ABSTRACT

This study makes new theoretical propositions that reconceptualize what we know about prosocial behaviours in a tourism context. Based on qualitative in-depth interviews and observations involving 27 domestic tourists, it was found that positive emotional gratifications of joy, gratitude, contentment, and happiness accompanied prosocial behaviours involving group photo-taking and sharing on social media, group dining, buying local pastries in support of the local economy and well-being, and interacting with others. The co-existence of benefits to others (altruism) and the self (egoistic) in prosocial engagement questions whether prosocial behaviours are purely altruistic. Rather than taking a binary conceptualization of prosocial motives, it is argued that prosocial behaviours involve the complementary interaction between altruism and egoistically-motivated behaviours.

Introduction

In the current post-pandemic dispensation that has the ability to activate anti-social or prosocial behaviours (Ramkissoon, Citation2020b), understanding domestic tourists’ prosocial behaviours becomes critical to sustainable community wellbeing and social sustainability (Zhang et al., Citation2021). Consequently, recent years have seen renewed interest in prosocial behaviour research in tourism (Han et al., Citation2020, Citation2020; Jeon et al., Citation2022; Kim et al., Citation2018; Ramkissoon, Citation2020b). Tourists often engage in behaviours that can have both positive impacts on the destination’s economy, environment, and society, while some behaviours can lead to negative impacts on the destination (Belisle & Hoy, Citation1980; Buhalis & Fletcher, Citation1995; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2011). Prosocial behaviour connotes voluntary behaviour with the intention to benefit others (Chi et al., Citation2021; Coghlan, Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation2006; Han et al., Citation2020). They are a set of positive behaviours including positive interactions with others, altruistic behaviours, and behaviours that decreases stereotypes (Eren et al., Citation2014; Mares & Woodard, Citation2012).

Prosocial behaviours are argued to be motivated predominantly by altruistic values (Schwartz, Citation1973; Stern et al., Citation1995). However, an alternative school of thought has raised questions as to whether prosocial behaviours are purely altruistic (Hartmann & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, Citation2012). Within this emerging group of scholars, it has been continuously confirmed that intrinsic individual psychological benefits of a “warm glow” explain positive emotional rewards derived from doing good to others and society (Andreoni, Citation1989; Kahneman & Knetsch, Citation1992). Research in environmental psychology suggests that individuals engage in a green electricity programme for self-gratifying emotional rewards (Roe et al., Citation2001). Nonetheless, current tourism research is yet to explore how doing good in the domestic tourism context can benefit others and tourists, particularly, during the COVID-19 period which creates new social norms such as social distancing (Jeon et al., Citation2022).

Current evidence suggests that tourism is a key context for engaging in prosocial behaviours (Tung, Citation2019). Consequently, previous tourism research has examined prosocial behaviours in different areas including residents’ prosocial behaviours (Ramkissoon, Citation2020a; Tung, Citation2019), volunteer tourists’ prosocial behaviours (Coghlan, Citation2015; Han et al., Citation2020), festival tourists’ prosocial intentions (Chi et al., Citation2021) and community prosocial tourism behavioural intention (Jeon et al., Citation2022). To Tung (Citation2019), prosocial behaviours could be employed by residents to refute negative metastereotypes and position residents in a favourable light.

But Maner and Gailliot (Citation2007) argue that prosocial motivations for helping depend on the context of the relations and people’s willingness to help others are more prominent in the context of affinity than among strangers. This could be due to interpersonal trust established through socialization with close friends and families (Ramkissoon, Citation2020b). Such an argument is even more evident in the domestic tourism context where participation involves friends and families (Canavan, Citation2013; Rogerson, Citation2015). Yet only a few studies have given research attention to the nature of prosocial behaviours in a pandemic domestic tourism context.

Many scholars have acknowledged the significant changes in tourism brought about by the global COVID-19 pandemic with domestic tourism suggested as an alternative to reset the industry towards a sustainable path (Farzanegan et al., Citation2021; Qiu et al., Citation2020). Others suggest the pandemic offers a rare opportunity to promote healthy behaviours with social, environmental, and economic implications for destinations (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020). Ramkissoon (Citation2020b, p. 7) contends that the “COVID-19 situation may promote prosocial behaviours as people naturally tend to bond with others in difficult times.” Nonetheless, with its accompanying social distancing, COVID-19 also has a high propensity to trigger anti-social behaviours. Amid these contending views, there remains limited knowledge of what prosocial behaviours are performed among domestic tourists and whether those behaviours are intended to benefit others or otherwise.

Given that the COVID-19 situation destabilizes psychological equanimity through increased mental health issues due to increased anxiety and fear (Pyszczynski et al., Citation2021; Usher et al., Citation2020), it will be problematic in this situation to conceive prosocial behaviours as purely altruistic. A critical examination of previous prosocial tourism research reveals significant gaps that require further exploration (Chi et al., Citation2021, Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2022). First, previous studies are focused on prosocial intentions rather than actual behaviours (Jeon et al., Citation2022). Yet we know that intentions may not necessarily translate into behaviours in the attitude-behaviour gap hypotheses (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). Second, previous studies examining the emotional outcomes of prosocial fail to explicitly examine warm glow though it has been argued that prosocial has emotional outcomes (Zhao et al., Citation2020). Third, previous studies are overly quantitative and fail to situate the issues in the social construction of tourists.

From these gaps, this study has three objectives: 1. It examines the actual prosocial behaviours performed in a pandemic domestic tourism context; 2. It explores the emotional rewards of prosocial behaviours; and 3. It formulates a framework for reconceptualizing the nexus between prosocial and warm glow from a social constructivist perspective. Drawing from both socio-psychology and economic literature, this study is underpinned by the warm glow theory that acknowledges that giving and doing good are not devoid of personal emotional rewards (Hartmann et al., Citation2017). Unlike previous studies that employed a quantitative approach, it is argued from a constructivist perspective that domestic tourists’ interpretation of their behaviour is socially constructed. Hence, this paper employs qualitative methods that situate these actions in their context.

