ABSTRACT

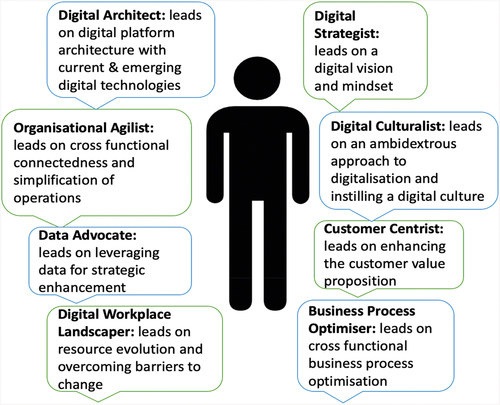

Digital Transformation has generated much research and curiosity recently, with the COVID-19 global pandemic accelerating its pace across all industry sectors. Current literature has not adequately provided a comprehensive understanding of Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL). The objective of this research is to explore the characteristics of DTL by undertaking a comprehensive review of Information Systems literature using a systematic procedure of identifying and coding 87 research papers, resulting in 600 coded excerpts, capturing the ‘who’ and ‘what’ of DTL. Our analysis identifies eight DTL characteristics, namely: digital strategist, digital culturalist, digital architect, customer centrist, organisational agilist, data advocate, business process optimiser and digital workplace landscaper. We discuss mapping the DTL characteristics to c-suite roles, presenting a taxonomy from the literature, of interest to both academics and practitioners. This research raises the awareness of the concept of DTL characteristics, especially amongst those in positions of leadership and decision making authority.

1 Introduction

Digital Transformation has generated much research and curiosity in recent years from both an academic and practitioner perspective, not least in Information Systems (IS) research. Indeed, in 2020, the current COVID-19 global pandemic is accelerating the pace of digital transformation within organisations of all types and sizes, across all industry sectors; however, these organisations are struggling to adapt to the scale and depth of the change required, along with the decision-making urgency. Therefore, the volume of commentary around digital transformation is set to increase significantly. To date, systematic reviews of digital transformation, focusing on its meaning, importance and effects on an organisation, while also highlighting the inconsistencies that exist in current literature, emanating from the definition of the term digital transformation, have been conducted (c.f. Vial Citation2019, Besson & Rowe, Citation2012; Henriette et al., Citation2015; Morakanyane et al., Citation2017; Piccinini et al., Citation2015). However, it is hard to find a universally shared definition of digital transformation from the literature (Hansen et al., Citation2011; El Sawy et al., Citation2016). Like all types of change programmes, digital transformation can be understood to alter the people, process, technology and data components of an organisation (Hansen et al. Citation2015, Dremel et al., Citation2017). The motivation for introducing a digital transformation programme can be multi-faceted, but, many digital transformation programmes are centred around changing the organisation’s structure and business model in order to serve existing customers more efficiently and reach new customers more effectively (Haffke et al., Citation2016; El Sawy et al., Citation2016). This is achieved through leveraging current and emerging digital technologies.

So, what is leadership in digital transformation? So far not much is known about the role leadership plays in a digital transformation undertaking and current literature has not adequately provided a comprehensive understanding of Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL). Where literature does exist, DTL is understood as ‘doing the right things for the strategic success of digitalization for the enterprise and its business ecosystem’ (El Sawy et al., Citation2016, p. 142). Industry analysis suggests that less than 30% of digital transformation programmes succeed (c.f. McKinsey, Citation2018); further revealing that one of five categories of success factor to ensure digital transformation success is ‘having the right, digital-savvy leaders in place’ (p. 4). However, what does this really mean? The emergence of new leadership roles (Haffke et al., Citation2016; Horlacher et al., Citation2016) including the creation of a Chief Digital Officer (CDO) has been highlighted as being significant (Horlacher et al., Citation2016; Singh & Hess, Citation2017). So while achieving transformation success is linked to having certain digital-savvy leaders in place, less than one-third of organisations have engaged a CDO to support their transformations (McKinsey, Citation2018).Notwithstanding this, the emergence of the CDO represents the widespread view of the need to appoint a specialist to take charge of digitally transforming the business (Haffke et al., Citation2016). So while decisions need to be made around digital transformation, as it is deployed across organisations, it is the leadership that must decide on the who and the what of these digital transformation programme implementations. We must therefore understand what is critically important and we must appreciate what the leadership of a digital transformation programme are focusing on (c.f. Heavin & Power, Citation2018).

Irrespective of who leads on a digital transformation programme, as regards their role or title, it is more important to appreciate the DTL characteristics that are required to drive digital transformation in organisations. Should the CDO be the only individual in the c-suite leading on digital transformation? Are there other executive leadership types that are also suited to this role such as the CEO, CIO, CDAO (Chief Data & Analytics Officer) or CTO, who may be equipped with the necessary mandate to deliver change and overcome challenges that they will undoubtedly face during a digital transformation programme? Therefore, the objective of this research is to explore the characteristics of DTL, as reported in Information Systems (IS) literature. In order to fulfil this objective, we pose the following research question.

Research Question: What are the characteristics associated with Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL)?

To answer this research question, we undertake a comprehensive review of Information Systems literature in order to develop an understanding of DTL as currently reported in the literature. The remainder of his paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we focus on the approach followed to analyse the literature. This is followed by a data analysis section within which we present our answer to the research question in the form of eight characteristics of Digital Transformation Leadership. We then discuss an initial mapping of the DTL characteristics to c-suite roles, and present a taxonomy emerging from the literature analysis. The paper concludes with a summary and future research directions.

2 Research methodology

For the purposes of the literature review undertaken in this research, the literature search focused on the journals categorised under ‘Information Management’ in the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) list, along with the major IS conferences listed in the AIS eLibrary. The keyword search criterion of having ‘digital transformation’ and ‘leadership’ or ‘digital leadership’ and ‘digital strategy’ and ‘digital transformation’, in either the title or abstract, was applied on June 2019 and December 2020. This was followed by a thorough review of the references and citations of the research papers returned from both of these searches. This resulted in a total of 165 research papers being reviewed. 78 research papers were excluded as they were either off-topic and/or conceptual/theoretical in nature. Therefore, 87 research papers that explicitly mentioned digital transformation and leadership, and were scientific peer-reviewed empirical research papers were analysed.

Given that the objective of this study is to generate a set of Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL) characteristics, content analysis was deemed an appropriate analysis approach. Content analysis is a frequently used technique when analysing texts (written or visual sources), especially where the meaning of the text is relatively straightforward and obvious (c.f. Alhassan et al., Citation2018; Myers, Citation2009). A structured approach to analysis is pivotal in conducting content analysis; this requires the researcher to code the texts systematically. Therefore, through searching for “structures and patterned regularities in the text” (Myers, Citation2009), the researcher applies a code to a unit of text that seeks to demonstrate the meaning of that text. Once coded, the resulting output can be both quantified and interpreted. Therefore, in effect, content analysis is best understood as “a quantitative method of analysing the content of qualitative data” (Myers, Citation2009, p. 172). In this study, we used eight coding steps (c.f. Finney and Corbett, Citation2007; Alhassan et al., Citation2018). These steps constitute data collection and coding procedures which enable researchers to ensure clarity and transparency in the processes undertaken. The steps and associated decisions are presented in below.

Table 1. Eight Coding Steps (source: Alhassan et al., Citation2019).

