ABSTRACT

Workers’ technostress is inevitable with the current omnipresent digital technologies in organisations. While there are numerous empirical studies of work-related technostress, we need a holistic conceptual model that summarises those studies’ findings. Thus, this study aims to build a conceptual model to explain workers' technostress. We gather work-related technostress literature from EBSCO, Web of Science, and Science Direct. Afterwards, we deductively examined those articles using provisional coding and produced a conceptual model. We use Stressors-Strains-Outcomes Model to predefine our codebook. In addition to the model, we also add situational factors that serve as inhibitors that moderating the causal effects of stressors and strains. The proposed model could help organisations to understand technostress phenomenon in their working space. By understanding these, organisations could formulate strategies to manage technostress and limit the impact on their employees. This understanding can be useful to manage unintended risks that technostress introduces to organisations.

1. Introduction

The ubiquitous use of information technology (IT) brings positive and negative consequences for both individuals and organisations (Riedl, Citation2013). To this point, technostress is one negative consequence of IT use (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011; Brod, Citation1982; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Riedl, Citation2013; Tarafdar et al., Citation2007). Technostress emerges as a result of direct interaction between IT artefacts and human beings. It encompasses perception, emotion, and thought in the post-Information System (IS) implementation in organisations and the prevalent use of IT in society (Riedl, Citation2013).

Research shows that technostress could introduce devastating effects for human-beings, examples include anxiety (Hudiburg & Necessary, Citation1996; Salanova et al., Citation2013), exhaustion (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011), and fatigue (Korunka et al., Citation1996; Salanova et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, technostress has tended to decrease workers’ performance (Korunka et al., Citation1996; Tarafdar et al., Citation2010, Citation2011) and produce job dissatisfaction (Arnetz & Wiholm, Citation1997; Korunka et al., Citation1996; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008).

Despite numerous empirical studies on technostress, only very few literature reviews have been conducted (La Torre et al., Citation2019). The recent literature review conducted by La Torre et al. (Citation2019) aimed to explain the definition, symptoms and risks of technostress. Further, they incorporated both work and non-work-related technostress. Other literature reviews focus is on methodologies employed in technostress research such as Riedl (Citation2013), Fischer and Riedl (Citation2017), and Riedl (Citation2013) discussed the use of biological measures in technostress, while Fischer and Riedl (Citation2017) proposed the use of measurement pluralism in technostress research. Along with these, three literature reviews investigated technostress in specific domains, i.e. library users (Sami & Pangannaiah, Citation2006), nurses (Tacy, Citation2016), and accountants (Saganuwan et al., Citation2015).

In addition to previous literature reviews, this study aims to understand the constitution of work-related technostress. Further, this study is not targeting a specific domain, as previous research has been domain-specific. Thus, this study has the potential of increasing the generalisability of this research. The output of our literature review research is the development of a conceptual model of technostress. The model comprises of four components that constitute technostress: causes, strains, inhibitors, and impacts.

We arrange the remainder of the article as follows. Section two provides an overview of technostress, Section three explains our methodology, and section four provides a discussion of our findings. Finally, sections five finishes with conclusions and calls for future research.

2. Technostress definition

The term technostress comes from a clinical psychologist, Craig Brood, in 1984 (Gaudioso et al., Citation2017). Technostress is as a modern disease which impacts people who have difficulties coping with IT in a healthy manner (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011; Tarafdar et al., Citation2007). In other words, technostress is any adverse effects on human behaviours, thoughts, attitudes, and psychology imposed by technology use (Tu et al., Citation2005). Tarafdar et al. (Citation2007) perceive technostress as an adaption problem of individuals due to their incapability to cope up with information technology. In an organisational context, technostress is the stress suffered by end-users due to their engagement with IT in a working environment (Arnetz & Wiholm, Citation1997; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Tarafdar et al., Citation2010).

Ragu-Nathan et al. (Citation2008) characterise technology and workspaces that induce technostress in three characteristics. First, a high dependency on an evolved IS in the working environment. Second, there is a knowledge gap between workers and an evolved IS for performing a task. Third, there is a change in the working environment and culture due to the use of technology. The notion of evolved IS is evident by the introduction of a new version and update of IS to a working space (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008).