Literature review

Warm glow theory and prosocial behaviors

Tourism is a pleasure-seeking pursuit that has the propensity to drive helping behaviours (Tung, Citation2019). However, tourists’ willingness to help others is determined by a myriad of factors. One such factor is the positive affective state of the helper. Isen (Citation1970) introduced the term “warm glow” to explain this self-gratifying emotional experience and argued that a potential helper’s positive emotional state influences the degree of helpfulness. The warm glow theory argues that there is a feeling of well-being related to the act of contributing to a good cause. A warm glow thus is an affective-emotional state derived from doing good (Isen, Citation1970; Isen & Levin, Citation1972). This emotional feeling results from a cognitive appraisal of the impact of prosocial behaviour on the common good. Tourism research demonstrates that the desire to be perceived in a positive light by tourists can trigger residents’ helping behaviours (Tung, Citation2019) while volunteering internationally makes volunteer tourists feel better and affirmed as they perceive their actions as contributing to a bigger good (Zavitz & Butz, Citation2011).

In an experimental study on the effects of metastereotypes on residents’ prosocial behaviours, Tung (Citation2019) found that positive emotional gratification of being perceived as good residents was derived from acting prosocial towards lost tourists and defusing negative metastereotypes. From a classical economic perspective, a warm glow could also be perceived as a form of utility function derived from the action. Andreoni (Citation1990) revealed that there were direct personal benefits in donations to public goods which he termed the “warm glow of giving”. This personal benefit was purely psychological and evolved from the moral satisfaction of giving to others. Studies in economics suggest that the personal utility derived from prosocial spending supersedes that of self-benefiting compensation when the stakes are low (Imas, Citation2014). However, most tourism studies have examined warm glow indirectly without exploring the concept explicitly.

Tourism literature indicates that an anticipated sense of pride is awakened through appraising individuals’ environmental behaviours (Han et al., Citation2017; Zhao et al., Citation2020). Introducing anticipated emotions to explain environmentally responsible behaviours in heritage tourism, Zhao et al. (Citation2020) found that positive anticipated emotions played a significant impact on environmentally responsible behaviours. Similarly, in a prosocial festival context, Chi, Cai et al. (Citation2021) found that positive anticipated feelings of pride directly influenced the sense of obligation to engage in prosocial behaviours. Hence, prosocial is a means of attaining positive emotions. However, how this phenomenon unfolds in the context of domestic tourism which inherently allows individuals to acquire some personal utility through travel within their local environment is non-existent. Moreover, previous studies are overly quantitative and fail to situate prosocial benefits within the individual’s social environment.

Dwelling on the domestic tour setting, this paper argues that feelings of a warm glow emanate from the cognitive appraisal of engaging in prosocial behaviours. This study thus conceptualizes a warm glow as a positive affective reward such as feeling satisfied, happy, glad, and pleased as a result of acting prosocial (Hartmann et al., Citation2017; Roseman, Citation1991). This paper examines how such feelings unfold in the context of a pandemic domestic tourism situation.

Prosocial behaviors in domestic tourism during the pandemic

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in several negative impacts including increased mental health issues, loss of jobs, and event cancellations such as the 32nd Tokyo Olympic Games (Mohanty et al., Citation2020; Riadil, Citation2020; Rowen, Citation2020; Sigala, Citation2020). Amid these negative consequences, tourism scholars and practitioners have advised the tourism industry to take greater responsibility for putting the well-being of communities first and ensuring justice and fairness in its operation to minimize the negative effect on society (Bae & Chang, Citation2021; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020). Tourists, on the other hand, have become concerned about their well-being and are choosing low-risk tourism products with many desiring local authentic experiences (Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021; Chi & Han, Citation2021; Ivanova et al., Citation2021; Zhu & Deng, Citation2020).

As the tourism industry remains one of the hardest-hit sectors of COVID-19, with outbound travelling dropping due to border restrictions, many have argued for domestic tourism as one of the crucial sustainable alternatives to move the industry towards a path of recovery (Cai et al., Citation2021; Ivanova et al., Citation2021; UNWTO, Citation2021). This is because domestic tourism involves residents travelling within their home region and supporting industry systems that cater to them (Jafari, Citation1986). While domestic tourism is in line with “stay-at-home” COVID-19 policies since residents can still be tourists while staying in their home region (Bairoliya & Imrohoroglu, Citation2020), it is only allowed in regions where the pandemic is controlled (e.g. China) (Agyeiwaah et al., Citation2021; Zhu & Deng, Citation2020).

A key factor that explains domestic tourism engagement is travel motivations. Defined as the internal and external travel motives, travel motivation explicates the differences in behaviours among domestic tourists (Uriely et al., Citation2002). The different motivations behind domestic travel could be explained through various theoretical lenses such as the push (internal) and pull (external) theory (Dann, Citation1977), the functionalist approach (Fodness, Citation1994), and the travel career pattern approach (Pearce & Lee, Citation2005). Of these, the push and pull framework which asserts that people are pushed by their own internal psychological needs and pulled by external destination characteristics has been widely employed (Baniya & Paudel, Citation2016; Bayih & Singh, Citation2020; Bogari et al., Citation2003; Dancausa et al., Citation2023).

Bogari et al. (Citation2003) found nine push motivations (e.g. cultural value, utilitarian, knowledge, social, economic, family togetherness, interest, relaxation, and convenience of facilities) and nine pull motivations (safety, activity, beach sports/activities, nature/outdoor, historical/cultural, religious, budget, leisure, and upscale) among domestic tourists in Saudi Arabia. The authors concluded that the most important motivations for Saudi tourists were religious and cultural values. More recent studies suggest that the emotional experience and novelty constitute two important push motivations for the intentions to engage in domestic travel (Dancausa et al., Citation2023) whereas others suggest socialization as an important motivation (Gaetjens et al., Citation2023). However, given concerns of unpredictable waves through asymptomatic infections as domestic tourists gather at various attractions, people are likely to perceive psychological risk through social interactions thereby impacting prosocial behaviours (Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021).