Due to the exploratory nature of this research, it was decided to adopt an open-coding analysis technique, which is usually the first coding procedure undertaken on the data, as part of a grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Vollstedt & Rezat, Citation2019). Open coding analysis is widely applied in conducting content analysis for a set of publications (Finney and Corbett, 2007; Alhassan et al., Citation2018; Goode & Gregor, Citation2009) and is described as “the process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualising, and categorising data” (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990, p. 61). Open coding is a process that aims to identify the concepts or key ideas that may be hidden within data (text of each research paper in this case) and are likely to be related to a phenomenon of interest (the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ of DTL in this case). The concepts and categories that are generated as part of the open coding stage are the result of “an intensive analysis of the data ”where a “core idea” is established and “a code” is developed to describe it (Vollstedt & Rezat, Citation2019, p. 86). These codes can be grouped and labelled to form concepts which can also be further grouped and labelled to form categories.

In this research, analysis was conducted at the level of the entire research paper in order to identify which of the research papers were addressing DTL related concepts. More specifically, thereafter, the focus of the coding and analysis was on the ‘who’ (referring to the leader or leadership function in digital transformation) and the ‘what’ (referring to the activities of digital transformation leadership). Where the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ were present in the same sentence, it was coded, following an inductive coding approach. This ‘low-level coding’ approach adopted here ensures that ‘the data are examined minutely’ (Urquhart et al., Citation2010, p,369) and the chain of evidence provided (as is presented throughout Section 3.2) ensures that the conceptualisation work undertaken (to generate the DTL characteristics) is well supported by multiple instances (excerpts of text) from the research papers analysed.

Through an open coding process, the emergent concepts were further grouped into categories, thereby creating eight DTL characteristics. For this research, it was decided to code for frequency in order to gain a deeper insight into the concepts that emerged. The following translation rules were established and applied during the coding procedure: (i) all research papers were read the first time in order to code for the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ of DTL; (ii) all the concepts that emerged from the research papers were compared to identify similarities and differences in order to group them together in categories; (iii) once all the research papers had been coded, the researchers examined the concepts that emerged and their properties within the actual text in order to ensure that they reflected the meaning of the text and that they were being related to the correct category. Following the above procedure, we ended up with eight categories, emerging from 142 concepts, which linked back to the 600 coded excerpts (the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ of DTL) from the 87 research papers coded. presents a sample of the open coding undertaken as part of this research. A more detailed open coding picture is provided in Section 3.2 for each of the eight DTL characteristics.

Table 2. Open Coding Examples of DTL Characteristics.

3 Data analysis

3.1 Overview

As mentioned in the previous section, the 87 research papers were selected from the journals categorised under ‘Information Management’ in the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) list, along with the major IS conferences listed in the AIS eLibrary. These papers cover the period from 2001 to 2020. 2003 was the year of the first published research paper identified (based on the search keywords used). The list of papers is provided in below.

Table 3. Journal and Conference Papers Analysed (2001–2020).

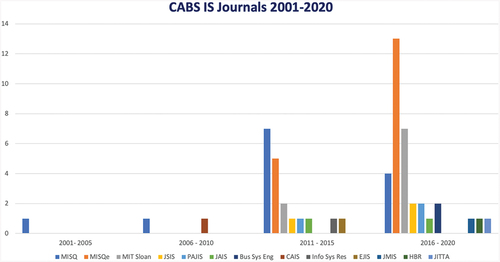

The 87 papers are broken down as follows: 56 journals papers and 31 conference papers. As illustrated in , the earliest published paper in an IS journal, which addressed Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL), appeared in MISQ (a senior scholars’ basket of eight journals) in 2003. In fact, shows that from 2001 to 2010 MISQ and CAIS were the only IS journals publishing papers on the DTL topic (published 2 papers and 1 paper, respectively). In the subsequent time period from 2011 to 2020 MISQ continued to publish papers in the DTL area, with 11 papers published during that time. However, in this decade, it was not only matched, but overtaken by two practitioner-based journals, MISQe and MIT Sloan Management Review (SMR), both of whom published 18 and 9 DTL papers, respectively. In fact, many of these practitioner focused papers have only been published throughout the last five years specifically. This represents a significant growth in DTL research being published in a small number of journals, especially in the last five years. This emergent trend is further illustrated by the growing number of papers being published and presented at the major IS conferences in the last five years.

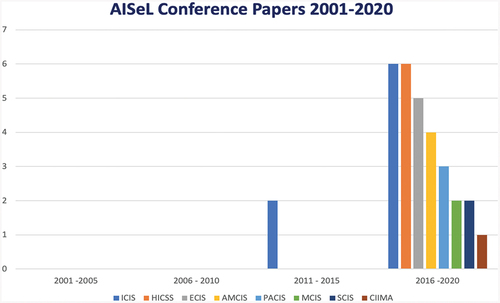

As illustrated in , of the 31 papers that have been published on the DTL topic, several conferences have led the way in this research. As with the more practitioner focused journal outputs (MISQe and SMR), all conference papers have been published in the last five years, with the exception of two papers in 2014 and 2015, respectively, at the International Conference for Information Systems (ICIS). There has been a dramatic increase in the number of papers at the following conferences: the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS) with six papers, the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS) with six papers, the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) with five papers, the American Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS) with four papers, the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS) with three papers, two papers each from the Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS) and the Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems (SCIS), with one paper each from the CONFIRM and CIIMA conferences.

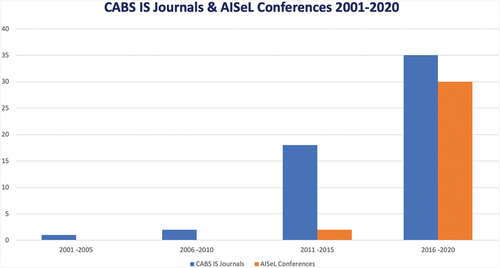

In , we plot the CABS ‘Information Management’ journals and the AISeL conferences. As can be seen, the journals have led the way in DTL research. The most interesting observation is the fact that IS journal papers continued to lead the way until the second part of the 2011–2020 decade, where at that point, the increasing volume of IS conference papers on DTL research matches that of the IS journals. It is envisaged that this trend will continue into the next decade as COVID-19 among other factors begin influencing digital transformation deployments across many organisations. Therefore, to summarise our analysis of the 56 journals; there has been a greater focus on digital transformation leadership (DTL) among the Information Systems community and practitioner focused outputs are much more prolific than more academic focused outputs

3.2 DTL characteristics

While there are many factors that can impact on the successful implementation of a digital transformation programme, none can have as much influence as ‘skilled and competent leadership’ (c.f. El Sawy et al. Citation2016). While there are several competing perspectives on the topic of leadership, there are two main theoretical schools of thought that capture much of the decades of research conducted into leadership. These are (i) the trait theories – a property which describes what leaders are, and (ii) the behavioural theories – a process which describes what leaders do. Traditional research concluding with findings that support a trait theory, present leadership as a characteristic, or a set of characteristics, that successful leaders possess.

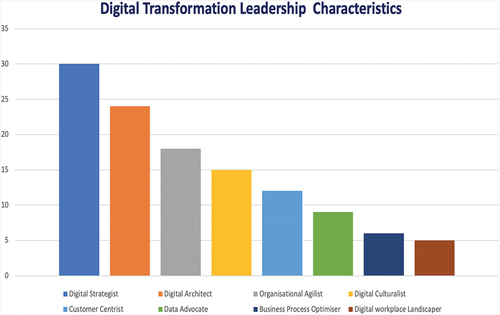

In order to answer the research question posed in this paper (What are the characteristics associated with Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL)?), we now present the results of our open coding of the 87 research papers in this section. Having identified 600 coded excerpts (capturing the ‘who’ and the ‘what’ of DTL) we generated 142 concepts which we rolled up into eight categories (reflecting the emergent characteristics of DTL). These DTL characteristics are as follows: digital strategist, digital culturalist, digital architect, customer centrist, organisational agilist, data advocate, business process optimiser and digital workplace landscaper. Each DTL characteristic consists of concepts that reflect the breadth and depth of leadership required and decisions to be made for a digital transformation programme to succeed. We use the frequency count of concepts to prioritise the categories (see for the distribution of DTL characteristics).