Tarafdar et al. (Citation2007) have identified five factors that cause technostress (see ). These factors are called techno-stressors (Gaudioso et al., Citation2017).

Table 1. Techno-stressors (adapted from: (Tarafdar et al., Citation2007))

Karr-Wisniewski and Lu (Citation2010) propose a different definition of technology overload. They describe that technology overload is a situation where the excessive use of technology imposes adverse effects (Karr-Wisniewski & Lu, Citation2010). Further, they also identify three salient dimensions of technology overload: system feature overload, information overload, and communication overload (Karr-Wisniewski & Lu, Citation2010). provides definitions of these three dimensions.

Table 2. Definitions of technology overload dimensions (adapted from: (Karr-Wisniewski & Lu, Citation2010))

With the prevalence of information technology (IT) implementation in organisations, it is of critical importance that the presence and impact of techno-stressors be examined. The next section outlines the literature review method employed to identify and examine prior research on technostress.

3. Methodology

This section describes the approach for literature gathering by adopting an approach proposed by (Wolfswinkel et al., Citation2013). The approach consists of four steps: define, search, select and analyse (see ).

3.1. Define

This step focuses on developing a search strategy by 1) outlining inclusion/exclusion criteria, 2) determining database sources, 3) defining search parameters. lists the inclusion rules used in this study. For the database sources, this study uses EBSCO, Science Direct, and Web of Science following a systematic review process as outlined by (Han et al., Citation2018). In terms of search parameter, we used ‘technostress’ as the keyword for our search; technostress has been used as a keyword in previous literature reviews i.e. (Fischer & Riedl, Citation2015, Citation2017; Riedl, Citation2013; La Torre et al., Citation2019).

3.2. Search

In this step we conducted the search. The results were filtered using the inclusion rules available in the selected database. Further, the results were examined in the next step to select the relevant literature for this study. From the actual search, we obtained 64, 296, and 118 results from EBSCO, Science Direct and Web of Science respectively. In total, we got 478 search results.

3.3. Select

In this step, we show how we select our literature. There were two steps. The first was the duplication checking. This was necessary because the literature came from different database sources. (Step Select) presents the result of the duplication-checking procedure. shows that the number of duplicated titles was 134. The second step was relevancy checking. Here, to ensure manageability, we examined the literature in a stepwise procedure. Procedures were 1) title reading, 2) abstract reading, and 3) full-text reading. also provides the result of relevancy checking.

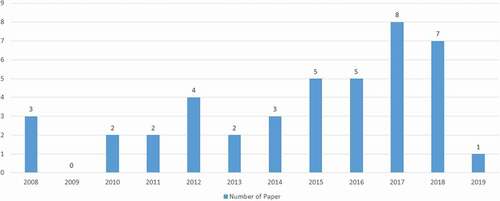

For title reading, the relevancy was assessed based on the title of the paper. Here, since this study focus on workers’ technostress, the title should represent these topics. From title checking, we excluded 101 papers. For abstract reading, this study focuses on worker stress related to IT used. Therefore, we only included any relevant papers for a full reading. From the abstract reading, there were 42 papers related to the stress imposed by IT on workers. The distribution of papers in technostress is available in .

3.4. Analyse

In this section, we analyse the literature that we have obtained previously. For this purpose, we used provisional coding (Miles et al., Citation2014). Provisional coding requires us to provide a ‘start-list’ of researcher-generated codes (Miles et al., Citation2014, p. 10). Afterwards, we use these predefined codes to analyse our literature. Provisional coding itself is helpful to confirm previous research and investigations (Miles et al., Citation2014). For doing so, the coding scheme that we used for our provisional coding is available in . The predefined codes are an extension of the Stressor-Strain-Outcome Model (Koeske & Koeske, Citation1993). The model comprises three variables: stress, strain, and outcome. In general, the model exhibits a causal diagram among variables. More specifically, stressors directly cause strain, which subsequently contributes to a specific outcome. Reviewing the literature allowed us to update our codes and adapted the model; for example, we also add a situational variable. Situational factors are any conditions that either weaken or strengthen the effects of potential stressors (Brown et al., Citation2014; Turel & Gaudioso, Citation2018). Here, the situational factors act as inhibitors between stressors, strain and outcome. Our final model is available in section 4.5.

