ABSTRACT

The implementation of participatory planning has encountered numerous challenges, including the exclusion of certain groups such as children, whose aspirations and participation are often overlooked. Earlier studies highlight how digitization has opened up new opportunities for community participation in city planning. Gamification is a technique that has become increasingly popular in recent years for optimizing the effectiveness and impact of participatory city planning. This study explores the potential of utilizing Roblox as a gamification tool in inclusive urban planning for children, using it to examine their ideal city concepts. Through workshops and semi-structured interviews with 10 primary school students in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area, we found that Roblox effectively facilitates the visualization of the built environment. Despite technical challenges, it emerges as a promising participatory tool for children in urban planning. The study identifies two prevalent themes in children's ideal cities: pollution-free environments and convenient access to public amenities. This research contributes by introducing a unique gamification approach through Roblox for involving children in urban planning discussions and filling a gap in research on gamification and children's participation that predominantly stems from Western countries. Unlike previous studies that mainly utilized games to educate children, our emphasis on understanding children's perceptions also adds to existing literature.

HIGHLIGHTS

Interactive gaming like Roblox has proven effective in eliciting children’s ideas regarding their ideal city preferences. However, follow-up interviews are still needed to explore the ideas behind their city designs.

Indonesian children envision their ideal city with three key themes: maintaining pollution-free air, incorporating abundant green spaces, and ensuing accessible public facilities.

Involving children in the planning process not only protects their rights, but also allows practitioners to reflect, develop collaborations, and incorporate more voices into policy and urban planning.

Roblox, with its ability to create customizable virtual worlds, provides a unique platform for researchers to study children’s urban design preferences. By analyzing their creations and interactions within these virtual spaces, researchers can gain valuable insights into what aspects of city life children find most important.

This approach offers several advantages over traditional methods like surveys or interviews. In Roblox, children can express their ideas in a more creative and engaging way. They are not limited by pre-defined options or language barriers. This can lead to a richer understanding of their preferences and priorities.

1. Background

Previous research findings into children’s participation within the city planning context have shown that children's viewpoints are integral to the development of smart and sustainable cities in various ways. Their inclusive perspective ensures that future generations’ needs are considered, promoting equity (Biggeri et al., Citation2019). Their environmental awareness emphasizes sustainable practices, contributing to pollution reduction and green space preservation (Davis, Citation1998). Children's input aids in designing child-friendly infrastructure, prioritizing accessibility and safety and their innovative ideas inspire creative solutions to urban challenges, fostering efficient urban design (Ataol et al. Citation2019; Caroll et al. Citation2019; Mansfield et al. Citation2021). Involving children educates and empowers them, making them active participants in shaping their communities and fostering a sense of ownership. Ultimately, children's insights lead to more comprehensive and progressive urban planning, creating livable cities for people of all ages.

However, enhancing children’s participation in the planning process is challenging and requires finding feasible solutions. Conventional approaches often fail to engage a diverse range of stakeholders, particularly those who may not possess technical expertise or feel comfortable voicing their opinions in formal settings – including children (Ghanbri, Citation2014). As a result, numerous studies investigate diverse techniques and tools that could enhance public engagement in urban planning ().

Gamification, involving the application of game-like elements to non-game contexts, stands out as an innovative method. It offers a promising avenue for bridging the traditional methods gap and encouraging active citizen involvement in urban planning. The integration of game mechanics, such as points, rewards, and leaderboards, has the potential not only to motivate citizens to participate in planning activities, but also to provide feedback on specific plans or proposals, and contribute their unique perspectives to shaping their communities (Ampatzidou et al., 2018; Özden et al., Citation2023). Gamified platforms can also serve as virtual spaces for collaboration, enabling citizens to engage in discussions, share ideas, and collectively envision the future of their cities (Haahtela, Citation2015).

The primary objective of gamification is to actively involve users in doing desired actions and addressing real-world issues through the incorporation of game components. In urban planning, addressing real-world issues entails overcoming the lack of citizen participation, which typically necessitates prolonged engagement in order to provide consistent input to a generally lengthy decision-making process (Münster et al., Citation2017). Thus, in recent years, governments have employed gamification to improve the usefulness and quality of participatory planning processes (Constantinescu et al., Citation2020). Notable examples of usage of gamification comprise UN-Habitat and Stockholm City Mayor using Minecraft to engage residents, London City Mayor utilizing Metaverse, Tirolcraft focusing on heritage protection (Balgaranov, Citation2023; Cordero-Vinueza et al., Citation2023; UN-Habitat, Citation2021).

Despite utilizing tools tailored to children's interests and capacities, such as using games, existing initiatives often struggle in effectively employing gamification to include children in participation efforts (Bankler et al., Citation2020; Clarinval et al., Citation2023). This limitation is evident in the gamification methods often proposed for youth and adult participation (e.g. Bonora et al., Citation2019; Meier et al., Citation2020; Muehlhaus et al., Citation2023). A systematic review of gamification in e-participation also revealed a lack of studies specifically focused on employing gamification for children's e-participation (Hassan and Hamari, Citation2020). Published solutions facilitating the engagement of younger audiences remain scarce, despite evidence indicating that children are willing to participate in decision-making opportunities (Clarinval et al., Citation2023).

One of the gamification types that has been recently garnering popularity is Roblox. Beyond gaming, Roblox serves a broader purpose; its primary aim is to blend gaming and social interaction uniquely – users can create 3D games, share them online, or explore an expanding game catalogue. A notable advantage of the platform is its user-friendly interface, particularly beneficial for those without programming experience (Meier et al., Citation2020). It is no wonder therefore that Roblox users has been reported to have reached 70.2 Million daily active users by 2023, with 43.96% of them are under the age of 13 – that belong to Gen Alpha Generation – with the majority of this group being over the age of nine.

Despite its recent surge in popularity, especially over the past few years, the utilization of Roblox in the context of urban planning participatory processes remains relatively understudied. Meanwhile, Roblox becoming increasingly prevalent among Generation Alpha, the current generation of children. The oldest among this age group are now entering their teenage years. In this light, there arises a compelling need for a study to delve into the potential of Roblox as a tool for actively involving children in the city planning process. This leads us to identify Research Gap 1: the lack of studies that specifically explore the utilization of gamification, particularly through platforms like Roblox, for children's involvement in the urban planning process.

