a conceptual model based on the well-established works ‘Splintering Urbanism’ by Graham and Marvin (Citation2001) and ‘Beyond the Networked City’ by Coutard and Rutherford (Citation2015). This framework identifies three interchangeable broad groups of infrastructural suppliers in the Global South: state institutions, market providers and civil society groups.

State institutions were historically understood and imagined to ‘deliver broadly similar and essential services to virtually everyone at similar costs across the city […]’ (Graham & Marvin, Citation2001, p. 8), providing basic infrastructure to those in need. This ‘modernist infrastructural ideal’ has been challenged over time. Specialized, privatized and customized networks have emerged that replace and fragment the prior taken-for-granted equal access to state infrastructure (p. 9). This led to incremental changes in infrastructure systems, that entail a shift from homogeneity to diversity in infrastructure practices, technologies, standards, flows and service suppliers (Coutard & Rutherford, Citation2015).

In much of the Global South, the state retreated in a similar fashion as sole provider of infrastructure, fragmenting the access to basic infrastructure in the process, whilst enabling the development of a private infrastructure market to facilitate basic infrastructure for income classes who can afford it. Moreover, where state infrastructure is lacking and acquiring market infrastructure individually is not an (economically) viable option, citizens can organize themselves in civil society groups as third group that acquire, construct and govern infrastructure in the voids left by the state and market actors. This mode of self-sufficiency is also known as ‘autoconstruction’ and much practiced in the Global South (Bhan, Citation2019; Caldeira, Citation2017; Holston, Citation1991).

Through this conceptual framework, the level of access to basic infrastructure for urban dwellers is depending on the offered availability of the infrastructure providers, on the other hand the citizen's capability to mobilize either state institutions, market providers or civil society groups to facilitate in their neighbourhoods. Those that are through governance practices excluded from access, are what we in this paper refer to as marginalized groups. Inclusive smart city policy would disrupt these exclusionary governance practices and enable marginalized groups to gain access to basic infrastructures.

In the case study on the peripheries of Bengaluru, there are at least three governance practices that have affected the access to infrastructure. As we will demonstrate throughout this paper, these practices are continued or even intensified, rather than disrupted by Bengaluru's smart city plans.

First, a recurring practice is the spatial prioritization of state infrastructure facilities for the city's core over the periphery (De Falco, Angelidou, & Addie, Citation2019; Shaw, Citation2017). Whereas Bengaluru's city-core is relatively well-serviced by infrastructure facilities that are provided by state institutions, facilities for running water, sewerage and street lighting are often inadequate or missing in the peripheries. The analysis of Bengaluru's smart city plans clearly demonstrate the prioritization for further improvement of the city centre, despite the large discrepancy with peripheries’ lacking coverage of basic infrastructures.

Second, whilst market providers and civil society actors in the periphery act as hybridized infrastructural governance actors in the service gap left by the state, low-income groups experience difficulties in acquiring affordable market facilities. Likewise, the urban poor have limited possibilities to benefit from a strongly organized middle-class civil society (Chakrabarti, Citation2007; Chatterjee, Citation2004; Smitha, Citation2010). Bengaluru's smart city plans seem to intensify the hybridization of peripheral infrastructure, strengthening the role of market and civil society actors in its facilitation.

Third, bureaucrats in the city administration and influential middle-class civil society groups have established close cooperation in infrastructural governance. On a strategic level of urban planning, this may occur through citizen-led NGOs and citizen interest groups (Idiculla, Citation2017), whereas the influence of middle-class citizens is localized in neighbourhoods through resident welfare associations (Smitha, Citation2010). These cooperative relations, which in this article are referred to as the institutionalization of civil society and citizen participation, legitimizes decision-making by bureaucratic governance actors that bypasses the authority of elected representatives. This transition of power benefits middle-class citizens, at the cost of the urban poor, who mostly rely on the activities of electoral agents for infrastructural improvement in the vicinity of their dwellings. The legitimizing role of civil society, framed as citizen participation, has a central position in Bengaluru's smart city plans, and will thus also uphold this marginalizing practice.

1.2. Bengaluru in the discourse on inclusive smart cities

Though ‘the smart city’ is rooted by the principle of technological urban advancement, the concept has become ‘a global urban policy and development model, which circulated, migrated and mutated’ the last two decades (Verrest & Pfeffer, Citation2019, p. 1330), leading to various interpretations on its functionality and properties. Generally, the smart city discourse promises to achieve ‘efficient, technologically advanced, green and socially inclusivity’ (Vanolo, Citation2014, p. 883), thought to be able to address urban infrastructural issues (Hollands, Citation2008).

In an effort to temper unrealistic expectations, a growing body of critical academic literature has been established, that discusses the risks and negative consequences of smart city development. For example, authors like Kitchin (Citation2014; Citation2015), Glasmeier and Christopherson (Citation2015), and Meijer, Gil-Garcia, and Bolívar (Citation2016) emphasize caution in regard of technocratic governance, the overreliance on data, privatization and neo-liberalization of infrastructural governance, gentrification and privacy issues. Furthermore, it is often argued that smart city developers often fail to consider the wider contextual effects of the particular histories, cultural dimensions and political economies in which these development projects take place. This certainly is relevant in the urban contexts of the Global South, where urbanization, informality and socio-economic inequalities are omnipresent (Bhan, Citation2019). Neglect of contextual issues has led to concerns about the effectiveness and unintended consequences that smart city projects could have.

Thus, whereas the academic critique warns for the lack of contextual awareness, inclusive policy and one-size-fits-all business packages provided by the tech companies (Kitchin, Citation2014), urban planners and state institutions emphasize the inclusive local character of their development plans. Indeed, in many cases, both in the Global North and South, the design and execution of national projects is decentralized to the city-level to account for the city's specificities (Joo & Tan, Citation2020). Moreover, inclusivity and citizen participation have become important tenets in the formulation of urban planning, designing ‘citizen-centric’ project plans, intended to assure that plans are based on citizen-indicated needs (Cardullo, Di Feliciantonio, & Kitchin, Citation2019; Datta, Citation2018). Although this increased recognition and emphasis on inclusive development should be cherished as a positive advancement in the discourse, it should nevertheless not be taken for granted how citizen participation and inclusion itself are understood and operationalized in smart city projects (Lee et al., Citation2020).