Table 3. Code scheme for technostress

The sample of our coding scheme is available in . We have eight coding examples from literature. Each example represents each coding scheme such as techno-stressor, strain, impact, and inhibitor.

Table 4. Example of text from literature

4. Findings

In this section, we explain what we have found from the literature. That is, techno-stressors, strains, inhibitors, and impacts. At the end of this section, we draw a conceptual model of technostress.

4.1. Techno-stressors: the causes of technostress

lists factors introducing technostress in organisations, which we identify as techno-stressors. We can classify the causes of technostress in to two categories. The first category is the causes that related to system performance such as system breakdown, usability issues, and security issues. System breakdown refers to any IT malfunctions experienced by users; one form of system breakdown is an error message (Riedl et al., Citation2012). Usability issues refers to how well users can use the functionality provided by the system (Nielsen, Citation1993). Some examples of usability issues are related to system efficiency, effectiveness and learnability (Benyon, Citation2010; Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014). Security issues refers to any threats or attacks that allow destruction, unauthorised access, disruption, disclosure or modification of information and information systems (Maimbo, Citation2014). To ensure information security, organisations implement policies on how to use information systems (Feruza & Kim, Citation2007), One type of IT security policies would be password policies (Cavusoglu et al., Citation2004; Siponen & Oinas-Kukkonen, Citation2007). Here, working with multiple systems, users need to remember different usernames and passwords, which can lead to technostress (Kwanya et al., Citation2012).

Table 5. Techno-stressors

The second category of causes is not related to system performance. These causes mostly relate to how workers use IT in their working space. Some of these techno-stressors are accessibility (Hung et al., Citation2015), dependency on technology (Liu et al., Citation2019; Shu et al., Citation2011), and techno-uncertainty (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011). Hung et al. (Citation2015) define accessibility as the ease of access to communication technologies. By getting access to communication technologies, workers could be quickly interrupted by external sources (communication overload) (Hung et al., Citation2015). Also, these technologies force workers to work faster and extend their work (techno-overload) (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Tarafdar et al., Citation2010, Citation2007). Similar to accessibility, flexibility allows one to reach any workers anywhere and anytime (techno-invasion) (Kim et al., Citation2015; Yun et al., Citation2012). Techno-invasion blurs the distinction between work and personal life due to constant connectivity via technology (Tarafdar et al., Citation2010). This definition of techno-invasion is expressed differently by Ayyagari et al. (Citation2011) who describe it as work-home conflict.

Dependency on technology also contributes to technostress (Liu et al., Citation2019; Shu et al., Citation2011). It defines the level of worker dependency on technology to operationalise their works (Liu et al., Citation2019; Shu et al., Citation2011). High level of dependency increases the possibility of workers facing some problems related to the technology (i.e., errors, complexity), which introduces technostress (Shu et al., Citation2011). Another techno-stressor is techno-uncertainty (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011). The study by Ayyagari et al. (Citation2011) aligns with prior research studies (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Tarafdar et al., Citation2010, Citation2007) which identify techno-uncertainty as one of the techno-stressors. Techno-uncertainty is a condition where the constant changing of technology imposes workers’ anxiety on their IT capabilities (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011).

Al-Fudail and Mellar (Citation2008) also found that the lack of fit between technology demand and workers’ ability, and between organisational supply and worker’s need will induce worker technostress. The example of lack of fit between demand and ability is as follows. Suppose an innovative technology requires an essential level of worker IT capabilities. However, since a worker has a low level of IT capabilities, the lack of fit between demand and ability occurs. This lack of fit introduces technostress on the worker. The illustration of the lack of fit between supply and need is as follows. Since the worker possesses a low level of IT capabilities, the worker needs some supports such as training from the organisation. However, the organisation does not provide adequate training for the worker. Thereby, this will hinder worker improvement, which leads to technostress.

4.2. Strain: the manifestation of technostress

In terms of technostress, some studies have identified strains that represent an individual response to techno stressors (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011). There are several strains expressed clearly in some studies (see ). We classify the strains into two categories: emotional strain and physical strain.