This study seeks to explore the potential of gamification, particularly through Roblox, as a participatory tool for children in an inclusive urban planning process, with a specific case study: the development of Ibukota Nusantara (IKN), Indonesia’s new capital city. The urgency to implement the inclusive urban planning process, particularly by considering the perspectives of children, has become crucial as the Indonesian government constructs this new capital, intended to be smart, sustainable, and the country’s first child-friendly city. However, a recently released report by the Indonesian Ministry of Women's Empowerment and Child Protection has revealed that none of the cities in Indonesia have fully met the requirements to be recognized as a Child-Friendly City (Kompas, Citation2023). This sobering truth shows the difficulties encountered by the country in guaranteeing the welfare and entitlements of its youngest inhabitants. Among the various concerns, the report emphasizes the imperative requirement for the active involvement of children in decision-making processes (Agiani, Citation2023). Thus, this research intends to support the implementation of participatory city planning by comprehending children's perspectives and exploring innovative methods, particularly through gamification, to enhance their involvement in the planning process. Research Gap 2 is articulated as follows: the absence of initiatives aimed at capturing children's perspectives on their ideal cities.

The research is structured around two main questions: (1) How can Roblox be utilized to gain children’s perceptions for participatory urban planning? (2) What city elements do children consider as important to be included in their ideal cities? By addressing these questions, this study aims to explore the potential of gamification, specifically leveraging the platform Roblox, as a participatory tool within the context of inclusive urban planning for children. In this case, Roblox is employed to help us in visualizing children’s preferences regarding the city they aspire to live, which can be done by utilizing various city components incorporated within their envisioned city design.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the literature review, we identify gaps and justify our study on children's participation in urban planning, also exploring gamification's theoretical foundations and its potential impact on children’s participation. The methodology outlines our two data collection approaches: workshop and interviews. The findings section presents the children's perceptions and essential elements in the ideal city, leading to the discussion that interprets these findings in relation to existing literature. The conclusion summarizes key findings, highlights theoretical and practical contributions, and proposes avenues for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. Children’s participation in urban planning

The practice of involving children in planning is increasingly recognized across various intervention domains, including social, spatial, policy, and learning. Recent studies highlight the growing importance of children's participation in urban planning, emphasizing that involving children can foster a culture of empowered and active young citizens (Ataol & van Wesemael, Citation2019). Integrating children into urban planning and policymaking offers practitioners an opportunity for introspection, a better understanding of diverse relationships, and the incorporation of a wider range of voices, all while respecting the rights of children (Derr & Kovács, Citation2017). Furthermore, certain geographical factors, including traffic and access to natural areas and local surroundings, can have an indirect impact on children's perceptions. In this case, analyzing children’s perceptions can also be helpful to tell how well local systems of government are implementing children's rights in a certain area (Cordero-Vinueza et al., Citation2023). This inclusive approach enhances the planning system's capacity to transform by acknowledging children as crucial urban stakeholders, thereby improving its ability to create environments conducive to children's well-being (Nordström & Wales, Citation2019).

Despite the growing interest in children’s perspectives in urban planning, specifically in their contributions to public spaces, neighborhoods, and cities, the focus on Millennials and Gen Z is predominant while there is limited information on involvement of Generation Alpha. Generation Alpha, born in 2010 through the uprise of digital age, exclusively utilize digital technology and electronics (Zaczkiewicz, Citation2023). As they reside online, most frequently within a video game rather than online, they are least likely to make a purchase on a website and most likely to do so in a game. Governments should address children's best interests while implementing smart technology, considering how technical innovation cannot be separated from its effects on children's growth and participation in urban life (Cordero-Vinueza et al., Citation2023).

2.2. Gamification as urban planning participatory tool

The term ‘gamification’ refers to a set of procedures and activities that use aspects of games to address issues (Özden-Schilling, Citation2023). It can be further defined as the process of incorporating game elements and mechanics into non-game contexts with the aim of enhancing engagement, motivation, and participation. It involves applying game design principles, such as points, badges, leaderboards, challenges, and rewards, to make activities more game-like and enjoyable (Werbach, Citation2014). There are several research frameworks that can be used to analyse the gamification process (as seen in ). These frameworks provide a structured approach to evaluating the effectiveness of gamification interventions and identifying areas for improvement (Martínez-Mesa et al. , Citation2016).

Table 1. Research frameworks to analyze the gamification process.

In urban planning, gamification, offers a promising avenue for bridging this gap and encouraging active citizen involvement. The integration of game mechanics, such as points, rewards, and leaderboards, has the potential to motivate citizens to participate in planning activities, provide feedback on specific plans or proposals, and contribute their unique perspectives to shaping their communities (Ampatzidou et al., 2018; Özden et al., Citation2023). Gamified platforms can also serve as virtual spaces for collaboration, enabling citizens to engage in discussions, share ideas, and collectively envision the future of their cities (Haahtela, Citation2015).

Gamification holds immense potential for revolutionizing public participation in urban planning, particularly for intricate projects. This approach can effectively structure and simplify complex planning information, enhancing engagement, comprehension, and overall understanding of the planning procedures and decisions (Kazhamiakin et al., Citation2015). By incorporating game elements and gameful design, gamification can effectively enhance user motivation, foster a sense of task accomplishment, and strengthen social connections throughout the planning process (Gheorghe et al., Citation2023; Haahtela, Citation2015; Muehlhaus et al., Citation2023).

Additionally, gamification aids in educating urban planning while promoting critical thinking and problem-solving abilities. It enables users to test concepts, simulate performance, and explore applications for smart city before the construction is built (Khan & Zhao, Citation2021). Urban planning also benefits considerably from gamification since it encourages transparent decision-making and open communication, paving the way for successful urban planning outcomes (Özden et al., Citation2023). The application of urban gamification as a source of data for spatial data analysis and interactive predictive modelling in urban planning is covered in Olszewski and Siegel (Citation2016).

Even with its significant potential, gamification in urban planning also comes with challenges. One concern is the risk of oversimplifying the planning process by reducing it to a mere point-collection exercise (Ampatzidou et al., Citation2018). This oversimplification may undermine the depth and quality of citizen engagement, limiting their ability to provide meaningful contributions. Another challenge lies in the resistance from process facilitators, who may lack experience with participatory methods or harbor skepticism towards using games in planning processes. Addressing these concerns require concerted efforts to educate facilitators about the benefits and limitations of gamification, enabling them to make informed decisions about its suitability in specific planning scenarios (Gheorghe et al., Citation2023).