Bengaluru's smart city plans are part of India's current national ‘Smart City Mission’ (SCM). The SCM, launched in 2015, aims to revamp the infrastructure of a hundred cities across India through the implementation of ‘smart technology’. The cities were selected based on a competitive scheme in which the city proposals were evaluated on various criteria, including their inclusive and participatory quality. The city proposals consist both of area-based development projects, as well as projects that would benefit the city as a whole.

Both the national mission and Bengaluru's smart city plans are framed as necessary interventions to deal with the rapid population growth and urbanization, which in turn have put the city's infrastructure under pressure. According to the national guidelines as well Bengaluru's project proposal, smart city applications should be able to alleviate such pressures. However, as the impact of smart city development on governance generally is expected to be incremental and based on legacy infrastructure (Glasmeier & Christopherson, Citation2015), following the established urban development trajectories (Shelton et al., Citation2015), this premise can be questioned. As we argue in this paper, most of the projects focus on improving the image and experience of a visit to the city centre, rather than tackling the pressures on the city's infrastructure that can be ascribed to urbanization. Projects that focus on the improvement of infrastructural governance, shift the service responsibilities and urban planning processes typically dealt with by state actors towards citizens that (have the capability to) actively participate in the participatory schemes the smart projects seek to develop.

1.3. Methodology

This paper presents the key findings of research based on 5 weeks of on-location ethnographic fieldwork in Bengaluru, continued by 2.5 months of data collection and analysis that could be conducted on a distance from the research location. The fieldwork period was heavily affected and shortened by the outbreak of the Covid-19, which led to the methodology discussed below. The research has been structured in two subsequent parts.

The first part entailed a socio-spatial analysis on the access to basic infrastructure in Bengaluru's peripheries. Here, quantitative national census data (Government of India (GoI), Citation2011) and open access city ward data (BBMP, Citation2017) were analysed and spatially visualized with GIS-software, which signified the social and infrastructural discrepancies between Bengaluru's city core and periphery. A qualitative spatial analysis on peripheral neighbourhoods as well as a stakeholder analysis on infrastructural governance have been established, both derived by an ethnographic mixed method approach, to identify the governance practices that underpin the exclusion of access to basic infrastructure. The methods include the analysis of qualitative spatial data of a ward district in the eastern periphery of Bengaluru, participant observation at five key events related to urban governance attended by state officials and civil society members, and eight semi-structured interviews among local urban planners, state representatives and civil society members. The findings derived from these analyses have been validated and substantiated by comparison to existing academic literature on the governance of Bengaluru's infrastructure.

The second part of the research concerned a discourse and policy analysis that sought to analyse the dialectic conceptualizations, perceptions and agendas on the ‘inclusive smart city’ of India's smart city mission, and specifically, in Bengaluru's smart city plans. For this analysis, 30 documents were retrieved from ‘Smartnet’, the digital open access library of the Indian Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. This digital library is the learning platform for India's smart city officials. The pre-selection of 30 documents was based on its relation to inclusive smart city policy, and have been scanned. Of the pre-selection, the five most prominent documents have been closely read, analysed and coded in qualitative coding software (NVivo). These include the guidelines document on India's smart city mission (Ministry of Urban Development, GoI, Citation2015) as well as Bengaluru's smart city proposal (GoI, Citation2017). The analysis of the latter is discussed in this article.

Bengaluru, that entered the smart city mission in 2017, had been lagging behind in implementation of its projects at the time of the conducted fieldwork, due to ‘administrative reasons, political dismal, and a lack of coordination between governmental departments’, as a newspaper reported (Moudgal, Citation2019). As such, most SCM projects in Bengaluru were in the process of implementation in 2020, but were not finished yet at the time of this research. As such, the scope of this paper entails the juxtaposition of the project plans in Bengaluru's smart city proposal, to the infrastructural governance and access to basic infrastructure in the peripheries prior implementation of the projects.

The remainder of this paper is set out in three sections. The second section analyses the facilitation and governance of infrastructure in the periphery, and sets out the urban context in which Bengaluru's smart city plans are informed by the three governance practices of peripheralization, hybridization and institutionalization. What follows in the third section is a discussion on Bengaluru's smart city plans, which highlights how these practices continue to affect marginalized groups through smart city development. The fourth and concluding section facilitates a theoretical discussion of the pitfalls for smart city development in regard to the perceptions of inclusivity and citizen participation.

2. Access to infrastructures in Bengaluru's peripheries

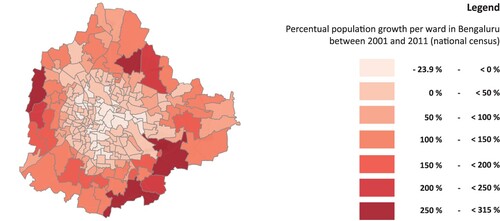

Over the last decades, Bengaluru's population has grown rapidly. In the metropolitan region, 8.52 million inhabitants were counted in the national decadal census of 2011 (GoI, Citation2011). The population reached a 65% growth between 2001 and 2011 (see ). Projections of 2020 have estimated the city's population at 12.36 million inhabitants (World Population Review, Citation2020), marking a 45% growth compared to 2011. Urbanization is perceived as a cause for the city's failing infrastructure. Most notably, in Bengaluru's smart city proposal, it is argued that ‘this rapid growth has strained the existing city's infrastructure, [where] unchecked urban sprawl creates a disconnect with historical identity and city assets lying in neglect’ (GoI, Citation2017, p. 16).