Table 6. Strains due to IT use

Emotional strain represents the psychological state of workers. An example of emotional strain is emotional exhaustion (Brown et al., Citation2014). Emotional exhaustion is a condition when a worker feels emotionally overextended, irritable and fatigued (Brown et al., Citation2014). The other strains are harmful emotion, anger and anxiety respectively (Lee, Citation2016). Another strain is work exhaustion (Kim et al., Citation2015). Kim et al. (Citation2015) define work exhaustion as ‘the depletion of emotional and mental energy that is necessary to meet the needs of duties in the workplace’ (p. 256).

Physical strain captures the physical state of workers such as eyestrain and high level of cortisol. Previous research shows that the level of cortisol increased dramatically when humans experienced technostress (Riedl et al., Citation2012).

Despite the aim to investigate technostress in working space, our finding shows that the vast majority (76%) of previous research incorporates technostress in general terms. They do not specify what kind of strains manifested. For example, (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011) incorporate variable ‘strain’ in their study. Different examples are exhibited by (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Shu et al., Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2008) which include ‘technostress’ as a variable in their study.

4.3. Inhibitors of technostress

The section discusses the inhibitors of technostress. The current literature has found that why workers experience technostress different from each other may be explained by variables on some conditions. One could classify these conditions as either individual condition or organisational setting. Individual condition refers to conditions which attach to personal such as educational level (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008), self-efficacy (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Shu et al., Citation2011), and technology dependency (Shu et al., Citation2011). Technology self-efficacy indicates workers’ confidence level using technology to perform a particular task (Shu et al., Citation2011). While technology dependency represents workers’ dependency on technology to complete a task. (Liu et al., Citation2019). There are conditions where workers experience lower technostress level. First is when the worker has a higher educational level (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008). Second is when the worker has higher technology self-efficacy (Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Shu et al., Citation2011). The third is when the worker has a lower level of technology dependency (Shu et al., Citation2011). Organisational setting denotes how an organisation achieves its goal (Wang et al., Citation2008). Further, (Wang et al., Citation2008) classified two internal organisational environments based on 1) power centralisation and 2) innovation in the organisation. Their study exhibits that organisations with high power centralisation and high innovation impose the highest level of overall technostress (Wang et al., Citation2008).

Technostress literature has investigated some factors that inhibit technostress (see ). From , we can classify technostress inhibitors into two categories: technology-related inhibitors and non-technology-related inhibitors. Technology-related inhibitors are any factors that reduce technostress on workers based on technical characteristics. Some technology-related inhibitors are reliability (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011), user experience (Hung et al., Citation2015), and usefulness (Lee, Citation2016). The reliability of technology helps to reduce the level of work overload (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011). User experience familiarity with other technologies contributes to lowering technology complexity faced by workers (Hung et al., Citation2015). Also, when workers find that the technology is useful, it helps them to be less angry (Lee, Citation2016).

Table 7. Technostress inhibitors

Non-technology-related inhibitors are any factors that help in minimise technostress on workers based on non-technology characteristics. One of the inhibitors that have received attention in previous studies is technology self-efficacy (c.f. Liu et al., Citation2019; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Shu et al., Citation2011). Technology self-efficacy helps individuals in responding to stress when stressors occur (Tams et al., Citation2018). Further, Shu et al. (Citation2011) have found that employees with higher self-efficacy have a willingness to overcome problems caused by IT as well as to embrace positive coping behaviour. Organisations also play an essential role to help workers overcome technostress. For example, organisations which encourage end-users to participate in the introduction and development of new technology (involvement facilitation) help to lessen technostress (Kim et al., Citation2015). Another example is strengthening segmentation culture in an organisation aids workers to achieve work-life conflict balance (Kim et al., Citation2015; Yun et al., Citation2012).

4.4. The impact of technostress

Previous studies have found that technostress has an impact on personal and organisational related issues. highlights some impacts of technostress.