The study by Kazhamiakin et al. (Citation2015) advocates the importance of a co-creation approach to bolster the effectiveness of gamification in urban planning. This approach involves active community participation in developing gamified applications, ensuring alignment with the needs and aspirations of the intended audience. Furthermore, the authors found that the utilization of smaller game components and mini-games, rather than large-scale, complex game systems. This approach offers greater flexibility and adaptability, allowing for more efficient use of resources, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Gamification also promotes public participation by engaging a wide range of users, tying personal characteristics to real-world situations to hear other people's opinions, and connecting spatial, temporal, and digital information(Bankler et al., Citation2020; Muehlhaus et al., Citation2023). For instance, IkigaiLand, a gamified experience developed by Bhardwaj et al. (Citation2020), allows individuals to build communities and enhance urban design according to their goals and expectations. Azali (Citation2021) also demonstrated that through the use of 3D visualization tools, gamified participatory design fosters collaborative design thinking, enhances group planning conversations, and improves participants’ comprehension of planning challenges. Wilson et al. (Citation2019 in Bankler et al., Citation2020) introduce an endeavor that employs the ChangeExplorer smartwatch app to stimulate public engagement in urban development. The app offers users a text-based interface, enabling them to contribute suggestions for enhancing the urban environment. In essence, gamification assists urban planners to engage the public and make decisions more inclusively.

2.3. Gamification and children’s participation

In recent years, there has been extensive discourse on the application of gamification to enhance children's learning across various domains. The efficacy of the gaming approach lies in its ability to captivate and sustain children's interest while facilitating direct communication and idea assessment (Angelidou et al., Citation2017). While much of the existing research delves into the effectiveness of gamification in educational contexts, particularly in promoting teaching and learning (Li et al., Citation2023), similar discussions extend to urban planning. Through gamification, urban planners can gain insights into the perceptions of children. The gaming technology has demonstrated its effectiveness as urban planning education tools for children in their participation, interaction, learning effectiveness, and knowledge transfer (Akbulut & Tavsanoglu, Citation2018).

Several urban initiatives for children have been published, with objectives to educate children about the urban planning process and assess its effectiveness in enhancing their participation in this process. For instance, Clarinval et al. (Citation2023) utilized Democracity, a digital participatory role-playing game, to educate and engage 299 children (aged 12–14) in Belgium on the smart city concept. The workshop involved collective urban planning exercises, such as redesigning city based on an existing city map. The findings indicated a significant improvement in the children's understanding of the smart city concept and underscore the potential of Democracity as a tool for fostering children's active participation in urban planning. Similarly, Bonora et al. (Citation2019) aimed to investigate the impact of DIGITgame as an approach to teach topics around STEM, including smart cities, to secondary school students in Italy and Turkey.

Prior research has explored the use of gamification to enhance children's learning experiences beyond the traditional classroom setting, simultaneously involving them in civic activities. Rehm et al. (Citation2014) created interactive learning environments for Danish children (6–10 years) in public spaces using gamification. The first project focused on developing an exploration game, supported by a virtual tour guide in a museum, enhancing social interaction. In the second project, third-grade children learned geometrical concepts in the city through a location-based mobile application with tailored learning content and mini-games. Meanwhile de Andrade et al. (Citation2020) investigated the applicability of Minecraft as a tool for both older and younger children (aged 4–14) in a small rural village in Tirol, Brazil. The experiment, conducted in a workshop format, employed a scenario approach. Children were tasked with changing and co-designing Tirol's landscape within the Minecraft gaming environment. The study revealed that the game effectively motivates, inspires, and engages children of various age groups in the urban planning process.

Despite these initiatives, the available literature on the use of Roblox remains limited. This scarcity is specifically pronounced when considering its application as a participatory tool for children in the urban planning context. For example, Meier et al. (Citation2020) employed Roblox to create a virtual tour showcasing the city's sculptural heritage, aiding students with mobility issues to navigate interactive environments. Their study involved 53 secondary school students (14–17 years old) tasked with designing a virtual environment featuring 3D models of Santa Cruz de Tenerife's sculptural heritage. Results indicated heightened awareness among students about sculptural heritage, affirming their confidence in creating interactive worlds with Roblox. Hernández et al. (Citation2022) conducted a study focused on classroom experiences employing Roblox in game-based learning activities for Mexican students. Similar to the previously mentioned study, this study concentrated on secondary, high school, and college groups instead of children. Their findings highlighted the effectiveness of Roblox in facilitating learning on diverse topics and interpersonal skills, with participants expressing positive perceptions of the activity and emphasizing social interaction.

Despite the limited existing research on the use of Roblox for participatory planning, Roeselera, a city in Belgium, has innovatively employed Roblox as a platform to engage children in the redesign of the city's playground (Balgaranov, Citation2023). The city’s objective is to empower local children who enjoy playing Roblox to actively contribute to the design of the playground by constructing the playgrounds of their dreams. Once the planning phase of the project is completed, the city plans to incorporate as many of the children's ideas as possible into the actual redevelopment. However, as this is still an ongoing project, there has not yet been additional information available regarding the outcomes and the effectiveness of Roblox in this participatory process.

Based on the literature review, it is evident that there is a notable lack of attention to the utilization of Roblox, especially within the context of urban planning. However, addressing this gap is not the sole focus of our study. As mentioned earlier, within the domain of studies integrating gamification and children’s participation in urban planning, only a limited number have delved into understanding children’s perspectives. Many of these studies employ gamification to educate children about the urban planning process and to assess the effectiveness of different gamification approaches in enhancing children’s understanding. Thus, a significant gap persists in addressing children's perceptions regarding their needs and aspirations for the city they envision living in. This gap is crucial, as involving children in urban planning should inherently aim to discern their perspectives.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that the majority of literature assessing the relationship between gamification and children’s participation originates from the Western world, primarily European countries. Consequently, there is a need for more studies in diverse nations to examine the use of games in supporting children’s participation. By presenting the viewpoints of children living in Indonesia, our study aspires to contribute to this understanding within the context of Asian cities. This regional perspective is vital for a comprehensive exploration of gamification and children's involvement, acknowledging the diverse cultural and contextual factors influencing these dynamics.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

As our research focuses on Generation Alpha, we took a purposive sampling approach (Martínez-Mesa et al., Citation2016). By this, we specifically chose children from middle – and upper-middle-class families within the age range of 10–13 as our target demographic. The exclusion of younger children is deliberate, as their perspectives are still in the formative stages. According to Jean Piaget's theory (Huitt, Citation2003), children between 10 and 13 years of age fall into the concrete operational stage. This developmental starts from around the age of 7 years until around 11 years. During this stage, children develop the ability to think logically and perform mental operations. They can understand and manipulate information in their minds, allowing them to answer questions more effectively. This cognitive development enables them to solve problems, make inferences, and think critically, all of which are essential for answering questions.