As highlighted in , the digital strategist has the highest number of occurrences and has consistently appeared in research papers over the twenty-year period (2001–2020). This illustrates the importance of leaders to be strategic in their approach to digital transformation. This DTL characteristics are closely followed by being a digital architect, which illustrates the need for leaders and leadership to understand technology and innovation and what best fits the organisation when looking to digitally transform. As a result, we contend that both the digital strategist and digital architect are established characteristics of DTL. Thereafter, the organisational agilist, digital culturalist and customer centrist are viewed as belonging to the emergent category of DTL characteristics, as illustrated by the organisational change that has transpired in recent times from the exploitation of digital resources both human and physical; and the improved customer collaboration and experience through the optimisation of digital services. Furthermore, the data advocate, business process optimiser and digital workplace landscaper have a growing number of occurrences within research papers published in recent years. These DTL characteristics highlight the importance of leadership to be data driven, to identify how business processes can be improved and reengineered through digital transformation. Of particular note, the digital workplace landscaper characteristic is taking on a high level of significance in recent years and will continue to do so as the workplace becomes more influenced by digitalisation and remote working becomes more normal practice. This has been accelerated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has reshaped the world of work for many organisations.

We now present these DTL characteristics in descending order of frequency throughout the remaining sub-sections.

3.2.1 Digital strategist

Based on our analysis of digital strategist, some of the concepts that inform the digital strategist and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: make digital transformation a strategic priority, advise the top management team on digital transformation, create and communicate a digital vision, change the organisational mindset, and adapt the approach to digital transformation. As presented in , strategy, mindset and achieving top management support is central to digital transformation. This involves prioritising digital transformation as a strategic objective by influencing top management to put it top of their agenda. Creating a digital vision and mindset and communicating it in a top-down fashion coupled with creating, communicating and executing a digital strategy throughout the organisation are key elements of the role of the digital strategist. The digital strategist therefore leads on a digital vison and mindset.

Table 4. Digital strategist concepts.

The digital strategist creates a vision for digital transformation in a top – down manner enterprise-wide implementation (Singh & Hess, Citation2017, Dery et al 2016 and Hess and Matt 2017). The digital strategist must be accountable for a well-functioning and collaborative strategic partnership between IS and business leadership to adapt a digital transformation (Singh & Hess, Citation2017 and Hess and Matt 2017; Hess et al., Citation2016).The digital strategist is tasked with value creation and enhancing stakeholders value propositions across many organisations (Fitzgerald et al 2013 and Berman et al 2012) and increases transparency through digitalisation at every stage of its implementation and with the power of instrumentation leaders will lead and manage using digitalisation (Bennis Citation2013, El Sawy et al., Citation2016; Granados & Gupta, Citation2013).

3.2.2 Digital culturalist

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the digital culturalist and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: advocate and cultivate a passion for digital transformation, use an ambidextrous approach to foster a digital organisational culture, and develop skills and competencies in the workforce. As presented in having a culture in an organisation that is predisposed to digital transformation is key. This involves advocating and cultivating a passion for digital transformation and fostering an ambidextrous approach to creating a digital culture in the organisation which can be embraced top down and bottom up, where both management and employees are receptive of it. Changing the culture needs buy in from all sections and needs to include the philosophy of empowering employees to develop skills and competencies in digital transformation, this requires a digital evangelist to illustrate the benefits and challenges of digital transformation which can improve the organisation. This suggests that the digital culturalist leads on an ambidextrous approach to digitalisation and instilling a digital culture.

Table 5. Digital culturalist concepts.

Being a digital culturalist embodies the need to act as a digital pioneer and native, have a digital mandate for change in their respective organisations, including creating new leadership roles such as the chief digital officer (Haffke et al., Citation2016; Horlacher et al., Citation2016 and Singh et al Hess, 2017).The digital culturalist specialises in advocating, fostering and creating a digital culture and acting as a digital role model for the organisation (Granados & Gupta, Citation2013). The digital culturalist in digital transformation leadership ensures skillsets are on par from both internal and external sources (Dremel et al., Citation2017) and evolves the workforce through the acquiring of digital skills and competencies (G. C. Kane et al., Citation2015; Peppard et al 2016). It furthermore endeavours to allow leadership to cultivate atop down digital leadership approach (Eden et al., Citation2019) necessary to drive forward digital transformations across enterprises. The digital culturalist is ambidextrous having supply and demand side qualities critical to digital transformation implementation (Piccinini et al., Citation2015).

3.2.3 Digital architect

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the digital architect and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: define and architect a digital services platform, think digitally and innovate digitally enabled operations, and explore and exploit digital technologies to implement operational excellence. As presented in creating a digital platform and using innovation and digital technologies to deliver digital transformation is key. This involves designing and implementing a digital platform through innovation and using the most relevant digital technologies to deliver a resilient digital architecture for digital transformation. This suggests that the digital architect leads on digital platform architecture using current and emerging digital technologies.

Table 6. Digital architect concepts.

The digital architect creates operational excellence by exploring and exploiting digital technology foundations for digital transformation (Nwankpa & Roumani, Citation2016; Singh & Hess, Citation2017) for systems integration through agile and scalable digital operations. The digital architect is tasked with architecting a digital services platform for repositories of data within organisations (Sebastian et al., Citation2017, Ross et al 2016). The digital architect must bear in mind to not react to one off opportunities but instead proactively design for sustained success in the organisation (Hansen et al 2016, Singh & Hess, Citation2017; Haffke et al., Citation2016; Sebastian et al., Citation2017). The digital architect must understand how digital transformation is enabled by emerging technologies such as big data, cloud computing, Internet of things, mobile technologies and social media platforms (Resnick et al Citation2002, Fitzgerald et al. 2013).

3.2.4 Customer centrist

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the customer centrist and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: create and strengthen customer collaboration, create a ‘360 degree’ customer experience and improve business services, optimise and deliver digital services to customers and generate value for customers. As presented in the customer centricity will develop by strengthening collaboration and improving customer experience through digital transformation. This suggests that the customer centrist leads on enhancing the customer value proposition.

Table 7. Customer centrist concepts.

The customer centristis concerned with creating a better customer collaboration for customer services improvement so as to increase its sales of products and services using digitalisation (Hess et al 2015, Hansen et al., Citation2011 and Weill Citation2013). The customer centrist looks to improve customer experience through the right digital technologies (Westerman & Bonnet, Citation2015) and be accountable for the delivery and optimisation of digital services to customers (Davenport et al 2013). The customer centrist manages the customer engagement part of the platform supporting innovative business services or front-end apps for customers to use (Sebastian et al., Citation2017) along with generating value for the organisation through digitalisation.

3.2.5 Organisational agilist

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the organisational agilist and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: embrace the need for positive organisational change, develop ambidexterity in the exploitation and exploration of resources for digital transformation and identify and hire suitably skilled people to implement digital transformation. As presented in , the organisational agilist will develop the approach for the organisation to implement digital transformation through exploring and exploiting the necessary resources and how that organisational change will be governed successfully. This suggests that the organisational agilist leads on cross-functional connectedness and simplification of operations.