As voluntary behaviours with the intention to benefit others (Coghlan, Citation2015; Eisenberg et al., Citation2006), prosocial research continues to attract tourism scholars (see Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021; Chi et al., Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2022). Studies during the pandemic suggest that prosocial behaviours include wearing a mask, maintaining social distancing, acting to avoid the spread of COVID-19, practicing hygiene, donating, volunteering, and helping lost/other tourists (Chi et al., Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2022; Romani & Grappi, Citation2014; Tung, Citation2019). While some of these behaviours may be imposed by governments during the pandemic, residents’ attitudes and motives to engage in these behaviours to avoid the spread of the virus make such actions prosocial (Chi et al., Citation2021).

Yet, current research exploring how prosocial actions develop in the domestic tourism context remains scarce despite arguments that demands for prosocial tourism alternatives will become prevalent in both pandemic and post-pandemic periods (Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021). For example, both Chi, Cai et al. (Citation2021) and Chi et al. (Citation2021) argue that despite the relevance of prosocial behaviours to social sustainability and human well-being, prosocial intentions during the COVD-19 pandemic remain scarce. The authors, therefore, examined the cognitive, normative, and moral triggers that predict prosocial intentions within a festival context and suggest that when festival travellers are aware of the significant issues created by COVID-19, they are stimulated by an increased moral obligation to act prosocial in the tourism festival context.

On the other hand, Ivanova et al. (Citation2021) studied travel behaviours during the post-pandemic in Bulgaria and revealed that there is a higher desire to engage in domestic travel within the country with family but concerns about hygiene and reliable health systems play a key role in travel decisions. Undeniably, domestic tourism has taken a centre stage in both pandemic and post-pandemic periods and yet research exploring domestic tourists’ prosocial behaviours to understand what prosocial actions occur in this context and if there are possible self-gratifying benefits from these actions are non-existent. Given the preceding gaps in previous studies that have partially examined prosocial actions and emotional rewards in the domestic context during COVID-19 situation, this paper addresses such inherent gaps as part of contributing to the social sustainability discourses in tourism.

Methodology

Study context and target participants

This study was set in Macau, SAR China. Macau remains a popular tourist destination in Asia that has grown into one of the largest casino hubs attracting tourists from the Mainland of China (Lin et al., Citation2018). Some scholars have called for diversification alternatives for sustainable tourism development that improve the quality of life of locals (Wan & Li, Citation2013). Given the over-dependent on the tourism industry, COVID-19 brought a serious negative impact on tourism activities stimulating initiatives to revive tourism through local tours. One such tour that this study focuses on is the “Macau Ready Go! Tour” which was initiated in 2020 (Macau Government Tourism Office MGTO, Citation2020). Coordinated by the Macau Government Tourism Office, the initiative aimed to promote Macau’s exceptional cultural and historical resources and to gradually resume tourism activities in Macau through 25 different itineraries offered between 17 June and 30 September 2020 ().

This study employed qualitative in-depth interviews and non-participant observations with domestic tourists of a local tour in Macau SAR, China, to understand their prosocial domestic tourism behaviours. This study employs a qualitative method that inductively formulates theories and frameworks to explain prosocial behaviours in a domestic tourism context. Qualitative approaches “uncover the meaning associated with the research phenomenon under investigation” (Coghlan, Citation2015, p. 50). By describing the social phenomenon as they occur, qualitative methods aid the identification of variables that could be used to develop theories and concepts (Bryman & Burgess, Citation2002; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation1998). Several studies in tourism have employed this approach to formulate inductive frameworks (see Agyeiwaah, Citation2019; Sojasi Qeidari et al., Citation2023; Zhang et al., Citation2019). To situate prosocial behaviours in the social world of participants, interviewing their personal experiences and observing emotional reactions were critical to reliable and trustworthy qualitative results.

Qualitative instrument design and data collection process

To provide a description of the phenomenon under study and illuminate the lived experiences of participants in the local tour, this study employed two qualitative techniques of non-participant observations and in-depth interviews (Phellas et al., Citation2011). The use of in-depth interviews with open-ended questions as a data collection technique was to obtain detailed information that could not be ascertained with a structured questionnaire (Bryman, Citation2008; Creswell, Citation2013). This technique was then complemented by observation of emotional reactions during the interviews in line with objective two of this study which explores the emotional rewards of prosocial behaviours. The in-depth interview questions were designed in English and back-translated into Chinese for participants in Macau in a face-to-face interview in September 2020 with the help of local Chinese research assistants.

This bilingual design was useful to ensure that the interviews were understood by participants. Participants, thus, had the choice of their language of preference as enumerators with bilingual skills were trained in the process. The instrument had five main sections. The first section examined the motivations for the tour. For example, “Why did you choose to take part in the Macau Ready Go! Local Tours? The second part examined anti/prosocial behaviours within the domestic tour. To ascertain this without social desirability bias, respondents were asked what they did during the tour and allowed to share any behaviours undertaken during the tour (e.g. What did you do during the visit? Probe: what activities did you do?). The third section examined COVID-19 impacts (e.g. Do you think COVID-19 has led to positive or negative impacts on travel in Macau? Why?). The fourth part explored the emotions associated with engaging in the tour (e.g. Please explain some emotions you felt after participating in this local tour.). These emotions were further observed during the interviews.

The last part involved examining the demographics of respondents (e.g. gender, age, & education). The in-depth interview guide was first piloted with students’ samples to ensure the items were comprehensible. Postgraduate students signed up to participate in the pilot testing after which the actual interviews followed. Two local research assistants helped as enumerators by interviewing participants both onsite and offsite. During the interviews, a non-participant observation was employed where enumerators observed key issues related to research objectives 1 and 2. The first was the adherence to government-induced prosocial actions related to mask wearing and the second was respondents’ facial expressions and gestures regarding emotions such as “happy,” “sad” and “disappointed.” This was to be able to match emotions with behavioural expressions. Based on a purposive sampling of participants for this local tour, 30 respondents agreed to participate and were interviewed by research assistants. Following saturation, 27 respondents were useful for analysis for the current study after which data analysis followed.