In addition to that, our study exclusively encompasses children residing in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. The decision to choose students from the Jakarta Metropolitan Area was based on several reasons: (1) Contextual relevance: The study aimed to explore the perceptions of children living in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area, which includes the current capital city of Jakarta. By focusing on children from this specific area, the authors aimed to grasp how their experiences and environment shaped their perceptions of the ideal city, (2) Comparison with the existing capital: Jakarta is known for its high levels of air pollution and traffic congestion, among other urban challenges. By comparing the children's perceptions of their ideal city with their experiences in Jakarta, the authors aimed to understand how the existing capital city influenced their visions of an ideal city, (3) Feasibility of data collection: Conducting research with children requires coordination with parents and schools. Focusing on the Jakarta Metropolitan Area, the authors could easily coordinate with the participants and conduct the necessary workshops and interviews. It is crucial to note that while the study focused on children from the Jakarta Metropolitan Area, the findings may still offer valuable insights applicable to other urban contexts.

Participants were recruited voluntarily based on those who responded to our call for participation that we posted on our social media (i.e. WhatsApp and Instagram). The poster explicitly outlines the criteria: children aged 10–13 residing in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. Those meeting these requirements and interested in participating are required to complete a questionnaire. This step ensures that participants are not only capable of playing Roblox Studio as players but are also capable of engaging in city design activities.

After searching for participants for two weeks, we initially identified 15 individuals who met the requirements. However, five participants were excluded from the process for various reasons. Two participants withdrew from the study as it became apparent that they were unable to utilize Roblox Studio for city creation. One participant was discovered to reside outside the Jabodetabek area, while the other two failed to respond to our messages. Ultimately, the final group of research participants consisted of ten children, as illustrated in below.

Table 2. Details of participants.

We have chosen to proceed with our research involving 10 participants, as it fulfills the minimum requirement for qualitative research, particularly in terms of conducting in-depth interviews in participatory research. Previous studies indicate that the minimum number of participants for such interviews varies depending on factors such as study objectives, available resources, researcher expertise, and population characteristics. However, participatory research employing interviews typically requires a minimum of 10–20 respondents to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the issue (Bekele et al., Citation2022; Saunders et al., Citation2016; Tiffany, Citation2006).

Furthermore, since this research is grounded in the phenomenological approach, aimed at identifying patterns through exploring participant experiences, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings, previous research suggests that sample sizes for this approach often range from as small as three to as large as 15 individuals who have encountered the phenomenon under investigation (Moser & Korstjens, Citation2018; Urcia, Citation2021).

3.2. Data collection and analysis

Our study employs two data collection approaches: workshop and interviews. We conducted a workshop as the extensive review of literature encompassed works by Bankler et al., Citation2020; Clarinval et al., Citation2023; Elvstrand & Liisa Närvänen, Citation2016; UN-Habitat, Citation2021 indicated that a workshop would be the most efficient way to obtain participatory data. Researchers are encouraged to conduct workshops related to gamification in urban planning, as participatory workshops provide planners with access to local knowledge that may otherwise be challenging to obtain (Keeton, Mota, and Tan, Citation2020). However, existing literature also suggests that workshop alone may not fully capture respondents’ perceptions, necessitating additional support through interviews. The main advantage of interviews lies in their ability to explore the thoughts of respondents more in-depth. Consequently, a follow-up interview was conducted after the completion of the workshop.

During our preliminary phase, we conducted a pre-workshop session at the authors’ university with four children to collect feedback, enabling refinements for the subsequent actual workshop. This session revealed valuable insights. The children faced constraints in constructing their city within the specified time frame. While their imaginations extended far beyond, the two-hour session limited their realization to a few components, including buildings, roads, stores, restaurants, and playgrounds. Consequently, for the actual workshop, we have allocated a half-day duration to address these limitations.

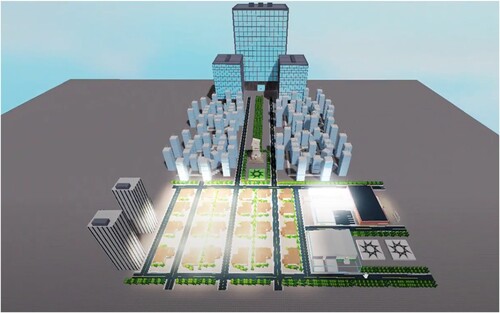

On the workshop day, we provided participants with a briefing on the expected output – designing their ideal city. We shared examples of our version of ideal city without directing specific city elements they should build. Each participant was provided with a computer with Roblox Studio installed, accompanied by our research team for technical assistance. The following day, interviews took place at the author’s university. The participants were divided into four groups, each led by a primary researcher and an assistant; we engaged with a participant at a time in separate rooms, adhering to designated time slots for focused interactions. Consequently, each group of interviewers was responsible for engaging with 2–3 children. The interview content was tailored to each participant's design output, aiming to explore their perceptions and the stories behind their designs. To conclude the interviews, we presented a simplified version of the ideal city based on urban planning theories adjusted for children's understanding.

For the data analysis, we employed the techniques that are frequently used in the this type of data analysis, namely reading and rereading the material while coding it to find common recurrent patterns. All digital data (audio and video files) from the interviews were transcribed and coded using the software Atlas.ti 8. During the coding process, all the important phrases and words were coded and categorized according to their degree of similarity, and finally key themes were discovered for each group.

4. Findings

Two themes related to the core idea of the children’s dream city emerged from our analysis of the Roblox design and interview materials. The following paragraphs will elaborate on each of these themes.

4.1. ‘A city without pollution’

Despite the fact that the children could decide themselves what they wanted to include in their ideal cities, it was immediately apparent from the design and interviews that the children generally held the opinion that their ideal cities would have all of the essential elements of a city, including housing, roads, transportation, and facilities for recreation, business, worship, health, and education. It is interesting to note, however, that when describing some of these components, there were recurring phrased used by all children, regardless of the particular component being addressed at the time. For instance, while describing transportation, the children said they purposefully designed a city with the idea of fuel-free cars so that the city would be free of pollution, including vehicle emissions.

‘Most vehicles produce smoke, which becomes pollution. The thing is, I don't want the city to be polluted so I can stay healthy. Thus, I don't want to include them (vehicles). Even if there are vehicles, I want all the vehicles in this city to use electricity because I don't want any pollution.’ (No. 9)

‘There is nothing to pollute in this city since there are no cars. Green energy powers everything. Even if there is a car, it must be electric. If it's close, you can walk there; if it's far, you can take an electric car like Tesla or ride a bicycle.’ (No. 4)

Some children, however, provided the option to drive a car if it is necessary, such as while rushing to get somewhere. Nevertheless, they still chose public transportation, bicycles, and walking. ‘Vehicles will cause pollution, so the use of motorbikes or cars is only allowed for an emergency, for example, when you are late or in a hurry. If not, you must use a bicycle’ (No. 2). This sentiment was echoed by other children as well.