Table 8. Organisational agilist concepts.

The organisational agilist needs to convince the entire organisation to embrace digitalisation to by interlinking different functions enterprise wide (Hansen et al., Citation2011). It looks to simultaneously balance the exploitation and exploration of resources for a successful digital transformation implementation through hiring the right technical staff to implement it (Hess et al 2015, Weill et al 2013) which may require adapting their approach to digital transformation based on specific demands and opportunities identified (El Sawy et al., Citation2016).

3.2.6 Data advocate

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the data advocate and the decisions that need to be made category are as follows: create a data-driven culture and mindset, create a data strategy for data exploitation, and design a data architecture using digital technologies. As presented in , data and its exploitation are central to digital transformation. This involves building a successful data strategy, data culture, and data architecture so that enterprise data can be analysed and used to make informed decisions and create value. This suggests that the data advocate leads on leveraging data for strategic enhancement.

Table 9. Data advocate concepts.

The data advocate assists leadership with creating the architectural platform in digital transformation to harness insights from big data analytics which significantly improves information availability for managers to make evidence-based decisions (Dremelet al 2017). Information ubiquity in a digital world helps every leader at every level to a better understanding of the various stakeholder groups (Bennis Citation2013). The data advocate is focused on having a digital services backbone made up of technologies such as cloud computing, data analytics and mobile technologies provide opportunities to create value for data and for real-time decision-making (Piccinini et al., Citation2015, Ross et al 2016; Eden et al., Citation2019).

3.2.7 Business process optimiser

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the business process optimiser and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: reengineer and optimise business processes and ensure business driven process change. As presented in the business process optimiser involves reengineering and improving business processes with a focus on how digitalisation will align and optimise business processes. This suggests that the business process optimiser leads on cross-functional business process optimisation.

Table 10. Business process optimiser concepts.

The business process optimiser during digitalisation must optimise business or functions performance by abandoning the ‘divide and conquer mindset’ typical of many large organisations, integration is critical for digital transformation to be a success across these organisations (Ross et al 2016). The business process optimiser is a chief business process owner tasked with organising multiple process and sub-process owners distributed across the organisation to drive business process optimisation (Winkler & Petteri, Citation2018). The business process optimiser needs to be bold enough to request the best functional experts the organisation has available to drive business process change through digitalisation (Winkler & Petteri, Citation2018).

3.2.8 Digital workplace landscaper

Based on our analysis, some of the concepts that inform the digital workplace landscaper and the decisions that need to be made are as follows: create, manage and pioneer a digital workplace and improve employee experience through innovative digital solutions. As presented in the digital workplace landscaper will concentrate on developing a digital workplace for employees, identifying the innovation and technical solutions that transform the work environment and that creates greater flexibility for organisations. This suggests that the digital workplace landscaper leads on resource evolution and overcoming barriers to change.

Table 11. Digital workplace landscaper concepts.

The digital workplace landscaperinvokes changes in the workplace through enterprise-wide digitalisation (El Sawy et al., Citation2016), changes in the workplace requires CEO and top management team supports using IT Leadership to manage digital workplace transformation rather than functional leaders (Dery et al 2016). The digital landscaper knows the value of IT in response to environmental dynamics and therefore is able to harness those IT resources appropriately when delivering change (Hansen et al 2012).

4 Discussion: mapping DTL characteristics to C-Suite roles

This section advances our understanding of the ‘what’ of DTL (the characteristics) and poses a question relating to the ‘who’. In so doing, we are putting a ‘face to the name’ of each DTL characteristic. presents a leader-centred digest of the DTL characteristics. Our proposed DTL characteristics (the ‘what’) are highlighting the ‘values’ or ‘core traits’ that a leader (e.g., c-suite role) needs to possess to deliver a successful digital transformation programme. So, for example, being a digital strategist or a data advocate are fundamental DTL characteristics for certain c-suite roles (the ‘who’). One could say it is no surprise that a number of c-suite roles have emerged as potential digital leaders from our analysis of the literature. In fact, we identify some c-suite roles as espousing several DTL characteristics while others have fewer. The most popular c-suite roles that have emerged from the literature, as espousing these DTL characteristics, are the Chief Digital Officer (CDO), the Chief Information Officer (CIO), and the Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Others, such as the Chief Technical Officer (CTO), the Chief Data & Analytics Officer (CDAO), the Chief Innovation Officer (CINO) and Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) emerge as playing a very specific leadership role within a digital transformation programme. In some cases, the proposal of a DTO (Digital Transformation Officer) who motivates, orchestrates, and aligns digital initiatives has gained some popularity in recent times (Gimpel et al., Citation2018).

Taxonomies help us to organise our knowledge and can bring structure and completeness to our understanding of a domain area (c.f. Dezdar & Sulaiman, Citation2009). A taxonomy is valuable in that researchers can assign concepts to a category and define relationships between these categories (Dezdar & Sulaiman, Citation2009, p. 1045). This study is significant because few, if any, taxonomies have been presented in literature relating DTL characteristics (the ‘what’) to c-suite roles (the ‘who’). There is now a need to consolidate prior research and present a holistic and bigger picture of DTL characteristics and their association with the c-suite roles. The taxonomy presented in this paper (see ) provides a visual representation of this association and based on our analysis, highlights the fact that no one c-suite role possesses all of the DTL characteristics.

Table 12. DTL characteristics to C-suite Taxonomy.

There is no doubt from our analysis that it is very difficult for one individual leader to be all encompassing when it comes to delivering a digital transformation programme. However, it also highlights the need for digital transformation leadership to be considered a team sport and further highlights the mix of c-suite roles that should combine to ensure that all the DTL characteristics are in play. For example, from the perspective of the digital strategist DTL characteristic, it is something that the CDO, CIO and CEO need to be focused on (see ). Furthermore, from the perspective of the Chief Digital Officer (CDO) role, it appears as if the CDO and CIO have the greatest number of DTL characteristics associated with them (covering seven of the characteristics). In fact, the CDO, CIO and CDAO cover all eight of the DTL characteristics emerging from the literature (see ).

4.1 Chief Digital Officer (CDO): -digital strategist, digital culturalist, digital architect, customer centrist, and digital workplace landscaper

The CDO (Chief Digital Officer), a new specialist role which has emerged in many organisations. The CDO views themself as a digital strategist, a digital advisor so creating a shared digital vision for the company, changing to a digital business model and developing a digital mindset across the organisation. The CDO is primarily an evangelist, a digital culturalist, whose mission it is to ‘take the organization on a digital change journey and sensitize people that the world as we know it will not exist for long’ (Haffke et al 2017). The CDO role can be centralised at the group level or decentralised at the subsidiary level but their priority is to make digital transformation a strategic priority in their companies (Singh & Hess, Citation2017). The CDO is a digital workplace landscaper ‘fostering cross-functional collaboration, mobilizing the whole company across hierarchy levels and stimulating corporate action to digitally transform the whole company’, the CDO is also focused on increasing revenues from digital products (Singh & Hess, Citation2017). Yet the CDO can also be viewed as digital architect, by monitoring and managing the introduction of new technology innovations relating to the content platform (El Sawy et al. , Citation2016). The CDO can be customer centrist focused on using new digital technologies to enhance the customer experience across all customer touch points, creating a ‘360 degree’ customer experience across all customer touch points (Singh & Hess, Citation2017).