Table 1. Trajectory of urbanization in Bengaluru (1981-2011).Table Footnotea

The spatial distribution of residents over the city wards most notably demonstrates that the majority of new residents settle in the peripheries of the city (). The infrastructure facilities in these areas are underserved by state institutions, particularly in comparison to the city core. Even though over 40% of Bengaluru's population lives in the periphery (Government of Karnataka, Citation2011), it is primarily the core that has consistent and reasonable access to infrastructure provided by state institutions – for example, regarding household sewerage and tap water connections (see and ). In the periphery, governmental agencies are facing challenges catering to the demand for basic infrastructure (Shaw, Citation2017; Sudhira, Ramachandra, & Subrahmanya, Citation2007). These challenges include the delivery of drinking water, sewerage, electricity and waste management, as well as issues with traffic congestion, air, water and lake pollution (Nagendra, Nagendran, Paul, & Pareeth, Citation2012; Sudhira et al., Citation2007). Improvements to infrastructure are thus most needed in the periphery, to attain and liveable circumstances with equal access to basic services for everyone (Lee et al., Citation2020).

Figure 1. Urbanization in Bengaluru: population growth per ward (2011 census data). Source of data: District Census Handbook Bangalore (Directorate of census operations Karnataka, 2014).

Figure 2. The state’s tap water network in Bengaluru: percentual household coverage per ward (BWSBB, 2017). Source: Smart City Challenge Round 3: Smart City Proposal Bengaluru [Annexures, p. 5] (GoI, 2017).

![Figure 2. The state’s tap water network in Bengaluru: percentual household coverage per ward (BWSBB, 2017). Source: Smart City Challenge Round 3: Smart City Proposal Bengaluru [Annexures, p. 5] (GoI, 2017).](/cms/asset/7bc48737-5ba3-4ff4-abf9-0485c49834aa/rjus_a_1938640_f0002_oc.jpg)

Figure 3. The state’s sewerage network in Bengaluru: percentual household coverage per ward (BWSBB, 2017). Source: Smart City Challenge Round 3: Smart City Proposal Bengaluru [Annexures, p. 5] (GoI, 2017).

![Figure 3. The state’s sewerage network in Bengaluru: percentual household coverage per ward (BWSBB, 2017). Source: Smart City Challenge Round 3: Smart City Proposal Bengaluru [Annexures, p. 5] (GoI, 2017).](/cms/asset/59076fe1-1e2f-4c7a-bf1f-84234c9741ca/rjus_a_1938640_f0003_oc.jpg)

Within the peripheries, the infrastructure facilities delivered and maintained by state institutions are splintered, selective, and allocated based on political influence (see Coutard & Rutherford, Citation2015; Graham & Marvin, Citation2001). Within the city core the facilitation of infrastructure by state institutions correlates less to the socio-economic background of its residents, as almost all residents have access (Shaw, Citation2017). The periphery is however characterized by the absence of such extensively networked state infrastructure, which have led to variegated outcomes in citizen's access to basic infrastructure.

2.1. Hybridization of infrastructure: market and civil society as infrastructural governance actors

In the absence of extensive state-facilitated networked infrastructure in the peripheries, citizens need to turn to infrastructure providers in the market segment. For example, as in most peripheral areas less than 50% of the households are connected to a tap water network, historically, most residents relied on water from borewells. However, as over time most of the accessible ground water has depleted, many peripheral households are currently serviced by private water tanker companies, whose deliveries are considerably more expensive than water connected to the state-facilitated network. Likewise, residents who are affluent enough can purchase or rent backup generators to guarantee continued access to electricity, despite frequent outages. Logically, upper- and middle-class residents are more able to afford marketized infrastructure than low-income inhabitants, given their better financial capability. Low-income groups are thus more reliant on state infrastructure to secure access to basic services.

Furthermore, civil society groups, most often consisting of primarily middle-class citizens, organize themselves through the principle of self-reliance and function as ‘informal governance actor’ (Smitha, Citation2010). Where the state does not plan, facilitate, or maintain their infrastructure, local civil society groups, called ‘Resident Welfare Associations’ (RWAs), partly facilitate and maintain infrastructures in their neighbourhood. RWA activities include doing small repairs on state infrastructure – e.g. fixing streetlight switches or pipe leakages – or improving or renewing infrastructure themselves, often in interaction with market infrastructure providers. Also, as example, RWA members in a neighbourhood in the eastern periphery of Bengaluru collectively purchased a water tower, by pooling financial capital. This improved the availability of drinking water, by which residents were not dependent anymore on expensive marketized water tankers, and did not need to await potential infrastructural improvement by state actors.

Such beneficial activities of civil society groups are not accessible to all residents. For example, if a slum is outside the self-defined territorial delimitation of an RWA, it can be presumed unlikely that the RWA extends its infrastructural maintenance services inside the slum. Likewise, if slum dwellers do not feel welcome to participate in RWAs, their slums are unlikely to be included by the services of the respective RWA. Thus, although civil society groups such as RWAs positively impact the aggregate availability of basic infrastructures in the periphery, the benefits they create for nearby residents are limited by their territorial scope. This territorial demarcation is likely related to the majority presence of middle-class citizens in such civil society groups; group-forming may find its roots on mutual identification through socio-economic background, ethnicity, caste and religion (Smitha, Citation2010), and therefore contributes to the splintered infrastructure facilitation that characterizes the periphery.