‘It depends on what people want to ride, but I would suggest public transportation to reduce the use of cars and motorbikes, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. That’s why there are numerous pedestrian streets in this city, as well as bike lanes, trams, and buses.’ (No. 1)

The children's comprehension of creating a pollution-free city may also be demonstrated in how some of them intentionally built small cities with short distances between facilities so that they area ccessible by foot or by bicycle. This way, the usage of cars may be decreased, resulting in a pollution-free city. ‘In my opinion, using a private car in this city will be useless because, as you can see, the city is enough to walk or bike. It's like, I can walk less than 1 km from my house to school or the business district. More precisely, we can walk less than 15 min to arrive at the destination.’ (No. 5). This statement aligns with the other child’s statement:

‘Before this, I made a bigger city. There are many tall buildings there. But because I accidentally didn’t save the design, I made another one. But this time I changed it to a small island because, after I thought about it, I think it’s better to create a small city to avoid pollution. So, you can walk or ride a bike anywhere.’ (No. 9)

Aside from the transportation and the city size, the children create several other things to reduce or eliminate pollution in their dream city In this regard, they emphasized the green elements such as trees, parks and urban forests, believed to improve air quality and water absorption. Some instances are found in the following statements: ‘This green field was created because it absorbs a lot of water, keeps the air clean, and makes the city looks nice too’ (No. 1); ‘Because the forest helps to keep the city fresh and maximizes air (quality)’ (No. 2); ‘Those are trees that keep the houses around them cool all year’ (No. 5). Other than adding greenery, some children purposefully built their cities near mountains with the same aim in mind: to breathe clean and cool air.

Some children also strived to keep the air clean and pollution-free by distinguishing the roles of the cities they design from those of other cities. ‘If you want to put a factory, maybe you have to go to another city because this city is a place for residents, so it's not suitable for factories’ (No. 5). This response agrees with to another child:

‘So, this city I've created is like a suburb, close to nature. While the main city is similar to an industrial district, with manufactures and facilities where our city's trash is recycled and processed for various purposes. This is done to differentiate between polluted and non-polluted environments … In order to make people's lives easier.’ (No. 4)

As illustrated above, the children articulated the distinction between cities indicating how industrial zones, landfills, and waste processing facilities were linked to pollution. This divide was the means to increase the quality of life for the residents.

Finally, several respondents – primarily the 6th graders, indicated that adopting renewable energy, such as solar and wind power, can assist in minimizing pollution in the city. The following kids state how solar energy can be used to power buildings and how wind energy may be used to replace fossil fuels for electricity:

‘Because it (the city) is still under construction, it still requires electricity from fossil fuel. So, in the future, the plan is to replace it (the fossil fuel) with solar power and wind. Because this is located in a high area near the mountains, there is a high probability of wind. Windmills will be installed later in the upper mountains, generating power that will also be distributed to the city.’ (No. 4)

‘There are no gas stations in this city, and as a result, it is totally powered by sun. Solar panels are also used in buildings and houses. For example, all of the windows in this city may be utilized for solar systems. As a result, all of the buildings in this city are powered by these windows, which may also operate as a solar system.’ (No. 5)

4.2. ‘A city where my house is close to some public facilities’

As mentioned previously, the children believe that their ideal city is the one where they can navigate on foot, bicycle, or public transportation. It becomes clearer when the children describe where they reside and their proximity to various public facilities. Regardless of whether the children preferred apartments, landed houses, or both, the results of the design and interviews suggest that it was important for them to have their homes in close proximity to schools and offices. The children quoted below pointed out why schools and offices should be close to their houses:

‘There is a tall building (office building) near my house, so my mother doesn't have to go far to get to work, and if there is an event outside the office, she can also participate because it is close to home.’ (No. 7)

‘I put the school here on purpose because I don't want it too far away from my house. I can just walk since it is healthy. In addition, apartments are available behind the school for persons who do not own a home yet. Then there's an office next to it where my parents can pick me up, and we can go home together.’ (No. 9)

Hospitals and police stations are two more places commonly cited by children. The rationale is that, while visiting the facility, getting there quickly is typically more critical. ‘Smooth access to hospitals can help emergency patients be treated immediately’ (No. 2). Several respondents indicated the proximity of the police station for the same reason: if something happened, it could be reported promptly and serve to make the neighborhood safer. A child also noted specifically about it: ‘The police station is close to the house, so if someone steals or loses something from their house, they can simply walk to the police station’ (No. 4).

Public spaces like parks, plazas, and playgrounds are also often adjacent to residential neighborhoods. Most children chose these public places near residential neighborhoods to access them any time, such as after school, in the afternoon, or whenever they are bored playing at home.

‘In front of the residential area, there is a park where kids may play with their friends and ride their bikes. I purposefully placed it in front of the residential area so that the residents could just walk to the park.’ (No. 9)

5. Discussion

Roblox is an effective way to visualize and reshape the built environment. As a game that gives users a space to create, innovate, and engage in single-player games with others, Roblox Studio can be a great starting point for gamification research. However, there are some challenges that the children encountered. They did not include some components in their city ideas since they were not free or could not be found in Roblox. Some believe that the component (in terms of size or form) they wish to incorporate does not match the shape of the design they have created. As a result, the design only partially reflected their vision of the ideal city they intended. Therefore, the interview's role is crucial in helping to explore the children's perceptions that may not be fully portrayed in their designs.

Another challenge has to do with technological issues, which is the Roblox program itself, which sometimes slows on their laptop due to being too ‘heavy’. The challenges of using digital games in a school environment have been examined in previous studies (Marklund et al., Citation2014), which revealed that despite the powerful aspects of games, there are many difficulties in using them as tools for learning, particularly regarding technological issues such as wireless network stability issues and hardware/software malfunctions.

The study findings have also shown that although children have generally included a variety of city amenities, they typically can only include one or two variations of each facility. Even while certain elements were present in the children's ideas when they began designing the city, they did not emerge in their drawings despite being stated in interviews. Many elements of their city design were left out due to the various participation barriers, and time is the most common one. Almost all kids have at least one city element they wish to add, but they need more time since they have to spend time building other city elements.

According to the design the children created, their ideal city is characterized by clean air and is free from pollution, and – based on their perceptions – is possible to create in various ways: (1) Designing a city that is easily accessible from everywhere so that residents are encouraged to walk and ride bicycles over driving, (2) Reducing vehicle emission gas by switching to an electricity-based fuel for private and public transportation, (3) Incorporating green areas such as fields, parks and urban forests to maintain clean air and maintain the beauty of the surrounding environment, (4) Segregating residential areas from other designated areas, such as industries, so that residential areas are not exposed to pollution from industrial areas. The other theme that emerged from the findings was a city in close proximity to public facilities from residential areas.