Data analysis

Data analysis commenced following data saturation with 27 participants. The initial work was to conduct a back-to-back translation of participants who chose Chinese as the mode of interview. Following appropriate translation procedures for Chinese transcripts, those in English were analysed directly. The first phase of analysis involves transcribing the recorded interviews verbatim while those in written format were analysed. With each interview lasting between 40-60 mins, the size of the in-depth interview responses required software, MAXQDA 2020. The analysis then followed Corbin and Strauss’s (Citation1990) three coding procedures of open, axial, and selective coding in grounded theory to ensure that outcomes reflected exactly respondents’ perspectives. Following three-step procedures, the analysis started with a line-by-line coding which involved reviewing each transcript uploaded as a Word document to the MAXQDA 2020 document system.

Based on the coding system in this software, the initial open coding helped to generate about 25 different codes telling different stories. Some of these basic stories involved activities such as “I feel positive emotions, I am happy and joyful.” The study then proceeded with the next level coding of axial coding where sub-categories are related to major categories within the data to establish relationships and connections. For example, the stories, “I feel positive emotions, I am happy and joyful,” were affective rewards grouped under “warm glow”. The final coding stage of selective coding involved organizing themes based on the broad research questions of the study. For example, “warm glow” aimed to respond to the research question of whether prosocial behaviours are intended to benefit others or otherwise. To support these interviews, observation codes were developed in vivo based on the approach used for the interviews (Manan & Várhelyi, Citation2015). For example, mask-wearing was coded as part of the government-induced prosocial behaviours whereas facial expressions with a “smile”, or “laugh” are coded as positive emotional expressions in support of the interviews. Meanwhile, a “stern face or frown” observation supported negative emotions.

To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, reliability, and validity procedures were strictly adhered to. Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) contend that qualitative research must follow four main procedures of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability to enhance the trustworthiness of the results. Data credibility was ensured in this study by providing clear evidence and depiction of the text to reflect the lived experiences of participants of this local tour. Moreover, the data collection process allowed respondents time to reflect on their domestic experiences. A continuous dialogue with the research assistants ensured the dependability of the results. The lead author with two local assistants reviewed the stories to ensure they are dependable. Further triangulation was followed to ensure data transferability with further reflexivity that provided a means of questioning the research team’s own biases and assumptions that might influence the research process. In the same way, the observations of participants’ emotions were also coded verbatim with discussion among research teams to ensure that what was observed culturally reflects the respondents’ emotions. Following these rigorous procedures, the results are presented.

Results

An overview of the demographics of the respondents shows that one-eighth of the participants are male while the majority (88.9%) were females implying the tour is highly attractive to the female population. Age groups were spread across young and old (). About 40% were young falling within the 21–30 age category while the rest of the 60% were 31 years and above. The majority were high school certificate holders with occupations ranging from housewives to casino staff. Following the demographic, the rest of the findings focus on three main sub-sections and thematic areas involving motivations, appraisal of COVID-19 impacts, prosocial behaviours, and warm glow.

Table 1. Interviewee profile.

Domestic tour motivations

Four main motivations for participating in the tour were identified and could be theoretically grouped into two push motivations (socialization and curiosity) and two pull motivations (local culture and history, and the price of the tour). Overall, participants had mixed motivations for participating in the local tour. One common push motivation reported by more than half of the participants was an opportunity to socialize with friends and families. Two respondents, Doreen and Leah explained that:

Doreen: The only thing that matters is meeting friends. My friends told me that this route is the cheapest (18pataca/per person), but I mainly wanted to catch up and meet my friends. There were many scenic spots that I have been to here, so I could participate in this route with my friends.

Leah: Without any special reason, a colleague told me that the “Air, Sea & Land Tours” is the most cost-effective and interesting tour, which I could travel and enjoy with my husband, sisters, and colleagues. We explored Macao via three different transportations, so I took part in this “Leisure Tours”.

Moreover, curiosity emerged as a second push motivation for participating as Doris explained how she kept wondering how this tour introduces Macau: “I was curious about how the local tour guide introduces Macao, and, I have never joined any local tour even though I have been living in Macao for decades”. In addition to internal curiosity and socialization with friends and families, respondents were pulled by the local history and culture of the city. Many (19 participants) felt that as a government initiative, rather than in other settings, there would be diligence and deeper interpretation since domestic tours are significant contexts to learn about the local culture. This was well explained by Gloria who reflected in previous programmes where history was not well-explained. The current tour was, thus, seen as an opportunity to know more about the local culture, which was a pull for her.

Gloria: Local history and culture are the most attractive to me. However, in previous curriculums, the history of Macao was rarely explained in-depth, so I would be interested to know more about it.

With the significant economic impact of COVID-19 on local activities, tour prices emerged as a second pull factor as 16 (59.3%) participants cited the price of the tour as a key motivation. With government subsidies to encourage broad local participation, Kevin mentioned it was the price that stimulated him to participate in the tour but other social factors were also relevant to him. Since the Macau SAR government intended to revive the tourism industry of Macau, such prices were an advantage to the tour as Kevin explained: “The price is acceptable, plus I haven’t been to the Grand Resort Deck, so it is also out of curiosity, but the most important thing is a reunion with my friends”. These same motives explained why Evelyn chose the Macau local tour as she lamented:

Evelyn: The reason why I chose to join the local tour was that the price is much more favourable than the original price, and I was attracted by the cheaper price and the rich content of the tour. Besides, I rarely have a chance to enjoy the entertainment facilities of Macao integrated resorts, so I can enjoy “Macau Ready Go! Local Tours” by taking advantage of it, especially during the period of the COVID epidemic.