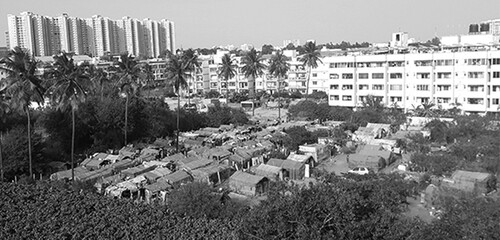

Conclusively, the peripheries have an infrastructural configuration in which market providers and civil society groups, adjacent to the state, have a hybrid function in initiating, providing, maintaining and governing basic infrastructure services. The multiplicity of infrastructure actors, each with their limitations in catering to the whole population, leads to an infrastructurally splintered urban environment with variegated levels of access to basic services. The individual household outcomes depend on the financial capabilities to acquire access to market services, as well as on the inclusion or exclusion of group-organized efforts to collectively improve or maintain the infrastructure in the vicinity of the individual's dwelling. With the heterogeneous compilation of citizens living in the city's outskirts, in terms of quality of living, urban fragmentation has become a common occurrence (see ). Where certain plots of land basic services suffice, for their neighbours do not. As such, although the presence of hybrid governance of market and civil society actors is locally understood as necessary in the absence of the state, it does not help the cities’ poorest. Instead, it enlarges the disparity between income groups in the periphery.

2.2. Institutionalization of civil society groups

Although the hybridization of infrastructural governance reduces the immediate necessity of state infrastructure to access basic services for most peripheral residents, governance by market providers and civil society groups does not occur in isolation from the state. Market infrastructure providers limitedly cooperate with the state through public-private partnerships and can be scrutinized and accounted for by locally active political agents. Civil society groups, however, closely cooperate with (bureaucratic) state officials to control and monitor the functioning of existing state infrastructure, whilst influencing the agenda-setting for future infrastructure development plans (Idiculla, Citation2017). Given this close association between state and civil society, civil society groups are highly influential in the allocation and management of state infrastructure, and thus also who gets access to basic services.

The activities by Bengaluru's civil society groups may be considered as duties for government employees or elected representatives. However, they are daily practice in the Indian metropolis. On a neighbourhood level, RWAs intensively patrol their neighbourhoods daily to monitor the waste collection, street cleaning, street lighting and water and sewerage facilities, and appeal to state officials when regular jobs are not executed according to the expected standards. RWAs also request infrastructural improvements at the local ward representatives, who address these concerns to higher authorities. On a city-wide level one can observe how civil movements, citizen interest groups and politically orientated NGOs fulfil similar functions as the elected members of the parliament (the opposition) by making demands for more public data, transparent, accountable governance, and call for more citizen participation. Such organizations mobilize political power to influence agenda-setting of infrastructure development by publishing (media) reports and joining in events organized by the government, such as public debates and discussion groups. In Bangalore, as well as in other Indian cities, the active participation of (primarily middle-class) citizens in the maintenance and allocation of infrastructure in the peripheries is understood as the status quo.

Bureaucrat officials are generally very cooperative to such civil society activities, and seem to enthusiastically support the functions of governance of such groups, both on neighbourhood- and city-wide level. Based on the observations made during the fieldwork for this research, state officials reportedly attend civil society meetings to exemplify policy, aiming to expand the access to governmental data. Moreover, bureaucrat officials regularly invite high-profile civil society groups for public debates and expert group discussions that contribute to the drafting of various visionary and strategic documents for future urban development (Idiculla, Citation2017). It is noteworthy that Bengaluru's smart city plans were largely based on such a document – the Bengaluru Blueprint (Janaagraha, 2016) – which was formulated by high-ranking state officials and market and civil society leaders.

Through these close collaborations with bureaucrat state officials, empowered by middle-class citizen participation, high-profile civil society groups represent ‘the city's residents’ at the bureaucratic administration, whilst acquiring access to a platform of bureaucratic decision-making. Such influential groups then become an institutionalized governing actor in the allocation and revitalization of infrastructure. In turn, policy decisions by bureaucrats, made in cooperation with civil society groups, are legitimized in the framing that policy is based on input derived by citizen participation. Important is, however, that these civil society groups primarily suffice in the needs of the middle-class, who are able to mobilize sufficient capital and political power to acquire basic infrastructure, and desire a higher standard of living beyond just the basic needs (Hoelscher, Citation2016; Smitha, Citation2010). In turn, the livelihoods of low-income groups do not necessarily benefit from more access to basic infrastructure services as a result of the institutionalization of civil society groups.

Moreover, this institutionalization is also troublesome for the political empowerment of marginal groups. Various scholars indicate that Indian metro-urban poor mobilize local electoral governance actors as primary strategy to improve their access to basic infrastructural services, whereas middle-class turn to bureaucratic governance actors (Chakrabarti, 2008; Harriss, Citation2005; Idiculla, Citation2017). By the institutionalization of middle-class civil society, these groups operate as a governance actor parallel to the representation of elected local politicians. Whereas elected representatives ought to control the bureaucratic performance and set the political agenda, they can be more easily bypassed as policy is already validated and set by civil groups, who operate in collaboration with bureaucrat officials based on the framing of citizen participation. Hence, the institutionalization of civil society groups effectively secures more political power for bureaucratic governance actors as civil society legitimizes their policy decisions, which in turn reduces the already limited political power of marginalized groups mobilized through electoral governance. As the interests of the urban poor and marginalized groups are not represented through this form of governance, they are excluded from this ‘political arena’ (Aasland & Fløtten, Citation2001).

3. Hybridization and institutionalization in Bengaluru's smart city projects

Above, we established the argument that the state's prioritized facilitation of basic infrastructure in the core over the periphery, the hybridization of infrastructural governance and institutionalization of citizen participation, are essential processes that limit the access of peripheral low-income groups to basic state infrastructure services. This section demonstrates that the same processes heavily underpin Bengaluru's smart city projects, and can thus be seen as a continuation of the city's urban development trajectory.

Additionally, in Bengaluru's smart city proposal, it is stated that the design of the projects are not only based on the consultation of elected representatives, urban planners, vendors and suppliers of smart city technology, but it is also frequently highlighted that citizen participation through on- and offline channels have played a central role in the policy-making processes. In this section we argue that (digital) citizen participation in smart city development functions as a legitimization for bureaucratic governance. The implementation of the smart city development is an exclusive bureaucratic endeavour, and similar to its institutionalization of citizens in civil society groups, undermines the influence of electoral governance at the cost of marginalized groups.