The children's awareness of these city necessities, which has been emphasized as a concern in urban planning generally, shows that the game has successfully captured something significant – not only by successfully capturing the children's perspective but also by engaging them in aspects that are crucial to the context of urban planning. In this light, it is intriguing to look at how the children's perception of their ideal cities compares to the findings of a systematic review on the features of Child-Friendly Cities (CFC) by Cordero-Vinueza et al. (Citation2023). According to the study, children thrive and develop resilience in compact cities where parents spend time with their kids. This aligns with the themes of this study, particularly in the children’s wish to establish a city where some public amenities, including offices and schools, are close to their houses so they could spend more time with their parents.

Malone (Citation2013) investigated similar theme on the role of children, who investigated the role of children as urban researchers and environmental change agents in neighborhood design in an Australian suburban town, Dipto. The study showed that the children were also asked about their dream neighborhood, and the themes emerging had great likeliness. This highlights the ability of children to envison cities for their peers with sustainability in mind. Those themes include ‘a place that keeps and protects nature’, ‘a place that is safe and clean’, and a place supporting play and has playgrounds’.

A study by Bankler et al. (Citation2020) on participatory planning with Swedish children aged 8–16 years old also found that most children placed homes and schools close to forests and nature. To avoid pollution and the detrimental effects of the factories on occupants and wild animals, on the other hand, factories were located away from homes and green spaces. This is similar to the themes of the study's ideal city, where children's needs and desires for parks and green open spaces are still predominant – regardless that previous studies have shown that virtual leisure is highly favored by the Alpha generation (Astapenko et al., Citation2021).

6. Conclusion

In the past fifteen years, the subject of digital public involvement in planning has been studied in both academic circles and in real-world settings. Various digital technologies were employed to foster interaction and enhance understanding of the perspectives of various stakeholders. Among these digital tools include social media, virtual and augmented reality, with gamification being the most popular currently (Muehlhaus et al., Citation2023). Games have been used into several participatory planning initiatives in the past, but in recent years, gamification – the combination of games with digital technology – has witnessed a surge of interest (Bankler et al., Citation2020).

Research on gamification is most prominent in the fields of education, health, and crowd-sourcing. However, there is no investigation into whether gamification elements have the same effects in different fields or for different purposes. More diverse research in other fields is necessary to understand the impact of gamification elements in different contexts. The current research provides a perspective on the application of gamification for children’s participation in urban planning. It aims to bridge this gap by investigating children’s conceptions of the ideal city and their aspirations for the future.

The main questions of this paper are how Roblox can be utilized to gain children’s perceptions for participatory urban planning, and what city elements do Indonesian children consider as important to be included in their ideal cities. This study was conducted through a child-focused participatory workshop that utilizes Roblox as a digital medium for participation to help children visualize their ideas, followed by interviews to gain better understanding of their perspectives.

This research makes significant contributions in several ways. First, it introduces a novel approach by examining the use of gamification, specifically through the platform Roblox, as a participatory tool for involving children in the urban planning discourse. By harnessing the interactive and immersive nature of gaming, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of Roblox in eliciting and expressing the preferences and ideas of children regarding their ideal cities. The study's findings further enrich the gamification literature by offering insights on the challenges and limitations inherent in utilizing digital games in participatory planning. The article aptly addresses technical issues, such as the constraints of the Roblox program and the time limitations faced by children in crafting their ideal cities. These insights serve as valuable guidance for future research endeavors and pave the way for refining gamification approaches in participatory planning for greater effectiveness. Furthermore, this article makes substantial contributions to the gamification literature by providing practical insights and compelling evidence of the applicability of gamification techniques in the context of urban planning, with a specific emphasis on children's participation. It eloquently demonstrates the transformative power of incorporating gamification strategies to engage and empower children in shaping their urban environments, ultimately fostering inclusive and sustainable cities.

Second, many previous studies have been emphasizing on the utilization of gamification to educate on urban planning and asses children’s understanding after the workshop. Therefore, our study, which focuses on gaining children’s perception, can contribute to the existing literature. It is evident that the children desire for their city to have pure air (pollution free) and the proximity of public facilities to residential areas. The children's envisioned city prioritizes on these themes with achievable measures including: (1) Ensuring city accessibility to encourage walking and cycling over driving, (2) Transitioning to electricity-based fuel to reduce vehicle emission gases, (3) Introducing green spaces like parks and urban forests for clean air and aesthetic appeal, (4) Separating residential areas from industrial zones to minimize pollution.

In this context, it is noteworthy that the children's visions of an ideal city are in line with perspectives commonly held by urban planners. This correlation closely corresponds with the ‘compact city’ concept, a prominent global paradigm of sustainable urbanism since the 1990s. This concept emphasizes compactness as a means of reducing travel distances and shortening commute times, with sustainable transportation and green spaces serving as core strategies to achieve sustainability objectives. Notably, it aligns with children's emphasis on transitioning to electricity-based fuel to mitigate vehicle emissions and incorporating green spaces such as parks and urban forests.

Children's perspectives on the ideal city also resonate with the ‘15-minute city’ concept proposed by Moreno et al. (Citation2021), which is also referred to by various other terms such as ‘complete communities’, ‘mixed-use city’, or ‘10-minute city’. This urban planning concept underscores the importance of designing neighborhoods to provide residents with essential amenities – such as shops, schools, parks, leisure facilities, and healthcare services – within a 15-minute radius by foot or bike, thus reducing reliance on automobiles for daily activities. This concept closely mirrors the themes prioritized by children in envisioning their ideal city, particularly their desire for easily accessible public facilities in residential areas and a city layout conducive to walking and cycling over driving.

This study showed that children know a lot more than we, adults, have anticipated. They are aware of the inclusive city where all its residents should be treated equally, the availability of bunkers or underground cities for disaster mitigation, and the differences between ‘city centre’ and ‘suburb’ regarding their characteristics and functions. The children, particularly the sixth graders, also understand sustainability, as evident in their explanations of waste segregation, renewable energy, and waste banks. They also add interesting insights regarding a safe city that can be achieved not only through the presence of the police and city components that can help maintain security, such as street lighting and security cameras, but also disaster mitigation and equality of socioeconomic status. All of these notions of the children participated in this study is covered in Gestalten and Space10’s (Citation2021) 5 fundamental principles of an ideal city concept: resourceful, accessible, shared, safe and desirable.Footnote1

To sum up, our research sheds light on the valuable perspectives of children regarding the ideal city which may introduce alternative criteria diverging from conventional notions of rationality within urban planning theory. We posit that this deviation is precisely what renders our study significant in contributing to the broader discourse on participatory urban planning. By focusing on the unique viewpoints of children, who are often marginalized in urban planning processes, our study seeks to bridge existing gaps in the literature. While rational planning typically prioritizes efficiency, economic considerations, and expert-driven decision-making, we argue that incorporating children's perspectives offers a more holistic and inclusive approach to urban development.