Table 8. Impact of technostress

The most widely discussed technostress impacts are productivity (c.f. Hung et al., Citation2015; Karr-Wisniewski & Lu, Citation2010; Tarafdar et al., Citation2010) and job satisfaction (c.f. Kim et al., Citation2015; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Tak & Park, Citation2016; Yin et al., Citation2018). In terms of productivity, Hung et al. (Citation2015) use the law of diminishing theory. That is, describe that while the use of technology could boost productivity to some extent, the extreme utilisation of technology could produce an adverse effect. Job satisfaction is defined as an emotional reaction to the job (An et al., Citation2016), resulting from the appraisal of job experience (Locke, Citation1976). With the high level of technostress, workers felt less satisfied on their job (Kim et al., Citation2015; Ragu-Nathan et al., Citation2008; Tak & Park, Citation2016; Yin et al., Citation2018). Further, technostress also hinders employee engagement in an organisation (Okolo et al., Citation2018), and it increases user resistance in using the new technology (Yun et al., Citation2012).

4.5. Work-related technostress: a conceptual model

Based on the discussion above, we proposed a conceptual model of technostress. The model constitutes four components: stressors, strains, inhibitors and impacts. The model is available in . The model represents a causal effect diagram between its components. Techno-stressors exemplify the causes of technostress in working spaces. The use of technology for work purposes introduces technostress. One example is when workers face with some usability issues (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014). The software may contain hidden functionalities that mandate a user to memorise how to operate them (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014). Another example happens in Lotus Notes. In this software, a user can book an appointment schedule. However, to reschedule the previously entered schedule is not easy. A user needs to deal with a sophisticated graphical user interface, which shows how usability issues can produce technostress (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014).

The strain is the second construct of our model. A strain is individual responses to technostress (Ayyagari et al., Citation2011). Strain can manifest as an output of constant techno-stress exposure. For example, consider the Lotus Notes case. A user continuously receives error messages because he/she enters wrong inputs in the weak graphical user interface system. As he/she cannot figure out how to fix these errors, this user experience technostress which strain is emotionally exhausting.

‘The others who were present discussed the problem, which apparently is common, and they described it as “annoying.” The same problem occurred again later that day when the staff secretary tried to reschedule an appointment, and thus needed to edit an already existing booking’. (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014, p. 195)

The third construct is inhibitors which act as situational factors that either reduce or increase the causal effect between stressors and strains (Brown et al., Citation2014; Turel & Gaudioso, Citation2018). In the case of Lotus Notes, technical support provision plays a crucial role in reducing stress. Here, the technical support helps the user to alleviate the problem he/she experiences (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014). Hence, we could see this as an effort to reduce ‘technostress’ strain.

The fourth construct is impact. The impact is the outcome of technostress. Having a negative experience using technology in working space may affect the individual (Farler & Broady-Preston, Citation2012). In the case of Lotus Notes, as a user experience unsolved error regularly, he/she loses the intention to use IS. Hence, the user prefers to use the telephone instead of using Lotus Notes (Sellberg & Susi, Citation2014).

Overall, this conceptual model is useful for organisations to raise awareness of technostress – especially, techno-stressors, strains, inhibitors, and impacts. An organisation can anticipate a potential techno-stressor introduced by technology. Next, the organisation can develop a relevant strategy to minimise unintended impacts of the technology. The strategy itself can stem from the inhibitors, which research suggests can help avoid the strains manifesting. If an organisation could avoid strains manifesting, then it could eliminate the ‘technostress’ impact.

5. Conclusion

This study presents a conceptual model of technostress (see ). Technostress itself is a complex phenomenon that has substantial impacts on Information Systems (IS) users. Despite its complexity and impact, technostress has been underserved in the IS research. Hence, technostress is a spacious research area that needs unpacking in order to better understand its impact on IS users. To fill this gap in knowledge, our conceptual model explains that techno-uncertainty, techno-complexity, and technology dependency are some causes of technostress. With these causes, workers experience strains such as emotional exhaustion and some negative emotions (anger and anxiety). Further, different individual workers exhibit varying levels of technostress which is moderated by some inhibitors such as technology self-efficacy and user experience. Consequently, some impacts reduce workers’ productivity and job satisfaction. Further studies could explore more on these type of strains and determine an inhibitor ranking to help organisations minimise technostress impact effectively.