4.2 Chief Information Officer (CIO): -digital strategist, digital culturalist, digital architect, organisational agilist and business process optimiser

The CIO (Chief Information Officer), the acknowledged head of IT in an organisation is generally viewed as having many DTL characteristics. Traditionally, CIOs were responsible for IT strategy, IT operations and IT and business alignment. As digitalisation began to develop within organisations CIOs’ were mainly held responsible for digital innovation, as a digital architect, servicing infrastructure and applications, but in recent years, companies have expected their CIOs to extend their roles from pure technologists to business strategists and subsequently in the role of a digital strategist (Singh & Hess, Citation2017). ‘The CIO may also manage the transformation, which is typically the case if the focus is on business processes, a business process optimiser’ (Matt and Hess 2016). The managing of enterprise processes and the associated digital platform, provides all the IT services the firm needs to operate in a digital economy (Hansen et al., Citation2011; Weill and Woerner Citation2013). There are different shades of CIO’s, one such type is the enterprise process CIO, accountable for the delivery and optimisation of processes focusing on CIO ambidexterity, the transformational character of digitisation, and the distribution of leadership roles and responsibilities in an era of digital business (Haffke et al., Citation2016). They must ensure that internal technical skills and competencies are on a par with those of external consultancies. (Dremel et al., Citation2017)

4.3 Chief Executive Officer (CEO): – digital strategist, digital culturalist, and organisational agilist

The Chief Executive Officer whose primary role is to manage the senior leadership or top management team in the organisation. The CEO is pivotal to the success of digital transformation “because of its high level of complexity (Haffke et al., Citation2016). ‘A truly successful digitalization will require full CEO attention and commitment’ (Bilgeri et al., Citation2017) therefore the role needs to promote the idea that effective digitalisation and digital leadership require a different mindset and requires a ‘deep commitment to enterprise-wide digitalization’ (El Sawy et al., Citation2016). The CEO is fully responsible for and adds authority to the digital transformation strategy (Hess and Matt 2016). CEOs need to be transparent and must ensure that there is a transparency strategy (Granados et al 2013), be adaptive and resilient and personally champions the digital agenda to provide a dedicated focus on leveraging the digital edge (Sia et al., Citation2016). Successful digital transformation also requires clearly defined roles and responsibilities as well as top-management support which fosters ‘increased transparency through digitization’ (Dremel et al., Citation2017).

4.4 Chief Technical Officer (CTO) & Chief Innovation Officer(CINO): – digital architect

The Chief Innovation Officer (CINO) and the Chief Technology Officer (CTO) are seen as most suited to the role of the digital architect. The digital architect creates an environment that fosters innovation and provides the organisational structure to support the development of new products and services. The CTO as a digital architect is seen as the individual to manage the plan-build-run way of organising IT (MIS Quarterly Executive, Citation2016)

The digital architect innovates and thinks digitally, creates the digital workplace, develops operational excellence and an operational backbone using digital technologies (Singh & Hess, Citation2017). The digital architect coordinates innovation standards and methodologies to build a digital architecture and an agile and scalable digital platform for the organisation, through the correct blend of emergent technologies (Granados & Gupta, Citation2013). Their role involves exploiting ideas from both internal and external sources (Singh & Hess, Citation2017).

4.5 Chief Data & Analytics Officer (CDAO): – data advocate

The Chief Data & Analytics Officer is recognised as the senior leadership role in an organisation responsible for the management of the enterprise data. ‘Chief Data Officers thus focus on just one organizational capability within the digital realm: big data, but the scope of the CDAO role is much broader and not confined to this one specific area of digital transformation’ (Singh & Hess, Citation2017). The chief data and sometime analytics officer is a strategist, architect, organisational agilist and customer centrist in the data domain (CitationLee et al.,). However, being a data advocate is their primary role in digital transformation. The CDAO encourages the importance of big data analytics in generating valuable insights from micromarketing and increased digital engagement (El Sawy et al., Citation2016).

4.6 Chief Marketing Officer (CMO): – customer centrist

The Chief Marketing Officer or Chief Customer Officer is seen as the senior leader in the organisation with responsibility for customer engagement. The CMO is a customer centrist who uses technology such as social media to transform organisations into more transparent, customer-oriented businesses. Leading digital transformation requires a professional with particular characteristics such as technology and business, a vision of the future to be applied in the present; however, it doesn’t always require a CDO or CIO and it can be the CMO (Chief Marketing Officer) (Tumbas et al., Citation2017). CMOs are customer centrists mastering the art of collaboration with both external and internal customers and partners as well as with technology platform companies (focusing on digital transformation and how organisations engage with their customer base through the development of a digital services platform and digital channels and technologies).

5 Summary and future research directions

According to Rowe (Rowe, Citation2014), there is a need within the IS community to publish more literature reviews. He argues that ‘literature reviews can be highly valuable’ and ‘every researcher looks for [a literature review] when starting a research study’(Rowe, Citation2014, p. 242). So where the primary goal of a literature review is ‘to classify what has been produced by the literature’(Rowe, Citation2014, p. 243), we believe that we have achieved this for Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL) characteristics (see ). We conceptualise DTL across eight characteristics (the ‘what’) and further present an initial mapping of these characteristics to c-suite roles (the ‘who’), taxonomically (see ). This work provides rich descriptive theorising of the phenomenon and generates interesting insights into the DTL characteristics that can help organisations to be more successful with their digital transformation programmes; for example, making decisions around these DTL characteristics requires an intuitive, decisive and informed leadership approach in areas such as digital vison and mindset, cross-functional connectedness and simplification of operations, and resource evolution and overcoming barriers to change. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to do such an analysis of DTL characteristics in the IS domain.

As proposed by Al-Mashari et al (Citation2003, p. 362) in relation to ERP systems implementation, a taxonomy puts forward the idea that ‘regular audits and benchmarking exercises can bring with them new [insights] that will make the organisation more adaptable to change programmes and will also, provide them with the opportunity to derive maximum benefits from investing in complex systems such as ERP’. This sentiment also holds through for digital transformation and the fact that leadership is such a key aspect to delivering digital transformation programme success. In fact, our understanding of the leadership required to change an organisation’s structure and business model is improving and through the completion of this research work, with the emergence of the eight DTL characteristics, we expect that we have advanced this understanding further. Instead of putting leadership on the shoulders of one individual (c-suite role) who espouses all eight DTL characteristics, we are suggesting that a leadership team needs to exist around a digital transformation programme. These leaders are responsible for taking a people, process, technology and data perspective on the digital transformation programme. Now that we have identified these DTL characteristics, we need to provide some calls-to-action to progress this work further. We need to understand if these DTL characteristics have specific relationships between them, for example, is the digital strategist characteristic impacted by the presence/absence of another characteristic (e.g., customer centrist or data advocate). Furthermore, the decisions that are made to shape the leadership of a digital transformation programme need to reflect on these eight DTL characteristics in order to avoid programme blindspots. This DTL characteristics reflection can take place (i) during the formation of a leadership role/team that will lead out a digital transformation programme or (ii) in a retrospective with an existing leadership role/team of an existing digital transformation programme. It is important that decisions are made to ensure that digital transformation leadership readiness is as good as it can be.