Appraisal of the impacts of COVID-19

The next prevalent theme emerging from the transcripts was the appraisal of COVID-19 impacts. Respondents were aware of the impacts of COVID-19 on this tourism-dependent city. However, while some felt, the impacts were generally negative, a quarter of the respondents took a positive perspective on the impacts of COVID-19. For example, Julie was more articulate about job losses through COVID-19 – “A lot of people lost their jobs because of the novel coronavirus [with a stern face]. Indeed, the virus has given us a body of negative impacts”. However, Joyce lamented the impact on the traditional festival which have been cancelled and rescheduled: “Traditional festivals have been affected including the Macao Feast of Na Tcha and the Macao Feast of the Drunken Dragon. These traditional events were launched this year”. Meanwhile, Michelle particularly was very critical of the city’s over-dependent on tourism and the gaming industry. According to her, the lack of tourists has led to an empty city with limited economic activities leading to stagnation:

Michelle: In recent years, Macao has taken a single economic development approach that relies on the Gambling Industry and Tourism to maintain its economic growth. COVID-19 turned Macao sparsely populated as there are no tourists, as a result, Macao’s economy has suffered unprecedented stagnation, leading to a sharp decline in gambling revenue, which has severely hit all industries in Macao.

Unlike these participants, Jay perceived COVID-19 from a positive lens citing how the downturn in tourism activities provides an opportunity to rethink and reflect on how tourism is implemented within the Asian gaming tourism giant.

Jay: COVID-19 has had a positive impact on Macao tourism, despite the downturn in the Tourism Industry and greatly reduced economy. However, it is a very good time for Macao’s Tourism Industry to reflect on what should be improved. The moderately diversified development of Macao’s Tourism will have a profound reflection on the future development path, which, in my opinion, COVID has given Macao a couple of positive effects.

Prosocial behaviors and warm glow

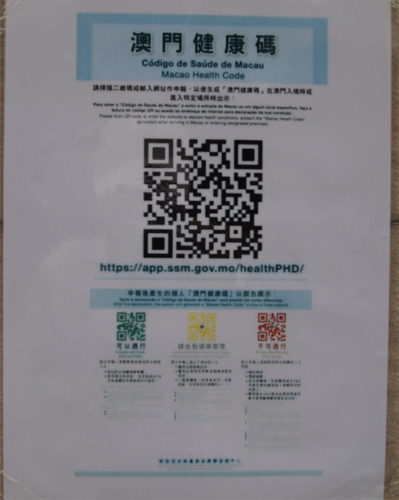

Two sets of prosocial behaviours emerged from this study. The first involves those undertaken by participants with regard to COVID-19 protocols whereas the second part relates to those behaviours engaged during domestic activities. For the first group of behaviours, it was observed that respondents wore a mask during the tour period to avoid the spread of COVID-19 infection. Another key important government-induced prosocial action was respondents declaring their health through the Macau Health Declaration QR code which they were required to scan and present for entry into any building facility (). Having observed these preliminary prosocial actions, residents were further asked about what they do during the tour to understand whether they engage either in prosocial or anti-social behaviours during the tour.

This study found four prosocial domestic tourism behaviours including group photo-taking and sharing photos on social media, group dining, buying local pastries in support of the local economy and well-being, and interacting with others. A key observation is that while motivations were typically expressed in individual terms (I/my), prosocial actions took predominantly community and group-based terms (“we”) and were accompanied by emotional rewards which equally were expressed in individual terms. For example, Evelyn explained how she spent time having lunch with a group of friends during the tour break and expresses this in-group terms: “We had lunch at the food court at Galaxy Hotel then had fun at the Grand Resort Deck”. Meanwhile, demonstrating with their cameras [through the observation], both Kevin and Jay explained how they took the opportunity to take photos with their friends for remembrance. A major prosocial behaviour involved interacting and chitchatting with others while on the tour:

Kevin: We took pictures as a remembrance. We interacted and chitchatted with friends. We had fun taking photos in “teamLab SuperNature Macao”. We went together to the “teamLab SuperNature Macao” at Venetian, a beautiful place to visit.

Jay: During the cruise trip, I enjoyed the whole harbour scene, it was stunning [laughs]. Macao is colourful at night. Luckily, we were able to enjoy the sunset. I took many videos and photos with a group of friends and relatives on the cruise. Later, we took an opened-roof bus and LRT enjoyed the scenery as well. We also took many beautiful photos and shared them with friends on social media. It was a pleasant and fun local travel experience.

In addition to these prosocial actions, those that ensured that local businesses are supported through regular purchases of local pastries were reported. Winnie, for example, would usually not buy local pastries but because of the COVID-19 situation and the current impact on local businesses, it was a way to help small businesses to survive: “I bought local pastries, but I don’t usually buy them because there were too many people before, now people are less because of COVID-19. This is what our Macau locals like and it helps to support the local economy”. A major component of prosocial is the reward that it brings to the individual. In the current study, it was found that interacting with others benefited participants by creating pleasant feelings and contentment. Ivy explained how travelling together as a group of familiar people created a sense of joy:

Ivy:I had a good interaction with my friends. I felt very content and pleased, which increased my sense of belonging. We travelled together with a group of familiar people; the experience was joyful [she nods in positivity]. It doesn’t matter what activities I participate in with my friends. What I care about is traveling with my friends.

While the COVID-19 situation, in part, has spurred the need to be prosocial, 85% (23) of respondents engaged in these actions to benefit relevant “others”. There were significant emotional rewards that accompanied altruistic action. Many participants (22 respondents = 81.5%) reported feeling happy, joyful, grateful, and pleasant throughout these interactions with their significant groups. Stephanie for instance shared how she experienced positive emotions through being prosocial: “I was in a positive mood [smiles]. I feel that I have helped Macau’s tourism industry and I am happy”; while Carol added that: I felt positive emotions and I was very happy [smiles]. Because I played with friends and ate delicious food. Happiness was not only experienced through interacting with others but also through being able to support and promote the local tourism economy that has been hit by COVID-19– Joyce: “I was very happy. Besides, such a tour can promote Macao’s economy”. Others reflected on being grateful throughout the tour. Beaming with a smile, Lisa stated:

I am happy and joyful [she smiles]. Because of the influence of the global pandemic, people have difficulties traveling outside and worry about changes because of COVID-19 every day. However, Macau people can still live in Macau safely without worrying too much. This is something to be grateful for.