This research contributes to both theory and practice. This study contributes to the technostress body of knowledge in three main ways. First, we provide an alternate view by integrating techno-stressors, strains, inhibitors, and impacts in a conceptual model. Second, this study focuses on technostress in a working environment. Third, unlike previous literature review, which targets a domain, this study targets non-specific domain.

In terms of practical contributions, this study presents a conceptual model that could be used by organisations to understand the technostress phenomenon in their workplace. By understanding these constructs, their attributes, and inter-construct relationships, organisations can develop measures to manage technostress and limit the impact on their employees.

This study has two limitations. First, the number of papers is limited. Further research should incorporate more papers from various database sources. Second, this study only covered the causal effects of technostress and did not incorporate coping mechanisms. Further studies should encompass several coping mechanisms used to minimise technostress.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alam, M.A. (2016). Techno-stress and productivity: Survey evidence from the aviation industry. Journal of Air Transport Management, 50, 62–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2015.10.003

- Al-Fudail, M., & Mellar, H. (2008). Investigating teacher stress when using technology. Computers & Education, 51(3), 1103–1110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.11.004

- An, M., Colarelli, S.M., O’Brien, K., & Boyajian, M.E. (2016). Why we need more nature at work: Effects of natural elements and sunlight on employee mental health and work attitudes. Plos One, 11(5), e0155614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155614

- Arnetz, B.B., & Wiholm, C. (1997). Technological stress: Psychophysiological symptomps in modern offices. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 43(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00083-4

- Ayyagari, R., Grover, V., & Purvis, R. (2011). Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Quarterly, 35 (4), 831–858. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41409963

- Benyon, D. (2010). Designing interactive systems: A comprehensive guide to HCI and interactive design (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Boonjing, V., & Chanvarasuth, P. (2017). Risk of overusing mobile phones: Technostress effect. Procedia Computer Science, 111, 196–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.06.053

- Brod, C. (1982). Managing technostress: Optimizing the use of computer technology. The Personnel Journal, 61(10), 753–757. https://search.proquest.com/docview/78091146/D8186C5AFCC474FPQ/1?accountid=201395

- Brown, R., Duck, J., & Jimmieson, N. (2014). E-mail in the workplace: The role of stress appraisals and normative response pressure in the relationship between E-mail stressors and employee strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 21(4), 325–347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037464

- Bucher, E., Fieseler, C., & Suphan, A. (2013). The stress potential of social media in the workplace. Information, Communication & Society, 16(10), 1639–1667. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.710245

- Carlotto, M.S., Wendt, G.W., & Jones, A.P. (2017). Technostress, career commitment, satisfaction with life, and work-family interaction among workers in information and communication technologies. Actualidades En Psicología, 31(122), 91–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15517/ap.v31i122.22729

- Cavusoglu, H., Mishra, B., & Raghunathan, S. (2004). A model for evaluating IT security investments. Communications of the ACM, 47(7), 87–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1005817.1005828

- Farler, L., & Broady-Preston, J. (2012). Workplace stress in libraries: A case study. Aslib Proceedings, 64(3), 225–240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00012531211244509

- Feruza, S., & Kim, T.-H. (2007). IT security review: Privacy, protection, access control, assurance and system security. International Journal of Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering, 2(2), 17-32. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/IT-Security-Review%3A-Privacy%2C-Protection%2C-Access-and-Feruza-Kim/e44fb481ebf5e3886cb3556d2354a1f42cac80ce

- Fischer, T., & Riedl, R. (2015). The status quo of neurophysiology in organizational technostress research: A review of studies published from 1978 to 2015. In F. D. Davis, R. Riedl, J. vom Brocke, P. Léger, A. B. Randolph (Eds.), Lecture notes in information systems and neuroscience (Vol. 10) (pp. 9-17). Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation ( IS and Neu). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18702-0_2

- Fischer, T., & Riedl, R. (2017). Technostress Research: A Nurturing Ground for Measurement Pluralism? Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 40, 17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.04017

- Fuglseth, A.M., & Sørebø, Ø. (2014). The effects of technostress within the context of employee use of ICT. Computers in Human Behavior, 40, 161–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.040