Rowe (Citation2014, p. 246) suggests that ‘the quality of a literature review depends on its systematicity since systematicity implies reproducibility through documenting the search process and potentially indicates comprehensiveness’. This research identified and analysed 87published IS articles. Using a systematic approach, through the eight coding steps of content analysis, these 87 research papers were analysed using open coding to complete in-depth content analysis of DTL characteristics. Therefore, we believe that we have achieved the systematicity required. That is, to ensure the reproducibility of our work by others. These 87 research papers were selected from the journals categorised under ‘Information Management’ in the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) list, along with the major IS conferences listed in the AIS eLibrary. With regard to the 93 journals categorised under ‘Information Management’ in the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) list, only 13 have published research papers in the DTL area since 2001. Specifically, MISQe, MISQ and Sloan Management Review have published the majority of these papers, with 18, 13, and 9 papers, respectively (40 papers out of a total of 56 published). Of further interest is the fact that 24 of these 40 papers were published over the past five years. This suggests that DTL is a continually developing area of research and investigation. As a result, a great volume of research papers might be expected in the coming years within these ‘Information Management’ journals. Furthermore, other journals, categorised under ‘Strategy’ or ‘Innovation’, should also be searched in order to ensure that other existing/forthcoming relevant DTL research is not overlooked.

Embracing the advice of Webster and Richard (Citation2002, p. xxi), we believe that we have addressed the contributions (what’s new?), impact (so what?), logic (why so?) and thoroughness (well done?) expected from a review article. Hopefully, it represents a ‘benchmark for others. The research conducted on the 87 journal and conference papers illustrates that there are certain characteristics that Digital Transformation Leadership (DTL) requires to deliver a digital transformation programme in an organisation. It is suggested that empirical research should now be undertaken to establish if Digital Transformation leaders share the same views around the DTL characteristics. In fact, given the relatively small volume of research outputs on DTL over the past two decades, it may be a worthwhile approach to follow a Grounded Theory approach (data-to-theory) to identify the DTL characteristics from the experiences of Digital Transformation leaders (both operational and strategic) ‘in the trenches’. This would offer a valuable compare and contrast of the theory and practice of DTL and further our understanding of the DTL characteristics. Most likely this empirical work would produce a set of critical success factors to aid leaders and decision makers in their digital transformation programmes.

The leadership required to lead a Digital Transformation programme is perhaps greater than is anticipated, simply because, in many cases, the volume of changes within the business is unprecedented and making the right decision is not always a straight forward undertaking. Where process and technology are the most tangible and visible of changes that can take place, the changes to the role that data now have to play within the business is perhaps under-appreciated. This is especially true if the business is working to deliver value to its customers in new ways. Creating a digital experience for customers relies on mature thinking around data and its exploitation. Notwithstanding this and even more challenging though is the leadership that is needed to guide the people within the business through the Digital Transformation journey. Finally, from our research and analysis, we have seen that there are levels of maturity that define DTL characteristics; for example, established, emergent and emerging. A review of the literature has illustrated that characteristics such as digital strategist and digital architect have been established for a period of time, since 2001–2010, and continue to be mentioned as key characteristics for leaders and leadership undertaking a digital transformation programme in their organisations. Other characteristics are emergent over the past decade such as organisational agilist, digital culturalist, and customer centrist. However, recent literature has also informed us of emerging characteristics, such as, data advocate, business process optimiser and digital workplace landscaper. The patterns behind these established, emergent and emerging characteristics demands that more research is conducted to further investigate these levels of maturity that define the DTL characteristics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Agarwal, R., Guodong, G., DesRoches, C., & Jha, A.K. (2010). The digital transformation of healthcare: Current status and the road ahead. Inform. Syst. Res, 21(4), 796–809. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0327

- Agarwal, R., Johnson, S. L., & Lucas, H. C. (2011) Leadership in the Face of Technological Discontinuities: The Transformation of EarthColor. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 29, pp-pp https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.02933 Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss3/7

- Alhassan, I., Sammon, D., & Daly, M. (2018). Data governance activities: A comparison between scientific and practice-oriented literature. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(2), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-01-2017-0007

- Alhassan, I., Sammon, D., & Daly, M. (2019). “Critical success factors for data governance”: A telecommunications case study, Journal of Decision Systems. 28(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2019.1633226

- Al-Mashari, M., & Al-Mudimigh, A. Mohamed Zair Enterprise Resources Planning: A taxonomy of critical factors European. Journal of Operational Research April, 2003(Pages), 352–364.

- Andriole, S.J. (2017). Five myths about digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev, 58(3), 20–22.

- Antonopoulou, K., Nandhakumar, J., & Begkos, C., 2017. The emergence of business model for digital innovation projects without predetermined usage and market potential. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Beach, HI, pp. 5153–5161.

- Baiyere, A., Tapanainen, T., & Salmela, H., “Agility of Business Processes – Lessons from a Digital Transformation Context“ (2018). https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2018/1 Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems 2018 Proceedings

- Barthel, P., & Hess, T. (2020). Towards a characterization of digitalization projects in the context of organizational transformation. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(3), 31–56. https://doi.org/10.17705/1pais.12302

- Benlian, Alexander; Kettinger, William J.; Sunyaev, Ali; Winkler, Till J. (2018): Special Section: The Transformative Value of Cloud Computing: A Decoupling, Platformization, and Recombination Theoretical Framework. In: Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 35, No. 3: pp. 719–739

- Bennis, W., Leadership in a Digital World: Embracing Transparency and Adaptive Capacity Management Information Systems Quarterly Vol 37 No. 2/ June 2013.

- Benlian, A., Haffke, I., 2016; Does mutuality matter? Examining the bilateral nature and effects of CEO-CIO mutual understanding. J. Strat. Inform. Syst. 25 (2), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2016.01.001

- Berghaus, S., & Back, A., 2016. Stages in digital business transformation: Results of an empirical maturity study. Mediterranean Conference of Information Systems, Cyprus.

- Besson, P., & Rowe, F., 2012 Strategizing information systems-enabled organizational transformation: A transdisciplinary review and new directions, The Journal of Strategic Information Systems Vol 21 June 2012, 103–124.

- Bharadwaj, A., El Sawy, O.A., Pavlou, P.A. and Venkatraman, N., 2013. Digital business strategy: toward a next generation of insights. MIS quarterly, pp.471–482.

- Bilgeri, D., Wortmann, F., & Fleisch, E., “How Digital Transformation Affects Large Manufacturing Companies Organization“ (2017). International Conference on Information Systems 2017.

- Braf, E., & Melin, U. LEADERSHIP IN A DIGITAL ERA - IS “DIGITAL LEADERSHIP” A BUZZWORD OR A SIGNIFICANT PHENOMENON? 11th Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems (2020). https://aisel.aisnet.org/scis2020

- Carroll, N., (2020). “THEORIZING ON THE NORMALIZATION OF DIGITAL TRANSFORMATIONS“ In Proceedings of the 28th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), An Online AIS Conference, June 15-17, 2020. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rp/75

- Corbin, J.M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Davenport, T., & Westermann, G. (2018), “Why So Many Digital Transformations Fail, Harvard Business Review March 9th 2018.”

- Dery, K., Sebastian, I.M., & Meulen, N.V.D. (2017). The digital workplace is key to digital innovation. MIS Quart. Exec, 16(2), 135–152. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol16/iss2/4

- Dezdar, S., & Sulaiman, A. (2009). Successful enterprise resource planning implementation: Taxonomy of critical factors. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 109(8), 1037 1052. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570910991283

- Dremel, C., Wulf, J., Herterich, M.M., Waizmann, J.-C., & Brenner,Management Information Systems Quarterly Executive. June 2017, Vol. 16 Issue 2, 81–100. 20p.