The preceding emotions provide evidence that while tourists were not necessarily motivated by an expectation to experience positive emotions, prosocial engagement in the domestic context offered a set of positive emotional rewards that enhances the well-being of individual participants helping them to cope with anxieties that come with the global pandemic.

Conclusion and implications

Tourism remains a key context to engage in prosocial behaviours and this engagement is even more prevalent in the domestic tourism context where socialization is a key motivation (Ivanova et al., Citation2021). However, current research exploring actual prosocial behaviours remains scarce. This paper aims to explore prosocial behaviours in the domestic tourism context and reconceptualize the phenomenon by developing a novel conceptual framework.

Additionally, this research employs a qualitative approach grounded in constructivist epistemology allowing a deeper examination of participants’ actual prosocial behaviours within domestic tourism. The present study findings not only re-echo previous studies in prosocial behaviours and sociocultural sustainability research (Chi et al., Citation2021; Ramkissoon, Citation2020b; Romani & Grappi, Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2021) but, more so, extend the discourse with context-relevant behaviours that call for rethinking how prosocial behaviours are examined in the tourism context. It provides further enrichment of COVID-19 and prosocial behavioural-related studies with a novel theoretical lens that future scholars could employ as a theoretical reference for developing the theoretical depth of prosocial and socio-cultural sustainability studies. These significant contributions are discussed demonstrating their theoretical, methodological, and practical implications.

Theoretically, this study offers insights into prosocial behaviours within the domestic tourism context. It is apparent that in line with Ramkissoon (Citation2020b)’s argument and supported by the present study findings, COVID-19 and domestic tours both trigger prosocial behaviours. While COVID-19-related prosocial behaviours involve actions that avoid the spread of the virus (Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021; Chi et al., Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2022), in the current study, those involving wearing a mask and declaring health code were common government-induced prosocial behaviours within the domestic context (). This study’s findings demonstrate that the engagement of prosocial is a result of the culmination of travel motivations, government prosocial regulations, and the impacts of COVID-19 on the local tourism industry ().

However, because of the ramifications and health concerns of COVID-19 (Chi, Cai et al., Citation2021; Jeon et al., Citation2022), there was in-group formation where people interacted more with their friends and relatives other than with strangers. This raises the question – “who are prosocial behaviors directed towards”? This question reaffirms studies in sociopsychology that argue that prosocial behaviours depend on the context of the relations as people are willing to interact more with those they share filial relations with other than strangers (Maner & Gailliot, Citation2007). Such an argument becomes more prominent in a COVID-19 context where people have become protective of their families and engage in self-isolation to avoid COVID-19 transmission to close families (Sahoo et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it affirms studies in post-pandemic times in Bulgaria where there is a higher desire to engage in tourism with families due to concerns about health implications. Consequently, while COVID-19 spurs prosocial behaviours, perceived risk, perhaps, breaches trust leading to “ingroup” prosocial activities other than “outgroup” during domestic tourism. This, theoretically, implies that prosocial behaviours during COVID-19 create a sense of filial group social identity.

Critical to understanding prosocial behaviours is the argument that such behaviours are intended to strictly benefit the individual or others (Andreoni, Citation1989; Hartmann et al., Citation2017). This paper found that different prosocial behaviours in the domestic context coalesce into a “sweet spot” of emotional rewards including happiness, joy, gratitude, and contentment which are contributory factors to subjective well-being and socio-cultural sustainability (Ramkissoon, Citation2020b; Zhang et al., Citation2021). Hence, there is a beneficial co-existence of others (altruism) and the self (egoistic) in prosocial engagement, and it is the latter that propels the former. Previous studies on environmental behaviours in tourism also confirm anticipated emotional pride awakened through evaluating individuals’ environmental behaviours (Han et al., Citation2017; Zhao et al., Citation2020). Hence, this study calls for reconceptualizing prosocial motives as a complementary relationship between personal and impersonal rewards. Treating altruistic and egoistic values separately from each other may fail to offer the socially desirable impact, particularly during COVID-19 which causes mental health issues (Han et al., Citation2020; Riadil, Citation2020).

From a methodological perspective, this paper offers a combination of qualitative approaches that could overcome the problem of social desirability bias that affects the validity of survey and experimental studies (Tse & Tung, Citation2023). Prosocial behaviours which are inherently subjective are prone to social desirability and thus require one-on-one interviews complemented by observations (Tse & Tung, Citation2023).

From a practical perspective, DMOs can promote social sustainability and community well-being by offering specific on-site activities such as photo-taking, group dining, and interactive breaks during tours. DMOs can partner with hotels and restaurants that can provide group food services and packages for tourists seeking deeper interaction with family members. The tour should provide social breaks where tourists use the opportunity to chitchat and share their experiences on social media platforms such as WeChat. Sharing on social media such as WeChat Moments could encourage other community members to spread the positive energy of prosocial behaviours.

Despite the insightful contributions to prosocial research, it is acknowledged that COVID-19 is still changing with many uncertainties and these behaviours might be fluid and can mutate. Hence, further post-pandemic research is warranted. Given its qualitative nature, future studies can complement qualitative approaches with quantitative approaches for a holistic understanding of prosocial in tourism. It is recommended to examine domestic anti-social behaviours (e.g. discrimination and stereotype) using the qualitative methodology employed in this paper to advance theory building and to extend previous research in the area (Tse & Tung, Citation2020).

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to my Research Assistants (Chi Wo KWAN, Kate and Tam, Kam Lam, Carol) for their support with language translation and data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Agyeiwaah

Dr Elizabeth Agyeiwaah is a Lecturer at the UQ Business School. She is also a Senior Research Associate at the School of Tourism and Hospitality, at the University of Johannesburg. She received her PhD at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Her research interests include sustainable development in tourism and hospitality, small and medium tourism enterprises, and tourist studies.