More specifically, all smart city projects under India's Smart City Mission are implemented by so-called ‘special purpose vehicles’ (SPVs). Bengaluru's SPV, called ‘Bengaluru Smart City Limited’, is a parastatal agency with a powerful bureaucratic position. SPVs can operate autonomously and in complete independence of the city government and the state government – in the case of Bengaluru, the state Karnataka – and can thus not be held accountable for its actions by elected politicians (GoI, Citation2017, p. 69). Instead, citizen participation – e.g. by the format of digital voting, but also by public consultation meetings and the sanctioning by prominent civil society groups – functions as the legitimization of the smart city projects that are set up by the SPV. As such, instead of an electoral representation based on the factual socio-demographical distribution, the smart city projects are backed by a limited array of politically active citizens who are in the position to digitally participate.

This is problematic, as multiple participants argued during interviews that the focus on digital participation is an imminent problem that can contribute to the exclusion of marginalized groups, such as elderly and the urban poor. Likewise, academic sources warn that (digital) illiteracy may create a ‘digital divide’ (Van Dijk, Citation2006) that may result in ‘digital spaces that emerge from ‘smart citizenship’ as a functional separation between ‘sealed-off technological enclaves and leftover marginalized spaces’’ (Vanolo, Citation2014, p. 891). As such, enabling digital citizen participation ought to give legitimacy to the development projects, but mostly helps to expand the already-present platform for state-citizen collaboration, with citizens that do not rely on state-facilitated basic infrastructure, and will thus not mobilize state institutions for that purpose.

3.1. Area-based projects: ‘smart trinkets’ for the city centre, water shortages in the periphery

In the design of India's SCM, a hundred cities were selected on the basis of various urban characteristics and on the quality of the respective city proposal (Datta, Citation2015a). Bengaluru's ‘Smart City proposal’ consists of two parts. The first refers to ‘area-based development projects (ABD)’, which covers 94.02% of the total development budget.Footnote2 The analysis of ABD projects is discussed below. Additionally, various ‘pan-city projects’ are detailed, which ought to improve the city as a whole, primarily by improving the city's governance. Both project-types are discussed in this and following subsection.

In regard of the ABD projects, the national guidelines for the city proposals instructed that the to-be -developed area – either by retrofitting, redevelopment or greenfield development – should be compact and replicable (GoI, Citation2015, p. 5). Instead of selecting a small area, Bengaluru's smart city proposal sets out multiple retrofitting and redevelopment projects across the city centre. The majority of budgeted expenses for area-based development is directed towards important landmarks, that are ought to embody the ‘identity of the city’. Locations include the central business district (covering 72.49% of the budget), mobility hubs, referring to two bus stations, a market, a park and a metro station (14.62%), and two historic markets (11.92%), which – together with four other projects – ought to create ‘a safe, healthy, well connected and vibrant city centre’.

By reserving most of the financial resources for the development of the city centre, Bengaluru's smart city plans align with the trend discussed by De Falco et al. (Citation2019), who argue that smart city development most often prioritizes city cores over peripheries. Likewise, of the six other smart cities in Karnataka, only one city, Belagavi, focuses its ABD on the periphery. Furthermore, the ABD projects include components like ‘e-toilets’, ‘smart bus shelters’ and ‘smart street lighting’, as well as the purchase of 150 e-buses and 150 e-rickshaws. It can be questioned if the implementation of these components are necessary, when it is set off against the state of basic infrastructure in the periphery, where in many areas less than 50% of the households has a connection to the water and sewerage networks (see and ).

The choice to develop certain parts of the city centre, which is based on online and offline forms of citizen participation, is explained in the proposal. The core argument is that the centre ‘belongs to and is used by everyone’, as it has ‘the highest footfall in the city due to higher order urban amenities and services’ (GoI, Citation2017, p. 25). Further developing these areas are believed to ‘enrich the identity of the city, address major urban issues, enhance economic opportunities and converge with [already ongoing] government projects and schemes’, which ‘improves the liveability […] of the city’ (p. 24). The focus of Bengaluru's smart city plans prioritizes the experience and image of the city, rather than mobilizing smart city technology to improve the access (of marginalized groups) to basic infrastructures.

Of course, it can be argued that the city centre also has infrastructural issues that need tending. For example, traffic congestion and waste pollution are common. However, the selected core areas will be attributed with what can be called ‘smart technology trinkets’, such as e-toilets or solar panels. Nevertheless, as various interviewed research participants argued, the projects that make use of such technology, will most likely only mitigate the symptoms of problems, and not solve the actual problems. For example, a ‘smart dustbin’ can give a signal when the bin is almost full, to be directly tended to by a garbage collector. Although useful to improve temporary cleanliness of certain areas, it does not help solving ‘the root causes’ of the uncontrolled waste production which the city is dealing with. As such, it is likely that the smart city projects, which are set up in response to urbanization pressures, will only provide symptomatic relieve rather than tackling the structural causes of the issues.

3.2. Pan-city projects: E-governance and the institutionalization of citizen participation

The emphasis on (digital) citizen participation, that arguably had a major role in the selection and locations of the ABD projects, is also inherently embedded in the project design of various pan-city projects of Bengaluru. When referring to the SCM as a whole, the changing governance practices are best explained by Datta (Citation2018). She argues that the emphasis on citizen participation in smart city policymaking prescribe citizens to be ‘tech-savvy, entrepreneurial and work on behalf of the state, innovation and growth.’ In this role, ‘smart people’ become ‘collaborators and endorses of the smart city, rather than critical and active citizens’, Datta suggests (Citation2018, p. 413). This argument is certainly applicable when analysing Bengaluru's pan-city projects, as is demonstrated below.

Nevertheless, the origins of this phenomenon are not new. When placed in the urban development trajectory of the city, the participatory approach can be traced back to Bengaluru's governance practices of hybridization of infrastructure governance, and the institutionalization of citizen participation for the governance of state infrastructure. What is more, the practice of institutionalization of citizen participation is actively framed as inclusive development. In particular, two of the planned pan-city projects – focused on neighbourhood security and participatory budgeting, discussed in Boxes 1 and 2 – stand out as being the most actively framed and explicitly mentioned as an inclusive project in the proposal document. These projects, among others, enlarge the function of institutionalized citizen participation, and strengthen the position of the already active citizen as complementing governance actor.