- Eden, R., Burton-Jones, A., Casey, V., & Draheim, M. (2019) Digital and Workforce Transformation Go Hand-in-HandManagement Information Systems Quarterly Executive (2019). https://doi.org/10.17705/2msqe.00005

- El Sawy O., (2016) “How LEGO Built the Foundations and Enterprise Capabilities for Digital Leadership” June 2016 P141-167 MIS Quarterly Executive Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol15/iss2/5

- Engesmo J, Panteli, N (2020); Digital Transformation and its Impact on IT Structure and Leadership, 11th Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems https://aisel.aisnet.org/scis2020

- Fitzgerald, M., Kruschwitz, N., Bonnet, D., & Welch, M. (2014). Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev. 55 (2), 1–12. For Data Governance”: A Telecommunications Case Study, Journal of Decision Systems, 28(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2019.1633226

- Finney, S. and Corbett, M., (2007). “ERP implementation: a compilation and analysis of critical success factors”, Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 329-347. https://doi.org/10.1108/14637150710752272

- Gimpel, H., Hoseinnini, S., Huber, R., Probst, L., Roglinger, M., & Faisst, U. Structuring Digital Transformation: A Framework of Action Fields and its Application at ZEISSJOURNAL OF INFORMATIONTECHNOLOGY THEORY AND APPLICATION. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 19(1), 31-541532-3416. March. 2018.

- Goode, S., & Gregor, S. (2009). Rethinking organisational size in IS research: Meaning, measurement and redevelopment. European Journal of Information Systems, 18(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2009.2

- Grahlmann, K.R., Helms, R.W., Hilhorst, C., Brinkkemper, S., & Van Amerongen, S. (2012). Reviewing enterprise content management: A functional framework. European Journal of Information Systems, 21(3), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.41

- Granados, N., & Gupta, A. (2013). Transparency strategy: Competing with information in a digital world. In Management Information Systems Quarterly, 37(2), 637–642. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825928

- Granados, N.F., Gupta, A., & Kauffmann, R.J. (2006). The impact of IT on market information and transparency - a unified theoretical framework. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 7(3), 148–178. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00083

- Gray, P., El Sawy, O.A., Asper, G., & Thordarson, M. (2013). Realizing strategic value through center-edge digital transformation in consumer-centric industries. MIS Quart. Exec, 12(1), 1–17. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol12/iss1/3

- Gurbaxani, V., & Dunkel, D. (2019); Gearing up for Successful Digital Transformation; MISQe, DOI 10.17705/2msqe.00017

- Haffke, I., Kalgovas, B.J., & Benlian, A., 2016. The role of the CIO and the CDO in an organization’s digital transformation. In: International Conference of Information Systems, Dublin, Ireland.

- Hansen, A.M., Kraemmergaard, P., & Mathiassen, L. (2011). Rapid adaptation in digital transformation: A participatory process for engaging IS and business leaders. MISQuarterly Executive, 10(4), 175–185.

- Hansen, Rina and Kien, Sia Siew (2015). “Hummel’s Digital Transformation Toward Omnichannel Retailing: Key Lessons Learned,” MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 14: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol14/iss2/3

- Heavin, C., & Power, D. Challenges for digital transformation – Towards a conceptual decision support guide for managers. Journal of Decision Systems,27, 38-45. 2018. Issue sup1: IFIP DSS 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2018.1468697

- Henfridsson, O., & Bygstad, B. (2013). The generative mechanisms of digital infrastructure evolution. MIS Quarterly, 37(3), 907–931. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.3.11

- Henriette, E., Feki, M., & Boughzala, I., “The Shape of Digital Transformation: A Systematic Literature Review“ (2015). Mediterranean Conference in Information Systems 2015 Proceedings. 10. https://aisel.aisnet.org/mcis2015/10

- Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A., & Wiesboeck, F. (2016). Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Quart. Execut, 15(2), 123–139.

- Hesse, A., 2018. Digitalization and leadership – How experienced leaders interpret daily realities in a digital world. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Beach, HI, pp. 1854–1863.

- Horlacher, A., Klarner, P., & Hess, T., 2016. Crossing boundaries: Organization design parameters surrounding CDOs and their digital transformation activities. Americas Conference of Information Systems, San Diego, CA. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2019/business_models/business_models/5Information Systems, Munster, Germany.

- Kane, G.C., Palmer, D., Nguyen-Phillips, A., Kiron, D., & Buckley, N., 2017. Achieving digital maturity, 15329194. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, pp. 1–32.

- Kane, G.C., Palmer, D., Phillips, A.N., Kiron, D., & Buckley, N. (2015). Strategy, Not Technology, Drives Digital Transformation. MIT Sloan Management Review, (14), 1–25. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/strategy-drives-digital-transformation.

- Kohli, Rajiv and Johnson, Shawn 2011; “Digital Transformation in Latecomer Industries: CIO and CEO Leadership Lessons from Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc.,” MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 10 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol10/iss4/3

- Lee, Y., Madnick, S.E., Wang, R.Y., Wang, F., & Zhang, H.A. (2014). Cubic Framework for the Chief Data Officer: Succeeding in a World of Big Data Management Information Systems Quarterly Executive March 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/103027

- Leonardi, P.M., & Bailey, D.E., 2008. Transformational technologies and the creation of new work practices: Making implicit knowledge explicit in task-based offshoring.

- Leonhardt, D., Haffke, I., Kranz, J., & Benlian, A., 2017. Reinventing the IT function: The role of IT agility and IT ambidexterity in supporting digital business transformation. In: European Conference of Information Systems, Guimaraes, Portugal, pp. 968–984.

- Maedche, A. (2016). Interview with michael nilles on “What Makes Leaders Successful in the Age of the Digital Transformation? Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng, 58(4), 287–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-016-0437-1

- Majchrzak, A., Markus, M.L., & Wareham, J. (2016). Designing for digital transformation: Lessons for information systems research from the study of ICT and societal challenges. MIS Quart, 40(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2016/40:2.03

- Matt, C., Hess, T., & Benlian, A. (2015). Digital transformation strategies. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng, 57(5), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-015-0401-5

- McKinsey: Digital/McKinsey Insights Report Winning in Digital Ecosystems January 2018Management Information Systems Quarterly (2018). 411–436.

- El Sawy How LEGO Built the Foundations and Enterprise Capabilities for Digital Leadership June 2016, Management Information Systems Quarterly Executive (2016), 141–167.

- Morakanyane, R., Grace, A.A., & O’Reilly, P., “Conceptualizing Digital Transformation in Business Organizations: A Systematic Review of Literature“ (2017). BLED eConference (2017) Proceedings. 21. http://aisel.aisnet.org/bled2017/21

- Muehlburger, M., Kannengiesser, U., Krumay, B., & Stary, C., “A Framework for Recognizing Digital Transformation Opportunities“ (2020). Research Papers. 82. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rp/82

- Myers, M. (2009). Qualitative Research in Business and Management. Sage.

- Nwankpa, J.K., & Roumani, Y., 2016. IT capability and digital transformation: A performance perspective. In: International Conference of Information Systems, Dublin, Ireland.

- Pagani, M. (2013). Digital business strategy and value creation: Framing the dynamic cycle of control points. MIS Quart, 37(2), 617–632. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.13

- Peppard, J., Edwards, C., & Lambert, R. 2011. “Clarifying the Ambiguous Role of the CIO,” Management Information Systems Quarterly (2011) (10:2), pp. 115–117.

- Peppard, J., Galliers, R.D., & Thorogood, A. (2014). Information systems strategy as practice: Micro strategy and strategizing for IS. J. Strategic Inform. Syst, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2014.01.002

- Piccinini, E., Hanelt, A., Gregory, R., & Kolbe, L., 2015. Transforming industrial business: The impact of digital transformation on automotive organizations. International Conference of Information Systems, Forth Worth, TX.