References

- Agyeiwaah, E. (2019). Exploring the relevance of sustainability to micro tourism and hospitality accommodation enterprises (MTHAEs): Evidence from home-stay owners. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.04.089

- Agyeiwaah, E., Adam, I., Dayour, F., & Badu Baiden, F. (2021). Perceived impacts of COVID-19 on risk perceptions, emotions, and travel intentions: Evidence from Macau higher educational institutions. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1872263

- Andreoni, J. (1989). Giving with impure altruism: Applications to charity and Ricardian equivalence. Journal of Political Economy, 97(6), 1447–1458. https://doi.org/10.1086/261662

- Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477.

- Bae, S. Y., & Chang, P.-J. (2021). The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 1017–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

- Bairoliya, N., & Imrohoroglu, A. (2020). Macroeconomic consequences of stay-at-home policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Covid Economics, 13, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104266

- Baniya, R., & Paudel, K. (2016). An analysis of push and pull travel motivations of domestic tourists in Nepal. Journal of Management and Development Studies, 27, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.3126/jmds.v27i0.24945

- Bayih, B. E., & Singh, A. (2020). Modeling domestic tourism: Motivations, satisfaction and tourist behavioral intentions. Heliyon, 6(9), e04839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04839

- Belisle, F. J., & Hoy, D. R. (1980). The perceived impact of tourism by residents a case study in Santa Marta, Colombia. Annals of Tourism Research, 7(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(80)80008-9

- Bogari, N. B., Crowther, G., & Marr, N. (2003). Motivation for domestic tourism: A case study of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Tourism Analysis, 8(2), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354203774076625

- Bryman, A. (2008). Why do researchers integrate/combine/mesh/blend/mix/merge/fuse quantitative and qualitative research. Advances in Mixed Methods Research, 21(8), 87–100.

- Bryman, A., & Burgess, B. (2002). Analyzing qualitative data. Routledge.

- Buhalis, D., & Fletcher, J. (1995). Environmental impacts on tourist destinations: An economic analysis. Sustainable Tourism Development, 3–24. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19961802325

- Cai, G., Xu, L., & Gao, W. (2021). The green B&B promotion strategies for tourist loyalty: Surveying the restart of Chinese national holiday travel after COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102704

- Canavan, B. (2013). The extent and role of domestic tourism in a small island: The case of the Isle of Man. Journal of Travel Research, 52(3), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287512467700

- Chi, X., Cai, G., & Han, H. (2021). Festival travellers’ pro-social and protective behaviours against COVID-19 in the time of pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(22), 3256–3270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1908968

- Chi, X., & Han, H. (2021). Performance of tourism products in a slow city and formation of affection and loyalty: Yaxi Cittáslow visitors’ perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(10), 1586–1612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1860996

- Chi, X., Han, H., & Kim, S. (2021). Protecting yourself and others: Festival tourists’ pro-social intentions for wearing a mask, maintaining social distancing, and practicing sanitary/hygiene actions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(8), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1966017

- Coghlan, A. (2015). Prosocial behaviour in volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 55, 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.08.002

- Corbin, J. M. & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

- Creswell, J. & W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3RD ed.). Sage.

- Dancausa, G., Hernández, R. D., & Pérez, L. M. (2023). Motivations and constraints for the ghost tourism: A case study in Spain. Leisure Sciences, 45(2), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1805655

- Dann, G. M. S. (1977). Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(77)90037-8

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Sage.

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial Development. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 646–718). John Wiley.

- Eren, D., Burke, R. J., Astakhova, M., Koyuncu, M., & Kaygısız, N. C. (2014). Service rewards and prosocial service behaviours among employees in four and five star hotels in Cappadocia. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Research, 25(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2013.875047

- Farzanegan, M. R., Gholipour, H. F., Feizi, M., Nunkoo, R., & Andargoli, A. E. (2021). International tourism and outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19): A cross-country analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 687–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520931593

- Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourist motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 555–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)90120-1

- Gaetjens, A., Corsi, A. M., & Plewa, C. (2023). Customer engagement in domestic wine tourism: The role of motivations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 27, 100761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2022.100761

- Han, H., Chi, X., Kim, C.-S., & Ryu, H. B. (2020). Activators of airline customers’ sense of moral obligation to engage in pro-social behaviors: Impact of CSR in the Korean marketplace. Sustainability, 12(10), 4334. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104334

- Han, H., Hwang, J., & Lee, S. (2017). Cognitive, affective, normative, and moral triggers of sustainable intentions among convention-goers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.003

- Han, H., Meng, B., Chua, B.-L., & Ryu, H. B. (2020). Hedonic and utilitarian performances as determinants of mental health and pro-social behaviors among volunteer tourists. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186594

- Hartmann, P., & Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. (2012). Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. Journal of Business Research, 65(9), 1254–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.11.001

- Hartmann, P., Eisend, M., Apaolaza, V., & D’Souza, C. (2017). Warm glow vs. altruistic values: How important is intrinsic emotional reward in proenvironmental behavior? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 52, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.05.006

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Imas, A. (2014). Working for the “warm glow”: On the benefits and limits of prosocial incentives. Journal of Public Economics, 114, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2013.11.006

- Isen, A. M. (1970). Success, failure, attention, and reaction to others: The warm glow of success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 15(4), 294. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029610

- Isen, A. M., & Levin, P. F. (1972). Effect of feeling good on helping: Cookies and kindness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(3), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032317

- Ivanova, M., Ivanov, I. K., & Ivanov, S. (2021). Travel behaviour after the pandemic: The case of Bulgaria. Anatolia: An International Journal of Tourism & Hospitality Research, 32(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1818267

- Jafari, J. (1986). On domestic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(3), 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(86)90033-2

- Jeon, C.-Y., Song, W.-G., & Yang, H.-W. (2022). Process of forming tourists’ pro-social tourism behavior intentions that affect willingness to pay for safety tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative analysis of South Korea and China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 27(4), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2022.2075774