Utilizing the gamification tool Roblox to engage children in discussions about their ideal city underscores the importance of imagination, creativity, and inclusivity in shaping urban environments. Although children's aspirations may not always align with traditional rational planning criteria, their perspectives offer valuable insights into the social, cultural, and environmental dimensions of urban life often overlooked in planning processes. Therefore, in order to ensure that urban environments truly reflect the needs and aspirations of all residents, we advocate for the integration of diverse stakeholder perspectives, including those of children, while acknowledging the importance of rational planning approaches in efficiently achieving urban development goals.

Involving children in the planning process not only upholds their rights but also provides practitioners for introspections, expand collaborations, and inclusions of more voices in policy and urban planning. However, a major challenge for planners and decision-makers lies in ensuring that the final implementation accurately portrays the ideas of the children.

Highlights.docx

Download MS Word (14.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the research participants whose support and generosity made this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The 5 principles of the ideal city are underpinned by a diverse array of experts, including the renowned urban designer Jan Gehl, transportation innovator Robin Chase, architect Bjarke Ingels, the interdisciplinary design studio Urban-Think Tank as well as organizations such as the United Nations and community-led initiatives like the alternative policing program in the Kwanlin Dün First Nation in Canada.

References

- Agiani, N. (2023). Building child-friendly cities: A call for action in Indonesia. FAMMI. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/building-child-friendly-cities-call-action-indonesia-fammiindonesia

- Akbulut, N. E., & Tavsanoglu, U. N. (2018). Impacts of environmental factors on zooplankton taxonomic diversity in coastal lagoons in Turkey. TurkishJournal of Zoology, 42, 68–78.

- Ampatzidou, C., Gugerell, K., Constantinescu, T., Devisch, O., Jauschneg, M., & Ber-Ger, M. (2018). All work and no play? Facilitating serious games and gamified applications in participatory urban planning and governance (Vol. 3, pp. 34–46). Urban Plan. doi:10.17645/up.v3i1.1261

- Angelidou, M., Karachaliou, E., Angelidou, T., & Stylianidis, E. (2017). Cultural heritage in smart city environments. International Archives of the Photogrammetry. Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives, 42(2W5), 27–32. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W5-27-2017

- Astapenko, E. V., Klimova, T. V., Molokhina, G. A., & Petrenko, E. A. (2021). Personal characteristics and environmentally responsible behavior of children of the generation alpha with different leisure orientation. In E3S Web of Conferences: Interagromash 2021 (Vol. 273, p. 10042). doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202127310042

- Ataol, Ö., Krishnamurthy, S., & Van Wesemael, P. (2019). Children's participation in urban planning and design: A systematic review. Children, Youth and Environments, 29, 27–47.

- Ataol, K., & van Wesemael, P. J. V. (2019). Children’s participation in urban planning and design: A systematic review. Children, Youth and Environments, 29(2), 27. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.29.2.0027

- Azali, N. N. (2021). Urban-gamification’ as a collaborative placemaking toolkit in nighttime: Let's play the city. In H. Abusaada, A. Elshater, & D. Rodwell (Eds.), Transforming urban nightlife and the development of smart public spaces (pp. 94–113). IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-7998-7004-3.ch007

- Balgaranov, D. (2023). Belgian town redesigns playground with Roblox. https://www.themayor.eu/en/a/view/belgian-town-redesigns-playground-with-roblox-11611.

- Bankler, J. V., Castagnino, V., & Engström, H. (2020). A Game to Support Children’s Participation in Urban Planning. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348446829.

- Bekele, W. B., & Ago, F. Y. (2022). Sample size for interview in qualitative research in social sciences: A guide to novice researchers. Research in Educational Policy and Management.

- Bekele, N. K., Hailu, B. T., & Suryabhagavan, K. V. (2022). Spatial patterns of urban blue-green landscapes on land surface temperature: A case of Addis Ababa. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 4, 100146. doi:10.1016/j.crsust.2022.100146

- Bhardwaj, P., Joseph, C. V., & Bijili, L. (2020). Ikigailand: Gamified Urban Planning Experiences For Improved Participatory Planning: A gamified experience as a tool for town planning. Proceedings of the 11th Indian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

- Biggeri, M., Arciprete, C., & Karkara, R. (2019). Children and Youth Participation in Decision-Making and Research Processes. The Capability Approach, Empowerment and Participation.

- Bonora, L., Martell, F., & Marchi, V. D. (2019). DIGITgame: Gamification as amazing way to learn STEM concepts developing sustainable cities idea in the citizen of the future. Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 14(4). https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JSIS/article/view/4880

- Carroll, P., Witten, K., Kearns, R., & Donovan, P. (2015). Kids in the city: Children's use and experiences of uban neighbourhoods. Journal of Urban Design, 20, 417–436.

- Clarinval, A., Simonofski, A., Henry, J., Vanderose, B., & Dumas, B. (2023). Introducing the smart city to children: Lessons learned from hands-on workshops in classes. Sustainability, 15(3), 1774. doi:10.3390/su15031774

- Constantinescu, T. I., Devisch, O., & Huybrechts, L. (2020). Participation, for whom? The potential of gamified participatory artefacts in uncovering power relations within urban renewal projects. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(5), 319. doi:10.3390/ijgi9050319

- Cordero-Vinueza, V. A., Niekerk, F., & van Dijk, T. (2023). Making child-friendly cities: A socio-spatial literature review. Cities, 137, 104248. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2023.104248

- Davis, D. R. (1998). Technology, unemployment, and relative wages in a global economy. European Economic Review, 42(9), 1613–1633. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(97)00113-X

- de Andrade, B., Poplin, A., & de Sena, Í. S. (2020). Minecraft as a tool for engaging children in urban planning: A case study in Tirol town, Brazil. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 9(3). doi:10.3390/ijgi9030170

- Derr, V., & Kovács, I. G. (2017). How participatory processes impact children and contribute to planning: A case study of neighborhood design from Boulder, Colorado, USA. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 10(1), 29–48. doi:10.1080/17549175.2015.1111925

- Elvstrand, H., & Liisa Närvänen, A. (2016). Children’s own perspectives on participation in leisure-time centers in Sweden. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(6), 496–503. doi:10.12691/education-4-6-10

- Gestalten. (2021). The ideal city: Exploring urban futures. https://space10.com/project/the-ideal-city-exploring-urban-futures/.

- Ghanbri, A. (2014). A comparative study of urban space effect on rate of citizen participation (Case Study: Neighborhoods of Tabriz. University of Tabriz).

- Gheorghe, G., Lates, D., Oprea, C., & Baltatu, C. (2023). Structural and modal analysis in solid works of agricultural plow to choose vibration system at moldboard. Engineering for Rural Development, 22, 872–878.