- Gaudioso, F., Turel, O., & Galimberti, C. (2017). The mediating roles of strain facets and coping strategies in translating techno-stressors into adverse job outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 189–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.041

- Han, H., Xu, H., & Chen, H. (2018). Social commerce: A systematic review and data synthesis. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 30, 38–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.05.005

- Hudiburg, R.A., & Necessary, J.R. (1996). Coping with computer-stress. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 15(2), 113–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/HB85-U4FF-34N3-H6EK

- Hung, W.-H., Chen, K., & Lin, C.-P. (2015). Does the proactive personality mitigate the adverse effect of technostress on productivity in the mobile environment? Telematics and Informatics, 32(1), 143–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2014.06.002

- Jena, R.K. (2015). Technostress in ICT enabled collaborative learning environment: An empirical study among Indian academician. Computers in Human Behavior, 51, 1116–1123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.020

- Karr-Wisniewski, P., & Lu, Y. (2010). When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1061–1072. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.008

- Kim, H.J., Lee, C.C., Yun, H., & Shin, I.K. (2015). An examination of work exhaustion in the mobile enterprise environment. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 100, 255–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.07.009

- Koeske, G.F., & Koeske, R.D. (1993). A preliminary test of a stress-strain-outcome model for reconceptualizing the burnout phenomenon. Journal of Social Service Research, 17(3–4), 107–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v17n03_06

- Korunka, C., Huemer, K.H., Litschauer, B., Karetta, B., & Kafka-Lützow, A. (1996). Working with new technologies: Hormone excretion as an indicator for sustained arousal. A pilot study. Biological Psychology, 42(3), 439–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(95)05172-4

- Kummer, T.-F., Recker, J., & Bick, M. (2017). Technology-induced anxiety: Manifestations, cultural influences, and its effect on the adoption of sensor-based technology in German and Australian hospitals. Information & Management, 54(1), 73-89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.04.002

- Kwanya, T., Stilwell, C., & Underwood, P. (2012). Technostress and technolust: Coping mechanisms among academic librarians in Eastern and Southern Africa. Proceedings of the International Conference on Ict Management for Global Competitiveness and Economic Growth in Emerging Economies (Ictm 2012), Wroclaw, Poland (pp. 302–313). https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/41787322/Techno-stress_and_techno-lust_coping_mec20160130-11859-m103wv.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1551106300&Signature=EzzGyGGrfgwE%2BQsslXov7c8Dqp0%3D&response-content-disposition=inlin

- La Torre, G., Esposito, A., Sciarra, I., & Chiappetta, M. (2019). Definition, symptoms and risk of techno-stress: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 92(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-018-1352-1

- Lee, J. (2016). Does stress from cell phone use increase negative emotions at work? Social Behavior and Personality, 44(5), 705–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.5.705

- Liu, C.-F., Cheng, T.-J., & Chen, C.-T. (2019). Exploring the factors that influence physician technostress from using mobile electronic medical records. Informatics for Health and Social Care, 44(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2017.1364250

- Locke, E.A. (1976). Nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Hand-book of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 513–553). Rand-McNally.

- Maimbo, C. (2014). Exploring the applicability of SIEM technology in IT security. Auckland University of Technology.

- Miles, M., Huberman, A.M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis a methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE. http://www.ghbook.ir/index.php?name=فرهنگ و رسانه های نوین&option=com_dbook&task=readonline&book_id=13650&page=73&chkhashk=ED9C9491B4&Itemid=218&lang=fa&tmpl=component

- Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability engineering. Academic Press.