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Kahneman, D., & Knetsch, J. L. (1992). Valuing public goods: The purchase of moral satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 22(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/0095-0696(92)90019-S

- Kim, M. J., Park, J. Y., Reisinger, Y., & Lee, C.-K. (2018). Predicting responsible tourist behavior: Exploring pro-social behavior and perceptions of responsible tourism. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, 32(4), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.21298/IJTHR.2018.4.32.4.5

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Lin, Y., Fu, X., Gu, X., & Song, H. (2018). Institutional ownership and return volatility in the casino industry. International Journal of Tourism Research, 20(2), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2173

- MacauGovernmentTourismOffice(MGTO). (2020). “Macao Ready Go! Local Tours” attracted close to 140,000 participants -over 85% interviewees satisfied with tour arrangements. Retrieved September 24, 2021, from https://industry.macaotourism.gov.mo/en/pressroom/index.php?page_id=7&id=3258.

- Manan, M. M. A., & Várhelyi, A. (2015). Exploration of motorcyclists’ behavior at access points of a Malaysian primary road–A qualitative observation study. Safety Science, 74, 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.01.005

- Maner, J. K., & Gailliot, M. T. (2007). Altruism and egoism: Prosocial motivations for helping depend on relationship context. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(2), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.364

- Mares, M.-L., & Woodard, E. (2012). Effects of prosocial media content on children’s social interactions. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (2nd edn ed., pp. 197–214). Sage.

- Mohanty, P., Dhoundiyal, H., & Choudhury, R. (2020). Events tourism in the eye of the COVID-19 storm: Impacts and implications. In Event tourism in Asian countries: Challenges and prospects (1st ed). Apple Academic Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3682648

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Residents’ satisfaction with community attributes and support for tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348010384600

- Pearce, P. L., & Lee, U.-I. (2005). Developing the travel Career approach to tourist motivation. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504272020

- Phellas, C. N., Bloch, A. & Seale, C. (2011). Structured methods: Interviews, questionnaires, and observation. Researching Society and Culture, 3(1), 23–32.

- Pyszczynski, T., Lockett, M., Greenberg, J., & Solomon, S. (2021). Terror management theory and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167820959488

- Qiu, R. T. R., Park, J., Li, S., & Song, H. (2020). Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102994

- Ramkissoon, H. (2020a). COVID-19 place confinement, pro-social, pro-environmental behaviors, and residents’ wellbeing: A new conceptual framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02248

- Ramkissoon, H. (2020b). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

- Riadil, I. G. (2020). Tourism industry crisis and its impacts: Investigating the Indonesian tourism employees perspectives’ in the pandemic of COVID-19. Jurnal Kepariwisataan: Destinasi, Hospitalitas dan Perjalanan, 4(2), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.34013/jk.v4i2.54

- Roe, B., Teisl, M. F., Levy, A., & Russell, M. (2001). US consumers’ willingness to pay for green electricity. Energy Policy, 29(11), 917–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-4215(01)00006-4

- Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Restructuring the geography of domestic tourism in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography: Socio-Economic Series, 29(29), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1515/bog-2015-0029

- Romani, S., & Grappi, S. (2014). How companies’ good deeds encourage consumers to adopt pro-social behavior. European Journal of Marketing, 48(5/6), 943–963. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2012-0364

- Roseman, I. J. (1991). Appraisal determinants of discrete emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 5(3), 161–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939108411034

- Rowen, I. (2020). The transformational festival as a subversive toolbox for a transformed tourism: Lessons from Burning Man for a COVID-19 world. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759132

- Sahoo, S., Rani, S., Parveen, S., Singh, A. P., Mehra, A., Chakrabarti, S. & Tandup, C. (2020). Self-harm and COVID-19 pandemic: An emerging concern–A report of 2 cases from India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102104

- Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative explanations of helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(4), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(73)90071-1

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Sojasi Qeidari, H., Seyfi, S., Hall, C. M., Vo-Thanh, T., & Zaman, M. (2023). ‘You wouldn’t want to go there’: What drives the stigmatization of a destination? Tourism Recreation Research, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2023.2175561

- Stern, P. C., Kalof, L., Dietz, T., & Guagnano, G. A. (1995). Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25(18), 1611–1636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02636.x

- Tse, S., & Tung, V. W. S. (2020). Residents’ discrimination against tourists. Annals of Tourism Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103060 88 103060

- Tse, W. T. S., & Tung, V. W. S. (2023). Assessing explicit and implicit stereotypes in tourism: Self-reports and implicit association test. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 460–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1860995

- Tung, V. W. S. (2019). Helping a lost tourist: The effects of metastereotypes on resident prosocial behaviors. Journal of Travel Research, 58(5), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518778150

- UNWTO. (2021). 2020: Worst year in tourism history with 1 billion fewer International arrivals. Retrieved from: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals.

- Uriely, N., Yonay, Y., & Simchai, D. (2002). Backpacking experiences: A type and form analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(2), 520–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(01)00075-5

- Usher, K., Durkin, J., & Bhullar, N. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic and mental health impacts. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(3), 315. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12726

- Wan, Y. K. P., & Li, X. (2013). Sustainability of tourism development in Macao, China. International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.873

- Zavitz, K. J., & Butz, D. (2011). Not that alternative: Short-term volunteer tourism at an organic farming project in Costa Rica. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 10(3), 412–441.

- Zhang, C. X., Pearce, P., & Chen, G. (2019). Not losing our collective face: Social identity and Chinese tourists’ reflections on uncivilised behaviour. Tourism Management, 73, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.020

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y., Lee, T. J., Ye, M., & Nunkoo, R. (2021). Sociocultural sustainability and the formation of social capital from community-based tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520933673

- Zhao, X., Wang, X., & Ji, L. (2020). Evaluating the effect of anticipated emotion on forming environmentally responsible behavior in heritage tourism: Developing an extended model of norm activation theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(11), 1185–1198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1837892

- Zhu, H., & Deng, F. (2020). How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103514