- Haahtela, T. (2015). Hunt for the origin of allergy - Comparing the Finnish and Russian Karelia. Clinical and Experimental Allergy, 45(5), 891–901.

- Hassan, L., & Hamari, J. (2020). Gameful civic engagement: A review of the literature on gamification of e-participation. Government Information Quarterly, 37. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2020.101461

- Hernández, L., Hernández, V., Neyra, F., & Carrillo, J. (2022). The use of massive online games in game-based learning activities. Revista Innova Educación, 4(3), 7–30. doi:10.35622/j.rie.2022.03.001

- Horelli, L., & Kaaja, M. (2002). Opportunities and constraints of ‘internet-assisted urban planning’ with young people. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(1–2), 191–200. doi:10.1006/jevp.2001.0246

- Huitt, W. (2003). A systems model of human behavior. *Educational Psychology Interactive*.

- Kazhamiakin, R., Marconi, A., Perillo, M., Pistore, M., Valetto, G., Piras, L., … Perri, N. (2015). Using gamification to incentivize sustainable urban mobility. In 2015 IEEE 1st International Smart Cities Conference, ISC2 2015 (Vol. 2). Article 7366196. IEEE. doi:10.1109/ISC2.2015.7366196

- Keeton, R., Mota, N., & Tan, E. (2020). Participatory Workshops as a Tool for Building Inclusivity in New Towns in Africa (Vol. 6, pp. 281–300). SE-Articles. doi:10.7480/rius.6.104

- Khan, A. T., & Zhao, X. (2021). Perceptions of students for a gamification approach: Cities skylines as a pedagogical tool in urban planning education. Responsible AI and Analytics for an Ethical and Inclusive Digitized Society, 763–773.

- Kompas. (2023). Mengejar kota layak anak di Indonesia. https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2023/07/22/en-mengejar-kota-layak-anak-di-indonesia

- Li, M., Ma, S., & Shi, Y. (2023). Examining the effectiveness of gamification as a tool promoting teaching and learning in educational settings: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1253549

- Malone, K. (2013). “The future lies in our hands”: Children as researchers and environmental change agents in designing a child-friendly neighbourhood. Local Environment, 18(3), 372–395. doi:10.1080/13549839.2012.719020

- Mansfield, R. G., Batagol, B., & Raven, R. (2021). “Critical agents of change?”: Opportunities and limits to children’s participation in urban planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 36(2), 170–186. doi:10.1177/0885412220988645

- Marklund, B. B., Backlund, P., & Engstrom, H. (2014). 6th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-GAMES) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. doi:10.1109/VS-Games.2014.7012170

- Martínez-Mesa, J., González-Chica, D. A., Duquia, R. P., Bonamigo, R. R., & Bastos, J. L. (2016). Sampling: how to select participants in my research study? An Bras Dermatol, 91, 326–330.doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165254

- Meier, C., Saorín, J. L., de León, A. B., & Cobos, A. G. (2020). Using the roblox video game engine for creating virtual tours and learning about the sculptural heritage. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 15(20), 268–280. doi:10.3991/ijet.v15i20.16535

- Mohammed, J., & Al-Doski, D. (2020). Ideal city from the perspective of children through participatory planning – Duhok city in Kurdistan region of Iraq. DIE ERDE – Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin, 151, 195–206.

- Moreno, C., Allam, Z., Chabaud, D., Gall, C., & Pratlong, F. (2021). Introducing the “15-minute city”: Sustainability, resilience and place identity in future post-pandemic cities. Smart Cities, doi:10.3390/smartcities

- Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(1), 9–18. doi:10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

- Muehlhaus, S. L., Eghtebas, C., Seifert, N., Schubert, G., Petzold, F., & Klinker, G. (2023). Game.UP: Gamified urban planning participation enhancing exploration, motivation, and interactions. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 39(2), 331–347. doi:10.1080/10447318.2021.2012379

- Münster, S., Georgi, C., Heijne, K., Klamert, K., Noennig, J., Pump, M., … Van Der Meer, H. (2017). How to involve inhabitants in urban design planning by using digital tools? An overview on a state of the art, key challenges, and promising approaches. Procedia Computer Science, 112, 2391–2405. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2017.08.102

- Nordström, M., & Wales, M. (2019). Enhancing urban transformative capacity through children’s participation in planning. Ambio, 48(5), 507–514. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01146-5

- Olszewski, W., & Siegel, R. (2016). Large contests. Econometrica, 84(2), 835–854.

- Olszewski, R., Turek, A., & Laczynski, M. (2016). Urban Gamification as a Source of Information for Spatial Data Analysis and Predictive Participatory Modelling of a City's Development. International Conference on Data Technologies and Applications.

- Özden-Schilling, C. (2023). Chasing scale: the pasts and futures of mobility in electricity and logistics. Mobilities, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2023.2292606

- Özden, S., Arslantürk, E., Senem, M., & As, I. (2023). Gamification in urban planning - Experiencing the future city. Architecture and Planning Journal (APJ), 28(3), doi:10.54729/2789-8547.1239

- Rehm, J., Kailasapillai, S., Larsen, E., Rehm, M. X., Samokhvalov, A. V., Shield, K. D., … Lachenmeier, D. W. (2014). A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. *Addiction, 109, 880–893.

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). *Research methods for business students*. Pearson Education Limited.

- Saunders, M., & Townsend, K. (2016). Reporting and justifying the number of interview participants in organization and workplace research. British Journal of Management, 27(4), 836–852. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12182

- Tiffany, J. S. (2006). Respondent-driven sampling in participatory research contexts: Participant-driven recruitment. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 83, 113–124.

- UN-Habitat. (2021). The Block by Block playbook.

- Urcia, I. A. (2021). Comparisons of adaptations in grounded theory and phenomenology: Selecting the specific qualitative research methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692110454. doi:10.1177/16094069211045474

- Werbach, K. (2014). refers to the paper "(Re)Defining Gamification: A Process Approach" by Kevin Werbach. This paper explores the concept of gamification, proposing a process-oriented definition that focuses on making activities more game-like rather than simply adding game elements.

- Wilson, A., Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Comber, R. (2019). Urban planning, public participation and digital technology: App development as a method of generating citizen involvement in local planning processes. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 46(2), 286–302.

- Yao, S., & Xiaoyan, L. (2017). Exploration on ways of research and construction of Chinese child-friendly city -- A case study of Changsha. Procedia Engineering, 198(September 2016), 699–706. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.07.121

- Zaczkiewicz, A. (2023). The next big thing: Generation Alpha. *Women's Wear Daily*, 14. https://www.wwd.com