Amongst the various objectives for Bengaluru's Smart City Mission, categorized under the section ‘equity and inclusion’, is the objective to ‘reduce crime, including crimes against women and children’ (GoI, Citation2017, p. 17). Explaining the demand for this project, in the proposal is stated:

With the ascending IT sector in the city, Bengaluru has seen an exponential population influx. A resultant of which triggered strain of existing infrastructure, change in social structure, income disparity and loss of equity in access to public goods, all of which have had an influence on growing crime rates in the city. (p. 50).

Whereas before institutionalized citizen participation would be limited to the controlling, maintenance and allocation of state infrastructure, Bengaluru's citizen participation will be further institutionalized by enforcing public order through a formal cooperation between city police and actively participating citizenry. In terms of inclusivity, it poses various questions. For example, who will be enlisted for these beat patrol groups and security committees, and will marginalized groups be fairly represented? And what stance do these citizens to take against technically not legal or informal practices, that are regardless omnipresent in the peripheries?

As the causes for the higher prevalence of crime are perceived to be ‘insufficient infrastructure’ and ‘income disparity’, increasing enforcement underlines the symptomatic approach of the externalities of problem, rather than taking action against the root issues that are thought to have caused the increase in crimes in the first place. Furthermore, by framing the community policing initiative as a democratic and citizen-led practice, the increased enforcement by digital surveillance is legitimized, as the negative effects are presumably ‘checked-and-balanced’ by citizen participation. Conclusively, by equating inclusivity to ‘neighbourhood safety for all’, Bengaluru's development focus is diverted from improving equal and inclusive access to basic infrastructure.

One of the other long-term objectives of Bengaluru's smart city development seeks to have ‘30% of city budgets utilized through participatory budgeting processes’ (GoI, Citation2017, p. 17). To realize this goal, Bengaluru's smart city SPV will develop an online citizen application that ‘consolidates neighbourhood and ward level inputs from citizens’ (p. 50). The application for participatory budgeting is described as the primary trump that demonstrates the inclusivity of Bengaluru's smart city development (p. 52).

Based on this framing, it can be argued that the act of facilitating citizen participation itself is understood as the primary form of inclusivity in Bengaluru's smart development plans. The idea that all citizens have the possibility to actively participate in filing their preferences and suggestions, for example to be able to digitally vote for suggested ideas, may be seen as a progressive step for marginalized groups to be heard. Nevertheless, this articulation of inclusivity aligns with Lee et al.'s argument that the ‘inclusive smart city’ is misinterpreted as ‘being inclusive to every segment of the population’, rather than perceiving inclusivity in terms of promoting equal and liveable livelihoods (Citation2020).

Furthermore, citizen participation will be further institutionalized by the participatory budgeting scheme, as the duty of the state to allocate finances for the improvement infrastructure is transferred to the citizen that actively participates. The need for bureaucratic decision-making to be held accountable by local politicians will become more redundant, as the allocation is derived from the digitally indicated needs by means of citizen participation, and is in this framing thus per definition ‘inclusive’ and fair. Participatory budgeting then further undermines the political influence of local politicians – electoral state actors – on whom low-income groups rely for their improvements in access to basic infrastructure.

Moreover, the participatory budgeting application is a continuation of earlier practices, as it provides a digital supplement for an already established political arena. That is, the practice where citizens appeal for infrastructural improvements through middle-class resident welfare associations, who in turn appeal directly to local state officials responsible for infrastructure – appealing to local bureaucrat state actors. Digital participatory budgeting thus effectively eases the collaborative governance practice between active middle-class citizens and local bureaucrats. As such, it is doubtful that the access and availability to basic infrastructure for the marginalized population will thereby be much improved. Those that have actively cooperated with bureaucrats before, middle-class groups, can also ensure their access to basic infrastructure through market providers and civil society activities, and can therefore subtract the attention to middle-class aspirations beyond basic infrastructure, and as soon the application is ready, also digitally.

The two projects detailed above, framed in Bengaluru's smart city proposal in the category of ‘equity and inclusion’ (p. 17) and as ‘inclusive and truly citizen centric’ (p. 52), shed light on the broader conceptualization of inclusivity and citizen participation in smart city development, and to a lesser extent also on India's national smart mission administration, who accepted this proposal to be executed.

Of course, some arguments are likely to be made in defence of Bengaluru's smart city plans, and ought to be discussed (and refuted) as part of a complete narrative. In particular, in Bengaluru's proposal it is recognized that a lack of participation is ‘one of the greatest risks that could prevent the success of the pan-city projects’ (p. 52), which suggests the adverse effects of the unequal political dynamics within the population have been accounted for. Two strategies have been listed in the smart city proposal to mitigate ‘the digital divide’.

First, to prevent minimizing the benefits of pan-city developments only to the digitally capable, the proposal details that the pan city projects ‘also take into consideration [the] limitations of digital reach [of] all socio-economic strata of the urban population that hinder [the] success of online platforms’ (p. 52). The proposal details about the establishment of ‘smart kiosks’ across the city, which ‘are equipped to register citizen feedback and disburse information available on online platforms’ and where ‘coordinators designated at these kiosks will be trained to assist the illiterate and physically challenged people’ (p. 52). It seems questionable if the establishment of kiosks will make a difference in the allocation of basic infrastructure accessible for marginalized groups. Regardless, it is an interesting strategy of which the measurement of the impact would be valuable for other governance projects that centralize citizen participation.