- Norulkamar, U., Ahmad, U., & Amin, S.M. (2012). The dimensions of technostress among academic librarians. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 65, 266–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.121

- Okolo, D., Kamarudin, S., Norulkamar, U., & Ahmad, U. (2018). An exploration of the relationship between technostress, employee engagement and job design from the Nigerian banking employee’s perspective. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 6(4), 511–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25019/MDKE/6.4.01

- Ragu-Nathan, T.S., Tarafdar, M., Ragu-Nathan, B.S., & Tu, Q. (2008). The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and validation. Information Systems Research, 19(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0165

- Riedl, R. (2013). On the biology of technostress: Literature review and research Agenda. The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems, 44(1), 18–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2436239.2436242

- Riedl, R., Kindermann, H., Auinger, A., & Javor, A. (2012). Technostress from a neurobiological perspective system breakdown increases the stress hormone cortisol in computer users the authors. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 4(2), 61–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-012-0207-7

- Saganuwan, M.U., Norulkamar, U., Ahmad, U., Khairuzzaman, W., & Ismail, W. (2015). Conceptual framework: AIS technostress and its effect on professionals’ job outcomes. Asian Social Science, 11(5), 97-107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n5p97

- Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Cifre, E. (2013). The dark side of technologies: Technostress among users of information and communication technologies. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 422–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.680460

- Sami, L.K., & Pangannaiah, N.B. (2006). A literature survey on the effect of information technology on library users. Library Review, 55(7), 429–439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530610682146

- Sellberg, C., & Susi, T. (2014). Technostress in the office: A distributed cognition perspective on human-technology interaction. Cognition, Technology and Work, 6(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-013-0256-9

- Shu, Q., Tu, Q., & Wang, K. (2011). The impact of computer self-efficacy and technology dependence on computer-related technostress: A social cognitive theory perspective. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 27(10), 923–939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2011.555313

- Siponen, M.T., & Oinas-Kukkonen, H. (2007). A review of information security issues and respective research contributions. The DATA BASE for Advances in Information Systems, 38(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1216218.1216224

- Tacy, J.W. (2016). Technostress: A concept analysis. On - Line Journal of Nursing Informatics, 20(2), 1–9. https://search.proquest.com/openview/954610a584f785a9ee6f02f151f7e893/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2034896

- Tak, S., & Park, S. (2016). A study of the connected smart worker’s techno-stress. In Procedia Computer Science, 91, 725–733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.07.065

- Tams, S., Thatcher, J.B., & Grover, V. (2018). Concentration, competence, confidence, and capture: An experimental study of age, interruption-based technostress, and task performance. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 19(9), 857–908. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00511

- Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, B.S., & Ragu-Nathan, T.S. (2007). The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240109

- Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., & Ragu-Nathan, T.S. (2010). Impact of technostress on end-user satisfaction and performance. Journal of Management Information Systems, 27(3), 303–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222270311

- Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, T.S., & Ragu-Nathan, B.S. (2011). Crossing to the dark side: Examining creators, outcomes, and inhibitors of technostress. Communications of the ACM, 54(9), 113–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1995376.1995403

- Tu, Q., Wang, K., & Shu, Q. (2005). Computer-related technostress in China. Communication of the ACM, 48 (4), 77–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/1053291.1053323

- Turel, O., & Gaudioso, F. (2018). Techno-stressors, distress and strain: The roles of leadership and competitive climates. Cognition, Technology & Work, 20(2), 309–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10111-018-0461-7

- Wang, K., Shu, Q., & Tu, Q. (2008). Technostress under different organizational environments: An empirical investigation. Computers in Human Behavior, 24 (6), 3002–3013. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.05.007

- Wolfswinkel, J.F., Furtmueller, E., & Wilderom, C.P.M. (2013). Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. European Journal of Information Systems, 22(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.51

- Yang, R.-J., Yang, J.-Y., Yuan, H.-R., & Li, J.-T. (2017). Techno-stress of teachers: An empirical investigation from China. In The 3rd International Conference on Education and Social Development (ICESD 2017), Xi'an, China. http://www.dpi-proceedings.com/index.php/dtssehs/article/viewFile/11619/11161

- Yin, P., Ou, C.X., Davison, R.M., & Wu, J. (2018). Coping with mobile technology overload in the workplace. Internet Research, 28(5), 1189–1212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0016

- Yun, H., Kettinger, W.J., & Lee, C.C. (2012). A new open door: The smartphone’s impact on work-to-life conflict, stress, and resistance. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 16(4), 121–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415160405

- Zhou, G., Xu, K., & Liao, S.S.Y. (2013). Do starting and ending effects in fixed-price group-buying differ? Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 12(2), 78–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2012.11.006