- Rizk, A., Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., & Elragal, A., 2018. Towards a taxonomy of data-driven digital services. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa Beach, HI, pp. 1076–1085.

- Resnick, M., 2002. Rethinking Learning in the Digital Age. The Global Information Technology Report 2001–2002.

- Ross, J.W., Sebastian, I.M., & Beath, C.M. 2017. “How to Develop a Great Digital Strategy,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology Sloan Management Review(2017), 58(2), 7-9.

- Rowe, F. (2014). What literature review is not: Diversity, boundaries and recommendations. Eur. J. Inform. Syst, 23(3), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.7

- Saldanha, T.J., Mithas, S., & Krishnan, M.S. (2017) Leveraging customer involvement for fueling innovation: The role of relational and analytical information processing capabilities. MIS Quart, 41(1), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.14

- Sambamurthy, V., Bharadwaj, A., & Grover, V. (2003). Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of information technology in contemporary rms. MIS Quart, 27(2), 237–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036530

- Schmid, A.M., Recker, J., & Vom Brocke, J., 2017. The socio-technical dimension of inertia in digital transformations. In: Hawaii International Conference on System (2017).

- Sebastian, I.M., Ross, J.W., Beath, C., Mocker, M., Moloney, K.G., & Fonstad, N.O. (2017). How big old companies navigate digital transformation. MIS Quart. Exec, 16(3), 197–213. http://misqe.org/ojs2/index.php/misqe/article/view/783

- Serrano, C., & Boudreau, M.-C., 2014. When technology changes the physical workplace: The creation of a new workplace identity. In: International Conference of Information Systems, Auckland, New Zealand.

- Setia, P., Venkatesh, V., & Joglekar, S. (2013). Leveraging digital technologies: How information quality leads to localized capabilities and customer service performance. MIS Quart, 37(2), 565–590. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.11

- Sia, S.K., Soh, C., & Weill, P. (2016). How DBS Bank pursued a digital business strategy. MIS Quart. Exec, 15(2), 105–121. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol15/iss2/4

- Singh, A., & Hess, T. (2017). How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Quart. Exec, 16(1), 1–17. https://aisle.aisnet.org/misqe/vol16/iss1/5

- Soh, C., Yeow, A., Goh, Q., & Hansen, R., “Digital Transformation: Of Paradoxical Tensions and Managerial Responses“ (2019). International Conference on Information Systems 2019 Proceedings.

- Somsen, M., Langbroek, D., Borgman, H., & Amrit, C. Rerouting Digital Transformations Six Cases in the Airline Industry https://hdl.handle.net/10125/59932 ISBN: 978-0-9981331-2-6 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2019.

- Smith, H & Watson, T 2019; “Digital Transformation at Carestream Health; MISQe DOI: 10.17705/2msqe.00009

- Svahn, F., Mathiassen, L., & Lindgren, R. (2017). Embracing Digital Innovation in Incumbent Firms: How Volvo Cars Managed Competing Concerns. MIS Quarterly, 41(1), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.12

- Tan, B., Pan, S.L., Lu, X., & Huang, L. (2015). The role of IS capabilities in the development of multi-sided platforms: The digital ecosystem strategy of Alibaba.com. J. Assoc. Inform. Syst, 16(4), 248. https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol16/iss4/2

- Tanniru, M., Khuntia, J., & Weiner, J. (2018). Hospital Leadership in Support of Digital Transformation. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 10 (3). Article 1. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pajais/vol10/iss3/1

- Tumbas, S., Berente, N., & Vom Brocke, J. (2017). Three Types of Chief Digital Officers and the Reasons Organizations Adopt the Role. MIS Quarterly Executive, 16(2), 121–134. https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol16/iss2/5

- Urquhart, C., Lehmann, H., & Myers, M. (2010). Putting the ‘theory’ back into grounded theory: Guidelines for grounded theory studies in information systems. Information Systems Journal, 20(4), 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2009.00328.x

- Van Der Meulen, N., Weill, P., & Woerner, S. (2020); Managing Organizational Explosions During Digital Business Transformations.

- Van Ee, J., Ibtissam, E.A., Ravesteyn, P., & De Waal, B.M.E. (2020). BPM Maturity and Digital Leadership: An exploratory study. Communications of the IIMA, 18(1). Article 2. Available at. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/ciima/vol18/iss1/2

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), pp.118-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

- Vollstedt, M., & Rezat, S. (2019). An Introduction to Grounded Theory with a Special Focus on Axial Coding and the Coding Paradigm, Compendium for early career researchers in mathematics education, 13, pp81-100. April 2019 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15636-74

- Wade, Michael and Shan, Jialu 2020 “Covid-19 Has Accelerated Digital Transformation, but May Have Made it Harder Not Easier,” MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol19/iss3/7

- Webster, J., & Richard, T. WatsonAnalyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review Management Information Systems Quarterly; June 2002; 26, 2; ABI/INFORM Global pg. R13.

- Weill, P., & Woerner, S. (2013). “The Future of the CIO in a Digital Economy,” MIS Quarterly Executive: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol12/iss2/3

- Weill, P., & Woerner, S. (2018). Is your business ready for a digital future? MIT Sloan Manage. Rev, 59(2), 21–24.

- Weinrich, T., Muntermann, J., & Gregory, R.W. 2016. Exploring principles for corporate digital infrastructure design in the financial services industry. In: Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chiayi, Taiwan, p. 285.

- Wenzel, M., Wagner, D., Wagner, H.-T., & Koch, J., 2015. Digitization and path disruption: An examination in the funeral industry. In: European Conference on Information Systems.

- Weritz, P., Braojos, J., & Matute, J., “Exploring the Antecedents of Digital Transformation: DynamicCapabilities and Digital Culture Aspects to Achieve Digital Maturity“ (2020). The American Conference on Information Systems (2020) Proceedings. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2020/org_transformation_is/org_transformation_is/22

- Westerman, G., & Bonnet, D. (2015). Revamping your business through digital transformation. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev, 56(3), 10–13.

- Westerman, G., 2016; “Why digital transformation needs a heart. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev. 58 (1), 19–21.

- Westerman, G., Bonnet, D., & McAfee, A., 2014. The nine elements of digital transformation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 7. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-nine-elements-of-digitaltransformation/.

- White, L.P., & Lafayette, C.M. (2012). Key Characteristics of a Successful IS Manager: Empowerment, Leadership and personality. Pacific Asia Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 4(4). Article 2. Available at. http://aisel.aisnet.org/pajais/vol4/iss4/2

- Windt, B., Borgman, H., & Amrit, C.; Understanding Leadership Challenges and Responses in Data-driven Transformations. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/59936 ISBN: 978-0-9981331-2-6 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2019

- Winkler, T.J., & Petteri, K. (2018, June). Five Principles of Industrialized Transformation for Successfully Building an Operational Backbone. MIS Quarterly Executive, 17 (2), 123–140. http://misqe.org/ojs2/index.php/misqe/article/view/862

- Woodard, C., Ramasubbu, N., Tschang, F.T., & Sambamurthy, V. (2012). Design capital and design moves: The logic of digital business strategy. MIS Quart, 37(2), 537–564. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.2.10

- Yeow, A., Soh, C., & Hansen, R. (2017). Aligning with new digital strategy: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Strat. Inf. Syst, 27(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2017.09.001

- Zimmer, M.P., Baiyere, A., & Salmela, H., “Digital Workplace Transformation: The Importance of Deinstitutionalising the Taken for Granted“ (2020). Research Papers. European Conference in Information Systems (2020), 112. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2020_rp/112118.