The second strategy to ensure citizen participation in Bengaluru's pan-city projects is the creation of ‘awareness educative programs in various agencies and citizen [population] groups’. It details that ‘digital education will be enabled to enhance the use of technology’ (p. 52). As such, the state takes on a pedagogic approach to transform the city population into a ‘smart citizenry’ (Hollands, Citation2008; Datta, Citation2018). Educative schemes for the sake of increased institutionalized citizen participation may undermine the liberty and agency of citizens to decide to participate (Datta, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2020), and can thus be doubted as an ‘inclusive’ strategy.

Conclusively, the institutionalization of citizen participation and the hybridization of the active citizen as infrastructural governance actor, are practices that occur in both urban governance, before and after the introduction of smart city projects. Furthermore, ‘inclusivity’ is here understood as ‘the right to benefit through participation’. This conceptualization is embedded in projects that establish a digital political arena in addition to a prior-existing analogue one. Likewise, ‘smart’ in Bengaluru equates to enlisting citizens for citizen patrols and a surveillance network, rather than providing better basic infrastructure. Instead, it may be time to advocate more powerfully for smart cities that focus on the inclusivity of access to basic infrastructure.

4. Conclusion: revisiting inclusion and citizen participation in smart city development

Having made the comparison between the empirical infrastructural realities of the peripheries and the city's rationale on inclusivity and citizen participation in its smart city projects, this case study on Bengaluru contributes to various debates on (inclusive) smart urbanism.

In the context of the rapid urbanization occurring in the Global South, it is understandable that smart cities have a strong appeal to nation-states and city administrations in Asia. Characterized by informality and income disparities, urbanization undermines the state's grip on the governance of urban spaces. In turn, access to basic infrastructure services have become heavily under pressure by the increased demand (Shaw, Citation2017). As such, seizing the well-marketized benefits of ‘smart’ technology may seem like a too-good-to-pass offer for urban planners, as it has the promise to increase the capability to govern and suit to the demand and desires of the population (Allam, Citation2018).

However, the case of Bengaluru does not underwrite the idea that smart cities are implemented as one-size-fits-all packages (Glasmeier & Christopherson, Citation2015; Kitchin, Citation2015). Rather, following the line of thought of Shelton et al. (Citation2015), smart city interventions are ‘outcomes of, and integrated into, existing social and spatial constellations of urban governance and the built environment’ (p. 14). Bengaluru's smart city plans claim to be largely based on citizen- and civil society input, and are designed according to the logic of the city's infrastructural governance, as it aims to fully make use of the prior well-established collaborations with the city's civil society groups.

A main takeaway from this study is that the analysis on smart cities should not only include a state- or market perspective, but benefits from considering all actors involved in infrastructural governance. When through participatory initiatives citizens and civil society groups are increasingly involved in the design and execution of smart city projects, it makes sense that these ‘institutionalized governing actors’ should also be accounted for in scholarly research. Moreover, in the context of the Global South, it is important to consider the governance practices related to informality, fragmentation and peripheralization prior the implementation of smart city projects, as these are likely to find their way back into the design of development policies.

In line with Lee and colleagues’ (Citation2020) argument that the ‘inclusive smart city’ is often (mis)understood as one that is ‘inclusive to every segment of the population’ instead of one that ‘promotes equality and liveability’ (p. 2), the case of Bengaluru warns us for the conditionality of inclusion. A first condition is that when inclusivity is seen as ‘the right for citizens to claim benefits’, where one needs to participate to before one can gain from smart city development. As mentioned, this undermines the liberty and agency of citizens to decide to participate (Datta, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2020). A second condition is that of access to the infrastructure that smart city development improves. Smart city projects often merely improve the quality of legacy infrastructure (Glasmeier & Christopherson, Citation2015), and do therefore not the solve underlying problems that limits the access to infrastructure for all citizens in the first place. We argue that smart city projects should not merely focus on symptomatic fixes to suit the needs of the users that can already use the infrastructure, but should make an effort to improve the overall accessibilities for all classes and population groups to be called inclusive. Emphasizing the unconditionality to utilize improved infrastructure facilities is necessary in both designing smart city projects, as well as when researching smart cities.

Lastly, as smart cities have utopian connotations of ‘fixing the urban issues away’ (Allam, Citation2018; Datta, Citation2018), a critical assessment is necessary on what smart city project can and cannot do. Scholars on inclusive smart urbanism should in developing their research designs well account for the temporality in which the effects of smart city projects come to be. Such an assessment should preferably start before these projects are implemented, as is done in this research. This allows the researcher to distinguish the (intended) effects of the smart city from continuations, intensifications or expansions of earlier governance practices. Doing so enables the scholar to emphasize ‘the urbanism in smart urbanism’ (Verrest & Pfeffer, Citation2019). For example, one can identify the lack of access to basic infrastructure, potential changes in infrastructural use, or even development opportunities to resolve the root causes of urban issues. Research after project implementation can in turn provide insights in the differences between policy ideas and final development effects, but will have difficulties in distinguishing between what is and is not the cause of smart city development. As such, establishing a research agenda in which smart city locations are addressed in the different phases of implementation, will further demystify the concept of the smart city, and may contribute to more inclusive development plans in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru, for providing hosting on research location.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Also known as the city of Bangalore.

2 Area-based development projects were projected to cost 1685.13 crore rupees of the total amount of 1792.35 crore rupees. This roughly equals to a €190 million investment of the total €200 million scheduled cost of the SCM projects detailed in Bengaluru's proposal in December 2020 (GoI 2017, p. 77).

References

- Aasland, A., & Fløtten, T. (2001). Ethnicity and social exclusion in Estonia and Latvia. Europe-Asia Studies, 53(7), 1023–1049.

- Allam, Z. (2018). Contextualising the smart city for sustainability and inclusivity. New Design Ideas, 2(2), 124–127.

- Bhan, G. (2019). Notes on a southern urban practice. Environment and Urbanization, 31(2), 639–654.

- Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike. (2017). Micro Plan BBMP Ward [1-198]. Retrieved from Open City Urban Data portal (https://opencity.in/pages/latest)

- Caldeira, T. P. (2017). Peripheral urbanization: Autoconstruction, transversal logics, and politics in cities of the global south. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(1), 3–20.

- Cardullo, P., Di Feliciantonio, C., & Kitchin, R. (2019). The right to the smart city. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

- Chakrabarti, P. (2007). Inclusion or exclusion? Emerging effects of middle? Class citizen participation on Delhi's urban poor. IDS Bulletin, 38, 6.

- Chatterjee, P. (2004). The politics of the governed: Reflections on popular politics in most of the world. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Coutard, O., & Rutherford, J. (2015). Beyond the networked city: An introduction. In O. Coutard & J. Rutherford (Eds.), Beyond the Networked city (pp. 19–43). Routledge.

- Datta, A. (2015a). A 100 smart cities, a 100 utopias. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 49–53.

- Datta, A. (2015b). New urban utopias of postcolonial India: ‘entrepreneurial urbanization’ in Dholera smart city. Gujarat. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(1), 3–22.

- Datta, A. (2018). The digital turn in postcolonial urbanism: Smart citizenship in the making of India's 100 smart cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 43(3), 405–419.

- De Falco, S., Angelidou, M., & Addie, J. P. D. (2019). From the “smart city” to the “smart metropolis”? building resilience in the urban periphery. European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(2), 205–223.

- Glasmeier, A., & Christopherson, S. (2015). Thinking about smart cities. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 3–12.

- Government of India. (2011). Bangalore (Bengaluru Urban Region Population 2011 [census data]. Retrieved from https://www.census2011.co.in/census/metropolitan/388-Bengaluru.html

- Government of India (GoI), Ministry of Urban Development. (2015). Smart City mission statement and guidelines. Smartnet library, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, GoI. https://smartnet.niua.org/content/2dae72ca-e25b-4575-8302-93e8f93b6bf6

- Government of India (GoI), Ministry of Urban Development. (2017). Smart City Challenge Round 3: Smart City Proposal Bengaluru. Smartnet library, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, GoI. https://smartnet.niua.org/content/c8fdaabb-767c-4854-befc-9e9966c28282

- Government of Karnataka, Ministry of Home Affairs, Directorate of Census Operations Karnataka. (2011, October). Census of India 2011. District Census Handbook Bangalore. https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/dchb/2918_PART_B_DCHB_BANGALORE.pdf

- Graham, S., & Marvin, S. (2001). Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. London: Routledge.

- Harriss, J. (2005). Political participation, representation and the urban poor: Findings from research in Delhi. Economic and Political Weekly, March 12, 1041–1054.

- Hoelscher, K. (2016). The evolution of the smart cities agenda in India. International Area Studies Review, 19(1), 28–44.

- Hollands, R. G. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand up? Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial?. City, 12(3), 303–320.

- Holston, J. (1991). Autoconstruction in working-class Brazil. Cultural Anthropology, 6(4), 447–465.

- Idiculla, M. (2017). Who Governs the City? The Powerlessness of City Governments and the Transformation of Governance in Bangalore. Paper presented at RC21 International conference on “The Ideal City: between myth and reality. Representations, policies,:contradictions and challenges for tomorrow’s urban life”. (pp. 1–29). University of Urbino (Italy).

- Joo, Y. M., & Tan, T. B. (2020). Smart cities in Asia: An introduction. In smart cities in Asia. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kitchin, R. (2014). The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal, 79(1), 1–14.

- Kitchin, R. (2015). Making sense of smart cities: Addressing present shortcomings. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 131–136.

- Lee, J. Y., Woods, O., & Kong, L. (2020). Towards more inclusive smart cities: Reconciling the divergent realities of data and discourse at the margins. Geography Compass, 14(9), e12504. 1–12.

- Marvin, S., Luque-Ayala, A., & McFarlane, C. (2015). Smart urbanism: Utopian vision or false Dawn? New York, NY: Routledge.

- Meijer, A. J., Gil-Garcia, J. R., & Bolívar, M. P. R. (2016). Smart city research: Contextual conditions, governance models, and public value assessment. Social Science Computer Review, 34(6), 647–656.

- Moudgal, S. (2019, October 25). Bengaluru lags in Smart City implementation. Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/bengaluru-lags-in-smart-city-implementation/articleshow/71749676.cms

- Nagendra, H., Nagendran, S., Paul, S., & Pareeth, S. (2012). Graying, greening and fragmentation in the rapidly expanding Indian city of Bangalore. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(4), 400–406.

- Pellissery, S., Chakradhar, A., Iyer, D., Lahiri, M., Ram, N., Mallick, N., … Harish, P. (2016). Regulation in crony capitalist state: The case of planning laws in bangalore. Der öffentliche Sektor (The Public Sector): Planning, Land, and Property: Framing Spatial Politics in Another age of Austerity, 42(1), 110.

- Shaw, A. (2017). Metropolitan governance and social inequality in India. In Inequality and governance in the metropolis (pp. 57-76). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- Shelton, T., Zook, M., & Wiig, A. (2015). The ‘actually existing smart city’. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(1), 13–25.

- Smitha, K. C. (2010). New forms of urban localism: Service delivery in Bangalore. Economic and Political Weekly, 45(8), 73–77.

- Sudhira, H. S., Ramachandra, T. V., & Subrahmanya, M. B. (2007). Bangalore. Cities, 24(5), 379–390.

- Van Dijk, J. A. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics, 34(4-5), 221–235.

- Vanolo, A. (2014). Smartmentality: The smart city as disciplinary strategy. Urban Studies, 51(5), 883–898.

- Verrest, H., & Pfeffer, K. (2019). Elaborating the urbanism in smart urbanism: Distilling relevant dimensions for a comprehensive analysis of smart city approaches. Information, Communication & Society, 22(9), 1328–1342. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10. 1080/1369118X.2018.1424921

- World Population Review. (2020, December 12). Bangalore population 2020 [UN World Urbanization Prospects]. Retrieved from https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/bangalore-population